Abstract

Cryptosporidium parvum is an obligate intracellular pathogen responsible for widespread infections in humans and animals. The inability to obtain purified samples of this organism’s various developmental stages has limited the understanding of the biochemical mechanisms important for C. parvum development or host-parasite interaction. To identify C. parvum genes independent of their developmental expression, a random sequence analysis of the 10.4-megabase genome of C. parvum was undertaken. Total genomic DNA was sheared by nebulization, and fragments between 800 and 1,500 bp were gel purified and cloned into a plasmid vector. A total of 442 clones were randomly selected and subjected to automated sequencing by using one or two primers flanking the cloning site. In this way, 654 genomic survey sequences (GSSs) were generated, corresponding to >320 kb of genomic sequence. These sequences were assembled into 408 contigs containing >250 kb of unique sequence, representing ∼2.5% of the C. parvum genome. Comparison of the GSSs with sequences in the public DNA and protein databases revealed that 107 contigs (26%) displayed similarity to previously identified proteins and rRNA and tRNA genes. These included putative genes involved in the glycolytic pathway, DNA, RNA, and protein metabolism, and signal transduction pathways. The repetitive sequence elements identified included a telomere-like sequence containing hexamer repeats, 57 microsatellite-like elements composed of dinucleotide or trinucleotide repeats, and a direct repeat sequence. This study demonstrates that large-scale genomic sequencing is an efficient approach to analyze the organizational characteristics and information content of the C. parvum genome.

Cryptosporidium parvum has emerged as a well-recognized cause of acute gastrointestinal disease in humans and animals throughout the world and is associated with a substantial degree of morbidity in patients with AIDS (15). C. parvum belongs to the phylum Apicomplexa and is one of several genera that are referred to as coccidia. The parasite primarily infects the microvillous border of the intestinal epithelium and to a lesser extent the extraintestinal epithelium (10). The life cycle of C. parvum resembles that of other coccidia and includes multiple asexual and sexual developmental stages.

Despite the medical and veterinary importance of C. parvum, studies of this organism at the genetic level have only begun in recent years and are still in their infancy. Although a relatively small number of basic metabolic and structural genes as well as several genes encoding immunogenic antigens have been identified (10), little is known about the basic cellular and molecular biology of this pathogen in terms of virulence factors, genome structure, or developmental biology. This is largely due to the inability to obtain purified samples of the various developmental stages of the parasite for biochemical studies. The relatively small size and simple organization of the 10.4-megabase (Mb) C. parvum genome, which is composed of eight chromosomes ranging from 1.04 to 1.5 Mb, however, balance these disadvantages (3). Since the genomic DNA sequence encodes all of the heritable information responsible for parasite development, disease pathogenesis, virulence, species permissiveness, and immune resistance, a comprehensive knowledge of the C. parvum genome will provide the necessary information required for targeted research into disease prevention and treatment.

Over the past few years, large-scale sequencing of randomly selected cDNA or fragments of genomic DNA has proven to be an efficient approach for expanding the understanding of the biology of an organism, including many pathogenic protozoa (6, 8, 21, 32, 36). Recently, a large-scale expressed sequence tag (EST) sequencing project was undertaken for C. parvum sporozoites (5). Due to the inability to obtain purified samples of other developmental stages, in particular, the intracellular stages, the ongoing C. parvum EST approach is limited to the discovery of genes that are expressed in sporozoites. Considering the absolute dependence of C. parvum development on the mammalian host cell, many unique biochemical pathways and molecular mechanisms involved in host-parasite interaction and pathogenesis are not likely to be identified by the ongoing sporozoite EST project.

In order to identify C. parvum genes, independent of their developmental expression, we conducted large-scale sequencing of random C. parvum genomic segments. In this report, we described the identification of 654 genomic survey sequences (GSSs) obtained by the random sequencing of clones from a small-insert C. parvum total genomic DNA library. The relatively high number of GSSs with similarity to previously characterized genes from other organisms implies that genomic sequencing is an efficient method for gene discovery in C. parvum. Furthermore, the identification of putative C. parvum genes and repetitive elements laid the foundation for studies directed toward understanding the biology of C. parvum and the development of strategies for subspecies differentiation and epidemiological surveillance of the parasite.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA preparation.

C. parvum oocysts (Iowa isolate; originally obtained from C. Sterling, University of Arizona, Tucson) were sterilized by incubation in Clorox (3 × 107 oocysts/ml; sodium hypochlorite, 5.25%; dilution rate, 1:3) for 7 min on ice. The oocysts were washed five times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by centrifugation at 3,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The oocysts were resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 108 oocysts/ml. An equal volume of 2× excystation medium (0.05 g of trypsin and 0.15 g of sodium taurocholate in 5 ml of Hanks’ buffered salt solution [pH 7.2 to 7.4]) was added, and the oocysts were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The unexcysted oocysts and sporozoites were washed three times in PBS by centrifugation. The pelleted oocysts and sporozoites were suspended in 400 μl of DNA lysis solution (120 mM NaCl, 0.1 M EDTA, 25 mM Tris base, 1% Sarkosyl), and the suspension was subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles with liquid nitrogen and a 70°C water bath. The lysate was incubated with protease K (1 mg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation by using standard methods (29). The DNA precipitate was resuspended in 0.5 ml of TE (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) and treated with RNase A (1 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. The DNA sample was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated, and resuspended in TE as described above.

Library construction.

Total genomic DNA (100 μg) was randomly sheared by using a gas-driven nebulizer as previously described (28), blunted with Escherichia coli DNA polymerase, and phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase. The DNA fragments were fractionated by electrophoresis, and fragments between 800 to 1,500 bp were excised from the agarose gel and purified with QIAEX II kits (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). The purified DNA fragments were cloned into the SmaI site of pBluescript II SK (+) vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.).

Sequencing and analysis.

Randomly selected clones from the unamplified library were grown overnight, and plasmid DNA was purified with SNAP kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) or Qiagen plasmid minikits (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed at the Advanced Genetics Analysis Center (College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota) by using dye termination cycle sequencing technology with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) and was analyzed on an ABI fluorescence automated sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Sequence data were edited with EditSeq (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.), to remove the vector sequence and/or to delete sequences of low reliability. Contig assembly and statistical analysis were performed by using SeqMan (DNASTAR). Public databases, including GenBank (release 105.0), EMBL (release 53.0), PIR (release 55.0), SWISS-PROT (release 35.0), PROSITE (release 14.0), and Profile Library, were searched for similarity to known sequences or motifs by using NETBLAST, MOTIFS, and PROFILESCAN (GCG Wisconsin Package, version 9.1; Genetics Computer Group [GCG], Madison, Wis.). Previously identified C. parvum sequences in GenBank were searched and retrieved with STRINGSEARCH and FETCH (GCG). The sequences were further compiled into a local database by using GCGTOBLAST (GCG) and were searched for similarities to our C. parvum GSSs by using BLAST (GCG). The mono-, di-, and trinucleotide compositions were calculated with COMPOSITION (GCG). Direct repeats and simple sequence repeats were identified with FINDPATTERNS (GCG).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Nucleotide sequences reported in this paper are available in the GenBank database under accession no. AQ023473 to AQ024123.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characteristics of sequencing data.

To generate a uniformly distributed, representative sequencing template library, high-molecular-weight C. parvum genomic DNA was mechanically sheared by nebulization as previously described (28). The sheared DNA was separated by gel electrophoresis, and fragments with a size distribution from 800 to 1,500 bp were purified and used to construct the genomic library in the vector pBluescript II SK (+). Automated DNA sequencing was performed on a total of 432 random clones. Among them, 212 clones were sequenced with primers flanking each side of the cloning site (T3 and T7 primers). The remaining 230 clones were sequenced with only one flanking primer (T3). A total of 324,076 bp of genomic sequence was generated. In order to identify overlapping sequences, all sequences were subjected to contig assembly. This analysis generated 408 contigs containing 256,935 bp of unique genomic sequence. This represented ∼2.5% of the estimated 10.4-Mb C. parvum genome. The majority of nonunique sequence was the result of overlapping sequences generated from individual clones with both flanking primers. A total of 94% (408 individual contigs generated from 432 random clones) of the random clones contained unique sequences. To assess the quality of our sequence data, GSSs matching previous C. parvum database entries were aligned with their corresponding database entries. The accuracy of our sequences, indicated by the percentage of the identical nucleotides between the aligned sequences, was found to be greater than 99% (data not shown). Other than vector sequences used to construct the genomic library, no contaminating bacterial or bovine sequences were found among the generated GSSs. This is likely due to the harsh chemical treatments and extensive washing of the oocysts prior to DNA isolation, which greatly reduced the chance of contamination of the C. parvum genomic DNA library with host or other microbial DNA fragments.

Identification of putative genes.

Database searching with the GSSs was performed by using the program NETBLAST against the nonredundant GenBank, PDB, SWISS-PROT, and PIR (1) databases. This analysis revealed that 134 GSSs, corresponding to 107 individual contigs (26%), displayed significant similarity (smallest probability [P ≤ 10−5]) to sequences present in the databases. Among them, 129 GSSs displayed similarity to known protein sequences, one displayed a significant similarity to telomeric sequences of several eukaryotes (CpGR254), and two (CpGR12A and CpGR12B) contained sequences representing C. parvum rRNA genes (GenBank accession no. AF040725). Seven of the GSSs represented previously characterized C. parvum sequences (precursor of oocyst wall [GenBank Z22537], tubulin beta chain [PIR A25342], C. parvum DNA segment B [GenBank M59420], C. parvum open reading frame [ORF] 2 gene [GenBank U18112], thrombospondin-related adhesive protein (TRAP) [GenBank AF017267], elongation factor [GenBank U71180], and protein disulfide isomerase [GenBank U48261]). In addition, searching the GSSs with the program tRNAscan-SE (20) identified one GSS (CpGR309B), which was highly homologous to the isoleucine tRNA gene of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans (GenBank U18089).

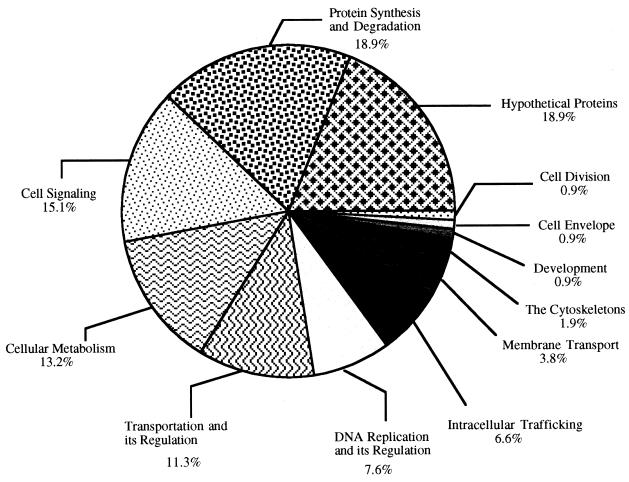

The GSSs which displayed significant similarities to database entries were grouped based on the biological roles of their matches (Table 1) by using the classification system developed by Riley (27). The distribution of putative genes in different functional groups is shown in Fig. 1. It is evident that genes involved in macromolecular and small-molecular biosynthesis are well represented in the C. parvum genome, as well as genes potentially involved in cellular signaling, energy production, and the regulation of mRNA and protein expression. Of special interest are those genes potentially involved in parasite survival, pathogenesis, and host-parasite interaction. Below, we described several groups of proteins that fall into these categories, which provide new insights into C. parvum biology.

TABLE 1.

C. parvum GSSs matched to known sequences from C. parvum and other organisms in public databasesa

| Function and clone name | Accession no. of closest hit | Description | Organism | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell division | ||||

| CpGR24B | gb/U69154 | Prohibitin | Nicotiana tabacum | 2.80e-53 |

| Cell envelope | ||||

| CpGR102A | gb/Z22537 | Precursor of oocyst wall | Cryptosporidium parvum | 2.30e-14 |

| Cellular metabolism | ||||

| Biosynthesis of cofactors | ||||

| CpGR327A | sp/P22217 | Thioredoxin II (TR-II) | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 6.30e-24 |

| Energy metabolism | ||||

| CpGR27A/B/69A/B/195 | gb/U89342 | Phosphoglucomutase | Zea mays | 3.80e-54 |

| A/B/336A | ||||

| CpGR160A | pir/S58236 | Pyruvate oxidoreductase | Entamoeba histolytica | 1.70e-31 |

| CpGR230A/B | gb/AB000703 | Phosphomannomutase | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 5.20e-11 |

| CpGR245A | gb/D84307 | Phosphor-ethanol-amine cytidylyl-transferase | Homo sapiens | 2.4e-32 |

| Fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism | ||||

| CpGR306A | gb/U85829 | Enolase gene | Spongilla sp. | 1.10e-28 |

| CpGR496A | sp/P14685 | Probable diphenol oxidase A2 components | Mus musculus | 3.9e-22 |

| CpGR452A | gb/D82928 | Phosphatidylinositol synthase | Rattus norvegicus | 1.2e-06 |

| Purines or pyrimidines | ||||

| CpGR240A | pir/S69219 | Pseudouridine synthase 2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 8.00e-23 |

| CpGR458A | gb/U15181 | Deoxyuridine 5′ triphosphate nucleotidohydrolase | Mycobacterium leprae | 2.1e-06 |

| CpGR437A | sp/P36590/ | Thymidylate kinase | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 8.8e-27 |

| Cell signaling | ||||

| Ligand | ||||

| CpGR17B | pir/A55053 | Endothelial monocyte-activating protein | Caenorhabditis elegans | 7.60e-11 |

| Receptor and their associated proteins | ||||

| CpGR7B, CpGR385A | gb/U12596 | TNF type 1 receptor associated protein | Homo sapiens | 4.10e-48 |

| CpGR24A | gb/U28940 | B-cell receptor associated protein | Homo sapiens | 3.30e-14 |

| CpGR26A/B | sp/P48643, sp/P40413 | T-complex protein 1, Epsilon subunit | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 2.30e-52 |

| CpGR159A | gb/S67127/S67127 | Endothelin ETA receptor | Homo sapiens | 8.30e-10 |

| Protein kinase and phosphatase | ||||

| CpGR21A | gb/D50927 | KIAA0137 gene product related to protein kinase | Rattus norvegicus | 9.5e-27 |

| CpGR192B | pir/S19027 | Protein kinase A catalytic chain | Aplysia californica | 2.50e-23 |

| CpGR312A | sp/P07312 | Casein kinase II, beta chain | Bos taurus | 2.10e-35 |

| CpGR425A | pir/S39559 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase | Nicotiana tabacum | 5.70e-27 |

| CpGR302A/B | pir/A55661 | Protein kinase ADK1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 1.20e-85 |

| CpGR360A | gb/U78721 | Protein phosphatase 2C | Arabidopsis thaliana | 2.30e-12 |

| CpGR494A | pir/I38215 | Protein-serine/threonine kinase | Homo sapiens | 1.1e-24 |

| Other | ||||

| CpGR231B | gb/U59684 | Shk1 kinase-binding protein | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 4.00e-10 |

| CpGR176A | sp/P35447 | F-spondin precursor | Xenopus laevis | 4.3e-06 |

| CpGR260A | sp/P35446 | F-spondin precursor | Rattus norvegicus | 5.1e-14 |

| CpGR455A | pir/I38176 | ragA | Homo sapiens | 1.6e-24 |

| CpGR352A | gb/U23449 | Diacylglycerol kinase | Caenorhabditis elegans | 1.80e-23 |

| CpGR44B | sp/P53742 | Possible GTP-binding protein | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.60e-54 |

| Development | ||||

| CpGR263A | gb/D87957 | Protein involved in sexual development | Homo sapiens | 1.2e-61 |

| DNA replication and metabolism | ||||

| Degradation of DNA | ||||

| CpGR355A | sp/P12638 | Endonuclease IV | Escherichia coli | 1.90e-52 |

| DNA replication, restriction, modification, recombination, and repair | ||||

| CpGR98A | sp/P41004 | Chromosome segregation protein | Homo sapiens | 3.90e-14 |

| CpGR376A | sp/P49005 | DNA polymerase delta small subunit | Homo sapiens | 3.40e-10 |

| CpGR299A | sp/P49643 | DNA primase 58-kDa subunit | Homo sapiens | 5.5e-05 |

| CpGR453A | gb/Z99167 | Hypothetical helicase | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 3.1e-10 |

| CpGR468A | sp/P32908 | Chromosome segregation protein | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 5.3e-16 |

| CpGr465A | sp/O12749 | DNA repair protein RHC18 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.4e-11 |

| CpGR152A | emb/X81813 | Small subunit of DNA polymerase delta | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.9e-08 |

| CpGR433A | pir/S67922 | Telomeric DNA binding protein 1 | Homo sapiens | 8.3e-10 |

| Intracellular trafficking | ||||

| CpGR157A | gb/Z68880 | Coat protein gamma-COP-bovine | Caenorhabditis elegans | 9.40e-15 |

| CpGR457A | sp/P11442 | Clathrin heavy chain | Rattus norvegicus | 3.0e-53 |

| CpGR454A | pir/S52426 | s-SNAP protein | Loligo pealei | 5.6e-15 |

| CpGR277A | sp/P35200 | Small chain of the clathrin-assembly proteins | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.3e-12 |

| CpGR179B | gb/U81030 | Treacle | Mus musculus | 1.2e-09 |

| CpGR42B/310A/B/36A | pir/S51683 | Organelle heat shock protein 70 | Eimeria tenella | 1.30e-89 |

| Membrane transport | ||||

| CpGR211A | sp/P23787 | Transitional ER ATPase | Xenopus laevis | 2.10e-35 |

| CpGR236A/B | pir/S71261 | V-type proton-ATPase | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 2.00e-36 |

| CpGR222A | sp/P38735 | Probable ATP-dependent permease | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.50e-11 |

| CpGR216A | sp/p39109 | Metal resistance protein YCF1 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 6.8e-13 |

| Protein synthesis and degradation | ||||

| Ribosomal proteins | ||||

| CpGR61A | sp/P35687 | 40S ribosomal protein S21 | Oryza sativa | 4.10e-23 |

| CpGR67B | pir/S67197 | Ribosomal protein S10 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 3.30e-27 |

| CpGR62B | pir/B48470 | Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein fusion | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 3.00e-78 |

| CpGR223B | gb/L16558 | Ribosomal protein L7 | Homo sapiens | 5.40e-48 |

| CpGR229B | sp/P12947 | 60S ribosomal protein L31 | Homo sapiens | 1.30e-34 |

| CpGR168B | sp/P17702 | 60S ribosomal protein L28 | Rattus norvegicus | 1.3e-06 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, tRNAs, and their modification | ||||

| CpGR17B | gb/U89436 | Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | Homo sapiens | 1.3e-14 |

| CpGR123A | gb/Z85984 | Histidyl tRNA synthetase | Homo sapiens | 4.20e-42 |

| Posttranslational modification | ||||

| CpGR290A | sp/P50579 | Methionine aminopeptidase 2 | Homo sapiens | 1.4e-06 |

| CpGR295A | sp/O63009 | Protein arginine N-methyltransferase | Rattus norvegicus | 1.6e-75 |

| Protein modification and translation factors | ||||

| CpGR70A/B | gb/U71180 | Elongation factor 1 alpha | Cryptosporidium parvum | 2.50e-131 |

| CpGR357A | gb/D21163 | Elongation factor 2 | Homo sapiens | 1.70e-27 |

| CpGR438A | gb/AB002753 | Elongation factor 1 alpha | Entamoeba histolytica | 2.4e-36 |

| CpGR183A/B | gb/U48261 | Protein disulfide isomerase | Cryptosporidium parvum | 2.90e-110 |

| Degradation of proteins | ||||

| CpGR147A/B | pir/S35971 | Aspartic proteinase | Eimeria acervulina | 3.60e-37 |

| CpGR7B | gb/D78151 | 26S proteasome subunit | Homo sapiens | 3.30e-33 |

| CpGR212A | sp/P12881 | Proteasome 29-kDa subunit | Drosophila melanogaster | 1.50e-61 |

| CpGR221A/B | gb/Y09505 | Proteasome delta subunit | Nicotiana tabacum | 6.80e-28 |

| CpGR165B/118B | sp/P52488 | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.00e-17 |

| CpGR234B | gb/Z25704 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | Arabidopsis thaliana | 1.10e-17 |

| CpGR489A | sp/P50101 | Putative ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 4.6e-57 |

| CpGR461A | sp/P45181 | Probable zinc protease PQQL | Haemophilus influenzae | 3.4e-07 |

| Transcription and mRNA regulation | ||||

| CpGR395A | sp/P28370 | Possible global transcription activator | Homo sapiens | 1.20e-35 |

| CpGR141A | pir/A54964 | Spliceosome-associated protein SA | Homo sapiens | 3.60e-29 |

| CpGR194B/198B | sp/P21675 | Transcription initiation factor I | Homo sapiens | 1.3e-07 |

| CpGR473A | gb/AC002332 | Putative pre-mRNA splicing factor | Arabidopsis thaliana | 2.8e-14 |

| CpGR235B | sp/Q08111 | Nitrogen regulation protein NIFR3 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.00e-19 |

| CpGR228A | gb/X95455 | Ring zinc finger protein | Gallus gallus | 2.8e-05 |

| CpGR461A | sp/P45181 | Probable zinc protein | Haemophilus influenzae | 3.4e-07 |

| Dead box proteins | ||||

| CpGR2A/249A/B | sp/P42305 | Dead box protein, RNA helicase | Bacillus subtilis | 4.70e-15 |

| CpGR10A/372A | sp/P53131 | Putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.60e-71 |

| CpGR10B | gb/U13644 | Pre-mRNA splicing factor RNA helicase, DEAD subfamily | Caenorhabditis elegans | 7.10e-25 |

| CpGR14A | sp/P25808 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.20e-18 |

| CpGR73B | gb/U80447 | Dead box protein | Caenorhabditis elegans | 5.10e-23 |

| CpGR6A | gb/X95906 | Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor protein | Bos taurus | 7.40e-35 |

| CpGR233A | pir/A56236 | Probable RNA helicase 1 | Homo sapiens | 6.60e-48 |

| Cytoskeleton | ||||

| CpGR427A | pir/A25342 | Tubulin beta chain | Cryptosporidium parvum | 4.60e-63 |

| CpGR33A/B | gb/D50929 | KiAA0139 gene product related to mouse controsomin B | Homo sapiens | 8.80e-26 |

| CpGR396A | sp/P10587 | Myosin heavy chain | Gallus gallus | 1.0e-08 |

| Hypothetical proteins | ||||

| CpGR44A | gb/L05425 | Autoantigen | Homo sapiens | 2.60e-59 |

| CpGR91A/92A | sp/P24212 | SBMA protein | Escherichia coli | 2.00e-18 |

| CpGR140A | gb/U50078 | p619 | Homo sapiens | 5.70e-10 |

| CpGR164A | gb/Z70757 | ZK287.5 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 3.10e-11 |

| CpGR177A/194A | gb/U80437 | C43E11.9 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 9.40e-46 |

| CpGR238B | gb/U41540 | Coded for by C. elegans | Caenorhabditis elegans | 3.70e-12 |

| CpGR383A | gb/M59420 | C. parvum DNA segment B | Cryptosporidium parvum | 4.10e-111 |

| CpGR394A/408A | gb/U18112 | C. parvum ORF2 gene | Cryptosporidium parvum | 4.70e-37 |

| CpGR404A | sp/P36148/ | Hypothetical 83.6-kDa protein in CCP1-SIS2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 3.30e-11 |

| CpGR420A | gb/L29389 | Fun12p | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 6.20e-43 |

| CpGR191A | gb/X96698 | D1075-like gene product | Homo sapiens | 6.0e-05 |

| CpGR289A | gb/X98253 | ZNF183 | Homo sapiens | 2.9e-14 |

| CpGR460A | pir/S51431 | Hypothetical protein YLR186w | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 3.4e-06 |

| CpGR181A | pir/A57640 | Retinoblastoma protein-binding protein | Homo sapiens | 3.1e-06 |

| CpGR466A | pir/S68689 | Glucose regulated protein | Cricetulus griseus | 6.1e-07 |

| CpGR0493A | gb/AF017267 | Thrombospondin related | Cryptosporidium parvum | 4.2e-20 |

| rRNA and tRNA genes | ||||

| CpGR12A/B | gb/AF040725 | 5.8S/16S/18S rRNA gene | Cryptosporidium parvum | 0 |

| CpGR0309B | tRNAscan-SEb | Ile tRNA | Thiobacillus ferrooxidans | NAc |

List of GSSs sharing similarities (P ≤ 10−5) with previously reported sequences from GenBank (gb), SWISS-PROT (sp), and PIR (pir). The GSSs are sorted according to their functional categories based on the classification system developed by Riley (27). A complete and more detailed table is available (5, 35).

Identified by the program tRNAscan-SE.

NA, not applicable.

FIG. 1.

Functional classification of C. parvum GSSs, showing the proportions of predicted genes according to their putative biological functions. GSSs having a P value of ≤10−5 were classified into 12 functional categories.

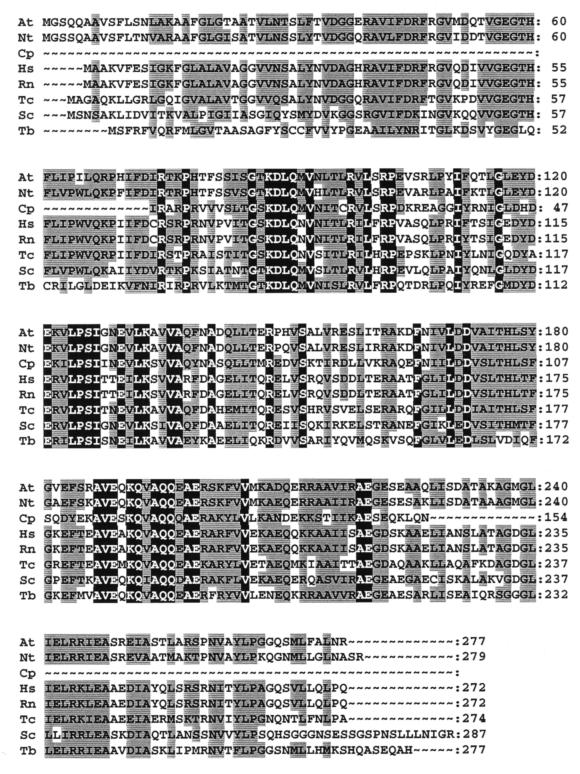

The deduced amino acid sequence of CpGR24B displayed significant similarity (P = 2.8e−53) to members of the prohibitin gene family (Fig. 2). In mammals, the prohibitin gene product has been shown to negatively regulate cell proliferation (22). In addition to gene structure, the function of this protein is conserved across many lower and higher eukaryotes. For example, the Pneumocystis carinii prohibitin gene expressed in human fibroblasts has been shown to arrest the cell cycle in the G1 phase (23). The similarity between CpGR24B and members of the prohibitin family suggests that this GSS represents a portion of a C. parvum gene which may function in controlling C. parvum proliferation and development. It is interesting to note that in yeast, prohibitin has been found to be localized within the inner mitochondrial membrane and appears to play a role in mitochondrial inheritance and regulation of mitochondrial morphology (2). However, there is no evidence for the existence of mitochondria in C. parvum, suggesting that not all prohibitin functions are conserved.

FIG. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of CpGR24B and members of the prohibitin family. The origins and accession numbers of the prohibitin sequences used in this alignment are as follows: Arabidopsis thaliana (At), U69155; Nicotiana tabacum (Nt), U69154; C. parvum (Cp), AQ023505; Homo sapiens (Hs), S85655; Rattus norvegicus (Rn), M61219; Toxocara canis (Tc), U97204; S. cerevisiae (Sc), U16737; Trypanosoma brucei (Tb), AF049901. The amino acid numbers for each sequence are indicated on the right. In the sequence alignment, identical residues are shown with a black background, and similar residues are shown with a gray background.

A total of 21 GSSs displayed limited similarity to proteins involved in the cell signaling pathway, including protein ligands, cell surface receptors and their associated proteins, and protein kinases and phosphatases. For example, CpGR231B displays limited homology to the shk1 kinase-binding protein (P = 4.0e−10). This kinase is an essential component of the Ras- and Cdc42-dependent signaling cascade, which has been demonstrated to be required for cell viability, normal morphology, and mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated signal response in the fission yeast (11). Although these GSSs are not conserved to the extent that CpGR24B is within the prohibitin gene family, the similarity of these GSSs to proteins involved in intracellular signaling provides evidence that signal transduction pathways in C. parvum are similar to those used by other eukaryotic organisms. These C. parvum proteins are likely involved in the coordination of complex host-parasite interactions, signaling with other parasites, and the regulation of growth and differentiation of parasites in response to external signals.

In addition to the GSSs that displayed similarity to known genes involved in responding to extracellular signals, several GSSs displayed limited similarity to genes involved in cell adhesion and/or recognition. CpGR176A and CpGR260A displayed similarity (P = 4.3e−6 and P = 5.1e−14) to the F-spondin precursor gene of amphibians and mammals which plays a role in cell signaling and adhesion (18). In addition, CpGR176A and CpGR260A are also similar but not identical to the previously identified C. parvum family of TRAPs (GenBank accession no. AF017267, AF073838, AF033828, X77587, and U42213) and to the phylogenetically related sporozoan proteins including the Eimeria maxima EM100 antigen (M99058), the Eimeria tenella Etp100 protein (AF032905), the Toxoplasma gondii MIC2 microneme protein (U62660), and the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein–TRAP-related protein (U34363). Members of the TRAP family of proteins have been shown to be localized in the apical end of C. parvum sporozoites and are structurally related to the micronemal proteins of Eimeria and Toxoplasma, which are involved in host-cell attachment and/or invasion (33). Another GSS, CpGR17B, displayed similarity (P = 1.3e−14) to human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase and to endothelial monocyte-activating protein II (EMAP II) (P = 7.6e−11). Recently, an EMAP II-like domain has been found at the carboxyl-terminal end of human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. The human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase is secreted as cells undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis) and is cleaved into two cytokines including the EMAP II-like molecule (37). EMAP II is a multifunctional tumor-derived cytokine that has been shown to activate endothelial cells, resulting in the elevation of cytosolic free calcium concentration, release of von Willebrand factor, induction of tissue factor, and expression of adhesion molecules such as E-selectin and P-selectin (17). In addition, mononuclear phagocytes exposed to EMAP II demonstrated the induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and tissue factor.

The above-mentioned database search could identify only C. parvum genes which were similar to sequences currently present in the public databases. Consequently, GSSs representing unique C. parvum genes or genes that have not been characterized in other organisms would not be identified. In order to estimate the actual coding capacity of C. parvum genome, all sequences were subjected to analysis for the presence of ORFs by using the program ORF Finder (25). Since the expected frequency of the three stop codons is 3/64, the longer an ORF is, the more likely it represents a coding sequence. This analysis revealed that 615 of the 654 GSSs (94%) had the potential to encode proteins, under the condition that an ORF longer than 100 amino acids was considered to be a coding sequence (25). The high percentage of potential coding sequences in our GSSs suggests that the C. parvum genome has a high gene density with little intergenic spacing.

In order to further characterize potential C. parvum genes, GSSs which contained ORFs that did not display a high degree of similarity to those in the databases were further analyzed by using the programs MOTIFS and PROFILESCAN (GCG) to determine the presence of functional protein motifs. In our analysis, only motifs with a low false-positive rate and within ORFs of >100 amino acids were characterized. This search resulted in the identification of 11 functional protein motifs or profiles (Table 2). These included ATP or GTP binding domains, signatures for transport proteins, and surface receptors. This analysis suggests that these GSSs may represent additional C. parvum genes.

TABLE 2.

Protein motifs and profiles identified in C. parvum GSSs

| GSS | Motifs and profiles |

|---|---|

| 0020B | SRP54-type protein GTP-binding domain signaturea |

| 0029A | Cytochrome c family heme-binding site signaturea |

| 0051A/B | G-protein coupled receptor signaturea |

| 0062B | Ubiquitin family signaturea |

| 0084B | ATP/GTP-binding site motif (P-loop)a |

| 0113B/0154B | Lipocalin signature (transporter of small hydrophobic molecules)a |

| 0275A/0343A | Trp-Asp (WD-40) repeat signaturea |

| 0499A | Immunoglobulin and major histocompatibility complex protein signaturea |

| 0011B | Sugar transport protein signaturesb |

| 0072B | dnaJ domain signature (heat shock protein)b |

| 0126B | GHMP kinasec putative ATP-binding domainb |

Identified by the MOTIFS program.

Identified by the PROFILESCAN program.

GHMP kinase, galactokinase-homoserine kinase-mevalonate kinase-phosphomevalonate kinase.

Identification of repetitive sequences.

Microsatellite DNA sequences, also called simple sequence repeats or simple tandem repeats, are ubiquitous elements of eukaryotic genomes. The function of these repeats is not well understood, despite a number of hypotheses that have been proposed, including modulation of gene regulation, sites of frequent recombination, and formation of left-handed DNA conformation (or Z-DNA) (13). These tandem repeats of 1- to 5-bp motifs have been found to be distributed throughout eukaryotic genomes and have been demonstrated to be useful markers for the rapid and sensitive genetic fingerprinting of an organism (34).

In order to identify potential genetic markers for strain typing and tracking of C. parvum, we analyzed the nature and frequency of microsatellite DNA sequences including all possible dinucleotide and trinucleotide repeats in the C. parvum GSSs. The GSSs containing a di- or trinucleotide repeat and the number of repeats they contained are listed in Table 3 and Table 4. Among the 57 GSSs found to contain microsatellite-like elements, the most abundant dinucleotide repeats included (TT)n, (AA)n, (TA)n, and (AT)n. Similarly, (AAT)n, (TAA)n, (TAT)n, (ATA)n, (TTA)n, and (ATT)n constitute the most abundant trinucleotide repeats. A potential role for several of these microsatellite DNA sequences as genetic markers is currently being investigated.

TABLE 3.

Numbers of simple dinucleotide repeats identified in GSSsa

| Dinucleotides | GSSs (no. of dinucleotide repeats present) |

|---|---|

| TT | 0087a (6), 0108a (6), 0115b (7), 0125b (7), 0139b (7), 0354a (7), 0210a (8), 0337a (13), 0464a (18) |

| AA | 0087b (6), 0108b (6), 0139a (7), 0333a (7), 0327a (8), 0172b (9), 0234a (9), 0254b (9) |

| TA | 0141b (6), 0333a (6), 0053a (7), 0001a (10), 0215a (10), 0142b (11), 0034a (13), 0205a (16) |

| AT | 0141b (6), 0333a (6), 0001a (8), 0053a (8), 0215a (10), 0142b (12), 0034a (13), 0205a (7) |

| GG | 0328a (6) |

| AG | 0017a (7) |

| GA | 0017a (6) |

C. parvum GSSs were searched for all possible dinucleotide repeats containing more than five repeat units by using the FINDPATTERNS program (GCG). No mismatches were allowed. The number of repeats in each sequence is shown in parentheses. More than five repeats of TG, CG, CA, GT, CT, GC, AC, TC, and CC were not found.

TABLE 4.

Numbers of simple trinucleotide repeats identified in GSSsa

| Trinucleotide | GSSs (no. of trinucleotide repeats present) |

|---|---|

| AAT | 0149b (4), 0210a (4), 0217a (4), 0223a (4), 0307a (4), 0488a (4), 0342a (5), 0307b (6), 0143b (7), 0107a (8), 0200a (9) |

| TAA | 0149b (4), 0217a (4), 0307a (4), 0342a (4), 0488a (4), 0307b (5), 0143b (6), 0107a (7), 0200a (8) |

| TAT | 0012b (4), 0047a (4), 0186b (4), 0171a (5), 0205a (5), 0230b (5), 0348a (5), 0371a (5), 0441a (7) |

| ATA | 0217a (4), 0307a (4), 0342 (4), 0149b (5), 0307b (5), 0143b (7), 0107a (8), 0200a (8) |

| TTA | 0017b (4), 0186b (4), 0205a (4), 0171a (5), 0230b (5), 0371a (5), 0348a (6), 0441a (7) |

| ATT | 0012b (4), 0186b (4), 0205a (4), 0171a (5), 0230b (5), 0348a (5), 0371a (6), 0441a (7) |

| CTT | 0183b (4), 0246a (4), 0090b (5), 0145a (6) |

| TTC | 0183b (4), 0246a (4), 0090b (5), 0145a (6) |

| ATG | 0102a (4), 0173a (4), 0342a (4) |

| TGA | 0102a (4), 0173a (4), 0342a (4) |

| TCA | 0102b (5), 0173b (6), 0342a (7) |

| GAT | 0102a (4), 0173a (4), 0342a (5) |

| TCT | 0090b (4), 0246a (4), 0145a (5) |

| CAT | 0102b (4), 0173b (5), 0342a (7) |

| ATC | 0102b (5), 0173b (6), 0342a (8) |

| CCT | 0145a (4), 0368a (5) |

| GAG | 0347a (4) |

| AGG | 0347a (4) |

| TAG | 0090b (15) |

| TTG | 0327a (4) |

| CTG | 0426a (4) |

| GGA | 0347a (4) |

| GTA | 0090b (14) |

| CTA | 0090a (7) |

| GCT | 0426a (4) |

| AGT | 0090b (15) |

| ACT | 0090a (7) |

| TGC | 0426a (4) |

| TAC | 0090a (7) |

| TCC | 0368a (6) |

| CTC | 0368a (5) |

C. parvum GSSs were searched for all possible trinucleotide repeats containing more than three repeat units by using the FINDPATTERNS program (GCG). No mismatches were allowed. The number of repeats in each sequence is shown in parentheses. More than three repeats of GTG, GCG, AAG, ACG, TGG, TCG, CGG, CAG, CCG, GAA, GCA, AGA, ACA, CGA, CAA, CCA, GGT, GTT, TGT, CGT, GGC, GAC, GTC, GCC, AGC, AAC, ACC, CGC, and CAC were not found.

To further characterize structural features of the C. parvum genome, we examined the GSSs for the presence of additional repetitive sequences. This analysis identified two GSSs, CpGR265A and CpGR254, that contained complex repetitive sequences. CpGR265A contained multiple direct repeats of 14 bp with a consensus sequence 5′ TCTCTTTCAATYCT 3′. Twenty-five copies of the direct repeat were present within 512 bp of sequence. Database searching revealed no significant identity with any other sequences. Similarly, CpGR254 contained 48 copies of an imperfect direct repeat sequence T(2–12)AG(3–5). This basic repeat unit was similar in base composition and structure to telomeric sequences characterized from other lower and higher eukaryotes (14). Further characterization demonstrated that this repetitive sequence represents a portion of a C. parvum telomeric DNA sequence (19).

Analysis of nucleotide compositions.

To investigate the correlation between the nucleotide composition of a sequence and its coding potential in the C. parvum genome, the nucleotide compositions of the GSSs were calculated with the program COMPOSITION (GCG) and compared with those of known C. parvum coding sequences. The coding sequences used in this study (accession nos. AF001211, U24082, U90628, L31806, AF013984, U34390, U95995, AF017267, U41365, U95996, S76665, U48261, U35027, S76666, U11761, U48717, U35028, U18120, U65981, U42213, U21667, U71181, L08612, U22892, U83169, and M86241) were retrieved from GenBank with the FETCH program (GCG). The overall AT contents were 62.4% for the coding sequences and 68.0% for the random sequences, suggesting that there is no bias against AT content in the coding region as has been found for other eukaryotes (24). However, an interesting discrepancy was observed when the frequencies of individual nucleotides in the coding and the random sequences were compared. The frequencies of A (33.1%) and C (17.0%) in the coding sequences were nearly identical to those in the random sequences (A, 33.7%; C, 16.1%). In contrast, the occurrence of G in coding sequences (20.6%) is 32% greater than that in the random sequences (15.9%). This was offset by the corresponding decrease in the occurrence of T (29.3% in the coding sequences and 34.3% in the random sequences). Previously, a bias of GC content has been reported in C. parvum (10). Our analysis demonstrated that this bias is due to the preference of G in the coding sequences. The relevance, if any, of this finding is not clear.

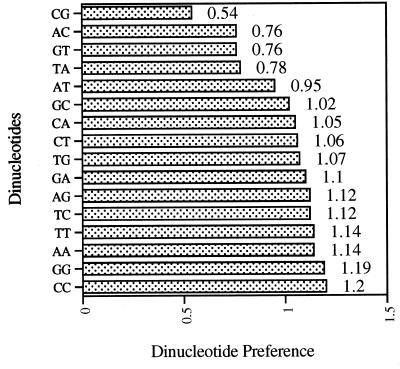

To investigate the presence of dinucleotide bias in the C. parvum genome, the dinucleotide preference (DiP) of the random genomic sequences was calculated by dividing the observed frequency of the dinucleotide by its expected frequency (Fig. 3). Dinucleotides CG (0.54), AC (0.76), GT (0.76), and TA (0.78) are significantly disfavored in the C. parvum genome. The low dinucleotide frequency (DiF) of dinucleotides CG and TA is consistent with the fact that both these dinucletides are underrepresented in the genes of Drosophila and a wide range of bacteria, yeast, primates, and other apicomplexans (7). Previously, the low DiF of dinucleotide CG was observed, based on the study of four C. parvum sequences (4).

FIG. 3.

DiP in C. parvum GSSs. The observed DiF in C. parvum GSSs was calculated with the COMPOSITION program (GCG). The expected DiF was calculated by multiplying the observed frequencies of the two mononucleotides that constitute the dinucleotide. The DiP for a dinucleotide was calculated as the ratio of its observed DiF to its expected DiF. The DiPs were plotted against their corresponding dinucleotide sequences. The actual value for each DiP is indicated on the right of each column.

Comparison of different sequencing approaches.

The efficiencies of C. parvum gene discovery with random genomic sequencing and EST sequencing were compared to determine the usefulness of each of these approaches. The GSSs generated in this study were compared to 567 C. parvum sporozoite ESTs (5). The average sequence length of the GSSs (496 bp) is longer than that of the ESTs (476 bp), which may be attributed to the length of the cDNA insert, which is shorter than that of the genomic sequence insert. A total of 384 unique ESTs were generated, at a redundancy rate of 32.3%, which is significantly higher than that of the GSS project (6%; 408 individual contigs generated from 432 random clones). However, as ESTs are derived from expressed sequences, all 384 unique ESTs are assumed to represent expressed C. parvum genes regardless of their matching with database entries. Among the unique ESTs, 37% (142 of 384) displayed significant similarity with sequences in the current databases. In contrast, 26% of the individual genomic contigs (107 of 408) displayed significant similarity with sequences in the current databases. This difference is not unexpected, as GSSs do not necessarily represent coding sequences. In general, the characteristics of the C. parvum GSS and EST projects are comparable with those conducted on other organisms, in terms of total sequence length, percentage of sequences with database match, and redundancy rate (6, 8).

In order to examine the redundancy of sequence data generated between the ESTs and GSSs, the ESTs were compiled into a local database and searched with our GSSs. Forty-eight of the 654 GSSs (7.3%) matched sequences present in 33 of the C. parvum ESTs (33 of 568 [5.8%]). Eighteen of these 33 EST sequences matched database entries. Among the 18 sequences, five sequences encoded rRNA and proteins, eight sequences encoded proteins with known functions, and five sequences encoded hypothetical proteins.

During the course of our study, another C. parvum GSS project (5) and a C. parvum sequence tagged site project (26) were initiated. To determine the redundancy of sequences generated from different sources with the same genomic DNA sequencing approach, sequences generated from these projects were retrieved from GenBank, compiled into separate local databases, and searched with our GSSs. One hundred twenty-nine of our C. parvum GSSs (19%) matched 134 GSSs (8.9%) retrieved from the public databases. Eight (1.2%) of our GSSs matched seven (7 of 149 [4.7%]) retrieved C. parvum sequence tagged sites. The above analysis indicates that currently there are relatively few redundancies among C. parvum sequences generated by different approaches or from different sources using the same genomic DNA sequencing approach. This will change as more sequences become available.

Concluding comments.

In this study, we employed a random genomic sequencing approach to conduct a general survey of the organizational characteristics and informational content of the 10.4-Mb C. parvum genome. Of the 408 assembled contigs, 107 displayed significant similarity with gene sequences currently in the public databases. These 107 putative C. parvum genes were identified from a total of 256,935 bp of unique genomic sequence. This predicts a minimum gene density of approximately 1 gene/2,500 bp of genomic sequence. In related work, we have obtained more than 15 kb of contiguous DNA sequence from the smallest C. parvum chromosome. Within this locus, eight expressed ORFs were identified (unpublished data). The gene density identified at this locus (8 genes/15 kb) is approximately 1 gene/2,000 bp, consistent with that predicted from the GSS data. This predicted gene density suggests that the 10.4-Mb C. parvum genome may contain ∼4,000 to 5,000 genes, comparable to the coding capacity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which has a genome size of 13.5 Mb and contains 5,800 genes (12). Other data (16, 30, 31) and analysis of the transcript sizes of the eight ORFs on the smallest C. parvum chromosome (unpublished data) suggest that the average size of the transcript (untranslated and coding sequences) of a C. parvum gene is 1,000 to 2,000 bases (unpublished data). Together these data predict that approximately 50 to 75% (the number of genes times the average length of a gene) of the C. parvum genome is transcribed into RNA sequences. As the GSS analysis could not identify those genes without database matches, the above-estimated coding capacity of the C. parvum genome may be less than the actual capacity. Indeed, the ORF analysis of nonmatching GSSs indicates that many of these sequences likely represent additional C. parvum genes.

Repetitive sequences are known to be present in eukaryote genomes at significantly different frequencies (9). Of the 408 contigs generated in this study, only two contained direct repeat sequences, one of which represented a telomeric sequence (19). This suggests that repetitive sequences may comprise < 0.5% of the C. parvum genome. This percentage is significantly lower than that reported in similar studies for other organisms. In addition to direct repeat sequences, diverse microsatellite sequences have been identified in this study, constituting less than 1% of the C. parvum genome that was characterized (2,308 of 250,000 bp). The paucity of repetitive sequences is consistent with the notion that a large percentage of the C. parvum genome contains coding sequences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bruce A. Roe (University of Oklahoma) for help in initiating this project. We are also grateful to Alison A. Schroeder and Cheryl A. Lancto for technical assistance, Yuan Wang for batch submission of GSSs to GenBank, and Elizabeth Shoop from Computational Biology Center (University of Minnesota) for the analysis and web publication of GSSs.

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (AI-35479) and the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station to M.S.A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger K H, Yaffe M P. Prohibitin family members interact genetically with mitochondrial inheritance components in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4043–4052. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blunt D S, Khramtsov N V, Upton S J, Montelone B A. Molecular karyotype analysis of Cryptosporidium parvum: evidence for eight chromosomes and a low-molecular-size molecule. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:11–13. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.1.11-13.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Char S, Kelly P, Naeem A, Farthing M J. Codon usage in Cryptosporidium parvumdiffers from that in other Eimeriorina. Parasitology. 1996;112:357–362. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000066580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cryptosporidium parvum sequence tag home page. 2 November 1998, posting date. [Online.] http://medsfgh.ucsf.edu/id/CpTags/home.html. [10 April 1999, last date accessed.]

- 6.Dame J B, Arnot D E, Bourke P F, Chakrabarti D, Christodoulou Z, Coppel R L, Cowman A F, Craig A G, Fischer K, Foster J, Goodman N, Hinterberg K, Holder A A, Holt D C, Kemp D J, Lanzer M, Lim A, Newbold C I, Ravetch J V, Reddy G R, Rubio J, Schuster S M, Su X Z, Thompson J K, Werner E B, et al. Current status of the Plasmodium falciparumgenome project. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;79:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02641-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis J, Griffin H, Morrison D, Johnson A M. Analysis of dinucleotide frequency and codon usage in the phylum Apicomplexa. Gene. 1993;126:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Sayed N M, Donelson J E. A survey of the Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiensegenome using shotgun sequencing. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;84:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02792-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epplen J T, Maueler W, Epplen C. Exploiting the informativity of ‘meaningless’ simple repetitive DNA from indirect gene diagnosis to multilocus genome scanning. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1994;375:795–801. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1994.375.12.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fayer R. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbreth M, Yang P, Wang D, Frost J, Polverino A, Cobb M H, Marcus S. The highly conserved skb1 gene encodes a protein that interacts with Shk1, a fission yeast Ste20/PAK homolog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13802–13807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goffeau A, Barrell B G, Bussey H, Davis R W, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel J D, Jacq C, Johnston M, Louis E J, Mewes H W, Murakami Y, Philippsen P, Tettelin H, Oliver S G. Life with 6000 genes. Science. 1996;274:563–567. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamada H, Seidman M, Howard B H, Gorman C M. Enhanced gene expression by the poly(dT-dG) · poly(dC-dA) sequence. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:2622–2630. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.12.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson E. Telomere DNA structure. In: Blackburn E H, Greider C W, editors. Telomeres. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoepelman A I. Current therapeutic approaches to cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:871–880. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.5.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins M C, Fayer R, Tilley M, Upton S J. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding epitopes shared by 15- and 60-kilodalton proteins of Cryptosporidium parvumsporozoites. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2377–2382. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2377-2382.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao J, Houck K, Fan Y, Haehnel I, Libutti S K, Kayton M L, Grikscheit T, Chabot J, Nowygrod R, Greenberg S, et al. Characterization of a novel tumor-derived cytokine. Endothelial-monocyte activating polypeptide II. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25106–25119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klar A, Baldassare M, Jessell T M. F-spondin: a gene expressed at high levels in the floor plate encodes a secreted protein that promotes neural cell adhesion and neurite extension. Cell. 1992;69:95–110. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90121-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, Schroeder A A, Kapur V, Abrahamsen M S. Telomeric sequences of Cryptosporidium parvum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;94:291–296. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe T M, Eddy S R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manger I D, Hehl A, Parmley S, Sibley L D, Marra M, Hillier L, Waterston R, Boothroyd J C. Expressed sequence tag analysis of the bradyzoite stage of Toxoplasma gondii: identification of developmentally regulated genes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1632–1637. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1632-1637.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClung J K, Jupe E R, Liu X T, Dell’Orco R T. Prohibitin: potential role in senescence, development, and tumor suppression. Exp Gerontol. 1995;30:99–124. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(94)00069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narasimhan S, Armstrong M, McClung J K, Richards F F, Spicer E K. Prohibitin, a putative negative control element present in Pneumocystis carinii. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5125–5130. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5125-5130.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliver J L, Marin A. A relationship between GC content and coding-sequence length. J Mol Evol. 1996;43:216–223. doi: 10.1007/BF02338829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ORF Finder home page. 26 February 1999, posting date. [Online.] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html. [10 April 1999, last date accessed.]

- 26.Piper M B, Bankier A T, Dear P H. A HAPPY map of Cryptosporidium parvum. Genome Res. 1998;8:1299–1307. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.12.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riley M. Functions of the gene products of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:862–952. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.862-952.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roe B A, Crabtree J S, Khan A S. DNA isolation and sequencing. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroeder A A, Brown A M, Abrahamsen M S. Identification and cloning of a developmentally regulated Cryptosporidium parvumgene by differential mRNA display PCR. Gene. 1998;216:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeder A A, Lawrence C E, Abrahamsen M S. Differential mRNA display cloning and characterization of a Cryptosporidium parvumgene expressed during intracellular development. J Parasitol. 1999;85:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith M W, Aley S B, Sogin M, Gillin F D, Evans G A. Sequence survey of the Giardia lambliagenome. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;95:267–280. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spano F, Putignani L, Naitza S, Puri C, Wright S, Crisanti A. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a Cryptosporidium parvumgene encoding a new member of the thrombospondin family. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;92:147–162. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tautz D, Schlotterer C. Simple sequences. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:832–837. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.University of Minnesota Cryptosporidium parvum genomic survey sequences home page. 21 June 1998, posting date. [Online.] http://www.cbc.umn.edu/ResearchProjects/Cp/. [10 April 1999, last date accessed.]

- 36.Verdun R E, Di Paolo N, Urmenyi T P, Rondinelli E, Frasch A C C, Sanchez D O. Gene discovery through expressed sequence tag sequence in Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5393–5398. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5393-5398.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wakasugi K, Schimmel P. Two distinct cytokines released from a human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Science. 1999;284:147–151. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]