Key Points

Question

Do patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) receive microsatellite instability and/or immunohistochemistry (MSI/IHC) tumor screening and germline genetic testing (GGT) when they have insurance that covers these tests?

Findings

In a cohort study of 9066 patients with CRC in 2017 to 2020, 2288 (25.2%) did not receive MSI/IHC despite being eligible for coverage. In a cohort of 55 595 patients with CRC diagnosed in 2020 and covered by insurance, 1675 (3.0%) received GGT, and 1 in 6 patients had variants that were clinically actionable.

Meaning

These results indicate that medical policies that provide universal testing for MSI/IHC tumor screening and GGT were underused for patients with CRC, potentially impeding their access to precision therapy, clinical trials, and evidence-based clinical management.

This cohort study of claims data examines whether uptake of microsatellite instability and/or immunohistochemistry tumor screening germline genetic testing for patients with colorectal cancer has improved since implementation of universal coverage by insurance policies.

Abstract

Importance

In 2020, some health insurance plans updated their medical policy to cover germline genetic testing for all patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC). Guidelines for universal tumor screening via microsatellite instability and/or immunohistochemistry (MSI/IHC) for mismatch repair protein expression for patients with CRC have been in place since 2009.

Objectives

To examine whether uptake of MSI/IHC screening and germline genetic testing in patients with CRC has improved under these policies and to identify actionable findings and management implications for patients referred for germline genetic testing.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The multicenter, retrospective cohort study comprised 2 analyses of patients 18 years or older who were diagnosed with CRC between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2020. The first analysis used an insurance claims data set to examine use of MSI/IHC screening and germline genetic testing for patients diagnosed with CRC between 2017 and 2020 and treated with systemic therapy. The second comprised patients with CRC who had germline genetic testing performed in 2020 that was billed under a universal testing policy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patient demographic characteristics, clinical information, and use of MSI/IHC screening and germline genetic testing were analyzed.

Results

For 9066 patients with newly diagnosed CRC (mean [SD] age, 64.2 [12.7] years; 4964 [54.8%] male), administrative claims data indicated that MSI/IHC was performed in 6645 eligible patients (73.3%) during the study period, with 2288 (25.2%) not receiving MSI/IHC despite being eligible for coverage. Analysis of a second cohort of 55 595 patients with CRC diagnosed in 2020 and covered by insurance found that only 1675 (3.0%) received germline genetic testing. In a subset of patients for whom germline genetic testing results were available, 1 in 6 patients had pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, with most of these patients having variants with established clinical actionability.

Conclusions and Relevance

This nationwide cohort study found suboptimal rates of MSI/IHC screening and germline genetic testing uptake, resulting in clinically actionable genetic data being unavailable to patients diagnosed with CRC, despite universal eligibility. Effective strategies are required to address barriers to implementation of evidence-based universal testing policies that support precision treatment and optimal care management for patients with CRC.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most diagnosed cancer in the US and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths.1 Approximately 5% to 15% of CRCs are caused by inherited cancer susceptibility genes,2 making germline genetic testing (GGT) essential to clinical management.

Lynch syndrome, the most common form of hereditary CRC, is caused by pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variants (PGVs) in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes and EPCAM (OMIM 185535).3 Universal tumor screening via microsatellite instability (MSI) and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC) for MMR expression is recommended for all patients with newly diagnosed CRC.4 Data from MSI/IHC can significantly affect treatment because the immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) pembrolizumab, approved in 2017 as a second-line therapy for CRC, is now approved as a first-line therapy for patients with high MSI or MMR deficiency.5

Before 2022, guidelines for GGT in patients with CRC were based on diagnosis age 50 years, MSI/IHC results, or fulfillment of complex personal and/or family history criteria.6 In 2020, some health insurance plans broadened their commercial medical policy to universally cover GGT for enrollees diagnosed with CRC.7 In this study, we conducted 2 retrospective analyses: one of claims data for patients with newly diagnosed CRC between 2017 to 2020 and the other of GGT findings for patients diagnosed with CRC in 2020 and covered for testing under a newly implemented universal policy. Our objective was to examine whether uptake of MSI/IHC tumor screening GGT for patients has improved since implementation of universal coverage by insurance policies.

Methods

An internal institutional review board (IRB) deemed the retrospective analysis of Optum Labs administrative deidentified claims data exempt from review and patient consent requirement because the study was a secondary analysis of previously collected data. Use of patient data obtained from GGT performed by Invitae was approved by an independent IRB (WCG IRB). Patients provided written informed consent to have their deidentified data used in the study. Data were recorded in an electronic study database that complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cohort studies.

A retrospective analysis of claims data for a cohort of 36 270 patients with newly diagnosed CRC was conducted using longitudinal data from enrollment records, laboratory results, and medical claims for commercial insurance and Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollees. Study criteria included adults (aged ≥18 years) with newly diagnosed CRC (≥2 claims for International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] codes C18.x, C19.x, C20.x, and C21.8) from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2020; the date of the earliest CRC claim was considered the index diagnosis date. Enrollees were required to have continuous enrollment in a commercial or MA plan for at least 12 months before diagnosis and 6 months or more after diagnosis, no claims for CRC in the 12-month prediagnosis period, and 1 claim or more for initial antineoplastic systemic therapy (ST) at 6 months or earlier after diagnosis. A total of 9066 patients who met the above criteria were stratified into 4 cohorts as follows: cohort 1, GGT but no MSI/IHC before ST; cohort 2, GGT and MSI/IHC before ST; cohort 3, no GGT or MSI/IHC before ST; and cohort 4, MSI/IHC but no GGT before ST. Use of follow-up health care, procedures, and ICI therapy were tracked. Self-reported race and ethnicity were assessed in this study to elucidate, if present, any evidence of health care disparities in this cohort. The self-reported ethnicity information for the 743 patients came from the Invitae data set. This information was provided by clinicians on the test requisition form. Those with unknown ethnicity had “unknown” indicated on the test requisition form. Statistically significant differences (2-sided P < .05) in patient characteristics and health care resource utilization were determined using analysis of variance or χ2 tests.

Because claims data do not specify GGT findings, a separate analysis was conducted using an independent cohort of 55 595 enrollees who were diagnosed with CRC in 2020 and covered by a universal medical insurance policy. By querying the Invitae database, 1675 patients with CRC who were covered by the policy were found to have undergone GGT (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Testing results were available for 787 of these patients. Pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variants were evaluated according to published management recommendations or eligibility for potential precision therapy treatment.6 Patients were also evaluated for clinical trial eligibility based on PGV findings in homologous recombination deficiency genes relevant to poly–(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase inhibitor–based therapy trials.8

Results

For the claims analysis, 9066 patients with newly diagnosed CRC (mean [SD] age, 64.2 [12.7] years; 4964 men [54.8%] and 4099 women [45.2%]) met all the study criteria and were stratified into the 4 cohorts according to uptake of GGT and/or MSI/IHC before ST (Table 1). Self-reported data on ancestry and ethnicity were available for 743 patients (94.4%), of whom 34 (4.6%) were Asian or Pacific Islander, 69 (9.3%) were Black, 62 (8.3%) were Hispanic, and 47 (6.3%) were of other ancestry or ethnicity (Table 2). Administrative claims data indicated that overall, MSI/IHC was performed in 6645 eligible patients (73.3%) during the study period, with 2288 (25.2%) not receiving MSI/IHC despite being eligible for coverage.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics, Health Care Resource Utilization, and Follow-up Procedures for Enrollees Diagnosed With Colorectal Cancer, 2017-2020a.

| Variable | All (N = 9066) | With GGT before ST | No GGT before ST | P values comparing cohorts 1-4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No MSI or IHC before ST (n = 130) | MSI or IHC before ST (n = 903) | No MSI or IHC before ST (n = 2288) | MSI or IHC before ST (n = 5745) | |||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 64.2 (12.7) | 55.3 (14.8) | 56.2 (14.2) | 66.5 (12.0) | 64.8 (12.0) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 4099 (45.2) | 63 (48.4) | 441 (48.8) | 1050 (45.9) | 2545 (44.3) | <.001 |

| Male | 4964 (54.8) | 67 (51.5) | 461 (51.1) | 1238 (54.1) | 3198 (55.7) | |

| Insurance type | ||||||

| Commercial | 5103 (56.3) | 96 (73.9) | 654 (72.4) | 1144 (50.0) | 3209 (55.9) | <.001 |

| Medicare Advantage | 3963 (43.7) | 34 (26.2) | 249 (27.6) | 1144 (50.0) | 2536 (44.1) | |

| Advanced cancer at diagnosisb | 4879 (53.8) | 67 (51.5) | 596 (66.0) | 1015 (44.4) | 3201 (55.7) | <.001 |

| Index year | ||||||

| 2017 | 2156 (23.8) | 40 (30.8) | 199 (22.0) | 662 (28.9) | 1255 (21.8) | <.001 |

| 2018 | 2371 (26.2) | 29 (22.3) | 203 (22.5) | 617 (27.0) | 1522 (26.5) | |

| 2019 | 2504 (27.6) | 36 (27.7) | 251 (27.8) | 565 (24.7) | 1652 (28.8) | |

| 2020 | 2035 (22.5) | 25 (19.2) | 250 (27.7) | 444 (19.4) | 1316 (22.9) | |

| Index diagnosis codes | ||||||

| C18 or C19 | 6094 (67.2) | 83 (63.9) | 684 (75.8) | 1304 (57.0) | 4023 (70.0) | <.001 |

| C20 or C21.8 | 2222 (24.5) | 32 (24.6) | 146 (16.2) | 806 (35.2) | 1238 (21.6) | |

| Multiple | 750 (8.3) | 15 (11.5) | 73 (8.1) | 178 (7.8) | 484 (8.4) | |

| Follow-up proceduresc | ||||||

| CRC surgery | 6830 (75.3) | 97 (74.6) | 708 (78.4) | 1513 (66.1) | 4512 (78.5) | <.001 |

| Radiation | 3165 (34.9) | 44 (33.9) | 268 (29.7) | 1045 (46.7) | 1808 (31.5) | <.001 |

| ST | 9066 (100.0) | 130 (100.0) | 903 (100.0) | 2288 (100.0) | 5745 (100.0) | NA |

| Follow-up ICI therapyc | 222 (2.5) | <11 (<8.5)d | 58 (6.4) | >30 (<1.3)d | 130 (2.3) | NA |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; GGT, germline genetic testing; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MSI, microsatellite instability; NA, not applicable; ST, systemic therapy.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Defined as patients with at least 1 medical claim with International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code C77.xx to C80.0.x within 60 days of the index date.

Follow-up period was a minimum of 6 months and a maximum of 12 months continuous enrollment after the index date.

Data are masked to comply with data use policy.

Table 2. Self-reported Ancestry or Ethnicity of Patients Covered by Insurance Undergoing Germline Genetic Testing in 2020.

| Self-reported ancestry or ethnicity | Patients, No. (% of total) | No. (% of each category) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient with PGVs | Patients without variants | VUS | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 34 (4.6) | 6 (17.6) | 14 (41.2) | 14 (41.2) |

| Black | 69 (9.3) | 15 (21.7) | 27 (39.1) | 27 (39.1) |

| Hispanic | 62 (8.3) | 8 (12.9) | 28 (45.2) | 26 (41.9) |

| White | 531 (71.5) | 83 (15.6) | 254 (47.8) | 194 (36.5) |

| Othera | 47 (6.3) | 4 (8.5) | 25 (53.2) | 18 (38.3) |

| Total | 743 | 116 (15.6) | 348 (46.8) | 279 (37.6) |

Abbreviations: PGV, pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Patients identified themselves as other ancestry or ethnicity.

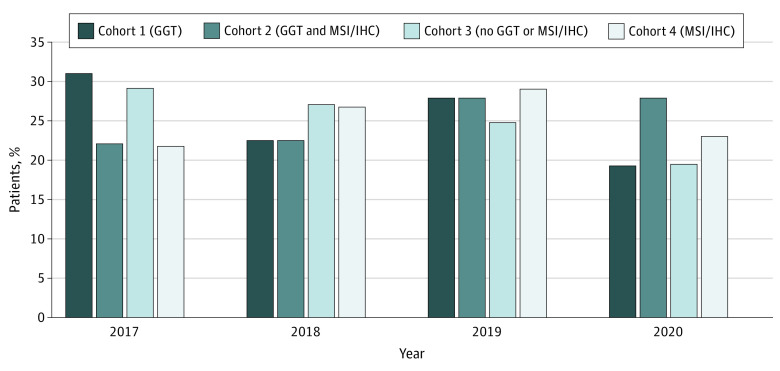

Patients who received GGT were younger than those who did not (mean [SD] age, 55.3 [14.8] years for cohort 1 and 56.2 [14.2] years for cohort 2 vs 66.5 [12.0] years for cohort 3 and 64.8 [12.0] years for cohort 4; P < .001). Use of ICI therapy was higher among patients who had both GGT and MSI/IHC (58 [6.4%] in cohort 2) compared with those who had MSI/IHC only (130 [2.3%] in cohort 4) (Table 1). During the study period, 1033 patients (11.4%) received GGT, with a small increase in the proportion of patients who received GGT observed for 2020 (Figure 1). This finding is attributable to a significantly higher proportion of commercial insurance enrollees younger than 65 years who underwent GGT in 2020 compared with earlier years, where uptake for GGT was less than 15% per year (P = .03) (eFigure and eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Germline Genetic Testing (GGT) and/or Microsatellite Instability and/or Immunohistochemistry (MSI/IHC) Tumor Screening in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Before Initial Systemic Therapy.

Proportion of patients with colorectal cancer (n = 9066) who, before initial systemic therapy, received GGT (cohort 1), GGT and MSI/IHC tumor screening (cohort 2), no GGT or MSI/IHC (cohort 3), or MSI/IHC only (cohort 4). P < .001 for comparison of the 4 cohorts.

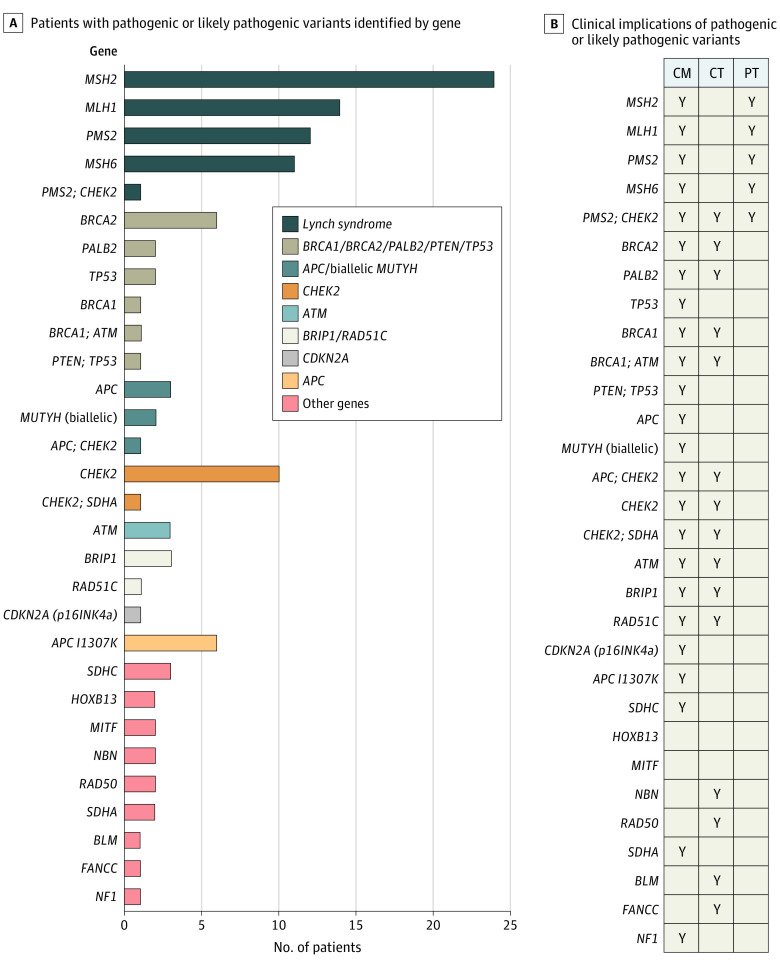

In the GGT findings analysis, of 55 595 patients diagnosed with CRC in 2020 and covered for GGT under a universal policy, 1675 (3.0%) underwent GGT, with testing results available for 787 patients. Of these, 141 patients (17.8%) had 151 PGVs in 29 genes (Figure 2A), which included 19 patients who carried a single PGV in a gene associated with autosomal recessive inheritance. If these patients are excluded, the overall PGV rate was 15.4% (n = 122), of whom 62 (50.8%) had Lynch syndrome and 118 (96.7%) had PGVs that were potentially eligible for precision therapy, clinical trials, and/or established management recommendations (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Patients With Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic Variants.

A. Patients with colorectal cancer covered for germline genetic testing underwent testing with a multigene panel at Invitae in 2020 (n = 787). A total of 122 patients had pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in 26 genes. B. Clinical actionability by gene. Clinical treatment trials were current trials in which a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in the specified gene was among the inclusion criteria for enrollment. Precision therapy and management guidelines were determined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network colorectal cancer guidelines.6 Clinical trial eligibility was based on pathogenic germline variant findings in homologous recombination deficiency genes relevant to poly–(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase inhibitor–based therapy trials.8 A total of 24 of 26 genes (92.3%) identified are clinically actionable. Of 122 patients, 62 (50.8%) qualified for precision therapy (PT), 36 (29.5%) were potentially eligible for a clinical treatment trial (CT), and 112 (91.8%) were eligible for changes to management (CM). Y indicates that a pathogenic variant in the listed gene(s) has clinical actionability represented by CM, CT, or PT.

Discussion

Despite long-standing guidelines for universal MSI/IHC screening, we found uptake to be less than 75% during the study period. We also examined GGT uptake to better understand its use among patients who were eligible for ST treatment, because there are treatment options for patients identified with high MSI or MMR deficiency.9,10 The uptake for GGT was less than 15% for each year; however, a significant increase was found in uptake for commercial insurance enrollees younger than 65 years in 2020 compared with earlier years. This finding is notable because health care resource utilization decreased in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.11 Although results of MMR testing are unknown, it is estimated that approximately 15% of sporadic CRCs are attributable to MMR deficiency.12 The suboptimal uptake of GGT indicated in this study points to a lack of testing that should have been guided by tumor testing.

To further characterize the value of GGT, we analyzed an independent cohort of patients with CRC who received GGT testing in 2020 at a commercial testing laboratory and were covered by a universal medical insurance policy. We found that for 55 595 patients with CRC diagnosed in 2020 and covered by the policy, only 3.0% received GGT. Our evaluation determined that 1 in 5 of these patients had PGVs and 1 in 6 had PGVs with established clinical actionability. These data suggest that for the 55 595 patients diagnosed with CRC and covered by a universal medical policy, systematic implementation of universal GGT could have identified approximately 6700 additional patients with PGVs, conferring potential eligibility for precision therapy or clinical trials, and approximately 2600 additional patients with PGVs in genes with published management recommendations. In similar studies,2,13 clinically actionable findings were identified in 7.8% to 12.7% of patients with CRC who were tested. Among patients with CRC who carry a PGV, 95% would have benefited from enhanced surveillance and tailored treatment.14

Estimates of PGV rates among unselected patients with CRC range from 9.9% to 15.5%.2,15,16 Of the 122 patients with PGVs examined in our study, 62 (50.8%) had Lynch syndrome, meaning half of the individuals with PGVs did not have Lynch syndrome but did have PGVs with published recommendations for improved treatment and proactive surveillance,6,17 access to approved or emerging precision therapies,18 and referral to genetic counseling and cascade testing for at-risk relatives.19 For these patients without Lynch syndrome, the identification of a PGV in a gene not traditionally associated with CRC cannot be inferred to be the cause of a patient’s cancer; this assertion would require somatic tumor sequencing and is beyond the scope of this analysis. Nevertheless, multiple precision therapy clinical trials8,20 offer enrollment to patients based on the presence of PGVs or somatic tumor test variants in specific cancer genes. Consistent with the access to clinical treatment trials and management afforded to patients by GGT, the recent report from the President’s Cancer Panel supports GGT for all patients diagnosed with cancer and recommends cascade testing if variants of concern are identified.21

Despite these benefits, the current study suggests that barriers to implementation of universal testing remain. Increased financial burden is often raised as an argument against universal testing, yet this argument is contradicted by cost analyses of Lynch syndrome screening in the US and Europe.22,23 The value of universal GGT testing has been questioned by some based on the number of low-penetrance genes or recessive alleles included in multigene panels.24 However, the classification of variants as pathogenic or likely pathogenic in the multigene panel used in the current study and others2,16 is consistent with the rigorous variant interpretation criteria proposed by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.25 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network provides recommendations for patients with findings in low-penetrance or recessive alleles, including, at a minimum, family history evaluation and subsequent endoscopic surveillance.18 Most importantly, practice guidelines were recently updated to include universal germline testing for all patients with CRC.26

In a recent study27 of claims data from a large national commercial insurer from 2008 to 2018, only one-third of patients with ovarian cancer covered for GGT by insurance received it, despite universal testing being categorically recommended.17 Low uptake was attributed primarily to lack of physician recommendations, particularly among nononcologists, indicating a lack of guideline awareness. Lack of clinician recommendations has been cited by other studies, pointing to complex guidelines and lack of awareness of policy updates that impede referrals.28,29 In a study of an electronic health record–derived deidentified database of patients with metastatic prostate cancer from 2013 to 2019, only one-tenth of patients received GGT despite it being universally recommended by consensus guidelines.30 Uptake was higher in academic vs community centers, possibly because of better access to in-house DNA sequencing facilities in academic centers.

Although self-reported race and ethnicity data were not available in our claims data set, disparities in access and uptake of genetic testing and counseling have been identified for Black and African American patients.31,32 Patient-level factors, such as discrimination and mistrust in the health care system, are known to play a role in racial and ethnic disparities.33,34,35 Notably, in a study of adults aged 18 to 49 years diagnosed with CRC between 2009 and 2017, a lower proportion of Black patients were referred for genetic counseling, yet no difference was found by race or ethnicity in receipt of GGT for patients who received genetic counseling.36 Therefore, addressing deficiencies in awareness and referrals at the practitioner level is crucial to improving information and access to genetic testing for all populations.37

Limitations

Claims data used in this analysis represent only a portion of commercial and MA enrollees; thus, our results are not necessarily generalizable to all enrollees or other populations, including the uninsured and those outside the US. In addition, claims data do not guarantee that a patient was diagnosed or received testing or treatment. The data set also lacks demographic information, including race and ethnicity, and stratification based on age or precise geographic location was untenable because of data masking requirements. Although claims data, particularly from a closed system, are efficient and effective for capturing health care resource utilization,38 procedures that do not generate claims (eg, care received within the context of a clinical trial that is covered by the trial sponsor) would not be included in this analysis. Because the Current Procedural Terminology code for IHC is not specific to MMR proteins, IHC claims may include other protein analyses and overrepresent the number of patients who received Lynch syndrome or ICI eligibility screening. Of note, our claims analysis was limited to patients with advanced disease who received ST. Further work is necessary to provide comprehensive analyses of testing and follow-up management for patients beyond those with advanced disease. Finally, the time window of our study overlapped with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is likely to have had an inordinate influence on referrals and uptake. Evaluating the full impact of the pandemic is an important consideration for future research.

Conclusions

This cohort study provides evidence of low MSI/IHC use despite medical policies recommending universal GGT and suggests that an unexpectedly high proportion of CRC patients do not undergo MSI/IHC testing, leading to missed opportunities for genetics-informed precision treatment. By drawing attention to exemplars of innovative medical policy, these data provide insight for health care practitioners and health insurance companies about the benefits of implementing universal genetic testing policies. Future efforts should focus on improving practitioner awareness and removing barriers to effective implementation of universal genetic testing to improve the clinical care of patients with cancer.

eTable 1. Genes Included in Invitae’s Multi-cancer Gene Panel

eTable 2. Enrollees Diagnosed with Colorectal Cancer Who Received Germline Genetic Testing 2017–2020 by Policy Type and Age

eFigure. Uptake of Germline Genetic Testing for 2017-2020 by Policy Type and Age

eReferences

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uson PLS Jr, Riegert-Johnson D, Boardman L, et al. Germline cancer susceptibility gene testing in unselected patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma: a multicenter prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):e508-e528. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonadona V, Bonaïti B, Olschwang S, et al. ; French Cancer Genetics Network . Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 genes in Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2304-2310. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group . Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: genetic testing strategies in newly diagnosed individuals with colorectal cancer aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome in relatives. Genet Med. 2009;11(1):35-41. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818fa2ff [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguiar-Ibáñez R, Hardern C, van Hees F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab for the first-line treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic MSI-H/dMMR colorectal cancer in the United States. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):469-480. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2022.2043634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss JM, Gupta S, Burke CA, et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, version 1.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(10):1122-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Healthcare . Genetic testing for hereditary cancer (policy number: 2021T0009FF). Published January 1, 2020. Accessed September 15, 2022. https://www.uhcprovider.com/content/dam/provider/docs/public/policies/comm-medical-drug/genetic-testing-hereditary-cancer.pdf

- 8.Niraparib plus carboplatin in patients with homologous recombination deficient advanced solid tumor malignancies. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03209401. Updated September 1, 2021. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03209401

- 9.Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, et al. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(8):773-779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.9901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz LA Jr, Shiu KK, Kim TW, et al. ; KEYNOTE-177 Investigators . Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer (KEYNOTE-177): final analysis of a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(5):659-670. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00197-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e045343. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poulogiannis G, Frayling IM, Arends MJ. DNA mismatch repair deficiency in sporadic colorectal cancer and Lynch syndrome. Histopathology. 2010;56(2):167-179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller C, Nielsen SM, Hatchell KE, et al. Underdiagnosis of hereditary colorectal cancers among Medicare patients: genetic testing criteria for lynch syndrome miss the mark. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:1103-1111. doi: 10.1200/PO.21.00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang W, Li L, Ke CF, et al. Universal germline testing among patients with colorectal cancer: clinical actionability and optimised panel. J Med Genet. 2022;59(4):370-376. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-107230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yurgelun MB, Kulke MH, Fuchs CS, et al. Cancer susceptibility gene mutations in individuals with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(10):1086-1095. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samadder NJ, Riegert-Johnson D, Boardman L, et al. Comparison of universal genetic testing vs guideline-directed targeted testing for patients with hereditary cancer syndrome. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):230-237. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, et al. ; CGC; CGC; LCGC; CGC; CGC . Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(1):77-102. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esplin ED, Samadder NJ. Universal genetic testing to identify pathogenic germline variants in patients with cancer—reply. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(7):1071-1072. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beitsch P, Hughes K, Whitworth P. Reply to M.S. Copur et al, A. Taylor et al, and P.S. Rajagopal et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(24):2178-2180. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ClinicalTrials.gov . Phase II trial of talazoparib in BRCA1/2 wild-type HER2-negative breast cancer and other solid tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02401347. Updated September 2, 2021. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02401347

- 21.President’s Cancer Panel . Closing gaps in cancer screening: connecting people, communities, and systems to improve equity and access. Published February 2022. Accessed April 2022. https://prescancerpanel.cancer.gov/report/cancerscreening/pdf/PresCancerPanel_CancerScreening_Feb2022.pdf

- 22.Salikhanov I, Heinimann K, Chappuis P, et al. Swiss cost-effectiveness analysis of universal screening for Lynch syndrome of patients with colorectal cancer followed by cascade genetic testing of relatives. J Med Genet. 2022;59(9):924-930. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2021-108062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guzauskas GF, Jiang S, Garbett S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of population-wide genomic screening for Lynch syndrome in the United States. Genet Med. 2022;24(5):1017-1026. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hampel H, Yurgelun MB. Point/Counterpoint: is it time for universal germline genetic testing for all GI cancers? J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(24):2681-2692. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nykamp K, Anderson M, Powers M, et al. ; Invitae Clinical Genomics Group . Sherloc: a comprehensive refinement of the ACMG-AMP variant classification criteria. Genet Med. 2017;19(10):1105-1117. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson W, Ripley-Burgess D, Hampel H, May FP, Davis A, Goldberg RM. All colorectal cancer patients require germline testing at diagnosis and somatic testing at advanced disease diagnosis. Cancer Letter. Published July 15, 2022. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://cancerletter.com/trials-and-tribulations/20220715_1/

- 27.Cham S, Landrum MB, Keating NL, Armstrong J, Wright AA. Use of germline BRCA testing in patients with ovarian cancer and commercial insurance. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2142703. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swink A, Nair A, Hoof P, et al. Barriers to the utilization of genetic testing and genetic counseling in patients with suspected hereditary breast and ovarian cancers. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32(3):340-344. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2019.1612702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armstrong J, Toscano M, Kotchko N, et al. Utilization and outcomes of BRCA genetic testing and counseling in a national commercially insured population: the ABOUT study. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(9):1251-1260. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shore N, Ionescu-Ittu R, Yang L, et al. Real-world genetic testing patterns in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2021;17(22):2907-2921. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cragun D, Weidner A, Lewis C, et al. Racial disparities in BRCA testing and cancer risk management across a population-based sample of young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123(13):2497-2505. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson JM, Pepin A, Thomas R, et al. Racial disparities in breast cancer hereditary risk assessment referrals. J Genet Couns. 2020;29(4):587-593. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, et al. ; American Heart Association . Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454-e468. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Washington A, Randall J. “We’re not taken seriously”: describing the experiences of perceived discrimination in medical settings for Black women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. Published online March 3, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s40615-022-01276-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoadley A, Bass SB, Chertock Y, et al. The role of medical mistrust in concerns about tumor genomic profiling among Black and African American cancer patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(5):2598. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dharwadkar P, Greenan G, Stoffel EM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in germline genetic testing of patients with young-onset colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(2):353-361.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajagopal PS, Catenacci DVT, Olopade OI. The time for mainstreaming germline testing for patients with breast cancer Is now. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(24):2177-2178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birnbaum HG, Cremieux PY, Greenberg PE, LeLorier J, Ostrander JA, Venditti L. Using healthcare claims data for outcomes research and pharmacoeconomic analyses. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;16(1):1-8. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199916010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Genes Included in Invitae’s Multi-cancer Gene Panel

eTable 2. Enrollees Diagnosed with Colorectal Cancer Who Received Germline Genetic Testing 2017–2020 by Policy Type and Age

eFigure. Uptake of Germline Genetic Testing for 2017-2020 by Policy Type and Age

eReferences