Abstract

Background/Aims

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) risk for non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) compared with warfarin is largely unknown. We aimed to determine the risk of overall and post-polypectomy GIB for NOACs and warfarin.

Methods

Using the Korean National Health Insurance database, we created a cohort of patients who were newly prescribed NOACs or warfarin between July 2015 and December 2017 using propensity score matching (PSM). Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test was performed to compare the risk of overall and post-polypectomy GIB between NOACs (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban) and warfarin. Post-polypectomy GIB was defined as bleeding within 1 month after gastrointestinal endoscopic polypectomy.

Results

Out of 234,206 patients taking anticoagulants (187,687 NOACs and 46,519 warfarin), we selected 39,764 pairs of NOACs and warfarin users after PSM. NOACs patients showed significantly lower risk of overall GIB than warfarin patients (log-rank P<0.001, hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.78–0.94; P=0.001). Among NOACs, apixaban showed the lowest risk of GIB. In the subgroup of 7,525 patients who underwent gastrointestinal polypectomy (lower gastrointestinal polypectomy 93.1%), 1,546 pairs were chosen for each group after PSM. The NOACs group showed a high risk of post-polypectomy GIB compared with the warfarin group (log-rank P=0.001, hazard ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.16–3.33; P=0.012).

Conclusions

This nationwide, population-based study demonstrates that risk of overall GIB is lower for NOACs than for warfarin, while risk of post-polypectomy GIB is higher for NOACs than for warfarin.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal hemorrhages, Warfarin, Anticoagulants, Polyps

INTRODUCTION

Although warfarin is highly effective in the prevention of ischemic stroke and systemic thromboembolism, there are several challenges to its use in clinical practice. Due to the long half-life of the agent, onset and offset of the drug effect are slow, taking 48–72 hours for complete effect to occur after administration [1]. This slow onset and offset may raise concerns about the risk of bleeding or thrombosis when patients need to hold warfarin before and after undergoing an endoscopic or surgical procedure. Furthermore, warfarin requires frequent blood monitoring to adjust the appropriate drug dose for adequate anticoagulant effect, which can differ by more than 20 times among patients, probably due to the drug’s interaction with food and individual genetic variation [1]. These drawbacks prompted the quest for the development of alternative drugs.

Since the Food and Drug Administration’s approval in 2010, the use of the non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs), including dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban, has been rapidly catching up to warfarin with non-inferior efficacy [2]. This change has been brought about by the convenience of fixed-dose regimens of NOACs with no requirement for routine laboratory monitoring owing to their predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [3,4]. However, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) in the use of NOACs is still in question. In pivotal trials for the efficacy and safety of NOACs, dabigatran and rivaroxaban had a higher risk of GIB than warfarin [5,6]. Data from real-world studies showed a low or similar risk of GIB in NOACs compared with warfarin [7-9]. Furthermore, the risk of GIB in NOACs over warfarin after gastrointestinal endoscopic polypectomy has yet to be fully evaluated because of the low number of anticoagulant users who undergo polypectomy.

Health administrative databases which routinely collect the health data of many subjects can provide important information about the clinical outcomes of rare events from real-world settings. The National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), an obligatory single-payer health insurance system in Korea, has a data warehouse that collects required information on insurance eligibility covering the entire population of over 50 million [10]. Thus, using NHIS data, we aimed to determine the risk of overall and post-polypectomy GIB associated with the use of NOACs and warfarin.

METHODS

1. Data Sources, Study Design, and Population

This retrospective cohort study used a nationwide, population-based database (NHIS) which contains demographic data (age and sex), provider information, pharmaceutical prescriptions, procedures, and diagnostic codes defined by the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10). Pharmaceutical prescriptions and procedures were coded with the Korean original codes. We identified all patients 18 years of age or over who started taking dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban or warfarin between July 2015 and December 2017 defined as the overall cohort (Fig. 1A). The minimum duration of anticoagulant use was 30 days. We excluded patients with a previous GIB diagnosis or those who had used any oral anticoagulants before the index (drug start) date and those who were prescribed more than one type of anticoagulant during the study period. Index diseases for anticoagulants were based on the ICD-10 diagnosis code for the 12 months before their index date. We classified patients into NOACs or warfarin groups based on their first filled prescription. Follow-up was considered to have ended when patients had GIB or if there was a disruption of continuous prescription as defined by the absence of a new prescription by the end of the 45-day period from the last actual refill date [8]. The last date of follow-up was December 31, 2017.

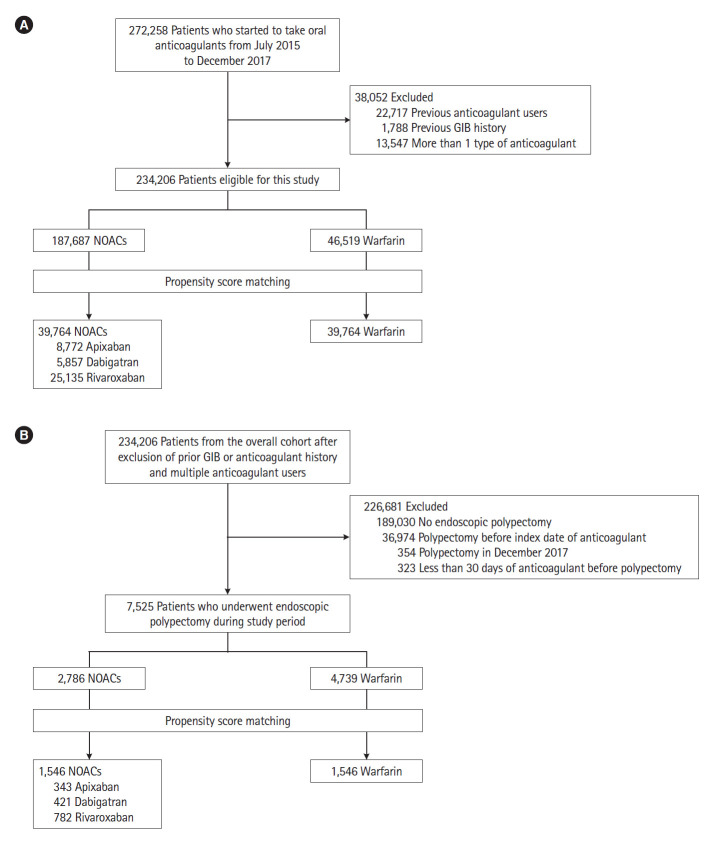

Fig. 1.

Study flow of patients treated with anticoagulants. (A) Overall patients (the overall cohort) and (B) subgroup patients who underwent polypectomy (post-polypectomy cohort). GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding; NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants.

Next, we selected a subgroup of patients during the same study period among the cohort who had inpatient or outpatient polypectomy procedures which were coded with a classification of upper and lower gastrointestinal polypectomy (post-polypectomy cohort) (Fig. 1B). Procedure codes in the NHIS database showed good agreement with data from medical charts [11]. For this subgroup, we excluded patients who underwent polypectomy in December 2017, due to a short follow-up period (< 30 days), and those who were prescribed anticoagulants less than 30 days before the polypectomy date. We also excluded patients who had undergone polypectomy before the index date of medication. We included endoscopic mucosal resection as polypectomy but excluded endoscopic submucosal dissection because endoscopic submucosal dissection was not frequently performed and not completely reimbursed by the NHIS. As this study did not contain identifying patient information, the Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University Hospital waived consent obtainment and approved the study (IRB No. KNUH2016-05-001).

2. Study Outcomes and Variables of Interest

The primary endpoint of this study was the occurrence of any GIB after the index date during the study period. The secondary endpoints included the risk of upper GIB, lower GIB, and GIB requiring blood transfusion. These endpoints were also applied to post-polypectomy cohort. Post-polypectomy GIB was defined as bleeding within 30 days after gastrointestinal endoscopic polypectomy. As the NHIS database does not have detailed clinical information, such as laboratory results and endoscopic reports, a GIB event was defined as the ICD-10 code for GIB, procedure code for endoscopic hemostasis or code for transfusion (Supplementary Table 1). Bleeding location was identifiable by the ICD-10 code of GIB with bleeding site (stomach, duodenum, small bowel, and colon) indicated and upper or lower gastrointestinal endoscopic hemostasis. For instance, upper GIB was defined as the ICD-10 code for bleeding of the stomach and duodenum or as the procedure code for endoscopic hemostasis of upper GIB being applied. Lower GIB was defined as the ICD-10 code of bleeding at the jejunum, ileum, and colon or the procedure code for endoscopic hemostasis of lower GIB being applied. For post-polypectomy bleeding, any GIB was thought to have originated from the initial endoscopic procedure [12].

Independent variables of interest included age, sex, index diseases of anticoagulants, the Charlson comorbidity index with comorbidities, and drugs used concomitantly during the study period. We evaluated comorbidities based on the components of the Charlson comorbidity index: myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, peptic ulcer disease, mild-to-severe liver disease, diabetes mellitus with and without chronic complications, paraplegia, moderate to severe renal disease, immune-mediated disease and malignant or metastatic cancer [13]. We assessed the use of concomitant drugs: aspirin, antiplatelet agents including clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugrel, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and heparin.

3. Statistical Analysis

We performed a one-to-one propensity score matching (PSM) analysis between the NOACs (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban) and warfarin groups based on the estimated propensity scores of each patient. Each patient who received NOACs whose propensity score was closest on the logit scale within a specified range (≤ 0.1 of the pooled standardized mean difference [SMD] of estimated logits) was chosen for matching to a patient who received warfarin. Patients’ age, sex, index diseases of anticoagulants, the Charlson comorbidity index with comorbidities, and drugs were included for the calculation of PSM.

Observed GIB rates and survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard model was used to obtain the hazard ratio (HR) for NOACs with warfarin as the reference. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Treated with Anticoagulants in the Overall Cohort

We identified a total of 272,258 patients who started taking warfarin or NOACs from July 2015 to December 2017. Among them, 38,052 patients who were previous anticoagulant users, had a previous GIB diagnosis or were taking more than 1 type of anticoagulant were excluded. Among 234,206 patients, 187,687 patients received NOACs and 46,519 received warfarin. By one-to-one PSM, we selected 39,764 pairs of NOACs users (8,772 taking apixaban, 5,857 taking dabigatran, and 25,135 taking rivaroxaban) and warfarin users (Fig. 1A). Before the PSM, sex, age, the distribution of index disease, comorbidities, and concurrent medications showed significant difference between the NOACs and warfarin groups (Table 1). The NOACs group was older than the warfarin group (mean age ± standard deviation [SD], 70.7 ± 10.8 years vs. 64.3 ± 14.9 years; SMD, 0.49) and showed a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation (43.2% vs. 37.5%; SMD, 0.12), connective tissue disease (6.9% vs. 3.7%; SMD, 0.15) and use of NSAIDs (84.1% vs. 71.8%; SMD, 0.30). Compared to the NOACs group, the warfarin group showed a higher prevalence of valvular heart disease (4.9% vs. 1.7%; SMD, 0.18), myocardial infarction (5.0% vs. 2.6%; SMD, 0.12), heart failure (24.9% vs. 18.2%; SMD, 0.16), peripheral artery disease (9.6% vs. 5.8%; SMD, 0.14), moderate to severe renal disease (11.0% vs. 2.9%; SMD, 0.32) and use of heparin (51.7% vs. 16.6%; SMD, 0.80). After PSM, the patient distributions were well balanced (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients in the Overall Cohort Before and After Propensity Score Matching

| Variable | Before matching |

After matching |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin (n=46,519) | NOACs (n=187,687) | Standardized mean difference | Warfarin (n = 39,764) | NOACs (n = 39,764) | Standardized mean difference | ||

| Male sex | 27,415 (58.9) | 73,275 (39.0) | 0.406 | 21,998 (55.3) | 23,067 (58.0) | 0.040 | |

| Age (yr) | 64.3 ± 14.9 | 70.7 ± 10.8 | 0.490 | 65.5 ± 14.6 | 66.5 ± 13.3 | 0.058 | |

| Index disease | |||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 17,445 (37.5) | 80,993 (43.2) | 0.115 | 16,738 (42.1) | 19,108 (48.1) | 0.120 | |

| Pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis | 4,183 (9.0) | 22,029 (11.7) | 0.090 | 4,060 (10.2) | 4,947 (12.4) | 0.070 | |

| Valvular heart | 2,272 (4.9) | 3,248 (1.7) | 0.177 | 1,297 (3.3) | 1,276 (3.2) | 0.003 | |

| Others | 22,619 (48.6) | 81,417 (43.4) | 0.107 | 18,742 (47.1) | 15,713 (39.5) | 0.154 | |

| CCI score | 2.7 ± 2.6 | 2.4 ± 2.3 | 0.118 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 2.6 ± 2.6 | 0.015 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 2,329 (5.0) | 4,950 (2.6) | 0.124 | 1,715 (4.3) | 1,615 (4.1) | 0.013 | |

| Heart failure | 11,594 (24.9) | 34,200 (18.2) | 0.163 | 9,327 (23.5) | 9,320 (23.4) | < 0.001 | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 4,466 (9.6) | 10,916 (5.8) | 0.142 | 3,155 (7.9) | 2,896 (7.3) | 0.025 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8,993 (19.3) | 33,621 (17.9) | 0.036 | 7,783 (19.6) | 7,784 (19.8) | 0.006 | |

| Dementia | 4,555 (9.8) | 19,990 (10.7) | 0.028 | 4,173 (10.5) | 4,425 (11.1) | 0.020 | |

| COPD | 14,325 (30.8) | 58,755 (31.3) | 0.011 | 12,384 (31.1) | 12,557 (31.6) | 0.009 | |

| Connective tissue disease | 1,703 (3.7) | 13,008 (6.9) | 0.146 | 1,607 (4.0) | 1,368 (3.4) | 0.032 | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 9,407 (20.2) | 45,989 (24.5) | 0.103 | 8,324 (20.9) | 8,171 (20.5) | 0.009 | |

| DM without chronic complications | 13,480 (29.8) | 58,858 (31.4) | 0.035 | 11,758 (29.6) | 11,560 (29.1) | 0.011 | |

| DM with chronic complications | 6,058 (13.0) | 19,521 (10.4) | 0.082 | 4,656 (11.7) | 4,311 (10.8) | 0.027 | |

| Paraplegia | 1,750 (3.8) | 4,009 (2.1) | 0.096 | 1,484 (3.7) | 1,671 (4.2) | 0.024 | |

| Mild liver disease | 11,193 (24.1) | 44,372 (23.6) | 0.010 | 9,528 (24.0) | 9,614 (24.2) | 0.005 | |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 431 (0.9) | 578 (0.3) | 0.079 | 303 (0.8) | 304 (0.8) | < 0.001 | |

| Moderate or severe renal disease | 5,133 (11.0) | 5,448 (2.9) | 0.324 | 3,050 (7.7) | 3,040 (7.6) | 0.001 | |

| Non-metastatic cancer or hematologic malignancy | 5,059 (10.9) | 20,346 (10.8) | 0.001 | 4,534 (11.4) | 5,272 (13.3) | 0.056 | |

| Metastatic cancer | 1,149 (2.5) | 5,208 (2.8) | 0.019 | 1,114 (2.8) | 1,245 (3.1) | 0.019 | |

| Immune-mediated disease | 18 (0.0) | 39 (0.0) | 0.010 | 12 (0.0) | 10 (0.0) | 0.003 | |

| Medications | |||||||

| Aspirin | 2,792 (6.0) | 12,109 (6.5) | 0.019 | 2,444 (6.1) | 2,291 (5.8) | 0.016 | |

| Clopidogrel | 1,161 (2.5) | 4,219 (2.2) | 0.016 | 975 (2.5) | 903 (2.3) | 0.012 | |

| Ticagrelor | 20 (0.0) | 43 (0.0) | 0.011 | 13 (0.0) | 12 (0.0) | 0.001 | |

| Prasugrel | 10 (0.0) | 23 (0.0) | 0.007 | 9 (0.0) | 11 (0.0) | 0.003 | |

| NSAIDs | 33,391 (71.8) | 157,858 (84.1) | 0.301 | 29,338 (73.8) | 28,773 (72.4) | 0.032 | |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 26,158 (56.2) | 108,720 (57.9) | 0.034 | 22,060 (55.5) | 21,799 (54.8) | 0.013 | |

| Heparin | 24,069 (51.7) | 31,230 (16.6) | 0.797 | 17,483 (44.0) | 17,515 (44.0) | 0.002 | |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

2. Hazard risk of GIB in the Overall Cohort

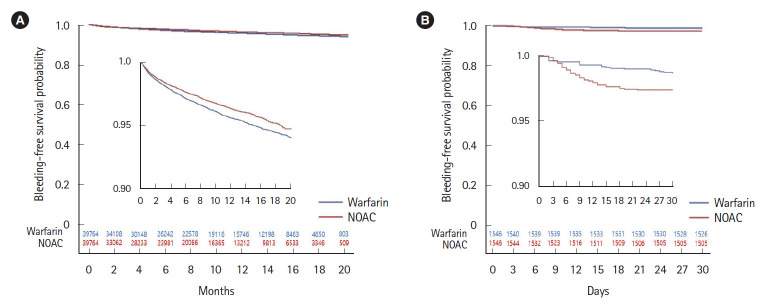

The incidences of GIB in the overall cohort were described in Supplementary Table 2. A total of 2,570 (3.23%) patients showed overall GIB associated with anticoagulants during study period. GIB occurred in 1,440 (3.62%) patients taking warfarin and 1,130 (2.84%) patients taking NOACs. The risk of overall GIB was lower for the use of NOACs compared with the use of warfarin (HR, 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.94; P=0.001) (Table 2). In subtypes of NOACs, apixaban (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64–0.97; P=0.023) showed the lowest risk followed by rivaroxaban (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77–0.97; P=0.014) while there was no significant difference for dabigatran compared with warfarin (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.72–1.16; P=0.467) (Table 2). In the Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative risk of overall GIB, there was a significantly higher risk in warfarin than in NOACs (log-rank P<0.001) (Fig. 2A) and in subtypes of NOACs (log-rank P<0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1A).

Table 2.

Hazards for GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs over Warfarin Group in the Overall Cohort (n=79,528)

| Variable | All GIB (n=2,570) |

Upper GIB (n=764) |

Lower GIB (n=322) |

GIB with transfusion (n = 1,446) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Warfarin | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| NOACs | 0.86 (0.78–0.94) | 0.001 | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | 0.194 | 0.99 (0.80–1.24) | 0.958 | 0.73 (0.65–0.81) | < 0.001 |

| Apixaban | 0.78 (0.64–0.97) | 0.023 | 0.95 (0.74–1.22) | 0.668 | 0.96 (0.65–1.41) | 0.830 | 0.67 (0.55–0.81) | < 0.001 |

| Dabigatran | 0.92 (0.72–1.16) | 0.467 | 0.83 (0.62–1.11) | 0.213 | 1.32 (0.90–1.92) | 0.155 | 0.62 (0.49–0.78) | < 0.001 |

| Rivaroxaban | 0.86 (0.77–0.97) | 0.014 | 0.92 (0.78–1.08) | 0.292 | 0.93 (0.72–1.20) | 0.557 | 0.77 (0.69–0.87) | < 0.001 |

| Warfarin without aspirin | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Warfarin plus aspirin | 0.99 (0.81–1.24) | 0.996 | 0.80 (0.52–1.24) | 0.318 | 1.58 (0.94–2.63) | 0.083 | 1.00 (0.76–1.32) | 0.985 |

| NOACs without aspirin | 0.83 (0.77–0.90) | < 0.001 | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 0.088 | 1.02 (0.81–1.28) | 0.851 | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) | < 0.001 |

| NOACs plus aspirin | 1.12 (0.90–1.39) | 0.320 | 1.21 (0.82–1.78) | 0.344 | 1.16 (0.61–2.20) | 0.654 | 0.88 (0.65–1.21) | 0.440 |

| Warfarin without antiplateleta | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Warfarin plus antiplateleta | 1.02 (0.85–1.24) | 0.781 | 0.80 (0.54–1.19) | 0.270 | 1.43 (0.88–2.34) | 0.148 | 1.06 (0.83–1.35) | 0.665 |

| NOACs without antiplateleta | 0.83 (0.76–0.90) | < 0.001 | 0.87 (0.75–1.01) | 0.065 | 1.01 (0.80–1.27) | 0.946 | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) | < 0.001 |

| NOACs plus antiplateleta | 1.11 (0.91–1.35) | 0.309 | 1.23 (0.87–1.74) | 0.242 | 1.27 (0.74–2.20) | 0.386 | 0.89 (0.67–1.17) | 0.396 |

| Warfarin without PPIs | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Warfarin plus PPIs | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) | 0.001 | 0.79 (0.65–0.96) | 0.019 | 0.89 (0.66–1.21) | 0.474 | 0.82 (0.72–0.94) | 0.005 |

| NOACs without PPIs | 0.86 (0.77–0.97) | 0.011 | 0.90 (0.73–1.10) | 0.304 | 1.14 (0.83–1.57) | 0.405 | 0.77 (0.66–0.89) | < 0.001 |

| NOACs plus PPIs | 0.70 (0.63–0.78) | < 0.001 | 0.74 (0.60–0.90) | 0.003 | 0.79 (0.57–1.08) | 0.138 | 0.57 (0.49–0.66) | < 0.001 |

Antiplatelets include clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugrel.

GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding; NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for gastrointestinal bleeding risk in non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) versus warfarin. (A) Overall cohort (log-rank P<0.001). (B) Post-polypectomy cohort (log-rank P=0.001). The inside graph is an enlarged version of the original one.

However, concurrent administration with aspirin and antiplatelets, such as clopidogrel, ticagrelor and prasugrel, negated the beneficial effect of NOACs over warfarin. Whereas NOACs without aspirin or antiplatelets showed significantly lower GIB risk than warfarin without those medications, this difference in GIB was not observed with NOACs plus aspirin (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.90–1.39; P=0.320) or NOACs plus antiplatelets (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.91–1.35; P=0.309) (Table 2).

The significantly lower risk with NOACs (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65–0.81; P<0.001) over warfarin was also observed in GIB cases requiring transfusion (n = 1,446) and this benefit was observed in all subtypes of NOACs (Table 2). In the subgroup analysis for upper (n = 764) and lower (n = 322) GIB, there was no significant difference between NOACs and warfarin users.

Co-medication with PPIs significantly reduced the risk of overall GIB and GIB requiring transfusion in both warfarin and NOACs group (Table 2). In subgroup analysis, PPIs reduced upper GIB, but not lower GIB risk.

3. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Treated with Anticoagulants after Polypectomy

Among 234,206 patients first receiving NOACs or warfarin from July 2015 to December 2017 in the overall cohort, 7,525 patients who underwent first polypectomy after anticoagulant medication were included (Fig. 1B). Among them, 2,786 and 4,739 patients received NOACs and warfarin, respectively. By one-to-one PSM with a SMD of estimated logits ≤ 0.1 between groups, we selected 1,546 pairs of NOACs and warfarin users (343 taking apixaban, 421 taking dabigatran, and 782 taking rivaroxaban) (Fig. 1B). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic polypectomy was performed in 102 (6.6%) from warfarin and 85 (5.5%) from the NOACs group with no significant difference. Lower gastrointestinal polypectomy was performed in 1,444 (93.4%) from the warfarin group and 1,461 (94.5%) from the NOACs group with no significant difference (Table 3). Baseline characteristics showing high SMD between groups (delta > 0.1) were well controlled after PSM (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics of Subgroup Patients with Gastrointestinal Polypectomy Before and After Propensity Score Matching

| Variable | Before matching |

After matching |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin (n=4,739) | NOACs (n=2,786) | Standardized mean difference | Warfarin (n = 1,546) | NOACs (n = 1,546) | Standardized mean difference | ||

| Male sex | 3,501 (73.9) | 2,012 (72.2) | 0.037 | 1,147 (74.2) | 1,145 (74.1) | 0.003 | |

| Age (yr) | 66.7 ± 8.9 | 70.0 ± 8.1 | 0.382 | 68.2 ± 8.7 | 69.2 ± 8.8 | 0.072 | |

| CCI score | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 2.9 ± 2.1 | 0.204 | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 0.015 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 155 (3.3) | 119 (4.3) | 0.053 | 64 (4.1) | 64 (4.1) | 0.000 | |

| Heart failure | 1,697 (35.8) | 1,121 (40.2) | 0.091 | 584 (37.8) | 592 (38.3) | 0.011 | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 420 (8.9) | 207 (7.4) | 0.052 | 141 (9.1) | 96 (6.2) | 0.110 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1,071 (22.6) | 860 (30.9) | 0.188 | 478 (30.9) | 475 (30.7) | 0.004 | |

| Dementia | 245 (5.2) | 210 (7.5) | 0.097 | 104 (6.7) | 94 (6.1) | 0.026 | |

| COPD | 1,400 (29.5) | 896 (32.2) | 0.057 | 472 (30.5) | 463 (29.9) | 0.013 | |

| Connective tissue disease | 162 (3.4) | 91 (3.3) | 0.008 | 48 (3.1) | 51 (3.3) | 0.011 | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1,084 (22.9) | 777 (27.9) | 0.115 | 358 (23.2) | 378 (24.5) | 0.030 | |

| DM without chronic complications | 1,527 (32.2) | 1,095 (39.3) | 0.148 | 568 (36.7) | 592 (38.3) | 0.032 | |

| DM with chronic complications | 580 (12.2) | 398 (14.3) | 0.060 | 216 (14.0) | 223 (14.4) | 0.013 | |

| Paraplegia | 54 (1.1) | 58 (2.1) | 0.075 | 29 (1.9) | 26 (1.7) | 0.015 | |

| Mild liver disease | 1,002 (21.1) | 701 (25.2) | 0.095 | 364 (23.5) | 350 (22.6) | 0.021 | |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 19 (0.4) | 9 (0.3) | 0.013 | 5 (0.3) | 5 (0.3) | 0.000 | |

| Moderate or severe renal disease | 348 (7.3) | 109 (3.9) | 0.149 | 66 (4.3) | 69 (4.5) | 0.009 | |

| Non-metastatic cancer or hematologic malignancy | 505 (10.7) | 410 (14.7) | 0.122 | 224 (14.5) | 210 (13.6) | 0.026 | |

| Metastatic cancer | 21 (0.4) | 28 (1.0) | 0.066 | 16 (1.0) | 14 (0.9) | 0.013 | |

| Immune-mediated disease | 1 (0.0) | 0 | 0.021 | 0 | 0 | - | |

| Medications | |||||||

| Aspirin | 649 (13.7) | 252 (9.0) | 0.147 | 153 (9.9) | 155 (10.0) | 0.044 | |

| Clopidogrel | 227 (4.8) | 130 (4.7) | 0.006 | 91 (5.9) | 63 (4.1) | 0.083 | |

| Ticagrelor | 4 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 0.020 | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0.051 | |

| Prasugrel | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - | |

| NSAIDs | 277 (5.8) | 1,050 (37.7) | 0.836 | 265 (17.1) | 276 (17.9) | 0.019 | |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 312 (6.6) | 1,055 (37.9) | 0.812 | 285 (18.4) | 290 (18.8) | 0.008 | |

| Heparin | 45 (0.9) | 52 (1.9) | 0.078 | 23 (1.5) | 18 (1.2) | 0.028 | |

| Endoscopic polypectomy | |||||||

| Upper GI | 323 (6.8) | 193 (6.9) | 0.004 | 102 (6.6) | 85 (5.5) | 0.046 | |

| Lower GI | 4,416 (93.2) | 2,593 (93.1) | 0.004 | 1,444 (93.4) | 1,461 (94.5) | 0.046 | |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; GI, gastrointestinal.

4. Hazard Risk of Post-Polypectomy GIB in Patients Treated with Anticoagulant

The incidences of 30-day GIB in the post-polypectomy cohort were described in Supplementary Table 3. A total of 62 (2.0%) patients who were treated with anticoagulants showed GIB after polypectomy. GIB occurred in 21 (1.4%) patients taking warfarin and 41 (2.7%) patients taking NOACs within 30 days after their procedure. In Table 4, the risk of all post-polypectomy GIB was higher for the use of NOACs compared with the use of warfarin (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.16–3.33; P=0.012). Among the NOACs subtypes, the rivaroxaban showed the significantly higher risk over the warfarin (HR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.21–3.94; P=0.010) while there was no significant difference between the apixaban or dabigatran and the warfarin group. The higher cumulative post-polypectomy GIB risk of NOACs (log-rank P=0.001) (Fig. 2B) and subtypes of NOACs (log-rank P=0.008) (Supplementary Fig. 1B) than warfarin was demonstrated in the Kaplan-Meier analysis. The most GIB in NOACs group was observed within 2 weeks while GIB cases in warfarin group appeared to be distributed throughout 30 days after polypectomy (Fig. 2B). For upper endoscopic polypectomy, the bleeding risk was significantly higher than warfarin only in rivaroxaban (HR, 5.33; 95% CI, 1.27–22.29; P=0.022). The bleeding risk of NOACs after lower endoscopic polypectomy was higher than warfarin (HR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.10–3.42; P=0.023) (Table 4). The risk of rivaroxaban after lower endoscopic polypectomy was significantly higher than warfarin (HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.01–3.74; P=0.047) (Table 4) while other NOACs showed no difference compared with warfarin.

Table 4.

Hazards for Post-Polypectomy GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs over Warfarin (n=3,092)

| Variable | All GIB (n=62) |

Upper GIB (n=9) |

Lower GIB (n=53) |

GIB with transfusion (n = 15) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Warfarin | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| NOACs | 1.97 (1.16–3.33) | 0.012 | 2.45 (0.61–9.79) | 0.206 | 1.93 (1.10–3.42) | 0.023 | 1.52 (0.54–4.26) | 0.431 |

| Apixaban | 1.95 (0.89–4.25) | 0.095 | 1.41 (0.15–13.55) | 0.766 | 2.03 (0.88–4.66) | 0.967 | 1.52 (0.31–7.51) | 0.611 |

| Dabigatran | 1.59 (0.73–3.46) | 0.247 | NA | NA | 1.85 (0.83–4.11) | 0.133 | 1.85 (0.46–7.41) | 0.383 |

| Rivaroxaban | 2.18 (1.21–3.94) | 0.010 | 5.33 (1.27–22.29) | 0.022 | 1.94 (1.01–3.73) | 0.047 | 1.33 (0.38–4.72) | 0.657 |

| Warfarin without aspirin | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Warfarin plus aspirin | 7.10 (2.99–16.85) | < 0.001 | NA | NA | 9.47 (3.76–23.87) | < 0.001 | 4.74 (0.87–25.91) | 0.072 |

| NOACs without aspirin | 2.87 (1.49–5.54) | 0.002 | 2.09 (0.50–8.74) | 0.314 | 3.22 (1.52–6.79) | 0.002 | 2.03 (0.61–6.74) | 0.248 |

| NOACs plus aspirin | 5.36 (2.11–13.61) | < 0.001 | 3.07 (0.32–29.50) | 0.332 | 6.10 (2.17–17.15) | 0.001 | 2.31 (0.26–20.67) | 0.454 |

| Warfarin without antiplateleta | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Warfarin plus antiplateleta | 4.28 (1.81–10.18) | 0.001 | NA | NA | 5.64 (2.24–14.22) | < 0.001 | 2.86 (0.52–15.62) | 0.224 |

| NOACs without antiplateleta | 2.39 (1.22–4.69) | 0.011 | 1.71 (0.38–7.63) | 0.484 | 2.71 (1.26–5.80) | 0.011 | 1.98 (0.60–6.59) | 0.263 |

| NOACs plus antiplateleta | 6.41 (2.88–14.27) | < 0.001 | 4.26 (0.71–25.50) | 0.112 | 7.10 (2.88–17.46) | < 0.001 | 1.61 (0.18–14.43) | 0.669 |

| Warfarin without PPIs | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Warfarin plus PPIs | 3.35 (1.41–7.95) | 0.006 | 4.81 (0.43–53.04) | 0.199 | 2.99 (1.16–7.72) | 0.023 | 2.23 (0.41–12.21) | 0.352 |

| NOACs without PPIs | 2.79 (1.44–5.40) | 0.002 | 8.83 (1.06–73.31) | 0.044 | 2.44 (1.21–4.92) | 0.013 | 2.03 (0.61–6.75) | 0.247 |

| NOACs plus PPIs | 2.93 (1.20–7.16) | 0.019 | NA | NA | 3.41 (1.37–8.49) | 0.008 | 1.10 (0.12–9.86) | 0.931 |

Antiplatelets include clopidogrel, ticagrelor and prasugrel.

GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding; NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; NA, not available.

Concurrent use of aspirin or antiplatelet significantly increased post-polypectomy GIB risk in both warfarin and NOACs group. PPIs co-medication did not reduce post-polypectomy GIB risk. There was no difference between groups in post-polypectomy GIB requiring transfusion (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This nationwide, population-based study comparing the hazard risk for GIB between NOACs and warfarin, using propensity matching analysis, showed that overall GIB risk was lower in NOACs than warfarin, whereas post-polypectomy GIB risk was higher in NOACs than warfarin. This risk varied in different NOACs subtypes: apixaban had a lower risk of all GIB than dabigatran or rivaroxaban in the overall cohort while rivaroxaban had a higher post-polypectomy GIB risk than apixaban or dabigatran. Concomitant medications like aspirin or antiplatelets increased this risk in both the overall and post-polypectomy cohort while PPIs co-therapy with NOACs or warfarin decreased upper GIB risk, but not lower GIB risk in the overall cohort.

In the literature comparing GIB risk between NOACs and warfarin, there are conflicting results, which seem to be related to the design of the studies. Several landmark clinical trials evaluating anticoagulant efficacy for drugs have reported a higher GIB risk in NOACs than in warfarin (although GIB was not the primary endpoint of the studies) [5,6], while retrospective observational studies have shown a lower GIB risk or less severe GIB in NOACs than in warfarin [7,9,14]. Despite uncertainty, this disparity among studies might be associated with how the therapeutic range of warfarin was controlled, which poses a great challenge in clinical practice. Compared to patients in real-world clinical settings, patients treated with warfarin in the randomized trials were much more likely to be strictly monitored, possibly leading to a lower risk of GIB [15]. In contrast, patients in retrospective observational studies had high concentrations of warfarin, which is associated with poorly controlled monitoring; the mean international normalized ratio (INR) was over 3 and more than half of the patients showed a supratherapeutic range of INR resulting in increased risk for GIB [15]. Our finding of excessive GIB risk in the warfarin group over the NOACs group in the general cohort is in line with those retrospective studies supporting the hypothesis that unoptimized warfarin concentration in real clinical practice (increased INR) may have potentiated bleeding from gastrointestinal mucosa in the warfarin group.

However, in the subgroup analysis of bleeding within 30 days after endoscopic polypectomy, we observed a high hazard risk in NOACs compared with warfarin. A Japanese cohort study based on a national inpatient database reported a higher risk of post-endoscopic bleeding in warfarin than NOACs users which is the opposite of our result [12]. We believe that this difference may be attributed to several discrete features of each study. We focused on endoscopic polypectomy regardless of admission status because this procedure is commonly encountered during endoscopy amid the drastically increased volume of endoscopy screenings for cancer or precancerous lesions [16]. In the former study, endoscopic procedures included various kinds of high-risk procedures which were performed only at inpatient settings, with polypectomy or endoscopic mucosal resection accounting for only around 20% of participants [12]. Although the proportion of heparin bridge was not described for each group, heparin use in periprocedural management of anticoagulants might have affected GIB risk in warfarin users because heparin bridge is not recommended under NOACs treatment. Indeed, they did not find a higher risk in warfarin without heparin than in NOACs without heparin. In addition, the former study defined GIB as overt, severe bleeding requiring endoscopic hemostasis or blood transfusion, while the present study included any GIB coded with an ICD-10 diagnosis as a primary outcome. In the subgroup analysis of bleeding requiring blood transfusions, we did not find a higher risk in NOACs than warfarin, which suggests that increased risk in NOACs may be associated with minor GIB after polypectomy.

In contrast, other retrospective observational studies showed no difference between NOACs and warfarin for GIB risk after elective endoscopy [17,18]. One of the studies using a health care organization database reported that the cumulative incidence of GIB was higher in NOACs users compared with warfarin (P=0.03) [17], which is consistent with the results of our study. The exact mechanism underlying the high hazard risk of postpolypectomy GIB in NOACs over warfarin is unknown but may be partially explained by the different onset time of action for the drugs. The rapid onset of NOACs (1–4 hours) may make patients prone to bleeding from mucosal defects when administered soon after resection procedures, while the slow onset of warfarin (at least 48 hours) may allow enough time for resected sites to heal up resulting in a relatively low risk of post-polypectomy bleeding. In that regard, there is no clear consensus in the guidelines on the right time for resuming NOACs after polypectomy [19,20]. However, we surmised again that this increased risk in NOACs over warfarin did not apply to clinically relevant bleeding as we could not observe a difference in GIB requiring blood transfusions (Table 4).

A recent Hong Kong study [21] using a population-based analysis with PSM showed that apixaban was associated with a significantly lower risk of post-colonoscopic polypectomy bleeding than warfarin which appeared to be discrepant with our results. In subgroup analysis with no heparin bridging therapy, however, the study did show that the bleeding risk of post-colonoscopic polypectomy in apixaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban was significantly higher than in warfarin group. Therefore, without heparin effect, the post-polypectomy bleeding risk might be higher in NOACs than in warfarin. Although we could not assess heparin bridge effect due to limitation of the NHIS database, there were few cases of heparin coadministration in post-polypectomy cohort (Table 3) resulting in exclusion of heparin effect. Furthermore, rivaroxaban was significantly associated with high post-polypectomy bleeding risk compared with warfarin in multivariate analysis which was consistent with our results.

There appears to be a notable difference in the bleeding risk among NOACs subtypes. Rivaroxaban and dabigatran showed higher risk of GIB than warfarin while apixaban showed no difference in randomized trials [5,6,22]. One meta-analysis with 43 randomized controlled trials found that rivaroxaban had a significantly high GIB risk while dabigatran and apixaban did not [23]. Retrospective observational studies that compared major bleeding risk or upper GIB risk among NOACs (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban) also reported a higher risk in rivaroxaban than in other NOACs, with apixaban showing the lowest risk [9,24,25]. Likewise, we also found the highest and lowest risk of GIB in rivaroxaban in post-polypectomy cohort and apixaban in overall cohort, respectively. These individual risks for GIB in NOACs subtypes should be kept in mind for use in patients with differing GIB risks.

One of the notable findings in the present study was the effect of concomitant medications on GIB risk. Aspirin and antiplatelet agents, such as clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugrel, intensified GIB risk in NOACs users; the advantage of a lower risk for GIB in NOACs over warfarin disappeared when aspirin or antiplatelets were concomitantly administered. Additionally, the hazard risk of post-polypectomy in NOACs increased when combined with these medications, especially in lower polypectomy. Considering the added risk of NOACs in conjunction with aspirin/antiplatelets, either one may be temporarily held during high-risk lower polypectomies while balancing for the risk for thrombosis.

We found that PPIs coadministration with NOACs reduced the hazard risk of overall GIB (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.63–0.78) compared to NOACs alone (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77–0.97) with warfarin alone as a reference in the general cohort. In subgroup analysis, this was true for GIB requiring blood transfusions and upper GIB. This finding supported the result of a previous study of the US Medicare beneficiary database showing a significantly reduced upper GIB risk in NOACs with PPIs co-therapy [25]. However, we did not observe the protective effect of PPIs for lower GIB, which is in line with previous knowledge demonstrating no beneficial effect of PPIs for preventing lower GIB [26,27]. The protective effect of PPIs was not observed in GIB after polypectomy.

The strength of the present study is the large number of cases from a nationwide, integrated healthcare system, which enabled sufficient statistical power in discriminating the differences in GIB risk among anticoagulant users. The NHIS includes the entire population of South Korea (more than 50 million) with reimbursement claims data from primary care to tertiary hospitals, reflecting real-world clinical practice [10]. For reducing confounders, we excluded anticoagulant exposures and patients with a previous history of GIB before the index medication start date. For the polypectomy group, we included patients who first underwent polypectomy after index medication. The limitations of the study should be noted. First, these selected patients might not be representative of the population intended to be analyzed because of a retrospective design. Second, PSM might not have controlled hidden confounding factors which could impact our results. Third, as we included GIB events and subgroups based on their diagnostic codes, procedures and filled prescriptions, there may have been misclassified or missed cases. Fourth, we could not differentiate between procedure-related and nonprocedure related GIB because we defined any GIB within 30 days after endoscopic polypectomy. Therefore, the post-polypectomy bleeding risk might have been overestimated. Fifth, the database did not provide information on the clinical data such as detailed causes of bleeding or the exact timing of drug cessation or resumption of anticoagulation especially around endoscopic procedures. Sixth, we failed to balance baseline index diseases such as atrial fibrillation and other indications between groups. Therefore, we tried to control this confounding effect on the GIB risk by adjusting index of diseases in Cox proportional hazard model. The differences in the GIB risk between groups remained significant after adjustment of this confounding factor in overall (Supplementary Table 4) and post-polypectomy cohort (Supplementary Table 5). Seventh, there might be a type I error risk as multiple comparison was used. Eighth, because there was no available data on thromboembolic events, when to stop before endoscopy or when to resume after endoscopy in each group, the findings did not allow us to devise optimal periprocedural management strategies for preventing post-polypectomy GIB. Finally, there was a high proportion of subjects who took NSAID in the study (over 70%) (Table 1). If patients had the prescription of NSAID at least once during the study period, they were regarded as taking the medicine. Also, most patients were elderly and had chronic diseases which might explain the high percentage of NSAID history in the subjects.

In conclusion, this population-based comparison study using PSM demonstrates a lower risk of overall GIB but a higher risk of post-polypectomy GIB in NOACs compared with warfarin. However, the risk of post-polypectomy GIB requiring blood transfusion is not different between the groups, suggesting that an increased risk of post-polypectomy GIB in NOACs may apply only to minor bleeding. GIB risk was not same among NOACs subtypes. Concomitant aspirin or antiplatelet administration increases overall GIB and post-polypectomy GIB. PPIs co-therapy with NOACs reduces the risk of GIB in the overall cohort; this benefit of PPIs is observed in the upper gastrointestinal tract and GIB with transfusion but not lower GIB. These findings may help in choosing the optimal NOACs according to patients’ GIB risk and may suggest a need for careful monitoring for GIB after polypectomy in NOACs.

Footnotes

Funding Source

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

Hanmi Pharm. Co., Ltd. provided statistical data analysis only, but it did not have any conflicts of interest for the results of this study. All authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: Pae JY, Kim ES. Data curation: Pae JY, Kim ES, Park MA. Formal analysis: Pae JY, Kim ES, Kim SK, Jung MK, Heo J, Lee JH. Investigation: Kim ES, Park MA. Methodology: Pae JY, Kim ES. Project administration: Kim ES. Resources: Kim ES, Park MA. Software: Park MA. Supervision: Kim SK, Jung MK, Heo J. Validation: Kim SK, Jung MK. Visualization: Pae JY, Kim ES. Writing - original draft: Pae JY. Writing - review and editing: Kim ES, Kim SK, Jung MK, Lee JH. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at the Intestinal Research website (https://www.irjournal.org).

Supplementary Table 1. ICD-10, Procedure and Transfusion Codes for GIB Event

Supplementary Table 2. Incidence of GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs and Warfarin Group in the Overall Cohort (n=79,528)

Supplementary Table 3. Incidence of Post-Polypectomy GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs and Warfarin (n=3,092)

Supplementary Table 4. Adjusted Hazards for GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs over Warfarin Group in the Overall Cohort (n=79,528)

Supplementary Table 5. Adjusted Hazards for Post-Polypectomy GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs over Warfarin (n=3,092)

Supplementary Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier curves for gastrointestinal bleeding risk in non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) subtypes versus warfarin. (A) Overall cohort (log-rank P<0.001). (B) Post-polypectomy cohort (log-rank P=0.008). The inside graph is an enlarged version of the original one.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mega JL, Simon T. Pharmacology of antithrombotic drugs: an assessment of oral antiplatelet and anticoagulant treatments. Lancet. 2015;386:281–291. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirley K, Qato DM, Kornfield R, Stafford RS, Alexander GC. National trends in oral anticoagulant use in the United States, 2007 to 2011. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:615–621. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham NS, Castillo DL. Novel anticoagulants: bleeding risk and management strategies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:676–683. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328365d415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cangemi DJ, Krill T, Weideman R, Cipher DJ, Spechler SJ, Feagins LA. A comparison of the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants or warfarin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:734–739. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham NS, Singh S, Alexander GC, et al. Comparative risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and warfarin: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h1857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adeboyeje G, Sylwestrzak G, Barron JJ, et al. Major bleeding risk during anticoagulation with warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:968–978. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.9.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheol Seong S, Kim YY, Khang YH, et al. Data resource profile: the National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:799–800. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cha JM, Kim HS, Kwak MS, et al. Features of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer and survival times of patients in Korea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:786–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagata N, Yasunaga H, Matsui H, et al. Therapeutic endoscopy-related GI bleeding and thromboembolic events in patients using warfarin or direct oral anticoagulants: results from a large nationwide database analysis. Gut. 2018;67:1805–1812. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niikura R, Yasunaga H, Yamada A, et al. Factors predicting adverse events associated with therapeutic colonoscopy for colorectal neoplasia: a retrospective nationwide study in Japan. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodie MM, Newman JC, Smith T, Rockey DC. Severity of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients treated with direct-acting oral anticoagulants. Am J Med. 2018;131:573.e9–573.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feagins LA, Weideman RA. GI bleeding risk of DOACs versus warfarin: is newer better? Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1675–1677. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph DA, Meester RG, Zauber AG, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: estimated future colonoscopy need and current volume and capacity. Cancer. 2016;122:2479–2486. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tien A, Kwok K, Dong E, et al. Impact of direct-acting oral anticoagulants and warfarin on postendoscopic GI bleeding and thromboembolic events in patients undergoing elective endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanagisawa N, Nagata N, Watanabe K, et al. Post-polypectomy bleeding and thromboembolism risks associated with warfarin vs direct oral anticoagulants. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1540–1549. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i14.1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan FKL, Goh KL, Reddy N, et al. Management of patients on antithrombotic agents undergoing emergency and elective endoscopy: joint Asian Pacific Association of Gastroenterology (APAGE) and Asian Pacific Society for Digestive Endoscopy (APSDE) practice guidelines. Gut. 2018;67:405–417. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Acosta RD, Abraham NS, et al. The management of antithrombotic agents for patients undergoing GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau LH, Guo CL, Yip TC, et al. Risks of post-colonoscopic polypectomy bleeding and thromboembolism with warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants: a population-based analysis. Gut. 2022;71:100–110. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holster IL, Valkhoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa E. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:105–112. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohsaka S, Murata T, Izumi N, Katada J, Wang F, Terayama Y. Bleeding risk of apixaban, dabigatran, and low-dose rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in Japanese patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a propensity matched analysis of administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1955–1963. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1374935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Association of oral anticoagulants and proton pump inhibitor cotherapy with hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. JAMA. 2018;320:2221–2230. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanas Á, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Arguedas Y, et al. Risk of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:906–912. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Washio E, Esaki M, Maehata Y, et al. Proton pump inhibitors increase incidence of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory druginduced small bowel injury: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:809–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. ICD-10, Procedure and Transfusion Codes for GIB Event

Supplementary Table 2. Incidence of GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs and Warfarin Group in the Overall Cohort (n=79,528)

Supplementary Table 3. Incidence of Post-Polypectomy GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs and Warfarin (n=3,092)

Supplementary Table 4. Adjusted Hazards for GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs over Warfarin Group in the Overall Cohort (n=79,528)

Supplementary Table 5. Adjusted Hazards for Post-Polypectomy GIB in Propensity Score-Matched Patients Treated with NOACs over Warfarin (n=3,092)

Supplementary Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier curves for gastrointestinal bleeding risk in non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) subtypes versus warfarin. (A) Overall cohort (log-rank P<0.001). (B) Post-polypectomy cohort (log-rank P=0.008). The inside graph is an enlarged version of the original one.