Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has elicited much laboratory and clinical research attention on vaccines, mAbs, and certain small-molecule antivirals against SARS-CoV-2 infection. By contrast, there has been comparatively little attention on plant-derived compounds, especially those that are understood to be safely ingested at common doses and are frequently consumed in the diet in herbs, spices, fruits and vegetables. Examining plant secondary metabolites, we review recent elucidations into the pharmacological activity of flavonoids and other polyphenolic compounds and also survey their putative frequent-hitter behavior. Polyphenols, like many drugs, are glucuronidated post-ingestion. In an inflammatory milieu such as infection, a reversion back to the active aglycone by the release of β-glucuronidase from neutrophils and macrophages allows cellular entry of the aglycone. In the context of viral infection, virions and intracellular virus particles may be exposed to promiscuous binding by the polyphenol aglycones resulting in viral inhibition. As the mechanism’s scope would apply to the diverse range of virus species that elicit inflammation in infected hosts, we highlight pre-clinical studies of polyphenol aglycones, such as luteolin, isoginkgetin, quercetin, quercetagetin, baicalein, curcumin, fisetin and hesperetin that reduce virion replication spanning multiple distinct virus genera. It is hoped that greater awareness of the potential spatial selectivity of polyphenolic activation to sites of pathogenic infection will spur renewed research and clinical attention for natural products antiviral assaying and trialing over a wide array of infectious viral diseases.

Keywords: polyphenols, polyphenolic antiviral mechanisms, antiviral MOAs, inflammation, deglucuronidation-through-inflammation mechanism, flavonoids

Introduction

Therapies with demonstrated efficacy for infection by SARS-CoV-2, the etiological agent of the COVID-19 pandemic, include small molecule antivirals such as molnupiravir (Dyer, 2021) and nirmatrelvir (Pfizer, 2021), monoclonal antibodies (U.S.Food and Drugs Administration, 2021), and repurposed drugs such as dexamethasone and fluvoxamine (Reis et al., 2021). Monoclonal antibody therapy suffers from challenging logistics to administer. Dexamethasone has only modest effect on disease outcome (The RECOVERY Collaborative Group, 2021). Fluvoxamine remains prescribable but not yet mandated with agency approvals for COVID-19 (Leo and Erman, 2022). Researchers have called for mutagenicity studies of molnupiravir (Malone and Campbell, 2021; Masyeni et al., 2022). As SARS-CoV-2 variants continue to evolve, nirmatrelvir’s future efficacy could be impacted, including under its own selection pressure on the main protease (Zhou et al., 2022).

Persistently low worldwide vaccination rates, the potential for breakthrough infections, and the ability for vaccinated individuals to achieve viral loads sufficient to infect others (Lipsitch et al., 2021), suggest that there remains ample scope for additional safe, replication-inhibiting antivirals in the panoply of pandemic-alleviating healthcare tools.

Natural products may present a potentially untapped source of antiviral activity. Plants must resist viruses whose constituent peptides are restricted to the same repertoire of proteinogenic amino acids as peptides in mammals. Plant virus proteins share similar fundamental constraints on protein secondary and tertiary structure as viruses with mammalian hosts. Plants’ secondary metabolites are known particularly for plant-protection. Prevalent among the secondary metabolites are polyphenols. One of the three primary polyphenol classes are flavonoids (Quideau et al., 2011).

Flavonoids are a family of over eight thousand unique compounds that provide several advantages to plants (Pietta, 2000; Babu et al., 2009; Terahara, 2015). These compounds are responsible for some pigment and aroma of flowers and fruits, thereby attracting pollinators (Griesbach, 2010; Panche et al., 2016; Mathesius, 2018). Various flavonoids also protect plants from both biotic and abiotic stressors (Takahashi and Ohnishi, 2004; Kumar and Pandey, 2013; Panche et al., 2016), providing antimicrobial defenses (Treutter, 2005; Panche et al., 2016; Mathesius, 2018), acting as UV filters (Sisa et al., 2010; Panche et al., 2016; Mathesius, 2018), and serving as signaling molecules (Mierziak et al., 2014; Panche et al., 2016; Mathesius, 2018). Further, despite sparse literature on the topic, several flavonoids are also demonstrated to inhibit several plant viruses (French and Towers, 1992; Malhotra et al., 1996; Gutha et al., 2010; Likic et al., 2014; Honjo et al., 2020).

Recent research has demonstrated antiviral modes of activity for flavonoids by targeting neuraminidase (Ding et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2021), proteases (Badshah et al., 2021; Jannat et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021), and DNA/RNA polymerases (Badshah et al., 2021). Several flavonoids such as quercetin, apigenin, and luteolin reduce HCV replication through inhibition of multiple viral non-structural proteins (Ninfali et al., 2020). A flavonoid, ladanein inhibited HCV passage into human hepatocytes (Haid et al., 2012). EGCG binds to HSV viral envelope glycoproteins gB and gD, inactivating the virions (Zakaryan et al., 2017). Lalani and Poh (2020)’s survey of flavonoid antiviral studies demonstrated that inhibition of viral enzymes and proteins is the most frequently identified mechanism of action against non-picornaviruses (Lalani and Poh, 2020). Flavonoid compounds from Sambucus nigra L. [Adoxaceae] extract were shown to inhibit H1N1 infection by binding to the viral envelope blocking entry into host cells (Roschek et al., 2009). Quercetin demonstrated anti-infective and anti-replicative activity in four different virus species (Middleton, 1998). Quercetin also blocks viral binding and penetration to the host cell in HSV (Zakaryan et al., 2017).

In a recent paper on the antiviral effects of flavonoids, Liskova et al. (2021) review the antiviral mechanisms of action for several flavonoids. For example, caflanone (from Cannabis sativa L.-- Cannabaceae) pleiotropically inhibits viral entry factors such as ABL-2, cathepsin L, PI4Kiiiβ and AXL-2, which facilitate mother-to-fetus transmission of coronavirus (Ngwa et al., 2020). In addition, caflanone shows multi-modal anti-inflammatory activity through the inhibition of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and Mip-1α (Ngwa et al., 2020). Other flavonoids show anti-inflammatory activity through direct inhibition of NFκB (Rathee et al., 2009). Caflanone, and other flavonoids such as equivir, hesperetin, and myricetin also bind at high affinity to the helicase spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, as well as protease cleavage sites on the ACE2 receptor (Ngwa et al., 2020).

The antiviral effect of Pelargonium sidoides DC. [Geraniaceae], also known as umckaloaba, has been found to predominantly depend on the polyphenols, namely the flavonoids and oligomeric proanthocyanidins (Helfer et al., 2014). These compounds have been shown to directly interfere with the infectivity of HIV-1 particles before they interact with the host cell in a polyvalent manner. For instance, the flavonoid/anthocyanidin fraction of P. sidoides inhibited attachment of virus particles to cells by inhibiting the early viral proteins of Tat and Rev (positive regulators of gene expression) and inhibited the release of infectious virions. In addition, P. sidoides extracts demonstrated a strong reduction of input viral RNA levels in virus-exposed cells. In addition, the previously mentioned flavonoids target HIV-1 envelope proteins (X4 (LAI) and R5 (AD8 and JRFL), thereby inhibiting HIV-1 entry by interfering with the function of the envelope proteins (Helfer et al., 2014).

In ex-vivo investigations in rhinovirus-infected cells isolated from patients with severe asthma, moderate COPD, and disease-free controls, a P. sidioides extract (standardized to oligomeric prodelphinidins, a type of flavonoid) concentration-dependently demonstrated significantly increased human bronchial epithelial cell survival and decreased expression of inducible co-stimulator (ICOS) and its ligand ICOSL, as well as cell surface calreticulin. In both infected and uninfected, rhinovirus B-defensin-1 and suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS1) were up-regulated suggesting a mode of activity for these flavonoid-rich extracts (Roth et al., 2019).

Clinical trials and in vivo models of P. sidoides flavonoid rich extracts have shown significant efficacy in treating uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) (Gökçe et al., 2021), URIs in asthmatic children (Patiroglu et al., 2012; Tahan and Yaman, 2013), acute bronchitis (Kamin et al., 2010; Kamin et al., 2012), and reduction in bacterial infection via immunomodulatory activity (Bao et al., 2015).

Besides the discussed anti-inflammatory activity, there is other immunomodulatory activity of flavonoids which has been reviewed elsewhere (Roshanravan et al., 2020; Liskova et al., 2021; Han et al., 2022). Besides the cytokine inhibition, cytokines have other roles that may significantly affect immune function. For example, the ubiquitous occurring quercetin and its glycoside rutin, have been found to facilitate the shift of macrophages from a proinflammatory to an anti-inflammatory phenotype (Bispo da Silva et al., 2017; Zaragozá et al., 2020). Additionally, apigenin, luteolin, and quercetin show significant immunomodulatory actions on natural killer cell cytotoxicity activity and granule secretion (Oo et al., 2021). Quercetin has also demonstrated a decreased in the expression levels of the major histocompatibility complex class two (MHC II) and costimulatory molecules resulting in a marked reduction of T cell activation (Huang et al., 2010). Finally, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells treated with quercetin preferentially induced interferon gamma (IFN-γ) expression and synthesis while inhibiting IL-4 production resulting in a differential activation of Th1 cells, suggesting potential anti-tumor activity (Nair et al., 2002).

A frequent target of coronavirus antivirals is the SARS-CoV-2 main protease, owing especially to the successful history of protease inhibitors on reducing HIV replication. Several polyphenols showed potent antiviral activity to SARS-CoV’s main protease (Lin et al., 2005; Ryu et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013; Jo et al., 2020). Among these, the polyphenolic flavonoid hesperetin (1) was unique in potently inhibiting the action of the main protease in cell-based assay (Lin et al., 2005). Hesperetin dose-dependently inhibited cleavage activity of the 3CLpro in expressed in Vero E6 cells with an IC50 of 8.3 μM (Lin et al., 2005).

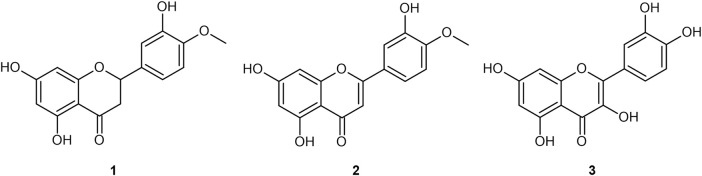

However, polyphenols like hesperetin are disfavored by industrial medicinal chemists for proceeding through the hit-to-lead (H2L) stage of the drug discovery pipeline (Lowe, 2020; Lowe, 2021). Polyphenols are categorized among the Pan-Assay INterference compounds (PAINs) (Lowe, 2012) [other terms are “frequent-hitters”, “promiscuous inhibitors”, “privileged structures/scaffolds”, and “invalid metabolic panaceas” (Bisson et al., 2016)], and are suggested to obscure the results of various assays. They also bind broadly to assays’ protein targets themselves. Selected examples of polyphenol aglycones are provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Four flavonoid aglycones referenced in the present work: hesperetin (1); diosmetin (2); quercetin (3).

Due to the ongoing pressing need for further COVID treatment strategies, we review the pharmacokinetic and putative frequent-hitting behavior of polyphenols’ as a class with an eye toward ascertaining 1) their potential as an antiviral 2) whether or not polyphenols simultaneously should pose risks to ordinary healthy cellular processes.

What defines a polyphenol?

While IUPAC has defined the term “phenols” (Gold, 2019), a definition of polyphenols remains yet to be formally accepted. Quideau (2011) explored definitions of polyphenols extensively, providing an applicable description:

“The term “polyphenol” should be used to define plant secondary metabolites derived exclusively from the shikimate-derived phenylpropanoid and/or the polyketide pathway(s), featuring more than one phenolic ring and being devoid of any nitrogen-based functional group in their most basic structural expression.” (Quideau et al., 2011)

Describing polyphenols in part based on their provenance provides excellent exclusivity. However, one could question whether it is helpful to exclude phenols such as acacetin which have only one phenolic ring. For large-scale cheminformatic purposes, which challenge the application of biosynthesis pathway criteria, an applicable definition may be to treat polyphenols as any molecule with more than one phenolic ring but lacking elements other than C, H, and O.

Poor polyphenol PK perception

The therapeutic efficacy of any antiviral whose purpose is to reduce viral replication requires maintaining an efficacious concentration of the ligand at its putative target for an extended period of time. Conservatively, this period should ideally be of long duration relative to a virus’s replication time to reach peak viral load. An interval typically measured in days in the case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans (Kissler et al., 2021).

However, polyphenolic compounds’ potential for efficacy for any particular pathology is criticized due to a prima facie poor pharmacokinetic ADMET profile. Consider, for example, diosmetin (2). A primary intermediate metabolite of the pharmaceutical formulation known as Daflon (comprised of 90% diosmin, and 10% other flavonoids expressed as hesperidin, diosmetin, linarin, and isorhoifolin), and similarly proportioned formulations are prescribed in many countries around the world for chronic venous insufficiency (CVI).

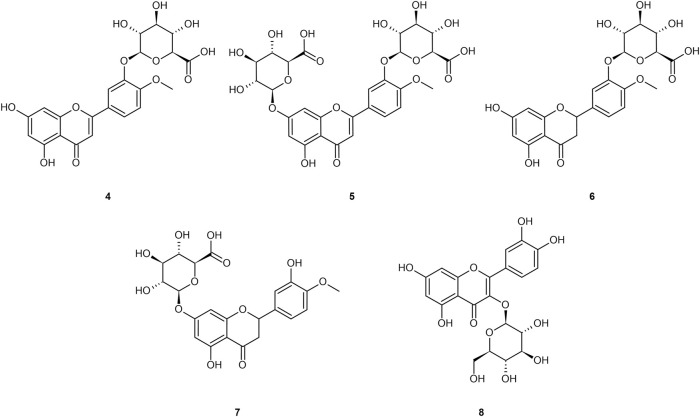

Ingested diosmin becomes diosmetin through Phase I metabolism through the intestinal wall, and then is either glucuronidated (primarily) to glucuronides (4 and 5), sulfated, or methylated through Phase II metabolism in the liver (Boutin et al., 1993; Meyer, 1994; Struckmann and Nicolaides, 1994; Spanakis et al., 2009; Campanero et al., 2010; Patel et al., 2013; Silvestro et al., 2013; Russo et al., 2015; Russo et al., 2018; Mandal et al., 2019; Bajraktari and Weiss, 2020). Serum analysis on healthy individuals demonstrates negligible presence of the aglycone in plasma, and low sustained levels of the diosmetin conjugates (primarily glucuronides) in plasma, with tmax of 2.3 h and t1/2 ranging from 8–70 h (Boutin et al., 1993; Struckmann and Nicolaides, 1994; Spanakis et al., 2009; Campanero et al., 2010; Silvestro et al., 2013; Russo et al., 2015; Russo et al., 2018; Mandal et al., 2019; Bajraktari and Weiss, 2020). Stachulski and Meng (2013) and Tranoy-Opalinski et al. (2014) noted that most glucuronides are rapidly eliminated by the kidneys, posing an apparent limitation to their efficacy (Tranoy-Opalinski et al., 2014). Glucuronidation further reduces bioavailability to the intracellular compartment as the glucuronide moiety imparts a hydrophilicity that prevents cellular uptake (Tranoy-Opalinski et al., 2014). Glucuronides of the aglycones from Figure 1 are presented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Common glucuronide metabolites of the referenced aglycones: diosmetin-3′-O-glucuronide (4); diosmetin-3′-7-O-glucuronide (5); hesperetin-3′-O-glucuronide (6); hesperetin-7–O-glucuronide (7); quercetin-3-O-glucuronide (8).

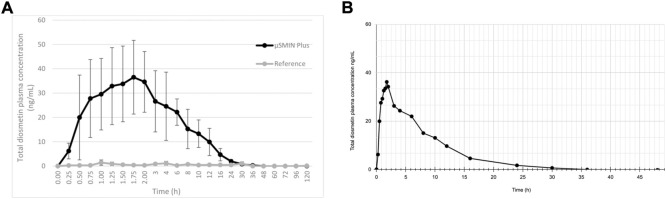

Note that a similar metabolic pathway can be described for other flavonoid aglycones. In the case of hesperidin, it is hydrolyzed to hesperetin, ultimately primarily becoming glucuronides (6 and 7) or quercetin, primarily to glucuronide (8). Russo et al. (2018) provided a prototypical example of flavonoid plasma pharmacokinetics as demonstrated by diosmetin, which is reproduced and linearized in Figures 3A,B, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

(A) Diosmetin plasma concentration (as ascertained following deglucuronidation), after administration of a 50 mg/kg micronized diosmin formulation to rats. Image licensed under CC by 4.0 from Russo et al. (2018) (Russo et al., 2018). (B) same plot with linearized axes.

Yet to our knowledge 1) no quantitative bioavailability assays of diosmetin have taken place in non-plasma compartments such as extracellular fluid and tissue in humans; 2) tissue distribution studies of flavonoids in animal models are few. More in vivo distribution data to support therapeutic insights into polyphenols would be valuable.

Drawbacks of polyphenol PK analysis

On broader review of the polyphenol pharmacokinetic literature, five insights about pharmacological assays emerge:

1. The most commonly obtained pharmacological assay for concentration of polyphenols or their metabolites is blood plasma analysis, rather than interstitial fluid or intracellular fluid (Tozer, 1981; Ueno et al., 1983; Boutin et al., 1993; Meyer, 1994; Struckmann and Nicolaides, 1994; Walle et al., 2001; Spanakis et al., 2009; Campanero et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2010; Kaushik et al., 2012; Takumi et al., 2012; Patel et al., 2013; Silvestro et al., 2013; Russo et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2016; Nikiforov, 2017; HealthTech and de Zeneta, 2018; Russo et al., 2018; Mandal et al., 2019; Bajraktari and Weiss, 2020; Hai et al., 2020).

2. A polyphenol’s plasma concentration profile alone provides no data on tissue distribution or biotransformation (Tozer, 1981; Walle et al., 2001; Ratain and Plunkett, 2003).

3. It is very difficult to sample intracellular fluid for drug/metabolite concentration profiling to the exclusion of extracellular and serum fluid (Lowe, 2018; Lowe, 2019).

4. Even radiolabeled assaying of all possible elimination routes fails to provide a complete accounting of polyphenol dosage intake (Walle et al., 2001).

5. Plasma samples of polyphenols are more frequently obtained from healthy individuals, rather than those suffering from a particular pathology (Ueno et al., 1983; Boutin et al., 1993; Meyer, 1994; Struckmann and Nicolaides, 1994; Walle et al., 2001; Spanakis et al., 2009; Campanero et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2010; Kaushik et al., 2012; Takumi et al., 2012; Patel et al., 2013; Silvestro et al., 2013; Russo et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2016; Nikiforov, 2017; HealthTech and de Zeneta, 2018; Russo et al., 2018; Mandal et al., 2019; Bajraktari and Weiss, 2020; Hai et al., 2020).

Therefore, if any particular pharmaceutical candidate’s PK profile achieves significant distribution in organs other than those associated with either the GI tract or renal tract, it would be unascertainable from serum analysis alone. Further, if any particular pathology has an effect on a compound’s tissue distribution (whether by causing sequestering in sanctuary sites, or adduct formation with the target in tissue both of which represent an increase in the volume of distribution), then plasma analysis alone remains poorly positioned to provide the relevant readout. Rather, tissue analysis in sacrificed animal models, or comprehensive radiolabeled elimination quantitation in humans, would be required.

Walle et al. (2001) demonstrated such a radiolabeled analysis. Notably, they found that carbon dioxide was a major metabolite of quercetin (3) in humans, (Walle et al., 2001) suggesting a rarer elimination pathway than typically encountered by pharmacological analysis. Even with this exotic elimination route taken into account, the full dose of quercetin was not always fully representative of the dose given. One can speculate that sequestration of quercetin products in tissue compartments was maintained past the 72-hr study period.

Moreover, while de Boer et al. (2005) and Bieger et al. (2008) demonstrated that quercetin reaches certain tissues other than those associated with GI and renal tracts in healthy animal models, these studies do not address any putative bioavailability of flavonoids uniquely to tissue affected by diseased circumstances.

Toward resolving the “flavonoid paradox”

To begin addressing these pharmacokinetic challenges, we examine them through the lens of a subtle but critically important feature of the pharmacokinetic profile of polyphenols, such as flavonoids, as elucidated by the literature.

Menendez et al. and Perez-Vicaino et al. frame flavonoids’ pharmacokinetic challenges in the context of a “flavonoid paradox” (Menendez et al., 2011; Perez-Vizcaino et al., 2012). The paradox can be summarized as the observation that several flavonoid polyphenols have been shown to demonstrate therapeutic effects for various pathologies in vivo, and yet their pharmacological profiles suggest poor bioavailability, including the difficulty of glucuronide metabolites to pass through cell membranes, along with rapid plasma clearance.

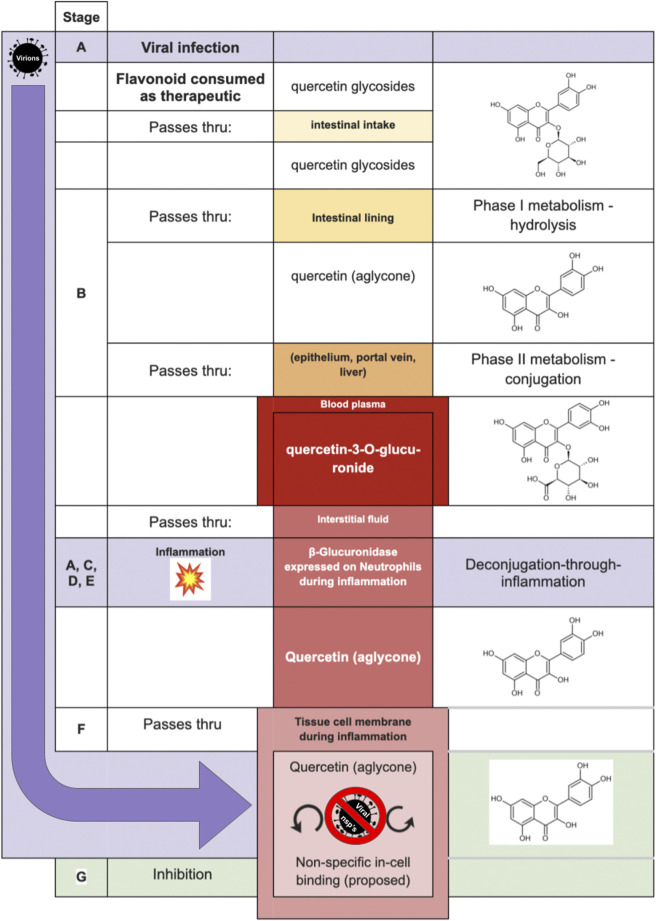

Investigators (Marshall et al., 1988; Shimoi et al., 2000; O’Leary et al., 2001; Shimoi et al., 2001; Shimoi and Nakayama, 2005; Kawai et al., 2008; Bartholomé et al., 2010; Menendez et al., 2011; Galindo et al., 2012; Ishisaka et al., 2013; Kaneko et al., 2017; Piwowarski et al., 2017; Ávila-Gálvez et al., 2019) of the following deconjugation mechanism offer a resolution to the flavonoid paradox: During inflammation (as happens during infection of several etiologies), phagocytes arrive at the extracellular fluid surrounding the sites of inflammation. The phagocytes express β-glucuronidase which accomplishes deglucuronidation (also known as deconjugation) of the flavonoid glucuronide into its aglycone form. The deconjugated flavonoid aglycone subsequently diffuses through the cell membrane where they can reach their target. The mechanism is summarized in Table 1. For purposes of this review, the mechanism steps are labeled stages B, C, D, E, and F.

TABLE 1.

Deglucuronidation-through-inflammation mechanism steps.

| Stage B—Flavonoid aglycones are glucuronidated prior to arrival in the bloodstream |

| ↓ |

| Stage C—Neutrophils and macrophages are attracted to site(s) of inflammation |

| ↓ |

| Stage D—β-glucuronidase is expressed by neutrophils and macrophages |

| ↓ |

| Stage E—Serum flavonoid glucuronides are deglucuronidated (‘deconjugated’) by β-glucuronidase at site of inflammation |

| ↓ |

| Stage F—Flavonoid aglycones diffuse through cell membrane |

Comparable pathology-specific activation of glucuronide drugs by β-glucuronidase has been examined and exploited in the context of anti-tumor agents (Tranoy-Opalinski et al., 2014). However, it is the “deconjugation in inflammation hypothesis” that was developed and supported progressively over the period 2000–2019 across several polyphenols in vitro, in animal models, and in humans that describes flavonoid conversion to cell-penetrating forms uniquely under inflammatory conditions (Marshall et al., 1988; Shimoi et al., 2000; O’Leary et al., 2001; Shimoi et al., 2001; Shimoi and Nakayama, 2005; Kawai et al., 2008; Bartholomé et al., 2010; Menendez et al., 2011; Galindo et al., 2012; Ishisaka et al., 2013; Kaneko et al., 2017; Piwowarski et al., 2017; Ávila-Gálvez et al., 2019).

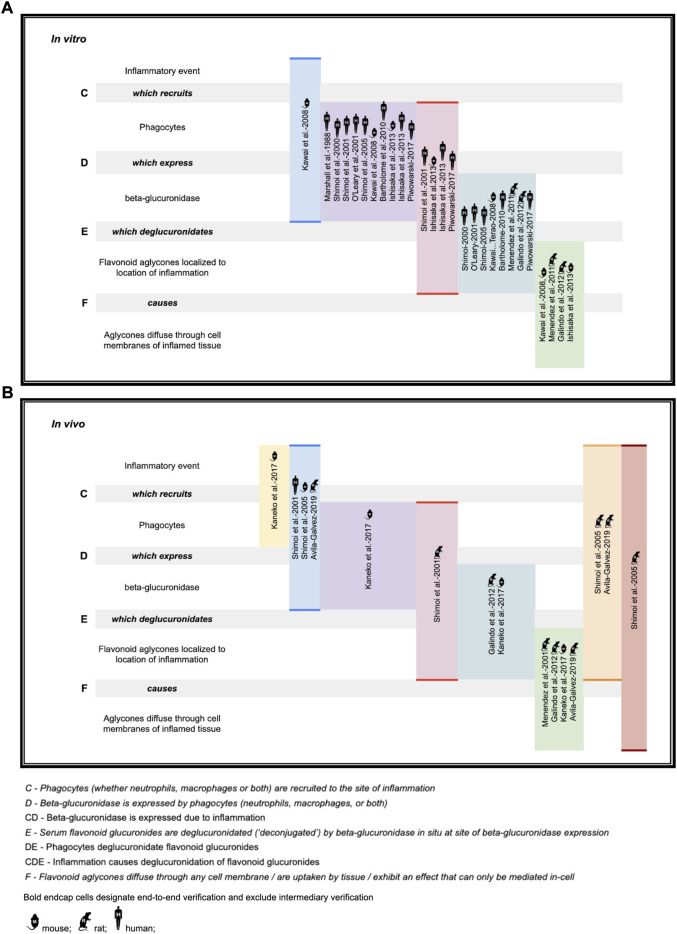

While the deglucuronidation-through-inflammation hypothesis has been reviewed extensively by others, (Terao et al., 2011; Perez-Vizcaino et al., 2012; Kawai, 2014; Kawabata et al., 2015; Terao, 2017; Kawai, 2018) to our knowledge, this review is the first to unify the body of work into one cohesive, accessible evidentiary framework. Demonstration of the evidence generated through the deglucuronidation-through-inflammation body of work, (Marshall et al., 1988; Shimoi et al., 2000; O’Leary et al., 2001; Shimoi et al., 2001; Shimoi and Nakayama, 2005; Kawai et al., 2008; Bartholomé et al., 2010; Menendez et al., 2011; Galindo et al., 2012; Ishisaka et al., 2013; Kaneko et al., 2017; Piwowarski et al., 2017; Ávila-Gálvez et al., 2019) is provided against the model’s labeled stages C-F in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Deconjugation-through-inflammation literature basis (A) in vitro support (B) in vivo support.

Figure 4 illustrates the body of deglucuronidation-through-inflammation literature thusly: Original research investigators produced results demonstrating any one of the four stages of the mechanism (which we refer to here as steps C, D, E, F), the entire mechanism (CDEF), or consecutive combinations of steps (such as CD, CDE). We highlight whether evidence for an individual step has been produced, or instead over multiple consecutive steps end-to-end (without isolated verification of any intermediate step). Consecutive step verifications are illustrated by highlighting in bold the top and bottom of the relevant cells.

The figure annotates whether experiments have been performed in vitro (using mice, rat, or human cell lines) or in vivo in mice models, rat models, or humans. While steps of the pathway were verified across the polyphenols luteolin (Shimoi et al., 2000; Shimoi et al., 2001; Shimoi and Nakayama, 2005), quercetin (O’Leary et al., 2001; Bartholomé et al., 2010; Menendez et al., 2011; Galindo et al., 2012; Ishisaka et al., 2013; Kawai, 2014), daidzein (O’Leary et al., 2001), and kaempferol (O’Leary et al., 2001), as well as the ellagic acid metabolites urolithin A (Piwowarski et al., 2017; Ávila-Gálvez et al., 2019; Bobowska et al., 2021), iso-urolithin A (Piwowarski et al., 2017; Bobowska et al., 2021), and the single-phenol urolithin B (Piwowarski et al., 2017; Bobowska et al., 2021), these are not annotated in the figure for brevity.

We believe the figure also adds value as it makes clear which steps are already demonstrated so that they can undergo simpler replication studies, as well as identifying which steps, such as in vivo human verification work at stages DEF, could be better elucidated with fresh original research.

We propose standardizing the mechanism’s naming to the technical term “deglucuronidation-through-inflammation” or DTI. The term ‘Shimoi pathway’ further serves as a convenient shorthand that recognizes the lead researcher to first propose and study this mechanism with specific attention to inflammation with polyphenols.

The promiscuous inhibition of polyphenols

Promiscuous inhibition poses two primary implications for medicinal chemistry assaying. The first is the non-specific binding of protein/enzyme targets themselves. The second is the disruption of assay integrity by inhibiting non-target enzymes used for assay readout. As it can be difficult to distinguish between these two, orthogonal assays are sometimes performed to verify a target binding interaction.

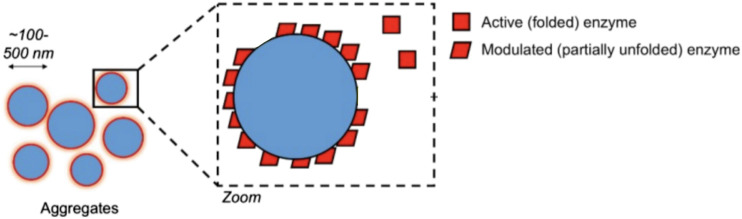

Promiscuity could take any of several forms. A promiscuous ligand could simply be highly conforming to a protein surface’s geometry, with a high number of hydrogen donors & acceptors to more likely “stick” nonspecifically to any given protein site’s own set of H-donors and H-acceptors. Another mechanism sees promiscuous inhibition take the form of colloidal aggregations (Shoichet, 2006). In this mechanism, upon reaching a certain concentration, the ligand forms tightly-packed spherical aggregates with itself, even inside the cell (Ganesh et al., 2017; Shoichet, 2021) as illustrated in Figure 5. Proteins and enzymes non-specifically bind to the surface of the aggregation and are inhibited in the process (Auld et al., 2017). Often seen as a nuisance originally, it is now also seen as a source of opportunity in drug discovery as well (Ganesh et al., 2017; Ganesh et al., 2018; Ganesh et al., 2019). Deliberate study of aggregation in cell-based assays is a nascent sub-field, (Owen et al., 2012) thus cataloguing of non-specific aggregation among polyphenols in cells merits further investigation.

FIGURE 5.

Non-selective aggregation inhibition model. Figure modified from Auld et al. (2017) for clarity under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Quercetin has earned a reputation as a promiscuous inhibitor (Pohjala and Tammela, 2012; Jasial et al., 2016a; Gilberg et al., 2019; Lowe, 2020) as well as having served as one of the first aggregators identified. (McGovern et al., 2002; McGovern and Shoichet, 2003; Shoichet, 2006). Luteolin (Jasial et al., 2016a), curcumin (Jasial et al., 2016a), myricetin (Pohjala and Tammela, 2012; Jasial et al., 2016a; Jasial et al., 2016b; Gilberg et al., 2018; O’Donnell et al., 2021), and tannic acid (Pohjala and Tammela, 2012; Jasial et al., 2016a) are also promiscuous inhibitors, where myricetin and tannic acid have been further identified as aggregators (Pohjala and Tammela, 2012).

Of 123,844 assay records hosted by Pubchem and compiled by Gilberg et al. (2016) (Gilberg et al., 2016), their isolation of the most promiscuous 466 of them (99.6% percentile) contains 13 polyphenols based on our cheminformatic-oriented definition.

The catechol functional group, while not the exclusive province of polyphenols (and nor do polyphenols all contain catechol), certainly correlates with polyphenols. Bael and Holloway (2010), highlights catechol as a prominent PAINS functional group (Baell and Holloway, 2010) even as Capuzzi et al. (2017) cautions against blind application of PAINS filters. (Capuzzi et al., 2017). And yet Jasial et al. (2017) demonstrates that the catechol functional group is in the top ten percentile (9.5) of primary activity assays in Pubchem, and in the top seven percentile (6.9) of functional groups in Pubchem confirmatory assay activity (Jasial et al., 2017).

Therapeutic role of a promiscuous binder?

The final step of a putative polyphenol deglucuronidation-based antiviral mechanism requires that a promiscuous-binding compound once inside a virus-infected human cell will arrest viable virion production. The complete proposed mechanism is presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Proposed deglucuronidation-based antiviral mechanism.

| Stage A—Infection by any of several virus species induces inflammation |

| ↓ |

| Stage B—Flavonoid aglycones are glucuronidated prior to arrival in the bloodstream |

| ↓ |

| Stage C—Neutrophils and macrophages are attracted to site(s) of inflammation |

| ↓ |

| Stage D—β-glucuronidase is expressed by neutrophils and macrophages |

| ↓ |

| Stage E—Serum flavonoid glucuronides are deglucuronidated (“deconjugated”) by β-glucuronidase at site of inflammation |

| ↓ |

| Stage F—Flavonoid aglycones diffuse through cell membrane |

| ↓ |

| Stage G—Flavonoid aglycones cause non-selective (and non-specific) inhibition within the cell—interfering with both ordinary cellular processes and the etiological source of inflammation (such as viral replication) |

Table 2 is illustrated graphically in Figure 6—by way of one of the most studied flavonoids in the pharmacokinetic literature, quercetin. Inhibitory mechanisms of viral replication could be due to direct inhibition of viral proteins and enzymes, or by slowing ordinary cellular metabolic mechanisms such as respiration, translation, transcription as co-opted by the infecting virus. In one case, that of fisetin applied to Dengue fever, (Zandi et al., 2011a) fisetin showed no direct activity against DENV virions outside the cell yet effectively inhibited replication in-cell. The study’s authors suggest it could be due to forming complexes with RNA or inhibition of RNA polymerases. While inhibition of the dengue RdRp would represent a virus-specific inhibition, it remains intriguing to consider that the replication inhibition could also be due to general non-selective inhibition in a weakened cell.

FIGURE 6.

Proposed model of Shimoi mechanism for entry into intracellular compartment during viral infection, with quercetin serving in the role of the aglycone, and quercetin-3-O-glucuronide as the glucuronide [adapted from Perez-Vizcaino et al. (2012)].

Application of deglucuronidation-through-inflammation to antiviral assaying and clinical trialing

Given that many forms of viral infections are known to induce inflammation, it would be a logical extension to study whether consumption of certain flavonoids of sufficient quantity and in bioavailable forms could serve to reduce the rate of viral replication in the early stages of viral infection. The mechanism of action could be by inhibition of viral entry to cells, direct inhibitory action on viral enzymes in-cell, or non-specific promiscuous disruption of the co-opted metabolism of infected cells.

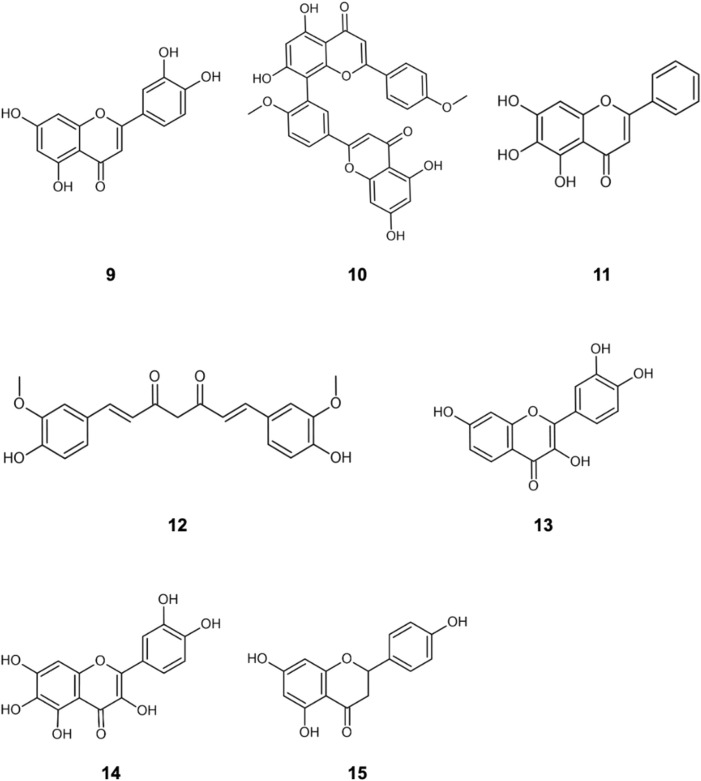

The literature provides early in vitro evidence of achievable inhibition by phenolic flavonoids spanning across Dengue virus, Influenza-A virus (IAV), Chikungunya virus, Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV), Japaneses Encephalitus Virus (JEV) and SARS-CoV-2, presented in Table 3. Corresponding ligand structures are available in Figure 1 and Figure 7.

TABLE 3.

in vitro evidence of in-cell viral inhibition (reported IC50) by phenols and polyphenols.

One phenol only.

FIGURE 7.

Additionally referenced polyphenols: luteolin (9); Isoginkgetin (10); baicalein (11); curcumin (12); fisetin (13); quercetagetin (14); naringenin (15).

Much care must be applied in interpreting in vitro viral replication inhibition results. Where an IC50 value is defined against a measure of viral RNA copies/mL, then qRT-PCR will show a difference of a single unit of Ct. For comparison, SARS-CoV-2 infection typically presents a Ct range between 10 and 40 for acute infection vs. non-detectable viral load, respectively (Kissler et al., 2021). However, in vitro and in vivo Ct values are not directly comparable, as in vitro reduction of viral replication may exhibit nonlinear effects at the in vivo scale, especially when the effects of the innate and specific immune system are considered. Where due analysis of toxicity allows, a higher IC value can be targeted, such as IC90 or even IC99 (Rusconi et al., 1994).

Viral inhibitory assays typically report the Selectivity Index (SI), defined as the ratio of the cytotoxicity (CC50) to the inhibitory concentration (IC50). A SI < 1 means that the ligand’s cytotoxicity to cells occurs at a lower concentration than its inhibition of the target. Selectivity indices of 5 or greater are preferred. Ligand candidates suffering from lower selectivity indices may be excluded from further investigation. However, the deglucuronidation-through-inflammation mechanism would suggest that dismissing polyphenol ligands with a low selectivity index could be overly conservative. Given that polyphenols circulate in plasma primarily as glucuronides, (Boutin et al., 1993; Shimoi et al., 1998; Kuhnle et al., 2000; Shimoi et al., 2000; O’Leary et al., 2001; Manach et al., 2003; Campanero et al., 2010; Silvestro et al., 2013; Russo et al., 2015; Russo et al., 2018; Bajraktari and Weiss, 2020; Hai et al., 2020) a low selectivity index for the aglycone may not only be acceptable but may even be preferable. This of course will depend on how efficiently the deglucuronidation process discriminates between the localities of healthy and infected cells that induce the inflammatory process.

Given the selectivity that deglucuronidation-through-inflammation affords, and the putative validity of aggregation-based non-selective binding mechanisms, (Shoichet, 2021) the standard practice of applying aggregate-dissociating detergents such as Triton X-100 is called into question for antiviral assays of phenols that are known or expected to act through the DTI mechanism. A revisiting of relevant results of in vitro assays in the literature where such a detergent was applied would be appropriate. However, such a modification to laboratory practice should be considered carefully as the tendency for an aggregation to bind assay-specific enzymes could still benefit from detergent application.

Non-selective inhibition can be a double-edged sword. Dong (2014) demonstrates that the aglycone kaempferol increased IAV viral titers by log-2 compared with untreated mice, hastening their loss (Dong et al., 2014). This was attributed to attenuation of antiviral host-defense factor expression such as IFNα, IFNβ, IFNγ. By contrast, hesperidin was protective of the mice. Further laboratory and clinical investigation of demonstrably promiscuous-binding polyphenols utilizing in vitro viral infection culture and in vivo models will continue to be valuable. Attention would be particularly appropriate against those viruses that are known to induce inflammatory responses such as influenza A (IAV-A), dengue (DENV), chikungunya (CHIKV), and coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).

Additional observations on antivirals trialing of polyphenols

While it is important to maintain ligand concentration at the target for a period sufficient to exert the relevant mechanism of action, it is worth noting that this period can be extremely short. Although not a polyphenol, artemisinin enjoys enormous efficacy against the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum with a Tmax at less than 2 h and a half-life of 2–5 h (Benakis et al., 1997; de Vries and Dien, 2021). Also, the dosage is of utmost importance. Following due analysis of toxicity, protease inhibitors can target a Cmin dose (minimum concentration between consecutive doses) of many multiples of the IC50 value (Boras et al., 2021) to achieve faster viral clearance. Indirect antiviral effects of certain polyphenols may also be possible, such as non-specific upregulation of immunosurveillance, as well as modulation of specific immune cells (Liu et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2021; Syafni et al., 2021).

Also, as promiscuous binders, due attention should be applied to inhibition of liver enzymes for drug-drug interactions (Bajraktari and Weiss, 2020), especially of drugs that study subjects might concomitantly consume for the same or unrelated conditions. For example, among the polyphenols studied are those known to bind to CYP1A2 (Bajraktari and Weiss, 2020), CYP3A4 (Bajraktari and Weiss, 2020) and OATP1A2, the latter giving rise to the famous “grapefruit effect” (Bailey et al., 2007). Conversely, this P450 or other liver enzyme inhibition may be advantageous to increase serum concentrations of verified pharmaceuticals, such as fluvoxamine, in context of combination therapy (James Duke, personal communication, 28 November 2009) for superior joint bioavailability.

Finally, as a given polyphenol can demonstrate differing bioavailabilities between different dosage forms, (Kaushik et al., 2012) consideration should also be given to oral delivery type, such as aqueous, softgel, dry tablet form, and degree of micronization. Further, owing to strong bioavailability and/or release rate, delivery in the form of original plant matter while controlling for phytochemical content should also be considered (Kawai et al., 2008; Inoue et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2017).

Evolutionary role

A BLAST search demonstrates that the gene coding for β-glucuronidase [GUSB, and uidA in bacteria (Martins et al., 1993)] is extensively common across the animal kingdom (data not shown). Its homolog β-galactosidase (40% identity) is also commonly expressed in bacteria (data not shown). β-glucuronidase has several documented purposes (Martins et al., 1993). It targets glucuronic acid in the gut, (Wallace et al., 2015; Dashnyam et al., 2018) and is associated with the degradation of glucuronate-containing glycosaminoglycan (Naz et al., 2013). But its extensive expression on, and release from, neutrophils attracted in response to inflammatory signals is a mechanism whose genetic etiology and species prevalence will require further work to elucidate.

Given the long history of herbivory in animals (and associated polyphenolic compound ingestion), and the high prevalence frequency of the β-glucuronidase-coding gene GUSB across vertebrates, this mechanism could be a long-ago evolved broad response under selection pressure of viral pathologies in ancestral species. It would be worthwhile for future investigators to probe the genetic basis for neutrophilic β-glucuronidase expression and its orthology across vertebrate species in order to better localize how this response evolved.

Conclusion

In this paper, we add to the body of evidence in the literature that polyphenols are a frequent-binding class of chemicals produced by plants. We show that the pharmacology of polyphenols may allow for viral infection-fighting potential due to the human body’s inflammatory response and provide conjecture as to the evolutionary basis for a putative inflammation-induced antiviral function. Future work could include quantifying the effect of in vitro antiviral studies under inflammation with neutrophils present for such viral targets as SARS-CoV-2, CHIKV, DENV, and IAV/IBV.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stéphane Quideau PhD, Jurgen Bajorath PhD, Pamela Weathers PhD, Brian Shoichet PhD, Pierre Laurin PhD, and Scott Ferguson PhD for helpful tips in the course of the preparation of this manuscript; and Yu Wai Chen PhD, Francisco Perez-Vizcaino PhD, and Erik de Clercq PhD for encouragement, and would especially like to recognize and appreciate Stephen Molnar PhD for insights and reviewing drafts of this manuscript. We are indebted to Fabiola de Marchi PhD for expert chemical structure graphic drafting. Finally, we would like to thank Priyanshu Jain for unflagging support and encouragement in the course of preparation.

Author contributions

RS and KS contributed to conception of the review. RS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KS wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by EMSKE Phytochem.

Conflict of interest

Author RS was employed by EMSKE Phytochem.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Advanced chemistry development (2016). Inc. ACD/ChemSketch. Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi A., Hassandarvish P., Lani R., Yadollahi P., Jokar A., Bakar S. A., et al. (2016). Inhibition of chikungunya virus replication by hesperetin and naringenin. RSC Adv. 6 (73), 69421–69430. 10.1039/C6RA16640G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auld D. S., Inglese J., Dahlin J. L. (2017). “Assay interference by aggregation,” in Assay guidance manual. Editors Markossian S., Grossman A., Brimacombe K., Arkin M., Auld D., Austin C. P., et al. (Bethesda (MD): Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Gálvez M. A., Giménez-Bastida J. A., González-Sarrías A., Espín J. C. (2019). Tissue deconjugation of urolithin A glucuronide to free urolithin A in systemic inflammation. Food Funct. 10 (6), 3135–3141. 10.1039/C9FO00298G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu P. V. A., Liu D. (2009). “Chapter 18 - flavonoids and cardiovascular Health,” in Complementary and alternative therapies and the aging population. Editor Watson R. R. (San Diego: Academic Press; ), 371–392. 10.1016/B978-0-12-374228-5.00018-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badshah S. L., Faisal S., Muhammad A., Poulson B. G., Emwas A. H., Jaremko M. (2021). Antiviral activities of flavonoids. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 140, 111596. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell J. B., Holloway G. A. (2010). New substructure filters for removal of Pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 53 (7), 2719–2740. 10.1021/jm901137j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D. G., Dresser G. K., Leake B. F., Kim R. B. (2007). Naringin is a major and selective clinical inhibitor of organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1A2 (OATP1A2) in grapefruit juice. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 81 (4), 495–502. 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajraktari G., Weiss J. (2020). The aglycone diosmetin has the higher perpetrator drug-drug interaction potential compared to the parent flavone diosmin. J. Funct. Foods 67, 103842. 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian A., Pilankatta R., Teramoto T., Sajith A. M., Nwulia E., Kulkarni A., et al. (2019). Inhibition of dengue virus by curcuminoids. Antivir. Res. 162, 71–78. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y., Gao Y., Koch E., Pan X., Jin Y., Cui X. (2015). Evaluation of pharmacodynamic activities of EPs 7630, a special extract from roots of Pelargonium sidoides, in animals models of cough, secretolytic activity and acute bronchitis. Phytomedicine 22 (4), 504–509. 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomé R., Haenen G., Hollman P. C. H., Bast A., Dagnelie P. C., Roos D., et al. (2010). Deconjugation kinetics of glucuronidated Phase II flavonoid metabolites by β-glucuronidase from neutrophils. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 25 (4), 379–387. 10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-10-RG-002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benakis A., Paris M., Loutan L., Plessas C. T., Plessas S. T. (1997). Pharmacokinetics of artemisinin and artesunate after oral administration in healthy volunteers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56 (1), 17–23. 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieger J., Cermak R., Blank R., de Boer V. C. J., Hollman P. C. H., et al. (2008). Tissue distribution of quercetin in pigs after long-term dietary supplementation. J. Nutr. 138 (8), 1417–1420. 10.1093/jn/138.8.1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bispo da Silva A., Cerqueira Coelho P. L., Alves Oliveira Amparo J., Alves de Almeida Carneiro M. M., Pereira Borges J. M., Dos Santos Souza C., et al. (2017). The flavonoid rutin modulates microglial/macrophage activation to a CD150/CD206 M2 phenotype. Chem. Biol. Interact. 274, 89–99. 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson J., McAlpine J. B., Friesen J. B., Chen S.-N., Graham J., Pauli G. F. (2016). Can invalid bioactives undermine natural product-based drug discovery? J. Med. Chem. 59 (5), 1671–1690. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobowska A., Granica S., Filipek A., Melzig M. F., Moeslinger T., Zentek J., et al. (2021). Comparative studies of urolithins and their Phase II metabolites on macrophage and neutrophil functions. Eur. J. Nutr. 60 (4), 1957–1972. 10.1007/s00394-020-02386-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boras B., Jones R. M., Anson B. J., Arenson D., Aschenbrenner L., Bakowski M. A., et al. (2021). Discovery of a novel inhibitor of coronavirus 3CL protease for the potential treatment of COVID-19. bioRxiv. 6055, 293498. 10.1101/2020.09.12.293498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann M., Alt M., Schipper L., van de Sand L., Le-Trilling V. T. K., Rink L., et al. (2021). Turmeric root and its bioactive ingredient curcumin effectively neutralize SARS-CoV-2 in vitro . Viruses 13 (10), 1914. 10.3390/v13101914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutin J. A., Meunier F., Lambert P. H., Hennig P., Bertin D., Serkiz B., et al. (1993). In vivo and in vitro glucuronidation of the flavonoid diosmetin in rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 21 (6), 1157–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanero M. A., Escolar M., Perez G., Garcia-Quetglas E., Sadaba B., Azanza J. R. (2010). Simultaneous determination of diosmin and diosmetin in human plasma by ion trap liquid chromatography–atmospheric pressure chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry: Application to a clinical pharmacokinetic study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 51 (4), 875–881. 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuzzi S. J., Muratov E. N., Tropsha A. (2017). Phantom PAINS: Problems with the utility of alerts for pan-assay INterference CompoundS. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 57 (3), 417–427. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.-Y., Shien J.-H., Tiley L., Chiou S.-S., Wang S.-Y., Chang T.-J., et al. (2010). Curcumin inhibits influenza virus infection and haemagglutination activity. Food Chem. x. 119 (4), 1346–1351. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi N., Scagnolari C., D’Amore A., Palombi F., Criscuolo E., Frasca F., et al. (2021). Naringenin is a powerful inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro . Pharmacol. Res. 163, 105255. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashnyam P., Mudududdla R., Hsieh T.-J., Lin T.-C., Lin H.-Y., Chen P.-Y., et al. (2018). β-Glucuronidases of opportunistic bacteria are the major contributors to xenobiotic-induced toxicity in the gut. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 16372. 10.1038/s41598-018-34678-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer V. C. J., Dihal A. A., van der Woude H., Arts I. C. W., Wolffram S., Alink G. M., et al. (2005). Tissue distribution of quercetin in rats and pigs. J. Nutr. 135 (7), 1718–1725. 10.1093/jn/135.7.1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries P., Dien T. (2021). Clinical pharmacology and therapeutic potential of artemisinin and its derivatives in the treatment of malaria. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8957153/(Accessed 12 07, 2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ding Y., Dou J., Teng Z., Yu J., Wang T., Lu N., et al. (2014). Antiviral activity of baicalin against influenza A (H1N1/H3N2) virus in cell culture and in mice and its inhibition of neuraminidase. Arch. Virol. 159 (12), 3269–3278. 10.1007/s00705-014-2192-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Wei X., Zhang F., Hao J., Huang F., Zhang C., et al. (2014). A dual character of flavonoids in influenza A virus replication and spread through modulating cell-autonomous immunity by mapk signaling pathways. Sci. Rep. 4 (1), 7237. 10.1038/srep07237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer O. (2021). Covid-19: FDA expert panel recommends authorising molnupiravir but also voices concerns. BMJ 375, n2984. 10.1136/bmj.n2984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Qian S., Qian P., Li X. (2016). Antiviral activity of luteolin against Japanese encephalitis virus. Virus Res. 220, 112–116. 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French C. J., Towers G. H. N. (1992). Inhibition of infectivity of potato virus X by flavonoids. Phytochemistry 31 (9), 3017–3020. 10.1016/0031-9422(92)83438-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo P., Rodriguez-Gómez I., González-Manzano S., Dueñas M., Jiménez R., Menéndez C., et al. (2012). Glucuronidated quercetin lowers blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats via deconjugation. PLoS ONE 7 (3), e32673. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh A., Aman A., Logie J., Barthel B., Cogan P., Al-awar R., et al. (2019). Colloidal drug aggregate stability in high serum conditions and pharmacokinetic consequence. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 751–757. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh A., Donders E., Shoichet B., Shoichet M. (2018). Colloidal aggregation: From screening nuisance to formulation nuance. Nano Today 19, 188–200. 10.1016/j.nantod.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh A., McLaughlin C., Duan D., Shoichet B., Shoichet M. (2017). A new spin on antibody-drug conjugates: Trastuzumab-fulvestrant colloidal drug aggregates target HER2-positive cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 12195–12202. 10.1021/acsami.6b15987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilberg E., Jasial S., Stumpfe D., Dimova D., Bajorath J. (2016). Highly promiscuous small molecules from biological screening assays include many pan-assay interference compounds but also candidates for polypharmacology. J. Med. Chem. 59 (22), 10285–10290. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilberg E., Gütschow M., Bajorath J. (2019). Promiscuous ligands from experimentally determined structures, binding conformations, and protein family-dependent interaction hotspots. ACS Omega 4 (1), 1729–1737. 10.1021/acsomega.8b03481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilberg E., Stumpfe D., Bajorath J. (2018). X-Ray-Structure-Based identification of compounds with activity against targets from different families and generation of templates for multitarget ligand design. ACS Omega 3 (1), 106–111. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gökçe Ş., Dörtkardeşler B. E., Yurtseven A., Kurugöl Z. (2021). Effectiveness of Pelargonium sidoides in pediatric patients diagnosed with uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection: A single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 180 (9), 3019–3028. 10.1007/s00431-021-04211-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- V. Gold. (Editor) (2019). The IUPAC compendium of chemical terminology: The gold book. 4th ed. (Research Triangle Park, NC: International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry; ). 10.1351/goldbook [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griesbach R. (2010). Biochemistry and genetics of flower color. New Jersey, United States: Wiley Online Library. 10.1002/9780470650301.CH4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutha L. R., Casassa L. F., Harbertson J. F., Naidu R. A. (2010). Modulation of flavonoid biosynthetic pathway genes and anthocyanins due to virus infection in grapevine (vitis ViniferaL.) leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 10 (1), 187. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai Y., Zhang Y., Liang Y., Ma X., Qi X., Xiao J., et al. (2020). Advance on the absorption, metabolism, and efficacy exertion of quercetin and its important derivatives. Food Front. 1 (4), 420–434. 10.1002/fft2.50 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haid S., Novodomská A., Gentzsch J., Grethe C., Geuenich S., Bankwitz D., et al. (2012). A plant-derived flavonoid inhibits entry of all HCV genotypes into human hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 143 (1), 213–222. e5. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L., Fu Q., Deng C., Luo L., Xiang T., Zhao H. (2022). Immunomodulatory potential of flavonoids for the treatment of autoimmune diseases and tumour. Scand. J. Immunol. 95 (1), e13106. 10.1111/sji.13106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HealthTech F., de Zeneta C. (2018). Notice to US Food and Drug Administration of the Conclusion that the Intended Use of Orange Extract is Generally Recognized as Safe. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration, 2–77. [Google Scholar]

- Helfer M., Koppensteiner H., Schneider M., Rebensburg S., Forcisi S., Müller C., et al. (2014). The root extract of the medicinal plant Pelargonium sidoides is a potent HIV-1 attachment inhibitor. PLOS ONE 9 (1), e87487. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo M. N., Emura N., Kawagoe T., Sugisaka J., Kamitani M., Nagano A. J., et al. (2020). Seasonality of interactions between a plant virus and its host during persistent infection in a natural environment. ISME J. 14 (2), 506–518. 10.1038/s41396-019-0519-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Zhang W., Ke Z., Li Y., Zhou Z. (2017). In vitro release and antioxidant activity of Satsuma mandarin (citrusreticulatablancocv. unshiu) peel flavonoids encapsulated by pectin nanoparticles. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 2362–2373. 10.1111/ijfs.13520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R.-Y., Yu Y.-L., Cheng W.-C., OuYang C.-N., Fu E., Chu C.-L. (2010). Immunosuppressive effect of quercetin on dendritic cell activation and function. J. Immunol. 184 (12), 6815–6821. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T., Yoshinaga A., Takabe K., Yoshioka T., Ogawa K., Sakamoto M., et al. (2015). In situ detection and identification of hesperidin crystals in satsuma Mandarin (citrus unshiu) peel cells. Phytochem. Anal. 26, 105–110. 10.1002/pca.2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishisaka A., Kawabata K., Miki S., Shiba Y., Minekawa S., Nishikawa T., et al. (2013). Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to deconjugation of quercetin glucuronides in inflammatory macrophages. PLoS ONE 8 (11), e80843. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannat K., Paul A. K., Bondhon T. A., Hasan A., Nawaz M., Jahan R., et al. (2021). Nanotechnology applications of flavonoids for viral diseases. Pharmaceutics 13 (11), 1895. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13111895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasial S., Hu Y., Bajorath J. (2016). Determining the degree of promiscuity of extensively assayed compounds. PLOS ONE 11 (4), e0153873. 10.1371/journal.pone.0153873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasial S., Hu Y., Bajorath J. (2017). How frequently are pan-assay interference compounds active? Large-scale Analysis of screening data reveals diverse activity profiles, low global hit frequency, and many consistently inactive compounds. J. Med. Chem. 60 (9), 3879–3886. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasial S., Hu Y., Bajorath J. (2016). PubChem compounds tested in primary and confirmatory assays. Geneva, Switzerland: Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.44593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M. J., Kim U., Kim I. S., Kim Y., Kim D.-H., Han S. B., et al. (2010). Effects of gut microflora on pharmacokinetics of hesperidin: A study on non-antibiotic and pseudo-germ-free rats. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. A 73 (21–22), 1441–1450. 10.1080/15287394.2010.511549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S., Kim S., Shin D. H., Kim M.-S. (2020). Inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CL protease by flavonoids. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 35 (1), 145–151. 10.1080/14756366.2019.1690480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johari J., Kianmehr A., Mustafa M. R., Abubakar S., Zandi K. (2012). Antiviral activity of baicalein and quercetin against the Japanese encephalitis virus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13 (12), 16785–16795. 10.3390/ijms131216785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamin W., Ilyenko L. I., Malek F. A., Kieser M. (2012). Treatment of acute bronchitis with EPs 7630: Randomized, controlled trial in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Int. 54 (2), 219–226. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamin W., Maydannik V., Malek F. A., Kieser M. (2010). Efficacy and tolerability of EPs 7630 in children and adolescents with acute bronchitis - a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial with a herbal drug preparation from Pelargonium sidoides roots. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 48 (3), 184–191. 10.5414/cpp48184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeil A., Mostafa A., Kutkat O., Moatasim Y., Al-Karmalawy A. A., Rashad A. A., et al. (2021). Bioactive polyphenolic compounds showing strong antiviral activities against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Pathogens 10 (6), 758. 10.3390/pathogens10060758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko A., Matsumoto T., Matsubara Y., Sekiguchi K., Koseki J., Yakabe R., et al. (2017). Glucuronides of phytoestrogen flavonoid enhance macrophage function via conversion to aglycones by β-glucuronidase in macrophages: Flavonoid glucuronides activate macrophage. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 5 (3), 265–279. 10.1002/iid3.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L., Miao M.-S., Song Y.-G., Fang X.-Y., Zhang J., Zhang Y.-N., et al. (2021). Total flavonoids of Taraxacum mongolicum inhibit non-small cell lung cancer by regulating immune function. J. Ethnopharmacol. 281, 114514. 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik D., O’Fallon K., Clarkson P. M., Patrick Dunne C., Conca K. R., Michniak-Kohn B. (2012). Comparison of quercetin pharmacokinetics following oral supplementation in humans. J. Food Sci. 77 (11), H231–H238. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata K., Mukai R., Ishisaka A. (2015). Quercetin and related polyphenols: New insights and implications for their bioactivity and bioavailability. Food Funct. 6 (5), 1399–1417. 10.1039/C4FO01178C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y. (2014). β-Glucuronidase activity and mitochondrial dysfunction: The sites where flavonoid glucuronides act as anti-inflammatory agents. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 54 (3), 145–150. 10.3164/jcbn.14-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y., Nishikawa T., Shiba Y., Saito S., Murota K., Shibata N., et al. (2008). Macrophage as a target of quercetin glucuronides in human atherosclerotic arteries: Implication in the anti-atherosclerotic mechanism of dietary flavonoids. J. Biol. Chem. 283 (14), 9424–9434. 10.1074/jbc.M706571200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y. (2018). Understanding metabolic conversions and molecular actions of flavonoids in vivo:toward new strategies for effective utilization of natural polyphenols in human Health. J. Med. Invest. 65 (34), 162–165. 10.2152/jmi.65.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Choi H., Kim S., Kang L. W., Kim Y. B. (2021). Elucidating the effects of curcumin against influenza using in silico and in vitro approaches. Pharmaceuticals 14 (9), 880. 10.3390/ph14090880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissler S. M., Fauver J. R., Mack C., Tai C. G., Breban M. I., Watkins A. E., et al. (2021). Viral dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 variants in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: medRxiv, 21251535. 10.1101/2021.02.16.21251535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnle G., Spencer J. P. E., Chowrimootoo G., Schroeter H., Debnam E. S., Srai S. K. S., et al. (2000). Resveratrol is absorbed in the small intestine as resveratrol glucuronide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 272 (1), 212–217. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Pandey A. K. (2013). Chemistry and biological activities of flavonoids: An overview. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013, 162750. 10.1155/2013/162750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalani S., Poh C. L. (2020). Flavonoids as antiviral agents for enterovirus A71 (EV-A71). Viruses 12 (2), 184. 10.3390/v12020184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lani R., Hassandarvish P., Shu M.-H., Phoon W. H., Chu J. J. H., Higgs S., et al. (2016). Antiviral activity of selected flavonoids against chikungunya virus. Antivir. Res. 133, 50–61. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo L., Erman M. (2022). FDA declines to authorize common antidepressant as COVID treatment. Reuters. 16, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Likic S., Šola I., Ludwig-Müller J., Rusak G. (2014). Involvement of kaempferol in the defence response of virus infected arabidopsis thaliana. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 138, 257–271. 10.1007/s10658-013-0326-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-W., Tsai F.-J., Tsai C.-H., Lai C.-C., Wan L., Ho T.-Y., et al. (2005). Anti-SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease effects of isatis indigotica root and plant-derived phenolic compounds. Antivir. Res. 68 (1), 36–42. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M., Krammer F., Regev-Yochay G., Lustig Y., Balicer R. D. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals: Measurement, causes and impact. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 57–65. 10.1038/s41577-021-00662-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liskova A., Samec M., Koklesova L., Samuel S. M., Zhai K., Al-Ishaq R. K., et al. (2021). Flavonoids against the SARS-CoV-2 induced inflammatory storm. Biomed. Pharmacother. 138, 111430. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D.-D., Cao G., Han L.-K., Ye Y.-L., Zhang Q., Sima Y.-H., et al. (2016). Flavonoids from radix tetrastigmae improve LPS-induced acute lung injury via the TLR4/MD-2-mediated pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 14 (2), 1733–1741. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Ye F., Sun Q., Liang H., Li C., Li S., et al. (2021). Scutellaria baicalensis extract and baicalein inhibit replication of SARS-CoV-2 and its 3C-like protease in vitro . J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 36 (1), 497–503. 10.1080/14756366.2021.1873977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D. (2018). “Looking way down into the cells,” in The pipeline. Washington D.C: the Pipeline. Available at: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/looking-way-down-into-cells (Accessed December 13, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D., (2019). “Drugs inside cells: How hard can it Be, right?,” in The pipeline (Washington D.C: the Pipeline; ). Available at: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/drugs-inside-cells-hard-can-right (Accessed December 13, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D. (2020). “More on screening For coronavirus therapies,” in Science mgazine’s in the pipeline (Washington DC: ). Available at: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/more-screening-coronavirus-therapies(Accessed December 5, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D. (2021). “Too many papers,” in Science magazine’s in the Pipeline (Washington D.C: ). Available at: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/too-many-papers (Accessed December 5, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Lowe W. (2012). “Screen shots,” in Chemistry world. Available at: https://www.chemistryworld.com/opinion/screen-shots/5266.article (Accessed December, 9 2021).

- Malhotra B., Onyilagha J. C., Bohm B. A., Towers G. H. N., James D., Harborne J. B., et al. (1996). Inhibition of tomato ringspot virus by flavonoids. Phytochemistry 43 (6), 1271–1276. 10.1016/S0031-9422(95)00522-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malone B., Campbell E. A. (2021). Molnupiravir: Coding for catastrophe. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 28 (9), 706–708. 10.1038/s41594-021-00657-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manach C., Morand C., Gil-Izquierdo A., Bouteloup-Demange C., Rémésy C. (2003). Bioavailability in humans of the flavanones hesperidin and narirutin after the ingestion of two doses of orange juice. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 57 (2), 235–242. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal P., Dan S., Chakraborty S., Ghosh B., Saha C., Khanam J., et al. (2019). Simultaneous determination and quantitation of diosmetin and hesperetin in human plasma by liquid chromatographic mass spectrometry with an application to pharmacokinetic studies. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 57 (5), 451–461. 10.1093/chromsci/bmz015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Palma D., Tabares-Guevara J. H., Zapata-Cardona M. I., Flórez-Álvarez L., Yepes L. M., Rugeles M. T., et al. (2021). Curcumin inhibits in vitro SARS-CoV-2 infection in Vero E6 cells through multiple antiviral mechanisms. Molecules 26 (22), 6900. 10.3390/molecules26226900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall T., Shult P., Busse W. W. (1988). Release of lysosomal enzyme beta-glucuronidase from isolated human eosinophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 82 (4), 550–555. 10.1016/0091-6749(88)90964-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins M. T., Rivera I. G., Clark D. L., Stewart M. H., Wolfe R. L., Olson B. H. (1993). Distribution of UidA gene sequences in Escherichia coli isolates in water sources and comparison with the expression of beta-glucuronidase activity in 4-methylumbelliferyl-beta-D-glucuronide media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59 (7), 2271–2276. 10.1128/AEM.59.7.2271-2276.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyeni S., Iqhrammullah M., Frediansyah A., Nainu F., Tallei T., Emran T. B., et al. (2022). Molnupiravir: A lethal mutagenic drug against rapidly mutating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-A narrative review. J. Med. Virol. 94 (7), 3006–3016. 10.1002/jmv.27730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathesius U. (2018). Flavonoid functions in plants and their interactions with other organisms. Plants 7 (2), E30. 10.3390/plants7020030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern S. L., Caselli E., Grigorieff N., Shoichet B. K. (2002). A common mechanism underlying promiscuous inhibitors from virtual and high-throughput screening. J. Med. Chem. 45 (8), 1712–1722. 10.1021/jm010533y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern S. L., Shoichet B. K. (2003). Kinase inhibitors: Not just for kinases anymore. J. Med. Chem. 46 (8), 1478–1483. 10.1021/jm020427b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez C., Dueñas M., Galindo P., González-Manzano S., Jimenez R., Moreno L., et al. (2011). Vascular deconjugation of quercetin glucuronide: The flavonoid paradox revealed? Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 55 (12), 1780–1790. 10.1002/mnfr.201100378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer O. C. (1994). Safety and security of Daflon 500 Mg in venous insufficiency and in hemorrhoidal disease. Angiology 45 (6), 579–584. 10.1177/000331979404500614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton E. (1998). Effect of plant flavonoids on immune and inflammatory cell function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 439, 175–182. 10.1007/978-1-4615-5335-9_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierziak J., Kostyn K., Kulma A. (2014). Flavonoids as important molecules of plant interactions with the environment. Molecules 19 (10), 16240–16265. 10.3390/molecules191016240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounce B. C., Cesaro T., Carrau L., Vallet T., Vignuzzi M. (2017). Curcumin inhibits zika and chikungunya virus infection by inhibiting cell binding. Antivir. Res. 142, 148–157. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair M. P. N., Kandaswami C., Mahajan S., Chadha K. C., Chawda R., Nair H., et al. (2002). The flavonoid, quercetin, differentially regulates Th-1 (IFNgamma) and Th-2 (IL4) cytokine gene expression by normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1593 (1), 29–36. 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00328-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natural phytochemicals (2002). luteolin and isoginkgetin, inhibit 3C protease and infection of FMDV, in silico and in vitro . Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34834926/ (Accessed 2021-12-10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Naz H., Islam A., Waheed A., Sly W. S., Ahmad F., Hassan I. (2013). Human β-glucuronidase: Structure, function, and application in enzyme replacement therapy. Rejuvenation Res. 16 (5), 352–363. 10.1089/rej.2013.1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. T. H., Woo H.-J., Kang H.-K., Nguyen V. D., Kim Y.-M., Kim D.-W., et al. (2012). Flavonoid-mediated inhibition of SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease expressed in pichia pastoris. Biotechnol. Lett. 34 (5), 831–838. 10.1007/s10529-011-0845-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwa W., Kumar R., Thompson D., Lyerly W., Moore R., Reid T.-E., et al. (2020). Potential of flavonoid-inspired phytomedicines against COVID-19. Molecules 25 (11), 2707. 10.3390/molecules25112707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov A. (2017). FDA GRAS 719-pepsico-orange pomace-safety evaluation dossier supporting A generally recognized as safe (GRAS) conclusion for orange pomace. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration, 1-135. [Google Scholar]

- Ninfali P., Antonelli A., Magnani M., Scarpa E. S. (2020). Antiviral properties of flavonoids and delivery strategies. Nutrients 12 (9), 2534. 10.3390/nu12092534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell H. R., Tummino T. A., Bardine C., Craik C. S., Shoichet B. K. (2021). Colloidal aggregators in biochemical SARS-CoV-2 repurposing screens. J. Med. Chem. 64, 17530–17539. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary K. A., Day A. J., Needs P. W., Sly W. S., O’Brien N. M., Williamson G. (2001). Flavonoid glucuronides are substrates for human liver β-glucuronidase. FEBS Lett. 503 (1), 103–106. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02684-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oo A. M., Mohd Adnan L. H., Nor N. M., Simbak N., Ahmad N. Z., Lwin O. M. (2021). Immunomodulatory effects of flavonoids: An experimental study on natural-killer-cell-mediated cytotoxicity against lung cancer and cytotoxic granule secretion profile. Proc. Singap. Healthc. 30 (4), 279–285. 10.1177/2010105820979006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owen S. C., Doak A. K., Wassam P., Shoichet M. S., Shoichet B. K. (2012). Colloidal aggregation affects the efficacy of anticancer drugs in cell culture. ACS Chem. Biol. 7 (8), 1429–1435. 10.1021/cb300189b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panche A. N., Diwan A. D., Chandra S. R. (2016). Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 5, e47. 10.1017/jns.2016.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.-Y., Kim J. H., Kwon J. M., Kwon H.-J., Jeong H. J., Kim Y. M., et al. (2013). Dieckol, a SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitor, isolated from the edible Brown algae ecklonia cava. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21 (13), 3730–3737. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel K., Gadewar M., Tahilyani V., Patel D. K. (2013). A review on pharmacological and analytical aspects of diosmetin: A concise report. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 19 (10), 792–800. 10.1007/s11655-013-1595-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patiroglu T., Tunc A., Eke Gungor H., Unal E. (2012). The efficacy of Pelargonium sidoides in the treatment of upper respiratory tract infections in children with transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy. Phytomedicine 19 (11), 958–961. 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Vizcaino F., Duarte J., Santos-Buelga C. (2012). The flavonoid paradox: Conjugation and deconjugation as key steps for the biological activity of flavonoids. J. Sci. Food Agric. 92 (9), 1822–1825. 10.1002/jsfa.5697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer (2021). Pfizer’s novel COVID-19 oral antiviral treatment candidate reduced risk of hospitalization or death by 89% in interim analysis of Phase 2/3 EPIC-HR study. Available at: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizers-novel-covid-19-oral-antiviral-treatment-candidate (Accessed 12 05, 2021).

- Pietta P. G. (2000). Flavonoids as antioxidants. J. Nat. Prod. 63 (7), 1035–1042. 10.1021/np9904509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwowarski J. P., Stanisławska I., Granica S., Stefańska J., Kiss A. K. (2017). Phase II conjugates of urolithins isolated from human urine and potential role of β -glucuronidases in their disposition. Drug Metab. Dispos. 45 (6), 657–665. 10.1124/dmd.117.075200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjala L., Tammela P. (2012). Aggregating behavior of phenolic compounds — a source of false bioassay results? Molecules 17 (9), 10774–10790. 10.3390/molecules170910774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quideau S., Deffieux D., Douat-Casassus C., Pouységu L. (2011). Plant polyphenols: Chemical properties, biological activities, and synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50 (3), 586–621. 10.1002/anie.201000044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratain M. J., Plunkett William K. (2003). “J. Principles of pharmacokinetics,” in Holl.-Frei cancer med. 6th Ed. (New Jersey, United States: Wiley Online Library; ). [Google Scholar]

- Rathee P., Chaudhary H., Rathee S., Rathee D., Kumar V., Kohli K. (2009). Mechanism of action of flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents: A review. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 8 (3), 229–235. 10.2174/187152809788681029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis G., Moreira-Silva E. A., dos S., Silva D. C. M., Thabane L., Milagres A. C., et al. (2021). Effect of early treatment with fluvoxamine on risk of emergency care and hospitalisation among patients with COVID-19: The TOGETHER randomised, platform clinical trial. Lancet Glob. Health 0 (0), e42–e51. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00448-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roschek B., Fink R. C., McMichael M. D., Li D., Alberte R. S. (2009). Elderberry flavonoids bind to and prevent H1N1 infection in vitro . Phytochemistry 70 (10), 1255–1261. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roshanravan N., Seif F., Ostadrahimi A., Pouraghaei M., Ghaffari S. (2020). Targeting cytokine storm to manage patients with COVID-19: A mini-review. Arch. Med. Res. 51 (7), 608–612. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth M., Fang L., Stolz D., Tamm M. (2019). Pelargonium sidoides radix extract EPs 7630 reduces rhinovirus infection through modulation of viral binding proteins on human bronchial epithelial cells. PloS One 14 (2), e0210702. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi S., Merrill D. P., Hirsch M. S. (1994). Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in cytokine-stimulated monocytes/macrophages by combination therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 170 (6), 1361–1366. 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo R., Chandradhara D., De Tommasi N. (2018). Comparative bioavailability of two diosmin formulations after oral administration to healthy volunteers. Molecules 23 (9), E2174. 10.3390/molecules23092174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo R., Mancinelli A., Ciccone M., Terruzzi F., Pisano C., Severino L. (2015). Pharmacokinetic profile of µsmin PlusTM, a new micronized diosmin formulation, after oral administration in rats. Nat. Prod. Commun. 10 (9), 1569–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu Y. B., Jeong H. J., Kim J. H., Kim Y. M., Park J.-Y., Kim D., et al. (2010). Biflavonoids from torreya nucifera displaying SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18 (22), 7940–7947. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Sehrawat N., Sharma A., Yadav M., Verma P., Sharma A. K. (2021). Multifaceted antiviral therapeutic potential of dietary flavonoids: Emerging trends and future perspectives. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem 1–18. 10.1002/bab.2265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan R., Spelman K. (2021). Polyphenolic promiscuity, inflammation-coupled specificity: Whether PAINs filters mask an antiviral asset. Geneva, Switzerland: Zenodo. [Preprint]. 10.5281/zenodo.5791777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]