Abstract

Controlling and understanding the Cu-catalyzed homocoupling reaction is crucial to prompt the development of efficient Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. The presence of a coordinating base (hydroxide and methoxide) enables the B-to-Cu(II) transmetalation from aryl boronic acid to CuIICl2 in methanol, through the formation of mixed Cu-(μ-OH)-B intermediates. A second B-to-Cu transmetalation to form bis-aryl Cu(II) complexes is disfavored. Instead, organocopper(II) dimers undergo a coupled transmetalation-electron transfer (TET) allowing the formation of bis-organocopper(III) complexes readily promoting reductive elimination. Based on this mechanism some guidelines are suggested to control the undesired formation of homocoupling product in Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.

Keywords: transmetalation, Cu-catalysis, cross-coupling, homocoupling, mechanism, DFT, cyclic voltammetry, boronic acid

1. Introduction

Metal-catalyzed coupling reactions are a staple of organic synthesis as they allow the controlled extension of the carbon backbone of molecules. One of the first historically described coupling reactions was reported by Ullman at the beginning of the last century (1901) to couple two identical aryl halides (homocoupling) in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of Cu(0) [1,2,3,4]. While Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions are among the most used nowadays, Cu catalysis proved to be a nice complement [5] and is particularly interesting to catalyze C-C and C-heteroatom bond formations [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

In the last decade, several protocols have been disclosed describing that mild conditions and low catalyst-loadings can perform the homocoupling of boronic acids using Cu salts (Scheme 1A) [6,7,8,9]. Cu-catalyzed homocoupling of boronic acids takes place at room temperature in the presence of a weak base such as K2CO3 (Scheme 1A) using CuIICl2 or CuICl as catalyst precursors [7].

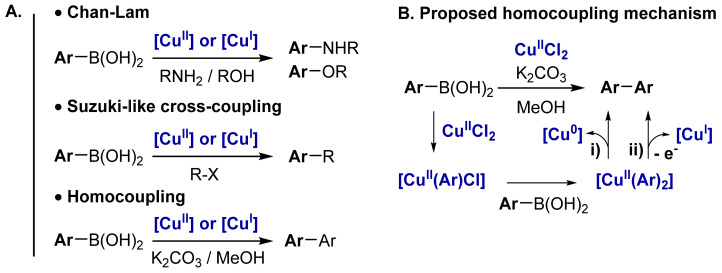

Scheme 1.

(A) Cu-catalyzed homo- and cross-coupling of aryl-boronic acids. (B) Currently proposed mechanisms of the Cu-catalyzed homocoupling of arylboronic acid (ArB(OH)2) in the presence of a base and current state-of-art catalytic cycle involving two successive B-to-Cu transmetalations and subsequent reductive elimination [6,7,8,9,21]. See Scheme 3 for the updated mechanism including the conclusion of the present work.

Controlling and understanding the Cu-catalyzed homocoupling reaction is of high interest (i) to enable efficient formation of symmetrical biphenyl compounds under mild conditions but also (ii) to disfavor this process in the case of Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Deciphering the mechanism of homocoupling reactions is thus crucial to prompt the development of efficient Cu-catalyzed Cham-Lan [22,23,24,25,26] or Cu-catalyzed Suzuki-liked cross-couplings (Scheme 1A) [10,11]. By analogy with the established mechanism for Pd-catalyzed oxidative coupling of boronic acids [27,28], it was proposed that the Cu-catalyzed homocoupling of boronic acid takes place through two successive transmetalations on Cu(II) followed by (i) direct reductive elimination to yield Cu(0) or (ii) one-electron oxidation into Cu(III) and subsequent reductive elimination to yield Cu(I) (Scheme 1B) [6,7,8,9,21]. However, there is no evidence to support these mechanisms. Moreover, the role played by the base was not fully clarified. Indeed, starting from Cu(I), no base is required for the reaction to proceed [15], but the addition of a base is essential starting from Cu(II) [7]. Herein, we report evidence for an alternative homocoupling reaction pathway involving successive B-to-Cu and Cu-to-Cu transmetalation steps.

The mechanism of the CuIICl2-catalyzed homocoupling reaction of arylboronic acids in methanol under inert atmosphere was investigated experimentally using a combination of NMR, cyclic voltammetry, conductimetry pH-metry, and kinetics monitoring. The experimental insights were complemented by the exploration of reaction pathways computed at the DFT level. In particular, the effect of the added base and the involvement of higher-order Cu intermediates are clarified.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Cu-Catalyzed Homocoupling Reaction: Effect of Cu on Selectivity

The stoichiometric reaction of CuIICl2 (10 mM) with 2 equiv of para-fluorophenylboronic acid (p-F-C6H4)B(OH)2 (I) was monitored using 19F NMR in MeOH (Scheme 2). The NMR tube was prepared under inert atmosphere to avoid the oxidative regeneration of Cu(II) from reduced Cu complexes and, thereof, the subsequent oxidative coupling (Figure S1). In MeOH, in the absence of an added base, (p-F-C6H4)B(OH)2 (−112.2 ppm) is stable and no decomposition reaction was observed after 5 h at r.t. (Figure S2).

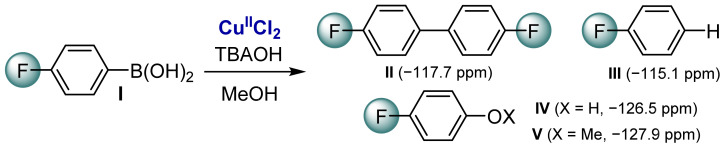

Scheme 2.

Stoichiometric reaction of [CuIICl2] with (p-F-C6H4)B(OH)2 (I) in methanol in the presence of tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBAOH). The reaction yields to the formation of the homocoupling product II, the proto-demetallation product III, and the oxidation products IV and V.

Tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBAOH) was used as a model base for this reaction since it is soluble in methanol and allows us to separate the effect of the base from the ones related to a coordinating counter-cation. In the presence of 20 equiv of (p-F-C6H4)B(OH)2 and 12 equiv of TBAOH, the signal of the boronic acid reagent (I) decreased rapidly and several new signals appeared at −117.7, −115.1, −126.5, and −127.9 ppm. They correspond to the homocoupling product II, the product of the boronic acid protodemetalation III, the phenol IV, and the ether V oxidation products of the boronic acid, respectively (Scheme 2 and Figure S3). All signals were attributed by addition of a small amount of each pure product in the NMR tube.

Since the boron derivative is stable in the absence of CuIICl2, even in the presence of a base (Figure S4), protodemetalation is expected to be mediated by Cu. Consequently, the formation of a protodemetalation product is indicative of B-to-Cu transmetalation followed by protonation, while the formation of homocoupling product comes from transmetalation and subsequent reductive elimination.

The ratio of protodemetalation vs. homocoupling products was shown to be highly dependent on the CuIICl2 and added base concentrations. At high CuIICl2 concentration (20 mM), no protodemetalation product was detected, while at low concentration about 20% of the protodemetalation product was observed (Figure S5). This indicates that the kinetics of the homocoupling reaction follows a higher reaction order with respect to Cu(II) than the kinetics of the protodemetalation reaction. This suggests the possible involvement of multinuclear Cu(II) complexes. The concentration of TBAOH was shown to impact the final product distribution: a high base concentration (0.8 equiv with respect to PhB(OH)2) favors the proto-demetallation (Figure S6).

2.2. Cyclic Voltammetry Monitoring of the Homocoupling Reaction

Electrochemical analysis methods were used to monitor the structure of ligandless Cu species under reaction conditions. Cyclic voltammetry is a powerful tool to access the oxidation state of a metal in solution [29] and, consequently, to scrutinize the oxidation state of a catalyst during oxidative or reductive chemical steps [27]. CuIICl2 (2 mM) is characterized in methanol (Figure 1A) by two reduction peaks at 0.25 and −0.75 V vs. the standard calomel electrode (SCE). They respectively correspond to the reduction to Cu(I) and subsequent deposition of Cu(0) at the electrode. The deposited Cu(0) is re-oxidized to Cu(I) at 0 and 0.2 V vs. SCE and Cu(I) to Cu(II) at 0.5 V vs. SCE. The addition of phenylboronic acid does not modify the shape of the voltammogram (Figure S7).

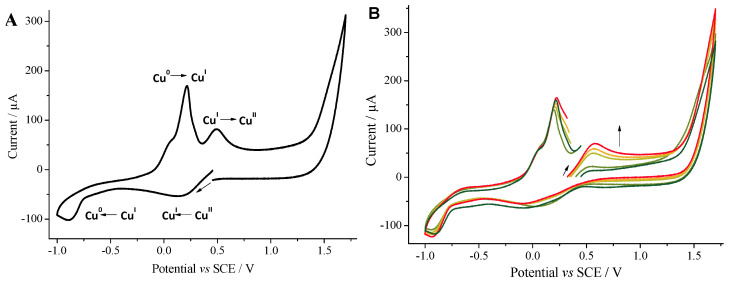

Figure 1.

(A). Cyclic voltammogram toward reduction potentials of a solution of CuIICl2 (2 mM) in MeOH (see Figure S9 for the voltammogram toward oxidation). (B). Cyclic voltammogram toward oxidation potentials monitoring the reduction in Cu(II) to Cu(I) by PhB(OH)2 in the presence of TBAOH CuIICl2 (2 mM, dark green). Addition of PhB(OH)2 (10 mM, light green). Addition of TBAOH (5 mM, apple green) at t = 0. After 20 min (light orange). After 30 min (orange). After 45 min (red). Working electrode: glassy carbon (Ø = 3 mm); scan rate: 0.5 V s−1; supporting electrolyte: nBu4NBF4 (0.3 M); recorded at ambient temperature starting at the open circuit potential (OCP).

Upon addition of TBAOH (6 equiv) in the presence of PhB(OH)2 (10 equiv), the reduction peak related to Cu(II) disappears progressively (Figure S8), while the oxidation peak Ox3, proportional to the concentration of Cu(I), is increasing (Figure 1B). This highlights the formation of Cu(I) and the consumption of Cu(II). In addition, since the reduction in Cu(I) can only originate from reductive elimination, the variation of the concentration of Cu(I) with time relates to the kinetics of the coupling reaction.

To gain more insights into the role played by Cu and the base in the coupling mechanism, we monitored the kinetics of Cu(I) formation using a rotating disk electrode (RDE) [30]. Using this set-up, the potential of the working electrode can be imposed at 0.7 V vs. SCE to enable Cu(I) oxidation. In this condition, the current intensity measured is proportionated to the concentration of Cu(I) in the solution. In the presence of an excess of phenylboronic acid and of base, all kinetic profiles could be fitted by a pseudo first-order law in Cu(I) (Figure S10).

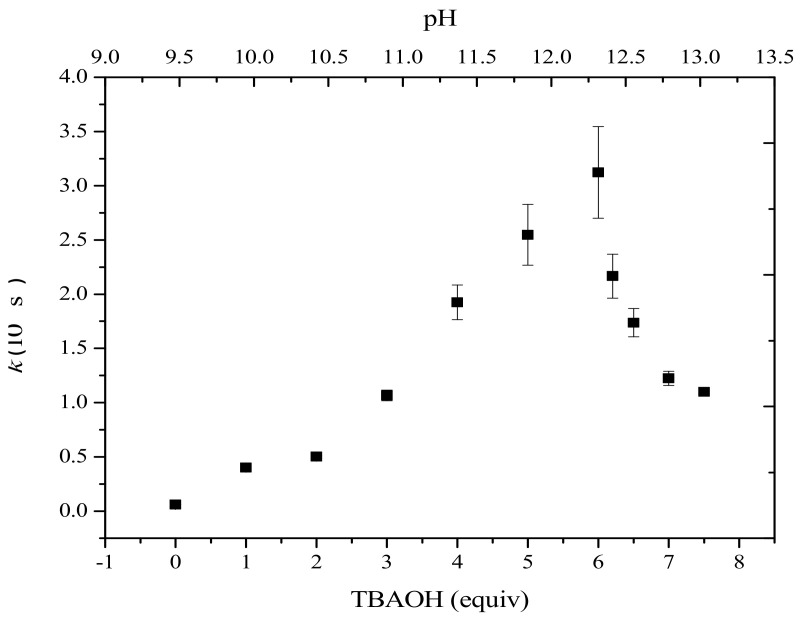

The variation of the apparent rate constant for the formation of Cu(I) with increasing pH is depicted in Figure 2. At low base concentration, the rate of the coupling reaction increased linearly with the concentration of added base, while at higher concentration (6 to 8 equiv), the rate of the reaction decreased sharply. By analogy with the proposed transmetalation mechanism, this bell-shape behavior could be indicative of the formation of a μ-OH-bridged Cu-(μ-OH)-B pre-transmetalation intermediate [31]. In the absence of base, the reaction is apparently limited because of the absence of OH groups, while at high concentration the predominance of Cu hydroxide and boronate species likely hamper the formation of mixed complexes between Cu and B.

Figure 2.

Variation of the pseudo first-order rate constant (k, s−1) of the formation of Cu(I) as estimated by fitting the measured electric current intensity at the polarized rotating electrode (+0.7 V/SCE) as a function of the initial concentration of TBAOH. For each point of the bell-shaped distribution, four experiments were repeated and the standard deviation was estimated (error bars).

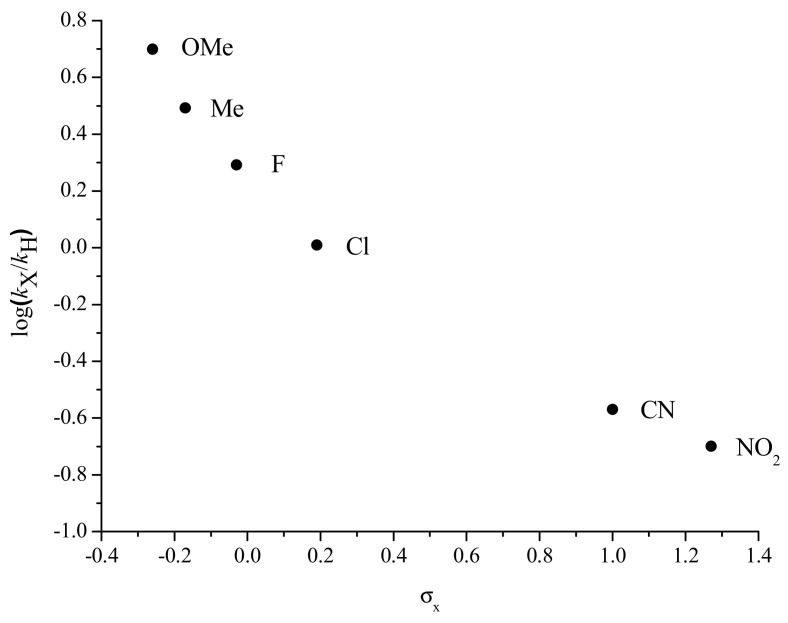

2.3. Electronic Effects on the Kinetics of the Reaction: Hammett Plot

To get more information related to the electronic effects over the rate-determining state (RDS) of the overall coupling process, the kinetics of the Cu(I) formation was monitored for a series of para-substituted phenylboronic acid derivatives. The variations of the pseudo first-order rate constant were obtained at pH = 11 and 12. In both cases, electron-rich boronic acid derivatives react faster than electron-poor ones (Figure 3 and Figure S11). The negative slope of the Hammett plot for the reaction is thus indicative of a decrease in the partial charge on the aromatic ring during the RDS. This is consistent with transmetalation being the rate-determining step. The nonlinearity of the Hammett plot drawn can be indicative of a shift in pre-equilibrium or a change of the RDS step [32].

Figure 3.

Hammett plot for the reduction in Cu(I) (1 mM) by para-substituted phenylboronic derivatives (p-X-C6H4)B(OH)2 (10 mM) (X = MeO, Me, F, Cl, CN and NO2) in the presence of TBAOH (8 mM) (see Figure S11 for the fit of the associated kinetics); kH pseudo first-order rate constant for X = H, kX pseudo first-order rate constant for a substituent X.

2.4. Structure of Cu(II) in Methanol

To interpret the effect of the base concentration on the kinetics of the coupling reaction, we attempted to gather more information regarding the structure of CuIICl2 in MeOH solution as a function of the pH. The conductivity of the CuIICl2 electrolyte in MeOH was studied as a function of the square root of the concentration (Figure S12). The nonlinear plot obtained is typical of a weak electrolyte resulting from a limited dissociation of CuIICl2 into CuCl+ and Cl− in MeOH, in contrast to the behavior reported in water [33]. This agrees with the much lower permittivity of MeOH compared to water [34].

As PhB(OH)2 is a weak acid-in-methanol solution accordingly to Equation (1) (pKa(MeOH) (PhB(OH)2/PhB(OH)3−) = 11.2, see Figure S13), the pH of the methanol solution can be controlled by adding sub-stoichiometric amounts of TBAOH to PhB(OH)2. Thereof, the resulting mixture of boronate PhB(OH)3− and boronic acid acts as a pH buffer.

| PhB(OR)2 (MeOH) + ROH (MeOH) = PhB(OR)3− (MeOH)+ H+ (MeOH); R = H, Me | (1) |

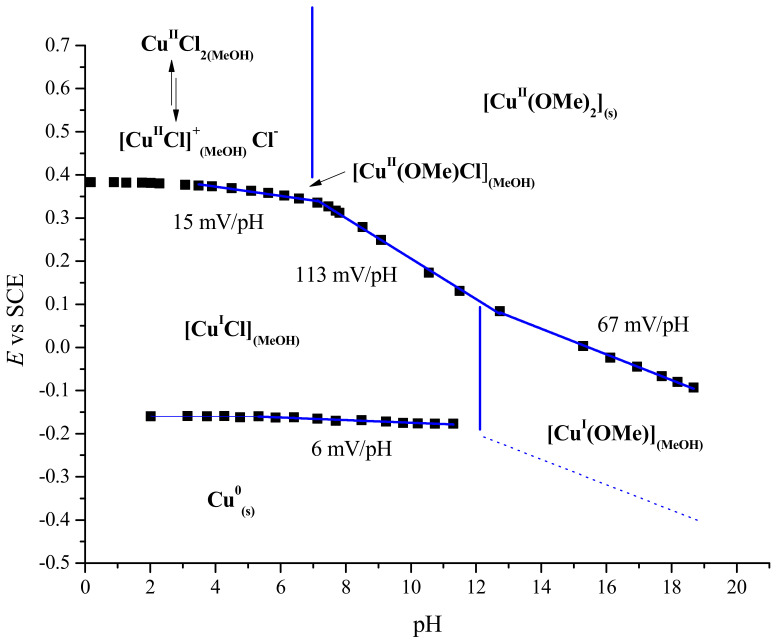

The [PhB(OH)3−]/[PhB(OH)2] concentration ratios and the associated pH range that enable the coupling reaction to proceed (Figure 2 and Figure S13) were estimated between pH 10.5 and 12.5. Under these conditions, the number of anionic ligands on Cu was determined using the Pourbaix diagram of CuIICl2 in MeOH. This diagram was constructed by measuring the open-circuit potential (OCP) of (i) an equimolar solution of CuICl and CuIICl2 (2 mM/2 mM, top plot) at a Pt working electrode and (ii) a Cu(0) working electrode immersed in a 2 mM solution of Cu(I), as a function of the pH of the solution, which was varied by the addition of a small quantity of a 1 M solution of TBAOH in MeOH (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pourbaix diagram of Cu(I) and Cu(II) in MeOH (Cu(I) and Cu(II) concentration 2 mM).

For pH ranging from 4 to 8, the potentials of the Cu(II)/Cu(I) and Cu(I)/Cu(0) couple show very little variation; this indicates that counter anions are not coordinated to either Cu(I) or Cu(II). Above pH 8, the Cu(II)/Cu(I) curve shows a nonlinear transition that is indicative of the partial formation of either [CuII(OR)Cl] and/or [CuII(OR)]+ complexes (pKa1 (CuCl2/Cu(OH)Cl) = 9). This transition is also indicated by the formation of green complex. Above pH 10, the slope of the later increases to a value of 113 mV/pH; this corresponds to the coordination of anionic ligands to Cu(II) to form the [CuII(OR)2] (R = H, Me) alkoxide complexes that partially precipitate (pKa2 (CuCl2/Cu(OR)2 = 16.3). Of note, such a precipitate was never observed under the reaction conditions, even at a higher base concentration. For pH above 11, [CuI(OH)] becomes the predominant species for Cu(I).

2.5. Computational Mechanistic Investigation: B-to-Cu(II) Transmetalation

Based on the results described in Section 2.4, Cu(II) is likely to exist under the form of a [CuII(OR)2] complex, with OR− = HO−, MeO−, PhB(OH)3− depending on the reaction conditions, for pH ranging between 9.5 and 12.5. However, at low pH, the formation of [CuIICl(OR)] or [CuII(OR)]+ cannot be excluded. Thereof, the ability of all these species to promote B-to-Cu(II) transmetalation was evaluated by means of a computational mechanistic investigation performed at the DFT level using the B3LYP hybrid functional [35,36,37,38]. Hereafter, energies refer to Gibbs energies (∆G, kcal mol−1) estimated at 298 K and 1 atm upon full geometry optimization. Solvation by methanol has been modeled by means of a micro-solvation approach [39] that combines an explicit description of the first solvation sphere and an implicit representation of the bulk solvation effects by a polarization continuum model [40]. The fully detailed computational approach is available in Section 4, Materials and Methods. In the following sections, DFT-optimized structures are tagged by Arabic numerals. If the complex is cationic, a + is added (e.g., 5+). For neutral complexes, the counter anion is specified by a superscript (e.g., 4OH). The presence and the number of explicit solvent molecules are indicated by a superscript n = (e.g., 4+,n=2), ranging from 0 to 2. Finally, when spin intercrossing occurs, i.e., in Section 2.6, the spin state (singlet s, doublet d, triplet t) of the complex is specified in superscript brackets (e.g., 9MeO(t),n=0). Transition states are indicated using the prefix TS-.

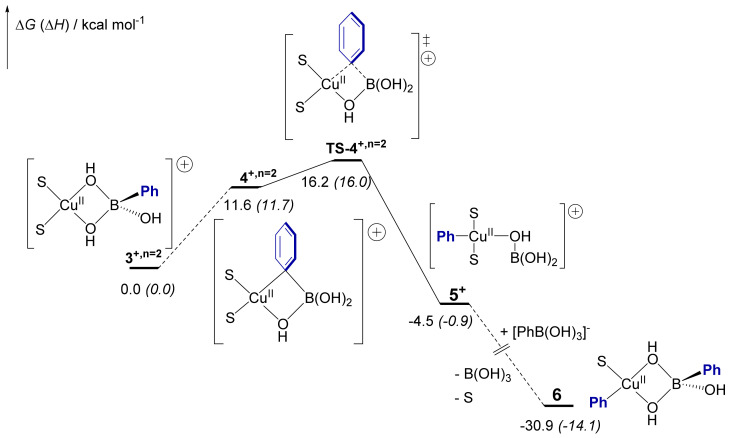

The transmetalation mechanism starting from variously solvated heterobimetallic adducts [CuII(PhB(OH)3)(MeOH)n]+ (3+,n) between phenylboronate (1) and [CuIIMeOH2]2+ (2) was investigated. Figure 5 depicts the most relevant Gibbs energy profile in the case of the di-solvated [CuII(PhB(OH)3)(MeOH)2]+ (3+,n = 2) heterobimetallic adduct. The influence of solvation on the stabilities of 3+,n (n = 0, 1 or 2) and on the B-to-Cu transmetalation energy barriers is discussed in the SI (Figure S15) [39].

Figure 5.

Reaction profile of the Cu-to-B transmetalation in the heterobimetallic cationic intermediate [(S)2Cu(μ-OH)2B(Ph)(OH)]+ (3+,n = 2) (S = MeOH) computed at the DFT level. ∆G (∆H) are given in kcal mol−1. See Figures S14–S16 for alternative pathways.

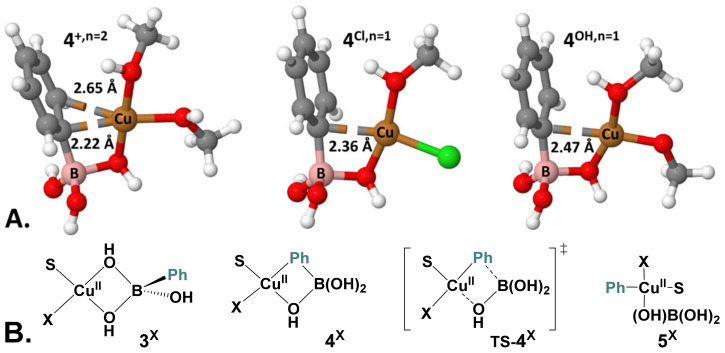

Complex 3+,n = 2 features two bridging μ-OH groups between Cu(II) and B atoms and the four-membered ring atoms are nearly co-planar (ΦCu-O-B-O = 1.5°, Figure 6A). The formation of such a mixed Cu-(μ-OH)-B dimer as a key pre-transmetalation species mirrors previous reports on Pd [41,42,43] or Ni complexes [44]. Starting from complex 3+,n=2, one of the bridging hydroxy groups is exchanged with the phenyl group via a torsion along the non-exchanging B-µ-O bond. This isomerism is endergonic by 11.6 kcal mol−1 and gives the pre-transmetalation intermediate 4+,n=2. In 4+,n = 2, the interaction between Cu and the Ph moiety has a pronounced σ character, as indicated by the open B-Cipso-Cpara angle of 171° and the short Cu-Cipso distance (2.22 Å) (Figure 6A). This pre-activation allows the easy transfer of the Ph group via the early transition state TS-4+,n = 2. Relative to 3+,n = 2, transmetalation via TS-4+,n = 2 requires us to overcome an overall Gibbs energy barrier of 16.2 kcal mol−1 to yield the transmetalated complex trans-[CuII(Ph)(MeOH)2(μ-OH)B(OH)2]+ (5+). This is in good agreement with previous calculations related to boronate transmetalation reported on a parent Cu system [45]. From 3+,n = 2 to TS-4+,n=2, the main contribution to the energy barrier is the formation of pre-complex 4+,n = 2. From cationic complex 5+, coordination of a second phenylboronate molecule [PhB(OH)3]− (1) along with the release of boronic acid leads to intermediate 6. The large exergonicity of the reaction and the overall Gibbs energy barrier of ca. 16 kcal mol−1 are in line with experimental data.

Figure 6.

(A). 3D structures of optimized intermediates 4X,n (X = +, Cl or MeO, n = 1 or 2). H in white, C in grey, O in red, B in pink, Cu in orange, and Cl in green. (B). Structures of intermediates and transition states involved in the B-to-Cu transmetalation (see Table 1 for the associated energies). See Figures S15 and S16 for alternative solvation states.

Alternative pathways of transmetalation have been explored starting from neutral monosolvated Cu(II) complexes [CuII(MeOH)(X)(μ-OH)2B(Ph)(OH)], X = Cl (3Cl,n = 1), MeO (3MeO,n = 1). The Gibbs energies of the computed profiles are gathered in Table 1. The presence of a chloride bounded to Cu merely affects the overall transmetalation barrier (17.2 kcal mol−1) compared to the cationic system (16.2 kcal mol−1). By comparison, methoxide is slowing down transmetalation as indicated by an overall energy barrier of 23.7 kcal mol−1. This could be one possible explanation for the observed pH dependence of the homocoupling kinetics.

Table 1.

Transmetalation paths starting from neutral heterobimetallic Cu(II)/B complexes [CuII(MeOH)n(X)(μ-OH)2B(Ph)(OH)] (3X,n), X = Cl, MeO, n = 0 or 1. ∆G (∆H) in kcal mol−1.

| X, n | 3X | 4X | TS-4X | 5X |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl, n = 1 | 0.0 (0.0) | 9.9 (11.4) | 17.2 (18.5) | 0.0 (3.7) |

| MeO, n = 1 | 0.0 (0.0) | 11.9 (11.8) | 23.7 (22.7) | 6.5 (8.5) |

| MeO, n = 0 | 0.0 (0.0) | 9.5 (19.1) | 18.0 (16.9) | 0.6 (−3.8) |

The lower ability to transmetalate to hydroxo- or methoxy-copper complexes is also reflected in the structure of the pre-transmetalation intermediate 4X,n = 1. Both 4OH,n = 1 and 4MeO,n = 1 show very little σ-character of the Cu-C bond with bond length of 2.4 Å and flat B-Cipso-C par angle of 175°. This is related to a lower donation from Cu to Ph in agreement with the higher partial charge at the Cu in TS-4MeO,n = 1 (1.326 |e−|) compared to TS-4Cl,n = 1 (1.256 |e−|) (Table S1). Finally, the formation of transmetalation products 5X is either endergonic (X = Cl) or isergonic (X = OH and MeO).

Based on these considerations, we have assessed the influence of solvent coordination on the energy barrier of the transmetalation step (Figures S15 and S16). Mono-solvated 3MeO,n = 1 is merely more stable than the solvent-free 3MeO,n=0 (∆G = −0.7 kcal mol−1); both are likely in equilibria in MeOH solution. The formation of the pre-complex 4MeO,n = 0 is facilitated compared to the mono-solvated case (+9.5 kcal mol−1) and the energy of the subsequent transmetalation transition state TS-4MeO,n = 0 is 4.7 kcal mol−1 lower in energy than the one computed for the mono-solvated transition state TS-4MeO,n = 1 (∆G‡ = 18.0 vs. 22.7 kcal mol−1, Figure S15). These specific solvent effects on transmetalation make the use of an explicit solvent model mandatory for the description of such systems. Indeed, the dynamics of solvation plays an important role in slowing down or facilitating the transmetalation, as suggested for other related systems [46,47,48].

The mechanism presented above accounts for the experimental data regarding the transmetalation but does not rationalize the formation of homocoupling products. One possible mechanism to explain the homocoupling involves a second B-to-Cu transmetalation of the phenyl group followed by a reductive elimination (Scheme 1). The energy profile of this reaction pathway were computed starting from [CuII(MeOH)(PhB(OH)3)Ph] (6) (see Figure S17). Activation energies related to a second transmetalation have been computed to at least 25.1 kcal mol−1. Based on the experimental conditions and the kinetic measurements, this reaction sequence cannot thereof account for the formation of homocoupling products, though it is commonly suggested.

2.6. Computational Mechanistic Investigation: Cu(II)-Cu(II) Transmetalation and Reductive Elimination

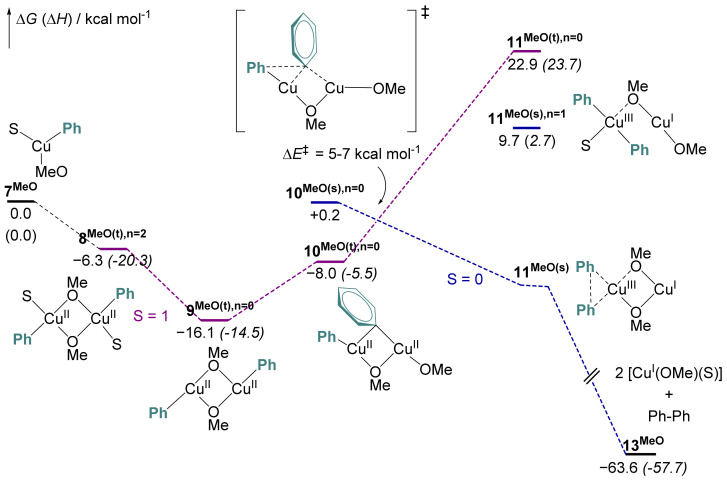

To rationalize the formation of homocoupling products, we have considered alternative reaction pathways in which the second transmetalation takes place between two copper centers. Such a mechanism would support the higher kinetic order with respect to Cu experimentally inferred for the homocoupling reaction. In the following section, we will only discuss the reaction sequence starting from the monomeric PhCu(S)OMe (7MeO) that results from the first transmetalation (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Gibbs energy profile of the Cu-to-Cu second transmetalation and subsequent reductive elimination computed at the DFT level (see the computational details). ∆G (∆H) are given in kcal mol−1.

The second transmetalation starts with the dimerization of 7MeO(d) in its doublet state (S = 1/2) to form the high-spin di-solvated CuII-CuII dimer 8MeO(t),n = 2 (S = 1), whose formation is computed exergonic by 6.3 kcal mol−1. The release of two solvent molecules from 8MeO(t),n = 2 leads to an even more stable dimer triplet complex 8MeO(t),n = 0 (∆G = −16.1 kcal mol−1 relative to 7MeO(d)). Torsion along the nonreactive CuII-(μ-OH) bond enables the exchange between one bridging μ-MeO group and the Ph ring to yield 9MeO(t),n = 0 in its triplet state. This step is endergonic by 8.1 kcal mol−1. More details on the speciation of these intermediates can be found in Tables S2 and S3. For this set of dimers (8 to 9MeO(t),n = 0), the closed-shell singlet state corresponding to the mixed-valence dimer Cu(III)-Cu(I) is always computed higher in energy.

The triplet Cu(II)-Cu(II) complex 9MeO(t),n = 0 can then undergo Cu-Cu transmetalation to yield the mixed-valence (Cu(III)-Cu(I)) singlet complex 10MeO(s),n = 0. This latter is not a true minimum on the potential energy surface and spontaneously undergoes reductive elimination to yield Cu(I)-Cu(I) complex 11MeO(s),n = 0 and biphenyl (Figure S18). Since this transformation requires a spin transition, the associated singlet and triplet energy surface were scanned to estimate the activation energy of this process. The electronic energy of activation for the transmetalation and coupled electron transfer (TET) was estimated to 5 and 7 kcal mol−1. In the case of the monosolvated 10MeO,n = 1, the barrier for the TET process is nearly doubled and the product of transmetalation complex 11MeO(s),n = 1 is an energy minimum (Figure S18). Note that direct reductive elimination at monomeric species Cu(II) is kinetically prohibited (Figure S17). This mechanistic picture for reductive elimination is in agreement with results recently reported by Casares on the role of electron transfer between organocopper complexes in transmetalation reactions [49].

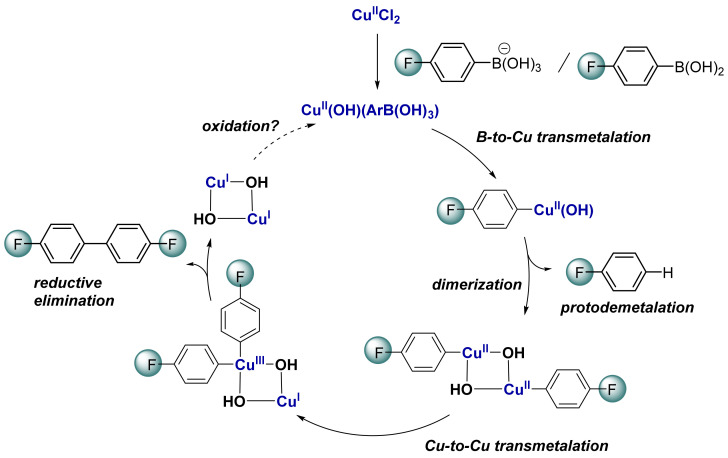

3. Conclusions

The presence of a coordinating base (hydroxide and methoxide) enables the first B-to-Cu(II) transmetalation from aryl boronic acid to CuIICl2 in methanol, while an excess of base is detrimental (Scheme 3). This suggests the formation of heterobimetallic Cu-(μ-OH)-B intermediates as previously suggested [45,50] and as confirmed by our DFT calculations. In contrast with previous suggestions from the literature, a second B-to-Cu transmetalation to form bis-aryl Cu(II) complexes is kinetically prevented [6,7,9]. Alternatively, the formation of organocopper(II) dimers is favored and the latter can undergo a coupled transmetalation-electron transfer (TET) allowing the formation of a mixed-valence organocopper(III)/copper(I) complex able to perform reductive elimination.

Scheme 3.

Updated mechanism proposed for Cu(II)-catalyzed homocoupling of arylboronic acids. See Figure S19 for the most favored pathway for the complete homocoupling process.

The possibility to catalyze homocoupling reactions using Cu(I) in the absence of a base suggests that transmetalation proceeds either via Cu(I) oxidation by O2 and the associated generation of OH− [51,52]:

| 2 Cu+ + 1/2 O2 + H2O = 2 Cu2+ + 2 OH− |

or through a mechanism involving a Cu(I) oxo complex as proposed in the case of Pd(0) or via another oxidation intermediate [27,28]. This point is currently under study within our group.

Based on mechanistic insights herein reported, we can tentatively propose some guidelines to control the undesired formation of homocoupling product in the context of Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. The pH should be controlled and optimized for each catalytic system to favor transmetalation and prevent the side reactions. The use of bidentate ligands is expected to disfavor the formation of dimeric Cu(II) species responsible for homocoupling. Alternatively, using a supported Cu catalyst or working at low catalyst loadings may also be helpful. Finally, the control of the oxygen concentration in the media is crucial to limit the formation of Cu(II) species in Cu-catalyzed non-oxidative cross-coupling reactions.

4. Materials and Methods

Structure optimizations, energy estimation, and NBO 6 analyses [53] were performed with the gaussian 09 software [54]. Molecules have been optimized using an ultrafine grid as implemented in gaussian. The Becke hybrid functional, B3LYP functional was used for all calculations [35,36,37,38]. The 6–31+G augmented double-ζ Pople’s basis sets were used for B, C, and H atoms, and complemented with an extra polarization function for O atom. Quasi relativistic Stuttgart–Dresden 10MWB electron core pseudopotentials and their associated basis sets were used for Cu and Cl atoms [55]. Since the reaction occurs in a highly polar solvent, particular attention was paid to model the solvation. The most favorable solvation states of key intermediates have been verified (see the supporting information), and the bulk solvation effect has been represented by a continuum model for all calculations [56]. Unless specified, optimized transition states were checked by analytical frequency calculations and their connectivity were verified by IRC following.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank J. Vantourout and L. A. Perego for fruitful discussions, and P. Pialot for her contribution to the computational part. The authors are grateful to the CCIR of ICBMS, PSMN, GENCI-TGCC (Grants A0100812501 and A0120813435) for providing computational resources and technical support.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules27217517/s1, Figure S1 19F{1H} kinetic monitoring of the reaction of p-FPhB(OH)2 (0.2 M) and CuIICl2 (20 mM, 20 mol%) in MeOH in the presence of K2CO3 (0.2 M, 1 equiv). A solution of nBu4BF4 0.1 M in d6-DMSO contained in a sealed capillary was used as an internal standard (signal at −148.5 ppm). As indicated on the zoomed insert the formation of the homocoupling product proceed very fast when the base is added and a plateau is obtained around 0.01 mol L−1 corresponding to a stoichiometry of two Cu(II) per mol of homocoupling product formed. Figure S2 19F{1H} NMR spectrum of a solution of p-FPhB(OH)2 (20 mM, 2 equiv) and CuIICl2 (10 mM) in MeOH in the absence of added base A. at t = 0 h, B. after 5h. A solution of nBu4BF4 0.1 M in d6-DMSO contained in a sealed capillary was used as an internal standard (signal at −148.5 ppm). Figure S3 19F{1H} NMR spectrum of a solution of p-FPhB(OH)2 (20 mM, 20 equiv), TBAOH (12 mM, 12 equiv) and CuCl2 (1 mM, 1 equiv) in MeOH. A solution of fluorobenzene in d6-DMSO contained in a sealed capillary was used as an internal standard (signal at −113.1 ppm). fluorobenzene in MeOH (−115.2 ppm), homocoupling product (−117.9 ppm), p-F-phenol (−126.5 ppm) and p-F-anisole (−128.1 ppm). Figure S4 19F{1H} NMR spectrum of a solution of p-FPhB(OH)2 (20 mM) and TBAOH (1 equiv) in the absence of CuIICl2 in MeOH at t = 0 and t = 24 h. The signal of [p-FPhB(OH)3]− is detected at −121.6 ppm.Figure S5 19F{1H} NMR spectrum of a solution of p-FPhB(OH)2 (20 mM, 1 equiv), TBAOH (12 mM, 0.5 equiv) and CuCl2 (20 mM, 1 equiv) in MeOH. A solution of fluorobenzene in d6-DMSO contained in a sealed capillary was used as an internal standard (signal at −113.1 ppm).Figure S6 19F{1H} NMR spectrum of a solution of p-FPhB(OH)2 (20 mM, 10 equiv) and CuIICl2 (2 mM) in MeOH in the presence of a) 4 equiv of TBAOH, b) 8 equiv of TBAOH. A solution of fluorobenzene in d6-DMSO contained in a sealed capillary was used as an internal standard (signal at −113.1 ppm). Figure S7 Cyclic voltammogram toward reduction (left) and oxidation (right) potentials of a solution of CuCl2 (2 mM) in MeOH (red line) and in the presence of PhB(OH)2 (10 mM) (green line). Working electrode: glassy carbon (Ø = 3 mm); scan rate: 0.5 V s−1; supporting electrolyte: nBu4BF4 (0.3 M); recorded at ambient temperature starting at the Open Circuit Potential (OCP). Figure S8 Cyclic voltammetry toward reduction potentials monitoring of the reduction of Cu(II) (CuCl2, 2 mM) to Cu(I) by PhB(OH)2 in the presence of TBAOH (Dark green). After addition of PhB(OH)2 (10 mM, Light green). (Apple green) Addition of TBAOH (5 mM) at t = 0. (Light orange) After 20 min. (Orange) After 30 min. (Red) After 45 min. Working electrode: glassy carbon (Ø = 3 mm); scan rate: 0.5 V s−1; supporting electrolyte: nBu4BF4 (0.3 M); recorded at ambient temperature starting at the Open Circuit Potential (OCP). Figure S9 Cyclic voltammogram toward oxidation of a solution of CuCl2 (2 mM) in MeOH. Working electrode: glassy carbon (Ø = 3 mm); scan rate: 0.5 V s−1; supporting electrolyte: nBu4BF4 (0.3 M); recorded at ambient temperature starting at the Open Circuit Potential (OCP). Figure S10 Kinetic monitoring of the reduction of CuCl2 (1 mM) by PhB(OH)2 (10 mM, 10 equiv) in the presence of TBAOH (6 mM, 6 equiv). Working electrode: glassy carbon (Ø = 3 mm); rotation rate: 1000 min−1, imposed potential +0.7 V/SCE; supporting electrolyte: nBu4BF4 (0.3 M); thermostat 20 °C, recorded at ambient temperature. Figure S11 Kinetic monitoring of the reduction of CuCl2 (1 mM) by p-X-PhB(OH)2 (10 mM, 10 equiv, X = MeO, CH3, F, Cl, CN et NO2) in the presence of TBAOH (4 mM, left / 8 equiv right). Working electrode: glassy carbon (Ø = 3 mm); rotation rate: 1000 min−1, imposed potential +0.7 V/SCE; supporting electrolyte: nBu4BF4 (0.3 M); thermostat 20 °C, recorded at ambient temperature. Figure S12 A. Evolution of the conductivity (σ, mS m−1) versus the concentration of added CuIICl2 (mol m3). B. Evolution of the ionic molar conductivity of the solution λ (mS m2 mol−1) versus the square root of the concentration of added CuIICl2 (mol1/2 m−3/2). Figure S13 Evolution of the pH during the titration of a solution of phenylboronic acid (10 mmol L−1) by TBAOH (1.0 mol L−1 in MeOH). The pKa of the couple PhB(OH)2/PhB(OH)3− can be read 0.5 equiv, pKa = 11.2. Figure S14 Reaction profiles of the Cu-to-B transmetalation starting for (i) the heterobimetallic cationic complex [(S)2Cu(μ-OH)2B(Ph)(OH)]+ (3+) (ii) the neutral heterobimetallic intermediate complexes [S(X)Cu(μ-OH)2B(Ph)(OH)] (3X) for X = Cl, OH and MeO, computed at the DFT level. Free energies and enthalpies ∆G (∆H) are given in kcal mol−1 Figure S15 Gibbs free energy calculated at the DFT level for the first boron-to-copper transmetalation involving cationic (red) and neutral (X = MeO, green) intermediates for different solvation states (i.e. n = 0 to 2 MeOH coordinated to Cu atom). Free energies and enthalpies ∆G (∆H) are given in kcal mol−1. Figure S16 Gibbs free energy calculated at the DFT level for the first boron-to-copper transmetalation involving cationic neutral (X = Cl, n = 0 to 2) intermediates for different solvation states. Free energies and enthalpies ∆G (∆H) are given in kcal mol−1. Figure S17 Reaction profiles of the second Cu-to-B transmetalation and following reductive elimination on monomeric organocopper starting for organocopper heterobimetallic complex [(S)(Ph)Cu(μ-OH)2B(Ph)(OH)] (6) computed at the DFT level. Free energies and enthalpies ∆G (∆H) are given in kcal mol−1. Figure S18 Scans of the triplet and singlet potential energy surfaces over the (µ-(Ph)Csp2)-Cu2 distances for CuII-CuII transmetalation A: without any MeOH coordinated, B: with a “trapping” MeOH and C: over the Cu1-(µ-(Ph)Csp2)-Cu2 angle starting from complexes 11Cl(t). Figure S19 Complete mechanism for homocoupling process computed at the DFT level. Free energies and enthalpies ∆G (∆H) are given in kcal mol−1. Table S1. Comparison of B-to-Cu transition states. Dihedral angles are in degree, distances are in Å, partial charge in atomic unit (1 a.u. = |e−|). The numbers indicated between parenthesis correspond to the bond length variation between 4X,n and TS-4X,n (X = MeOH, Cl or MeO). Table S2. Formation free energy of CuII-CuII dimers with R1, R2 = Cl, OH and MeO as bridging groups. Gibbs free energy (∆G, kcal mol−1) and enthalpies (∆H, kcal mol−1) are calculated using the monomers (R1CuPh) and (R2CuPh) as a reference. In some cases, one or more MeOH molecules are de-coordinates from Cu during optimization and these structures are quoted n.d. The formation of dimers is favored in basic media (−OH or −OMe present). Table S3. Solvation of CuII-CuII dimers with R1 = Ph as bridging groups. ∆G (∆H) in kcal mol−1. In some cases, one or more MeOH molecules are de-coordinate from Cu during optimization and these structures are quoted n.d. Cartesians coordinates for all DFT-optimized structures are available in the Cartesians.xyz supplementary file.

Author Contributions

A.S. performed the experimental part under the guidance of L.G., P.-A.P., A.S. and J.R. contributed to the computational part under the guidance of I.C., P.-A.P. and L.P., P.-A.P. designed and lead the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Figures or Supplementary Materials of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

J.R. thanks the MESR for a PhD fellowship. The authors are grateful to the CNRS, Chimie-Paristech-PSL, ENS-PSL, ICBMS, Université Lyon 1, and the Region Auvergne Rhone Alpes for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ullmann F., Bielecki J. Ueber Synthesen in der Biphenylreihe. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1901;34:2174–2185. doi: 10.1002/cber.190103402141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ullmann F. Ueber eine neue Bildungsweise von Diphenylaminderivaten. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1903;36:2382–2384. doi: 10.1002/cber.190303602174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ullmann F., Sponagel P. Ueber die Phenylirung von Phenolen. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1905;38:2211–2212. doi: 10.1002/cber.190503802176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg I. Ueber Phenylirungen bei Gegenwart von Kupfer als Katalysator. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1906;39:1691–1692. doi: 10.1002/cber.19060390298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beletskaya I.P., Cheprakov A.V. The Complementary Competitors: Palladium and Copper in C–N Cross-Coupling Reactions. Organometallics. 2012;31:7753–7808. doi: 10.1021/om300683c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirai N., Yamamoto Y. Homocoupling of Arylboronic Acids Catalyzed by 1,10-Phenanthroline-Ligated Copper Complexes in Air. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009;2009:1864–1867. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200900173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y.-N., Tian X.-C., Chen X.-X., Yao Y.-X., Gao F., Zhou X.-L. Rapid Ligand-Free Base-Accelerated Copper-Catalyzed Homocoupling Reaction of Arylboronic Acids. Synlett. 2017;28:601–606. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaboudin B., Haruki T., Yokomatsu T. CuSO4-Mediated Homocoupling of Arylboronic Acids under Ligand- and Base-Free Conditions in Air. Synthesis. 2011;2011:91–96. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1258321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng G., Luo M. Homocoupling of Arylboronic Acids Catalyzed by CuCl in Air at Room Temperature. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011;2011:2519–2523. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201001729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang C.-T., Zhang Z.-Q., Liu Y.-C., Liu L. Copper-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reaction of Organoboron Compounds with Primary Alkyl Halides and Pseudohalides. Angew. Chem. Int. 2011;50:3904–3907. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villalobos J.M., Srogl J., Liebeskind L.S. A New Paradigm for Carbon−Carbon Bond Formation: Aerobic, Copper-Templated Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15734–15735. doi: 10.1021/ja074931n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang S.-K., Kim J.-S., Choi S.-C. Copper- and Manganese-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Organostannanes with Organic Iodides in the Presence of Sodium Chloride. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:4208–4209. doi: 10.1021/jo970656j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyake Y., Wu M., Rahman M.J., Kuwatani Y., Iyoda M. Efficient Construction of Biaryls and Macrocyclic Cyclophanes via Electron-Transfer Oxidation of Lipshutz Cuprates. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:6110–6117. doi: 10.1021/jo0608063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strieter E.R., Bhayana B., Buchwald S.L. Mechanistic Studies on the Copper-Catalyzed N-Arylation of Amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:78–88. doi: 10.1021/ja0781893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefèvre G., Franc G., Tlili A., Adamo C., Taillefer M., Ciofini I., Jutand A. Contribution to the Mechanism of Copper-Catalyzed C–N and C–O Bond Formation. Organometallics. 2012;31:7694–7707. doi: 10.1021/om300636f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mansour M., Giacovazzi R., Ouali A., Taillefer M., Jutand A. Activation of aryl halides by Cu0/1,10-phenanthroline: Cu0 as precursor of CuI catalyst in cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Commun. 2008:6051–6053. doi: 10.1039/b814364a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stollenz M., Meyer F. Mesitylcopper—A Powerful Tool in Synthetic Chemistry. Organometallics. 2012;31:7708–7727. doi: 10.1021/om3007689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piers E., Yee J.G.K., Gladstone P.L. CuCl-Mediated Intramolecular Oxidative Coupling of Aryl- and Alkenyltrimethylstannane Functions. Org. Lett. 2000;2:481–484. doi: 10.1021/ol9903988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demir A.S., Reis Ö., Emrullahoglu M. Role of Copper Species in the Oxidative Dimerization of Arylboronic Acids: Synthesis of Symmetrical Biaryls. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:10130–10134. doi: 10.1021/jo034680a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y., You W., Smith K.B., Brown M.K. Copper-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Boronic Esters with Aryl Iodides and Application to the Carboboration of Alkynes and Allenes. Angew. Chem. Int. 2014;53:3475–3479. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goj L.A., Blue E.D., Delp S.A., Gunnoe T.B., Cundari T.R., Petersen J.L. Single-Electron Oxidation of Monomeric Copper(I) Alkyl Complexes: Evidence for Reductive Elimination through Bimolecular Formation of Alkanes. Organometallics. 2006;25:4097–4104. doi: 10.1021/om060409i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vantourout J.C., Miras H.N., Isidro-Llobet A., Sproules S., Watson A.J.B. Spectroscopic Studies of the Chan–Lam Amination: A Mechanism-Inspired Solution to Boronic Ester Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:4769–4779. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West M.J., Fyfe J.W.B., Vantourout J.C., Watson A.J.B. Mechanistic Development and Recent Applications of the Chan–Lam Amination. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:12491–12523. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vantourout J.C., Law R.P., Isidro-Llobet A., Atkinson S.J., Watson A.J.B. Chan–Evans–Lam Amination of Boronic Acid Pinacol (BPin) Esters: Overcoming the Aryl Amine Problem. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:3942–3950. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vantourout J.C., Li L., Bendito-Moll E., Chabbra S., Arrington K., Bode B.E., Isidro-Llobet A., Kowalski J.A., Nilson M.G., Wheelhouse K.M.P., et al. Mechanistic Insight Enables Practical, Scalable, Room Temperature Chan–Lam N-Arylation of N-Aryl Sulfonamides. ACS Catal. 2018;8:9560–9566. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b03238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell N.L., Xu C., Fyfe J.W.B., Vantourout J.C., Brals J., Chabbra S., Bode B.E., Cordes D.B., Slawin A.M.Z., McGuire T.M., et al. Cu(OTf)2-Mediated Cross-Coupling of Nitriles and N-Heterocycles with Arylboronic Acids to Generate Nitrilium and Pyridinium Products**. Angew. Chem. Int. 2021;60:7935–7940. doi: 10.1002/anie.202016811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamo C., Amatore C., Ciofini I., Jutand A., Lakmini H. Mechanism of the Palladium-Catalyzed Homocoupling of Arylboronic Acids: Key Involvement of a Palladium Peroxo Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6829–6836. doi: 10.1021/ja0569959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakmini H., Ciofini I., Jutand A., Amatore C., Adamo C. Pd-Catalyzed Homocoupling Reaction of Arylboronic Acid: Insights from Density Functional Theory. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:12896–12903. doi: 10.1021/jp801948u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jutand A. Contribution of electrochemistry to organometallic catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2300–2347. doi: 10.1021/cr068072h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Opekar F., Beran P. Rotating disk electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1976;69:1–105. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0728(76)80129-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amatore C., Le Duc G., Jutand A. Mechanism of Palladium-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions: Multiple and Antagonistic Roles of Anionic “Bases” and Their Countercations. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:10082–10093. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schreck J.O. Nonlinear Hammett relationships. J. Chem. Educ. 1971;48:103. doi: 10.1021/ed048p103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salmon P.S., Neilson G.W., Enderby J.E. The structure of Cu2+ aqueous solutions. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1988;21:1335–1349. doi: 10.1088/0022-3719/21/8/010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reichardt C., Welton T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becke A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. doi: 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee C., Yang W., Parr R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vosko S.H., Wilk L., Nusair M. Accurate spin-dependent electron liquid correlation energies for local spin density calculations: A critical analysis. Can. J. Phys. 1980;58:1200–1211. doi: 10.1139/p80-159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephens P.J., Devlin F.J., Chabalowski C.F., Frisch M.J. Ab Initio Calculation of Vibrational Absorption and Circular Dichroism Spectra Using Density Functional Force Fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:11623–11627. doi: 10.1021/j100096a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norjmaa G., Ujaque G., Lledós A. Beyond Continuum Solvent Models in Computational Homogeneous Catalysis. Top. Catal. 2022;65:118–140. doi: 10.1007/s11244-021-01520-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomasi J., Mennucci B., Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2999–3094. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Payard P.-A., Bohn A., Tocqueville D., Jaouadi K., Escoude E., Ajig S., Dethoor A., Gontard G., Perego L.A., Vitale M., et al. Role of dppf Monoxide in the Transmetalation Step of the Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling Reaction. Organometallics. 2021;40:1120–1128. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas Andy A., Denmark Scott E. Pre-transmetalation intermediates in the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction revealed: The missing link. Science. 2016;352:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas A.A., Zahrt A.F., Delaney C.P., Denmark S.E. Elucidating the Role of the Boronic Esters in the Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction: Structural, Kinetic, and Computational Investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:4401–4416. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payard P.-A., Perego L.A., Ciofini I., Grimaud L. Taming Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling: A Mechanistic Focus on Boron-to-Nickel Transmetalation. ACS Catal. 2018;8:4812–4823. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b00933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bose S., Dutta S., Koley D. Entering Chemical Space with Theoretical Underpinning of the Mechanistic Pathways in the Chan–Lam Amination. ACS Catal. 2022;12:1461–1474. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c04479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Del Pozo J., Pérez-Iglesias M., Álvarez R., Lledós A., Casares J.A., Espinet P. Speciation of ZnMe2, ZnMeCl, and ZnCl2 in Tetrahydrofuran (THF), and Its Influence on Mechanism Calculations of Catalytic Processes. ACS Catal. 2017;7:3575–3583. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.6b03636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peltzer R.M., Eisenstein O., Nova A., Cascella M. How Solvent Dynamics Controls the Schlenk Equilibrium of Grignard Reagents: A Computational Study of CH3MgCl in Tetrahydrofuran. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:4226–4237. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b02716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rio J., Perrin L., Payard P.-A. Structure—Reactivity Relationship of Organo-zinc and -zincate Reagents: Key Elements towards Molecular Understanding. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022:e202200906. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.202200906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lozano-Lavilla O., Gómez-Orellana P., Lledós A., Casares J.A. Transmetalation Reactions Triggered by Electron Transfer between Organocopper Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2021;60:11633–11639. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King A.E., Ryland B.L., Brunold T.C., Stahl S.S. Kinetic and Spectroscopic Studies of Aerobic Copper(II)-Catalyzed Methoxylation of Arylboronic Esters and Insights into Aryl Transmetalation to Copper(II) Organometallics. 2012;31:7948–7957. doi: 10.1021/om300586p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gray R.D. Kinetics of oxidation of copper(I) by molecular oxygen in perchloric acid-acetonitrile solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:56–62. doi: 10.1021/ja01029a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nord H., Sæland E., Morpurgo A., Caglieris A. Kinetics of the Autoxidation of Cuprous Chloride in Hydrochloric Acid Solution. Acta Chem. Scand. 1955;9:430–437. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.09-0430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glendening E.D., Badenhoop J.K., Reed A.E., Carpenter J.E., Bohmann J.A., Morales C.M., Landis C.R., Weinhold F. NBO 6.0. Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin; Madison, WI, USA: 2013. [(accessed on 7 October 2022)]. Available online: http://nbo6.chem.wisc.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., et al. Gaussian 09. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT, USA: 2013. Revision D.01. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergner A., Dolg M., Küchle W., Stoll H., Preuß H. Ab initio energy-adjusted pseudopotentials for elements of groups 13–17. Mol. Phys. 1993;80:1431–1441. doi: 10.1080/00268979300103121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marenich A.V., Cramer C.J., Truhlar D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Figures or Supplementary Materials of this article.