Abstract

Since 2005, GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists (GLP-1RAs) have been developed as therapeutic agents for type 2 diabetes (T2D). GLP-1R is not only expressed in pancreatic islets but also other organs, especially the lung. However, controversy on extra-pancreatic GLP-1R expression still needs to be further resolved, utilizing different tools including the use of more reliable GLP-1R antibodies in immune-staining and co-immune-staining. Extra-pancreatic expression of GLP-1R has triggered extensive investigations on extra-pancreatic functions of GLP-1RAs, aiming to repurpose them into therapeutic agents for other disorders. Extensive studies have demonstrated promising anti-inflammatory features of GLP-1RAs. Whether those features are directly mediated by GLP-1R expressed in immune cells also remains controversial. Following a brief review on GLP-1 as an incretin hormone and the development of GLP-1RAs as therapeutic agents for T2D, we have summarized our current understanding of the anti-inflammatory features of GLP-1RAs and commented on the controversy on extra-pancreatic GLP-1R expression. The main part of this review is a literature discussion on GLP-1RA utilization in animal models with chronic airway diseases and acute lung injuries, including studies on the combined use of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) based therapy. This is followed by a brief summary.

Key words: Anti-inflammation, Exenatide, GLP-1R, GLP-1RAs, Liraglutide, Lung injury, MSC-based therapy, TxNIP

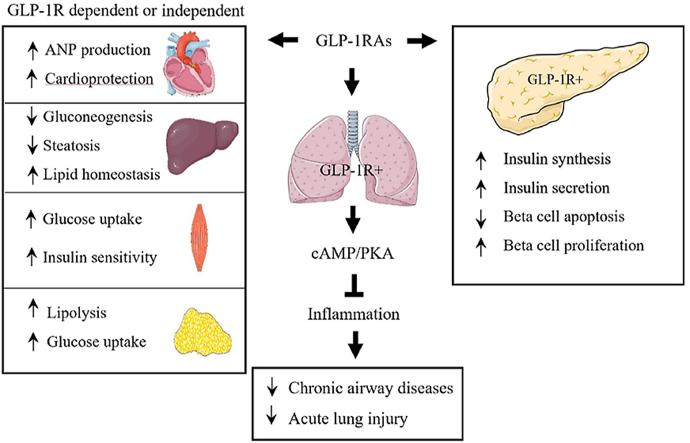

Graphical abstract

T2D drugs known as GLP-1RAs can target GLP-1R which is abundantly expressed in the lung, making them strong candidates as repurposed drugs for chronic airway disorders and acute lung injury.

1. Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone produced in gut endocrine L cells1, 2, 3, 4. Postprandial GLP-1 secretion leads to reduced plasma glucose levels by mechanisms including the stimulation of insulin secretion, the inhibition of glucagon release, as well as the delay of gastric emptying4. Furthermore, plasma GLP-1 elevation or GLP-1-based drug administration may directly reduce food intake, involving their function in the brain, mediated by GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R), which is known to be expressed in the brain hypothalamus and elsewhere5, 6, 7. Various GLP-1-based drugs (also known as GLP-1R agonists, GLP-1RAs) have been developed and approved by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency, or other authorities for diabetes treatment since 20058. They are now widely utilized in treating type 2 diabetes (T2D) without side effects of weight gain and hypoglycemia, compared with various sources of commercial insulin9. GLP-1-based drugs, such as liraglutide (commercially known as Victoza®) and semaglutide (Ozempic®) were also approved by FDA for chronic weight management in patients with obesity, overweight, or weight related comorbid conditions.

Studies on native GLP-1 and GLP-1-based drugs in animal models or in treating patients with T2D have also uncovered their profound anti-inflammatory function10,11. Since inflammatory responses also play important roles in the development and progression of diseases other than T2D, repurposing GLP-1-based drugs has been attracting researchers’ attention in various fields.

In this review, we will briefly summarize the discovery of GLP-1 as an incretin hormone and the development of GLP-1-based diabetes drugs. We will then discuss literature that leads to the recognition of the anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory functions of GLP-1 and its based drugs. This will be followed by a brief discussion of controversies on GLP-1R expression in extra-pancreatic organs. The main content of this review, however, is a literature discussion on the discovery and functional assessment of potential therapeutic effects of GLP-1-based drugs in chronic airway diseases and acute lung injuries. For more detailed discussions on utilization or potential utilization of GLP-1-based drugs, as well as dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD), kidney disorders, and neurodegenerative brain disorders, please see excellent review articles elsewhere1,12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18.

2. The incretin GLP-1 and its plasma elevation during inflammation

GLP-1 was recognized as the 2nd incretin hormone back in 198319,20. Ebert and colleagues observed that in a rat model, incretin activity was still preserved after gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP, also known as glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide) was removed from gut extracts by immune-adsorption20. Following the isolation of the proglucagon gene (GCG/Gcg) cDNA from fish, hamsters, rats, mice, and humans, it was evident that in addition to encoding glucagon, a counter-regulatory hormone of insulin, GCG/Gcg cDNAs also encode two additional polypeptides defined as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2)19,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27.

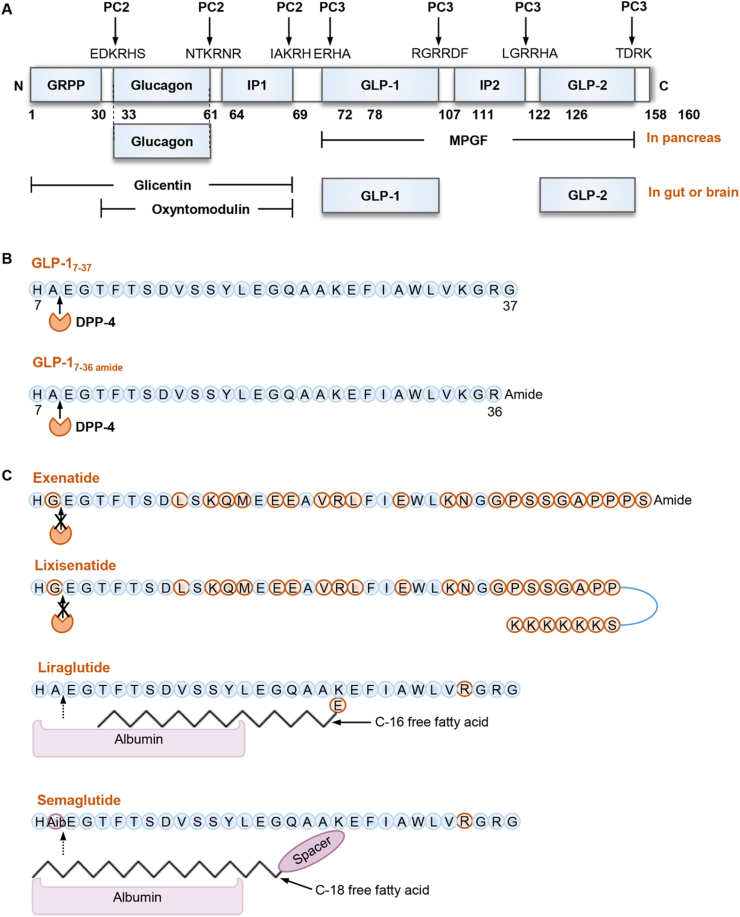

Gcg (GCG in humans) is abundantly expressed in pancreatic α-cells, intestinal endocrine L cells, and certain neuronal cells in the brain3,22,28. Post-translational processing of the pro-hormone proglucagon occurs in tissue-specific manners via prohormone convertases (PC) known as PC1/3 and PC2. As shown in Fig. 1A, in pancreatic α-cells, which mainly express PC2, proglucagon is processed to produce the active hormone glucagon and other products including major proglucagon fragments. In the brain and the intestinal endocrine L cells, the expression of PC3 (also known as PC1) leads to the catalysis of proglucagon into GLP-1 and GLP-2, as well as glicentin and oxyntomodulin23,25,26,29, 30, 31, 32, 33.

Figure 1.

GLP-1 and GLP-1-based drugs. (A) The structure of proglucagon and proglucagon-derived polypeptides (PGDPs). GRPP, glicentin-related pancreatic polypeptide. IP-1 and IP-2, intervening peptides 1 and 2; MPGF, major proglucagon fragment. GLP-1 and GLP-2, glucagon-like peptide 1 and 2. (B) The primary amino acid sequences of human GLP-17–37 and GLP-17–36amide. The ubiquitously expressed dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) will cleave X-alanine dipeptides from the N-terminus of GLP-17–37 or GLP-17–36amide to form GLP-19–37 or GLP-19–36amide, respectively. (C) Chemical structures of four GLP-1R agonists (GLP-1RAs). Due to amino acid substitution or non-covalent binding to albumin or immunoglobulin, these GLP-1RAs are protected from DPP-4 mediated degradation, thus having a much longer half-life.

Full-length GLP-1 consists of 37 or 36 amino acid residues, and it becomes biologically active after it is truncated at the N-terminus to form GLP-17–37 or GLP-17–36amide (Fig. 1B)34,35. As mentioned above, GLP-1 is the 2nd incretin hormone recognized to date36, 37, 38, 39 while GIP is the first one20,40,41. Incretins are defined as gut-produced hormones that can stimulate insulin secretion in a glucose concentration-dependent manner. The inhibitory effect of GLP-1 on glucagon secretion, however, was not shared by GIP42. Instead, a study showed that GIP might stimulate glucagon secretion from pancreatic islet α-cells42. Native GLP-1 (both GLP-17–37 and GLP-17–36amide) can be cleaved by the ubiquitously expressed enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) to produce GLP-19–37 or GLP-19–36amide, while further cleavage by neutral endopeptidase 24.11 leads to the production of GLP-128–36amide and GLP-132–36amide43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48. Although certain biological functions of GLP-19–36amide, GLP-128–36amide and GLP-132–36amide have been described in pre-clinical investigations by our team and others46, 47, 48, 49, those are generally considered as inactive “degradation” products of GLP-1. The half-life of GLP-1 is relatively short, around 1.5 min in human plasma. For mechanisms underlying GLP-1 secretion, please see review articles by our team and by others elsewhere50, 51, 52, 53.

In humans, circulating GLP-1 level starts to ramp up only a few minutes after nutrient intake. It reaches the peak around 1 h54. Among the nutrient components, glucose was shown to be the strongest stimulus of GLP-1 secretion, followed by sucrose, starch, triglycerides (TG), and certain amino acids50,51. Studies in animal models have suggested that systemic inflammation induced by endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) can also stimulate GLP-1 secretion in mice55, 56, 57. Kahles and colleagues observed that among the inflammatory stimuli including endotoxin, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-1β, it appears that IL-6 was sufficient and necessary to directly stimulate GLP-1 production and release; as in IL-6 knockout (KO) mice, endotoxin-induced GLP-1 secretion was found to be blunted57. It is worth mentioning that in rodent species especially in mice, plasma GLP-1 measurement is still a technical challenge and data obtained may not always be reliable. Nevertheless, Kahles and colleagues57 have also reported that in a cohort in intensive care unit (ICU), GLP-1 plasma levels correlated with inflammation markers and the disease severity. Consequently, they suggested that GLP-1 serves as a link between the immune system and the gut57. Indeed, metabolic illness and inflammatory diseases share certain common therapeutic targets58. Individuals who underwent cardiac surgery or autologous stem cell transplantation had up to 2-fold higher levels of circulating GLP-1, as reported by Lebherz and colleagues, as well as by Ebbesen and colleagues59,60. Patients with severe burn injury produced 3-fold more plasma GLP-1, while patients who died from severe burn injury had 5-fold higher GLP-1 levels than those who survived61. In addition, patients that suffered from sepsis combined with T2D displayed an enhanced activation of endogenous GLP-1 system compared to non-diabetic patients62. Thus, in both rodent models and in human subjects, systematic inflammation can cause plasma GLP-1 elevation. Further investigations are required to determine whether plasma GLP-1 level can be developed as a biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of inflammatory responses and inflammatory diseases. Patho-physiologically, elevated GLP-1 level during systematic inflammation may serve as a self-defense mechanism.

3. GLP-1R agonists as diabetes drugs

Although GIP was discovered more than a decade earlier than GLP-1, for various reasons, it has not yet been developed as a therapeutic agent. In 2005, the first GLP-1-based drug, exenatide (with the commercial name Byetta®), was approved by FDA for T2D treatment. Since then, ten additional GLP-1R agonists (GLP-1RAs) have been approved for T2D treatment. Table 1 lists those GLP-1RAs, as well as four DPP-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) and DPP-4i-based compound drugs.

Table 1.

FDA approved GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) and DPP-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i).

| Brand name | Active ingredient | FDA-approved year |

|---|---|---|

| GLP-1RA | ||

| Byetta | Exenatide | 2005 |

| Bydureon | Exenatide (extended release) | 2012 |

| Victoza | Liraglutide | 2010 |

| Saxenda | Liraglutide | 2014 |

| Xultophy 100/3.6 | Liraglutide and insulin degludec | 2016 |

| Tanzeum | Albiglutide | 2014 |

| Trulicity | Dulaglutide | 2014 |

| Adlyxin | Lixisenatide | 2016 |

| Soliqua 100/33 | Lixisenatide and insulin glargine | 2016 |

| Ozempic | Semaglutide | 2017 |

| Rybelsus | Semaglutide (oral) | 2019 |

| DPP-4i | ||

| Januvia | Sitagliptin | 2006 |

| Janumet | Sitagliptin and metformin | 2007 |

| Janumet XR | Sitagliptin and metformin (extended release) | 2012 |

| Steglujan | Sitagliptin and ertugliflozin | 2017 |

| Onglyza | Saxagliptin | 2009 |

| Kombiglyze XR | Saxagliptin and metformin (extended release) | 2010 |

| Qtern | Saxagliptin and dapagliflozin | 2017 |

| Qternmet XR | Saxagliptin, dapagliflozin and metformin (extended release) | 2019 |

| Tradjenta | Linagliptin | 2011 |

| Jentadueto | Linagliptin and metformin | 2012 |

| Jentadueto XR | Linagliptin and metformin (extended release) | 2016 |

| Glyxambi | Linagliptin and empagliflozin | 2015 |

| Tradjenta XR | Linagliptin, empagliflozin and metformin | 2020 |

| Nesina | Alogliptin | 2013 |

| Kazano | Alogliptin and metformin | 2013 |

| Oseni | Alogliptin and pioglitazone | 2013 |

Fig. 1C shows the structures of four GLP-1RAs, including exenatide, lixisenatide, liraglutide and semaglutide. Exenatide was developed based on studies in a peptide isolated from the saliva of the Gila monster, known as exendin-4. Exendin-4 contains 39 amino acid residues with a half-life of around 30 min, sharing 53% amino acid sequence homology with human GLP-163,64. As a synthetic version of exendin-4, exenatide is resistant to DPP-4-induced degradation which contributes to a longer half-life of about 2.4 h after subcutaneous injection65,66. Lixisenatide, another derivative of exendin-4, was approved by FDA in 201667,68. Liraglutide (Victoza®) was approved by FDA in 2010, which is a modified human GLP-1, sharing 97% sequence identity with native GLP-1. The non-covalent binding with albumin prevents its renal elimination. It is the first long-acting compound of GLP-1RAs, with a much longer half-life of 13 h69, 70, 71. Semaglutide (Ozempic) is the most recently approved long-acting GLP-1RAs for T2D in 2017, with a half-life of 7 days72,73. An equipotent once-daily oral administration form of semaglutide was approved in 201974. Table 1 also lists a few other GLP-1RAs. Among them, albiglutide consists of a dimer of human GLP-1 molecules fused to a recombinant human albumin, while dulaglutide consists of a dimer of human GLP-1 molecules fused to a modified human immunoglobulin G4 heavy chain9.

As shown in Fig. 1B, native GLP-1 can be cleaved by DPP-4, which is a ubiquitously expressed peptidase. DPP-4 can also inactivate GIP. Thus, DPP-4 inhibition can prevent the degradation of both native GLP-1 and GIP. DPP-4i can specifically inhibit the enzymatic degradation activity of DPP4 by over 80%, leading to a doubling of active GLP-1 level75. Sitagliptin (Januvia), developed by Merck & Co, was the first DPP-4i approved by the FDA as a T2D drug in 2006, followed by saxagliptin, linagliptin and alogliptin76, 77, 78. DPP-4i can be administered orally and formulated either as a single-ingredient product or in combination with other diabetes medicines, including metformin (Table 1). Although investigations have also been conducted in assessing the effects of DPP-4i in lung injury models, we will not cover those studies in current manuscript. Information on such studies can be found elsewhere79, 80, 81.

As a relatively novel category of T2D drugs, adverse drug reactions (ADRs) of GLP-1RAs have been intensively studied globally. As reviewed very recently by Shetty and colleagues, GLP-1RAs are most commonly associated with ADRs in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly pancreatitis82. Cardiovascular, renal, hematologic, dermatologic, neurologic, autoimmune, hepatic and metabolic associated ADRs were also identified for GLP-1RAs82. For more than a decade, the development of pancreatitis or even pancreatic cancer has been the major concern in utilizing GLP-1RAs. It has been summarized by Ryder in 2013, that for animal studies, the worrying pancreatic histological changes are not reproducible and are variable among the use of different GLP-1RAs; and that increased reports of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer by FDA are likely due to ‘notoriety bias’83. He then concluded that although we should remain vigilant, the balance of evidence at current stage is in supporting GLP-1-based therapy strongly, with beneficial effects far outweighing those potential risks83. For further information on common and rare ADRs of GLP-1RAs, please see review articles elsewhere82,84, 85, 86.

4. The anti-inflammation features of GLP-1 and its based diabetes drugs

Systemic inflammation is usually characterized by elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and imbalanced immune cells in the circulation. As the first FDA-approved GLP-1-based diabetes drug, the anti-inflammatory features of exenatide have been extensively investigated in patients with T2D. As early as 2007, Viswanathan et al.10 demonstrated that in subjects with T2D, exenatide had two “non-metabolic actions”: the effect on attenuating plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and the effect on lowering systolic blood pressure. A few years later, Kim et al.87 showed in mice that cardiomyocyte GLP-1R activation promoted the translocation of the rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor Epac2 to the membrane, leading to atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) elevation, which lowers blood pressure. Interestingly, they have also located GLP-1R expression in mouse cardiac atria87. In 2011, Wu et al.88 showed that in patients with T2D, 16-week exenatide treatment had not only reduced body mass index and improved hemoglobin A1c and glucose profiles; but also decreased circulating levels of inflammatory markers including high-sensitivity CRP and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Furthermore, the level of oxidative stress marker 8-iso-prostaglandin F2a, was also reduced following exenatide treatment88. The protein and mRNA levels of a battery of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-1β and IL-6 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC or MNC) were also shown to be suppressed by in vivo exenatide treatment in subjects with T2D89,90. Moreover, both investigations have revealed the anti-inflammatory effect of exenatide in the absence of body weight loss in patients with T2D with 12-week exenatide treatment89,90. Thus, the anti-inflammatory effect of exenatide may not always be secondary to its body weight-lowering effect89, 90, 91. The anti-inflammatory effect of liraglutide was also demonstrated recently by Zobel and colleagues in subjects with T2D92. In this clinical trial, subjects with T2D were on 26-week liraglutide treatment. Zobel and colleagues observed the discrete modulatory effect of liraglutide on the expression of inflammatory genes in PBMCs. Importantly, such modulatory effect was not observed in the in vitro settings with direct liraglutide treatment in the human monocytic cell line THP-192. Furthermore, Zobel and colleagues92 reported that GLP-1R expression could not be detected in the THP-1 cell line or PBMCs.

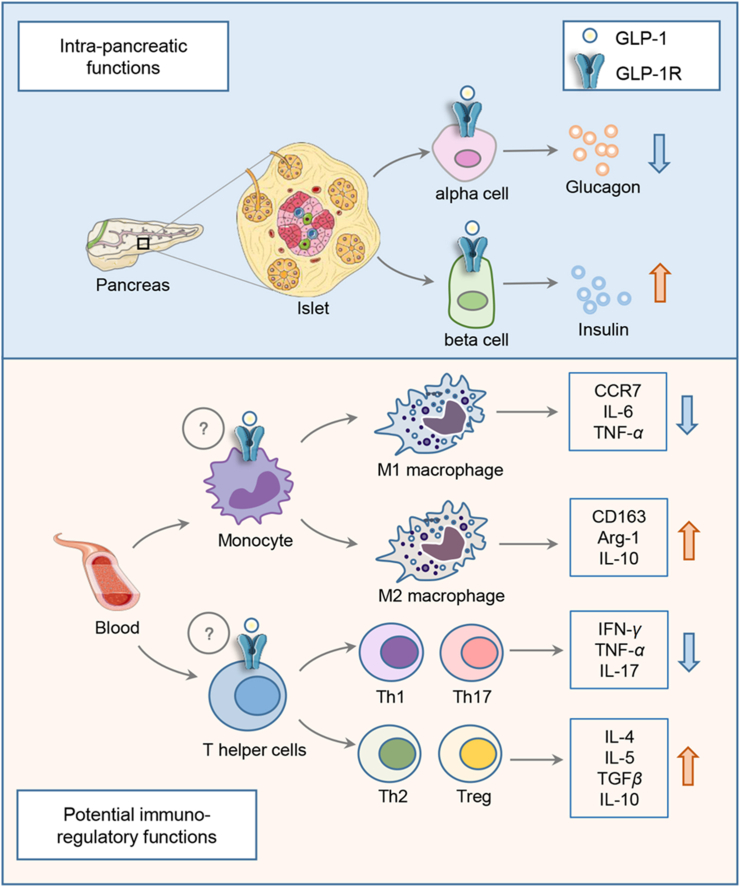

The anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1RAs were also observed in various animal models. Although GLP-1RAs showed no improvement in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D), Sherry et al.93 demonstrated that exenatide could facilitate the reversal of T1D in NOD mice treated with the “therapeutic” anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody. Mechanistically, the facilitation is likely involving the increase of anti-inflammatory subsets of T lymphocytes, such as T helper 2 and regulatory T cells in mice93, 94, 95. More recent studies have further demonstrated the T lymphocyte regulatory function of liraglutide and dulaglutide, as well as the DPP-4i sitagliptin96, 97, 98. The DPP-4i linagliptin was also shown to attenuate insulin resistance and inflammation by modulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization, as reported by Zhuge and colleagues99. In a Wistar rat model with intraperitoneal LPS challenge, exenatide treatment was shown to attenuate neutropenia, associated with decreased levels of a battery of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IFNγ100. Utilizing the pro-adipocytic 3T3-L1 and RAW264.7 macrophage cellular models, several studies have shown that the DPP-4i anagliptin or GLP-1RA liraglutide can inhibit nuclear factor-kappa B pathway and secretion of a series of pro-inflammatory cytokines101, 102, 103. Although a few studies have indicated the expression of GLP-1R in rodent immune cells95,98, as mentioned above, a more recent human study by Zobel and colleagues92 showed that the repressive effect of liraglutide on the expression of inflammatory genes in PBMCs was not observed in the in vitro settings with direct liraglutide treatment92. In addition, Zobel and colleagues92 could not detect GLP-1R in THP-1 or primary PBMCs. Fig. 2 summarizes our current understanding of the anti-inflammatory features of GLP-1RAs. As shown, intra-pancreatic functions of GLP-1 or GLP-1RAs are known to be mediated by GLP-1R. It remains to be determined whether in vivo immuno-regulatory functions of GLP-1RAs on immune cells are mediated by GLP-1R that are expressed in those cells or by yet to be further explored mechanism.

Figure 2.

Illustration of intra-pancreatic and potential immune-regulatory functions of GLP-1RAs. In pancreatic islets, GLP-1 or GLP-1RAs stimulates insulin secretion and represses glucagon secretion by pancreatic β-cells and α-cells, respectively, events that depend on GLP-1R. GLP-1RA in vivo administration exerts its regulatory function in both macrophages and T lymphocytes (T helper cells). It is unclear whether this is mediated by GLP-1R that is expressed in these two cell lineages (indicated with a question mark). In vivo GLP-1RA administration inhibits differentiation of M1 macrophage and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including CCR7, IL-6 and TNF-α. Conversely, M2 macrophage differentiation and the production of CD163, Arg-1 and IL-10 can be stimulated by in vivo GLP-1RA treatment. Meanwhile, GLP-1RA treatment may inhibit the differentiation of pro-inflammatory T helper cells, including Th1 and Th17, leading to reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interferon γ, TNF-α and IL-17. The differentiation of the anti-inflammatory T helper 2 and regulatory T cells, as well as the production of IL-4, IL-5, TGFβ and IL-10, however, could be promoted by in vivo GLP-1RA treatment.

5. Controversy on GLP-1R expression in extra-pancreatic organs

During the past two and a half decades, there are substantial controversies in the literature regarding GLP-1R expression in extra-pancreatic organs, including the liver, heart, and adipose tissues8,104, 105, 106, in addition to that in immune cells we have mentioned above92,95,98. Nevertheless, in vivo effects of GLP-1 and GLP-1RAs on the liver and other extra-pancreatic organs are clear and substantial104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109.

cDNA that encodes rat GLP-1R was initially isolated by Thorens et al.110 in 1992, while the first GLP-1R KO mouse line was created by Scrocchi et al.111 in 1996. In 1994, Campus et al.112 investigated the expression of mouse Glp1r using a combination of Northern blotting and RT-PCR. They reported the detection of Glp1r in small and large intestines, pancreas, liver, lung, and kidney. Wei and Mojsov113 then reported in 1995 that for human GLP-1R, the brain, heart and pancreatic forms have the same deduced amino acid sequence. In 1996, utilizing more specific approaches including RNase protection assay and in situ hybridization, along with RT-PCR, Bullock et al.114 reported the detection of Glp1r in the gastric pit of the stomach, large-nucleated cells in the lung, crypts of the duodenum, and pancreatic islets. They, however, cannot detect Glp1r signal in the kidney, skeletal muscle, heart, liver, or adipocytes114. They have suggested that the GLP-1R expressed in the kidney and heart might be structural variants of the known receptor114. The 2nd GLP-1 receptor theory, however, has not been proved or disproved during the past two and a half decades. A more recent study by Sato et al.115 showed the Glp1r expression in the lung alveoli utilizing the in situ hybridization approach.

Due to the profound hepatic function of GLP-1 and GLP-1RAs, efforts have been made in determining GLP-1R expression in the liver and hepatocytes. Several studies have shown the detection of Glp1r mRNA and GLP-1R protein in mouse or human hepatic cell lines and the mouse liver107,116,117, in contrast to the early report by Bullock et al.114 Investigations by Panjwani et al.105 and by Baggio et al.106 showed that the controversy could be partially due to the lack of reliable anti-GLP-1R antibodies, raising the issue of the development of more ones. With the none-bias RNA-seq and other approaches, we and others have shown that mouse or human liver does not express mRNA that encodes mouse or human GLP-1R104,108,109.

More reliable GLP-1R antibodies (3F52 for humans and 7F38 for mice) have been generated by Knudsen's team, which could be utilized in detecting GLP-1R expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) method118,119. When the human 3F52 antibody was utilized in monkey and human tissues, Pyke et al.118 reported the detection of GLP-1R signal in smooth muscle cells in the walls of arteries and arterioles. This observation correlates with a few functional studies, showing that exenatide treatment attenuated NR4A orphan nuclear receptor NOR1 in vascular smooth muscle cells120, and that GLP-1R over-expression in airway smooth muscle cells attenuated cell proliferation and migration, as well as secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines121. It appears that both 3F52 and 7F38 could not be utilized for detecting GLP-1R in tissue samples by Western blotting. Utilizing 7F38, we have shown the detection of GLP-1R in the lung of wild-type mice but not in GLP-1R KO mice122. Co-immune staining approaches need to be adopted, in combination with the utilization of GLP-1R KO mouse tissue samples, for determining which cell lineages in the lung that express GLP-1R. As discussed above, whether PBMCs and other immune cells express GLP-1R also remains controversial92,98. The immune-staining approaches should also be utilized for clarifying whether certain immune cells express GLP-1R, and whether their GLP-1R expression can be regulated in physiological and patho-physiological conditions.

As GLP-1R is known to be expressed in the brain, we have suggested that in vivo extra-pancreatic functions of GLP-1 and GLP-1RAs are either mediated by certain brain-peripheral tissue axis or by a small portion of GLP-1R-positive cells that are scattered within each of those organs. Very recently, McLean et al.123 conducted their investigation on potential murine Glp1r expression within endothelial and hematopoietic cells. They have created a mouse line with targeted inactivation of Glp1r in Tie2+ cells. Those mice exhibited reduced levels of Glp1r mRNA transcripts in aorta, liver, spleen, blood, and gut. Importantly, they have located liver Glp1r expression to γδ T lymphocytes while semaglutide mediated hepatic metabolic beneficial effects were observed in high fat diet challenged Glp1rTie2+/+ mice but not in Glp1rTie2−/– mice123. Hence, they have suggested that observed in vivo functions of GLP-1-based drugs in certain extra-pancreatic organs could be attributed to endothelial and hematopoietic-cell expressed GLP-1R123.

6. GLP-1-based drugs in airway diseases and lung injury studies

We have learned for more than 25 years that lung is an extra-pancreatic organ, which exhibits the highest level of Glp1r mRNA112,114. Hence, great efforts have been made in clinical trials and various lung injury animal models, seeking the possibility to repurpose GLP-1-based drugs in chronic airway diseases and acute lung injury treatment. Here we will present our literature review on clinical investigations as well as studies with chronic airway diseases and acute lung injury animal models. We will then summarize a few very recent studies on “therapeutic effects” of the combined use of human mesenchymal stem cells and GLP-1-based drugs in mouse acute lung injury models.

6.1. Studies in chronic airway diseases

Chronic airway diseases mainly include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiectasis, and bronchitis. As pre-clinical studies on GLP-1RAs have been conducted mainly on asthma and COPD, below we focus on presenting our literature review on these two categories of diseases.

6.1.1. Asthma

In a recent retrospective cohort study, Foer et al.124 have compared rates of asthma exacerbations and symptoms between patients with T2D and asthma prescribed GLP-1RAs and those prescribed sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, or DPP-4i, or sulfonylureas, or basal insulin. They observed that patients prescribed GLP-1RAs had lower counts of asthma exacerbation and encountered asthma symptoms after 6 months of the treatment, when compared with patients who received each of the other four categories of drugs124. In a human study, Mitchell et al.125 have measured the expression of GLP-1R, using flow cytometry staining and analysis, on eosinophils and neutrophils in normal and asthmatic subjects and then evaluated in vitro effects of a GLP-1RA on functions of eosinophils125. They reported that GLP-1R is expressed in human eosinophils and neutrophils. In eosinophils but not in neutrophils, GLP-1R expression is significantly higher in normal subjects when compared to subjects with allergic asthmatics. GLP-1R expression did not change on either eosinophils or neutrophils following the allergen challenge. Their in vitro study showed that GLP-1RA significantly decreased expression of eosinophil-surface activation markers following LPS stimulation and decreased eosinophil production of IL-4, IL-8 and IL-13, but not the IL-5, a key pro-inflammatory cytokine relevant to chronic airway disorders125.

IL-33, a member of the IL-1 family, is constitutively produced in fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells of the skin, lung, and gastrointestinal tract126. It is among crucial mediators of both innate and adaptive immune responses induced by aeroallergens. Genome-wide association studies have revealed the implication of the IL33 locus in the development of asthma127,128. To date, there is no known therapeutic agent that can inhibit the release of IL-33 from airway cells129. When Alternaria extract, an aeroallergen with protease activity, is intranasally administrated in mice, asthma attack can be induced. In this mouse model, Toki and colleagues assessed both “preventative” and “therapeutic” effects of liraglutide. Either administrated before or after Alternaria extract challenge, liraglutide suppressed IL-33 secretion, associated with decreased numbers of group 2 innate lymphoid cells, and reduced mucus production129. However, further mechanistic explorations are needed for clarifying the involvement of GLP-1R and the downstream signaling events. In another asthma mouse model challenged with ovalbumin for 81 days, intraperitoneal injection of liraglutide at 2 mg/kg twice daily in the last 66 days inhibited airway inflammation and mucus hyper-secretion through a protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent signaling pathway130.

6.1.2. COPD

In a meta-analysis study, Wei and colleagues131 have reported that the utilization of GLP-1-based drugs showed reduced trends in the risks of nine categories of respiratory diseases, including pneumonia, bronchitis, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, and COPD. However, GLP-1-based drug utilizations were shown to increase trends in interstitial lung disease.

COPD is among the top leading cause of death worldwide. Up to date, no approved therapy can reverse lung injury caused by COPD. Huang and colleagues reported that the expression of GLP-1R in PBMC isolated from COPD patients is lower than that in non-COPD subjects132. In vitro liraglutide treatment, however, upregulated GLP-1R expression and restored antigen-stimulated interferon γ production in T lymphocytes132. Considering the literature controversy on GLP-1R expression in extra-pancreatic organs, further investigations are needed for clarifying GLP-1R expression in immune cells with newly developed GLP-1R antibodies and other tools such as RNA-seq104,108,109,119,133. There is an on-going clinical trial operated by Hospital South-West Jutland, University of Southern Denmark on assessing the effects of liraglutide treatment in patients with COPD. This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, parallel-group two-center clinical trial, headed by Dr. Claus B. Juhl, will determine various pharmacological effects and functional outcomes of 4-, 20-, 40- and 44-week liraglutide treatment in 40 patients with COPD.

Pulmonary surfactant is a surface-active complex of proteins and phospholipids formed by type II alveolar cells, which plays important role in regulating the alveolar size and lung innate immunity, as well as in preventing fluid accumulation and maintaining dryness of the airway. In human type II pneumocytes isolated from cadaveric organ donors, Vara et al.134 found that native GLP-1 or exenatide could stimulate cAMP formation and phosphatidylcholine secretion; and such effects were shown to be reversed by the GLP-1R antagonist exendin (9–39). Early investigations have generated ovalbumin induced-asthma model and long-term LPS-induced rodent COPD model135,136. Combining these two models, Viby and colleagues137 have assessed the effect of liraglutide on improving lung functions in a female COPD mouse model. They found that mice treated with liraglutide or exenatide showed a much better clinical appearance and increased survival rate. They also observed reduced expression of surfactant proteins in their COPD female mouse model, associated with increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, levels of surfactants and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the lung were largely unaffected with liraglutide treatment in the female COPD mouse model137. One may speculate that long-term (>10 days) liraglutide administration may exert more profound “metabolic” beneficial effects in addition to its anti-inflammatory effect observed in the acute injury model. Nevertheless, the stimulatory effect on surfactant secretion was not observed in this in vivo model, in contrast with the in vitro assay with human type II pneumocytes isolated from cadaveric organ donors134. Thus, mechanisms underlying the improvement effect of liraglutide treatment in COPD are complicated, involving not only surfactants and pro-inflammatory cytokines, but also other yet to be identified components.

As mentioned above, Kim and colleagues87 have located mouse GLP-1R expression in mouse cardiac atria and shown that GLP-1R activation increased cardiac atria ANP secretion, leading to the reduction of blood pressure. As an atrial natriuretic peptide hormone, ANP is also recognized as a potent pulmonary vasodilator138. Although ANP is mainly produced in the heart, pulmonary ANP expression was reported, at least in rodent species at its mRNA level139. Utilizing the mouse COPD model, Balk-Moller et al.139 have assessed the lung function of GLP-1-based drugs. Although mouse lung functions did not differ between mice receiving PBS and exendin (9–39) (a GLP-1R antagonist) treatment, or between GLP-1R KO mice and their wild-type littermates, COPD mice receiving GLP-1-based drugs (liraglutide or exenatide) showed improved pulmonary functions, with less inflammation and 10-fold more ANP at the mRNA level. In isolated mouse bronchial sections, direct ANP treatment showed a moderate broncho-dilatory effect, while such effect was also observed, although less effective, with direct liraglutide treatment. Based on these findings, the authors suggested the existence of a link between GLP-1 and ANP in COPD. Balk-Moller and colleagues, however, did not assess pulmonary ANP production at peptide hormone level. Hence, it remains to be determined whether observed beneficial effects of liraglutide treatment is generated by ANP produced in cardiac atria only, or with the contribution of pulmonary produced ANP139. It is worth recalling that in 1993, a study by Richter et al.140 have identified GLP-1 binding site on rat mucous glands in the trachea and on vascular smooth muscle of the pulmonary artery. In isolated rings of rat arteries, GLP-1 was shown to induce relaxation of pre-constricted arteries, involving the secretion of macromolecules. Whether such macromolecules include ANP is worth to be investigated.

6.2. Nosocomial infection in the lung

Nosocomial infection especially that in the lung is a critical complication world widely. Lung chronic infections can be generated by respiratory pathogens including the most notorious pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the virulence factor of which is known as pyocyanin, was shown to attenuate the expression of forkhead box A2 (FOXA2), a key transcription factor of a battery of genes that are involved in mucus homeostasis141. Choi et al.142 have shown that FOXA2 expression was severely depleted in surface airway epithelial cells in patients with COPD, while exenatide treatment can restore FOXA2 expression in P. aeruginosa challenged mouse model.

6.3. Studies in acute lung injury

Acute lung injury (ALI) may lead to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) which is the major cause of respiratory failure in ICU. ARDS occurs when fluid builds up in alveoli of the lung. The fluid prevents the lungs from filling with enough air, leading to reduced oxygen in the bloodstream. There is no cure for ARDS yet, while the treatment focuses on supporting the patient while the lung heals. In serious conditions, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is needed. To our knowledge, GLP-1-based drugs have not been utilized in clinical trials for ALI. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, a very recent retrospective study has shown that the utilization of GLP-1-based drugs reduced trends in the risks of pneumonia, in addition to asthma and COPD131. Extensive investigations have, however, been conducted in ALI animal models, mainly with intratracheally LPS administration in mice143.

In 2011, Lim and colleagues144 have developed a “nanomedicine” designated as GLP1-SSM, in which human GLP-1 (7–36) is self-associated with PEGylated phospholipid micelles (SSM). They then demonstrated that in the LPS-induced ALI mouse model, subcutaneous GLP1-SSM administration decreased lung neutrophil influx, myeloperoxidase activity, and IL-6 levels in a dose-dependent manner144. In 2017, GLP-1-SSM was shown by this team to alleviate gut inflammation in a dextran sodium sulfate-induced mouse colitis model145.

Several recent studies have explored mechanisms underlying the attenuating effect of GLP-1RA in ALI animal models. Reduction of pulmonary surfactant is tightly associated with decreased pulmonary compliance and edema in ALI. Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) is known to play an important role in regulating levels of surfactant protein-A, the most abundant protein component of pulmonary surfactant. Romaní-Pérez et al.146 have reported that in rats, administration of exenatide or liraglutide to the mother from gestational day 14 to the birth increased SP-A and SP-B mRNA levels and amounts of SPs in the amniotic fluid at the end of pregnancy. Furthermore, they have reported that lung Glp1r mRNA level increased 4-fold on the 1st day of life in both male and female rats, while the level of expression was subsequently maintained into the adulthood146. In 2018, Zhu et al.147 found that in the ALI mouse model, LPS administration reduced lung SP-A and TTF-1 levels, while the reduction was reversed by simultaneous administration of liraglutide with LPS challenge. In 2019, in a similar mouse model, Xu and colleagues148 found that LPS challenge-induced polymorphonuclear neutrophil extravasation, lung injury, along with alveolar-capillary barrier dysfunction. Concomitant liraglutide administration prevented polymorphonuclear neutrophil-endothelial adhesion by inhibiting the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Other documented functions of GLP-1-based drugs in ALI models include the stimulation of the eNOS/sGC/PKG signaling cascade, the induction of vasorelaxant expression, and the inactivation of the nuclear factor-kappa B inflammatory signaling pathway149, 150, 151. However, none of these investigations have directly assessed the involvement of pulmonary GLP-1R.

In 2020, our team has directly assessed the involvement of GLP-1R in mediating effects of liraglutide treatment in the LPS-induced ALI mouse model. In this study, conducted by Zhou and colleagues122, liraglutide was not administrated simultaneously with LPS challenge but as a “preventative agent” which was subcutaneously administrated 2 h before intratracheal LPS delivery. In such experimental settings, we observed that liraglutide pre-treatment significantly reduced LPS-induced acute lung injury, including the reduction in lung injury score, wet/dry lung weight ratio, immune cell counts, protein concentration in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and cell apoptosis in the lung. Those effects were highly associated with reduced pulmonary mRNA expression of genes that encode inflammatory chemokines and cytokines. Importantly, none of those “preventative” effects were observed in GLP-1R KO mice, highlighting the essential role of lung GLP-1R in mediating the effect of liraglutide in preventing lung injury122. Based on such “preventative” effect observed, we suggested that retrospective studies should be conducted in T2D subjects treated with or without GLP-1-based drugs, asking whether T2D patients are less vulnerable to ALI as well as chronic lung inflammatory injury after receiving GLP-1-based drug treatment122,152,153.

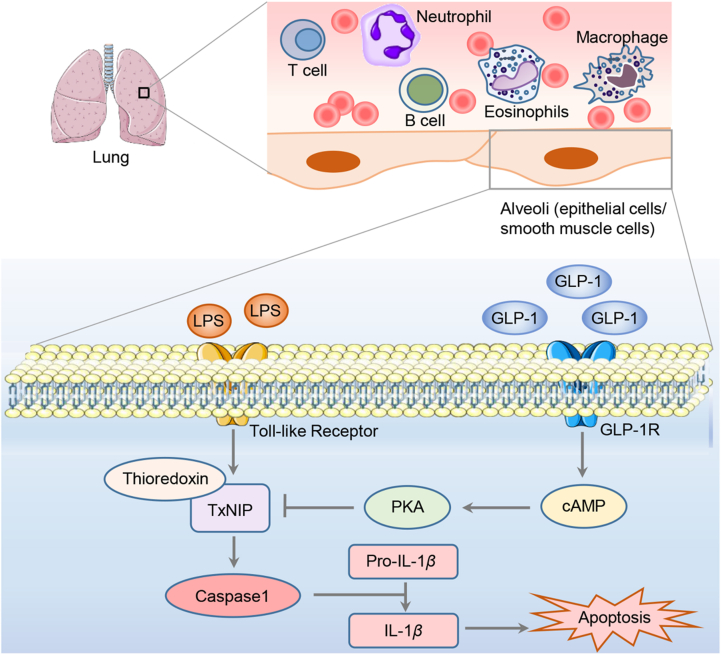

The study conducted by Zhou et al.122 has also revealed that liraglutide treatment attenuated LPS-induced pulmonary thioredoxin-interacting protein (TxNIP) over-expression, and such attenuation is also GLP-1R dependent. TxNIP is a member of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome component154, 155, 156, a mediator of glucotoxicity157,158, and a therapeutic target of T2D and other disorders155,158, 159, 160, 161. In addition to the high glucose challenge, TxNIP level in pancreatic β-cells was also shown to be stimulated by dexamethasone and streptozotocin, an antibiotic utilized in generating the T1D rodent model. Importantly, the LPS challenge caused approximately 2.5-fold elevation in lung TxNIP levels in wild-type littermates, while in GLP-1R KO mice, lung TxNIP increased about 7-fold after the challenge with the same amount of LPS. Thus, lung GLP-1R itself may represent a native defense system. In contrast to the observation made by Balk-Moller and colleagues139 in their COPD model, we did not see a stimulatory effect of liraglutide treatment on pulmonary nppa (which encodes ANP) expression. However, we observed that the LPS challenge led to a 3-fold activation on pulmonary nppa level. Whether such activation represents a protective or defensive response remains to be explored122. Fig. 3 summarizes our current understanding of pulmonary GLP-1R mediated protection in the ALI mouse model, in response to GLP-1RA treatment, involving the attenuation of the inflammasome component TxNIP. Further investigations are needed to determine the exact involvement of GLP-1R expressed in lung alveoli smooth muscle cells, epithelial cells, or both. GLP-1RAs may also exert their immune-regulatory functions on immune cells in the lung and the circulation.

Figure 3.

The effect of GLP-1RAs on LPS-induced ALI involving TxNIP reduction. GLP-1R is highly expressed in the lung, and likely includes alveoli epithelial cells and smooth muscle cells in the walls of arteries and arterioles. In addition, GLP-1RAs possess potent immunoregulatory functions in the lung, by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines produced by immune cells in the lung as well as in the circulation. Via the Toll-like receptor, the LPS challenge induces overexpression of TxNIP, a member of the NLRP3 inflammasome. NLRP3 inflammasome activation leads to the activation of caspase 1 and over-production of active IL-1β, which initiates the apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells and adhesion of immune cells (including monocyte-macrophages and neutrophils) to the capillary. Interaction between GLP-1RA and GLP-1R may lead to elevated intracellular cAMP level and the activation of PKA, which inhibits the expression of TxNIP.

6.4. Combined effect of MSC and GLP-1-based drugs

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are pluripotent adult stem cells162. They possess both self-renewal capacity and differentiation potential into several mesenchymal lineages including bones, cartilages, adipose tissues and tendons. MSCs can repair tissue injuries and prevent immune cell activation and proliferation, involving the secretion of growth factors and other macromolecules. MSC-based therapy may apply to lung injuries including ALI and radiation-induced lung injury, as well as other disorders163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168.

More than 18 years ago, Ortiz and colleagues162 demonstrated that when male mouse bone marrow-derived MSCs were intravenously administrated, they were able to home to the recipient female mouse lung in response to bleomycin-induced injury. Those MSCs were shown to adopt an epithelium-like phenotype, reducing both inflammation and collagen deposition162. Mechanistic exploration studies have then demonstrated that those MSCs can produce paracrine factors, such as IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-10, keratinocyte growth factor, and prostaglandin E2167,169. In LPS challenge induced ALI mouse model, Mei and colleagues demonstrated that bone-marrow derived MSCs with overexpressed angiopoietin 1 (Agn-1) further reduced the severity of lung injury170. Gupta and colleagues171 then demonstrated that in the LPS-induced ALI mouse model, intrapulmonary delivery of bone marrow-derived MSCs 4 h after LPS-challenge was still able to improve survival rate and attenuate lung injury. During the last decade, functions of MSCs from various sources including bone marrows, adipose tissues, lung tissues, as well as human chorionic villi were also assessed in multiple disease models. For studies on additional paracrine factors released by MSCs and mechanistic exploration of MSC therapy in lung injuries, please see review articles elsewhere172, 173, 174, 175. Below we will discuss a few recent studies that involve GLP-1 and GLP-1R.

In 2010, Sanz and colleagues176 reported the detection of GLP-1R in hMSC, derived from bone marrow. They found that in hMSC, GLP-1 treatment stimulated cell proliferation and reduced cell apoptosis. Furthermore, GLP-1 treatment prevented cell differentiation into adipocytes, associated with the repression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, C/EBPβ, and lipoprotein lipase. A few follow-up studies then tested the effect of the combined use of MSC and GLP-1 in myocardial infarction177, 178, 179. MSCs with GLP-1 conditioned media were shown to possess anti-apoptotic effects on ischaemic human cardiomyocytes179. MSCs that were engineered to secrete a GLP-1 fusion protein were shown to possess therapeutic effects in myocardial infarction in a pig model177,179.

More recently, attempts have also been made in testing the combined use of hMSC and liraglutide in ALI mouse model180,181. Last year, Yang and colleagues reported that LPS treatment could attenuate the proliferation of human chorionic villus-derived MSCs (hCMSCs), human bone marrow-derived MSCs (hBMSCs), and human adipose-derived MSCs (hAMSCs). In the LPS-induced ALI mouse model, liraglutide combined with MSCs showed a more significant therapeutic effect180. Dose-dependent reduction effects of LPS on hCMSC proliferation and expression of GLP-1R, Ang-1 and FGF-10 were then demonstrated in another study conducted by the same group by Fang and colleagues181. Furthermore, the study by Fang and colleagues181 demonstrated that liraglutide treatment dampened the above reductions, involving the cAMP/PKAc/β-catenin–TCF4 signaling pathway. The same study also reported that combined use of liraglutide and hCMSCs exhibited enhanced therapeutic efficacy than liraglutide alone in reducing lung injury in their mouse ALI model.

7. Summary

In this review, we have discussed both clinical and pre-clinical investigations on the anti-inflammatory and immune cell modulatory features of GLP-1 and GLP-1RAs. We commented that in vivo repressive effect of liraglutide on the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in PBMCs was not recaptured in the in vitro setting with direct liraglutide treatment92. Thus, it remains to be determined whether GLP-1RAs exert their anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory functions via indirect mechanisms. This could involve a brain–peripheral tissue axis, or via interaction with a small population of immune cells, such as intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) or certain T lymphocytes (γδ cells)123,182. Recent observations made by McLean et al.123 also indicated that functions of GLP-1RAs in extra-pancreatic organs could be attributed to GLP-1R expressed in endothelial and hematopoietic cell lineages, in agreement with the detection of GLP-1R in smooth muscle cells in the walls of arteries and arterioles of monkey and human lungs118.

GLP-1R is most abundantly expressed in mouse lung, demonstrated 25 years ago by Bullock et al.114 with methods including RNase protection and in situ hybridization. As lung GLP-1R level elevated 4 times on the 1st day of birth, and elevated plasma GLP-1 level was observed in patients with systematic inflammation, it is likely that GLP-1 and lung GLP-1R represent a yet to be further explored defense system of our body. Observations made in a few clinical trials and retrospective studies have supported the beneficial effect of GLP-1RAs in asthma and lung injury. Detailed understanding of this defense system and properly utilizing the tools in regulating this system may lead to better treatment of chronic airway diseases and ALI.

The key inflammasome component TxNIP, a known therapeutic target of diabetes, is also among the major targets of GLP-1/GLP-1R signaling pathway activation in the lung. Lung TxNIP elevation can be stimulated by plasma glucose level elevation or the release of the stress hormone glucocorticoid122, which is a recognized double-edged sword in ARDS treatment. Whether a moderate stimulation on lung TxNIP elevation in response to glucose and glucocorticoid elevation also represents a defensive response remains to be investigated. It is also worth determining whether TxNIP depletion brings beneficial or deleterious outcomes in mice with LPS or other inflammatory challenges.

Nanomedicine and hMSC-based cell therapy are the cutting-edge skills in translational medicine. GLP-1-SSM, a putative nanomedicine tool has already been tested in the ALI model, while combined hMSC and GLP-1-based drugs have been studied in a pig myocardial infarction model; and more recently, in the mouse ALI model. We anticipate seeing further applications of these two “therapies” in preclinical studies and clinical trials in near future.

The whole world has been undergoing the astonishing COVID-19 pandemic. There is literature debating whether GLP-1-based drugs may serve as a cure or adjuvant for COVID-19 treatment152,153,183,184. A recent meta-analysis conducted by Hariyanto and colleagues185 covered nine studies with 19,660 patients of T2D who were infected by SARS-CoV-2. The study suggested that pre-administration of GLP-1-based drugs was associated with a reduced mortality rate185. Further retrospective studies and pre-clinical studies should be conducted to determine the therapeutic and preventative potential of GLP-1RAs on COVID-19 animal models, as our battle with such pandemic is likely a long journey.

To repurpose GLP-1RAs for future treatment of lung injury including asthma, COPD and others, attention should be made to their known and yet to be identified ADRs. As mentioned above, the most common ADR of GLP-1RAs is pancreatitis, demonstrated in certain animal model studies and clinical observations82,83. In conducting a recent clinical comparative study on asthma patients with GLP-1RAs versus other T2D drugs, Foer and colleagues124 did not report the development of pancreatitis or other ADRs. This could be due to the relatively small sample size (n = 448 for patients treated with GLP-1RAs)124. In the most recent meta-analysis study conducted by Wei and colleagues131, GLP-1RA utilizations were shown to increase trends in interstitial lung disease. None of the previous animal studies, including the one conducted by our team122, have paid attention to the development of ADRs in the lung. Hence, future animal studies should be designed to verify whether the use of certain GLP-1RAs in the dosages for treating lung injury can cause different profiles of ADRs, or cause ADRs specifically in the lung.

Acknowledgments

Bench-work studies on pancreatic and extra-pancreatic functions of GLP-1 and its based drugs in Jin's lab have been supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT159735 to Tianru Jin, Canada). Juan Pang is a visiting PhD student supported by China Scholarship Council. Jia Nuo Feng is a PhD student supported by Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS) Program and the Banting & Best Diabetes Centre (BBDC)-Novo Nordisk Studentship.

Author contributions

Juan Pang: conceptualization, investigation, and writing-original draft. Jia Nuo Feng: conceptualization and investigation. Wenhua Ling: writing-review and editing. Tianru Jin, writing-review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

References

- 1.Muller T.D., Finan B., Bloom S.R., D'Alessio D., Drucker D.J., Flatt P.R., et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) Mol Metabol. 2019;30:72–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holst J.J. From the incretin concept and the discovery of GLP-1 to today's diabetes therapy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:260. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kieffer T.J., Habener J.F. The glucagon-like peptides. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:876–913. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.6.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drucker D.J. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metabol. 2018;27:740–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggio L.L., Drucker D.J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors in the brain: controlling food intake and body weight. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4223–4226. doi: 10.1172/JCI78371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sisley S., Gutierrez-Aguilar R., Scott M., D'Alessio D.A., Sandoval D.A., Seeley R.J. Neuronal GLP1R mediates liraglutide's anorectic but not glucose-lowering effect. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2456–2463. doi: 10.1172/JCI72434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secher A., Jelsing J., Baquero A.F., Hecksher-Sorensen J., Cowley M.A., Dalboge L.S., et al. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide-dependent weight loss. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4473–4488. doi: 10.1172/JCI75276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin T., Weng J. Hepatic functions of GLP-1 and its based drugs: current disputes and perspectives. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;311:E620–E627. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00069.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nauck M. Incretin therapies: highlighting common features and differences in the modes of action of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2016;18:203–216. doi: 10.1111/dom.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viswanathan P., Chaudhuri A., Bhatia R., Al-Atrash F., Mohanty P., Dandona P. Exenatide therapy in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with insulin. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:444–450. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Insuela D.B.R., Carvalho V.F. Glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 as novel anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory compounds. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;812:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drucker D.J. The cardiovascular biology of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metabol. 2016;24:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nauck M.A., Meier J.J. Incretin hormones: their role in health and disease. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2018;20(Suppl 1):5–21. doi: 10.1111/dom.13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nauck M.A., Meier J.J., Cavender M.A., Abd El Aziz M., Drucker D.J. Cardiovascular actions and clinical outcomes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Circulation. 2017;136:849–870. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallego-Colon E., Wojakowski W., Francuz T. Incretin drugs as modulators of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2018;278:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee Y.S., Jun H.S. Anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1-based therapies beyond glucose control. Mediat Inflamm. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3094642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Athauda D., Foltynie T. The glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP) receptor as a therapeutic target in Parkinson's disease: mechanisms of action. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21:802–818. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheen A.J. Pharmacokinetics and clinical use of incretin-based therapies in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell G.I., Sanchez-Pescador R., Laybourn P.J., Najarian R.C. Exon duplication and divergence in the human preproglucagon gene. Nature. 1983;304:368–371. doi: 10.1038/304368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebert R., Unger H., Creutzfeldt W. Preservation of incretin activity after removal of gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) from rat gut extracts by immunoadsorption. Diabetologia. 1983;24:449–454. doi: 10.1007/BF00257346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lund P.K., Goodman R.H., Montminy M.R., Dee P.C., Habener J.F. Anglerfish islet pre-proglucagon II. Nucleotide and corresponding amino acid sequence of the cDNA. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:3280–3284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell G.I., Santerre R.F., Mullenbach G.T. Hamster preproglucagon contains the sequence of glucagon and two related peptides. Nature. 1983;302:716–718. doi: 10.1038/302716a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orskov C., Holst J.J., Knuhtsen S., Baldissera F.G., Poulsen S.S., Nielsen O.V. Glucagon-like peptides GLP-1 and GLP-2, predicted products of the glucagon gene, are secreted separately from pig small intestine but not pancreas. Endocrinology. 1986;119:1467–1475. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-4-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White J.W., Saunders G.F. Structure of the human glucagon gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4719–4730. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.12.4719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinrich G., Gros P., Lund P.K., Bentley R.C., Habener J.F. Pre-proglucagon messenger ribonucleic acid: nucleotide and encoded amino acid sequences of the rat pancreatic complementary deoxyribonucleic acid. Endocrinology. 1984;115:2176–2181. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-6-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinrich G., Gros P., Habener J.F. Glucagon gene sequence. Four of six exons encode separate functional domains of rat pre-proglucagon. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14082–14087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irwin D.M. Molecular evolution of proglucagon. Regul Pept. 2001;98:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drucker D.J., Asa S. Glucagon gene expression in vertebrate brain. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:13475–13478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell J.E., Drucker D.J. Islet α cells and glucagon—critical regulators of energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:329–338. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pocai A. Unraveling oxyntomodulin, GLP1's enigmatic brother. J Endocrinol. 2012;215:335–346. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Z., Jin T. New insights into the role of cAMP in the production and function of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) Cell Signal. 2010;22:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong X., Shao W., Jin T. New insight into the mechanisms underlying the function of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 in pancreatic beta-cells: the involvement of the Wnt signaling pathway effector beta-catenin. Islets. 2012;4:359–365. doi: 10.4161/isl.23345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin T. Mechanisms underlying proglucagon gene expression. J Endocrinol. 2008;198:17–28. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orskov C., Wettergren A., Holst J.J. Biological effects and metabolic rates of glucagonlike peptide-1 7–36 amide and glucagonlike peptide-1 7–37 in healthy subjects are indistinguishable. Diabetes. 1993;42:658–661. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drucker D.J., Nauck M.A. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2006;368:1696–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weir G.C., Mojsov S., Hendrick G.K., Habener J.F. Glucagonlike peptide I (7–37) actions on endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 1989;38:338–342. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mojsov S., Weir G.C., Habener J.F. Insulinotropin: glucagon-like peptide I (7–37) co-encoded in the glucagon gene is a potent stimulator of insulin release in the perfused rat pancreas. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:616–619. doi: 10.1172/JCI112855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacDonald P.E., El-Kholy W., Riedel M.J., Salapatek A.M., Light P.E., Wheeler M.B. The multiple actions of GLP-1 on the process of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2002;51 Suppl 3:S434–S442. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drucker D.J., Philippe J., Mojsov S., Chick W.L., Habener J.F. Glucagon-like peptide I stimulates insulin gene expression and increases cyclic AMP levels in a rat islet cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:3434–3438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shuster L.T., Go V.L., Rizza R.A., O'Brien P.C., Service F.J. Incretin effect due to increased secretion and decreased clearance of insulin in normal humans. Diabetes. 1988;37:200–203. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nauck M.A., Homberger E., Siegel E.G., Allen R.C., Eaton R.P., Ebert R., et al. Incretin effects of increasing glucose loads in man calculated from venous insulin and C-peptide responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63:492–498. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-2-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El K., Campbell J.E. The role of GIP in alpha-cells and glucagon secretion. Peptides. 2020;125 doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2019.170213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holst J.J., Deacon C.F. Inhibition of the activity of dipeptidyl-peptidase IV as a treatment for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1663–1670. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.11.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kieffer T.J., McIntosh C.H., Pederson R.A. Degradation of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and truncated glucagon-like peptide 1 in vitro and in vivo by dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3585–3596. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deacon C.F., Nauck M.A., Toft-Nielsen M., Pridal L., Willms B., Holst J.J. Both subcutaneously and intravenously administered glucagon-like peptide I are rapidly degraded from the NH2-terminus in type II diabetic patients and in healthy subjects. Diabetes. 1995;44:1126–1131. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.9.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ip W., Shao W., Chiang Y.T., Jin T. GLP-1-derived nonapeptide GLP-1(28–36)amide represses hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression and improves pyruvate tolerance in high-fat diet-fed mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E1348–E1358. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00376.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao W., Wang Z., Ip W., Chiang Y.T., Xiong X., Chai T., et al. GLP-1(28–36) improves beta-cell mass and glucose disposal in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice and activates cAMP/PKA/beta-catenin signaling in beta-cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E1263–E1272. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00600.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomas E., Stanojevic V., McManus K., Khatri A., Everill P., Bachovchin W.W., et al. GLP-1(32–36)amide pentapeptide increases basal energy expenditure and inhibits weight gain in obese mice. Diabetes. 2015;64:2409–2419. doi: 10.2337/db14-1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nikolaidis L.A., Mankad S., Sokos G.G., Miske G., Shah A., Elahi D., et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with acute myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction after successful reperfusion. Circulation. 2004;109:962–965. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120505.91348.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ezcurra M., Reimann F., Gribble F.M., Emery E. Molecular mechanisms of incretin hormone secretion. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:922–927. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian L., Jin T. The incretin hormone GLP-1 and mechanisms underlying its secretion. J Diabetes. 2016;8:753–765. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bodnaruc A.M., Prud'homme D., Blanchet R., Giroux I. Nutritional modulation of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion: a review. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2016;13:92. doi: 10.1186/s12986-016-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chepurny O.G., Holz G.G., Roe M.W., Leech C.A. GPR119 agonist AS1269574 activates TRPA1 cation channels to stimulate GLP-1 secretion. Mol Endocrinol. 2016;30:614–629. doi: 10.1210/me.2015-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nauck M.A., Meier J.J. The incretin effect in healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes: physiology, pathophysiology, and response to therapeutic interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:525–536. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00482-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen A.T., Mandard S., Dray C., Deckert V., Valet P., Besnard P., et al. Lipopolysaccharides-mediated increase in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: involvement of the GLP-1 pathway. Diabetes. 2014;63:471–482. doi: 10.2337/db13-0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellingsgaard H., Hauselmann I., Schuler B., Habib A.M., Baggio L.L., Meier D.T., et al. Interleukin-6 enhances insulin secretion by increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from L cells and alpha cells. Nat Med. 2011;17:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nm.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kahles F., Meyer C., Möllmann J., Diebold S., Findeisen H.M., Lebherz C., et al. GLP-1 secretion is increased by inflammatory stimuli in an IL-6-dependent manner, leading to hyperinsulinemia and blood glucose lowering. Diabetes. 2014;63:3221–3229. doi: 10.2337/db14-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drucker D.J. Coronavirus infections and type 2 diabetes-shared pathways with therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2020;41:bnaa011. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnaa011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lebherz C., Kahles F., Piotrowski K., Vogeser M., Foldenauer A.C., Nassau K., et al. Interleukin-6 predicts inflammation-induced increase of glucagon-like peptide-1 in humans in response to cardiac surgery with association to parameters of glucose metabolism. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:21. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0330-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ebbesen M.S., Kissow H., Hartmann B., Grell K., Gorlov J.S., Kielsen K., et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 is a marker of systemic inflammation in patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yin H.N., Hao J.W., Chen Q., Li F., Yin S., Zhou M., et al. Plasma glucagon-like peptide 1 was associated with hospital-acquired infections and long-term mortality in burn patients. Surgery. 2020;167:1016–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perl S.H., Bloch O., Zelnic-Yuval D., Love I., Mendel-Cohen L., Flor H., et al. Sepsis-induced activation of endogenous GLP-1 system is enhanced in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34 doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eng J., Kleinman W.A., Singh L., Singh G., Raufman J.P. Isolation and characterization of exendin-4, an exendin-3 analogue, from Heloderma suspectum venom. Further evidence for an exendin receptor on dispersed acini from Guinea pig pancreas. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7402–7405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen Y.E., Drucker D.J. Tissue-specific expression of unique mRNAs that encode proglucagon-derived peptides or exendin 4 in the lizard. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4108–4115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davidson M.B., Bate G., Kirkpatrick P. Exenatide. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:713–714. doi: 10.1038/nrd1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nielsen L.L., Young A.A., Parkes D.G. Pharmacology of exenatide (synthetic exendin-4): a potential therapeutic for improved glycemic control of type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept. 2004;117:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fonseca V.A., Alvarado-Ruiz R., Raccah D., Boka G., Miossec P., Gerich J.E. Efficacy and safety of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in monotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes (GetGoal-Mono) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1225–1231. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Christensen M., Knop F.K., Vilsbøll T., Holst J.J. Lixisenatide for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expet Opin Invest Drugs. 2011;20:549–557. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.562191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Juhl C.B., Hollingdal M., Sturis J., Jakobsen G., Agersø H., Veldhuis J., et al. Bedtime administration of NN2211, a long-acting GLP-1 derivative, substantially reduces fasting and postprandial glycemia in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:424–429. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vilsbøll T., Zdravkovic M., Le-Thi T., Krarup T., Schmitz O., Courrèges J.P., et al. Liraglutide, a long-acting human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog, given as monotherapy significantly improves glycemic control and lowers body weight without risk of hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1608–1610. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Drucker D.J., Dritselis A., Kirkpatrick P. Liraglutide. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:267–268. doi: 10.1038/nrd3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lau J., Bloch P., Schäffer L., Pettersson I., Spetzler J., Kofoed J., et al. Discovery of the once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue semaglutide. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7370–7380. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scheen A.J. Semaglutide: a promising new glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:236–238. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lipscombe L.L. In poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, oral semaglutide was noninferior to liraglutide for reducing HbA1c. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:Jc29. doi: 10.7326/ACPJ201909170-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ahrén B., Landin-Olsson M., Jansson P.A., Svensson M., Holmes D., Schweizer A. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 reduces glycemia, sustains insulin levels, and reduces glucagon levels in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2078–2084. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stoian A.P., Sachinidis A., Stoica R.A., Nikolic D., Patti A.M., Rizvi A.A. The efficacy and safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors compared to other oral glucose-lowering medications in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2020;109 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ling J., Cheng P., Ge L., Zhang D.H., Shi A.C., Tian J.H., et al. The efficacy and safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for type 2 diabetes: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of 58 randomized controlled trials. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56:249–272. doi: 10.1007/s00592-018-1222-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gallwitz B. Clinical use of DPP-4 inhibitors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:389. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kawasaki T., Chen W., Htwe Y.M., Tatsumi K., Dudek S.M. DPP4 inhibition by sitagliptin attenuates LPS-induced lung injury in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;315:L834–L845. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00031.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang T., Tong X., Zhang S., Wang D., Wang L., Wang Q., et al. The roles of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) and DPP4 inhibitors in different lung diseases: new evidence. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.731453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kong L., Deng J., Zhou X., Cai B., Zhang B., Chen X., et al. Sitagliptin activates the p62–Keap1–Nrf2 signalling pathway to alleviate oxidative stress and excessive autophagy in severe acute pancreatitis-related acute lung injury. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:928. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04227-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shetty R., Basheer F.T., Poojari P.G., Thunga G., Chandran V.P., Acharya L.D. Adverse drug reactions of GLP-1 agonists: a systematic review of case reports. Diabetes Metabol Syndr. 2022;16 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ryder R.E. The potential risks of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer with GLP-1-based therapies are far outweighed by the proven and potential (cardiovascular) benefits. Diabet Med. 2013;30:1148–1155. doi: 10.1111/dme.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Filippatos T.D., Panagiotopoulou T.V., Elisaf M.S. Adverse effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Rev Diabet Stud. 2014;11:202–230. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2014.11.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Madsbad S., Kielgast U., Asmar M., Deacon C.F., Torekov S.S., Holst J.J. An overview of once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists—available efficacy and safety data and perspectives for the future. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2011;13:394–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Drab S.R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes: a clinical update of safety and efficacy. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2016;12:403–413. doi: 10.2174/1573399812666151223093841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim M., Platt M.J., Shibasaki T., Quaggin S.E., Backx P.H., Seino S., et al. GLP-1 receptor activation and Epac2 link atrial natriuretic peptide secretion to control of blood pressure. Nat Med. 2013;19:567–575. doi: 10.1038/nm.3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu J.D., Xu X.H., Zhu J., Ding B., Du T.X., Gao G., et al. Effect of exenatide on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Therapeut. 2011;13:143–148. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hogan A.E., Gaoatswe G., Lynch L., Corrigan M.A., Woods C., O'Connell J., et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue therapy directly modulates innate immune-mediated inflammation in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2014;57:781–784. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chaudhuri A., Ghanim H., Vora M., Sia C.L., Korzeniewski K., Dhindsa S., et al. Exenatide exerts a potent antiinflammatory effect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:198–207. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Derosa G., Franzetti I.G., Querci F., Carbone A., Ciccarelli L., Piccinni M.N., et al. Variation in inflammatory markers and glycemic parameters after 12 months of exenatide plus metformin treatment compared with metformin alone: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33:817–826. doi: 10.1002/phar.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zobel E.H., Ripa R.S., von Scholten B.J., Rotbain Curovic V., Kjaer A., Hansen T.W., et al. Effect of liraglutide on expression of inflammatory genes in type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97967-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sherry N.A., Chen W., Kushner J.A., Glandt M., Tang Q., Tsai S., et al. Exendin-4 improves reversal of diabetes in NOD mice treated with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody by enhancing recovery of beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5136–5144. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xue S., Wasserfall C.H., Parker M., Brusko T.M., McGrail S., McGrail K., et al. Exendin-4 therapy in NOD mice with new-onset diabetes increases regulatory T cell frequency. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1150:152–156. doi: 10.1196/annals.1447.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hadjiyanni I., Siminovitch K.A., Danska J.S., Drucker D.J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signalling selectively regulates murine lymphocyte proliferation and maintenance of peripheral regulatory T cells. Diabetologia. 2010;53:730–740. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chiou H.C., Lin M.W., Hsiao P.J., Chen C.L., Chiao S., Lin T.Y., et al. Dulaglutide modulates the development of tissue-infiltrating Th1/Th17 cells and the pathogenicity of encephalitogenic Th1 cells in the central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1584. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim S.J., Nian C., McIntosh C.H.S. Sitagliptin (MK0431) inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV decreases nonobese diabetic mouse CD4+ T-cell migration through incretin-dependent and -independent pathways. Diabetes. 2010;59:1739–1750. doi: 10.2337/db09-1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]