The case Herein we share our experience with a 70-year-old woman who was hospitalized in our intensive care unit (ICU) for SARS-CoV-2-related acute respiratory distress syndrome complicated by ventilator-acquired pneumonia, with septic shock and anuric acute kidney injury requiring continuous veno-venous hemodialysis (CVVHD). Standard of care for Covid pneumonia includes dexamethasone 6 mg per day, which we associated with ivermectine 15 mg monodose on Day 1 (D1) as a prevention for parasitosis under corticosteroids. Her eosinophil count was < 500/mm3 at ICU admission, thus she developed hypereosinophilia (> 1.5 × 103/mm3) at Day 68, which increased to 6.7 × 103/mm3 at Day 78.

The patient was treated with albendazole for 10 days as a test treatment in the hypothesis of a parasitic cause and a diagnostic work-up of hypereosinophilia was carried out: no evidence was found for hemopathy or cancer, vasculitis (negative autoimmune screening), drug hypersensitivity, viral infection (HSV 1/2, CMV, EBV, VZV, HHV-6, HHV-8, parvovirus B19 viral negatives PCRs), nor for parasitic infection (serology for toxocariasis, filariasis, anguillosis, trichinellosis and hydatidosis were all negative).

The onset of hypereosinophilia was observed 3 days after the first intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) session which replaced CVVHD. After each IHD session, hypereosinophilia worsened (Fig. 1), reaching a peak level of 6.7 × 103/mm3. No systemic manifestations consistent with hypersensitivity occurred during the hemodialysis sessions, and no organ damage resulting from hypereosinophilia was detected in the ICU. Following the aforementioned work–up, we reviewed the course of the eosinophil count in the ICU on the basis of the dialysis sessions, and observed a correlation with the exposure to dialysis membranes (FX100 Fresenius Helixone). Our consultant nephrologist established the diagnosis. We did not test another membrane as the kidney function of the patient enabled to withdraw dialysis sessions by day 85. The complete resolution of hyper-eosinophilia occurred as kidney function recovered, enabling to stop dialysis membrane exposure.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of the eosinophil blood count in parallel with urea rate and intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) sessions. IHD sessions are represented by plain arrows. The IHD sessions followed by major hypereosinophilia shown

Hypereosinophilia gradually resolved as kidney function recovered, allowing for weaning from IHD and thereby adding further support to the hypothesis of dialysis membrane-related hypersensitivity.

Lessons for the clinical nephrologist

Eosinophilia is not a rare event in patients requiring hemodialysis, and has been described since the 70s [1, 2], either isolated or associated with minor symptoms such as abdominal pain or moderate hypotension during dialysis sessions. These clinical manifestations have been indiscriminately clustered as “reaction to dialyzer membrane materials” [3]. Some rare cases of major hypereosinophilia presenting as part of a so-called allergy to hemodialysis material have been reported in the last decades in the chronic dialysis setting [3, 4].

Multiple components of the extra corporeal circuit (dialysis membrane, catheters, dialysate, etc.) have been implicated in the occurrence of eosinophilia [5, 6]. Chapelet-Debout et al. recently reported 6 cases of major hypereosinophilia attributed to the tunneled central venous catheter [6], but in our case, the catheter was not tunneled and consisted in a classical percutaneous double lumen dialysis catheter used in intensive care units in emergency dialysis settings. The dialysate was also taken into consideration in our etiologic investigation, but in our ICU we have a central water treatment system integrated into the dialysis loop, and the purified osmosis water is tested monthly. During our patient’s ICU stay, bacterial cultures were < 100 UFC/ml, and testing for endotoxins was < 0.25 UI/ml, as required. Moreover, at the time of our diagnosis, no other patient undergoing dialysis from this loop developed any adverse effects, including eosinophilia (approximately 40 patients were treated during the time interval of our patient’s stay). Yet, the onset of eosinophilia 3 days after implementation of IHD and 20 days after the patient was started on CVVHD pointed to the dialyzer membrane as the culprit since eosinophilia typically develops within a couple of days following exposure to the dialysis membrane.

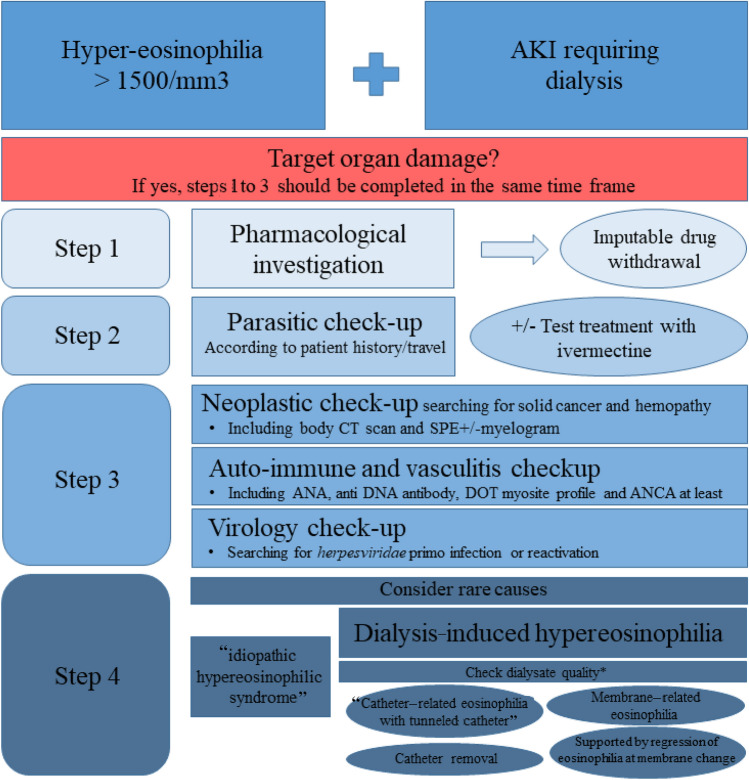

In the era of modified cellulose or synthetic membranes, as used in our ICU, severe symptomatic allergic reactions are infrequent. Thus, in recent years, hypereosinophilia (> 1.109 G/L) has been reported in an estimated 5% of patients on chronic hemodialysis [5]. It is therefore important, in the case of hypereosinophilia in a patient undergoing dialysis, to have an exhaustive, step-by-step, etiological diagnostic approach before blaming the dialysis equipment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proposed step-by-step etiological approach for hypereosinophilia in a dialysis setting. AKI acute kidney injury, ANA antinuclear antibody, ANCA anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, CT computed tomography, DRESS drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, IHD intermittent hemodialysis, SPE serum protein electrophoresis. *Osmosis water with bacterial cultures < 100 UFC/ml, and testing for endotoxins < 0.25 UI/ml regularly checked

Treatment with ACE-inhibitors is the major known factor associated with hypereosinophilia in this setting [5], potentially due to enhanced bradykinin release during allergic episodes, but our patient never received any.

The pathophysiology of hypereosinophilia and allergic reaction related to the hemodialysis circuit is unclear, although cytokine release following eosinophil activation by the membrane components has been hypothesized [7]. Direct and alternative complement pathways might also be involved, with C3a and C5a fractions potentially participating in eosinophil activation [8]. In the setting of long-term hemodialysis patients, resolution of eosinophilia has been achieved through treatment with systemic corticosteroids (0.5–1 mg/kg) and/or changing the membrane [9]. In our case, immunosuppression induced by the prolonged ICU stay, the absence of vital organ damage and the gradual but consistent resolution of eosinophilia following dialysis weaning discouraged us from using corticosteroids.

Hypereosinophilia linked to dialyzer membrane should be taken into consideration when dealing with critically ill patients after all competing causes have been carefully ruled out.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Consent to publication

The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Agarwal R, Light RP. Patterns and prognostic value of total and differential leukocyte count in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2011;6:1393–1399. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10521110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higuchi T, Yamazaki T, Ohnishi Y, et al. A case report of hemodialysis intolerance with eosinophilia. Ther Apher Dial Off Peer-Rev J Int Soc Apher Jpn Soc Apher Jpn Soc Dial Ther. 2007;11:70–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2007.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Röckel A, Klinke B, Hertel J, et al. Allergy to dialysis materials. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc Eur Ren Assoc. 1989;4:646–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanda E, Kida Y, Suzuki H, et al. Role of cytokines in anaphylactoid reaction with marked eosinophilia in a hemodialysis patient. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2004;8:384–387. doi: 10.1007/s10157-004-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildebrand S, Corbett R, Duncan N, Ashby D. Increased prevalence of eosinophilia in a hemodialysis population: longitudinal and case control studies. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2016;20:414–420. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapelet-Debout A, Coupel S, de Geyer DG, et al. Eosinophilia due to central venous catheter in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:1189–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertel J, Kimmel PL, Phillips TM, Bosch JP. Eosinophilia and cellular cytokine responsiveness in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 1992;3:1244–1252. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V361244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakim RM, Breillatt J, Lazarus JM, Port FK. Complement activation and hypersensitivity reactions to dialysis membranes. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:878–882. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410043111403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutsuyoshi Y, Hirai K, Morino J, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome in hemodialysis patients: case reports. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e25164. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]