Abstract

This study examines the interplay between race/ethnicity and educational attainment in shaping completed fertility for U.S. women born during 1960–80. Using data from the National Survey of Family Growth from 2006 to 2017, we apply multilevel multiprocess hazard models to account for unobserved heterogeneity and estimate 1) cohort total fertility rates, 2) parity progression ratios, and 3) parity-specific fertility timing, for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic women by educational attainments. We find that compared to their White counterparts, Black and Hispanic women with less than a high school education have higher fertility. However, among college educated women, Black women have the lowest fertility levels, whereas Hispanic women have the highest. The difference in fertility between Black and White college educated women is mainly driven by the smaller proportion of Black mothers having second births. We find little evidence that the observed racial/ethnic disparities in fertility levels across educational levels are driven by differences in fertility timing.

Keywords: Fertility Racial/Ethnic Disparities, Educational Disparities, Parity Progression Ratio, Fertility Timing

Introduction

Despite a significant growth in the number of female college graduates from marginalized groups in the recent decades in the United States (Espinosa et al 2019; Maralani 2013), racial/ethnic gaps in educational attainment continue to grow (Reeves and Guyot 2017; Rothwell 2015). At the same time, gaps in the number of completed births across educational attainments have persisted without any signs of convergence (Yang and Morgan 2003). If childbearing behaviors of non-Hispanic White (hereafter “White”), non-Hispanic Black (hereafter “Black”), and Hispanic women with the same educational attainment are similar, these trends will predict a widening gap in completed fertility across racial/ethnic groups. However, fertility rates since the 1990s, in fact, have shown decades of convergence among Black, Hispanic, and White women (Sweeney and Raley 2014). One way to understand these inconsistent trends is to better understand how the interaction between race/ethnicity and education shapes fertility. This question remains underexamined in the recent literature. Understanding this question is important because fertility patterns by education and race/ethnicity have implications for the composition and wealth distribution of future generations (Maralani 2013; McLanahan 2004).

With only a handful of exceptions (e.g., Musick et al 2009; Sweeney and Raley 2014), most empirical studies on this topic are from at least twenty years ago, with some evidence that racial differences in fertility levels are only significantly present among women without a college degree (Johnson 1979; Yang and Morgan 2003). However, tabulations using data from 2006–2010 suggest that racial/ethnic differences in childbearing may be greatest among the most advantaged groups of women measured by their mothers’ educational attainment (Sweeney and Raley 2014). Musick et al (2009) did a more comprehensive multivariate hazard analysis using data for cohorts born from 1957 through 1964. They have found that Black women without college degrees have higher completed fertility compared to their White counterparts, but Black women with college degrees have lower completed fertility compared to their White counterparts.

This finding is striking and requires further understanding. First, does this pattern also apply to more recent cohorts of American women? Notably, major societal shifts over the past two decades, such as persistent and widening racial and educational gaps in wages and wealth (Gould 2020; Wilson and Rodgers 2016), may have greatly changed racial/ethnic and educational patterns in fertility for those born after 1964. Second, previous studies on this topic using nationally representative data compare only White and Black women. Hispanic women of all races have been neglected in the comparison. In recent decades, Hispanics constitute almost 18% of the U.S. population (Hugo-Lopez et al 2021), with evidence of projected growth (US Census Bureau 2017). Fertility behaviors of Hispanics differ from non-Hispanics and are therefore important to include in the comparison (Parrado and Morgan 2008). Third, previous studies have mostly focused on completed total fertility only, whereas other useful quantities, such as parity-specific fertility levels and timing, have been less commonly examined. Parity-specific fertility levels and timing can better capture women’s fertility decision making process, which is typically sequential (i.e., the decision on whether to have a next birth depends on time since the last birth, etc.) (Retherford et al 2010). Finally, previous studies have not taken unobserved heterogeneity into account when modeling birth processes, which may lead to biased estimates (Heckman and Walker 1990; Zang 2019).

This study examines the interplay between race/ethnicity and education in fertility, including total fertility rates (TFR), Parity Progression Ratios (PPRs), and parity-specific probability of having a birth by age or duration since last birth, for cohorts of U.S. women born during 1960–80. Specifically, we address the following questions: for each level of educational attainment, how do fertility levels compare across racial/ethnic groups? If racial/ethnic difference exists, is it driven by racial/ethnic differences in first births or higher-order births? Or is it driven by fertility timing differences across race/ethnicity? Women born during 1960–80 make up a large portion of the current U.S. labor force and their labor force participation rate is lower compared to their baby boomer counterparts (Vere 2007). Yet their fertility behaviors have not been paid adequate attention (Zang 2019). Understanding their fertility behaviors may help us understand their labor force participation behaviors. Using four waves of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) from 2006 to 2017, we model parity-specific birth processes accounting for unobserved heterogeneity to estimate fertility quantities for White, Black, and Hispanic women with three levels of educational attainments: below high school, high school, and college or above.

We make four contributions to the existing literature. First, we examine the role of the interaction between race/ethnicity and education in shaping fertility levels for a more recent cohort compared to previous studies. Second, we examine parity-specific fertility levels and timing in addition to completed fertility, which can improve our understanding of the completed fertility patterns. Third, besides Black and White women, we additionally consider Hispanic women, who have very different fertility behaviors compared to White and Black women and have been less studied. Finally, we account for unobserved heterogeneity when modelling birth processes, which can help avoid obtaining biased estimates.

Explaining Racial/Ethnic and Educational Differences in Completed Fertility

Existing theories explaining the interplay between race/ethnicity and education in fertility are mainly from work conducted before the 1990s, and empirical evidence examining these theories is mixed. A summary of these theories and their related empirical studies is provided in Appendix A1. In recent decades, major societal shifts have occurred, and therefore theories developed in the past may not be able to explain the current interplay between race/ethnicity and education in fertility patterns. The Second Demographic Transition (SDT) summarizes some of the shifts in family formation from the 1970s onward, especially alternative relationship structures to marriage and a decoupling of childbearing and marriage (Lesthaeghe 2014). The latter is articulated through a delay in marriage, more so than first births, and more births occur in nonmarital contexts (Guzzo and Hayford 2020). These trends have had differential impacts on racial/ethnic groups and individuals with different educational levels (Guzzo and Hayford 2020). In this section, we therefore focus on building our arguments based on more recent literature in demography and family.

Evidence in the past two decades has shown that completed fertility is negatively associated with women’s educational attainments (Musick et al 2009), and that Hispanic women have the highest completed fertility, followed by Black and then White women (Finer and Henshaw 2006). These studies have also established that differences in completed fertility across both racial/ethnic and educational groups are largely driven by differences in unintended births (Musick et al 2009; Sweeney and Raley 2014). The research has highlighted two aspects that may have played an important role in shaping these differences: 1) access to contraception and contraceptive self-efficacy (Eeckhaut 2020; Musick et al 2009; Sweeney and Raley 2014), and 2) relationship and economic contexts (Musick et al 2009; Sweeney and Raley 2014).

Contraception

Highly educated women tend to have better access to reproductive health services (Hayford and Guzzo 2016; Musick et al 2009), and they tend to have more effective contraceptive use to prevent unintended pregnancies when compared to their less-educated counterparts (Hummer and Hamilton 2010). In particular, over the last ten years, abortion restrictions in certain states, such as long mandated wait times, mandatory counseling, pregnancy stage limits, strict facility standards, shutdowns of accessible clinics, and restrictions based on age, have disproportionately limited access to abortion among less-educated women (Guzzo and Hayford 2020). In addition, many private physicians do not accept Medicaid and in many states, Medicaid does not cover abortion costs (Boonstra et al 2006; Musick et al 2009). Conditional on having access to contraception, a lack of efficacy and a sense of control over one’s life has prevented less-educated women from consistently using effective contraception (Edin and Kefalas 2011; Mirowsky and Ross 2007).

When it comes to racial/ethnic differences, White women have the highest use of contraception in comparison to Hispanic and Black women (Kavanaugh and Jerman 2018). One important reason may be that Black and Hispanic families tend to be more religious compared to Whites (Schieman 2010), and religiosity is negatively linked to contraceptive use (Anyawie and Manning 2019). The differences in contraceptive use of Black and Hispanic women should also be placed within the historical and social contexts specific to them. For example, Black and Hispanic women may be mistrustful of birth control methods as a result of coercive population policies and over-counseling for birth control and sterilizations (Bell et al 2018). Migration experience and religiosity are particularly important in shaping the shared pro-natalist beliefs among Hispanic women (Landale and Oropesa 2007; Westoff and Marshall 2010).

Less educated, Black, and Hispanic women are more likely to experience instability in their access and coverage of contraception services, which may shape their preferences for more permanent contraception (Hayford et al 2020). At the same time, there is evidence that less educated Black and Hispanic women are more likely to be counseled for sterilization procedures in routine reproductive health counseling than White women, due to an extension of coercive overpopulation policies (Borrero et al 2009). Using data from 2006 to 2015, Eeckhaut (2020) estimated that 26.7% of White women, 38.4% of Hispanic women, and 44% of Black women had sterilization. The corresponding number was 56.5% for women with less than high school education, 44.9% for those with high school degrees, and 12.6% for those with college degrees (Eeckhaut 2020).

Contraceptive use is also highly dependent on fertility intentions. Although women with higher education have historically had fewer children than their less educated counterparts, there is little evidence that they actually want or intend to have fewer children (Musick et al 2009). Educational pairings in partnerships may influence women’s fertility intentions (Morales 2020). Fertility intentions, especially when observed over the life course, are also unstable (Heaton, Jacobson, and Holland 1999, Hayford 2009). Past work shows that Hispanics on average prefer larger family sizes and are more likely to exceed their fertility intentions (Hartnett 2014). Ideal family sizes are especially large among foreign-born Hispanics (Hartnett and Parrado 2012). Some research has found that Black women have more desire for pregnancy than White women, and alternative studies have found that Black women are equally ambivalent compared to their White counterparts (Abma et al 2010; Barber et al 2021).

Relationship and Economic Contexts

Dating and marriage markets are heavily demarcated by education. In 2010, women with a college degree had a 90% chance of getting married while women with less than a high school diploma had less than a 75% chance (Hendi 2019). The rates of cohabiting couples transitioning to marriages have also declined steeply for women with no college degree (Kuo and Raley 2016). In addition, college graduates are more likely to marry each other than their less educated counterparts, and trends in educational homogamy increased from 1960 to 2003 (Schwartz and Mare 2005). All this evidence suggests that marriage is increasingly a practice for those with greater access to wealth and stability (Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos 2016). Divorces are also stratified by educational attainment. In 2006 to 2010, divorce rates were 22% for college educated women, 51% for women with only partial college, 59% for women with high school educations, and 61% of women with lower than a high school degree (Copen et al 2012).

The experience of dating and marriage markets also substantially differs for women across racial/ethnic groups. Partially due to a combination of chronic social conditions such as mass incarceration, excessive mortality rates of Black men, over-policing of Black communities, and school-to-prison pipelines, heterosexual Black women face difficulties in finding a partner (Harknett and McLanahan 2004). To a lesser extent, Hispanic women face similar challenges on the marriage market due to similar structural inequalities (Cohen and Pepin 2018; Saenz and Ponjuan 2009). The option and choice of marrying outside of one’s own race also differ by race/ethnicity and education. Hispanics are more likely to marry someone of a different race/ethnicity than Blacks, possibly due to the racial diversity of Hispanic ethnicity (Choi and Tienda 2017). By contrast, marrying outside of their own race is not always an option for Black women due to racial discrimination in the dating market (Bruch and Newman 2018; Feliciano et al 2009; Lewis 2013; Robnett and Feliciano 2011). Black men, particularly those with higher education, are more likely than Black women to intermarry (Torche and Rich 2017), which may be contributing to the decline in marriage prospects for Black women.

The prevalence of cohabitation is similar across young adults within each racial/ethnic group (Manning 2020). However, the nature of cohabitation across race/ethnicity is not the same (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008; Manning and Stykes 2015). Specifically, Black women’s likelihood of a transition from cohabiting to marriage is lower than any other racial group (Zeng et al 2012). Partly driven by the differential patterns in cohabitation, Black and Hispanic women have substantially higher nonmarital fertility rates than White women (Sweeney and Raley 2014). The differential nonmarital fertility rates may also be due to differences in receptivity to nonmarital childbearing (Browning and Burrington 2006). The sense that marriage is a better setting to have children may be an incentive among Whites and those with higher education levels than other groups (Smock and Greenland 2010).

Not only are Black and Hispanic women less likely to be married compared to their White counterparts, but they also experience more instability in their relationships. Relationship instability in general is higher for Black couples than for White and Hispanic couples in both cohabitations and marriages (Smock and Greenland 2010). Among Whites, the higher risk of instability disproportionately concentrates among the less educated, but for Blacks and Hispanics, all educational groups have high risks of instability (Osborne et al 2007). The positive link between relationship duration and effective contraceptive use may explain some of the differences in fertility across racial/ethnic and educational groups (Copen et al 2012; Hummer and Hamilton 2010).

Relationship and economic contexts of fertility are closely related because having a stable partner often brings financial benefits for childbearing. Economic resources certainly account for some of the persistent relationships between race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and fertility. Findings on the relationship between income and fertility are mixed, with more recent studies showing that higher incomes allow parents to afford more children (Black et al 2013; Stulp et al 2016). Infertility treatment is an important aspect through which economic resources may affect fertility. Contrary to the social perception that infertility is a wealthy, White woman’s issue, there have been a number of studies showing that women of lower socioeconomic status and women of color are more likely to struggle with infertility (Bell 2014; Craig et al 2019). This differential infertility pattern may be partly driven by the differential health conditions across racial/ethnic groups. Furthermore, environmental factors such as exposure to toxic chemicals are 5 to 20 times as high in minority neighborhoods than predominantly White ones, which contributes to disease and may affect fecundity (Morello-Frosch and Shenassa Edmond 2006). Despite these differences, White and highly educated women report higher rates of receiving assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) or medical services for infertility than racial minorities and less educated women (Bitler and Schmidt 2006). These differences may reflect inequalities in health care access and insurance coverage (Greil et al 2011). Additionally, the outcome of ARTs also varies by race with Black women experiencing the lowest live birth rate compared to White and Hispanic women (Shapiro et al 2017).

However, it is important to note that the racial/ethnic differences in fertility is not only about socioeconomic differences. Previous studies show that achieving higher educational attainments may not necessarily have protective effects on people of color’s health (Gaydosh et al 2018), which may affect their infertility risks. In addition, Sweeney and Raley (2014) pointed out that racial and ethnic differences in childbearing are greatest among the most advantaged groups of women, indicating that differences are not merely products of economic resources. Pursuing higher education requires economic resources and may in fact be exacerbating the fertility differences across races/ethnicities.

Parity-Specific Fertility Levels and Timing

Current discussions on how the interplay between race/ethnicity and education shapes completed fertility do not actively engage with the sequential birth processes. Considering PPRs is important, as there are substantial educational and racial/ethnic differences in the decision of whether to become a mother (Baudin et al 2015; Sweeney and Raley 2014), and in the experience of transitioning to parenthood (Guzzo and Hayford 2020), which affects mothers’ decisions to have additional children (Margolis and Myrskylä 2015). Zang (2019) shows that PPR1 and PPR3 are negatively associated with women’s education, whereas PPR2 is comparable among those with high school degrees or higher and higher among those without high school degrees. This pattern reflects two heterogeneous groups of college educated women: one stopped after their first births and the other continued to have more than two births (Zang 2019). In terms of racial/ethnic differences, Hispanics have the highest PPR1, followed by Black, and then White women (US Census Bureau 2010). However, racial/ethnic differences in PPR2 and PPR3 have been less examined in the US, despite some evidence that a higher proportion of Hispanic women have three or more births compared to Black and White women (Sweeney and Raley 2014).

Fertility timing has been found to play an important role in completed fertility when examining the interaction between race/ethnicity and education (Yang and Morgan 2003), and parity-specific fertility timing captures this information reflecting the sequential birth processes. Life stability and access to resources, which tend to be positively associated with education, are linked to lower ages at first sex experiences (de Looze et al 2012). Staying in school may act as a protector against early “sexual debut” because it increases an individual’s chances of receiving sexual education (Vella et al 2014). Zang (2019) estimates that women without college degrees tend to have their first births before age 30 whereas women with college degrees tend to have their first births in early 30s. The latter tend to space their second births a little closer to their first births compared to their less educated counterparts, and comparable years since last birth are observed across all educational groups for third births (Zang 2019). Racial/ethnic differences in parity-specific timing have been less examined, despite some evidence that the mean age of first births among Black women is the lowest, followed by Hispanic, and then White. Neighborhood characteristics, family structure, discrimination, and residential segregation can account for some of these racial/ethnic differences (Grollman 2017).

The Interplay Between Race/Ethnicity and Education

Existing studies examining how the interaction between race/ethnicity and education shapes fertility levels in the United States are limited. Early work along this line has found that Black women have higher completed fertility than White women only among those without college degrees (Johnson 1979; Yang and Morgan 2003). More recent work has found that, in contrast to the pattern among women without college degrees, Black women with college degrees have lower completed fertility compared to their White counterparts (Musick et al 2009). The findings in Musick et al (2009) also suggest that the racial differences among women without college degrees may be largely driven by differences in unintended births (i.e., Black women having more unintended births), whereas the racial differences among women with college degrees may be largely driven by differences in intended births (i.e., Black women having fewer intended births). Finer and Henshaw (2006) find that among women living in poverty, Hispanic women have the highest unintended pregnancy rates, followed by Black and then White, whereas among those not living in poverty, Black women have the highest unintended pregnancy, followed by Hispanic, and then White. Sweeney and Raley (2014) further suggest that racial differences in childbearing behaviors may be the greatest among highly educated women relative to less educated women.

Studies examining the role of the interaction between race/ethnicity and education in shaping contraception and relationship contexts may help us better understand the patterns of completed fertility. Kramer et al (2018) finds that the interaction does not significantly predict effective contraceptive use, such as long-acting reversible contraceptive use. Eeckhaut (2020) has examined how the interaction predicts sterilization among women, and has found that racial/ethnic differences were more pronounced among more-educated women compared to their less-educated counterparts. Compared to their White counterparts, more-educated Black women, and to a lesser extent, Hispanic women, are more likely to rely on sterilization, possibly because they are more likely to encounter this contraceptive method due to the history of forced sterilization within their communities, or to avoid frequent contact with medical professionals due to the history of racism within the health care system (Eeckhaut 2020).

Higher education may also have an interactive effect with race/ethnicity on fertility intentions. Higher educated Black women may have better knowledge of the history of mistreatment of Black mothers in the U.S. medical and education system, which may negatively affect their thinking about having children (Rosenthal and Lobel 2011). Similarly, experience of discrimination may also negatively affect fertility intentions. Highly educated Black women may be exposed to high levels of racial discrimination and stereotyping because they are more likely to be in workplaces that are dominated by Whites compared to their less educated counterparts (Colen et al 2006). By contrast, highly educated Hispanic women may be able to navigate the “fluid colorism boundaries” and avoid certain structural racisms faced by Black women (Thompson and McDonald 2016). Hispanics with lighter complexions have higher socioeconomic status and face less discrimination than those with darker complexions and their Black counterparts (Espinosa et al 2019).

When it comes to relationship contexts, the challenges Black and Hispanic women face on the dating and marriage markets are particularly great in urban and higher educated settings (Cohen and Pepin 2018; Kusunoki et al 2016; Saenz and Ponjuan 2009). Black women are more likely than their White counterparts to postpone marriage or avoid marriage altogether than to marry a partner with less education (Lichter et al 1995). One piece of evidence on the interplay between race/ethnicity and education shows that enrollment in school reduces nonmarital conception risks, but this educational dampening effect is less pronounced for Black women than for White and Hispanic women (Upchurch et al 2002). Relatedly, highly educated Black and Hispanic women are more likely to be in student loan debt, but debt only negatively impacts Hispanic women’s likelihood of becoming a mother (Min and Taylor 2018). Black women with debt are actually more likely to transition to motherhood (Min and Taylor 2018).

Research Strategy and Hypotheses

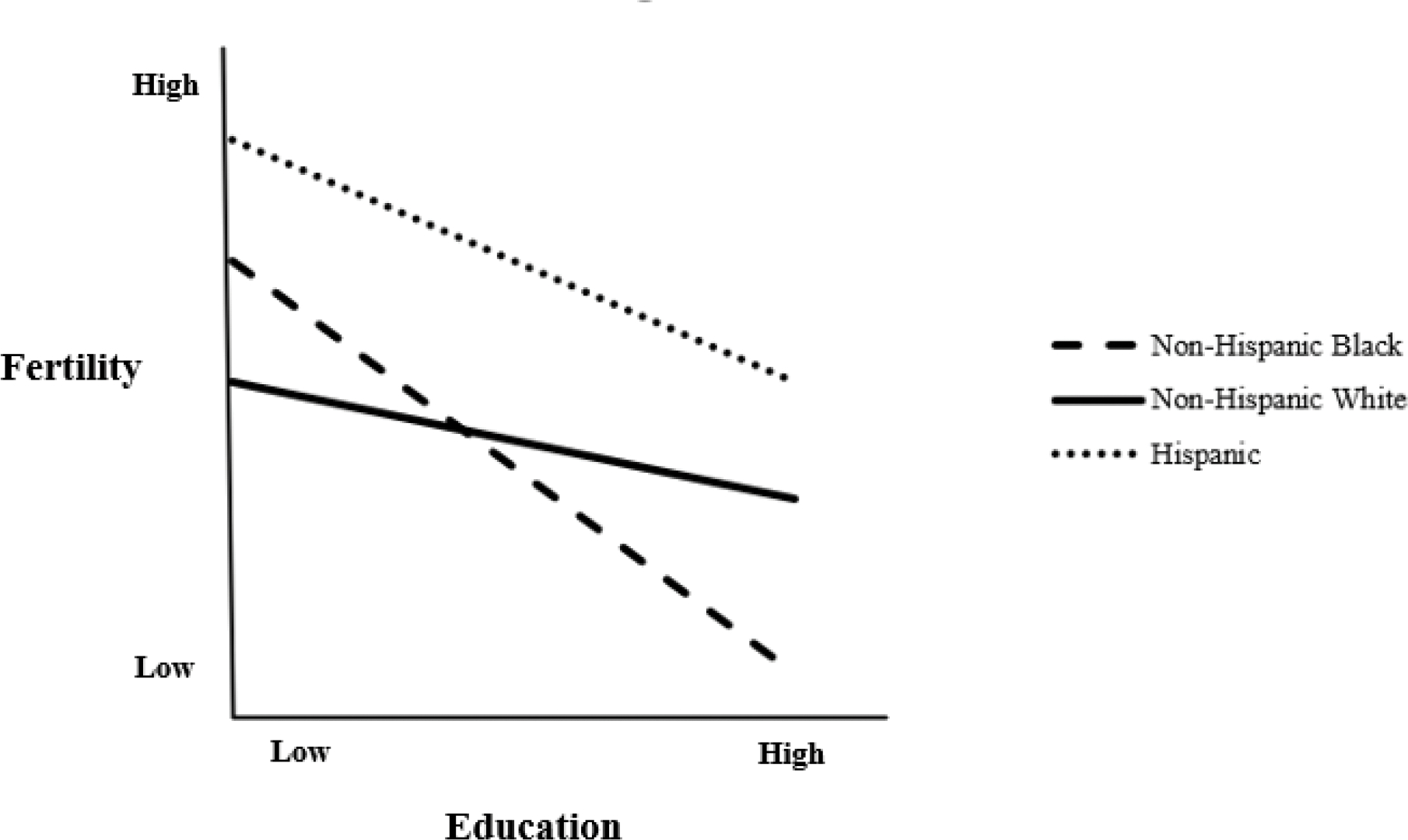

All the evidence above suggests that we should expect interactive effects by race/ethnicity and education in fertility levels. In particular, we would expect that the educational gradient among Black women should be steeper compared to Hispanic women, and, to a greater extent, White women, because highly educated Black women’s contraceptive behaviors and relationship contexts are more distinct from less educated Black women compared to their White and Hispanic counterparts. Among less educated women, especially those without college degrees, we expect Hispanics to have the highest completed fertility, followed by Black and then White. This racial/ethnic pattern has been observed among all educational groups combined (Finer and Henshaw 2006), and it is likely driven by racial/ethnic differences in unintended births, which tend to concentrate among the less educated (Musick et al 2009). Among the more educated women, especially those with college degrees, we expect Hispanics to have the highest completed fertility, followed by White, and then Black. Previous studies suggest that racial differences among the more educated are largely driven by differences in intended births (Musick et al 2009). As discussed in the previous section, compared to their White and Hispanic counterparts, highly educated Black women face greater challenges on the dating and marriage markets, more often need to forgo children for their career, and are more likely to use permanent contraception. Highly educated Hispanics may still have higher fertility levels than their White counterparts, because they still tend to have larger ideal family sizes and do not appear to experience the same disadvantages that their Black counterparts are facing. We summarize our hypotheses in Figure 1.

Figure. 1.

Theoretical predictions of racial/ethnic and educational disparities in fertility levels

Using data on women’s detailed educational and birth histories and multivariate hazard models, we estimate cohort TFRs by education and race/ethnicity to examine the hypotheses described above. In particular, to fill the gaps in existing literature, we examine more recent birth cohorts born during 1960–80, consider Hispanic women in addition to Black and White women, and account for unobserved heterogeneity in the birth processes by applying multilevel multiprocess hazard models. We additionally estimate two sets of fertility quantities that have been less examined but can help us better understand the role of the interaction between race/ethnicity and education in the birth processes: PPRs and parity-specific timing.

One of the contributions of our analyses is the inclusion of Hispanic in addition to White and Black women. The Hispanic population is greatly heterogeneous, and their fertility behaviors depend on country of origin and nativity status (Sweeney and Raley 2014). Unlike foreign-born Hispanic women, Hispanics born in the U.S. bore children at comparable rates to other racial/ethnic groups born in the U.S (Sweeney and Raley 2014). In particular, Mexican-origin women’s fertility levels have been considered as the driving force behind higher Hispanic fertility in the U.S. (Lichter et al 2012; Parrado and Morgan 2008). One traditional explanation is that Mexican-origin women immigrate to the U.S. with pronatalist norms and engrain these norms withing U.S. native-born Mexican populations (Frank and Heuveline 2005), and these pronatalist norms can be especially strong for Mexican-origin immigrants because of frequent movement back and forth between country of origin and large amounts of contact with their country of origin, preserving, reinforcing, and reproducing pronatalist cultural norms (Carter 2000). However, more recent scholarship has begun pushing for a more nuanced understanding of the highly complex process of assimilation and for including an analysis of racial and ethnic structural conditions (Ayala 2017; Portes 2007). Exhaustive examinations of the heterogeneity related to nativity status and country of origin are beyond the scope of this study. Instead, we refer interested readers to Landale and Oropesa (2007) for a review. However, in Appendix A2, we provide results for Hispanics by foreign-born status to provide some insights.

Data and Measures

Our data come from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG)’s most recent waves collected in 2006–10, 2011–13, 2013–15, and 2015–17. It is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey dataset. It collects a large span of information about families and reproduction through in-home interviews with women aged 15–44 in the United States. Starting from 2015, the age range of women has been extended to 15–49. In particular, the NSFG collects information on event histories for each individual, including education, birth, and marital relationships. Using the dates of these events, we convert the cross-sectional sample into person-year records so that one observation is generated for every year of the respondent’s life. More details on this dataset including sampling strategy can be found on its website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/index.htm).

We limit our sample to birth histories during ages 15–44 (or 49 for the 2015–17 wave) for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic women born between 1960 and 1980. For women born later than 1973, we are not able to follow them to age 44 because we only have data up to 2017. This right-censoring issue is largely handled by our modeling strategy. Due to our analytical strategy to model parity-specific birth, we exclude 276 women who had multiple births (e.g. twins). We additionally limit the sample to the first three births for each woman because the number of individuals with more than three births is too small to be modeled. Our sample observes each woman until they reach age 45 (or 50 for the 2015–17 wave), have three children, or are censored. The final sample includes 11,117 women with 229,827 person-year observations.

Birth outcomes are coded as binary variables indicating whether a first, second, or third birth occurred. Observations that are censored in the survey or do not take place during the risk period are coded as missing for the discrete-time event history analyses. We compare three self-reported racial/ethnic categories: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic. We use the word “Hispanic” in this study, consistent with the usage in the majority of the demography literature. We are aware of, however, a debate in Latino/a studies about the word Hispanic (Gimenez 1989). In our sample, the majority of Hispanic women self-identified as White Hispanic, and around 60% of them are of Mexican descent only. This percentage is consistent with that for the national Hispanic population (Noe-Bustamante 2019), providing more confidence in the representativeness of our Hispanic fertility estimates.

The NSFG collects the dates of obtaining high school and college degrees for each individual. Based on this information, we imputed individuals’ highest educational attainment at each age: below high school, high school (including GED), and college or higher. Although information on the highest educational attainment is also available in the survey and has finer categories than just high school and college, we choose the time-varying education measure to avoid an underestimation of its impact on higher-order births following existing studies (Kravdal 2007). A detailed discussion of the pros and cons using current education (i.e. time-varying) versus the highest educational attainments can be found in Kravdal (2007).

There are many variables that may complicate the relationship between race, education, and fertility. We model fertility behaviors as a function of age, family background, religious affiliation, current union status, foreign-born status, birth year, and sex composition of the first two births, besides educational attainments. This is not an exhaustive list of confounders, but the purpose of controlling for them is to improve the precision of our predictions by reducing sampling errors rather than obtaining causal estimates of education or race/ethnicity. We provide robustness checks including only a function of age and duration since previous birth as covariates in Appendix Table A2, and the results are highly consistent with our main results with a full list of controls. We use a woman’s mother’s highest educational attainment to capture her family background. It is a time-constant variable including the following categories: less than high school, high school (including GED), some college (including two-year degrees), and bachelor’s degree or higher. Religious affiliation is time-constant measured at the time of the survey and includes the following categories: no religion, Catholic, Protestant, or other religion. Based on information on the starting and ending dates of each marriage or cohabitation relationship, we imputed union status at each age. It is a time-varying variable including the following categories: never in a union (i.e. single and not cohabiting), in a union (i.e. married or cohabiting), or union ended (i.e. separation, divorce, or widowhood). Foreign-born status is a dummy variable indicating whether an individual was born outside of the United States. Sex composition of first two births is coded as a dummy variable to indicate whether the first two children are of the same sex. This variable is only included when modeling third births. Existing theories posit that due to the popular preference for mixed-gender children among US parents, if the first two births have the same gender, parents are more likely to have a third birth hoping to have a child with different gender (Pollard and Morgan 2002). We divide all birth years into four 5-year birth cohorts: 1961–65, 1966–70, 1971–75, or 1976–80.

Table 1 displays sample characteristics by race/ethnicity. We observe some interesting racial disparities in socioeconomic characteristics. White women spent the greatest proportion of years with college degrees (25.2%), compared to Black (12.4%) and Hispanic (9.5%) women in the sample. Hispanic women spent 45.3% of their years without a high school diploma, compared to 28.6% of Black women and 21.3% of White women. Black women spent 68.8% of their years being single compared to about half in the other two racial/ethnic groups. Hispanics also seem to have the most disadvantaged family background measured by their mothers’ educational attainments. A plurality of Blacks and Whites were Protestant, whereas most Hispanics were Catholic. Almost 60% of Hispanic observations are foreign-born, compared to 5% among Whites and 10% among Blacks.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics

| Non-Hispanic White |

Non-Hispanic Black |

Hispanic |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | # of Individuals | # of Person-Year Observations | Mean/Proportion (%) | # of Individuals | # of Person-Year Observations | Mean/Proportion (%) | # of Individuals | # of Person-Year Observations | Mean/Proportion (%) |

|

| |||||||||

| Dependent variables | |||||||||

| First birth observed | 6,102 | 87,805 | 5.0 | 2,322 | 25,824 | 7.2 | 2,671 | 28,751 | 8.0 |

| Second birth observed | 4,405 | 24,330 | 12.8 | 1,858 | 11,866 | 11.4 | 2,307 | 11,866 | 15.4 |

| Third birth observed | 3,109 | 21,682 | 5.7 | 1,340 | 9,060 | 8.1 | 1,822 | 11,001 | 9.8 |

| Independent variables | |||||||||

| Current completed education | 6,107 | 145,402 | 100.0 | 2,333 | 54,752 | 100.0 | 2,677 | 61,726 | 100.0 |

| Below high school or GED | 21.3 | 28.6 | 45.3 | ||||||

| High school or GED | 53.5 | 59.1 | 45.2 | ||||||

| College | 25.2 | 12.4 | 9.5 |

||||||

| Current union status | 6,107 | 145,402 | 100.0 | 2,333 | 54,752 | 100.0 | 2,677 | 61,726 | 100.0 |

| Never in a union | 47.0 | 68.8 | 49.6 | ||||||

| In a union | 42.9 | 22.5 | 41.2 | ||||||

| Union ended | 10.1 | 8.7 | 9.2 | ||||||

| Mother’s highest completed education | 6,048 | 144,000 | 100.0 | 2,312 | 54,227 | 100.0 | 2,650 | 61,107 | 100.0 |

| Less than high school | 14.5 | 29.4 | 61.6 | ||||||

| High school or GED | 38.7 | 36.1 | 18.9 | ||||||

| Some college, including 2-year degrees | 24.5 | 20.1 | 11.5 | ||||||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 6,048 | 22.4 | 14.4 | 8.0 | |||||

| Religious affiliation | 6,107 | 145,402 | 100.0 | 2,333 | 54,752 | 100.0 | 2,677 | 61,726 | 100.0 |

| No religion | 23.4 | 9.5 | 13.3 | ||||||

| Catholic | 18.9 | 6.8 | 54.9 | ||||||

| Protestant | 48.7 | 79.9 | 27.9 | ||||||

| Other religion | 9.0 | 3.9 | 3.9 | ||||||

| Duration since the first birth | 4,400 | 24,311 | 5.7 (5.2) | 1,847 | 11,811 | 6.4 (5.6) | 2,301 | 11,848 | 6.4 (4.3) |

| Duration since the second birth | 3,109 | 21,682 | 6.2 (4.9) | 1,340 | 9,060 | 6.4 (5.3) | 1,822 | 11,001 | 5.4 (4.4) |

| Foreign born | 6,105 | 145,360 | 5.0 | 2,332 | 54,732 | 10.2 | 2,676 | 61,706 | 58.7 |

| The first two births have the same sex | 3,123 | 76,141 | 49.5 | 1,350 | 32,027 | 52.5 | 2,677 | 42,680 | 51.3 |

Source: National Survey of Family Growth 2006–2010, 2011–2013, 2013–2015, and 2015–2017 waves.

Empirical Strategy

We follow the approach adopted in Zang (2019) and apply multilevel multiprocess hazard models to examine the association between women’s educational attainments and transitions to first, second, and third births by race/ethnicity. This regression-based approach allows us to obtain precise predictions through the inclusion of covariates to reduce sampling errors and controlling for selection into higher-order births. Compared with the traditional approach of modelling the progression to each parity of birth separately, this approach reduces bias by allowing us to model progressions to each birth jointly nested within each individual and accounting for unobserved individual characteristics that are relatively stable over time, such as fecundity and preference for children (Zang 2019). Following the notations in Zang (2019), the detailed model specifications are:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

For each individual i at time j, h(j) is the hazard of having an observed birth of order j. α(j) represents the constant term. β(j)s are vectors of coefficients for age polynomials, women’s education, and their interaction terms. Interaction terms between age polynomials and women’s education are included in equation (1) because previous studies have shown that the relationship between women’s education and first birth rate varies by age (Rindfuss et al 2007). θ(j)s are the vectors of coefficients for duration since last birth polynomials. γ is the vector of coefficients for the matrix of control variables X(j). Our control variables include women’s mothers’ highest completed education level, religious affiliation, current union status, foreign-born status, and birth cohort. Sex composition of the first two births is also used to predict having a third birth. δ(j) is a coefficient matrix for a person-specific unobserved latent factor matrix U, which is assumed to include time-invariant unobserved factors independent of age, education, and other controls. We used the Stata package ‘gsem’ (Bartus 2017) to estimate all models for each race/ethnicity group.

Using the model coefficients, we predict the conditional probabilities of having a first, second, and third birth for each individual at each age or each year since last birth. These predicted individual conditional probabilities incorporate information on the unobserved heterogeneity by predicting with empirical Bayes mean predictions of the latent variable U for each person-year observation. Under common assumptions such as normality and representativeness of the covariate profiles in our data, we calculate the probabilities of having a j+1’s birth conditional on having a j’s birth at each age or each year since last birth for each racial/ethnic and educational combination from the individual probabilities. More specifically, for each time t, and for each race-education combination, we can estimate , or by calculating the mean of in our data where i is each individual. Parity-specific fertility timing is shown by plotting these conditional probabilities by age or duration since previous birth for each education and race/ethnicity combination. For each education and race/ethnicity combination, we calculate PPRs using the equation below:

| (4) |

where j represents the order of birth, t represents age or duration since previous birth, and h(j) represents the predicted conditional probability at time t for parity j. We then use the PPRs to calculate the cohort TFR of each education-race combination:

| (5) |

Due to sample size concerns, we are not able to examine cohort variation in fertility reliably. However, our robustness checks in Appendix Figure A2 showing fertility patterns by 10-year birth cohorts suggest that we are not masking important heterogeneity that exist between the two 10-year birth cohorts.

Results

Results from Simultaneously Modelling Birth Outcomes

Table 2 presents the parameter estimates relating to equations (1)–(3). Among all racial/ethnic groups, holding other variables constant, having a college degree or not having completed high school was associated with a lower hazard of becoming a mother compared to those with only a high school degree. These results suggest a U-shaped relationship between educational attainments and childlessness, consistent with prior studies in the literature (Zang 2019).

Table 2:

Women’s current education and transition to a first, second, and third birth, by race/ethnicity

| Non-Hispanic Whites |

Non-Hispanic Blacks |

Hispanic |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | First birth | Second birth | Third birth | First birth | Second birth | Third birth | First birth | Second birth | Third birth |

|

| |||||||||

| Women’s current education (Ref=HS, β3) | |||||||||

| Below HS | −8.495*** (1.154) | 0.421*** (0.0774) | 0.386*** (0.117) | −10.11*** (1.404) | 0.531*** (0.0989) | 0.335** (0.146) | −5.807*** (1.084) | 0.348*** (0.0759) | 0.488*** (0.105) |

| College | −15.11*** (1.456) | 0.308*** (0.0595) | 0.353*** (0.0983) | −8.419*** (3.086) | −0.231* (0.130) | −0.262 (0.207) | −13.12*** (3.425) | 0.195* (0.113) | −0.0760 (0.166) |

| Age-education interactions | |||||||||

| Below HS × Age | 0.838***(0.106) | 0.860*** (0.128) | 0.511*** (0.0909) | ||||||

| College × Age | 0.879*** (0.0973) | 0.459** (0.208) | 0.766*** (0.226) | ||||||

| Below HS × Squared Age | −0.0184*** (0.00240) | −0.0165*** (0.00284) | −0.00967*** (0.00185) | ||||||

| College × Squared Age | −0.0123*** (0.00161) | −0.00619* (0.00347) | −0.0112*** (0.00369) | ||||||

| δ | 1 | 1.076*** (0.172) | 1.718*** (0.340) | 1 | 0.835*** (0.134) | 1.074*** (0.377) | 1 | 0.636*** (0.141) | 0.668*** (0.242) |

| var(U) | 0.262*** (0.0503) | 0.262*** (0.0503) | 0.262*** (0.0503) | 1.234*** (0.264) | 1.234*** (0.264) | 1.234*** (0.264) | 0.758*** (0.138) | 0.758*** (0.138) | 0.758*** (0.138) |

| N | 132,475 | 132,475 | 132,475 | 46,264 | 46,264 | 46,264 | 51,088 | 51,088 | 51,088 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

This table shows the parameter estimates relating to equations (1) to (3) in the text, and the Greek letters also correspond to those in equations (1)–(3). All rates are modelled jointly with common unobserved factors, and control for age, age square, religion, current union status, mother's highest education, foreign-born status, and birth cohorts. In the first equation, the interaction between education and age, as well as the interaction between education and age square are also controlled. In the second and third equations, duration since last birth and its square are also controlled. In the third birth equation, whether the first two children have the same gender is also controlled. HS refers to high school.

The patterns appeared different across racial/ethnic groups for higher order births. For Whites, we observe an inverse U-shaped relationship, with higher hazards of second and third births for women with below high school education or a college degree compared to women who had completed only high school. For Black and Hispanic women, those with less than high school education had greater hazards of having a second or third birth compared to women with only high school education. However, college-educated Black women had a lower hazard of having a second birth compared to their high-school educated counterparts, whereas Hispanic women had a higher hazard. For third births, the coefficients for college educated Black and Hispanic women are both negative, although not statistically significant due to the relatively small number of college-educated minority women in our sample. These results suggest that college education predicts lower probabilities of second or/and third births among Black and Hispanic women, whereas we do not observe the same depressive patterns among White women.

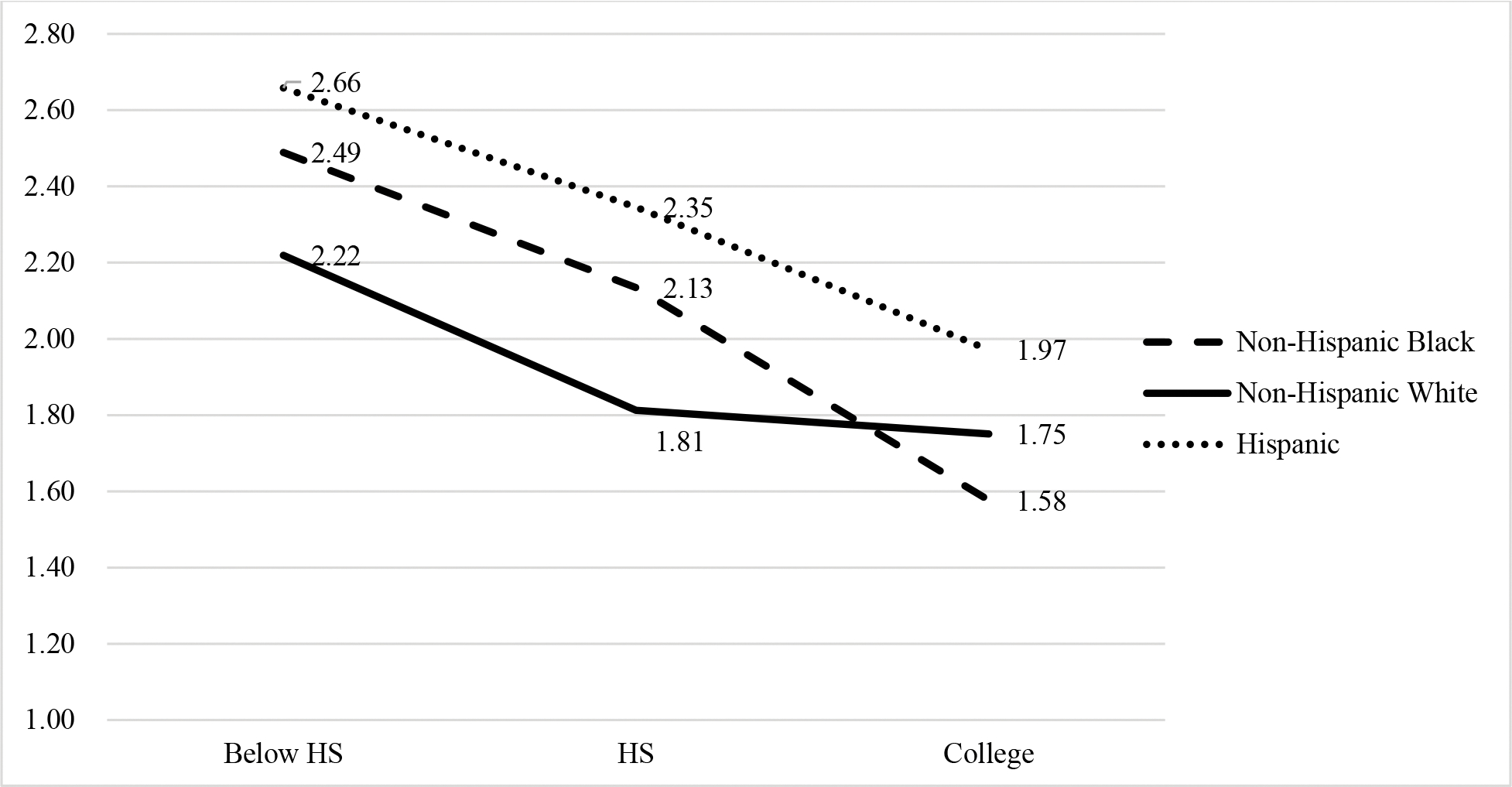

Racial and Educational Disparities in Fertility Levels

We calculate the cohort TFR for each educational category by racial/ethnic groups. Results are presented in Figure 2. Within each racial/ethnic group, the higher the educational attainments, the lower the TFR. Hispanic women had the highest fertility at all levels of education. Among women with high school education or below, Black women had greater fertility levels than White women. However, among college-educated women, Black women had the lowest fertility. The difference among college educated Hispanic and White women was smaller compared to their less educated counterparts. These patterns are generally consistent with our predictions in Figure 1.

Figure. 2.

Racial/Ethnic disparities in predicted Cohort Total Fertility Rate (CTFR) by education

Source: National Survey of Family Growth 2006–17 waves.

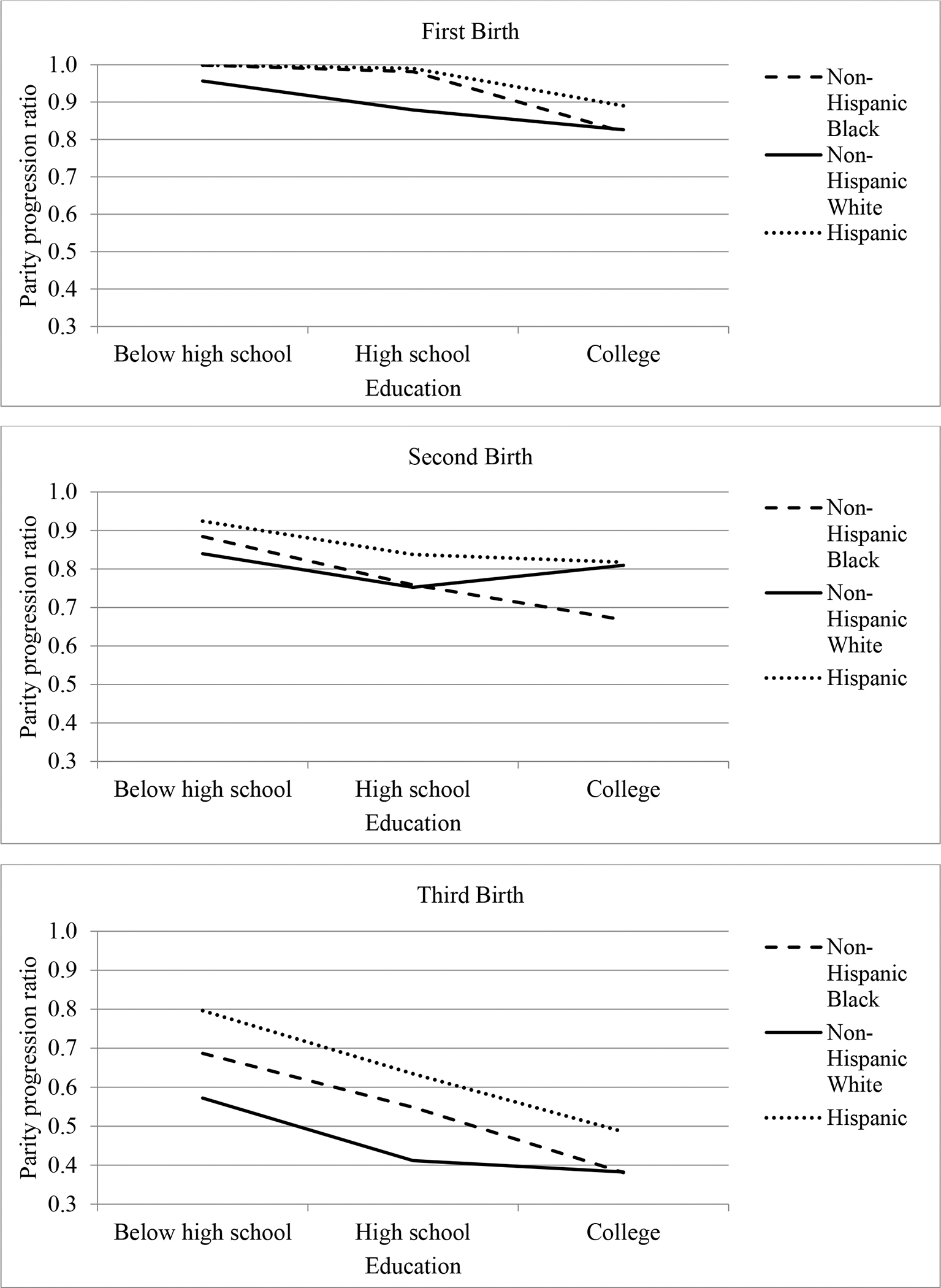

Was the fertility among college educated Black women lower because many of them completely gave up on having children or many of them only had one child? Figure 3 shows the parity progression ratios (PPR) for first, second, and third births. Our estimated PPR1s suggest slight lower childlessness rates than the period estimates in previous studies on childlessness (e.g. Rybińska 2020). This is because our cohort approach considers all births born to women who lived past age 15 whereas the typical period approach considers all births born to women aged 40–44 conditional on being alive. The PPR1s for college educated Black and White women were comparable, suggesting that the lower TFR for college educated Black women is not driven by a lower proportion of them becoming mothers. However, it is striking to see that college educated Black women had a much lower PPR2 compared to the other racial/ethnic groups. The magnitude of the Black–White gap in PPR2s was more than 10 percentage points. This means that among mothers who already had one child, the proportion of Black mothers who went on to have a second child is more than 10 percentage points lower than that of White mothers. It is also interesting to observe that college educated Whites had a higher PPR2 than their counterparts without a college degree, which was even comparable to the PPR2 for college educated Hispanics. No gaps are observed between Black and White women in PPR3. These results suggest that while a comparable proportion of Black college educated women became mothers as their White counterparts did, fewer of them continued to have second children.

Figure. 3.

Racial disparities in predicted parity progression ratios to first, second, and third birth by educational level

Source: As for Figure 2.

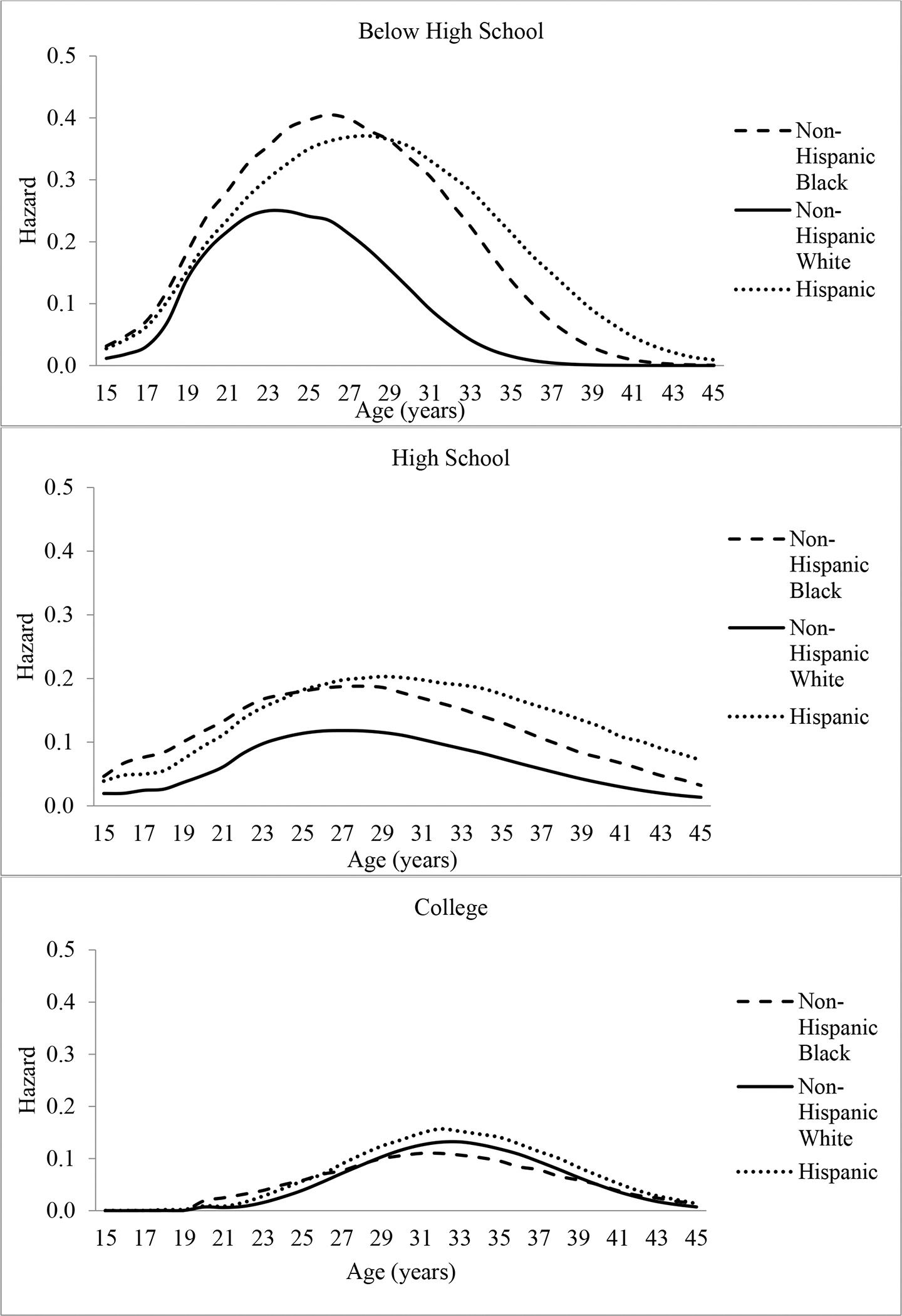

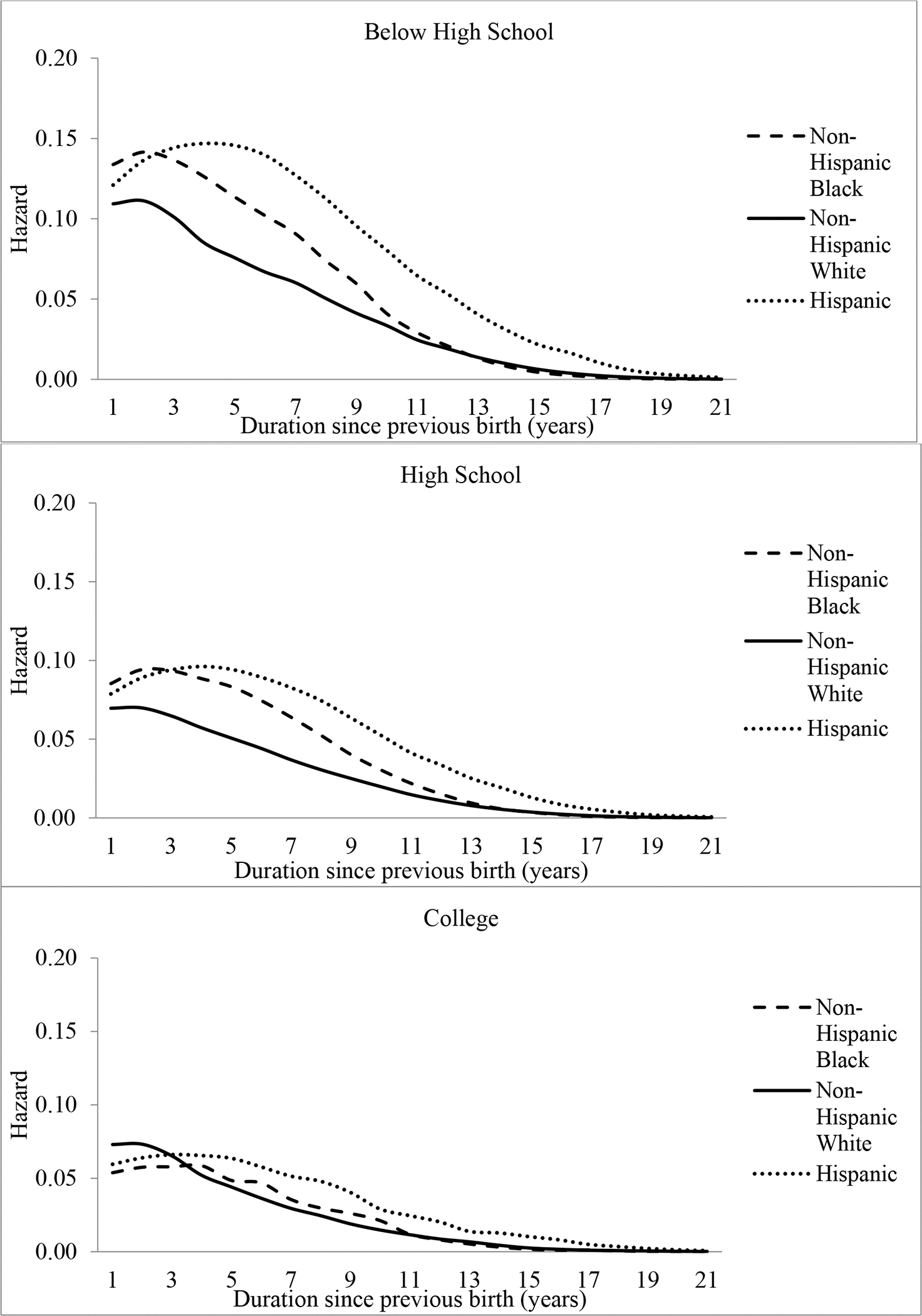

Racial and Educational Disparities in Fertility Timing

Another possible explanation to the lower fertility among college educated Black women is that they postponed first births so much that they did not have enough time to have higher-order births during their reproductive years. Figures 4, 5, and 6 show the fertility timing of first, second, and third births, respectively, by educational levels and racial/ethnic groups. We find no evidence that Black college educated women postponed first births more than the other racial/ethnic groups. College educated women across racial/ethnic groups are most likely to have their first births during ages 30–33. For women without college degrees, we find some evidence that Hispanic women on average had their first births relatively later compared to the other groups. Since our Hispanic sample includes both immigrants and non-immigrants, it is possible that this result is driven by the potential interruption of migration to immigrants’ fertility timing (Parrado and Flippen 2012).

Figure. 4.

Racial disparities in conditional probability of first birth timing by educational level

Source: As for Figure 2.

Figure. 5.

Racial disparities in conditional probability of second birth timing by educational level

Source: As for Figure 2.

Figure. 6.

Racial disparities in conditional probability of third birth timing by educational level

Source: As for Figure 2.

Black women across all educational groups tended to space their second births closer to first births, compared to the other racial/ethnic groups. The close spacing pattern was the least obvious among Hispanic women. Among those without college degrees, the peak of the hazards is observed at 2, 3, and 5 years after first births for Black, White, and Hispanic women, respectively. College educated women of all racial/ethnic groups appeared to peak in probability within 2 years of their first births.

As with first and second births, Hispanic women tended to delay third births by longer compared to White and Black women. Among those without college degrees, peak probability was observed at approximately 2 years after their second birth for White and Black women compared to 4–5 years for Hispanic women. College educated White women, as with their less educated counterparts, peaked in probability at 2 years, whereas Black and Hispanic women peaked at approximately 4 years after their previous parity. The above patterns suggest it is unlikely that Hispanic women had higher fertility because they had first births earlier compared to other racial groups.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study examines completed fertility by the intersection of race/ethnicity and educational attainments for a cohort of U.S. women who are just finishing their reproductive years. We find that racial/ethnic disparities in fertility levels exist not only among women without a college degree, as documented in prior research examining earlier cohorts (Johnson 1979; Yang and Morgan 2003), but also among college educated women. Compared to their White counterparts, Black and Hispanic women without a college degree have higher fertility. However, among college educated women, Black women have lower fertility levels whereas Hispanics have higher fertility levels than Whites. The difference in the TFRs between Black and White college educated women is mainly driven by the smaller proportion of Black mothers (more than 10 percentage points less) having second births. We find little evidence that the observed racial disparities in TFRs across educational levels are driven by fertility timing differences. These results confirm our hypothesis that education plays different roles in shaping fertility levels across races/ethnicities.

This interplay between education and race/ethnicity is likely a result of different social and material realities that shape women’s fertility decisions and their ability to take full control over their childbearing behaviors along racial/ethnic lines. Consistent with our theoretical framework, compared to Whites, we observe steeper educational gradients in completed fertility among Black and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic women. Among women without college degrees, unintended births may have played an important role in driving racial/ethnic differences. Culture, religion, access to health insurance, and historical and social contexts may have prevented less educated Black and Hispanic women from consistently using effective contraception. They are also more likely to experience relationship and economic instability than their White counterparts. By contrast, among women with college degrees, Black, and to a lesser extent, Hispanic women, are more likely to use permanent contraception, possibly due to contraceptive preferences or coercion shaped by historical context, and the fact that structural discrimination makes them often need to forgo children for their career. Highly educated Black, and to a lesser extent, Hispanic women also tend to face greater challenges on the dating and marriage markets compared to their White counterparts.

Our findings also highlight the importance of second births in shaping racial/ethnic fertility differences among college educated women. Among the college educated, the proportion of White mothers transitioning to second births was higher than that among Black mothers. In fact, it was even higher than the proportion among White mothers with a high school diploma. How could college educated White mothers achieve such a high proportion transitioning to second births? Relationship and economic contexts likely have played a role. Given shifting global immigration trends and international instability, highly educated women in the United States, particularly Whites, have had further access to outsource the labor of childcare to low-cost immigrant labor sources (Briggs 2018). Furthermore, compared to their Black and Hispanic counterparts, highly educated White women are more likely to find high-income partners and partners who are willing to share a large portion of child-rearing responsibilities (Torche and Rich 2017).

Our findings have important implications. First, this study is the first to examine the interplay between race/ethnicity and education in three fertility outcomes together: completed fertility, PPRs, and parity-specific timing. Conventional wisdom posits that as minority women’s educational attainment becomes more similar to that of White women, racial/ethnic differences in fertility will disappear. This approach has led previous studies to focus on racial/ethnic disparities in fertility among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups (for a review, see Sweeney and Raley 2014). Our findings show that racial/ethnic disparities in fertility are present for all levels of educational attainments in more recent cohorts. By further disaggregating fertility patterns by education, our results reveal that the apparent convergence in fertility levels between Black and White women is driven by both a smaller positive fertility gap between less educated Black and White women and a greater negative fertility gap between college educated Black and White women. By contrast, the convergence in fertility levels between Hispanic and White women are likely due to smaller positive gaps across educational groups. These results highlight the need for studying racial/ethnic differences in childbearing and family patterns among socioeconomically advantaged women in addition to those disadvantaged groups.

Second, our findings indicate that, compared to White children, there are a greater proportion of Black, and to a lesser extent, Hispanic, children born with less educated mothers and a smaller proportion born with college-educated mothers. Children of highly educated mothers have access to greater resources that may aid their own development and success in life, including greater wealth, more evenly distributed care from their parents, and greater stability; whereas children of mothers with less education have less access to these resources (McLanahan 2004). In other words, Black and Hispanic children, when compared to White children, were disproportionally born in families with fewer resources, which may exacerbate the long-term income and health inequality for the next generation.

There are some limitations of this study that may be addressed with additional data and new computational techniques. Firstly, our TFR estimates are based on the first three births. Assuming that the pattern of more than three births are similar to the pattern of third births, it is possible that we may have underestimated the fertility levels for Hispanic women and those without a college degree. Therefore, the gaps in fertility between non-Whites and Whites may be even larger among women without a college degree than documented in this study and so will the gap between Hispanics and non-Hispanics among college educated women. Second, some respondents in our sample may not have finished their reproductive years in 2017, particularly if they are highly educated. This may lead to an underestimation of TFRs for college educated women. Given that White women have better access to advanced reproductive technologies, the TFR for college educated White women may be even higher, which suggests a larger Black–White fertility gap and smaller Hispanic–White fertility gap (Dieke et al 2017). Third, due to sample sizes and page limits, we cannot fully disaggregate the Hispanic group and examine its heterogeneity in fertility by country of origin or include other racial/ethnic groups other than White, Black, and Hispanic. Fourth, we focus on the intersection between race/ethnicity and education in this study. However, there are other important dimensions in stratification, such as occupation, income, wealth, and class. Examining how their intersections with race/ethnicity may affect fertility will provide additional insights to help us understand fertility disparities. Finally, due to computational challenges, we are not able to estimate the prediction intervals of the conditional probabilities for fertility timing or the standard errors of the TFR and PPR measures. Although our data is nationally representative, it is only one possible realization from sampling the population. Future studies that have access to population data or apply alternative methods, such as a Bayesian approach, are needed to confirm our conclusions. However, our finding that highly-educated Black women have lower fertility compared to their White counterparts is consistent with the findings in previous studies modeling non-parity-specific births (e.g., Musick et al 2009), providing us more confidence in our substantive conclusions.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide important implications for policy and future research. Much of the policy attention in the past has been paid to subgroups with higher fertility than Whites due to social and political concerns with immigration and minority groups (Sweeney and Raley 2014). Little attention has been paid to the steeper declines in fertility levels of highly educated Black and Hispanic women compared to their White counterparts. With more women entering into higher education, highly educated White women appear to increasingly delay marriage and childbirth to older ages and compensate by having higher-order births in greater succession. Although we observe similar delays in marriage and childbirth among highly educated Black and Hispanic women, we also observe a larger proportion of these Black and Hispanic mothers forgoing second births. By providing a descriptive foundation, this study highlights the need to investigate the following questions: Is it because highly educated Black and Hispanic women were more aware of the higher risk of pregnancy related complications among their racial groups, such as miscarriage, infant mortality, and maternal mortality (Ely and Driscoll 2021; Petersen et al 2019; Pruitt et al 2020), which discouraged many of them from wanting to have second births? Is it because highly educated Black and Hispanic women more often needed to navigate “White Spaces” compared to less educated Black and Hispanic women (Anderson 2015), and they did not want to confirm their White colleagues’ stereotype that Black and Hispanic women are highly fertile? Is it because highly educated Black and Hispanic women actually wanted second children but their health prevented them from having one due to long-term chronic stress related to racism? Additional studies are needed to flesh the psychosocial pathways behind this pattern and the roles of social institutions in shaping these pathways.

Supplementary Material

Funding information:

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services >

National Institutes of Health >

National Institute on Aging

R21AG074238–01

Yale University >

Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies

NA

References

- Abma Joyce C., Martinez Gladys M., Copen Casey E. 2010. “Teenagers in the United States: sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, national survey of family growth 2006–2008.” Pp. 1–47. Volume 30. National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Elijah. 2015. “The white space.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1(1): 10–21 [Google Scholar]

- Anyawie Maurice, Manning Wendy. 2019. “Cohabitation and contraceptive use in the United States: A focus on race and ethnicity.” Population Research and Policy Review 38(3): 307–25 [Google Scholar]

- Ayala María Isabel. 2017. “Intra-Latina fertility differentials in the United States.” Women, Gender, and Families of Color 5(2): 129–52 [Google Scholar]

- Barber Jennifer S., Guzzo Karen Benjamin, Budnick Jamie, Kusunoki Yasamin, Hayford Sarah R., Miller Warren. 2021. “Black-White differences in pregnancy desire during the transition to adulthood.” Demography 58(2): 603–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin Thomas, De La Croix David, Gobbi Paula E. 2015. “Fertility and childlessness in the United States.” American Economic Review 105(6): 1852–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell Ann V. 2014. Misconception: Social class and infertility in America. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell Monica C., Edin Kathryn, Wood Holly Michelle, Mondé Geniece Crawford. 2018. “Relationship repertoires, the price of parenthood, and the costs of contraception.” Social Service Review 92(3): 313–48 [Google Scholar]

- Bitler Marianne, Schmidt Lucie. 2006. “Health disparities and infertility: Impacts of state-level insurance mandates.” Fertility and Sterility 85(4): 858–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black Dan A, Kolesnikova Natalia, Sanders Seth G, Taylor Lowell J. 2013. “Are children “normal”?” The review of economics and statistics 95(1): 21–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra Heather D, Gold Rachel Benson, Richards Cory L, Finer Lawrence B. 2006. “Abortion in women’s lives.” Guttmacher Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Borrero Sonya, Schwarz Eleanor B., Creinin Mitchell, Ibrahim Said. 2009. “The impact of race and ethnicity on receipt of family planning services in the United States.” Journal of Women’s Health 18(1): 91–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs Laura. 2018. How all politics became reproductive politics: From welfare reform to foreclosure to Trump. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Browning Christopher R., Burrington Lori A. 2006. “Racial differences in sexual and fertility attitudes in an urban setting.” Journal of Marriage and Family 68(1): 236–51 [Google Scholar]

- Bruch Elizabeth E., Newman MEJ. 2018. “Aspirational pursuit of mates in online dating markets.” Science Advances 4(8): eaap9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter Marion. 2000. “Fertility of Mexican immigrant women in the US: A closer look.” Social science quarterly: 1073–86 [Google Scholar]

- Choi Kate H., Tienda Marta. 2017. “Marriage-Market Constraints and Mate-Selection Behavior: Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Differences in Intermarriage.” Journal of Marriage and Family 79(2): 301–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Philip N., Pepin Joanna R. 2018. “Unequal Marriage Markets: Sex Ratios and First Marriage among Black and White Women.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 4: 1–10 [Google Scholar]

- Colen Cynthia G., Geronimus Arline T., Bound John, James Sherman A. 2006. “Maternal Upward Socioeconomic Mobility and Black–White Disparities in Infant Birthweight.” American journal of public health 96(11): 2032–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copen Casey E., Daniels Kimberly, Vespa Jonathan, Mosher William D. 2012. “First marriages in the United States: data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth.” Pp. 1–21. National Health Statistics Reports. National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig LaTasha B., Peck Jennifer D., Janitz Amanda E. 2019. “The prevalence of infertility in American Indian/Alaska Natives and other racial/ethnic groups: National Survey of Family Growth.” Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 33(2): 119–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Looze Margaretha, Harakeh Zeena, van Dorsselaer Saskia AFM, Raaijmakers Quinten AW, Vollebergh Wilma AM, ter Bogt Tom FM. 2012. “Explaining educational differences in adolescent substance use and early sexual debut: the role of parents and peers.” Journal of adolescence 35(4): 1035–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieke Ada C., Zhang Yujia, Kissin Dmitry M., Barfield Wanda D., Boulet Sheree L. 2017. “Disparities in Assisted Reproductive Technology Utilization by Race and Ethnicity, United States, 2014: A Commentary.” Journal of Women’s Health 26(6): 605–08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn, Kefalas Maria. 2011. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhaut Mieke CW. 2020. “Intersecting inequalities: education, race/ethnicity, and sterilization.” Journal of Family Issues 41(10): 1905–29 [Google Scholar]

- Ely Danielle M, Driscoll Anne K. 2021. “Infant Mortality in the United States, 2019: Data From the Period Linked Birth/Infant Death File.” Pp. 1–18. National Vital Statistics Reports, Volume 70. National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa Lorelle L., Jonathan M. Turk, Morgan Taylor. 2019. “Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report.” American Council on Education One Dupont Circle NW; Washington, DC: 20036. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano Cynthia, Robnett Belinda, Komaie Golnaz. 2009. “Gendered racial exclusion among white internet daters.” Social Science Research 38(1): 39–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer Lawrence B, Henshaw Stanley K. 2006. “Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001.” Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health 38(2): 90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank Reanne, Heuveline Patrick. 2005. “A crossover in Mexican and Mexican-American fertility rates: Evidence and explanations for an emerging paradox.” Demographic Research 12(4): 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaydosh Lauren, Schorpp Kristen M., Chen Edith, Miller Gregory E., Harris Kathleen Mullan. 2018. “College completion predicts lower depression but higher metabolic syndrome among disadvantaged minorities in young adulthood.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(1): 109–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez Martha E. 1989. “Latino/“Hispanic”—Who Needs a Name? The Case against a Standardized Terminology.” International Journal of Health Services 19(3): 557–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould Elise. 2020. “State of Working America Wages 2019: A story of slow, uneven, and unequal wage growth over the last 40 years.” Economic Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Greil Arthur L., McQuillan Julia, Shreffler Karina M., Johnson Katherine M., Slauson-Blevins Kathleen S. 2011. “Race-Ethnicity and Medical Services for Infertility: Stratified Reproduction in a Population-based Sample of U.S. Women.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52(4): 493–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman Eric Anthony. 2017. “Sexual health and multiple forms of discrimination among heterosexual youth.” Social Problems 64(1): 156–75 [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo Karen Benjamin, Hayford Sarah R. 2020. “Pathways to Parenthood in Social and Family Contexts: Decade in Review, 2020.” Journal of Marriage and Family 82(1): 117–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harknett Kristen, McLanahan Sara S. 2004. “Racial and Ethnic Differences in Marriage after the Birth of a Child.” American Sociological Review 69(6): 790–811 [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett Caroline Sten. 2014. “White-Hispanic differences in meeting lifetime fertility intentions in the U.S.” Demographic Research 30(43): 1245–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett Caroline Sten, Parrado Emilio A. 2012. “Hispanic familism reconsidered: Ethnic differences in the perceived value of children and fertility intentions.” The Sociological Quarterly 53(4): 636–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayford Sarah R., Guzzo Karen Benjamin. 2016. “Fifty Years of Unintended Births: Education Gradients in Unintended Fertility in the US, 1960–2013.” Population and Development Review 42(2): 313–41 [Google Scholar]

- Hayford Sarah R., Kissling Alexandra, Guzzo Karen Benjamin. 2020. “Changing Educational Differentials in Female Sterilization.” Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health 52(2): 117–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman James J, Walker James R. 1990. “The relationship between wages and income and the timing and spacing of births: Evidence from Swedish longitudinal data.” Econometrica: journal of the Econometric Society 58(6): 1411–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendi Arun S. 2019. “Proximate Sources of Change in Trajectories of First Marriage in the United States, 1960–2010.” Demography 56(3): 835–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo-Lopez Mark, Krogstad Jens, Passel Jeffrey S. 2021. “Who is Hispanic?”. FacTank: News in the Numbers. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer Robert A., Hamilton Erin R. 2010. “Race and Ethnicity in Fragile Families.” The Future of Children 20(2): 113–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Nan E. 1979. “Minority-Group Status and the Fertility of Black Americans, 1970: A New Look.” American Journal of Sociology 84(6): 1386–400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh Megan L., Jerman Jenna. 2018. “Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014.” Contraception 97(1): 14–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Sheela, Bumpass Larry L. 2008. “Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States.” Demographic Research 19(47): 1663–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer Renee D, Higgins Jenny A, Godecker Amy L, Ehrenthal Deborah B. 2018. “Racial and ethnic differences in patterns of long-acting reversible contraceptive use in the United States, 2011–2015.” Contraception 97(5): 399–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Øystein. 2007. “Effects of current education on second-and third-birth rates among Norwegian women and men born in 1964: Substantive interpretations and methodological issues.” Demographic Research 17(9): 211–46 [Google Scholar]

- Kuo Janet Chen-Lan, Raley R. Kelly. 2016. “Diverging Patterns of Union Transition Among Cohabitors by Race/Ethnicity and Education: Trends and Marital Intentions in the United States.” Demography 53(4): 921–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki Yasamin, Barber Jennifer S., Ela Elizabeth J., Bucek Amelia. 2016. “Black-White Differences in Sex and Contraceptive Use Among Young Women.” Demography 53(5): 1399–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale Nancy S., Oropesa RS. 2007. “Hispanic Families: Stability and Change.” Annual Review of Sociology 33(1): 381–405 [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe Ron. 2014. “The second demographic transition: A concise overview of its development.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(51): 18112–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Kevin. 2013. “The limits of racial prejudice.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(47): 18814–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T., Anderson Robert N., Hayward Mark D. 1995. “Marriage Markets and Marital Choice.” Journal of Family Issues 16(4): 412–31 [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T., Johnson Kenneth M., Turner Richard N., Churilla Allison. 2012. “Hispanic Assimilation and Fertility in New U.S. Destinations.” International Migration Review 46(4): 767–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D. 2020. “Young Adulthood Relationships in an Era of Uncertainty: A Case for Cohabitation.” Demography 57(3): 799–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy, Stykes B. 2015. “Twenty-five years of change in cohabitation in the US 1987–2013.” National Center for Marriage Research. [Google Scholar]

- Maralani Vida. 2013. “The Demography of Social Mobility: Black-White Differences in the Process of Educational Reproduction.” American Journal of Sociology 118(6): 1509–58 [Google Scholar]

- Margolis Rachel, Myrskylä Mikko. 2015. “Parental well-being surrounding first birth as a determinant of further parity progression.” Demography 52(4): 1147–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara. 2004. “Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition.” Demography 41(4): 607–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min Stella, Taylor Miles G. 2018. “Racial and Ethnic Variation in the Relationship Between Student Loan Debt and the Transition to First Birth.” Demography 55(1): 165–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. 2007. “Life course trajectories of perceived control and their relationship to education.” American Journal of Sociology 112(5): 1339–82 [Google Scholar]

- Morello-Frosch Rachel, Shenassa Edmond, D. 2006. “The Environmental “Riskscape” and Social Inequality: Implications for Explaining Maternal and Child Health Disparities.” Environmental Health Perspectives 114(8): 1150–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick Kelly, England Paula, Edgington Sarah, Kangas Nicole. 2009. “Education Differences in Intended and Unintended Fertility.” Social forces 88(2): 543–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Bustamante Luis. 2019. “Key facts about U.S. Hispanics and their diverse heritage.”. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne Cynthia, Manning Wendy D., Smock Pamela J. 2007. “Married and Cohabiting Parents’ Relationship Stability: A Focus on Race and Ethnicity.” Journal of Marriage and Family 69(5): 1345–66 [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio A., Flippen Chenoa A. 2012. “Hispanic Fertility, Immigration, and Race in the Twenty-First Century.” Race and Social Problems 4(1): 18–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio A., Morgan S. Philip. 2008. “Intergenerational Fertility Among Hispanic Women: New Evidence of Immigrant Assimilation.” Demography 45(3): 651–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelli-Harris Brienna, Lyons-Amos Mark. 2016. “Partnership patterns in the United States and across Europe: The role of education and country context.” Social forces 95(1): 251–82 [Google Scholar]

- Petersen Emily E, Davis Nicole L, Goodman David, Cox Shanna, Syverson Carla, Seed Kristi, Shapiro-Mendoza Carrie, Callaghan William M, Barfield Wanda. 2019. “Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths—United States, 2007–2016.” Pp. 762–65. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Volume 68. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]