Abstract

Objectives

To assess the attitude of healthcare providers (HCPs) towards the delivering of pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and identify factors and barriers that might influence referral.

Design

A cross-sectional online survey consisting of nine multiple-choice questions.

Settings

Saudi Arabia.

Participants

980 HCPs including nurses, respiratory therapists (RT) and physiotherapists.

Primary outcome measures

HCPs attitudes towards and expectations of the delivery of PR to COPD patients and the identification of factors and barriers that might influence referral in Saudi Arabia.

Results

Overall, 980 HCPs, 53.1% of whom were men, completed the survey. Nurses accounted for 40.1% of the total sample size, and RTs and physiotherapists accounted for 32.1% and 16.5%, respectively. The majority of HCPs strongly agreed that PR would improve exercise capacity 589 (60.1%), health-related quality of life 571 (58.3%), and disease self-management in patients with COPD 589 (60.1%). Moreover, the in-hospital supervised PR programme was the preferred method of delivering PR, according to 374 (38.16%) HCPs. Around 85% of HCPs perceived information about COPD, followed by smoking cessation 787 (80.3%) as essential components of PR besides the exercise component. The most common patient-related factor that strongly influenced referral decisions was ‘mobility affected by breathlessness’ (64%), while the ‘availability of PR centres’ (61%), the ‘lack of trained HCPs’ (52%) and the ‘lack of authority to refer patients’ (44%) were the most common barriers to referral.

Conclusion

PR is perceived as an effective management strategy for patients with COPD. A supervised hospital-based programme is the preferred method of delivering PR, with information about COPD and smoking cessation considered essential components of PR besides the exercise component. A lack of PR centres, well-trained staff and the authority to refer patients were major barriers to referring patients with COPD. Further research is needed to confirm HCP perceptions of patient-related barriers.

Keywords: REHABILITATION MEDICINE, RESPIRATORY MEDICINE (see Thoracic Medicine), Chronic airways disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first national study that explores healthcare providers’ (HCPs’) attitudes and beliefs about the delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and identifies factors and barriers that might influence referral in Saudi Arabia

The availability of PR centres, the lack of trained HCPs and the lack of authority to refer patients were the most common barriers preventing the referral of COPD patients to PR programme

The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted the respondents’ opinions.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable and treatable disease characterised by airway and/or alveolar abnormalities, leading to airflow limitation and persistent pulmonary symptoms.1 Patients with COPD are susceptible to daily respiratory symptoms, reduced exercise capacity and frequent chest infections that could result in deterioration of lung function and acceleration of disease progression, subsequently leading to emergency hospital admissions.1 2 In addition to pharmacologic approaches, the International Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease stresses the importance of including non-pharmacologic interventions such as pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) in the management of COPD symptoms as PR provides symptomatic improvement,3 4 thereby reducing unnecessary hospital admissions.

PR is a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, non-pharmacologic intervention aimed at improving quality of life and exercise performance in patients with COPD.4–6 PR usually consists of patient assessment with an exercise test and dyspnoea assessment, exercise training that includes endurance and resistance training, quality of life measure, nutritional with occupational evaluation and health education and is administered by a group of multidisciplinary HCPs.7

There has been an increasing trend in Saudi Arabia’s prevalence and incidence of COPD from 1990 to 2019.8 In 2019, it has been estimated that around 434 560 people had COPD in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.8 This study shows that the burden of COPD is increasing, and public health policy is necessary to offset this trend. PR programmes are an example of community-based primary care management that must be implemented to lessen such a burden.8 However, in Saudi Arabia, PR programmes are often unavailable or underused,9 for multiple reasons, including the lack of trained staff who can manage patients with COPD.10 In addition, PR services across the country must be conducted under close supervision by pulmonologists or internists with an interest in pulmonary medicine, although the number of chest physicians in Saudi Arabia is relatively low.11 12 Consequently, an inadequate number of services are provided to meet the needs of patients with COPD.

International and national COPD management guidelines recommend increasing the implementation of PR programmes worldwide by involving well-trained HCPs in the PR team,5 11 12 considering that COPD is now perceived as a heterogeneous disease with multisystem manifestation that causes systemic consequences.12 Despite the current contribution and involvement of experienced HCPs (eg, nurses, respiratory therapists, physiotherapists, psychologists, occupational therapists, and dietitians) in Saudi PR programmes, awareness of and barriers to healthcare professionals in delivering PR programmes in Saudi Arabia are limited. Recently, we have conducted a study to assess pulmonologists’, internists’ and general practitioners’ attitudes towards the delivery of PR to patients with COPD and to identify factors and barriers that might influence PR referral decisions. Our findings showed that the referral rate was low among all physicians, which was attributed to a lack of PR centres and trained staff.13 Given the fact that our previous study did not survey non-physicians HCPs’ attitudes, although they were implicated as a barrier to referral, the present study aimed to explore allied healthcare professionals’ attitudes and expectations towards delivering a PR programme and identify their views on factors and barriers that might influence the referral of patients with COPD in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted through an online platform (Survey Monkey) between 15 September 2021, and 19 January 2022.

Questionnaire tool

The survey was composed of nine multiple-choice closed questions and free text fields for additional comments; it was structured, formulated and validated by multidisciplinary experts including nursing, respiratory therapy, physiotherapy and nutrition in the field of PR based on the currently available literature.5 7 14 Before the initial distribution, content and face validity were assessed after piloting the survey with 10 healthcare professionals with a clinical background in COPD management.

Before participants started to answer the questionnaire, the aim of the study was provided, together with information about the lead investigator. Additionally, no personal information was recorded; voluntary participation was ensured by asking if participants were happy to complete the survey or not. An additional statement was provided in the survey: ‘By answering “yes” in completing the survey question, you voluntarily agree to participate in this study and give your consent to use your anonymous data for research purposes’. The time required to complete the survey was approximately 3–5 min. The questionnaire consisted of two pages of structured responses that involved multiple-choice answers in three sections. Section 1 requested the respondents' demographic information, including gender, profession, years of experience and responsibilities in the management of COPD. Section 2 consisted of three questions asking about HCPs’ perceptions of PR. The first question had six statements regarding the effectiveness of PR with patients with COPD and used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. The second question asked about additional components of PR aside from the exercise component, and the third question was about the best way to deliver PR for patients with COPD. Section 3 included two questions regarding patient-related factors that influence referral decisions and process-related factors that influence the decision not to refer COPD patients. These questions used influence as a grading tool: no influence, some influence and strong influence (see online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjopen-2022-063900supp001.pdf (148.1KB, pdf)

Sampling strategy

Professional committees managing respiratory diseases such as Saudi Society of Respiratory Care, Saudi Physical Therapy Association and Saudi Nurses Association, and social networks (Twitter, WhatsApp and Telegram) were used to distribute the survey to reach a greater number of HCPs working in Saudi Arabia. Professional committees posted the survey on their social media pages and sent emails to their members. Additionally, four authors from four different medical institutions in four different regions of Saudi Arabia have participated in the data collection. Each data collector was responsible for distributing the survey in his/her region to HCPs to ensure that all the geographical areas of Saudi Arabia were covered.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients were not involved.

Sample size

Convenience sampling techniques were used to recruit the study participants. Nurses, respiratory therapists, physiotherapists, psychologists, occupational therapists and nutritionists involved in managing patients with COPD or who had potential contact with this population were the main targets. Sample size calculation was not required, as this was an exploratory study designed.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS software, V.25). The categorical variables were reported and presented in percentages and frequencies. A χ2 test was used to assess the statistically significant difference between categorical variables. Statistical significance was considered if the p<0.05.

Results

Overall, 980 HCPs (53.1% men) participated in the online survey between 9 September 2021, and 19 January 2022. Nurses accounted for 40.1% of the participants, followed by respiratory therapists (32.1%), physiotherapists (16.5%) and other healthcare specialties (11.2%) such as nutritionists and occupational therapists. The majority of respondents had 1–2 (30%) or 3–4 (26%) years of clinical experience in caring for patients with COPD, while 15.2% had 5–6 years. Oxygen therapy (57%), inpatient treatment (47.1%), ongoing management (42.1%), diagnosis (38.9%) and outpatient clinics (38.1%) were the main responsibilities for managing patients with COPD (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data and characteristics of all study respondents (n=980)

| Demographic variables | Frequency (%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 520 (53.1) |

| Female | 460 (46.9) |

| Profession | |

| Nursing | 393 (40.1) |

| Respiratory therapy | 315 (32.1) |

| Physiotherapy | 162 (16.5) |

| Others | 110 (11.2) |

| Year of experience with patients with COPD | |

| < 1 year | 96 (9.8) |

| 1–2 years | 294 (30) |

| 3–4 years | 255 (26) |

| 5–6 years | 149 (15.2) |

| 7–8 years | 75 (7.7) |

| 9–10 years | 47 (6.5) |

| >10 years | 47 (4.8) |

| Responsibilities for care with patients with COPD | |

| Diagnosis | 381 (38.9) |

| Urgent assessments | 350 (35.7) |

| Non-urgent care | 360 (36.7) |

| Ongoing management | 413 (42.1) |

| Admission prevention | 227 (23.2) |

| Medication check | 360 (36.7) |

| Prescribing | 106 (10.8) |

| Oxygen therapy | 559 (57) |

| In patient treatment | 462 (47.1) |

| Outpatient clinics | 373 (38.1) |

| Primary care | 282 (28.8) |

Data are presented as frequencies and percentages.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

HCP’ opinions on referring patients with COPD

Most HCPs strongly agreed that PR would improve COPD patients’ exercise capacity (589 or 60.1%), and they strongly believed that PR would reduce symptoms of dyspnoea and fatigue (545 or 55.6%). In addition, most HCPs strongly agreed that PR would reduce levels of anxiety and depression (479 or 48.9%), and 571 (58.3%) strongly agreed that PR would improve patients’ health-related quality of life. Moreover, 517 (52.8%) strongly agreed that PR would reduce hospital readmission, and 528 (53.9%) strongly agreed that PR would reduce the risk of future COPD exacerbation. Moreover, 440 HCPs (44.9%) strongly agreed that PR would improve patients’ nutritional status, and the majority strongly agreed that PR would improve disease self-management in COPD patients (589 or 60.1%) (table 2).

Table 2.

Healthcare providers’ perception on referring patients with COPD to pulmonary rehabilitation (n=980)

| Item | Frequency (%) |

| Perception on referring patients with COPD to PR | |

| I believe PR will improve patients’ exercise capacity | |

| Strongly agree | 589 (60.1) |

| Agree | 260 (26.5) |

| Neutral | 32 (3.3) |

| Disagree | 8 (0.8) |

| Strongly disagree | 91 (9.3) |

| I believe PR would reduce dyspnoea and fatigue | |

| Strongly agree | 545 (55.6) |

| Agree | 297 (30.3) |

| Neutral | 62 (6.3) |

| Disagree | 25 (2.6) |

| Strongly disagree | 51 (5.2) |

| I believe PR will improve patients’ anxiety and depression | |

| Strongly agree | 479 (48.9) |

| Agree | 320 (32.7) |

| Neutral | 105 (10.7) |

| Disagree | 29 (3) |

| Strongly disagree | 47 (4.8) |

| I believe PR will improve patients’ health-related quality of life | |

| Strongly agree | 571 (58.3) |

| Agree | 283 (28.9) |

| Neutral | 57 (5.8) |

| Disagree | 19 (1.9) |

| Strongly disagree | 50 (5.1) |

| I believe PR will reduce the risk hospital readmission | |

| Strongly agree | 517 (52.8) |

| Agree | 317 (32.3) |

| Neutral | 70 (7.1) |

| Disagree | 28 (2.9) |

| Strongly disagree | 48 (4.9) |

| I believe PR will reduce the risk of future COPD exacerbation | |

| Strongly agree | 528 (53.9) |

| Agree | 305 (31.1) |

| Neutral | 78 (8) |

| Disagree | 18 (1.8) |

| Strongly disagree | 51 (5.2) |

| I believe PR will improve patients’ nutritional status | |

| Strongly agree | 440 (44.9) |

| Agree | 341 (34.8) |

| Neutral | 117 (11.9) |

| Disagree | 28 (2.9) |

| Strongly disagree | 54 (5.5) |

| I believe PR will improve patients’ disease self-management | |

| Strongly agree | 589 (60.1) |

| Agree | 260 (26.5) |

| Neutral | 32 (3.3) |

| Disagree | 8 (0.8) |

| Strongly disagree | 91 (9.3) |

Data are presented as frequencies and percentages.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

Mode of delivery and components of pulmonary rehabilitation

When asked about the preferred way to deliver a PR programme for patients with COPD, most HCPs believed that in-hospital supervised PR was the preferred method (748 or 76.3%), followed by delivering the PR at home (557 or 56.8%). However, only 275 (28.1%) believed that tailored PR with healthcare provider support over the phone would be the preferred method. Most HCPs believed that the essential components of PR include information about COPD disease (832 or 84.9%), followed by smoking cessation (787 or 80.3%) and COPD symptoms’ management (749 or 76.4%), aside from the exercise component (table 3).

Table 3.

Mode of delivery and component of pulmonary rehabilitation programme (n=980)

| Item | Frequency (%) |

| The best way to deliver PR programme for patients with COPD | |

| In hospital supervised programme | 374 (38.16) |

| At home | 276 (28.16) |

| Online programme with healthcare provider support | 192 (19.59) |

| Tailored programme with healthcare provider support through phone | 138 (14.08) |

| Component of PR programme aside from exercise component | |

| Information about COPD disease | 832 (84.9) |

| Smoking cessation | 787 (80.3) |

| Symptoms management | 749 (76.4) |

| Psychological support | 671 (68.5) |

| Information about medications | 648 (66.1) |

| Nutritional counselling | 526 (53.7) |

Data are presented as frequencies and percentages.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

Patient-related factors that influence referral decisions to pulmonary rehabilitation

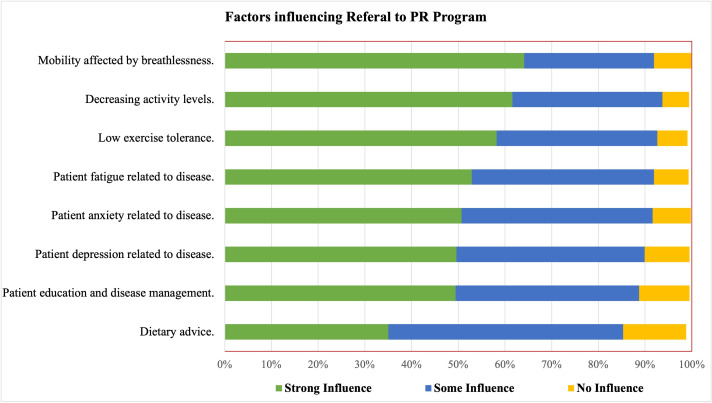

The main factors that strongly influenced the decision to refer patients with COPD to PR from the HCPs’ perspective included mobility affected by patients’ breathlessness (64.10%), followed by low activity levels (61.60%), low exercise tolerance (58.20%), patient fatigue related to COPD (52.90%) and patient anxiety related to COPD (50.70%) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient-related factors that influence referral decision to pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), using strong, some or no influence grading (n=980).

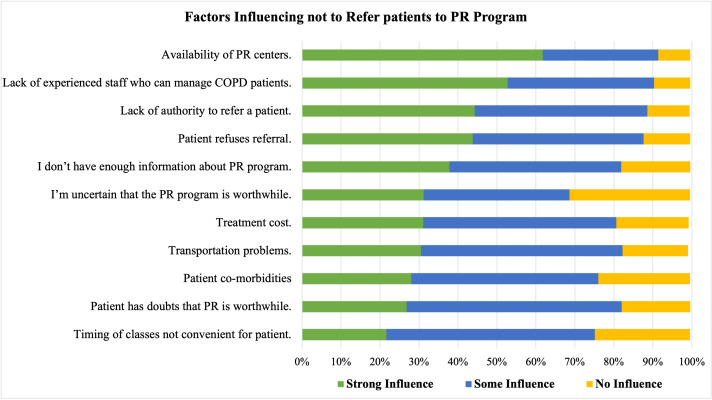

Pulmonary rehabilitation referral barriers

From the HCPs' perspective, the main barriers that strongly affect the referral process for patients with COPD included a lack of available PR centres (61.80%), followed by a lack of trained HCPs who could manage patients with COPD (52.70%) and the lack of authority to refer a patient (44.30%). In addition, 43% reported that patients might refuse the referral process (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Barriers to referring patients with COPD to PR from HCPs perspective, using strong, some or no influence grading (n=980). COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCPs, healthcare providers; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first national study that explores assess non-physician HCPs attitudes and expectation toward delivering PR to COPD patients and identify factors and barriers that might influence referral in Saudi Arabia. Findings show that HCPs perceived PR as an effective management strategy in improving clinical outcomes in COPD. While a supervised hospital-based programme was seen as the preferred mode of delivery, the lack of PR centres, well-trained staff, and the authority to refer posed significant barriers to PR referrals. HCPs perceived patients’ education about COPD disease, smoking cessation and symptoms management as the most essential components of PR programme next to exercise component.

PR has established a solid position as the cornerstone of the management of patients with COPD. Indeed, current evidence shows that PR alleviates exercise limitations and dyspnoea, improves nutritional status and psychological well-being and reduces hospitalisations, future COPD exacerbations and mortality rates.5 15 16 In our study, HCPs perceived mobility affected by breathlessness, low activity levels and low exercise tolerance as the most common factors that influence referral decision which are in accordance with current international guidelines.17 18 According to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and British Thoracic Society PR should be offered to patients who are short of breath and functionally limited due to breathlessness.17 18 All these reported factors that influence referral have been shown to effectively improved in patients with COPD who were enrolled in PR.19

Despite the current evidence of PR effectiveness, the global referral rate is currently suboptimal.13 20 21 Current international COPD guidelines recommend the involvement of experienced HCPs in the referral management of COPD patients; however, referral to PR cannot be performed without physicians’ permission in Saudi Arabia.11 17 19 21 22 In the current study, nearly half of the participants believed that a lack of authority to refer posed a significant barrier to PR referral. Therefore, experienced HCPs who are part of the PR team or COPD management should promote physicians’ knowledge about PR and its potential to enhance the PR referral rate.

Reasons for not referring patients with COPD to PR programmes are likely to be multifactorial; lack of available PR centres is at top of the list, as shown in this study which is in accordance with recent study that included physicians and concluded that limited PR centres was the cause of low PR referral.13 Saudi Arabia has a limited number of PR centres, and the number of people who can access these centres is extremely low.9 This contrasts, for instance, with the situation in the UK, which has 228 PR services. The gap in the current practice is therefore clear, and the establishment of new PR programmes needs to be facilitated across the country. It is however important to mention that PR programmes can be offered within the existing infrastructure using the incumbent HCPs in the hospitals.23 It has been previously demonstrated that an outpatient PR programme offered at a small hospital is as effective as a programme offered in a large hospital.24 Current evidence also suggests that PR can be effectively offered using different modalities, including inpatient, community-based, home settings or online.24 25 Thus, any of these modes of delivery can be adopted according to the hospital’s available resources.

Participants in this study also perceived the lack of well-trained staff as a major barrier to PR referral, in concordance with the current literature.13 19 21 26 Studies show that Saudi Arabia suffers from a severe shortage of healthcare professionals and that only limited specialties participate in the management of COPD.27 28 Evidence suggests that COPD management is much better if performed by a multidisciplinary team,28 29 highlighting the need for an integrated approach. It is however important to mention that the number of specialised physicians and healthcare professionals (eg, respiratory nurses and respiratory physiotherapists) is, overall, low,27 28 which could affect the quality of COPD care in the country. Therefore, the healthcare authority in Saudi Arabia should take action to reduce the current shortage by providing training incentives to people willing to specialise in respiratory medicine and encouraging the upskilling of current healthcare workers. In addition, offering high-quality education either inside or outside the country could be a useful approach to stimulate this change.

Almost half of the study participants perceived ‘patients might refuse the referral’ as a major barrier to refer COPD patients to PR which is in accordance with recent study included physicians and concluded that 46% perceived patients refuse referral is a major barrier.13 This may be due to the lack of patients’ knowledge about the PR and its benefit to their condition as well as travel distance to PR.19 30 31 Therefore, incorporating patients’ preferences of PR delivery mode and increasing awareness of PR and its benefit among COPD population are needed.

Almost 80% of HCPs in this study considered supervised hospital-based programmes the preferred mode of PR delivery, despite the limited number of PR centres in the country. This is likely because of a lack of knowledge about PR services in Saudi Arabia, as only a small proportion of HCPs know what PR is.10 However, utilising the available resources within the infrastructure of the hospital remains possible for setting up and delivering a PR programme. Alternatively, home settings, which are as effective as conventional PR programmes in improving exercise capacity and respiratory symptoms,32 could be considered a viable option.

In this study, most HCPs believed that information about COPD disease, smoking cessation and symptoms management are the most important components of a PR programme. Indeed, disease-related education contributes to patients’ recognition of their symptoms and worsening disease.33 However, the content of the PR educational programme, who delivers it, and how it is delivered remain unclear. According to the American Thoracic Society/ European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) official consensus, smoking cessation is a major component of a PR programme.7 14 It is the primary cause of COPD, with the prevalence of COPD smokers ranging from 38% to 77%.34 In addition, smoking contributes to 73% of COPD-related deaths worldwide.35 Smoking is also associated with accelerated lung function declines, higher COPD exacerbations36 37 and increased dropout rates from PR. Therefore, support for smoking cessation should be offered throughout the PR programme.

Further research is needed to address COPD patients’ attitudes and expectations toward delivering a PR programme and identify factors and barriers of referring. Additionally, future research should also focus on suitable mode of delivering PR as well as essential components from patients’ perspective.

Limitations

Convenience sample techniques were used in the study, which may impose a selection bias. In this study, we did not survey or interview physicians who are part of COPD management. Additionally, we have failed to report the geographic distribution of the respondents. Moreover, the exact number of HCPs who involved in PR and with patients with COPD is unclear; therefore, the sample of our study may not represent the general population of HCPs. Finally, the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted respondents’ opinions, especially given that 28% of the total number of respondents reported that home PR is their preferred method of PR delivery.

Conclusion

HCPs across specialties agreed on the effectiveness of PR for patients with COPD. A supervised hospital-based programme is the preferred mode of PR delivery, with information about COPD disease and smoking cessation being considered essential components of PR in addition to the exercise component. The lack of PR centres and well-trained staff and the lack of authority to refer patients were major barriers to the referral of patients with COPD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @DrAbdulelah1989

Contributors: The study was designed by AA, MA and JSA. Data collection was performed by AAA, IAA, HA and ASA, statistical methodology was performed by AA, and formal analysis was performed by AH, YSA and SMA. The draft of the manuscript was written by AMA, AAA, IAA, RS, EMA and MA, and reviewed and revised by EMA, JSA, HW and SMA. All authors approved the paper for publication. AA is the guarantor of the manuscript and accept full responsibility for the work and conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Institutional Review Board approval for the study was obtained from Jazan University, reference number (HAPO-10-Z-001). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Halpin DMG, Criner GJ, Papi A, et al. Global initiative for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease. The 2020 gold science Committee report on COVID-19 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:24–36. 10.1164/rccm.202009-3533SO [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alqahtani JS, Njoku CM, Bereznicki B, et al. Risk factors for all-cause hospital readmission following exacerbation of COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev 2020;29. 10.1183/16000617.0166-2019. [Epub ahead of print: 30 Jun 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Trott P, Oei SL, Ramsenthaler C. Acupuncture for breathlessness in advanced diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;59:327–38. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans RA, Singh SJ. Minimum important difference of the incremental shuttle walk test distance in patients with COPD. Thorax 2019;74:994–5. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American thoracic Society/European respiratory society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:e13–64. 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahin H, Naz I, Varol Y, et al. Is a pulmonary rehabilitation program effective in COPD patients with chronic hypercapnic failure? Expert Rev Respir Med 2016;10:593–8. 10.1586/17476348.2016.1164041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland AE, Cox NS, Houchen-Wolloff L, et al. Defining modern pulmonary rehabilitation. An official American thoracic Society workshop report. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021;18:e12–29. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202102-146ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alqahtani JS. Prevalence, incidence, morbidity and mortality rates of COPD in Saudi Arabia: trends in burden of COPD from 1990 to 2019. PLoS One 2022;17:e0268772. 10.1371/journal.pone.0268772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldhahir AM, Alghamdi SM, Alqahtani JS, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD: a narrative review and call for further implementation in Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med 2021;16:299–305. 10.4103/atm.atm_639_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alsubaiei ME, Cafarella PA, Frith PA, et al. Barriers for setting up a pulmonary rehabilitation program in the eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med 2016;11:121–7. 10.4103/1817-1737.180028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan JH, Lababidi HMS, Al-Moamary MS, et al. The Saudi guidelines for the diagnosis and management of COPD. Ann Thorac Med 2014;9:55–76. 10.4103/1817-1737.128843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celli BR, Decramer M, Wedzicha JA, et al. An official American thoracic Society/European respiratory Society statement: research questions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:e4–27. 10.1164/rccm.201501-0044ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aldhahir AM, Alqahtani JS, Alghamdi SM, et al. Physicians' attitudes, beliefs and barriers to a pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD patients in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Healthcare 2022;10:904. 10.3390/healthcare10050904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill K, Vogiatzis I, Burtin C. The importance of components of pulmonary rehabilitation, other than exercise training, in COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2013;22:405–13. 10.1183/09059180.00002913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. Gold executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:557–82. 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aldhahir AM, Rajeh AMA, Aldabayan YS, et al. Nutritional supplementation during pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a systematic review. Chron Respir Dis 2020;17:1479973120904953. 10.1177/1479973120904953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolton CE, Bevan-Smith EF, Blakey JD, et al. British thoracic Society guideline on pulmonary rehabilitation in adults. Thorax 2013;68 Suppl 2:ii1–30. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Guidelines, in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16S: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Copyright © NICE 2018; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rochester CL, Vogiatzis I, Holland AE, et al. An official American thoracic Society/European respiratory society policy statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:1373–86. 10.1164/rccm.201510-1966ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milner SC, Boruff JT, Beaurepaire C, et al. Rate of, and barriers and enablers to, pulmonary rehabilitation referral in COPD: a systematic scoping review. Respir Med 2018;137:103–14. 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston KN, Young M, Grimmer KA, et al. Barriers to, and facilitators for, referral to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients from the perspective of Australian general practitioners: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2013;22:319–24. 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogg L, Garrod R, Thornton H, et al. Effectiveness, attendance, and completion of an integrated, system-wide pulmonary rehabilitation service for COPD: prospective observational study. COPD 2012;9:546–54. 10.3109/15412555.2012.707258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins S, Hill K, Cecins NM. State of the art: how to set up a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Respirology 2010;15:1157–73. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01849.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward JA, Akers G, Ward DG, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of a pulmonary rehabilitation programme in a community hospital setting. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:539–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maltais F, Bourbeau J, Shapiro S, et al. Effects of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:869–78. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldhahir AM, Alhotye M, Alqahtani JS, et al. Physiotherapists’ Attitudes, and Barriers of Delivering Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation for Patients with Heart Failure in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2022;15:2353–61. 10.2147/JMDH.S386519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aboshaiqah A. Strategies to address the nursing shortage in Saudi Arabia. Int Nurs Rev 2016;63:499–506. 10.1111/inr.12271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alsubaiei ME, Cafarella PA, Frith PA, et al. Factors influencing management of chronic respiratory diseases in general and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in particular in Saudi Arabia: an overview. Ann Thorac Med 2018;13:144–9. 10.4103/atm.ATM_293_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuzma AM, Meli Y, Meldrum C, et al. Multidisciplinary care of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:567–71. 10.1513/pats.200708-125ET [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox NS, Oliveira CC, Lahham A, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation referral and participation are commonly influenced by environment, knowledge, and beliefs about consequences: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework. J Physiother 2017;63:84–93. 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lahham A, Holland AE. The need for expanding pulmonary rehabilitation services. Life 2021;11:1236. 10.3390/life11111236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD003793. 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crisafulli E, Loschi S, Beneventi C, et al. Learning impact of education during pulmonary rehabilitation program. An observational short-term cohort study. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2010;73:64–71. 10.4081/monaldi.2010.300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tønnesen P. Smoking cessation and COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2013;22:37–43. 10.1183/09059180.00007212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacNee W. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 5th ed. Oxford University Press, 2010: 3311–44. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Badaran E, Ortega E, Bujalance C, et al. Smoking and COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J 2012;40:P1055 https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/40/Suppl_56/P1055.short [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown AT, Hitchcock J, Schumann C, et al. Determinants of successful completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11:391–7. 10.2147/COPD.S100254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-063900supp001.pdf (148.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.