Abstract

Despite the identification of a growing number of genetic risk loci for substance use traits (SUTs), the impact of these loci on protein abundance and the potential utility of relevant proteins as therapeutic targets are unknown. We conducted a proteome-wide association study (PWAS) in which we integrated human brain proteomes from discovery (Banner; N = 152) and validation (ROSMAP; N = 376) datasets with genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics for 4 SUTs. The 4 samples comprised GWAS of European-ancestry individuals for smoking initiation [Smk] (N = 1,232,091), alcohol use disorder [AUD] (N = 313,959), cannabis use disorder [CUD] (N = 384,032), and opioid use disorder [OUD] (N = 302,585). We conducted transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) with human brain transcriptomic data to examine the overlap of genetic effects at the proteomic and transcriptomic levels and characterize significant genes through conditional, colocalization, and fine-mapping analyses. We identified 27 genes (Smk = 21, AUD = 3, CUD = 2, OUD = 1) that were significantly associated with cis-regulated brain protein abundance. Of these, 7 showed evidence for causality (Smk: NT5C2, GMPPB, NQO1, RHOT2, SRR and ACTR1B; and AUD: CTNND1). Cis-regulated transcript levels for 8 genes (Smk = 6, CUD = 1, OUD = 1) were associated with SUTs, indicating that genetic loci could confer risk for these SUTs by modulating both gene expression and proteomic abundance. Functional studies of the high-confidence risk proteins identified here are needed to determine whether they are modifiable targets and useful in developing medications and biomarkers for these SUTs.

Subject terms: Diseases, Genetics

Introduction

Substance use traits (SUTs), including smoking initiation (Smk), alcohol use disorder (AUD), cannabis use disorder (CUD), and opioid use disorder (OUD), are highly prevalent and leading causes of morbidity and mortality [1–3]. An estimated 40–60% of the risk of SUTs is attributable to genetic factors [4–6]. Recent large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of SUTs have implicated underlying biological systems [7–10]. Despite the growing success of GWAS in identifying associated risk polymorphisms, many of the identified variants are intronic or intergenic [11] and exert only small phenotypic effects, suggesting that they are mediated by the regulation of transcription.

Recent efforts to understand how genetic variation influences gene transcription and contributes to disease have led to the development of analytic frameworks such as functional summary-based imputation (FUSION) [12], S-PrediXcan [13], summary data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) [14], and Coloc [15]. These frameworks utilize a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) approach, integrating external gene expression reference data and GWAS results to prioritize genes whose cis-regulated expression is associated with disease phenotypes.

To facilitate the identification of genes with cis-regulated expression profiles, TWASs have been conducted for cigarette smoking [11], cocaine dependence [11], problematic alcohol use (PAU) [8], and OUD [10]. Although these TWASs shed light on potential mechanisms through which genetic loci associated with SUTs exert their effects, the evidence they provide of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) effects are at the level of messenger RNA (mRNA), rather than protein abundance. Genetic variation can influence protein abundance by altering the rate and stability of gene expression [16], though it is an empirical question whether the identified genetic loci exert their effects on SUTs by modulating protein abundance in the brain. The importance of this question lies in the fact that proteins, as the final products of gene expression, are the main functional components of cells and biological processes [17], and comprise most drug targets and biomarkers [17, 18].

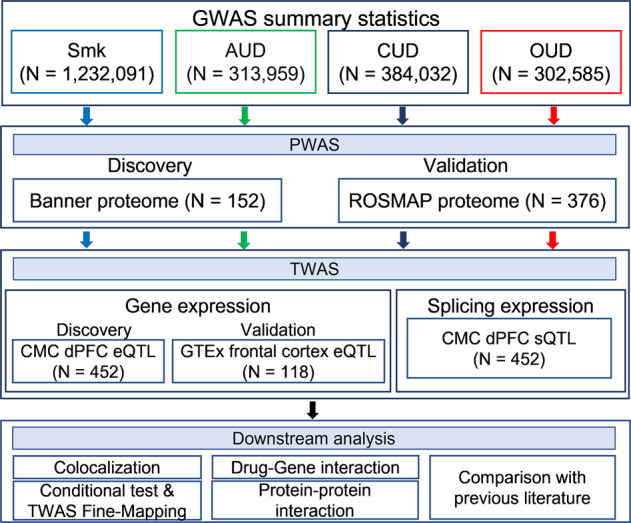

The current study examines whether loci identified through GWAS contribute to the pathogenesis of SUTs by modulating protein abundance. We applied an integrative proteome-wide association study (PWAS) approach that combines genetic data from 4 large GWASs of SUTs [7–10] with 2 independent human brain proteomic datasets (Banner [19] and ROSMAP [20]) derived from brain dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dPFC). To compare the effects of risk variants at both the proteomic and transcriptomic levels, we also performed TWAS using the CommonMind Consortium (CMC) dPFC [21] and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) v7 frontal cortex [22] datasets. See Fig. 1 for a study overview.

Fig. 1. Overview of the study.

GWAS summary statistics included in the study were based on 4 substance use traits (SUT): smoking initiation (Smk), alcohol use disorder (AUD), cannabis use disorder (CUD) and opioid use disorder (OUD). For PWAS, human brain proteomes from Banner (discovery) and ROSMAP (validation) datasets were integrated with each set of GWAS summary statistics. TWAS based on brain eQTL datasets from discovery (CommonMind Consortium - CMC) and validation (Genotype-Tissue Expression - GTEx) datasets was conducted for each SUT. TWAS splicing expression analysis (CMC - sQTL) was also performed for all 4 traits. N denotes the actual sample size of studies included in each analysis. Colocalization analysis was based on nominally significant proteins and transcripts for Smk and proteins for AUD. All significant proteins (after Bonferroni correction) were used as input for drug-gene interaction analysis for all 4 traits. Only proteome-wide significant proteins for Smk and AUD were included for protein-protein interaction analysis.

Methods

Genome-wide association studies summary statistics

We selected the largest GWASs of SUTs available as of July 2021; all were of European ancestry (EUR) to match the proteomic datasets. Summary statistics were derived from n = 1,232,091 for Smk [7]; n = 313,959 for AUD [8]; n = 384,032 for CUD [9]; and n = 302,585 for OUD [10]. Sample demographics and methods for phenotyping, data processing, and statistical analyses from the original articles [7–10] are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Human brain pQTL data

We obtained human brain proteomic data from the study by Wingo et al. [23, 24], in which human protein abundance was quantified in the dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex (dPFC) of post-mortem brain tissues from 152 (Banner dataset) [19] and 376 (ROSMAP dataset) [20] EUR participants. Characterizing genetic control of the proteome in these human brain datasets identified 1,139 and 1,475 protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) (i.e., protein weights) in the Banner and ROSMAP datasets, respectively [23, 24], which were downloaded from 10.7303/syn23627957. Sample demographics, proteomic sequencing, quality control, and normalization from Wingo et al. [23, 24] are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Proteome-wide association analysis

To identify proteins whose genetically regulated expression is associated with SUTs, we performed PWAS analyses by integrating GWAS summary statistics of SUTs and pQTLs from discovery (Banner) and validation (ROSMAP) datasets using the FUSION pipeline (http://gusevlab.org/projects/fusion/) [12]. FUSION employs 5-fold predictive models (top1, GBLUP, LASSO, Elastic Net, BSLMM) to compute the combined effect of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on protein expression weights. The model with the largest cross-validation R2 was selected for downstream analyses. PWAS association statistics were Bonferroni corrected based on the number of proteins in the analysis (see footnote in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Results of the PWAS of smoking initiation.

| Gene | Chr | Banner | ROSMAP | Validated | Coloc (PP > .8) | Conditionally independent | Overlap with TWAS eQTL | Overlap with TWAS sQTL | TWAS FOCUS (PIP > .5) | Novele | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWAS Z | PWAS pa | PWAS Z | PWAS pb | |||||||||

| NT5C2 | 10 | 7.29 | 3.17E-13 | 7.55 | 4.42E-14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| ARPC1B | 7 | 5.94 | 2.83E-09 | No | No | |||||||

| HEBP1c | 12 | −5.71 | 1.14E-08 | -0.68 | 4.94E-01 | No | No | No | No | |||

| GMPPB | 3 | 5.62 | 1.89E-08 | 5.01 | 5.39E-07 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| NQO1 | 16 | −5.32 | 1.05E-07 | -5.16 | 2.42E-07 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| SRR | 17 | −5.04 | 4.73E-07 | -5.36 | 8.45E-08 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| RHOT2 | 16 | 4.94 | 7.74E-07 | 5.64 | 1.71E-08 | Yes | Yesd | Yes | No | |||

| ACTR1B | 2 | −4.92 | 8.68E-07 | -4.8 | 1.61E-06 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |||

| BTN3A3c | 6 | −4.91 | 8.93E-07 | -3.25 | 1.16E-03 | No | No | No | Yes | |||

| WIPI2c | 7 | 4.22 | 2.43E-05 | -2.89 | 0.00375 | No | No | No | No | |||

| BTN2A1 | 6 | −4.21 | 2.59E-05 | 4.55 | 5.44E-06 | Yes | No | No | No | |||

| GFM1 | 3 | −4.18 | 2.95E-05 | No | ||||||||

| MAP1LC3A | 20 | −4.1 | 4.13E-05 | No | ||||||||

| C10orf32 | 10 | -6.91 | 4.77E-12 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | ||||

| TYW5 | 2 | 5.24 | 1.57E-07 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |||||

| MCTP1 | 5 | -4.86 | 1.19E-06 | No | Yes | Yes | No | |||||

| PLD1 | 3 | -4.67 | 3.05E-06 | No | ||||||||

| RFT1 | 3 | 4.66 | 3.19E-06 | Yes | ||||||||

| NAT6 | 3 | 4.64 | 3.54E-06 | No | Yes | Yes | No | |||||

| AAGAB | 15 | 4.28 | 1.83E-05 | No | ||||||||

| PRKCDc | 3 | 2.06 | 3.94E-02 | 4.25 | 2.10E-05 | No | Yes | No | No |

Chr Chromosome, PWAS proteome-wide association study, pQTL protein quantitative trait loci, eQTL expression quantitative trait loci, sQTL splicing quantitative trait loci, ROSMAP Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project.

aBonferroni correction p-value for Banner proteome-wide significant (PWS) genes was set at 4.36E-5.

bBonferroni correction p-value for ROSMAP PWS genes was set at 3.39E-5.

cGenes that were PWS one human brain reference dataset and nominally significant (p < 0.05) in other brain proteome reference.

dGenes colocalized in one human brain reference dataset.

eGenes are novel compared with GWAS if > 1 MB away from a lead GWAS variant (R2 < 0.1).

Human eQTL data

Human brain transcriptome data, used as expression reference panels, were obtained from the CMC [21] and GTEx frontal cortex v7 [12, 22]. The CMC dataset, which consists of transcriptomic profiles for gene-level (eQTL, n = 452) and intron-level (splicing–sQTL, n = 452) expression [21] in dPFC and GTEx frontal cortex weights (eQTL, n = 118) were downloaded from the FUSION website (http://gusevlab.org/projects/fusion/) [12].

To examine the association between the cis component of gene expression and SUTs, we performed a transcriptome-wide association analysis (TWAS) using the FUSION package [12]. TWAS was performed using gene and splicing expression profiles measured in adult dPFC and gene expression profiles from frontal cortex. For both PWAS and TWAS, we applied the default parameters in FUSION. To explore whether there was significant enrichment in the genes identified in the PWAS and TWAS, we created proteome-wide significant (PWS) and transcriptome-wide significant (TWS) gene sets. For each gene set, we created a 2-by-2 table to compare the number of listed genes belonging to the gene set to the number of non-members and tested the significance of over-representation using a binomial approximation (p < 0.05) [25].

Colocalization of PWAS and TWAS associations

To explore plausible causal relationships between GWAS variants and proteome- or transcriptome-wide associations, we performed colocalization analysis using the coloc R package (version 3.2-1) [15] in FUSION [12]. We used the FUSION parameter (-coloc_P 0.05) for inclusion of nominally significant proteins/genes (at p < 0.05) and performed colocalization based on the GWAS and pQTL (ROSMAP and Banner) [23, 24], eQTL (CMC and GTEx) [21, 22] and sQTL (CMC) [21] data. A posterior colocalization probability (PP) of 80% was used to denote a shared causal signal.

Conditional analysis and TWAS fine mapping

Conditional analyses were performed for PWS and TWS genes using FUSION [12] to determine whether multiple gene-trait associations within given risk loci are independent after adjusting for the predicted expression of other genes in the region. Genes that overlapped within the 1.5-Mb boundary were merged into a single locus. This allowed us to estimate the extent to which functional associations identified in the PWAS/TWAS explain the GWAS signals within the same locus. The “variance explained” was calculated using the formula: R2 = 1-χ2 conditioned GWAS association / χ2 unconditioned GWAS association [12, 26]. To identify genes within regions of association that are likely causal, we performed TWAS fine-mapping using FOCUS [27]. A posterior inclusion probability (PIP) > 0.5 indicated which genes within a region are most likely causal.

Drug-gene interaction

We examined interactions of proteins identified in the PWAS with prescription drugs using the Drug Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb) v3.0 (https://www.dgidb.org) [28]. We categorized each identified prescription drug using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classifications obtained from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomics (KEGG: https://www.genome.jp/kegg/drug/).

Protein-protein interaction

We used STRING database v11.0 [29] to assess whether PWAS genes were enriched for direct protein-protein interactions (PPIs) with discovery and validation PWS genes for Smk and AUD as input. STRING reports the confidence level for observed PPI as follows: low confidence: <0.4; medium: 0.4–0.7; high: >0.7. We used a STRING cut-off score >0.4 to define PWS genes within the observed PPI network as having the highest degree of network connections and a whole genome reference model in STRING to determine whether the number of identified PPIs was significantly enriched.

Comparison with previous literature

Using MAGMA gene-based association analysis and FUMA functional gene mapping analysis [30], we explored whether the PWS and TWS genes for the 4 SUTs were associated in the corresponding GWAS. For each GWS independent lead SNP, we also determined whether any gene in the nearby region (within a 1-Mb window) was associated with any SUT in the original GWAS using other gene-based analyses (e.g., DEPICT, PASCAL). Lastly, we compared our findings with other literature that (a) examined differentially expressed genes/proteins in the postmortem dPFC of subjects with an SUT [31–34] (b) predicted gene/protein expression in the dPFC (via TWAS and S-PrediXcan) for the corresponding SUTs [8–11] or (c) were identified by TWAS-hub (http://twas-hub.org/) [35]. Genes/proteins not previously reported in the GWAS and PWAS/TWAS are considered “novel”.

For PWS and TWS genes that were detected in SUT GWAS and associated TWAS, we explored associations with psychiatric and other brain-related traits using the GWAS catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/). To determine whether there were shared regulatory architectures underlying susceptibility, we also compared our findings with PWAS and TWAS of other psychiatric [12, 23, 24, 36–38] and neuroimaging traits [39].

Results

PWAS identifies brain proteins related to genetic risk for Smk and other SUTs

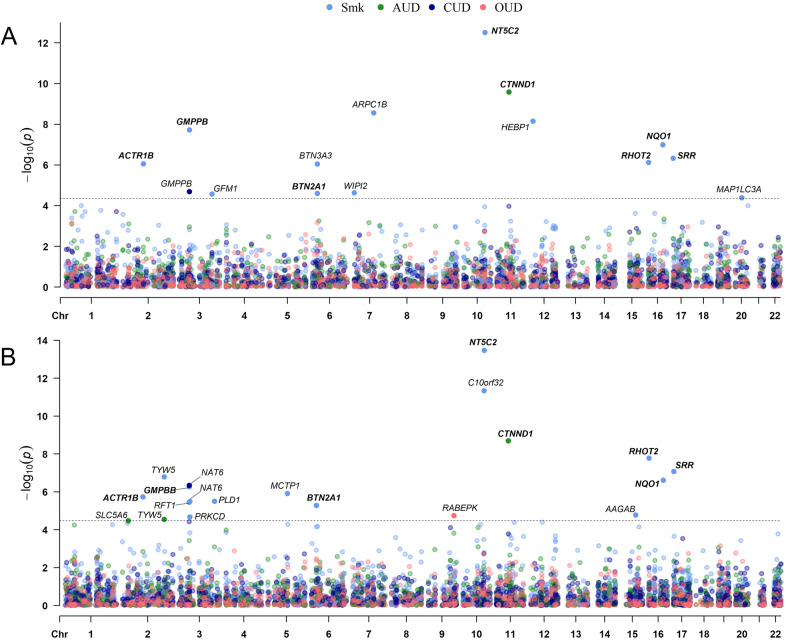

Using the FUSION pipeline to integrate pQTL and GWAS results to identify proteins whose abundance is correlated with genetic risk for the 4 SUTs [7–10], in the discovery stage (using the Banner dataset) we identified 13 proteome-wide significant (PWS) genes for Smk (Table 1, Fig. 2A) and 1 PWS gene each for AUD and CUD (Supplementary Table 2; Fig. 1A). No gene was PWS for OUD in the Banner dataset (Fig. 2A). Using the ROSMAP dataset, we identified 15 PWS genes for Smk (Table 1, Fig. 1B), 3 PWS genes for AUD (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 2B), and 1 PWS gene each for CUD and OUD (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. PWAS identified 27 genes and replicated 6 genes for substance use traits.

A Manhattan plot for smoking initiation (Smk), alcohol use disorder (AUD), cannabis use disorder (CUD) and opioid use disorder (CUD) in the discovery proteome dataset. B Manhattan plot for Smk, AUD, CUD and CUD in the validation proteome dataset. Each dot on the x-axis denotes a gene and on the y-axis the strength of association (-log10 p-value). Proteome-wide significance level for discovery dataset; Bonferroni corrected p < 4.36 × 10−5 and validation; Bonferroni corrected p < 3.39 × 10−5. Validated genes are in bold letters.

We next compared the PWS genes implicated in the discovery and validation stages for Smk, AUD, and CUD. Of the 13 high-confidence Smk PWS genes identified in the discovery dataset (Table 1, Fig. 2A), 7 were PWS (NT5C2, GMPPB, NQO1, SRR, RHOT2, ACTR1B, and BTN2A1) and 2 (BTN3A3 and WIPI2) were nominally significant in the validation dataset (Table 1). The gene identified for AUD in the discovery dataset (CTNND1) was also PWS in the validation dataset (Supplementary Table 2) and the gene (GMPPB) that was PWS in the discovery cohort for CUD was nearly PWS (p = 3.83 × 10−5) in the validation dataset (Supplementary Table 2).

In addition to the validated genes, 12 SUT genes were PWS in the ROSMAP dataset only, including 8 genes for Smk (Table 1, Fig. 2B), 2 genes for AUD, and 1 gene each for CUD and OUD (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 2B). Of the 12 SUT risk genes identified in the validation stage, 1 was nominally significant for Smk (PRKCD, p = 3.94 × 10−2) (Tables 1) and 1 for AUD (SLC5A6, p = 7.92 × 10−4) (Supplementary Table 2) in the discovery stage. Thus, by combining 2 independent human brain proteomic and SUT GWAS datasets, we identified 27 potential SUT risk loci through their effects on brain proteomic abundance.

PWAS and TWAS overlap reveals high-confidence genes associated with SUT risk

To identify SUT PWS risk genes with evidence of transcriptional regulation, we examined the extent of overlap at the protein and transcript levels. Specifically, we performed eQTL- and sQTL-based TWAS, followed by an analysis of the overlap between the TWS and PWS genes. For the discovery TWAS, we integrated SUT GWAS summary statistics [7–10] and CMC dPFC eQTL datasets [21]. After Bonferroni correction, we detected 48 genes (38 for Smk, 6 for AUD, 2 for CUD, and 2 for OUD) whose cis-regulated expression was significantly associated with SUTs (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 1A–D). To validate these results, we also conducted TWAS using the GTEx frontal cortex eQTL dataset [22], which identified 50 genes (42 for Smk, 4 for AUD, 2 for CUD, and 2 for OUD) with TWS associations (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 2A–D).

Notably, 12 risk genes for Smk (AS3MT, C10orf32, CPSF4, SFMBT1, SRR, ITIH4, TYW5, GPX1, CCDC88B, HYAL3, CNTROB, and NAT6) from the discovery stage also showed TWS associations in the validation stage (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 2B). For CUD, 2 TWS genes (HYAL3 and NAT6) were validated (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 2B) while no TWS gene was validated for AUD or OUD (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 2C, D).

We next compared the validated TWS eQTL genes with PWS genes (from both the discovery and validation stages) to identify significant overlap in SUT risk genes. For Smk, 4 of 21 genes (SRR, TYW5, C10orf32, and NAT6) that were PWS were confirmed by TWAS (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 3A) and shown to have significant overlap (binomial test p = 3.58 × 10−6). NAT6, one of the 2 PWS genes for CUD (Supplementary Table 2) was confirmed by TWAS (Supplementary Table 3). We did not run the binomial test for CUD due to the small number of genes. No PWS gene was supported by TWAS for AUD (Supplementary Fig. 3B) or OUD (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

At the level of splicing, we detected significant overlap between TWS sQTL genes and PWS genes for Smk (binomial test: p = 2.2 × 10−16; NT5C2, NQO1, and MCTP1) (Table 1, Supplementary Table 4). No overlapping genes were identified for AUD, CUD, or OUD.

In summary, TWAS provided substantial evidence linking Smk to expression changes in SRR, TYW5, C10orf32, and NAT6, and splicing of NT5C2, NQO1, and MCTP1.

Colocalization of PWAS and TWAS genes

We explored whether there was a causal effect on SUTs of the validated genes in the proteomic (7 for Smk and 1 for AUD) and transcriptomic (7 for Smk and 2 for CUD) analyses. Colocalization analysis showed strong causal evidence for Smk in 6 PWS genes (NT5C2, GMPPB, NQO1, RHOT2, SRR, and ACTR1B) and 6 TWS eQTL genes (AS3MT, TYW5, CCDC88B, CNTROB, SRR and C10orf32) (coloc posterior probability (PP4) ≥ 80%; Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). We also found evidence of colocalization for the validated AUD PWS gene (CTNND1) (Supplementary Table 8) and the CUD TWS (NAT6 and HYAL3) genes (PP4 ≥ 80%; Supplementary Table 9). Thus, the same risk variants may drive the associations between SUTs and both PWAS (for AUD and Smk) and TWAS eQTL (for CUD and Smk). No TWS sQTL genes were causal for Smk (Supplementary Table 7).

Conditional analysis and TWAS fine mapping

To capture independent significant signals in the PWAS and TWAS, we conducted conditional analyses using FUSION [12]. Of the 27 PWS genes, 25 were independently significant and 2 marginally significant (Supplementary Table 10). Validated proteins with strong colocalization evidence in Smk (NT5C2, GMPPB, NQO1, RHOT2, SRR, and ACTR1B) and AUD (CTNND1) remained independently associated. Conditional analyses also showed that expression changes in these 7 proteins explained most of the gene-trait signals of their loci in both the discovery and validation datasets (Supplementary Table 10).

We also observed multiple TWS genes residing within shared loci in specific genomic regions: 30 in the eQTL discovery dataset (23 for Smk, 4 for AUD, 1 for CUD and 2 for OUD), 31 in the eQTL validation dataset (25 for Smk, 3 for AUD, 1 for CUD and 2 for OUD) (Supplementary Table 11) and 28 in the sQTL dataset (Supplementary Table 12). Of the 8 validated and colocalized TWS genes (6 for Smk and 2 for CUD), 5 (4 for Smk and 1 for CUD) were independently associated (Supplementary Table 12), including 2 (SRR and TWY5) with evidence of overlap at the proteomic level (Table 1).

Using FOCUS [27] for TWAS fine-mapping, we identified 28 eQTLs and 13 sQTLs with PIP > 0.5 (Supplementary Table 13). Of these, 3 genes (SRR, CNTROB, and CCDC88B) were supported by colocalization analysis, confirming that they are likely causal for SUT risk.

Drug-gene and Protein-protein interaction

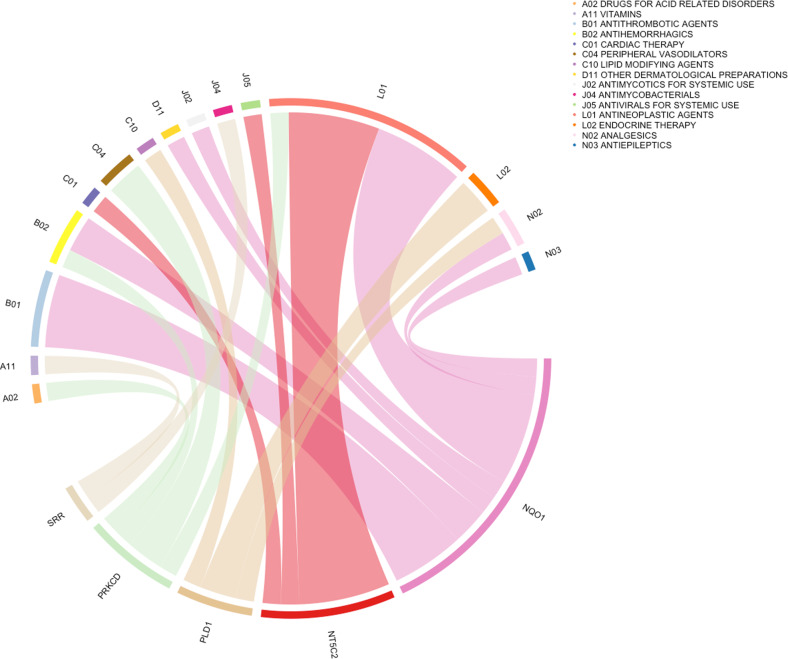

To identify potential repurposing opportunities targeting risk-related proteins, we queried all SUT risk genes (n = 27) detected by PWAS for an interaction with prescription medications via DGIdb. We observed 33 interactions involving 5 genes (SRR, PRKCD, PLD1, NT5C2, and NQO1) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 14). SRR, which showed significant associations with Smk in PWAS and eQTL TWAS, was prioritized as a potential target of serine and pyridoxal phosphate in the antimycobacterials and vitamins drug classes, respectively. DGIdb also prioritized NQO1, a Smk risk gene in the PWAS and sQTL TWAS analysis, as a target for 15 drug interactions, including analgesics (acetaminophen) and antiepileptics (cannabidiol).

Fig. 3. Drug-gene interaction prioritized 5 genes.

Chord diagram of proteome-wide significant genes for SUTs and the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification of drugs. Each gene is linked with drug classes and the width of each line is determined by the number of drugs in each class known to interact with each gene.

Direct PPI was identified for 2 protein pairs (C10orf32 and NT5C2, interaction score = 0.567; MAP1LC3A and WIPI2, interaction score = 0.986) (Supplementary Table 15). However, these PPIs were not significantly enriched (p = 0.33), possibly due to the small number of proteins (N = 21) included in the PPI analysis or the limited proteomic reference information in the STRING database.

Comparison with previous literature

To ascertain novelty, we compared our findings with gene-based analyses in the corresponding GWAS [7–10] and in MAGMA, as implemented by FUMA [30]. Most (16/27) of the PWS genes were identified by gene-level analysis (9/27), as independently GWS (or within a 1-Mb boundary) (1/27), or both (6/27) (Supplementary Table 16). The 11 genes uniquely identified by PWAS included 7 for Smk (SRR, GMPPB, C10orf32, RFT1, BTN3A3, WIPI2, and HEPB1), 2 for AUD (SLC5A6 and TYW5) and 2 for CUD (GMPBB and NAT6). Similarly, 50 of the 83 TWAS eQTL associations for SUTs can be detected in GWAS with 33 novel genes (Supplementary Table 16). For TWAS sQTL, 12 novel SUT associations were identified, with 35 overlapping genes in the original GWAS (Supplementary Table 16).

Compared with previous studies of predicted gene expression by smoking status [35] (TWAS FUSION), PAU [8] (S-PrediXcan), alcohol consumption [11] (S-PrediXcan), CUD [9] (S-PrediXcan) and OUD [10] (S-PrediXcan), our results overlapped with 33 genes (25 for Smk, 5 for AUD, 2 for CUD and 1 for OUD) (Supplementary Table 17). Moreover, we identified novel genes for Smk (n = 42), AUD (n = 5) and OUD (n = 3). None of the TWAS findings were reported in the previous studies of altered gene expression in individuals by current smoking status [31], or AUD [32, 33] or OUD [34] diagnoses.

To detect shared regulatory effects beyond SUTs, we examined the PWS and TWS genes for association with other psychiatric or brain-related traits from published GWAS (using the GWAS catalog), PWAS, and TWAS [12, 23, 24, 35–38]. Most of the top SUT proteins (and genes) also harbor genetic risk loci for psychiatric traits (including schizophrenia, neuroticism, depression, autism, and anxiety) and neurocognitive phenotypes (Supplementary Table 18). Among the 27 PWS genes identified in this study, 4 (ACTR1B, BTN3A3, BTN2A1 and TYW5) overlapped with schizophrenia, 2 (CTNND1 and GMPPB) with depression, and 1 each with PTSD, neuroticism, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and bipolar disorder (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 19). Further, 23 TWS genes were identified in 1 or more psychiatric traits and 8 were associated with 7 neuroimaging traits (Supplementary Table 19). Thus, because SUT risk genes are commonly associated with neuropsychiatric diseases they could play a role in effecting changes in brain structure.

Discussion

We sought to characterize the effects of genetic risk loci on the proteomic architecture of 4 SUTs [7–10] using PWASs that integrated human brain pQTL data [23, 24] with GWAS results. We identified 27 SUT risk genes, of which 8 (CTNND1 for AUD and NT5C2, GMPPB, NQO1, SRR, RHOT2, ACTR1B and BTN2A1 for Smk) showed PWS associations in 2 independent brain proteomes. Notably, of the 8 validated PWS genes, evidence for 6 (CTNND1 for AUD and NT5C2, GMPPB, NQO1, SRR, and ACTR1B for Smk) was consistent with a causal effect based on colocalization analysis, with all genes reflecting independent associations. Moreover, when adjusting for the effect of protein expression on GWAS signal, SNP-trait associations were largely explained by PWAS associations, suggesting that these genes could confer SUT risk by modulating protein abundance in the brain.

Three of the potentially causal genes identified at the protein level–SRR, NT5C2, and NQO1–showed significant associations with Smk at the transcript level. TWAS also identified 12 additional genes with evidence for eQTL validation, of which 2 (C10orf32 and NAT6) showed PWS associations in 1 of the proteomic datasets for Smk and 1 for CUD (NAT6 – an eQTL in the CUD GWAS [9]) (Table 1). The large number of PWS and TWS genes for Smk likely reflects the large sample size (about quadruple that of the other traits) and associated greater statistical power and number of GWS loci in the Smk discovery GWAS [7]. Although the number of TWS genes exceeds that for PWS genes identified for Smk, only about 30% of PWS genes overlap at the transcript level. This has been seen in prior PWASs of psychiatric disorders [23, 37] and supports prior conclusions that mRNA transcript levels can explain one-third to two-thirds of the variance in steady-state protein abundance [40, 41]. Moreover, mRNA and protein abundance levels are weakly correlated [42] and have different genetic architectures [43]. Because gene expression is not a perfect proxy for protein expression [42] studying brain proteins directly can provide novel insights into the impact of genetic variation.

Our Smk PWAS prioritized SRR as an independent risk gene, with causal effects both at the proteomic and transcriptomic level. SRR encodes serine racemase, which converts L- to D-serine, a co-activator of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR), which is a key component in glutamatergic synaptic signaling in the brain [44, 45]. SRR variants were linked with prognosis in a small, candidate-gene study of methamphetamine-induced psychosis [46] and in a large GWAS of schizophrenia [47]. Deletion of SRR in mice reduces the cortical level of D-serine [48] and reducing NMDAR activation [49], which is associated with a reduced ability to extinguish conditioned responses to amphetamine [50] and cocaine-associated stimuli [51]. The association between smoking initiation and reduced SRR protein and transcript expression seen here could, through a shared risk variant, mediate the adaptive processes involved in smoking initiation by altering NMDAR-dependent neurotransmission.

Drug-gene interaction results identified pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), in the vitamins drug class, as a cofactor for SRR, highlighting preclinical evidence that the human SRR is PLP-dependent [52–54]. As the metabolically active form of vitamin B6, PLP binds to SRR and stimulates NMDAR signaling, which is involved in brain metabolism and cellular antioxidant defense [52, 53, 55]. Although a link between cigarette smoking and reduced vitamin B6 and PLP levels has been previously documented [56–58], a mechanistic role for SRR in this association is not established. Functional studies that investigate SRR as a druggable gene target for PLP enzyme activity following smoking exposure could elucidate mechanistic pathways and enhance the development of novel treatments for smoking.

This study should be interpreted in the context of limitations. First, the small sample from which the brain proteome reference dataset was derived contributed to an imbalance between pQTLs and eQTLs/sQTLs, thus limiting our ability to capture the full spectrum of genetic effects on the proteome and transcriptome. This is reflected in the disparity between PWAS and TWAS results, with larger samples in TWAS (CMC eQTL = 48/5419, GTEx eQTL = 50/3106, and CMC sQTL = 48/7771) providing greater statistical power to detect gene expression than in the PWAS (Banner = 15/1139; ROSMAP = 20/1475). Future PWAS of SUTs will require larger brain proteome datasets to permit better pQTL detection. Second, although we identified PWS and TWS genes and highlighted their plausible mechanistic pathways, we could not pinpoint the causal variants associated with these genes. Efforts are needed to map the causal variants and functionally validate the described pathways in the context of SUTs. Thirdly, only EUR were included in the study due to the lack of available data for analyses in other population groups, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Future PWAS of SUTs that include diverse population samples will require availability of greater reference data. Fourth, our power varied greatly by trait, with Smk being by far the best powered trait; the results reflect this disparity.

In conclusion, using PWAS, we identified 6 high-confidence genes that modulate brain protein abundance, potentially altering biological pathways linked to the pathogenesis of SUTs. These genes, as potentially modifiable targets for the development of medications and biomarkers for SUTs, warrant further investigation. Nonetheless, the approach applied here has considerable potential to advance precision medicine efforts in diagnosing and treating SUTs.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: ST, HX, RLK, HRK. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: ST, HX, JG, RLK, HRK. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: ST, HX, RLK, HRK. Final approval of the version to be published: ST, HX, JG, RLK, HRK. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: ST, RLK, HRK.

Funding

This study was supported by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 4 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center and NIH grants DA046345, AA028292, and AA02636.

Competing interests

HRK is a member of advisory boards for Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, Sophrosyne Pharmaceuticals, and Enthion Pharmaceuticals; a consultant to Sobrera Pharmaceuticals; the recipient of research funding and medication supplies for an investigator-initiated study from Alkermes; and a member of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology’s Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative, which was supported in the last 3 years by Alkermes, Dicerna, Ethypharm, Lundbeck, Mitsubishi, and Otsuka. JG and HRK are holders of U.S. patent 10,900,082 titled: “Genotype-guided dosing of opioid agonists,” issued 26 January 2021. The other authors have no disclosures to make.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Rachel L. Kember, Henry R. Kranzler.

Contributor Information

Rachel L. Kember, Email: rkember@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

Henry R. Kranzler, Email: kranzler@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41386-022-01406-1.

References

- 1.Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A, Santomauro D, Erskine H, Mantilla-Herrara A, et al. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:987–1012. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degenhardt L, Grebely J, Stone J, Hickman M, Vickerman P, Marshall BDL, et al. Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action. Lancet. 2019;394:1560–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32229-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reitsma MB, Kendrick PJ, Ababneh E, Abbafati C, Abbasi-Kangevari M, Abdoli A, et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397:2337–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01169-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kendler KS, Jacobson KC, Prescott CA, Neale MC. Specificity of genetic and environmental risk factors for use and abuse/dependence of cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, sedatives, stimulants, and opiates in male twins. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:687–95. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verhulst B, Neale MC, Kendler KS. The heritability of alcohol use disorders: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1061–72. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verweij KJH, Zietsch BP, Lynskey MT, Medland SE, Neale MC, Martin NG, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on cannabis use initiation and problematic use: a meta-analysis of twin studies. Addiction. 2010;105:417–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, Li Y, Brazel DM, Chen F, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet. 2019;51:237–44. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0307-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou H, Sealock JM, Sanchez-Roige S, Clarke TK, Levey DF, Cheng Z, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of problematic alcohol use in 435,563 individuals yields insights into biology and relationships with other traits. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23:809–18. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0643-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson EC, Demontis D, Thorgeirsson TE, Walters RK, Polimanti R, Hatoum AS, et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study meta-analysis of cannabis use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:1032–45. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30339-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kember RL, Vickers-Smith R, Xu H, Toikumo S, Niarchou M, Zhou H, et al. Cross-ancestry meta-analysis of opioid use disorder uncovers novel loci with predominant effects on brain. medRxiv. 2021 Jan 1;2021.12.13.21267480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Marees AT, Gamazon ER, Gerring Z, Vorspan F, Fingal J, van den Brink W, et al. Post-GWAS analysis of six substance use traits improves the identification and functional interpretation of genetic risk loci. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;206:107703. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gusev A, Ko A, Shi H, Bhatia G, Chung W, Penninx BWJH, et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2016;48:245–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbeira AN, Pividori M, Zheng J, Wheeler HE, Nicolae DL, Im HK. Integrating predicted transcriptome from multiple tissues improves association detection. PLOS Genet. 2019;15:e1007889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Z, Zhang F, Hu H, Bakshi A, Robinson MR, Powell JE, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat Genet. 2016;48:481–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giambartolomei C, Vukcevic D, Schadt EE, Franke L, Hingorani AD, Wallace C, et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLOS Genet. 2014;10:e1004383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keele GR, Zhang T, Pham DT, Vincent M, Bell TA, Hock P, et al. Regulation of protein abundance in genetically diverse mouse populations. Cell Genomics. 2021;1:100003. doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2021.100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moya-García A, Adeyelu T, Kruger FA, Dawson NL, Lees JG, Overington JP, et al. Structural and functional view of polypharmacology. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10102. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10012-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng J, Haberland V, Baird D, Walker V, Haycock PC, Hurle MR, et al. Phenome-wide Mendelian randomization mapping the influence of the plasma proteome on complex diseases. Nat Genet. 2020;52:1122–31. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0682-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Serrano G, Shill HA, Walker DG, et al. Arizona study of aging and neurodegenerative disorders and brain and body donation program. Neuropathology. 2015;35:354–89. doi: 10.1111/neup.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Schneider JA. Religious orders study and rush memory and aging project. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:S161–89. doi: 10.3233/JAD-179939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fromer M, Roussos P, Sieberts SK, Johnson JS, Kavanagh DH, Perumal TM, et al. Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1442–53. doi: 10.1038/nn.4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The GTEx consortium. Aguet F, Anand S, Ardlie Kristin G, Gabriel S, Getz Gad A, et al. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science. 2020;369:1318–30. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wingo TS, Liu Y, Gerasimov ES, Gockley J, Logsdon BA, Duong DM, et al. Brain proteome-wide association study implicates novel proteins in depression pathogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:810–7. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021-00832-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wingo AP, Liu Y, Gerasimov ES, Gockley J, Logsdon BA, Duong DM, et al. Integrating human brain proteomes with genome-wide association data implicates new proteins in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2021;53:143–6. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00773-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker RL, Ramaswami G, Hartl C, Mancuso N, Gandal MJ, de la Torre-Ubieta L, et al. Genetic control of expression and splicing in developing human brain informs disease mechanisms. Cell. 2019;179:750–771.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dall’Aglio L, Lewis CM, Pain O. Delineating the genetic component of gene expression in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89:627–36. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mancuso N, Freund MK, Johnson R, Shi H, Kichaev G, Gusev A, et al. Probabilistic fine-mapping of transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2019;51:675–82. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0367-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freshour SL, Kiwala S, Cotto KC, Coffman AC, McMichael JF, Song JJ, et al. Integration of the Drug–Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb 4.0) with open crowdsource efforts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D1144–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vink JM, Jansen R, Brooks A, Willemsen G, van Grootheest G, de Geus E, et al. Differential gene expression patterns between smokers and non-smokers: cause or consequence? Addict Biol. 2017;22:550–60. doi: 10.1111/adb.12322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapoor M, Wang JC, Farris SP, Liu Y, McClintick J, Gupta I, et al. Analysis of whole genome-transcriptomic organization in brain to identify genes associated with alcoholism. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:89. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0384-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huggett SB, Ikeda AS, Yuan Q, Benca-Bachman CE, Palmer RHC. Genome- and transcriptome-wide splicing associations with problematic alcohol use and alcohol use disorder. bioRxiv. 2021 Jan 1;2021.03.31.437932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Seney ML, Kim SM, Glausier JR, Hildebrand MA, Xue X, Zong W, et al. Transcriptional alterations in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens implicate neuroinflammation and synaptic remodeling in opioid use disorder. Stress Inflamm Synaptic Remodel Addict. 2021;90:550–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loh PR, Kichaev G, Gazal S, Schoech AP, Price AL. Mixed-model association for biobank-scale datasets. Nat Genet. 2018;50:906–8. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wingo TS, Gerasimov ES, Liu Y, Duong DM, Vattathil SM, Lori A, et al. Integrating human brain proteomes with genome-wide association data implicates novel proteins in post-traumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2022 Apr 21; Available from: 10.1038/s41380-022-01544-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Liu J, Li X, Luo XJ. Proteome-wide association study provides insights into the genetic component of protein abundance in psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;90:781–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pathak GA, Singh K, Wendt FR, Fleming TW, Overstreet C, Koller D, et al. Genetically regulated multi-omics study for symptom clusters of posttraumatic stress disorder highlights pleiotropy with hematologic and cardio-metabolic traits. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:1394–404. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01488-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao B, Shan Y, Yang Y, Yu Z, Li T, Wang X, et al. Transcriptome-wide association analysis of brain structures yields insights into pleiotropy with complex neuropsychiatric traits. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2878. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23130-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell. 2016;165:535–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogel C, Marcotte EM. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:227–32. doi: 10.1038/nrg3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robins C, Liu Y, Fan W, Duong DM, Meigs J, Harerimana NV, et al. Genetic control of the human brain proteome. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:400–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang C, Farias F, Ibanez L, Sadler B, Fernandez MV, Wang F, et al. Genomic and multi-tissue proteomic integration for understanding the biology of disease and other complex traits. 2020; Available from: http://europepmc.org/abstract/PPR/PPR180358

- 44.Henneberger C, Papouin T, Oliet SHR, Rusakov DA. Long-term potentiation depends on release of d-serine from astrocytes. Nature. 2010;463:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papouin T, Ladépêche L, Ruel J, Sacchi S, Labasque M, Hanini M, et al. Synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors are gated by different endogenous coagonists. Cell. 2012;150:633–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yokobayashi E, Ujike H, Kotaka T, Okahisa Y, Takaki M, Kodama M, et al. Association study of serine racemase gene with methamphetamine psychosis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:169–75. doi: 10.2174/157015911795017092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A, Walters JTR, Farh KH, Holmans PA, et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balu DT, Li Y, Puhl MD, Benneyworth MA, Basu AC, Takagi S, et al. Multiple risk pathways for schizophrenia converge in serine racemase knockout mice, a mouse model of NMDA receptor hypofunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:E2400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304308110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puhl MD, Berg AR, Bechtholt AJ, Coyle JT. Availability of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor coagonists affects cocaine-induced conditioned place preference and locomotor sensitization: implications for comorbid schizophrenia and substance abuse. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2015;353:465. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.223099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benneyworth MA, Coyle JT. Altered acquisition and extinction of amphetamine-paired context conditioning in genetic mouse models of altered NMDA receptor function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2496–504. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Puhl MD, Desai RI, Takagi S, Presti KT, Doyle MR, Donahue RJ, et al. N-Methyl-d-aspartate receptor co-agonist availability affects behavioral and neurochemical responses to cocaine: insights into comorbid schizophrenia and substance abuse. Addict Biol. 2019;24:40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.de Miranda J, Panizzutti R, Foltyn VN, Wolosker H. Cofactors of serine racemase that physiologically stimulate the synthesis of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor coagonist d-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:14542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222421299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramos RJ, Pras-Raves ML, Gerrits J, van der Ham M, Willemsen M, Prinsen H, et al. Vitamin B6 is essential for serine de novo biosynthesis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;40:883–91. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Graham DL, Beio ML, Nelson DL, Berkowitz DB. Human serine racemase: key residues/active site motifs and their relation to enzyme function. Front Mol Biosci [Internet]. 2019;6. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmolb.2019.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Raboni S, Marchetti M, Faggiano S, Campanini B, Bruno S, Marchesani F, et al. The energy landscape of human serine racemase. Front Mol Biosci [Internet]. 2019;5. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmolb.2018.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Gabriel HE, Crott JW, Ghandour H, Dallal GE, Choi SW, Keyes MK, et al. Chronic cigarette smoking is associated with diminished folate status, altered folate form distribution, and increased genetic damage in the buccal mucosa of healthy adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:835–41. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skeie E, Strand E, Pedersen ER, Bjørndal B, Bohov P, Berge RK, et al. Circulating B-vitamins and smoking habits are associated with serum polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with suspected coronary heart disease: a cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0129049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ulvik A, Ebbing M, Hustad S, Midttun Ø, Nygård O, Vollset SE, et al. Long- and short-term effects of tobacco smoking on circulating concentrations of B vitamins. Clin Chem. 2010;56:755–63. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.137513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.