Abstract

The simultaneous occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the transition to adulthood have posed particular obstacles to university students’ mental health. However, it remains unclear whether hope promotes mental health in the relationship between self-compassion, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction. Therefore, this study investigated the role of hope as a mediator in the relationship between self-compassion, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction among Vietnamese undergraduate students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants consisted of 484 students (aged 18–24) from several universities in Vietnam. To measure the four variables in the research model, we opted for the Self-Compassion Scale, the State Hope Scale, the World Health Organization 5-item Well-Being Index, and the Satisfaction With Life Scale. The results showed that (1) self-compassion was significantly positively correlated with psychological well-being, (2) self-compassion was not correlated with life satisfaction, (3) hope was a mediator of the relationship between self-compassion and psychological well-being, and (4) hope was a mediator of the relationship between self-compassion and life satisfaction. These findings suggest interventions on self-compassion to enhance hope and subsequently increase students’ mental health, which offers colleges, psychologists, and psychiatrists a guideline to cope with harmful psychological implications during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Hope, Self-compassion, Psychological well-being, Life satisfaction, COVID-19

Introduction

Mental health in undergraduate students is major public health concerns globally (Dessauvagie et al., 2022). Preliminary findings have found the high prevalence of mental health problems among undergraduate students (Auerbach et al., 2016, 2018; Dessauvagie et al., 2022; Evans-Lacko & Thornicroft, 2019). Student mental health status has even worsened due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Shiratori et al., 2022). A large-scale meta-analytic study by Dragioti and colleagues (2022) also stated that COVID-19 has adversely affected mental health to a greater extent in undergraduate students in comparison with children, adolescents, and older adults. Yet, the availability of counseling services and healthcare treatment for undergraduate students at campuses is low (Dragioti et al., 2022) and minimally adequate (Auerbach et al., 2016). Thus, it is necessary to conduct studies to identify strategies that can enhance mental health among undergraduate students.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, university students have also been compelled to adopt many new behaviors including hygienic practices, online study environment, and distanced social interactions (Anderson et al., 2020). To successfully adapt to such new mode of functioning while maintaining good mental health, hope can be a protective factor (Satici et al., 2020). Hope includes positive expectations about the future (Snyder, 2000); hence, a student may hopefully expect that COVID-19 will pass and may therefore be able to better adapt to the current situation even if uncomfortable or distressful. Previous studies have demonstrated that hope is considered as a protective factor for university students’ psychological well-being in the face of COVID-19 (Lourenço et al., 2021) and that hope is associated with global life satisfaction (Stander et al., 2015). Interestingly, self-compassion (defined as compassion directed towards oneself) is positively associated with hope (Yang et al., 2016), psychological well-being (Tran et al., 2021), and life satisfaction (Arimitsu & Hofmann, 2015). When the above findings are considered as a whole, undergraduate students with higher self-compassion may display higher hope, which can be associated with higher psychological well-being and life satisfaction.

More specially, previous studies have shed light on the positive association of (1) self-compassion and psychological well-being (Saricaoglu & Arslan, 2013; Tran et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2022a,b), (2) self-compassion and life satisfaction (Li et al, 2021; Yang et al., 2016), (3) self-compassion and hope (Akin & Akin, 2014; Neff & Faso, 2015), (4) hope and psychological well-being (Kardas et al., 2019; Lourenço et al., 2021), and (5) hope and life satisfaction (O’Sullivan, 2011; Stander et al., 2015). However, no study has yet examined the relationship between self-compassion, hope, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction among undergraduate students, particularly Vietnamese undergraduate students during the third wave of COVID-19 infection.

Taken together, our study investigated the mediating role of hope in the associations between self-compassion as an independent variable and psychological well-being and life satisfaction as dependent variables. Our study not only presented new ideas for preventing mental illness among undergraduate students, but it also recommended a self-compassion program to help students cope with potential psychological problems during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Self-Compassion and Psychological Well-Being

Derived from Buddhist philosophy, self-compassion is conceptualized as “being caring and compassionate towards oneself in the face of hardship or perceived inadequacy” (Neff et al., 2007, p. 140). During times of personal failure or suffering, being compassionate towards oneself protects from being harshly judgmental, self-critical, seeing one’s failure or suffering in isolation from other humans, or over-identifying with one’s painful feelings and thoughts (Neff, 2003a). Similarly, self-compassion has been defined as having three dimensions, which are: (a) being kind and understanding toward oneself rather than being self-critical, (b) seeing one’s fallibility as part of the larger human condition and experience rather than living in isolation, and (c) holding one’s painful thoughts and feelings in mindful awareness rather than avoiding them or overidentifying with them (Barnard et al., 2011; Neff, 2003a). Accordingly, the desired outcome of self-compassion is to increase psychological well-being (i.e., the emotional factor or the human feeling aspect of the meaning of life; Kardas et al., 2019), life satisfaction (i.e., people’s perception or cognitive factor about their life; Diener, 2000), behavioral motivation, and self-regulation in terms of coping with stress during difficult times (Neff, 2003ab).

Self-compassion was used as an intervention to improve university students’ psychological well-being (Hall et al., 2013; Kyeong, 2013; Saricaoglu & Arslan, 2013; Tran et al., 2021). Chen et al. (2013) defined psychological well-being as “the fulfillment of human potential and a meaningful life” (p. 1034). Ryff’s (2014) multidimensional model proposed that psychological well-being comprises purpose in life, autonomy, personal growth, environmental mastery, positive relationships, and self-acceptance. Cross-sectional studies among university students suggest that strong correlations between many subscales of psychological well-being and self-compassion and thus among samples from Turkey (N = 636; [Saricaoglu & Arslan, 2013]), the United Kingdom (N = 182; [Hall et al., 2013]), Korea (N = 350, [Kyeong, 2013]), and Vietnam (N = 420; [Tran et al., 2021]). Since there have been a few studies on the positive association of self-compassion and psychological well-being among undergraduate students in the context of the COVID 19 pandemic, we predicted that students' self-compassion will be significantly correlated with psychological well-being during the COVID 19 pandemic.

Hypothesis 1: Self-compassion will be positively correlated with psychological well-being.

Self-Compassion and Life Satisfaction

Self-compassion has also been found to be beneficial for college students in terms of their life satisfaction (Arimitsu & Hofmann, 2015; Smeets et al., 2014). In the literature, life satisfaction is defined as the global cognitive evaluations of an individual’s quality of life according to their subjective criteria (Diener et al., 1985; Shin & Johnson, 1978). In this framework, life satisfaction is regarded as one of the significant components of subjective well-being (Diener, 1984). Cross-sectional studies among university students suggest strong correlations between life satisfaction and self-compassion and thus among samples from Japan (N = 231; [Arimitsu & Hofmann, 2015]) and Europe (N = 52; [Smeets et al., 2014]). Based on these few studies, we hypothesized that students’ self-compassion will have a significant positive correlation with life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2: Self-compassion will be positively correlated with life satisfaction.

Hope as a Mediator Between Self-Compassion and Psychological Well-Being and Self-Compassion and Life Satisfaction

Self-compassion, according to Neff (2003ab), refers to accepting one’s shortcomings or failures and showing self-kindness to oneself when coping with one’s sufferings. In college student samples, self-compassion has been linked to increased goal reengagement (Neely et al., 2009) and to the tendency to pursue new goals (Wrosch et al., 2003). Previous research has indicated correlations between self-compassion and hope (e.g., Akin & Akin, 2014; Neff & Faso, 2015; Yang et al., 2016). Indeed, self-compassion allows college students to be nonjudgmental of themselves, which aids them in identifying desired goals and then effectively increases their level of perceived hope (Sears & Kraus, 2009). Relatedly, the three facets of self-compassion (i.e., self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness) were found to be positively associated with hope in the sample of 349 university students in Turkey (Akin & Akin, 2014). Despite some research supporting the role of self-compassion in hope among undergraduate students, there has been limited attention given to the correlation between self-compassion and hope in the context of COVID-19.

On the other hand, hope is conceptualized as “a positive motivational state that is based on an interactively derived sense of successful (a) agency (goal-directed energy) and (b) pathways (planning to meet goals)” (Snyder et al., 1991, p. 287). The former refers to commitment and determination to help an individual make effort in achieving desired goals, and the latter refers to an individual’s perceived confidence to produce plausible plans to attain the desired goals (Snyder, 2002). Therefore, hope can be seen as a protective factor that promotes positive mental health (e.g., psychological well-being and life satisfaction) during difficult conditions such as the conditions created by the COVID-19 pandemic (Satici et al., 2020). Previous studies have suggested higher level of hope is associated with higher level of well-being, such as positive affect (Ciarrochi et al., 2002), and purpose in life (Stoyles et al., 2015). Conversely, a low level of hope was shown to be positively associated with mental health problems, such as psychological distress (Weis & Speridakos, 2011), and trauma-related symptoms (Weinberg et al., 2016). Several studies have suggested that hope is positively associated with university students’ psychological well-being (e.g., Kardas et al., 2019; Lourenço et al., 2021). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, hope was included in intervention programs for nursing students to enhance their psychological well-being (Lourenço et al., 2021). Cross-sectional studies among university students also suggested positive correlations between hope and psychological well-being and thus among samples from Turkey (N = 510; [Kardas et al., 2019]) and Portugal (N = 705; [Lourenço et al., 2021]). Given the results of past studies, hope may be associated with psychological well-being among Vietnamese undergraduate students during the third wave of COVID-19 infection.

Furthermore, previous studies have shown that a higher level of hope is associated with a higher level of life satisfaction (Bailey et al., 2007; O’Sullivan, 2011; Stander et al., 2015; Weis & Speridakos, 2011). Cross-sectional studies among university students suggest positive correlations between hope and life satisfaction and thus among samples from the United States (N = 332; (Bailey et al., 2007], N = 118; (O’Sullivan, 2011)), and South Africa (N = 705; (Stander et al., 2015)). Even though these studies reported the relationship between hope and life satisfaction, very few studies have been conducted to investigate such relationship in a sample of undergraduate students during the third wave of COVID-19 infection.

In the same vein, according to Snyder et al.’s hope theory (2000), hope is the belief that the way to reach one's goal can be found in trying out multiple paths. From this perspective, a hopeful individual, even under challenging life conditions, has the strength to find alternative solutions and apply them. Therefore, hope can be seen as a protective factor that promotes positive mental health (e.g., psychological well-being, life satisfaction) during difficult conditions such as the conditions created by the COVID-19 pandemic (Satici et al., 2020). According to the above arguments, we hypothesize that in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, self-compassion can be helpful in increasing hope among undergraduate students, which on its turn may increase psychological well-being and life satisfaction. We, hence, hypothesized that hope will mediate the association between self-compassion and psychological well-being and relationship between self-compassion and life satisfaction among undergraduate students.

Hypothesis 3:

Hope will play a mediating role in the relationship between self-compassion and psychological well-being.

Hypothesis 4:

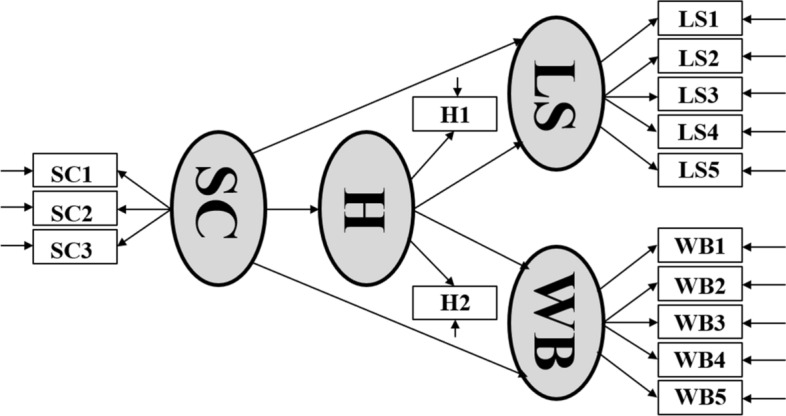

Hope will play a mediating role in the relationship between self-compassion and life satisfaction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual multiple model. Note: SC Self-compassion, H Hope, LS Life satisfaction, WB Well-being

Methodology

Participant

The study obtained approval from the research team’s university research committee (CBT-T2021-01) through the Helsinki declaration, six universities in Vietnam were randomly chosen using a cluster random sampling method. The data were collected from a sample of 484 undergraduate students (103 males, 381 females). The average age of the group was 20.24 years (SD = 1.58). There were 155 freshmen (32%), 121 sophomores (25%), 103 third-year students (21%), 68 fourth-year students (14%), 19 five-year students (3.9%), and 18 sixth-year students (3.7%). Regarding relationships, the number of participants who had a romantic partner versus being single were 112 (23.1%) and 372 (76.9%) respectively.

Procedures

Initially, the online survey contained an introduction to the study, a description of the study's objectives, an explanation of eligibility conditions, and a brief discussion of ethical research concerns through Google form. Second, we collected data via an online survey (Google Form). Third, students completed a two-part online questionnaire that includes demographic questions and measurements of self-compassion, hope, psychological well-being and life satisfaction. Finally, the participants completed all scales anonymously to guarantee the authenticity and confidentiality of their responses.

Measurements

Psychological Well-Being

The World Health Organization 5-item Well-Being Index (WHO-5; Topp et al., 2015) was used to assess well-being. The scale includes five items (e.g., "I woke up feeling fresh and rested"), and each item is rated on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 0 ("at no time") to 5 ("all of the time"). Higher scores represent higher levels of well-being. The Vietnamese version of WHO-5 has shown good validity and reliability in the Vietnamese population (Tran et al., 2021). The Cronbach's alpha in the current study is 0.93. CFA showed that the measurement model yields an adequate fit (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Goodness-of-fit indices for self-compassion, hope, psychological well-being, life satisfaction

| Variables | Chi-square/df | GFI | TLI | CFI | RMSR; 90%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-compassion | 3.45***/df = 4 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.96 | .07; 90%CI [0.05;0.90] |

| Hope | 4.45***/df = 4 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | .08; 90%CI [0.05;0.13] |

| Life satisfaction | 2.70***/df = 5 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | .06; 90%CI [0.02;0.10] |

| Psychological well-being | 1.34***/df = 4 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | .03; 90%CI [0.00;0.08] |

***p < .001

Self-Compassion

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003b) was used to measure students’ perceptions of self-compassion. This scale includes three components: self-kindness (5 items; e.g., I try to be loving towards myself when I’m feeling emotional pain), mindfulness (4 items; e.g., When something upsets me I try to keep my emotions in balance), and common humanity (4 items; e.g., When things are going badly for me, I see the difficulties as part of life that everyone goes through). In addition, items are rated on a scale of 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Higher scores mean a higher level of self-compassion. The Vietnamese version of SCS has shown good validity and reliability in the Vietnamese population (Nguyen et al., 2020). The current study reported Cronbach's alpha of 0.83. CFA showed that the measurement model yields an adequate fit (see Table 1).

Hope

The State Hope Scale (SHS; Snyder et al., 1996) was administered to assess the hope level of the participants. Participants were asked to rate on an 8-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (definitely false) to 8 (definitely true). This scale is made up of two subscales, including the agency (3 items; e.g., "At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals") and the pathways (3 items, e.g., "I can think of many ways to reach my current goals"). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale in this study was 0.93. The State Hope Scale was used following double translation. The English version was initially translated into Vietnamese by a Vietnamese native speaker who is fluent in English. The Vietnamese version was then sent to an English native professional who is fluent in Vietnamese for a back-translation. Finally, the research group compared the two versions (the English-translated version and the Vietnamese back-translated version) to the original version for accuracy and discrepancies in the content. CFA showed that the measurement model satisfies an adequate fit (see Table 1).

Life Satisfaction

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) was employed to assess life satisfaction of the participants. The scale used five items (e.g., "So far I have gotten the important things I want in life") that are rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Higher overall score indicates a higher level of life satisfaction, and vice versa. The Vietnamese version of SWLS showed good validity in the Vietnamese population (Phuoc & Nguyen, 2020). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.90 in the current study. CFA showed that the measurement model has an adequate fit (see Table 1).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 24 software with the variables of interest for the total sample. First, we conducted mean, standardized, and correlations between the main variables (i.e., self-compassion, hope, psychological well-being and life satisfaction). Second, a structural method was assessed using a two-step approach advocated by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), consisting of (a) a measurement model with all the latent constructs, observed indicators, and error terms of the explanatory and outcome variables via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 24; and (b) a structural model with the predicted pattern of associations among latent constructs via structural equation modeling using AMOS 24.Third, the measurement models with the most representative models were first tested to assess the extent to which the latent variables were well represented by the observed indicators of each structural model. Then, six structural models were tested. Model 1: Self-compassion is independent, hope is a mediator variable, and psychological well-being is dependent. Model 2: self-compassion is independent, and hope is a mediator variable, predicting life satisfaction. Model 3: self-compassion is independent, and hope is a mediator, predicting life satisfaction and psychological well-being. Model 4: Psychological well-being and life satisfaction are independent, hope is a mediator, and self-compassion is dependent. Model 5: Hope is dependent on psychological well-being, life satisfaction is independent, and self-compassion is the mediator. Model 6: Hope is independent; life satisfaction and psychological well-being are mediators in presenting self-compassion. In the next step, we checked whether the model which best fit the data was better. We chose model 3 as the model fit was better than the other models to analyze the relationship between self-compassion, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being; a mediation was performed with the independent variable, hope as a mediator, and life satisfaction and psychological well-being as the dependent variables. Finally, according to Hu & Bentler (1999), the following indices were used to evaluate the model fit: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.95, and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.95, root means a square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, which implied that the model fit was achieved acceptable.

Measurement Model

The measurement model was tested, including latent constructs for self-compassion (SE), hope (H), life satisfaction (LS), and psychological well-being (WB). In which, the latent SE variable was indicated by mindfulness, self-kindness, and common humanity. The latent hope was indicated by agency and pathways. The psychological-well-being latent variable was indicated by the five statements (e.g., My daily life has been filled with things that interest me). The latent life satisfaction variable was indicated by the five items (e.g., “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal”). Finally, after defining the latent construct, the measurement model fitted the observed data well: χ2 (2.86, N = 484) = 239.951 (p < 0.001); CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.06 90% CI = (0.05, 0.07).

Results

Common Method Bias Test

Common Method Bias was used to test the data collection. Harman's single-factor test was conducted to test common method bias. Our findings revealed that the first factor accounted for about 30.21 percent of the variation, which was significantly lower than the crucial threshold of 40% (Aguirre-Urreta et al., 2019), suggesting that common method bias was not noticeable. In addition, according to Kock (2015), a thorough collinearity evaluation test was undertaken as an additional statistical remedy for common technique bias. All variance inflation factor values ranging from 1.20 to 1.75 were significantly less than 2, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern in this study (Kock, 2015).

Descriptive Statistics Among the Variables

Descriptive statistics in Table 2 included the means, standard deviations, and the correlations between self-compassion (SC), hope (H), Life satisfaction (LS), and psychological well-being (WB). SC was significantly positively correlated with H, L, and WB (0.47 to 0.70, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SC | 10.40 | 2.00 | 1 | |||

| 2. LS | 19.66 | 6.80 | .47** | 1 | ||

| 3. WB | 9.65 | 5.53 | .52** | .65** | 1 | |

| 4. H | 26.96 | 9.73 | .58** | .70** | .69** | 1 |

SC Self-compassion, H Hope, LS Life satisfaction, WB Well-being

**p < .01; *p < 0.05

Structural Model

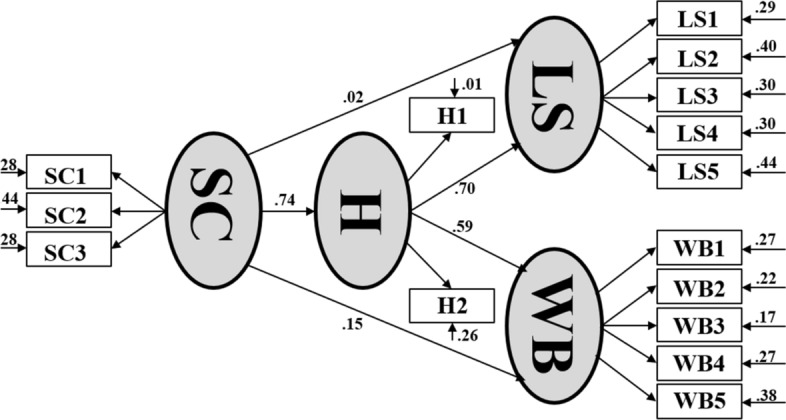

One potential mediator, hope (H) was entered into a mediation model to examine whether they mediated the link between self-compassion (SC), psychological well-being (WB) and life satisfaction (LS) in the Vietnamese students. We tested the hypothesized model that entailed three structural models. Particularly, in Model 1, H was considered as a mediator in the relationship SC and WB (see Table 3). In Model 2, H was considered as a mediator between SC and LS (see Table 3). Model 3 was used to analyze the relations between the test of the hypothesized total mediator model, which showed an excellent data fit (χ2 = 261.39, df = 85; GFI = 0.93, CFI = 0.097; TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.07; 95%CI = (0.06;0.08)). First, SC significantly correlated with WB (β = 0.15, p < 0.05, 95% CI = (0.03, 0.26), supporting hypothesis 1. However, SC was not significantly correlated with LS (β = 0.02, p = 0.76, 95% CI = (-0.09, 0.13)), rejecting hypothesis 2. Second, the path coefficients showed the indirect effects of H on the association between SC and LS (β = 0.44, p < 0.01, 95% CI = (0.36, 0.53), SC and WB (β = 0.52, p < 0.01, 95% CI = (0.43, 0.61), so hypotheses 3, 4 were supported. Third, we subsequently used the model constraint command of AMOS to create auxiliary variables and used bootstrapping in order to compare the mediation effects (Fig. 2, Table 4). Third, the indirect correlation of SC with WB via H was significantly stronger than the correlation of SC with LS via H (β = 0.08, p < 0.05, 95% CI = (0.01, 0.15)). Finally, we examined three alternative models to determine the best fit. These alternative models were constructed by examining the relationships between the study variables (see Table 3). The first alternative model (Model 4) was tested with psychological well-being and life satisfaction as independents, hope as a mediator, and self-compassion as a dependent (Model 4; see Table 3). A second alternative model was tested with hope as a dependent and self-compassion as the mediator variable, and psychological well-being and life satisfaction was independent (Model 5; see Table 3). A third alternative model with hope was independent; both variables of life satisfaction and psychological well-being were mediators in presenting self-compassion (Model 6; see Table 3). Nevertheless, when the outcomes of the above models 4,5,6 were compared, we observed that Model 3 offers the best fit. Thus, we have chosen model 3, which has indicated that hope partially mediated the relationship between self-compassion and life satisfaction and psychological well-being.

Table 3.

Model fit information of multiple mediation effects

| Variables | Chi-square/df | GFI | TLI | CFI | RMSR; 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (WB) | 2.48***/ df = 116 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.04; 95%CI [0.03;0.05] |

| Model 2 (LS) | 3.25***/ df = 32 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.07;95%CI [0.05;0.08] |

| Model 3 | 3.07***/df = 85 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.07; 95%CI [0.06;0.08] |

| Model 4 | 7.76***/df = 85 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.12;95%CI [0.110;1.3] |

| Model 5 | 4.3***/df = 85 | 0.80 | 0.09 | 0.95 | 0.08;95%CI [0.74;0.91] |

| Model 6 | 3.12***/df = 85 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.07;95%CI [0.06;0.08] |

***p < .001; LS Life satisfaction; WB: Psychological well-being. Model 1: Self-compassion is independent, hope is a mediator variable, and psychological well-being is dependent. Model 2: self-compassion is independent, hope is a mediator variable, predicting life satisfaction. Model 3: self-compassion is independent, hope is a mediator, predicting life satisfaction and psychological well-being. Model 4: Psychological well-being and life satisfaction are independents, hope is a mediator, and self-compassion is dependent. Model 5: Hope is dependent on psychological well-being, life satisfaction is independent, and self-compassion is the mediator. Model 6: Hope is independent, life satisfaction, psychological well-being are mediators in presenting self-compassion

Fig. 2.

The result of multiple mediational models. Note: p < .01. SC Self-compassion, H Hope, LS Life satisfaction, WB Psychological well-being, unstandardized estimates

Table 4.

The direct, indirect effects of perceptions of self-compassion on life satisfaction and psychological well-being

| Variables | Point estimate | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Direct effect | |||

| SC → H | .74 | .66 | .82 |

| H → LS | .70 | .61 | .80 |

| H → WB | .59 | .50 | 70 |

| SC → LS | .02 | -.09 | .13 |

| SC → WB | .15 | .03 | .26 |

| Indirect effect | |||

| SC → H → WB | .52 | .43 | .61 |

| SC → H → LS | .44 | .36 | .53 |

SC Self-compassion, H Hope, LS Life satisfaction, WB Psychological-well being, unstandardized estimates

Self-Compassion Direct Impacts on Psychological Well-Being, not on Life Satisfaction

The present study formulated a mediation model to examine the relationship between self-compassion, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction in the context of the COVID pandemic. As previously noted, there was a strong association between self-compassion and psychological well-being (supporting hypothesis 1). This finding is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Hall et al., 2013; Kyeong, 2013; Marsh et al., 2018; Saricaoglu & Arslan, 2013; Trang et al., 2021). Based on the findings of this study, a high level of self-compassionmay help university students relieve psychological problems that were caused by COVID-19 and promote positive psychological well-being. Previous studies have shown that people with high levels of self-esteem experience lower levels of COVID-19 fear regardless of age (Deniz, 2021; Nguyen & Le, 2021). Especially, the results of a survey of 182 university students showed that individuals with higher levels of self-compassion were better able to cope effectively with negative life events. The reason is that self-kindness and mindfulness components of self-compassion increase their ability to cognitively engage in positive coping strategies in response to unpleasant or distressing events (Hall et al., 2013). Thus, self-compassion is considered a factor that directly affects the psychological health of students.

On the other hand, our findings revealed that self-compassion is positively related with life satisfaction. However, when hope was included in the study model as a mediator variable, the direct effect of self-compassion on life satisfaction was not significant (rejecting hypothesis 2). As a result, the direct impact of self-compassion on life satisfaction remains challenging with inconsistent outcomes. Our findings agreed with the study of Yang et al. (2016) which revealed that life satisfaction is not directly influenced by self-compassion. Conversely, other studies found a significantly positive correlation between self-compassion and life satisfaction (Arimitsu & Hofmann, 2015; Smeets et al., 2014).

Based on the findings from this study,self-compassion had a direct impact on psychological well-being while self-compassion did not directly affect life satisfaction. Hence, further research is warranted regarding the direct influence of self-compassion on life satisfaction and psychological well-being.

The Mediating Role of Hope

Consistent with hypotheses 3 and 4, results indicated that hope is a mediator in the relationships between self-compassion and life satisfaction as well as self-compassion and psychological well-being. In other words, students with higher self-compassion levels are more likely to have higher hope and end up with higher levels of life satisfaction and psychological well-being (Hope et al, 2014).

First, this finding indicated that self-compassion is positively correlated with hope, which is consistent with other previous studies (Akin & Akin, 2014; Neff & Faso, 2015; Yang et al., 2016). In interpreting the relationship between self-compassion and hope, there are some plausible explanations. For example, self-compassion may increase a nonjudgmental attitude, which facilitates identifying desired life goals (e.g., protecting oneself and loved ones from COVID-19) and increasing perceived confidence in formulating alternative pathways in response to these goals (e.g., immunization, social distancing, always wearing a mask, being careful during interpersonal interactions) (Sears & Kraus, 2009). In addition, an individual with higher levels of self-compassion is less likely to ruminate about possible negative implications when dealing with negative life events (Leary et al., 2007). They seem to use more adaptive strategies which render them more likely to strive for desired goals, produce greater persistence, and sustain greater motivation toward goals even during challenging times such as the Covid-19 pandemic (Neff et al., 2005).

Second, this study also showed that hope is strongly associated with psychological well-being in Vietnamese students during the context of COVID-19 pandemic, which is in line with previous findings (Kardas et al., 2019; Lourenço et al., 2021). According to Snyder (2002), individuals with a high level of hope have a tendency to find motivations for goal pursuits and select appropriate strategies to reach their goals. Therefore, hope can meaningfully contribute to the achievement of students’ life goals and thus may increase their psychological well-being (Kardas et al., 2019). These findings concur with our hypothesis suggesting that hope can be a significant mediator between self-compassion and psychological well-being (supports hypothesis 3).

Third, the study demonstrated that hope is positively correlated with life satisfaction, which is consistent with previous studies among university students (Bailey et al., 2007; Marques et al., 2013; O’Sullivan, 2011; Stander et al., 2015). This might be because individuals with high hope may have cognitive strategies that are effective or flexible in pursuit of a given goal (e.g., protecting themselves and loved ones from COVID-19) (Sears & Kraus, 2009). Such effective strategies may help them achieve motivation to initiate and sustain goal-directed thinking and behaviors (MacLeod et al., 2008; Snyder et al., 1991), which may lead to the achievement of goals and therefore more life satisfaction (Marques et al., 2013). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, an individual who is hopeful with their ability to cope can show lower levels of anxiety and depression, which may therefore report higher life satisfaction (Satici et al., 2020). Based on the research evidence and theory above, these findings agree our hypothesis suggesting that hope can play the role of a mediator between self-compassion and psychological well-being, and self-compassion and life satisfaction (supports hypothesis 4).

To sum up, results suggest that self-compassion indirectly affects psychological well-being and life satisfaction through hope. This may explain the vital role of hope in enhancing self-compassion to increase students' mental health (e.g., psychological well-being, life satisfaction) in the Vietnamese universities during the timely COVID 19 pandemic outbreak.

Limitations and Contributions

Few limitations of our study should be noted. First, the results were based on an online self reported survey, which might be susceptible to bias (e.g., social desirability). Thus, self-report should be combined with additional methods to gain a multifaceted understanding of variables. Second, the participants in our study were undergraduate students in Vietnam, which limits the generalizability of the present findings. Future studies should reexamine the findings in other age groups and in other cultures. Third, the cross-sectional research design was adopted, which limits our ability to evaluate the causal connections between self-compassion, hope, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction. Future longitudinal and experimental research is needed to re-examine our findings and determine causal relationships among these variables.

Despite the limitations mentioned above, the current study provides empirical evidence that hope mediates the link between self-compassion, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being. The study also has several implications for practitioners and educators to implement self-compassion programs in educational settings (e.g., Huang et al., 2021). In addition, mental health professionals may need to assess students' hope and aim to improve it by adopting positive psychological interventions or therapies, such as Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (CBT) (e.g., Pouyanfard et al., 2020) and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (e.g., Shapiro et al., 2011). Furthermore, these results suggest that setting up goals, staying hopeful in achieving goals, and developing strategies to meet goals may enhance students’ mental health throughout the difficult time of the pandemic.

Author’s Contribution

Supervision: BK, MAQT. Editing manuscript: BK, MAQT, NNTC, MVP. MAQT designed the study, analyzed the data, wrote the introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections. NNTC, ATND, TVN, TTN, TMT, MVP contributed to the introduction, and discussion sections. Data Collection: MAQT, ATND, TVN, TTN, TMT, AKLD.

Data Availability

Datasets related to this article can be found at https://forms.gle/FAMXJbtu8bWFywYa8, an open-source online data repository hosted at Google drive Data (Minh Anh Quang Tran, 2021).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants followed the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Minh Anh Quang Tran, Email: minhcaorong@gmail.com.

Bassam Khoury, Email: bassam.el-khoury@mcgill.ca.

Nguyen Ngoc Thao Chau, Email: nguyencnt@uel.edu.vn.

Manh Van Pham, Email: manh.vanpham11@gmail.com.

An Thien Nguyen Dang, Email: dangnguyenthienan.psy@gmail.com.

Tai Vinh Ngo, Email: ngotai210@gmail.com.

Thuy Thi Ngo, Email: ngothuyfos.ussh97@gmail.com.

Trang Mai Truong, Email: truongmaitrang.psyussh@gmail.com.

Anh Khuong Le Dao, Email: khuongle.md09@nycu.edu.tw.

References

- Aguirre-Urreta MI, Hu J. Detecting common method bias: Performance of the Harman's single-factor test. ACM SIGMIS Database: THe DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems. 2019;50(2):45–70. doi: 10.1145/3330472.3330477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C.-Y., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction,1–9,. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Akin A, Akin U. An investigation of the predictive role of self-compassion on hope in Turkish university students. Journal of Educational Sciences and Psychology. 2014;4(2):96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimitsu K, Hofmann SG. Cognitions as mediators in the relationship between self-compassion and affect. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;74:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Axinn WG, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Green JG, Mortier P. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46(14):2955–2970. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., . . . Hasking, P. (2018). WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of abnormal psychology, 127(7), 623. 10.1037/abn0000362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bailey TC, Eng W, Frisch MB, Snyder C. Hope and optimism are related to life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2007;2(3):168–175. doi: 10.1080/17439760701409546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard LK, Curry JF. Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology. 2011;15(4):289–303. doi: 10.1037/a0025754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FF, Jing Y, Hayes A, Lee JM. Two concepts or two approaches? A bifactor analysis of psychological and subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2013;14(3):1033–1068. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9367-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Deane FP, Anderson S. Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32(2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00012-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deniz, M. E. (2021, Jul). Self-compassion, intolerance of uncertainty, fear of COVID-19, and well-being: A serial mediation investigation. Pers Individ Dif, 177, 110824. 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dessauvagie, A. S., Dang, H.-M., Nguyen, T. A. T., & Groen, G. (2022). Mental health of university students in southeastern asia: a systematic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 34(2–3), 172–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [PubMed]

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American psychologist, 55(1), 34. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34 [PubMed]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragioti E, Li H, Tsitsas G, Lee KH, Choi J, Kim J, Agorastos A. A large-scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 early pandemic. Journal of Medical Virology. 2022;94(5):1935–1949. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student initiative: Implementation issues in low-and middle-income countries. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2019;28(2):e1756. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ. The Oxford handbook of hope. Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hall CW, Row KA, Wuensch KL, Godley KR. The role of self-compassion in physical and psychological well-being. The Journal of Psychology. 2013;147(4):311–323. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.693138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope N, Koestner R, Milyavskaya M. The role of self-compassion in goal pursuit and well-being among university freshmen. Self and Identity. 2014;13(5):579–593. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2014.889032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Lin K, Fan L, Qiao S, Wang Y. The effects of a self-compassion intervention on future-oriented coping and psychological well-being: A randomized controlled trial in Chinese college students. Mindfulness. 2021;12(6):1451–1458. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01614-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, t., & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kardas, F., Zekeriya, C., Eskisu, M., & Gelibolu, S. (2019). Gratitude, hope, optimism and life satisfaction as predictors of psychological well-being. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 19(82), 81–100. 10.14689/ejer.2019.82.5

- Kim C, Ko H. The impact of self-compassion on mental health, sleep, quality of life and life satisfaction among older adults. Geriatric Nursing. 2018;39(6):623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kock N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (ijec) 2015;11(4):1–10. doi: 10.4018/ijec.2015100101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyeong LW. Self-compassion as a moderator of the relationship between academic burn-out and psychological health in Korean cyber university students. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;54(8):899–902. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: the implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li A, Wang S, Cai M, Sun R, Liu X. Self-compassion and life-satisfaction among Chinese self-quarantined residents during COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation model of positive coping and gender. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;170:110457. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long KN, Kim ES, Chen Y, Wilson MF, Worthington EL, Jr, VanderWeele TJ. The role of Hope in subsequent health and well-being for older adults: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. Global Epidemiology. 2020;2:100018. doi: 10.1016/j.gloepi.2020.100018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, T. M. G., Charepe, Z. B., Pestana, C. B., & d. C. F., Rabiais, I. C. M., Alvarez, E. J. S., Figueiredo, R. M. S. A., & Fernandes, S. J. D. (2021). Hope and Psychological Well-Being during the Sanitary Crisis by COVID-19: A Study with Nursing Students. Escola Anna Nery,25,. 10.1590/2177-9465-EAN-2020-0548

- MacLeod AK, Coates E, Hetherton J. Increasing well-being through teaching goal-setting and planning skills: Results of a brief intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;9(2):185–196. doi: 10.1007/s10902-007-9057-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marques SC, Lopez SJ, Mitchell J. The Role of Hope, Spirituality and Religious Practice in Adolescents’ Life Satisfaction: Longitudinal Findings. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2013;14(1):251–261. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9329-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh IC, Chan SW, MacBeth A. Self-compassion and psychological distress in adolescents—a meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2018;9(4):1011–1027. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0850-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely ME, Schallert DL, Mohammed SS, Roberts RM, Chen Y. Self-kindness when facing stress: The role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students well-being. Motivation and Emotion. 2009;33:88–97. doi: 10.1007/s11031-008-9119-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003;2(2):85–101. doi: 10.1080/15298860309032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2(3):223–250. doi: 10.1080/15298860309027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness. 2016;7(1):264–274. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0479-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Faso DJ. Self-compassion and well-being in parents of children with autism. Mindfulness. 2015;6(4):938–947. doi: 10.1007/s12671-014-0359-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Hsieh Y-P, Dejitterat K. Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and Identity. 2005;4(3):263–287. doi: 10.1080/13576500444000317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Kirkpatrick KL, Rude SS. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(1):139–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Vonk R. Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality. 2009;77(1):23–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. M., Bui, T. T. H., Xiao, X., & Le, V. H. (2020). The influence of self-compassion on mindful parenting: A mediation model of gratitude. The Family Journal, 28, 455–462. 10. 1177/ 10664 80720 950421

- Nguyen, T. M., & Le, G. N. H. (2021). The influence of COVID-19 stress on psychological well-being among Vietnamese adults: The role of self-compassion and gratitude. Traumatology, 27, 86–97. 10. 1037/ trm00 00295

- O’Sullivan G. The relationship between hope, eustress, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction among undergraduates. Social Indicators Research. 2011;101(1):155–172. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9662-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phuoc CTNN, Nguyen QAN. Self-Compassion and Well-being among Vietnamese Adolescents. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2020;20(3):327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Pouyanfard S, Mohammadpour M, ParviziFard AA, Sadeghi K. Effectiveness of mindfulness-integrated cognitive behavior therapy on anxiety, depression and hope in multiple sclerosis patients: A randomized clinical trial. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2020;42:55–63. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2020-4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. 10.1159/000353263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Saricaoglu, H., & Arslan, C. (2013). An investigation into psychological well-being levels of higher education students with respect to personality traits and self-compassion. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 13(4), 2097–2104. 10.12738/estp.2013.4.1740

- Satici, S. A., Kayis, A. R., Satici, B., Griffiths, M. D., & Can, G. (2020). Resilience, hope, and subjective happiness among the turkish population: Fear of COVID-19 as a mediator. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction,1–16,. 10.1007/s11469-020-00443-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sears S, Kraus S. I think therefore I om: Cognitive distortions and coping style as mediators for the effects of mindfulness meditation on anxiety, positive and negative affect, and hope. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(6):561–573. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Brown KW, Thoresen C, Plante TG. The moderation of mindfulness-based stress reduction effects by trait mindfulness: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67(3):267–277. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DC, Johnson DM. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research. 1978;5(1):475–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00352944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiratori Y, Ogawa T, Ota M, Sodeyama N, Sakamoto T, Arai T, Tachikawa H. A longitudinal comparison of college student mental health under the COVID-19 self-restraint policy in Japan. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2022;8:100314. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets E, Neff K, Alberts H, Peters M. Meeting suffering with kindness: Effects of a brief self-compassion intervention for female college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;70(9):794–807. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R. (2000). Handbook of hope: Theory, measures, and applications. Academic press.

- Snyder CR. Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13(4):249–275. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R., Irving, L. M., & Anderson, J. R. (1991). Hope and health. Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The health perspective. In Snyder, C. R. & Forsyth, D. R. (Eds.), Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The Health Perspective (pp. 285–305). Pergamon Press

- Snyder CR, Rand K, Sigmon D. Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family. In: Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Hope. Oxford University Press; 2017. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S. C., Ybasco, F. C., Borders, T. F., Babyak, M. A., & Higgins, R. L. (1996). Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of personality and social psychology, 70(2), 321. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.321 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stander FW, Diedericks E, Mostert K, De Beer LT. Proactive behavior towards strength use and deficit improvement, hope and efficacy as predictors of life satisfaction amongst first-year university students. Journal of Industrial Psychology. 2015;41(1):1–10. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v41i1.1248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyles G, Chadwick A, Caputi P. Purpose in life and well-being: The relationship between purpose in life, hope, coping, and inward sensitivity among first-year university students. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health. 2015;17(2):119–134. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2015.985558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2015;84(3):167–176. doi: 10.1159/000376585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran MAQ, Pham MV, Truong TM, Le GNH, Nguyen GAS. Self-compassion and students’ well-being among Vietnamese students: Chain mediation effect of narcissism and anxiety. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10942-021-00431-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tran MAQ, Vo-Thanh T, Soliman M, Ha AT, Van Pham M. Could mindfulness diminish mental health disorders? The serial mediating role of self-compassion and psychological well-being. Current Psychology. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03421-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran MAQ, Vo-Thanh T, Soliman M, Khoury B, Chau NNT. Self-compassion, mindfulness, stress, and self-esteem among Vietnamese university students: Psychological well-being and positive emotion as mediators. Mindfulness. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12671-022-01980-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2020a). COVID-19 impact on education.https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

- UNESCO. (2020b). Nurturing the social and emotional wellbeing of children and young people during crises.https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373271

- Weinberg M, Besser A, Zeigler-Hill V, Neria Y. Bidirectional associations between hope, optimism and social support, and trauma-related symptoms among survivors of terrorism and their spouses. Journal of Research in Personality. 2016;62:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weis R, Speridakos EC. A meta-analysis of hope enhancement strategies in clinical and community settings. Psychology of Well-Being: Theory, Research and Practice. 2011;1(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/2211-1522-1-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Miller, G. E., Schulz, R., & Carver, C. S. (2003). Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: Goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,29(12), 1494–1508. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang Y, Zhang M, Kou Y. Self-compassion and life satisfaction: The mediating role of hope. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;98:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets related to this article can be found at https://forms.gle/FAMXJbtu8bWFywYa8, an open-source online data repository hosted at Google drive Data (Minh Anh Quang Tran, 2021).