Abstract

Infants at elevated likelihood of developing autism display differences in sensory reactivity, especially hyporeactivity, as early as 7 months of age, potentially contributing to a developmental cascade of autism symptoms. Caregiver responsiveness, which has been linked to positive social communication outcomes, has not been adequately examined with regard to infant sensory reactivity. This study examined the multiplicative impact of infant sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity on caregiver responsiveness to sensory reactivity and regulation cues in 43 infants at elevated likelihood of autism. Sensory hyperreactivity was found to moderate the association between sensory hyporeactivity and caregiver responsiveness, such that caregivers of infants with moderately high sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity demonstrated higher responsiveness.

Keywords: Early risk signs, Sensory reactivity, Caregiver responsiveness, Community sample

Sensory features, defined as challenges or differences in an individual’s ability to register, integrate, and respond to sensory input, are highly prevalent in children with autism (Ben-Sasson et al., 2019). Sensory features are related to responses to sensory input and commonly categorized into two main patterns: (1) sensory hyperreactivity, which involves aversive or avoidant reactions to sensory input; and (2) sensory hyporeactivity, which is characterized by delayed, attenuated, or absent responses to sensory input (Baranek et al., 2006; Ben-Sasson et al., 2009; Liss et al., 2006).

The manifestation of sensory features in children with and infants at elevated likelihood for autism is highly heterogeneous (Ausderau et al., 2014; Van Etten et al., 2017). Further, the co-occurrence of seemingly different sensory reactivity patterns, such as hypo- and hyperreactivity, has been observed in children with autism (Baranek et al., 2006; Liss et al., 2006). For example, a child may initially demonstrate sensory hyporeactivity to a stimulus, yet as the intensity of the stimulus increases, quickly shift to demonstrating sensory hyperreactivity, thereby leaving a narrow window of opportunity to engage with the stimulus. That is, an infant may demonstrate sensory hyporeactivity by failing to orient to the parent handing them another block to add to their tower. However, once the parent increases the salience of that object by tapping it on the table to draw the infant’s attention, the infant may demonstrate an aversive response consistent with sensory hyperreactivity. These co-occurring sensory reactivity patterns have been shown to negatively impact parenting stress in parents of children with autism ages 2–12 years (Ausderau et al., 2016). Children with autism are also more likely than those with other developmental challenges to show co-occurring sensory reactivity patterns (Baranek et al., 2006). There is, therefore, documented significance and a potentially multiplicative impact of co-occurring sensory reactivity patterns in children with autism on parenting stress and the potential effect of parenting stress on parent responsiveness (Steiner et al., 2018). It is important to examine the extent to which these patterns are observed in infants at elevated likelihood of later autism diagnosis and affect infants’ interactions with caregivers, which are important for developmental outcomes.

Sensory Features and Elevated Likelihood for Autism Spectrum Disorder

Sensory features, including sensory hyporeactivity, are among the earliest signs of elevated likelihood for a later diagnosis of autism, and, in particular, hyporeactivity to social stimuli may be apparent as early as 7 months of age in infant siblings of children with autism (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2015; Sacrey et al., 2015). Sensory hyperreactivity, especially to tactile stimuli, is more prominent in infant siblings (age 12 months) of children with autism who are later diagnosed with autism themselves compared to those who do not go on to have autism, and, by 24 months, these infant siblings demonstrate elevated sensory features across sensory response patterns (Wolff et al., 2019). Other research also emphasizes that sensory hyporeactivity, especially in infancy, may contribute to a developmental cascade of social-communication symptoms that ultimately lead to an autism diagnosis (Baranek et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2011; Nowell et al., 2020; Grzadzinski et al., 2020). Moreover, sensory features are known to substantially impact daily routines, family functioning, and caregiver stress in children with autism (Little et al., 2015; Ben-Sasson et al., 2013; Gourley et al., 2013; Kirby et al., 2015; Nieto et al., 2017); thus, conducting research on sensory features earlier in life will aid in the understanding of the origins and impact of sensory features on development.

Caregiver Responsiveness

Caregivers respond to a variety of intentional and unintentional infant cues and behaviors throughout daily life. A caregiver’s level of responsiveness is defined as the extent to which they provide appropriate and timely proactive and contingent behavioral responses to infant cues. This responsiveness inherently requires some aspect of observable infant behavior (e.g., vocalization, crying, pushing a toy away, or appearing to ignore a salient event) to which a caregiver can respond through words; calm, positive facial expressions; reducing or increasing the intensity of a stimulus; providing physical comfort; setting up the environment to be conducive to the child’s needs or preferences; or other types of behaviors. The response enacted by a caregiver then elicits further infant behavior, thus forming an iterative process that is influenced by factors related to both the caregiver and the infant involved in the dyad. For example, an infant may turn her head to orient toward the sound of a truck driving by outside, indicating an appropriate sensory response to this auditory stimulus. Her caregiver could respond by saying, “you hear the truck!” as a comment about their shared focus of attention. The infant might then vocalize “uck,” and the caregiver could respond, “yes, truck!” In this example, the infant’s orientation to auditory input cued the caregiver to give the child a label for an object on which the child was focusing. Then, the child repeated the label, thereby providing the caregiver with another opportunity to respond.

Caregiver responsiveness is often defined in the literature as verbal responses, or caregiver talk (Bottema-Beutel & Kim, 2021). This type of caregiver responsiveness, especially caregiver verbal responses related to the child’s focus of attention, has myriad known links to child developmental outcomes, including in infants and toddlers at elevated likelihood of developing autism or with an autism diagnosis (Edmunds et al., 2019; Grzadzinski et al., 2021; Kellerman et al., 2020). These effects have primarily been studied with regard to caregiver responsiveness to verbal and preverbal cues leading to positive social-communicative outcomes, and the observed impact on development may be due to the vital role caregiver interaction plays in an infant’s ability to engage with and learn from their environment. More specifically, caregiver responsiveness to cues signaling infants’ and toddlers’ focus of attention is more predictive of children’s receptive and expressive language outcomes than caregiver responsiveness to verbal cues in 5–36 month-olds with or at elevated likelihood for autism (Edmunds et al., 2019). However, caregiver responsiveness is complex and dependent on other factors, such as caregiver-infant engagement and infant attributes and abilities (McDuffie & Yoder, 2010; Grzadzinski et al., 2021).

Caregiver Responsiveness to Sensory Reactivity and Regulation Cues

Central to caregiver responsiveness are cues to which the caregiver is responding, including information related to infants’ sensory reactivity; that is, infants and caregivers reciprocally affect one another’s behavior in any interaction. Intentional and unintentional information about an infant’s sensory reactivity will be referred to as “cues.” For example, sensory hyporeactivity cues often present as a child appearing to ignore salient information to which most children would orient, such as a brightly colored toy placed in front of them or a caregiver excitedly calling their name. While much of the literature about caregiver responsiveness focuses on verbal or play responses (e.g., Kinard et al., 2017; Edmunds et al., 2019), the present study focuses on sensory reactivity and regulation (SRR) cues and caregiver responsiveness specifically to SRR cues (CR-SRR). Reconsider the example stated above, in which the infant and caregiver shared a verbal exchange about the truck outside the window. If the infant had demonstrated sensory hyporeactivity by not orienting to the sound of the truck, the caregiver would have to first notice the child’s lack of orienting behavior (the “cue” to which they could respond), then draw the child’s attention to the truck, then provide a label for their new mutual focus of attention (the truck). After this series of events, the truck may have already passed by the window, thereby decreasing the timeliness of the learning opportunity presented to the infant.

However, in the case of the expected sensory orienting behavior – turning to look at the truck (a much more salient “cue” for the parent than a lack of orientation) – or defensive behavior characteristic of sensory hyperreactivity (e.g., covering ears or becoming upset – an urgent cue for the parent that often demands a prompt response), the caregiver would have a more immediate opportunity to respond to the child’s cues related to their SRR. This is one example in which caregivers have a clearer opportunity to respond to their infants’ SRR when the infant displays typical sensory cues or those related to sensory hyperreactivity, as compared to an infant displaying only sensory hyporeactivity. CR-SRR differs somewhat from traditional conceptualizations of caregiver responsiveness in that CR-SRR specifically refers to the extent to which the caregiver responds to sensory-related cues from the child, including orientation; hyperreactivity (e.g., very sensitive or intense reaction); active seeking of intense or repeated sensory experiences; and hyporeactive behaviors that indicate a delay in the timing of an infant’s reaction and/or complete absence of a reaction to a very salient sensory event. Despite the potential implications of child SRR for caregiver responsiveness, no research to date has examined CR-SRR, in the form of behavioral, verbal, co-regulatory, and environmental responses.

Given the variety of caregiver and infant behaviors involved in a caregiver-infant interaction, there are many perspectives through which to examine the interplay between infant cues and caregiver responsiveness. One previous study has examined infant sensory reactivity patterns as predictors of caregiver verbal and play responsiveness in 13–16 month-olds at elevated likelihood of developing autism based on community screening results. Kinard and colleagues (2017) found that associations among sensory features and caregiver verbal and play responsiveness varied both by the infant’s sensory reactivity patterns (differing levels of sensory hypo- or hyperreactivity) and by the category of caregiver responsiveness (e.g., play actions or verbal responses related to an infant’s focus of attention). Specifically, higher levels of sensory hyporeactivity were associated with more play responses (e.g., helping the child with an action) and fewer verbal follow-in responses (e.g., commenting on a child’s action), while higher levels of sensory hyperreactivity were not significantly predictive of caregiver responsiveness in these areas (Kinard et al., 2017). However, Kinard and colleagues did not examine how co-occurrence of sensory hyper- and hyporeactivity may be associated with caregiver responsiveness, nor was caregiver responsiveness examined in direct response to the child’s sensory-related cues (e.g., CR-SRR).

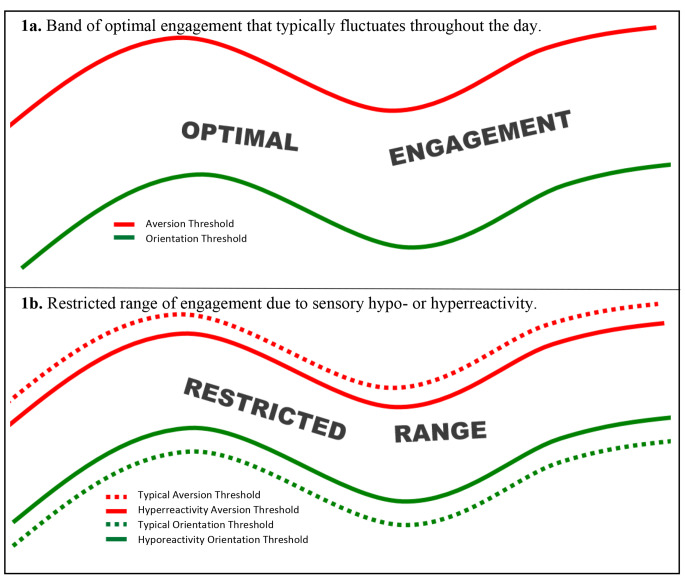

Child sensory features, which are known to be associated with caregiver stress and family activity choices (Bagby et al., 2012; Kirby et al., 2015), may increase the complexity and type of infant cues to which parents respond during parent-child interaction. In this study, the hypothesis about associations between child SRR and CR-SRR was informed by the dynamic model of sensory processing (also referred to as the optimal engagement band model) proposed by Baranek and colleagues (2001) to represent sensory experiences of children with autism. The model was adapted for this paper (Fig. 1) to illustrate the manner in which a caregiver may or may not promote the child’s engagement with a stimulus based on the child’s SRR cues. Figure 1a represents the manner in which a child’s ability to engage with sensory stimuli fluctuates throughout any given day, based on their experiences, environment, mood, and other factors. The green line is the threshold of intensity of sensory stimuli required for a child to orient to, and engage with, the stimulus, or the “orientation threshold.” The red line, the “aversion threshold,” is the threshold of intensity of sensory stimuli at which a child demonstrates an aversive response, thereby precluding further engagement with that stimulus. Between the red and green lines is the band of optimal engagement, in which a child is able to engage with and learn from the sensory input in their environment. This is a conceptual model and is not intended to be a concrete representation of any one individual’s daily sensory experiences. Figure 1b represents the restricted range of engagement available to infants with elevated likelihood of developing autism due to a higher orientation threshold (sensory hyporeactivity) and/or a lower aversion threshold (sensory hyperreactivity). In the case of sensory hyporeactivity and sensory hyperreactivity to stimuli in the same sensory modality, the model demonstrates an especially restricted range of optimal engagement. For example, a child demonstrating co-occurring moderate levels of sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity to sound may not initially orient to the relatively quiet sound of their caregiver stacking blocks, but rather would require the sound of the block tapped against a table in order to orient to that toy, which demonstrates the need for increased intensity of the auditory stimulus to reach the orientation threshold due to sensory hyporeactivity. However, they may show an aversive response, such as disengaging from the activity or covering their ears with their hands, to the loud sound of the block tapped on the table very quickly after orienting to it. This illustrates quickly reaching the aversion threshold due to co-occurring sensory hyperreactivity to auditory input. A caregiver in this example may be more quickly alerted to their child’s sensory experience due to the sudden change in behavior. By contrast, a child who only demonstrates behaviors consistent with sensory hyporeactivity, and not sensory hyperreactivity, may simply miss the caregiver’s attempt to draw attention to the toy. When a child predominantly demonstrates hyporeactivity to sensory stimuli, caregivers will arguably be less likely to recognize or respond consistently to the child’s sensory reactivity-related cues – lack of orientation to novel or salient stimuli – than they would be to recognize and respond promptly to hyperreactive responses to such stimuli. Therefore, the caregiver of a child demonstrating only sensory hyporeactivity may appear less responsive to SRR cues than the caregiver of a child demonstrating both sensory hyporeactivity and sensory hyperreactivity.

Fig. 1.

Dynamic model of sensory processing. (adapted from Baranek et al., 2001)

Purpose and Hypotheses

Given the potential associations between sensory features and CR-SRR through infant-caregiver interactions, which may be pivotal to the development of social communication skills in infants at elevated likelihood of later autism diagnosis, and the dearth of prior research in this area, the primary purpose of the present study was to examine the combined effects of varying co-occurring levels of infant sensory hyper- and hyporeactivity patterns on CR-SRR. We hypothesized that the level of sensory hyperreactivity would moderate the association between the level of sensory hyporeactivity and CR-SRR, such that sensory hyperreactivity will attenuate the negative association between sensory hyporeactivity and CR-SRR. When responding to infant cues, caregivers may have more difficulty recognizing cues related to sensory hyporeactivity than sensory hyperreactivity, because absent or attenuated expected responses are less salient than the presence of aversive responses. Perhaps they may also be less likely to respond to cues related to sensory hyporeactivity (e.g., lack of or delayed infant orientation to a sound produced by a toy), because these cues are not perceived as indicative of an imminent infant need. Because of differences in the degree to which these cues are apparent and communicate infant needs to caregivers, CR-SRR (specifically sensory hyporeactivity) may be heightened in the presence of subsequent cues related to sensory hyperreactivity.

Methods

Procedure

The current observational study utilized data from an extant community sample of infants initially determined to be at elevated likelihood of developing autism via parental responses to a screening questionnaire and subsequently recruited to participate in an intervention trial. The present study analyzed only baseline (pre-intervention) assessment data and behavioral coding of observations. Observational assessments of infant sensory reactivity as well as semi-structured interactions between infants and caregivers were conducted in a university laboratory and videotaped for later coding. Caregivers also completed questionnaires through online survey software. All study procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board, and study personnel obtained informed consent from caregivers prior to beginning study-related activities.

Participants

A total of forty-three children were identified as being at elevated likelihood of later autism diagnosis on the First Years Inventory-Lite version 3.1b (Baranek et al., 2014), a screening tool for early signs of potential autism in the first year of life. They were subsequently confirmed to demonstrate receptive and/or expressive language skills ≥ 1 SD below the mean on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995) and clinically elevated levels of sensory hyporeactivity and/or sensory hyperreactivity on the Sensory Processing Assessment (Baranek, 1999a). There were 29 males and 14 females, ranging in age from 11 to 16 months (M = 13.26 months ± 1.69 months). See Table 1 for detailed demographic information.

Table 1.

Infant demographics

| Characteristics | Statistics (N = 43) |

|---|---|

| Sex (% male) | 67.44 |

|

Race (%) White Black Asian American Indian/Alaska Native Unreported |

67.44 13.95 11.63 2.33 4.65 |

| Ethnicity (% not Hispanic or Latino) | 79.07 |

| Mean Age in Months (SD) | 13.26 (1.69) |

Measures

First Years Inventory-Lite Version 3.1b (FYIv3.1b-Lite)

The FYIv3.1b-Lite (Baranek et al., 2014) is a 25-item caregiver-report screening tool for identification of sensory regulation and social communication risk markers for later development of autism in 11-16-month-old infants. Items on the FYIv3.1b-Lite are a subset of items from the First Years Inventory version 3.1 (FYIv3.1; Baranek et al., 2013), which has a total of 69 items. The original version of the First Year Inventory (FYIv2.0; Baranek et al., 2003) was validated in several studies as a screening tool to identify 12-month-old infants in the community at elevated likelihood for eventual autism diagnosis (Ben-Sasson & Carter, 2013; Reznick et al., 2007; Turner-Brown et al., 2013; Watson et al., 2007), and showed sensitivity of 92%, and specificity of 78% for a clinical diagnosis of autism at age 3 years (Watson et al., 2007). Likewise, positive predictive value metrics indicated that a positive screen yielded 1 in 3 children that would go on to have autism, and 2 in 3 that would have a developmental condition/concerns, including autism, by 3 years of age (Turner-Brown et al., 2013). The FYIv3.1b-Lite was used to determine eligibility for the larger parent study.

Sensory Processing Assessment (SPA)

The SPA (Baranek, 1999a) is a 15–20 min semi-structured play-based assessment of sensory features for infants and children aged 6 months to 9 years. Sensory hyporeactivity and hyperreactivity are measured through behavioral observation in three areas: approach/avoidance to novel sensory toys, habituation to repeated sensory stimuli, and orientation and defensiveness to unexpected sensory stimuli. Scores for items related to sensory hyporeactivity and hyperreactivity are transformed to a five-point scale, and mean scores for each pattern of sensory reactivity are calculated from item scores across sensory modalities and social and non-social contexts. The SPA is reliable and valid for assessing sensory features in children (6 months-9 years) with and at elevated likelihood of autism (Baranek et al., 2007, 2013). This assessment was videotaped for later reliability coding. The SPA subscale scores were used as predictor variables in this study. 24% of the SPAs administered for the parent project were scored for reliability between two raters (the examiner scoring live and a second independent rater scoring from video). Two-way mixed effects, single rater, absolute agreement intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were computed and yielded moderate to good reliability, which varied across subscales (hyperreactivity ICC = 0.67; hyporeactivity ICC = 0.85). In addition, 38 out of 165 videos from the larger project were lacking scores from live examiners, and in these cases both raters coded from video and reached consensus, so these observations were not included in reliability analyses.

CR-SRR

CR-SRR was assessed through behavioral rating of video recordings of infant-caregiver interactions in four situations: (1) free play with developmentally appropriate toys; (2) an anticipation game with toys that provided a variety of sensory input; (3) a snack activity with six different food items presenting a variety of tastes, temperatures, textures, and colors; and (4) a clean-up activity with wipes, tissues, and paper towels. All interactions were video-recorded, and each situation lasted approximately five minutes. CR-SRR was assigned a score from one (unresponsive) to seven (extremely responsive) for each situation using a rating scale created for the larger parent study. The four situation scores were averaged to yield a single mean CR-SRR score for each dyad. The mean CR-SRR score was used as the outcome variable in this study. The manual for this coding scheme is available upon request. 22% of the caregiver-child interaction assessments were double-coded by two independent raters to assess inter-rater reliability. One-way absolute agreement intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated for the CR-SRR mean scores across time points in the parent study and varied by pair of raters within a moderate to good range of agreement (0.71-0.84).

Data Analyses

All data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 28.0.0. Raw data and relevant mean scores were downloaded from the Research and Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system. Descriptive statistics were first computed to characterize the sample. A linear regression model was then computed to test the moderating effect of sensory hyperreactivity on sensory hyporeactivity predicting CR-SRR. Statistical models met assumptions of linear regression and no outliers were identified via regression diagnostic procedures (i.e., histograms of data distributions, P-P plot, and scatterplot of residual values). The dependent variable was CR-SRR, and all independent variables were centered prior to analysis. We used a Johnson-Neyman region of significance calculator (Preacher, 2010–2022) in order to examine the specific levels of sensory hyperreactivity that significantly moderated the relationship between sensory hyporeactivity and CR-SRR.

Results

Descriptive Analyses and Correlations

The mean sensory hyporeactivity score in this sample was 2.29 (SD = 0.74), with a range of 1.00-4.43 on a 5-point scale. The mean sensory hyperreactivity score was 1.60 (SD = 0.37), with a range of 1.00-2.88 on the 5-point scale. Average CR-SRR across the four contexts, rated on a 7-point scale, had a mean of 3.64 (SD = 0.96), with a range of 1.75–5.75 in this sample. Neither sensory hyporeactivity nor sensory hyperreactivity was significantly correlated with CR-SRR (Pearson’s r = -.14 and 0.14, respectively).

Moderation Analysis

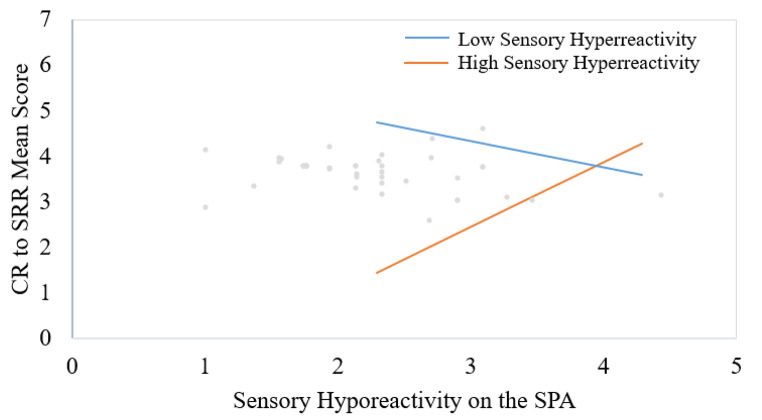

The linear regression model examined the effect of the interaction between infant sensory hyporeactivity and sensory hyperreactivity, as measured by the SPA, on CR-SRR. Sensory hyperreactivity was found to moderate the association between sensory hyporeactivity and CR-SRR (β = 0.46, SE = 0.68, p = .012). See Fig. 2, which represents the association between sensory hyporeactivity and CR-SRR moderated by sensory hyperreactivity at the lower (1.48 on a 1–5 scale) and upper (2.23 on a 1–5 scale) bounds of the region of significance. For those with sensory hyperreactivity scores between 1.48 and 2.23, the association between sensory hyporeactivity and CR-SRR is non-significant. For those above 2.23, the association is significantly positive; for those below 1.48, the association is significantly negative. These points were chosen to illustrate the moderation effect; the slopes continue to become steeper as sensory hyperreactivity scores move outside that range. See Table 2 for full regression results.

Fig. 2.

Moderation effects across the range of sensory hyporeactivity scores given sample values of sensory hyperreactivity based on the Johnson-Neyman region of significance. Higher scores on all measures represent higher levels of the variable indicated

Table 2.

Associations among sensory reactivity predictors and CR-SRR outcome

| Regression Parameters | |

|---|---|

| HYPO: β (SE) | − 0.17 (0.19) |

| HYPER: β (SE) | 0.37* (0.45) |

| HYPO x HYPER: β (SE) | 0.46* (0.68) |

| R2 | 0.18 |

| F3,39 | 2.87* |

| *p < .05 | |

| HYPO = sensory hyporeactivity; HYPER = sensory hyperreactivity | |

Discussion

Measurement of sensory features provides insight into how infants engage with daily experiences in their environment. Infants’ patterns of sensory reactivity potentially transact with caregivers’ behaviors, changing CR-SRR over time, and thus shaping infants’ future sensory experiences (McDuffie & Yoder, 2010; Grzadzinski et al., 2021). We sought to investigate how different levels of co-occurring sensory features (i.e., sensory hyporeactivity and sensory hyperreactivity) multiplicatively impact CR-SRR.

We hypothesized that the co-occurring presence of infant sensory hyporeactivity cues (e.g., missing salient information) and hyperreactivity cues (e.g., facial grimaces, turning away) would be associated with higher levels of CR-SRR due to the more salient nature of distress cues related to sensory hyperreactivity. The results of our model using observational data of infant sensory features and CR-SRR supported this hypothesis, revealing that infant sensory hyperreactivity moderated the relationship between infant sensory hyporeactivity and CR-SRR, leading to increased CR-SRR, even in the presence of moderately high infant sensory hyper- and hyporeactivity. While the range of sensory hyperreactivity scores was restricted, it was comparable to previous studies using this measure in a similar sample and context (1.0-2.3; Watson et al., 2017), suggesting that this restricted range may reflect the expected range of sensory hyperreactivity in infants at elevated likelihood of autism in a laboratory context using toys with sensory properties that are commonly experienced by infants at this age. These findings provide support for the argument that infants showing higher levels of sensory hyporeactivity may indirectly elicit more caregiver responses if they also exhibit higher levels of sensory hyperreactivity; infant cues related to the latter may present more opportunities for caregivers to respond and alter infants’ environments and sensory experiences. Increased opportunities for CR-SRR may, in turn, serve to prolong periods of engagement or prompt new initiations of caregiver-infant interactions.

This pattern of results is likely reflective of the specific type of caregiver responsiveness we examined: that which is in response to infant SRR cues. The coding scheme used to assess CR-SRR is not dependent on caregiver verbal nor communicative responses, though such responses were included in determining a rating if related to an SRR cue from the child. The coding scheme also accounted for (1) proactive set-up of the environment to allow for the child to engage in preferred sensory experiences, (2) co-regulatory responses, and (3) changes in the intensity or type of sensory stimuli available to the child in order to promote the child’s engagement with toys and with the caregiver. With this in mind, a caregiver’s lack of recognition of a child’s failure to orient to a salient stimulus was coded as a non-responsive behavior. Thus, a caregiver’s choice to move on to a new activity after the child’s sensory hyporeactivity prevented engagement in the previous activity may be reflected in lower CR-SRR ratings. However, for children demonstrating sensory hyperreactivity co-occurring with sensory hyporeactivity, SRR cues would be more emergent and salient to the caregiver, thereby promoting more immediate responses and higher CR-SRR ratings.

Limitations

This study was primarily limited by the sample size, which reduced statistical power to detect effects and precluded the inclusion of potentially meaningful covariates, such as a proxy for child’s IQ and maternal education level. Replication is an important next step to further examine these associations. Additionally, this sample has unknown autism diagnostic outcomes, as planned in-person diagnostic follow-up appointments could not take place due to COVID-19. Therefore, the associations uncovered in this study cannot be generalized outside of infants at elevated likelihood of autism based on community screening. The community sample in this study met inclusion criteria of scoring at elevated likelihood for autism or other neurodevelopmental conditions on a caregiver-report screening tool, and they exhibited below average language scores and elevated sensory scores on standardized observational measures. Additionally, the concurrent design precludes directional causal conclusions about the associations between CR-SRR and sensory response patterns. Of note, there were no children in our sample who had extreme scores on both sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity, so it is unclear how the multiplicative effects of these sensory response patterns may change in children with very high levels of co-occurring sensory features in both patterns. Future research is needed to examine the impact of co-occurring extreme sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity on CR-SRR. Future studies to determine whether explicit caregiver training to recognize – and more importantly, respond to – infant cues related to sensory hyporeactivity could bolster early intervention efforts, particularly as sensory hyporeactivity in infants is associated with later diagnosis of autism (Baranek et al., 2013).

Implications and Future Directions

As the present study was the first to examine the multiplicative effects of sensory hyporeactivity and sensory hyperreactivity on CR-SRR in a community sample of infants at elevated likelihood of developing autism, it yields several important implications for the field. First, caregiver responsiveness as a construct that is key to the development of infants at elevated likelihood of autism may need to be expanded depending on the domains of child characteristics that researchers are interested in understanding. Second, this study suggests future directions for researchers developing parent-mediated interventions for this population. Intervention strategies may need to be specifically tailored to each infant’s unique patterns of sensory reactivity in order to effectively promote CR-SRR strategies for different types of SRR cues. Finally, future research should continue to explore additive and multiplicative associations of sensory response patterns in infancy with concurrent and later developmental levels.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the research teams at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and University of Southern California for their diligent efforts in data collection, management, and coding for the larger study from which these data were drawn. The larger study was funded by National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R21HD091547).

Declarations

Disclosure statement

Several of the authors were involved in the development of the First Years Inventory-Lite version 3.1b and the Sensory Processing Assessment. Both measures are freely available, so there are no financial benefits associated with the use of these measures. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ausderau KK, Sideris J, Furlong M, Little LM, Bulluck J, Baranek GT. National survey of sensory features in children with ASD: Factor structure of the Sensory Experience Questionnaire (3.0) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44:915–925. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1945-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausderau KK, Sideris J, Little LM, Furlong M, Bulluck JC, Baranek GT. Sensory subtypes and associated outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research. 2016;9(12):1316–1327. doi: 10.1002/aur.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby MS, Dickie VA, Baranek GT. How sensory experiences of children with and without autism affect family occupations. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012;66(1):78–86. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2012.000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, Watson LR, Crais E, Reznick S. First-year inventory (FYI) 2.0. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, Boyd BA, Poe MD, David FJ, Watson LR. Hyperresponsive sensory patterns in young children with autism, developmental delay, and typical development. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2007;112(4):233–245. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[233:HSPIYC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, David FJ, Poe MD, Stone WL, Watson LR. Sensory Experiences Questionnaire: Discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(6):591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek, G. T., Reinhartsen, D. B., & Wannamaker, S. W. (2001). Play: Engaging young children with autism. Autism: A sensorimotor approach to management, 313–351

- Baranek GT, Watson LR, Boyd BA, Poe MD, David FJ, McGuire L. Hyporesponsiveness to social and nonsocial sensory stimuli in children with autism, children with developmental delays, and typically developing children. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25(2):307–320. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek, G., Watson, L., Crais, E., Turner-Brown, L., & Reznick, J. (2014). The First Years Inventory–Lite Version 3.1 b (FYI-Lite v3. 1b). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Baranek GT, Woynaroski TG, Nowell S, Turner-Brown L, DuBay M, Crais ER, Watson LR. Cascading effects of attention disengagement and sensory seeking on social symptoms in a community sample of infants at-risk for a future diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2018;29:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Carter AS. The contribution of sensory-regulatory markers to the accuracy of ASD screening at 12 months. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Soto TW, Martinez-Pedraza F, Carter AS. Early sensory over-responsivity in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders as a predictor of family impairment and parenting stress. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54(8):846–853. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Gal E, Fluss R, Katz-Zetler N, Cermak SA. Update of a meta-analysis of sensory symptoms in ASD: A new decade of research. Journal Of Autism And Developmental Disorders. 2019;49:4974–4996. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Hen L, Fluss R, Cermak SA, Engel-Yeger B, Gal E. A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottema-Beutel K, Kim SY. A systematic literature review of autism research on caregiver talk. Autism Research. 2021;14(3):432–449. doi: 10.1002/aur.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds, Kover ST, Stone WL. The relation between parent verbal responsiveness and child communication in young children with or at risk for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Research. 2019;12(5):715–731. doi: 10.1002/aur.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourley L, Wind C, Henninger EM, Chinitz S. Sensory processing difficulties, behavioral problems, and parental stress in a clinical population of young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22(7):912–921. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9650-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzadzinski R, Donovan K, Truong K, Nowell S, Lee H, Sideris J, Watson LR. Sensory reactivity at 1 and 2 years old is associated with ASD severity during the preschool years. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2020;50(11):3895–3904. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04432-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzadzinski R, Nowell SW, Crais ER, Baranek GT, Turner-Brown L, Watson LR. Parent responsiveness mediates the association between hyporeactivity at age 1 year and communication at age 2 years in children at elevated likelihood of ASD. Autism Research. 2021;14(9):2027–2037. doi: 10.1002/aur.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman AM, Schwintenberg AJ, Abu-Zhaya R, Miller M, Young GS, Ozonoff Dyadic synchrony and responsiveness in the first year: Associations with autism risk. Autism Research. 2020;13(12):2190–2201. doi: 10.1002/aur.2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinard JL, Sideris J, Watson LR, Baranek GT, Crais ER, Wakeford L, Turner-Brown L. Predictors of parent responsiveness to 1-year-olds at-risk for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47:172–186. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2944-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby AV, White TJ, Baranek GT. Caregiver strain and sensory features in children with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2015;120(1):32–45. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-120.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss M, Saulnier C, Fein D, Kinsbourne M. Sensory and attention abnormalities in autistic spectrum disorders. Autism. 2006;10(2):155–172. doi: 10.1177/1362361306062021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little LM, Ausderau K, Sideris J, Baranek GT. Activity participation and sensory features among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(9):2981–2990. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2460-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDuffie, A., & Yoder, P. (2010). Types of parent verbal responsiveness that predict language in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research: JSLHR, 53(4), 1026–1039. 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/09-0023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mullen EM. Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines, MN: AGS; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto C, Lopez B, Gandia H. Relationships between atypical sensory processing patterns, maladaptive behaviour and maternal stress in Spanish children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2017;61(12):1140–1150. doi: 10.1111/jir.12435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell SW, Watson LR, Crais ER, Baranek GT, Faldowski RA, Turner-Brown LM. Joint attention and sensory-regulatory features at 13 and 22 months as predictors of preschool language and social-communication outcomes. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2020;63(9):3100–3116. doi: 10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. (2010–2022). Interaction Utilities. Quantspy.org

- Reznick JS, Baranek GT, Reavis S, Watson LR, Crais ER. A parent-report instrument for identifying one-year-olds at risk for an eventual diagnosis of autism: The First Year Inventory. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(9):1691–1710. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0303-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacrey LR, Bennett JA, Zwaigenbaum L. Early infant development and intervention for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Neurology. 2015;30(14):1921–1929. doi: 10.1177/0883073815601500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner AM, Gengoux GW, Smith A, Chawarska K. Parent-child interaction synchrony for infants at-risk for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48:3562–3572. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Brown LM, Baranek GT, Reznick JS, Watson LR, Crais ER. The First Year Inventory: A longitudinal follow-up of 12-month-old to 3-year-old children. Autism. 2013;17(5):527–540. doi: 10.1177/1362361312439633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten HM, Kaur M, Srinivasan SM, Cohen SJ, Bhat A, Dobkins KR. Increased prevalence of unusual sensory behaviors in infants at risk for, and teens with, autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47:3431–3445. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LR, Baranek GT, Crais ER, Reznick SJ, Dykstra J, Perryman T. The First Year Inventory: Retrospective parent responses to a questionnaire designed to identify one-year-olds at risk for autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(1):49–61. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LR, Patten E, Baranek GT, Poe M, Boyd BA, Freuler A, Lorenzi J. Differential associations between sensory response patterns and language, social, and communication measures in children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2011;54(6):1562–1576. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0029). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LR, Crais ER, Baranek GT, Turner-Brown L, Sideris J, Wakeford L, Kinard J, Reznick S, Martin KL, Nowell SW. Parent-mediated intervention for one-year-olds screened as at-risk for autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47:3520–3540. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JJ, Dimian AF, Botteron KN, Dager SR, Elison JT, Estes AM, Gu H. A longitudinal study of parent-reported sensory responsiveness in toddlers at‐risk for autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2019;60(3):314–324. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Stone WL, Yirmiya N, Estes A, Hansen RL, McPartland JC, Natowicz MR, Choueiri R, Fein D, Kasari C, Pierce K, Buie T, Carter A, Davis PA, Granpeesheh D, Mailloux Z, Newschaffer C, Robins D, Roley SS, Wetherby A. Early identification of autism spectrum disorder: Recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics. 2015;136:S10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3667C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]