Abstract

People feel lonely when their social needs are not met by the quantity and quality of their social relationships. Most research has focused on individual-level predictors of loneliness. However, macro-level factors related to historical time and geographic space might influence loneliness through their effects on individual-level predictors. In this Review, we summarize empirical findings on differences in the prevalence of loneliness across historical time and geographical space and discuss four groups of macro-level factors that might account for these differences: values and norms, family and social lives, technology and digitalization, and living conditions and availability of individual resources. Regarding historical time, media reports convey that loneliness is on the rise, but the empirical evidence is mixed, at least before the COVID-19 pandemic. Regarding geographical space, national differences in loneliness are linked to differences in cultural values (such as individualism) but might also be due to differences in the sociodemographic composition of the population. Research on within-country differences in loneliness is scarce but suggests an influence of neighbourhood characteristics. We conclude that a more nuanced understanding of the effects of macro-level factors on loneliness is necessary because of their relevance for public policy and propose specific directions for future research.

Subject terms: Psychology, Psychology

People feel lonely when their social needs are not met, which can lead to long-term health issues. In this Review, Luhmann et al. summarize empirical findings on differences in the prevalence of loneliness across time and space and consider macro-level factors that might account for these differences.

Introduction

People experience loneliness when they feel that their social relationships are deficient in terms of quantity or quality and perceive a gap between their actual and desired relationships1. Around the world, people describe loneliness as a painful, sometimes agonizing, experience2. Loneliness is conceptually distinct from being alone (a momentary state of objective absence of other people), solitude (when being alone is perceived as pleasant and sought out intentionally)3 and social isolation1,3–5 (the objective lack of social relationships and social contact1).

Through its adverse effects on sleep, immune functioning and health behaviours, loneliness can lead to long-term health issues such as an increased risk for cardiovascular diseases and reduced longevity1,6–9. The health-related consequences of loneliness are detrimental for individual well-being and come with substantial economic costs for society10,11. Loneliness has therefore been recognized as a public health issue that needs to be addressed by public policy12,13. Indeed, loneliness is on political agendas in the United Kingdom14, Germany15, Japan16 and the European Union17. Thus, loneliness has important societal implications, and there is a need for evidence-based recommendations for public policy.

Despite these societal implications, loneliness is a deeply subjective experience and almost all empirically established predictors of loneliness refer to characteristics of the person (Table 1). Loneliness is more common among individuals with low socioeconomic status18,19 and poor health19,20, two individual factors that limit people’s opportunities to participate in everyday social activities. Because poor health is particularly common among the elderly, old age is sometimes considered a critical risk factor for loneliness. However, although studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic found that average loneliness was highest in the oldest age group (80 years and older)18,21–23, increased loneliness has also been reported in younger age groups18,24, and a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found no significant relationship between age and loneliness25. Identifying with a group that is marginalized within a society (for example, ethnic/racial26,27 or sexual orientation/identity28–31 minority groups) is associated with higher average levels of loneliness, presumably because these groups are more likely to experience stressors such as discrimination or rejection, which increase the risk of loneliness29–33. Loneliness is also correlated with personality traits. Individuals high in extraversion and emotional stability are less prone to loneliness than individuals low on these traits34. Finally, the characteristics of one’s social relationships are among the most proximal predictors of loneliness. Having a romantic partner, a large social network, frequent social interactions, and high-quality relationships decrease the risk of loneliness19,20,35,36.

Table 1.

Individual-level predictors of loneliness

| Predictor | Key findings | Exemplary studies | Study description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personality traits |

Extraversion and emotional stability are linked to a lower risk for loneliness. Extraverted people are more likely than introverted people to seek out social interactions and to make friends. Emotionally stable people are less likely than emotionally unstable people to experience being alone as adverse. |

Buecker et al. (2020)34 | Meta-analysis (N = 93,668 individuals, k = 1,697 effect sizes) of relations between loneliness and Big Five personality traits. |

| Gender |

Empirical findings on gender effects are inconsistent across single studies. Meta-analytic evidence shows that gender differences are small to negligible. |

Maes et al. (2019)160 | Meta-analysis (N = 399,798 individuals, k = 751 effect sizes) of gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan |

| Age |

Old age (80+ years) tends to be associated with a significant increase in loneliness, mostly owing to widowhood, poor health and reduced mobility in this age group. Age is not a risk factor for loneliness itself, as loneliness can be experienced by people of any age, and some risk factors are specific to certain age groups. |

Mund et al. (2020)25 | Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies (N = 83,667 individuals, k = 208 effect sizes) on the development of loneliness across the lifespan |

| Qualter et al. (2015)24 | Theoretical article providing a lifespan perspective on the emergence and development of loneliness | ||

| Luhmann & Hawkley (2016)18 | Nationally representative study from Germany (N = 16,132) on age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to old age | ||

| Socioeconomic status | Being unemployed and having a low income are associated with a greater risk of loneliness because financial resources are often required to participate in everyday social activities. | Cohen-Mansfield et al. (2016)19 | Systematic literature review (k = 38 articles) of correlates and predictors of loneliness in old age |

| Household composition | People living alone tend to feel lonelier, but this effect can mostly be explained by differences in marital status and income. | Luhmann & Hawkley (2016)18 | Nationally representative study from Germany (N = 16,132) describing sociodemographic correlates of loneliness across the lifespan |

| Health | Poor health and functional limitations restrict people’s opportunities to participate in everyday social activities and can therefore lead to social isolation and loneliness. | Cohen-Mansfield et al. (2016)19 | Systematic literature review (k = 38 articles) on correlates and predictors of loneliness in old age. |

| Dahlberg et al. (2022)20 | Systematic literature review (k = 34 articles) on longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in old age. | ||

| Relationship status |

People who are single have a greater risk of loneliness than people in stable relationships, but some people feel lonely despite having a partner. Getting divorced or becoming widowed is associated with immediate and lasting increases in loneliness. |

Cohen-Mansfield et al. (2016)19 | Systematic literature review (k = 38 articles) on correlates and predictors of loneliness in old age. |

| Dahlberg et al. (2022)20 | Systematic literature review (k = 34 articles) on longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in old age. | ||

| Hsieh & Hawkley (2018)161 | Nationally representative study of older adults in the USA (N = 3,005) using data from romantic couples. | ||

| Buecker et al. (2021)49 | Nationally representative longitudinal study from the Netherlands (N = 13,945) on changes in loneliness surrounding different major life events. | ||

| Social isolation | People who have small social networks and few social interactions are more likely to feel lonely, but loneliness (perceived social isolation) and (objective) social isolation are not the same. | Cohen-Mansfield et al. (2016)19 | Systematic literature review (k = 38 articles) on correlates and predictors of loneliness in old age. |

| Dahlberg et al. (2022)20 | Systematic literature review (k = 34 articles) on longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in old age | ||

| Coyle & Dugan (2012)162 | Nationally representative study of older adults in the USA (N = 11,825) on the relations between social isolation, loneliness and health. | ||

| Relationship quality | Having high-quality relationships is one of the most important protective factors for loneliness. | Cohen-Mansfield et al. (2016)19 | Systematic literature review (k = 38 articles) on correlates and predictors of loneliness in old age. |

| Dahlberg et al. (2022)20 | Systematic literature review (k = 34 articles) on longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in old age. |

However, how people think, feel and behave is also shaped by the greater context37, including the sociohistorical context38,39 and the geographical and cultural context40,41. Macro-level factors can influence the distribution of individual-level predictors of loneliness at a given time or in a given location. For example, cultural norms and values, societal welfare and demographic composition explain geographical differences in loneliness through their effects on individual-level predictors such as the quality of living conditions and social integration42. Such indirect pathways are also proposed in theories that focus on loneliness-related outcomes. For example, context factors influence people’s social opportunities, their available time and energy, and their capacity and motivations, all of which influence the extent to which people form and maintain friendships in older age43. Moreover, health outcomes are partly determined by a causal cascade of macro-level factors (such as culture, socioeconomic factors and social change) that influence social networks and psychosocial factors such as loneliness44.

Macro-level factors can also moderate the associations between individual predictors and outcomes. Macro-level factors influence people’s standards for their social relationships (social expectations), which in turn moderate the extent to which other factors such as the level of social integration are related to loneliness42. For example, when macro-level factors restrict people’s opportunities for social interactions (such as during pandemic-related lockdowns), the frequency of daily social contact might be less strongly related to loneliness than when macro-level factors do not influence people’s opportunities for social interactions.

In this Review, we summarize the current evidence on whether and why loneliness varies across time and space. Because historical changes and geographical differences in loneliness have largely been investigated separately, we review these topics in separate sections. For each topic, we first examine whether differences in loneliness across time and space exist in the first place. Next, we discuss macro-level factors that might account for these differences. To that end, we draw on the HIstorical changes in DEvelopmental COntexts (HIDECO) framework39 that organizes macro-level factors into four categories: values and norms, family and social lives, technology and mobility, and individual resources and living conditions. Although this taxonomy was developed to explain historical changes in adult development, the included macro-level factors can, in principle, also vary across geographical regions. HIDECO therefore provides a useful framework to organize our review of macro-level factors related to loneliness. Finally, we discuss policy implications, and provide specific recommendations on directions for future research.

Loneliness across time

Headlines and titles such as “The Loneliness Epidemic” or “The Lonely Century”45 convey that loneliness is more common today than ever before. But, although it is true that variables related to objective social isolation (such as living alone46 and time spent alone47) have increased in the past half-century38,39,48, it is less clear whether loneliness is on the rise as well.

Long-term trends in loneliness

The ideal way to examine long-term trends in loneliness across historical time would be to track large, representative samples across multiple years or even decades. For example, according to the General Social Survey21, average loneliness levels declined from 2014 to 2018, except among young adults, who experienced an increase in loneliness over these 4 years21. Unfortunately, existing long-running panel studies started incorporating standardized loneliness measures only within the past 15 years (since 2008 in the Dutch Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences panel49; since 2013 in the German Socio-Economic Panel18; and since 2014 in the General Social Survey21). Thus, these data cover only short time periods and cannot be used to track longer-term changes in average loneliness levels. Data on loneliness from representative samples from the past century are almost non-existent.

An alternative way to identify long-term trends in loneliness is to examine how average loneliness levels reported in empirical studies change over time. Cross-temporal meta-analyses statistically aggregate mean scale scores of a construct from single studies using samples that are approximately the same age50,51. By examining the correlation between the mean scale scores and the year of data collection, this method enables changes in a construct to be estimated over historical time. Existent cross-temporal meta-analyses on loneliness have been restricted to specific age groups, countries, measurement instruments and/or time periods (Table 2). For young adults (aged <30 years), a meta-analysis focusing on the USA reported decreases in average loneliness52, a meta-analysis focusing on China reported increases in average loneliness53, and a meta-analysis including samples from all over the world found a weak increase in average loneliness that was more pronounced in North American samples and not significantly different from zero in non-North American samples54. A fourth cross-temporal meta-analysis found increasing loneliness levels among older adults (aged >60 years) in China55. Notably, both meta-analyses that focused on Chinese samples found increases in loneliness over time53,55; however, this trend was not replicated in the worldwide meta-analysis examining young adults54, so these findings do not allow any inferences about potential systematic national differences in loneliness trends.

Table 2.

Summary of cross-temporal meta-analyses on historical changes in loneliness levels

| Study | Age group | Country | Loneliness measure | Time period | Loneliness trend | Effect size for mean-level change across the entire time period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buecker et al. (2021)54 | Emerging adults (18–29 years old) | Studies from all continents, but mostly from the USA | Different versions of the UCLA Loneliness Scale163,164 | 1976–2019 |

Significant increase in loneliness only in North American samples, not in European or Asian samples (possibly owing to lack of statistical power). No significant differences in historical changes in loneliness between North American and European and Asian samples. Values have been relatively stable since 2012. |

d = 0.56 |

| Clark et al. (2015)52 | High-school students (Study 1) | USA | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale164 | 1978–2009 | Loneliness declined | d = –0.26 |

| College students (Study 2) | USA | Six items with five response options | 1991–2012 | Loneliness declined | d = –0.11 | |

| Xin & Xin (2016)53 | College students | China | Chinese version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3)163,165 | 2002–2011 | Loneliness increased | d = 0.39 |

| Yan et al. (2014)55 | >60 years old | China | Chinese version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3)163,165 | 1995–2011 | Loneliness increased | d = 1.02 |

Cross-temporal meta-analyses are often the only way to examine changes in a construct over several decades, but they have several limitations. First, existing meta-analyses focus on specific populations and measurement instruments, so it is unclear whether the findings generalize to other age groups and measurement instruments. Second, most of the original studies relied on convenience samples (for example, college students who participated for course credit). Convenience samples are generated using non-probability sampling techniques and are usually not representative of the population of interest (for example, all college students or young adults in general). Specific subgroups might be overrepresented or underrepresented owing to sampling biases. Survey research indicates that response rates have generally been declining over the past five decades56, raising additional concerns that the nature of these sampling biases might change over time. If sampling bias is systematically related to loneliness, estimates of changes in loneliness over time might be biased as well. Thus, cross-temporal meta-analyses allow conclusions to be drawn only about how loneliness changed among people who participated in these kinds of study.

Third, cross-temporal meta-analyses cannot establish the extent to which the observed mean-level trends might be influenced by historical changes in how people respond to questions about loneliness (that is, lack of measurement invariance across time). For example, people might be more likely to admit to feeling lonely frequently in times when loneliness is socially accepted rather than stigmatized54,57. Empirical tests of longitudinal measurement invariance of loneliness scales are rare and typically cover only short time lags58–60 and therefore do not allow inferences about historical changes in response styles. Nevertheless, the impact of longitudinal measurement invariance on the mean-level trends observed in cross-temporal meta-analyses is generally assumed to be small54.

Finally, cross-temporal meta-analyses do not allow conclusions about whether the observed changes are due to the specific historical context (period effects) or due to generational differences (cohort effects). To disentangle period and cohort effects, it is necessary to track loneliness in multiple generations across long periods of time. Even then, possible causes of these effects often remain unclear. Only a few studies have systematically examined generational differences in loneliness, with — again — inconsistent findings (Table 3). Studies from Germany61 and the Netherlands62 reported lower levels of loneliness in later-born cohorts of adults aged 55 years and older. However, most other studies focusing on older European adults did not find any cohort-linked differences in loneliness levels63–66. The findings are similarly diverse in studies of non-European or younger populations. In general, observable differences in loneliness across time can be due to different effects (for example, period effects, cohort effects, or cohort × age interactions), which can only be inferred in specific research designs (for example, in cohort × age designs that enable investigation of cohort differences in age-related changes across multiple historical periods)67,68. Thus, when studies report cohort or period effects, it must be critically examined whether the research design was appropriate to examine these kinds of effect.

Table 3.

Summary of empirical studies investigating generational differences in loneliness

| Study | Design | Age groups | Country | Time period | Summary of results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark et al. (2015)52 | Cross-temporal meta-analysis | Young adults | USA | 1978–2009 | Later-born college students are less lonely than earlier-born college students |

| Longitudinal | Young adults | USA | 1977–2012 | Decline in loneliness in later-born high-school students | |

| Dahlberg et al. (2018)65 | Repeated cross-sectional | Old adults | Sweden |

1992 2002 2004 2011 2014 |

No cohort-linked differences |

| Eloranta et al. (2015)66 | Repeated cross-sectional | Old adults | Finland |

1991 2011 |

No cohort-linked differences |

| Hawkley et al. (2022)21 | Repeated cross-sectional | Young adults, old adults | USA |

2014 2018 |

Increase in loneliness in younger age groups; decrease in older age groups |

| Hawkley et al. (2019)166 | Data from two longitudinal studies with refreshment samples | Middle-aged to old adults | USA |

Data 1: 2005–2006 2010–2011 2015–2016 Data 2: 2006–2016 |

No cohort-linked differences |

| Hülür et al. (2016)61 | Case-matched repeated cross-sectional design | Old adults | Germany |

1990–1993 2013–2014 |

Lower levels of loneliness in the later-born cohort than in the earlier-born cohort |

| Nyqvist et al. (2017)64 | Population-based cohort study with refreshment samples | Old adults | Sweden |

2000–2002 2005–2007 2010–2012 |

No cohort-linked differences |

| Suanet & van Tilburg (2019)62 | Longitudinal with refreshment samples | Middle-aged to old adults | Netherlands | 1992–2016 | Later-born cohorts were less lonely than earlier-born cohorts |

| Trzesniewski & Donnellan (2010)167 | Repeated cross-sectional | Young adults | USA | 1976–2006 | No cohort-linked differences |

| van Tilburg et al. (2015)79 | Cross-sectional | Middle-aged adults | Netherlands |

1992 2002 2012 |

Less loneliness in divorcées in later-born cohorts than in earlier-born cohorts |

| Victor et al. (2002)63 | Cross-sectional | Old adults | England | 1945–1960, 1999 | No cohort-linked differences |

Young adults include college and high school students or samples with a mean age below 31 years; middle-aged adults include samples aged 31–59 years; old adults include samples aged 60 years and older. The age group classification was based on the age information provided in the article.

Despite these limitations, cross-temporal meta-analyses currently represent the best available estimates of changes in loneliness over historical time. However, their findings are inconsistent and therefore do not support sweeping claims of a global loneliness epidemic. More methodologically robust research on historical changes in loneliness in diverse populations is needed.

Relevant macro-level factors

One reason the popular narrative that loneliness is on the rise persists despite a lack of clear empirical evidence might be that many societies have been experiencing major changes in macro-level factors (described below) that influence how people form and maintain social relationships48. It is plausible that these changes inform people’s intuitions about whether loneliness is becoming more common.

Values and norms

Cultural values are constantly changing39. For example, individualism (viewing individuals as self-directed, autonomous and separate from others69) is on the rise across the world69, and is associated with an increased focus on self-development and a devaluation of traditional family ties70. On the surface, the devaluation of family relationships might pose a risk for increased loneliness because the quantity and quality of family relationships might suffer when people are less invested in them. However, individualism does not devalue social relationships in general but rather is defined by a shift in the importance of different types of relationship69. For example, relationships with friends are gaining importance relative to relationships with biological family members69, and the concept of ‘family’ is becoming more inclusive and less bound to biological relationships71. Thus, it is not clear that rising individualism increases the risk for loneliness in a population.

Another cultural value with potential implications for loneliness is materialism. Materialism refers to the importance people place on money and materialistic possessions and acquisitions72. Materialism is correlated with negative outcomes such as poor well-being73 and increased loneliness72. A population-wide increase in materialistic values might therefore lead to an increase in loneliness. Such an increase has been found in the USA74,75, but a study using representative data from the Netherlands found the opposite pattern72. Thus, increasing materialism might contribute to rising loneliness levels in some countries.

Historical periods are also characterized by the political values and attitudes that are dominant at the time. One way in which the contemporary political climate might contribute to loneliness on a societal level is through its implications for marginalized groups who might be less likely to experience personal and institutional discrimination (both risk factors for loneliness30,32,33) in more progressive periods than in more conservative political periods76,77.

Family and social lives

Many societies have experienced shifts in social norms related to family relationships and household structures: people get married less frequently and at an older average age, and are more likely to get divorced and to live alone or in non-traditional family constellations39,71. Living with others and being married is generally associated with a lower risk of loneliness20,35, so an increase in the number of people who live alone or are unmarried might increase loneliness in a population. However, this effect might be counteracted by the changing social norms themselves, such that living alone or being unmarried might matter less in generations or historical periods in which marital norms are less strict. Supporting this view, a study conducted among German adults (aged 40–85 years) found that partnership status was less strongly associated with loneliness among younger birth cohorts (in which social norms for partnerships were more liberal) than among older birth cohorts (in which social norms for partnerships were more conservative)78. Similarly, a study among Dutch adults found that loneliness levels among divorcées decreased from 1992 to 2012, presumably because divorces became more common and therefore more accepted over this timeframe79.

Technology and mobility

The wide distribution of smartphones and the rise of social media have substantially changed how people interact in daily life80. The impact of digitalization on loneliness and other indicators of well-being is a highly active research area and the results are complex81–84. Overall, the link between the digitalization of social interactions and loneliness seems weak (average r = 0.04 in a meta-analysis85 of 139 effect sizes)81,86. Moreover, the causal direction of the association is unclear: whereas some studies suggest that using smartphones and social media lead to higher levels of loneliness, others suggest that loneliness leads to more frequent smartphone use81.

Many countries have also experienced increased residential mobility, both within countries (for example, work-related residential mobility)87 and between countries (for example, voluntary or forced migration)88. Climate change is an additional cause of global residential mobility that will become more important in the coming decades89. Residential mobility has disruptive effects on people’s social networks90,91. In the face of a residential transition, people often anticipate92 and experience loneliness93–95, but they might also be motivated to expand their social networks96. The extent to which residential mobility contributes to loneliness and social isolation therefore depends on how successful people are at forming new and maintaining old social networks97.

Individual resources and living conditions

Macroeconomic indicators such as poverty rates or unemployment rates reflect the distribution of low income and unemployment in a population, two factors that increase the risk for loneliness18,19. Hence, changes in these kinds of macro-level factor might be correlated with changes in loneliness levels in a population because the macro-level factors mirror the prevalence of individual-level risk factors.

The authors of the HIDECO framework assume that individual resources are generally more widely available today than in the past39. However, this does not imply that loneliness is less prevalent today than in the past. For example, medical advances have improved disease prevention and treatment, leading to an increase in life expectancy in most countries98,99. However, in the USA the prevalence of diseases has also increased, indicating that medical advances have not led to a healthier population in the USA overall98. On the individual level, this means that, all else being equal, an individual person suffering from a serious disease in the USA today is more likely to survive, to experience a higher quality of life (including an active social life), and hence less likely to be lonely than in the past. But this positive effect on the individual level does not necessarily translate to a reduction in loneliness prevalence on the population level because the relative proportion of people with health issues in the total population has increased.

This complex association between changes in macro-level factors and loneliness can also be found for the link between historical changes in the demographic composition of a population and loneliness. In most countries, the combined effects of higher longevity and lower fertility rates increase the proportion of older adults in the total population100. Many studies have identified older adults as a central risk group for loneliness, presumably because of a higher prevalence of risk factors such as widowhood and functional limitations in this age group18,21,101. A growing proportion of older adults in a population can therefore be associated with increased average loneliness levels, but this effect could be counteracted by older adults having more opportunities for social interactions with peers42,101.

In sum, there are a number of macro-level factors for which links to loneliness are theoretically plausible. However, these links are complex and mediated through multiple pathways. Thus, they are not always evident when examining simple correlations between changes in macro-level factors and changes in loneliness across time. In addition, correlations among time trends are often spurious102, making it methodologically challenging to establish true causal links between historical changes.

Loneliness across space

The potential relevance of macro-level factors for loneliness can also be gauged by examining how and why loneliness varies across geographical space, both between and within countries.

Cross-national differences

Similar to studies on long-term historical trends, studies examining cross-national differences in loneliness should be based on large, nationally representative samples from multiple countries that all use the same loneliness measure. Most comparative studies that fulfill these criteria focus on European countries (Table 4). These studies consistently find that loneliness levels are lowest in northern and western European countries and substantially higher in southern and eastern European and other former Soviet countries103–107, although there is also substantial variation within these regions108. For example, in one study examining a representative sample of adults aged 65 years and older in 11 western European countries, the proportion of respondents who reported feeling lonely ‘most of the time’ was more than four times as high in Italy and Greece (>25%) than in Denmark and Switzerland (≤6%)104. Similar patterns were found in a meta-analysis that examined loneliness across 113 countries107.

Table 4.

Summary of empirical studies investigating cross-national differences in loneliness

| Study | Sample size | Sample age | Included countries | Loneliness measure | Time period (dataset used, if applicable) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenijevic & Groot (2018)168 | Not reported | >50 years | 10 European countries | One item (“How often did you feel lonely during the last 12 months?”) with three response options | 2004–2013 (SHARE)169 | Lowest prevalence of loneliness in the Netherlands (6.5%), highest prevalence of loneliness in Italy (15.4%) in 2004. Lowest prevalence of loneliness in Denmark (10.0%), highest prevalence of loneliness in Italy (33.4%) in 2013. Loneliness increased across time in all countries. |

| Beller & Wagner (2020)170 | 40,797 | >50 years | 13 European countries and Israel | 3-Item UCLA Loneliness Scale171 with three response options | 2013 and 2017 (SHARE)169 | Stronger effects of loneliness on most health outcomes in less individualistic countries than in more individualistic countries. |

| Domènech-Abella et al. (2018)172 | 7,966 | >65 years | Finland, Poland, Spain | 3-Item UCLA Loneliness Scale171 with three response options | 2011–2012 (COURAGE in Europe)173 | Higher prevalence of loneliness in Poland and Spain than in Finland |

| Fokkema et al. (2012)123 | 12,248 | >50 years | 14 European countries | One item with two response options from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale174 | 2006–2007 (SHARE)169 | Higher prevalence of loneliness in southern and central than in northern and western Europe. Being unmarried, economic deprivation and poor health were predictors of loneliness in southern and central Europe. Social participation as well as frequent contact with and providing support for close relatives prevents and alleviates loneliness in most European countries. |

| Hansen & Slagsvold (2016)103 | 33,832 | 60–80 years | 11 European countries | Six-item version of the de Jong Gierveld Scale175 with three response options | 2004–2011 (Generations and Gender Survey176) | Higher prevalence of loneliness in eastern than in western or northern Europe. Loneliness is predicted by health, partnership and socioeconomic status. |

| Lykes & Kemmelmeier (2014)117 | 3,902 | >60 years | 12 European countries | One item (“Do you feel lonely often, occasionally, or never?”) with three response options | 1992 (Eurobarometer177) | Higher loneliness in collectivistic than in individualistic societies. Absence of interaction with family members is more strongly associated with loneliness in collectivistic societies than in individualistic societies. Absence of a confidant and interaction with friends is more strongly associated with loneliness in individualistic societies than in collectivistic societies. |

| 38,867 | >14 years | 22 European countries | One item (“How much of the time during the past week you felt lonely?”) with four response options | 2006 (European Social Survey178) | ||

| Sauter et al. (2020)179 | 76,982 | 13–17 years | 25 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean | One item with five response options: “In the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?” | 2003–2018 (Global School-based Student Health Survey) | Lowest prevalence of loneliness in Costa Rica (6.7%). Highest prevalence of loneliness in Jamaica (19.5%). Higher prevalence of loneliness in girls than in boys. |

| Stickley et al. (2013)108 | 18,000 | >18 years | Nine former Soviet Union countries | One item (“How often do you feel lonely?”) with four response options | 2010–2011 (Health in Times of Transition108) | Cross-national differences in loneliness (often lonely: from 4.4% in Armenia to 17.9% in Moldova). Higher loneliness is associated with being divorced or widowed, and less social support in all countries. Associations between loneliness and alcohol, tobacco, psychological distress and health differ between countries. |

| Sundström et al. (2009)180 | 8,787 | >65 years | 11 European countries and Israel. | One item (“How often have you experienced the feeling of loneliness over the last week”) with four response options | 2004–2006 (SHARE169) | Higher prevalence of loneliness in Mediterranean countries than in northern Europe. Living with a partner is associated with lower loneliness in all countries. Substantial increase in loneliness when low health and being without a partner are combined. Individual and societal characteristics are linked to loneliness. |

| Swader (2019)125 | 36,760 | >14 years | 21 European countries | One dichotomized item: “How much of the time in the past week [have] you felt lonely?” | 2014 (European Social Survey181) | Higher loneliness in less individualistic countries and in countries with a lower GDP. |

| Vancampfort et al. (2019)182 | 148,045 | 12–15 years | 52 countries |

One item (“During the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?”) with five response options |

2003–2016 (Global School-based Student Health Survey) | After adjusting for age and sex, loneliness was lowest in Laos (2.3%) and highest in Afghanistan (28.5%). Loneliness was similar in countries with different income levels. Sedentary behaviour is associated with loneliness. |

| Vancampfort et al. (2019)183 | 34,129 | >50 years | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, South Africa | One item (“Did you feel lonely for much of the day yesterday?”) with two response options | 2007–2010 (Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health) | Lowest loneliness in China (5.5%), highest loneliness in India (17.8%). People who did not meet recommendations for physical activity were lonelier than those who did meet these recommendations. |

| Vozikaki et al. (2018)104 | 5,074 | >65 years | 11 European countries | One item with four response options from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale174 | 2004–2005 (SHARE169) | Higher prevalence of loneliness in southern than in northern Europe. More frequent loneliness is associated with female gender, older age, a lower socioeconomic status, being partnerless and childless, and not being involved in activities. |

| Yang & Victor (2011)105 | 47,099 | 15–101 years | 25 European countries | One item (“Using this card, please tell me how much of the time during the past week you felt lonely”) with five response options | 2006–2007 (European Social Survey178) | Higher prevalence of loneliness in eastern than in northern Europe. Age has a weaker impact on loneliness than the country of residence. |

| Zoutewelle-Terovan & Liefbroer (2018)106 | 61,082 | 50–85 years | 12 European countries (including Georgia) | Six-item version of the de Jong Gierveld Scale175 | 2004–2009 (Generations and Gender Survey176) | Higher loneliness is associated with being partnerless and childless and other non-normative transitions. There are cross-national differences in the strength of these associations. Childlessness has a stronger effect on loneliness in more traditionalist countries. |

Overall, these studies indicate that loneliness can and does vary across countries. It is possible that these cross-national differences are at least partly driven by methodological factors. For example, survey response rates vary across countries109. Differences in response rates are particularly problematic if survey nonresponse is associated with loneliness. Such a nonresponse bias would directly bias national prevalence estimates. Furthermore, the observed cross-national differences might stem from a different understanding of the concept of loneliness itself. Most cross-national studies use single items such as ‘How often do you feel lonely?’ If the term ‘lonely’ is interpreted differently across nations or languages, the data collected with this measure are not comparable. Indeed, some research suggests that there are cultural differences regarding the meaning of loneliness110, for example, in the extent to which loneliness is about romantic experiences versus broader social approval111. However, qualitative studies examining the meaning of loneliness in different cultures and languages2 and quantitative studies examining the structure and measurement invariance of loneliness measures across cultures112–115 indicate that loneliness is a universal experience that can be measured reliably and validly across cultures.

Beyond these methodological issues, cross-national differences in loneliness can also be due to national differences in macro-level factors. Most research has focused on cultural values, particularly individualism/collectivism, as a macro-level factor that might account for cross-national differences in loneliness. Individualistic cultures value autonomy and self-reliance, whereas collectivistic cultures value being part of and contributing to the ingroup70,116. Hence, individualism/collectivism reflects the value of social relationships and might therefore be particularly relevant for loneliness, but in complex ways111,117,118. On the one hand, loneliness might be more prevalent in individualistic cultures because social ties are looser and people might invest less in their social relationships than in collectivistic cultures. On the other hand, loneliness might be more prevalent in collectivistic cultures because social ties are more important and social relationships might be more likely to be perceived as insufficient. Moreover, people in collectivistic cultures are more likely to perceive the social stigma of loneliness than people in individualistic countries119. The social stigma of loneliness is characterized by the belief that disclosure of being lonely will engender negative responses from others120,121. Because the perceived risk associated with disclosing loneliness is stronger in collectivistic than in individualistic cultures, people in collectivistic countries might be less likely to disclose their feelings of loneliness in surveys or interviews. In addition, tight social relationships are not necessarily indicative of good social relationships, but can be characterized by ingroup vigilance (being aware that others in the ingroup might have bad intentions122) and within-group competition, which are more common in collectivistic than in individualistic cultures122. Cross-national studies suggest that the latter effects trump the former: at least in Europe, loneliness levels are higher in more collectivistic than in more individualistic nations117,123. Cultural values might also moderate the effect of individual-level predictors on loneliness by influencing people’s social expectations, such that people in collectivistic countries might be more likely to take having close friends and living with others for granted than people in individualistic countries42,124. Consistent with this perspective, the protective effect of having a confidant was stronger in individualistic than in collectivistic countries117, whereas the harmful effect of living alone was weaker in individualistic than in collectivistic countries125.

It must be noted that the individualism/collectivism distinction has been criticized as being vaguely defined and lacking explanatory power for many cross-cultural differences126. It is therefore important to consider more precisely defined cultural values as well126. For example, cultural norms related to family and social relationships might contribute to population levels of loneliness via their effects on family and social lives. According to the culture–loneliness framework127, people in cultures with more restrictive norms about social relationships might experience more loneliness because, despite being less physically isolated, they are more likely to experience a discrepancy between their actual and desired social relationships. This notion is consistent with the work on individualism/collectivism discussed above, and with research showing that stronger filial norms (the extent to which adult children are expected to care for their elderly parents) in eastern compared to western European countries might contribute to the higher loneliness levels among older adults in eastern European countries compared to those in western Europe42,123.

Beyond cultural values, national differences in loneliness can also partly be explained by macro-level factors reflecting the sociodemographic composition of a population. For family and social network structures, studies comparing older adults across multiple European countries have found that loneliness levels are higher in countries with higher proportions of older adults living alone and never-married older adults103,123. With respect to individual resources and living conditions, two studies found that loneliness levels were lower in countries with higher average wealth and better average health103,123. Differences in technology and mobility have not yet been systematically examined as correlates of national differences in loneliness, but it has been proposed that higher rates of mobility and migration might be linked to higher national loneliness levels103,107, and there is some evidence that the effect of social media use on psychological outcomes might differ across cultures128.

Overall, these studies show that loneliness varies across nations and that macro-level factors such as values or sociodemographic characteristics account in part for this variability. However, most studies focused on European countries, and only a few macro-level factors have been examined systematically.

Within-country differences

Geographical variation in loneliness can also be found within countries129–134. In a study using a representative German sample, there was a difference greater than two standard deviations between the regions with the highest and lowest loneliness levels131. In another study examining a representative sample of young people (aged 16–24 years) in the UK, geographical region accounted for 5–8% of the total variance in loneliness132. Explanations for within-country differences in loneliness include sociodemographic, physical and perceived neighbourhood characteristics. Under the HIDECO taxonomy, physical and demographic characteristics can best be categorized as individual resource and living conditions factors, whereas perceived neighbourhood characteristics describe the cultural and social aspects of neighborhoods.

Similar to cross-national research, regional differences in loneliness are often explained by differences in the sociodemographic composition of the population. Empirical studies directly examining this link on a within-country level provide mixed results. Some studies find that loneliness levels are elevated in areas with a greater percentage of older low-income adults134 and in socioeconomically deprived areas135, but these associations do not hold up in other studies131,136, suggesting that the effect of the sociodemographic composition of the population on loneliness might depend on other factors to be identified in future research.

A group of macro-level factors unique to within-country studies comprises physical characteristics of places, such as the distinction between urban and rural areas. Multiple studies find no significant differences in average loneliness levels between urban and rural areas after controlling for covariates such as income or age129–131,134–136. Furthermore, related characteristics such as population density are also not associated with loneliness131,136. However, one study found that loneliness levels were higher in areas that were more remote from local centres131. Physical characteristics also encompass neighbourhood characteristics such as general walkability137 and walkable distance to public parks131, which are associated with lower loneliness. Overall, concrete and tangible physical characteristics of places appear to be more relevant to explain differences in loneliness than broad categorizations such as urban versus rural.

Perceived neighbourhood characteristics such as perceived neighbourhood quality (for example, feeling safe at night or perceived attractiveness of buildings) or neighbourhood social capital (for example, perceived reciprocity, trust and civic participation in a neighbourhood) tend to be negatively correlated with loneliness129,132,133,138. However, this effect seems to be limited to self-reports (rather than more objective informant reports) of neighbourhood characteristics136 and does not replicate in all studies139.

In sum, regional and neighbourhood characteristics potentially account for some of the within-country variation in loneliness, but these findings do not always replicate across studies. There are several possible reasons for the lack of replicability. First, the studies have been conducted in different countries (including Australia130, Canada134, Germany131, Hong Kong137 and the UK132,136,138), and it is possible that neighbourhood characteristics vary in their importance across different countries. Second, some studies focused on specific age groups (for example, adolescents and young adults132,136 or older adults130,133,134), whereas others included the entire adult age range131. It is possible that some neighbourhood characteristics are more important for certain age groups than for others. More generally, it is unclear to what extent the association between individual-level predictors of loneliness is moderated by macro-level factors describing regional differences.

Linking macro-level factors to loneliness

Overall, there are many plausible reasons why macro-level factors such as values, family and social network structures, technology, and living conditions might affect population levels of loneliness across time and space. However, for both historical changes and geographical differences, it is often hard to find robust associations between macro-level factors and loneliness.

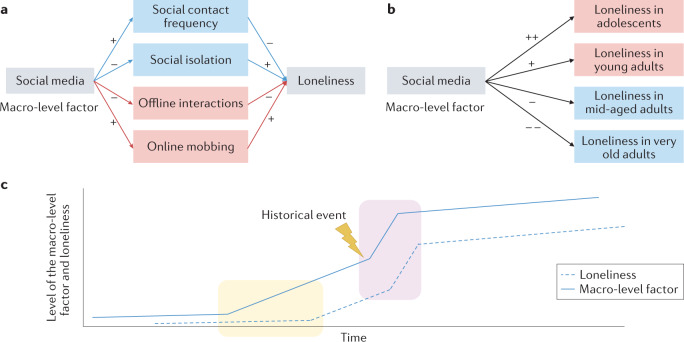

There are multiple possible explanations for this observation. First, most macro-level factors influence social relationships (and, by extension, loneliness) through multiple indirect pathways, some positive and some negative. These positive and negative pathways might counteract each other such that the net effect of specific macro-level factors on loneliness is close to zero (Fig. 1a). For example, social media can lead to more frequent social contact and decrease people’s sense of social isolation (potentially decreasing loneliness), but also displace offline interactions and increase online mobbing and cyber bullying (potentially increasing loneliness). Thus, when combined, the population-level effect of social media on loneliness might be weak81,86.

Fig. 1. Pathways from macro-level factors to loneliness.

a, Macro-level factors might influence loneliness through multiple indirect pathways, some leading to an increase (+) and some leading to a decrease (–) in factors that in turn either increase (+) or decrease (–) loneliness. The direction of the total effect of an indirect pathway is defined by the product of the two direct effects. For example, the indirect pathway involving offline interactions involves two negative effects (social media use reduces offline interactions and engaging in offline interactions reduces loneliness) that together result in a total positive effect (social media use increases loneliness). If positive (blue) and negative (red) pathways are approximately counter-balanced, the overall (net) effect of a macro-level factor is close to zero, even though specific causal effects might exist. b, Macro-level factors might have differential effects on different subgroups within a population. These differential effects might differ in strength and direction such that they lead to increased levels in loneliness in some subgroups (red) and to decreased levels of loneliness in other subgroups (blue). c, Most sociocultural changes occur gradually over time, but sudden changes are possible, for example in the context of historical events. Changes in loneliness might be similarly slow, and they might be delayed such that loneliness changes lag behind changes in macro-level factors. Whether these changes can be linked empirically depends on the time window examined. For example, the yellow time window would reveal no association between changes in the macro-level factor and changes in loneliness levels. By contrast, the purple time window would reveal a strong association between changes in the macro-level factor and changes in loneliness levels.

Second, the strength and even the direction of the effect of a macro-level factor on loneliness might differ among different subgroups (Fig. 1b). In population-level studies, these subgroups are collapsed, so strong effects that exist in only some subgroups might be overlooked. For example, social media use appears to be more beneficial for older adults than for adolescents and young adults81, but this differential association would not be detected if these groups were analysed together.

Third, the effects of most macro-level factors might unfold over long timescales39, so effects on loneliness might be weak, slow and delayed (that is, only detectable after a certain time lag; Fig. 1c). The exact temporal course of these effects is unclear, but it is possible that many macro-level factors require decades to affect population levels of loneliness in an observable way because their effects are weak initially but accumulate over time140.

Implications for policy

A better understanding of how macro-level factors influence loneliness across historical time and geographic space is necessary to develop evidence-based recommendations for public policy measures against loneliness. For researchers, this is an invitation to study these factors more systematically in future research. But loneliness has also become a public policy issue in the past 5 years, and policymakers cannot wait for science to reach some consensus. For those who require guidance now, we offer some tentative policy implications.

First, the impact of macro-level factors should not be overestimated: even on the individual level, the causes of loneliness are complex and idiosyncratic. This is probably even more true for the effects of macro-level factors on population levels of loneliness. Attempts to pin some perceived uptick in loneliness to highly specific macro-level factors such as the introduction of smartphones141 are likely to overestimate the relevance of a single factor, at the peril of drawing attention away from other factors that are at least as important. Instead, public policy is probably most effective if it targets individual risk factors such as poverty and unemployment and provides funding for the development and dissemination of individual-level evidence-based interventions against loneliness. Several reviews provide overviews of effective interventions for different target populations142–144.

At the same time, the importance of macro-level factors should not be underestimated. Shifts in macro-level factors such as demographic changes or changes in norms and values can influence the risk of loneliness in a population, albeit through complex and still poorly understood pathways. Geographical differences in the distribution of these macro-level factors can help to identify regions that might be particularly at risk and could serve as model regions for testing specific policies. Macro-level trends can therefore provide some tentative information on whether loneliness might become a greater (or lesser) concern in the future.

Finally, macro-level factors might moderate the effects of individual-level predictors on loneliness42. For example, the protective effect of being married might depend on the social norms related to marriage at a particular time period or in a particular geographical region78. Thus, the efficacy of policies aiming at reducing loneliness by strengthening marriages will vary across historical time and geographical space. This also means that both individual-level and macro-level measures against loneliness have to fit into the greater context. Policies that are applied in different historical or geographical contexts are not necessarily as effective as in the original setting and therefore need to be re-evaluated and, if necessary, adapted.

Summary and future directions

Systematic effects of macro-level factors on loneliness are theoretically plausible but difficult to detect. Macro-level factors tend to have weak effects on individual-level psychological phenomena, particularly if their effects are directly contrasted against individual-level predictors140. However, this does not mean that macro-level factors should be dismissed: the effects of macro-level factors often accumulate over time140, influence individual-level constructs through multiple indirect (sometimes contradicting) pathways, and might have divergent effects on different subgroups.

To achieve a more nuanced and complete picture of the association between macro-level factors and loneliness, it is necessary to broaden the available database. Representative samples are key to drawing valid conclusions about differences in population levels of loneliness across time or space. Representativeness can be restricted unintentionally through methodological factors (such as nonresponse bias56,109) and intentionally (such as by excluding certain subgroups from the population of interest). For example, many panel studies deliberately exclude residents of care homes, yet this group faces substantial risk for loneliness145. Future research must include individuals from groups, regions and countries that have been underrepresented or completely excluded from previous studies.

To study macro-level factors systematically, researchers must routinely collect multilevel data on the social network, neighbourhood and region in which their participants are embedded. Many individual-level predictors can be aggregated at higher levels. For example, the availability of individual resources can be studied at the individual level (for example, how is individual income related to loneliness) as well as at the local, regional and national level (for example, how are local, regional or national poverty rates related to loneliness levels). In addition, future theoretical and empirical work needs to consider genuine macro-level factors, that is, factors that can only be conceptualized and measured at the macro level (for example, the extent to which mental health is prioritized in a health-care system).

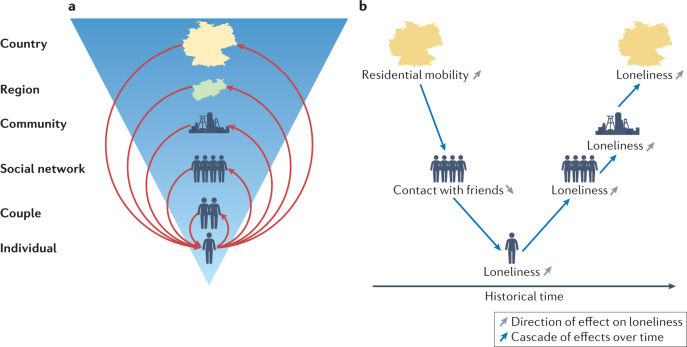

Collecting data repeatedly at regular intervals (for example, annually) over multiple years or even decades would allow systematic investigations into the causal dynamics through which macro-level factors are linked to loneliness. Although most theories and empirical studies treat macro-level factors as predictors of loneliness, the association between macro-level factors and individual-level loneliness is most probably bidirectional (Fig. 2a). The effects of loneliness on individual economic, physical and psychological well-being can translate into population-wide outcomes such as reduced life expectancy6, increased health-care costs10,11, or reduced political participation146. Moreover, trends in macro-level factors might be more relevant than their absolute levels. For example, changes in the demographic composition of a population due to high residential mobility might be more predictive of population loneliness than the demographic composition itself131, owing to a cascade of indirect effects across multiple levels (Fig. 2b). Such a cross-level process takes time to unfold and can only be detected with longitudinal data in which factors at all levels are measured repeatedly over long periods of time.

Fig. 2. Multilevel perspectives on loneliness across historical time.

a, A multilevel perspective on loneliness according to which individuals are embedded in a greater social context (a couple or social network) and greater geographical contexts (local community, such as town or city; broader region, such as county or state; or country). Factors at all higher levels might influence individuals’ loneliness. At the same time, individuals influence higher-level factors directly (for example, through social contagion) and indirectly (for example, by being part of the composition of their respective population). b, Bidirectional associations between macro-level factors and loneliness might be explained by a cascade of cross-level indirect effects that unfold over time. In this example, an increase in residential mobility on the country level is assumed to lead to less contact with friends, which in turn increases individual-level loneliness. This individual-level increase might lead to increased loneliness in their social network (social contagion) and contribute to increased loneliness at the community, regional and country level.

A better understanding of the causal relationships between macro-level factors and loneliness is also necessary to identify causal factors that can be targeted by public policy measures to reduce loneliness147. Examples of research designs that would allow such causal inferences include randomized control trials on community-level or regional-level interventions. In addition, and contrary to conventional wisdom among psychologists, nonexperimental studies can, under specific circumstances and with specific assumptions, be used for causal inference148,149, for example, natural experiments and prospective studies conducted in the context of major historical events147, including wars150, natural disasters151, pandemics151,152 or economic crises153. Indeed, since 2020, researchers have used the COVID-19 pandemic to study the impact of sudden changes in macro-level factors on loneliness152,154–156.

Finally, a broad database fulfilling these criteria would enable integrative investigations of loneliness across both time and space. The association between a macro-level factor and loneliness always has to be understood in its specific geographic and historical context simultaneously, and, as geographic space or historical time change, so might the relevance of a macro-level factor for changes in loneliness across space and time. In addition, the relationships and interactions among different macro-level factors might also vary across time and space. For example, on the individual level, social class is correlated with the size and function of social networks such that individuals of higher socioeconomic classes tend to view themselves as more independent (rather than interdependent), allowing them to form more diverse and loose social networks157. It is possible that similar relationships can be found on the macro level. For example, economic growth could lead to changes in cultural values related to social relationships.

Although there is some overlap between macro-level factors explaining long-term trends in loneliness across historical time and macro-level factors explaining geographical variation in loneliness, few attempts have been made to conceptually or empirically integrate these different perspectives. A recent exception is a spatiotemporal meta-analysis in which historical changes in loneliness among young adults were related to different regional-level characteristics54. In general, spatiotemporal meta-analyses expand classic meta-analytic techniques by using spatial and temporal information (that is, considering not only when but also where an included single study was conducted) to explain heterogeneity in effect sizes158. Although no significant spatiotemporal associations were found in that particular meta-analysis54, this methodological approach might serve as a template for future research examining macro-level factors across time and space simultaneously.

In sum, longitudinal multilevel data from representative samples from multiple countries are necessary to gain a deeper understanding for why loneliness varies across time and space. Collecting such comprehensive data is not feasible for any single laboratory, but with shared resources it is not an impossible goal. In fact, large-scale studies that cover multiple countries across multiple years already exist (for example, the World Happiness Report159), but loneliness is not yet routinely measured in these studies. We therefore call on researchers and funders of large-scale, cross-national panel studies to include standardized measures of loneliness. In addition, we call on researchers around the world to routinely measure loneliness in their studies and thereby contribute to growing the collective database of loneliness across time and space.

Author contributions

All authors researched data for the article. M.L. and S.B. contributed substantially to discussion of the content and wrote the article. All authors reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Johannes Beller, Katherine Fiori and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010;40:218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heu LC, et al. Loneliness across cultures with different levels of social embeddedness: a qualitative study. Pers. Relation. 2021;28:379–405. doi: 10.1111/pere.12367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long CR, Averill JR. Solitude: an exploration of benefits of being alone. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2003;33:21–44. doi: 10.1111/1468-5914.00204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galanaki E. Are children able to distinguish among the concepts of aloneness, loneliness, and solitude? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2004;28:435–443. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goossens L, et al. Loneliness and solitude in adolescence: a confirmatory factor analysis of alternative models. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009;47:890–894. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality. A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015;10:227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkley LC, Capitanio JP. Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: a lifespan approach. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2015 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin SC, Williams AB, Ravyts SG, Mladen SN, Rybarczyk BD. Loneliness and sleep: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Open. 2020;7:2055102920913235. doi: 10.1177/2055102920913235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park C, et al. The effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiat. Res. 2020;294:113514. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kung CSJ, Kunz JS, Shields MA. Economic aspects of loneliness in Australia. Aust. Econ. Rev. 2021;54:147–163. doi: 10.1111/1467-8462.12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mihalopoulos C, et al. The economic costs of loneliness: a review of cost-of-illness and economic evaluation studies. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020;55:823–836. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet. 2018;391:426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt-Lunstad J. The potential public health relevance of social isolation and loneliness: prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2017;27:127–130. doi: 10.1093/ppar/prx030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Government’s work on tackling loneliness. GOV.ukwww.gov.uk/government/collections/governments-work-on-tackling-loneliness (2018).

- 15.CDU/CSU & SPD. Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD. The Bundesregierunghttps://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/koalitionsvertrag-zwischen-cdu-csu-und-spd-195906 (2018).

- 16.Kawaguchi, S. Japan’s ‘minister of loneliness’ in global spotlight as media seek interviews. The Mainichihttps://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20210514/p2a/00m/0na/051000c (2021).

- 17.Baarck, J. et al. Loneliness In The EU. Insights From Surveys And Online Media Data. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/28343 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2021).

- 18.Luhmann M, Hawkley LC. Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Dev. Psychol. 2016;52:943–959. doi: 10.1037/dev0000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen-Mansfield J, Hazan H, Lerman Y, Shalom V. Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults. A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016;28:557–576. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215001532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahlberg L, McKee KJ, Frank A, Naseer M. A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging Ment. Health. 2022;26:225–249. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1876638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkley LC, Buecker S, Kaiser T, Luhmann M. Loneliness from young adulthood to old age: explaining age differences in loneliness. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2022;46:39–49. doi: 10.1177/0165025420971048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Ours JC. What a drag it is getting old? Mental health and loneliness beyond age 50. Appl. Econ. 2021;53:3563–3576. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2021.1883540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicolaisen M, Thorsen K. Who are lonely? Loneliness in different age groups (18–81 years old), using two measures of loneliness. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2014;78:229–257. doi: 10.2190/AG.78.3.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qualter P, et al. Loneliness across the life span. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015;10:250–264. doi: 10.1177/1745691615568999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mund M, Freuding MM, Möbius K, Horn N, Neyer FJ. The stability and change of loneliness across the life span: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2020;24:24–52. doi: 10.1177/1088868319850738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madsen KR, et al. Loneliness and ethnic composition of the school class: a nationally random sample of adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:1350–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasgaard M, Friis K, Shevlin M. “Where are all the lonely people?” A population-based study of high-risk groups across the life span. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiat. Epidemiol. 2016;51:1373–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderssen N, Sivertsen B, Lønning KJ, Malterud K. Life satisfaction and mental health among transgender students in Norway. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:138. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8228-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuyper L, Fokkema T. Loneliness among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: the role of minority stress. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010;39:1171–1180. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes M, et al. Predictors of loneliness among older lesbian and gay people. J. Homosex. 2021 doi: 10.1080/00918369.2021.2005999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buczak-Stec E, König H-H, Hajek A. Sexual orientation and psychosocial factors in terms of loneliness and subjective well-being in later life. Gerontologist. 2022 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Carretta H, Terracciano A. Perceived discrimination and physical, cognitive, and emotional health in older adulthood. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiat. 2015;23:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M, Barreto M, Doyle D. Stigma-based rejection experiences affect trust in others. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2020;11:308–316. doi: 10.1177/1948550619829057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buecker S, Maes M, Denissen JJA, Luhmann M. Loneliness and the Big Five personality traits: a meta–analysis. Eur. J. Pers. 2020;34:8–28. doi: 10.1002/per.2229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinrich LM, Gullone E. The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006;26:695–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawkley LC, et al. From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. J. Gerontol. B. 2008;63:S375–S384. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.S375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology Of Human Development: Experiments By Nature And Design (Harvard Univ. Press, 1979).

- 38.Bühler JL, Nikitin J. Sociohistorical context and adult social development: new directions for 21st century research. Am. Psychol. 2020;75:457–469. doi: 10.1037/amp0000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drewelies J, Huxhold O, Gerstorf D. The role of historical change for adult development and aging: towards a theoretical framework about the how and the why. Psychol. Aging. 2019;34:1021–1039. doi: 10.1037/pag0000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oishi S. Socioecological psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014;65:581–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-030413-152156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rentfrow PJ. Geographical psychology. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020;32:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Jong Gierveld J, Tesch-Römer C. Loneliness in old age in Eastern and Western European societies: theoretical perspectives. Eur. J. Ageing. 2012;9:285–295. doi: 10.1007/s10433-012-0248-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiori KL, Windsor TD, Huxhold O. The increasing importance of friendship in late life: understanding the role of sociohistorical context in social development. Gerontology. 2020;66:286–294. doi: 10.1159/000505547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hertz, N. The Lonely Century: How To Restore Human Connection In A World That’s Pulling Apart (Sceptre, 2021).

- 46.Snell KDM. The rise of living alone and loneliness in history. Soc. Hist. 2017;42:2–28. doi: 10.1080/03071022.2017.1256093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anttila T, Selander K, Oinas T. Disconnected lives: trends in time spent alone in Finland. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020;150:711–730. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02304-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamamura T. Cross-temporal changes in people’s ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020;32:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buecker S, Denissen JJA, Luhmann M. A propensity-score matched study of changes in loneliness surrounding major life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2021;121:669–690. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudolph CW, Costanza DP, Wright C, Zacher H. Cross-temporal meta-analysis: a conceptual and empirical critique. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020;35:733–750. doi: 10.1007/s10869-019-09659-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Twenge JM. The age of anxiety? The birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism, 1952–1993. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000;79:1007–1021. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark DMT, Loxton NJ, Tobin SJ. Declining loneliness over time: evidence from American colleges and high schools. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015;41:78–89. doi: 10.1177/0146167214557007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xin S, Xin Z. Birth cohort changes in Chinese college students’ loneliness and social support. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016;40:398–407. doi: 10.1177/0165025415597547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buecker S, Mund M, Chwastek S, Sostmann M, Luhmann M. Is loneliness in emerging adults increasing over time? A preregistered cross-temporal meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychol. Bull. 2021;147:787–805. doi: 10.1037/bul0000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan Z, Yang X, Wang L, Zhao Y, Yu L. Social change and birth cohort increase in loneliness among Chinese older adults: a cross-temporal meta-analysis, 1995-2011. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:1773–1781. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stedman RC, Connelly NA, Heberlein TA, Decker DJ, Allred SB. The end of the (research) world as we know it? Understanding and coping with declining response rates to mail surveys. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019;32:1139–1154. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2019.1587127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ko SY, Wei M, Rivas J, Tucker JR. Reliability and validity of scores on a measure of stigma of loneliness. Couns. Psychol. 2022;50:96–122. doi: 10.1177/00110000211048000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Penning MJ, Liu G, Chou PHB. Measuring loneliness among middle-aged and older adults: the UCLA and de Jong Gierveld loneliness scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014;118:1147–1166. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0461-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Danneel S, Maes M, Vanhalst J, Bijttebier P, Goossens L. Developmental change in loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018;47:148–161. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.von Soest T, Luhmann M, Gerstorf D. The development of loneliness through adolescence and young adulthood: its nature, correlates, and midlife outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 2020;56:1919–1934. doi: 10.1037/dev0001102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]