Keywords: airway ion transport, gel-on-brush model, mucins, muco-obstructive diseases, mucus

Abstract

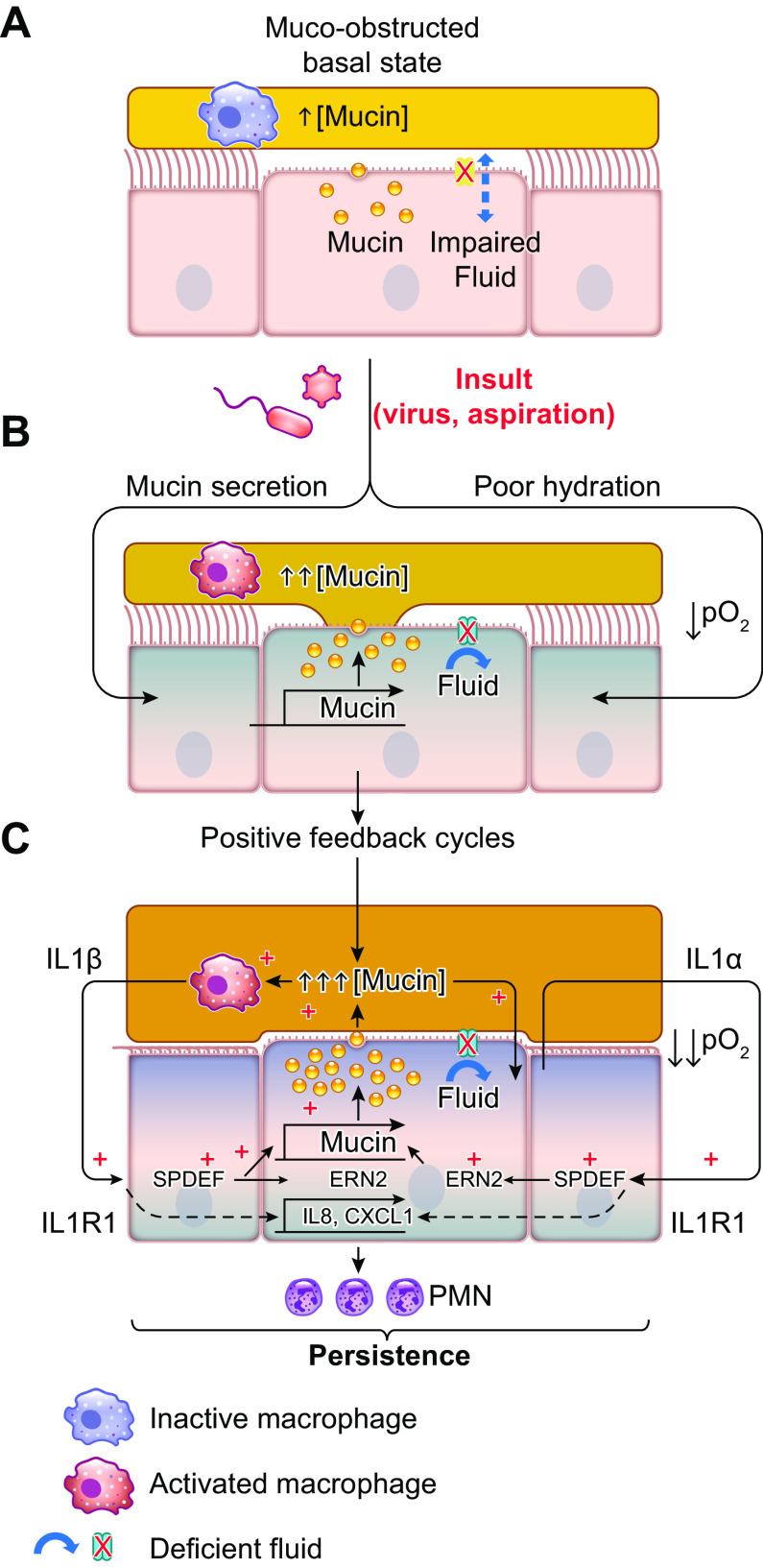

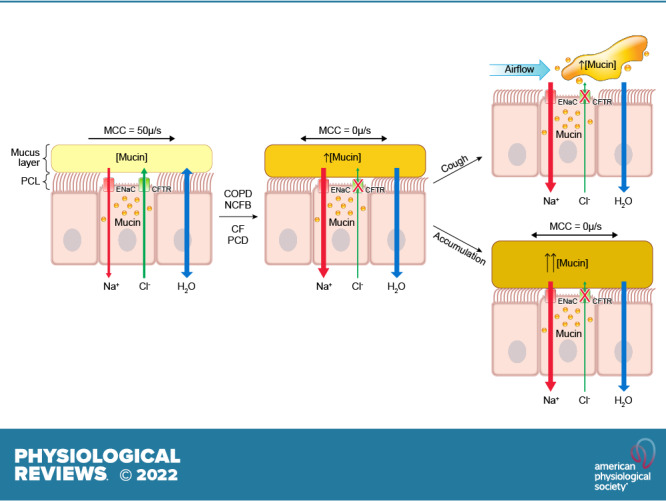

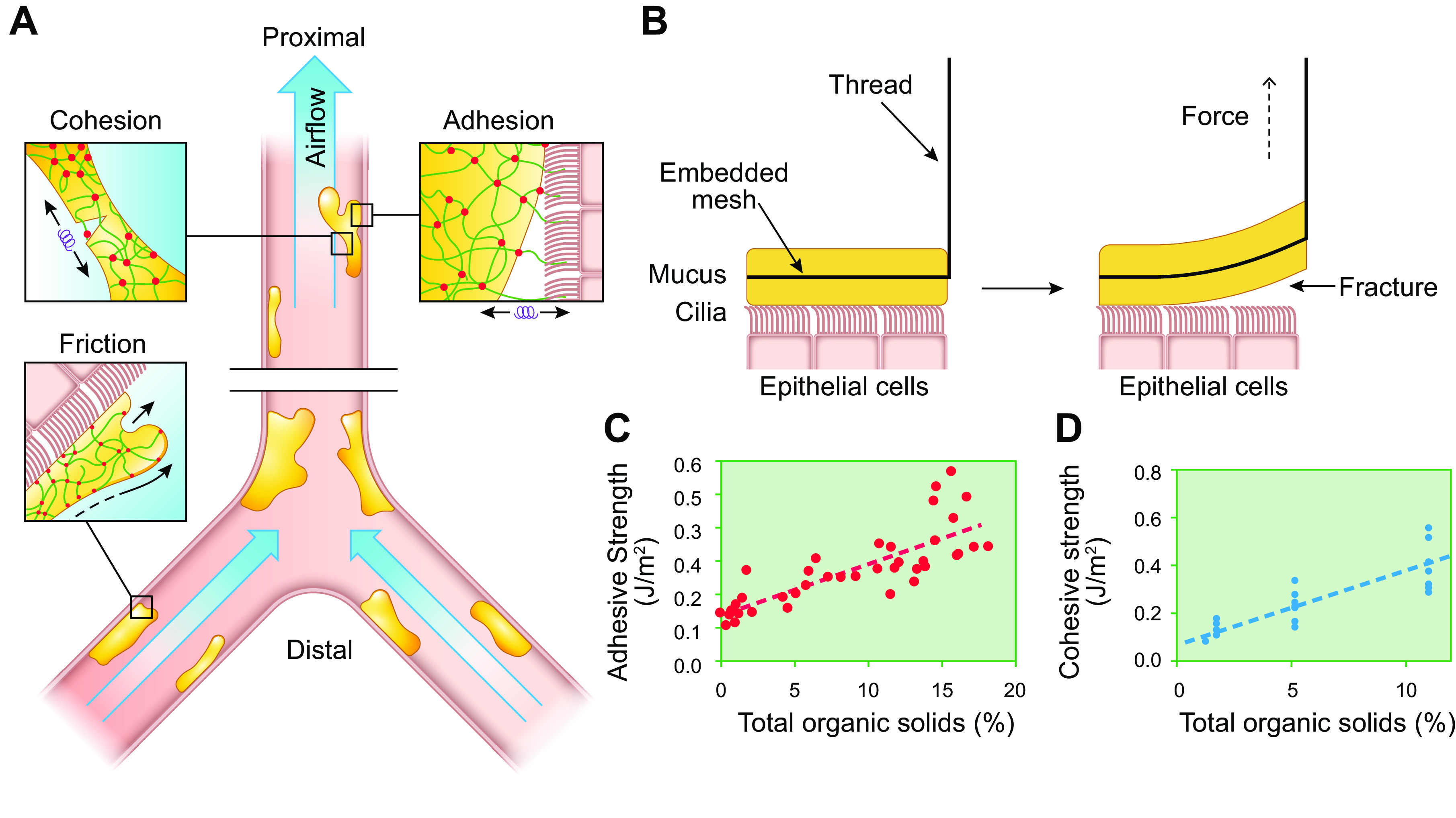

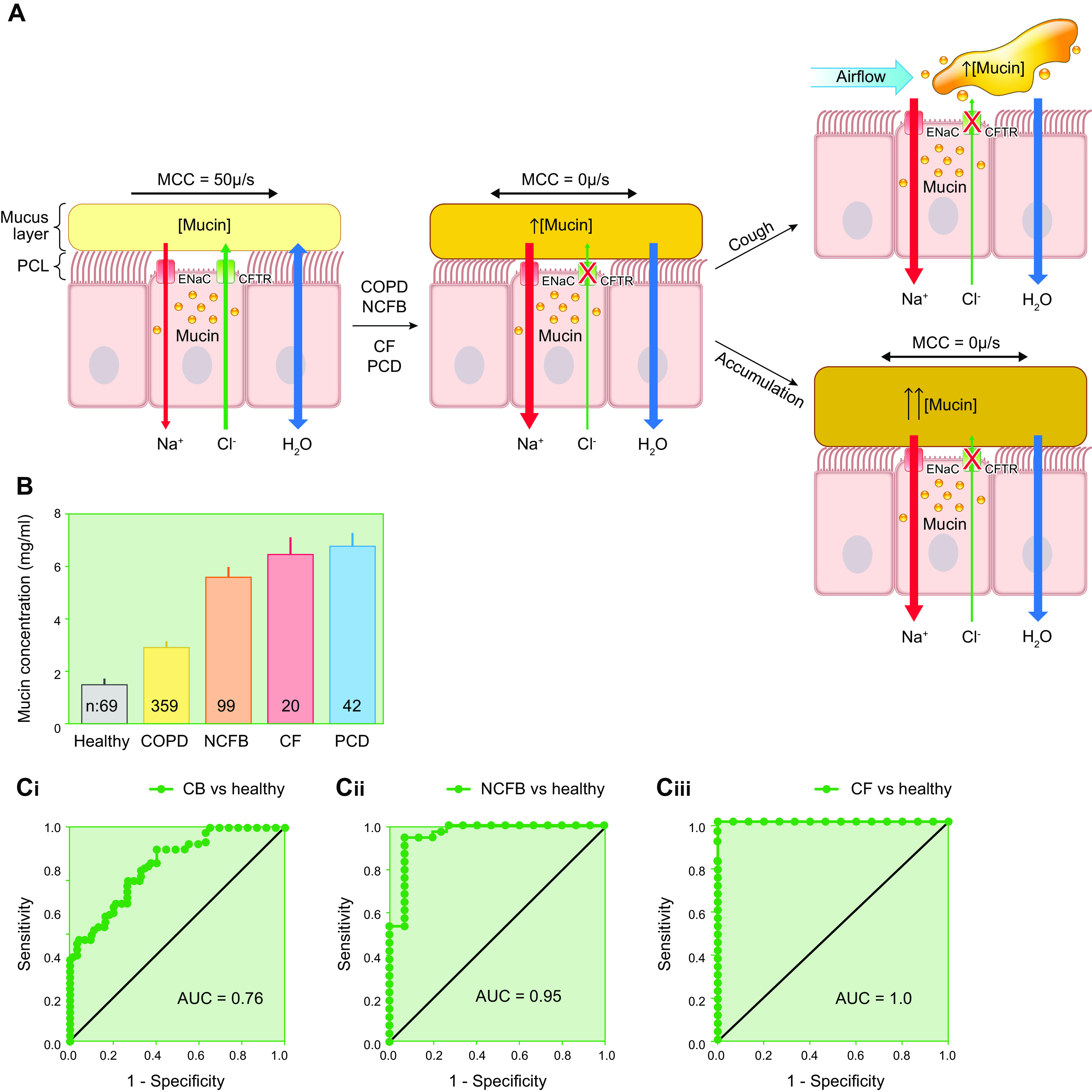

The mucus clearance system is the dominant mechanical host defense system of the human lung. Mucus is cleared from the lung by cilia and airflow, including both two-phase gas-liquid pumping and cough-dependent mechanisms, and mucus transport rates are heavily dependent on mucus concentration. Importantly, mucus transport rates are accurately predicted by the gel-on-brush model of the mucociliary apparatus from the relative osmotic moduli of the mucus and periciliary-glycocalyceal (PCL-G) layers. The fluid available to hydrate mucus is generated by transepithelial fluid transport. Feedback interactions between mucus concentrations and cilia beating, via purinergic signaling, coordinate Na+ absorptive vs Cl− secretory rates to maintain mucus hydration in health. In disease, mucus becomes hyperconcentrated (dehydrated). Multiple mechanisms derange the ion transport pathways that normally hydrate mucus in muco-obstructive lung diseases, e.g., cystic fibrosis (CF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), non-CF bronchiectasis (NCFB), and primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). A key step in muco-obstructive disease pathogenesis is the osmotic compression of the mucus layer onto the airway surface with the formation of adherent mucus plaques and plugs, particularly in distal airways. Mucus plaques create locally hypoxic conditions and produce airflow obstruction, inflammation, infection, and, ultimately, airway wall damage. Therapies to clear adherent mucus with hydrating and mucolytic agents are rational, and strategies to develop these agents are reviewed.

CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS

Mucus accumulation represents a classic clinical problem in the chronic and exacerbating phases of many airway diseases. Recent translational data suggest that muco-obstructive diseases are typically associated with hyperconcentrated, i.e., dehydrated, mucus. Basic science studies have contributed two major insights into the mechanisms that mediate intrapulmonary mucus accumulation. First, electrophysiological studies suggest that imbalances in Na+/fluid absorption vs. Cl−/fluid secretion cause increased mucus concentrations. Second, polymer physics studies suggest that mucus hyperconcentration generates mucin polymer-dependent osmotic forces that compress the mucus layer onto airway surfaces, ultimately producing the mucus accumulation, particularly in small airways, that characterizes muco-obstructive diseases. Therapies for muco-obstructive diseases can be directed toward the upstream ion transport defects that produce hyperconcentrated mucus, as demonstrated by the highly effective modulators that restore CFTR function, and/or therapies designed to broadly rehydrate airway surfaces, including inhaled osmolytes. Therapeutic needs for the future include more durable/effective hydrating agents and agents that break up accumulated intrapulmonary mucus, i.e., effective mucolytics.

1. INTRODUCTION: SHORT HISTORY OF TRADITIONAL CONCEPTS OF NORMAL MUCUS, MUCUS CLEARANCE, AND MUCUS IN DISEASE

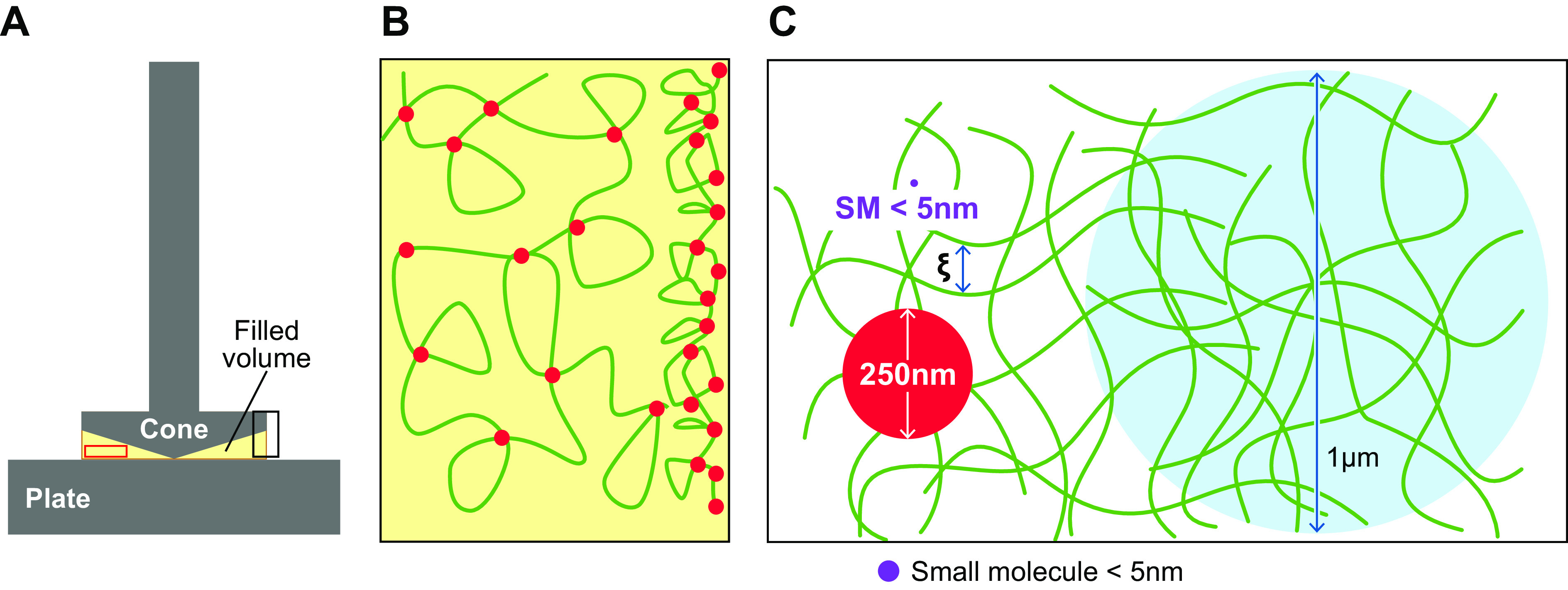

Mucus clearance constitutes the dominant mechanical host defense system of mammalian pulmonary airways (1–3). This system is required to protect the large proximal (bronchial) and smaller distal (bronchiolar) airways against the estimated 106–1010 bacteria and other particulates inhaled per day (4) (FIGURE 1A). It has been classically held since the 1930s that mucociliary clearance (MCC) reflects the movement of a mucus layer over a periciliary “sol” (liquid) layer in which cilia beat (5–7) (FIGURE 1Bi). This formulation, however, never adequately described why 1) a discrete mucus layer forms at all, e.g., why secreted mucins (100- to 300-nm radius of gyration) do not penetrate the interciliary spaces (250 nm) (8) and 2) how the mucus layer remains interactive with cilia under conditions of varying hydration, e.g., why the mucus layer does not “float” off cilia in periods of high airway hydration.

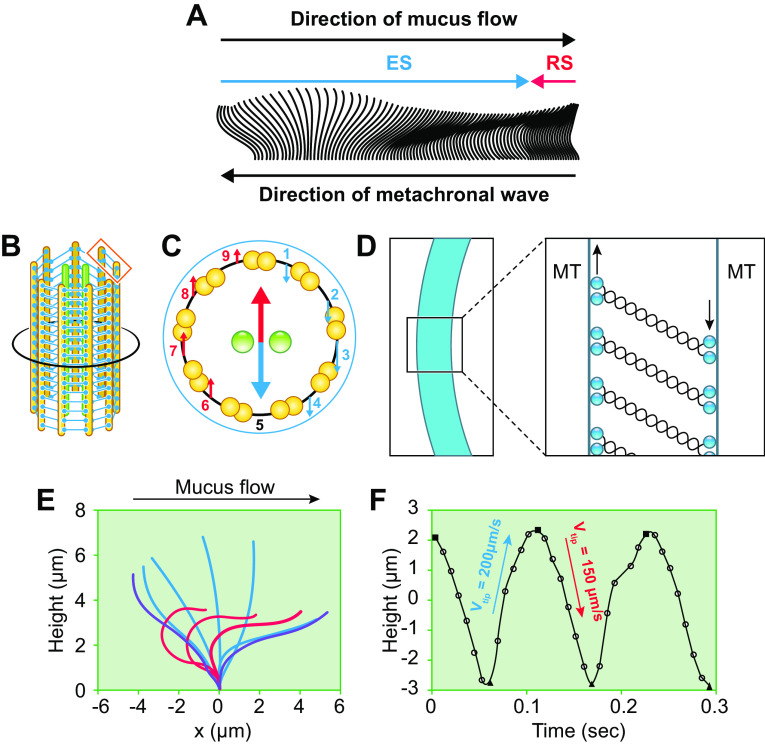

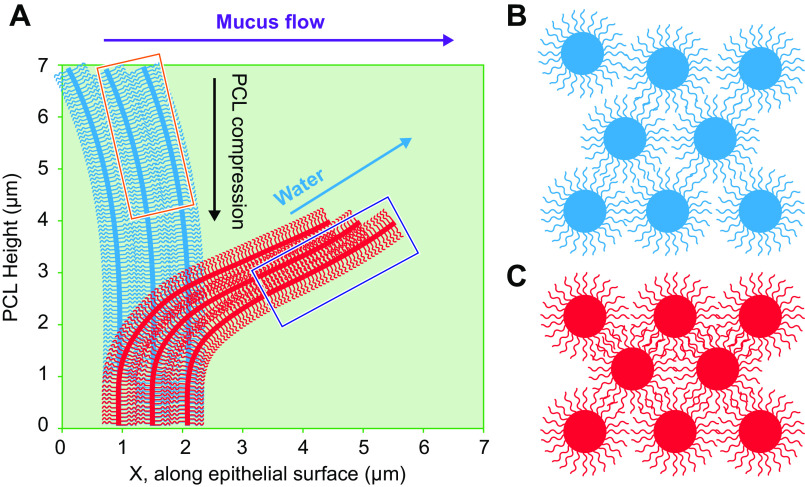

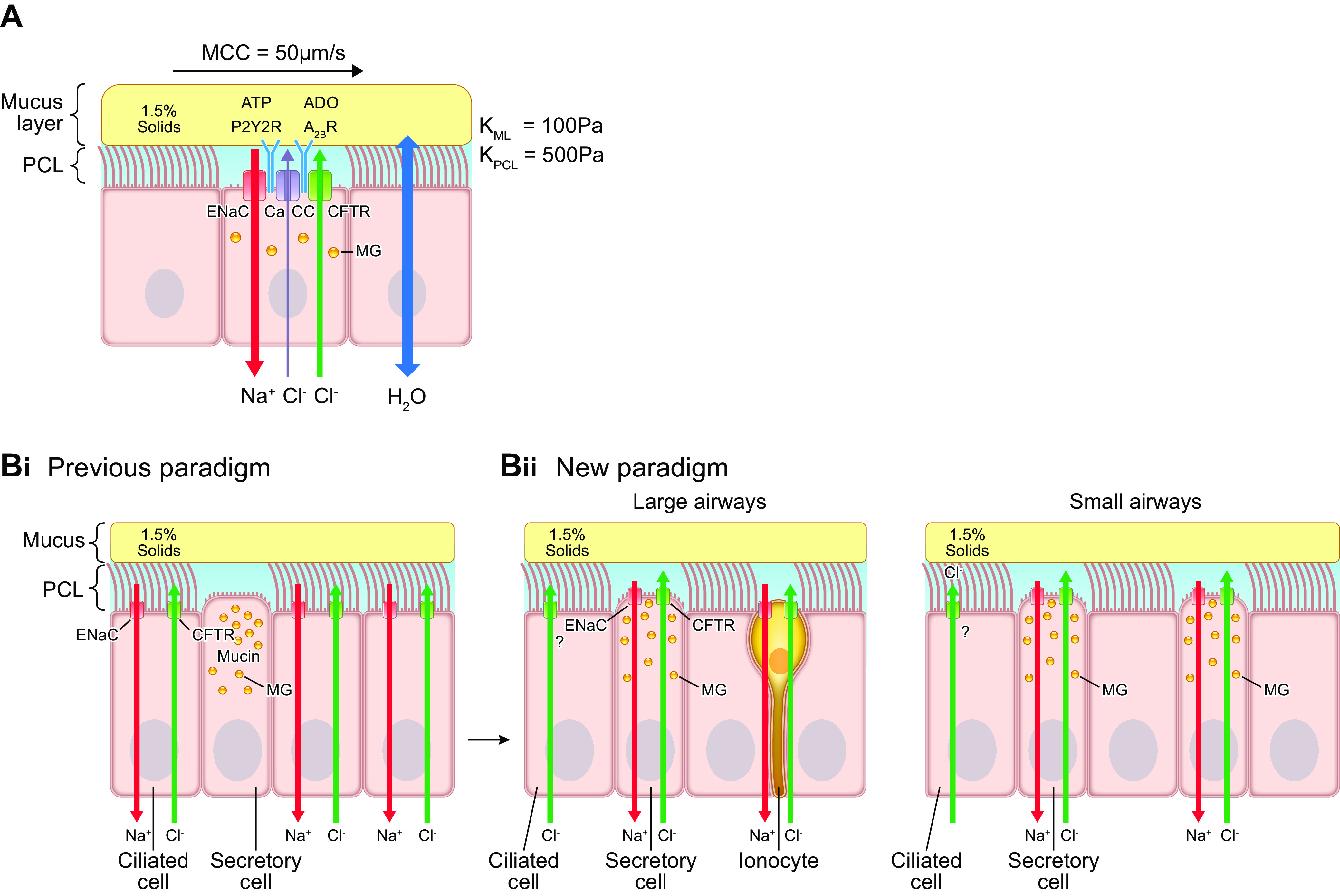

FIGURE 1.

Mucin organization macroscopically and microscopically in the normal lung. A: regional airway and submucosal gland (SMG) distributions in the lung. Large airways, also defined as bronchial airways, are characterized by airway cartilage and SMGs. Small airways, also defined as bronchioles, typically are <2 mm in diameter and without cartilage and SMGs. B: microscopic organization of the mucociliary apparatus. Bi: schematic representation of the classic gel-on-liquid model showing a mucus layer (comprised of gel-forming mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B) and the periciliary layer (PCL) as a liquid-filled “sol” domain (4, 5). Bii: gel-on-brush model depicting a MUC5B- and MUC5AC-populated mucus layer juxtaposed to PCL comprised of “brushlike” epithelial-tethered mucins MUC1, 4, 16, and 20 (not shown), and likely other large glycopolymers. C: MUC5B, MUC5AC, and club cell secretory protein (CCSP) mRNA coexpression is region specific. Top: hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)- and Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff (AB-PAS)-stained sections of 4 airway regions. Bottom: localization of MUC5B and MUC5AC with CCSP mRNAs by RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) in the 4 different regions of normal/healthy human airways. For cellular localization, MUC5B (green), MUC5AC (red), and CCSP (white) mRNAs were visualized by fluorescent RNA ISH. Single-color images were merged (“overlay”) and the overlaid images superimposed on differential interference contrast (DIC) images. In SMGs, mucus cells exhibited large mucin granules definable by AB-PAS staining (insets in H&E- and AB-PAS-stained sections). In primary bronchial superficial epithelium, 2 nonciliated CCSP+ epithelial cell types were identified: 1) a nonciliated epithelial cell with an AB-PAS-stained apical bulge (black arrowheads) and 2) a nonciliated epithelial cell without the apical bulge (white arrowheads). In distal bronchioles, nonciliated epithelial cells with dome-shaped apical bulges (black arrows) dominated. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 20 µm. D: quantification of cell types expressing MUC5B, MUC5AC, and/or CCSP mRNAs in different regions of normal/healthy human airways. Data are expressed as the number of each cell type per millimeter of basement membrane (BM). Solid bars and error bars represent mean ± 2 SD. n = 5. *P < 0.05 compared with every other cell type. E: distinct regional distributions of MUC5AC, MUC5B, and CCSP mRNA localization in superficial epithelium of the normal/healthy lung. Data represent the calculated % of total MUC5AC, MUC5B, or CCSP mRNA-stained volumes for each airway region. Total MUC5AC, MUC5B, or CCSP mRNA-stained volumes for each airway region were calculated by multiplying the mean values of the RNA ISH volume densities for each airway region obtained from 5 normal/healthy lungs by the predicted total surface area of corresponding airway regions. Images in B from Refs. 8 and 25 and used with permission from Science and New England Journal of Medicine, respectively. Images in C–E from Ref. 35 and used with permission from American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine.

With respect to disease, there never has been an accurate nomenclature, or predictive pathophysiological schema, to describe diseases of failed mucus clearance of the lung. Neither the term “chronic bronchitis” (CB), which describes the cough and sputum production clinically associated with these diseases, nor “hypersecretory diseases,” which describes airway goblet cell metaplasia pathologically, adequately captures the small airway-dominated mucus obstruction, inflammation, airway remodeling, and symptoms associated with these diseases (9–22). “Muco-obstructive lung diseases” perhaps is a preferred term (23).

This review describes advances in the biochemical and especially biophysical understanding of the mucus clearance system in health, covering both cilia-dependent (mucociliary clearance, i.e., MCC) and airflow-dependent (gas-liquid pumping, cough) mechanisms. Because of the importance of mucus concentration in mucus biophysics/function, interactions between secreted mucus and airway epithelial ion/fluid transport are covered. The review also considers the mechanisms by which mucus clearance fails and produces muco-obstructive diseases. Because of its unique pathophysiology, and a recent Physiological Reviews article (24), asthma is not the focus of this review. Rather, the review focuses on more “suppurative” muco-obstructive lung diseases, e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), cystic fibrosis (CF), and non-CF bronchiectasis (NCFB) (25). Finally, based on these novel concepts, general treatment paradigms for muco-obstructive diseases are reviewed.

2. MUCUS CLEARANCE

As reviewed below, mucus is a hydrogel with the biophysical properties required for transportability provided by the high-molecular-weight (MW) MUC5B and MUC5AC secreted mucins (26). The mucus clearance process in the lung can be viewed at multiple length scales. In this review, we start from the largest and proceed to more microscopic scales. In this context, we integrate mucus clearance across 1) lung-wide scales, describing the movement of mucus from the large surface area of small (bronchiolar) airway regions (∼1–2 m2) to the surface area choke point in third-generation proximal airways (∼ 50 cm2) (27); 2) cellular scales, i.e., microscopic (µm2); and 3) mucus mesh scales (10–100 nm) (28, 29).

2.1. Regions and Cell Types Mediating Mucin Secretion

Two high-MW polymeric mucins, i.e., MUC5AC and MUC5B, are the dominant secreted mucins that cover and are cleared from airway surfaces (30–33) (FIGURE 1B). A classic view of the mucociliary transport system assigned MUC5B secretion to the submucosal glands (SMGs) of the proximal airways, whereas the superficial epithelia of the proximal and distal airways were deemed the sites of MUC5AC secretion (20, 26) (FIGURE 1A). Recent data from mouse models, and, importantly, human studies, have led to a revision of this formulation (34, 35). In conditions of health, CCSP+ (SCGB1A1) club cells within the superficial epithelium of both human proximal and distal airways constitutively secrete MUC5B (FIGURE 1, C and D). Importantly, the club cell appears to constitutively secrete MUC5B via a small granule pathway (100 nm) (36, 37). The superficial epithelial MUC5B secretion is supplemented by MUC5B secretion from mucus cells within SMGs that may be in part tonic but likely can be greatly increased as part of the cough reflex (20, 38). A regional balance sheet of MUC5B secretion suggests that the distal small airways, because of their large surface area, dominate superficial airway epithelial MUC5B secretion in the healthy lung (FIGURE 1E). Notably, the capacity to secrete MUC5B in health disappears in the CCSP+ club cells in the most distal respiratory bronchioles (35). These club cells instead secrete a noncleaved form of surfactant protein B (SPB) and may buffer the alveolus from aspiration of secreted MUC5B (39, 40).

In contrast, the normal lung of humans or mice appears to secrete little MUC5AC in proximal airways and almost none distally (35, 41) (FIGURE 1, C and D). However, stresses to the lung, involving a wide spectrum of pathophysiologies, induce MUC5AC in the superficial epithelium (2, 32, 33, 42–49). Recent studies suggest that MUC5AC secretion is superimposed on CCSP+ club cells competent for basal MUC5B secretion, with intense upregulation of MUC5AC expression associated with metaplasia to a goblet cell phenotype and accumulation of intracellular mucin-containing granules ∼1 µm in diameter (35). The regulation of large granule/mucin secretion from goblet cells has been widely studied, and a number of G protein-coupled receptors trigger secretion via Ca2+- and phospholipase C-dependent mechanisms (32, 41). As implied by their definition, the regulation of secretion via the large granule pathway in goblet cells differs from the constitutive pathway in club cells (50, 51).

Finally, a balance sheet of mucin secretion and mucin clearance from the lung has not been established (52). Unlike surface active proteins in the alveolus, it has been assumed that there is no entero-airway cycle for mucins, i.e., secreted mucins are not recycled or proteolyzed by airway macrophages or epithelial cells as they traverse airway surfaces (53–55). Such an assumption needs to be tested. If true, it requires that all secreted mucins be cleared, and thus surface mucin fluxes have to increase from distal to proximal airway surfaces.

2.2. Macroscopic Anatomy of Mucus Clearance: Continuous vs. Discontinuous Layers

It is awkward that in 2022 a comprehensive description of the organization and topography of mucus transport macroscopically under basal or stressed conditions is not available. For example, it is not clear whether mucus lines airway surfaces as a continuous layer (“blanket”) or a discontinuous layer (“flakes,” “aggregates”) in health. Indeed, recent in vitro studies have questioned the need for a mucus layer at all for MCC (56, 57). Optical studies of the heavily glandular upper (nasal) airways support the notion that the mucus layer moves under basal conditions as a coordinated blanket in this region (58). However, data from the trachea, and especially more distal lower airways, are more mixed. Sturgess et al. (59) utilized scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to report that rabbit airways were covered by a continuous blanket/sheet. In the more distal airway of rodents, Iravani and colleagues (60, 61) reported from differential interference contrast (DIC) optical studies that mucus moves as flakes, i.e., insoluble masses of mucus 10–100 µm in diameter, that coalesced into larger aggregates as flakes moved proximally. Studies of clearance of inhaled radioactive particles from normal human lungs have reported data that are consistent with this notion (62).

More recently, studies have been performed in excised pig and human airways in which submucosal glands have been stimulated by cholinergic agonists, mimicking in part vagal-mediated cough reflex reactions to inhaled stressors. These studies have reported the differential transport of both a surface blanket (fast) and discontinuous “strands” or “bundles” (slow) emanating from glands (20, 63–66). The notion is that strands may function as “sweepers” to clear large particles deposited on upper airway surfaces. The use of inhaled fluorescent beads or deposited Alcian blue to visualize the strands raises the question of whether the strands were present de novo or reflect bundling of mucins in response to deposition of multivalent beads/Alcian blue. This experimental problem is difficult to resolve without internally labeled mucins because mucins are adapted to be highly interactive with, i.e., bind to, virtually any substance deposited on airway surfaces (see below).

A comprehensive description of the organization of mucus clearance in large and small airways will require more precise definitions of blankets, flakes, aggregates, and strands/bundles and new measurement techniques. Ultimately, the presence of blankets versus flakelike structures will be defined by a combination of experimental data and new theoretical concepts of mucus organization (23, 655). For example, recent experimental data suggest that entrainment and direction of cilia beat require continuous mucus sheets (67). In parallel, theoretical data suggest that newly secreted mucins may first localize via hydrophobic interactions at the mucus-air interface. It is as yet not clear whether mucin localization at the air-mucus interface is continuous (blanketlike) or discontinuous (flakelike). Thus, novel techniques to image the structure and concentration-dependent topological organization of mucins at the air-mucus interface will be a first step to ultimately describe the organization and topography of mucus on normal airway surfaces.

In human muco-obstructive disease, characterization of accumulated mucus in the lung should be easier to define, but data are limited because of the propensity to utilize intraluminal delivery of solutions to fix excised human diseased lungs. However, available human data and data from mouse models suggest that muco-obstruction occurs first in distal airways (bronchioles) as mucus plaques and intraluminal plugs (68–74).

2.3. Microscopic Anatomy of the Mucus Clearance Apparatus

The difficulties with the classic gel-on-liquid model led to a novel description of the mucociliary apparatus as comprised of a gel and a brush, i.e., a mucus layer and a periciliary/brush layer (PCL) (8) (FIGURE 1Bii). As with the classic model, a mucus layer is described that contains the secreted MUC5B and MUC5AC mucins and other molecules (see below). The important addition contributed by this model was the identification of a dense brush comprised of tethered cell surface mucins, including MUC1, MUC4, MUC16, and MUC20, and likely other large tethered biomolecules, on epithelial cell surfaces, microvilli, and cilia (8). The layers and how they interact are described below.

2.3.1. Mucus layer biochemistry and biophysics relative to airway function.

Normal human airway mucus is a hydrogel comprised of ∼97.5% water, 0.9% salt, ∼1.1% globular proteins, and ∼0.5% high-molecular-weight mucin polymers (30, 75). Note, we use 1.0% salt for simplicity in our calculations. We have historically defined the hydration status of mucus by the simple dry to wet weight content, i.e., dry weight/wet weight × 100 (% solids content) (14, 76). However, to describe the osmotic properties of the mucins and globular mucin proteins more accurately, the hydration status of mucus is better described as the wet-to-dry organic mucus content, i.e., the organic percent solids [(dry weight/wet weight) × 100% − 1% salt], and/or the absolute mucin concentration estimated by physical refractometry techniques (76, 77) (TABLE 1). The correlation between the gravimetric and physical measurements over a range of normal and disease values appears tight, so both measures are accurate (76). More recently, mass spectroscopy-based measures of the mucin sialic acid content, ratioed to urea, have also been reported and appear to correlate well with absolute mucin values and percent organic solids contents (78).

Table 1.

Metrics and values to describe mucus hydration/concentrations

| %TS | %OS | cos, mg/ml | cm, mg/mL (20%OS) | cm, mg/mL (50%OS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.25 | 0.25 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 1.25 |

| 1.5 | 0.5 | 5 | 1 | 2.5 |

| 2.0 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| 2.5 | 1.5 | 15 | 3 | 7.5 |

| 3.0 | 2 | 20 | 4 | 10 |

| 3.5 | 2.5 | 25 | 5 | 12.5 |

| 4 | 3 | 30 | 6 | 15 |

| 4.5 | 3.5 | 35 | 7 | 17.5 |

| 5 | 4 | 40 | 8 | 20 |

| 5.5 | 4.5 | 45 | 9 | 22.5 |

| 6 | 5 | 50 | 10 | 25 |

| 6.5 | 5.5 | 55 | 11 | 27.5 |

| 7 | 6 | 60 | 12 | 30 |

| 7.5 | 6.5 | 65 | 13 | 32.5 |

| 8 | 7 | 70 | 14 | 35 |

| 8.5 | 7.5 | 75 | 15 | 37.5 |

| 9 | 8 | 80 | 16 | 40 |

| 9.5 | 8.5 | 85 | 17 | 42.5 |

| 10 | 9 | 90 | 18 | 45 |

The hydration of mucus was initially reported as the percentage of a mucus sample that was not water, i.e., its percentage of total solids (%TS), calculated as dry weight/wet weight × 100 (8, 14, 76). Since mucus samples are typically isotonic, it is more informative to characterize the composition of mucus in terms of organic molecules that contribute to the osmotic pressures/moduli of mucus, i.e., the percentage of organic solids (%OS). To calculate %OS, the salt contribution of an isotonic liquid is subtracted from the total % solids, i.e., dry weight − 1% salt/wet weight × 100. For simplicity, we have approximated the salt contribution to total solids in Table 1 as 1% rather than 0.9%. The %OS can be converted to the overall concentration of organic solids (cos) as 1%OS = 10 mg/mL. The concentration of mucins (cm), the main gel-forming molecules in mucus, accounts for between 20% and 50% of the total cos in differing normal vs. disease states (76, 77, 79, 80).

2.3.1.1. fluid/solvent content of mucus: role of high airway epithelial water permeability.

The salt and water component of mucus is the product of the active ion transport and water permeability properties of the underlying airway epithelia. The airway surface liquid (ASL) under resting conditions is isotonic with respect to plasma (81–84). This property reflects the high water permeability (∼5 × 10−3 cm/s) of airway epithelia (83, 85–88) that is mediated in part by airway epithelial expression of aquaporins 3, 4, and 5 (89, 90). The ionic composition of the ASL/fluid component of mucus differs modestly from plasma (in mM): Na+ = ∼110 mM (plasma ≈ 140 mM); K+ = ∼30 mM (plasma ≈ 5 mM); Cl− = ∼110 mM (plasma ≈ 100 mM); = ∼30 mM (plasma ≈ 25 mM); and Ca2+ = ∼4 mM (2 mM bound; 2 mM free) (plasma Ca2+ ≈ 8–10 mM) (81). The raised K concentration reflects secretion by apical K+ channels that are coupled to epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) activity via apical membrane electrochemical driving forces (83). The biologic role for the increased K+ concentrations is unknown, but extracellular K+ concentrations can regulate the rates of ATP release from pannexin I channels (91).

In addition to maintaining an isotonic ASL under resting conditions, the high water permeability of the airway epithelium is physiologically well adapted to replace water lost from proximal airway surfaces due to humidification of inspired air (83, 86, 92–94). For example, the evaporative loss of water from proximal airway surfaces during respiration can raise ASL osmolality/tonicity. The net result of the evaporation-induced increases in ASL osmolality/tonicity is to osmotically draw water into the lumen from the interstitium to replace evaporative water loss. The pathways that mediate airway surface water replenishment, however, are complex. Notably, the raised luminal osmolality is presented to an airway epithelium with asymmetric apical versus basolateral cell membrane water permeabilities (95, 96). Specifically, the high apical membrane versus low basolateral membrane water permeability produces cell shrinkage in response to luminal hyperosmolality, i.e., water flows faster from the cell across the apical membrane to the hyperosmolal lumen than water flows across a less water-permeable basolateral membrane into the hypertonic/hyperosmolal cytoplasm (94). Hence, the epithelium acts as an osmotic cell volume sensor to sense luminal ASL osmalality (96). The effector elements responding to luminal hyperosmolality-induced airway epithelial cell shrinkage include the synthesis and release of nitric oxide (NO) to the basolateral compartment. NO triggers an increase in submucosal blood flow that ensures adequate water availability to replenish airway surface evaporative water losses (97).

2.3.1.2. mucin polymer content of mucus.

The mucin polymers are extraordinary in size and impressive in their oligosaccharide content, i.e., ∼75% of total mucin mass (26, 98) (FIGURE 2A). Inserted between the NH2 and COOH termini are serine-threonine-rich domains that are heavily glycosylated with sugar side chains ranging from 2 to 12 sugars in length that are often terminally capped with negatively charged sialic acid or sulfate molecules (4, 99). The glycosylation domains of the secreted mucins provide 1) sites (hydroxyls) for hydration; 2) a combinatorial library of binding sites capable of binding virtually any inhaled material with a low but sufficient binding affinity to mediate clearance (100); and 3) the negative charges that make mucins negatively charged polymers. Cysteine-rich (CYS) domains are interspersed within the serine-threonine-rich domains and may provide hydrophobic regions for noncovalent intermucin and intramucin associations (101).

FIGURE 2.

Characteristics of airway mucins. A: domain structures and relative sizes of the secreted mucins (MUC5AC and MUC5B) and tethered mucins (MUC1, MUC4, and MUC16). For reference, the globular protein albumin (ALB) is shown. The secreted mucins are composed of macromonomers with NH2 (N) terminals (MUC5AC, green; MUC5B, light blue), glycosylated domains, and COOH (C) terminals (MUC5AC, yellow; MUC5B, purple). Both the terminal C-C dimers and terminal N-N multimers are linked by cysteine-mediated S-S bonds. Note the molecular mass of the MUC5AC and MUC5B multimeric mucins typically exceeds 250 MDa. The tethered mucins have cytoplasmic NH2-terminal (dark gray), transmembrane (yellow), and heavily glycosylated extracellular domains (blue). For simplicity, unique domains and proteolytic cleavage sites are not shown. Estimated molecular weights are for the glycosylated forms of the secreted mucin macromonomers and tethered mucins. B: schematic of mucin glycoprotein macromonomer domains and sizes. Relationships of NH2- and COOH-terminal domains, cysteine-rich domains, and glycosylated domains not depicted to scale. C: biosynthesis of dimers in endoplasmic reticulum and multimers in the Golgi apparatus, respectively. Classic nonassociating mucin polymer shape depicted. A contains content from Ref. 25 and is used with permission from New England Journal of Medicine.

The individual mucin subunits, often called “macromonomers,” are composed of major domains required for specialized functions (FIGURE 2B). The NH2 and COOH termini are large domains, likely heavily folded, that contain von Willebrand-like domains (D domains) important for multimerization (FIGURE 2B). Mucin macromonomers are disulfide-linked via their COOH-terminal domains to form dimers before translocation to the Golgi, where they are disulfide-linked via their NH2-terminal domains, producing very large multimers (30, 32, 102–105).

Gene-targeted mouse studies have described important aspects of basal and regulated functions of Muc5b and Muc5ac. For example, Muc5b-knockout (KO) mice exhibit an absence of respiratory tract MCC and exhibit routine upper airway phenotypes (otitis media, nasal mucus plugs). The pulmonary phenotype of Muc5b-KO mice under naive conditions reflects the inability to clear intermittent aspiration (gastric or upper airway) and presents with a spectrum of disease ranging from health to sporadic fatalities. In contrast, no defects in MCC or spontaneous clinical phenotypes were detected in Muc5ac-KO mice (106). Subsequent studies of Muc5ac KO mice exposed to inhaled allergens, however, revealed the highly important role of Muc5ac in response to inhaled stresses (107–109).

There are likely differences between MUC5B and MUC5AC structure and function that explain the need for “two mucins.” For example, there are subtle differences in the NH2- and COOH-terminal domain structures of MUC5AC and MUC5B, numbers of Cys domains, VNTR lengths, and possibly domain-structure multimerization (33, 110, 111). MUC5B is a linear multimer of mucin macromonomers in size (∼2.5 MDa) that varies from 2 to ≥100 macromonomers [up to 50 µm in length and 250 MDa in mass (102, 112, 113)]. The covalent linear versus branching status of MUC5AC is not yet resolved but may exhibit linear and trimeric structures (114). Future studies are required to elucidate the functional aspects, e.g., adhesive interactions, of each mucin that may account for their distinct functions (115).

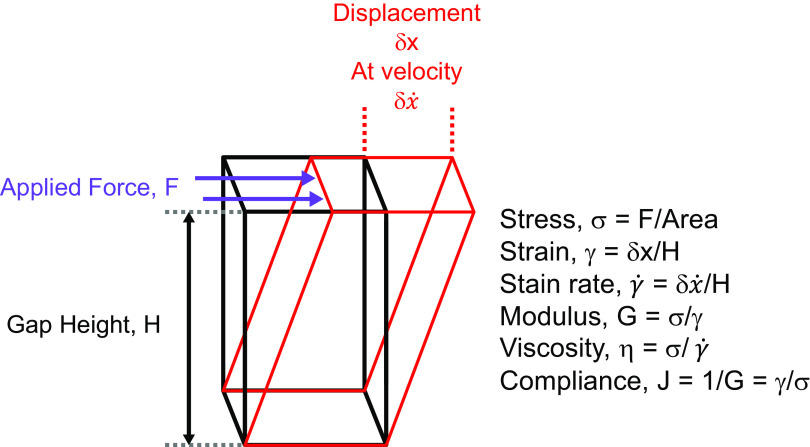

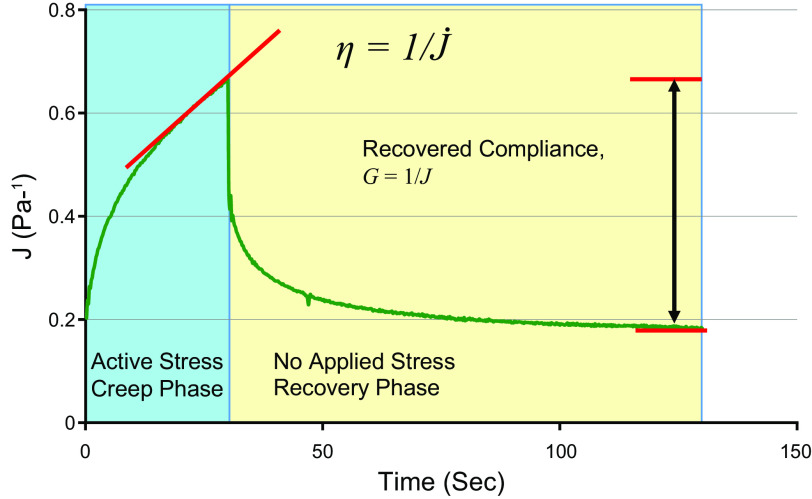

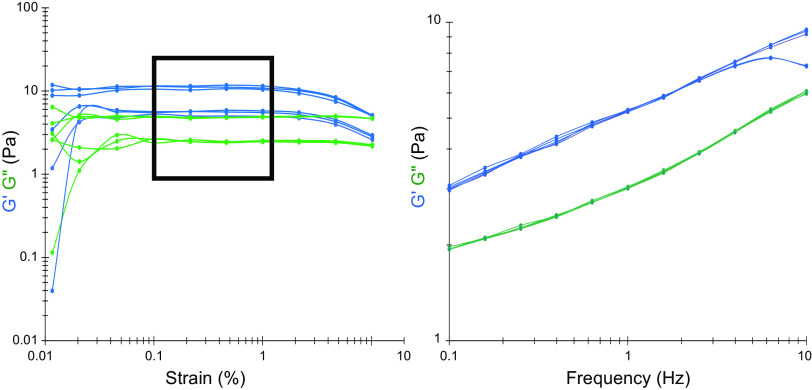

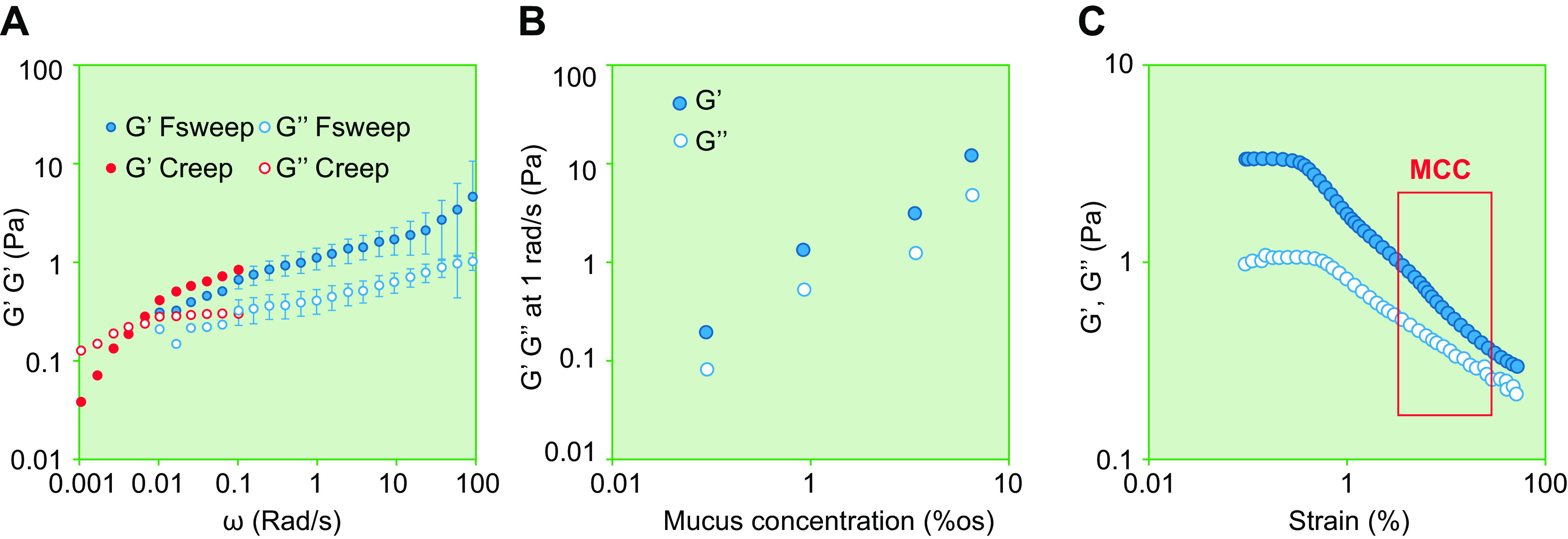

2.3.1.3. mucus biophysical properties.

The mucin polymers dominate the mucus biophysical properties required for efficient mucus clearance from the lung. The functional properties of mucus can be described by concepts from polymer physics that predict not only the viscoelastic properties of mucus but also other key biophysical properties, including the mucus osmotic modulus and adhesive, cohesive, and frictional properties (8, 29, 116). The biophysical properties of mucus related to transport, as with other polymers, scale to higher-order powers of mucin concentration (8). This feature of mucus predicts that relatively small changes in mucin/mucus concentration will produce profound effects on its biophysical and transport properties. In addition, the properties of mucus gels can be modified by conditions that generate interactions between adjacent mucin polymers and generate intermucin bonds of varying strength and durations (117–119). These interactions between associating polymers can produce “sticky” gels whose viscosity can scale as high powers of polymer concentration, e.g., with exponents as high as 6.8–8.5 (120).

2.3.1.4. mucin functions independent of biophysical properties.

Robust data suggest that secreted mucin polymers also have roles in host defense that are not directly related to their biophysical properties (98, 100, 121, 122). For example, the complex glycans associated with mucins may directly modify/limit bacterial pathogen virulence (121). Low-affinity, but high-abundance, interactions between bacteria and mucins, or between bacteria, immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG), and mucins, may increase the efficiency of clearance of bacteria from the lung via the mucus clearance pathway (56, 69, 123–125). Recent studies indicate that bacteriophage IgG-like folds may anchor phages to mucus, providing for an expanded role in mucus antimicrobial activities (126, 127).

In addition, mucin molecules organize a robust globular protein interactome. A substantial percentage (∼33%) of globular proteins in mucus may be bound to mucins under physiological conditions (113). Most of these proteins are involved in airway host defense (113) and include 1) antimicrobial proteins, e.g., LPLUNC, defensins, DMBT1, lysozyme, and C3; 2) antioxidant proteins, e.g., glutathione S-transferase, peroxiredoxin, and superoxide dismutase; and 3) cell signaling proteins, e.g., S100 and transgelin (113). The importance of the globular protein-mucin interactome was observed in studies in which a mouse model of chronic muco-obstructive disease (βENaC mice; see below) was crossed with Muc5b-KO mice (128). A predicted decrement in mucus accumulation was observed. However, this beneficial effect was offset by a loss of Muc5b-organized host defense functions as reflected in increased inflammation that produced a more severe phenotype in βENaC/Muc5b-KO than βENaC mice (128).

2.3.2. Periciliary layer-glycocalyx biochemical and biophysical properties.

The apical cell surfaces of respiratory epithelia are lined by another class of mucins, i.e., the tethered mucins (FIGURES 1Bii and 3Ai). The presence and functional importance of these mucins were first studied in detail in the ciliated cell (8, 113). These studies revealed that ciliated cells exhibit robust expression of MUC1 on microvilli, MUC4 on all aspects of the cilia shaft, and MUC16 on distal portions of the ciliary shaft. Because these tethered mucins are highly expressed in ciliated cells, they are part of the “periciliary layer” (PCL), and their biophysical (osmotic modulus) and molecular sieving (barrier) properties have been intensively studied (8). For example, the PCL brush exhibits osmotic forces that prevent dehydration by the osmotically active mucus layer (see below). The dense PCL brush also restricts entry of infectious/toxic particles with molecular radii > 40 nm into the layer, and its barrier properties become even more impressive near the cell surface, where only particles <5 nm (i.e., 5-nm mesh size) can reach the cell surface (FIGURE 3A). In addition to molecular barrier features, cell surface mucins have substantial roles in modulating inflammatory/immune responses to pathogens and likely signal via their EGF-ligand domains to regulate epithelial repair (14, 37, 129–132).

FIGURE 3.

Properties of the periciliary layer-glycocalyx (PCL-G). A: mesh properties of the PCL-G. Ai: diagram depicting strategy to measure by confocal microscopy the molecular size sieving/permeability properties of the PCL-G. Fluorescent dextrans of varying sizes (radius of gyration, Rg) are utilized to 1) penetrate the PCL-G and define the epithelial surface (red dextran, Rg = 1 nm) and 2) characterize the graded mesh size/permeation characteristics of the PCL-G (larger green dextrans, Rg = 5–100 nm). Aii: X-Z confocal image of human airway cultures exposed to a small (1-nm Rg) red dextran with a graded series of larger (in nanometers) green dextrans. Aiii: graph depicting PCL height (z-axis) as defined by restriction of dextran probe (blue circles) access [exclusion zone (z)] to the cell surface. A similar relationship between size and PCL exclusion distance was observed with 20- and 40-nm nanoparticles (red triangles). The PCL-excluded molecules with Rg ∼40 nm are at the top of the PCL (the boundary) and define PCL height, and molecules with Rg ∼ 5 nm are near the cell surface. Note closer to the cell surface (lower z-axis number), the mesh becomes “tighter,” i.e., more restrictive. The PCL mesh size, i.e., correlation length (ξ), varies with the distance from the cell surface (z) as ξ = 17.5 nm·ln[7 µm/(7 µm–z)] where 17.5 nm was used as the average ξ for the PCL (blue line). B: properties of cell surface glycocalyx on nonciliated cells. Bi: forest plot depicting levels of RNA expression in major airway epithelial cell types based on single-cell RNA sequencing (RNAseq) experiments (35). Bii: comparison of height of PCL on ciliated cell (left, blue) and PCL-G on adjacent secretory cell (right) utilizing X-Z confocal imaging of dextran permeation. Green probe = 40 nm; red probe = 5 nm. Content in Ai to Aiii from Ref. 8 and used with permission from Science.

More recently, it has been recognized that tethered mucins are expressed on the apical surface of all lumen-facing airway epithelial cells. For example, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) studies have revealed expression of MUC1, 4, 16, and 20 in secretory as well as ciliated cells (133) (FIGURE 3Bi). Confocal imaging studies have also identified the predicted molecular sieving properties of tethered mucins on the luminal surface of secretory cells (FIGURE 3Bii). Because tethered mucins dominate the PCL on ciliated cells and the “glycocalyx” (G) lining surfaces of secretory airway epithelial cells, the term “PCL-G” may best capture the widespread expression of tethered mucins on different luminal airway epithelial cell types (113). A focus on the PCL of the ciliated cell, however, is useful in analyses of muco-ciliary transport.

2.4. Mucus/PCL Osmotic Properties and Relationships to Health and Disease

Important concepts emerged from the gel-on-brush hypothesis that focused on the osmotic properties of polymer gels, solutions, and brushes, including mucins/mucus and the PCL. The osmotic pressure of the mucus layer was the first parameter to be directly measured and is discussed in this section. The subsequent measurements of PCL osmotic properties, and the relationships between the mucus layer and PCL osmotic properties, are also topics of this section.

2.4.1. Measurement of mucus layer osmotic pressure.

The osmotic pressure (Π) of a medium containing many components, e.g., the mucus layer, is defined by the rate of change of the free energy (F) of the medium upon changing its volume (V), when the number (Ni) of its components, e.g., mucin molecules and other globular proteins, is kept constant. These relationships can be described analytically as follows:

| (1) |

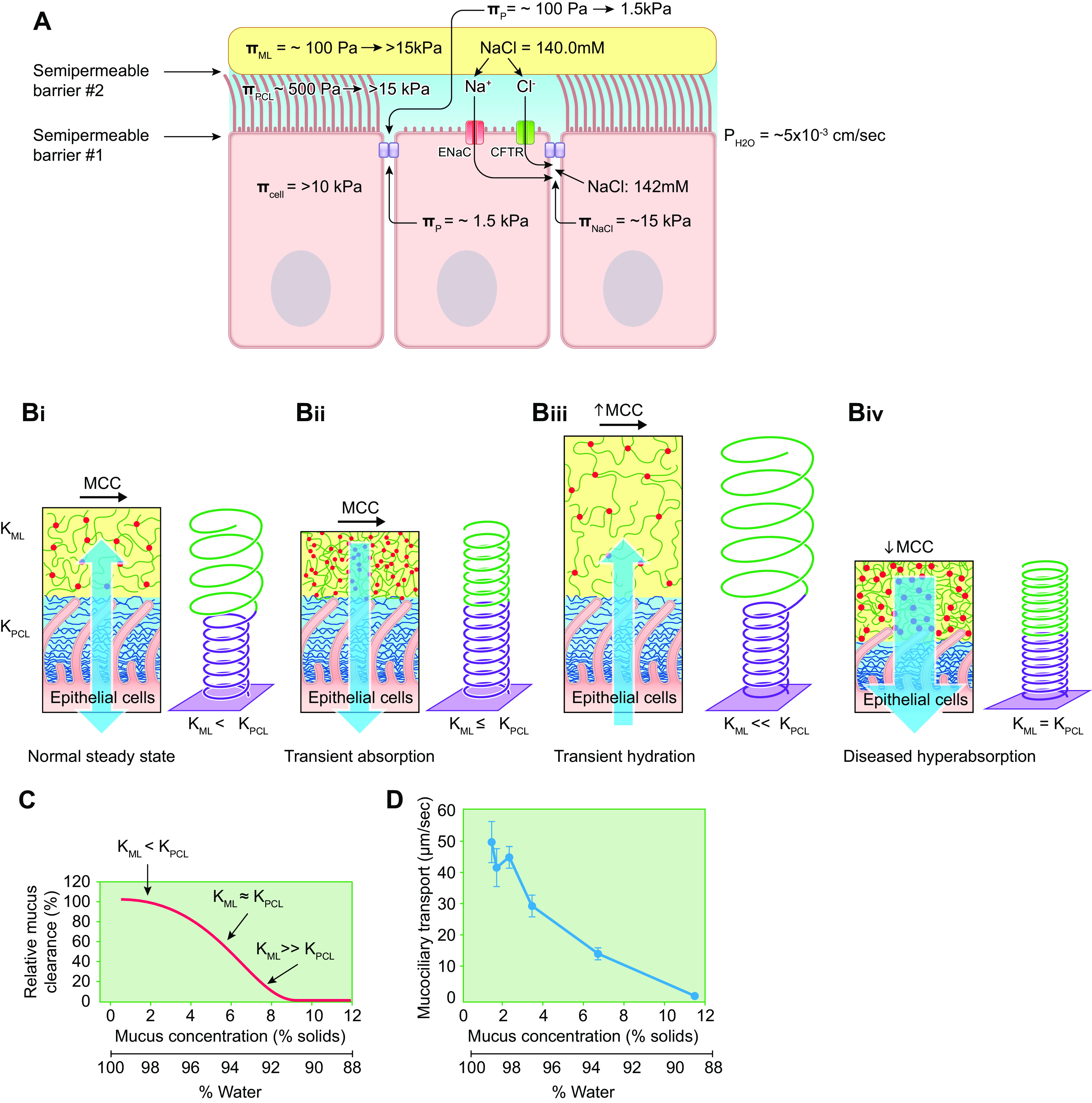

The osmotic pressure of the mucus layer (ΠML) is measured experimentally utilizing an osmometer that consists of hemichambers separated by a semipermeable membrane that allows solvent (water) and small solutes (salt, small proteins), but not larger solutes, e.g., mucins and large proteins, to pass through it (FIGURE 4A). The force per unit area exerted by mucus in one hemichamber, separated by a semipermeable membrane from the second hemichamber containing the solvent and salt, is measured by a pressure sensor as the osmotic pressure. Accordingly, the measured osmotic pressure difference reflects the contributions of all the solutes unable to permeate the semipermeable membrane. A typical measurement of osmotic pressure of cultured human bronchial epithelial (HBE) mucus with a 10-kDa semipermeable membrane as a function of mucus concentration is shown in FIGURE 4Di.

FIGURE 4.

Mucus and PCL osmotic pressures. A: diagram of device modified to measure mucus osmotic pressure. Upper and lower hemichambers and pressure sensor depicted. A semipermeable membrane separates the hemichambers. B: depiction of the mucus layer-PCL interface as the semipermeable boundary separating the mucus layer and PCL compartments. C: concentration-dependent mucin polymeric interaction regimes. Ci: in the dilute regime, the mucin polymers are separated by distances greater than their size, Rg. Cii: at the overlap concentration (c*), the mucins polymers are separated by a distance on the order of their size, i.e., they just “touch.” Ciii: in the semidilute/interpenetrating regime, the centers of mass of mucin polymers are separated by distances smaller than their size, and thus mucins overlap with one another, i.e., interpenetrate (134). The average distance between nearest sections of mucin polymers is the correlation length (ξ), i.e., a measure of concentration. D: human bronchial epithelial (HBE) mucus osmotic pressure without and with fractionation by preparative chromatography into large molecular (“mucin”) and small molecular (“nonmucins” such as globular proteins) fractions. Di: measurement of total mucus osmotic pressure utilizing a 10 kDa semipermeable membrane of intact HBE mucus as a function of mucus concentration (total organic solids). Dii: measurements of the contributions of the mucin and globular protein fractions to HBE mucus osmotic pressure as a function of concentration. Cos, total organic solids concentration; Cm, mucin concentration; Cp, globular protein concentration. Osmotic pressure measurements of each component were performed utilizing 10 kDa MW cutoff semipermeable membranes. Blue dashed line is fitted to globular protein (Cp) measurements using the Van’t Hoff equation (Eq. 2) that predict a globular protein MW (i.e., number average protein mass, Mp) of 66 kDa. The red dashed line to the left of c* (0.6 mg/mL) depicts the osmotic pressure of mucins in dilute conditions (cm < c*) calculated from Eq. 2 with predicted mucin MW (i.e., number average mucin mass, Mm) = 100 MDa. The osmotic pressure values for mucin concentrations (cm) above c* are fitted by the dashed red line generated by the power law term of Eq. 3 describing the osmotic pressure of semidilute mucin solutions. (Courtesy Dr. Phillipe Lorchat.) E: PCL osmotic pressure. PCL height (distance of PCL surface/boundary to epithelial cell surface) dependence on PCL osmotic pressure (ΠPCL) as measured by PCL osmotic compression in response to luminal high-molar-mass dextran polymer administration (black symbols/line). Red line depicts PCL height dependence on osmotic pressure (Eq. 6) estimated from the height-dependent tethered mucin mesh size (ξ) variation within the PCL layer (see equation in legend for FIGURE 3Aiii). See glossary for other abbreviations. E uses content from Ref. 8, with permission from Science.

There are important technical and interpretative aspects of the measurement of the mucus layer osmotic pressure that must be addressed. On the airway surface, the mucus layer is apposed to the PCL (FIGURE 4B). The boundary between the two layers is analogous to the “semipermeable” membrane. Accordingly, the osmotic balance between the mucus and PCL layers is determined by macromolecules larger than the mesh size of the semipermeable PCL brush layer boundary (20–40 nm). Virtually all globular proteins in the mucus layer are smaller than the PCL boundary mesh size and freely exchange between the mucus and PCL layers (8). Therefore, the globular proteins that constitute the majority (∼2/3) of the organic component of mucus by weight do not contribute to the osmotic balance between the mucus layer and PCL. Unfortunately, semipermeable membranes for use in osmometers are not available in the very large molecule discrimination size ranges relevant to the PCL-mucus layer boundary. Therefore, the mucus layer osmotic pressure is typically measured with an osmometer equipped with a standard (10 kDa) semipermeable membrane, i.e., a membrane with a much smaller mesh size than the mucus layer-PCL boundary. The use of a 10-kDa semipermeable membrane renders some mucus layer globular proteins unable to penetrate the membrane, and hence they contribute to the experimentally measured mucus layer osmotic pressure (ΠML). Even with commercially available 100-kDa semipermeable membranes, mucus osmotic pressures higher than generated at the mucus layer-PCL interface are measured because 100-kDa semipermeable membranes also retain more globular proteins than are retained at the mucus layer-PCL boundary. Accordingly, let us consider the quantitative contributions of globular proteins to the experimentally measured mucus layer osmotic pressure.

The contribution of the globular proteins larger than the mesh size of the semipermeable membrane to the measured osmotic pressure of the mucus layer follows the Van’t Hoff law as

| (2) |

where cp is the concentration of the larger globular proteins, R is the molar gas constant (R = 8.314 J/K mol), T the absolute temperature, and Mp the number average protein mass (in grams/mole) (FIGURE 4Dii, blue dashed line). Thus, given knowledge of size (Rg) and concentration of globular proteins, coupled to the characteristics of the experimentally selected semipermeable membrane, the contributions of globular proteins to the measured mucus layer osmotic pressure can be calculated (see Eq. 2, FIGURE 4, Di and Dii).

2.4.2. Contributions of mucins to mucus layer osmotic pressure.

Because virtually all mucins are larger than any device semipermeable membrane, mucin osmotic properties can be measured by conventional device semipermeable membranes. However, the osmotic behavior of mucins in solutions is more complex than for globular proteins, as mucin osmotic properties strongly depend on the mucin concentration (cm). A parameter that describes the dramatic change in mucus osmotic behavior with concentration is termed the mucin “overlap concentration” (), the concentration at which mucins are forced to “touch” one another in solution (FIGURE 4Cii).

Below overlap concentrations, i.e., in dilute mucin conditions (cm < ), in which mucins do not physically “touch”/overlap (FIGURE 4Ci), the osmotic pressure of mucins (Πm) obeys the Van’t Hoff law as written for mucins from Eq. 2, i.e., , where Mm is the number average mucin mass (in grams/mole). Thus, the combined mucin and protein osmotic pressure measured by an osmometer with a relatively small mesh size (e.g., 10 kDa) at dilute mucin concentrations (cm < ) is

| (3) |

where ΠML, cp, Mp, cm, and Mm are as defined above. As noted below, the contribution of Πm to ΠML is so small in dilute conditions that Πm can be typically ignored.

The contributions of mucins to mucus osmotic pressures at mucin overlap concentrations can be estimated based on the physical characteristics of mucins (FIGURE 4Cii). The overlap concentration for mucins () in the mucus layer is estimated as , where the radius of gyration (Rg) quantitates mucin size (FIGURE 4Ci). The c* of HBE mucins, with Mm = 1 × 108 g/mol, i.e., 100 MDa (corresponding to 40-mer) with an Rg = 400 nm, is calculated to be ∼0.6 mg/mL, equivalent to ∼0.18% mucus organic solids (cos). The calculated osmotic pressure of mucins, with mass Mm = 1 × 108 g/mol at concentration cm = 0.6 mg/mL, in the mucus layer at c* is only 0.015 Pa (see Eq. 2), i.e., too small to be experimentally measured or have an effect on the PCL.

The concentration dependence of mucin osmotic pressure changes dramatically when mucins exceed overlap concentrations in the mucus layer, i.e., cm > (FIGURE 4Ciii). In this regime, new “semidilute” osmotic relationships emerge that reflect interactions between interpenetrating mucins (depicted in the steep component of the dashed red line to the right of c* in FIGURE 4Dii). The measured concentration (cm) dependence of mucin osmotic pressures (Πm) above the overlap concentration can be fitted in terms of cm, , and Mm. Combining dilute (Eq. 3) and semidilute/interpenetrating expressions for the osmotic pressure of mucins into a single approximate expression, we write

| (4) |

The first term (linear in concentration dependence) corresponds to a dilute (Van’t Hoff) mucin regime (Eq. 3). The second term (power law) reflects the contribution of interactions between semidilute/interpenetrating mucins. The power law exponent α describes the concentration-dependent contributions of semidilute mucins to osmotic pressure, i.e., (i.e., mucin concentration raised to the power of α). From data in FIGURE 4Dii, the exponent α for mucins in semidilute concentration ranges is calculated as 2.7. This large exponent reflects the strong concentration dependence of mucin osmotic pressure. For example, increasing mucin concentration by a factor of 5 leads to an osmotic pressure increase by a factor of 100 ! Note that Πm can also be estimated from the correlation length ξ (FIGURE 4Ciii), another measure of mucin concentration, as

| (5) |

2.4.3. Combined contributions of globular proteins and mucins to mucus layer osmotic pressure.

The experimentally measured osmotic pressure of the mucus layer (ΠML) increases linearly as a function of concentration in dilute regimes up to mucin overlap conditions ( ≈ 0.6 mg/mL or ≈ 1.8 mg/mL) (FIGURE 4, Di and Dii). As noted above, the value of Πm of mucins in the mucus layer remains relatively small compared with the osmotic pressure required to collapse the PCL even in the normal healthy mucus layer concentration ranges: Πm = 1.5 Pa at cm = 3.3 mg/mL or cos = 10 mg/mL (FIGURE 4Dii). Thus, the experimentally measured (with 10-kDa membrane) values of mucus layer osmotic pressure of a normal healthy mucus layer are dominated by globular proteins and therefore provide relatively little information about the osmotic pressure of the mucus layer relevant to PCL osmotic compression. However, Πm of mucins in the mucus layer strongly increases as a function of mucin concentrations (cm) above , reaching levels that may osmotically compress the PCL in disease states (FIGURE 4, Di and Dii). For example, if mucin concentrations increase by a factor of 6 to cm ≈ 20 mg/mL corresponding to diseased mucus with cos ≈ 60 mg/mL (i.e., 6% organic solids), the mucin osmotic pressure becomes Πm = ∼200 Pa. This value is close to the pressure at which mucins in the mucus layer begin to compress the PCL brush (see below). Accordingly, the experimentally measured ΠML is more informative with respect to PCL compression/mucus transport rates at total organic solids values in the range of disease, e.g., > 6% organic solids.

It is important to note that when mucus layer concentrations are raised by a factor of 6, the small globular protein concentration (cp) will be ≈ 40 mg/mL and the small protein osmotic pressure (Πp) will be ≈ 1,500 Pa. As noted above, the osmotic pressure generated by the small globular proteins does not compress the PCL because small proteins freely permeate the PCL. The small proteins, however, do not permeate cell membranes and hence compress the cell membrane, producing shrinkage of cell volume (see discussion in sect. 2.3).

2.4.4. Measurement of the PCL osmotic pressure.

In contrast to the ability to extract the mucus layer from culture surfaces or collect expectorated mucus for measurements of osmotic pressures with in vitro devices (FIGURE 4A), PCL osmotic properties had to be measured in situ in cell cultures, and novel techniques were developed to make these measurements (8).

Direct measurements of PCL osmotic pressure (ΠPCL) were performed by exposure of washed airway epithelial culture surfaces to solutions of polymeric dextrans with defined osmotic pressures and molecular weights much larger than the PCL mesh size. PCL heights were measured when equality between the applied polymeric solution and PCL osmotic pressures was achieved (8) (FIGURE 4E, black symbols/lines). This technique identified the onset of PCL compression (reduced PCL height) at polymeric dextran osmotic pressures of ∼350 Pa. A nonlinear relationship was observed between the osmotic pressure applied by the test polymeric dextran solution and PCL height/compression over the range of applied osmotic pressures (FIGURE 4E). This behavior in part represents the occupancy of the PCL by two components, an osmotically compressible grafted mucin brush and elastically deformable/bendable cilia.

Measurements of dextran size permeation properties were also utilized to estimate the contribution of tethered mucins to PCL osmotic pressure (ΠPCL). This approach utilized measurements of the correlation lengths (ξ), i.e., the mesh size, of the tethered mucins in the PCL; see FIGURE 3Aiii (8). A simple estimate of the average osmotic pressure of the PCL can be calculated from Eq. 5 utilizing an average PCL correlation length of 17.5 nm (see FIGURE 3Aiii). This estimate yields a PCL osmotic pressure of ∼180 Pa. However, the osmotic pressure of the PCL varies as a function of the PCL depth, reflecting the higher tethered mucin concentration toward the cell surface and hence smaller correlation length (FIGURE 3Aiii). Measurement of the correlation length profile ξ(z) within the PCL layer (FIGURE 3Aiii) allows simple estimates of 1) the relation between PCL correlation length and osmotic pressure ξ ≈ [3kT/(4πΠPCL)]1/3 and 2) the osmotic pressure profile ΠPCL(z).

The contribution of tethered mucins to the PCL osmotic pressure as a function of depth within the PCL can also be calculated by substituting the relationship between PCL correlation length and osmotic pressure into the PCL correlation length profile z = 7 µm [1 − exp(−ξ/17.5 nm)], presented in FIGURE 3Aiii, as

| (6) |

The estimates of the tethered mucin contribution to the PCL osmotic pressure as a function of PCL heights (z) calculated from Eq. 6 are depicted in FIGURE 4E (red line). Note that the osmotic pressure-PCL height values predicted from Eq. 6 are lower than those measured by dextran polymer PCL compression (black line in FIGURE 4E). This discrepancy likely reflects the elastic resistance of bending cilia that in addition to the grafted mucin gel contributes to PCL osmotic pressure (see above).

The PCL osmotic pressure values yielded by direct PCL compression measurements (black points and line in FIGURE 4E) and through ΠPCL estimates based on dextran permeation experiments (red line in FIGURE 4E) were initially thought to be surprisingly high compared with the measured osmotic pressure of a healthy mucus layer (ΠML ≈ 50–100 Pa). However, the higher PCL osmotic pressure ensures that the PCL remains well hydrated, which may be important for both mucus-PCL lubrication and liquid propulsion activities (see below). Another feature of tethered mucin brushes on each cilium important for mucus transport is that brushes exhibit excellent lubricant activities and reduce intercilial friction during ciliary beating (135).

Note that the osmotic pressure measurements of the airway surface have been analyzed in terms of the PCL, i.e., the tethered mucins covering ciliated cell surfaces/shafts. Although secretory cells facing the airway surface also exhibit tethered mucin layers (see sect. 2.3.2 and FIGURE 3B), neither the mean osmotic pressure nor osmotic pressure profiles of the secretory cell glycocalyx have been measured. Given the different geometries, i.e., cylindrical in ciliated cells and planar in secretory cells, and possible differences in densities of tethered mucin expression, there are likely to be differences in the osmotic pressures/profiles of the cell surface mucins/glycocalyx between these two cell types. Accordingly, the overall osmotic properties of airway surfaces may vary as densities of cell types change, e.g., in areas with reduced ciliated cell numbers as may be seen in COPD (see sect. 10). Knowledge of the relative cell surface osmotic pressures of different cell types may be useful in the future to predict changes in mucus transport rates and the likelihood of initial mucus accumulation in airway regions characterized by different cell populations.

2.4.5. Osmotic modulus of a mucus gel.

The osmotic modulus (K) of mucus is a useful parameter to define the water-drawing power of a gel. The osmotic modulus of the mucus layer or PCL gels is defined as the rate of change of osmotic pressure with the logarithm of concentration . As evident from this mathematical relationship, the units of osmotic pressure and modulus are the same, i.e., pascals (Pa). In conditions above c*, where mucus layer osmotic pressures increase as a power law of mucus concentration, i.e., , the mucus layer osmotic modulus (KML) can be estimated as

| (7) |

Thus, the osmotic modulus of the mucus layer in semidilute (>c*) mucin concentration conditions is ∼2.7-fold higher than the osmotic pressure. The osmotic moduli of the mucus layer and PCL are particularly useful parameters to describe relationships between airway epithelial ion transport, the relative hydration of the mucus versus PCL layers, and mucus transport rates (see below).

3. EPITHELIAL ION TRANSPORTAND AIRWAY SURFACE HYDRATION

The hydration status of airway mucus is controlled by the active ion transport and water permeability properties of airway epithelia. Airway epithelia regulate the mass of salt on airway surfaces and, because of their high epithelial water permeability, the volume of isotonic liquid/unit area, i.e., liquid height, on airway surfaces. As with the mucus clearance system, pulmonary epithelial ion/fluid transport can be viewed at multiple scales. Again, we start with the larger and proceed to smaller length scales.

3.1. Integrated Ion/Fluid Transport across Pulmonary Surfaces of the Lung

Like the macroscopic organization of the mucus layer, there are surprising gaps in our understanding of the macroscopic organization within the lung of ion and fluid transport. Indeed, little is known qualitatively or quantitatively about sites or magnitudes of integrated fluid transport throughout the respiratory tract. For example, it is not clear whether fluid is secreted by the alveolus, whether fluid if secreted is absorbed at other alveolar sites, i.e., there is an entero-alveolar cycle (136–141), or whether alveoli secrete fluid that moves onto small airway surfaces as suggested by Lindert et al. (142) and Bove et al. (143). Furthermore, little is known about the physical forces that may mediate fluid flow from the alveolus to the small airways if fluid flow indeed occurs. A clinical phenotype of primary cilia dyskinesia (PCD) subjects, i.e., failure to normally clear alveoli of fluid at birth, suggests a role for cilia in alveolar-small airway fluid coupling (144). In addition, Marangoni forces generated by surfactant gradients from regions of high surfactant concentration, i.e., alveolar surfaces, to regions of lower concentrations, i.e., distal airways, may also mediate bulk liquid flows (145, 146). The great disparity between alveolar (100 m2) and distal small airway (1–2 m2) surfaces suggests that tight regulation of coupled regional liquid flow by whatever mechanism(s) is required.

Similarly, Kilburn pointed out 50 years ago the implications for the great disparity between distal airway (1–2 m2) and proximal airway (50 cm2 at 3rd-generation airways) surfaces for mucus transport (27, 147). He suggested that progressive absorption of the liquid moving up airway surfaces was required to avoid fluid occlusion of proximal airway lumens, i.e., proximal airway “drowning” (147). Recent ion/fluid transport studies of cultured human distal small (bronchiolar) and proximal large (bronchial) airway epithelia suggest that the small and large airways exhibit similar transepithelial ion/fluid transport rates per unit surface area, reflecting similar levels of ENaC and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) expression (133, 148–150). Based on surface area considerations, these data suggest that small airways have greater aggregate ion/fluid transport activities than large airways. To avoid proximal “drowning,” either 1) mucins, not water, must selectively be transported proximally or 2) airway epithelia must exhibit mechanisms to regulate intraregional fluid balance while adequately hydrating mucus for optimal transport. Part of the answer to this problem will require, as discussed above, resolution of the nature of the mucin layer versus flake controversy. However, airway epithelia appear to exhibit multiple mechanisms to continually establish proper local ASL volume/mucus hydration as mucus sweeps cephalad along converging surfaces, as postulated by Kilburn (147).

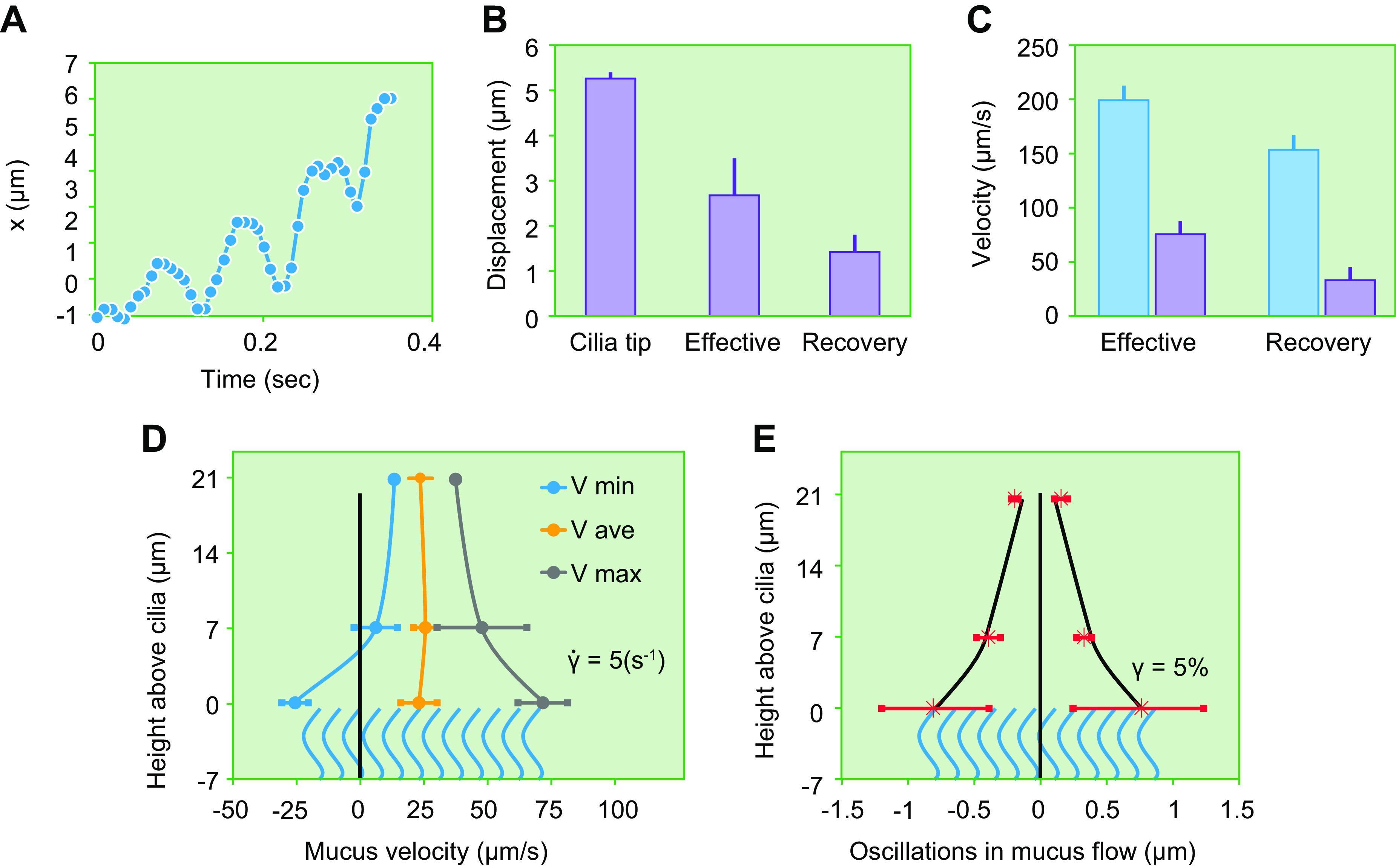

3.2. Regulation of Airway Transepithelial Ion/Fluid Transport

More is known about the microscopic regulation of airway epithelial surface hydration by active ion transport in health and disease. In health, airway epithelia can secrete or absorb ions and indeed likely do both simultaneously to finely tune airway surface volume (hydration) (151) (FIGURE 5A). Note that it is the ASL volume, as microliters per unit surface area (e.g., cm2), that is controlled by active ion transport. The quotient of this relationship, i.e., height, is typically measured by confocal microscopy to assess the volume status of airway surfaces. The typical 7-µm ASL height measured under basal, static conditions (see below) may reflect the biologic adaptation of airway epithelia to produce sufficient volume on airway surfaces to allow cilia to fully extend and efficiently propel mucus.

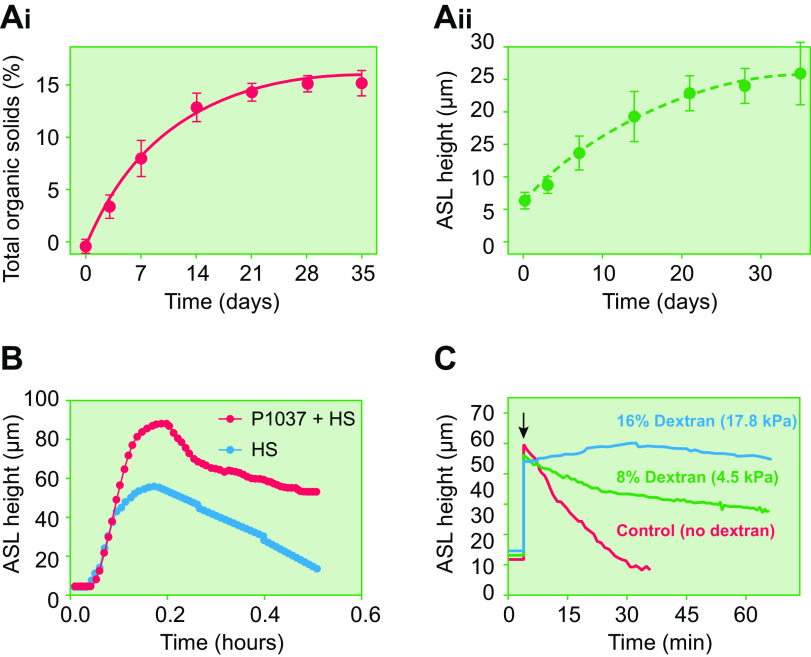

FIGURE 5.

Airway epithelial ion transport regulation of airway surface liquid volume/surface area (height). A: diagram of the mucus layer and periciliary-glycocalyx layer in context of epithelial active ion transport pathways. The mucus layer is depicted with 1.5% organic solids concentration. Osmotic moduli (K) of the mucus layer (KML) and PCL (KPCL) in pascals (Pa) are noted. An epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) on the apical airway epithelial membrane mediates Na+/liquid absorption. In parallel, the epithelium can secrete Cl−/anions (and liquid) to the lumen via the CFTR channel and a calcium-activated channel (CaCC) (93). The balance between active Na+ absorption and Cl− secretion is regulated in part by the concentrations of extracellular ATP, interacting with P2Y2 receptors (P2Y2Rs), and adenosine (ADO), interacting with A2B receptors. P2Y2R activation inhibits Na+ absorption and stimulates CFTR/CaCC-mediated Cl− secretion, producing/accelerating liquid secretion (152, 153). A2B activation accelerates CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion, also producing liquid secretion. B: expression of ion channels in human airway epithelial cells. Bi: the “classic”/previous paradigm depicted CFTR, ENaC, and related basolateral ion channels (not shown) as expressed in ciliated cells. Bii: a new paradigm has CFTR, ENaC, and related basolateral ion channels/transporters (not shown) mediating transepithelial ion flows expressed in CCSP+, mucin-expressing secretory cells in both large and small airways (133). The possibility that still some CFTR is expressed in ciliated cells is shown (133). A rare cell type, the ionocyte (yellow), is depicted in large airways that expresses high levels of ENaC and CFTR. See glossary for other abbreviations.

Previous models had assigned the major ion transport channels, i.e., the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) and CFTR, to ciliated cells (154) (FIGURE 5Bi). However, initial scRNAseq data of proximal mouse and human airways led to revision of this notion (155). These scRNAseq data from mice and humans identified a previously uncharacterized, unique cell type that expressed high levels of CFTR and V-type ATPases (as well as ENaC) (FIGURE 5Bii). This cell type bears functional and molecular similarities to mitochondrion-rich cells in amphibian skins and was termed an “ionocyte” (156, 157). The ionocyte appears more prevalent in proximal human airways and especially in the ductal regions of submucosal glands (155, 158–160). The precise functions of ionocytes in superficial airway epithelial function are not yet known, but they may play a role in producing a mildly hypotonic SMG secretion (see sect. 10).

The most recent single-cell RNAseq data describing the entire human respiratory tract, coupled to functional data, suggest that the CC10+ club cell expresses in addition to CC10 and MUC5B the major airway ion channels required for transepithelial fluid transport (133, 161–163) (FIGURE 5Bii). The club cell-mediated active Na+ absorption pathway includes the apical membrane epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC), which is typically rate limiting for Na+/fluid absorption, and the basolateral membrane Na+-K+-ATPase (93, 164). In parallel, the club cell has the capacity to secrete Cl−/anions to the lumen via apical membrane CFTR, a calcium-activated channel (CaCC), likely TMEM16a, and possibly SLC26A9 channels supported by a basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (SLC12A2) (165–169). Apical and basolateral club cell K+ channels modulate the driving forces that determine the absolute rates of Na+ absorption and Cl− secretion as well as mediating transepithelial K+ secretion (170–172). ASL K+ may be recycled by an apical membrane H+-K+-ATPase that, in parallel with secretion by apical Cl− channels, including CFTR, and the paracellular permeability to and H+, regulates ASL pH (173–175). Quantitative biophysically based mathematical models of airway epithelial ion transport are available (164, 176–181).

The magnitudes of the active Na+ absorption and Cl− secretion rates are regulated by the number (N) of ion channels per epithelial cell apical membrane surface area and their activation state (open probability, Po). Channel activation states are regulated by intracellular processing, cell surface processing, and/or the concentrations of regulatory molecules in the ASL. More is known about the acute regulation of Po than chronic regulation of channel number (N), and, consequently, these acute regulatory activities are emphasized here.

Apical membrane ENaC Na+ conductance (NPo) is rate limiting for transepithelial Na+ absorption across pulmonary epithelia. ENaC is activated by proteolytic cleavage events, in part mediated intracellularly (furin) and in part at the apical membrane, e.g., PRSS8 (prostasin) (90, 153, 182–184). PRSS8 activity, and hence ENaC activity, is regulated by the concentration of poorly defined protease inhibitors in ASL (185). Proteolytic regulation of ENaC activity governs both the rate of Na+ absorption and the electrochemical driving force for Cl− secretion (93, 186–189). Superimposed on proteolytic regulation of ENaC are acute regulatory events mediated by G protein-coupled receptors. Perhaps most widely studied is the inhibition of ENaC activity produced by P2Y2R purinoceptor-mediated cleavage of apical membrane phosphatidylinositol bisphosphates (PIP2) (190–195).

Counterbalancing Na+ absorption are the number (N) and activity (Po) of apical membrane Cl− (anion) channels that, with favorable electrochemical driving forces, can convert the epithelium from net fluid absorptive to secretory. Regulation of CFTR channel number in airways is poorly understood, whereas there is abundant evidence that TMEM16a is strongly regulated by type 2 immune signaling (169, 196–200). The activation state of apical membrane Cl− channels is regulated by apical and basolateral membrane G protein-coupled receptors. The Gq class of receptors, e.g., nucleotide (e.g., ATP), histamine, bradykinin, and PAR receptors, activate CFTR via regulation of Ca2+-dependent adenylate cyclases and cAMP formation and TMEM16a by increases in intracellular Ca2+ and protein kinase C (201, 202). Stimulation of Gs-coupled receptors, e.g., β2 receptors, adenosine receptors, and VIP receptors, activates adenylate cyclase directly and raises cell cAMP (203–205). Cell cAMP levels regulate CFTR activity via PKA-dependent phosphorylation of the R domain (206, 207).

3.3. Coordinate Regulation of Ion Transport/Fluid Transport Mechanisms for Maintenance of Optimal Mucus Layer Concentration/Hydration: Superficial Epithelium

Coordinate regulation of Na+ absorptive and Cl− secretory pathways to maintain the proper hydration state of mucus, i.e., 97.5% water, 1% ions, and 1.5% organic molecules, is required to respond to the spectrum of conditions that confront the lung. In the distal airways, these functions are exclusive properties of the superficial epithelia. In the proximal airways, submucosal glands (SMGs) also contribute to these activities (see below). It must be stressed that net fluid transport across airway epithelia reflects the balance between simultaneous Na+-driven absorption versus Cl−-driven secretion (93). Insufficient hydration of airway surfaces thus can reflect an absolute increase of Na+ absorption superimposed on normal Cl− secretion rates (208), a normal rate of Na+ absorption superimposed on defective/absent Cl− secretion (209), or scenarios in between. Similarly, excessive fluid secretion can reflect a decrease in Na+ absorption, as observed in pseudohypoaldosteronism (210), or accelerated Cl− secretion, in response to cytokines and/or ATP released during inflammation (201, 211, 212). The pathways that regulate the balance between airway surface dehydration and flooding are therefore important to identify and quantitate for a comprehensive description of mucus hydration in health and disease.

It is important to note that there are multiple overlapping functional requirements of ASL volume homeostasis. First, there is a basal secretion of the liquid required to hydrate airway surfaces to provide water for conditioning inspired air. Second, there are the regulated components of ASL volume transport required to adjust ASL volumes intraregionally as mucus is transported cephalad up converging surface areas. Third, there is a need to adjust the liquid content of mucus locally at the cell level to maintain efficient local mucus transport. Because the extracellular purine nucleotide (NT, e.g., ATP) and purine nucleoside (NS, e.g., adenosine) pathways are the most extensively studied with reference to responses to different physiological conditions, their role in maintenance of ASL volume is emphasized in this section (FIGURE 6A). Note that this topic has also been quantitatively addressed in mathematical models describing 1) extracellular nucleotide/nucleoside release and metabolism and 2) relationships between extracellular nucleotide/nucleoside concentration, ion transport patterns/rates, and the net fluid transport required for ASL homeostasis in both health and disease (213–215).

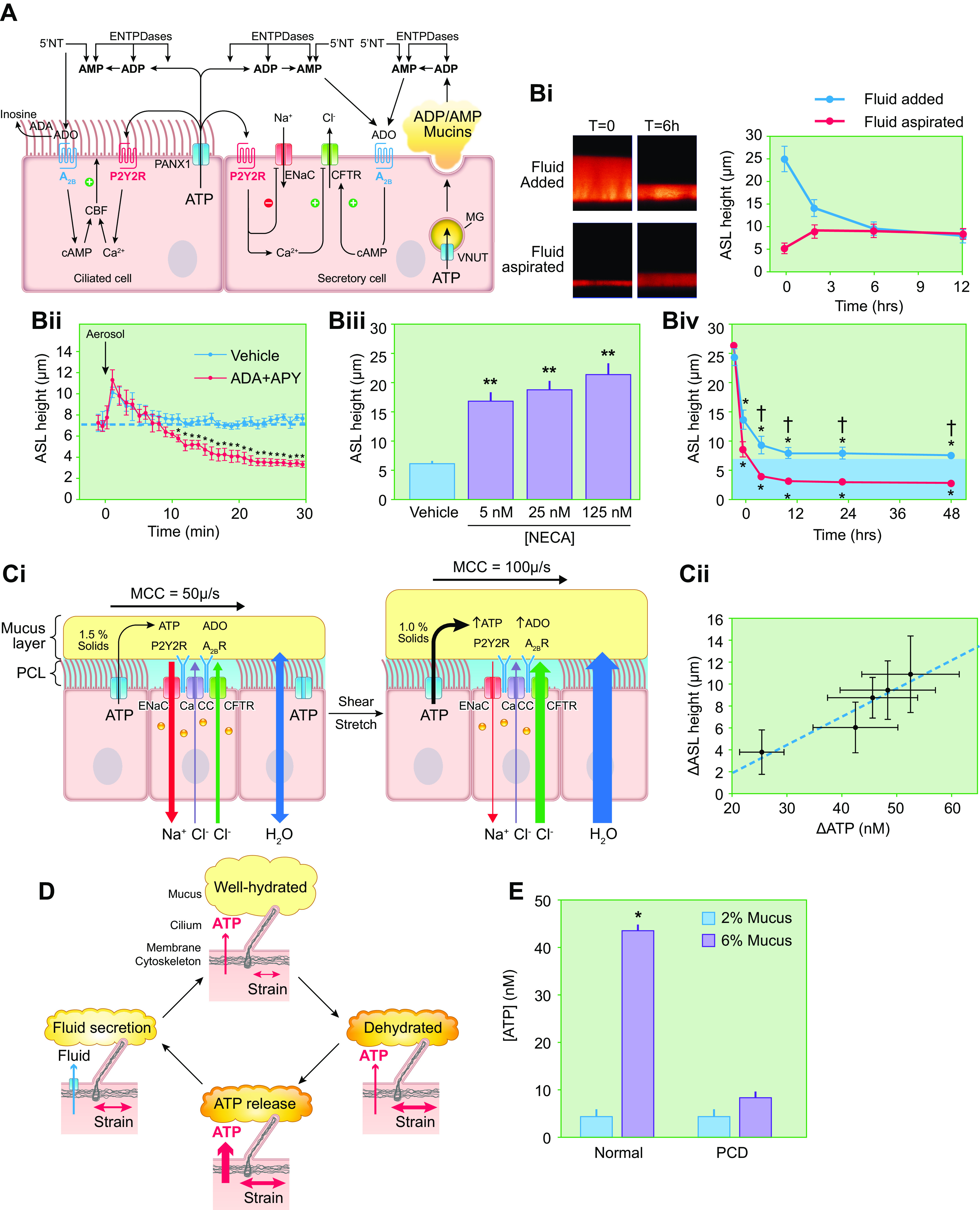

FIGURE 6.

Airway surface liquid volume regulation. A: diagram of purinergic signaling pathways that coordinately control directions/rates of transepithelial ion and fluid transport and ciliary beat frequency (CBF) by the two major lumen-facing epithelial cell types, i.e., ciliated and secretory cells. The pannexin 1 (PANX1) ATP-releasing apical membrane hemichannel, cell surface/shed extracellular enzymes that metabolize ATP, ADP, AMP, and adenosine (ADO) (ENTPDases, 5′-NT), apical purinoceptors (nucleotide, P2Y2R; nucleoside, A2B), and regulated CFTR, ENaC, and Ca2+-activated (CaCC) ion channels shown. Purinoceptors and ecto-enzyme nucleotide/nucleoside metabolic enzymes are depicted as commonly expressed in both ciliated and secretory cells. Pannexin-1 (PANX-1)-mediated ATP release from ciliated cells consequent to cilia-mucus sensing (see FIGURE 6D) regulates cilial beat frequency in an autocrine fashion and regulates ion transport in secretory cells in a paracrine fashion. The extracellular metabolite of ATP, i.e., adenosine, also regulates CBF and ion transport in autocrine and paracrine fashions, respectively. In secretory cells, ATP is imported into mucus granules (MG) via the vesicular nucleotide transporter (VNUT) and metabolized to ADP and AMP. These nucleotides are co-released with mucins and, via metabolism to adenosine, trigger autocrine ion/fluid secretion to hydrate the newly secreted mucins. Note, although not depicted for simplicity, P2Y2R is expressed on secretory cells and when activated triggers mucin secretion. The absence of co-release of ATP with secreted mucins protects from excessive, autocrine-mediated ATP mucin secretion. Also not depicted for simplicity, ADP/AMP release from secretory cells likely also provides adenosine for regulation of ciliary beat frequency in adjacent ciliated cells. Thus nucleotide release exhibits critical autocrine and paracrine signaling properties for coordination of efficient mucus transport. B: control of airway surface liquid volume/surface area (height) by purinergic signaling as imaged by X-Z confocal microscopy. Bi: addition of fluorescent dextran-containing solution to cultured human airway surface without (top) or with (bottom) subsequent aspiration at time (t) 0 is followed by autoregulation over 4–6 h to a common height that is governed by rates of ATP release and conversion to ADO (courtesy of Dr. Robert Tarran, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill). N = 8. Bii: basal ATP release and conversion to ADO governs Na+ vs. Cl− transport rates to generate basal ASL heights of ∼7 µm. Addition of enzymes to metabolize extracellular ATP (apyrase, APY) and adenosine (adenosine deaminase, ADA) abolishes the ability of the human bronchial epithelial (HBE) culture to maintain a 7-µm ASL height (blue dashed line). The default Na+ absorptive pathway removes all available ASL (216). Biii: dependence of ASL on concentration of added nonmetabolizable adenosine analog 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA). Higher NECA concentrations stimulate higher fluid secretion rates and higher steady-state ASL height (216). Biv: CF vs. normal ASL homeostasis under static conditions. In contrast to normal cultures, CF cultures cannot maintain adequate airway surface volumes (height) under static conditions. Levels of ASL adenosine and A2B expression are similar in CF and normal HBE cultures (152). The failure of the mutant CFTR to secrete Cl−/fluid and moderate ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption drives ASL depletion in CF. C: control of airway surface hydration during tidal breathing. Ci: under static conditions, ATP release rates are fixed at ∼400 fmol/cm2/min and generate an ∼7-µm-deep ASL layer height. The mechanical shear and transmural stretch imparted onto airway epithelia during normal breathing increase ATP release rates via PANX-1 hemichannels. As a result, ASL ATP levels increase, which inhibits Na+ absorption, increases (via metabolism-generated ADO) Cl−/fluid secretion, and increases ASL volume/height. Fluid secretion dilutes mucus concentrations (depicted as % organic solids). Cii: relationship between the magnitude of changes in luminal ATP concentrations and ASL height. Human airway cultures were subjected to varying degrees of oscillatory stress during measurements of luminal [ATP] and steady-state ASL heights. These data revealed a direct relationship between [ATP] and changes in ASL height (correlation coefficient = 0.95 and slope = 0.3 mm height per steady-state change in ATP concentration) (216). D: airway epithelial autoregulation of proper surface hydration states, i.e., 97.5% water, 1.5% organic solids, 1% salt mucus, is mediated by mechanotransduction sensing by motile cilia. Motile cilia interact with mucus layer and transfer momentum to the layer. The yield stress of the mucus layer in response to ciliary beat is a function of mucus concentration. If mucus becomes hyperconcentrated/dehydrated, mucus layer yield stress increases (right). The decreased deformability (higher yield stress) of the mucus layer increases the strain on the ciliary shaft during ciliary beating, which promotes PANX-1-mediated increases in ATP release (bottom). Increased ATP release increases local ATP concentrations, increases fluid secretion (left), and rehydrates mucus to favorable homeostatic states in an autoregulatory feedback loop (top) (216). E: requirement for motile cilia in autoregulation of mucus hydration. Cilia from normal subjects respond to hyperconcentrated (6%) mucus with an increase in ATP release and a higher steady-state concentration of ATP within ASL. Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) cultures, with absent cilial motility, fail to sense mucus hyperconcentration and accelerate ATP release/increase ATP concentrations within ASL. See glossary for other abbreviations. Content from Ref. 216 used with permission from Science Signaling.

3.3.1. Static in vitro conditions.

The control of ASL volume under static in vitro cell culture conditions has received much attention because of the simplicity of this condition for experimental manipulation (FIGURE 6, A and B). Functionally, this state may relate in vivo to an absence of ventilation of airways due to physical obstruction. Studies of static cultures revealed that airway epithelia, in the absence of ASL regulatory signals, exhibit Na+/fluid absorption as the default mode (152, 153). Experiments in which ion transport regulatory molecules in ASL were diluted by PBS boluses, or blocked by pharmacological agents, provided evidence for Na+ absorption as the default pathway (90, 152, 153) (FIGURE 6, Bi and Bii). In these experiments, ASL depletion by unregulated Na+ absorption occurred within 10–15 min of initiation of pharmacological block maneuvers, reflecting a basal ASL volume of ∼1 µL/cm2 (corresponding to 10 µm height) juxtaposed to active absorption rates in the unrestrained/default mode of ∼5 µL/cm2/h (or 0.8 µm/min) (93) (FIGURE 6Bii). It is possible that this default absorptive property is designed to keep airway/lumens patent for airflow when airway lumens are flooded in vivo and regulatory molecules diluted, e.g., during drowning episodes. However, unrestricted volume absorption under normal conditions would inappropriately dehydrate airway surfaces. Thus, a regulatory system is required to provide a brake on Na+/fluid absorption and stimulate sufficient Cl− (fluid) secretion to generate ASL fluid volumes suitable for steady-state mucus transport (see below; Ref. 152).

It is likely that apical membrane purinoceptors, activated by ATP [P2Y2 receptors (P2Y2Rs)] and adenosine (A2B), dominate this regulatory role (217) (FIGURE 6A). As required for ion transport synchronization, nucleotide/nucleoside receptors not only exhibit the capacity to inhibit ENaC but also activate Cl− channels/secretion (194, 210, 212). The concentrations of purinoceptor ligands, i.e., ATP and adenosine (ADO), are tightly controlled by complex NT release, extracellular metabolism, and nucleoside reuptake systems (214, 215, 217, 218). ATP is released from airway epithelia onto airway surfaces via pannexin-I hemichannels, vesicular pathways, e.g., the vesicular nucleotide uptake transporter (SLC17A9), and perhaps other pathways at a basal rate of ∼400 fmol/cm2/min under static conditions (17, 219–226) (FIGURE 6A). ATP released at this rate is rapidly metabolized by a complex of cell surface and secreted ecto-ATPases to produce basal ATP levels of ∼2 nM, too low to activate P2Y2Rs (152, 212, 215). However, ecto-metabolism of ATP generates ADO concentrations of ∼200 nM, sufficient to activate A2B receptors. Note that little if any ADO is directly released from airway epithelia, almost all being formed extracellularly via metabolism of ATP. Finally, nucleoside transport systems return ADO and its adenosine deaminase (ADA) metabolites, inosine and hypoxanthine, back into epithelial cells (227).

Importantly, there are also brakes on the nucleotide-regulated Cl− secretory system to prevent excessive Cl−/fluid secretion that may flood airway lumens. One brake is desensitization of the P2Y2R in response to the high ATP levels on pulmonary surfaces that may occur during periods of high mechanical forces (e.g., high pressure ventilation) or cell death (228–232).

Confocal microscopy measurements have established the ASL volume homeostatic roles of nucleotide signaling. Normal human airway culture surfaces are not volume depleted, i.e., are not dry, under basal static conditions (182, 183, 233, 234) (FIGURE 6B). They typically exhibit ∼7- to 10-µm-deep ASL layers, i.e., a volume per unit area of ∼1 µL/cm2. Remarkably, ASL height/volume will return to a physiological 7- to 10-µm height (1 µL/cm2 volume per unit area) after either bolus PBS addition or physical removal of ASL fluid, a steady-state volume governed by the adenosine concentrations produced by epithelial ATP release and ecto-enzyme conversion of ATP to adenosine (FIGURE 6Bi). The role of adenosine in static ASL volume homeostatic responses was revealed by the 1) reduction of steady-state ASL volumes in response to accelerated biochemical metabolism of ADO by exogenously added apyrase/adenosine deaminase (FIGURE 6Bii) or administration of pharmacological A2B receptor blockers (152) and 2) dose-effect relationships between ASL concentrations of an adenosine agonist [the metabolically inert adenosine analog 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA)] and ASL height (152) (FIGURE 6Biii).

In contrast, study of CF airway cultures under static conditions revealed volume depletion (<3-µm layer thickness corresponding to 0.3 µL/cm2) of airway surfaces (FIGURE 6Biv). Extracellular adenosine concentrations or A2B receptor coupling to adenylate cycle were not different in CF versus normal cultures (152). Accordingly, these observations defined the role of functional CFTR as a downstream effector for ADO-regulated ASL volume homeostasis. The static CF culture system provided an important screening platform for the search for CFTR modulators (153, 233, 235, 236).

3.3.2. Phasic motion.

In vivo, the lung phasically exerts 1) stretch on airway walls/epithelia as airways dilate and constrict during breathing and 2) shear on airway surfaces due to phasic airflow (FIGURE 6Ci). Superimposed on basal ATP release rates, a variable ATP release component, governed in part by breathing-associated mechanical forces on airway surfaces, increases ATP release rates to generate the increased extracellular ATP and ADO concentration levels required for optimal mucus hydration during respiration. For example, under conditions that mimic tidal breathing, airway epithelial ATP release rates rise to levels that produce ATP concentrations of ∼30 nM and ∼300 nM ADO in ASL (234, 237). The increased levels of ATP/ADO promote an approximate doubling of ASL volume (and height), providing airway surfaces with a reserve of fluid to react to the diverse environmental conditions encountered during tidal ventilation (FIGURE 6Cii). A further increase in airflow-induced ATP release during exercise likely maintains airway surface hydration during periods of high pulmonary ventilation with increased micro-aerosol and increased evaporative water loss (238) (FIGURE 6Cii).

3.3.3. Local control of ASL hydration at the single-cell level.