Abstract

Background

Patients with autism spectrum disorder often show altered responses to sensory stimuli as well as motor deficits, including an impairment of delay eyeblink conditioning, which involves integration of sensory signals in the cerebellum. Here, we identify abnormalities in parallel fiber (PF) and climbing fiber (CF) signaling in the mouse cerebellar cortex that may contribute to these pathologies.

Methods

We used a mouse model for the human 15q11-13 duplication (patDp/+) and studied responses to sensory stimuli in Purkinje cells from awake mice using two-photon imaging of GCaMP6f signals. Moreover, we examined synaptic transmission and plasticity using in vitro electrophysiological, immunohistochemical, and confocal microscopic techniques.

Results

We found that spontaneous and sensory-evoked CF-calcium transients are enhanced in patDp/+ Purkinje cells, and aversive movements are more severe across sensory modalities. We observed increased expression of the synaptic organizer NRXN1 at CF synapses and ectopic spread of these synapses to fine dendrites. CF–excitatory postsynaptic currents recorded from Purkinje cells are enlarged in patDp/+ mice, while responses to PF stimulation are reduced. Confocal measurements show reduced PF+CF-evoked spine calcium transients, a key trigger for PF long-term depression, one of several plasticity types required for eyeblink conditioning learning. Long-term depression is impaired in patDp/+ mice but is rescued on pharmacological enhancement of calcium signaling.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that this genetic abnormality causes a pathological inflation of CF signaling, possibly resulting from enhanced NRXN1 expression, with consequences for the representation of sensory stimuli by the CF input and for PF synaptic organization and plasticity.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Cerebellum, Motor function, Purkinje cell, Sensory input

Synaptopathies play a dominant role in autism (1, 2, 3). However, it is difficult to directly relate synaptic to social abnormalities (4). A promising complementary approach is to study simple motor behaviors—more easily linked to their underlying circuits—in the cerebellum (5,6). Impaired motor coordination is a common feature of autism spectrum disorder (ASD); a majority of children with ASD show motor problems (7,8), including difficulties with eye movement control (9,10) and impaired delay eyeblink conditioning (EBC) (11,12), a form of associative learning that requires the cerebellum (13). These findings place the cerebellum aside other brain structures that contribute to ASD-related behavioral abnormalities (14). The advantages for circuit approaches are obvious: the cerebellum and its circuit architecture are conserved throughout vertebrate evolution, and results from EBC studies can be compared between humans and mice (15).

In previous work, we have shown that EBC is impaired in a mouse model for the human 15q11-13 duplication (5), a copy number variation that is one of the most frequent and penetrant genetic ASD causes (16) and is associated with motor problems (17). In this model, mice inheriting the duplication paternally (patDp/+) show ASD-resembling deficits in social behaviors (18). In patDp/+ mice, we observed not only impaired delay EBC but also impaired long-term depression (LTD) at parallel fiber (PF)–Purkinje cell (PC) synapses (5,19). LTD is one of several plasticity mechanisms that contribute to this type of associative learning (20,21). In addition, blockade of long-term potentiation (LTP) at PF synapses (22), plasticity of inhibitory synapses (23), and intrinsic plasticity in PCs (24) have been found to reduce delay EBC performance. LTD is triggered by repetitive coactivation of PF and climbing fiber (CF) inputs (25,26) and is controlled by spine calcium signaling, because LTD has a higher calcium threshold than LTP (27, 28, 29). The olivocerebellar system plays a key role in this type of plasticity; the CF input conveys an error signal, for example in response to an airpuff directed to the eye in EBC (unconditioned stimulus). The contribution of CF signaling to LTD induction consists of an enhancement of the calcium signal in PF-contacted spines. Here, we focus on the characterization of physiological abnormalities that cause the deregulation of LTD, with a particular focus on aberrant CF signaling.

We found that the two types of excitatory input to PCs are altered in patDp/+ mice: PF synapses are weakened, whereas CF synapses are strengthened. Two-photon recordings reveal that CF-evoked calcium transients in response to sensory input are enhanced in awake patDp/+ mice, which also show stronger aversive motor responses, including faster eyelid closure when corneal airpuffs are applied. We found ectopic CF synapses on fine dendritic branches, together with increased expression of NRXN1. PF-evoked spine calcium transients are reduced. LTD is blocked in patDp/+ mice but is rescued on pharmacological enhancement of calcium signaling with the ampakine CX546 (30). Thus, the 15q11-13 duplication results in pathologically enhanced CF signaling with consequences for PF input organization and plasticity and for the representation of sensory stimuli.

Methods and Materials

Animals

We used both male and female mice aged ∼1 to 5 months. The patDp/+ mouse model for the human 15q11-13 duplication has been described elsewhere (18) (mice were obtained from Dr. Toru Takumi). These mice carry a 6.3-Mb interstitial duplication of the conserved linkage group on mouse chromosome 7. The mice were backcrossed on a C57BL/6J background for more than 10 generations and maintained on this genetic background. Mice were kept in 12-hour light/dark cycles and had access to food and water ad libitum. The experiments were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Chicago.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Images obtained during two-photon recordings were processed and motion corrected using custom MATLAB scripts (version 2017b; The MathWorks, Inc.), and cellular regions of interest were drawn manually in ImageJ based on volumetric cell reconstructions. Calcium signal was extracted for each region of interest and compiled for analysis using custom MATLAB (version 2020a) and R scripts. For statistical analysis, paired t test was used to compare within groups. Mann-Whitney U test was used for between-group comparisons. Immunohistochemistry and multisensory two-photon data were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance and post hoc Tukey tests.

Results

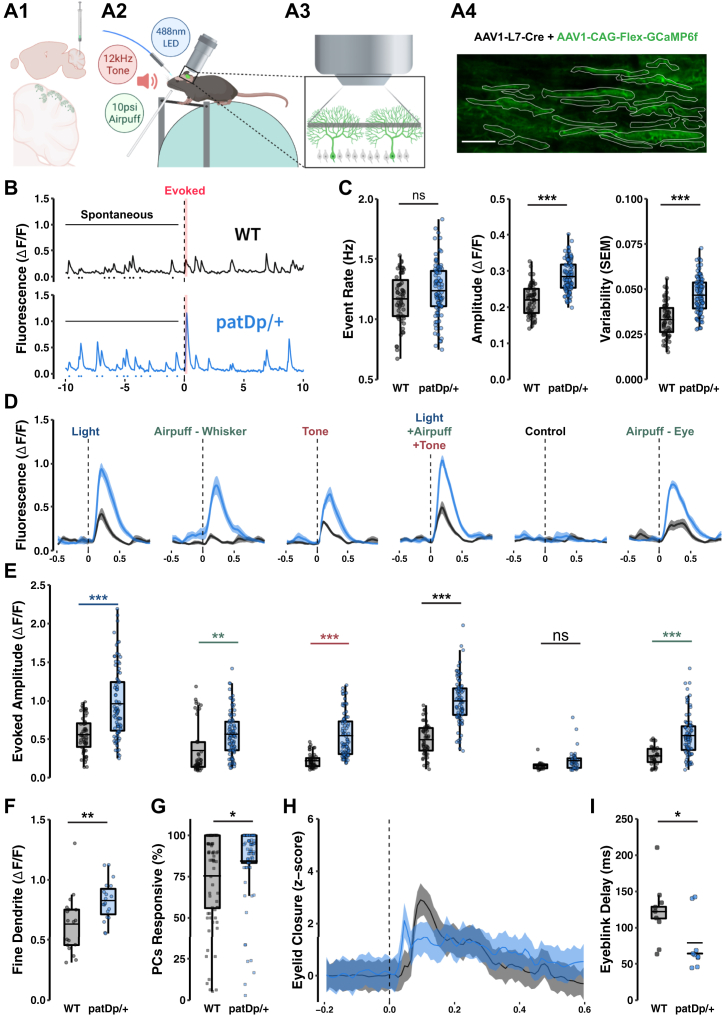

To assess whether olivocerebellar signaling is altered in patDp/+ mice, we performed two-photon imaging from crus I in awake mice that express the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f under control of the PC-specific promoter L7-cre (dual viral injection of GCaMP6f and L7-Cre AAV). PCs located in crus I are responsive to a wide range of sensory modalities (31). In these recordings, dendritic arbors of 15 to 25 PCs viewed from the top appear as thin stripes (Figure 1A). Calcium transients were calculated as ΔF/F values. Under spontaneous firing conditions, the calcium event rate was not significantly different between PCs from wild-type (WT) and patDp/+ mice (WT: 1.17 ± 0.03 Hz, n = 55 cells, 3 mice; patDp/+: 1.24 ± 0.02 Hz, n = 87 cells, 3 mice; p = .068) (Figure 1B, C). However, both the calcium transient amplitude and its variability (standard error of event amplitudes for each cell) were significantly enhanced in patDp/+ mice (amplitude: WT: 0.22 ± 0.006 ΔF/F, patDp/+: 0.28 ± 0.005 ΔF/F, p = 3.387 × 10−14; variability: WT: 0.0331 ± 0.0013 SEM, patDp/+: 0.0467 ± 0.0011 SEM, p = 3.054 × 10−13) (Figure 1B, C).

Figure 1.

Spontaneous and sensory-evoked climbing fiber–mediated calcium events in PC dendrites are enhanced in awake patDp/+ mice. (A1) Dual viral injection of 2% AAV1-L7-Cre and 10% AAV1-CAG-Flex-GCaMP6f produces strong expression in sparse PC populations in cerebellar crus 1. (A2) Schematic of the in vivo recording condition with light, airpuff, and sound stimuli administered while a mouse is head-fixed over a treadmill. (A3) Two-photon scanning of intermediate dendrites yielded clear, cell-wide dendritic calcium influx events. (A4) Sample imaging field of view with the dendrites of 19 healthy, active PCs. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Sample fluorescence traces extracted from individual cell regions of interest during a 20-second recording session with a light stimulus after 10 seconds. Spontaneous events were measured during the 0–9 seconds time frame before stimulus in each trial while evoked responses were measured during the 240-ms poststimulus window (red). (C) Quantification of spontaneous event rates, amplitudes, and amplitude variability for each cell by genotype (WT, n = 55; patDp/+, n = 87). (D) Example traces from 1 WT and 1 patDp/+ cell highlighting trial-averaged evoked responses to sensory stimuli and control conditions (30-ms stimuli, 10 trials each). Light and airpuff stimuli were targeted to the ipsilateral eye or whisker pad. Tone stimuli were delivered through bilateral speakers. (E) Quantification of evoked response amplitudes for all cells in all animals by genotype (WT, n = 55; patDp/+, n = 87). (F) Quantification of evoked responses to light stimulus exclusively in fine dendrites in a subset of cells where large-caliber and fine dendrites were easily distinguished (WT, n = 19; patDp/+, n = 19). (G) Percentage of cells in a field of view producing an evoked response in the 240-ms window during each trial (three trials of eight stimulus types each for 3 animals per genotype; WT, n = 72; patDp/+, n = 72). The dashed line indicates the prediction that 25% of independently active cells with an average event rate of ∼1 Hz are expected to be active at baseline during a 240-ms time window. (H) Genotype average z score traces of the pixel intensity change in a region of interest encompassing the ipsilateral eye. Traces normalized to the mean z score value during 1.5 seconds before stimulus (WT, n = 9; patDp/+, n = 9). (I) Quantification of the delay to peak change in intensity by genotype (WT, n = 9; patDp/+, n = 9). ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .005. Boxplots show mean line with interquartile range. Boxplot error bars show the least extreme of either the highest and lowest values or mean ± (1.5 × interquartile range). All traces show mean ± SEM. All data are noted in the text and legends as mean ± SEM. LED, light-emitting diode; ns, not significant; PC, Purkinje cell; WT, wild-type.

The amplitudes of calcium transients evoked by application of sensory stimuli were also significantly larger in PCs from patDp/+ mice than WT mice (stimuli were applied in random order using interstimulus intervals ≥30 s). This holds true when light pulses (488-nm light-emitting diode, 30 ms) were directed to the ipsilateral eye (WT: 0.56 ± 0.03 ΔF/F; patDp/+: 0.96 ± 0.05 ΔF/F; p = 1.36 × 10−13), airpuffs (10 psi, 30 ms) were directed to the ipsilateral whisker field (WT: 0.35 ± 0.04 ΔF/F; patDp/+: 0.56 ± 0.03 ΔF/F; p = .005), auditory stimuli (12 kHz pure tone, 70–80 dB; 30 ms) were presented (WT: 0.22 ± 0.01 ΔF/F; patDp/+: 0.54 ± 0.03 ΔF/F; p = 2.86 × 10−8), or all three stimuli were applied together (WT: 0.49 ± 0.03 ΔF/F; patDp/+: 0.99 ± 0.03 ΔF/F; p ≤ 1 × 10−15; for all stimulus conditions: WT: n = 55 cells, 3 mice; patDp/+: n = 87 cells, 3 mice) (Figure 1D, E). Under control conditions (no stimulus), the largest calcium events within the same time window were 0.15 ± 0.01 ΔF/F (WT) and 0.22 ± 0.01 ΔF/F (patDp/+). Finally, as a reference measure, we applied airpuffs (10 psi, 30 ms) to the ipsilateral eye. This stimulus is used as the unconditioned stimulus in EBC and is known to evoke complex spikes. The resulting response amplitude in WT mice was 0.28 ± 0.02 ΔF/F, while in patDp/+ mice, it was 0.54 ± 0.03 ΔF/F (p = .001). These findings confirm previous observations that evoked calcium events are larger than spontaneous ones (32,33) and show that the amplitudes of spontaneous and evoked calcium events are significantly larger in PCs from patDp/+ than WT mice. While it is known that evoked calcium events can result from a mixture of both CF and PF signals (32,33), the enhanced amplitude of sensory-evoked calcium transients observed in patDp/+ mice at least partially reflects a change in CF signal. This is concluded because the amplitude of spontaneous calcium events—which occur at a frequency around 1 Hz that is characteristic of spontaneous CF firing (34)—is similarly enhanced.

The recordings described earlier were performed from PC dendrites, roughly at equal distance from the soma and the pial surface. This measure includes dendritic compartments of various calibers. When analysis was restricted to calcium transients from fine dendrites [the PF input territory; see below (35)], we still observed larger calcium transients in patDp/+ PCs (0.83 ± 0.04 ΔF/F; n = 19; 2 mice; analyzed for the light stimulus) than in WT PCs (0.63 ± 0.06 ΔF/F; n = 19; 2 mice; p = .008) (Figure 1F). These findings show that the CF-evoked calcium transients within the PF input zone are significantly enhanced in the ASD mouse model. The number of PCs showing an above-threshold calcium response was also enhanced in patDp/+ mice. Of the 15 to 25 PCs that we recorded from in each experiment, in WT mice, 75.2 ± 3.3% responded, while in patDp/+ mice, 85.5 ± 2.6% responded within a time window of 240 ms after stimulus onset (p = .000248; analyzed for all stimulus types combined; 3 trials per each of 8 stimulus types; 3 mice per genotype) (Figure 1G; Figure S1).

Sensory stimulation also caused enhanced motor responses in patDp/+ mice. For example, corneal airpuff stimulation initiated eyelid closure that occurred with shorter delays in patDp/+ mice (WT: 121.86 ± 14.5 ms; patDp/+: 78.85 ± 12.74 ms; both genotypes: n = 9; p = .0408) (Figure 1H, I) and longer persisting closure (Figure S2). Similarly, we observed enhanced movement of the front ipsilateral paw, facial structures (nose and ear), and chest in patDp/+ mice (Figures S3–S5). Together, these findings point toward an increased sensitivity to sensory stimuli.

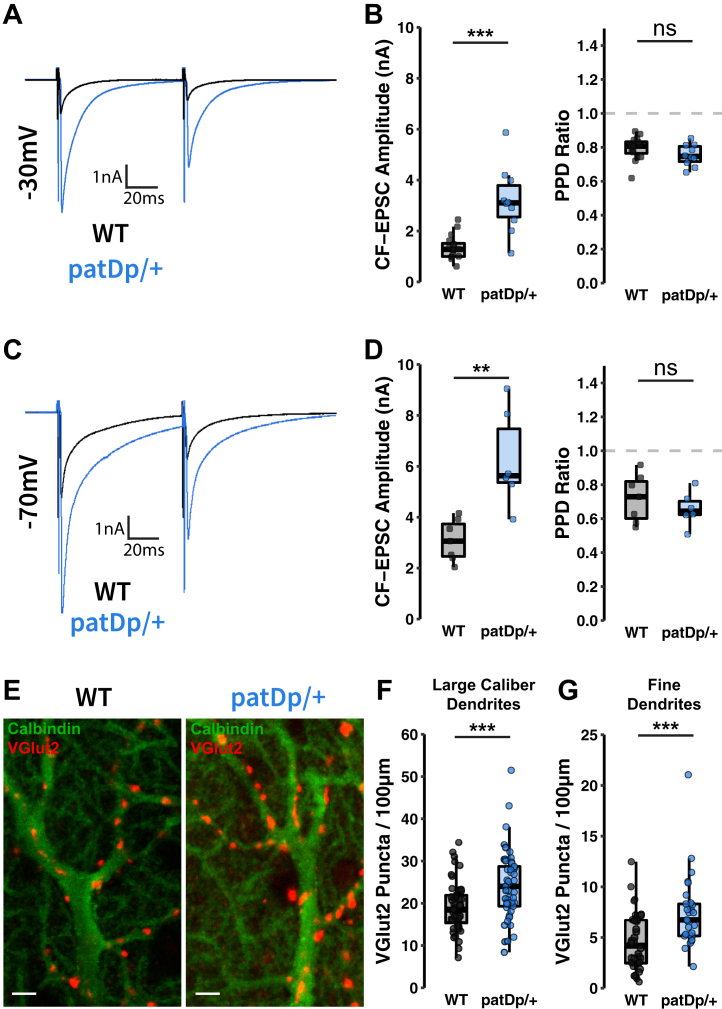

Differences in the amplitude of CF-evoked calcium transients may arise from changes in postsynaptic responsiveness but can also result from changes in presynaptic CF activity (36,37). To obtain an independent confirmation that CF signaling is enhanced in patDp/+ mice and that this effect can be a consequence of postsynaptic alterations, we applied single CF stimuli in vitro and examined CF–excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in patch-clamp recordings from PCs. In WT mice, the amplitude of CF-EPSCs recorded at a −30 mV holding potential was 1.36 ± 0.12 nA (n = 16). CF-EPSC amplitudes recorded in patDp/+ mice were significantly higher (3.19 ± 0.41 nA; n = 10; p = .0005; Mann-Whitney U test) (Figure 2A, B). At −70 mV holding potential, the CF-EPSC amplitudes recorded in WT PCs amounted to 3.09 ± 0.31 nA (n = 7), while those recorded from patDp/+ PCs reached 6.27 ± 0.78 nA (n = 6; p = .008) (Figure 2C, D). The paired-pulse depression ratio (EPSC2/EPSC1) did not differ between the genotypes at either holding potential (−30 mV: WT: 0.79 ± 0.02, n = 16; patDp/+: 0.75 ± 0.02, n = 10; p = .1615; −70 mV: WT: 0.72 ± 0.05; n = 7; patDp/+: 0.66 ± 0.04, n = 6; p = .432) (Figure 2B, D). These observations suggest that CF signaling is postsynaptically enhanced in patDp/+ mice, but they do not exclude the possibility of an additional change in CF burst firing.

Figure 2.

CF-PC synaptic transmission is enhanced in patDp/+ mice. (A) Typical CF-EPSCs recorded in WT and patDp/+ PCs at a holding potential of −30 mV. (B) Paired CF stimulations with a 100-ms interval show enhanced CF-EPSC amplitudes but equivalent paired-pulse depression in patDp/+ PCs compared with WT PCs (patDp/+, n = 10; WT, n = 16). (C) Typical CF-EPSCs recorded at a holding potential of −70 mV. (D) Again, paired CF stimulations show enhanced CF-EPSC amplitudes and equivalent paired-pulse depression in patDp/+ PCs compared with WT PCs (patDp/+, n = 6; WT, n = 7, respectively). (E–G) Dual label immunohistochemistry stains for calbindin (PCs) and VGlut2 (CF presynaptic terminals) in WT and patDp/+ cerebellar tissue reveals CF terminal arrangement on PC dendrites. Quantifying the number of VGlut2 puncta per 100-μm lengths of dendrite shows increased density of CF inputs to both (F) large-caliber (>2 μm) primary dendrites (patDp/+, n = 49; WT, n = 45) and (G) fine dendritic branches (patDp/+, n = 28; WT, n = 34). Scale bar = 2 μm. ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .005. Boxplots show mean line with interquartile range. Boxplot error bars show the least extreme of either the highest and lowest values or mean ± (1.5 × interquartile range). All data are shown as median ± SEM. CF, climbing fiber; EPSC, excitatory postsynaptic current; ns, not significant; PC, Purkinje cell; PPD, paired-pulse depression; WT, wild-type.

The observed differences in CF response amplitudes may be associated with altered CF innervation. Developmental elimination of surplus CFs is delayed but reaches completion in patDp/+ mice (5). In the adult cerebellum, CF synapses contact spines on the primary dendrite and first-degree branches, while PF synapses contact spines on higher-order branches (we use here the terms “large-caliber dendrites” and “fine dendrites”) (35). We used co-immunolabeling of cerebellar sections for the PC-specific marker calbindin and the CF terminal marker VGluT2 and segregated dendrites in the molecular layer into large-caliber (>2-μm diameter) and fine dendrites to assess the distribution and density of CF terminals. We observed that the density of VGluT2-stained terminals on proximal, large-caliber dendrites was enhanced in patDp/+ mice (24.18 ± 1.17 VGluT2 spots/100 μm; n = 49 sections, 6 mice) as compared with WT mice (19.23 ± 0.9 VGluT2 spots/100 μm; n = 45 sections, 7 mice; p = .0014) (Figure 2E, F). Similarly, we observed a higher density of VGluT2 terminals on fine dendrites of patDp/+ mice (7.52 ± 0.68 VGluT2 spots/100 μm; n = 28 sections, 6 mice) than WT mice (4.59 ± 0.5 VGluT2 spots/100 μm; n = 34 sections, 7 mice; p = .0019) (Figure 2E, G). These findings show that in patDp/+ mice, the CF input forms ectopic synapses on fine dendrites.

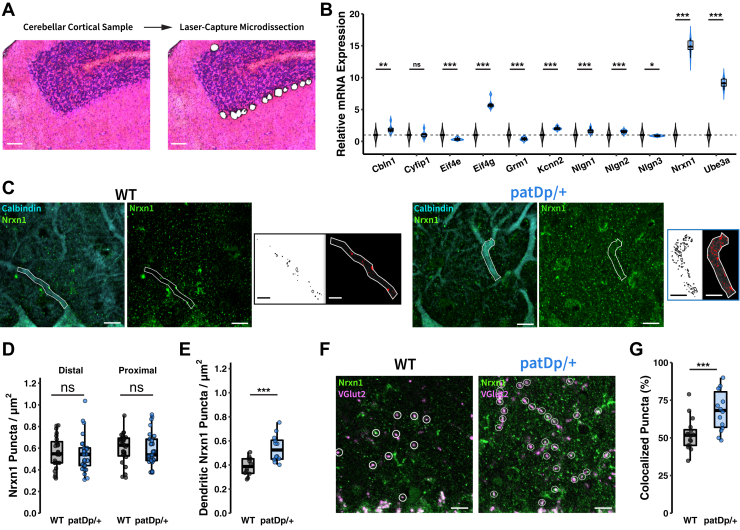

The mouse model for the human 15q11-13 duplication is based on an interstitial duplication of the conserved linkage group on mouse chromosome 7, which is composed of about 23 genes (18). This group includes the ubiquitin protein ligase gene Ube3a, which is upregulated in patDp/+ mice (5). To assess transcription profiles, we performed laser capture microdissection of PCs and quantified messenger RNA (mRNA) content by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for selected candidate genes. The laser microdissection led to the collection of PC somata (Figure 3A), likely including proximal dendritic stumps, axon initial segments, and attached (mostly CF) synaptic terminals. In our selection of candidate mRNAs to be tested, we focused (Figure 3B) on the synaptic organizer molecules neuroligin 1-3 (Nlgn1, Nlgn2, Nlgn3), cerebellin 1 (Cbln1), and neurexin 1 (Nrxn1); Ube3a; the translation control factors CYFIP1 (Cyfip1), eIF4E (Eif4e), and eIF4G (Eif4g); mGlu1 receptors (Grm1); and SK2-type K+ channels (Kcnn2). (For information on these genes, see Mouse Genome Database; http://www.informatics.jax.org.) Several of these mRNAs showed significant changes in expression levels (Figure 3B), but we focused on Nrxn1 because its change in mRNA levels was the most pronounced (increase over WT: 1487.3 ± 46.0%; p = 3.7822 × 10−11).

Figure 3.

Altered expression and localization of the presynaptic organizer NRXN1. (A) Sample cerebellar cortical tissue before and after laser capture microdissection of Purkinje cell somatic regions for mRNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction quantification. Scale bars = 50 μm. (B) Relative mRNA expression of genes of interest (n = 6, 6). (C) Triple label immunohistochemistry stains for calbindin (Purkinje cells), NRXN1, and VGlut2 (hidden for clarity) in WT and patDp/+ cerebellar tissue reveals NRXN1 localization patterns across the broad molecular layer and within sections of primary dendritic branches. Scale bars = 10 μm. NRXN1 channel thresholding highlights signal and objects detected in dendritic regions. Scale bars = 5 μm. (D) Quantifying the number of NRXN1 puncta across broad sections of the molecular layer does not reveal altered NRXN1 expression (WT, n = 24 sections; patDp/+, n = 25 sections). (E) Examining NRXN1 expression specifically in primary dendritic sections reveals enhanced NRXN1 puncta in patDp/+ tissue (n = 12) compared with WT (n = 12). (F) Manually counting and labeling VGlut2 puncta as NRXN1+ or NRXN1− further defines the role of NRXN1 in enhanced CF–Purkinje cell transmission. Scale bars = 10 μm. (G) Colocalization analysis shows increased NRXN1 expression on climbing fiber terminals in patDp/+ tissue (n = 14) compared with WT (n = 16). ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .005. Boxplots show mean line with interquartile range. Boxplot error bars show the least extreme of either the highest and lowest values or mean ± (1.5 × interquartile range). All data are shown as median ± SEM. mRNA, messenger RNA; ns, not significant; WT, wild-type.

NRXN1 acts as a presynaptic organizer at both PF [with cerebellin 1 as binding partner (38,39)] and CF synapses [with neuroligins 1 and 3 as binding partners (40,41)]. We performed immunohistochemical analysis using antibodies against calbindin and NRXN1 to assess whether NRXN1 levels are enhanced at these synapses. We did not find a difference in expression levels between WT and patDp/+ mice in either distal or proximal molecular layer compartments (Figure 3C, D). We did note, however, a large range in NRXN1 counts, even in WT mice, which suggests that this measure may be affected by unspecific background stains and/or fluorescence from different focus planes. To overcome this problem, we next restricted analysis to fluorescent punctae that are colocalized with large-caliber, proximal dendritic compartments (calbindin staining), a measure that biases the count toward NRXN1 molecules located at CF terminals (CF input zone) (35). In this measure, we observed an increase in the NRXN1 count in patDp/+ mice (0.54 ± 0.11 punctae/μm2; n = 12 sections; 6 mice) as compared with WT littermates (0.39 ± 0.07 punctae/μm2; n = 12 sections; 6 mice; p = .0035) (Figure 3C, E). To examine whether NRXN1 is expressed at enhanced rates specifically at CF terminals, we analyzed the percentage of VGluT2-labeled CF terminals that showed costaining with NRXN1. Indeed, we found that a higher proportion of CF terminals across the molecular layer showed NRXN1 costaining in patDp/+ mice (68.1 ± 13.5%; n = 14 sections; 4 mice) compared with WT mice (52.4 ± 10.7%; n = 16 sections; 4 mice; p = .0022) (Figure 3F, G). Together with the Nrxn1 mRNA increase that we observed after laser capture microdissection of PC somata (including CF terminals located on the soma and proximal dendrite), these findings suggest that the observed strengthening of CF input at least partially results from enhanced NRXN1 expression.

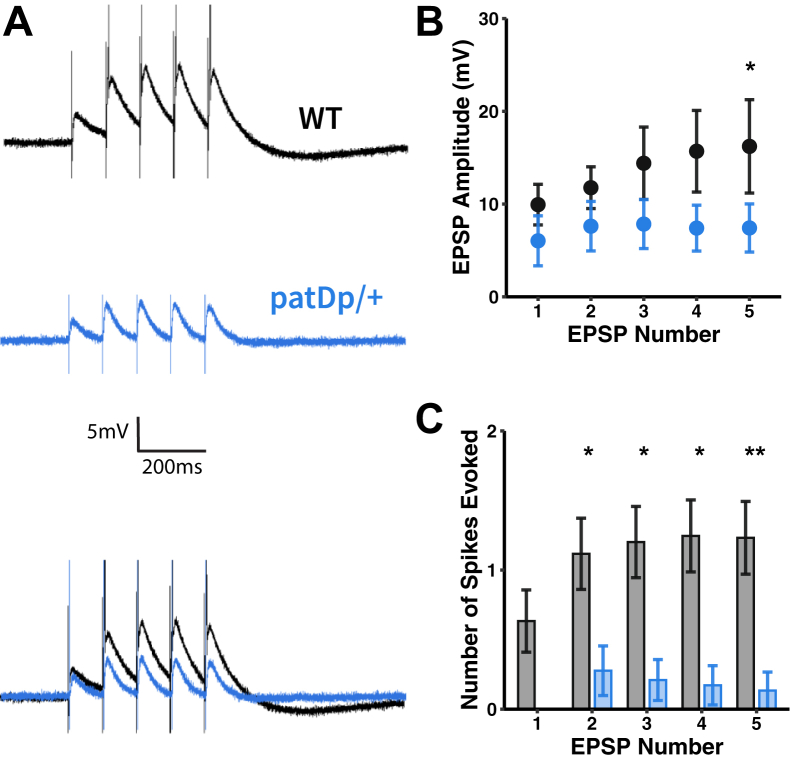

To assess whether PF synaptic transmission was similarly strengthened, we recorded responses to PF stimulation in PCs in vitro. In a previous study (5), we have shown that isolated, single PF-EPSCs are unaffected in patDp/+ mice. We now looked at more dynamic response properties and applied a train of 5 PF stimuli at 10 Hz. In WT mice, we observed a buildup of response amplitudes over the course of the stimulus train (Figure 4A), which was not seen in recordings from patDp/+ mice. Because there is no difference in the paired-pulse facilitation ratio at PF synapses between the two genotypes (5), this buildup seems to be of largely postsynaptic origin. While no significant difference was observed with regard to excitatory postsynaptic potentials 1–4, significance emerged when comparing the amplitude of excitatory postsynaptic potential 5 (WT: 17.4 ± 3.9 mV; n = 12; patDp/+: 8.3 ± 1.7 mV; n = 8; p = .03) (Figure 4B). Moreover, the number of evoked spikes (excitatory postsynaptic potential 5) was significantly lower than in WT mice (WT: 1.02 ± 0.23; patDp/+: 0.18 ± 0.10; p = .0093) (Figure 4C). A particular signaling pathway that is required at PF synapses for the induction of LTD (42,43) but not LTP (44) is the activation of mGluR1s. However, we did not find alterations in mGluR1 expression levels using western blotting analysis, nor did we find differences in an electrophysiological correlate of mGluR1 activation at PF to PC synapses—slow mGluR1-EPSCs (45) (Figure S6).

Figure 4.

PF–Purkinje cell synaptic transmission is weakened in patDp/+ mice. (A) Typical PF–EPSPs recorded in WT and patDp/+ Purkinje cells. PF stimulation at 10 Hz for 5 pulses reveals weakened PF-EPSP synaptic transmission in patDp/+ Purkinje cells, indicated by panel (B) a reduced EPSP amplitude and (C) failure to reach a potential threshold necessary to evoke spikes (WT, n = 12; patDp/+, n = 8). ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .005. Plots show mean ± SEM. All data are noted in the text and legends as mean ± SEM. EPSP, excitatory postsynaptic potential; PF, parallel fiber; WT, wild type.

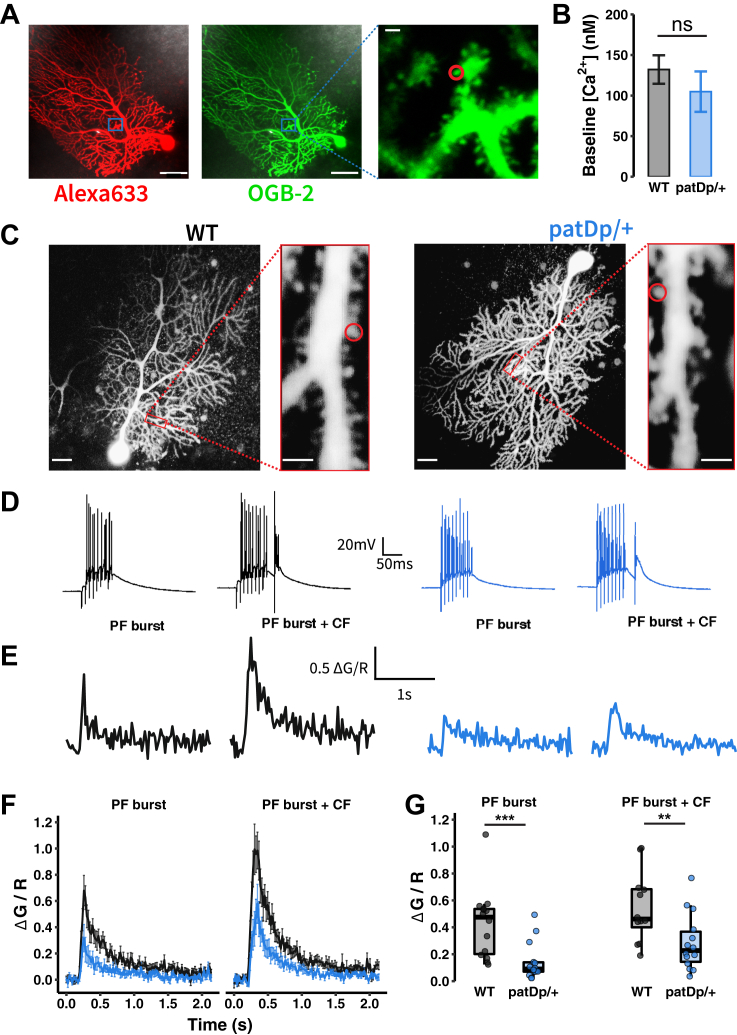

Does the altered synaptic connectivity observed result in abnormal spine calcium transients? We performed confocal recordings of calcium transients in spines on fine dendritic branches to assess whether these signals are changed in patDp/+ PCs. We began with measures of resting calcium levels using the high-affinity (Kd = 485 nM) calcium indicator Oregon Green BAPTA-2 (200 μM) that was added to the patch pipette saline together with the calcium-insensitive fluorescent dye Alexa 633 (30 μM). Calcium levels were calculated based on the measurements of G/R ratios, where G is the calcium-sensitive fluorescence of Oregon Green BAPTA-2 and R is the calcium-insensitive fluorescence of Alexa 633 (28). Resting calcium levels [Ca2+]i were not significantly different between PCs from WT (132.1 ± 17.6 nM; n = 21) and patDp/+ mice (104.8 ± 24.9 nM; n = 11; p = .1527) (Figure 5A, B). For the measurement of synaptically evoked spine calcium transients, we changed our approach slightly. First, expecting larger calcium transients than at resting state, we replaced the high-affinity calcium indicator Oregon Green BAPTA-2 with the low-affinity (Kd = 1.8 μM) indicator Fluo-5F (300 μM). Second, we switched from the calculation of absolute calcium levels [Ca2+]i to normalized calcium transients ΔG/R, which are more accurate and still allow for quantitative comparisons of calcium signals. The calcium affinity of Fluo-5F is low, and CF-evoked calcium transients in the proximal dendrite, which have low amplitudes (Figure S7), may not reliably measure amplitude differences. We therefore only provide genotype comparisons between calcium transients evoked by PF bursts (8 PF stimuli at 100 Hz) paired or not paired with a single CF stimulus (LTD stimulus, 120 ms after PF stimulus onset). We observed that application of PF bursts alone caused reduced calcium transients in spines from patDp/+ PCs (WT: 0.43 ± 0.07 ΔG/R; n = 14; patDp/+: 0.14 ± 0.04 ΔG/R; n = 14; p = .0024). PF bursts followed by a CF stimulus also caused lower calcium transients in spines from patDp/+ PCs (0.29 ± 0.06 ΔG/R; n = 14) compared with WT PCs (0.65 ± 0.1 ΔG/R; n = 14; p = .0127) (Figure 5D–G).

Figure 5.

PF-evoked calcium transients are decreased in patDp/+ Purkinje cell spines. (A) Representative images of a patDp/+ Purkinje cell filled with OGB-2 Ca2+ indicator (green) and Alexa 633 dye (red) and visualized spines from that cell. Scale bars = left, 50 μm; right, 2 μm. (B) No difference between resting concentrations of Ca2+ between WT and patDp/+ spines (WT, n = 21; patDp/+, n = 11). (C) Representative images of WT (left) and patDp/+ (right) Purkinje cells filled with Fluo-5F Ca2+ indicator and Alexa 633 dye. Red box indicates the dendrite with the maximally responding spine. Scale bars = 20 μm (cell images) and 2 μm (dendrite/spine images). (D) Electrophysiological responses from somatic whole-cell patch clamp to two stimulus types: 100-Hz PF burst of 8 pulses alone (PF burst), and a 100-Hz PF burst of 8 pulses + 1 CF pulse (PF burst+CF). (E) Typical traces of simultaneously recorded spine Ca2+ transients during each stimulus type. (F) Mean ± SEM traces of Ca2+ transients for each stimulus type between WT and patDp/+ spines (WT, n = 14; patDp/+, n = 14). (G) Quantification of Ca2+ signal peak amplitudes during a 200-ms window after stimulus onset reveals diminished PF signaling (PF burst and PF burst + CF). ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .005. Boxplots show mean line with interquartile range. Boxplot error bars show the least extreme of either the highest and lowest values or mean ± (1.5 × interquartile range). Bar plots and average traces show mean ± SEM. All data are shown as median ± SEM. CF, climbing fiber; ns, not significant. OGB, Oregon Green BAPTA; PF, parallel fiber; WT, wild-type.

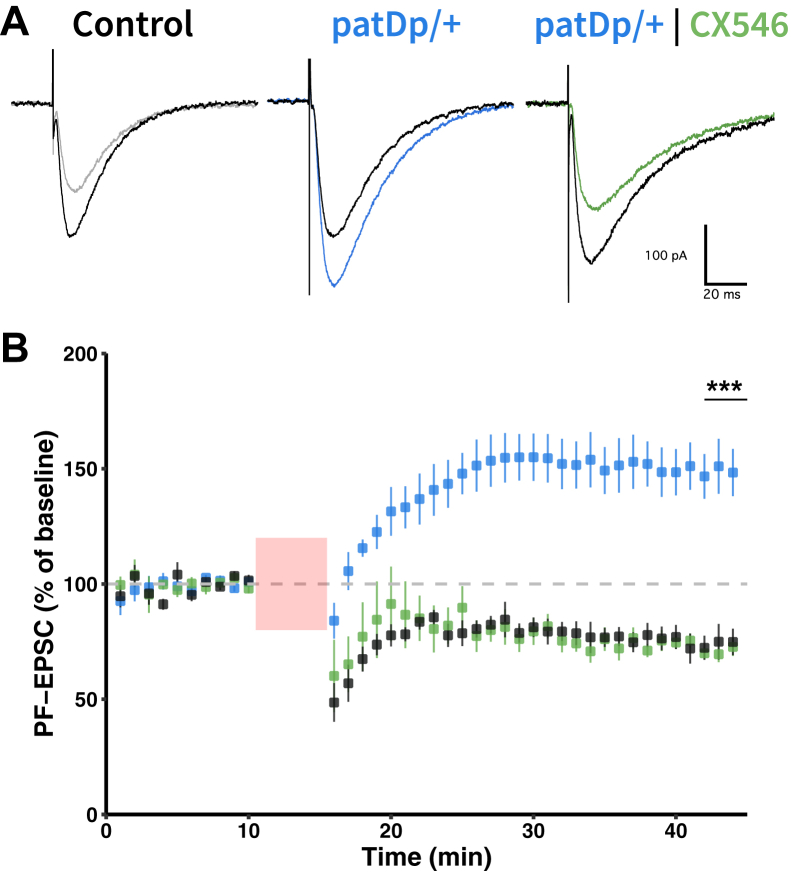

Finally, we tested whether LTD impairment resulted from reduced calcium signaling. PF-EPSCs were recorded in the test periods before and after application of the LTD protocol (tetanization), which consisted of a train of eight stimuli (100 Hz), followed 120 ms after stimulus onset by a single CF stimulus. This protocol was applied at 1 Hz for 5 minutes. In WT mice, tetanization resulted in LTD (72.2 ± 2.6%; t = 41−45 min; n = 5; p = .0004) (Figure 6). In contrast, EPSC potentiation was seen in patDp/+ mice (149.7 ± 10.5%; t = 41−45 min; n = 7; p = .003; group comparison: p = .0058) (Figure 6). The reduced calcium signal on PF+CF coactivation suggests that in patDp/+ mice, the calcium signal did not reach LTD threshold (27). If true, experimental manipulation of the calcium signal amplitude should restore LTD. We bath-applied the ampakine drug CX546 (300 μM), an allosteric modulator of AMPA receptors that enhances synaptic transmission by slowing receptor desensitization (46) and in PCs enlarges dendritic calcium transients (30). In the presence of CX546, LTD was restored in patDp/+ mice (73.7 ± 5.7%, n = 6; p = .006) (Figure 6); the LTD amplitude was not different from that observed in WT mice (72.2 ± 2.6%, n = 5; p = .0004; comparison: p = .65). This observation demonstrates that the impairment of LTD in patDp/+ mice resulted from a reduction in spine calcium transients (Figure 5).

Figure 6.

PF–Purkinje cell LTD is impaired in patDp/+ mice. (A) Typical PF-induced EPSCs in wild-type and patDp/+ Purkinje cells recorded before (black traces) and 30 minutes after (colored traces) tetanization using a LTD protocol, a 1-Hz train of stimuli over 5 minutes where each stimulus consists of a PF burst of 8 pulses at 100 Hz followed by 1 climbing fiber stimulation 120 ms after the first PF pulse. Scales = 100 pA, 20 ms. (B) Time graph showing PF-EPSC mean ± SEM amplitudes monitored during baseline (0–10 min) and post-tetanization (15–45 min) periods in wild-type (n = 5) and patDp/+ (n = 7) cells. Relative to wild-type, PF-LTD was impaired in patDp/+ cells, which instead underwent long-term potentiation. In the presence of CX546, an allosteric AMPA receptor modulator, patDp/+ cells show a rescued PF-LTD (n = 6). ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .005. Average traces show mean ± SEM. All data are noted in the text and legends as mean ± SEM. EPSC, excitatory postsynaptic current; LTD, long-term depression; PF, parallel fiber.

Discussion

A key observation is that CF signals recorded from PCs are stronger in patDp/+ mice than in WT mice. This increase is seen in CF-EPSC amplitudes, spontaneous CF-evoked calcium events, and responses of individual PCs and PC populations to sensory stimuli. CF responses in PCs are compartmentalized: the complex spike is generated in the soma and is driven by the dendritic potential, but the latter is independently regulated (47,48). We will therefore consider enhanced CF signaling separately for 1) local dendritic phenotypes (LTD impairment) and 2) phenotypes that may result from an altered spike firing (49).

What is the origin of enhanced CF signaling? Mutations in genes encoding synaptic cell adhesion molecules, including neurexins, have been implicated in nonsyndromic ASD (50). The finding that NRXN1 expression is altered in patDp/+ mice, a syndromic mouse model of ASD, therefore points toward a convergence in synaptopathies that may lead to ASD-related phenotypes. NRXN1 is a synaptic organizer at CF synapses; thus, enhanced NRXN1 expression may lead to an expansion of CF input territory and the increase in CF response amplitudes (40). We did not observe an upregulation of NRXN1 protein in the molecular layer at large, a measure that would reflect changes in expression levels at PF synapses. However, a weakening of the PF input was evident from the reduction in synaptic weights and in calcium transients. An explanation for this PF signaling reduction can be found in the competitive relationship between CF and PF inputs. In the developmental competition for dendritic territory, the winner CF outcompetes weaker CF and PF inputs in a calcium-dependent manner (51). In adult rodents, a similar phenomenon was observed after lesioning the inferior olive, which causes PC denervation from the CF input and a spread of PF synapses to former CF input sites. CFs surviving incomplete lesions sprout and reinnervate PCs, pushing PF synapses out from the proximal dendrite (52). An underlying mechanism was identified in culture: δ2 glutamate receptors, which stabilize PF synapses, are internalized on calcium influx (53). It is thus possible that the emergence of strong CF synapses diminishes the PF input territory by means of enhanced calcium signaling (35).

In patDp+ mice, we do observe an impairment of LTD [but not LTP (5)]. Our confocal calcium imaging experiments show that the LTD deficit results from reduced calcium signaling at PF synapses. Thus, LTD is not saturated, as we previously concluded (5). CX546 acts as an allosteric AMPA receptor modulator at CF and PF synapses, but here it is compensating for the deficit in PF signaling. One of the motor problems observed in patDp/+ mice is impaired EBC, which may be related to LTD deregulation. LTD is only one of several plasticity types involved in the proper execution of EBC (20,21). However, its deregulation alone removes one of the mechanisms underlying proper EBC execution. While not tested here, a prediction for future experiments is that pharmacological rescue of LTD will restore EBC in patDp/+ mice. This prediction is based on the observation that genetic rescue of LTD in mGluR1−/− mice results in normal EBC (54,55). Are there nonmotor consequences of LTD deregulation (56)? Previous mouse model work could not establish a link between LTD deregulation and impaired performance in nonmotor tasks (57). An alternative view was suggested by Masao Ito in the early 1990s: cerebellar associative learning may be equally important for the construction of social behavior, thought, and language as it is for the construction of movement (58,59).

The enhanced presentation of sensory information to PC dendrites by CF synapses raises the question of whether this effect could have behavioral consequences related to CF’s error signal function. There is no change in the complex spike waveform in patDp/+ mice (5), but the observed increase in population response might well change the activation of target neurons in the cerebellar nuclei (60). Note that in patDp/+ mice, there is no PC loss (5), which could outbalance or hamper the enlarged population response. The suggestion of a cerebellar contribution to nonmotor phenotypes in ASD is not new (14,61,62). Our findings allow us to specifically address one phenotype, sensory defensiveness, which does not constitute a diagnostic criterion but is frequently observed in ASD. This phenomenon describes negative reactions to sensory stimuli, including avoidance behaviors (63), and is also observed in children diagnosed with Dup15q syndrome (documented by the Dup15q Alliance: http://dup15q.org/care/sensory/). The sensory over-responsivity that we observed in CF signaling in patDp/+ mice may cause a faulty representation of error signals, e.g., in response to corneal airpuff stimulation. Whether or not such change in cerebellar output affects cognitive processes related to sensory defensiveness we cannot conclude from our findings. However, there are reasons that make this a plausible scenario. First, manipulation of cerebellar output has been shown to impair cognitive and social behaviors (64, 65, 66). Second, in our experiments, patDp/+ mice show enhanced aversive movements on sensory stimulation, which places the observed sensory over-responsivity in context of startle-resembling behaviors. Third, clinical observations show that cerebellar diseases can lead to tactile defensiveness and sensory overload (67), establishing a link between cerebellar dysfunction and abnormal sensory processing.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

This study was supported by the Simons Foundation (Grant Nos. SFARI 203507 and SFARI 311232 [to CH]), the Brain Research Foundation (Grant No. BRF SG 2011-07 [to CH]), the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division (BSD Pilot Project Funding), and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Grant No. F31-NS095771 [to DHS]).

DHS, SEB, HKT, GG, XD, CMG, CP, and CH designed the experiments. DHS, SEB, HKT, GG, JS, XD, CW, and CP performed the experiments and analyzed the data. CH wrote the paper.

We thank Ting-Feng Lin for help with surgical procedures, Tuan Pham for help with the data analysis, and other members of the Hansel laboratory for insightful discussions.

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.09.004.

Contributor Information

Claire Piochon, Email: Claire.piochon@gmail.com.

Christian Hansel, Email: chansel@bsd.uchicago.edu.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Zoghbi H.Y. Postnatal neurodevelopmental disorders: Meeting at the synapse? Science. 2003;302:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1089071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant S.G.N. Synaptopathies: Diseases of the synaptome. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoghbi H.Y., Bear M.F. Synaptic dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders associated with autism and intellectual disabilities. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a009886. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simmons D.H., Titley H.K., Hansel C., Mason P. Behavioral tests for mouse models of autism: An argument for the inclusion of cerebellum-controlled motor behaviors. Neuroscience. 2021;462:303–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piochon C., Kloth A.D., Grasselli G., Titley H.K., Nakayama H., Hashimoto K., et al. Cerebellar plasticity and motor learning deficits in a copy-number variation mouse model of autism [published correction appears in Nat Commun 2015; 6:6014] Nat Commun. 2014;5:5586. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kloth A.D., Badura A., Li A., Cherskov A., Connolly S.G., Giovannucci A., et al. Cerebellar associative sensory learning defects in five mouse autism models. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green D., Charman T., Pickles A., Chandler S., Loucas T., Simonoff E., Baird G. Impairment in movement skills of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier K.A., Hass C.J., Naik S.K., Lodha N., Cauraugh J.H. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: A synthesis and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:1227–1240. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0981-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson B.P., Rinehart N.J., White O., Millist L., Fielding J. Saccade adaptation in autism and Asperger’s disorder. Neuroscience. 2013;243:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosconi M.W., Luna B., Kay-Stacey M., Nowinski C.V., Rubin L.H., Scudder C., et al. Saccade adaptation abnormalities implicate dysfunction of cerebellar-dependent learning mechanisms in autism spectrum disorders (ASD) PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sears L.L., Finn P.R., Steinmetz J.E. Abnormal classical eye-blink conditioning in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:737–751. doi: 10.1007/BF02172283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oristaglio J., Hyman West S., Ghaffari M., Lech M.S., Verma B.R., Harvey J.A., et al. Children with autism spectrum disorders show abnormal conditioned response timing on delay, but not trace, eyeblink conditioning. Neuroscience. 2013;248:708–718. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormick D.A., Thompson R.F. Cerebellum: Essential involvement in the classically conditioned eyelid response. Science. 1984;223:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.6701513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S.S.H., Kloth A.D., Badura A. The cerebellum, sensitive periods, and autism. Neuron. 2014;83:518–532. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fanselow M.S., Poulos A.M. The neuroscience of mammalian associative learning. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:207–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook E.H., Jr., Lindgren V., Leventhal B.L., Courchesne R., Lincoln A., Shulman C., et al. Autism or atypical autism in maternally but not paternally derived proximal 15q duplication. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:928–934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolton P.F., Dennis N.R., Browne C.E., Thomas N.S., Veltman M.W., Thompson R.J., Jacobs P. The phenotypic manifestations of interstitial duplications of proximal 15q with special reference to the autistic spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:675–685. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakatani J., Tamada K., Hatanaka F., Ise S., Ohta H., Inoue K., et al. Abnormal behavior in a chromosome-engineered mouse model for human 15q11-13 duplication seen in autism. Cell. 2009;137:1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansel C. Deregulation of synaptic plasticity in autism. Neurosci Lett. 2019;688:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansel C., Linden D.J., D’Angelo E. Beyond parallel fiber LTD: The diversity of synaptic and non-synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:467–475. doi: 10.1038/87419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao Z., van Beugen B.J., De Zeeuw C.I. Distributed synergistic plasticity and cerebellar learning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:619–635. doi: 10.1038/nrn3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schonewille M., Belmeguenai A., Koekkoek S.K., Houtman S.H., Boele H.J., van Beugen B.J., et al. Purkinje cell-specific knockout of the protein phosphatase PP2B impairs potentiation and cerebellar motor learning. Neuron. 2010;67:618–628. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boele H.J., Peter S., Ten Brinke M.M., Verdonschot L., Ijpelaar A.C.H., Rizopoulos D., et al. Impact of parallel fiber to Purkinje cell long-term depression is unmasked in absence of inhibitory input. Sci Adv. 2018;4 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aas9426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grasselli G., Boele H.J., Titley H.K., Bradford N., van Beers L., Jay L., et al. SK2 channels in cerebellar Purkinje cells contribute to excitability modulation in motor-learning-specific memory traces. PLoS Biol. 2020;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito M., Sakurai M., Tongroach P. Climbing fibre induced depression of both mossy fibre responsiveness and glutamate sensitivity of cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 1982;324:113–134. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito M., Kano M. Long-lasting depression of parallel fiber-Purkinje cell transmission induced by conjunctive stimulation of parallel fibers and climbing fibers in the cerebellar cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1982;33:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coesmans M., Weber J.T., De Zeeuw C.I., Hansel C. Bidirectional parallel fiber plasticity in the cerebellum under climbing fiber control. Neuron. 2004;44:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piochon C., Titley H.K., Simmons D.H., Grasselli G., Elgersma Y., Hansel C. Calcium threshold shift enables frequency-independent control of plasticity by an instructive signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:13221–13226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613897113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Titley H.K., Kislin M., Simmons D.H., Wang S.S.H., Hansel C. Complex spike clusters and false-positive rejection in a cerebellar supervised learning rule. J Physiol. 2019;597:4387–4406. doi: 10.1113/JP278502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Beugen B.J., Qiao X., Simmons D.H., De Zeeuw C.I., Hansel C. Enhanced AMPA receptor function promotes cerebellar long-term depression rather than potentiation. Learn Mem. 2014;21:662–667. doi: 10.1101/lm.035220.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosman L.W.J., Koekkoek S.K.E., Shapiro J., Rijken B.F.M., Zandstra F., van der Ende B., et al. Encoding of whisker input by cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 2010;588:3757–3783. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Najafi F., Giovannucci A., Wang S.S.H., Medina J.F. Sensory-driven enhancement of calcium signals in individual Purkinje cell dendrites of awake mice. Cell Rep. 2014;6:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Najafi F., Giovannucci A., Wang S.S.H., Medina J.F. Coding of stimulus strength via analog calcium signals in Purkinje cell dendrites of awake mice. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.03663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson J.I., Wylie D.R., De Zeeuw C.I. On climbing fiber signals and their consequence(s) Behav Brain Sci. 1996;19:384–398. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strata P., Rossi F. Plasticity of the olivocerebellar pathway. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:407–413. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaffield M.A., Bonnan A., Christie J.M. Conversion of graded presynaptic climbing fiber activity into graded postsynaptic Ca2+ signals by Purkinje cell dendrites. Neuron. 2019;102:762–769.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roh S.E., Kim S.H., Ryu C., Kim C.E., Kim Y.G., Worley P.F., et al. Direct translation of climbing fiber burst-mediated sensory coding into post-synaptic Purkinje cell dendritic calcium. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.61593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuda K., Miura E., Miyazaki T., Kakegawa W., Emi K., Narumi S., et al. Cbln1 is a ligand for an orphan glutamate receptor delta2, a bidirectional synapse organizer. Science. 2010;328:363–368. doi: 10.1126/science.1185152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uemura T., Lee S.J., Yasumura M., Takeuchi T., Yoshida T., Ra M., et al. Trans-synaptic interaction of GluRdelta2 and neurexin through Cbln1 mediates synapse formation in the cerebellum. Cell. 2010;141:1068–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang B., Chen L.Y., Liu X., Maxeiner S., Lee S.J., Gokce O., Südhof T.C. Neuroligins sculpt cerebellar Purkinje-cell circuits by differential control of distinct classes of synapses. Neuron. 2015;87:781–796. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L.Y., Jiang M., Zhang B., Gokce O., Südhof T.C. Conditional deletion of all neurexins defines diversity of essential synaptic organizer functions for neurexins. Neuron. 2017;94:611–625.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aiba A., Kano M., Chen C., Stanton M.E., Fox G.D., Herrup K., et al. Deficient cerebellar long-term depression and impaired motor learning in mGluR1 mutant mice. Cell. 1994;79:377–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conquet F., Bashir Z.I., Davies C.H., Daniel H., Ferraguti F., Bordi F., et al. Motor deficit and impairment of synaptic plasticity in mice lacking mGluR1. Nature. 1994;372:237–243. doi: 10.1038/372237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belmeguenai A., Botta P., Weber J.T., Carta M., De Ruiter M., De Zeeuw C.I., et al. Alcohol impairs long-term depression at the cerebellar parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:3167–3174. doi: 10.1152/jn.90384.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tempia F., Miniaci M.C., Anchisi D., Strata P. Postsynaptic current mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:520–528. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lynch G. Memory enhancement: The search for mechanism-based drugs. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(suppl):1035–1038. doi: 10.1038/nn935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davie J.T., Clark B.A., Häusser M. The origin of the complex spike in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7599–7609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0559-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtsuki G., Piochon C., Adelman J.P., Hansel C. SK2 channel modulation contributes to compartment-specific dendritic plasticity in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron. 2012;75:108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Badura A., Schonewille M., Voges K., Galliano E., Renier N., Gao Z., et al. Climbing fiber input shapes reciprocity of Purkinje cell firing. Neuron. 2013;78:700–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Südhof T.C. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455:903–911. doi: 10.1038/nature07456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ichikawa R., Hashimoto K., Miyazaki T., Uchigashima M., Yamasaki M., Aiba A., et al. Territories of heterologous inputs onto Purkinje cell dendrites are segregated by mGluR1-dependent parallel fiber synapse elimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:2282–2287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511513113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossi F., van der Want J.J., Wiklund L., Strata P. Reinnervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells by climbing fibres surviving a subtotal lesion of the inferior olive in the adult rat. II. Synaptic organization on reinnervated Purkinje cells. J Comp Neurol. 1991;308:536–554. doi: 10.1002/cne.903080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirai H. Ca2+-dependent regulation of synaptic delta2 glutamate receptor density in cultured rat Purkinje neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:73–82. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ichise T., Kano M., Hashimoto K., Yanagihara D., Nakao K., Shigemoto R., et al. mGluR1 in cerebellar Purkinje cells essential for long-term depression, synapse elimination, and motor coordination. Science. 2000;288:1832–1835. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kishimoto Y., Fujimichi R., Araishi K., Kawahara S., Kano M., Aiba A., Kirino Y. mGluR1 in cerebellar Purkinje cells is required for normal association of temporally contiguous stimuli in classical conditioning. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:2416–2424. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piochon C., Kano M., Hansel C. LTD-like molecular pathways in developmental synaptic pruning. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1299–1310. doi: 10.1038/nn.4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Galliano E., Potters J.W., Elgersma Y., Wisden W., Kushner S.A., De Zeeuw C.I., Hoebeek F.E. Synaptic transmission and plasticity at inputs to murine cerebellar Purkinje cells are largely dispensable for standard nonmotor tasks. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12599–12618. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1642-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ito M. Movement and thought: Identical control mechanisms by the cerebellum. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:448–450. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90073-u. discussion 453–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ito M. Control of mental activities by internal models in the cerebellum. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:304–313. doi: 10.1038/nrn2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Person A.L., Raman I.M. Purkinje neuron synchrony elicits time-locked spiking in the cerebellar nuclei. Nature. 2011;481:502–505. doi: 10.1038/nature10732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmahmann J.D., Sherman J.C. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain. 1998;121:561–579. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsai P.T. Autism and cerebellar dysfunction: Evidence from animal models. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;21:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Markram H., Rinaldi T., Markram K. The intense world syndrome—An alternative hypothesis for autism. Front Neurosci. 2007;1:77–96. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.1.1.006.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stoodley C.J., D’Mello A.M., Ellegood J., Jakkamsetti V., Liu P., Nebel M.B., et al. Altered cerebellar connectivity in autism and cerebellar-mediated rescue of autism-related behaviors in mice [published correction appears in Nat Neurosci 2018; 21:1016] Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1744–1751. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0004-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Badura A., Verpeut J.L., Metzger J.W., Pereira T.D., Pisano T.J., Deverett B., et al. Normal cognitive and social development require posterior cerebellar activity. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.36401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsai P.T., Hull C., Chu Y.X., Greene-Colozzi E., Sadowski A.R., Leech J.M., et al. Autistic-like behaviour and cerebellar dysfunction in Purkinje cell Tsc1 mutant mice. Nature. 2012;488:647–651. doi: 10.1038/nature11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmahmann J.D., Weilburg J.B., Sherman J.C. The neuropsychiatry of the cerebellum—Insights from the clinic. Cerebellum. 2007;6:254–267. doi: 10.1080/14734220701490995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.