Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

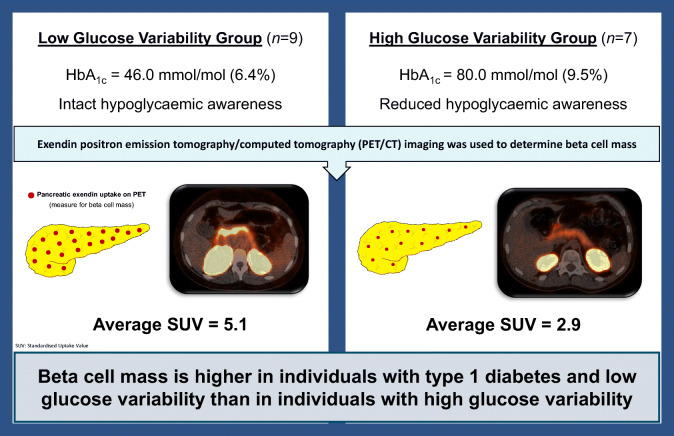

The role of beta cell mass in the balance of glucose control and hypoglycaemic burden in people with type 1 diabetes is unclear. We applied positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with radiolabelled exendin to compare beta cell mass among people with type 1 diabetes and either low glucose variability (LGV) or high glucose variability (HGV).

Methods

All participants with either LGV (n=9) or HGV (n=7) underwent a mixed-meal tolerance test to determine beta cell function and wore a blinded continuous glucose monitor for a week. After an i.v. injection with [68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-exendin-4, PET images were acquired for the quantification of pancreatic uptake of radiolabelled exendin. The mean standardised uptake value (SUVmean) of the pancreas was used to determine the amount of beta cell mass.

Results

Participants with LGV had lower HbA1c (46.0 mmol/mol [44.5–52.5] [6.4% (6.3–7)] vs 80 mmol/mol [69.0–110] [9.5% (8.5–12.2)], p=0.001) and higher time in range (TIR) (75.6% [73.5–90.3] vs 38.7% [25.1–48.5], p=0.002) than those with HGV. The SUVmean of the pancreas was higher for the LGV than for the HGV group (5.1 [3.6–5.6] vs 2.9 [2.1–3.4], p=0.008). The AUCC-peptide:AUCglucose ratio was numerically, but not statistically, higher in the LGV compared with the HGV group (2.7×10−2 [6.2×10−4–5.3×10−2] vs 9.3×10−4 [4.7×10−4–5.2×10−3], p=0.21). SUVmean correlated with the AUCC-peptide:AUCglucose ratio (Pearson r=0.64, p=0.01), as well as with the TIR (r=0.64, p=0.01) and the SD of interstitial glucose levels (r=−0.66, p=0.007).

Conclusion/interpretation

Our data show higher beta cell mass in people with type 1 diabetes and LGV than in those with HGV, independent of beta cell function.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Beta cell mass, Exendin, Glucose control, Glucose variability, Hypoglycaemic burden, Pancreatic beta cell, PET imaging, Type 1 diabetes

Introduction

Despite widespread implementation of basal-bolus insulin regimens as the most adequate treatment for type 1 diabetes, there are large interindividual differences in the level of glycaemic control. Only a minority of people with type 1 diabetes achieve widely accepted treatment targets [1], which has been attributed to increased risks of hypoglycaemia associated with optimisation of glucose control. Remarkably, however, some individuals seem to have achieved HbA1c at or below target levels without a high hypoglycaemic burden, whereas others with much poorer glucose control suffer from frequent hypoglycaemia, including severe episodes, and considerable high glucose variability (HGV). Although certain psychological and behavioural factors, such as fear and consequent avoidance of hypoglycaemia [2] may explain some of these disparities, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown.

The loss of insulin production capacity in type 1 diabetes has long been considered the inevitable consequence of the complete destruction of pancreatic beta cells through a targeted cytotoxic autoimmune attack [3]. Beta cells that escape this autoimmune attack and retain functional capacity, clinically reflected by low but detectable C-peptide levels and insulin-positive immunohistochemical analysis [4–11], appear to have a positive effect on glucose variability, hypoglycaemic burden and overall glycaemic control [12, 13]. Cumulative research shows that even in longstanding type 1 diabetes, a considerable number of beta cells can survive the immune attack, even in the absence of retaining beta cell function [5–7].

Recent advances in the field of in vivo quantification of beta cells allow us to monitor beta cell mass non-invasively. Currently, the best characterised and most specific tracer to visualise beta cells in vivo is radiolabelled exendin, binding to the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor on the beta cell [14–18]. Indeed, we showed persistent beta cell mass in people with longstanding type 1 diabetes using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging [17]. To what extent such residual beta cell mass contributes to the level of glucose stability in people with type 1 diabetes is currently unknown. To examine this further, we applied the more accurate imaging technique positron emission tomography (PET) with radiolabelled exendin [19], for non-invasive quantification of beta cell mass in individuals with type 1 diabetes and glucose profiles with either low or high variability.

Research design and methods

Study participants

All study participants were recruited from the diabetes outpatient clinic of the Radboud University Medical Center (Nijmegen, the Netherlands) and through online advertisements. All individuals had to have had type 1 diabetes for at least 1 year.

Inclusion criteria for the low glucose variability (LGV) group included an HbA1c of ≤53 mmol/mol (≤7%), intact hypoglycaemic awareness (as defined by a modified Clarke score of 0 or 1 [20]) and no experience of severe hypoglycaemia, defined as an event requiring assistance from another person to recover [21], in the past year and no more than two severe events overall.

The HGV group complied with the following criteria: either an HbA1c of ≥69 mmol/mol (≥8.5%) with reduced hypoglycaemic awareness (modified Clarke score of ≥2) and/or at least two severe hypoglycaemic events in the past year, or an HbA1c of ≥64 mmol/mol (≥8.0%) with impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia (modified Clarke score of ≥3) and/or at least two severe hypoglycaemic events in the past year.

All study procedures were performed at the Radboud University Medical Center. This clinical study was approved by the local Institutional Ethics Review Committee and study participants gave written informed consent before participation (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT03785275).

Mixed-meal tolerance test

All individuals underwent a mixed-meal tolerance test (MMTT) to assess their beta cell function [22]. The MMTT was performed in the morning, preceded by a 12 h fasting period, during which only water was consumed. Participants were asked to abstain from using short-acting insulin for 6 h before the test and to reduce the dose of long-acting insulin or the basal rate of their insulin pump by 30–35% on the preceding day. Before the MMTT, blood was drawn to determine fasting glucose, C-peptide and insulin. Additionally, blood samples were taken to measure HbA1c and to assess kidney function and liver enzymes. Subsequently, participants consumed 6 ml/kg liquid meal (Nutridrink, Nutricia, the Netherlands) to a maximum of 360 ml within 5 min. Blood samples were collected at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after ingestion to determine stimulated glucose, C-peptide and insulin levels. The detection limit of the C-peptide assay was 0.01 nmol/l and in case of unmeasurable low C-peptide, 0.01 nmol/l was noted as measured value for that specific timepoint.

AUC for basal and stimulated glucose and C-peptide were calculated using Prism 5.03 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). To determine a better estimate of the residual beta cell function than the AUC for C-peptide alone, the AUCC-peptide:AUCglucose ratio was calculated. These AUC values, peak C-peptide measurements and AUCC-peptide:AUCglucose ratios were correlated with the results of the image analysis.

Continuous glucose monitoring

All participants were asked to wear a blinded glucose sensor for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) (Dexcom G4 or G6, Dexcom, San Diego, CA, USA). The Dexcom G4 system was used in the first 14 individuals and the Dexcom G6 system in the last two participants after the transition to this new CGM system. CGM data of the first participant were not available at the time of analysis. The glucose sensor for the study was placed after the MMTT to measure for a period of 7 to 8 days (depending on scan date) and was removed prior to the PET/computed tomography (CT) scan. Glycaemic variables were based on glucose measurements starting on the day after the MMTT and excluding the day of the PET/CT acquisition (because of the fasting period). The glycaemic variables included mean glucose levels with their corresponding SD and CV as measure for glycaemic variability. Furthermore, the percentage of time that glucose levels were in range (TIR, glucose 3.9 to 10.0 mmol/l), below range (TBR, <3.9 mmol/l) and above range (TAR, >10 mmol/l) were obtained.

PET/CT acquisition

Image acquisition was performed using a Siemens Biograph 40 mCT time-of-flight PET/CT system. Prior to PET/CT imaging, study participants fasted for at least 4 h to prevent interference with endogenous GLP-1 production, and insulin use was temporarily adjusted in the same manner as was done prior to the MMTT. Blood samples were drawn just prior to image acquisition to determine blood glucose levels.

Static PET images were acquired 60 min after a slow i.v. bolus injection of 76.6±2.9 MBq [68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-exendin-4 (peptide dose 3–7 μg), further referred to as exendin PET. Radiochemical preparation was done as previously described [14]. Image data were obtained with two bed positions (10 min/bed position) of the abdominal region with the pancreas in the field of view. For anatomical information and attenuation correction, a low-dose CT scan without contrast of the abdomen was acquired. The CT transaxial matrix was 512×512 (0.98×0.98 mm) with a CT slice width of 3 mm. The PET data were reconstructed with three iterations, 21 subsets and a post-reconstruction Gaussian filter of 3 mm full width at half maximum.

Quantitative image analysis

The reconstructed PET/CT images were analysed using Inveon Research Workplace 4.1 software (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Volumes of interest (VOIs) were drawn around the pancreas, duodenum and kidneys, based on the CT images. Radiolabelled exendin is cleared via the kidneys which results in high renal uptake. The kidney VOIs were dilated by 6 mm to include all renal radioactivity. Then the pancreas VOIs were corrected for the spill-over from the kidneys by excluding the activity originating from the kidney VOIs. This prevents overestimation of the pancreatic uptake resulting from the closely located left kidney. In addition, the pancreatic head is in some cases situated nearby the duodenum. Therefore, the activity that originated from the duodenal VOIs was also excluded from the VOIs of the pancreas in a similar manner as for the kidneys.

The quantification of the PET/CT data provided mean uptake values (Bq/ml). By correcting for injected activity and body weight, the mean standardised uptake value (SUVmean [unitless]) of the pancreas was determined. The SUVmean allows for a reliable comparison between individuals and patient populations with different characteristics (e.g. groups with LGV and HGV). The SUVmean of the pancreas was therefore used as measure for (residual) beta cell mass.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was determined using the data acquired in a previous study with exendin SPECT [17]. This resulted in a sample size of 18 participants, nine in each group (significance level of 0.05 and power of 0.8). Seven individuals were included in the HGV group due to difficulties in recruitment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, strict inclusion criteria and burdensome study protocol. However, this was thought acceptable given that the better spatial resolution and improved image quantification of PET would allow for better detection of small differences in pancreatic uptake compared with SPECT.

Acquired data were expressed as mean±SD, median (IQR), or number (%). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess group differences. Relationships between variables were checked for linearity using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r), with a two-tailed ANOVA. The level of significance was set at p<0.05. GraphPad Prism software was used for all analyses (GraphPad Prism 5 for Windows).

Results

We recruited nine participants to the LGV group (seven women) and seven participants to the HGV group (five men). Apart from the imbalance in women/men, the two groups did not differ with respect to age, BMI or diabetes duration (Table 1). In concordance with the protocol, HbA1c and modified Clarke scores were lower in the LGV group (Table 1). Stimulated C-peptide levels were detectable in half of all individuals, but with no differences between the groups (56% vs 43%, p=0.21). Following injection of the radiotracer, two patients experienced nausea and one vomited, which are known side effects of exendin. No other adverse effects were observed.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| Variables | LGV group (n=9) | HGV group (n=7) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.2±16.1 | 36.9±18.9 |

| Sex (female/male) | 7/2 | 2/5 |

| T1D duration (years) | 13.8 (3.0–28.0) | 13.0 (3.8–38.0) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 46.0 (44.5–52.5) | 80.0 (69.0–110.0)* |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.4 (6.3–7.0) | 9.5 (8.5–12.2)* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.9±3.3 | 25.5±2.7 |

| CKD-EPI-GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 87.3±8.0 | 89.0±2.6 |

| Score on modified Clarke questionnaire | 0 (0–1) | 3 (2–3)* |

|

Severe hypoglycaemic event in past year (events per individual) |

0 | 0.29 |

|

Severe hypoglycaemic event throughout life (events per individual) |

0.11 | 1.29 |

Data are shown as mean±SD, median (IQR) or number

*p<0.05 vs LGV group

CKD-EPI-GFR, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration glomerular filtration rate; T1D, type 1 diabetes

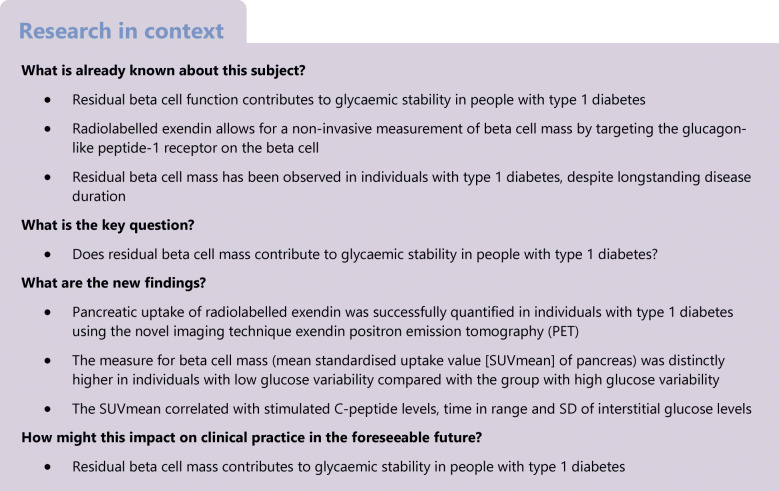

Quantification of the PET/CT images revealed that pancreatic exendin uptake was distinctly higher in the LGV group as compared with the HGV group (Fig. 1a). This was the case for both the mean uptake value (2.5 [2.1–3.2] vs 1.5 [1.0–2.0] kBq/ml, p=0.005) and SUVmean of the pancreas (5.1 [3.6–5.6] vs 2.9 [2.1–3.4], p=0.008).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of MMTT and PET/CT data. SUVmean of the pancreas (a) in individuals with LGV (green) and HGV (orange). Glucose (b) and C-peptide profiles (c) for both groups, median (IQR). Correlations of the SUVmean with the AUC for C-peptide (d), the AUCC-peptide:AUCglucose ratio (e) and with the percentage TIR (f). Two participants from the HGV group have a SUVmean of 2.90 and no detectable C-peptide and their data points are in the same location (d and e). CGM data of one participant from the HGV group were not available at the time of analysis and only six data points from this group are visualised (f)

In the MMTT, glucose and C-peptide levels were measured (Fig. 1b and c). Variables of stimulated C-peptide levels were numerically higher in the LGV compared with the HGV group, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (AUC for C-peptide, 44.6 [1.2–90.6] vs 1.2 [1.2–12.8] nmol min/l [p=0.21] and peak C-peptide level, 0.47 [0.01–1.0] vs 0.01 [0.01–0.14] nmol/l [p=0.21]). Neither BMI nor diabetes duration correlated with the AUC for C-peptide. The AUCC-peptide:AUCglucose ratio was also determined but was not different between the groups (2.7×10−2 [6.2×10−4–5.3×10−2] vs 9.3×10−4 [4.7×10−4–5.2×10−3], p=0.21).

The analysis of CGM data demonstrated that people in the LGV group had significantly higher TIR and lower mean glucose levels than those in the HGV group (Table 2). Also, both the SD of mean interstitial glucose levels and TAR were higher in the HGV group (Table 2), with no significant difference with respect to TBR between the groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data from CGM

| Variables | LGV group (n=9) |

HGV group (n=7) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean glucose (mmol/l) | 7.2 (6.3–7.9) | 10.5 (10.3–12.6)* |

| SD (mmol/l) | 2.1 (1.5–2.7) | 4.4 (3.8–4.5)* |

| CV (%) | 31.1 (22.6–36.1) | 36.3 (34.8–43.4) |

| TIR (%) | ||

| 3.9–10.0 mmol/l | 75.6 (73.5–90.3) | 38.7 (25.1–48.5)* |

| TBR (%) | ||

| <3.0 mmol/l | 3.6 (0.1–6.7) | 0.2 (0.0–2.0) |

| <3.9 mmol/l | 6.6 (1.0–16.7) | 1.9 (0.1–6.8) |

| TAR (%) | ||

| >10 mmol/l | 8.4 (4.4–19.8) | 53.9 (47.3–66.8)* |

| >13.9 mmol/l | 0.2 (0.0–2.7) | 21.3 (18.9–39.8)* |

Data are expressed as median (IQR)

*p<0.05 vs LGV group

The uptake of exendin in the pancreas correlated to beta cell function (expressed as stimulated C-peptide), as reflected by correlations between the SUVmean and the AUC for C-peptide (Pearson r=0.62, p=0.01, Fig. 1d), peak C-peptide value (Pearson r=0.65, p=0.007), and AUCC-peptide:AUCglucose ratio (Pearson r=0.64, p=0.01, Fig. 1e). Nevertheless, one of the individuals with LGV and no detectable C-peptide had a similar SUVmean as the individual with the highest stimulated C-peptide, which was much greater than in another individual without detectable C-peptide (Fig. 2). Furthermore, SUVmean correlated with TIR (Pearson r=0.64, p=0.01, Fig. 1f) and was inversely correlated with the mean glucose levels (Pearson r=−0.59, p=0.02), SD of glucose levels (Pearson r=−0.66, p=0.007) and TAR (Pearson r=−0.64, p=0.01). We observed no correlations between the SUVmean of the pancreas and BMI, diabetes duration, age at disease onset and blood glucose levels prior to imaging.

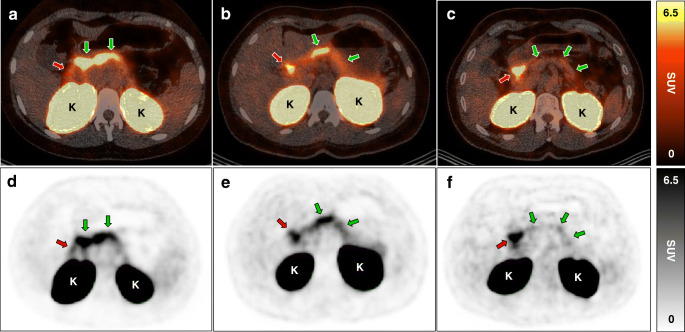

Fig. 2.

Abdominal PET/CT images with pancreatic uptake of radiolabelled exendin. Transversal fused PET/CT images (a–c) and PET images (d–f) of three individuals showing pancreatic uptake of 68Ga-exendin as measure for beta cell mass (green arrows). Other regions with exendin uptake are the proximal duodenum (red arrows) and the kidneys (indicated with the letter ‘K’). Pancreatic exendin uptake of individuals with LGV were in the same range for individual 1 (a, d) (AUC for C-peptide 122 nmol min/l) and individual 2 (b, e) (no detectable C-peptide), despite differences in C-peptide response, and much greater than in individual 3 (c, f) (no detectable C-peptide)

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that beta cell mass as quantified by exendin PET was higher in people with type 1 diabetes and LGV compared with those with HGV. Multiple correlations were found between glycaemic variables and beta cell mass, pointing towards the importance of residual beta cells for the level of glycaemic control. Altogether, these results strongly support that preservation of beta cell mass additionally benefits glycaemic stability in people with type 1 diabetes alongside beta cell function.

In spite of historical belief, there is increasing evidence for beta cell survival in longstanding type 1 diabetes, substantiated by the presence of insulin-positive residual beta cells, and measurable levels of C-peptide and proinsulin [4–11, 23–25]. Using the novel imaging technique exendin PET, relevant pancreatic uptake of radiolabelled exendin was found in most study participants, consistent with the presence of residual beta cell mass, despite diabetes durations ranging from 2 to 50 years. This shows that beta cells can survive many years after the onset of diabetes. The greater exendin uptake in the LGV compared with the HGV group may underscore the importance of residual beta cell mass for glycaemic variables from a clinical point of view. Although residual beta cell function, as reflected by measurable C-peptide during the MMTT, may have contributed to better glycaemic stability [12, 26, 27], it is unlikely that this explains all the benefits. Indeed, observations of LGV in participants with high beta cell mass, despite undetectable C-peptide levels, argue for a beneficial role of beta cell mass, independent of beta cell function.

This disconnection between beta cell mass and function is best illustrated by two individuals with similar beta cell mass, one of whom displayed relatively high residual C-peptide production, whereas it was unmeasurable in the other (Fig. 2). The presence of beta cell mass thus does not necessarily mean that these residual beta cells are insulin-positive, let alone insulin-producing [5–7], while being positive for the GLP-1 receptor, yet the association with glycaemic variables suggests some functionality. A possible explanation may be suppression of glucagon release from alpha cells by residual beta cells [28] or a lower state of inflammation, both of which may allow for better glucose control. Future studies should consider also measuring glucagon, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies to obtain a better understanding of this observation. The amount of beta cell mass, its potentially beneficial effect on glucose outcomes and the mechanisms behind this beneficial effect should be studied more extensively to understand the clinical significance of residual beta cell mass.

Radiolabelled exendin is so far the best characterised tracer for quantification of beta cell mass using the GLP-1 receptor as target. The uptake of the tracer in the pancreas correlates linearly with beta cell mass [15–18] and not with alpha cell mass [15], and remains unaffected by insulitis [16, 18]. Although some expression of the GLP-1 receptor can be found on delta cells [29], islet mass is made up of maximum 5% of delta cells [30, 31], meaning that their influence on tracer uptake will not lead to relevant bias. Furthermore, we have previously shown colocalisation between uptake of radiolabelled exendin and insulin-positive regions in human pancreas tissue, with a distinctly higher uptake compared with the background activity in the exocrine tissue (unpublished data: M. Gotthardt, T.J.P. Jansen, M. Buitinga, C. Frielink, M.W.J. Stommel, M.B. van der Kolk, H. van Goor, B.E. de Galan, M. Boss and M .Brom). An important matter to keep in mind when using exendin PET is the downregulation of GLP-1 receptor expression with prolonged hyperglycaemia [32, 33], which could affect quantification of beta cell mass [34]. To minimise biased results because of differences in blood glucose values between the two groups, participants were asked to keep their blood glucose in the normal range before PET imaging. Blood glucose levels measured just before image acquisition did not differ between the groups. We would also like to point out that alpha cells can increase intra-islet GLP-1 levels, potentially saturating the GLP-1 receptors on the beta cells leading to lower uptake of our tracer [35, 36]. To minimise this effect, use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in the past 6 months was an exclusion criterion and all participants had been fasting for at least 4 h before the PET/CT scan.

In addition to measuring beta cell mass, alpha cell mass would also be interesting to include when studying the relation between beta cell mass and glucose variability. Pancreas volume substantially decreases in type 1 diabetes [37], but data obtained from donor pancreases showed that alpha cell mass did not change [30]. It would be valuable to see how alpha cell mass relates to beta cell mass and function in an in vivo setting. The development of imaging techniques that measure alpha cell mass is currently ongoing, the combination of alpha cell mass and beta cell mass imaging might lead to new insights regarding glucose variability. Studies have already been performed with a tracer targeting the glucagon receptor [38, 39], and novel tracers may give us detailed information on the role pancreatic cells have on glycaemic variability.

Our study has strengths and limitations. A strength is the extensive phenotyping of the study participants with regard to both beta cell function and mass, which allowed us to examine the (independent) role of beta cell mass. One of the limitations is that our imaging data on residual beta cells could not be validated by direct histological examination of pancreatic tissue. Acquiring histology data would entail serious risks for the participants and is not feasible for ethical reasons [40]. However, we have previously demonstrated GLP-1 receptor expression in insulin-positive and insulin-negative beta cells of individuals with type 1 diabetes (unpublished data: M. Boss, I. Kusmartseva, W. Woliner-van der Weg, L. Joosten, M. Brom, M. Béhe, C.J. Tack, O.C. Boerman, M.J.R. Janssen, M. Atkinson and M. Gotthardt) and have shown in rodents as well as in humans that radiolabelled exendin is a good biomarker for beta cell mass, demonstrating the high specificity of the tracer [15–18]. Another limitation is the small group size. However, participation in this study required individuals to undergo extensive study procedures that were both labour-intensive and burdensome for participants and research staff. Although this may have influenced the statistical power to demonstrate differences in C-peptide levels between the groups, the number was sufficient for the primary outcome, i.e. the beta cell mass and its association with beneficial glycaemic variables as previously described. Finally, the imbalance of female/male participants between the groups may be a limitation, but there are no indications that sex is related to differences in beta cell function or glycaemic control [41], therefore we expect that our results were not influenced by this imbalance.

In summary, our data show that beta cell mass is distinctly higher in people with type 1 diabetes and relatively stable glucose control compared with people with type 1 diabetes in whom glucose levels are much more variable. This finding might point towards an important role that residual beta cells can play in maintaining glycaemic stability and underscores the importance of keeping viable beta cells, even if they appear ‘non-functional’. Surviving beta cells are also of great interest for novel and future interventions that may help to restore or expand their functionality and improve glycaemic control. Exendin PET may contribute to detect these residual beta cells and also represents a valuable tool for clinical studies longitudinally monitoring beta cell mass during the course of diabetes or interventions aiming at preserving beta cell mass in clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the technicians from the Department of Medical Imaging (Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands) for their assistance and help with the PET/CT imaging. We also thank all the laboratory technicians from the Department of Medical Imaging for their help with the radiolabelling and assistance in the laboratory, and the diabetes consultants from the Department of Internal Medicine for their support and advice with the continuous glucose monitors, especially S. Hendriks (Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands). We would like to express our greatest gratitude to all the study participants for their valuable contribution.

Authors’ relationships and activities

BEDG is an associate editor for Diabetologia but was not involved in handling of the manuscript during the editorial process. All other authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Contribution statement

All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the acquired data. Data analysis was performed by TJPJ. The article was drafted by TJPJ and all authors were involved in the revision process and approved the final version. The guarantor of this work is MG who accepts full responsibility for the work and/or conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish.

Abbreviations

- CGM

Continuous glucose monitoring

- CT

Computed tomography

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- HGV

High glucose variability

- LGV

Low glucose variability

- MMTT

Mixed-meal tolerance test

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SUVmean

Mean standardised uptake value

- TAR

Time above range

- TBR

Time below range

- TIR

Time in range

- VOI

Volume of interest

Funding

This work is supported by BetaCure (FP7/2014–2018, grant agreement 602812), and IMI2-JU under grant agreement No 115797 (INNODIA) and No 948268 (INNODIA HARVEST). This joint undertaking receives support from the Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program and EFPIA, JDRF and The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. This work is also supported by Diabetes Foundation The Netherlands Fellowship (2015-81-1845).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association (2021) 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care 44(Suppl 1):S15–S33. 10.2337/dc21-S002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Chatwin H, Broadley M, Speight J, et al. The impact of hypoglycaemia on quality of life outcomes among adults with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;174:108752. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson MA, Roep BO, Posgai A, Wheeler DCS, Peakman M. The challenge of modulating beta-cell autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(1):52–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30112-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oram RA, Jones AG, Besser RE, et al. The majority of patients with long-duration type 1 diabetes are insulin microsecretors and have functioning beta cells. Diabetologia. 2014;57(1):187–191. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3067-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oram RA, Sims EK, Evans-Molina C. Beta cells in type 1 diabetes: mass and function; sleeping or dead? Diabetologia. 2019;62(4):567–577. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4822-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu MG, Keenan HA, Shah HS, et al. Residual beta cell function and monogenic variants in long-duration type 1 diabetes patients. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(8):3252–3263. doi: 10.1172/JCI127397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keenan HA, Sun JK, Levine J, et al. Residual insulin production and pancreatic ss-cell turnover after 50 years of diabetes: Joslin Medalist Study. Diabetes. 2010;59(11):2846–2853. doi: 10.2337/db10-0676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oram RA, McDonald TJ, Shields BM, et al. Most people with long-duration type 1 diabetes in a large population-based study are insulin microsecretors. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(2):323–328. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sims EK, Bahnson HT, Nyalwidhe J et al (2018) Proinsulin secretion is a persistent feature of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 10.2337/dc17-2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Rodriguez-Calvo T, Zapardiel-Gonzalo J, Amirian N, et al. Increase in pancreatic proinsulin and preservation of beta-cell mass in autoantibody-positive donors prior to type 1 diabetes onset. Diabetes. 2017;66(5):1334–1345. doi: 10.2337/db16-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sims EK, Syed F, Nyalwidhe J et al (2019) Abnormalities in proinsulin processing in islets from individuals with longstanding T1D. Transl Res. 10.1016/j.trsl.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gibb FW, McKnight JA, Clarke C, Strachan MWJ. Preserved C-peptide secretion is associated with fewer low-glucose events and lower glucose variability on flash glucose monitoring in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2020;63(5):906–914. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05099-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda M, Tanaka A, Tahara Y, et al. Correlation between minimal secretory capacity of pancreatic beta-cells and stability of diabetic control. Diabetes. 1988;37(1):81–88. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.37.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boss M, Buitinga M, Jansen TJ, Brom M, Visser EP, Gotthardt M (2019) PET-based dosimetry of [(68)Ga]Ga-NODAGA-exendin-4 in humans, a tracer for beta cell imaging. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 10.2967/jnumed.119.228627

- 15.Brom M, Joosten L, Frielink C, Boerman O, Gotthardt M. (111)In-exendin uptake in the pancreas correlates with the beta-cell mass and not with the alpha-cell mass. Diabetes. 2015;64(4):1324–1328. doi: 10.2337/db14-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brom M, Joosten L, Frielink C, et al. Validation of (111)In-exendin SPECT for the determination of the beta-cell mass in biobreeding diabetes-prone rats. Diabetes. 2018;67(10):2012–2018. doi: 10.2337/db17-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brom M, Woliner-van der Weg W, Joosten L, et al. Non-invasive quantification of the beta cell mass by SPECT with (1)(1)(1)In-labelled exendin. Diabetologia. 2014;57(5):950–959. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joosten L, Brom M, Peeters H, et al. Measuring the pancreatic beta cell mass in vivo with exendin SPECT during hyperglycemia and severe insulitis. Mol Pharm. 2019;16(9):4024–4030. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gotthardt M, Eizirik DL, Aanstoot HJ et al (2018) Detection and quantification of beta cells by PET imaging: why clinical implementation has never been closer. Diabetologia. 10.1007/s00125-018-4745-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Janssen MM, Snoek FJ, Heine RJ. Assessing impaired hypoglycemia awareness in type 1 diabetes: agreement of self-report but not of field study data with the autonomic symptom threshold during experimental hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(4):529–532. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Hypoglycaemia Study Group (2017) Glucose concentrations of less than 3.0 mmol/l (54 mg/dl) should be reported in clinical trials: a joint position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia 60(1):3–6. 10.1007/s00125-016-4146-6. Erratum: 60:377. 10.1007/s00125-016-4168-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Moran A, Bundy B, Becker DJ, et al. Interleukin-1 antagonism in type 1 diabetes of recent onset: two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet. 2013;381(9881):1905–1915. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60023-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam CJ, Jacobson DR, Rankin MM, Cox AR, Kushner JA. beta cells persist in T1D pancreata without evidence of ongoing beta-cell turnover or neogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(8):2647–2659. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez-Calvo T, Richardson SJ, Pugliese A. Pancreas pathology during the natural history of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(11):124. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meier JJ, Bhushan A, Butler AE, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Sustained beta cell apoptosis in patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes: indirect evidence for islet regeneration? Diabetologia. 2005;48(11):2221–2228. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1949-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lachin JM, McGee P, Palmer JP, Group DER Impact of C-peptide preservation on metabolic and clinical outcomes in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes. 2014;63(2):739–748. doi: 10.2337/db13-0881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rickels MR, Evans-Molina C, Bahnson HT, et al. High residual C-peptide likely contributes to glycemic control in type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(4):1850–1862. doi: 10.1172/JCI134057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banarer S, McGregor VP, Cryer PE. Intraislet hyperinsulinemia prevents the glucagon response to hypoglycemia despite an intact autonomic response. Diabetes. 2002;51(4):958–965. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Segerstolpe A, Palasantza A, Eliasson P, et al. Single-cell transcriptome profiling of human pancreatic islets in health and type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2016;24(4):593–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright JJ, Saunders DC, Dai C, et al. Decreased pancreatic acinar cell number in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2020;63(7):1418–1423. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05155-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arrojo EDR, Jacob S, Garcia-Prieto CF, et al. Structural basis for delta cell paracrine regulation in pancreatic islets. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3700. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11517-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu G, Kaneto H, Laybutt DR, et al. Downregulation of GLP-1 and GIP receptor expression by hyperglycemia: possible contribution to impaired incretin effects in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56(6):1551–1558. doi: 10.2337/db06-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajan S, Dickson LM, Mathew E, et al. Chronic hyperglycemia downregulates GLP-1 receptor signaling in pancreatic beta-cells via protein kinase A. Mol Metab. 2015;4(4):265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buitinga M, Cohrs CM, Eter WA, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of glycemia-induced regulation of GLP-1R expression in murine and human islets of langerhans. Diabetes. 2020;69(11):2246–2252. doi: 10.2337/db20-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell SA, Golec DP, Hubert M, et al. Human islets contain a subpopulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 secreting alpha cells that is increased in type 2 diabetes. Mol Metab. 2020;39:101014. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Souza AH, Tang J, Yadev AK, et al. Intra-islet GLP-1, but not CCK, is necessary for beta-cell function in mouse and human islets. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2823. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Virostko J, Williams J, Hilmes M, et al. Pancreas volume declines during the first year after diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and exhibits altered diffusion at disease onset. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(2):248–257. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velikyan I, Haack T, Bossart M, et al. First-in-class positron emission tomography tracer for the glucagon receptor. EJNMMI Res. 2019;9(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s13550-019-0482-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eriksson O, Velikyan I, Haack T, et al. Imaging of the glucagon receptor in subjects with type 2 diabetes. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2021;62(6):833–838. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.213306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krogvold L, Edwin B, Buanes T, et al. Pancreatic biopsy by minimal tail resection in live adult patients at the onset of type 1 diabetes: experiences from the DiViD study. Diabetologia. 2014;57(4):841–843. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3155-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah VN, Wu M, Polsky S, et al. Gender differences in diabetes self-care in adults with type 1 diabetes: Findings from the T1D exchange clinic registry. J Diabetes Complicat. 2018;32(10):961–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.