Abstract

Classic bladder exstrophy represents the most severe end of all human congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract and is associated with bladder cancer susceptibility. Previous genetic studies identified one locus to be involved in classic bladder exstrophy, but were limited to a restrict number of cohort. Here we show the largest classic bladder exstrophy genome-wide association analysis to date where we identify eight genome-wide significant loci, seven of which are novel. In these regions reside ten coding and four non-coding genes. Among the coding genes is EFNA1, strongly expressed in mouse embryonic genital tubercle, urethra, and primitive bladder. Re-sequence of EFNA1 in the investigated classic bladder exstrophy cohort of our study displays an enrichment of rare protein altering variants. We show that all coding genes are expressed and/or significantly regulated in both mouse and human embryonic developmental bladder stages. Furthermore, nine of the coding genes residing in the regions of genome-wide significance are differentially expressed in bladder cancers. Our data suggest genetic drivers for classic bladder exstrophy, as well as a possible role for these drivers to relevant bladder cancer susceptibility.

Subject terms: Genome-wide association studies, Gene expression

A genome-wide association study on classic bladder exstrophy reveals eight genome-wide significant loci, most of which contained genes expressed in embryonic developmental bladder stages.

Introduction

The bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex (BEEC) is a spectrum of congenital abnormalities which involves the abdominal wall, bony pelvis, the urinary tract, the external genitalia, and in the worse cases also the gastrointestinal tract. The BEEC represents the severe end of all human congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. The most common defect form, classic bladder exstrophy (CBE), is characterized by pubic diastasis, the evaginated bladder plate template, and an epispadic urethra. At birth, the visible bladder mucosa appears reddish and mucosal polyps may be seen on the surface. CBE is associated with kidney and other upper urinary tract anomalies with a higher occurrence in males compared to females1. Associated long-term complications include malignancies of the bladder comprising mainly urothelial cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma2,3. Recently, the CBE live prevalence for Germany has been estimated to be ~1:30,7004. Given the overall European population of ~450,000,000 (https://ec.europa.eu/) citizens, presumptively ~15,000 CBE patients live in Europe. State-of-the-art health care for this population should take the genetic and bladder cancer disposition into account.

To determine the genetic contribution to CBE, we previously performed two genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with subsequent meta-analysis and identified a susceptibility locus on chromosome 5q11.15,6. The present study aimed to identify further risk loci. Furthermore, we investigated if the identified genetic risk loci might be involved in the associated bladder cancer susceptibility. For this purpose, we performed the largest GWAS for CBE to date comprising 628 patients and 7352 ethnically matched controls. In detail, the present meta-analysis included seven independent discovery samples (Supplementary Information: Supplementary Table 1) comprising: 98 patients of Central European origin and 526 ethnically matched controls5, 110 patients of Central European origin and 1,177 ethnically matched controls6, 172 patients of Central European origin and 2588 ethnically matched controls, 57 patients of Italian origin and 1,325 ethnically matched controls, 62 patients of Spanish origin and 279 ethnically matched controls, 80 patients of Swedish origin and 238 ethnically matched controls, and 49 patients of UK origin and 1,219 ethnically matched controls, identifying eight genome-wide significant risk loci, seven of which are novel. Within these loci reside 10 coding genes (LPHN2, EFNA1, SLC50A1, DPM3, KRTCAP2, ISL1, TRIM29, SYT1, PAWR, GOSR2) and four non-coding genes (one pseudogene and three long non-coding RNA, respectively, HMGB1P47, ISL1-DT, LINC01974, and LINC01716). Among these coding genes, EFNA1 has been previously shown to be strongly expressed in mouse embryonic genital tubercle, urethra, and primitive bladder prompting us to re-sequence this gene in our cohort. To assess their embryonic and fetal expression, we generated mouse embryonic bladder total RNA-seq at CBE-relevant developmental stages E10.5, E12.5, and E15.5, and human embryonic and fetal urinary bladder and genital tissues total RNA-seq at gestational week 7, 7 to 7.5, 7.5, 8, and 9. Finally, to evaluate their possible link in the overall CBE bladder cancer susceptibility, we analyzed the expression of these genes in urothelial carcinoma tissues and in different bladder cancer cell lines obtained from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (EMBL-EBI) compared to healthy bladder tissue transcriptomic (GEO).

Results

GWAS meta-analysis

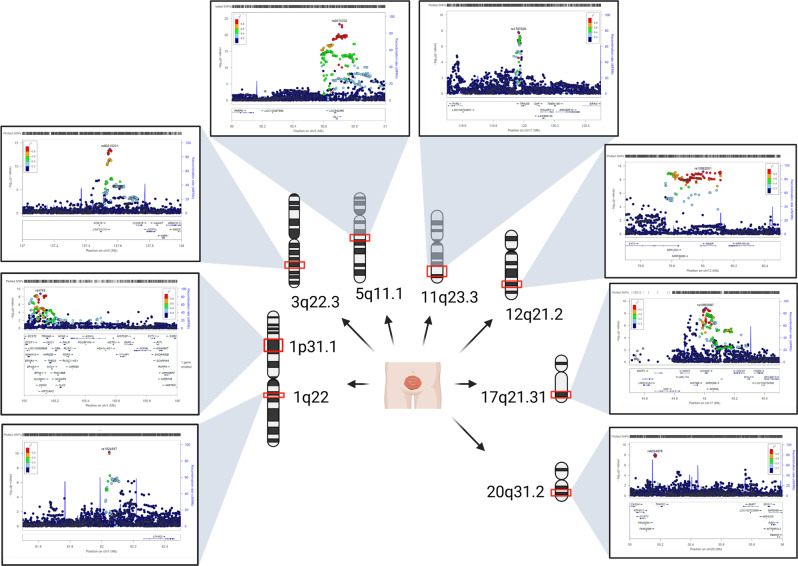

The meta-analysis of 628 patients with CBE and 7,352 ethnically matched controls comprised seven independent GWAS. These seven GWAS included the first two GWAS cohorts5,6, and five new CBE cohorts described above from Central European, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the UK along with ethnically matched control samples. We used a total of 8,289,003 SNPs with info score >0.4 and mean dosage for the minor allele >1% in cases and controls in at least one sample, obtaining a genomic inflation factor λ of 1.068. The respective Q-Q plot is shown in Supplementary information (Supplementary Fig. 16). Single marker analysis identified eight genome-wide significant loci shown in the Manhattan plot in Supplementary information (Supplementary Fig. 17) and the strongest signal at rs6874700 p = 5.58 × 10−24 corresponds to the 5q11.1 previously reported locus (Fig. 1)6. Table 1 shows the relative risks in each sample and in the meta-analysis for the most strongly associated SNP (top SNP) from each locus. Notably, with the exception of the UK sample where the top associated SNP on chromosome 12 was not significant, the direction of effect was consistent between all studies for these top SNPs. A complete list of all genome-wide significant SNPs is given in Supplementary Data 2. Regional association results for all eight genome-wide significant loci are shown in Fig. 1 and in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs. 1–8). For conditional logistic regression analyses the regional association plots are presented in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs. 20–27). The results provide no evidence that secondary signals in any of the eight loci are present.

Fig. 1. Chromosome regional association loci of CBE.

The eight CBE regional association loci (red boxes in chromosomes) reside in chromosome 1, 3, 5, 11, 12, 17, and 20. In the panels, details of the genome-wide association loci: every dot represents an SNP (x axes) plotted to the relative –log10(P value) (y axes). SNP are colored according to the relative r2 value.

Table 1.

Top SNPs from genome-wide significant loci.

| GWAS1 | GWAS2 | CE | Italy | Spain | Sweden | UK | Meta-analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Chromosome | risk/other allele | Info Score1 | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR 95% CI | RR 95% CI | RR 95% CI | RR 95% CI | p value | Corrected p value2 |

| rs1924557 | 1:82047934 | T/C | 0.93 | 1.75 (0.68−4.47) | 3.61 (1.37−9.49) | 3.76 (2.16−6.53) | 2.03 (0.98−4.19) | 3.51 (1.33−9.26) | 1.23 (0.68−2.22) | 5.00 (1.59−15.7) | 2.35 (1.82−3.03) | 6.65 × 10−11 | 2.67 × 10−10 |

| rs4745 | 1:155106227 | T/A | 0.96 | 1.19 (0.72−1.98) | 1.40 (0.91−2.16) | 1.47 (1.16−1.87) | 1.80 (1.16−2.78) | 1.17 (0.73−1.86) | 1.63 (1.13−2.36) | 1.16 (0.77−1.74) | 1.50 (1.32−1.71) | 4.44 × 10−10 | 1.58 × 10−9 |

| rs80215221 | 3:137550420 | G/A | 0.99 | 2.29 (1.29−4.09) | 1.95 (1.20−3.17) | 1.39 (1.08−1.79) | 1.89 (1.24−2.89) | 2.82(1.76−4.52) | 1.70 (1.16−2.51) | 1.99 (1.31−3.03) | 1.68 (1.47−1.92) | 2.26 × 10−14 | 1.49 × 10−13 |

| rs6874700 | 5:50701750 | A/T | 0.99 | 2.54 (1.49−4.33) | 1.33 (0.87−2.02) | 1.60 (1.28−2.01) | 1.98 (1.33−2.95) | 2.14 (1.33−3.45) | 1.94 (1.32−2.83) | 1.84 (1.20−2.80) | 1.91 (1.68−2.16) | 5.58 × 10−24 | 1.48 × 10−22 |

| 11:119964758:G:C | 11:119964758 | G/C | 0.98 | 1.38 (0.81−2.36) | 1.54 (0.98−2.42) | 1.32 (1.03−1.69) | 1.35 (0.90−2.04) | 1.14(0.72−1.80) | 1.68 (1.12−2.52) | 2.13 (1.40−3.24) | 1.47 (1.29−1.68) | 8.89 × 10−9 | 2.63 × 10−8 |

| rs10862001 | 12:80002106 | A/G | 0.83 | 2.02 (1.12−3.64) | 1.48 (0.89−2.47) | 1.77 (1.27−2.45) | 1.97 (1.22−3.18) | 1.03 (0.55−1.93) | 2.11 (1.26−3.54) | 0.83 (0.40−1.69) | 1.68 (1.43−1.99) | 6.84 × 10−10 | 2.37 × 10−9 |

| rs10853087 | 17:45006112 | C/G | 0.97 | 1.18 (0.72−1.93) | 1.44 (0.94−2.21) | 1.63 (1.29−2.06) | 1.60 (1.08−2.38) | 1.46 (0.93−2.29) | 1.26 (0.87−1.83) | 1.53 (1.01−2.31) | 1.47 (1.30−1.66) | 1.41 × 10−9 | 4.67 × 10−9 |

| 20:55165923:G:A | 20:55165923 | G/A | 0.97 | 2.30 (1.13−4.67) | 1.72 (0.95−3.12) | 1.46 (1.08−1.98) | 2.57 (1.39−4.76) | 1.00 (0.58−1.71) | 2.08 (1.23−3.51) | 1.89 (1.04−3.43) | 1.65 (1.39−1.96) | 7.31 × 10−9 | 2.19 × 10−8 |

1Mean imputation quality score (Info score)). Chromosomal positions are annotated according to Human Genome version 19 (hg19); CE Central Europe, UK United Kingdom

2p value corrected for genomic inflation λ = 1.068

Re−sequencing of EFNA1

Among the most significant markers, marker rs4745 resides directly in EFNA1. Mouse Efna1 has been shown to be expressed in CBE-relevant embryonic anatomical structures (https://www.gudmap.org/). This prompted us to re-sequence EFNA1 in 580 CBE patients. We identified 14 rare variants in 14 independent patients (Supplementary information, Supplementary Table 4). Four of these variants residing in the coding region of EFNA1 were found to be novel: two heterozygous missense variants c.116 T > C (p.Ile39Thr) and c.503 C > T (p.Ala168Val); one homozygous missense variant c.167 A > G (p.Asp56Gly), and a heterozygous loss of function (LoF) frameshift variant at c.341delT (p.Phe114Serfs*28). Parental samples were only available for the patient carrying variant c.116 T > C demonstrating paternal transmission. In silico prediction tools, Mutation Taster, Poly-Phen-2, and SIFT defined the missense variant c.116 T > C (p.Ile39Thr) as disease-causing, deleterious, and possibly damaging. The CADD score of 25.3 supports a functional implication of this variant on EFNA1 regulation. None, of the other missense variants, were scored deleterious. The LoF variant c.341delT (p.Phe114Serfs*28) has a CADD score of 25.6. For the estimation of the enrichment of rare protein-altering variants in EFNA1 in our cohort compared to the general population resembled by gnomAD, we use a very conservative comparison. Hence, we only included the three novel coding variants with CADD score >20, identified here in our re-sequencing approach of EFNA1. We compared these to missense or LoF variants in gnomAD less or equal to 5 (≤5 in 250,000; MAF ≤ 0,00002) consistent with rare penetrant dominant phenotypes. These criteria identified 162 missense and LoF variants in gnomAD (baseline 250,000 alleles; https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/gene/ENSG00000169242?dataset=gnomad_r2_1). Per se, it is possible that some of these variants are cis/trans in the same individuals but if we would be able to define this it would only make the association stronger. For comparison, we used Fisher’s exact test. Taking this assumption, the chi-square statistic using Fisher´s exact test, yielded 18.0159, and the p value is 0.000022. We added this statistic to our results.

Analysis of mouse and human embryonic total RNA-sequencing data of the identified genes in mouse and human embryonic and fetal urinary bladder and genital tissues

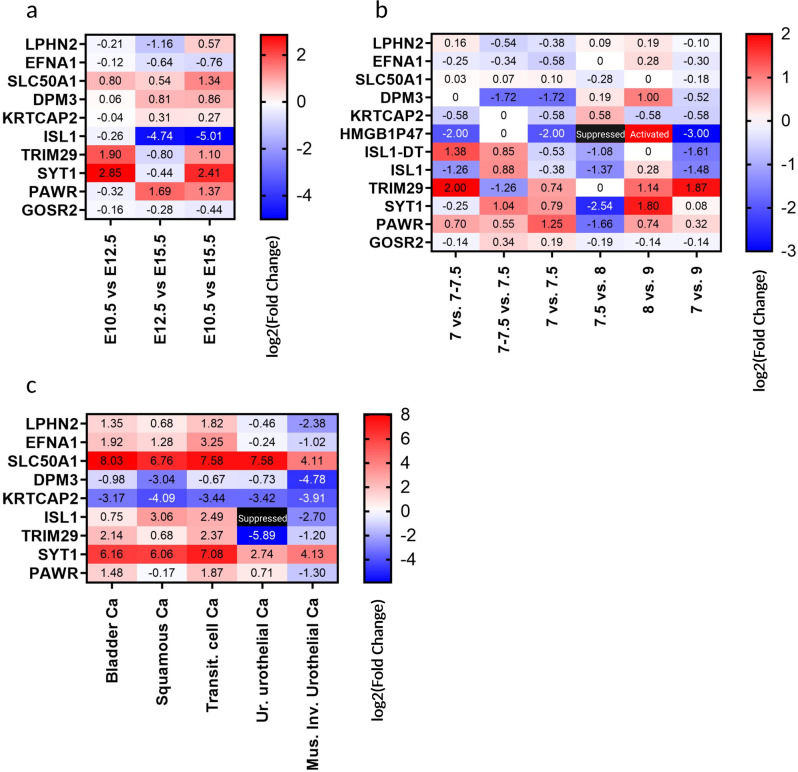

In the linkage disequilibrium block of all eight top SNPs reside 10 coding genes, four non-coding genes comprising one pseudogene, and three Long Intergenic Non-Protein Coding RNAs (Table 2). All 10 coding genes showed expression in mouse embryonic bladder at E10.5, E12.5, and E15.5. Isl1, Trim29, Syt1, and Pawr showed differential expression through different mouse embryonic stages (Table 3, Fig. 2a). As in mouse transcriptome, all 10 coding genes showed expression in the human embryonic bladder during different developmental stages. DPM3, TRIM29, SYT1, and PAWR showed differential expression at different human embryonic respectively fetal stages (Table 3, Fig. 2b). While the two LINC01974 and LINC01716 are not expressed in any of the bladder developmental stages, the pseudogene HMGB1P45 and the long noncoding RNA ISL1-DT are strongly downregulated; the first from weeks 7 to 7.5 followed by gene silencing at week 8 and 9 and the latter shows a downregulation trend from weeks 7 to 9.

Table 2.

Coding and non-coding genes in the LD blocks of the most significant markers for CBE.

| Gene name | Associated SNP | Protein encoded | Type | Cellular location | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPHN2 | rs1924557 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L2 | G protein-coupled receptor | Transmembrane of plasma membrane | Exocytosis regulator |

| EFNA1 | rs4745 | Ephrin-A1 | Tyrosine kinase receptor | Transmembrane of plasma membrane | GPI-bound ligand for Eph receptors, involved in cell migration, repulsion, and adhesion |

| SLC50A1 | rs4745 | Solute Carrier Family 50 Member 1 | Glucose transporter | Transmembrane of plasma membrane | Sugar transport across membranes |

| DPM3 | rs4745 | Dolichol-phosphate mannosyltransferase subunit 3 | Synthase of mannosyl residual | Endoplasmic reticulum membrane | Stabilizer subunit of DPM complex (DPM1, DPM2, and DPM3) |

| KRTCAP2 | rs4745 | Kerotinocyte-associated protein 2 | Subunit of the oligosaccharyl transferase complex | Endoplasmic reticulum membrane | Protein N-glicosilation. Transfer of defined glycan (Glc(3)Man(9)GlcNAc(2). |

| ISL1 | rs6874700 | Insulin Gene Enhancer Protein ISL-1 | Transcription Factor | Nucleus | DNA-binding transcriptional activator |

| TRIM29 | 11:119964758 | Tripartite motif-containing protein 29 | Zinc finger and Leucine zipper motif | Nucleic acid binding and macrophage activation | |

| SYT1 | rs10862001 | Synaptotagmin-1 | Ca(2+) sensor | Transmembrane of synaptic vesicles | Triggering neurotransmitter release |

| PAWR | rs10862001 | Pro-Apoptotic WT1 Regulator | Apoptosis inducer | Nucleus and cytoplasm | Downregulation of BCL2 via its interaction with WT1 |

| GOSR2 | rs10853087 | Golgi SNAP receptor complex member 2 | Trafficking membrane protein | Golgi | Protein transport from the cis/medial-Golgi |

| LINC01974 | rs10853087 | / | Long ncRNA | Unknown | Unknown |

| LINC01716 | 20:55165923 | / | Long ncRNA | Unknown | Unknown |

| HMGB1P47 | rs6874700 | / | Long ncRNA | Unknown | Unknown |

| ISL1-DT | rs6874700 | / | Long ncRNA. ISL1 divergent transcript. | Unknown | Unknown |

Table 3.

RNA expression patterns of coding and non-coding genes in the LD blocks of the most significant GWAS markers in mouse and human embryonic urogenital tissue.

| Mouse embryonic transcriptome data | Human embryonic transcriptome data | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Gene | log2fc E10.5 vs. E12.5 | log2fc E10.5 vs. 15.5 | log2fc E12.5 vs. 15.5 | Gene | log2fc 7 vs. 7-7.5 | log2fc 7-7.5 vs. 7.5 | log2fc 7 vs. 7.5 | log2fc 7.5 vs. 8 | log2fc 7 vs. 9 | log2fc 8 vs. 9 |

| rs1924557 | LPHN2 | −0.21 | 0.57 | −1.16 | LPHN2 | 0.16 | −0.54 | −0.38 | 0.09 | −0.10 | 0.19 |

| rs4745 | EFNA1 | −0.12 | −0.76 | −0.64 | EFNA1 | −0.25 | −0.34 | −0.58 | 0.00 | −0.30 | 0.28 |

| rs4745 | SLC50A1 | 0.80 | 1.34 | 0.54 | SLC50A1 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.10 | −0.28 | −0.18 | 0.00 |

| rs4745 | DPM3 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.81 | DPM3 | 0.00 | −1.72 | −1.72 | 0.19 | −0.52 | 1.00 |

| rs4745 | KRTCAP2 | 0.27 | 0.31 | −0.04 | KRTCAP2 | −0.58 | 0.00 | −0.58 | 0.58 | −0.58 | 0.58 |

| rs6874700 | ISL1 | −0.26 | −5.01 | −4.76 | ISL1 | −1.26 | 0.88 | −0.38 | −1.37 | −1.48 | 0.28 |

| 11:119964758 | TRIM29 | 1.90 | 1.10 | −0.80 | TRIM29 | 2.00 | −1.26 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 1.87 | 1.14 |

| rs10862001 | SYT1 | 2.85 | 2.41 | −0.44 | SYT1 | −0.25 | 1.04 | 0.79 | −2.54 | 0.08 | 1.8 |

| rs10862001 | PAWR | −0.32 | 1.37 | 1.69 | PAWR | 0.70 | 0.55 | 1.25 | −1.66 | 0.32 | 0.74 |

| rs10853087 | GOSR2 | −0.16 | −0.44 | −0.28 | GOSR2 | −0.14 | 0.34 | 0.19 | −0.19 | −0.14 | −0.14 |

| Marker | Non-coding Gene | log2fc E10.5 vs. E12.5 | log2fc E10.5 vs. 15.5 | log2fc E12.5 vs. 15.5 | Non-coding gene | log2fc 7 vs. 7–7.5 | log2fc 7–7.5 vs. 7.5 | log2fc 7 vs. 7.5 | log2fc 7.5 vs. 8 | log2fc 7 vs. 9 | log2fc 8 vs. 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs6874700 | HMGB1P47 | n.e. | HMGB1P47 | −2.00 | 0.00 | −2.00 | activated | −3.00 | suppressed | ||

| rs6874700 | ISL1−DT | n.e. | ISL1−DT | −1.38 | 0.85 | −0.53 | −1.8 | −1.61 | 0.00 | ||

| rs10853087 | LINC01974 | n.e. | LINC01974 | n.e. | |||||||

| 20:55165923 | LINC01716 | n.e. | LINC01716 | n.e. | |||||||

Bold: differential expressed genes (log2fc <−1.5 or >1.5).

log2fc log2 fold change, vs. versus, Chr. chromosome, n.e. not expressed. Differential expression defined with log2fc <−1,5 or >1,5.

Fig. 2. Expression heatmaps of genes that reside in the LD blocks of the eight significant genetic markers.

a Genes expression pattern in mouse embryonic bladder from embryonic day E10.5 to E12.5, E12.5 to E15.5, and E10.5 to E15.5. b Genes expression pattern in human embryonic and fetal bladder from week 7 to 7–7.5, 7–7.5 to 7.5, 7 to 7.5, 7.5 to 8, 8 to 9, and 7 to 9. c Genes expression pattern of 3-year-old control bladder tissue compared to Bladder carcinoma (Bladder Ca), Bladder squamous cell carcinoma (Squamous cell Ca), Bladder transitional cell carcinoma (Transit. cell Ca), Ureter urothelial carcinoma (Ur. Urothelial Ca), Muscle invasive urothelial cancer (Mus. Inv. Urothelial Ca). Legend: Suppressed = gene is silenced and no expression is detected. Activated = gene shows expression after a silenced state.

Comparison of RNA-sequencing data of the identified genes in healthy bladder tissue and different types of bladder cancer cell lines and muscular invasive urothelial carcinoma

Expression of non-coding genes in healthy bladder tissue and muscular invasive urothelial carcinoma could not be detected due to polyA-RNA-sequencing (Table 4). Despite this, we found all coding genes to be differentially expressed when compared to healthy bladder tissue (Table 5, Fig. 2c). In detail, SLC50A1 and SYT1 were significantly upregulated in all cancers compared to healthy bladder tissue. On contrary, DPM3 and KRTCAP2 were significantly downregulated. All other coding genes LPHN2, EFNA1, ISL1, TRIM29, PAWR, and GOSR2 were differentially up- or downregulated in different cancers (Table 5, Fig. 2c).

Table 4.

Average TPM of coding and non-coding genes in the LD blocks of the most significant GWAS markers calculated for each bladder cancer cell line.

| Marker | Coding and non-coding genes | Control tissue | Bladder Ca | Transit. cell Ca | Squamous cell Ca | Ur. urothelial Ca | Mus. Inv. Urothelial Ca |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1924557 | LPHN2 | 6.87 | 17.47 | 24.25 | 11.00 | 5.00 | 1.32 |

| rs4745 | EFNA1 | 8.25 | 31.30 | 78.50 | 20.00 | 7.00 | 4.06 |

| rs4745 | SLC50A1 | 0.24 | 62.60 | 46.00 | 26.00 | 46.00 | 4.15 |

| rs4745 | DPM3 | 131.29 | 66.55 | 82.50 | 16.00 | 79.00 | 4.77 |

| rs4745 | KRTCAP2 | 170.89 | 18.95 | 15.75 | 10.00 | 16.00 | 11.37 |

| rs6874700 | ISL1 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 2.03 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| 11:119964758 | TRIM29 | 11.86 | 52.27 | 61.25 | 19.00 | 0.20 | 5.15 |

| rs10862001 | SYT1 | 0.06 | 4.30 | 8.13 | 4.00 | 0.40 | 1.05 |

| rs10862001 | PAWR | 13.47 | 37.65 | 49.25 | 12.00 | 22.00 | 5.46 |

| rs10853087 | GOSR2 | 11.25 | 16.80 | 12.50 | 5.00 | 16.00 | 3.69 |

| rs6874700 | HMGB1P47 | RNA-polyA-seq | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | RNA-polyA-seq |

| rs6874700 | ISL1-DT | RNA-polyA-seq | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.5 | 0.00 | RNA-polyA-seq |

| rs10853087 | LINC01974 | RNA-polyA-seq | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | RNA-polyA-seq |

| 20:55165923 | LINC01716 | RNA-polyA-seq | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | RNA-polyA-seq |

urothelial carcinoma tissues and control bladder tissue.

TPM for Non-coding genes in Control tissue and Muscolar invasive urothelial cancer do not show reads due to polyA-sequencing. Legend: Bladder tissue of a 3-year-old bladder donor (control tissue); Bladder carcinoma (Bladder Ca); Bladder transitional cell carcinoma (Transit. cell Ca); Bladder squamous cell carcinoma (Squamous Ca); Ureter urothelial carcinoma (Urothelial Ca); Bladder urothelial carcinoma (Bl. urothelial Ca); Muscle invasive urothelial cancer (Mus. Inv. Urothelial Ca); RNA-polyA-seq data do not include miRNAs or lincRNAs.

Table 5.

log2-fold change of genes in the LD blocks of the most significant GWAS markers of bladder cancer cell types and muscle-invasive urothelial cancer over bladder control tissue.

| Marker | Coding and non-coding genes | Control tissue vs. bladder Ca | Control tissue vs. transit. cell Ca | Control tissue vs. squamous cell Ca | Control tissue vs. Ur. urothelial Ca | Control tissue vs. Mus. Inv. urothelial Ca |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1924557 | LPHN2 | 1.35 | 1.82 | 0.68 | 0.46 | −2.38 |

| rs4745 | EFNA1 | 1.92 | 3.25 | 1.28 | −0.24 | −1.02 |

| rs4745 | SLC50A1 | 8.03 | 7.58 | 6.76 | 7.58 | 4.11 |

| rs4745 | DPM3 | −0.98 | −0.67 | −3.04 | −0.73 | −4.78 |

| Rs4745 | KRTCAP2 | −3.17 | −3.44 | −4.09 | −3.42 | −3.91 |

| rs6874700 | ISL1 | 0.75 | 2.49 | 3.06 | suppressed | −2.70 |

| 11:119964758 | TRIM29 | 2.14 | 2.37 | 0.68 | −5.89 | −1.20 |

| rs10862001 | SYT1 | 6.16 | 7.08 | 6.06 | 2.74 | 4.13 |

| rs10862001 | PAWR | 1.48 | 1.87 | −0.17 | 0.71 | −1.30 |

| rs10853087 | GOSR2 | 0.54 | 0.12 | −1.21 | −0.47 | −1.65 |

| rs6874700 | HMGB1P47 | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq |

| rs6874700 | ISL1-DT | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq |

| rs10853087 | LINC01974 | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq |

| 20:55165923 | LINC01716 | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq | RNA-polyA-seq |

Bold: differential expressed genes (log2fc <−1.5 or >1.5)

Log2 fold change for non-coding genes of different bladder cancers and Muscolar Invasive Urothelial cancer over control tissue shows no value due to polyA-sequencing of control tissue. Differential Expression defined with log2fc <−1.5 or >1.5 (marker in bold italic letters). Legend: Bladder tissue of a 3-year-old bladder donor (control tissue); Bladder carcinoma (Bladder Ca); Bladder transitional cell carcinoma (Transit. cell Ca); Bladder squamous cell carcinoma (Squamous Ca); Ureter urothelial carcinoma (Urothelial Ca); Bladder urothelial carcinoma (Bl. urothelial Ca); Muscle invasive urothelial cancer (Mus. Inv. Urothelial Ca); RNA-polyA-seq data does not include miRNAs or lincRNAs). log2fc log2 fold change; differential expression defined with log2fc <−1.5 or >1.5 (marker in bold italic letters). vs. versus, Chr. chromosome.

Discussion

Recently, we described SLC20A1, encoding a sodium-phosphate symporter, as the putative monogenic dominant disease gene for isolated BEEC7. We were able to support our genetic data through functional studies in non-BEEC human embryos, mouse embryos, and zebrafish Morpholino knockdown experiments. To our knowledge, the present genetic study with a focus on the multifactorial genetic background of the BEEC is the largest study on CBE to date. We identified eight genome-wide significant risk loci. Within these loci, we determined possible CBE candidate genes using transcriptome datasets of CBE-relevant mouse embryonic, human embryonic, and fetal urogenital tissues at different developmental stages. Additionally, we provide a possible link between the identified putative candidate genes and CBE-associated bladder cancer susceptibility.

In detail, in direct proximity to the most significant markers of all eight risk loci reside nine coding genes that are expressed in CBE-relevant mouse and human urogenital tissues during different embryonic stages. Four of these candidate genes (Isl1, Trim29, Syt1, Pawr) showed differential expression in mouse embryonic urogenital tissues, five of these candidate genes (DPM3, ISL1, TRIM29, SYT1, and PAWR), and two of the non-coding genes (HMGB1P47, ISL1-DT) showed differential expression in human embryonic urogenital tissues. Previous reports of transgenic mouse lines of Isl1 and Syt1 revealed phenotypic overlap to the human CBE phenotypic spectrum. The Hoxb6Cre;Isl1 cKO hindlimb skeletons exhibited proximal defects in particular the os pubis and ischium, two posterior segments of the pelvic girdle, were missing, resembling pubic diastasis, a human BEEC-specific feature1,8. Transgenic Syt1tm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi/Syt1tm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi mice among other features develop thoracoschisis9, a rare congenital anomaly characterized by the evisceration of intra-abdominal organs through a thoracic wall defect10 mirroring the BEEC associated infraumbilical abdominal wall defect1.

One of the most significant markers identified in the present GWAS resides within EFNA1. In general, a probability of being LoF intolerant (pLi) score of 0.46 for EFNA1 is suggestive of possessing LoF intolerance for this gene in the context of the CBE condition. Although the pLi of 0.46 is only suggestive of LoF we have to consider that bladder exstrophy is not a mortal condition at birth. Hence, we believe that a value of 0.46 is supportive for EFNA1 to be implied in CBE11. Previously, in EFNA1 only two LoF variants were observed in the entire gnomad (frequency of 0,000016). Here, we observed one in 580 (frequency of 0,0017). Furthermore, in EFNA1 in the entire gnomad database, 96 missense variants were observed in 125,099 individuals (frequency of 0,00077). Here, we identified three in 580 (0,0052). Based on this observation, we performed a conservative estimation of whether LoF or missense variants might be enriched in EFNA1 in our CBE cohort compared to the general population showing a significant difference between both cohorts (p 0.000022). This finding suggests a possible implication of these variants in CBE formation in a multifactorial inheritance model among the affected.

Comparative analysis of control and bladder cancer tissues showed that all of the ten candidate genes were differentially expressed in bladder cancers. SLC50A1 and SYT1 were significantly upregulated in all cancers compared to healthy bladder tissue. On contrary, DPM3 and KRTCAP2 were significantly downregulated. LPHN2 has been suggested to have a regulatory role in urothelial bladder cancer12. EFNA1 plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of several tumors, including renal cell carcinoma, bladder, and prostate cancer13,14. Mapping all putative candidate genes prioritized in the present study to the search tool for retrieval of interacting genes (STRING), we found probable interaction of three proteins comprising: (i) gene fusions between EFNA1 and SLC50A1, and (ii) co-expression between EFNA1 and DPM3, (iii) and EFNA1 and SLC50A1 (Supplementary information: Supplementary Fig. 28). The PPI enrichment p-value was determined with 0.000205. Gene clustering analysis suggested clustering for EFNA1, DPM3, and SLC50A1 (Supplementary information: Supplementary Fig. 28). All three genes EFNA1, DPM3, and SLC50A1, respectively the genomic region 1q21-q22, been previously associated with the 2D:4D ratio, a sexually dimorphic trait, that has been extensively used in adults as a biomarker for prenatal androgen exposure15. Markers in the region of EFNA1, DPM3, SLC50A1 have previously been associated with prostate cancer risk16. Prostate cancer risk on the other side correlates with serum testosterone levels17. All of these observations suggest a possible gene-environmental interaction for this region. Adding to this hypothesis in the context of embryonic CBE formation, CBE presents with a higher occurrence rate in males compared to females1, a skewed sex ratio that is so far not explained, but could be influenced by differences in intrauterine androgen exposure between males and females.

The tumor suppressor gene TRIM29 is up regulated during early and late embryonic bladder development but is down-regulated in three different bladder cancers18. More specific, TRIM29 protein has been shown to be a driver of invasive and non-invasive bladder cancer. Interestingly, TRIM29-driven bladder cancers in transgenic mice were indistinguishable from gene expression signatures of human bladder cancers19. PAWR, has been previously shown to be a key altered gene in human bladder cancer stem cells20. SYT1 has been reported as a possible oncogene in colon cancer21. The knockdown of SYT1 markedly inhibits colon cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and induces cell apoptosis, indicating that SYT1 may function as an oncogene in colon cancer21. ISL1 has been associated with high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer in several studies22,23. Here we found downregulation of ISL1 in embryonic stages of mouse and human CBE urogenital tissues. Vice versa we found dysregulation of ISL1 expression in three bladder cancers. Hence, dysregulation of ISL1 expression in human embryonic and adult bladder tissues might contribute to the CBE and bladder malignancies vice versa.

To date, this is the largest genetic study on CBE. We have identified eight genome-wide significant risk loci. Our transcriptomic analysis of CBE-relevant mouse embryonic, human embryonic, and fetal urogenital tissues suggests candidate genes within these loci. Bladder cancer transcriptomic suggests these candidate genes play a possible role in the CBE-associated bladder cancer susceptibility. Identification of the different expressions to turn these developmental genes on later in life might ultimately lead to preventive strategies for bladder cancer per se.

Methods

Patients and recruitment

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of each participating center. All experimental protocols were approved by the institutional committee of the University of Bonn (Lfd.Nr.031/19). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, guardians, and healthy controls. We included 420 newly recruited isolated CBE patients and 5,649 healthy controls of European origin. Details can be found in the Supplementary information (Supplementary Table 1). Details about the 208 CBE patients and 1,703 ethnically matched controls of our previous studies, included in the present meta-analysis, are described in [5,6], in summary, CBE patients were recruited under written informed consent by BEEC expert physicians.

Sample description

In addition to the two previously described samples GWAS1 and GWAS26, five new samples of patients with bladder exstrophy and representative controls were obtained from Central Europe, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, and Sweden. The number of cases and controls used in this study are shown in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Table 1).

Genotyping

All samples, cases, and controls, were genotyped on Illumina human genotyping arrays. In GWAS 1 (Reutter et al. 2014), cases and controls were genotyped in two batches. Due to the discontinuation of the genotyping arrays utilized for earlier batches, different arrays were used comprising Illumina’s Human610-Quad (H610Q) and Human660W-Quad Bead Chips and the Illumina HumanOmni1-Quad-v1 Bead Chip. In GWAS 26, all cases and controls were genotyped using the Illumina BeadChip HumanOmniExpress. The five novel GWAS case samples were newly genotyped simultaneously using the Illumina “Infinium Global Screening Array-24 v2.0”. The five novels ethnically matched control samples were also genotyped using the Illumina “Infinium Global Screening Array-24 v2.0”. However, the five novel control samples were not genotyped together with the five novel case samples but independently of each other.

Quality control of individuals

An individual was excluded if (i) the call rate was <97%; (ii) the rate of autosomal heterozygosity deviates more than six standard deviations from the mean; (iii) the rate of X-chromosomal heterozygous genotypes was >2% for a supposed male individual or <10% for a supposed female individual. PLINK version 1.9 and KING were used to detect pairs of closely related individuals within and between samples24,25. From each pair of individuals with an estimated identity by descending probability >0.2 or kinship coefficient >0.0884, the individual with a higher rate of missing genotypes was discarded. Individuals being outliers in a multidimensional scaling analysis (MDS) were removed. The post-quality control sample sizes are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Principal component analysis

Individuals with:

| 1 |

were considered to be outliers. c1 and c2 denote the first two MDS coordinates of the individual and m1, m2 and s1 and s2 denote the mean and standard deviation, respectively, of the first two MDS coordinates in European HapMap individuals. For the five new samples (Central Europe, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the UK), Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs. 9–13) show the first two MDS coordinates for all genotyped individuals together with Asian and African HapMap individual. For the samples of GWAS1 and GWAS2, the MDS coordinates used in our previous studies are shown in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs. 14, 15).

Quality control of variants and imputation

Separately in each of the different ethnicity samples, SNPs were removed if (i) the minor allele frequency was <1% in either cases or controls; (ii) the successful genotyping rate was >95% in either cases or controls; (ii) the p value for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was <10−4 in controls or <10−6 in cases. SNPs satisfying the quality filters were uploaded for imputation on the University of Michigan Imputation Server using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel26.

Statistical analysis for genome-wide association analysis

Association testing was performed by logistic regression using SNPTEST version 2.5.2 for the allele dosage and adjusted for the sample-specific top five MDS coordinates27. For each SNP, a meta-analysis with the fixed-effects inverse variance-weighting approach was conducted by including only those samples in which the info score was >0.4 and the mean dosage for the minor allele was >1% in cases and controls for the respective SNP. SNPs reaching a p value <5*10−8 in the meta-analysis are considered to be genome-wide significant. Q-Q and Manhattan plots for the meta-analysis were created by SAS28. Regional association plots for genome-wide significant loci were generated with LocusZoom29. To look for secondary signals of association in loci of genome-wide significance, logistic regression using SNPTEST conditioned on the most associated SNP in the locus was carried out.

Protein–protein interaction networks analysis

Putative candidate genes within identified risk loci were mapped to the STRING to acquire protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks (https://string-db.org/). The search tool integrates both known and predicted PPIs. Here it was used to predict functional interactions of proteins30,31. Active interaction sources, including text mining, experiments, databases, and co-expression as well as species limited to “Homo sapiens” and an interaction score >0.4 were applied to construct the PPI networks. In the networks, the nodes correspond to the proteins and the edges represent the interactions. STRING was employed to seek potential interactions among putative candidate genes. Active interaction sources, including experimental repositories, computational prediction methods, and public text collections as well as species limited to “Homo sapiens” and a combined score >0.4, were applied.

Re-sequencing of EFNA1

Re-sequencing of all coding exons of EFNA1 of transcript ENST00000368407.3 was performed in 580 CBE patients, all of which were included in the current GWAS. PCR conditions can be obtained upon request, primer sequences are shown in Supplementary information (Supplementary Table 2). Sequencing files for patient, parent, and control DNA were added to databases created using PreGap4 software, with control DNA processed as the reference sequence.

Genes prioritization

Lower p-value SNP of each associated region was imputed in LDproxy Tool (https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/?tab=ldproxy) for European populations of CEU (Utah residents from north and west Europe); TSI Toscani in Italia; FIN Finnish in Finland; GBR British in England and Scotland; IBS Iberian population in Spain. Out of this, genes that reside in the linkage disequilibrium blocks defined from LD variants of r^2 above 0.8 to the top SNPs were taken into consideration for this study (Supplementary information, Supplementary Figs. 1–8). LD blocks coordinate regions imputed in hg19 are described in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Table 3).

No variants were significant LD associated with rs1924557 in chromosome 1 to determine an LD block region.

RNA isolation and mRNA library preparation of mouse embryonic urinary bladder and genital tissues

Animals were anesthetized with Isoflurane and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Ethical consent is documented and approved by the local authorities of the Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt. Embryos from timed-pregnant females of the SWISS strain were harvested at embryonic days (E) E10.5, E12.5, and 15.5 (Supplementary information: Supplementary Fig. 18). The respective developmental Theiler stages were determined as 18 (TS18), TS21, and TS23. From E10.5 embryos, the urogenital ridge was dissected under an M205C stereo microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany) surgically isolated, and transferred into QIAzol®. Embryos were pooled for each time point. For E10.5 stage biopsies from three embryos were pooled biopsies to prepare RNA, for E12.5 and E15.5 stages two embryos were pooled for RNA preparation. From E12.5 (primitive bladder) and E15.5 (bladder) embryos, the distinct structures of the developing and distinct visible bladder were surgically isolated (Supplementary information: Supplementary Fig. 18), combined, and transferred into QIAzol®.

Processing of total mouse embryonic RNA-sequencing data

About 50 million unique mapped reads per sample were obtained from each RNA-seq experiment. The reads were aligned using STAR aligner32. Read count was calculated with GenomicFeatures Bioconductor package. Calculation and normalization of “transcripts per kilobase million (TPM)” accounting for reads per kilobase (RPK) was performed as described elsewhere33. The fold change was calculated by dividing the subsequent stage by the preceding one and the log2 function was applied to the division as following: log2 (FoldChange) = log2 (subsequent embryonic stage/preceding embryonic stage). Differentially expressed genes were identified with values less than or equal to −1.5 or ≥1.5, respectively. The same algorithm was applied for the calculation of TPM of already deposited human embryonic and fetal RNA-seq data at EMBL-EBI expression atlas (accession code: E-MTAB-6592).

The raw RNA-sequencing data of mouse embryonic urinary bladder are deposited at GEO with the accession id: GSE190641.

Processing of bladder cancer RNA-sequencing data

Total RNA was purified using the QuantSeq library (Lexogen) with 500 ng RNA input. QuantSeq polyA RNA-tail libraries were sequenced (Single end 1 × 75 bp) on an Illumina Hiseq platform and generated data were further processed according to the GRCh38, TPM transformed, and further normalized. Sequencing, aligning and TPM calculation was performed by ImmunityBioTM. Visualization of results in heatmaps was performed using graphpad PRISM 9.0.0.

RNA isolation and mRNA library preparation of human embryonic and fetal urinary bladder and genital tissues

Embryonic and fetal bladders and genital tissues were obtained by surgeons from terminated pregnancies after informed consent was obtained and with ethics approval. Pregnancies were terminated for social indications and the respective fetuses and embryos were healthy. The embryonic tissues comprised 7-week embryos, 7–7.5-week embryos, 7.5-week embryos, late 8-week embryos, and late 9-week embryos (Supplementary information: Supplementary Fig. 19). Samples comprised week 7 (n = 2), 7.5 (n = 1), 8 (n = 3), 9 (n = 4) for the bladder tissues and for the genital tissues from week 7 (n = 3), 8 (n = 3), 9 (n = 3), and 10 (n = 4). Gene expression data were extracted and analyzed after high throughput sequencing of paired-end mRNA libraries (Illumina). Data were deposited at EMBL-EBI expression atlas (accession code: E-MTAB-6592). Calculation of fold change of already deposited human embryonic RNA-seq data was carried out accordingly to our calculation of mouse embryonic data (see in Methods: Processing of total mouse embryonic RNA-sequencing data).

Processing of bladder cancer RNA-sequencing data

Cancer RNA-seq data were obtained from already deposited data at EMBL-EBI expression atlas (Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia, experiment E-MTAB-2770). The deposited data does not include samples derived from CBE patients. Out of 1019 different cancer cell lines, the following cell line sample has been analyzed: 20 cell lines of bladder carcinoma, one cell line of bladder squamous cell carcinoma, four cell lines of bladder transitional cell carcinoma, one cell line of ureter urothelial carcinoma. TPM average was then calculated for each carcinoma cell type and data were compared with fold change to TPM of deposited mature urinary bladder polyA RNA-seq data (GEO accession: GSM1067793). In addition, RNA-polyA-seq data available from 38 cases of the CCC-EMN bladder cancer cohort [12] were generated from FFPE tissue all classified with Muscular invasive urothelial carcinoma. Demographic data is found in Supplementary Data 1.

Statistics and reproducibility

Quality control of individuals, principal component analysis, Quality control of variants and imputation, Statistical analysis for GWAS, and Genes prioritization is meticulously described in the methods above.

Average of TPM was calculated in R from biological replicates. Log2FC of human and mouse bladder was calculated as following: log2(AVERAGE_TPMnext_stage/AVERAGE_TPMprevious_stage). Log2FC of cancer cells was calculated as following: log2(AVERAGE_TPMcancer_line/AVERAGE_TPMcontrol_bladder_tissue). Sample size of mouse consists in n = 3 for embryo bladder at stage E10.5, and n = 2 for E12.5 and E15.5. Human fetal bladder samples comprised week 7 (n = 2), 7.5 (n = 1), 8 (n = 3), 9 (n = 4). Human cancer cells liens comprised n = 20 of bladder carcinoma cell, n = 1 of bladder squamous cell carcinoma cell line, n = 4 of bladder transitional cell carcinoma cell lines, n = 1 of ureter urothelial carcinoma cell line, n = 38 of muscular invasive urothelial carcinoma. Replicates are defined as a minimum of three technical replicates per sample size.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Data

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following institutions and organizations for founding and/or contributing to the project: BONFOR; Instituto de Salud Carlos III; Medical Research Council; Horizon 2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Initial Training Network; RENALTRACT; Alzheimer Research UK; Stroke Foundation/British Heart Foundation. We acknowledge financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg within the funding programme “Open Access Publication Funding”.

Author contributions

E.M., B.O., P.G., M.K., W.N., G.B., A.N., A.S.W., and H.R. conceptualized and supervised the research. E.M., M.K., G.C.D., and M.E. C.M., were engaged in biostatistics and bioinformatics analysis. E.M., P.G., M.E. B.O., P.G., H.R., A.S.W., A.C.H., and G.B. designed and performed most experiments. W.R., A.-K.E., R.S., A.B., M.D.G., A.T., F.M.T., J.L.H., P.E., J.M.O., J.A.R., C.V., I.C.H., H.H., D.J.W., J.S., J.G., A.-S.G., B.C.B., S.A., E.Å., E.R., M.L., G.H., E.G., A.B., D.K., R.M.C., N.Y., M.O., J.O., B.H., M.P., C.N., K.H., M.S., F.-M.S., E.S., T.M.B.., I.A.L.M.v.R., W.F.J.F., C.L.M.M., M.L., J.N., B.U., C.F., D.P.G., M.M.Y.C., K.U.L., M.M.N., S.H., N.Z., E.J. were responsible for patient recruitment and biospecimen and clinical data collection. E.M., G.B., M.K., A.S.W., P.G., and H.R. drafted the manuscript. E.M. designed the graphic illustrations. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Jack Weaver and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Chiea Chuen Khor and George Inglis.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

GWAS generated and analyzed data during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files. GWAS data are deposited at NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog with accession ID: GCST90132313. EFNA1 DNA sequencing data are deposited in GeneBank (BankIt) with the following accession numbers: OP312051; OP312052; OP312053; OP312054; OP312055; OP312056; OP312057; OP312058; OP312059; OP312060; OP312061; OP312062; OP312063. The raw RNA-sequencing data of the 38 Muscular Invasive Urothelial carcinomas are deposited at NCBI in Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the following BioProject accession: PRJNA882449. The raw RNA-sequencing data of mouse embryonic urinary bladder are deposited at GEO with the accession id: GSE190641. The raw RNA-sequencing data of human embryonic and fetal urinary bladder and genital tissue are deposited at EMBL-EBI expression atlas with the following accession id: E-MTAB-6592. The raw RNA-sequencing data of cancer cell lines are obtained from EMBL-EBI expression atlas with the following accession id: E-MTAB-2770, PolyA RNA-sequencing of the mature urinary bladder is obtained from GEO with the following accession id: GSM1067793.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Enrico Mingardo, Glenda Beaman, Philip Grote, Michael Knapp, Heiko Reutter.

Contributor Information

Enrico Mingardo, Email: enming@uni-bonn.de.

Heiko Reutter, Email: Heiko.Reutter@uk-erlangen.de.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-022-04092-3.

References

- 1.Ebert A-K, Reutter H, Ludwig M, Rösch WH. The exstrophy-epispadias complex. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2009;4:23. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahm P, Gschwend JE. Malignant non-urothelial neoplasms of the urinary bladder: a review. Eur. Urol. 2003;44:672–681. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson SR, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Cheng L. Glandular lesions of the urinary bladder: clinical significance and differential diagnosis. Histopathology. 2011;58:811–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebert AK, Zwink N, Reutter HM, Jenetzky E. A prevalence estimation of exstrophy and epispadias in Germany from Public Health Insurance Data. Front. Pediatr. 2021;9:648414. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.648414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reutter H, et al. Genome-wide association study and mouse expression data identify a highly conserved 32 kb intergenic region between WNT3 and WNT9b as possible susceptibility locus for isolated classic exstrophy of the bladder. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:5536–5544. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draaken M, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis identify ISL1 as genome-wide significant susceptibility gene for bladder exstrophy. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:1005024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieke JM, et al. SLC20A1 is involved in urinary tract and urorectal development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:567. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itou J, et al. Islet1 regulates establishment of the posterior hindlimb field upstream of the Hand2-Shh morphoregulatory gene network in mouse embryos. Development. 2012;139:1620–1629. doi: 10.1242/dev.073056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bult C, Blake J, Smith C, Kadin J, Richardson J. Mouse Genome Database (MGD) 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D801–D806. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masden TB, Taela A, Rocha M, da. Moores DC, Radulescu A. Isolated thoracoschisis with rib agenesis and liver herniation: a case report. Am. J. Case Rep. 2019;20:1915–1919. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.919125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lek M, et al. Exome Aggregation Consortium. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60.706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S, et al. Transcriptome profiling of a multiple recurrent muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder by deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2014;9:91466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao Y, Li G. Role of EFNA1 in tumorigenesis and prospects for cancer therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;130:110567. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toma MI, et al. Lack of ephrin receptor A1 is a favorable independent prognostic factor in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:102262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warrington NM, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies nine novel loci for 2D:4D finger ratio. a putative retrospective biomarker of testosterone exposure in utero. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:2025–2038. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eeles RA, et al. Identification of 23 new prostate cancer susceptibility loci using the iCOGS custom genotyping array. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:385–391. doi: 10.1038/ng.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popiołek. A. et al. Prostate-specific antigen and testosterone levels as biochemical indicators of cognitive function in prostate cancer survivors and the role of diabetes. J. Clin. Med.10, 5307 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Liu J, Welm B, Boucher KM, Ebbert MTW, Bernard PS. TRIM29 functions as a tumor suppressor in nontumorigenic breast cells and invasive ER+ breast cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;180:839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmbos PL, et al. ATDC/TRIM29 drives invasive bladder cancer formation through miRNA-mediated and epigenetic mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2015;75:5155–5166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Z, et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals variants in ARID1A. GPRC5A and MLL2 driving self-renewal of human bladder cancer stem cells. Eur. Urol. 2017;71:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu H, Hao L, Yang H, Chen J, Liu J. miRNA-34a suppresses colon carcinoma proliferation and induces cell apoptosis by targeting SYT1. Int J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019;12:2887–2897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurung P, et al. Prognostic DNA methylation biomarkers in high-risk non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review to identify loci for prospective validation. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2020;6:683–697. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitchen MO, et al. Methylation of HOXA9 and ISL1 predicts patient outcome in high-grade non-invasive bladder cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:0137003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manichaikul A, Palmer AA, Sen Ś, Broman KW. Significance thresholds for quantitative trait locus mapping under selective genotyping. Genetics. 2007;177:1963–1966. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das S, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1284–1287. doi: 10.1038/ng.3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies via imputation of genotypes: Supplementary Methods Imputation of missing genotypes Imputation of completely missing SNPs. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute Inc. 2013. SAS 9.4 Language Reference. Cary. NC: SAS Institute.

- 29.Pruim. R. J. et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics26, 2336–2337 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Szklarczyk D, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks. integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:447–452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wullweber A, et al. Bladder tumor subtype commitment occurs in carcinoma in situ driven by key signaling pathways including ECM Remodeling. Cancer Res. 2021;81:1552–1566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li B, Ruotti V, Stewart RM, Thomson JA, Dewey CN. RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics. 2009;26:493–500. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Data

Data Availability Statement

GWAS generated and analyzed data during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files. GWAS data are deposited at NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog with accession ID: GCST90132313. EFNA1 DNA sequencing data are deposited in GeneBank (BankIt) with the following accession numbers: OP312051; OP312052; OP312053; OP312054; OP312055; OP312056; OP312057; OP312058; OP312059; OP312060; OP312061; OP312062; OP312063. The raw RNA-sequencing data of the 38 Muscular Invasive Urothelial carcinomas are deposited at NCBI in Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the following BioProject accession: PRJNA882449. The raw RNA-sequencing data of mouse embryonic urinary bladder are deposited at GEO with the accession id: GSE190641. The raw RNA-sequencing data of human embryonic and fetal urinary bladder and genital tissue are deposited at EMBL-EBI expression atlas with the following accession id: E-MTAB-6592. The raw RNA-sequencing data of cancer cell lines are obtained from EMBL-EBI expression atlas with the following accession id: E-MTAB-2770, PolyA RNA-sequencing of the mature urinary bladder is obtained from GEO with the following accession id: GSM1067793.