Abstract

Introduction

Although previously regarded as a children’s disease, it is clear that atopic dermatitis (AD) is also highly prevalent in adults. Because AD is not associated with mortality, it is usually neglected compared with other, fatal diseases. However, several studies have highlighted that AD burden is significant due to its substantial humanistic burden and psychosocial effects. This study aims to summarize and quantify the clinical, economic, and humanistic burden of AD in adults and adolescents.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), EconPapers, The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). Studies were included if they reported clinical, economic, or humanistic effects of AD on adults or adolescents, from January 2011 to December 2020. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment tool was used to assess risk of bias for the included studies. Regression models were used to explain the correlation between factors such as disease severity and quality of life (QoL).

Results

Among 3400 identified records, 233 studies were included. Itch, depression, sleep disturbance, and anxiety were the most frequently reported parameters related to the clinical and humanistic burden of AD. The average utility value in studies not stratifying patients by severity was 0.779. The average direct cost of AD was 4411 USD, while the average indirect cost was 9068 USD annually.

Conclusions

The burden of AD is significant. The hidden disease burden is reflected in its high indirect costs and the psychological effect on QoL. The magnitude of the burden is affected by the severity level. The main limitation of this study is the heterogeneity of different studies in terms of data reporting, which led to the exclusion of potentially relevant data points from the summary statistics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-022-00819-6.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Atopic eczema, Burden of disease, Clinical burden, Dermatology, Economic burden, Humanistic burden, Systematic literature review

Plain Language Summary

Atopic dermatitis is a very common skin disease among children and adults. The disease is nonfatal but may lead to patients and families having a low quality of life and decreased productivity, especially in its severe state. Because atopic dermatitis is more common in children than adults, most published research is directed to studying the effect of the disease on children. Atopic dermatitis affects patients’ health, quality of life, financial state, and productivity. Therefore, our study aims to study and quantify the burden caused by the disease represented in the clinical burden, humanistic burden, and economic burden. We conducted a systematic literature review to determine all relevant studies providing specific values for the burden. The studies included are those providing information on the percentage of patients affected by specific symptoms, costs paid for treatment, number of days of productivity lost due to the disease, and quality-of-life questionnaire results for patients with atopic dermatitis or their caregivers. We analyzed the data from all relevant studies to calculate average values and quantify the burden. The results of our study should help healthcare sector decision-makers in understanding the real effect of the disease on adults and adolescents and rearrange their priorities for treating different diseases based on the specific burden of each disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-022-00819-6.

Key Summary Points

| The burden of atopic dermatitis is significant, mainly owing to its high prevalence. |

| Itch, depression, sleep disturbance, and anxiety are the most common manifestations among atopic dermatitis patients. |

| Managing each atopic dermatitis patient costs about 4411 USD annually. |

| Indirect costs (productivity lost costs) of atopic dermatitis represent more than double its direct costs. |

| The quality of life of patients with atopic dermatitis is significantly affected by the disease, but the effect is largely dependent on the severity level. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a nonfatal disease that significantly impairs patients’ quality of life (QoL). According to the global burden of disease study, AD has the highest disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) burden among all skin diseases. Its burden is ranked in the top 15 among all nonfatal diseases, and it is responsible for 0.36% of the total DALY burden of all 359 diseases and injuries analyzed in the study [1]. Compared with other dermatological diseases, AD poses a significantly higher burden. The age-standardized DALY rate of AD is 75% higher compared with psoriasis and 82% compared with urticaria, representing more than twice the burden of any other skin disease [1].

AD is also known as atopic eczema [2] and is a chronic disease that causes painful flares of inflamed, dry, and itchy skin periodically. Patients with AD usually have accompanying allergic disease, such as asthma or hay fever. To date, no cure has been found for AD, but treatments and self-care measures can relieve itching and prevent new outbreaks significantly [3].

Patients with moderate to severe AD often experience flares that negatively affect their productivity at work or school [4]. A cross-sectional study in Iran reported that 50% of dermatology patients suffered from psychiatric comorbidities as well [5]. An international study reported that 32% of participants believed that AD affected their school or work life, and 14% of participating adults believed that their career progression had been hindered by AD [4].

The prevalence of AD started to increase in the last decades of the twentieth century [6], with a prevalence up to 10–20% in children. Although AD had been regarded as a children’s disease, it has become clear that many adults also are affected, with an estimated prevalence of 3–5% in the general population [7].

Estimating the burden of AD on the basis of scientific evidence can help decision-makers make more informed treatment decisions. Understanding the burden of AD may also support public health policies, help to prioritize interventions, and allow for better resource allocation [8]. AD is a nonfatal disease and therefore usually neglected compared with more severe or fatal diseases. However, several studies have highlighted that the burden of AD is significant because of the substantial humanistic burden and psychosocial effects it can cause [9–11].

The aim of this systematic review is to summarize and quantify the clinical, economic, and humanistic burden of AD in adults and adolescents.

Methods

Databases and Literature Search Strategy

We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) and reported its results according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting SLRs [12]. We searched PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane library, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), and EconPapers for relevant studies. Additionally, grey literature sources were searched, including The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) scientific presentations database, and websites of health technology assessment agencies [The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH)]. The search terms were constructed based on two domains: “Atopic dermatitis “and “Burden of disease.” To identify suitable keywords for the search term, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, Google search, and previous papers on the same topic were used as guidance. These helped to identify relevant search terms and their thesaurus.

We included studies that evaluated any type of burden related to AD. Because the burden of disease is dependent on factors such as prevalence and available treatment options, which vary significantly within 10 years, the literature search was limited to studies published since January 2011. The search was restricted to English-language papers. Although our review focused on adults and adolescents, no age restriction was applied during the literature search to avoid missing potentially relevant studies that were not labeled as containing data for a specific age group. Instead, studies not reporting any data on patients older than 10 years were excluded during the screening and full-text review phases. The detailed search strategy is described in Supplementary Table S1.

Owing to the overlap between databases, search results were first de-duplicated using the embedded feature of EndNote software version X9. Additional duplicates were manually identified and excluded during the screening phase. The snowballing technique was used to add relevant studies from the references cited in the papers found during the SLR. In case of eligibility, the pool of included papers was extended.

Title and Abstract Screening

Studies identified during the literature search were screened by two independent researchers through title and abstract screening. Disagreements were resolved by a third principal researcher. As a first step, the titles and abstracts of all studies were screened using the following predefined exclusion criteria: (1) duplicates, (2) no English abstract, (3) published before 1 January 2011, (4) letters, editorial, case reports, nonsystematic reviews, or animal studies, (5) not related to AD or eczema, (6) not reporting data for patients 10 years or older, and (7) not evaluating the clinical, economic, or humanistic burden of AD (e.g., those investigating treatment efficacy).

Full-Text Screening and Data Extraction

Studies that were eligible for inclusion from the title and abstract screening phase were downloaded, and their full texts were screened. The same previously mentioned exclusion criteria were used, in addition to excluding inaccessible studies and studies with experimental study designs (e.g., clinical trials) because they do not reflect the real-life burden. Other reasons for exclusion were studies in which AD was a comorbidity with other diseases [13] or if there was a confounding effect of a drug other than the usual treatment [14]. In these cases, the burden reported was not solely dependent on AD.

For the included studies, data were extracted in Microsoft Excel. Extracted data were validated by another independent researcher. The general information extracted included number of patients, average age, sex distribution, type of study, and most importantly, whether the study included information about any of the four domains: QoL scoring, humanistic burden other than QoL score, clinical burden, and economic burden. The included studies had data about at least one of the four domains. Risk-of-bias assessment of the studies was performed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment (GRADE) tool [15]. Each study was assessed for risk of bias by one researcher and revised by another. In case of disagreement, the two researchers discussed to reach a valid decision. A summary of the quality assessment results is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Because of the heterogeneity of the data collected, each domain was extracted in a separate Microsoft Excel sheet. In the clinical and humanistic burden sheets, data were extracted based on the conceptual model developed by Grant et al. [16] to illustrate the clinical and humanistic burden associated with AD in adults and adolescents. Data about signs and symptoms, as well as psychological impact and health-related QoL (HRQoL) impact, were extracted as “mentioned” or “not mentioned.” The number of unique studies reporting the specific impact as part of the results was calculated. In case a clinical questionnaire or assessment tool was used, details were extracted in a multirow format, including subgroup details. Similarly, QoL questionnaire results were extracted. The economic data reported were also extracted in a multirow format, including data about costs, healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), and productivity lost.

Grant et al. [16] categorized the impact of AD as signs, symptoms, mediating factors, proximal impact, and distal HRQoL impact. We adapted the model by recategorizing the same domains under clinical and humanistic burden. Based on the adapted model, clinical burden subgroups were considered to cover psychological impact, signs, and symptoms: (1) psychological impact (depression, anxiety, stress, suicidal ideation, other psychological manifestation), (2) signs (itch or pruritis, burning or heat or tingling sensation, skin sensitivity/sensitivity to sun, soreness/pain/tenderness, skin irritation, skin tightness), and (3) symptoms [redness (erythema), dryness (xerosis), bumps/blisters/papules/vesicles, hardening/flaking, cracking/fissuring, scaling/peeling, thickening/lichenification, bleeding, edema/swelling, other symptoms]. Psychological impact parameters were extracted in both clinical and humanistic burden because they were noted to affect both domains in the studies.

The humanistic burden subgroups included (1) mediating factors (scratching, skin picking), (2) proximal impact (sleep disturbance, lack of concentration, bodily/physical discomfort), (3) distal HRQoL impact (limitation in daily activity, psychological impact, physical limitation, limitation in social/leisure activities, limitation in role: work, limitation in role: school, problems with interpersonal relationships, problems with sexual functioning, suboptimal skin-related health perceptions/cognition, financial burden associated with buying special products), and (4) other humanistic burden manifestations.

Data Processing and Analysis

Simple statistics were obtained from the extracted data, including average number of patients, average study duration, type of data sources, and average age of patients. Frequency of articles by region and income groups was calculated based on the World Bank classification (June 2019 update) [17].

The frequency of mentions of the humanistic and clinical impact is reported, and the details of the clinical burden are narratively summarized. Further in-depth analysis was conducted for QoL and economic data. For this purpose, each type of data underwent processing as elaborated below.

Disease Severity

Reporting of disease severity in different studies was heterogeneous and used different terminologies that hindered the ability to assess severity as an independent variable, so severity ranks from different publications were transformed into an ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 5, where a higher value indicates higher severity. In case a study featured only two severity groups, the less severe group was labeled 2 and the more severe group was labeled 4, while if the study mentioned three subgroups, the subgroups were labeled 2, 3, and 4. In case of four severity groups the labels were 1, 2, 4, and 5, while in the case of five severity subgroups, the groups were labeled from 1 to 5. Studies reporting the whole population without specifying severity levels were excluded from the ordinal scale and labeled as “unstratified population.”

Economic Data

Economic data were converted to annual cost per patient values when possible. For studies reporting the time horizon as lifetime, the estimated life expectancy of patients was used (average age of death of AD patients − average age at onset) [18, 19]. Furthermore, for cost data, values were adjusted to inflation using the consumer price index (CPI) for 2020 from the World Bank database. If CPI values for the year 2020 were not available, the most recently reported values were used instead [20]. If more than one country was included explicitly in the study, the average CPI of all included countries was used. The CPI for Taiwan was not available, so it was obtained from an external source [21]. Next, values were converted to 2020 USD using the official exchange rate from the World Bank database [22].

QoL Data

Studies measured QoL using different questionnaires or scales. We unified QoL results into one unit to allow for aggregation of results and comparison. Utility values have reference points of 0 and 1, where 0 indicates death and 1 indicates perfect health. The European QoL Five Dimension (EQ-5D) index questionnaire is the QoL questionnaire that provides values on a utility scale, so the QoL values identified using other scales were transformed (i.e., mapped) to EQ-5D index values when possible.

Studies using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (cDLQI) questionnaire results were transformed to the EQ-5D index using an online transformation tool [23] To transform EQ-5D Visual Analog Scale (VAS) values, there was no available tool, so we used a custom-made function based on linear regression in patients with AD.

To conduct the linear regression, we used all studies identified in our SLR that included both EQ-5D VAS and EQ-5D index values for the same AD patient subgroups. We identified five studies that included these values [24–28]. The data points in these studies were run through a linear regression model using the least-squares method.

The following linear regression equation was used to convert EQ-5D VAS QoL scores to EQ-5D index values on a scale from 0 to 1:

y: EQ-5D VAS QoL score, x: EQ-5D index QoL value.

Productivity Lost

Similarly, productivity lost was reported either as the number of days or hours lost during a certain period, or as a percentage lost in some cases. All values were unified to number of days lost annually per patient by using the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average working hours per year value of 1726 and assuming eight working hours per day [29].

Multiple Regression

Several multiple linear regression models were developed using IBM SPSS statistics software version 25 to determine the main drivers for economic costs and QoL of AD. Economic costs in USD were used as the outcome of one model, while QoL in utility score was used as the outcome of the other model. Different numeric and nominal variables were used as the main predictors (e.g., male percentage, age, severity score). Only clinically and statistically significant models are presented in the results.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study is based on previously conducted research and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

The systematic search yielded 3400 records after de-duplicating hits from different databases plus 48 studies identified via other methods. A total of 233 studies were included in the analysis. Further details are available in Supplementary Fig. S2.

General Results

The majority (66.1%) of the included studies reported data from Europe and Central Asia, yet the most frequent country considered in studies was the USA (46 studies), followed by Germany (35 studies). High-income countries represented more than 85% of the included studies, while only one study reported from a low-income country. More than 90% of the studies were observational, while only 9 studies used economic models and 36 were systematic literature reviews.

Clinical Burden

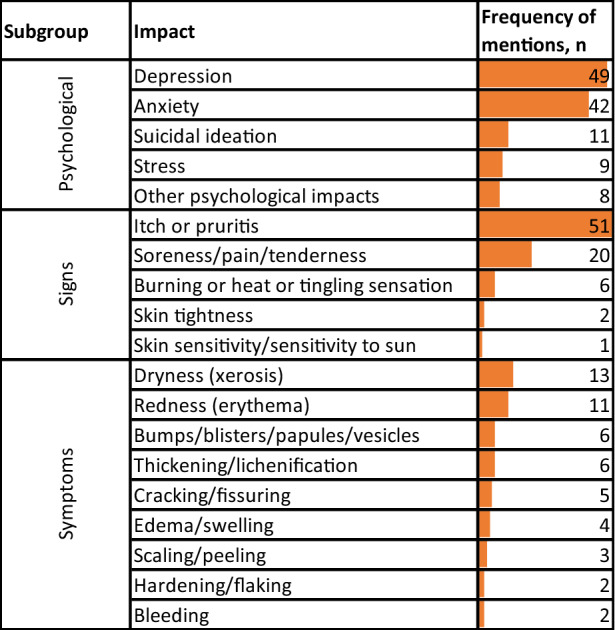

Itching (also known as pruritis in some studies), depression, and anxiety were the most frequently reported impact parameters in the clinical burden domain (51, 49, and 42 mentions, respectively). Figure 1 shows the frequency of the different clinical burden domains of impact. Itching was the most commonly mentioned clinical impact due to AD. Based on the aggregated data points, the itching or pruritis prevalence in patients with AD ranged from 21% up to 100% [30–35].

Fig. 1.

Frequency of mentioning different impacts related to clinical burden in the included studies

Eight studies reported the median severity of itch due to AD based on a 0–10 numerical rating scale. The median values describing the severity of itch ranged from 4 to 9, with an average of 6 (where 10 represents the highest level of itch) [28, 36–42]. A similar range exists with mean values ranging from 3 to 9, with an average of 6, for studies using a VAS (also 0–10) [9, 43–49].

Eleven studies reported diagnosis of depression prevalence values among patients with AD [26, 30, 50–58]. The average of all prevalence values was 18%. Prevalence estimates ranged from 3% to 57%. These results were slightly different from the self-reported depression values, which ranged from 10% to 37%, with an average of 26% [59–62].

The prevalence of anxiety among patients with AD ranged from 1.2% to 64%. These values were reported by 11 studies with an average anxiety of 24.12%. According to Mizara et al. [63], 41% of patients had a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score of at least 11, which indicates a definitive case of anxiety.

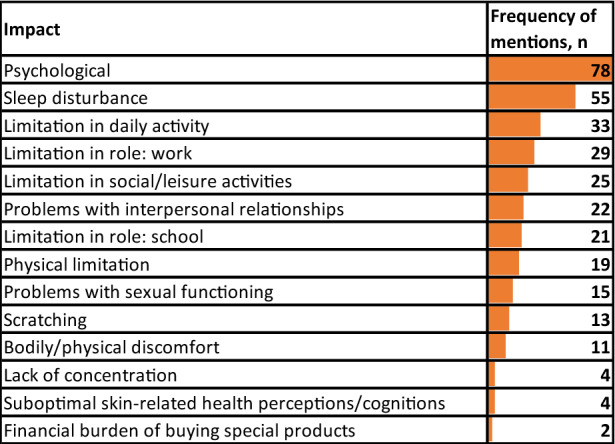

Humanistic Burden

Concerning the humanistic burden, AD was shown to decrease QoL by impacting different aspects of patients’ lives. Among the included studies, the psychological impact was by far the most mentioned impact (78 times) causing loss in QoL, followed by sleep disturbance (55 times). The details of frequency of mentioning each aspect affecting patients’ QoL is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of mentioning humanistic burden impacts in the included studies

Sleep disturbance was very common among studies discussing AD burden and included nocturnal awakening due to itch and difficulty in sleep induction [40, 64, 65]. According to the included studies, sleep disturbance results in using sleeping pills or feeling sleepy, unproductive, or lacking concentration during the day [52, 66]. Several studies reported sleep disturbance in more than 70% of patients with AD [34, 45, 65, 67], while others showed lower prevalence, as low as 4.18% [51]. One study used subgroups for sleep disturbances and reported that 38.4% of patients had no difficulties, 23.9% had mild difficulties, 28.2% had moderate difficulties, and 9.6% had severe difficulties in sleeping due to AD [68]. One study also showed that controlling AD resulted in better outcomes related to sleep disturbance: only 8.5% of patients with adequately controlled AD experienced sleep disturbances compared with 23.8% in patients with inadequately controlled AD [69].

QoL Score Burden

The average utility value for the AD general population was about 0.779 based on 71 studies. Patients with the lowest severity had the highest HRQoL (utility), represented by an average utility value of 0.873. HRQoL decreased gradually with increasing severity, with an average utility value of 0.548 for the most severe patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Utility values based on severity ranks

| Severity rank | Number of studies reporting values | Average utility | Minimum utility | Maximum utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstratified population | 71 | 0.779 | 0.432 | 0.940 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.873 | 0.869 | 0.877 |

| 2 | 25 | 0.807 | 0.732 | 0.912 |

| 3 | 15 | 0.728 | 0.633 | 0.832 |

| 4 | 25 | 0.676 | 0.551 | 0.881 |

| 5 | 3 | 0.548 | 0.420 | 0.668 |

Among 597 data point estimates for the QoL questionnaires, several questionnaires were used, including VAS (77), the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (66), Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) (46), EQ-5D (40), AD Burden Scale (36), and Skindex (33). Yet, DLQI and cDLQI questionnaires were the most used to assess the QoL for patients with AD (299 data points).

Multivariate Regression Model for Utility

According to the multivariate regression model (Table 2), male patients with AD had significantly lower utility compared with female patients. Age was not a statistically significant explanatory variable for utility. Conforming with previous findings (Table 1), severity was inversely proportional to utility value.

Table 2.

Multivariate regression model for utility of patients with AD

| Parameter | Beta coefficient (β) | Standard error | 95% Wald confidence interval | Hypothesis test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Wald chi-squared | Degrees of freedom (df) | Significance | |||

| (Intercept) | 1.348 | 0.2433 | 0.871 | 1.825 | 30.675 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Severity rank = 2 | 0.108 | 0.0256 | 0.058 | 0.158 | 17.746 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Severity rank = 3 | 0.086 | 0.0504 | −0.013 | 0.185 | 2.925 | 1 | 0.087 |

| Severity rank = 4 | 0a | ||||||

| Age, years | −0.005 | 0.0031 | −0.011 | 0.001 | 2.626 | 1 | 0.105 |

| % of males | −0.863 | 0.2772 | −1.406 | −0.319 | 9.686 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Scale | 0.001b | 0.0006 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |||

Dependent variable: quality of life

aSet to zero because this parameter is redundant

bMaximum-likelihood estimate

Economic Burden

Of the included studies, 70 provided data about costs and HCRU. Of those, 41 studies included (direct and indirect) cost data and 32 included HCRU data (e.g., number of outpatient visits). Twenty-eight studies included other economic data, of which the majority reported productivity loss.

Healthcare Resource Utilization

Data collected for AD comprise a wide range of severity and diversity in HCRU, including outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations. Studies usually reported separate data for different severity groups.

Dermatologist visits ranged from 2.8 to 16.3 per year for the unstratified population, with an average of 8.6 [28, 59, 70–72]. Primary care/general practitioner visits averaged 16.5 per year [70, 73, 74], with this number varying significantly by severity, where it reached 20.44 healthcare provider visits per year in patients with moderate to severe AD [50]. Two studies reported the visits of patients with AD to medical specialists other than dermatology, which were allergy and internal medicine, with a rate of 0.2–0.4 visits per year, respectively [70, 72].

As severity increased, the frequency of emergency visits increased. However, for all severity ranks, studies reported a low rate of emergency department admissions. Considering unstratified patients with AD, studies reported a minimum of 0.05 visits per year and up to 1.22 visits per patient per year, with an average of 0.80 visits [50, 68, 71, 74, 75].

For patients with rank 2 severity, the average number of annual emergency department visits per patient was 0.5 [50, 68, 71, 73, 74]. The average was 0.92 visits for patients with rank 3 severity [68, 74] and 1.41 for rank 4 severity [50, 68, 71, 73, 74]. The average annual number of hospitalizations (for the unstratified population) ranged from 0.03 to 1.2 admissions [50, 71, 73, 75]. Patients with severity rank 4 had an average annual hospitalization rate of 0.75 per year [50, 68, 71, 73, 75]. On the other hand, those with severity rank 2 had an average annual hospitalization rate of 0.45 per year [68, 71, 73, 75].

Costs

There was significant heterogeneity between individual studies since the studies came from different countries and several income levels. The total cost of AD per patient was mentioned in eight studies, in which the annual average cost was estimated to be 5246 USD (2020), with a minimum of 769 USD and a maximum of 23,638 USD [72, 74, 76–81]. The average total cost calculated from the studies was less than the sum of average total direct and total indirect cost due to the heterogeneity in sources and calculation methods. Nine studies reported total direct costs with an annual average cost of 4411 USD [48, 72, 76, 82–87]. The total indirect cost per patient was reported in three studies with an average cost of 9068 USD per year [72, 76, 88]. Cost details are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Average annual cost per patient with AD (unweighted)

| Type of economic burden (direct/indirect) | Number of studies reporting the cost | Number of patients in the studies | Minimum reported cost (2020 USD) |

Average cost (2020 USD) |

Maximum reported cost (2020 USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total direct cost | 9 | 119,750 | 940 | 4411 | 11,536 |

| Total indirect cost | 3 | 218 | 1289 | 9068 | 15,650 |

Some studies reported economic data stratified by different factors, most commonly by severity (24 studies), followed by treatment groups (12 studies) and age (9 studies). The exact studies and strata are reported in Supplementary Table S2.

Productivity Lost

Several studies mentioned the economic burden incurred by AD due to productivity lost, which was usually quantified by the number of days of absenteeism and/or presenteeism. Among 28 studies reporting numbers or percentages of workdays lost due to AD as presenteeism or absenteeism, 20 reported absenteeism values separately, 13 reported presenteeism separately, and 14 reported both absenteeism and presenteeism values.

Productivity is significantly affected by AD, as seen by a total of 68.8 days lost annually due to absenteeism and presenteeism combined (for the unstratified population). The presenteeism (54 days lost) [42, 59–61, 72, 73, 78, 83, 89–91] effect was dominant, being more than three times the days lost due to absenteeism (14.8 days lost) [42, 59–61, 65, 72, 73, 78, 83, 88–93]. Productivity lost in days differed significantly among severity ranks, with patients with severity rank 5 losing on average 26.5 days due to absenteeism and 92.5 days due to presenteeism, compared with patients with rank 1, who lost an average of 2.5 days due to absenteeism and 13.6 days due to presenteeism [78, 94]. Table 4 presents the average number of days lost due to absenteeism and presenteeism based on the severity rank.

Table 4.

Average number of days lost per year due to absenteeism and presenteeism, by severity rank

| Severity rank | Absenteeism only | Presenteeism only | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstratified population | 14.8 | 54.0 | 68.8 |

| 1 | 2.5 | 13.6 | 16.1 |

| 2 | 14.0 | 58.5 | 72.5 |

| 3 | 23.3 | 78.5 | 101.8 |

| 4 | 24.0 | 95.5 | 119.4 |

| 5 | 26.5 | 92.5 | 119.0 |

Discussion

The highly prevalent chronic inflammatory skin disease AD affects adults and adolescents, with a significant DALY burden [1]. However, until recently, AD was generally considered to be merely a skin disorder [95]. Many efforts have been made to quantify different aspects of the burden of AD. We aimed to aggregate the findings from different studies to provide a holistic view of AD burden from the humanistic, economic, and clinical perspectives for adult and adolescent patients. Furthermore, due to the abundance of studies evaluating each burden element, we were able to stratify the impact based on additional factors, such as severity.

To date, there is no cure for AD [96]. However, based on these results that show a solid correlation between severity and HRQoL, as well as productivity lost, maintaining patients with mild disease severity could offset most of the burden. This study should be considered as a first step in mitigating the burden of AD by providing an overview of the scale and factors of AD burden. The next step to decrease AD burden should be to research further into specific policy actions that could improve the prognosis of patients with AD. This research should be validated from a local perspective to ensure its eligibility within the healthcare system structure and from the cultural perspective.

The burden of AD might be underestimated in low- and middle-income countries because, despite the abundance of literature on the topic, most of the literature came from higher-income countries; low- and middle-income countries were not equivalently represented in the literature. The global burden of disease study found a positive correlation between disease burden and gross domestic product [1]; however, this might be due to insufficient data and underreporting of AD in lower- and middle-income countries.

As expected, itching was the most commonly mentioned symptom in the literature for patients with AD, in some cases being reported to affect 100% of patients. This symptom was followed by depression and anxiety, which highlights the significance of the psychological illness impact on patients with AD, which was further confirmed by the humanistic burden data, where again, psychological illness ranked number one in terms of frequency of mentions in the literature. Sleep disturbance followed psychological illness in the ranking within the humanistic burden, which is not unexpected since it is linked to nocturnal awakening due to itch [64]. Although sleep disturbance might not be an issue if it is a one-night problem, the impact is amplified when the confounding factor is a chronic disease, and the majority of patients with AD do experience sleep disturbance. Sleep disturbance can lead to a cascade of implications, such as the use of sleeping pills, and usually causes a lack of concentration and lethargy [64, 66].

One of the main consequences of sleep disturbance is productivity loss due to lack of concentration, and lethargy, which might explain the significantly higher presenteeism compared with absenteeism. The productivity lost for the unstratified population by severity made up about one-third of the year, while for the most severe cases, the total productivity lost even exceeded half of the year.

Looking at the HRQoL, the variability of utility lost between different severity groups was significantly wide, which was further confirmed when we developed a multiple regression model that included severity, age, and sex as independent variables.

Our results concerning humanistic burden are concordant with a recent study in Europe assessing the AD burden of illness in adults [61]. It also states that anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and overall and general impairment create a significant burden for patients with AD compared with controls. Another study by Reed et al. also confirms our findings of the significant losses in QoL and school or work absenteeism burden due to AD [97].

Drucker et al. estimated a similar total annual cost per patient in the USA in 2013 [75], ranging from 3302 to 4463 USD, compared with our estimate of 4411 USD. However, our estimate is not confined only to the USA. The similarity of these values is probably due to the underreporting of the burden in low- and middle-income countries, which might have decreased the average cost if their data were available, as these countries usually have lower unit costs owing to their relatively low gross domestic product.

Because of the diversity of the included studies, each had a different methodology and perspective; therefore, for some calculations, the values from two or more studies could not be used for summary statistics. However, we grouped similar methodological articles for each part of the burden and created summary statistics for specific subgroups. For the same reason, all summary statistics were calculated as nonweighted average values as it was not feasible to calculate the statistics based on the number of patients in each study due to the diversity of studies. Since severity was not measured in the same way in all included studies, we used the severity ranking approach. Although this approach may not provide the most accurate severity estimates, we assume that it is sufficient to provide useful insights about the burden. As costs from different studies were converted to USD and adjusted for inflation, the aggregated results should be interpreted with caution, as the purchasing power parity and treatment protocols, as well as the variance between drugs and medical services in different countries, might have significant effects. The regression was performed without considering the weights of patient numbers because of the difficulties in extracting the number of patients for each subgroup of patients as they usually overlapped.

Conclusions

The burden of AD is significant due to its high prevalence as well as the magnitude of its impact. While the disease is incurable, reducing the severity of the disease and modifying the prognosis of patients could significantly reduce the burden.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

AbbVie funded this research and participated the review and approval of the publication. All authors had access to relevant data and participated in the drafting, review, and approval of this publication. Abbvie funded the journal’s rapid service.

Medical Writing Assistance

The Authors would like to thank all contributors for their commitment and dedication to this publication. Medical writing was provided by Baher Elezbawy and Ahmad Fasseeh of Syreon Middle East and funded by Abbvie.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

ZK, ANF and BE constructed the study design. BE, NK and ANF conducted the systematic review. ShA, MT, HD and SaA facilitated the steps of the research. ANF, BE and NK conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. ZK, ShA, MT, HD and SaA participated in revision of all study steps. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

AbbVie sponsored the analysis and interpretation of Data; in reviewing and approval of the final version. Ahmad N Fasseeh, Sherif Abaza, Zoltàn Kalò are shareholders in Syreon Middle East. Baher Elezbawy and Nada Korra are employees at Syreon Middle East. Mohamed Tannira, Hala Dalle, and Sandrine Aderian are AbbVie employees and may hold AbbVie stock. No conflict of interest and no authorship payments were done.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Prior Presentation

These data were previously presented at Virtual ISPOR Europe 2021 conference.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

References

- 1.Laughter MR, Maymone MBC, Mashayekhi S, Arents BWM, Karimkhani C, Langan SM, et al. The global burden of atopic dermatitis: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(2):304–309. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIAMS. “Atopic Dermatitis.” National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/atopic-dermatitis. Accessed 15 Oct 2018.

- 3.Atopic dermatitis (eczema)—Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/atopic-dermatitis-eczema/symptoms-causes/syc-20353273. Accessed 3 Jun 2021.

- 4.Zuberbier T, Orlow SJ, Paller AS, Taïeb A, Allen R, Hernanz-Hermosa JM, et al. Patient perspectives on the management of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbabi M, Zhand N, Samadi Z, Ghaninejad H, Golestan B. Psychiatric comorbidity and quality of life in patients with dermatologic diseases. Iran J Psychiatry. 2009;4:102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson W, Anderson HR. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(4):947–54.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ring J, Zink A, Arents BWM, Seitz IA, Mensing U, Schielein MC, et al. Atopic eczema: burden of disease and individual suffering—results from a large EU study in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(7):1331–1340. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devleesschauwer B, Maertens de Noordhout C, Smit GS, Duchateau L, Dorny P, Stein C, et al. Quantifying burden of disease to support public health policy in Belgium: opportunities and constraints. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mann C, Dreher M, Weess HG, Staubach P. Sleep disturbance in patients with urticaria and atopic dermatitis: an underestimated burden. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(6):1–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen CJ, Uddin MJ, Saha SK, Darmstadt GL. Prevalence and psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis in Bangladeshi children and families. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0249824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marron SE, Cebrian-Rodriguez J, Alcalde-Herrero VM, Garcia-Latasa de Aranibar FJ, Tomas-Aragones L. Psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis in adults: a qualitative study. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed) 2020;111(6):513–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukunaga N, Okada Y, Konishi Y, Murashita T, Koyama T. Pay attention to valvular disease in the presence of atopic dermatitis. Circ J. 2013;77(7):1862–1866. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheary B, Harris MF. Cessation of long-term topical steroids in adult atopic dermatitis: a prospective cohort study. Dermatitis. 2020;31(5):316–320. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant L, Seiding Larsen L, Trennery C, Silverberg JI, Abramovits W, Simpson EL, et al. Conceptual model to illustrate the symptom experience and humanistic burden associated with atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents. Dermatitis. 2019;30(4):247–254. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Bank Country and Lending Groups—World Bank Data help desk. 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 10 Aug 2021.

- 18.Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 Suppl):S115–S123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverwood RJ, Mansfield KE, Mulick A, Wong AYS, Schmidt SAJ, Roberts A, et al. Atopic eczema in adulthood and mortality: UK population-based cohort study, 1998–2016. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(5):1753–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank. Consumer price index (2010 = 100) | Data; 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL. Accessed 12 Aug 2021.

- 21.Taiwan Consumer Price Index (CPI) | 1959–2021 Data | 2022–2023 Forecast | Historical; 2021. https://tradingeconomics.com/taiwan/consumer-price-index-cpi. Accessed 12 Aug 2021.

- 22.Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average) | Data; 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.FCRF. Accessed 27 Feb 2022.

- 23.DLQI to EQ-5D tool. Broadstreet. https://dlqi.broadstreetheor.com/. Accessed 23 Aug 2021.

- 24.Andersen L, Nyeland ME, Nyberg F. Higher self-reported severity of atopic dermatitis in adults is associated with poorer self-reported health-related quality of life in France, Germany, the U.K. and the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(5):1176–83. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le PH, Vo TQ, Nguyen NH. Quality of life measurement alteration among Vietnamese: impact and treatment benefit related to eczema. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(Suppl 2):S49–S56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SH, Lee SH, Lee SY, Lee B, Lee SH, Park YL. Psychological health status and health-related quality of life in adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide cross-sectional study in South Korea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(1):89–97. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Misery L, Seneschal J, Reguiai Z, Merhand S, Héas S, Huet F, et al. The impact of atopic dermatitis on sexual health. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(2):428–432. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katoh N, Saeki H, Kataoka Y, Etoh T, Teramukai S, Takagi H, et al. Atopic dermatitis disease registry in Japanese adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (ADDRESS-J): baseline characteristics, treatment history and disease burden. J Dermatol. 2019;46(4):290–300. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.OECD. Hours worked (indicator); 2021. https://data.oecd.org/emp/hours-worked.htm. Accessed 10 Aug 2021.

- 30.Ameen M, Rabe A, Blanthorn-Hazell S, Millward R. The prevalence and clinical profile of atopic dermatitis (AD) in England—a population based linked cohort study using clinical practice research datalink (CPRD) and Hospital episode statistics (HES) Value Health. 2020;23(s2):S745. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Augustin M, Langenbruch A, Blome C, Gutknecht M, Werfel T, Ständer S, et al. Characterizing treatment-related patient needs in atopic eczema: insights for personalized goal orientation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(1):142–152. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chee A, Branca L, Jeker F, Vogt DR, Schwegler S, Navarini A, et al. When life is an itch: What harms, helps, and heals from the patients' perspective? Differences and similarities among skin diseases. Dermatol Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1111/dth.13606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falissard B, Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Papp KA, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Qualitative assessment of adult patients’ perception of atopic dermatitis using natural language processing analysis in a cross-sectional study. Dermatology and Therapy. 2020;10(2):297–305. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00356-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng MSY, Tan S, Chan NHQ, Foong AYW, Koh MJA. Effect of atopic dermatitis on quality of life and its psychosocial impact in Asian adolescents. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59(2):e114–e117. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Li LF, Zhao DY, Shen YW. Prevalence and clinical features of atopic dermatitis in China. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:2568301. doi: 10.1155/2016/2568301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrucci S, Casazza G, Angileri L, Tavecchio S, Germiniasi F, Berti E, et al. Clinical response and quality of life in patients with severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a single-center real-life experience. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):791. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei D, Yousaf M, Janmohamed SR, Vakharia PP, Chopra R, Chavda R, et al. Validation of four single-item patient-reported assessments of sleep in adult atopic dermatitis patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(3):261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lei DK, Yousaf M, Janmohamed SR, Vakharia PP, Chopra R, Sacotte R, et al. Validation of patient-reported outcomes information system sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(5):875–882. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nettis E, Ferrucci SM, Ortoncelli M, Pellacani G, Foti C, Di Leo E, et al. Use of dupilumab for 543 adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a multicenter, retrospective study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2020;32:124–132. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heckman CJ, Riley M, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Yosipovitch G. Development and initial psychometric properties of two itch-related measures: scratch intensity and impact, sleep-related itch and scratch. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(11):2138–45.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.03.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heratizadeh A, Haufe E, Stölzl D, Abraham S, Heinrich L, Kleinheinz A, et al. Baseline characteristics, disease severity and treatment history of patients with atopic dermatitis included in the German AD Registry TREAT Germany. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(6):1263–1272. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei W, Ghorayeb E, Andria M, Walker V, Schnitzer J, Kennedy M, et al. A real-world study evaluating adeQUacy of Existing Systemic Treatments for patients with moderate-to-severe Atopic Dermatitis (QUEST-AD): baseline treatment patterns and unmet needs assessment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(4):381–8.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boehm D, Schmid-Ott G, Finkeldey F, John SM, Dwinger C, Werfel T, et al. Anxiety, depression and impaired health-related quality of life in patients with occupational hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;67(4):184–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2012.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chrostowska-Plak D, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Relationship between itch and psychological status of patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(2):e239–e242. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaaz K, Szepietowski JC, Matusiak Ł. Influence of itch and pain on sleep quality in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(2):175–180. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Os-Medendorp H, van Leent-de WI, de Bruin-Weller M, Knulst A. Usage and users of online self-management programs for adult patients with atopic dermatitis and food allergy: an explorative study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(2):e57. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Napolitano M, Fabbrocini G, Scalvenzi M, Nisticò SP, Dastoli S, Patruno C. Effectiveness of dupilumab for the treatment of generalized Prurigo nodularis phenotype of adult atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2020;31(1):81–84. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Väkevä L, Niemelä S, Lauha M, Pasternack R, Hannuksela-Svahn A, Hjerppe A, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy improves quality of life of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis patients up to 3 months: results from an observational multicenter study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2019;35(5):332–338. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holm JG, Agner T, Clausen ML, Thomsen SF. Quality of life and disease severity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(10):1760–1767. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dieris-Hirche J, Gieler U, Petrak F, Milch W, Te Wildt B, Dieris B, et al. Suicidal ideation in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a German cross-sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(10):1189–1195. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Igarashi A, Fujita H, Arima K, Inoue T, Dorey J, Fukushima A, et al. Health-care resource use and current treatment of adult atopic dermatitis patients in Japan: a retrospective claims database analysis. J Dermatol. 2019;46(8):652–661. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silverberg JI, Lei D, Yousaf M, Janmohamed SR, Vakharia PP, Chopra R, et al. Association of atopic dermatitis severity with cognitive function in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1349–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwak Y, Kim Y. Health-related quality of life and mental health of adults with atopic dermatitis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(5):516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mina S, Jabeen M, Singh S, Verma R. Gender differences in depression and anxiety among atopic dermatitis patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(2):211. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sorour FA, Abdelmoaty AA, Bahary MH, El Birqdar B. Psychiatric disorders associated with some chronic dermatologic diseases among a group of Egyptian dermatology outpatient clinic attendants. J Egypt Womens Dermatol Soc. 2017;14:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu CY, Lu YY, Lu CC, Su YF, Tsai TH, Wu CH. Osteoporosis in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0171667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Egeberg A, Andersen YM, Gislason GH, Skov L, Thyssen JP. Prevalence of comorbidity and associated risk factors in adults with atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2017;72(5):783–791. doi: 10.1111/all.13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim SH, Hur J, Jang JY, Park HS, Hong CH, Son SJ, et al. Psychological distress in young adult males with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(23):e949. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arima K, Gupta S, Gadkari A, Hiragun T, Kono T, Katayama I, et al. Burden of atopic dermatitis in Japanese adults: analysis of data from the 2013 national health and wellness survey. J Dermatol. 2018;45(4):390–396. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the United States: an analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):274–9.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eckert L, Gupta S, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM. Burden of illness in adults with atopic dermatitis: analysis of national health and wellness survey data from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee J, Cho D-k, Kim J, Im E-J, Bak J, Lee K, et al. Itchtector: a wearable-based mobile system for managing itching conditions. In: Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems; 2017.

- 63.Mizara A, Papadopoulos L, McBride SR. Core beliefs and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis and atopic eczema attending secondary care: the role of schemas in chronic skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(5):986–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Civelek E, Sahiner UM, Yüksel H, Boz AB, Orhan F, Uner A, et al. Prevalence, burden, and risk factors of atopic eczema in schoolchildren aged 10–11 years: a national multicenter study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21(4):270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Langenbruch A, Radtke M, Franzke N, Ring J, Foelster-Holst R, Augustin M. Quality of health care of atopic eczema in Germany: results of the national health care study AtopicHealth. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(6):719–726. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu SH, Attarian H, Zee P, Silverberg JI. Burden of sleep and fatigue in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2016;27(2):50–58. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bobotsis R, Fleming P, Eshtiaghi P, Cresswell-Melville A, Drucker AM. A Canadian adult cross-sectional survey of the burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(4):445–446. doi: 10.1177/1203475418758992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Girolomoni G, Luger T, Nosbaum A, Gruben D, Romero W, Llamado LJ, et al. The economic and psychosocial comorbidity burden among adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in Europe: analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Dermatol Ther. 2020;11(1):117–130. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00459-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wei W, Anderson P, Gadkari A, Blackburn S, Moon R, Piercy J, et al. Extent and consequences of inadequate disease control among adults with a history of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2018;45(2):150–157. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shalom G, Babaev M, Kridin K, Schonmann Y, Horev A, Dreiher J, Cohen AD. Healthcare service utilization by 116,816 patients with atopic dermatitis in Israel. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2019;99(4):370–374. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM. The burden of atopic dermatitis in US adults: health care resource utilization data from the 2013 national health and wellness survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):54–61.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ariëns LFM, Van Nimwegen KJM, Shams M, De Bruin DT, Van der Schaft J, Van Os-Medendorp H, et al. Economic burden of adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis indicated for systemic treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(9):762–768. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whiteley J, Emir B, Seitzman R, Makinson G. The burden of atopic dermatitis in US adults: results from the 2013 national health and wellness survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(10):1645–1651. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2016.1195733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Carrillo JC. Economic impact of atopic dermatitis in adults: a population-based study (IDEA study) Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (English Edn) 2018;109(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Drucker AM, Qureshi AA, Amand C, Villeneuve S, Gadkari A, Chao J, et al. Health care resource utilization and costs among adults with atopic dermatitis in the United States: a claims-based analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(4):1342–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim C, Yim H, Jo S, Ahn S, Seo S, Choi W. The costs of illness of atopic dermatitis in South Korea. Value Health. 2014;17(7):A594. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Launois R, Ezzedine K, Cabout E, Reguai Z, Merrhand S, Heas S, et al. Importance of out-of-pocket costs for adult patients with atopic dermatitis in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(10):1921–1927. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Murota H, Inoue S, Yoshida K, Ishimoto A. Cost of illness study for adult atopic dermatitis in Japan: a cross-sectional web-based survey. J Dermatol. 2020;47(7):689–698. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Norrlid H, Hjalte F, Lundqvist A, Svensson Å, Ragnarson TG. Cost-effectiveness of maintenance treatment with a barrier-strengthening moisturizing cream in patients with atopic dermatitis in Finland, Norway and Sweden. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2016;96(2):173–176. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ostermann JK, Witt CM, Reinhold T. A retrospective cost-analysis of additional homeopathic treatment in Germany: Longterm economic outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0182897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ostermann JK, Reinhold T, Witt CM. Can additional homeopathic treatment save costs? A retrospective cost-analysis based on 44500 insured persons. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0134657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Joish V, Sullivan S, Hartisch C, Kamalakar R, Eichenfield L. PHS18 economic burden of atopic dermatitis from a United States payer perspective. Value Health. 2012;15(7):A521. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Le PH, Vo TQ. Economic burden and productivity loss related to eczema: a prevalence-based follow-up study in Vietnam. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(2):S57–S63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schild M, Weber V, Galetzka W, Enders D, Zügel FS, Gothe H. Healthcare resource utilization and associated costs among patients with atopic dermatitis—a retrospective cohort study based on German health claims DATA. Value Health. 2020;23(S2):S745. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00773-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Crisaborole | CADTH. 2021. https://www.cadth.ca/crisaborole. Accessed 28 Sep 2021.

- 86.Dupilumab | CADTH. 2021. https://www.cadth.ca/dupilumab. Accessed 28 Sep 2021.

- 87.Dupilumab | CADTH. 2021. https://www.cadth.ca/dupilumab-0. Accessed 28 Sep 2021.

- 88.Kim C, Park KY, Ahn S, Kim DH, Li K, Kim DW, et al. Economic impact of atopic dermatitis in Korean patients. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27(3):298–305. doi: 10.5021/ad.2015.27.3.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lin Y, Chu C, Cho Y, Lee C, Tsai C, Tang C. PSY11 Work productivity and activity impairment among patients with atopic dermatitis in Taiwan. Value Health. 2019;22:S376. [Google Scholar]

- 90.van Os-Medendorp H, Appelman-Noordermeer S, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, de Bruin-Weller M. Sick leave and factors influencing sick leave in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Med. 2015;4(4):535–547. doi: 10.3390/jcm4040535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yano C, Saeki H, Ishiji T, Ishiuji Y, Sato J, Tofuku Y, et al. Impact of disease severity on work productivity and activity impairment in Japanese patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40(9):736–739. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ezzedine K, Shourick J, Merhand S, Sampogna F, Taïeb C. Impact of atopic dermatitis in adolescents and their parents: a French study. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2020;100(17):00294. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Torrelo A, Ortiz J, Alomar A, Ros S, Prieto M, Cuervo J. Atopic dermatitis: impact on quality of life and patients' attitudes toward its management. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22(1):97–105. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Andersen L, Nyeland ME, Nyberg F. Increasing severity of atopic dermatitis is associated with a negative impact on work productivity among adults with atopic dermatitis in France, Germany, the UK and the USA. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(4):1007–1016. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis: an expanding therapeutic pipeline for a complex disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21(1):21–40. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Atopic dermatitis (eczema)—symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/atopic-dermatitis-eczema/symptoms-causes/syc-20353273#:~:text=No%20cure%20has%20been%20found,apply%20medicated%20creams%20or%20ointment . Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

- 97.Reed B, Blaiss MS. The burden of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39(6):406–410. doi: 10.2500/aap.2018.39.4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.