Key Points

Question

Is there an association between the timing of preoperative hemodialysis relative to surgery and postoperative mortality in patients with end-stage kidney disease who are treated with hemodialysis?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort study of 1 147 846 surgical procedures among 346 828 Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage kidney disease treated with hemodialysis, longer intervals between hemodialysis and subsequent surgical procedure were significantly associated with increased risk of postoperative 90-day mortality in a dose-dependent manner (2 days vs 1 day: adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.14; 3 days vs 1 day: adjusted HR, 1.25; and 3 days vs 2 days: adjusted HR, 1.09), although the findings were attenuated after accounting for receipt of hemodialysis on the same day as surgery.

Meaning

Among Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage kidney disease, longer intervals between hemodialysis and surgery were associated with higher risk of postoperative mortality, mainly among those who did not receive hemodialysis on the day of surgery, although the magnitude of the absolute risk differences was small and the findings are susceptible to residual confounding.

Abstract

Importance

For patients with end-stage kidney disease treated with hemodialysis, the optimal timing of hemodialysis prior to elective surgical procedures is unknown.

Objective

To assess whether a longer interval between hemodialysis and subsequent surgery is associated with higher postoperative mortality in patients with end-stage kidney disease treated with hemodialysis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study of 1 147 846 procedures among 346 828 Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage kidney disease treated with hemodialysis who underwent surgical procedures between January 1, 2011, and September 30, 2018. Follow-up ended on December 31, 2018.

Exposures

One-, two-, or three-day intervals between the most recent hemodialysis treatment and the surgical procedure. Hemodialysis on the day of the surgical procedure vs no hemodialysis on the day of the surgical procedure.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was 90-day postoperative mortality. The relationship between the dialysis-to-procedure interval and the primary outcome was modeled using a Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Of the 1 147 846 surgical procedures among 346 828 patients (median age, 65 years [IQR, 56-73 years]; 495 126 procedures [43.1%] in female patients), 750 163 (65.4%) were performed when the last hemodialysis session occurred 1 day prior to surgery, 285 939 (24.9%) when the last hemodialysis session occurred 2 days prior to surgery, and 111 744 (9.7%) when the last hemodialysis session occurred 3 days prior to surgery. Hemodialysis was also performed on the day of surgery for 193 277 procedures (16.8%). Ninety-day postoperative mortality occurred after 34 944 procedures (3.0%). Longer intervals between the last hemodialysis session and surgery were significantly associated with higher risk of 90-day mortality in a dose-dependent manner (2 days vs 1 day: absolute risk, 4.7% vs 4.2%, absolute risk difference, 0.6% [95% CI, 0.4% to 0.8%], adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.14 [95% CI, 1.10 to 1.18]; 3 days vs 1 day: absolute risk, 5.2% vs 4.2%, absolute risk difference, 1.0% [95% CI, 0.8% to 1.2%], adjusted HR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.19 to 1.31]; and 3 days vs 2 days: absolute risk, 5.2% vs 4.7%, absolute risk difference, 0.4% [95% CI, 0.2% to 0.6%], adjusted HR, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.04 to 1.13]). Undergoing hemodialysis on the same day as surgery was associated with a significantly lower hazard of mortality vs no same-day hemodialysis (absolute risk, 4.0% for same-day hemodialysis vs 4.5% for no same-day hemodialysis; absolute risk difference, −0.5% [95% CI, −0.7% to −0.3%]; adjusted HR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.84-0.91]). In the analyses that evaluated the interaction between the hemodialysis-to-procedure interval and same-day hemodialysis, undergoing hemodialysis on the day of the procedure significantly attenuated the risk associated with a longer hemodialysis-to-procedure interval (P<.001 for interaction).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage kidney disease, longer intervals between hemodialysis and surgery were significantly associated with higher risk of postoperative mortality, mainly among those who did not receive hemodialysis on the day of surgery. However, the magnitude of the absolute risk differences was small, and the findings are susceptible to residual confounding.

This retrospective cohort study assesses whether a longer interval between hemodialysis and subsequent surgery is associated with higher postoperative mortality in patients with end-stage kidney disease treated with hemodialysis.

Introduction

For patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) treated with hemodialysis, the optimal timing of hemodialysis treatment prior to elective surgical procedures is unknown. Compared with individuals without ESKD, patients with ESKD have increased risk of mortality and postoperative myocardial infarction, stroke, sepsis, and surgical site infections after elective surgical procedures,1,2,3 and the timing of hemodialysis prior to these procedures may be an important determinant of perioperative risk.

Although experts recommend performing hemodialysis either on the day prior to surgery or on the day of surgery,4,5,6,7,8,9 there are no consensus statements or guidelines to address the timing of preoperative hemodialysis. Factors that may influence the timing of preoperative hemodialysis include a patient’s extracellular volume status, electrolyte disturbances, and heparin use during hemodialysis. One retrospective study of 190 patients reported that preoperative potassium levels were lower when hemodialysis was performed within 24 hours before surgery.10 Another study of 238 patients reported that the incidence of postoperative hypotension was increased when patients underwent hemodialysis within 7 hours prior to general anesthesia.11 No studies have evaluated the association of preoperative hemodialysis timing with longer-term postoperative outcomes.

The timing of hemodialysis before surgery is a potentially modifiable target for improving perioperative care. This study investigated the association between preoperative hemodialysis timing and postoperative outcomes.

Methods

The institutional review boards at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Stanford University approved the study and waived participant consent.

Data Source

The United States Renal Data System is a national registry of all patients treated with hemodialysis for ESKD in the US irrespective of insurance.12 The United States Renal Data System is linked to claims for patients insured through Medicare parts A and B fee-for-service plans.

Study Population

We identified patients aged 18 years or older treated with hemodialysis for ESKD and undergoing surgical procedures between January 1, 2011, and September 30, 2018. Follow-up ended on December 31, 2018. To minimize missing data, we only included patients with Medicare fee-for-service as the primary payer for 180 days prior to and 90 days after the surgical procedure. To ensure a stable hemodialysis schedule, we excluded surgical procedures occurring within 180 days of the first ever hemodialysis session. Surgical procedures performed after a kidney transplant were excluded. Patients could contribute multiple surgical procedures to the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Surgical Procedures Reported by the United States Renal Data System by Exclusion or Inclusion in the Analyses.

aMay have met more than 1 exclusion criterion. The individual exclusions under this category do not sum.

Based on guidance from the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, we identified outpatient hemodialysis claims and extracted treatment dates, vascular access modality, and hemodialysis facility zip codes.13 We only included patients with a stable Monday, Wednesday, and Friday hemodialysis schedule or a stable Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday hemodialysis schedule, which we defined as a consistent schedule for at least 3 of the 5 calendar weeks preceding but not including the week of surgery. To identify patients treated with hemodialysis 3 times weekly, we only included patients with a mean of 2.5 to 3.5 hemodialysis sessions per week and 2 to 4 hemodialysis sessions in each of the 4 calendar weeks prior to the procedure. We excluded surgical procedures that occurred more than 3 days after the last hemodialysis session.

We identified all surgical procedures and the dates of service from the Physician/Supplier Procedure Summary, and then restricted the analyses to procedures that met the narrow definition of a surgical procedure using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Surgery Flags Software for Services and Procedures,14 which was defined as an incision, excision, manipulation, or suturing of tissue that requires the use of an operating room, penetrates or breaks the skin, and involves regional anesthesia, general anesthesia, or sedation to control pain. To adjust for procedure complexity, we assigned relative value units for each procedure using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2015 National Physician Fee Schedule Relative Value File.15,16 We classified procedures into organ system groups using the HCUP Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures (eTable 1 in the Supplement).17 For patients with multiple procedures on a day, those that were coded as secondary procedures were excluded and the procedure with the highest relative value unit was selected.

We aimed to exclude patients who had emergent or unplanned surgical procedures. Because the Physician/Supplier Procedure Summary does not identify emergent procedures, we excluded procedures with an emergency department visit or a hospital admission within 1 week of the procedure. We also excluded procedures that occurred during the weekend. Because inpatient hemodialysis claims do not reliably specify the dates of hemodialysis and because we could not reliably determine preoperative hemodialysis timing unless the procedure occurred on the first day of a hospitalization, we excluded procedures occurring after the first day of a hospitalization. We identified inpatient hospitalizations using a previously described algorithm,18 and emergency department visits were identified using outpatient revenue center codes (0450-0459 or 0981).

Exposure

The primary exposure was the number of days between the last outpatient hemodialysis session and the surgical procedure. We defined 2 exposure variables: (1) the interval between the most recent hemodialysis session that occurred on a day prior to surgery and (2) a binary same-day hemodialysis variable for those who underwent hemodialysis treatment on the same day as the surgical procedure. This method differentiated patients who received same-day hemodialysis from those who did not and allowed us to examine whether same-day hemodialysis could modify an association between a longer interval from hemodialysis to the surgical procedure and postoperative mortality. This method is consistent with prior work suggesting that a long interval without hemodialysis was associated with increased mortality risk irrespective of whether a hemodialysis session occurred on the day when risk was being assessed.19 Because we could not identify the time of day for hemodialysis treatment or the surgical procedure, we could not definitively determine whether a same-day hemodialysis treatment occurred before or after a surgical procedure.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 90-day postoperative mortality. We chose 90 days for the following reasons. First, in the general perioperative care literature, experts have not agreed on the optimal follow-up interval for mortality, so we made a conservative choice to study the longest suggested interval of 90 days.20 Second, shorter follow-up periods can underestimate mortality risk after major procedures.21,22,23 Third, prior literature has used 90-day mortality as an outcome after minor procedures, including in a Medicare population with fewer comorbidities than individuals with ESKD.24 Fourth, complications (especially cardiovascular events) at 90 days are common after minor vascular procedures in the ESKD population,25 and these complications could affect longer-term differences in mortality.

To elucidate potential factors that may contribute to 90-day mortality, we included 90-day cardiovascular mortality, 90-day all-cause readmission, and 90-day readmission for cardiovascular events as prespecified secondary outcomes. Post hoc secondary outcomes included 90-day mortality due to stroke, sepsis, other infectious causes, or withdrawal of care and 90-day readmissions due to infectious causes. We used cause of death and readmission definitions as described by the United States Renal Data System.12 For inpatient procedures, time to readmission was measured starting from the index discharge date. We censored patients at the occurrence of a subsequent procedure and after the 90-day study window.

Covariates

We adjusted for age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, day of the week of the procedure, hemodialysis schedule, cause of ESKD, vascular access, relative value unit of the procedure, procedure facility type, median household income for patient zip code (linked to the US Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey),26 active listing for kidney transplant at the time of the procedure, prior surgical procedure within 30 days, dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid, facility profit status, Charlson comorbidities,27 and procedure organ system.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported using fixed categories according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medical Evidence Report Form. We included race and ethnicity to adjust for known health disparities by race and ethnicity.28 A directed acyclic graph of hypothesized model element relationships appears in eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

We plotted unadjusted cumulative incidence curves, stratified by hemodialysis-to-procedure interval, and compared intervals using the log-rank test. To adjust for confounders, we fit a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model for the primary outcome. We verified the proportional hazards assumption by visually inspecting survival and log minus log survival plots and by evaluating the correlation between the Schoenfeld residuals and time. We fit cause-specific hazard models for the secondary outcomes.29,30 We treated events such as death from a noncardiovascular cause or death preventing readmission as competing events. All multivariable analyses used robust variance estimation to account for patient-level clustering. Model specifications appear in the eMethods in the Supplement.

To examine whether a same-day hemodialysis session was associated with lower postoperative mortality after a 2- or 3-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure, we separated patients into 5 categories: (1) a 1-day interval (the reference category); (2) a 2-day interval without same-day hemodialysis; (3) a 2-day interval with same-day hemodialysis; (4) a 3-day interval without same-day hemodialysis; and (5) a 3-day interval with same-day hemodialysis. To assess for heterogeneity, we compared a 2-day interval without same-day hemodialysis vs a 2-day interval with same-day hemodialysis and a 3-day interval without same-day hemodialysis vs a 3-day interval with same-day hemodialysis. We kept a 1-day interval (with and without same-day hemodialysis) as a single reference category because fewer than 0.5% of patients with a 1-day interval received same-day hemodialysis. In the sensitivity analyses, we also used a 1-day interval with and without same-day hemodialysis as the reference category.

We conducted subgroup analyses of the primary outcome by incorporating an indicator variable for the subgroup of interest and testing for an interaction with the exposure. Predefined subgroups included common surgical procedures (eTable 2 in the Supplement) and minor eye, skin, and vascular access procedure subgroups defined by common HCUP Clinical Classifications Software categories (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

The individuals with race missing were included in the Other or Multiracial category. For all remaining missing data, we imputed 5 data sets via chained equations using all covariates and the primary outcome.31 The results were combined using the standard rules of Rubin.32 We calculated absolute risk and absolute risk differences33,34 and obtained 95% CIs using 50 bootstrap iterations per imputed data set (250 total).

We conducted 11 sensitivity analyses. The first included weekend procedures and procedures with emergency department visits or hospitalizations within the week prior to surgery. The second separately analyzed procedures with and without preoperative hemodialysis schedule changes during the 7 days preceding surgery. The third tested for bias related to censoring by restricting to each patient’s first observed procedure and by not censoring for subsequent procedures. The fourth assessed uncertainty in same-day hemodialysis by (1) restricting the analysis to outpatient procedures without same-day hemodialysis, (2) stratifying patients with a 1-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure by same-day hemodialysis, and (3) restricting the analysis to the inpatient subgroup because any outpatient same-day hemodialysis must have occurred before the hospital admission. The fifth controlled for unobserved proceduralist differences by restricting the analyses to proceduralists who performed at least 150 procedures and including a proceduralist-level random effect. The sixth used individual HCUP Clinical Classifications Software procedure categories instead of broader categories for procedural risk adjustment. The seventh evaluated different follow-up periods for mortality. The eighth tested different specifications for procedure day of the week and hemodialysis schedule. The ninth fit an overlap-weighted35 Cox proportional hazards model for the primary outcome and tested multiple models for estimating propensity scores (eMethods in the Supplement). The tenth fit Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard models for the secondary outcomes.29 The eleventh evaluated whether the association between the hemodialysis-to-procedure interval and the secondary outcomes varied by occurrence of same-day hemodialysis.

The analyses were performed using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp), R version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), R Studio version 1.4.1717 (RStudio), and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings from the analyses of the secondary outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory.

Results

We included 1 147 846 surgical procedures among 346 828 patients (Figure 1 and the Table). Of these, 65.4% of procedures had a 1-day interval between hemodialysis and surgery, 24.9% had a 2-day interval, and 9.7% had a 3-day interval (Table and eTable 4 in the Supplement). The median age at the time of the procedure was 65 years (IQR, 56-73 years) and 495 126 procedures (43.1%) involved female patients.

Table. Selected Patient, Procedure, and Facility Characteristics by Interval Between Last Hemodialysis Treatment and Surgical Procedure.

| Interval between last hemodialysis treatment and surgical procedurea | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 d (n = 750 163) | 2 d (n = 285 939) | 3 d (n = 111 744) | |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 65.0 (56.0-73.0) | 64.0 (55.0-73.0) | 64.0 (55.0-72.0) |

| Age group, y | |||

| 18-39 | 29 447 (3.9) | 11 569 (4.0) | 4612 (4.1) |

| 40-59 | 231 519 (30.9) | 91 338 (31.9) | 36 509 (32.7) |

| 60-79 | 397 161 (52.9) | 150 207 (52.5) | 58 392 (52.3) |

| ≥80 | 92 036 (12.3) | 32 825 (11.5) | 12 231 (10.9) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 425 148 (56.7) | 164 214 (57.4) | 63 358 (56.7) |

| Female | 325 015 (43.3) | 121 725 (42.6) | 48 386 (43.3) |

| Raceb | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 9755 (1.3) | 3638 (1.3) | 1449 (1.3) |

| Asian | 24 645 (3.3) | 9552 (3.3) | 3624 (3.2) |

| Black or African American | 249 055 (33.2) | 93 800 (32.8) | 38 910 (34.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 8582 (1.1) | 3005 (1.1) | 1131 (1.0) |

| Other or Multiracial | 1188 (0.2) | 377 (0.1) | 201 (0.2) |

| White | 456 938 (60.9) | 175 567 (61.4) | 66 429 (59.4) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, No./total (%)b | 137 772/750 107 (18.4) | 55 534/285 917 (19.4) | 20 939/111 725 (18.7) |

| Cause of end-stage kidney diseasec | (n = 749 145) | (n = 285 519) | (n = 111 592) |

| Diabetes | 442 893 (59.1) | 172 688 (60.5) | 67 684 (60.7) |

| Hypertension | 184 682 (24.7) | 68 155 (23.9) | 26 558 (23.8) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 46 950 (6.3) | 17 069 (6.0) | 6510 (5.8) |

| Cystic kidney | 11 999 (1.6) | 4283 (1.5) | 1709 (1.5) |

| Other urological | 8381 (1.1) | 3344 (1.2) | 1323 (1.2) |

| Other or unknownd | 54 240 (7.2) | 19 980 (7.0) | 7808 (7.0) |

| Vascular access type | (n = 750 162) | (n = 284 727) | (n = 110 159) |

| Catheter | 234 870 (31.3) | 81 847 (28.7) | 28 865 (26.2) |

| Graft | >117 000 (>15.6)e | 49 031 (17.2) | 22 985 (20.9) |

| Fistula | 397 674 (53.0) | 153 849 (54.0) | 58 309 (52.9) |

| Median household income for patient zip code, $f | (n =741 214) | (n = 282 307) | (n = 110 372) |

| 0-45 999 | 229 309 (30.9) | 86 012 (30.5) | 33 853 (30.7) |

| 46 000-58 999 | 210 928 (28.5) | 80 076 (28.4) | 31 467 (28.5) |

| 59 000-78 999 | 169 252 (22.8) | 64 721 (22.9) | 25 153 (22.8) |

| ≥79 000 | 131 725 (17.8) | 51 498 (18.2) | 19 899 (18.0) |

| Hemodialysis schedule | |||

| Mon, Wed, and Fri | 502 220 (66.9) | 142 539 (49.8) | 73 199 (65.5) |

| Tue, Thu, and Sat | 247 943 (33.1) | 143 400 (50.2) | 38 545 (34.5) |

| Underwent hemodialysis on day of surgical procedureg | 3323 (0.4) | 115 589 (40.4) | 74 365 (66.5) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR)h | 8.0 (2.0-10.0) | 8.0 (2.0-10.0) | 8.0 (2.0-10.0) |

| Procedure characteristics | |||

| Relative value units of the surgical procedure, median (IQR) | 6.6 (2.7-12.0) | 6.3 (1.8-12.0) | 6.3 (2.7-11.1) |

| Procedure day | |||

| Monday | 2616 (0.3) | 109 839 (38.4) | 65 352 (58.5) |

| Tuesday | 261 280 (34.8) | 2700 (0.9) | 33 764 (30.2) |

| Wednesday | 138 703 (18.5) | 78 594 (27.5) | 595 (0.5) |

| Thursday | 242 556 (32.3) | 36 941 (12.9) | 7602 (6.8) |

| Friday | 105 008 (14.0) | 57 865 (20.2) | 4431 (4.0) |

| Procedure organ system | |||

| Cardiovascular | 269 106 (35.9) | 90 557 (31.7) | 35 706 (32.0) |

| Eye | 273 496 (36.5) | 109 865 (38.4) | 42 106 (37.7) |

| Skin or breast | 113 734 (15.2) | 49 324 (17.2) | 21 417 (19.2) |

| Orthopedic | 31 795 (4.2) | 13 193 (4.6) | 4692 (4.2) |

| Gastrointestinal or abdominal | 31 293 (4.2) | 9278 (3.2) | 2656 (2.4) |

| Urological | 13 836 (1.8) | 8174 (2.9) | 3390 (3.0) |

| Nervous system | 5985 (0.8) | 2305 (0.8) | 745 (0.7) |

| Endocrine | 5948 (0.8) | 1547 (0.5) | 460 (0.4) |

| Ear, nose, and throat or dental | 1900 (0.3) | 628 (0.2) | 205 (0.2) |

| Obstetric or gynecologic | 1331 (0.2) | 449 (0.2) | 180 (0.2) |

| Thoracic | 1130 (0.2) | 383 (0.1) | 115 (0.1) |

| Hematologic | 609 (0.1) | 236 (0.1) | 72 (0.1) |

| Procedure facility characteristics | |||

| Procedure location | |||

| Outpatient hospital | 334 693 (44.6) | 116 004 (40.6) | 43 316 (38.8) |

| Physician’s office | 262 194 (35.0) | 102 341 (35.8) | 38 896 (34.8) |

| Ambulatory surgery center | 70 436 (9.4) | 29 015 (10.1) | 11 946 (10.7) |

| Inpatient hospital | 62 936 (8.4) | 27 487 (9.6) | 11 745 (10.5) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 4553 (0.6) | 3043 (1.1) | 1886 (1.7) |

| Home | 1930 (0.3) | 1031 (0.4) | 451 (0.4) |

| Other | 5528 (0.7) | 2109 (0.7) | 741 (0.7) |

| For-profit status, No./total (%) | 88 803/743 589 (11.9) | 34 737/283 147 (12.3) | 13 581/110 510 (12.3) |

Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was not included in the multivariable models because individual comorbidities were used. All of the other listed characteristics were used for risk adjustment in the multivariable models. Additional characteristics appear in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Derived from US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence Report Form 2728, including the category of Other or Multiracial. Although the form allows for self-identification of multiple races, the United States Renal Data System data distribution center does not distinguish between Other and Multiracial. Race was missing for less than 10 observations and these were imputed to the category of Other or Multiracial.

The categories are listed as they appear on CMS Medical Evidence Form 2728 and are subsequently reported by the United States Renal Data System. Further details, including the diagnosis codes used for categorization, are available from the United States Renal Data System.12

Unknown represents a state of uncertainty for the clinician filling out the form and differs from missing data, which were imputed as described in the Methods section.

Modified or omitted to preserve patient privacy.

Linked to the US Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey.26

There were 193 277 procedures with same-day hemodialysis sessions. The sessions may have occurred either before or after the surgical procedure.

Determined using published coding algorithms.27 Kidney disease was not included because the study cohort only consisted of patients with end-stage kidney disease. For calculation of the index, all patients were considered to have kidney disease. Possible values range from 0 to 37; higher values indicate higher 1-year mortality risk. An index value of 6 or greater has been associated with 1-year mortality of 30% to 35% in patients with end-stage kidney disease.36

The most common procedure categories were intraocular drug injections and fluid removal (19.6%), hemodialysis access procedures (19.0%), vascular procedures that did not include the head or neck (12.7%), lens and cataract procedures (10.7%), and debridement of wound, infection, or burn (8.6%) (eTable 5 in the Supplement). An additional same-day hemodialysis session occurred in 193 277 of 1 147 846 procedures (16.8%). Of the 193 277 same-day hemodialysis sessions, 3323 (1.7%) had a 1-day interval between hemodialysis and the surgery, 115 589 (59.8%) had a 2-day interval, and 74 365 (38.5%) had a 3-day interval (Table and eTable 6 in the Supplement). Of the 1 147 846 surgical procedures, less than 2% had missing data; 10 600 (0.9%) for facility profit status, 13 953 (1.2%) for median income for patient zip code, less than 10 observations for race, and less than 0.2% for the remainder of the variables.

All-Cause 90-Day Postoperative Mortality

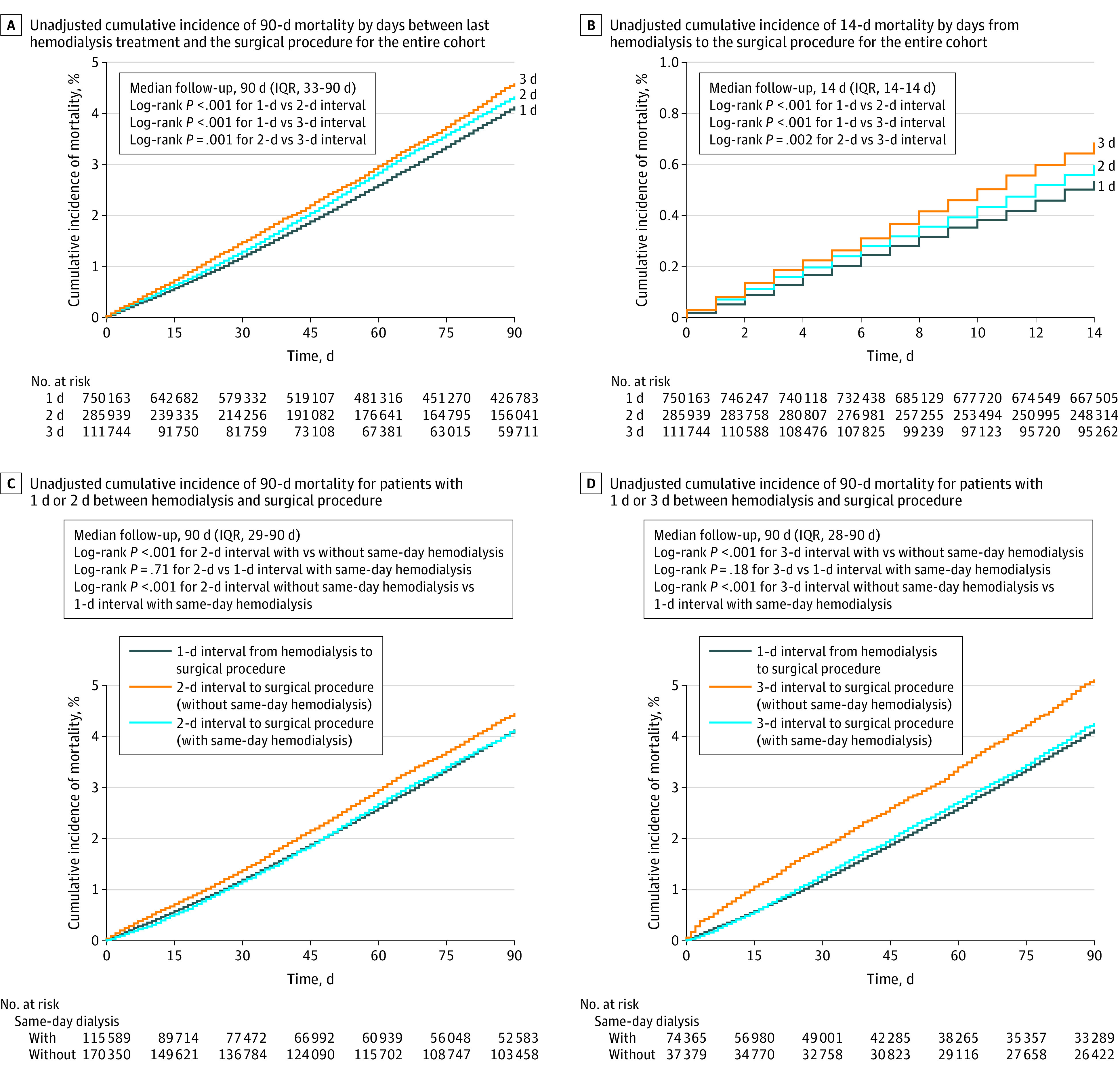

Postoperative mortality within 90 days of the procedure occurred in 34 944 patients (3.0%) and was significantly higher with longer hemodialysis-to-procedure intervals (Figure 2A). The results were consistent for perioperative mortality occurring within 14 days (Figure 2B) and within 30 days (eFigure 2 in the Supplement) after the procedure.

Figure 2. Unadjusted 90-Day and 14-Day Postoperative Mortality.

For panel B, the x-axis and y-axis scales differ from the other panels in this Figure. For panels C and D, the unadjusted cumulative incidence of mortality for patients with 1 day between last hemodialysis treatment and surgical procedure is used as the reference category. A sensitivity analysis examining 30-day mortality follow-up appears in eFigure 2 in the Supplement. The unadjusted cumulative incidence of 90-day mortality for patients with 1 day between hemodialysis treatment and surgical procedure was stratified by whether the patient received an additional hemodialysis session on the day of the surgical procedure and this analysis appears in eFigure 3 in the Supplement.

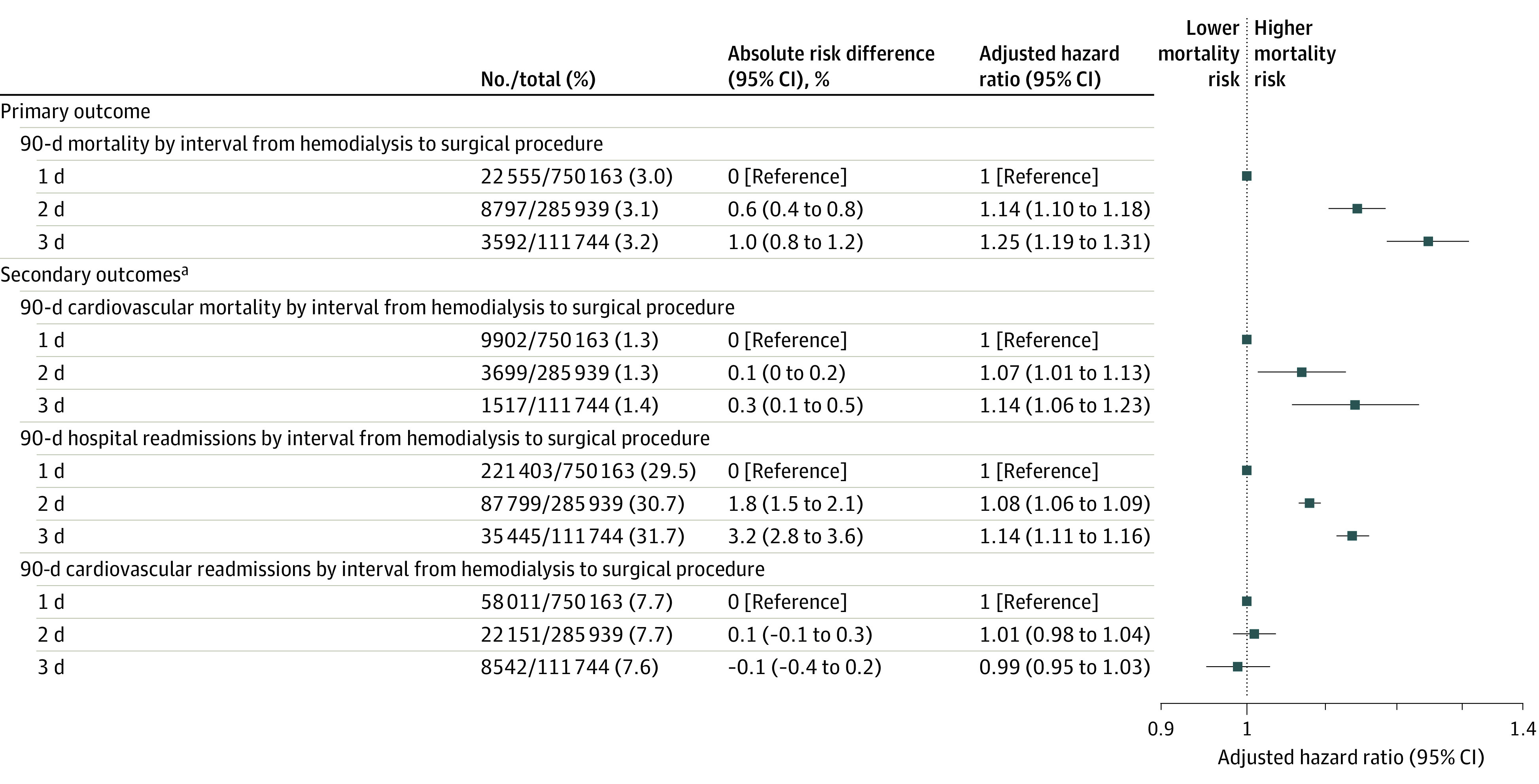

In the adjusted analysis of the full sample of surgical procedures, longer hemodialysis-to-procedure intervals were significantly associated with higher risk of 90-day mortality in a dose-dependent manner (2 days vs 1 day: absolute risk, 4.7% vs 4.2%, absolute risk difference, 0.6% [95% CI, 0.4% to 0.8%], adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.14 [95% CI, 1.10 to 1.18]; 3 days vs 1 day: absolute risk, 5.2% vs 4.2%, absolute risk difference, 1.0% [95% CI, 0.8% to 1.2%], adjusted HR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.19 to 1.31]; and 3 days vs 2 days: absolute risk, 5.2% vs 4.7%, absolute risk difference, 0.4% [95% CI, 0.2% to 0.6%], adjusted HR, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.04 to 1.13]) (Figure 3). Undergoing hemodialysis on the day of the procedure was significantly associated with lower 90-day postoperative mortality (absolute risk, 4.0% vs 4.5% without hemodialysis on the day of the procedure; absolute risk difference, −0.5% [95% CI, −0.7% to −0.3%]; adjusted HR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.84-0.91]).

Figure 3. Association Between Interval From Hemodialysis Treatment to Surgical Procedure and Perioperative Outcomes.

All models were adjusted for the covariates in the Table and in eTable 4 in the Supplement and are described in the Methods section.

aRepresent all predetermined secondary outcomes. Additional secondary outcomes and sensitivity and subgroup analyses appear in Figure 4 and in eTables 8-9 in the Supplement.

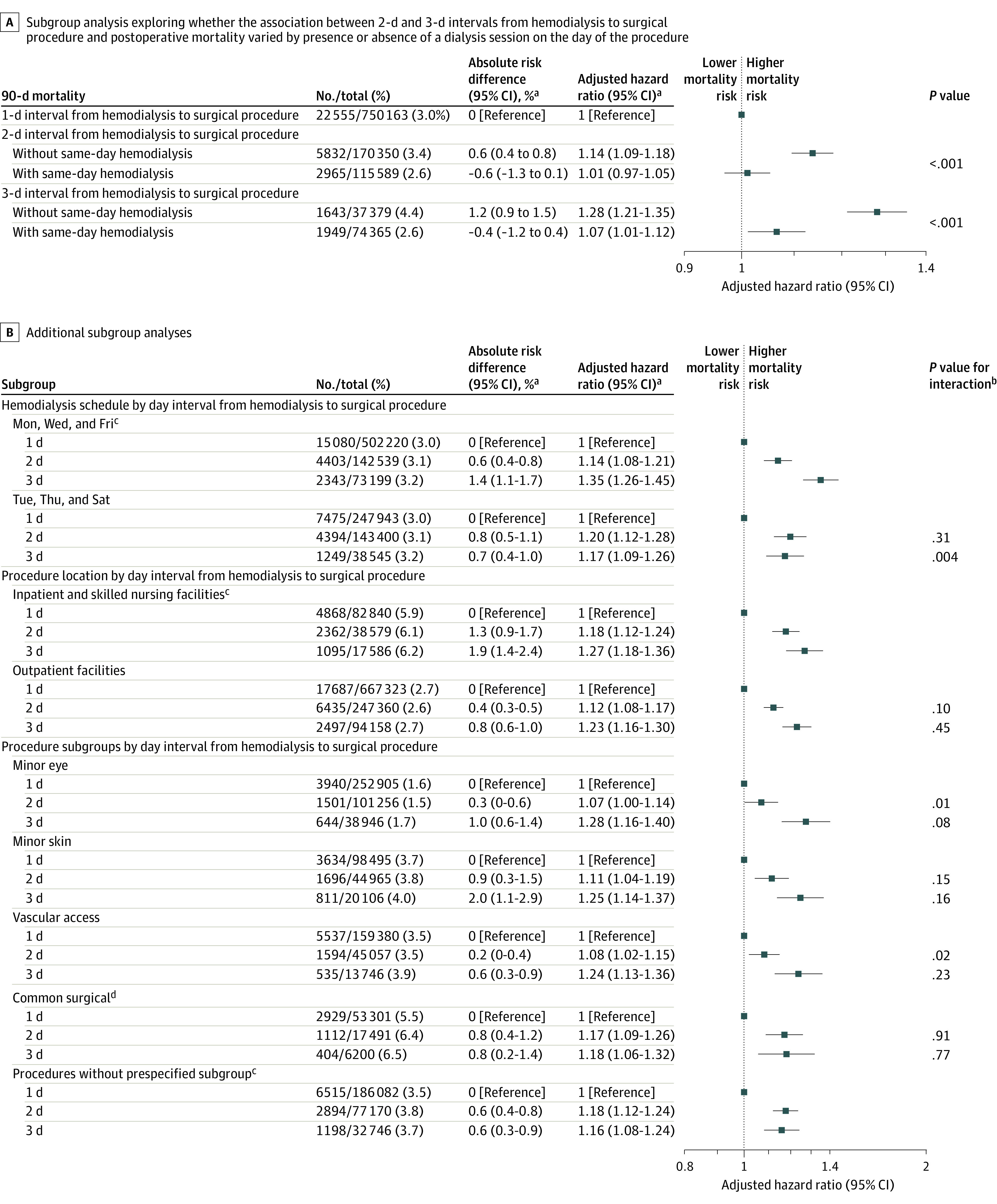

Patients with a 2- or 3-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure who also underwent same-day hemodialysis had unadjusted 90-day postoperative mortality rates that were not significantly different from patients with a 1-day interval (Figure 2C and 2D). After adjusting for confounders, a 2-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure in patients without same-day hemodialysis (absolute risk, 5.0% vs 4.4% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 0.6% [95% CI, 0.4% to 0.8%]; adjusted HR, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.09 to 1.18]) and a 3-day interval (absolute risk, 5.6% vs 4.4% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 1.2% [95% CI, 0.9% to 1.5%]; adjusted HR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.21 to 1.35]) were associated with significantly increased 90-day postoperative mortality (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Subgroup Analyses.

aThe estimates use a 1-day interval from hemodialysis treatment to the surgical procedure as a reference category because same-day hemodialysis treatment was received by fewer than 0.5% of the patients. The sensitivity analyses using alternative reference categories appear in eTable 6 in the Supplement.

bPresented for each subgroup vs the reference group.

cComparison group for the interaction tests, thus no P values for interaction are displayed for this group.

dIncludes common bariatric, cardiac, otolaryngological, general, gynecologic, orthopedic, spine, thoracic, urological, and vascular procedures. The full list of procedures appears in eTable 2 in the Supplement and an additional analysis appears in eTable 9 in the Supplement.

In contrast, a 2-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure in patients with same-day hemodialysis was not significantly associated with increased 90-day postoperative mortality (absolute risk, 3.8% vs 4.4% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, −0.6% [95% CI, −1.3% to 0.1%]; adjusted HR, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.97 to 1.05], P = .66). The 3-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure in patients with same-day hemodialysis was significantly associated with increased 90-day postoperative mortality by HR but not by absolute risk (absolute risk, 4.0% vs 4.4% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, −0.4% [95% CI, −1.2% to 0.4%]; adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.01 to 1.12], P = .02). Tests for interaction demonstrated significant heterogeneity by the presence of same-day hemodialysis (P < .001 for both a 2-day and a 3-day interval from hemodialysis to the procedure). Alternative formulations of this model are described in the eMethods and appear in eTable 7 in the Supplement.

Secondary Outcomes

The 2-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure (absolute risk, 31.4% vs 29.6% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 1.8% [95% CI, 1.5% to 2.1%]; adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.06 to 1.09]) and a 3-day interval (absolute risk, 32.8% vs 29.6% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 3.2% [95% CI, 2.8% to 3.6%]; adjusted HR, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.11 to 1.16]) were significantly associated with higher risk of 90-day hospital readmissions (Figure 3). The 2-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure (absolute risk, 1.9% vs 1.8% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 0.1% [95% CI, 0% to 0.2%]; adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.01 to 1.13]) and a 3-day interval (absolute risk, 2.0% vs 1.8% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 0.3% [95% CI, 0.1% to 0.5%]; adjusted HR, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.06 to 1.23]) were significantly associated with increased 90-day postoperative cardiovascular mortality (Figure 3). However, 2- and 3-day intervals between hemodialysis and the procedure compared with a 1-day interval were not associated with 90-day postoperative cardiovascular readmissions (Figure 3). Subdistribution hazard models were consistent with these results (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

In a post hoc analysis of the secondary outcomes, there were statistically significant associations with 90-day postoperative mortality due to withdrawal of care for a 2-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure vs a 1-day interval (HR, 1.26 [95% CI, 1.14 to 1.39], P < .001) and for a 3-day vs 1-day interval (HR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.23 to 1.64], P < .001), but not with 90-day mortality due to stroke, sepsis, or infectious causes or 90-day hospital readmissions due to infectious causes (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Procedure and Other Subgroup Analyses

For all subgroups of interest, a 2-day interval and a 3-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure compared with a 1-day interval were associated with higher 90-day postoperative mortality (Figure 4B). We observed some heterogeneity in the estimates. For instance, a 3-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure was associated with significantly higher postoperative mortality for patients who underwent hemodialysis on a Monday, Wednesday, and Friday schedule (absolute risk, 5.5% vs 4.1% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 1.4% [95% CI, 1.1% to 1.7%]; adjusted HR, 1.35 [95% CI, 1.26 to 1.45]) than for patients with a Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday schedule (absolute risk, 4.9% vs 4.2% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 0.7% [95% CI, 0.4% to 1.0%]; adjusted HR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.09 to 1.27]; P = .004 for interaction). The significantly increased postoperative mortality associated with a 2-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure was attenuated for minor eye procedures (absolute risk, 4.0% vs 3.8% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 0.3% [95% CI, 0% to 0.6%]; adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.00 to 1.14]; P = .01 for interaction) and vascular access procedures (absolute risk, 2.9% vs 2.6% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 0.2% [95% CI, 0% to 0.4%]; adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.02 to 1.15]; P = .02 for interaction) compared with procedures not in a prespecified subgroup (absolute risk, 4.3% vs 3.7% for a 1-day interval; absolute risk difference, 0.6% [95% CI, 0.4% to 0.8%]; adjusted HR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.12 to 1.24]).

Sensitivity Analyses

The results were consistent in all the sensitivity analyses, including the additional subgroup analyses, multiple approaches to procedural risk adjustment, 14- and 30-day follow-up periods, alternative model specifications, and overlap-weighted models (Figure 2B and eTable 9, eFigures 2-4, and the eMethods in the Supplement). For 90-day cardiovascular mortality and readmissions, significant heterogeneity was observed for the presence of same-day hemodialysis (eTable 10 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study of patients treated with hemodialysis for ESKD who underwent surgical procedures demonstrated a statistically significant and dose-dependent association between a longer interval from hemodialysis to surgical procedure and increased 90-day postoperative mortality. When hemodialysis was performed on the day of the surgical procedure, this association was no longer observed for a 2-day interval between hemodialysis and the procedure, and it was attenuated for a 3-day interval. Longer hemodialysis-to-procedure intervals were also significantly associated with a higher hazard of 90-day all-cause hospital readmissions and cardiovascular mortality.

These findings suggest that hemodialysis timing may be a modifiable risk factor for patients with ESKD undergoing surgery. Thirty-six percent of procedures in the study had either a 2- or 3-day hemodialysis-to-procedure interval, and 52% of the patients who underwent these procedures did not have hemodialysis on the day of the procedure. Same-day hemodialysis was associated with lower mortality, which is also consistent with the hypothesis that hemodialysis timing may influence postoperative outcomes for patients with ESKD. Because same-day hemodialysis is a modifiable clinical decision during the preoperative period, a prospective clinical trial could test the benefits of same-day hemodialysis. Implementing same-day hemodialysis might be more feasible than rearranging busy hemodialysis and surgery schedules, particularly because 2-day hemodialysis-to-procedure intervals were more common for patients with the Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday hemodialysis schedule.

Absolute risk differences were small, but were comparable with the magnitude of risk for mortality after surgery in the general population.37 Many procedures within the cohort were minor, and formal tests for interaction showed an attenuated association between a 2-day interval and postoperative mortality for minor eye and vascular access procedures. However, because minor procedures are common for patients with ESKD, even small changes in absolute risk could be meaningful, especially in a population that has disproportionately high morbidity and mortality compared with individuals without ESKD.1,2,3

This study adds to previous work suggesting that longer intervals between hemodialysis are associated with adverse outcomes, particularly cardiovascular events.19,38,39 The results presented in this article suggested that higher 90-day cardiovascular events and mortality were due to withdrawal of care but not due to stroke, sepsis, or infectious causes. Surgical procedures likely exacerbate a delicate equilibrium for patients with ESKD, making the hemodialysis-to-procedure interval an important consideration in perioperative management. This might be true even for minor procedures, given that published mortality rates in the general Medicare population are 0.5% compared with 3.0% reported for this ESKD population.24 This study showed an attenuated association between a longer hemodialysis-to-procedure interval and mortality for minor eye and vascular access procedures.

Potential etiologies of adverse outcomes associated with longer intervals between hemodialysis and surgical procedures include weight gain and extracellular volume overload, electrolyte disequilibrium and accumulation of uremic toxins, and reduced access to medical care over the weekend.40 The association of longer intervals between hemodialysis and surgery with mortality was more pronounced at shorter follow-up periods (eg, 1 day, 7 days, and 14 days), a finding consistent with the hypothesis that short-term cardiac complications may explain the findings reported in this article.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the findings may not be generalizable to patients with ESKD without Medicare fee-for-service as their primary payer or those undergoing emergency surgery.

Second, residual unmeasured confounding may persist due to the observational design. Patients with varying hemodialysis-to-procedure intervals may systematically differ from each other in unobserved ways, such as acuity of illness or care coordination.

Third, the importance of factors not available in Medicare claims, such as hemodialysis dosing or procedural urgency, could not be investigated. Fourth, these findings could not completely account for the potential effect of an unobserved inpatient hemodialysis treatment.

Fifth, a 90-day postoperative follow-up period may be less likely to reflect any adverse effects from a longer interval between hemodialysis and a surgical procedure. However, the results were consistent in the sensitivity analyses that used shorter follow-up periods.

Sixth, the secondary outcomes and subgroup analyses should be considered exploratory. Seventh, for same-day hemodialysis, available data did not include information about whether hemodialysis occurred before or after the surgical procedure. Eighth, this study could not identify characteristics of hemodialysis after surgery that may also be associated with mortality rates.

Conclusions

Among Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage kidney disease, longer intervals between hemodialysis and surgery were significantly associated with higher risk of postoperative mortality, mainly among those who did not receive hemodialysis on the day of surgery. However, the magnitude of the absolute risk differences was small, and the findings are susceptible to residual confounding.

eTable 1. Clinical Classifications Software Organ System Groups

eTable 2. Current Procedural Terminology Codes for Common Surgical Procedures Subgroup Analysis

eTable 3. Clinical Classification Software Categories for Minor Eye, Skin, and Vascular Procedures Subgroup Analysis

eTable 4. Supplemental Patient Characteristics by Days Between Last Hemodialysis and Procedure

eTable 5. Common Clinical Classification Software Procedure Categories

eTable 6. Patient and Procedure Characteristics, by Presence of an Additional Hemodialysis Session on the Day of Procedure

eTable 7. Primary Outcome Model—Alternative Reference Levels for Same-Day Hemodialysis Subgroup Analysis

eTable 8. Post Hoc Secondary Outcome and Subdistribution Hazard Models

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analyses—Association Between Days Between Last Hemodialysis and Procedure and 90-Day Postoperative Mortality

eTable 10. Secondary Outcome Models—Alternative Reference Levels for Same-Day Hemodialysis Subgroup Analysis

eMethods

eFigure 1. Directed Acyclic Graph of Hypothesized Relationships Between Key Model Variables

eFigure 2. Cumulative Incidence of 30-Day Postoperative Mortality

eFigure 3. Ninety-Day Postoperative Mortality With and Without an Additional Same-Day Dialysis Session for Patients with 1 Day Between Last Hemodialysis and Surgery

eFigure 4. Love Plots for Unadjusted and Overlap-Weighted Models

eReferences

References

- 1.Gajdos C, Hawn MT, Kile D, Robinson TN, Henderson WG. Risk of major nonemergent inpatient general surgical procedures in patients on long-term dialysis. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(2):137-143. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palamuthusingam D, Nadarajah A, Johnson DW, Pascoe EM, Hawley CM, Fahim M. Morbidity after elective surgery in patients on chronic dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02279-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palamuthusingam D, Nadarajah A, Pascoe EM, et al. Postoperative mortality in patients on chronic dialysis following elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trainor D, Borthwick E, Ferguson A. Perioperative management of the hemodialysis patient. Semin Dial. 2011;24(3):314-326. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.00856.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palevsky PM. Perioperative management of patients with chronic kidney disease or ESRD. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2004;18(1):129-144. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2003.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlo JO, Phisitkul P, Phisitkul K, Reddy S, Amendola A. Perioperative implications of end-stage renal disease in orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(2):107-118. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-13-00221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanda H, Hirasaki Y, Iida T, et al. Perioperative management of patients with end-stage renal disease. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31(6):2251-2267. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones DR, Lee HT. Surgery in the patient with renal dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1083-1093. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yee J, Parasuraman R, Narins RG. Selective review of key perioperative renal-electrolyte disturbances in chronic renal failure patients. Chest. 1999;115(5)(suppl):149S-157S. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.suppl_2.149S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renew JR, Pai SL. A simple protocol to improve safety and reduce cost in hemodialysis patients undergoing elective surgery. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2014;22(5):487-492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng J, Lenart J, Applegate RL. General anesthesia soon after dialysis may increase postoperative hypotension: a pilot study. Heart Lung Vessel. 2014;6(1):52-59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States Renal Data System . 2020 United States Renal Data System annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://adr.usrds.org/2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Chapter 8 in Medicare Claims Processing Manual: outpatient ESRD hospital, independent facility, and physician/supplier claims. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c08.pdf

- 14.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project . Surgery Flags Software for Services and Procedures. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/surgeryflags_svcproc/surgeryflagssvc_proc.jsp

- 15.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . PFS relative value files. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/PFS-Relative-Value-Files

- 16.Childers CP, Dworsky JQ, Russell MM, Maggard-Gibbons M. Association of work measures and specialty with assigned work relative value units among surgeons. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(10):915-921. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.2295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project . Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures. Accessed July 5, 2021. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs_svcsproc/ccssvcproc.jsp

- 18.Lin E, Kurella Tamura M, Montez-Rath ME, Chertow GM. Re-evaluation of re-hospitalization and rehabilitation in renal research. Hemodial Int. 2017;21(3):422-429. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foley RN, Gilbertson DT, Murray T, Collins AJ. Long interdialytic interval and mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1099-1107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boney O, Moonesinghe SR, Myles PS, Grocott MPW; StEP-COMPAC group . Core Outcome Measures for Perioperative and Anaesthetic Care (COMPAC): a modified Delphi process to develop a core outcome set for trials in perioperative care and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128(1):174-185. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirji S, McGurk S, Kiehm S, et al. Utility of 90-day mortality vs 30-day mortality as a quality metric for transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement outcomes. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(2):156-165. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talsma AK, Lingsma HF, Steyerberg EW, Wijnhoven BPL, Van Lanschot JJB. The 30-day versus in-hospital and 90-day mortality after esophagectomy as indicators for quality of care. Ann Surg. 2014;260(2):267-273. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.In H, Palis BE, Merkow RP, et al. Doubling of 30-day mortality by 90 days after esophagectomy: a critical measure of outcomes for quality improvement. Ann Surg. 2016;263(2):286-291. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santosa KB, Lai Y-L, Oliver JD, et al. Preoperative opioid use and mortality after minor outpatient surgery. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(12):1169-1171. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siracuse JJ, Shah NK, Peacock MR, et al. Thirty-day and 90-day hospital readmission after outpatient upper extremity hemodialysis access creation. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(5):1376-1382. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Census Bureau . American Community Survey 5-year median income tables: table S1903. Accessed October 5, 2021. http://data.census.gov

- 27.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholas SB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Norris KC. Racial disparities in kidney disease outcomes. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33(5):409-415. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133(6):601-609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pintilie M. Analysing and interpreting competing risk data. Stat Med. 2007;26(6):1360-1367. doi: 10.1002/sim.2655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; 1987. doi: 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin PC. Absolute risk reductions and numbers needed to treat can be obtained from adjusted survival models for time-to-event outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(1):46-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Ambrogi F, Bokov AF, Gu H, de Beurs E, Eskaf K. Estimate risk difference and number needed to treat in survival analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(7):120. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.01.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas LE, Li F, Pencina MJ. Overlap weighting: a propensity score method that mimics attributes of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2417-2418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Quan H, Ghali WA. Adapting the Charlson Comorbidity Index for use in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(1):125-132. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(03)00415-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mullen MG, Michaels AD, Mehaffey JH, et al. Risk associated with complications and mortality after urgent surgery vs elective and emergency surgery: implications for defining “quality” and reporting outcomes for urgent surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):768-774. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fotheringham J, Fogarty DG, El Nahas M, Campbell MJ, Farrington K. The mortality and hospitalization rates associated with the long interdialytic gap in thrice-weekly hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2015;88(3):569-575. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H, Schaubel DE, Kalbfleisch JD, et al. Dialysis outcomes and analysis of practice patterns suggests the dialysis schedule affects day-of-week mortality. Kidney Int. 2012;81(11):1108-1115. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhee CM. Serum potassium and the long interdialytic interval: minding the gap. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(1):4-7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Clinical Classifications Software Organ System Groups

eTable 2. Current Procedural Terminology Codes for Common Surgical Procedures Subgroup Analysis

eTable 3. Clinical Classification Software Categories for Minor Eye, Skin, and Vascular Procedures Subgroup Analysis

eTable 4. Supplemental Patient Characteristics by Days Between Last Hemodialysis and Procedure

eTable 5. Common Clinical Classification Software Procedure Categories

eTable 6. Patient and Procedure Characteristics, by Presence of an Additional Hemodialysis Session on the Day of Procedure

eTable 7. Primary Outcome Model—Alternative Reference Levels for Same-Day Hemodialysis Subgroup Analysis

eTable 8. Post Hoc Secondary Outcome and Subdistribution Hazard Models

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analyses—Association Between Days Between Last Hemodialysis and Procedure and 90-Day Postoperative Mortality

eTable 10. Secondary Outcome Models—Alternative Reference Levels for Same-Day Hemodialysis Subgroup Analysis

eMethods

eFigure 1. Directed Acyclic Graph of Hypothesized Relationships Between Key Model Variables

eFigure 2. Cumulative Incidence of 30-Day Postoperative Mortality

eFigure 3. Ninety-Day Postoperative Mortality With and Without an Additional Same-Day Dialysis Session for Patients with 1 Day Between Last Hemodialysis and Surgery

eFigure 4. Love Plots for Unadjusted and Overlap-Weighted Models

eReferences