Abstract

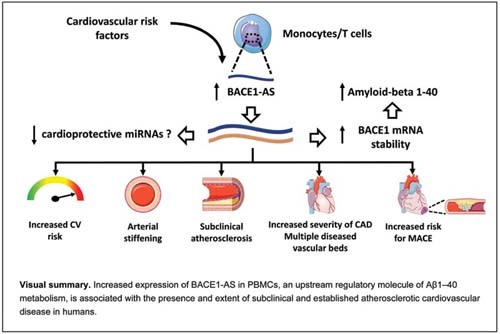

Background The noncoding antisense transcript for β-secretase-1 ( BACE1-AS ) is a long noncoding RNA with a pivotal role in the regulation of amyloid-β (Aβ). We aimed to explore the clinical value of BACE1-AS expression in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

Methods Expression of BACE1-AS and its target, β-secretase 1 ( BACE1 ) mRNA, was measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from 434 individuals (259 without established ASCVD [non-CVD], 90 with stable coronary artery disease [CAD], and 85 with acute coronary syndrome). Intima-media thickness and atheromatous plaques evaluated by ultrasonography, as well as arterial wave reflections and pulse wave velocity, were measured as markers of subclinical ASCVD. Patients were followed for a median of 52 months for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).

Results In the cross-sectional arm, BACE1-AS expression correlated with BACE1 expression ( r = 0.396, p < 0.001) and marginally with Aβ1–40 levels in plasma ( r = 0.141, p = 0.008). Higher BACE1-AS was associated with higher estimated CVD risk assessed by HeartScore for non-CVD subjects and by European Society of Cardiology clinical criteria for the total population ( p < 0.05 for both). BACE1-AS was associated with higher prevalence of CAD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.85, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.37–2.5), multivessel CAD (OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.06–1.75), and with higher number of diseased vascular beds (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.07–1.61, for multiple diseased vascular beds) after multivariable adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors. In the prospective arm, BACE1-AS was an independent predictor of MACE in high cardiovascular risk patients (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.86 per ascending tertile, 95% CI: 1.011–3.43, p = 0.046).

Conclusion BACE1-AS is associated with the incidence and severity of ASCVD.

Keywords: beta-secretase-1 antisense RNA, long noncoding RNA, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, amyloid-β

Introduction

Despite therapeutic advances targeting underlying pathophysiologic pathways, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) remains the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the Western world. 1 This suggests the presence of residual risk stemming from therapeutically untargeted, unrecognized, or not fully elucidated molecular pathways involved in the development and progression of ASCVD. A growing amount of evidence points toward a central role of noncoding RNAs, which act as regulatory molecules, in the pathophysiology of atherosclerotic disease. 2 3 4 5 The noncoding antisense transcript for β-secretase-1 ( BACE1-AS ) is a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) that is transcribed from the noncoding complementary DNA (cDNA) chain of β-secretase 1 ( BACE1 ) locus protecting BACE1 mRNA stability. 6 In detail, BACE1 and BACE1-AS form a RNA duplex, which can modify the secondary or tertiary structure of BACE1 mRNA and therefore increase its stability. 6 BACE1 cleaves the β-site of the amyloid precursor protein resulting in the production of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides after further proteolytic cleavage by gamma secretase. 7 Thus, BACE1-AS is a pivotal regulator of Aβ production in brain and peripheral tissues. 8 9

The production and deposition of Aβ peptides is considered the hallmark of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease (AD) 7 and cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which is characterized by arterial deposition of Aβ1–40. 10 Notably, traditional cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs) have been strongly associated with increased risk for future cognitive impairment in healthy individuals. 11 Importantly, mitigation of those risk factors is an efficient strategy to reduce the incidence and progression of dementia. 12 In addition, the presence of intracerebral atherosclerotic disease accelerates cognitive decline in demented patients and has been associated with worse cognitive function even in apparently healthy persons. 12 13 This evidence strongly suggests shared cellular and molecular mechanisms between dementia and atherosclerotic disease. Aβ1–40 metabolism may be a common link between these diseases. We have previously shown that Aβ1–40 in blood is critically involved in ASCVD. 7 Aβ1–40 blood levels are associated with CVRFs and atherosclerosis in various vascular beds, while its changes over time are associated with accelerated progression of aortic stiffening and atherosclerosis. 14 15 Importantly, circulating Aβ1–40 is an independent prognostic factor of mortality in stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS). 16 17 We have recently reported increased expression of BACE1-AS and BACE1 and consequently increased Aβ1–40 deposits in the myocardium of patients with heart failure. 18 Whether BACE1-AS is associated with entities of ASCVD remains unknown. Studying the BACE1-AS regulatory function in humans may provide novel mechanistic insight into the clinical role of this lncRNA in ASCVD, as well as into its potential as a possible therapeutic target. Herein, we sought to assess the association between BACE1-AS expression and vascular aging and the presence, severity, and incidence of ASCVD.

Methods

Population and Design

A total of 434 consecutive patients were recruited between November 2013 and December 2017. This population consisted of 259 individuals without clinically overt ASCVD, 90 patients with stable CAD who were examined consecutively in the Dyslipidemias and Atherosclerosis Unit of the Department of Clinical Therapeutics, Alexandra Hospital, Athens, Greece, for cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment, and of 85 patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) at the same time period. ACS patients were consecutively recruited from the cardiac care unit or ward of the Department of Clinical Therapeutics, Alexandra Hospital, Athens, Greece within 12 hours of symptom onset. Stable CAD and ACS precise definitions are provided in the Supplementary Material (available in the online version). Exclusion criteria for all the study's population included autoimmune disease, cancer, acute renal failure, acute stroke, chronic inflammatory disease, or active infection. In addition, exclusion criteria for the non-CVD group included acute or chronic clinically overt cardiovascular, or cerebrovascular, or peripheral vascular disease. History of ASCVD was confirmed by previous coronary angiography or documents adjudicating ACS by ECG criteria, levels of cardiac enzymes, and coronary angiography in the acute phase. 19 CVRFs were meticulously recorded for each patient. CVRF burden was defined as the sum of the presence of each of the following risk factors: age >65 years, male gender, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 60 mL/min/1.73 m 2 , smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, obesity, and increased high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) (>2 mg/L). 20 Patients were also classified to risk categories according to European Society of Cardiology (ESC) clinical criteria as described in the Supplementary Material (available in the online version). Τhe number of angiographically confirmed diseased coronary arteries was used to assess the extent of CAD in patients with established CAD. A diseased coronary artery was defined as >50% stenosis. 21

Patients who consented to attend the clinic regularly were followed annually, either by site visit or by telephone contact, and adverse CVD events were recorded. Specifically, medical records were reviewed and evaluated regarding the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), which were defined as CVD death, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and performance of coronary revascularization procedure. CVD death was defined as death resulting from myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death, death due to heart failure, stroke, and other CVD causes. 22 AMI was defined according to the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). 19 Coronary revascularization procedures included percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting. Analysis for events was performed only in patients estimated to be at high/very high risk for mortality or MACE ( N = 237), according to ESC criteria, because the rest of the population, estimated at low or moderate CVD risk, was expected to have very few events for the available sample size. CVD risk was calculated as described previously and in the Supplementary Material (available in the online version). 14 15 16 17

The present study was conducted under the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All individuals provided written informed consent form, and the ethics committee of the Alexandra Hospital of the University of Athens approved the protocol.

Vascular Measurements for Assessment of Subclinical Arterial Disease

Structural and functional vascular measurements were used as surrogate markers of subclinical ASCVD. Intima-media thickness (IMT) and presence of atherosclerotic plaques were measured by ultrasonography and pulse wave velocity. 23 24 These methods are described in detail in the Supplementary Material (available in the online version).

The number of vascular beds with abnormal vascular markers was used as a measure of the extent of ASCVD and was defined as follows: (1) carotid arteries (presence of plaque), (2) coronary arteries (presence of plaque with stenosis >50%), (3) aorta (increased pulse wave velocity [PWV]), and (4) femoral arteries (presence of plaque), defined as values distributed in the highest tertile as previously described. 25 All measurements were recorded in a supine position after 5 minutes of rest and all the participants were examined by a single experienced investigator. Vascular measurements were available in the non-CVD and stable CAD cohorts.

Biochemical Methods

Venous blood samples were obtained from the non-CVD and the stable CAD group in the morning, after overnight fasting and abstinence from any medication for at least 10 hours, while in the ACS group blood samples were obtained within 12 hours of symptom onset. Plasma and serum samples were stored at −80°C until procession. High-sensitivity troponin I was measured in the ACS group using the diagnostic Test Pathfast hs-cTnI (Roche) in heparinized or EDTA whole blood. GFR was estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation. Concentrations of Αβ1–40 were measured in EDTA-stored plasma samples derived from 353 consecutive subjects. A well-documented enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Biosource/Invitrogen, California, United States) was used, as stated previously. 15 The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variance of the ELISA measurements were reported to be less than 8% 26 and the minimum detectable concentration of human Αβ1–40 was <6 pg/mL (Biosource/Invitrogen). All measurements were performed by experienced personnel who were blinded to patients' characteristics.

Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

Peripheral blood was collected in EDTA-containing tubes (BD Vacutainer) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using standard methods by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, as previously described, 27 from all study participants. Isolated PBMCs were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and subsequently lysed in QIAzol (Qiagen) and stored at −80°C until further processing.

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

Total RNA was extracted from PBMCs using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research) with an additional DNase digestion step according to manufacturer's instructions. One microgram (1 µg) of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with the use of MuLV reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

cDNA derived from PBMCs was subjected to quantitative SYBR Green real-time polymerase chain reaction using Takara SYBR Premix Ex Taq on ViiA7 system or PowerUP SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on QuantStudio 7 Flex. Specific primers for BACE1 and BACE1-AS were used ( BACE1 , forward: 5′- GCAGGGCTACTACGTGGAGA -3′; reverse: 5′-CAGCACCCACTGCAAAGTTA - 3′; BACE1-AS , forward: 5′- ATTTCACCCTGTTGGTCAGG -3′; reverse: 5′- TCAGCAACAGCCAAGATGTC - 3′), while RPLP0 served as the housekeeping gene (RPLP0: forward: 5′-TCGACAATGGCAGCATCTAC-3′; reverse: 5′-ATCCGTCTCCACAGACAAGG-3′). The relative expression levels of each gene were determined using the equation: 2 −Δ Ct , where Δ Ct = Ct (gene) – Ct (housekeeping gene).

Single-Cell Sequencing Analysis

The Single Cell Portal database ( https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell ) was used to generate t-SNE (t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding) plots and gene expression plots in different cell types from PBMCs. Data are merged from PBMC samples derived from two healthy individuals. 28 The Plaqview database ( www.plaqview.com ) 29 was used to uncover gene expression in the entire atherosclerotic core and proximally adjacent regions from three patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy (Dataset GSE159677 retrieved from National Center for Biotechnology Information's [NCBI] Gene Expression Omnibus [GEO]). 30 Data were visualized in two dimensions using the “uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction” (UMAP) method.

Microarray Data Analysis

Dataset GSE85965 was retrieved from NCBI's GEO. The dataset contains samples from changes induced by the forced overexpression of BACE1-AS compared with a negative control (empty vector) in human aortic endothelial cells. BACE1-AS was overexpressed by pREceiver-Lv-105 (GeneCopoeia) lentivirus-expressing BACE1-AS human cDNA and transcriptome changes were measured by the llumina HumanHT-12 v4 BeadChip platform. 18 The transcriptomic changes were analyzed using DAVID's tool for significant enrichment associated with biological process ( https://david-d.ncifcrf.gov/ ; v.6.7) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis to explore the most enriched pathways.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables are presented as mean values ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) for not normally distributed variables. The categorical variables are presented as absolute values (count) and percentages. Normality of continuous variables was graphically assessed through histograms and P–P plots. Correlations between continuous variables were tested using Pearson's or Spearman correlation coefficients for normally or skewed variables. Differences in continuous variables between groups of patients according to patient group or BACE1/BACE1-AS and Αβ1–40 distribution (i.e., tertiles) were evaluated through the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test and chi-squared test for nominal variables. Pairwise comparisons for continuous parameters were performed with two-sample Student's t -test or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

Subsequently, we implemented regression analysis (i.e., linear regression, ordinal regression, and logistic regression) to evaluate the association between baseline determinants and parameters of interest, including markers of subclinical atherosclerosis, after adjusting for various confounders. All multivariable regression models were adjusted for traditional risk factors (age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking) and for eGFR (core model) and presence of CAD, where applicable. No selection procedure was applied in building of the multivariable models and all available confounders of biological plausibility were included. For a subgroup of high/very high-risk patients ( n = 237) and available follow-up information, we also conducted Cox regression analysis to evaluate the association of baseline BACE-AS levels and the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events. Proportional hazards assumption was tested using the Schoenfeld residuals. Subjects were censored at the time of the first cardiovascular event. Given the low number of events and to guard against overfitting, we used only significant predictors at the univariable level in the final multivariable model. Statistical analysis was performed by STATA package, version 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, United States). We deemed statistical significance at p = 0.05. We used a ratio of 5 to 10 events per one covariate as a rule of thumb to avoid overfitting in regression models.

In terms of power considerations, our study with 434 subjects was adequately powered at 0.85 level to detect a 1.5-fold alteration in odds ratio (OR) for presence of CAD per 1-SD increase in BACE1-AS . Prevalence of CAD was set at 0.2 in the control group for power calculations, which were confirmed by resampling with 1,000 replications. Type I error was predefined as 0.05 and the corresponding test was two-tailed. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Results

BACE1-AS Is Associated with High CVD Risk Profile

A detailed flowchart of the study's population is provided in Supplementary Fig. S1 (available in the online version) and descriptive characteristics by BACE1-AS tertiles are shown in Table 1 . Patients with higher levels of BACE1-AS expression were more often male, older, and with higher CVRF burden. Specifically, higher prevalence of hypertension and hyperlipidemia, elevated hs-CRP, and lower GFR were observed in subjects at the higher BACE1-AS tertiles compared with the lowest tertile.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of study population according to BACE1-AS tertiles .

| Variable | N | All | 1st tertile | 2nd tertile | 3rd tertile | p -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 429 | 59.5 (11.9) |

57.3 (11.3) |

61.5 (12.6) |

59.7 (11.4) |

0.01 |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 430 | 244 (56.74) |

67 (46.21) |

93 (65.96) |

84 (58.33) |

0.003 |

| Non-CVD, n (%) | 259 | 259 (59.7%) | 113 (43.8%) | 81 (31.2%) |

65 (25%) |

<0.001 |

| Stable CAD, n (%) | 90 | 90 (20.7%) |

12 (13.3%) |

41 (45.6%) |

37 (41.1%) |

<0.001 |

| ACS, n (%) | 85 | 85 (19.6%) |

19 (22.4%) |

24 (28.2%) |

42 (49.4%) |

<0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 354 | 27.6 (4.77) |

27.6 (5.11) |

27.7 (4.56) |

27.5 (4.6) |

0.944 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 366 | 129 (19.5) |

127 (18.2) |

131 (20.1) |

130 (20.3) |

0.219 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 366 | 73.7 (10.5) |

72.2 (9.77) |

74.1 (11) |

74.9 (10.7) |

0.098 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 420 | 186 (44.29%) |

60 (41.67%) |

58 (42.96%) |

68 (48.23%) |

0.501 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 423 | 184 (43.50%) | 44 (30.56%) |

75 (54.74%) |

65 (45.77%) |

<0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 422 | 194 (45.97%) | 48 (33.33%) |

69 (50.74%) |

77 (54.23%) |

0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 423 | 75 (17.73%) |

22 (15.28%) |

25 (18.25%) |

28 (19.72%) |

0.605 |

| Presence of carotid plaques, n (%) | 378 | 183 (48.41%) | 56 (44.44%) |

61 (47.66%) |

66 (53.23%) |

0.373 |

| Presence of any plaque, n (%) | 374 | 212 (56.68%) | 65 (52.00%) |

73 (57.03%) |

74 (61.16%) |

0.348 |

| Presence of femoral plaques, n (%) | 376 | 158 (42.02%) | 46 (36.51%) |

54 (42.52%) |

58 (47.15) |

0.233 |

| Patients with high or very high CVD risk profile, n (%) | 420 | 319 (75.95%) | 93 (65.49%) |

112 (80.58%) |

114 (82.01%) |

0.001 |

| *HeartScore, n (%) | 115 | 6 (2–9) |

4 (2–8) |

6 (3- 9) |

6 (2–10) |

0.004 |

| *GFR (mL/min) | 405 | 94.2 (68.1–113) |

101 (83.4–121) |

81.3 (58.7–105) |

97.2 (72.6–115) |

<0.001 |

| *hs-CRP (mg/L) | 380 | 0.23 (0.080–0.875) |

0.15 (0.07–0.6) |

0.35 (0.09–1.33) |

0.294 (0.095–0.906) |

0.017 |

| *Pulse wave velocity (m/s) | 300 | 8.97 (7.95–10.9) |

8.25 (7.55–9.9) |

9.95 (8.35–12.4) |

9.05 (8.05–11.2) |

<0.001 |

| *Augmentation index (%) | 277 | 26 (20–31) |

26 (20–31) |

25.5 (20–31) |

26 (20–32) |

0.646 |

| *Time of return of reflected waves (ms) | 279 | 140 (133–146) |

141 (138–148) |

142 (132–148) |

138 (132–143) |

0.003 |

| *Common carotid artery IMT (mm) | 344 | 0.83 (0.72–0.98) |

0.79 (0.68–0.92) |

0.867 (0.735–1.04) |

0.84 (0.75–0.98) |

0.014 |

| *Total number of femoral and carotid segments with plaque | 388 | 1 (0–2) |

0 (0–2) |

1 (0–3) |

1 (0–3) |

0.194 |

| *Number of diseased vascular beds | 434 | 1 (0–2) |

1 (0–2) |

1 (1–3) |

1 (1–3) |

0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; IMT, intima-media thickness; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Note: p -Value is derived from analysis of variance or the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis rank test (*) for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for nominal variables. High/very high CVD risk was defined according to ESC Guidelines. 20 Diseased vascular beds were defined as: (1) carotid arteries with presence of plaque, (2) coronary arteries with presence of plaque with stenosis >50%, (3) femoral arteries with presence of plaque.

Regarding estimated risk, in the non-CVD population, where HeartScore is recommended for risk stratification, 20 median HeartScore in higher BACE1-AS tertiles was 6% (>5% cutoff for high risk) as compared with the lowest tertile, with a median of 4%, reflecting moderate risk ( Table 1 ). Patients at the higher tertiles of BACE1-AS were also more often classified at high or very high CVD risk according to criteria by ESC guidelines 20 than those in the lowest tertile ( Table 1 ).

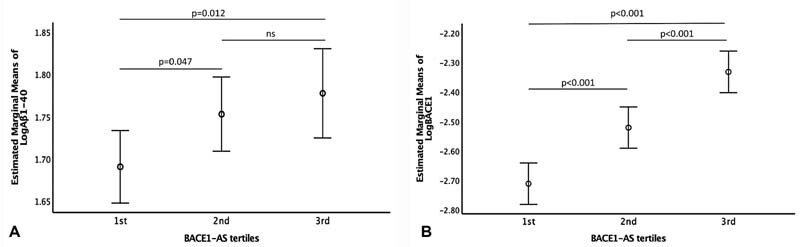

BACE1-AS Is Associated with BACE1 and Aβ1–40

A linear correlation was observed between BACE1-AS and BACE1 expression levels ( r = 0.396, p < 0.001) in the total study's population. This correlation was stronger in the CAD group ( n = 175, r = 0.584, p < 0.001). BACE1-AS was also positively correlated with Aβ1–40 in plasma ( n = 353, r = 0.141, p = 0.008), suggesting an association between PBMC expression of BACE1-AS and increased Aβ1–40 burden in the peripheral circulation. By linear regression analysis, Aβ1–40 levels increased across ascending tertiles of BACE1-AS (2nd vs. 1st tertile estimated mean difference: 0.062, p -value = 0.047, 3rd vs. 1st tertile estimated mean difference: 0.087, p = 0.012, Fig. 1A ). Similarly, BACE1 levels increased significantly across all three tertiles of BACE1-AS (estimated mean difference 2nd vs. 1st tertile = 0.190, 3rd vs. 1st tertile = 0.380, 3rd vs. 2nd tertile = 0.190, p < 0.001 for all) ( Fig. 1B ).

Fig. 1.

Estimated marginal means of: ( A ) Aβ1–40 across BACE1 -AS tertiles, ( B ) BACE1 expression across BACE1-AS tertiles. Number of participants in each BACE1-AS tertile: 1st tertile N = 144, 2nd tertile N = 146, 3rd tertile N = 144. p -Values were derived from linear regression analysis. Relative BACE1-AS, BACE1 expression, and plasma Aβ1-40 (pg/mL) were transformed to logarithmic scale prior to analysis. ; Aβ1–40, amyloid β 1–40; BACE1 , β secretase-1; BACE1-AS , β secretase antisense RNA.

BACE1-AS Expression Is Associated with Arterial Injury and Stiffness

In the combined non-CVD and stable CAD cohorts, BACE1-AS was positively associated with common carotid IMT (β-coefficient = 0.034 per 1-SD increase in BACE1-AS , p = 0.005, univariate analysis) ( Table 2 ). This association remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, hypertension, hypolipidemic treatment, diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, and grouping ([non-CVD vs. CAD], [core model, β-coefficient = 0.02, p = 0.042, Table 2 ]). BACE1-AS was positively associated with PWV, a well-established marker of aortic stiffness, after univariable and multivariable analyses for the same core model (β-coefficient = 0.02 and β-coefficient = 0.01, p = 0.003 and p = 0.035, respectively) ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. BACE1-AS association with indices of subclinical atherosclerosis and with the presence of CAD, CAD severity, and number of diseased vascular beds .

| PWV | ccIMT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BACE1-AS | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| Univariable | 0.02 (0.007–0.034) |

0.003 | 0.034 (0.01–0.057) |

0.005 | |||

| Multivariable a |

0.01

b

(0.001–0.02) |

0.035 | 0.02 (0.001–0.039) |

0.042 | |||

| Presence of CAD | Number of diseased coronary vessels c | Number of diseased vascular beds | |||||

| BACE1-AS | OR (95% CI) |

p-Value | OR (95% CI) |

p-Value | OR (95% CI) |

p-Value | |

| Univariable | 1.72 (1.36–2.17) |

<0.001 | 1.30 (1.031–1.63) |

0.026 | 1.39 (1.15–1.69) |

0.001 | |

| Multivariable c | 1.85 (1.37–2.5) |

<0.001 |

1.36

d

(1.06–1.75) |

0.015 | 1.31 (1.07–1.61) |

0.011 | |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BACE1-AS , β secretase antisense RNA; CAD, coronary artery disease; ccIMT, common carotid artery intima-media thickness; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; OR, odds ratio; PWV, pulse wave velocity; SD, standard deviation.

Note: ORs and 95% CI correspond to 1 SD increase in BACE1-AS in original (number of beds) or logarithmic scale (PWV and ccIMT). PWV and ccIMT were transformed in the logarithmic scale prior to their use as dependent outcomes in regression analysis. Results for the outcomes PWV and ccIMT are presented for the total population excluding ACS patients. Results for the outcomes presence of CAD and number of diseased vascular beds are presented in the total population. Results for the outcome number of diseased coronary vessels are presented in the total population the non-CVD cohort. Diseased vascular beds were defined as: (1) carotid arteries with presence of plaque, (2) coronary arteries with presence of plaque with stenosis >50%, and (3) femoral arteries with presence of plaque.

Adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, hypolipidemic treatment, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and group (non-CVD vs. ACS).

Adjusted for systolic blood pressure instead of hypertension.

Adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, hypolipidemic treatment, diabetes mellitus, smoking.

Additionally, adjusted for type of CAD (stable vs. ACS).

BACE1-AS Is Associated with the Presence and Severity of CAD and Multiple Diseased Vascular Beds

As shown in Table 1 , the prevalence of ACS and CAD patients significantly increased across BACE1-AS tertiles. Patients with CAD (stable or ACS) had significantly higher levels of BACE1-AS as compared with non-CVD individuals, while increasing BACE1-AS expression was associated with higher odds for CAD presence (OR = 1.72 for CAD presence, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.36–2.17, p < 0.001, Table 2 ). This association remained significant after multivariable analysis, adjusting for the core model (OR = 1.85 for CAD presence, 95% CI: 1.37–2.5, p < 0.001, Table 2 ). BACE1-AS did not differ between stable CAD and ACS patients. In addition, increased levels of BACE1-AS were associated with multivessel CAD (OR = 1.30 for multivessel CAD, 95% CI: 1.031–1.63, p = 0.026), also after multivariable adjustment for the core model and group of CAD (OR = 1.36 for multivessel CAD, 95% CI: 1.06–1.75, p = 0.015, Table 2 ). Similarly, higher BACE1-AS was associated with increased odds for the presence of multiple diseased vascular beds (OR = 1.31 for multiple diseased vascular beds, 95% CI: 1.07–1.61, p = 0.011, after adjustment for the core model) in the non-CVD and stable CAD groups ( Table 2 ).

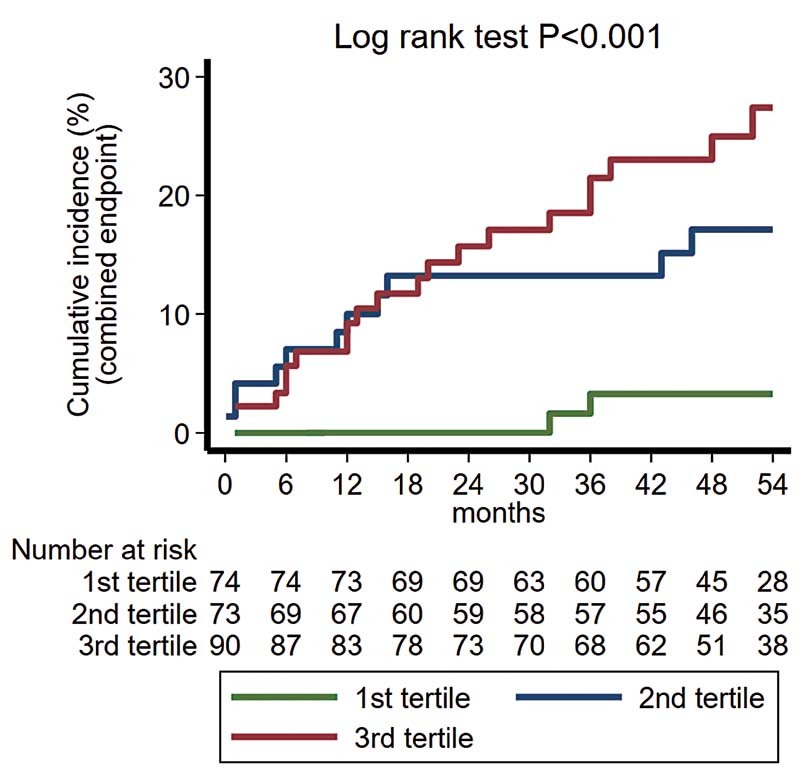

BACE1-AS Expression Levels and Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in High/Very High CVD Risk Patients

Subsequently, we evaluated the prognostic value of BACE1-AS , for the incidence of MACE, in high/very high CVD risk patients, as defined in the Patients and Methods section. From 319 high/very high CVD risk patients at baseline, 70 provided consent only for the cross-sectional arm of the study and 12 were lost to follow-up. Descriptive characteristics of high/very high-risk patients who were followed versus those lost to follow-up are provided in Supplementary Table S1 (available in the online version). In 237 high/very high CVD risk patients, who were followed for a median period of 52 months, 49 MACEs occurred. Descriptive statistics of high/very high-risk patients who were followed are provided in Supplementary Table S2 (available in the online version). This analysis revealed that patients who were classified at higher BACE1-AS tertiles at baseline had increased risk for MACE (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.42 per ascending tertile, 95% CI: 1.39–4.22, p = 0.002, by Cox regression analysis) ( Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S2 [available in the online version]). After adjusting for all significant predictors at univariable level (age, sex, presence of CAD, DM, and hypertension), increased BACE1-AS remained an independent predictor of cumulative incidence of MACE in high CVD risk patients (HR = 1.86 per ascending tertile, 95% CI: 1.011–3.43, p = 0.046).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, acute myocardial infarction, and revascularization procedure) in high/very high CVD risk patients (total N = 237) according to BACE1-AS tertiles, initially defined in the whole population. The number of patients at risk is depicted beneath the graph. BACE1-AS tertiles were derived from the total population. p < 0.001, by log-rank test of equality. HR = 2.42 per ascending tertile (95% CI: 1.39–4.22), p = 0.002, by Cox regression analysis. HR = 1.86 per ascending tertile (95% CI: 1.011–3.43), p = 0.046, after multivariable adjustment for age, gender, presence of coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. BACE1-AS , β secretase antisense RNA; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio.

Single-Cell Sequencing Analysis

To evaluate the presence of BACE1-AS lncRNA and BACE1 mRNA expression in different immune cell subtypes, we performed a retrospective in silico bioinformatics analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data of PBMCs derived from two healthy subjects. 28 The Single Cell Portal database was used to generate t-SNE plots and gene expression plots in different cell types from PBMCs. The t-SNE plots depict nine main clusters in the PBMCs, namely, in order from greatest (9,071 cells) to least (164 cells) abundant: cytotoxic T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD14+ monocytes, B cells, natural killer cells, megakaryocytes, CD16+ monocytes, dendritic cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells ( Supplementary Fig. S3A [available in the online version]). Apart from the megakaryocyte population, all leukocyte subtype cells express BACE1-AS lncRNA and BACE1 mRNA ( Supplementary Fig. S3B , C [available in the online version]). Next, we retrospectively investigated the expression of BACE1-AS lncRNA and BACE1 mRNA in atherosclerotic plaque cell subtypes. Transcriptome data were recovered from the atherosclerotic plaque core and proximally adjacent region of three patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. 30 The Plaqview database 29 was used to visualize the data in two dimensions using the UMAP method. UMAP dimensionality reduction showed that the cells were divided into 11 clusters including B cells, endothelial cells, erythrocytes, fibroblasts, mast cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, pericytes, plasma cells, smooth muscle cells, and T cells. We then assessed the gene expression across these 11 major cell types ( Supplementary Fig. S4A [available in the online version]). Both BACE1-AS lncRNA and BACE1 mRNA were ubiquitously expressed in almost all atherosclerotic plaque cell subtypes. Among the immune cells infiltrating the atherosclerotic plaque, BACE1-AS lncRNA and BACE1 mRNA are expressed in both T-cells and macrophages ( Supplementary Fig. S4B , C [available in the online version]). Interestingly, BACE1-AS / BACE1 transcripts are quite highly expressed in vascular wall cells including endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, encouraging future studies to evaluate the cell-specific role of BACE1-AS in atherosclerosis.

Impact of BACE1-AS Overexpression in Human Aortic Endothelial Cell Transcriptome

To explore a potential mechanism on BACE1-AS action, which could participate in CAD progression, we searched for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) after BACE1-AS overexpression in human aortic endothelial cells. Of note, BACE1-AS was found to be highly expressed in endothelial cells derived from human atherosclerotic plaques obtained from patients undergoing carotid endartectomy ( Supplementary Fig. S4B [available in the online version]). We identified 2094, DEGs, from which 756 are predicted to be involved in atherosclerosis according to the Harmonizome database 31 ( Supplementary Fig. S5A [available in the online version]). To explore the functional characteristics of these 756 atherosclerotic-related genes after overexpression of BACE1-AS , we conducted a gene ontology (GO) analysis. Interestingly, the enrichment analysis of GO annotations to classify DEGs showed that the top 30 GO terms considerably associated with DEGs were “response to cytokine,” “inflammatory response,” “leukocyte migration” “response to hypoxia,” and “response to lipid” ( Supplementary Fig. S5B [available in the online version]). Next, we performed a KEGG pathway enrichment analysis to explore the most enriched pathways among all the 756 DEGs related to atherosclerosis. Our analysis revealed that several inflammation-related modulatory pathways such as NF-kappa B, NOD-like receptor, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling pathway were among the most enriched pathways ( Supplementary Fig. S5C [available in the online version]).

Discussion

The results of this study provide evidence that increased expression of BACE1-AS in PBMCs, an upstream regulatory molecule of Aβ1–40 metabolism, is associated with the presence, extent, and incidence of atherosclerotic disease in humans. These novel findings support the clinical significance of this lncRNA in ASCVD.

Although the role of BACE1-AS in AD as the main regulatory noncoding RNA of Aβ metabolism has been previously reported, 32 its role in ASCVD has not been described. Plasma levels of BACE1-AS are increased in AD patients and may serve as a biomarker for detection of the disease. 33 BACE1-AS silencing improved cognitive function and reduced Aβ deposition in an AD mouse model. 9 Previous studies provide evidence on the link between ASCVD as assessed by CVRF prevalence and age-related dementia. 11 To that end, converging data demonstrate that circulating Aβ1–40 levels are associated with CVRF burden, vascular aging, and atherosclerosis. 14 16 34 35 36 37 In agreement with these findings, we observed that a high CVRF burden and a high estimated ASCVD risk are associated with increased BACE1-AS expression levels. Importantly, BACE1-AS was also independently associated with increased vascular stiffness, a marker of vascular aging, and with IMT, a marker of arterial injury, both of which are associated with ASCVD progression and prognosis. 27 38 These findings are in agreement with recent experimental data showing that BACE1 expression is positively associated with the progression of atherosclerosis and formation of foam cells in an atherosclerosis-prone mouse model 39 and clinical evidence showing the association between circulating Aβ1–40 and accelerated subclinical atherosclerosis. 15 In addition to its association with preclinical disease, BACE1-AS was associated with the presence and severity of clinically overt CAD. These findings provide mechanistic insights into our previous studies showing the association between Aβ1–40 and coronary calcium score, CAD, and ACS. 16 17 The hypothesis of a clinically relevant regulatory role of this noncoding RNA in ASCVD is further supported by its independent association with new incidence of MACE in our group of high CVD risk patients. These new findings support mechanistically previous findings documenting the prognostic value of Aβ1–40 in patients presenting with NSTEMI (non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction). 17 Overall these findings suggest that BACE1-AS interacts with factors predisposing to ASCVD as well as almost the full-spectrum atherosclerosis and vascular aging, supporting its clinical and regulatory role in the Aβ1–40 pathway contributing to human arterial disease.

The exact mechanisms related to the observed association between the BACE1-AS pathway and ASCVD have not been clarified. BACE1-AS / BACE1 is the main regulatory axis of Aβ1–40 production. 8 In our population, we found a strong association between BACE1 and BACE1-AS expression in PBMCs, while increased BACE1-AS expression in PBMCs was associated with Aβ1–40 in plasma. Previous studies have described the association between Aβ1–40 and multiple pathophysiologic processes involved in ASCVD. 7 Peripheral monocytes are significantly involved in the phagocytosis of circulating Αβ1–40, which leads them to acquire a more proinflammatory phenotype. 40 In addition, Aβ1–40 exposure promotes monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells and migration in vascular wall, as well as hypersecretion of inflammatory mediators. 7 41 Aβ1–40-stimulated monocytes differentiate in tissue macrophages, which secrete inflammatory mediators, phagocytose lipoproteins, and form foam cells in an accelerated manner. 7 Endothelial cells respond to Aβ1–40 exposure by acquiring an activated phenotype accompanied by increased expression of adhesion molecules, decreased nitric oxide production, and increased release of proinflammatory cytokines. 7 In addition, endothelial exposure to Αβ1–40 results in vascular aging by inhibiting telomerase activity leading to telomere shortening, 7 as well as endothelial cell injury and apoptosis. 7 Moreover, in vitro evidence demonstrated that Aβ1–40 decreases cyclic guanosine monophosphate production in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), with subsequent altered contraction and relaxation properties, 7 stimulates VSMC-induced inflammatory response, de-differentiation, and cell death. 42 43 These effects may at least partly explain the accumulating clinical data, indicating that increased circulating levels of Aβ1–40 are associated with multiple CVRFs, arterial stiffening, and the presence of atherosclerosis in multiple vascular beds, as well as accelerated progression of aortic stiffening and atherosclerosis. 14 15 We have previously reported that circulating Aβ1–40 has an independent prognostic and reclassification value for mortality and adverse cardiovascular events in stable CAD and NSTE-ACS patients. 16 17 These findings explain mechanistically the involvement of Αβ1–40 in ASCVD and support its clinical utility.

To shed more light on the potential mechanisms triggered by the increased expression of BACE1-AS in ASCVD, we analyzed the human aortic endothelial transcriptome expression after overexpression of BACE1-AS lncRNA. We identified 756 differentially deregulated genes that were affected by BACE1-AS lncRNA overexpression and which are also potentially related to atherosclerosis according to the Harmonizome database. Further sub-analysis of atherosclerosis-related BACE1-AS lncRNA differentially regulated genes revealed pathways related to inflammation, including NF-kappa B, NOD-like receptor, and TNF signaling pathway. Interestingly, there is evidence in the literature of a proinflammatory role of BACE1 and BACE1-AS ( Supplementary Table S3 [available in the online version]). Together these data support the notion that BACE1-AS may play a direct role in vascular inflammation observed during the formation of atherosclerotic plaque.

Complementary to the above, experimental evidence suggests that BACE1-AS might promote atherosclerotic disease by acting as a competing endogenous RNA on other atheroprotective microRNAs (miRNAs). 32 44 45 46 47 A detailed list of miRNAs sponged by BACE1-AS and their mostly protective association with ASCVD is provided in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5 (available in the online version). Notably, some of these miRNAs are negative regulators of BACE1 expression ( Supplementary Table S4 [available in the online version]). Therefore, BACE1-AS increases BACE1 expression through two distinct pathways: either by directly binding and stabilizing BACE1 mRNA or by sponging other miRNAs, such as mir-29, mir-107, mir-124, mir-485, and mir-761, which in turn normally suppress BACE1 mRNA translation. Since BACE1-AS lncRNA sequesters these miRs, it may rescind their protective role against ASCVD.

Based on the above evidence, BACE1-AS may affect both amyloid-dependent and amyloid-independent pathways of inflammatory responses in ASCVD. To that end, we found that BACE1-AS was associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of Aβ1–40 levels and BACE1 expression. The hypothesis of nonamyloidogenic mechanisms associated with BACE1-AS merits further investigation. Overall, our findings, combined with these data, suggest a crucial role of BACE1-AS in the process of atherosclerosis, acting by complex multilevel molecular mechanisms, which need to be further elucidated.

The present study has certain limitations. Given the observational design of the study, our results cannot prove causality. Nevertheless, these findings are hypothesis-generating and support further experimental research on the causative role of BACE1-AS in ASCVD. Furthermore, no serial measurements of BACE1-AS expression in PBMCs were available to evaluate any changes in BACE1-AS expression in the acute phase of ACS and the following days. In addition, BACE1-AS lncRNA expression was not determined in PBMC subtypes. To investigate the cell-specific expression of BACE1-AS lncRNA, we performed an in silico retrospective single-cell analysis from publicly available single-cell RNA sequencing data derived (1) from PBMCs derived from two healthy individuals and (2) from human atherosclerotic plaque cells derived from three patients undergoing a carotid endarterectomy due to symptomatic or significant carotid artery disease. This analysis revealed that, among the subtypes of PBMCs, BACE1-AS was found to be present in almost all PBMC subtypes including both lymphocytes (both B cells and T cells) and CD14+ monocytes. Similar results were observed also for the BACE1 mRNA. Interestingly, only a small proportion of the PBMC subtypes was positive for BACE1-AS lncRNA/ BACE1 mRNA, indicating that both molecules are probably rather lowly expressed in healthy individuals. We also analyzed the leukocyte subtypes present in human atherosclerotic plaques derived from three patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. BACE1-AS lncRNA and BACE1 mRNA were present in almost all plaque cell subtypes including T cells and macrophages as well as endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells. Future studies are needed to investigate the cell-specific role of BACE1-AS lncRNA in the development and progression of atherosclerosis and the underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, the current study adds new translational evidence showing that BACE1-AS , a pivotal regulatory molecule of Aβ1–40 metabolism, is associated with the continuum of human atherosclerosis. These results provide insight into in vivo modulatory mechanisms associated with the well-described proatherosclerotic and proinflammatory effects of Aβ1–40. 7 Thus, the present findings encourage future studies to investigate the causative role of the BACE1-AS/BACE1 pathway in the development of atherosclerosis and the potential clinical utility of BACE1-AS in ASCVD. Considering that the measurement of novel biomarkers in the whole blood would be a faster option to bring a novel biomarker in the daily clinical practice, future studies are warranted to confirm our PBMC-derived findings in whole blood.

Funding Statement

Funding This work was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation DFG (SFB834 B12, project number 75732319) to K. Stellos. K. Stellos was also supported by a European Research Council (ERC) grant under the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (MODVASC, grant agreement No. 759248). K. Stamatelopoulos was supported by institutional funding. F.M. was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (“Ricerca Corrente” and RF-2019-12368521), EU COVIRNA # 101016072, Telethon-Italy n. GGP19035, AFM-Telethon n. 23054.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Note

The graphical abstract was created using templates from Servier Medical Art (smart.servier.com).

Author Contributions

D.B., I.M., S.T-.C. and K. Stamatelopoulos contributed to writing of the manuscript. N.I.V., S.T-.C., M.S., K. Sopova, and A.G. performed RNA analysis. G.G. and K. Stamatelopoulos did the statistical analyses. G.M., A.M., C.K., A.L., and D.D. were involved in participants' recruitment and data collection. F.B., K. Stellos, K. Stamatelopoulos, and F.M. conceptualized the study and proofread the manuscript. K. Stellos and K. Stamatelopoulos coordinated the study.

Equal first author contribution.

Equal senior author contribution.

What is known about this topic?

The noncoding antisense transcript for beta-secretase-1 ( BACE1-AS ) is a long noncoding RNA with a pivotal role in the regulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ).

Circulating Aβ1–40 is an independent prognostic factor for mortality in atherosclerotic and cardiovascular diseases.

Whether BACE1-AS is associated with entities of ASCVD remains unknown.

What does this paper add?

BACE1-AS is associated with increased BACE1 expression and circulating Αβ1–40.

Increased expression of BACE1-AS is associated with (1) increased cardiovascular risk, (2) aortic stiffness, and (3) presence and extent of atherosclerosis.

BACE1-AS is associated with increased risk for adverse cardiovascular event.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Joseph P, Leong D, McKee M. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease, part 1: the epidemiology and risk factors. Circ Res. 2017;121(06):677–694. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.308903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaé N, Heumüller A W, Fouani Y. Long non-coding RNAs in vascular biology and disease. Vascul Pharmacol. 2019;144:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laina A, Gatsiou A, Georgiopoulos G. RNA therapeutics in cardiovascular precision medicine. Front Physiol. 2018;9:953. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu D, Thum T. RNA-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(11):661–674. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fasolo F, Di Gregoli K, Maegdefessel L, Johnson J L. Non-coding RNAs in cardiovascular cell biology and atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115(12):1732–1756. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali Faghihi M, Modarresi F, Khalil A M. Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer's disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase. Nat Med. 2008;14(07):723–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stakos D A, Stamatelopoulos K, Bampatsias D. The Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta hypothesis in cardiovascular aging and disease: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(08):952–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li F, Wang Y, Yang H. The effect of BACE1-AS on β-amyloid generation by regulating BACE1 mRNA expression. BMC Mol Biol. 2019;20(01):23. doi: 10.1186/s12867-019-0140-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Zhao H, Wu Q, Xu W, Xia M. Knockdown of BACE1-AS by siRNA improves memory and learning behaviors in Alzheimer's disease animal model. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(03):2080–2086. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(07):689–701. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottesman R F, Albert M S, Alonso A. Associations between midlife vascular risk factors and 25-year incident dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1246–1254. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deschaintre Y, Richard F, Leys D. Treatment of vascular risk factors is associated with slower decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73(09):674–680. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b59bf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roher A E, Tyas S L, Maarouf C L. Intracranial atherosclerosis as a contributing factor to Alzheimer's disease dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(04):436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.08.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatelopoulos K, Pol C J, Ayers C. Amyloid-beta (1–40) peptide and subclinical cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(09):1060–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambrinoudaki I, Delialis D, Georgiopoulos G. Circulating amyloid beta 1-40 is associated with increased rate of progression of atherosclerosis in menopause: a prospective cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121(05):650–658. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stamatelopoulos K, Sibbing D, Rallidis L S. Amyloid-beta (1-40) and the risk of death from cardiovascular causes in patients with coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(09):904–916. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamatelopoulos K, Mueller-Hennessen M, Georgiopoulos G. Amyloid-β (1-40) and mortality in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(12):855–865. doi: 10.7326/M17-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greco S, Zaccagnini G, Fuschi P. Increased BACE1-AS long noncoding RNA and β-amyloid levels in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(05):453–463. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction . Thygesen K, Alpert J S, Jaffe A S. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(18):2231–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piepoli M F, Hoes A W, Agewall S. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315–2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumann F J, Sechtem U, Banning A P. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(03):407–477. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Standardized Data Collection for Cardiovascular Trials Initiative (SCTI) . Hicks K A, Mahaffey K W, Mehran R. 2017 cardiovascular and stroke endpoint definitions for clinical trials. Circulation. 2018;137(09):961–972. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ter Avest E, Stalenhoef A FH, de Graaf J. What is the role of non-invasive measurements of atherosclerosis in individual cardiovascular risk prediction? Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112(10):507–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon A, Jérôme G, Gilles C, Jean-Louis M, Jaime L.Intima-media thickness: a new tool for diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular risk J Hypertens 20022002159–169.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gatsiou A, Georgiopoulos G, Vlachogiannis N I. Additive contribution of microRNA-34a/b/c to human arterial ageing and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2021;327:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdullah L, Paris D, Luis C.The influence of diagnosis, intra- and inter-person variability on serum and plasma Abeta levels Neurosci Lett 2007428(2–3):53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mareti A, Kritsioti C, Georgiopoulos G. Cathepsin B expression is associated with arterial stiffening and atherosclerotic vascular disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27(19):2288–2291. doi: 10.1177/2047487319893042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding J, Adiconis X, Simmons S K. Systematic comparison of single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-sequencing methods. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(06):737–746. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0465-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma W F, Hodonsky C J, Turner A W. Enhanced single-cell RNA-seq workflow reveals coronary artery disease cellular cross-talk and candidate drug targets. Atherosclerosis. 2022;340:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alsaigh T, Evans D, Frankel D.Decoding the transcriptome of atherosclerotic plaque at single-cell resolutionAccessed August 17, 2022 at:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.03.968123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Rouillard A D, Gundersen G W, Fernandez N F. The harmonizome: a collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine knowledge about genes and proteins. Database (Oxford) 2016;2016:baw100. doi: 10.1093/database/baw100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng T, Ni H, Yu Y. BACE1-AS prevents BACE1 mRNA degradation through the sequestration of BACE1-targeting miRNAs. J Chem Neuroanat. 2019;98:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng L, Liao Y T, He J C. Plasma long non-coding RNA BACE1 as a novel biomarker for diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. BMC Neurol. 2018;18(01):4. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-1008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Zhu H, Wallack M. Age and its association with low insulin and high amyloid-β peptides in blood. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(01):129–137. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabelle A, Schraen S, Gutierrez L A. Plasma β-amyloid 40 levels are positively associated with mortality risks in the elderly. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(06):672–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayes-Genis A, Barallat J, de Antonio M. Bloodstream amyloid-beta (1-40) peptide, cognition, and outcomes in heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2017;70(11):924–932. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janelidze S, Stomrud E, Palmqvist S. Plasma β-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease and vascular disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26801. doi: 10.1038/srep26801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Touboul P J, Hennerici M G, Meairs S. Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness and plaque consensus (2004-2006-2011). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, Brussels, Belgium, 2006, and Hamburg, Germany, 2011. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34(04):290–296. doi: 10.1159/000343145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen L, Huang Y, Guo J, Li Y. Expression of Bace1 is positive with the progress of atherosclerosis and formation of foam cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;528(03):440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.05.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo H, Zhao Z, Zhang R. Monocytes in the peripheral clearance of amyloid-β and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;68(04):1391–1400. doi: 10.3233/JAD-181177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert J, Button E B, Stukas S. High-density lipoproteins suppress Aβ-induced PBMC adhesion to human endothelial cells in bioengineered vessels and in monoculture. Molecular Neurodegener. 2017;12(01):60. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0201-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vromman A, Trabelsi N, Rouxel C, Béréziat G, Limon I, Blaise R. β-Amyloid context intensifies vascular smooth muscle cells induced inflammatory response and de-differentiation. Aging Cell. 2013;12(03):358–369. doi: 10.1111/acel.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blaise R, Mateo V, Rouxel C. Wild-type amyloid beta 1-40 peptide induces vascular smooth muscle cell death independently from matrix metalloprotease activity. Aging Cell. 2012;11(03):384–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Y, Ge Y, Liu Q. LncRNA BACE1-AS promotes autophagy-mediated neuronal damage through the miR-214-3p/ATG5 signalling axis in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 2021;455:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Wang W N, Xu S B. MicroRNA-214-3p: a link between autophagy and endothelial cell dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2018;222(03) doi: 10.1111/apha.12973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Z F, Ji X L, Gu J, Wang X Y, Ding L, Zhang H. microRNA-107 protects against inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress of vascular endothelial cells via KRT1-dependent Notch signaling pathway in a mouse model of coronary atherosclerosis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(07):12029–12041. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Y, Ponnusamy M, Zhang L. The role of miR-214 in cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;816:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.