Abstract

Wound healing is a complex process in tissue regeneration through which the body responds to the dissipated cells as a result of any kind of severe injury. Diabetic and non‐healing wounds are considered an unmet clinical need. Currently, different strategic approaches are widely used in the treatment of acute and chronic wounds which include, but are not limited to, tissue transplantation, cell therapy and wound dressings, and the use of an instrument. A large number of literatures have been published on this topic; however, the most effective clinical treatment remains a challenge. The wound dressing involves the use of a scaffold, usually using biomaterials for the delivery of medication, autologous stem cells, or growth factors from the blood. Antibacterial and anti‐inflammatory drugs are also used to stop the infection as well as accelerate wound healing. With an increase in the ageing population leading to diabetes and associated cutaneous wounds, there is a great need to improve the current treatment strategies. This research critically reviews the current advancement in the therapeutic and clinical approaches for wound healing and tissue regeneration. The results of recent clinical trials suggest that the use of modern dressings and skin substitutes is the easiest, most accessible, and most cost‐effective way to treat chronic wounds with advances in materials science such as graphene as 3D scaffold and biomolecules hold significant promise. The annual market value for successful wound treatment exceeds over $50 billion US dollars, and this will encourage industries as well as academics to investigate the application of emerging smart materials for modern dressings and skin substitutes for wound therapy.

Keywords: cells therapy, platelet therapy, skin tissue engineering, wound dressing, wound healing

1. INTRODUCTION

The skin protects us against the external environment and microbial invasion. Any damage to the skin leads to the entry of microorganisms into the body and may lead to infection. 1 Loss of body fluids, electrolytes, and nutrients occurs with severe skin damage which can be life‐threatening. 2 Wounds are caused by damage and any kind of disturbance in the structure and function of the healthy skin, which can often be as a result of mechanical trauma and injury, diabetes, burns and heat damages, genetic disorders or surgeries. 3 , 4

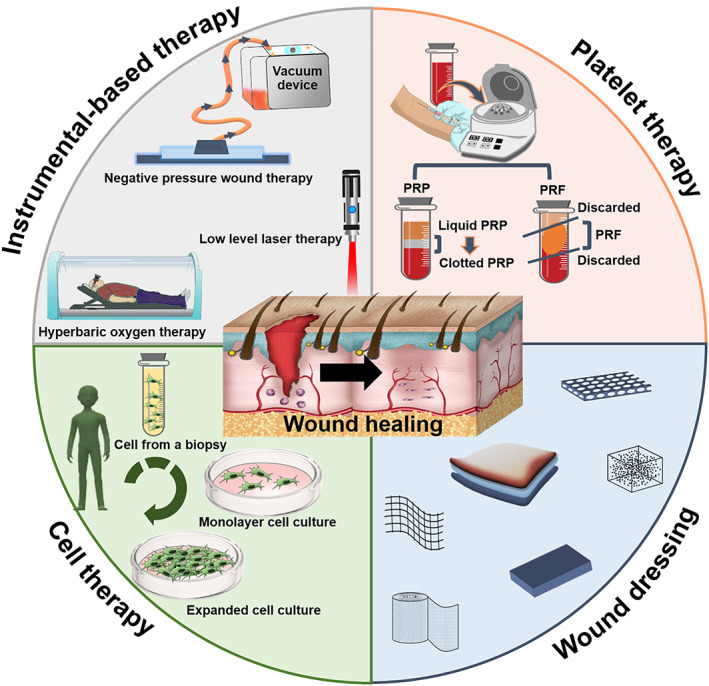

There are different types of wounds, and the treatment approaches are different, depending on the hospital, clinician, and healthcare staff (Figure 1). The majority type of wound treatment is based on wound dressing. Recently, modern wound dressings are on the rise, and often designed in various types to offer different features. Also, due to problems such as heterogeneity of existing products, high cost and lack of standard protocols, their clinical applications are limited or not effective. Here, the results of clinical trials are assessed, highlighting promising outcomes that show substantial translation from bench to bedside.

FIGURE 1.

Methodologies used for wound healing

Wound management costs include supplies and dressings (15%‐20%), nursing time (30%‐35%), and hospitalisation (more than 50%). 5 , 6 , 7 Frequent dressing changes increase the cost of wound care. Therefore, use of dressings that reduce the need for cleansing and debridement of wounds and are clinically more effective, are of a priority. The aim of this research was to critically review the current advancement in the therapeutic and clinical approaches for wound healing and tissue regeneration. The aim of this research was to critically review the current advancement in the therapeutic and clinical approaches for wound healing and tissue regeneration and to provide education and clinical guidance.

2. WOUND HEALING PROCESS

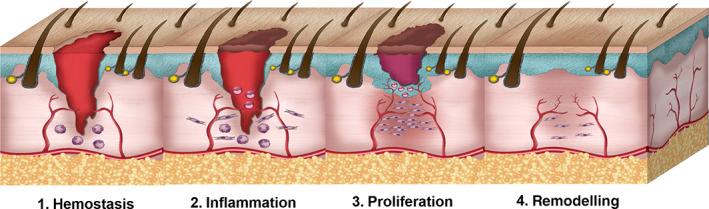

In the wound healing process, the cells, growth factors, and cytokines interact with each other to close the lesion. In fact, this process consists of four stages that are briefly explained. The first stage is haemostasis, in which the coagulation cascade is activated, and blood loss is prevented by the formation of a fibrin clot. The second stage is the inflammation phase which begins once the injury occurs, and it may last up to 6 days. The onset of the inflammatory phase occurs with the secretion of proteolytic enzymes and pro‐inflammatory cytokines from the immune cells at the wound site. Inflammatory cells produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) which are at higher levels in chronic wounds and burns. ROS prevents the penetration of microorganisms and bacteria. Also in the inflammatory phase, foreign particles and tissue debris are removed by macrophages and neutrophils. The next phase is proliferation, which begins 4 days after the injury and may last up to 14 days. In this phase, re‐epithelialization and granulation tissue formation occur and finally, the extracellular matrix (ECM) is formed. The last stage of wound healing is the remodelling (maturation) phase, in which type III collagen is replaced by type I, and the tensile strength of the newly formed tissue increases by changing the composition of the ECM. 8 Figure 2 schematically illustrates the wound healing process.

FIGURE 2.

Four stages of wound healing process

3. WOUND TREATMENT METHODS

Wound healing is a complex and multifactorial physiological process. Based on the type of the wound, various treatment methods and modalities, with a wide range of costs, have been provided, including swabbing for infection, cleaning the wound bed from the tissue debris, transplantation, cell therapy, applying wound dressing, and instrumental methods. This shows that none of the methods used for the treatment of the wound is ideal and 100% effective and therefore it is still considered an unmet clinical need. In this research, we critically reviewed the wound dressing and the emerging technology including regenerative medicine for wound healing. We also highlight in brief other techniques.

3.1. Transplantation of skin or stem cells/cells

This strategy is based on the transplantation of either skin or cells or stem cells and its derivatives to regenerate tissue. Skin transplantation is primarily used for patients with large burns and others for the wound.

3.1.1. Skin transplantation

Epithelial repair in deep skin wounds slowly heals due to the keratinocyte deficiency, hence in a matter of urgency autograft, allograft or xenograft transplantation is recommended for tissue regeneration, replacement, or repair. 9 Autograft has been suggested as the standard treatment for severe burns including premature wound debridement and incisions. 2 However, in extensive burns, it is not possible to use autografts due to insufficient access and scars that may remain due to the lack of dermis. 10 Through this procedure, a thin layer of skin, which includes the entire epidermis and part of the dermis (split‐thickness graft), is separated from the donor area by a dermatome and placed at the wound site. Wound treatment by autograft depends on the thickness of the dermis; the thicker the dermis, the faster the wound heals and the less formation of scar. While this transplant is taken from the patient's own tissue, there is no risk of rejection. 2 However, if autograft is limited or unavailable, allograft transplantation is considered where the tissue is separated from a donor and transplanted to the recipient person.

Transplantation from healthy tissue of donors (living person or cadavers) is known as an allograft. Allograft is being used clinically since World War II. Cadavers are usually used as allograft sources. For this purpose, cadavers are stored frozen in skin banks and used as tissue donors when needed. 11 The use of cadaver's skin is widely used in burn wound management in many burn centres around the world. In addition, skin grafts can be obtained from live donors. The main drawback of allograft transplantation is that this replacement is temporary due to the possibility of immunogenic rejection by the host's immune system and viral transmission.

Occasionally, xenografts are used as temporary biological wound dressings due to the scarcity or unavailability of sufficient Autograft and Allograft tissues. 12 In fact, Xenograft exposes exogenous collagen to the wounds, therefore helping to regenerate the skin and can be especially suitable for surgical wounds. 13 Bovine or porcine xenografts are now available for use in large sizes. However, in addition to possible rejection and the immune response, there is a risk of cross‐contamination with bovine spongiform encephalopathy or porcine endogenous retroviruses. There is no solution available for proper xenograft screening to detect the presence of these viruses, and they may even be a cellularized xenograft. Some recent studies have reported that the implantation of skin xenografts in mice does not cause inflammation, while an increase in macrophages and induced regenerative phenotypes was evident. 14 , 15 Despite significant advances in skin harvest and transplantation, the outcome would not always be successful. It is depended on the angiogenesis of the newly transplanted tissue and cell infiltration and if this does not occur, the transplant will eventually fail.

In general, skin substitutes should be biosafe, bifunctional, clinically effective, easy to use, and cost‐effective. Skin substitutes are divided into temporary and permanent according to the duration used. It is not possible to use an Autograft alone for large and deep burns, so surgeons often choose artificial skin substitutes which can prevent death and, depending on its function, also affect the appearance of the skin. Even in successful regenerations cases, often the dermis and the epidermis, the sweat glands and hair follicles are not completely repaired, which causes the patient's body to not have complete control of temperature or humidity. In this case, regular use of protective cream is recommended. Table 1 lists the commercially available permanent and temporary skin substitutes with their corresponding characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Commercial skin substitutes and their characteristics

| Skin substitute | Structure/composition | Description | Duration of use | Wound type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biobrane | Bi‐layer structure; a layer of nylon mesh covered by a thin membrane of silicon | Nylon fibres are coated with collagen ‐derived peptides to increase adhesion to the wound bed. The silicone surface is semi‐permeable and prevents fluid loss and microbial attacks. | Temporary | Deep burns |

| Transcyte | Bi layer, a nylon layer covered with collagen containing allogenic fibroblasts | Fibroblasts accelerate the healing process by producing ECM and release of growth factors. | Temporary | Minor burns |

| Apligraf | Bi‐layer bio‐hybrid collagen gel in which allogenic fibroblast cells are cultured and coated with a layer of allogenic keratinocytes | The underlying layer produces ECM proteins. The upper layer is composed of keratinocytes that proliferate and differentiate and reproduce the structure of the epidermis. | Permanent | Chronic wounds; diabetic foot ulcers, vascular ulcers |

| Dermagraft | A Poly (lactide‐co‐glycolide) scaffold on which allogenic fibroblasts are sprayed. | This product accelerates the epithelialization process of wound edges. | Permanent | Severe skin injuries |

| Alloderm | Separated cadaver skin | After transplantation, it is replaced by host fibroblasts and eventually integrated with the healthy skin. | Permanent | Deep wounds and burns |

| Integra | A matrix made from bovine type I collagen by cross‐linked chondroitin‐6‐sulphate, the other side of which is coated with silicon | As skin cells migrate into the matrix, the collagen is slowly absorbed and replaced with collagen produced from the person's own cells. | Permanent | Burns |

3.1.2. Stem cell or cell therapy

In wounds such as burns, removal of necrotic tissue and closure of the wound bed in the shortest possible time is necessary. As a matter of urgency, the burned area must be removed and replaced by other parts of the patient's skin. However, this is not possible due to the lack of healthy skin in large burns. To solve this problem, part of the patient's own skin is isolated, epidermis cells from the skin are a culture for several weeks and then placed on the patient's damaged skin. The method is mainly carried out in teaching hospitals and not routine, due to the cost and expertise required for cells proliferation as well as the risk of infection. This procedure is very expensive ($ 800 per 50 cm2). Hence, this method is recommended for patients with severe burns, who do not have enough autologous viable skin.

Other available approach is the use of “minced micrograft” on the damaged area. In this method, a small area of about 2 cm2 of healthy skin (epidermis and dermis) is obtained from the patient and is then cut into small pieces, mixed with a hydrogel, and applied to the wound area. This is a low cost and simple method which has the ability to emulate the skin geometry. 16 , 17 Also, the skin graft meshing technique is another treatment method. In this method, a small part of the skin is isolated using a dermatome and placed on the wound area after preparation. The meshed grafts are usually extended up to four times their original size. The lower the extent of the meshed graft, the higher its cell density, and the more likely it is to succeed. Also, the larger the damaged area, the longer it will take for the wound closure, which increases the risk of scarring. 18 , 19

The development and clinical use of in vitro cultured autogenous keratinocytes or bioengineered skin substitutes are recent advances in wound management. Nowadays, surgeons use autologous keratinocyte sheet for repair, which has a wide range of repair capabilities, but there remains the challenge with the easy separation of the epidermis layer from the dermis, which may cause blistering on the repair surface and eventually disrupts the healing process.

Recent researches in clinical applications include the transfer of healthy cells in suspension form or the transfer of cells cultured on the matrix to the wound bed. 20 With this method, there is no problem of separating the epidermis from the dermis, and therefore, the cell adhesion on the repair area is guaranteed. The repair time is shorter than the use of keratinocyte sheets. This in turn reduces the risk of infection as well as the cost of treatment.

Stem cells (SCs) are a recent approach in wound treatment. SCs are self‐renewal cells extracted from embryonic or adult tissue. SCs with unlimited capacity for self‐renewal, longevity, and maintenance of homeostasis play an effective role in the wound healing process. SCs have been widely used in the healing process of burn wounds, diabetic wounds, and bedsores. 21 Epidermal SCs is a widely used cell source in wound treatment and can be obtained from the hair follicle, isthmus, infundibulum, and interfollicular epidermis. However, it is unclear how SCs balance proliferation, differentiation, and migration during wound healing, and whether this dynamic process of regeneration continues or not, and it is not clear what the cell proliferation rate will be as the process progresses. Previous reports confirm that the skin epidermis repair does not cause a change in the cellular hierarchy of SCs and progenitors, or alter the balance in renewal and differentiation time. 22 Therefore, SCs are generally introduced with features such as an unlimited capacity for self‐renewal, long life, participation in tissue repair and maintaining body haemostasis. Based on these characteristics, SCs can play an effective role in wound healing. 23 The topical use of SCs to accelerate wound healing has been studied clinically by various researchers in recent years. Bone marrow SCs are known to accelerate the healing process in a variety of wounds, including burns, diabetic wounds, and bed sores. In addition to the significant benefits of this method for wound healing, there are some drawbacks: 1) the ideal mechanism for the release and delivery of SCs is unknown, 2) the amount of SCs required for wound healing is also not standardised, 3) proper culture, expansion, and characterisation of SCs also take 3 weeks to 1 month in the laboratory, leading to a significant delay in the healing of large wounds. Focusing on rapid cell proliferation in vitro, maximising the number of resident progenitor cells in the wound bed, effective release, and optimal grafting are among the goals of promoting the use of SCs in wound healing in the future. Since 2010, significant attention is being given to the utilisation of adult SC‐based therapy, including adipose mesenchymal SC for chronic skin lesions. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 Adipose mesenchymal stem cells are prepared by centrifugation, filtration, and fragmentation, with limitations such as difficulty in expanding sufficient cells for human use, good manufacturing practices, and the survival of expanded cells. 28 Due to these limitations, the clinical use of adipose mesenchymal stem cells has not received sufficient attention.

3.1.3. Platelet therapy

Platelets are blood components that originate in bone marrow megakaryocytes. These cells play an important role in primary haemostasis, thrombosis, inflammation, and wound healing. Platelets have secretory organelles such as alpha granules, which can secrete cytokines, growth factors, and ECM modulators. These factors can cause revascularization of damaged tissue, proliferation, and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into specific tissue cell types, as well as stimulation of migration, proliferation, and activation of fibroblasts, and connective tissue repair, thereby accelerating wound healing. In addition to the above, platelets play a protective role against microbes by secreting chemokines and cytokines (which activate immune cells) as well as microbicide proteins including kinocidins. 29 , 30

A different perspective to wound treatment is the utilisation of platelet therapy. Plasma constitutes a great percentage of the blood, in which platelets can be found. Platelets play a special role in blood coagulation and contain growth factors that regulate homeostasis, fibrin clot formation, and tissue repair. 31 , 32

The prepared platelet concentrates stimulate the regeneration process depending on the platelets number and density, the type of leukocytes trapped in the fibrin mesh, and the release of active molecules at the sites of injury. 33 Platelet concentrates are prepared by centrifugation of blood, which depending on the preparation protocol can be first generation concentrates such as platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) and platelet‐poor plasma (PPP) or second generation such as platelet‐rich fibrin (PRF), leukocyte‐platelet‐rich fibrin (L‐PRF) and advanced platelet‐rich fibrin (A‐PRF). 34

PRP is a concentrated blood plasma that contains large amounts of platelets as well as growth factors. 35 In PRP, the concentration of platelet is higher than the normal state of the blood, and generally the concentration of platelets and growth factors in platelet therapy is 10 times higher than usual. In platelet therapy, higher concentrations of growth factors cause acceleration of wound healing. PRP is usually obtained autologously from the patient's blood, therefore its use is low risk, and has been clinically applied to heal chronic and acute wounds. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 Protein substances such as cytokines and growth factors present in PRP can improve the healing of diabetic foot ulcers, 40 pilonidal sinus, maxillofacial surgeries, 41 plastic surgeries, discogenic low back pain 42 and skin and soft tissue lesions. In general, PRP stimulates endothelial, epithelial, and epidermal regeneration, as well as angiogenesis, collagen synthesis, and tissue repair. 43 Production of different types of growth factors begins with the degradation of platelet α granules in PRP, and it accelerates wound healing. PRP contains seven different types of growth factors including platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGFa and PDGFb), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor beta (TGF‐β), insulin‐like growth factor (IGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). 44 The wound healing process is highly dependent upon angiogenesis. VEGF, which is widely found in PRP, is considered one of the most effective growth factors for angiogenesis and is also responsible for the production of factors such as matrix metalloproteinases. The role of PRP in wound healing is very important especially in the homeostasis stage. Specific platelet components include anti‐inflammatory and pro‐inflammatory cytokines that may be responsible in part for activating wound repair. 45

PRP is a multi‐antibacterial component that prevents wound infection. 36 , 46 Several studies have shown that PRP has antibacterial activity against Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), 47 but it has no effect on some bacteria, including Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumonia), Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) and Pseudomonas eruginosa (P. aeruginosa). Another application of PRP is in the treatment of Epidermolysis bullosa ulcers. Due to the lack of a certain cure for Epidermolysis bullosa ulcers, advanced wound dressings based on silicone foam are usually recommended, but their scarcity in developing countries has led to overuse of paraffin gas, which is not efficient enough. Recent studies have shown that the use of autologous PRP can be effective in the healing of Epidermolysis bullosa ulcers. 48 Also, the treatment of cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis is another application of PRP in the form of PRP gel which has been shown to accelerate the wound closure and granulation tissue formation. In general, using PRP can be a safe and cost‐effective method for different wound healings and it can reduce the duration of treatment. 49

The use of platelet‐rich concentrates (PRC) has also been considered in various medical fields in the last two decades due to its regenerative properties. PRF is actually the second generation of PRCs that is prepared simply by centrifugation of blood in tube. 50

PRF can be used as an autologous biological additive with long‐term growth factor release. PRF is made up of platelets surrounded by strong fibrin filaments. It contains more than 75% platelets. Platelets trapped in PRF could repair wounds by releasing growth factors. 33 Various growth factors such as PDGF, IGF, TGF‐β, and VEGF can be released from PRF, which are very effective in angiogenesis and accelerate the wound healing process. 51 , 52 , 53 PRF also contains optimal amounts of thrombin, which promotes the migration of endothelial cells and fibroblasts and enhances angiogenesis. It has a unique fibrin structure that traps blood SCs and also can facilitate cell adhesion and spreading. 54 In general, low cost, non‐stimulation of the immune response, acceleration of tissue repair and simple and one‐step preparation are some of the advantages of using PRF. 55 Direct injection of growth factors in the desired location in the body leads to destruction and unstable diffusion of them and their use has more limitations than the use of PRF. This means that PRF offers a more sustainable release of growth factors. For this reason, the use of PRF for the treatment of chronic wounds such as diabetic foot ulcers and eye lesions has yielded promising results. 50 , 56 , 57

PRP is rich in growth factors and leads to accelerating the wound healing process. However, it has been observed that PRF is more effective in healing than PRP. PRF can also have a longer release of growth factors than PRP. 51 The polyvinyl alcohol scaffold containing PRF by freeze‐drying and stated that the release of VEGF and PDGF growth factors from the prepared wound dressing reduced the wound healing to 11 days in a mouse model. 58 The use of A‐PRF is more recommended due to the development of all biological properties required for wound healing, including the release of high concentrations of growth factors and vessels formation capability. 59

Many centres around the world, especially private clinics, used blood products such as PRP and PRF for wound treatment. This is easily obtained from patient blood and could consider the extraction of PRP as non‐invasive. However, will it work, this is a question. There are several clinical trials, but none are multicentre and non‐conclusive. The mechanism of these products on wound healing is not fully understood. In some cases, the patients may be suffering from bleeding disorders or hematologic diseases and so would not qualify for this in‐office procedure.

4. WOUND DRESSINGS

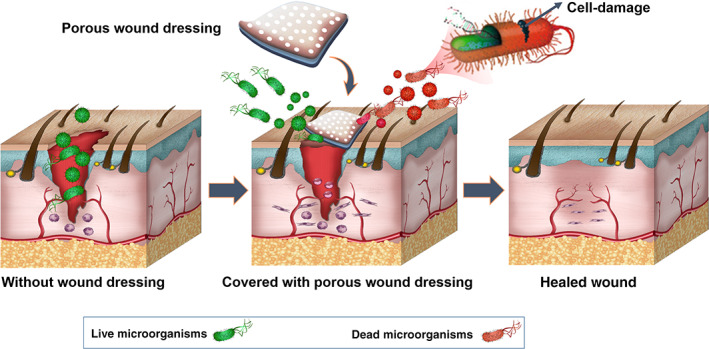

The most common method of wound treatment is to apply different types of wound dressing according to the type, depth, location, and size of the wound. In general, wound dressing is a physical barrier between the wound and the external environment which can protect the wound from further damage and against microorganisms, and ultimately accelerate wound healing. 60 The presence of microorganisms, and their entry into the wound, leads to delay and disruption in the wound healing process. Therefore, one of the important features of an ideal wound dressing is its antibacterial properties to prevent wound infection and the formation of bacterial biofilm. The presence of an antibacterial wound dressing at the site of an injury can prevent bacteria and microorganisms' penetration and, hence, enable natural healing process (Figure 3). Table 2 highlight the ideal properties of wound dressing product. 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66

FIGURE 3.

Protection of wound against microorganisms by covering the wound by a porous wound dressing

TABLE 2.

Ideal properties of wound dressing product

| 1. Antibacterial/bacterial resistance properties. |

| 2. Accelerating collagen synthesis and re‐epithelialization. |

| 3. Promoting haemostasis. |

| 4. Relieving pain. |

| 5. Control of wound bed pH. |

| 6. Mechanical protection with sufficient flexibility. |

| 7. Proper adhesions to the wound surface and at the same time no adhesion to the granulation tissue when replacing and preventing secondary damage. |

| 8. Maintaining the wound moisture—a moist environment increases the activity of cells and enzymes and enhances the proliferation of granular tissue. |

| 9. Excess exudate absorption. |

| 10. Dissolve the necrotic tissue and fibrin. |

| 11. Permeability to water vapour and gases |

| 12. Biocompatible degradation products. |

| 13. Accelerating the healing process and formation of granular tissue |

Wound dressings are generally classified into three categories: 1‐ traditional, 2‐ passive and 3‐ modern wound dressings. Traditional wound dressings were applied in ancient times from the leaves of trees and plants, spider webs and honey, which were used to prevent bleeding and prevent any contact between the wound and the external environment. 67 Passive dressings (such as sterile gauze, cotton pads, and bandages) which can only cover the wound surface and absorbs exudates but may adhere to the newly grown granular tissue and cause pain when removed. However, despite the problems, due to the low cost and simple manufacturing process, they are the most widely used clinical dressings.

Modern wound dressings include foams, films, hydrocolloids, and hydrogels. These wound dressings can be based on highly biocompatible and biological materials such as collagen, or synthetic materials due to their greater durability and lower cost. 68 , 69 Furthermore, great attention has been given to wound dressing that contain cells and growth factors such as Apligraf (Organogenesis Inc., MA USA) produced from human neonatal keratinocytes and fibroblasts, 70 which is a two layers skin substitute and is the first engineered skin approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

4.1. Common materials for wound healing constructs

Both synthetic and natural polymers can be used to make suitable wound dressings. However, the biocompatibility and biodegradability combined with the high level of biomimicry and good physicochemical properties of natural biopolymers make them more attractive for wound dressings owed to their structural similarity to extracellular matrix (ECM). In biopolymer‐based wound dressings, the degree of degradation should be followed by the dynamics of the wound healing process, and physiological healing and, also, the release of active agents must be guaranteed. In addition, the mechanical properties of a suitable wound dressing should also be considered. These include, but are not limited to, tensile strength, elastic modulus, stiffness, stress stiffening effects, stress‐relaxation rate, and viscoelasticity. 71 Mechanical properties are among the most important and influential factors in wound dressing design that can affect scar formation and if the mechanical load transfer is carried out incorrectly, the growth of fibrous tissue are stimulated. 72 Tensile strength and flexibility are among the most important mechanical factors to be considered for wound dressing constructs. In order to avoid damage to the underlying tissues, a wound dressing should be flexible and have a low flexural modulus, as well as having as tensile properties as skin. 52 Various natural polymers have been used in the design of commercial wound dressings (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Some commercial biopolymer based wound dressings

| Polymer | Trademarks | Applications |

|---|---|---|

|

Chitin |

Chitipack P | Large skin defects and defects difficult to suture |

| Chitipack S | Surgical tissue defects and traumatic wounds | |

|

Chitosan |

Chitoflex | Severe bleeding |

| Chitopack C | Regeneration of normal subcutaneous tissue and regular skin | |

| Chitopoly | Prevent dermatitis | |

| Chitoseal | Bleeding wounds | |

| Clo‐Sure | A pressure pad applied topically to wound healing acceleration | |

| HemCon | Bleeding control | |

| Tegasorb | leg ulcers, sacral wounds, chronic wounds. | |

| Syvek‐Patch | Bleeding control | |

|

Sodium Alginate |

Algicell | Diabetic foot ulcers, leg ulcers, pressure ulcers, donor sites, traumatic and surgical wounds |

| Guardix‐SG | Postoperative wounds | |

| Kaltostat | Pressure ulcers, venous ulcers, diabetic ulcers, donor sites and traumatic wounds | |

| Tegagen | Diabetic and infected wounds | |

| Hyalogran | Diabetic wounds, pressure sores, ischemic and necrotic wounds | |

| Tromboguard | Bleeding control, traumatic wounds and skin graft donor sites | |

| Calcium Alginate | AlgiSite M | Leg ulcers, pressure ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers and surgical wounds |

| Algivon | Necrotic wounds and wounds with odours | |

| Comfell Plus | Venous leg ulcers, pressure ulcers, burns, donor sites, postoperative wounds and necrotic wounds | |

| Fibracol | Pressure ulcers, venous ulcers, diabetic ulcers and second‐degree burns | |

| Sorbsan | Arterial, venous, and diabetic leg ulcers, pressure ulcers, post‐operative wounds and donor site | |

| SeaSorb | Diabetic and leg pressure ulcers | |

| Fibrinogen | Evicel/NPS MedicineWise | Abrasions and superficial and partial‐thickness burns |

| Collagen I | Promogran/3M | Diabetic ulcers, venous ulcers and Pressure ulcers |

| Biopad/Ltd | Burns and wounds | |

| Biostep/GmbH | Pressure ulcers, diabetic ulcers, venous ulcers, donor sites, abrasions, traumatic wounds |

To date, most studies on wound healing have been performed in vitro. Some studies have been carried out on preclinical animal model evaluations, but clinical trials constitute a small part of the many studies on wound therapeutic approaches. During a general summary, some clinical studies of the different wound treatment methods are reported in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Summary of methodologies for wound treatment in clinical trials

| Method | Country | No. of patients | Clinical outcome | Type of wound | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental methodologies | NPWT | Germany, Belgium, & Netherlands | 507 | NPWT is an effective treatment option for subcutaneous abdominal wound healing impairment after surgery | Subcutaneous abdominal wound | 2020 73 |

| Germany | 10 | Patients who received NPWTi were found to have decreased time of hospitalisation and accelerated wound healing than patients who received NPWT | Lower limb acute traumatic and infected wound | 2016 74 | ||

| USA France, South Africa | 200 | Significantly fewer healing complications were noted in NPWT‐treated breasts | Bilateral reduction mammaplasty wound | 2018 75 | ||

| United States | 49 | Initial investigation shows that this could lead to a significant decrease in time to healing, without a significant increase in wound complications | Class III or Class IV surgical wound | 2018 76 | ||

| United States | 3 | NPWTi‐d could be a viable adjunctive tool for management of complex, infected wounds | Diabetic foot ulcer, dehisced abdominal wound, upper torso and axillary region wound | 2019 77 | ||

| HOT | Japan | 29 | The response to HOT was excellent in six patients, good in 8, fair in 11 and poor in 4. | Different chronic wound | 2014 78 | |

| Finland | 26 | Ulcer area and depth exhibited superior improvement in group A, which treated with HOT. | Ischaemic diabetic foot ulcer | 2018 79 | ||

| Netherlands | 3 | One patient had complete healing of her perineal wound; another patient showed initial improvement but had a flare of luminal and perineal disease at the 3‐month follow‐up, and the third one showed improvement solely in the questionnaires | Metastatic perineal Crohn's disease lesion | 2020 80 | ||

| LLLT | India | 68 | 34 ulcers treated with LLLT showed significant reduction in percentage wound area compared with control group | Chronic diabetic foot ulcer | 2012 81 | |

| France | 24 | LLLT had not early effects as an adjunctive therapy to wound healing of venous leg ulcers | Chronic venous leg ulcer | 2017 82 | ||

| India | 40 | LLLT‐applied sites had significantly improved wound healing compared with the controls on the postoperative 7th and 30th day | Scalpel gingivectomy wound | 2018 83 | ||

| Tissue/cells transplantation | Skin transplant | South Korea | 1282 | Patients with major burns who underwent cadaver skin allografting had a lower mortality rate than those who did not | Burn | 2018 84 |

| Brazil | 1 | Tilapia skin showed good adherence to the burned area and a lack of antigenicity and toxicity, promoting complete re‐epithelialization of the wound | Superficial partial thickness burn | 2019 85 | ||

| Canada | 15 | The use of either an approximation or overlapping technique of constructing a skin graft border at the margin of normal skin does not appear to affect the quality of the mature skin graft border scar in adult burn patients | Burn | 2019 86 | ||

| Iceland | 85 | The results showed that acute biopsy wounds treated with fish skin grafts heal faster than wounds treated with human amnion/chorion membrane allografts | Acute full thickness wound | 2020 87 | ||

| Burns treated with allograft healed within 2 weeks, whereas burns treated with silver took 3 weeks to heal | Partial thickness burn | 2020 88 | ||||

| Stem cells/cells | Iran | 10 | Fetal cell‐based skin substitutes were safe and they were well tolerated when applied to donor sites in burn patients | Donor sites wound in burn patients | 2019 89 | |

| United States | 5 | Autologous skin cell suspension was used successfully to achieve definitive closure of facial burns containing a confluent layer of dermis | Deep partial‐thickness facial burn | 2020 90 | ||

| Platelet therapy | Iran | 50 | Platelet dressing showed significant epithelialization and granulation tissue formation compared with silver sulfadiazine dressing | Burn wound | 2013 91 | |

| Czech Republic | 18 | Less pain and earlier discharge were observed in patients received split thickness skin graft with autologous platelet concentrate compared with institutional controls | Deep burn wound | 2014 92 | ||

| The Netherlands | 52 | The addition of PRP in the treatment of burn wounds did not result in improved graft take and epithelialization or better scar quality | Deep dermal burn | 2016 93 | ||

| Turkey | 36 | Epithelialization was higher in the test groups than the control group in 14 days | Palatal wound | 2020 94 | ||

| Wound dressing | Chitosan and collagen | Mexico | 68 | The use of Chitosan and isosorbide dinitrate spray increased the number of patients who achieved complete closure of the ulcer | Diabetic foot ulcer | 2018 95 |

| Malaysia | 244 | There was no significant difference in the mean epithelisation percentage between groups | Superficial and abrasion wound | 2018 96 | ||

| India | 30 | It was proved that PRF can be a good alternative to v membrane for grafting of the oral mucosal surgical defects | Oral mucosal lesion | 2018 97 | ||

| Iran | 10 | All patients showed either significant or complete improvement after 8 weeks of therapy and at 16 weeks post treatment all cases were completely cured | Lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis | 2019 98 | ||

| Taiwan | 33 | Col‐based composite dressings promoted better epithelialization and healing than antibiotic ointment treatment | Acute traumatic wound | 2019 99 | ||

| South Korea | 30 | Collagen group provided a more complete and faster treatment than control group | Diabetic foot ulcer | 2019 100 | ||

| Iran | 61 | Chitosan/Collagen hydrogel dressing used in this study led to acceleration of healing process | Diabetic foot ulcer | 2020 101 | ||

| India | 60 | Chitosan enhanced soft tissue healing, improved colour matching and minimised scarring, as compared with Collagen | Facial soft tissue abrasion | 2020 102 | ||

| Gelatin | Italy | 40 | The PRF treated group showed a significantly faster re‐epithelialization in comparison with gelatin sponge treated group | Palatal wound | 2016 103 | |

| Egypt | 36 | Alvogyl as a palatal dressing can be comparable with Gelatin sponge in terms of pain reduction, haemostasis and re‐epithelisation | Palatal wound | 2020 104 | ||

| Keratin | New Zealand | 26 | Keratin wound dressing significantly increased epithelialization rate in older patients | Partial thickness wound | 2013 105 | |

| New Zealand | 1404 | There were no significant differences between the groups on the primary outcome | Venous leg ulcer | 2020 106 |

The choice of treatment method is dependent upon the patient's wound type, severity, and medical condition. For example, burn patients, who are divided into grades 1, 2, and 3, have different treatment priorities, such as saving the patient from death or relieving pain. While the choice of treatment for cosmetic surgery is based on wound healing without scar tissue and for diabetics, treatment to prevent amputation is a priority. Therefore, considering the patient's condition is an important parameter in choosing the right treatment.

4.2. Nanomaterials

Today, nanomaterials are widely used due to their unique properties, including very large specific surface area and high surface energy. In general, nanomaterials can play an active role in haemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and antimicrobial inhibition in the wound healing process. 107 Metal nanoparticles such as silver, gold, zinc, etc. are among the materials that have long been used in wound dressings to prevent bacterial infections and accelerate wound healing. 108 Also, in many studies, the use of liposomes, 109 mesoporous silica, 110 and drug‐containing nanomaterials 111 , 112 have shown promising results. Recently, the use of carbon nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes, graphene, and graphene oxide (GO) with unique physicochemical properties in modern wound dressings have been investigated, which are briefly discussed below.

Notable carbon nanotubes (CNT) properties such as high electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and low density have expanded its application in the fabrication of tissue engineering scaffolds. 113 , 114 To date, CNT‐based nanomaterials have been studied for use in biomedicine, biosensors, drug delivery, tissue engineering, and wound healing applications. Functionalized CNT is known as one of the most popular nanocarriers due to its high specific surface area and it can be used for effective drug delivery. 115 In addition, CNT can kill or suppress bacteria. 116 CNT‐based dressings have been shown to increase fibroblast cells migration and proliferation and also have a significant effect on angiogenesis potential l. 117 , 118

4.2.1. Graphene and GO

Graphene with a two‐dimensional (2D) structure is another carbon allotropy that has been proposed as a new carbon nanomaterial in tissue engineering. Its special properties include high thermal and electrical conductivity, excellent mechanical strength, and biocompatibility. 119 , 120 , 121 GO is one of the graphene‐based materials that have less thermal and electrical conductivity than graphene due to the presence of oxygen groups and structural changes. The presence of carboxyl, hydroxyl and carbonyl groups on GO has made it possible to interact with different types of materials, including polymers. 119 Therefore, the tendency of many researchers in the field of bioengineering has shifted to using GO instead of graphene.

Generally, wound dressings containing graphene‐based nanomaterials are used for several basic reasons including antibacterial activity, increasing mechanical properties, wound moisture retention, biocompatibility and promoting cell proliferation, adhesion, differentiation and growth. 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 Also, graphene‐based nanomaterials alone or in combination with biopolymers have been used in various studies as a drug carrier. 125 , 126

5. INSTRUMENTAL METHOD

Below is a short summary of instrumental methodology used to treat wound.

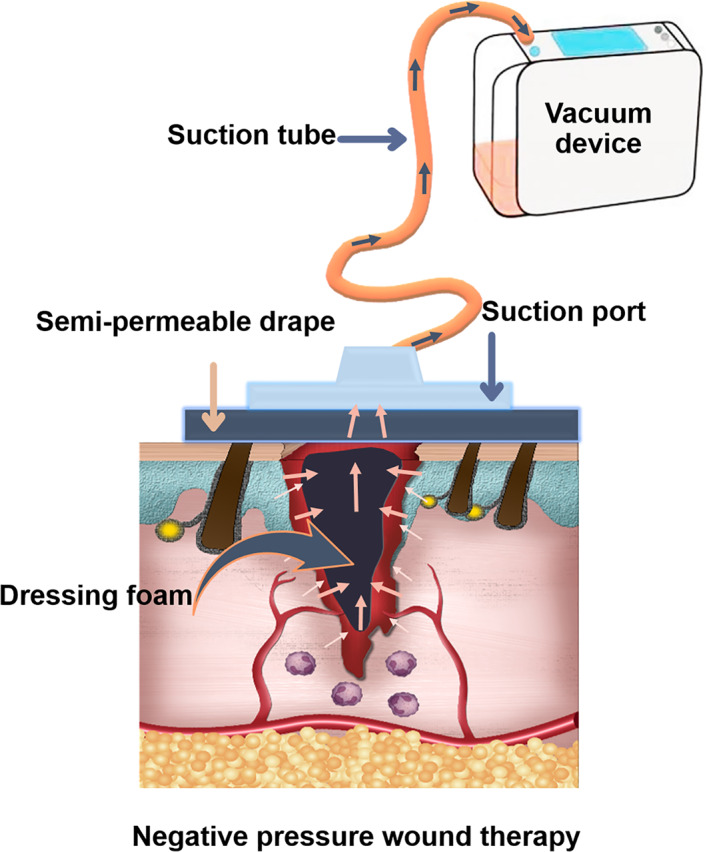

5.1. Negative pressure wound therapy

The negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) system consists of three main parts: a sponge, a semi occlusive barrier, and a fluid collection system that exerts uniform negative pressure on the wound surface. This method accelerates wound healing based on several mechanisms of action, including improving local blood flow, inducing macro deformation, inducing granulation, and angiogenesis, reducing oedema and reducing bacterial colonisation. 127 , 128

The NPWT controls the exudate by fluid removal and thus prevents infection and cross‐contamination (Figure 4). 129 This method also reduces edema, stimulates angiogenesis, helps to maintain wound moisture, and finally promotes contraction of the wound edges. This technique has been used for the treatment of acute and chronic wounds, open wounds, burns, diabetic wounds and also venous and arterial wounds. 130

FIGURE 4.

Schematic illustration of wound treatment by negative pressure wound therapy

Overall, although many patients have been treated with NPWT, this include our own institute (Royal Free Hospital, London), but there is no concrete evidence that NPWT is significantly better than conventional therapy. There were some clinical trials, but not conclusive, hence a multicentre well organised clinical trial needs to verify the effectiveness of the NPWT as instrument for wound healing.

5.2. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

The presence of oxygen plays a major role in the healing process of chronic wounds. The hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HOT) treatment technique is based on the administration of 100% pure oxygen in a completely closed chamber with a pressure of about three times the normal atmospheric pressure, which is a non‐invasive and relatively safe method. 131 Many desirable physiological changes have been reported in using HOT, such as enhancing angiogenesis, improving collagen deposition, activating leukocytes, and reducing edema. However, a large clinical study with 6259 patients carried out with hyperbaric oxygen (HBO), showed that the treatment did not improve the wound healing, nor prevented amputation. 132 Perren et al 79 used the HOT method to treat Ischaemic Foot Ulcers in Type 2 Diabetes. Based on their results, the HOT treatment improved the ulcer area and depth compared with the control group. Lansdorp et al 133 investigated the effect of HOT on perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease and significant clinical, radiological and biochemical improvement was observed in patients in the treatment group.

5.3. Low‐level laser therapy

Low‐level laser therapy (LLLT) is one of the phototherapeutic modalities and uses different gas components. Helium/neon, aluminium/gallium/indium/phosphide, gallium/aluminium/arsenide and also gallium/arsenide are the most common types of LLLTs that have different wavelengths to target different depths of the tissue. In addition to wavelength, power, pulse rate, pulse duration, interpulse interval, total irradiation time, intensity (power/area) and dose (power irradiation time/area irradiated) are among the important parameters in LLLT. The mechanism of action of this type of laser is through photothermal effects; however, LLLT usually does not cause noticeable temperature changes. 134 , 135

The exact mechanism of this method is not known, but it seems that the technique reduces wound inflammation by reducing the number of chemicals produced by the cells and reducing enzymes related to pain and inflammation. The influential factors in this method are the ideal wavelength, radiation dose, duration, and location of the treatment. Application LLLT has been reported that it is effective for acute, chronic, and postoperative wounds. 136 There are clinical trials carried out using LLLT for wound healing with a positive outcome, at the same time clinical paper has been emerging that the application of LLLT did not significantly improve the wound healing. 82

In summary, these three methodologies are interesting and with their application, some improvement in wound healing has been observed, however, none of them significantly improved the process of wound healing to replace the mode of the treatment. These methodologies have mainly been used in the university hospital and by clinical academics. It has not fully translated to general hospital clinical settings.

5.4. Cold atmospheric pressure plasma

Cold atmospheric pressure plasma (CAP) is one of the wound treatment methods based on inactivating microbial pathogens and stimulating tissue regeneration. Cold plasma is typically generated in special low‐pressure reactors (p < 133 mbar) through direct current, radiofrequency, microwave or pulsed discharge systems. 137 The mechanism through which the plasma affects wound healing is not fully understood. However, the sterilising properties of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species produced by cold plasma may be effective in accelerating wound healing. Reactive species are said to be involved in many cellular responses, such as cell differentiation and apoptosis, and act as second messengers for treated cells. Such cell–cell signalling events are involved in various stages of wound healing as well as accelerating re‐epithelialisation. 138 It has been shown that CAP increases the proliferation of fibroblasts and endothelial cells as well as the growth of epithelial cells and activates the integrin of fibroblasts and epithelial cells. It can be said that these effects are similar to the activity of nitric oxide and ROS during the wound healing process. 139 Today, the use of the CAP method in repairing many types of wounds such as diabetic foot ulcers, 140 , 141 herpes zoster, 142 psoriasis, 143 and warts 144 has been studied and acceleration of wound healing with this method has been confirmed based on clinical results.

6. FUTURE PROSPECT

Currently, treatment of wounds in general including diabetic wounds is considered an unmet clinical need. Hence billions of dollars around the globe have been spent to find a better treatment option. The various treatment approaches highlighted in this review, and some have shown promising outcomes, especially the bioactive wound dressing products. The instrumentation techniques are all interesting, but clinical trial showed not significant improvement, hence require further development. However, still many wound treatments considered as unmet clinical need and it require multidisciplinary approach for development of effective treatment. The results of recent clinical trials suggest that the use of modern dressings and skin substitutes is the easiest, most accessible, and cost‐effective approach for the treatment of chronic wounds. So, the ultimate hope in this regard would be to create a suitable wound dressing that is available off the shelf and in demand for the patients upon need. In addition to the above, new technologies such as personalization through 3D printing can lead to promising results in the future. There has been quantum leap in development of advanced materials for all kinds of industrial application including medical. Combination of new smart biomaterials, antibacterial drugs, and nanoparticles with possible stem cells/cells from patient extract in clinic such as blood products or adipose stem cells/cells with simple extraction in the clinic may be the solution to the wound treatment. Therefore, an interdisciplinary approach including clinician, scientist both materials and biological as well as engineering is needed to develop stem cell‐based therapies or drug delivery systems to provide more effective and safer treatment for chronic wounds in the near future.

7. CONCLUSION

The wound healing process is a complex sequence of events that begins with injury and leads to the formation of granular tissue and regeneration of skin and finally wound closure. Depending on the type of wound, treatment may take time and in the worst case no response to the treatment is observed and may result in amputation. As highlighted in the review, there are many treatment techniques, but none are 100% successful. Therefore, the treatment of the wound is still considered an unmet clinical need and academic as well as industries are searching for better techniques. Currently heavily under research are growth factors and cytokines released from platelets and leukocytes that have a significant effect on the cellular functions such as migration, differentiation, and proliferation, so they can regulate the wound healing process. Wound dressings, as the most accessible and cost‐effective cases for wound treatment, are designed depending on the type of wound and its location. An ideal wound dressing should be antibacterial, biocompatible, non‐toxic, stable, hydrophilic, and swollen. Better undemanding the process of wound healing combined with smart material as a scaffold, control release of the drug, growth factors and cells may bring hope for treatment of wound.

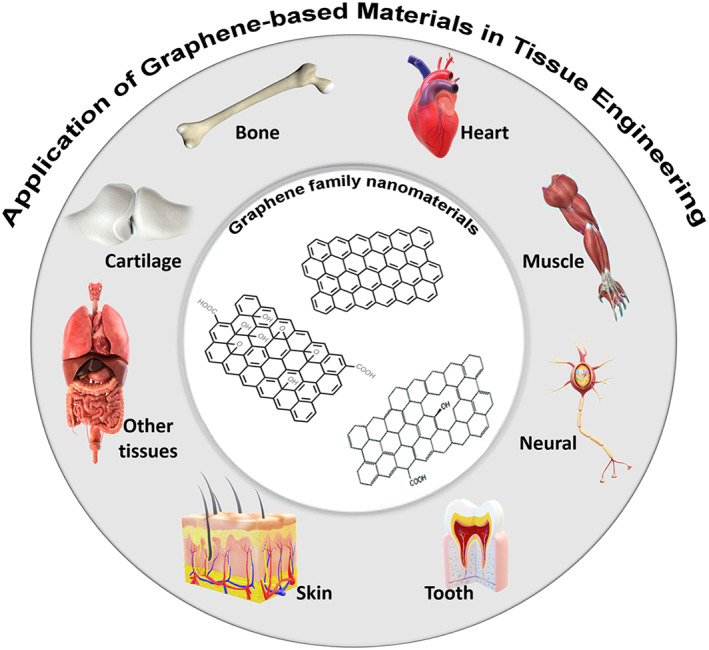

Here, we like to introduce a new material, graphene, it is one layer atom, it has high strength, elastic, and light weighted, antibacterial, electrically and thermally conductive, cheap, and make ideal scaffold for wound healing. It is emerging into surgical implants and medical devices (Figure 5). We strongly recommend researcher in wound healing to consider the material. We have been working on the use of the smart scaffold, using functionalized graphene‐based nanocomposite material trade named “BioHastalex.” 145 , 146 The scaffold has been built up layer by layer by electrospinning with different porosities using BioHastalex materials for control release of growth factors and at the same time elutes nitric oxide (NO). 147 , 148 Furthermore, using of adipose‐derived stem cells is investigated seeding the scaffold. Effective treatment of wounds is of huge interest to pharmaceutical and medical devices companies. Currently, there is a race for the development of effective treatment, as this is a multi‐billion‐dollar industry.

FIGURE 5.

Schematic illustrator of graphene oxide nanomaterials and their application in tissue engineering, particularly in nerve, muscle, heart, skin, cartilage, dental field, and other tissues

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Mirhaj M, Labbaf S, Tavakoli M, Seifalian AM. Emerging treatment strategies in wound care. Int Wound J. 2022;19(7):1934‐1954. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13786

Contributor Information

Sheyda Labbaf, Email: slabbaf85@gmail.com.

Alexander Marcus Seifalian, Email: a.seifalian@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhang M, Wang G, Wang D, et al. Ag@ MOF‐loaded chitosan nanoparticle and polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate/chitosan bilayer dressing for wound healing applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;175:481‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vig K, Chaudhari A, Tripathi S, et al. Advances in skin regeneration using tissue engineering. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(4):789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tottoli EM, Dorati R, Genta I, Chiesa E, Pisani S, Conti B. Skin wound healing process and new emerging technologies for skin wound care and regeneration. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(8):735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wan R, Weissman JP, Grundman K, Lang L, Grybowski DJ, Galiano RD. Diabetic wound healing: the impact of diabetes on myofibroblast activity and its potential therapeutic treatments. Wound Repair Regen. 2021;29(4):573‐581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tiscar‐González V, Menor‐Rodríguez MJ, Rabadán‐Sainz C, et al. Clinical and economic impact of wound care using a polyurethane foam multilayer dressing. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2021;34(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Percival SL, McCarty SM, Lipsky B. Biofilms and wounds: an overview of the evidence. Adv Wound Care. 2015;4(7):373‐381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weigelt MA, McNamara SA, Sanchez D, Hirt PA, Kirsner RS. Evidence‐based review of antibiofilm agents for wound care. Adv Wound Care. 2021;10(1):13‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moeini A, Pedram P, Makvandi P, Malinconico M, d'Ayala GG. Wound healing and antimicrobial effect of active secondary metabolites in chitosan‐based wound dressings: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;233:115839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dvir T, Timko BP, Kohane DS, Langer R. Nanotechnological Strategies for Engineering Complex Tissues. Nat Nanotechnol. 2021;6:13‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jeschke MG, van Baar ME, Choudhry MA, Chung KK, Gibran NS, Logsetty S. Burn injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):1‐25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Popa LG, Giurcaneanu C, Mihai MM, et al. The use of cadaveric skin allografts in the management of extensive wounds. Rom J Leg Med. 2021;29:37‐44. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rowan MP, Cancio LC, Elster EA, et al. Burn wound healing and treatment: review and advancements. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nathoo R, Howe N, Cohen G. Skin substitutes: an overview of the key players in wound management. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(10):44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sommerfeld SD, Cherry C, Schwab RM, et al. Interleukin‐36γ–producing macrophages drive IL‐17–mediated fibrosis. Sci Immunol. 2019;4(40):eaax4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henn D, Chen K, Maan ZN, et al. Cryopreserved human skin allografts promote angiogenesis and dermal regeneration in a murine model. Int Wound J. 2020;17(4):925‐936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cammarata E, Giorgione R, Esposto E, Mazzoletti V, Boggio P, Savoia P. Minced skin grafting: a minimally invasive and low‐cost procedure to treat Pyoderma gangrenosum. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2021;34(2):1‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyanaga T, Kishibe M, Yamashita M, Kaneko T, Kinoshita F, Shimada K. Minced skin grafting for promoting wound healing and improving donor‐site appearance after split‐thickness skin grafting: a prospective half‐side comparative trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(2):475‐483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Panayi AC, Haug V, Liu Q, et al. Novel application of autologous micrografts in a collagen‐glycosaminoglycan scaffold for diabetic wound healing. Biomed Mater. 2021;16(3):035032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zheng X, Li X, Chen T, et al. Effect of the orientation of microskin on the survival rate of transplantation and improving the method. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2021;14(2):186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhao H, Chen Y, Zhang C, Fu X. Autologous epidermal cell suspension: a promising treatment for chronic wounds. J Tissue Viability. 2016;25(1):50‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen L, Xu Y, Zhao J, et al. Conditioned medium from hypoxic bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells enhances wound healing in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e96161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aragona M, Dekoninck S, Rulands S, et al. Defining stem cell dynamics and migration during wound healing in mouse skin epidermis. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Otero‐Viñas M, Falanga V. Mesenchymal stem cells in chronic wounds: the spectrum from basic to advanced therapy. Adv Wound Care. 2016;5(4):149‐163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gentile P, Sterodimas A, Calabrese C, et al. Regenerative application of stromal vascular fraction cells enhanced fat graft maintenance: clinical assessment in face rejuvenation. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;20(12):1503‐1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gentile P, Sterodimas A, Pizzicannella J, et al. Systematic review: allogenic use of stromal vascular fraction (SVF) and decellularized extracellular matrices (ECM) as advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMP) in tissue regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(14):4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gentile P, Calabrese C, De Angelis B, Pizzicannella J, Kothari A, Garcovich S. Impact of the different preparation methods to obtain human adipose‐derived stromal vascular fraction cells (AD‐SVFs) and human adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD‐MSCs): enzymatic digestion versus mechanical centrifugation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gentile P, Garcovich S. Systematic review: adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells, platelet‐rich plasma and biomaterials as new regenerative strategies in chronic skin wounds and soft tissue defects. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gentile P, Kothari A, Casella D, Calabrese C. Fat graft enhanced with adipose‐derived stem cells in aesthetic breast augmentation: clinical, histological, and instrumental evaluation. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(9):962‐977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Etulain J. Platelets in wound healing and regenerative medicine. Platelets. 2018;29(6):556‐568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levoux J, Prola A, Lafuste P, et al. Platelets facilitate the wound‐healing capability of mesenchymal stem cells by mitochondrial transfer and metabolic reprogramming. Cell Metab. 2021;33(2):283‐299.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miron RJ, Zhang Y. Autologous liquid platelet rich fibrin: a novel drug delivery system. Acta Biomater. 2018;75:35‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Periayah MH, Halim AS, Saad AZM. Mechanism action of platelets and crucial blood coagulation pathways in hemostasis. Int J Hematol‐Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2017;11(4):319–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pavlovic V, Ciric M, Jovanovic V, Trandafilovic M, Stojanovic P. Platelet‐rich fibrin: basics of biological actions and protocol modifications. Open Med. 2021;16(1):446‐454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Caruana A, Savina D, Macedo JP, Soares SC. From platelet‐rich plasma to advanced platelet‐rich fibrin: biological achievements and clinical advances in modern surgery. Eur J Dentistry. 2019;13(02):280‐286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu H, Wang G, Zhang J, Hong Y, Zhang K, Cui H. Microspheres powder as potential clinical auxiliary materials for combining with platelet‐rich plasma to prepare cream gel towards wound treatment. Appl Mater Today. 2022;27(10140):1–15. 10.1016/j.apmt.2022.101408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou M, Lin F, Li W, Shi L, Li Y, Shan G. Development of nanosilver doped carboxymethyl chitosan‐polyamideamine alginate composite dressing for wound treatment. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;166:1335‐1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lei X, Yang Y, Shan G, Pan Y, Cheng B. Preparation of ADM/PRP freeze‐dried dressing and effect of mice full‐thickness skin defect model. Biomed Mater. 2019;14(3):035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mostafaei S, Norooznezhad F, Mohammadi S, Norooznezhad AH. Effectiveness of platelet‐rich plasma therapy in wound healing of pilonidal sinus surgery: a comprehensive systematic review and meta‐analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2017;25(6):1002‐1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Venter NG, Marques RG, Dos Santos JS, Monte‐Alto‐Costa A. Use of platelet‐rich plasma in deep second‐and third‐degree burns. Burns. 2016;42(4):807‐814. 10.1016/j.burns.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mohammadi MH, Molavi B, Mohammadi S, et al. Evaluation of wound healing in diabetic foot ulcer using platelet‐rich plasma gel: a single‐arm clinical trial. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017;56(2):160‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Albanese A, Licata ME, Polizzi B, Campisi G. Platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) in dental and oral surgery: from the wound healing to bone regeneration. Immun Ageing. 2013;10(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Monfett M, Harrison J, Boachie‐Adjei K, Lutz G. Intradiscal platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) injections for discogenic low back pain: an update. Int Orthop. 2016;40(6):1321‐1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Raposio E, Bertozzi N, Bonomini S, et al. Adipose‐derived stem cells added to platelet‐rich plasma for chronic skin ulcer therapy. Wounds. 2016;28(4):126‐131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Laidding SR, Josh F, Nur K, et al. The effect of combined platelet‐rich plasma and stromal vascular fraction compared with platelet‐rich plasma, stromal vascular fraction, and vaseline alone on healing of deep dermal burn wound injuries in the Wistar rat. Med Clín Práct. 2021;4:100239. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Norooznezhad AH, Norooznezhad F. How could cannabinoids be effective in multiple evanescent white dot syndrome? A hypothesis. J Rep Pharma Sci. 2016;5(1):41‐44. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kobayashi Y, Saita Y, Nishio H, et al. Leukocyte concentration and composition in platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) influences the growth factor and protease concentrations. J Orthop Sci. 2016;21(5):683‐689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abdullah BJ, Atasoy N, Omer AK. Evaluate the effects of platelet rich plasma (PRP) and zinc oxide ointment on skin wound healing. Ann Med Surg. 2019;37:30‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Singh S, Rajagopal V, Kour N, Rao M, Rao R. Platelet‐rich plasma injection and becaplermin gel as effective dressing adjuvants for treating chronic nonhealing ulcers in patients with junctional epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(4):e185‐e186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yi Z, Song N, Chen Z, Fan Y, Liu Y, Zhang B. Autologous platelet‐rich plasma in the treatment of refractory wounds in cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis complicated with hypertension (grade 2 moderate risk): A case report.. Transfus Apher Sci. 2021;60(4):103157‐103157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hermida‐Nogueira L, Barrachina MN, Morán LA, et al. Deciphering the secretome of leukocyte‐platelet rich fibrin: towards a better understanding of its wound healing properties. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hsu Y‐K, Sheu S‐Y, Wang C‐Y, et al. The effect of adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells and chondrocytes with platelet‐rich fibrin releasates augmentation by intra‐articular injection on acute osteochondral defects in a rabbit model. The Knee. 2018;25(6):1181‐1191. 10.1016/j.knee.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mirhaj M, Tavakoli M, Varshosaz J, et al. Platelet rich fibrin containing nanofibrous dressing for wound healing application: fabrication, characterization and biological evaluations. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;112541. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tavakoli M, Mirhaj M, Labbaf S, et al. Fabrication and evaluation of Cs/PVP sponge containing platelet‐rich fibrin as a wound healing accelerator: an in vitro and in vivo study. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;204:254‐257. 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ding L, Tang S, Liang P, Wang C, Zhou P‐f, Zheng L. Bone regeneration of canine peri‐implant defects using cell sheets of adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells and platelet‐rich fibrin membranes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77(3):499‐514. 10.1016/j.joms.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jee Y‐J. Use of platelet‐rich fibrin and natural bone regeneration in regenerative surgery. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;45(3):121‐122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pinto NR, Ubilla M, Zamora Y, Del Rio V, Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Quirynen M. Leucocyte‐and platelet‐rich fibrin (L‐PRF) as a regenerative medicine strategy for the treatment of refractory leg ulcers: a prospective cohort study. Platelets. 2018;29(5):468‐475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sanchez‐Avila RM, Merayo‐Lloves J, Riestra AC, et al. Plasma rich in growth factors membrane as coadjuvant treatment in the surgery of ocular surface disorders. Medicine. 2018;97(17):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xu F, Zou D, Dai T, et al. Effects of incorporation of granule‐lyophilised platelet‐rich fibrin into polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel on wound healing. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cabaro S, D'Esposito V, Gasparro R, et al. White cell and platelet content affects the release of bioactive factors in different blood‐derived scaffolds. Platelets. 2018;29(5):463‐467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Varaprasad K, Jayaramudu T, Kanikireddy V, Toro C, Sadiku ER. Alginate‐based composite materials for wound dressing application: a mini review. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;236:116025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Liang M, Chen Z, Wang F, Liu L, Wei R, Zhang M. Preparation of self‐regulating/anti‐adhesive hydrogels and their ability to promote healing in burn wounds. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2019;107(5):1471‐1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Miguel SP, Moreira AF, Correia IJ. Chitosan based‐asymmetric membranes for wound healing: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;127:460‐475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li X, Jiang Y, Wang F, et al. Preparation of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel and its performance enhancement via compositing with silver particles. RSC Adv. 2017;7(73):46480‐46485. 10.1039/C7RA08845K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Natarajan S, Harini K, Gajula GP, Sarmento B, Neves‐Petersen MT, Thiagarajan V. Multifunctional magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: diverse synthetic approaches, surface modifications, cytotoxicity towards biomedical and industrial applications. BMC Mater. 2019;1(1):1‐22. 10.1186/s42833-019-0002-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Percival SL, McCarty SM. Silver and alginates: role in wound healing and biofilm control. Adv Wound Care. 2015;4(7):407‐414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hixon KR, Klein RC, Eberlin CT, et al. A critical review and perspective of honey in tissue engineering and clinical wound healing. Adv Wound Care. 2019;8(8):403‐415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gizaw M, Thompson J, Faglie A, Lee S‐Y, Neuenschwander P, Chou S‐F. Electrospun fibers as a dressing material for drug and biological agent delivery in wound healing applications. Bioengineering. 2018;5(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Brumberg V, Astrelina T, Malivanova T, Samoilov A. Modern wound dressings: hydrogel dressings. Biomedicines. 2021;9(9):1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Soleymani Eil Bakhtiari S, Bakhsheshi‐Rad HR, Karbasi S, et al. 3‐dimensional printing of hydrogel‐based nanocomposites: a comprehensive review on the technology description, properties, and applications. Adv Eng Mater. 2021;23(10):1‐21. 10.1002/adem.202100477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zarrintaj P, Moghaddam AS, Manouchehri S, et al. Can regenerative medicine and nanotechnology combine to heal wounds? The search for the ideal wound dressing. Nanomedicine. 2017;12(19):2403‐2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wang Y, Armato U, Wu J. Targeting tunable physical properties of materials for chronic wound care. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Brusatin G, Panciera T, Gandin A, Citron A, Piccolo S. Biomaterials and engineered microenvironments to control YAP/TAZ‐dependent cell behaviour. Nat Mater. 2018;17(12):1063‐1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Seidel D, Diedrich S, Herrle F, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy vs conventional wound treatment in subcutaneous abdominal wound healing impairment: the SAWHI randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(6):469‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Omar M, Gathen M, Liodakis E, et al. A comparative study of negative pressure wound therapy with and without instillation of saline on wound healing. J Wound Care. 2016;25(8):475‐478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Galiano RD, Hudson D, Shin J, et al. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy for prevention of wound healing complications following reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Frazee R, Manning A, Abernathy S, et al. Open vs closed negative pressure wound therapy for contaminated and dirty surgical wounds: a prospective randomized comparison. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(4):507‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hall KD, Patterson JS. Three cases describing outcomes of negative‐pressure wound therapy with instillation for complex wound healing. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2019;46(3):251‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ueno T, Omi T, Uchida E, Yokota H, Kawana S. Evaluation of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. J Nippon Med Sch. 2014;81(1):4‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Perren S, Gatt A, Papanas N, Formosa C. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in ischaemic foot ulcers in type 2 diabetes: a clinical trial. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2018;12:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lansdorp CA, Buskens CJ, Gecse KB, D'Haens GR, Van Hulst RA. Wound healing of metastatic perineal Crohn's disease using hyperbaric oxygen therapy: a case series. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8(7):820‐827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kajagar BM, Godhi AS, Pandit A, Khatri S. Efficacy of low level laser therapy on wound healing in patients with chronic diabetic foot ulcers—a randomised control trial. Indian J Surg. 2012;74(5):359‐363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Vitse J, Bekara F, Byun S, Herlin C, Teot L. A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled randomized evaluation of the effect of low‐level laser therapy on venous leg ulcers. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2017;16(1):29‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kohale BR, Agrawal AA, Raut CP. Effect of low‐level laser therapy on wound healing and patients' response after scalpel gingivectomy: a randomized clinical split‐mouth study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2018;22(5):419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Choi YH, Cho YS, Lee JH, et al. Cadaver skin allograft may improve mortality rate for burns involving over 30% of total body surface area: a propensity score analysis of data from four burn centers. Cell Tissue Bank. 2018;19(4):645‐651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Costa BA, Lima Júnior EM, de Moraes Filho MO, et al. Use of tilapia skin as a xenograft for pediatric burn treatment: a case report. J Burn Care Res. 2019;40(5):714‐717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zuo KJ, Umraw N, Cartotto R. Scar quality of skin graft borders: a prospective, randomized, double‐blinded evaluation. J Burn Care Res. 2019;40(5):529‐534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kirsner RS, Margolis DJ, Baldursson BT, et al. Fish skin grafts compared to human amnion/chorion membrane allografts: a double‐blind, prospective, randomized clinical trial of acute wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2020;28(1):75‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sheckter CC, Meyerkord NL, Sinskey YL, Clark P, Anderson K, Van Vliet M. The optimal treatment for partial thickness burns: a cost‐utility analysis of skin allograft vs. topical silver dressings. J Burn Care Res. 2020;41(3):450‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Momeni M, Fallah N, Bajouri A, et al. A randomized, double‐blind, phase I clinical trial of fetal cell‐based skin substitutes on healing of donor sites in burn patients. Burns. 2019;45(4):914‐922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Molnar JA, Walker N, Steele TN, et al. Initial experience with autologous skin cell suspension for treatment of deep partial‐thickness facial burns. J Burn Care Res. 2020;41(5):1045‐1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Maghsoudi H, Nezami N, Mirzajanzadeh M. Enhancement of burn wounds healing by platelet dressing. Int J Burns Trauma. 2013;3(2):96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Prochazka V, Klosova H, Stetinsky J, et al. Addition of platelet concentrate to dermo‐epidermal skin graft in deep burn trauma reduces scarring and need for revision surgeries. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky, Olomouc, Czech Repub. 2014;158(2):242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Marck RE, Gardien KL, Stekelenburg CM, et al. The application of platelet‐rich plasma in the treatment of deep dermal burns: a randomized, double‐blind, intra‐patient controlled study. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(4):712‐720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kızıltoprak M, Uslu MÖ. Comparison of the effects of injectable platelet‐rich fibrin and autologous fibrin glue applications on palatal wound healing: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:4549‐4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Totsuka Sutto SE, Rodríguez Roldan YI, Cardona Muñoz EG, et al. Efficacy and safety of the combination of isosorbide dinitrate spray and chitosan gel for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a double‐blind, randomized, clinical trial. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2018;15(4):348‐351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Halim AS, Nor FM, Saad AZM, Nasir NAM, Norsa'adah B, Ujang Z. Efficacy of chitosan derivative films versus hydrocolloid dressing on superficial wounds. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2018;13(6):512‐520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Mahajan M, Gupta MK, Bande C, Meshram V. Comparative evaluation of healing pattern after surgical excision of oral mucosal lesions by using platelet‐rich fibrin (PRF) membrane and collagen membrane as grafting materials—a randomized clinical trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;76(7):1469.e1‐1469.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Abdollahimajd F, Moravvej H, Dadkhahfar S, Mahdavi H, Mohebali M, Mirzadeh H. Chitosan‐based biocompatible dressing for treatment of recalcitrant lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis: a pilot clinical study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:609‐614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Tsai H‐C, Shu H‐C, Huang L‐C, Chen C‐M. A randomized clinical trial comparing a collagen‐based composite dressing versus topical antibiotic ointment on healing full‐thickness skin wounds to promote epithelialization. Formos J Surg. 2019;52(2):52. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Park KH, Kwon JB, Park JH, Shin JC, Han SH, Lee JW. Collagen dressing in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer: a prospective, randomized, placebo‐controlled, single‐center study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;156:107861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Djavid GE, Tabaie SM, Tajali SB, et al. Application of a collagen matrix dressing on a neuropathic diabetic foot ulcer: a randomised control trial. J Wound Care. 2020;29(Sup3):S13‐S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Haque AE, Ranganath K, Prasad K, Munoyath SK, Lalitha R. Effectiveness of chitosan versus collagen membrane for wound healing in maxillofacial soft tissue defects: a comparative clinical study. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs. 2020;34(2):61‐66. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Femminella B, Iaconi MC, Di Tullio M, et al. Clinical comparison of platelet‐rich fibrin and a gelatin sponge in the management of palatal wounds after epithelialized free gingival graft harvest: a randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2016;87(2):103‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ehab K, Abouldahab O, Hassan A, El‐Sayed KMF. Alvogyl and absorbable gelatin sponge as palatal wound dressings following epithelialized free gingival graft harvest: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24(4):1517‐1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Davidson A, Jina NH, Marsh C, Than M, Simcock JW. Do functional keratin dressings accelerate epithelialization in human partial thickness wounds? A randomized controlled trial on skin graft donor sites. Eplasty. 2013;13:375‐381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Jull A, Wadham A, Bullen C, Parag V, Weller C, Waters J. Wool‐derived keratin dressings versus usual care dressings for treatment of slow healing venous leg ulceration: a randomised controlled trial (Keratin4VLU). BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e036476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]