Abstract

The emergence of drug-resistant bacterial pathogens has placed renewed emphasis on the total chemical synthesis of novel antibacterials. Tetracyclines, macrolides, streptogramins, and lincosamides are now accessible by flexible and general synthetic routes. Pleuromutilins, antibiotics based on the fungal metabolite pleuromutilin, have remained resistant to this approach, in large part because of the difficulties encountered in the de novo construction of the decahydro-3a,9-propanocyclopenta[8]annulene skeleton. Here we present a platform for the total synthesis of pleuromutilins that provides access to diverse derivatives bearing alterations at skeletal and peripheral positions that were previously inaccessible. The synthesis is enabled by the serendipitous discovery of a vinylogous Wolf rearrangement, which serves to establish the C9 quaternary center in the targets, and the development of a highly diastereoselective butynylation of an α-quaternary aldehyde, which forms the C14 secondary alcohol. The versatility of the route is demonstrated through the synthesis of seventeen structurally-distinct derivatives, many possessing potent antibacterial activity.

Editorial Summary:

General synthetic methods to access pleuromutilin antibiotics are limited because of their complex carbocyclic skeleton. Now, a synthetic platform has been developed to access structurally diverse pleuromutilins with variations at the quaternary C12 position and hydrindanone cores. Seventeen structurally-distinct derivatives were prepared and evaluated against a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

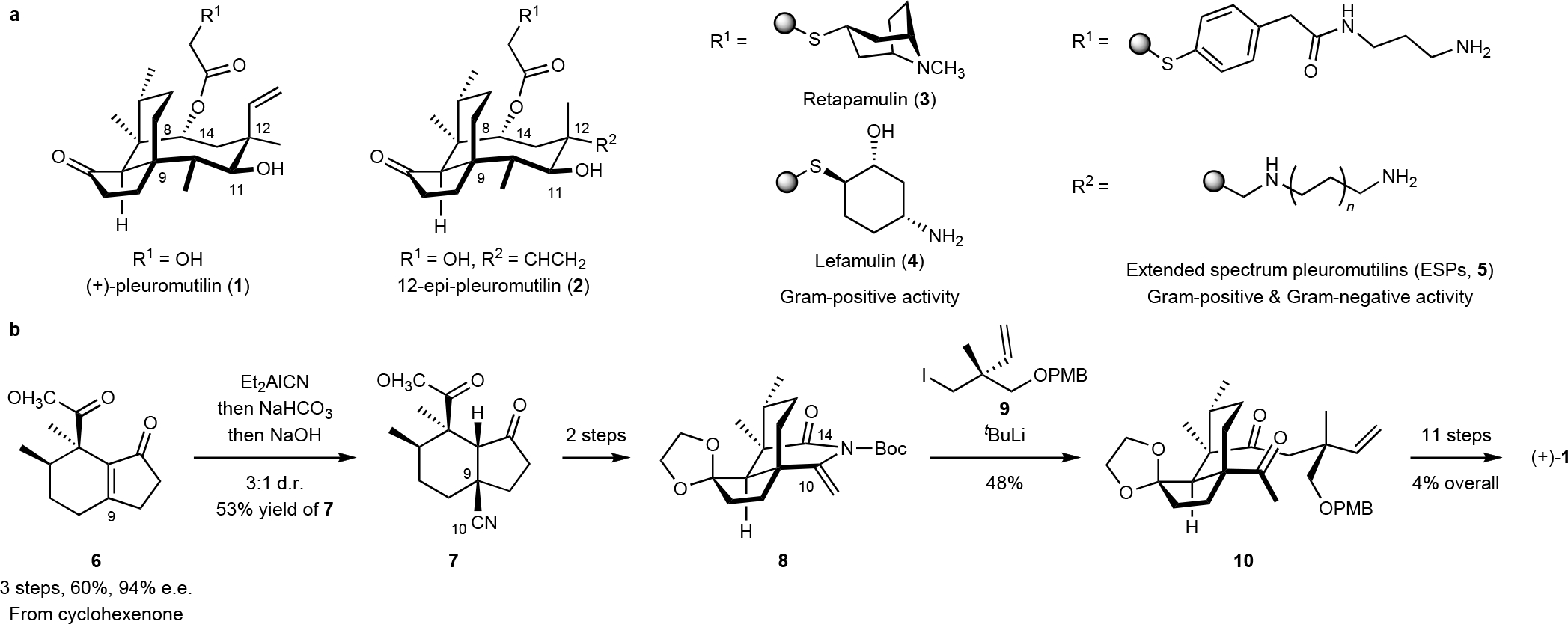

Pleuromutilins1–2 inhibit protein synthesis by binding the peptidyl transferase center (PTC) of the bacterial ribosome. The carbocyclic skeleton and C14 extensions occupy the A- and P-sites of the PTC, respectively.3 Variations of the glycolic ester increase potency in Gram-positive pathogens (GPPs).1–2 Alternatively, “extended spectrum pleuromutilins” (ESPs, see 5, Fig. 1a) are formed by the introduction of polar substituents at the C12 pseudoequatorial position4 (by an unusual epimerization of C12).5 ESPs possess activity against Gram-negative pathogens (GNPs), including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae6 and drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae,7 strains identified as Urgent Threats by the US CDC. Pleuromutilins bind the PTC by a unique conformation3 and do not display cross-resistance with other antibiotics.2 Moreover, they are durable:8 three stepwise mutations in the ribosomal protein L3 are required for resistance, but each mutation induces a fitness defect.9 The class is limited by low oral bioavailability and cytochrome P450 oxidation at C8,10–12 which leads to deactivation.

Fig. 1. The structures of (+) pleuromutilin (1), clinically relevant derivatives, and prior synthetic art.

a. Structures of (+)-pleuromutilin (1), 12-epi-pleuromutilin (2), retapamulin (3), lefamulin (4), and extended spectrum pleuromutilins (ESPs, 5). b. Overview of the prior synthetic route to (+)-pleuromutilin (1) by Murphy et al.18

Retapamulin (3)13 and lefamulin (4)14 are clinical semisynthetic agents. While other classes of antibiotics, such as the tetracyclines15, macrolides16, streptogramins17, and lincosamides,18 are now accessible by flexible, high-yielding, and fully synthetic routes, pleuromutilins are less-well developed.19–24 Advanced derivatives were prepared by Sorensen and co-workers25 but their activity was modest. We reported a synthesis of (+)-pleuromutilin (1) and its 12-epi-derivative (2).22 A Nagata hydrocyanation26 of the hydrindenone 6 established the C9 stereocenter, and a two-fold neopentylic fragment coupling joined the eneimide 8 and an organolithium reagent derived from the alkyl iodide 9 (Fig. 1b). Unfortunately, the hydrocyanation of 6 was not general, the scope of the fragment coupling was narrow, and the introduction of the C14 stereocenter after formation of the eight-membered ring was challenging.22–23 Elaboration of the fragment coupling product 10 to (+)-pleuromutilin (1) proceeded in 11 steps and 4% yield (0.4% from cyclohexanone). These limitations motivated us to devise the new synthetic route presented herein. We sought to: a) develop alternative methods to establish the C9 and C14 stereocenters; b) increase the generality of the route; c) increase overall yield; and d) move branch points later in the synthesis. Because modifications to the C12 axial position in (+)-pleuromutilin (1) have a negligible effect on activity,4, 27 and 12-normethyl derivatives adopt the same conformation as (+)-pleuromutilin (1; Fig. 2f) we targeted 12-noralkyl pleuromutilins, an approach that simplifies synthetic planning.

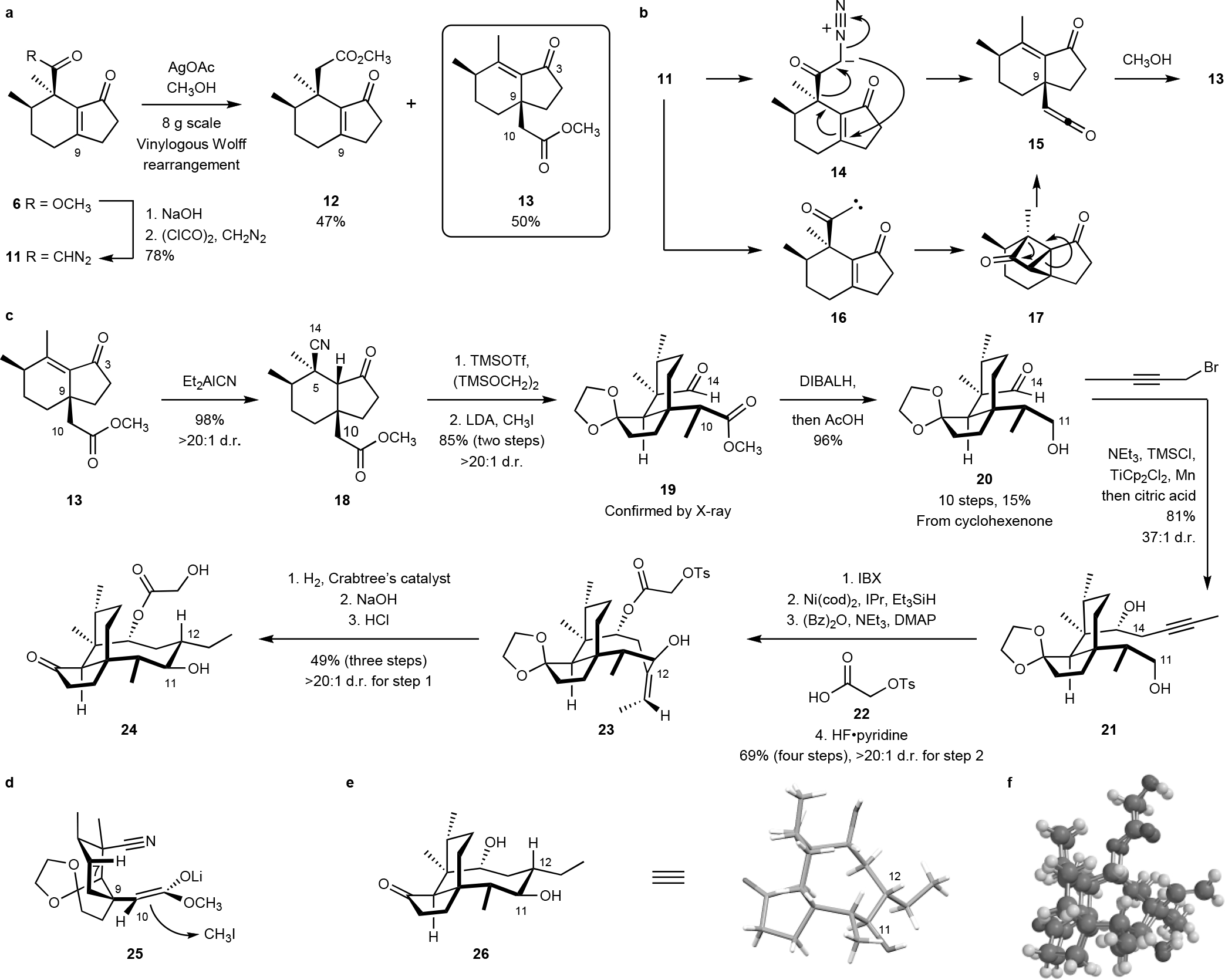

Fig. 2. An unexpected vinylogous Wolff rearrangement provided access to the C9 quaternary stereocenter and formed the basis for a synthetic route to C12 normethyl pleuromutilins.

a. Arndt–Eistert homologation of the α-diazoketone 11 provided the homologation product 12 and the rearrangement product 13. b. Potential mechanistic pathways for the rearrangement may involve a concerted 2,3-rearrangement of the α-diazoketone 14 or rearrangement of the ketocarbene 16. c. Synthesis of the C12 normethyl pleuromutilin derivative 24. d. Proposed orientation of the (Z)-enolate 25. e. X-ray structure of the mutilin derivative 26. f. MMFF (Merck molecular force field) overlay of 1 and 24.

Results and Discussion.

Synthesis of a diversifiable advanced intermediate.

The first goal (a) was addressed by the discovery of a vinylogous Wolff rearrangement of the α-diazoketone 11 (Fig. 2a). Thus, the expected homologation product 12 and the rearranged ester 13 were obtained in 47% and 50% yield, respectively, when the α-diazoketone 11 was subjected to Arndt–Eistert homologation conditions (silver acetate, methanol). The structure of 13 was confirmed by X-ray analysis of the corresponding carboxylic acid (Fig. S8) and the products 12 and 13 are readily separable by flash-column chromatography (Rf of 13 and 12 = 0.83 and 0.67, respectively, in 50% ethyl acetate–hexanes). The transformation may proceed by a concerted [2,3]-rearrangement with loss of dinitrogen (11→14→15), or an intramolecular cyclopropanation–fragmentation pathway (11→16→17→15, Fig. 2b). This is the first vinylogous Wolff rearrangement28 reported for an electron-deficient π-system. Though we were not able to increase the ratio of 13:12, this rearrangement provided a stereospecific method to establish the C9–C10 bond in the target and provided reliable results on a multigram scale. Of greater significance, this rearrangement proved tolerant to several different ring sizes and substituents and was applied to other bicyclic ketones, leading to novel pleuromutilin structures (Figs. 3, 4).

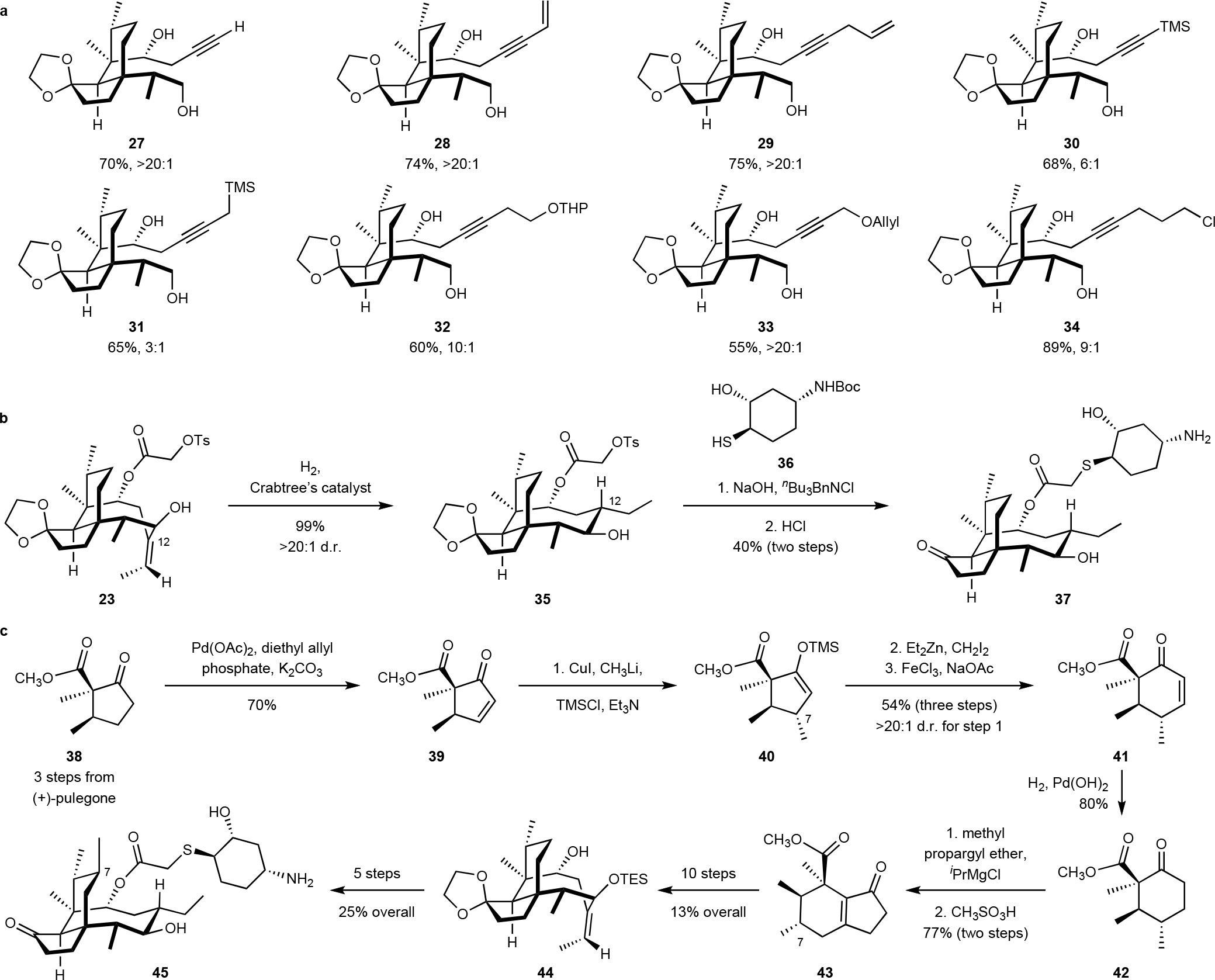

Fig. 3. Scope of the butynylation reaction, competition of a fully derivatized analog and synthesis of a C7-substitued pleuromutilin.

a. Products synthesized by addition to 20. Isolated yields and diastereoselectivity are reported. b. Synthesis of the C12 normethyl lefamulin derivative 37. c. Synthesis of the C7-substituted derivative 45.

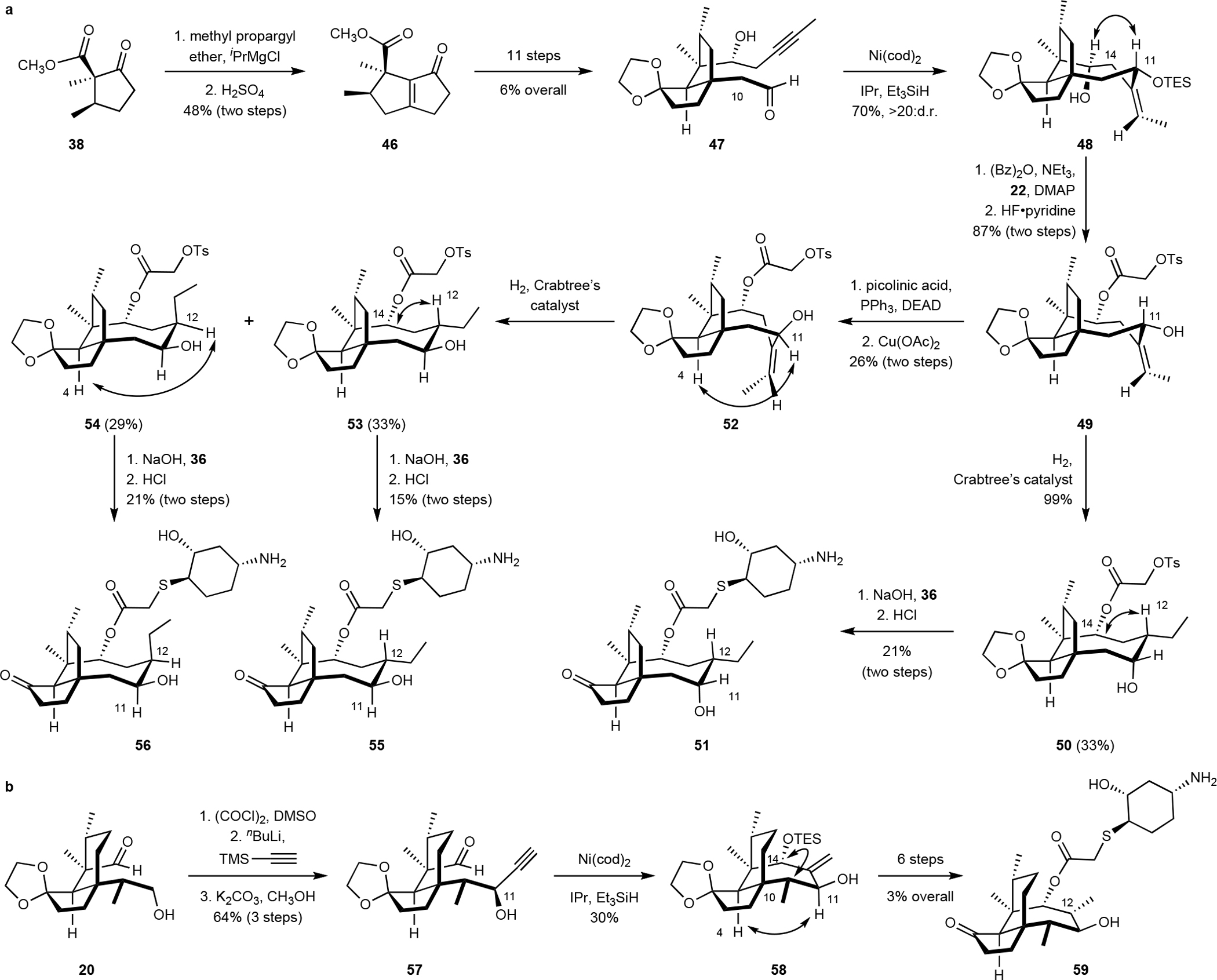

Fig. 4. Preparation of pleuromutilin derivatives, including ring contractions in the six- and eight-membered rings.

a. Synthesis of the ring-contracted derivatives 51, 55 and 56; NOE enhancements supporting the relative stereochemistry of 48, 50, 52, 53, and 54 are indicated by arrows. b. Synthesis of the derivative 59, which contains a seven-membered ring. NOE enhancements supporting the relative stereochemistry of 58 are indicated by arrows.

Treatment of the rearrangement product 13 with diethylaluminum cyanide provided the 1,4-hydrocyanation product 18 in 98% yield and as a single detectable C5 diastereomer (1H NMR analysis, Fig. 2c), a result consistent with earlier findings by Sorensen and co-workers.25 Protection of the ketone22 provided the expected glycol ketal (not shown). The methylation product 19 was obtained as a single detectable diastereomer (1H NMR analysis) by deprotonation of the ester (lithium diisopropylamide, LDA), followed by the addition of iodomethane (85% from 18). The relative stereochemistry of 19 was secured by X-ray analysis. We reason that the (Z)-enolate29 25 may adopt the conformation shown in Fig. 2d, which minimizes 1,3-diaxial interactions with the axial C7 and C9 substituents. Approach of iodomethane from the less hindered β-face would provide the observed product. Reduction of the nitrile and ester residues (diisobutylaluminum hydride, DIBALH) generated the hydroxyaldehyde 20 (96%), which constitutes our first point of divergence (10 steps, 15% overall from cyclohexenone).

We then focused on establishing the C14 stereocenter before formation of the eight-membered ring. We initially evaluated the butynylation of 20, as this would provide the correct functional group handles for later steps (Table S1). The product 21 was obtained in 30–33% yield and as predominantly the undesired (14S) diastereomer when butynylmagnesium bromide was used as the nucleophile in ethereal solvents. After evaluating a large number of conditions, we found that the desired diastereomer (14R)-21 was formed with >20:1 stereoselectivity by titanocene-mediated addition of 1-bromo-but-2-yne,30 although the yield was only 21%. Further optimization provided the desired (14R) diastereomer in 81% and with 37:1 diastereoselectivity. The alternating, reagent-controlled stereoselectivities in this addition are notable. The addition of propargyl magnesium reagents may proceed by chelation between the Grignard species and the hydroxyaldehyde 20;31 addition to the less-hindered α-face would provide the (14S) diastereomer. The stereoselectivity in the titanocene-mediated pathway is thought to arise from a closed six-membered transition state between an allenyl-titanium reagent and the aldehyde within 20.32 Notably, the titanocene-mediated pathway was singularly successful; all other approaches examined returned starting material, likely due to the hindered nature of the α,α,α-trisubstituted aldehyde. The addition proved to be relatively general for a series of related nucleophiles (Fig. 3a). The yields and stereoselectivities were largely insensitive to alkyne substitution, and the reaction was tolerant of heteroatom- and halogen-substituted reagents. The scope of this reaction provided additional functional group handles for diversification of the C12 position following formation of the eight-membered ring (Figs. S5–S7).

Selective oxidation of the primary alcohol within 21 (2-iodoxybenzoic acid, IBX33) and exo-selective nickel-catalyzed reductive cyclization34–35 formed a cyclization product (not shown) as a single detectable C11 diastereomer (1H NMR analysis, Fig. 2c). Introduction of the glycolic acid residue and removal of the silyl ether (hydrogen fluoride–pyridine complex) generated the ester 23 (69% over four steps). Directed hydrogenation (Crabtree’s catalyst36), sulfonate displacement, and ketal cleavage provided the pleuromutilin derivative 24 (49% overall). The complete relative stereochemistry of 24 was determined by X-ray analysis of the saponification product 26 (Fig. 2e). A molecular dynamics simulation (Merck molecular force field, MMFF)37 confirmed that 24 and (+)-pleuromutilin (1) overlay without discernable differences in conformation and positioning of the substituents required for hydrogen bonding contacts with the ribosome (Fig. 2f).3 Because earlier structure–activity data revealed that the pseudoaxial C12 substituent does not influence antibacterial activity,4 and the calculations suggest it does not bias the conformation of the molecule, we pursued 12-norvinyl derivatives as a means to simplify the synthetic route. By this approach, 23 was obtained in 10 steps and 17% yield from the hydrindenone 6, a substantial improvement in efficiency over our route to 12-epi-pleuromutilin (2; 1.5% overall). The sulfonated glycolic ester facilitates diversification via nucleophilic displacement while the exocyclic alkene provides a handle for late-stage equatorial functionalization. To demonstrate the power of this approach, a derivative of the clinical agent lefamulin (4)14, 38 was prepared in three steps from 23 by directed hydrogenation, sulfonate displacement with the thiol 36, and acidic deprotection (40% overall, Fig. 3b).

Synthesis of core-modified pleuromutilins.

With a new and efficient synthetic pathway established, we focused on adapting this chemistry to the synthesis of pleuromutilins containing skeletal modifications that are inaccessible by semisynthesis. Because metabolic oxidation at C8 (Fig. 1) leads to antibiotic deactivation39–40 we targeted derivatives that might be less susceptible to this pathway by blocking this position with an alkyl substituent (as in 45, Fig 3c) or contracting the six-membered ring to render this site less accessible (as in 51, 55, and 56, Fig. 4a). Both of these classes can be prepared from the common intermediate 38, which is itself derived from (+)-pulegone in three steps and 58% yield.41

Palladium(II)-mediated oxidation of 3842 (palladium acetate, diethylallylphosphate, potassium carbonate)43–44 provided the enone 39 (70%, Fig. 3c). Silicon-promoted, copper-catalyzed 1,4-addition45 of methyllithium generated the 1,4-addition product 40 as a single diastereomer. The relative stereochemistry of the product was confirmed by X-ray analysis of a later intermediate. Cyclopropanation, followed by an iron(III) trichloride-mediated ring expansion,46 elimination of hydrogen chloride, and hydrogenation with Pearlman’s catalyst provided the cyclohexane 42 (43%, four steps). 1,2-Addition of the Grignard reagent derived from methyl propargyl ether followed by treatment with methanesulfonic acid formed the bicyclic enone 43 (77% overall), which was elaborated to the tricycle 44 in 10 steps (13% overall, see Fig. S1). The tricycle 44 was transformed to the C7-substituted lefamulin derivative 45 in five steps (25% overall, Fig. S1).

The synthesis of the ring-contracted derivatives began with 1,2-addition of the Grignard reagent derived from methyl propargyl ether to 38, followed by acid-catalyzed rearrangement, to provide the bicyclo[3.3.0]octane derivative 46 (48%, two steps, Fig. 4a). The bicyclic ketone 46 was elaborated to the cyclization precursor 47 in 11 steps and 6% overall yield (Fig. S3). Reductive cyclization of 47 provided the tricyclic product 48 (70%) as a single detectable diastereomer (1H NMR analysis). NOE analysis established that the (11R) diastereomer was formed. All attempts to cyclize the derivative of 47 containing a C10 methyl substituent were uniformly unsuccessful (Fig. S2). The tricyclic product 48 (70%) was elaborated to the glycolic ester derivative 49 in two steps (87% overall).

The ester 49 served as a branch point to prepare three distinct, ring-contracted analogs. Thus, directed hydrogenation, introduction of the lefamulin side chain, and acidic deprotection provided the (11R) derivative 51 (21% overall). The C11 center could be inverted under Mitsunobu conditions using picolinic acid as nucleophile.47 Copper-catalyzed methanolysis then provided the (11S) derivative 52 (26% overall). Hydrogenation of 52 formed a ~1:1 mixture of (separable) C12 diastereomers. These were elaborated separately to the lefamulin derivatives 55 and 56.

Finally, we prepared the derivative 59, wherein the eight-membered ring is contracted by a single atom (Fig. 4b). We targeted this derivative to probe the significance of the location of the C11 hydroxyl in ribosome binding. Swern oxidation of 20, followed by the site- and diastereoselective addition of lithium trimethylsilyl acetylide and cleavage of the silyl substituent (potassium carbonate, methanol) provided the propargylic alcohol 57 (64% overall). Reductive cyclization of 57 generated the allylic alcohol 58 (30%) as a single detectable C14 diastereomer (1H NMR analysis, relative stereochemistry confirmed by NOE analysis). The cyclization product 58 was converted to the ring-contracted derivative 59 in six steps (3% overall, unoptimized, Fig. S4).

Synthesis of additional derivatives and evaluation of antibiotic activity.

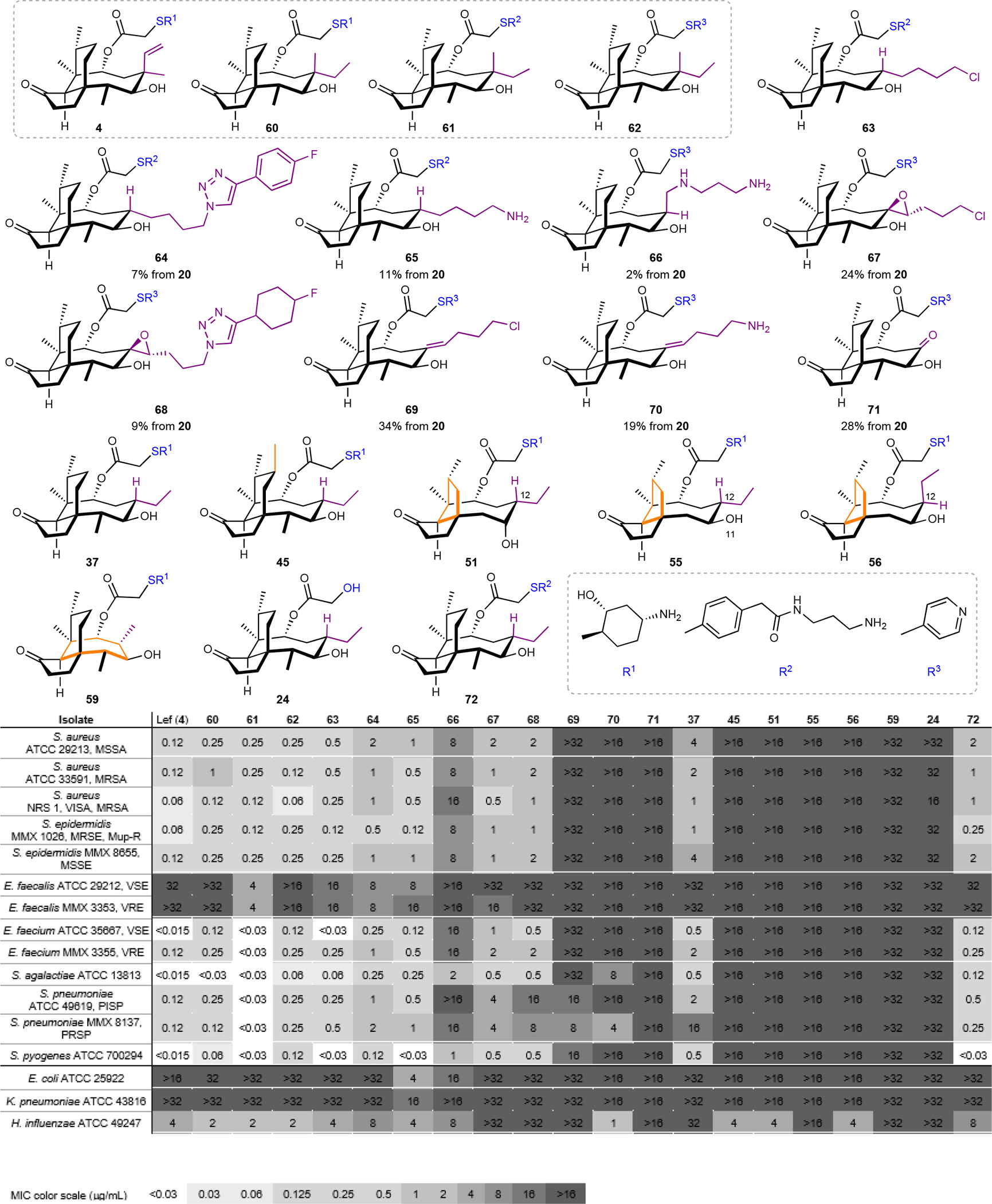

In parallel to synthesizing the various tricyclic cores, we introduced late-stage modifications that are inaccessible by semisynthesis. For this objective, nine additional derivatives were prepared with modifications at the C12 equatorial position (Fig. 5 and Figs. S5–S7). We assessed the Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of these C12 derivatives and the agents bearing modified skeletons against a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. Several derivatives had comparable potency to the clinically used lefamulin (4) and semisynthetic controls (60–62). The alkyl chloride 63 (prepared from the addition product 34, Fig. S5) emerged as the most potent compound, with notable activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (0.25 μg/mL), methicillin and mupirocin-resistant S. epidermidis (0.12 μg/mL), and vancomycin-resistant E. faceium (0.25 μg/mL). It also exhibited potent activity towards S. pyogenes (0.03 μg/mL) and vancomycin-susceptible E. faceium (0.03 μg/mL). Analogs 64 and 65, also derived from the alkyl chloride 34 via azide displacement and click chemistry, demonstrated comparable potency. Like lefamulin (4) and 63, they are active against several vancomycin- and penicillin-resistant bacterial strains. The amine 65 also showed modest activity in E. coli 25922 (4 μg/mL) and the ESKAPE pathogen K pneumoniae (16 μg/mL), consistent with the notion that sterically-accessible, basic amines enhance activity in Gram-negative pathogens.4, 48 Relative to the alkyl chloride 63, 64 and 65 possessed modest activity (8 μg/mL) against the ABC-F transporter-expressing E. faecalis, suggesting a path forward to combat efflux. An axial, C12 diamine extension in the derivative 66 was also prepared from the enyne propargylation product 28. The axial amine showed diminished antibiotic activity, emphasizing the strength of our sequence towards selectively preparing equatorial derivatives (Fig S6). In the first examples of heteroatom substituents at the C12 position of pleuromutilins, the two exocyclic epoxide derivatives 67 and 68 possessed moderate antibiotic activity across most of the Gram-positive isolates (0.5–2 μg/mL), suggesting the allylic alcohol in our sequence is a valuable starting point for further diversification. The exocyclic alkenes 69 and 70 were nearly inactive, suggesting the conformation of the eight-membered ring is vital for cellular uptake or ribosome binding. The α-hydroxy ketone 71 derivative was also inactive, supporting hydrogen-bond donation by the C11 hydroxyl group as critical for ribosome binding.

Fig. 5. Seventeen structurally-distinct derivatives were prepared and evaluated against a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Fully synthetic pleuromutilins prepared using the synthetic platform that feature different core modifications (24, 37, 45, 63–72), ring sizes (51, 55, 56, 59) and C14 glycolic ester derivatives (R1–R3). The compounds were compared to semisynthetic controls (lefamulin (4), 60–62; shown in the gray box) against a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (μg/mL) are reported. MSSA: methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus; MRSE: methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis; MSSE: methicillin-susceptible S. epidermidis; VSE: vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus; VRE: vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; PISP: penicillin-intermediate S. pneumoniae; PRSP: penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae.

A significant decrease in potency was observed when the C12 normethyl analog 37 was directly compared to lefamulin (4) and the semisynthetic control 60 (Fig. 5). This was surprising to us given the prior reports that modification of the C12 axial position has little effect on antibacterial activity,4 and suggests the quaternary center could contribute to stability or hydrophobic contacts with the ribosome. The core-modified analogs 45, 51, 55, 56 and 59 were inactive in all isolates tested except H. influenzae, where 45, 51 and 56 had identical activity to lefamulin (4). The C7-substituted and ring contracted derivatives provide the first structure–activity data related to ring size and carbogenic substitution.

The inactivity of the glycolic acid side chain analog 24 highlighted the need to derivatize with a polar side chain in order to glean meaningful structure–activity insights. This is a strength of the synthetic route. For example, exchanging the side chain of the C12 normethyl compound to the benzamide diamine side-chain in 724 (R2, Fig. 5) improved potency across many of the Gram-positive strains tested. The derivative 72 had comparable activity to the corresponding semisynthetic control 61, suggesting that further side chain modification could easily be performed to optimize the potency of the active C12 normethyl derivatives.

Conclusion.

We have developed a new platform to prepare fully synthetic pleuromutilin analogs with potent activity. The synthetic strategy, which proceeds through a novel, stereospecific Wolff rearrangement and highly diastereoselective addition of propargylic nucleophiles to an α-quaternary aldehyde, addresses the challenges identified in our previous synthesis and provides access to the late-stage, diversifiable intermediate 23 in 10 steps and 17% overall yield from the hydrindenone 6, a significant improvement compared to 14 steps and 1.5% overall yield to the diversification point in the prior sequence, (+)-12-epi-pleuromutilin (2), from 6. Perhaps more significantly, the route proved general and delivered seventeen structurally-diverse analogs including those possessing varying ring sizes and substituents at the C14, C12, and C7 positions. Several of the novel compounds prepared are potent against a variety of antibiotic-resistant pathogens and provide novel structure–activity insights into this class of molecules. The generality of the route, in conjunction with the ability to introduce novel pseudo-equatorial substituents, may lead to optimal compounds with potent Gram-positive and Gram-negative activity. Further development of core modifications could allow for optimization of oral bioavailability and metabolic stability, two long-standing challenges for this class.10–12

Methods:

Caution.

For the preparation of diazomethane, there is explosion and shock hazard. Needles should be avoided and unscratched glassware should be used. Perform reagent preparation, aqueous workup, and all reactions in a well-ventilated fume hood behind a blast shield. All glassware and waste solutions should be quenched extremely carefully with dilute acid before removing from fume hood.

For the synthesis of cyanoester 18, hydrocyanation product S18, and nitrile S32 there is a cyanide hazard. Perform reaction, aqueous workup, and purification in a well-ventilated fume hood. All glassware and waste solutions should be washed with bleach prior to removing from fume hood.

MIC testing.

Compounds were evaluated by Micromyx LLC (Fig. 5) against a variety of pathogenic bacteria, using the broth microdilution method, as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Pre-weighed vials of the test agents were stored at −20 °C until testing. On the day of the assay, the compounds were dissolved in 100% DMSO (Sigma 472301) to a stock concentration of 1280 μg ml−1 or 640 μg ml−1. The concentration range tested for each of the compounds was 32–0.03 μg ml−1 or 16–0.015 μg ml−1, and each compound was tested in triplicate. Lefamulin and levofloxacin were used as the quality control agents. For more details on test organisms, medium and methods, see pgs. S8–S10 of the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement.

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health NIGMS (R35-GM131913), the Chemistry Biology Interface Training Program (T32GM067543 to M. D.) and Yale University (Wiberg Fellowship to O.G.) is gratefully acknowledged. We acknowledge Thomas Smeltzer (Treehouse Biotech) and Abigail Heuer (Yale University) for preliminary experiments. We thank Matthew Espinosa (Yale University) for helpful suggestions and glovebox assistance. Dr. Fabian Menges is acknowledged for obtaining the high-resolution mass spectrometry data. Dr. Brandon Mercado is acknowledged for obtaining the X-ray crystallography data. Dr. Eric Paulson is acknowledged for assistance with NMR processing.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement:

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2114513 (S3), 2114514 (19), 2114515 (26), 2114516 (S20), and 2114517 (S37). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

Main references.

- 1.Fazakerley NJ & Procter DJ Synthesis and synthetic chemistry of pleuromutilin. Tetrahedron 70, 6911–6930 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goethe O, Heuer A, Ma X, Wang Z & Herzon SB Antibacterial properties and clinical potential of pleuromutilins. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36, 220–247 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidovich C et al. Induced-fit tightens pleuromutilins binding to ribosomes and remote interactions enable their selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 4291–4296 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thirring K et al. Nabriva Therapeutics. Preparation of 12-epi-Pleuromutilin Derivatives as Antimicrobial Agents. WO2015110481A1 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berner HV,H, Schulz G & Schneider H Inversion of configuration of the vinylgroup at carbon 12 by reversible retro-en-cleavage. Monatsh. fuer Chem. 117, 1073 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wicha W et al. Efficacy of novel extended spectrum pleuromutilins against E. coli in vitro and in vivo. In 25th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Copenhagen, Denmark: (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paukner S et al. In vitro activity of the novel pleuromutilin BC-3781 tested against bacterial pathogens causing sexually transmitted diseases (STD). In 53rd Interscience Conference on Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. Denver, CO, (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paukner S & Riedl R Pleuromutilins: Potent Drugs for Resistant Bugs—Mode of Action and Resistance. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 7, a027110 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gentry DR, Rittenhouse SF, McCloskey L & Holmes DJ Stepwise exposure of Staphylococcus aureus to pleuromutilins is associated with stepwise acquisition of mutations in rplC and minimally affects susceptibility to retapamulin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 2048–2052 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Springer DM et al. Synthesis and activity of a C-8 keto pleuromutilin derivative. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13, 1751–1753 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu L et al. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of C-2(S)-substituted pleuromutilin derivatives. Chin. Chem. Lett. 21, 507–510 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun F et al. Unraveling the Metabolic Routes of Retapamulin: Insights into Drug Development of Pleuromutilins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62, e02388–17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daum RS, Kar S, Kirkpatrick P Retapamulin. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 865–866 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veve MP & Wagner JL Lefamulin: Review of a Promising Novel Pleuromutilin Antibiotic. Pharmacotherapy 38, 935–946 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu F & Myers AG Development of a platform for the discovery and practical synthesis of new tetracycline antibiotics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 32, 48–57 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seiple IB et al. A platform for the discovery of new macrolide antibiotics. Nature 533, 338–345 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q et al. Synthetic group A streptogramin antibiotics that overcome Vat resistance. Nature 586, 145–150 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitcheltree MJ, Stevenson JW, Pisipati A & Myers AG A Practical, Component-Based Synthetic Route to Methylthiolincosamine Permitting Facile Northern-Half Diversification of Lincosamide Antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6829–6835 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbons EG Total synthesis of (±)-pleuromutilin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104, 1767–1769 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boeckman RK, Springer DM & Alessi TR Synthetic studies directed toward naturally occurring cyclooctanoids. 2. A stereocontrolled assembly of (±)-pleuromutilin via a remarkable sterically demanding oxy-cope rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 8284–8286 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fazakerley NJ, Helm MD & Procter DJ Total synthesis of (+)-pleuromutilin. Chem. – Eur. J. 19, 6718–6723 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy SK, Zeng M & Herzon SB A modular and enantioselective synthesis of the pleuromutilin antibiotics. Science, 356, 956 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng M; Murphy SK; Herzon SB Development of a Modular Synthetic Route to (+)-Pleuromutilin, (+)-12-epi-Mutilins, and Related Structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16377–16388 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farney EP; Feng SS; Schafers F; Reisman SE Total Synthesis of (+)-Pleuromutilin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1267–1270 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lotesta SD et al. Expanding the pleuromutilin class of antibiotics by de novo chemical synthesis. Chem. Sci. 2, 1258–1261 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagata W, Yoshioka M & Murakami M Hydrocyanation. VI. Application of the new hydrocyanation methods to conjugate hydrocyanation of α,β-unsaturated ketones, conjugated dienones, and conjugated enamines and to preparation of α-cyanohydrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94, 4654–4672 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egger H & Reinshagen H New pleuromutilin derivatives with enhanced antimicrobial activity. II. Structure-activity correlations. J. Antibiot (Tokyo) 29, 923–927 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarpong R, Su JT & Stoltz BM The Development of a Facile Tandem Wolff/Cope Rearrangement for the Synthesis of Fused Carbocyclic Skeletons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 13624–13625 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ireland RE & Willard AK The stereoselective generation of ester enolates. Tetrahedron Lett. 16, 3975–3978 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Justicia J, Sancho-Sanz I, Álvarez-Manzaneda E, Oltra JE & Cuerva JM Efficient Propargylation of Aldehydes and Ketones Catalyzed by Titanocene(III). Adv. Synth. Catal. 351, 2295–2300 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartolo ND, Read JA, Valentín EM & Woerpel KA Reactions of Allylmagnesium Reagents with Carbonyl Compounds and Compounds with C═N Double Bonds: Their Diastereoselectivities Generally Cannot Be Analyzed Using the Felkin–Anh and Chelation-Control Models. Chem. Rev. 120, 1513–1619 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muñoz-Bascón J, Sancho-Sanz I, Álvarez-Manzaneda E, Rosales A & Oltra JE Highly Selective Barbier-Type Propargylations and Allenylations Catalyzed by Titanocene(III). Chem. – Eur. J 18, 14479–14486 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frigerio M & Santagostino M A mild oxidizing reagent for alcohols and 1,2-diols: o-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX) in DMSO. Tetrahedron Lett. 35, 8019–8022 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery J Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Cyclizations and Couplings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 43, 3890–3908 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tasker SZ, Standley EA & Jamison TF Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 509, 299–309 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crabtree RH, & Davis MW Directing effects in homogeneous hydrogenation with [Ir(cod)(PCy3)(py)]PF6. J. Org. Chem. 51, 2655–2661 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wavefunction I Spartan 18, Irvine, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riedl RH, Heilmayer W & Spence L Nabriva Therapeutics. Process for the preparation for the preparation of Pleuromutilins. WO/2011/146954 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lykkeberg AK, Cornett C, Halling-Sørensen B & Hansen SH Isolation and structural elucidation of tiamulin metabolites formed in liver microsomes of pigs. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 42, 223–231 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lykkeberg AK, Halling-Sørensen B & Jensen LB Susceptibility of bacteria isolated from pigs to tiamulin and enrofloxacin metabolites. Vet. Microb. 121, 116–124 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marx JN & Norman LR Synthesis of (−)-acorone and related spirocyclic sesquiterpenes. J. Org. Chem. 40, 1602–1606 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ito Y, Hirao T & Saegusa T Synthesis of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds by palladium(II)-catalyzed dehydrosilylation of silyl enol ethers. J. Org. Chem. 43, 1011–1013 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shvo Y & Arisha AHI Regioselective Catalytic Dehydrogenation of Aldehydes and Ketones. J. Org. Chem. 63, 5640–5642 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bell MG et al. Eli Lilly and Company. Pyrazole Derivatives Useful as Aldolsterone Synthase Inhibitors. WO 2012/173849 Al (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakamura E, Matsuzawa S, Horiguchi Y & Kuwajima I Me3SiCl accelerated conjugate addition of stoichiometric organocopper reagents. Tetrahedron Lett. 27, 4029–4032 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito Y, Fujii S & Saegusa T Reaction of 1-silyloxybicyclo[n.1.0]alkanes with iron(III) chlorides. A facile synthesis of 2-cycloalkenones via ring enlargement of cyclic ketones. J. Org. Chem. 41, 2073–2074 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sammakia T, Jacobs JS Picolinic acid as a partner in the Mitsunobu reaction: Subsequent hydrolysis of picolinate esters under essentially neutral conditions with copper acetate in methanol. Tetrahedron Lett. 40, 2685–2688 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richter MF et al. Predictive compound accumulation rules yield a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Nature 545, 299–304 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2114513 (S3), 2114514 (19), 2114515 (26), 2114516 (S20), and 2114517 (S37). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.