Abstract

Objectives. To evaluate the association between living alone and suicide and how it varies across sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods. A nationally representative sample of adults from the 2008 American Community Survey (n = 3 310 000) was followed through 2019 for mortality. Cox models estimated hazard ratios of suicide across living arrangements (living alone or with others) at the time of the survey. Total and sociodemographically stratified models compared hazards of suicide of people living alone to people living with others.

Results. Annual suicide rates per 100 000 person-years were 23.0 among adults living alone and 13.2 among adults living with others. The age-, sex-, and race/ethnicity-adjusted hazard ratio of suicide for living alone was 1.75 (95% confidence interval = 1.64, 1.87). Adjusted hazards of suicide associated with living alone varied across sociodemographic groups and were highest for adults with 4-year college degrees and annual incomes greater than $125 000 and lowest for Black individuals.

Conclusions. Living alone is a risk marker for suicide with the strongest associations for adults with the highest levels of income and education. Because these associations were not controlled for psychiatric disorders, they should be interpreted as noncausal. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(12):1774–1782. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307080)

Between 1960 and 2021, the percentage of single-person households in the United States increased from 13% to 28%.1 One-person households also account for more than a quarter of all households in many other high-income countries including France, England, Germany, Canada, Spain, and Japan.2 In light of the substantial number and rising proportion of adults who live alone, there is interest in understanding whether and to what extent living alone is associated with adverse health outcomes.

Several general population cohort studies have reported that living alone is connected with increased risk of all-cause mortality. In one review, the average increased risk of all-cause mortality for living alone (32%) was similar to the corresponding risks for social isolation (29%) and loneliness (26%).3 A recent meta-analysis reported that living alone is associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality for individuals aged younger than 65 years and may be more pronounced for males than females.4 Informed by social and psychological theories linking social isolation to suicide risk,5 several studies have specifically probed relationships between living alone and risk of suicide. Cohort studies of various high-risk populations including adults following nonfatal suicide attempts,6 people with disabilities attributable to mental disorders,7 adults with bipolar disorder,8 and people hospitalized for depression9 have all reported significant positive associations between living alone and suicide risk.

In general population samples, living alone has also been reported to be associated with increased risk of suicide. A German population-based cohort study reported that living alone was associated with increased risk of suicide (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.2) similar in magnitude to depressed mood (HR = 2.0).10 A large Finnish general population cohort study further reported that living alone was associated with increased relative suicide mortality rates for men and women who were working age (30–64 years) and older (≥ 65 years).11 A recent UK Biobank study, however, found that living alone was associated with an increased risk of suicide in men but not women.12 A study of older Korean adults that controlled for a wide range of sociodemographic, health, and behavioral health factors similarly found that living alone was related to suicidal ideation for men but not women.13 Some14,15 but not all16 case‒control studies have also reported significant associations between living alone and death by suicide.

Because of sample size limitations of previous research, little is known about whether and how the risk of suicide associated with living alone varies across sociodemographic groups beyond the apparent stronger association for men than women. The multiple pathways to living alone, which include relationship dissolution, death of a partner, and decisions not to enter into a cohabitation partnership, contribute to the heterogeneity of this population, and the mental health consequences of living alone could vary across this diverse group.

To better understand the association between living alone and suicide, we followed respondents to the 2008 American Community Survey (ACS) who were either living alone or with others for their risk of death by suicide. Stratified analyses assessed whether living alone varied as a risk marker for suicide across sociodemographic groups. Because the ACS does not include measures of common shared causes of living alone and suicide, such as mental health problems17,18 and substance misuse,19,20 we consider these associations as noncausal. Increasing our understanding of the strength and pattern of associations between living alone and suicide might inform risk assessment and future epidemiological research to evaluate the contribution of living alone to suicide risk.

METHODS

The study cohort was defined from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities21,22 sample that links 2008 ACS data to National Death Index underlying cause of death certificate records from 2008 to 2019 (n = 3 452 000) after exclusion of people for whom National Death Index linkage was not possible because social security numbers, names, and date of birth were unavailable. The complex sampling frame of the ACS was designed to approximate US population estimates by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and state of residence. Sampling weights were applied to account for variable sampling within demographic subgroups.

We analyzed respondents aged 18 years or older at the ACS interview, excluding those living in group quarters (n = 142 000) such as college dormitories, residential treatment centers, skilled nursing facilities, group homes, military barracks, or correctional facilities.

Living Alone

The number of persons in a household was defined as everyone currently living or staying at a sampled address, except those who have been or will be living at the address for 2 months or less. The study cohort was partitioned into 2 groups on the basis of their reported living circumstances: (1) adults living alone or (2) adults living with others including family and nonfamily. The living-alone variable was measured once in 2008.

Sociodemographics and Functional Disabilities

Respondent characteristics were collected at the time of the ACS survey. Sociodemographic characteristics included age in years, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, employment during past week, highest level of educational attainment, household annual income from all sources, urban (77%) or rural (23%) residence as defined by the Census,23 whether the respondent was a renter or owner, and residential stability based on how long the respondent had lived at their current residence (< 5 years, 5–10 years, > 10 years).

Respondents were also asked about 6 areas of serious difficulties including hearing; vision; concentrating, remembering, or making decisions; walking or climbing stairs; dressing or bathing; and independent living. Respondents who indicated 1 or more of these difficulties were coded as having “any functional disability.”

Outcome

National Death Index data indicated whether each Mortality Disparities in American Communities participant had died over the 11-year follow-up period from their ACS survey date. The outcome of primary interest was suicide (International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM; Second edition; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004] codes X60‒X84, Y87.0, U03)24 as the underlying cause of death.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis was performed in 3 stages. In the first stage, we used the χ2 difference in proportion test to compare the sociodemographic characteristics of adults who lived alone versus with others. In the second stage, we determined suicide rates per 100 000 person-years with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We also examined whether each sociodemographic characteristic moderated the strength of living alone as a risk marker for suicide. Because living alone25 and suicide26 both vary by age, sex, and race/ethnicity, we also treated these demographic characteristics as potential background confounders. Therefore, we used Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) of suicide with living alone as the independent variable of interest and living with others as the reference group.

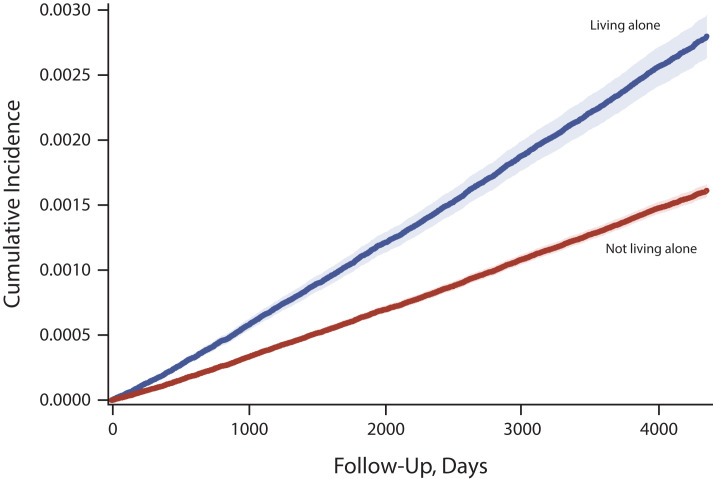

We measured event time continuously from the date of baseline survey administration until the date of suicide death, date of death from all causes other than suicide (censoring event), or December 31, 2019, for those who did not die (censoring event), whichever came first. A survival plot was generated to display cumulative suicide risks for respondents living alone and with others. In separate models, we entered interaction terms (e.g., age group × living situation) to test whether the effects of living situation on hazards of suicide differed across levels of the sociodemographic variables. Separate analyses partitioned suicide deaths by means into poisoning (ICD-10-CM: X60–X69), firearms (X72–X74), suffocation (X70), and other (X71, X75‒X84, Y87.0, U03).

In a sensitivity analysis, we limited follow-up to 1 year from ACS completion. In a second sensitivity analysis, we broadened the definition of mortality outcome to include suicide (ICD-10-CM: X60‒X84, Y87.0, U03) or injuries of undetermined intent (Y10‒Y34, Y87.2). We considered rates and AHRs with nonoverlapping 95% CIs or P value less than .05 to significantly differ.

We conducted analyses in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We weighted individual-level observations to account for nonequal probability of selection into ACS and to increase generalizability of the findings to the US adult population. Reporting followed the disclosure guidelines of the Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board.

RESULTS

Approximately 14.5% of the sample, including 16.3% of women and 12.6% of men, lived alone at the time of the survey. As compared with people who lived with others, those who lived alone were significantly older and were more likely to be female, to have White or Black race/ethnicity, to have a low income, to reside in more urban rather than the most rural areas, to rent rather than own their residence, and to have a functional disability. However, people who lived alone were less likely than those who lived with others to be employed or to be currently married (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Adults Who Live Alone or With Others: Mortality Disparities in American Communities, United States, 2008

| Characteristic | Adults Living Alone (n = 480 000), % (95% CI)a | Adults Living With Others (n = 2 830 000), % (95% CI)a |

| Age, y* | ||

| 18–39 | 22.9 (22.7, 23.0) | 41.8 (41.7, 41.9) |

| 40–64 | 43.4 (43.2, 43.5) | 44.4 (44.4, 44.5) |

| ≥ 65 | 33.8 (33.6, 34.0) | 13.8 (13.7, 13.8) |

| Sex* | ||

| Male | 44.2 (44.0, 44.3) | 49.0 (48.9, 49.1) |

| Female | 55.8 (55.7, 56.0) | 51.0 (50.9, 51.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 74.9 (74.8, 75.1) | 67.8 (67.7, 67.9) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 13.6 (13.5, 13.8) | 10.8 (10.8, 10.9) |

| Hispanic | 7.1 (7.0, 7.2) | 14.6 (14.5, 14.6) |

| Other | 4.4 (4.3, 4.5) | 6.8 (6.8, 6.8) |

| Marital status* | ||

| Married | 4.1 (4.0, 4.2) | 62.4 (62.3, 62.4) |

| Separated/divorced | 35.0 (34.8, 35.1) | 10.0 (9.9, 10.0) |

| Widowed | 25.6 (25.5, 25.8) | 3.1 (3.0, 3.1) |

| Never married | 35.3 (35.2, 35.5) | 24.6 (24.5, 24.7) |

| Employment* | ||

| Employed | 55.7 (55.6, 55.9) | 66.4 (66.3, 66.5) |

| Not employed, < 65 y | 14.9 (14.8, 15.0) | 22.1 (22.1, 22.2) |

| Not employed, ≥ 65 y | 29.4 (29.2, 29.5) | 11.5 (11.4, 11.5) |

| Education* | ||

| Less than high school | 14.5 (14.3, 14.6) | 15.0 (14.9, 15.0) |

| High school/GED | 27.5 (27.4, 27.7) | 28.7 (28.7, 28.8) |

| Some college/associate degree | 29.3 (29.2, 29.5) | 30.8 (30.7, 30.8) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 28.7 (28.5, 28.8) | 25.5 (25.5, 25.6) |

| Income,* $ | ||

| 0 to 40 000 (loss) | 67.1 (67.0, 67.3) | 26.2 (26.1, 26.2) |

| 40 001 to 75 000 | 22.0 (21.8, 22.1) | 30.1 (30.0, 30.2) |

| 75 001 to 125 000 | 7.8 (7.7, 7.8) | 26.1 (26.0, 26.1) |

| > 125 000 | 3.2 (3.1, 3.2) | 17.7 (17.6, 17.7) |

| Residence* | ||

| Urban | 82.1 (81.9, 82.2) | 75.7 (75.6, 75.7) |

| Rural | 17.9 (17.8, 18.1) | 24.3 (24.3, 24.4) |

| Housing finance* | ||

| Renter | 46.2 (46.0, 46.4) | 72.8 (72.7, 72.8) |

| Owner | 53.8 (53.6, 54.0) | 27.2 (27.2, 27.3) |

| Residential stability,* y | ||

| < 5 | 44.8 (44.6, 45.0) | 40.2 (40.2, 40.3) |

| 5–10 | 19.8 (19.7, 20.0) | 23.1 (23.0, 23.2) |

| > 10 | 35.4 (35.2, 35.5) | 36.7 (36.6, 36.7) |

| Functional disability | ||

| Any* | 25.1 (24.9, 25.2) | 12.8 (12.8, 12.9) |

| Hearing* | 7.8 (7.7, 7.9) | 3.8 (3.8, 3.9) |

| Vision* | 5.1 (5.0, 5.2) | 2.4 (2.4, 2.4) |

| Cognitive* | 7.6 (7.6, 7.7) | 4.4 (4.3, 4.4) |

| Walking* | 15.9 (15.8, 16.0) | 7.0 (7.0, 7.1) |

| Dressing* | 4.9 (4.8, 5.0) | 2.6 (2.5, 2.6) |

| Independent travel* | 9.9 (9.8, 10.0) | 4.8 (4.8, 4.9) |

Notes. CI = confidence interval; GED = general educational development. Limited to adults aged ≥ 18 years; excludes adults in group quarters.

Numbers rounded to 10 000s following Census guidelines. Disclosure Review Board approval number CBDRB-FY22-CES004-040.

P< .001.

Overall and Stratified Risk of Suicide

The overall annual rate of suicide per 100 000 person-years was nearly twice as high among people who lived alone compared with people living with others (23.0 vs 13.2; Table 2). Group differences in the cumulative risk of suicide during follow-up are displayed in Figure 1 (Wald χ2 = 268.3; P < .001). After we controlled for the potentially confounding effects of age, sex, and race/ethnicity, living alone was also associated with nearly 2-fold increased hazards of suicide in the total sample (AHR = 1.75; 95% CI = 1.64, 1.87). Across most strata examined, adults who lived alone had significantly higher hazards of suicide than people who lived with others. The 2 strongest associations of living alone with suicide risk were among adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher education (AHR = 2.25; 95% CI = 1.97, 2.56) and among adults with annual incomes of more than $125 000 (AHR = 2.22; 95% CI = 1.64, 3.00) while the 2 weakest corresponding associations were among non-Hispanic Black adults (AHR = 0.92; 95% CI = 0.63, 1.33) and among adults aged 18 to 39 years (AHR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.07, 1.41).

TABLE 2—

Suicide Risk of Adults Who Live Alone or With Others Stratified by Sociodemographic Characteristics: Mortality Disparities in American Communities, United States, 2008‒2019

| Characteristic | Suicide Rate per 100 000 Person-Years | AHRa of Suicide for Living Alone (95% CI) Reference, Living With Others | Interaction (P) | |

| Adults Living Alone (95% CI) | Adults Living With Others (95% CI) | |||

| Total | 23.0 (21.6, 24.4) | 13.2 (12.8, 13.6) | 1.75 (1.64, 1.87) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18–39 | 18.0 (15.7, 20.6) | 12.6 (12.0, 13.2) | 1.23 (1.07, 1.41) | Ref |

| 40–64 | 28.7 (26.5, 31.1) | 13.4 (12.8, 14.1) | 2.15 (1.96, 2.35) | < .001 |

| ≥ 65 | 17.9 (15.7, 20.4) | 14.7 (13.4, 16.0) | 1.97 (1.68, 2.31) | .001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 40.3 (37.6, 43.0) | 21.0 (20.3, 21.7) | 1.82 (1.69, 1.97) | .002 |

| Female | 8.9 (7.8, 10.1) | 5.8 (5.5, 6.2) | 1.69 (1.45, 1.97) | Ref |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 27.6 (25.9, 29.4) | 16.1 (15.6, 16.6) | 1.79 (1.67, 1.93) | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4.7 (3.2, 6.7) | 6.1 (5.3, 7.0) | 0.92 (0.63, 1.33) | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 14.2 (10.5, 18.7) | 6.4 (5.7, 7.1) | 2.20 (1.63, 2.96) | .26 |

| Other | 18.4 (13.1, 24.9) | 11.0 (9.6, 12.5) | 1.67 (1.20, 2.32) | .61 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 16.3 (11.2, 22.9) | 12.4 (11.9, 12.9) | 1.31 (0.93, 1.84) | .53 |

| Separated/divorced | 28.2 (25.8, 30.8) | 18.1(16.6, 19.6) | 1.28 (1.13, 1.46) | .15 |

| Widowed | 12.4 (10.4, 14.8) | 6.9 (5.2, 9.0) | 1.63 (1.15, 2.31) | .36 |

| Never married | 24.6 (22.4, 27.0) | 13.8 (13.0, 14.7) | 1.35 (1.20, 1.51) | Ref |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | 20.8 (19.2, 22.6) | 11.4 (11.0, 11.9) | 1.82 (1.67, 1.99) | Ref |

| Not employed, < 65 y | 38.2 (33.8, 43.0) | 17.9 (16.9, 18.9) | 1.74 (1.52, 1.98) | .61 |

| Not employed, ≥ 65 y | 18.6 (16.2, 21.4) | 15.3 (13.9, 16.8) | 1.93 (1.63, 2.29) | .47 |

| Education | ||||

| < high school | 22.1 (18.5, 26.1) | 14.0 (12.9, 15.1) | 1.77 (1.46, 2.16) | < .001 |

| High school/GED | 22.4 (19.9, 25.2) | 15.6 (14.8, 16.4) | 1.48 (1.30, 1.69) | < .001 |

| Some college/associate degree | 24.8 (22.3, 27.6) | 13.4 (12.6, 14.1) | 1.82 (1.61, 2.04) | .006 |

| ≥ bachelor’s degree or higher | 22.0 (19.6, 24.6) | 10.0 (9.4, 10.8) | 2.25 (1.97, 2.56) | Ref |

| Income, $ | ||||

| 0 to 40 000 (loss) | 23.1 (21.4, 24.9) | 15.4 (14.5, 16.3) | 1.38 (1.26, 1.52) | .014 |

| 40 001 to 75 000 | 23.0 (20.2, 26.0) | 13.4 (12.7, 14.2) | 1.55 (1.35, 1.77) | .07 |

| 75 001 to 125 000 | 19.8 (15.6, 24.6) | 12.2 (11.4, 12.9) | 1.45 (1.15, 1.83) | .05 |

| > 125 000 | 28.1 (20.5, 37.6) | 11.3 (10.4, 12.2) | 2.22 (1.64, 3.00) | Ref |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 30.0 (26.4, 34.0) | 16.3 (15.4, 17.2) | 1.73 (1.60, 1.87) | .59 |

| Rural | 21.4 (20.0, 23.0) | 12.2 (11.8, 12.7) | 1.89 (1.65, 2.17) | Ref |

| Housing finance | ||||

| Renter | 22.4 (20.4, 24.4) | 11.6 (10.9, 12.3) | 1.56 (1.40, 1.74) | .010 |

| Owner | 23.5 (21.6, 25.5) | 13.8 (13.4, 14.3) | 1.83 (1.67, 2.00) | Ref |

| Residential stability, y | ||||

| < 5 | 23.3 (21.3, 25.4) | 12.4 (11.8, 13.0) | 1.68 (1.52, 1.86) | Ref |

| 5–10 | 23.1 (20.2, 26.4) | 13.6 (12.8, 14.5) | 1.76 (1.52, 2.05) | .73 |

| > 10 | 22.4 (20.2, 24.9) | 13.8 (13.2, 14.6) | 1.92 (1.71, 2.17) | .41 |

| Functional disability | ||||

| Present | 30.4 (27.1, 34.1) | 25.5 (23.8, 27.2) | 1.49 (1.31, 1.71) | .001 |

| Absent | 21.0 (19.6, 22.5) | 11.7 (11.3, 12.1) | 1.77 (1.64, 1.91) | Ref |

Notes. AHR = adjusted hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; GED = general educational development. Limited to adults aged ≥ 18 years; excludes respondents living in group quarters. Respondents followed through 2019.

Adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Disclosure Review Board approval number CBDRB-FY22-CES004-040.

FIGURE 1—

Cumulative Suicide Risk of Adults Who Live Alone or With Others: Mortality Disparities in American Communities, United States, 2008‒2019

Notes. Analysis was limited to adults aged ≥ 18 years. Disclosure Review Board approval number CBDRB-FY22-CES004-043.

We observed significant variations in the adjusted hazards of suicide risk by age group, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, and functional disability status (Table 2). Specifically, the association between living alone and suicide was significantly stronger for older (AHR = 1.97; 95% CI = 1.68, 2.31) than younger (AHR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.07, 1.41) adults, men (AHR = 1.82; 95% CI = 1.69, 1.97) than women (AHR = 1.69; 95% CI = 1.45, 1.97), non-Hispanic White (AHR = 1.79; 95% CI = 1.67, 1.93) than non-Hispanic Black (AHR = 0.92; 95% CI = 0.63, 1.33) individuals, and people with a bachelor’s degree or higher education (AHR = 2.25; 95% CI = 1.97, 2.56) than for those whose with less than a high-school education (AHR = 1.77; 95% CI = 1.46, 2.16).

The association between living alone and suicide hazards was also stronger for people whose annual incomes exceeded $125 000 (AHR = 2.22; 95% CI = 1.64, 3.00) than for those with incomes below $40 000 (AHR = 1.38; 95% CI = 1.26,1.52). In addition, living alone was associated with significantly greater hazards of suicide for people living without functional disabilities (AHR = 1.77; 95% CI = 1.64, 1.91) than for those living with these disabilities (AHR = 1.49; 95% CI = 1.31, 1.71) as was the associations with owners (AHR = 1.83; 95% CI = 1.67, 2.00) than renters (AHR = 1.56; 95% CI = 1.40, 1.74). In sex-stratified analyses, there were several similarities between the associations among men and women (Tables A and B, available as supplements to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org). Among Hispanic adults, however, there was a significant association between living alone and suicide for men (AHR = 2.51; 95% CI = 1.84, 3.43) but not for women (AHR = 1.00; 95% CI = 0.36, 2.76).

In an analysis limited to 1-year follow-up after ACS completion, living alone was associated with increased hazards of suicide (AHR = 1.68; 95% CI = 1.39, 2.03; Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org) that were similar to the increase after the 11-year follow-up (AHR = 1.75; 95% CI = 1.64, 1.87; Table 2).

Risk of Suicide by Different Means

The adjusted hazards of suicide of living alone compared with living with others were higher for suicide by poisoning (AHR = 2.29; 95% CI = 1.97, 2.68) than by firearms (AHR = 1.69; 95% CI = 1.54, 1.85), suffocation (AHR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.29, 1.78), or other means (AHR = 1.75; 95% CI = 1.64, 1.88; Table D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org).

Risk of Undetermined Intent Deaths

Broadening the outcome to suicide or undetermined intent injury deaths yielded rates per 100 000 person-years of 25.3 for adults living alone and 14.7 for adults living with others with an AHR of 1.74 (95% CI = 1.63, 1.85; Table E, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org). The pattern of results with this broader outcome resembled the pattern with suicide as the outcome (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this large, nationally representative cohort of US adults, living alone emerged as a significant risk marker for suicide. The strength of the association in the total adult population, which increased by 75% the hazards of suicide after controlling for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, was in line with previous epidemiological research from outside the United States.10–12 Living alone was significantly associated with suicide mortality separately for men and women. There was significant variation across sociodemographic groups in the adjusted strength of the associations between living alone and suicide with the 2 strongest associations occurring among adults with the highest levels of income and education.

Because the present study did not control for psychiatric morbidity or substance use, which are related to living alone and suicide, the associations should be interpreted as noncausal. However, previous research on this topic, which controlled for different aspects of psychiatric morbidity or substance use, suggests living alone contributes to suicide risk. In a general population study, which controlled for baseline depressed mood, alcohol intake, and several other factors, living alone was associated with increased suicide risk (HR = 2.19; 95% CI = 1.09, 4.37).10 A case‒control study that matched on background demographic characteristics and controlled for psychiatric pathology further reported a significant association between living alone and suicide (odds ratio = 2.30; 95% CI = 1.36, 5.75).14 Significant associations between living alone and suicide have also been reported in cohort studies restricted to individuals with psychiatric disorders7–9 or following nonfatal intentional poisonings.6

Comparing the background characteristics of adults who lived either alone or with others suggests that living alone is related to a set of socioeconomic and functional vulnerabilities. In relation to those living with others, people who lived alone were far more likely to have low (or negative) incomes. Consistent with previous research,27 people living by themselves were also significantly more likely than those living with others to have functional disabilities. The group who lived alone was also substantially older than those who cohabited. Not surprisingly, people living alone also included a disproportionately large number of individuals who had never married, were widowed, or were separated or divorced. These patterns likely reflect demographic, psychological, social, and economic factors involved in selection into different living arrangements over the adult lifespan.

Selection and direct causal mechanisms may contribute to the increased suicide risks of adults who live alone. Selection operates through factors that are causally related to living alone and suicide risk. As an example, suicide risk is elevated in the aftermath of divorce and separation,28 and these transitions also typically result in changes in living arrangements. Because living alone was associated with modest increased risk of suicide among separated or divorced adults in the present report, factors other than living alone such as stress related to separation or divorce29 or the association of common psychiatric disorders with separation and divorce30 might also contribute to the elevated risk of suicide among separated or divorced adults.28,31 The role of selection versus direct mechanisms related to loneliness and social isolation in suicide risk remains unknown. However, the high fraction of adults who live alone that are divorced or separated (34.9%) likely contributes to the high crude rate of suicide among people who live alone.

While beyond the scope of the current analysis, the experience of living alone may also increase suicide risk. In epidemiological research, living alone has been consistently related to a substantially elevated risk of loneliness,32 and loneliness has been related to suicidal behavior.33 Without a measure of loneliness in the present study, however, we were unable to assess the extent to which loneliness, social isolation, other psychological factors, less opportunity for rescue from a suicide attempt, or other factors related to living alone mediate the observed association of living alone with suicide risk.

Although the current study is not intended to evaluate causal connections between living alone and suicide risk, the findings are consistent with a long tradition of sociological research on suicide that has emphasized social disengagement and loss of regulation, related to declining oversight and guidance from social ties.34 These concepts have their historical roots in Durkheim’s insights more than a century ago on the stability of well-integrated groups with cohesive and durable social ties.35 In the current study, living alone was especially strongly related to suicide by poisoning. When poisoning events occur among people who live alone, there may be fewer opportunities for another individual to intercede with a potentially life-saving intervention such as activating the emergency medical services response system.

The current findings suggest that, as a marker of suicide risk, living alone operates differentially across age, sex, ethnic/racial, and educational groups in the United States and underscores opportunities for future research to probe the basis of these variations. For example, the reasons that living alone was not a risk marker for suicide for non-Hispanic Black adults, a group with comparatively low but increasing suicide risk, offers opportunities for research on culturally mediated protective mechanisms. It is possible that strong familial connections among non-Hispanic Black individuals helped to buffer the connection between living alone and suicide risk in this group.36,37

Limitations

This analysis had several limitations. First, living arrangements and the other baseline respondent characteristics, especially employment and income, may have changed during follow-up in ways that altered the overall association between living alone and suicide risk and affected its moderation by the sociodemographic characteristics. Although less is known about the stability of living arrangements among younger adults, approximately 81% to 88% of surviving older adults who lived alone at baseline in 2 cohort studies were reported to continue to live alone at 5-year follow-up.38,39 In the ACS cohort, the 1-year and 11-year follow-up analyses of living alone and suicide risk yielded similar results.

Second, death certificate data may not accurately capture suicide, although suicide in death certificates has been found to have a sensitivity of 90% with information from hospital, autopsy, law enforcement, and medical examiner records as the criterion standard.40

Third, because the ACS does not measure important suicide risk factors such as mental health and substance use disorders,18 previous suicide attempts,41 or stressful life events42 that may also be related to living alone,17,19 the associations between living arrangements and suicide risk should be interpreted as noncausal.

Fourth, the cohort was either not sufficiently large or did not include measures of several other groups with increased rates of suicide including survivors of critical illnesses43 or individuals who identify as Native Americans44 or as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer or questioning.45 Finally, the group who lived with others includes a diverse set of living arrangements that may vary in their associations with suicide risk.46

Public Health Implications

The current findings have implications for clinical practice and future epidemiological research. In contrast to loneliness, which is difficult for primary care clinicians to identify in their patients,47 living alone is a readily discernible personal characteristic. In addition to traditional suicide risk factors, such as depression, substance use, and previous suicidal behavior, clinical consideration might also be given to living circumstances as a risk marker to consider in the context of known suicide risk factors.

The findings might also help inform future research aimed at understanding why the increase in suicide risk among people who live alone varies across sociodemographic characteristics. In this regard, longitudinal designs, which permit probing how transitions in housing arrangements covary with known risk factors for suicide, such as social isolation or depressed mood, might help to elucidate causal mechanisms that contribute to sociodemographic variation in the strength of associations between living alone and death by suicide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Institute on Aging interagency agreements with the US Census Bureau.

Note. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Drug Abuse; or the US Census Bureau.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The results were reviewed and approved for release by the US Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board (DRB) to prevent disclosure of confidential information: DRB releases CBDRB-FY22-CES004-040, CBDRB-FY22-CES004-041, and CBDRB-FY22-CES004-043.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Census Bureau. Census Bureau releases new estimates on America’s families and living arrangements. 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2019/comm/one-person-households.html

- 2.Klinenberg E. Social isolation, loneliness, and living alone: identifying the risks for public health. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):786–787. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Guyatt G, Gao Y, et al. Living alone and all-cause mortality in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;54:101677. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calati R, Ferrari C, Brittner M, et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: a narrative review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:653–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordentoft M, Breum L, Munck LK, et al. High mortality by natural and unnatural causes: a 10 year follow-up study of patients admitted to a poisoning treatment centre after suicide attempts. BMJ. 1993;306(6893):1637–1641. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6893.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman S, Alexanderson K, Jokinen J, Mittendorder-Rutz E. Risk factors for suicidal behavior in individuals on disability pension due to common mental disorders: a nationwide register-based prospective cohort study in Sweden. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson C, Joas E, Palsson E, et al. Risk factors for suicide in bipolar disorder: a cohort study of 12,850 patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):456–463. doi: 10.1111/acps.12946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aaltonen KI, Isometsa E, Sund R, Pirkola S. Risk factors for suicide in depression in Finland: first-hospitalized patients followed up to 24 years. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139(2):154–163. doi: 10.1111/acps.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider B, Lukaschek K, Baumert J, Meisinger C, Erazo N, Ladwig KH. Living alone, obesity, and smoking increase risk for suicide independently of depressive mood findings from the population-based MONICA/KORA Augsburg cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2014;152-154:416–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koskinen S, Joutsenniemi K, Martelin T, Martikainen P. Mortality differences according to living arrangements. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(6):1255–1264. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw RJ, Cullen B, Graham N, et al. Living alone, loneliness, and lack of emotional support as predictors of suicide and self-harm: a nine year follow-up of the UK Biobank cohort. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju YJ, Park EC, Han KT, et al. Low socioeconomic status and suicidal ideation among elderly individuals. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(12):2055–2066. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martiello MA, Boncompagni G, Lacangellera D, Corlito G. Risk factors for suicide in rural Italy: a case‒control study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(5):607–616. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giupponi G, Innamorati M, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Factors associated with suicide: case‒control study in South Tyrol. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;80:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almasi K, Belso N, Kapur N, et al. Risk factors for suicide in Hungary: a case‒control study. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacob L, Haro M, Koyanagi A. Relationship between living alone and common mental disorders in the 1993, 2000 and 2007 National Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys. PLoS ONE. 14(5):e0215182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS, Ignacia R, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1152–1158. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amundsen EJ, Bretteville-Jensen AL, Rossow I. Patients admitted to treatment for substance use disorder in Norway: a population-based case–control study of socio-demographic correlates and comparative analyses across substance use disorders. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):792. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13199-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivaraman JJC, Greene SB, Naumann RB, et al. Association between medical diagnoses and suicide in a Medicaid beneficiary population, North Carolina, 2014‒2017. Epidemiology. 2022;33(2):237–245. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Census Bureau. Mortality Disparities in American Communities (MDAC) 2022. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/about/about-the-bureau/adrm/MDAC/MDAC%20Reference%20Manual%20V1_6_21_17.pdf

- 22.US Census Bureau. Mortality Disparities in American Communities (MDAC). Available at. 2022. https://www.census.gov/topics/research/mdac.html

- 23.Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, Fields A. Defining rural at the US Census Bureau. ACSGEO-1. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian B, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(5):1–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vespa J, Lewis JM, Kreider RM.2022. http://171.67.100.116/courses/2016/ph240/wang1/docs/p20-570.pdf

- 26.Martínez-Alés G, Jiang T, Keyes KM, Gradus JL. The recent rise of suicide mortality in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43(1):99–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-051920-123206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henning-Smith C, Shippee T, Capistrant B. Later-life disability in environmental context: why living arrangements matter. Gerontologist. 2018;58(5):853–862. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fjeldsted R, Teasdale TW, Jensen M, Erlangsen A. Suicide in relation to the experience of stressful life events: a population-based study. Arch Suicide Res. 2017;21(4):544–555. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1259596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Scheppingen MA, Leopold T. Trajectories of life satisfaction before, upon, and after divorce: evidence from a new matching approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2020;119(6):1444–1458. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mojtabai R, Stuart EA, Hwang I, Eaton WW, Sampson N, Kessler RC. Long-term effects of mental disorders on marital outcomes in the National Comorbidity Survey ten-year follow-up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(10):1217–1226. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1373-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kposowa AJ. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(4):254–261. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.4.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franssen T, Stijnen M, Hamers F, Schneider F. Age differences in demographic, social and health-related factors associated with loneliness across the adult life span (19‒65 years): a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1118. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09208-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stravynski A, Boyer R. Loneliness in relation to suicide ideation and parasuicide: a population-wide study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(1):32–40. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.32.21312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wray M, Colen C, Pescosolido B. The sociology of suicide. Annu Rev Sociol. 2011;37(1):505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durkheim E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. London, England: Routledge; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Compton MT, Thompson NJ, Kaslow NJ. Social environment factors associated with suicide attempt among low-income African Americans: the protective role of family relationships and social support. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(3):175–185. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Taylor HO, Lincoln KD, Mitchell UA. Extended family and friendship support and suicidality among African Americans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(3):299–309. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1309-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang J, Brown JW, Krause NM, Ofstedal MB, Bennett J. Health and living arrangements of older Americans; does marriage matter? J Aging Health. 2005;17(3):305–335. doi: 10.1177/0898264305276300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martikainen P, Nihtila E, Moustgaard H. The effects of socioeconomic status and health on transitions in living arrangements and mortality: a longitudinal analysis of elderly Finnish men and women from 1997 to 2002. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63(2):S99–S109. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.2.S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moyer LA, Boyle CA, Pollock DA. Validity of death certificate certificates for injury related causes of death. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130(5):1024–1032. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawton K, Bergen H, Cooper J, et al. Suicide following self-harm: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-Harm in England, 2000‒2012. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oquendo MA, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Pol E, et al. Life events: a complex role in the timing of suicidal behavior among depressed patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(8):902–909. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernando SM, Qureshi D, Sood MM, et al. Suicide and self-harm in adult survivors of critical illness: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2021;373(973):n973. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olfson M, Cosgrove C, Altekruse SF, Wall MM, Blanco C. Deaths of despair: adults at high risk for death by suicide, poisoning, or chronic liver disease in the US. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(3):505–512. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lynch KE, Gatsby E, Viernes B, et al. Evaluation of suicide mortality among sexual minority US veterans from 2000 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2031357. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poudel-Tandukar K, Nanri A, Mizoue T, et al. Differences in suicide risk according to living arrangements in Japanese men and women—the Japan Public Health Center-based (JPHC) prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2011;131(1-3):113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Due TD, Sandholdt H, Siersma D, Waldroff FB. How well do general practitioners know their elderly patients’ social relations and feelings of loneliness? BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0721-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]