Abstract

Nanomaterials are prospective candidates for the elimination of viruses due to their multimodal mechanisms of action. Here, we tested the antiviral potential of a largely unexplored nanoparticle of cerium dioxide (CeO2). Two nano-CeO2 with opposing surface charge, (+) and (−), were assessed for their capability to decrease the plaque forming units (PFU) of four enveloped and two non-enveloped viruses during 1-h exposure. Statistically significant antiviral activity towards enveloped coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus was registered already at 20 mg Ce/l. For other two enveloped viruses, transmissible gastroenteritis virus and bacteriophage φ6, antiviral activity was evidenced at 200 mg Ce/l. As expected, the sensitivity of non-enveloped viruses towards nano-CeO2 was significantly lower. EMCV picornavirus showed no decrease in PFU until the highest tested concentration, 2000 mg Ce/l and MS2 bacteriophage showed slight non-monotonic response to high concentrations of nano-CeO2(−). Parallel testing of antiviral activity of Ce3+ ions and SiO2 nanoparticles allows to conclude that nano-CeO2 activity was neither due to released Ce-ions nor nonspecific effects of nanoparticulates. Moreover, we evidenced higher antiviral efficacy of nano-CeO2 compared with Ag nanoparticles. This result along with low antibacterial activity and non-existent cytotoxicity of nano-CeO2 allow us to propose CeO2 nanoparticles for specific antiviral applications.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Nanoscience and technology

Introduction

The search for antiviral agents—materials that enable to inactivate viruses, inhibit their capability to infect their host cells or suppress their ability to replicate1, has clearly intensified with the current COVID-19 pandemic2. Recently, the potential of nanotechnology in the development of antiviral therapeutics has been acknowledged3–7. One of the groups of potential antiviral nanomaterials is metal and metal oxide nanoparticles8 that have been suggested to exert their activity via multimodal mechanisms of action9, including direct binding to virus surface, inhibiting viral binding to host cells or even interacting with viral genome10. Such a broad spectrum of proposed antiviral activities of metal-based nanoparticles may result in a smaller likelihood of developing antiviral resistance, which may occur in case of conventional antiviral drugs11.

A wealth of literature has already been published on antiviral nanoparticles. As of January 2022, 1,623 articles were retrieved from ISI Web of Science using keywords “antiviral” AND “nanoparticle*”. Out of those 17% mentioned “COVID” while 30% included “silver”, 5% “copper”, 5% “zinc” and 4% “titanium OR titania”. Interestingly, all those nanoparticles are also among the most utilized nanoparticles in antibacterial applications12 indicating that a relatively general mechanism of action, effective against both, bacteria and viruses, may be expected. Nanosilver contributing to 1/3 articles on antiviral nanoparticles, is clearly one of the most studied antiviral nanoparticle types. Potential binding of nanosilver particles onto the outer surface of the viruses and binding of nanoparticles to viral genetic material, leading to further inhibition of virus replication, have been suggested as its modes of action13. Efficacy of silver nanoparticles in decreasing the infective viral counts has been demonstrated against a variety of viruses, including HIV14–17, herpes simplex virus18, influenza virus19, noroviruses20 adenoviruses as well as SARS -CoV-221 and other viruses22–25. It is however worth mentioning that while the antiviral concentrations of silver nanoparticles usually range between tens and hundreds of mg/l26, those concentrations may already lead to cytotoxicity21 and certainly exhibit antibacterial effect, that usually is evidenced starting from low mg/l range27. Indeed, unspecific cytotoxicity and concurrent potential health hazard of some of the proposed nanoparticles may be an issue28 and thus, safer nanoparticle alternatives with lower potential health hazards are certainly of interest.

In search for antivirally effective materials with low activity towards human cells or microbiota, we focused on CeO2-based nanomaterials. Previously, the antiviral activity of ceria nanoparticles has been suggested in a few papers that concerned influenza virus H1N1 and herpes simplex virus29,30, Sabin-like poliovirus31 and vesicular stomatitis (VS) virus30. Although the mechanism of antiviral activity of CeO2 nanoparticles has not been studied thoroughly, some studies suggest that defects in CeO2 crystal structure may be responsible for its biological activity30. Such defects have been shown to lead to redox reaction Ce(III) ⇔ Ce(IV)of on the surface resulting in filling or formation of oxygen vacancies32, and ultimately to the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) from nanoparticles surface33. Interestingly, this formation of ROS by CeO2 has been correlated with the acidity of the surrounding environment, thus increasing toxicity in bacteria34 as well as cancer cells31 at low pH values. In in vitro tests with normal mammalian cells and less acidic pH, no significant cytotoxicity of CeO2 nanoparticles has been observed but instead, a protective, survival and growth promoting effect has been demonstrated35,36. It has been proposed that these protective effects have been caused by entrapment of free radicals by CeO2 and thus, reduction of ROS-induced oxidative stress37,38. This combination of potential antiviral activity and low general toxicity suggests that CeO2 materials may be indeed potent antivirals with low side effects.

The aim of this work was to reveal the antiviral activity of ultrasmall CeO2 nanoparticles towards a selection of enveloped and non-enveloped mammalian viruses and selected bacteriophages. In parallel to CeO2 nanoparticles we tested the antiviral activity of nanoparticles of silver that are generally considered to exhibit a significant antiviral activity, and silica (SiO2) presumably biologically inert39. To reveal the cause of antiviral activity of CeO2 nanoparticles, we studied the potential surface protein inactivation by those nanoparticles using SARS-CoV-2 as an example. Finally, the antiviral potency of CeO2 and other selected nanoparticles was compared with their bactericidal activity towards Gram-negative Escherichia coli and Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and cytotoxic effects.

Results and discussion

Characterization of nanoparticles

Although the emphasis of this work was on antiviral effects of CeO2 nanomaterials, nanoparticles of Ag and SiO2 were added to the testing as controls for a generally approved antiviral agent and an inert nanoparticle (Table 1). Acknowledging the importance of nanoparticles surface in their biological effects, nano-CeO2 were synthesized with two different states of surface, those with nearly “bare” surface carrying large positive charge (nano-CeO2(+)) and nanoparticles stabilized by citric ions and, thereby presenting negatively charged surface (nano-CeO2(−)). Nano-CeO2(+) were synthesized at maximal concentration of 6500 mg Ce/l (ca. 45 mM) and nano-CeO2(−) at 8200 mg Ce/l (ca. 60 mM). Hereafter, in described experiments, mg/l concentration for investigated compounds always refers to milligrams per liter of the element, i.e. Ce, Ag or Si.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of nanoparticles used.

| Nanoparticle | TEM size, nm | Hydrodynamic sizea, nm | ζ potential, mV |

|---|---|---|---|

| nano-CeO2(+) | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 7.0 ± 3.0 | + 41 ± 2 |

| nano-CeO2(−) | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 2.0 | − 53 ± 4 |

| nano-Ag | 15.3 ± 3.0 | 18.5 ± 3.0 | − 52 ± 5 |

| nano-SiO2 | 16.6 ± 1.9 | 45 ± 5 | − 34 ± 3 |

aNumber based hydrodynamic size according to DLS (dynamic light scattering) measurements.

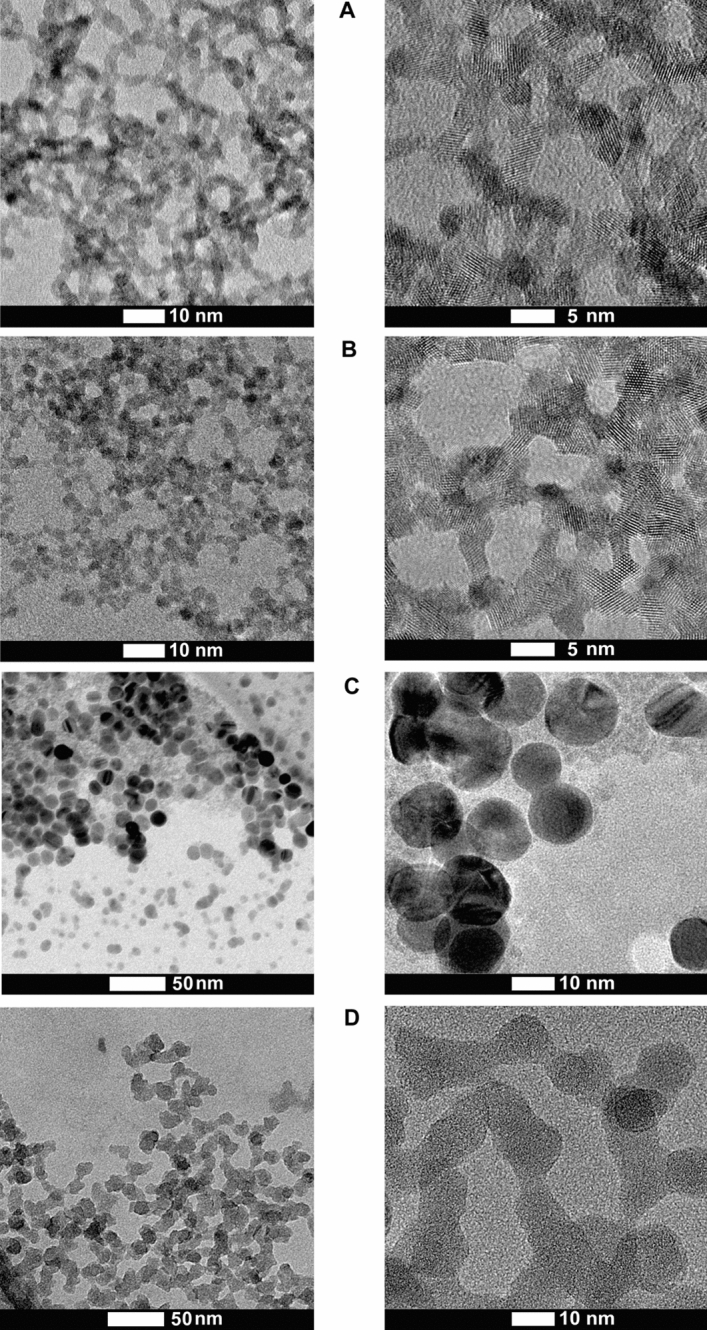

As synthesized, nano-CeO2(+) and nano-CeO2(−) formed stable aqueous colloids due to their large (+ 41 mV or − 53 mV, respectively) ζ-potential (Table 1). According to high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (representative TEM images of CeO2 nanoparticles are shown on Fig. 1), the average particle size of both, nano-CeO2(+) and nano-CeO2(−) was close to 3 nm (Fig. S1). Dynamic light scattering-measured hydrodynamic size of nano-CeO2(−) determined at highest tested antiviral concentration was relatively close to the particles primary size (Table 1) and only nano-CeO2(+) showed some aggregation. Interestingly, with decrease in nano-CeO2 concentration apparent increase in particle size and thus, the likelihood for aggregation was observed with decreasing particle concentration for both, nano-CeO2(+) and nano-CeO2(−), whereas the latter was more sensitive to dilution-mediated instability (Fig. S2). We suggest that desorption of stabilizing citric ions from the surface of nanoparticles upon dilution of colloid lead to the thinning of nanoparticles double electric layer and deteriorated colloidal stability.

Figure 1.

HRTEM images of synthesized nanoparticles. (A) Nano-CeO2(+), (B) nano-CeO2(−), (C) nano-Ag, (D) nano-SiO2.

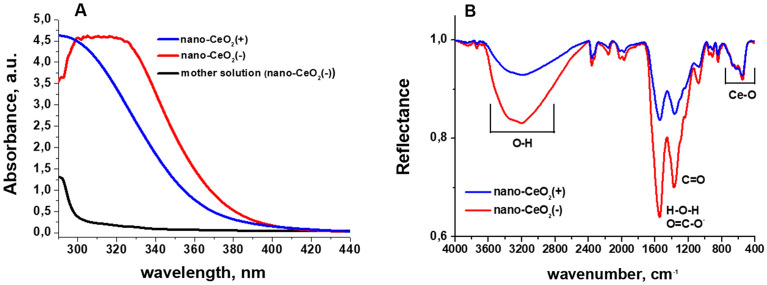

UV–Vis spectra of CeO2 nanoparticles (Fig. 2A) showed that compared to nano-CeO2(+) the fundamental absorption edge of nano-CeO2(−) was approximately 10 nm red shifted. Also, visibly, the colloid of nano-CeO2(−) showed a deeper yellow color compared to nano-CeO2(+). This difference in shift of absorption edge may be due to the different Ce(III)/Ce(IV) ratio on the surface of nanoparticles, or originate from oxidized and polymerized citrate ions on the surface of nano-CeO2(−) particles, as a remnant of the synthesis process. The seeming “drop” of the absorption of nano-CeO2(−) colloid below 300 nm is a compensation error due to a symmetric rise of absorption of the mother solution (the liquid remaining after centrifugation of nanoparticles) of this colloid caused, most likely, by a high concentration of citrate ions and products of their oxidation and/or complexing with cerium ions. Infrared (IR) spectrum of the synthesized nano-CeO2 (Fig. 2B) is in agreement with the literature data40 and exhibits peaks in around 3600 to 3200 cm−1, which correspond to –OH stretching of absorbed water and surface OH-groups. Peaks around 1600 cm−1 and 1400 cm−1 are H–O–H deformational vibrations and C–O stretching vibrations from surface water molecules and carbonate ions, respectively. The peak from 700 to 500 cm−1 is due to Ce–O stretching vibrations. The differences between nano-CeO2(+) and nano-CeO2(−) spectra are mainly intensities of peaks around 1600 cm−1 and 1400 cm−1, which in case of nano-CeO2(−) correspond also to COO– group vibrations of absorbed citrate ions41. Also we observed a small blue-shift of the band from 1539 cm−1 nano-CeO2(+) to 1546 cm−1 for nano-CeO2(−), which is probably due to summing of H–O–H deformational vibrations with anti-symmetric COO– group stretching band with maximum should be around 1585 cm−1 according to literature data41. Together with DLS data, UV–Vis and IR-spectroscopy clearly show, that despite very close mean particle size, shape, and size distribution parameters, nano-CeO2(+) and nano-CeO2(−) particles are chemically and electrostatically rather different and, therefore, we can expect from them different effect on biological objects. The experimentally established (by means of ICP-MS) concentrations of Ce3+/Ce4+ ions in supernatants from 1.4 × 10–2 M (2000 mg Ce/l) CeO2 colloids were rather low: 8 × 10–5 M (12 mg Ce/l) for CeO2(+) and 1.7 × 10–4 M (24 mg Ce/l) for CeO2(−). These values are yet significantly higher than literature data42, which should be in the range of 10–7–10–8 M, in water at neutral pH range, and probably are the result of incomplete separation of the nanoparticles. However, even measured concentration should have minimal effect on the viruses.

Figure 2.

Characteristics (A) UV–Vis spectra and (B) infrared spectra of nano-CeO2(+) and nano-CeO2(−). On (A) also the UV–Vis spectrum of nano-CeO2(−) mother solution is shown.

The synthesis of nano-Ag was carried out through seed-mediated citrate route and the maximum concentration reached was 480 mg/l (corresponds to 4.4 mM). Nano-SiO2 was synthesized using Stöber technique and the maximum concentration reached for amorphous silica nanoparticles was 3100 mg/l (corresponds to 110 mM). Both, nano-Ag and nano-SiO2 particles were spherical with average primary size around 15 nm (Table 1). According to hydrodynamic size and DLS analysis, nano-Ag remained in non-aggregated state while nano-SiO2 exhibited a certain level of aggregation and formation of 2–10 nanoparticle aggregates. The surface ζ-potential of nano-Ag and nano-SiO2 particles was negative (− 52 ± 5 and − 34 ± 3 mV, respectively) being comparable to nano-CeO2(−), thus allowing the comparison of their biological effects. Unfortunately, we were unable to synthesize neither silica nor silver nanoparticles with primary size comparable to CeO2 nanoparticles without the addition of strong surfactants that would have their own pronounced antimicrobial properties.

Antiviral activity of CeO2 nanoparticles

For the demonstration of antiviral potency of nano-CeO2, nano-SiO2 and nano-Ag, we analyzed the decrease of infective counts (expressed as plaque forming units, PFU) of four mammalian viruses and two bacteriophages after 1-h contact with nanoparticles. Nano-CeO2 with both positive and negative surface ζ potentials were used to understand the effect of CeO2 surface in their antiviral activity. To rule out the possibility that the antiviral activity is only due to the nanometer scale particle size, parallel antiviral activity testing was performed with supposedly biologically inert, low toxicity SiO2 nanoparticles. Conversely, nano-Ag particles that are widely considered to exhibit antiviral effect, were tested as positive controls in antiviral tests (see Table 2). Despite the very low potential CeO2 solubility, we also tested the antiviral effect of soluble Ce(III) compound Ce(NO3)3 as a source of Ce3+ ions. Although both, Ce3+ and Ce4+ ions could form at low concentration during the dissolution of CeO2, Ce3+ ions were used due to their higher likelihood of presence42.

Table 2.

Characteristics of viruses used in antiviral assays.

| Virus | Characteristics | Nanoparticle or compound* | Purpose | Concentration range tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A/WSN/1933 | Enveloped virus, family Orthomyxoviridae, seasonally important to cause flu in Northern hemisphere | Nano-CeO2(+) | Proposed antiviral compound | 0.002–2000 μg Ce/ml** |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Enveloped virus, family Coronaviridae, causes COVID-19 | Nano-CeO2(−) | Proposed antiviral compound | 0.002–2000 μg Ce/ml** |

| TGEV | Enveloped virus, family Coronaviridae, transmissible gastroenteritis virus of pigs | Ce(NO3)3 | Control for Ce(III) ion effects | 0.002–2000 μg Ce/ml** |

| EMCV | Non-enveloped virus, family Picornaviridae causative agent for neurological disorders | Nano-Ag | Nanoparticle with previously demonstrated antiviral activity | 0.0015–1500 μg Ag/ml** |

| Ф6 | Enveloped bacteriophage of Pseudomonas sp. | Nano-SiO2 | Proposed inert nanoparticle | 0.0004–400 μg Si/ml** |

| MS2 | Non-enveloped bacteriophage of Escherichia coli |

Right side of the table shows characteristics and concentrations of nanoparticles and chemical compounds used in antiviral assays with every virus listed in the left side of the table.

*All the compounds were tested with all the viruses.

**All the tested nanoparticles and chemicals were in the range of 0.014–14,000 μM.

Our selection of viruses included mammalian and bacterial, both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses (Table 2). In general, enveloped viruses surrounded by a lipid membrane have been considered more sensitive to inactivation by various environmental conditions than non-enveloped viruses possessing only a proteinaceous capsid43. Pathogenic viruses can belong to either of these groups, therefore, most of the antiviral testing standards foresee the inclusion of both types of viruses44,45. The enveloped mammalian viruses used in this study included influenza virus46, SARS-CoV-2 and TGEV47, and picornavirus EMCV was used as a model of the non-enveloped mammalian viruses48. Enveloped Ф649 and non-enveloped MS250 were used as respective bacterial virus (bacteriophage) examples. Both of those phages have been suggested as models for antiviral testing51–54. In case of all the viruses, exposure to nanoparticles was carried out in sterile water or highly diluted growth medium over 1 h. The numbers of infectious viral particles with and without treatments were expressed as plaque forming units (PFU/ml).

Prior to antiviral activity testing, the effect of all the tested compounds was studied on viral host cells. Most of the tested compounds and concentrations were non-cytotoxic to the host cells of mammalian viruses (Fig. S3). Only the highest tested concentrations of nano-Ag, Ce(NO3)3 or SiO2 decreased the viability of some of the host cell lines, which however did not interfere with antiviral assays, where the concentrations of those compounds did not reach the toxic levels. Except for nano-Ag none of the compounds affected the growth of host bacteria of bacteriophages. As nanosilver is well known for its antibacterial effects, its bacterial toxicity that was observed from 14 μM (1.5 mg/l) was not a surprise. To be able to study the effects of nano-Ag towards bacteriophages, its bacterial toxicity was neutralized by the addition of threefold molar excess of l-cysteine to the infection reaction immediately prior to the plaque assay step.

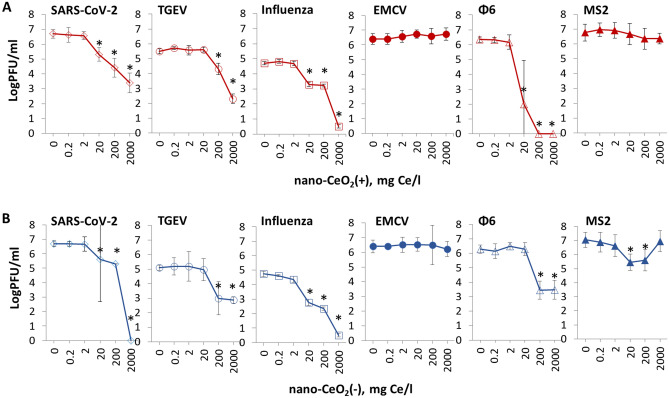

The results of antiviral assay showed that despite being non-toxic to mammalian cells and bacteria, nano-CeO2 affected the infectivity of most of the mammalian viruses and bacteriophages (Fig. 3). Significant decrease (p ≤ 0.05) of viral infectivity due to 1-h nano-CeO2(+) exposure was observed starting from 20 mg/l in case of SARS-CoV-2, influenza virus and ф6, and starting from 200 mg/l in case of TGEV (Table 3). None of the non-enveloped viruses showed significant decrease in infectivity for nano-CeO2(+) up to 2000 mg/l. Nano-CeO2(−) affected the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus starting from 20 mg/l and the infectivity of TGEV and ф6 starting from 200 mg/l (Table 3). Following the trend of nano-CeO2(+), non-enveloped viruses showed the lowest sensitivity towards nano-CeO2(−). EMCV infectivity was not affected by nano-CeO2(−) up to 2000 mg/l, and the response of non-enveloped bacteriophage MS2 to nano-CeO2(−) was non-monotonic so that 20 and 200 mg/l of the compound decreased the infectivity, but no effect was observed at 2000 mg/l. Such a non-monotonic effect on antiviral activity could not be explained by increasing aggregation level of CeO2 at higher concentration as according to hydrodynamic size measurement, as nano-CeO2 were non-aggregated at higher concentrations and particle aggregation and instability increased with dilution level of the particles (Fig. S2). Non-monotonic response has been shown also for other types of nanomaterials. For example, TiO2 exhibits non-monotonic UV light-induced toxicity to freshwater organisms55. In case of CeO2 nanoparticles, earlier reports can be found on non-monotonic toxicity towards soybean plants56, however, its exact causes are still to be clarified.

Figure 3.

The effect of nano-CeO2(+) (A) and nano-CeO2(−) (B) on viral plaque forming activity (log PFU/ml). Enveloped mammalian viruses and bacteriophages are shown with open symbols; closed symbols represent non-enveloped mammalian viruses and bacteriophages. The differences in initial viral titers are caused by different viral yields in laboratory conditions. *p < 0.05.

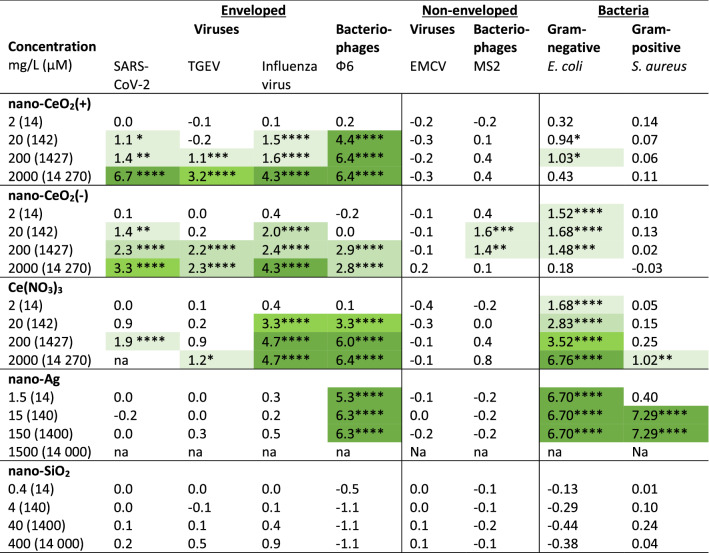

Table 3.

Antiviral or bactericidal activity at different concentrations of nanoparticles and Ce(NO3)3 (numerical data from Figs. 4, 6).

Antiviral activity is expressed as log reduction in infectious viral titer compared to unexposed control after 1 h. Bactericidal activity is expressed as log reduction in viable counts compared to unexposed control after 1 h. Concentrations causing at least 1 log (90%), 2 logs (99%), 3 logs (99.9%) and 4 logs (99.99%) decrease are indicated with light to dark green color gradient. A minimum of 2 log reduction (99%) in viable bacterial count or infectious viral titer is generally considered as lowest biologically meaningful activity in antimicrobial applications while at least 4 log reduction within up to 1 h is required from biocidal products in suspension tests in the framework of European legislation64.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001.

Although we proposed that due to the chemical and electrostatic differences between the surface of nano-CeO2(+) and nano-CeO2(−) those nanoparticles may exhibit different biological effects, our results showed no notable differences between the antiviral properties of those two types of particles (Table 3).

Comparison of our results on antiviral properties of nano-CeO2 with earlier reports is rather difficult due to the variable nature of the nanoparticles, as well as methods used for antiviral activity assessment. However, certain comparisons may be made. For example, in a 2010 study, 2 log reduction of enveloped Enterobacter aerogenes infecting bacteriophage UZ1 PFUs was observed after its 2-h exposure to 50 mg/l CeO2 whereas 500 mg/l of CeO2 was sufficient to decrease infectivity by 4 logs57. Mohamed et al.31 showed that 14 nm sized nano-CeO2 at concentrations less than 50 mg/l removed all the infectious viral particles (PFU) of type 1 Sabin-like poliovirus and the authors even suggested CeO2 nanoparticles as an alternative to treatment of polio infection. Yet there are also reports showing no effect by CeO2 nanoparticles on viruses. According to Neal et al.58 200 mg/l of CeO2 nanoparticles did not have any significant effect on infectivity of human coronavirus OC43 or rhinovirus RV14 after 6 h incubation. However, after doping of CeO2 with Ag, antiviral activity of CeO2 nanoparticles was achieved, according to authors, due to the presence of increased proportion of Ce(III) ions on the nanoparticles surface, as well as the presence of silver nanoparticles, their size, morphology and the density of their population on CeO2 surface. Overall, these few articles published so far on antiviral efficacy of CeO2 have demonstrated relatively variable results, which may be attributed to differences in physico-chemical properties of nanoparticles, to different viruses used or antiviral assays applied. However, based on the few earlier studies demonstrating antiviral effects of nano-CeO231,57 and the results of our study, we may suggest that nanoceria has a significant potential in antiviral treatments and that this potential should be studied and developed further.

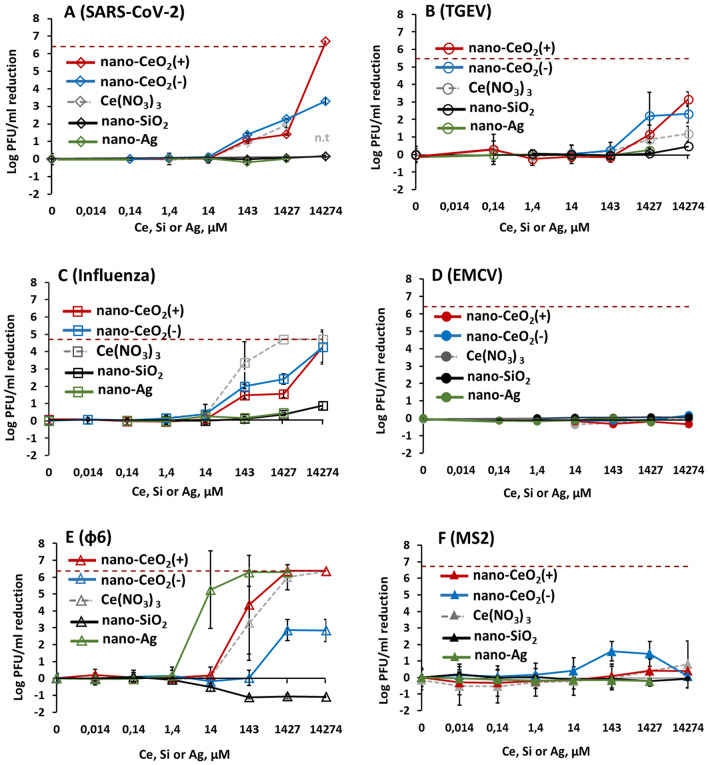

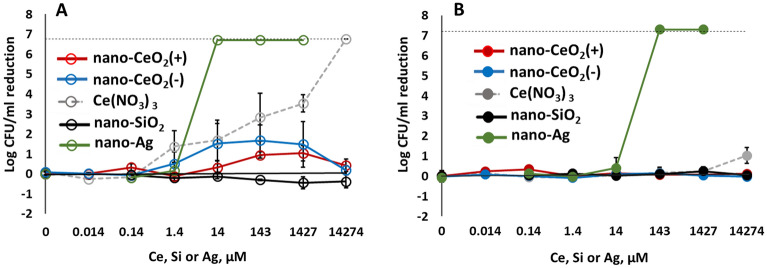

Comparison of the antiviral efficacy of nano-CeO2 in comparison with nano-SiO2 that was used as a negative control, and nano-Ag used as a positive control due to its likely antiviral properties are shown in Fig. 4. Expectedly, the non-enveloped viruses that did not show any sensitivity towards nano-CeO2 were also not influenced by nano-SiO2 or nano-Ag (Fig. 4D,F). The inexistent antiviral effect of SiO2 nanoparticles was expected as silica is considered biologically compatible or generally regarded as safe59,60 and of low toxicity. We found no published data that would have indicated an antiviral activity of SiO2 nanoparticles. Yet silica nanoparticles have been shown to impede antiviral response to norovirus infection, reducing the viability of macrophages61.

Figure 4.

Antiviral activity of all tested nanoparticles and chemical compounds expressed in µM concentrations to enable comparison. Please note that antiviral activity is expressed as reduction of infectious viral titer, logPFU per ml compared to unexposed control after 1 h. The data of nano-CeO2 are transferred from Fig. 3. (A) coronavirus SARS-CoV-2; (B) transmissible gastroenteritis virus TGEV; (C) influenza virus A/WSN/1933; (D) picornavirus EMCV; (E) bacteriophage ф6; (F) bacteriophage MS2. Closed symbols in (D,F) represent non-enveloped viruses. The results of three independent experiments with standard deviation are shown. Note the logarithmic scale of y-axis. Horizontal dark red dashed line shows the limit of quantification of PFU reduction.

While the low antiviral activity of SiO2 was anticipated, our results indicating no significant antiviral activity of nano-Ag up to 150 mg/l (1.4 mM), except for bacteriophage ф6 (Table 2) were surprising. Earlier studies have suggested that nanosilver may affect viruses in a variety of ways; through interactions with viral surface and subsequently interfering the viral attachment to its targets, inhibition of viral penetration into host cells or even by interacting with viral genome26, and that silver nanoparticles are affecting viruses already starting from tens of mg/l. However, interestingly, a closer look to Ag nanoparticles antiviral results revealed that in most of the studies only a relatively small, less than 1 log (< 90%) decrease in infectivity has been observed. Yadavalli et al.8 have shown inhibition of 50% HIV by Ag nanoparticles between 25 and 5000 mg/l, Rogers et al.24 have demonstrated 60–80% decrease in monkeypox virus plaque formation activity in the presence of 20–2000 mg/l of Ag nanoparticles. Up to 90% inhibition of human parainfluenza virus in the presence of 0.1–9 mg/l Ag nanoparticles has been demonstrated by Gaikwad et al.62. Slightly higher, up to 2 log decrease of influenza virus titer was observed in response to 50–70 mg/l Ag nanoparticles treatment63 and Castro-Mayorga et al.20 demonstrated 4 log decrease of median tissue culture infectious dose of feline calicivirus after exposure to 10 mg of nano-Ag/l. Considering that the decrease of viral titers ≥ 2 log can be regarded as the lowest biologically meaningful activity in antimicrobial applications and at least 4 log reduction within up to 1 h is required for biocidal products in suspension tests in the framework of European legislation64, there is only little objective proof that Ag nanoparticles would be effective antivirals from the point of view of these requirements. Therefore, our conclusion on low antiviral activity of nano-Ag in terms of log PFU decrease during 1-h exposure (Table 2) is at broad level in line with the previous reports. However, in general view this conclusion is rather surprising as it does not prove the antiviral efficacy of nanosilver contrary to the common belief.

The mechanism of antiviral activity of nano-CeO2

There is no clear mechanism of action proposed as the basis of antiviral activity of CeO2 nanoparticles. The elemental analysis of the mother solution compared with literature data allowed us to exclude the possibility of the action of CeO2 nanoparticles via released Ce ions65. The equilibrium concentration of released ions was found to be extremely low (10–7–10–8 M)42,66 and our experiments with Ce(NO3)3 showed that the antiviral activity Ce3+ ions can be only evidenced at concentrations several orders higher than achievable due to dissolution of CeO2 nanoparticles (Fig. 4).

As a different mechanism of inactivating viruses, binding of CeO2 nanoparticles on viral genetic material has been reported. Link et al.67 showed high binding capacity of nanoparticles of CeO2 for nucleic acids in adeno-associated virus, adenovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, and murine leukemia virus67. Binding of nanoparticles onto the genetic material of viruses could however take place only when the latter is non-protected by the capsid, e.g., during replication. Another mode of binding has been proposed by Neal et al.58, who suggested that Ag-doped CeO2 nanoparticles may physically interact with the membrane of enveloped viruses, thus leading to the disruption of their lipid bilayer. In case of non-enveloped viruses, an interaction with virion proteins was suggested.

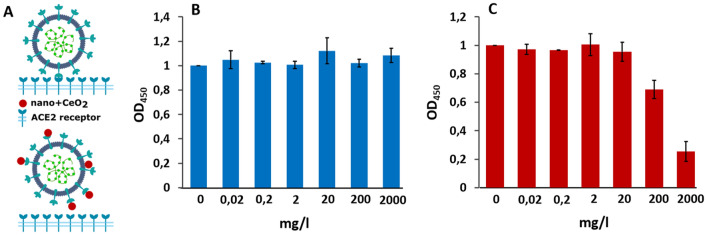

As our antiviral assay involved exposure of whole virions to nanoparticles prior to cell infection, we analyzed whether nano-CeO2 could affect the binding of a virus to its natural ligand. ELISA assay was performed to measure the in vitro binding activity of nano-CeO2 exposed SARS-CoV-2 to its cellular target, the human recombinant ACE2 receptor (Fig. 5). Interestingly, exposure of SARS-CoV-2 to nano-CeO2(−) and nano-CeO2(+) affected the virus somewhat differently. While exposure of SARS-CoV-2 to ≥ 200 mg/l of nano-CeO2(−) inhibited the binding of the virus to ACE2, exposure of SARS-CoV-2 to nano-CeO2(+) had no observable effect. However, as the antiviral profiles of both CeO2 nanoparticles were relatively similar, these results do not allow us to claim that surface binding and blocking of ligand binding are the leading mechanism of antiviral action of nano-CeO2 evidenced by us in antiviral assays. Therefore, the mode of action driving the antiviral effect of CeO2 nanoparticles is to be elucidated in future studies.

Figure 5.

Schematics of the experiment (A), where the upper part shows SARS-CoV-2 binding to ACE2 receptor without nanoparticles and lower part demonstrates the theoretical inhibition of SARS-CoV2 binding to ACE2 receptor by of CeO2 nanoparticles. (B) Shows the effect of nano-CeO2(+) and (C) the effect of nano-CeO2(−) particles on binding of SARS-CoV-2 onto ACE2 receptor in an ELISA assay, measured as optical density (OD450).

Bactericidal effect of CeO2 nanoparticles

In parallel to antiviral properties, antibacterial activity towards the Gram-negative Escherichia coli and Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus was analyzed. According to our results, neither nano-CeO2(+) nor nano-CeO2(−) up to 2000 mg/l decreased the viable counts (expressed as colony-forming units, CFU) of E. coli or S. aureus by more than 2 logs (99%) (Fig. 6, Table 3), indicating that the antiviral effect of CeO2 nanoparticles was more pronounced than their bactericidal efficacy. Comparison of smaller changes than 2 log decrease in CFU levels in E. coli and S. aureus showed that Gram-negative E. coli was affected by nano- CeO2 to a higher extent than Gram-positive S. aureus (Table 3). While nano-CeO2(−) concentrations of 2, 20 and 200 mg/l decreased the number of E. coli CFUs by 1.48–1.68 logs, no decrease in viable counts of S. aureus in response to nano-CeO2 was observed. Interestingly, the response of E. coli was non-monotonous as also in case of non-enveloped bacteriophage MS2. The higher sensitivity of Gram-negative bacteria compared with Gram-positive bacteria against nano-CeO2 particles has been shown also in earlier studies and has been related to redox activity of nanoceria and the ability of a thicker peptidoglycan layer to alleviate this effect68. In the literature, variable results can be found on antibacterial effects of CeO2 nanoparticles, both due to the variety of nanoparticles used as well as due to the different antibacterial assays applied. The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of nano-CeO2 towards a series of Gram-positive and -negative bacteria has been shown to vary between 20 and 140 mg/l69,70. Another study where nanoparticles of CeO2 were prepared using surfactant Tween-80, demonstrated MIC of 150 mg/l whereas without the surfactant the MIC value was 3000 mg/l71. In another study, complete inactivation of E. coli was achieved in the presence of 1000 mg/l of CeO2 nanoparticles72. Thus, our result showing no significant antibacterial activity of CeO2 towards Gram-positive S. aureus (Table 2) and relatively modest antibacterial effect towards Gram-negative E. coli up to 2000 mg/l, coincided with some of the results published earlier but differed from others, respectively.

Figure 6.

Bactericidal activity after 1 h exposure to nano-CeO2, Ce(NO3)3, nanoparticles of SiO2 and Ag against Gram-negative Escherichia coli (A) and Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (B). Bactericidal activity is expressed as log reduction in viable counts compared to unexposed control after 1 h. Results of three independent experiments with standard deviation are expressed as reduction of log CFU/ml. The dotted line indicates a limit of quantification.

Differently from nano-CeO2 that showed significant or relatively modest antibacterial effect, nano-Ag particles demonstrated significant antibacterial effect already at 1.5 mg/l. Expectedly Gram-negative bacteria were more sensitive towards nano-Ag and at 1.5 mg/l, already more than 4 logs decrease in E. coli viable counts was observed. Viability of Gram-positive S. aureus decreased by > 4 log from 15 mg nano-Ag/l (Fig. 6, Table 3). These results are in agreement with earlier studies that have shown the efficacy of Ag nanoparticles starting from low mg/l range27. Indeed, silver nanoparticles that are shown to act via silver ion release and ROS formation73 and the following interaction between Ag ions and thiol groups of proteins as well as permeabilization of bacterial membrane, have been generally regarded as the nanoparticles with highest antibacterial activity. In January 2022, more than 18,000 articles were registered in ISI WoS on “nano* AND silver* AND antibacter*”.

Nanoparticles of SiO2, generally regarded as harmless, did not show any bacterial toxicity in our experiments. Inexistent antibacterial activity of nano-SiO2 alone has been shown also in other studies, however, most of the papers on SiO2 used silica nanoparticles as carriers of more biologically active metal ions or other nanoparticles and thus, are not an adequate comparison for our purpose.

Conclusion

In this study, we analyzed the decrease of viral infectivity due to exposure to CeO2 nanoparticles. According to a few earlier studies, CeO2 materials may exhibit significant antiviral activity while being relatively harmless towards human cells and even protecting cells from environmental stress. This suggests that CeO2 nanoparticles could be considered as promising antivirals. Our analysis of the activity of two types of CeO2 nanoparticles towards four enveloped viruses demonstrated more than 2 logs (99%) decrease in viral infectivity after exposure to 20–200 mg Ce/l of nano-CeO2 and more than 4 logs (99.99%) decrease in infectivity after exposure to 200–2000 mg/l. The two non-enveloped viruses were expectedly less sensitive towards nano-CeO2; one of them, the EMCV picornavirus showed no decrease in infectivity until the highest tested concentration and the other, MS2 bacteriophage, demonstrated a slight non-monotonous decrease in infectivity after exposure to one of the tested CeO2 particles. This allows us to hypothesize, that CeO2 nanoparticles may interact not solely with proteins, but also with other components of the viral envelope, e.g. phospholipids, that are absent in the case of non-enveloped viruses.

Interestingly, even if the two CeO2 nanoparticles exhibited different surface properties, one carrying a positive surface charge and the other negatively charged citrate group on its surface, their antiviral activity was relatively similar. This allows us to suggest that the intrinsic properties of the nanoparticles rather than surface charge or surface functional groups were responsible for the observed antiviral effects. Moreover, our results indicating relatively low antiviral activity of Ce-ions and inexistent toxicity of an inert nanoparticle of SiO2 allow us to conclude that the antiviral activity of nano-CeO2 was not due to the release of ions or specific effects by nanosized materials. Compared with viruses, bacteria showed significantly lower sensitivity towards CeO2 nanoparticles. The maximum decrease in viable counts of Escherichia coli bacteria was only 97% while the antibacterial effect was non-monotonous. The Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus was not affected by nano-CeO2 at any of the tested concentrations. Importantly, no cytotoxic effect of nano-CeO2 was observed. On the other hand, Ag nanoparticles that have been considered antiviral in several previous reports, did not show any significant antiviral activity in our study, except for a non-enveloped bacteriophage ф6. However, nano-Ag proved antibacterial and reduced the viable counts of bacteria by more than 99.99% already at low mg/l concentrations. At higher concentrations, nano-Ag exhibited also cytotoxic effects. Thus, based on our results we can conclude that Ag nanoparticles exhibit a relatively unspecific biological effect while nano-CeO2 show a relatively specific antiviral activity. However, a more detailed research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of antiviral action of CeO2 nanoparticles and specific targets of nanoceria in different viruses.

Materials and methods

All chemicals used in the study were of analytical grade. Components of growth media are described in more detail below.

Synthesis of CeO2, Ag and SiO2 nanoparticles

The target materials which antiviral potential was assessed in this study were nanoparticles of ceria that were synthesized using two methods resulting in nano-CeO2 with positive and negative surface zeta potential. The antiviral effects of nano-CeO2 were compared with nanoparticles of silica (nano-SiO2) that were considered biologically inert (negative control) and silver nanoparticles (nano-Ag) that were considered potentially antiviral (positive control). The following chemicals were used for the synthesis of nanoparticles: cerium (III) nitrate hexahydrate (99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich), diammonium cerium (IV) nitrate (98%, Fluka), hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA, analytical grade, Sigma-Aldrich), citric acid (99%, Fluka), sodium citrate dihydrate (98%, Sigma-Aldrich), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 98%, Fluka), 0.1 M water solution of AgNO3 (Fluka, analytical grade), sodium tetrahydridoborate (Sigma Aldrich, reagent grade), ethyl alcohol (analytical grade, Sigma-Aldrich), polyethylene glycol (PEG, Mw 1500, Reagent grade, Sigma Aldrich), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, Mw 10000, Reagent grade, Sigma Aldrich), 30% aqueous ammonia solution (Reagent grade, Sigma Aldrich). All solutions were made with MQ deionized water.

For the synthesis of nano-CeO2(+) nanoparticles the modified technique from Ref.74 was used. Diammonium cerium (IV) nitrate was hydrolyzed at high temperature in the presence of HMTA. For that, 0.189 g of (NH4)2Ce(NO3)6 and 0.053 g of HMTA were dissolved in 50 ml of water and loaded into an autoclave vessel (100 ml). The vessel was sealed and heated to 180 °C for 30 min in the microwave-hydrothermal device (Berghof Speedwave 4, 2.45 GHz, 1000 W). After thermal treatment, the vessel was cooled down to room temperature in a water bath. The product was centrifuged for 10 min, the sediment was washed with deionized water and redispersed by ultrasonication. These steps were repeated at least 3 times and the final product was redispersed in 5 ml of MQ water by ultrasonication until opalescent pale-yellow colloid was obtained. As a result, nanoparticles with an almost “bare” surface carrying positive charge were obtained.

For the synthesis of nano-CeO2(−) nanoparticles we used a method from Ref.75. Cerium(III) nitrate was hydrolyzed at room temperature in the presence of ammonia with simultaneous oxidation by oxygen from the air. For that, 0.045 g of citric acid was dissolved in 25 ml of prepared in advance 0.05 M aqueous solution of cerium (III) nitrate. The solution was rapidly added into 100 ml of 3 M solution of ammonia and left to stir vigorously for 2 h during which the color of solution changed from colorless to yellow-orange. After that the colloid solution was centrifuged, washed and redispersed by ultrasonication. These steps were repeated at least 3 times and the final product was redispersed in 15 ml of MQ water by ultrasonication until transparent dark yellow colloid was obtained. This method allowed the production of ceria nanoparticles stabilized by citrate-ions and therefore carrying a large negative charge.

For synthesis of nano-Ag a two-step seed-mediated technique was used adopted from Ref.76 and modified to avoid toxic reagents. For preparation of seeds 20 ml of 2.5 mM solution of sodium citrate were mixed with 1 ml of 5 g/l aqueous PVP (MW 10000) solution and 1.2 ml of freshly prepared 10 mM solution of NaBH4. To this mixture 20 ml of 0.5 mM solution of silver nitrate was added at the rate of 2 ml/min under constant stirring. The Ag seeds were left to form for 15 min under stirring at room temperature. In the second stage 27 ml of prepared seed solution was added to the solution of 0.5884 g of sodium citrate in 470 ml of MQ water. This mixture was heated up to 85 °C under stirring and when this temperature was reached, 0.625 ml of 0.1 M AgNO3 solution was added to the solution, which was afterwards left under stirring for 15 min. In order to purify and concentrate the obtained solution, ultracentrifugation was performed (Beckman Coulter, Optima XE-90 Ultracentrifuge device, 28,000 rpm/141,000×g, 2.5 h). This allowed us to obtain a solution with 0.13 g/ml concentration. From this stock solution, less concentrated samples were prepared by dilution with MQ water.

Synthesis of nano-SiO2 was carried out using a modified Stöber technique77. For that, 18 ml of MQ water was mixed with 100 ml of ethanol. In this water-alcohol mixture 1.5 g of PEG, 6.2 ml of TEOS and 3 ml of NH4OH solution were dissolved. The resulting reaction mixture was left at room temperature under vigorous stirring for 24 h. After that the synthesized SiO2 was centrifuged, washed with deionized water and redispersed by ultrasonication. These steps were repeated at least 3 times and the final product redispersed in 5 ml of MQ water by ultrasonication until opalescent colorless colloid was obtained.

Characterization of CeO2, SiO2 and Ag nanoparticles

The characteristics of nanoparticles, the size, shape, agglomeration state, size distribution, surface characteristics and solubility, were chosen according to the recommendation by the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks of the European Commission79. Particle size and morphology were studied by means of transmission electronic microscopy (FEI Tecnai F20 TEM). For TEM analysis a drop of, 100 mg/l particle suspension was deposited onto a 400 mesh holey carbon coated copper grid (Agar scientific AGS147-4) and the sample was dried. Particle aggregation potential (hydrodynamic size measurement using dynamic light scattering, DLS) and surface zeta potential measurements were performed using Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZSP from aqueous suspensions of particles at the highest concentration tested in the antiviral assay. In case of nano-CeO2, all concentrations tested in antiviral assay were measured using DLS. The measurements of nano-SiO2 and nano-Ag were carried out using corresponding pre-set parameters of the device; nano-CeO2 measurements were carried out using pre-set parameters for TiO2 nanoparticles as the closest among available. Water was used as a solvent in these measurements to resemble the actual exposure condition in antiviral and bacterial assays.

More detailed surface characteristics of nano-CeO2 were measured using UV–Vis mode (250–800 nm) of Agilent Cary 5000 UV–Vis–NIR device and FTIR spectral analysis mode of Bruker Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer. For the latter, ATR configuration with diamond crystal was used, and mercury cadmium telluride and MCT detectors were used. Data was obtained from the range of 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1. Separation of mother solution for elemental analysis was performed using ultracentrifugation (Beckman Coulter, Optima XE-90 Ultracentrifuge device) of colloids at 300,000×g for 2 h. Elemental analysis was performed using ICP-MS spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, 2009).

Toxicity testing of nanoparticles on viral host organisms

Prior to antiviral activity testing, the effects of nanoparticles and other test chemicals were assessed on host organisms of those viruses—cell lines in case of mammalian viruses and bacteria in case of bacteriophages.

Cytotoxicity testing with mammalian cell lines

Cytotoxicity was tested against virus host cell lines were tested (Table 4). Cells were seeded onto 96-well plates and grown in specified medium (Table 1) to reach 70% confluency after which growth medium was removed and 100 μl of the tested compound corresponding to that later tested for antiviral effects was added. The cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, humidified atmosphere after which the medium with the test compounds was removed, fresh growth medium was added and cells were further incubated for 48 h. Cell viability was measured using Cell Proliferation Reagent (WST-1) (Roche) tox which 10 μl/well WST-1 reagent was added, the plate was incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 3 h and absorbance at 450 nm was read. For calculation, the value of a blank well (no cells present) was subtracted from each measurement and the value of wells without a test compound was considered as 100% viability. Three replicates were tested for each compound and concentration. The concentrations of test substances that resulted in cellular toxicity were not tested for their antiviral effects as interferences from cellular toxicity could not be avoided.

Table 4.

Viruses, their host organisms and maintenance conditions.

| Virus | Titer in exposure, PFU/ml | Host organism | Maintenance/growth conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enveloped viruses | |||

| Mammalian viruses | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 5 × 105 | Vero E6 cells (Growth medium: DMEM, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin; grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2) | Virus growth medium: DMEM, 0.2% BSA, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin |

| TGEV | 8.35 × 106 | ST cells (Growth medium: DMEM, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 37 °C 5% CO2) | Virus growth medium: DMEM, 0.2% BSA, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin |

| Influenza virus A/WSN/1933 | 6.65 × 104 | MDCK-2 cells (Growth medium: DMEM, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 37 °C 5% CO2) | Virus growth medium: DMEM, 0.2% BSA, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 1 µg/ml TPCK-treated trypsin |

| Bacteriophages | |||

| ɸ6 | 1 × 107 | Pseudomonas sp. (Growth medium Tryptone Soy Broth TSB: 17 g/l casein peptone, 3 g/l soy peptone, 2.5 g/l glycose, 5 g/l NaCl, 2.5 g/l K2HPO4; 25 °C; for solid medium 15 g/l agar was added) |

Phage maintenance medium: SM buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 50 mM Tris–HCl; pH 7.5 Semisolid TSB top agar used for infection: 7 g/l agar added to TSB |

| Non-enveloped viruses | |||

| Mammalian viruses | |||

| EMCV | 2.5 × 107 | BHK-21 cells (Growth medium: GMEM, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2% TPB, 2% 1 M Hepes (pH 7.2), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 37 °C 5% CO2) | Virus growth medium: GMEM, 0.2% BSA, 2% 1 M Hepes (pH 7.2), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin |

| Bacteriophages | |||

| MS2 | 1 × 107 | Escherichia coli (Growth medium NZCYM broth: 10 g/l casein hydrolysate, 5 g/l NaCl, 1 g/l casamino acids, 5 g/l yeast extract, 2 g/l MgSO4·7H2O, 2 g/l maltose 37 °C; for solid medium 15 g/l agar was added) |

Phage maintenance medium: SM buffer (see above) Semisolid NZCYM top agar used for infection: 7 g/l agar added to NZCYM |

Toxicity to host bacteria

Host bacteria for the two bacteriophages (Table 4) were exposed to the test substances in plaque assay format omitting the bacteriophage. Bacterial lawns were created by mixing overnight culture of Pseudomonas or exponentially grown culture of Escherichia coli with TSB or NZCYM soft agar (Table 4), respectively and poured into Petri dishes as described below under "Bactericidal assays" . 10 μl drops of the specified concentration of test substances (see the tested concentration ranges in Table 2) were pipetted onto the agarized surface. After overnight incubation, bacterial lawn was observed for inhibition zones at the drops of chemicals. None of the nanoparticles or chemicals except nano-Ag resulted in inhibition zones. To mitigate nano-Ag toxicity in antiviral assay with bacteriophages these nanoparticles were tested in combination with threefold molar excess of l-cysteine. Thus, in case of 14 μM nano-Ag equal volume of 42 μM l-cysteine was added, in case of 140 μM nano-Ag equal volume of 420 μM l-cysteine was added and in case of 1400 μM equal volume of nano-Ag 4200 μM l-cysteine was added. l-cysteine concentrations till 4200 μM did not decrease the titer of neither of the bacteriophage.

Testing of antiviral activity

The six viruses and bacteriophages used in the tests and media used for their infection and propagation are described in Table 4 and below. Nanoparticles and chemicals used for antiviral testing are shown in Table 2. In general, aqueous suspensions of chemicals at specified concentrations were mixed with an equal amount of bacteriophages in water or with mammalian viruses in 1/10 water-diluted cell culture medium. Samples were incubated for 1 h at room temperature after which these were diluted in tenfold series using SM buffer (bacteriophages) or virus growth medium (mammalian viruses). 1 h incubation was chosen to follow the requirements of European Biocidal Products Regulation requirements for antimicrobial efficacy testing of treated articles.

Mammalian viruses

Viruses (Tables 2, 4) were obtained from the following sources: SARS-CoV-2 was a local Estonian isolate obtained from Estonian Health Board; influenza virus A/WSN/1933 was from SinoBiological; TGEV was obtained from L. Enjuanes at Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, National Center of Biotechnology (CNB-CSIC), Madrid, Spain; EMCV was obtained from A. Kohl MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom. The cell lines for virus propagation (Table 4) were from the cell culture library of Tartu University Institute of Technology, except for ST cells obtained from L. Enjuanes, Madrid, Spain. For propagation of coronaviruses, confluent Vero E6 (for SARS-CoV-2) or ST (for TGEV) cells grown on T75 flask were infected with viral stocks in VGM at a multiplicity of infection 0.01 pfu/cell. Infected cells were incubated for 4 days at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Cell supernatant was collected, clarified by centrifugation at 3000×g for 15 min at + 4 °C, aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C. EMCV stock was obtained ready to use. For propagation of influenza virus A/WSN/1933, confluent MDCK-2 cells grown on T175 flask were infected in VGM containing TPCK-trypsin at final concentration 1 μg/ml. Infected cells were incubated for 2 days at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Cell supernatant was collected, clarified by centrifugation at 4000×g for 10 min at + 4 °C, filtered through a 0.2 μm filter, aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C.

For antiviral activity testing, the viruses with initial titers in virus growth media (Table 4) were diluted 1:10 with sterile water, mixed with the test compound or chemical and incubated as above. After incubation, the virus mixtures were diluted with virus growth medium by 10 times and 150 μl of the resulting sample was used to infect 100% confluent host cells grown on 12- or 96-well plates and washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). In SARS-CoV-2 experiments, 25 μl of the diluted virus sample was used to infect Vero E6 cells. 150 μl or 25 μl of virus growth medium was added to cells in negative control. Infection was carried out at 37 °C, 5% CO2, humidified atmosphere for 1 h with gentle rocking every 10 min. After 1 h, the infection medium was removed and 3:2 mix of virus growth medium: 2% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) was added (in case of influenza virus the mix was supplemented with 1 µg/ml TPCK-trypsin). Cells were grown in respective growth media for 96 h (as an exception 48 h in case of EMCV and Vero E6) at 37 °C, 5% CO2, humidified atmosphere. For plaque counting in ST, MDCK-2 and BHK-21 cells, the virus growth medium was removed, and plates were dyed using crystal violet. Plaques were identified as clear plaques within the cell layer. In Vero E6 cells, mini-plaque method was used for which plates were fixed with ice-cold 80% acetone in 1× PBS at − 20 °C for 1 h. Acetone was then removed by pipetting and the plates were dried for at least 3 h. Dried plates were treated with a blocking buffer (Thermo Scientific, Ref. 37587) diluted in PBS/0.05% Tween20 (PBS-T) for 60 min at 37 °C. Next, the plates were probed with rabbit monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antibody 82C3 (Icosagen AS, ref. nr. R1-166-100) diluted in PBS-T for 1 h at 37 °C. The plates were washed 6 × 5 min with PBS-T and treated with secondary goat anti-rabbit IRDye800CW antibody (LI-COR Biosciences, ref. nr. 926-32211) diluted in blocking buffer for 60 min at 37 °C. Plates were washed with PBS-T 6 × 5 min, dried and scanned using LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey Infrared Imaging System and application software, to identify fluorescent focuses (mini-plaques). Minimum 3 plaques and maximum of 30 plaques per well were counted and PFU value was calculated according to the dilution and the volume of the inoculum. Each concentration of nanoparticles or salt was tested in three replicates and at least three independent experiments were performed.

Antiviral activity was calculated as a difference between log-transformed plaque forming unit (PFU) counts in negative control and the test sample. 2-log decrease in PFU counts during 1 h was considered as the lowest biologically meaningful threshold in potential applications.

Bacteriophages

The enveloped bacteriophage ф6 (DSM21518) and non-enveloped MS2 (DSM21428) and their respective host bacteria, Pseudomonas sp. (DSM21428) and Escherichia coli (DSM5695) were from German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ). Bacteriophages were propagated in their host bacteria and purified in titers shown in Table 4. Bacteriophages in water were exposed to compounds and chemicals as above for 1 h after which SM buffer was used to dilute phages for plaque assay. For infection, 10 μl of bacteriophage samples were dropped as ~ 0.5 cm wide circles onto bacterial plates prepared from overnight grown culture (Pseudomonas sp.) or 2 h grown exponential culture prepared from overnight culture (Escherichia coli). 125 μl of E. coli or Pseudomonas sp. were mixed with 5 ml of semisolid top agar medium (0.7% agar in NZCYM or TSB, respectively at 40 °C and poured onto solid lysogeny broth (LB: 10 g/l tryptone, 5 g/l yeast extract, 10 g/l NaCl) agar plates (1.5% agar) as a thin layer. 10 μl of phage that was incubated in water without compounds as dropped onto bacterial lawns for negative control. Plaques (areas with no visible growth of the host bacterium) within the circles were counted after overnight incubation to obtain the plaque forming units PFU/ml. Minimum of 3 plaques were counted per circle. Each concentration of nanoparticles or chemicals was tested with two technical replicates and at least three independent experiments were performed.

Bactericidal assays

In antibacterial tests Escherichia coli DSM1576 (ATCC8739) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC6538) originating from American Type Culture Collection were used. Nanoparticles and Ce(NO3)3 at specified concentrations were mixed with an equal volume of bacterial suspensions in water. Bacterial suspensions with 1 × 107 CFU/ml were prepared by cultivating the bacteria in their growth media (LB) and subsequent washing with water (5 min centrifugation, resuspension in water and following centrifugation). Bacteria with specified concentrations of nanoparticles and chemicals were incubated for 1 h at room temperature after which the samples were diluted in tenfold series using PBS and drop-plated for viable cell counting (colonies were counted after overnight growth) as in Ref.78. Minimum of 3 colonies were counted per drop. Each condition was tested with two technical replicates and at least three experiments were performed. Antibacterial activity was calculated as a difference between log-transformed colony forming units (CFU) in negative control and the test sample.

ELISA assay to assess receptor binding of SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of nano-CeO2

Binding of nano-CeO2 particles to virus surface proteins was analyzed using SARS-CoV-2 and its cellular receptor human recombinant ACE2-hFc. Maxisorp (Nunc) ELISA plates were covered with ACE2-hFc (product P-308-100, Icosagen, Estonia) in PBS at 1 μg/well, and incubated at + 4 °C overnight. The plate was washed with PBS-T (phosphate-buffered saline with addition of 0.05% Tween20) 5 × 5 min, blocked with 3% BSA/PBS at + 4 °C overnight and then washed with PBS-T. 10 μl of nano-CeO2(+) and (−) at varying concentrations was mixed with 10 μl (5 × 104 PFU, i.e., 5 × 105 PFU/ml) of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 (rescued from infectious clone constructed at the Tartu University Institute of Technology; contains mutations in SARS-CoV-2 S-protein from South African isolate). Mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. 4 μl of virus-nanoparticle mixture was diluted 25 times and transferred to the plate coated with recombinant hACE2 receptor. The plate was incubated at 37 °C overnight, fixed with ice-cold 80% acetone/PBS at − 20 °C for 1 h. Acetone was removed and the plate dried for 1 h. After that blocking with 3% BSA/PBS was carried out at + 37 °C for 1 h. Primary antibody, rabbit monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV2 RBD 72A5 B12 (R1-172-100 Icosagen, Estonia) was diluted in 3% BSA/PBS-T 1:5000 and placed onto the ELISA plate at + 4 °C overnight. Then, the plate was washed with PBS-T 5 × 5 min and incubated with secondary antibody, anti-rabbit-HRP (horseradish peroxidase conjugate, LabAS, Tartu, Estonia) diluted 1:10,000 in 3% BSA/PBS-T at + 37 °C for 1 h. The plate was then washed with PBS-T 5 × 5 min and 50 μl/well of 3,3ʹ,5,5ʹ-Tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Bio-Rad) was added, the wells were incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl/well of 0.5 M H2SO4. Absorbance at 450 nm was quantified using a microplate reader. Wells non-treated with hACE2 were used as negative control.

Statistical analysis

Log-transformed data was used for the analysis of PFU or CFU counts. Two-way ANOVA analysis followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test to detect significant differences from control and corrected for multiple comparisons at 0.05 significance level was executed in GraphPad Prism 9.3.0. Only statistically significant differences are marked in Table 3.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

A.I. was responsible for securing the funding, designing the study and writing the manuscript, A.N. was responsible for nanoparticles synthesis and characterization, DLS analysis, writing and editing the manuscript, K.R. was responsible for most of the antiviral tests and cytotoxicity assays as well as editing the manuscript, E.Z. was responsible for antiviral testing with SARS-CoV-2 and ELISA assays as well as for writing and editing the manuscript, A.V. was responsible for nanoparticles synthesis and characterization and writing the manuscript, M.R. was responsible for designing bacteriophage assays, carried out antibacterial tests and performed statistical analysis of the data, K.K. performed tests with bacteriophages and analyzed the data, S.L. participated in nanoparticles synthesis and writing the manuscript, M.V. was responsible for nanoparticles analysis, including EM imaging and elemental analysis, K.S. performed high resolution E.M., V.K. and T.T. participated in manuscript editing.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the Estonian Research Council Grants (COVSG2, PRG629, PRG1496), Estonian Centre of Excellence in Research project “Advanced materials and high-technology devices for sustainable energetics, sensorics and nanoelectronics” TK141 (2014-2020.4.01.15-0011) and University of Tartu Development Fund (PLTFYARENG53). The research was partly conducted using the NAMUR+ core facility funded by projects “Center of nanomaterials technologies and research” (2014-2020.4.01.16-0123) and TT13.

Data availability

The original data are available upon request from the corresponding author: angela.ivask@ut.ee.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Alexandra Nefedova and Kai Rausalu.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-23465-6.

References

- 1.Paintsil E, Cheng Y-C. Antiviral agents. In: Paintsil E, Cheng Y-C, editors. Encyclopedia of Microbiology. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 223–257. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indari O, Jakhmola S, Manivannan E, Jha HC. An update on antiviral therapy against SARS-CoV-2: How far have we come? Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:632677. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.632677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang L, Ahamed A, Ge L, Fu X, Lisak G. Advances in antiviral material development. ChemPlusChem. 2020;85:2105–2128. doi: 10.1002/cplu.202000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L, Liang J. An overview of functional nanoparticles as novel emerging antiviral therapeutic agents. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2020;112:110924. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.110924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vecitis CD. Antiviral-nanoparticle interactions and reactions. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2021;8:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurunathan S, et al. Antiviral potential of nanoparticles—Can nanoparticles fight against coronaviruses? Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1645. doi: 10.3390/nano10091645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rashidzadeh H, et al. Nanotechnology against the novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2): Diagnosis, treatment, therapy and future perspectives. Nanomedicine. 2021;16:497–516. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2020-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yadavalli T, Shukla D. Role of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles as diagnostic and therapeutic tools for highly prevalent viral infections. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2017;13:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maduray K, Parboosing R. Metal nanoparticles: A promising treatment for viral and arboviral infections. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021;199:3159–3176. doi: 10.1007/s12011-020-02414-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milovanovic, M., Arsenijevic, A., Milovanovic, J., Kanjevac, T. & Arsenijevic, N. Nanoparticles in antiviral therapy. In Antimicrobial Nanoarchitectonics, 383–410. 10.1016/B978-0-323-52733-0.00014-8; https://web.archive.org/web/20220126201628/; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323527330000148?via%3Dihub (Elsevier, 2017).

- 11.Strasfeld L, Chou S. Antiviral drug resistance: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2010;24:413–437. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg M, et al. Potential ecotoxicological effects of antimicrobial surface coatings: A literature survey backed up by analysis of market reports. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6315. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salleh A, et al. The potential of silver nanoparticles for antiviral and antibacterial applications: A mechanism of action. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1566. doi: 10.3390/nano10081566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara HH, Ixtepan-Turrent L, Garza-Treviño EN, Rodriguez-Padilla C. PVP-coated silver nanoparticles block the transmission of cell-free and cell-associated HIV-1 in human cervical culture. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara HH, Ayala-Nuñez NV, Ixtepan-Turrent L, Rodriguez-Padilla C. Mode of antiviral action of silver nanoparticles against HIV-1. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun RWY, et al. Silver nanoparticles fabricated in Hepes buffer exhibit cytoprotective activities toward HIV-1 infected cells. Chem. Commun. 2005 doi: 10.1039/b510984a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elechiguerra JL, et al. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with HIV-1. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2005;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szymańska E, et al. Multifunctional tannic acid/silver nanoparticle-based mucoadhesive hydrogel for improved local treatment of HSV infection: In vitro and in vivo studies. IJMS. 2018;19:387. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saadh MJ, et al. Silver nanoparticles with epigallocatechingallate and zinc sulphate significantly inhibits avian influenza A virus H9N2. Microb. Pathog. 2021;158:105071. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castro-Mayorga JL, et al. Antiviral properties of silver nanoparticles against norovirus surrogates and their efficacy in coated polyhydroxyalkanoates systems. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017;79:503–510. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeremiah SS, Miyakawa K, Morita T, Yamaoka Y, Ryo A. Potent antiviral effect of silver nanoparticles on SARS-CoV-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;533:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dung TTN, et al. Silver nanoparticles as potential antiviral agents against African swine fever virus. Mater. Res. Express. 2020;6:1250g9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park S, et al. Antiviral properties of silver nanoparticles on a magnetic hybrid colloid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:2343–2350. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03427-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers JV, Parkinson CV, Choi YW, Speshock JL, Hussain SM. A preliminary assessment of silver nanoparticle inhibition of Monkeypox Virus plaque formation. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2008;3:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinclair TR, et al. Surface chemistry-dependent antiviral activity of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2021;32:365101. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ac03d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilaquinga F, Morey J, Torres M, Seqqat R, de las Piña MN. Silver nanoparticles as a potential treatment against SARS-CoV-2: A review. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2021;13:1707. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalwar K, Shan D. Antimicrobial effect of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and their mechanism—A mini review. Micro Nano Lett. 2018;13:277–280. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferdous Z, Nemmar A. Health impact of silver nanoparticles: A review of the biodistribution and toxicity following various routes of exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:2375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lozovski V, et al. Physical point of view for antiviral effect caused by the interaction between the viruses and nanoparticles. J. Bionanosci. 2012;6:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zholobak NM, et al. Antiviral effect of cerium dioxide nanoparticles stabilized by low-molecular polyacrylic acid. Mikrobiolohichnyi zhurnal (Ukraine) 1993;72:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohamed HEA, et al. Promising antiviral, antimicrobial and therapeutic properties of green nanoceria. Nanomedicine. 2020;15:467–488. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2019-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dutta P, et al. Concentration of Ce3+ and oxygen vacancies in cerium oxide nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2006;18:5144–5146. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyu P, et al. Self-driven reactive oxygen species generation via interfacial oxygen vacancies on carbon-coated TiO2–x with versatile applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:2033–2043. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c19414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, et al. Regulation of Ce (III)/Ce (IV) ratio of cerium oxide for antibacterial application. iScience. 2021;24:102226. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia T, et al. Comparison of the mechanism of toxicity of zinc oxide and cerium oxide nanoparticles based on dissolution and oxidative stress properties. ACS Nano. 2008;2:2121–2134. doi: 10.1021/nn800511k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Celardo I, et al. Ce3+ ions determine redox-dependent anti-apoptotic effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4537–4549. doi: 10.1021/nn200126a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hijaz M, et al. Folic acid tagged nanoceria as a novel therapeutic agent in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:220. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon HJ, et al. Ceria nanoparticle systems for selective scavenging of mitochondrial, intracellular, and extracellular reactive oxygen species in Parkinson’s disease. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:9408–9412. doi: 10.1002/anie.201805052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Zhang M, Song H, Yu C. Silica-based nanoparticles for biomedical applications: From nanocarriers to biomodulators. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:1545–1556. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calvache-Muñoz J, Prado FA, Rodríguez-Páez JE. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and tentative mechanism of particle formation. Colloids Surf. A. 2017;529:146–159. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohan JC, Praveen G, Chennazhi KP, Jayakumar R, Nair SV. Functionalised gold nanoparticles for selective induction of in vitro apoptosis among human cancer cell lines. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2013;8:32–45. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plakhova TV, et al. Solubility of nanocrystalline cerium dioxide: Experimental data and thermodynamic modeling. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:22615–22626. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin Q, et al. Sanitizing agents for virus inactivation and disinfection. View. 2020;1:16. doi: 10.1002/viw2.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ISO Standard 21702:2019. Measurement of Antiviral Activity on Plastics and Other Non-porous Surfaces (2019).

- 45.ISO Standard 18184:2019. Textiles—Determination of Antiviral Activity of Textile Products (2019).

- 46.Liu W-C, Lin S-C, Yu Y-L, Chu C-L, Wu S-C. Dendritic cell activation by recombinant hemagglutinin proteins of H1N1 and H5N1 influenza A viruses. J. Virol. 2010;84:12011–12017. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01316-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobs L, de Groot R, van der Zeijst BAM, Horzinek MC, Spaan W. The nucleotide sequence of the peplomer gene of porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV): Comparison with the sequence of the peplomer protein of feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) Virus Res. 1987;8:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(87)90008-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carocci M, Bakkali-Kassimi L. The encephalomyocarditis virus. Virulence. 2012;3:351–367. doi: 10.4161/viru.20573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chao L, Tran TT, Tran TT. The advantage of sex in the RNA virus φ6. Genetics. 1997;147:953–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.3.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shiba T, Suzuki Y. Localization of A protein in the RNA-A protein complex of RNA phage MS2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Nucleic Acids Protein Synth. 1981;654:249–255. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(81)90179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitworth C, et al. Persistence of bacteriophage Phi 6 on porous and nonporous surfaces and the potential for its use as an ebola virus or coronavirus surrogate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020;86:20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01482-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Carvalho NA, Stachler EN, Cimabue N, Bibby K. Evaluation of Phi6 persistence and suitability as an enveloped virus surrogate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:8692–8700. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b01296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fedorenko A, Grinberg M, Orevi T, Kashtan N. Survival of the enveloped bacteriophage Phi6 (a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2) in evaporated saliva microdroplets deposited on glass surfaces. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:22419. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79625-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.D’Souza DH, Su X. Efficacy of chemical treatments against murine norovirus, feline calicivirus, and MS2 bacteriophage. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2010;7:319–326. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim J, et al. Non-monotonic concentration–response relationship of TiO2 nanoparticles in freshwater cladocerans under environmentally relevant UV-A light. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014;101:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klanjšček T, Muller EB, Holden PA, Nisbet RM. Host–symbiont interaction model explains non-monotonic response of soybean growth and seed production to nano-CeO2 exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:4944–4950. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b06618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gusseme BD, et al. Virus removal by biogenic cerium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:6350–6356. doi: 10.1021/es100100p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neal CJ, et al. Metal-mediated nanoscale cerium oxide inactivates human coronavirus and rhinovirus by surface disruption. ACS Nano. 2021;15:14544–14556. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c04142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.FDA Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 21 CFR Part 582.

- 60.FDA Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 21 CFR Part 184.

- 61.Agnihothram SS, et al. Silicon dioxide impedes antiviral response and causes genotoxic insult during calicivirus replication. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016;16:7720–7730. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2016.12828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galdiero S, et al. Antiviral activity of mycosynthesized silver nanoparticles against herpes simplex virus and human parainfluenza virus type 3. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013 doi: 10.2147/ijn.s50070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mori Y, et al. Antiviral activity of silver nanoparticle/chitosan composites against H1N1 influenza A virus. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013;8:93. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-8-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.European Chemicals Agency . Guidance on the Biocidal Products Regulation. Volume II, Efficacy. Assessment and Evaluation (Parts B+C) Publications Office; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qi M, et al. Cerium and its oxidant-based nanomaterials for antibacterial applications: A state-of-the-art review. Front. Mater. 2020;7:213. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoecke KV, et al. Fate and effects of CeO2 nanoparticles in aquatic ecotoxicity tests. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:4537–4546. doi: 10.1021/es9002444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Link N, Brunner TJ, Dreesen IAJ, Stark WJ, Fussenegger M. Inorganic nanoparticles for transfection of mammalian cells and removal of viruses from aqueous solutions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007;98:1083–1093. doi: 10.1002/bit.21525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Farias IAP, dos Santos CCL, Sampaio FC. Antimicrobial activity of cerium oxide nanoparticles on opportunistic microorganisms: A systematic review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018;2018:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2018/1923606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Masadeh MM, et al. Cerium oxide and iron oxide nanoparticles abolish the antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin against gram positive and gram negative biofilm bacteria. Cytotechnology. 2015;67:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s10616-014-9701-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ravikumar S, Gokulakrishnan R, Boomi P. In vitro antibacterial activity of the metal oxide nanoparticles against urinary tract infectious bacterial pathogens. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2012;2:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cuahtecontzi-Delint R, et al. Enhanced antibacterial activity of CeO2 nanoparticles by surfactants. Int. J. Chem. Reactor Eng. 2013;11:781–785. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thill A, et al. Cytotoxicity of CeO2 nanoparticles for Escherichia coli. Physico-chemical insight of the cytotoxicity mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40:6151–6156. doi: 10.1021/es060999b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Slavin YN, Asnis J, Häfeli UO, Bach H. Metal nanoparticles: Understanding the mechanisms behind antibacterial activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017;15:65. doi: 10.1186/s12951-017-0308-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xie A, et al. Rapid hydrothermal synthesis of CeO2 nanoparticles with (220)-dominated surface and its CO catalytic performance. Mater. Res. Bull. 2015;62:148–152. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Popov AL, et al. Radioprotective effects of ultra-small citrate-stabilized cerium oxide nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo. RSC Adv. 2016;6:106141–106149. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aherne D, Ledwith DM, Gara M, Kelly JM. Optical properties and growth aspects of silver nanoprisms produced by a highly reproducible and rapid synthesis at room temperature: Silver nanoprisms from rapid, reproducible, room-temperature synthesis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008;18:2005–2016. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guo Q, et al. Synthesis of disperse amorphous SiO2 nanoparticles via sol–gel process. Ceram. Int. 2017;43:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miles AA, Misra SS, Irwin JO. The estimation of the bactericidal power of the blood. Epidemiol. Infect. 1938;38:732–749. doi: 10.1017/s002217240001158x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.SCENIHR (Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks of the European Commission)—Opinion on the Appropriateness of Existing Methodologies to Assess the Potential Risks Associated with Engineered and Adventitious Products of Nanotechnologies. Adopted by the SCENIHR During the 7th Plenary Meeting of 28–29 SEPTEMBER 2005 (2005).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original data are available upon request from the corresponding author: angela.ivask@ut.ee.