Abstract

Background

Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are the most significant Campylobacter species responsible for severe gastrointestinal disorders. Raw poultry meat is considered a source of Campylobacter transmission to the human population.

Objectives

The present study was aimed to assess the prevalence rate, antibiotic resistance properties, virulence characters and molecular typing of C. jejuni and C. coli strains isolated from raw poultry meat samples.

Methods

Three hundred and eighty raw poultry meat samples were collected and analysed for the presence of Campylobacter spp. using the microbial culture. Species identification was done using the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Disk diffusion was developed to assess the antimicrobial resistance pattern of isolates. The distribution of virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes was determined by PCR. Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus‐PCR was used for molecular typing.

Results

Campylobacter species were isolated from 6.25% of examined samples. C. jejuni and C. coli contamination rates were found to be 57.44% and 48.14%, respectively. C. jejuni strains harboured the highest resistance rate against serythromycin (42.59%), ampicillin (38.88%), ciprofloxacin (33.33%), chloramphenicol (31.48%) and tetracycline (31.48%). C. coli isolates harboured the highest resistance rate against ampicillin (73.07%), ciprofloxacin (73.07%), erythromycin (65.38%) and chloramphenicol (50%). AadE1 (44.44%), blaOXA‐61 (42.59%) and tet(O) (35.18%) were the most commonly detected resistance genes in C. jejuni and cmeB (34.61%) and blaOXA‐61 (34.61%) were the most commonly detected among C. coli strains. The most frequent virulence factors among the C. jejuni isolates were flaA (100%), ciaB (100%), racR (83.33%), dnaJ (81.48%), cdtB (81.48%), cdtC (79.62%) and cadF (74.07%). The most frequent virulence factors among the C. coli isolates were flaA (100%), ciaB (100%), pldA (65.38%) and cadF (61.53%).

Conclusions

The majority of C. jejuni and C. coli strains had more than 80% similarities in their ERIC‐PCR pattern, which may show their common source of transmission. The role of goose and quebec meat samples as reservoirs of virulent and antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter spp. was determined.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, Campylobacter coli, Campylobacter jejuni, molecular typing, raw poultry meat, virulence factors

Chicken and Turkey meat samples harboured the highest contamination rates. C. jejuni and C. coli isolates harboured a high resistance rate against some antibiotics, which was accompanied by the high distribution of most antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Campylobacter species (spp.) are important foodborne pathogens responsible for the majority of cases of enteric infections known as campylobacteriosis in developed and developing countries (Abukhattab et al., 2022). In recent years, about 500 million cases of gastrointestinal infections due to the Campylobacter species have been reported globally (Marotta et al., 2019). In 2017, campylobacteriosis is determined as the most common zoonotic disease with about 246,000 confirmed cases and a morbidity rate of 64.8 per 100,000 population in the European Union [European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (EFSA and ECDC), 2017].

Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) and C. coli are major species responsible for severe cases of human gastroenteritis (Igwaran & Okoh, 2019). Humans most often become infected by ingesting contaminated food, particularly undercooked poultry meat (Myintzaw et al., 2022). Poultry carcasses are typically contaminated during defeathering and evisceration by faeces leakage containing campylobacters from the cloaca (Hakeem & Lu, 2021). In most cases, campylobacteriosis is typically self‐limiting; however, complications may occur in some persons. Around 1 in 1000 infected individuals develops Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), a thoughtful autoimmune‐mediated neurological disorder that causes weakness of extremities, complete paralysis, respiratory insufficiency and death (Scallan Walter et al., 2020).

Diseases caused by Campylobacter spp. are commonly occurred due to the presence and activity of diverse kinds of virulence factors. In this regard, cytolethal distending toxin (cdt), phospholipase A outer membrane (pldA), IV secretory system (virB11), flagellar gene (flaA), Campylobacter invasion antigen B (ciaB), Campylobacter adhesion to fibronectin (cadF), regulatory protein R (racR), chaperone protein (dnaJ), Guillain‐Barré syndrome associated genes (cgtB and wlaN), and enterochelin binding lipoprotein encoded by siderophore transport (ceuE) are responsible for the adhesion and invasion of Campylobacter spp. to the human epithelial cells (Hassan et al., 2019).

Recent reports revealed the high resistance rate of Campylobacter spp. strains towards different types of antimicrobial agents (Audu et al., 2022). Antimicrobial‐resistant Campylobacter strains caused more severe infections for a longer time with a higher economic burden (Luangtongkum et al., 2009). Campylobacter spp. strains isolated from human clinical infections and poultry sources harboured high resistance towards aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, penicillins, quinolones, cephalosporins, phenicols, macrolides and β‐lactams antimicrobials (Hlashwayo et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2019). In this regard, kanamycin‐resistance determinant (aphA‐3), multidrug efflux pump gene (cmeB), tetracyclines resistance encoding gene (tet(O)), β‐lactams resistance gene (blaOXA‐61) and aminoglycosides determinant gene (aadE1) were predominant among the Campylobacter strains isolated from resistance cases (Elhadidy et al., 2020; Pérez‐Boto et al., 2014).

Diverse Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)‐based typing, such as PCR sequencing, PCR‐ribotyping and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR (ERIC‐PCR) have been developed for the molecular typing of Campylobacter spp. (Igwaran & Okoh, 2020a). ERIC‐PCR technique is a simple tool used to differentiate bacteria strains isolated from diverse sources. This technique is a strong tool for the exploration of prokaryotic genomes and has been reported to have improved reproducibility and high discriminatory power (Bilung et al., 2018). Its application for successful typing of Campylobacter spp. has been reported in a previous survey (Staji et al., 2018).

Data about the epidemiology of foodborne campylobacteriosis are scarce in Iran. Additionally, the exact prevalence rate, virulence characters and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spp. were not well defined among poultry in Iran. Thus, the present survey was done to assess the prevalence rate, antimicrobial resistance pattern, distribution of virulence genes and the molecular typing of C. coli and C. jejuni strains isolated from poultry meat samples.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Samples

A total of 380 raw poultry meat samples, including chicken (n = 120), turkey (n = 55), quebec (n = 65), goose (n = 65) and ostrich (n = 75) were randomly collected from retail poultry meat centres, Shahrekord, Iran. Raw poultry meat samples (100 g) were collected from the thigh muscle using sterile plastic bags. Samples were transferred in refrigerated containers at 4°C. Samples transportation and processing were done within 2 h after collection.

2.2. Bacterial isolation and identification

Campylobacter spp. isolation was done according to the EN ISO 10272–1:2006 method (ISO 10272‐1, 2006). Twenty‐five grams of meat were inoculated into 225 ml of Bolton broth (Oxoid) containing the Bolton broth selective supplement (Oxoid) and 5% laked horse blood (Oxoid). Following, bacterial suspension was spread onto Charcoal Cefoperazone Deoxycholate Agar (CCDA) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) plates, and then incubated for 48 h at 42°C under microaerobic conditions (85% N2, 5% O2 and 10% CO2). A colony from each medium was subjected to biochemical examinations, including Gram‐staining, catalase production (3% H2O2), hippurate oxidase and hydrolysis, indoxyl acetate hydrolysis, urease activity and resistance against cephalothin (Nachamkin, 2003). Campylobacter species identification was done using the PCR (Denis et al., 1999). Suspected Campylobacter isolates were sub‐cultured on Bolton broth and incubated for 48 h at 42°C in a microaerobic condition. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the genomic DNA was extracted from the isolates using the DNA extraction kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, St. Leon‐Rot, Germany). The purity (A260/A280) and concentration of the extracted DNA were then checked (NanoDrop, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Furthermore, the DNA's quality was assessed on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, St. Leon‐Rot, Germany). The first primers set was used for detection of Campylobacter genus 16S rRNA gene (F: 5′‐ATCTAATGGCTTAACCATTAAAC‐3′ and R: 5′‐GGACGGTAACTAGTTTAGTATT‐3′) (857 bp). The second one was used to detect C. jejuni mapA gene (F: 5′‐CTATTTTATTTTTGAGTGCTTGTG‐3′ and R: 5′‐GCTTTATTTGCCATTTGTTTTATTA‐3′) (589 bp). The third one was used to detect C. coli ceuE gene (F: 5′‐AATTGAAAATTGCTCCAACTATG‐3′ and R: 5′‐TGATTTTATTATTTGTAGCAGCG‐3′) (462 bp) (Rahimi et al., 2010).

2.3. Antimicrobial resistance pattern

To investigate the pattern of antimicrobial resistance of C. jejuni and C. coli isolates, the simple disk diffusion method (Kirby Baeur) was used. The bacteria were incubated on Mueller‐Hinton agar (Merck, Germany) containing 5% (vol/vol) sheep blood at 42°C under a microaerophilic atmosphere in the presence of diverse antimicrobial discs, including gentamicin (10 μg/disk), ciprofloxacin (5 μg/disk), nalidixic acid (30 μg/disk), tetracycline (30 μg/disk), ampicillin (10 μg/disk), amoxicillin (30 μg/disk), erythromycin (15 μg/disk), azithromycin (15 μg/disk), clindamycin (2 μg/disk) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/disk). The interpretation was done using the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI, 2021). C. jejuni ATCC 33560 and C. coli ATCC 33559 were used as controls in antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

2.4. Detection of virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes

Table 1 shows the PCR conditions met to detect antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors (Datta et al., 2003; Obeng et al., 2012). A programmable DNA thermocycler (Eppendorf Mastercycler 5330, Eppendorf‐Nethel‐Hinz GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) was used in all PCR reactions. In addition, amplified samples were analysed by electrophoresis (120 V/208 mA) in a 2.5% agarose gel stained with 0.1% ethidium bromide (0.4 μg/ml). Besides, UVI doc gel documentation systems (Grade GB004, Jencons PLC, London, UK) were used to analyse images.

TABLE 1.

Primers of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes, annealing temperatures and size of amplicons

| Gene | Primer sequences (5′–3′) | Annealing temperatures (°C) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23S rRNA |

TTAGCTAATGTTGCCCGTACCG TAGTAAAGGTCCACGGGGTCGC |

46 | 485 |

| recR |

GATGATCCTGACTTTG TCTCCTATTTTTACCC |

45 | 584 |

| dnaJ |

AAGGCTTTGGCTCATC CTTTTTGTTCATCGTT |

46 | 720 |

| wlaN |

TTAAGAGCAAGATATGAAGGTG CCATTTGAATTGATATTTTTG |

46 | 672 |

| Virbll |

TCTTGTGAGTTGCCTTACCCCTTTT CCTGCGTGTCCTGTGTTATTTACCC |

53 | 494 |

| cdtC |

CGATGAGTTAAAACAAAAAGATA TTGGCATTATAGAAAATACAGTT |

47 | 182 |

| cdtB |

CAGAAAGCAAATGGAGTGTT AGCTAAAAGCGGTGGAGTAT |

51 | 620 |

| cdtA |

CCTTGTGATGCAAGCAATC ACACTCCATTTGCTTTCTG |

49 | 370 |

| flaA |

AATAAAAATGCTGATAAAACAGGTG TACCGAACCAATGTCTGCTCTGATT |

53 | 585 |

| cadF |

TTGAAGGTAATTTAGATATG CTAATACCTAAAGTTGAAAC |

45 | 400 |

| pldA |

AAGCTTATGCGTTTTT TATAAGGCTTTCTCCA |

45 | 913 |

| ciaB |

TTTTTATCAGTCCTTA TTTCGGTATCATTAGC |

42 | 986 |

| ceuE |

CCTGCTACGGTGAAAGTTTTGC GATCTTTTTGTTTTGTGCTGC |

48.9 | 793 |

| cgtB |

TAAGAGCAAGATATGAAGGTG GCACATAGAGAACGCTACAA |

49.9 | 561 |

| tet(O) |

GCGTTTTGTTTATGTGCG ATGGACAACCCGACAGAAG |

54 | 559 |

| cmeB |

TCCTAGCAGCACAATATG AGCTTCGATAGCTGCATC |

54 | 241 |

| bla OXA‐61 |

AGAGTATAATACAAGCG TAGTGAGTTGTCAAGCC |

54 | 372 |

| aphA‐3‐1 |

TGCGTAAAAGATACGGAAG CAATCAGGCTTGATCCCC |

54 | 701 |

2.5. ERIC‐PCR molecular typing

C. jejuni and C. coli isolates of different raw poultry meat samples were subjected to PCR using the ERIC primer set R1: ATGAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCAC and R2: AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG (Zorman et al., 2006). The PCR reactions were verified by resolving them in 3% agarose gel in a 5× TBE buffer, stained with ethidium bromide at 90 volts for 240 min and viewed. ERIC‐PCR DNA fingerprints were analysed with computer‐assisted pattern analysis using the GelJ v.2.0. software (Heras et al., 2015). The relatedness of the isolates was compared and dendrograms were constructed by UPGMA and cluster analysis was used to determine the relationships between each isolate. The value of discriminatory power [D) was determined using an online calculator for discriminatory power as reported (Milton et al., 2015).

2.6. Data assessment

Data analysis was performed by SPSS Statistics 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi‐square and Fisher's exact two‐tailed tests were performed to assess any significant relationship between the Campylobacter prevalence and virulence and antimicrobial resistance properties. Besides, p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Campylobacter distribution

Table 2 shows the Campylobacter distribution among the examined samples. Ninety‐four out of 380 (6.25%) raw poultry meat samples were contaminated with Campylobacter species. Raw chicken meat samples (61.66%) harboured the highest contamination rate, while raw goose meat (1.53%) harboured the lowest. The total prevalence of C. jejuni and C. coli among the isolated bacteria were 57.44% and 48.14%, respectively. Fourteen (25.92%) isolates were contaminated with other Campylobacter spp. Raw quebec and goose meat samples harboured the highest contamination rate of C. jejuni (100% each), while raw ostrich meat samples (50%) harboured the lowest. There were no positive results for C. coli contamination in raw quebec and goose meat samples. However, raw turkey meat samples (71.42%) harboured the highest contamination rate of C. coli, while raw chicken meat samples (45.23%) harboured the lowest. From a statistical seeing, significant differences were found between types of samples and Campylobacter prevalence (p < 0.05). Additionally, a significant difference was obtained between the prevalence of C. jejuni and C. coli (p < 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Campylobacter distribution among the examined samples

| Raw meat samples | No. of samples collected | No. (%) of Campylobacter‐positive samples | No. (%) of C. jejuni‐positive samples | No. (%) of C. coli‐positive samples | No. (%) of other Campylobacter spp.‐positive samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | 120 | 74 (61.66) | 42 (56.75) | 19 (45.23) | 13 (30.95) |

| Turkey | 55 | 13 (23.63) | 7 (53.84) | 5 (71.42) | 1 (14.28) |

| quebec | 65 | 2 (3.07) | 2 (100.00) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Goose | 65 | 1 (1.53) | 1 (100.00) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ostrich | 75 | 4 (5.33) | 2 (50.00) | 2 (50.00) | ‐ |

| Total | 380 | 94 (6.25) | 54 (57.44) | 26 (48.14) | 14 (25.92) |

3.2. Campylobacter antimicrobial resistance

Table 3 shows the antimicrobial resistance of C. jejuni isolates of examined samples. C. jejuni strains harboured the highest antimicrobial resistance rate against erythromycin (42.59%), ampicillin (38.88%), ciprofloxacin (33.33%), chloramphenicol (31.48%) and tetracycline (31.48%). The lowest resistance rate was seen towards gentamicin (1.85%) and amoxicillin (14.81%). C. coli isolates harboured the highest antimicrobial resistance rate against ampicillin (73.07%), ciprofloxacin (73.07%), erythromycin (65.38%) and chloramphenicol (50%). The lowest resistance rate was seen for amoxicillin (23.07%), azithromycin (30.76%) and tetracycline (34.61%). No resistance was found towards gentamicin. From a statistical seeing, significant differences were found between types of samples and Campylobacter antimicrobial resistance rate (p < 0.05).

TABLE 3.

Antimicrobial resistance of C. jejuni isolates of examined samples

| No. (%) of C. jejuni isolates harboured resistance against each antimicrobial agent | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples (No. of C. jejuni positive) | GM10 * | CIP5 | NA30 | TE30 | AM10 | AMC30 | E15 | AZM15 | CC2 | C30 |

| Chicken (42) | ‐ | 13 (30.95) | 7 (16.66) | 12 (28.57) | 15 (35.71) | 7 (16.66) | 18 (42.85) | 9 (21.42) | 9 (21.42) | 12 (28.57) |

| Turkey (7) | 1 (14.28) | 2 (28.57) | 3 (42.85) | 2 (28.57) | 3 (42.85) | ‐ | 2 (28.57) | 1 (14.28) | 2 (28.57) | 3 (42.85) |

| quebec (2) | ‐ | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | ‐ | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| Goose (1) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ‐ | 1 (100) | ‐ | 1 (100) | ‐ |

| Ostrich (2) | ‐ | 1 (50) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 (50) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 (50) |

| Total (54) | 1 (1.85) | 18 (33.33) | 12 (22.22) | 17 (31.48) | 21 (38.88) | 8 (14.81) | 23 (42.59) | 11 (20.37) | 13 (24.07) | 17 (31.48) |

| No. (%) of C. coli isolates harboured each virulence factor | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples (No. of C. coli positive) | GM10 | CIP5 | NA30 | TE30 | AM10 | AMC30 | E15 | AZM15 | CC2 | C30 |

| Chicken (19) | ‐ | 13 (68.42) | 7 (36.84) | 7 (36.84) | 13 (68.42) | 6 (31.57) | 15 (78.94) | 8 (42.10) | 9 (47.36) | 8 (42.10) |

| Turkey (5) | ‐ | 4 (80) | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | ‐ | 1 (20) | ‐ | 2 (40) | 4 (80) |

| Ostrich (2) | ‐ | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | ‐ | 1 (50) | ‐ | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| Total (26) | ‐ | 19 (73.07) | 12 (46.15) | 9 (34.61) | 19 (73.07) | 6 (23.07) | 17 (65.38) | 8 (30.76) | 12 (46.15) | 13 (50) |

G10: gentamicin (10 μg/disk), CIP5: ciprofloxacin (5 μg/disk), NA30: nalidixic acid (30 μg/disk), TE30: tetracycline (30 μg/disk), AM10: ampicillin (10 μg/disk), AMC30: amoxicillin (30 μg/disk), E15: erythromycin (15 μg/disk), AZM15: azithromycin (15 μg/disk), CC2: clindamycin (2 μg/disk), C30: chloramphenicol (30 μg/disk).

3.3. Distribution of antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes

Table 4 shows the antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes distribution among the C. jejuni isolates of examined samples. The most commonly detected antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes in the C. jejuni strains were aadE1 (44.44%), blaOXA‐61 (42.59%) and tet(O) (35.18%). Among the C. coli strains, cmeB (34.61%) and blaOXA‐61 (34.61%) were the most commonly detected antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes. From a statistical seeing, significant differences were found between types of samples and distribution of antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes (p < 0.05). C. jejuni strains harboured a higher and more diverse distribution of antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes than C. coli isolates (p < 0.05).

TABLE 4.

Antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes distribution among the C. jejuni isolates of examined samples

| No. (%) of C. jejuni isolates harboured each gene | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples (No. of C. jejuni positive) | aphA‐3‐1 | cmeB | tet(O) | blaOXA‐61 | aadE1 |

| Chicken (42) | 1 (2.38) | 10 (23.80) | 14 (33.33) | 17 (40.47) | 18 (42.85) |

| Turkey (7) | 1 (14.28) | 2 (28.57) | 2 (28.57) | 3 (42.85) | 3 (42.85) |

| quebec (2) | ‐ | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Goose (1) | ‐ | ‐ | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Ostrich (2) | ‐ | 1 (50) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Total (54) | 2 (3.70) | 15 (27.77) | 19 (35.18) | 23 (42.59) | 24 (44.44) |

| No. (%) of C. coli isolates harboured each gene | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples (No. of C. coli positive) | aphA‐3‐1 | cmeB | tet(O) | blaOXA‐61 | aadE1 |

| Chicken (19) | ‐ | 13 (68.42) | 9 (47.36) | 13 (68.42) | 14 (73.68) |

| Turkey (5) | ‐ | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | 3 (60) |

| Ostrich (2) | ‐ | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 ()100 | 1 (50) |

| Total (26) | ‐ | 19 (34.61) | 11 (42.30) | 19 (34.61) | 18 (69.23) |

3.4. Campylobacter virulence characters

Table 5 shows the virulence factors distribution among the C. jejuni isolates of examined samples. The most frequent virulence factors among the C. jejuni isolates were flaA (100%), ciaB (100%), racR (83.33%), dnaJ (81.48%), cdtB (81.48%), cdtC (79.62%) and cadF (74.07%). The lowest distribution rate was related to wlaN (9.25%), virbll (9.25%) and cgtB (24.07%) virulence factors. Additionally, the most frequent virulence factors among the C. coli isolates were flaA (100%), ciaB (100%), pldA (65.38%) and cadF (61.53%). The lowest distribution rate was related to cdtA (11.53%), cdtB (19.23%), cdtC (19.23%) and racR (19.23%) virulence factors. There were no positive results for the dnaJ, wlaN, virbll and ceuE virulence factors. From a statistical seeing, significant differences were found between types of samples and distribution of virulence factors (p < 0.05). C. jejuni strains harboured a higher and more diverse distribution of virulence factors than C. coli isolates (p < 0.05).

TABLE 5.

Virulence factors distribution among the C. jejuni and C. coli isolates of examined samples

| No. (%) of C. jejuni isolates harboured each virulence factor | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples (No. of C. jejuni positive) | racR | dnaJ | wlaN | virbll | cdtC | cdtB | cdtA | flaA | cadF | pldA | ciaB | ceuE | cgtB |

| Chicken (42) | 35 (83.33) | 35 (83.33) | 4 (9.52) | 4 (9.52) | 35 (83.33) | 35 (83.33) | 29 (69.04) | 42 (100) | 31 (73.80) | 24 (57.14) | 42 (100) | 16 (38.09) | 10 (23.80) |

| Turkey (7) | 5 (71.42) | 4 (57.14) | ‐ | ‐ | 3 (42.85) | 4 (57.14) | 4 (57.14) | 7 (100) | 5 (71.42) | 5 (71.42) | 7 (100) | 3 (42.85) | 1 (14.28) |

| quebec (2) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | ‐ | ‐ | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| Goose (1) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ‐ | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Ostrich (2) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | ‐ | ‐ | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | ‐ | 2 (100) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Total (54) | 45 (83.33) | 44 (81.48) | 5 (9.25) | 5 (9.25) | 43 (79.62) | 44 (81.48) | 37 (68.51) | 54 (100) | 40 (74.07) | 31 (57.40) | 54 (100) | 21 (38.88) | 13 (24.07) |

| No. (%) of C. coli isolates harboured each virulence factor | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples (No. of C. coli positive) | racR | dnaJ | wlaN | virbll | cdtC | cdtB | cdtA | flaA | cadF | pldA | ciaB | ceuE | cgtB |

| Chicken (19) | 3 (15.78) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3 (15.78) | 3 (15.78) | 3 (15.78) | 19 (100) | 12 (63.15) | 12 (63.15) | 19 (100) | ‐ | 8 (42.10) |

| Turkey (5) | 2 (40) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | ‐ | 5 (100) | 3 (60) | 3 (60) | 5 (100) | ‐ | 2 (40) |

| Ostrich (2) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | ‐ | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | ‐ | 1 (50) |

| Total (26) | 5 (19.23) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 5 (19.23) | 5 (19.23) | 3 (11.53) | 26 (100) | 16 (61.53) | 17 (65.38) | 26 (100) | ‐ | 11 (42.30) |

3.5. ERIC‐PCR molecular typing

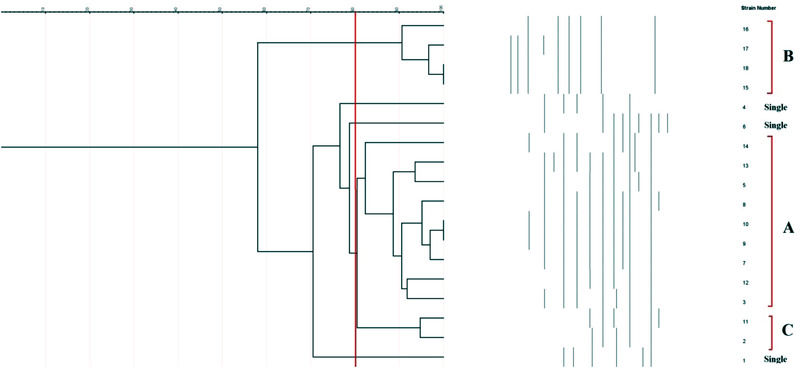

Figure 1 shows the ERIC‐PCR molecular typing of C. jejuni isolates of examined samples. Rendering a 80% similarity in the genetic bases of C. jejuni isolates, bacteria were classified into three different ERIC‐based types. Isolates No. 15 and 18 and also 9 and 10 had a 100% similarity and were classified with each other.

FIGURE 1.

ERIC‐PCR molecular typing of C. jejuni isolates of examined samples

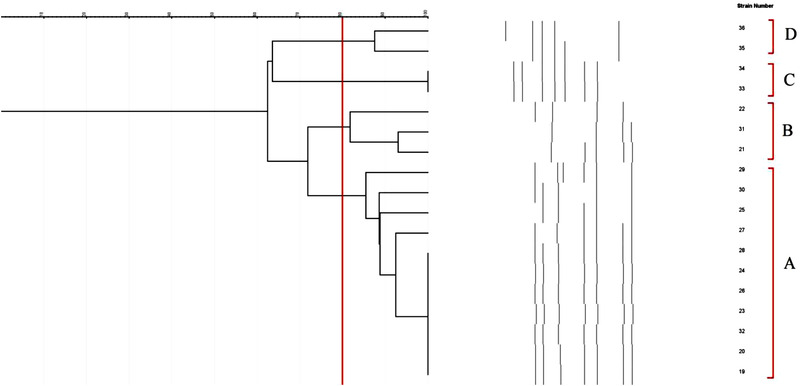

Figure 2 shows the ERIC‐PCR molecular typing of C. coli isolates of examined samples. Rendering an 80% similarity in the genetic bases of C. coli isolates, bacteria were classified into four different ERIC‐based types. Isolates No. 33 and 34 and also 19, 20, 23, 24, 26, 28 and 32 had a 100% similarity and were classified with each other.

FIGURE 2.

ERIC‐PCR molecular typing of C. coli isolates of examined samples

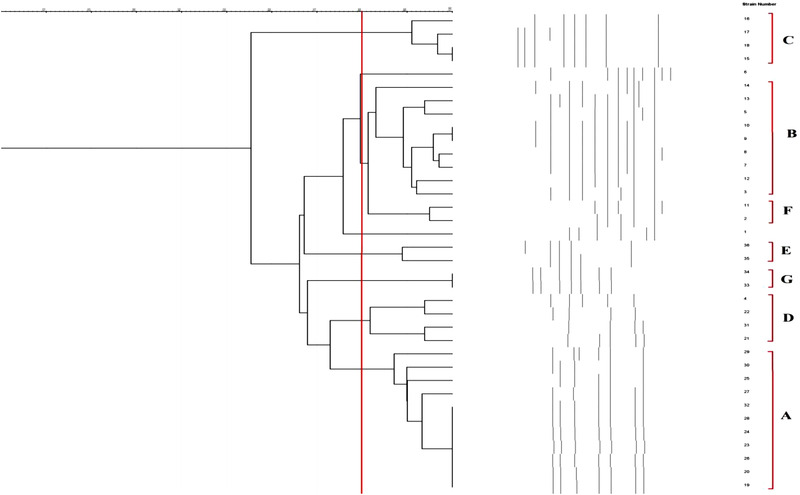

Figure 3 shows the molecular typing of all campylobacter isolates of examined samples. Rendering an 80% similarity in the genetic bases of C. coli isolates, bacteria were classified into 7 different ERIC‐based types. Isolates No .15 and 18, 9 and 10, 33 and 34 and finally and also 19, 20, 23, 24, 26, 28 and 32 had a 100% similarity and were classified with each other.

FIGURE 3.

ERIC‐PCR molecular typing of all Campylobacter isolates of examined samples

4. DISCUSSION

Targeted control of foodborne pathogens usually relies on the identification of sources and routes of transmission. Poultries can harbour Campylobacter and represent sources for human campylobacteriosis. All phases – from primary poultry production to the consumer – play an imperative portion in the Campylobacter transmission (Guirin et al., 2020).

The present survey was done to assess the prevalence, antimicrobial resistance properties, virulence characters and molecular typing of C. jejuni and C. coli strains isolated from raw chicken, turkey, ostrich, goose and quebec meat samples. C. jejuni and C. coli prevalence among the examined samples were 14.21% (54/380) and 6.84% (26/380), respectively. Variation in Campylobacter prevalence rate in poultry farms in European countries has been from 0.5% to 13% in Norway, Finland and Sweden and up to 80% in other countries (European Food Safety Authority, 2015). In Australia (Walker et al., 2019), Campylobacter spp. was detected in 90% of chicken raw meat and 73% of chicken offal samples. In Iran (Sabzmeydani et al., 2020), the total prevalence of C. jejuni and C. coli among the raw chicken, turkey, quail, quebec, duck, goose, pheasant and ostrich meat samples were 56.66% and 11.11%, 20% and 22.22%, 42.22% and 2.22%, 26.25% and 1.25%, 37.50% and 5%, 26.66% and 5%, 24% and 2% and finally, 100% and 0%, respectively, which supported our findings of the higher prevalence of C. jejuni and C. coli in examined samples. A similar survey conducted by Dabiri et al. (2014) reported that the Campylobacter prevalence among the chicken meat samples was 44%, in which C. jejuni and C. coli were identified in 79% and 21% of isolates, respectively. Di Giannatale et al. (2019) showed the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. among the poultry meat samples was 17.38% with the higher distribution of C. jejuni (58.45% of isolates) than C. coli (41.55% of isolates). Szosland‐Fałtyn et al. (2018) reported that the Campylobacter spp. the prevalence among raw turkey, chicken, goose and duck meat samples was 18.38%, 49.70%, 6.60% and 43.80%, respectively. They also showed that the prevalence of C. jejuni and C. coli among the raw chicken, turkey, goose and duck samples were 36.31% and 13.11%, 12.10% and 6.50%, 27.23% and 16.14% and 4.30% and 2.20%, respectively. Probable reasons for differences in the prevalence rate of Campylobacter spp. reported in diverse researches are differences in sampling time and location, method of sampling, types of samples, hygienic conditions of poultry farms and even different laboratory techniques. Chicken meat samples harboured the highest contamination rate, which partly may be due to their high number in the slaughter line and the possibility of transferring contamination between the carcasses. Instead, goose and quebec are usually slaughtered in very small numbers and separately from the chickens. As a result, the possibility of transmitting contamination between their carcasses is very low.

C. jejuni and C. coli isolate harboured a high resistance rate towards examined antimicrobial agents, particularly erythromycin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline. Unauthorised and improper antimicrobial administration, antimicrobials and disinfectant overuse and self‐medication with antimicrobials can be conceivable reasons for the high prevalence of antimicrobial resistance. Contact of the carcass surface with the slaughterhouse environment and contaminated staff can cause the transfer of antimicrobial‐resistant strains to the poultry carcass surface. High resistance of Campylobacter strains towards erythromycin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline was reported from Ghana (Karikari et al., 2017), South Africa (Igwaran & Okoh, 2020b), Italy (García‐Fernández et al., 2018) and the United States (Noormohamed & Fakhr, 2014). Shakir (2021) reported that resistance rate of Campylobacter spp. against erythromycin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole, amoxiclav, ampicillin, ceftriaxone and nalidixic acid antimicrobials were 50%, 88.80%, 100%, 27.70%, 30.50%, 80.50%, 27.70%, 80.50%, 50% and 100%, respectively. In a similar survey, Gharbi et al. (2018) stated that the resistance rate of C. jejuni and C. coli isolates of poultry meat samples towards ampicillin, amoxicillin/acid clavulanic, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, erythromycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol and gentamicin antimicrobial agents were 73.60% and 34.10%, 52.70% and 34.10%, 98.90% and 100%, 57.10% and 22%, 100% and 100%, 100% and 100%, 83.50% and 100% and finally 14.30% and 9.80%, respectively, which confirm our findings of the higher antibiotic resistance of C. jejuni isolates than that of C. coli. However, Giacomelli et al. (2014) reported that the C. jejuni strains isolated from poultry harboured more than 50% susceptibility towards gentamicin, apramycin, streptomycin, cefotaxime, amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, erythromycin, tilmicosin, tylosin, clindamycin and chloramphenicol. Reversely, they showed that majority of C. coli strains were resistant to streptomycin, cephalothin, cefotaxime, ampicillin, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, tilmicosin, tylosin, tetracycline, clindamycin and chloramphenicol. As a result, Giacomelli et al. (2014) report represents the contradiction in the results obtained in the present study in terms of higher resistance of C. coli than C. jejuni strains and high susceptibility of C. jejuni strains to antimicrobials that were highly resistant in our study. The reason for the difference in the extent and pattern of antimicrobial resistance in different studies is probably the availability or non‐availability of antimicrobials, the presence or absence of strict rules for prescribing antimicrobials and finally the difference in the personal opinion of veterinarians in prescribing antimicrobials. The prevalence of resistance to amoxicillin, azithromycin and clindamycin was relatively lower than that of other antibiotics. Amoxicillin, azithromycin and clindamycin are human‐prescribed antibiotics in the hospital and are not used in veterinary medicine. Thus, it is not surprising that C. coli than C. jejuni strains harboured a lower resistance rate against them. Another important finding was the high resistance rate of bacteria towards chloramphenicol (31.48% in C. jejuni and 50% in C. coli strains). Chloramphenicol is an illicit drug with a limited prescription. However, the use of this antibiotic illegally is done only in poultry farms in Iran. Thus, it is not surprising that a high resistance rate against this antimicrobial agent was reported. Similarly, high resistance of C. jejuni and C. coli strains against chloramphenicol was reported from Kenya (Nguyen et al., 2016), China (Li et al., 2017) and Iran (Fani et al., 2019).

Antimicrobial resistance among the C. coli than C. jejuni strains was associated with the presence of antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes, particularly cmeB, tet(O), blaOXA‐61 and aadE1 genes. Scarce data are available about the distribution of antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes in Campylobacter strains isolated from poultry meat samples. Tang et al. (2020) reported that the ermB antimicrobial resistance‐encoding gene was detected in 66.7% of C. jejuni and 39.6% of C. coli bacteria. They also found that the tet(O) gene was detected in all tetracycline‐resistant Campylobacter spp. Hull et al. (2021) showed that the majority of C. jejuni and C. coli bacteria isolated from poultry processing, food animals and retail meat in the United States harboured tet(O), aadE1, aph, cmeB and blaOXA resistance genes. A Chinese survey (Du et al., 2018) reported that Campylobacter spp. isolated from poultry meat samples carried tet(O) (98%), aadE (58.90%), ermB (20.50%) and aadE‐sat4‐aphA (6.60%) antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes. A similar report was done by Gharbi et al. (2018). They showed that the distribution of cmeB, tet(O), blaOXA‐61 and aphA‐3 resistance genes among the C. jejuni and C. coli strains isolated from broiler chickens in Tunisia were 80% and 100%, 100% and 80%, 81% and 93% and 0% and 0%, respectively. Some of the antibiotic‐resistant strains in our survey did not harbour related antimicrobial resistance encoding gene. This part of our survey is in agreement with those of Gharbi et al. (2018) and Marotta et al. (2019). These strains might harbour other genetic determinants conferring antimicrobial resistance. As we could detect both resistance to tetracycline and tet(O) gene, resistance to ciprofloxacin and fluoroquinolones and cmeB gene, resistance to β‐lactams (ampicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) and blaOXA‐61 gene, resistance to aminoglycosides and aphA‐3 and aadE1 genes, they would not be a good alternative for the campylobacteriosis treatment. Additionally, as the majority of Campylobacter strains harboured cmeB, tet(O), blaOXA‐61 and aadE1 genes, they might have a major function in mediating antimicrobial resistance against their specific classes of antimicrobials.

The virulence genes involved in motility (flaA), adhesion (cadF, dnaJ and racR), invasion (pldA, virB11 and ciaB), cytotoxin production (cdtA, cdtB and cdtC), lipoprotein encoding (ceuE) and GB syndrome (wlaN and cgtB) were the main genes detected in the Campylobacter spp. isolated from the examined poultry meat samples. As a result, consuming raw or uncooked poultry meat can lead to campylobacteriosis and subsequent severe complications. Thus, research on the Campylobacter virulence characteristics in food animals, particularly poultry meat, is essential for consumer safety. Rendering to our findings, flaA and ciaB were detected in all C. jejuni and C. coli isolates. Additionally, racR, dnaJ, cdtB, cdtC and cadF were detected in more than 50% of strains. In a similar survey, Fani et al. (2019) reported that all Campylobacter isolates were positive for cdtC, cdtB, cdtA and cadF virulence factors and the total distribution of pldA and cgtB were 65.40% and 15.40%, respectively. Gharbi et al. (2018) showed a significant relation between virulence characteristics and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter strains isolated from poultry meat samples. They reported that ampicillin‐resistant strains harboured racR and ciaB virulence factors, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid‐resistant ones harboured racR, cadF and ciaB, nalidixic acid‐resistant ones harboured racR, and chloramphenicol‐resistant ones harboured cadF and ceuE. However, this relationship between virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance was not determined in the present investigation, but some research indicated an in vitro increased invasion of resistant strains as compared to susceptible ones (Ghunaim et al., 2015). In keeping with this, some other researchers defined the tendency of susceptible strains to cause more severe infections than resistant ones (Feodoroff et al., 2009). Thus, additional studies should be conducted to explore more in‐depth the relationship between the pathogenic traits and the antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter strains. The high distribution of virulence factors was also reported in surveys conducted in the United States (Poudel et al., 2022), Poland (Wieczorek et al., 2018), Brazil (Takeuchi et al., 2022), Pakistan (Melo et al., 2013) and China (Zhang et al., 2016). We found a higher distribution of virulence factors among the C. jejuni isolates than C. coli bacteria. This finding may show that C. jejuni is much more common as a cause of human infections. This interpretation was supported by Melo et al. (2013) and Samad et al. (2019).

In the final section of the present survey, ERIC‐PCR was used for molecular typing of Campylobacter spp. according to findings; the majority of isolates had more than 80% genetic similarities and were classified in the same group. This finding may show their common source and route of transmission into the chicken meat samples. Additionally, high diversity was determined between C. jejuni and C. coli isolated from different raw poultry meat samples. This part of our findings was akin to those reported from South Africa (Igwaran & Okoh, 2020a), Egypt (Ahmed et al., 2015) and India (Milton et al., 2015).

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, virulent and antimicrobial‐resistant strains of C. jejuni and C. coli were isolated from chicken, ostrich, turkey, quebec and goose meat samples. Chicken and Turkey meat samples harboured the highest contamination rates. C. jejuni and C. coli isolates harboured a high resistance rate against erythromycin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol and tetracycline, which was accompanied by the high distribution of aadE1, blaOXA‐61 and tet(O) antimicrobial resistance‐encoding genes. These findings may show a change in the pattern of antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter isolates compared to previous studies and the need to find alternative antibiotics in the coming years. FlaA, ciaB, racR, dnaJ, cdtB, cdtC and cadF were found in the majority of isolates, which shows their high pathogenicity. Isolates that were classified in similar ERIC‐PCR‐based groups may have similar routes of transmission. The role of raw goose and quebec meat samples in the transmission of virulent, and antimicrobial‐resistant C. jejuni and C. coli to the human community was also determined. Further investigations should perform to compare the antibiotic resistance pattern, virulence gene profile and ERIC‐PCR typing of C. jejuni and C. coli strains isolated from poultry meat and human being. Additionally, there is a large demand to assess the relationship between virulence characters and antimicrobial resistance properties in C. jejuni and C. coli isolates.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

HM and AS carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the primers sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. MH and AS carried out the sampling and culture method. HM and AS participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The research was extracted from the PhD thesis in the field of microbiology and was ethically approved by the Council of Research of the Faculty of Basic Science, Shahrekord Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord, Iran (Consent Ref Number IR.IAU.SHK.REC.1400.042). Verification of this research project and the licenses related to sampling process were approved by the Prof. Hassan Momtaz (Approval Ref Number MIC201946).

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/vms3.944.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mohammad Zavarshani for his assistance in sample collection. This work was financially supported by the Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord Branch, Shahrekord, Iran.

Hadiyan, M. , Momtaz, H. , & Shakerian, A. (2022). Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, virulence gene profile and molecular typing of Campylobacter species isolated from poultry meat samples. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 8, 2482–2493. 10.1002/vms3.944

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article.

REFERENCES

- Abukhattab, S. , Taweel, H. , Awad, A. , Crump, L. , Vonaesch, P. , Zinsstag, J. , Hattendorf, J. , & Abu‐Rmeileh, N. M. (2022). Systematic review and meta‐analysis of integrated studies on salmonella and Campylobacter prevalence, serovar, and phenotyping and genetic of antimicrobial resistance in the Middle East – A one health perspective. Antibiotics, 11(5), 536.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, H. A. , El Hofy, F. I. , Ammar, A. M. , Abd El Tawab, A. A. , & Hefny, A. A. (2015). ERIC‐PCR genotyping of some Campylobacter jejuni isolates of chicken and human origin in Egypt. Vector‐Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 15(12), 713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audu, B. J. , Norval, S. , Bruno, L. , Meenakshi, R. , Marion, M. , & Forbes, K. J. (2022). Genomic diversity and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spp. from humans and livestock in Nigeria. Journal of Biomedical Science, 29(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilung, L. M. , Pui, C. F. , Su'ut, L. , & Apun, K. (2018). Evaluation of BOX‐PCR and ERIC‐PCR as molecular typing tools for pathogenic Leptospira. Disease Markers, 2018, 1351634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI . (2021). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty‐second informational supplement (pp. M100–M122) Villanova, PA: CLSI. [Google Scholar]

- Dabiri, H. , Aghamohammad, S. , Goudarzi, H. , Noori, M. , Ahmadi Hedayati, M. , & Ghoreyshiamiri, S. M. (2014). Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of Campylobacter species isolated from chicken and beef meat. International Journal of Enteric Pathogens, 2(2), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S. , Niwa, H. , & Itoh, K. (2003). Prevalence of 11 pathogenic genes of Campylobacter jejuni by PCR in strains isolated from humans, poultry meat and broiler and bovine faeces. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 52(4), 345–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis, M. , Soumet, C. , Rivoal, K. , Ermel, G. , Blivet, D. , Salvat, G. , & Colin, P. (1999). Development of am‐PCR assay for simultaneous identification of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli . Letters in Applied Microbiology, 29(6), 406–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giannatale, E. , Calistri, P. , Di Donato, G. , Decastelli, L. , Goffredo, E. , Adriano, D. , Mancini, M. E. , Galleggiante, A. , Neri, D. , Antoci, S. , Marfoglia, C. , Marotta, F. , Nuvoloni, R. , & Migliorati, G. (2019). Thermotolerant Campylobacter spp. in chicken and bovine meat in Italy: Prevalence, level of contamination and molecular characterization of isolates. PLoS One, 14(12), e0225957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y. , Wang, C. , Ye, Y. , Liu, Y. , Wang, A. , Li, Y. , Zhou, X. , Pan, H. , Zhang, J. , & Xu, X. (2018). Molecular identification of multidrug‐resistant Campylobacter species from diarrheal patients and poultry meat in Shanghai, China. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (EFSA and ECDC) (2017). The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food‐borne outbreaks in 2017. EFSA Journal, 16, e05500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Elhadidy, M. , Ali, M. M. , El‐Shibiny, A. , Miller, W. G. , Elkhatib, W. F. , Botteldoorn, N. , & Dierick, K. (2020). Antimicrobial resistance patterns and molecular resistance markers of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from human diarrheal cases. PLoS One, 15(1), e0227833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority, & European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . (2015). The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food‐borne outbreaks in 2013. EFSA Journal, 13(1), 3991. 10.2903/j.efsa.2015.3991 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fani, F. , Aminshahidi, M. , Firoozian, N. , & Rafaatpour, N. (2019). Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence‐associated genes of Campylobacter isolates from raw chicken meat in Shiraz, Iran. Iranian Journal of Veterinary Research, 20(4), 283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feodoroff, F. B. L. , Lauhio, A. R. , Sarna, S. J. , Hänninen, M. L. , & Rautelin, H. I. K. (2009). Severe diarrhoea caused by highly ciprofloxacin‐susceptible Campylobacter isolates. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 15(2), 188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Fernández, A. , Dionisi, A. M. , Arena, S. , Iglesias‐Torrens, Y. , Carattoli, A. , & Luzzi, I. (2018). Human campylobacteriosis in Italy: Emergence of multi‐drug resistance to ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and erythromycin. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharbi, M. , Béjaoui, A. , Ben Hamda, C. , Jouini, A. , Ghedira, K. , Zrelli, C. , Hamrouni, S. , Aouadhi, C. , Bessoussa, G. , Ghram, A. , & Maaroufi, A. (2018). Prevalence and antibiotic resistance patterns of Campylobacter spp. isolated from broiler chickens in the north of Tunisia. BioMed Research International, 2018, 7943786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghunaim, H. , Behnke, J. M. , Aigha, I. , Sharma, A. , Doiphode, S. H. , Deshmukh, A. , & Abu‐Madi, M. M. (2015). Analysis of resistance to antimicrobials and presence of virulence/stress response genes in Campylobacter isolates from patients with severe diarrhoea. PLoS One, 10(3), e0119268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomelli, M. , Salata, C. , Martini, M. , Montesissa, C. , & Piccirillo, A. (2014). Antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli from poultry in Italy. Microbial Drug Resistance, 20(2), 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirin, G. F. , Brusa, V. , Adriani, C. D. , & Leotta, G. A. (2020). Prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli from broilers at conventional and kosher abattoirs and retail stores. Revista Argentina de Microbiologia, 52(3), 217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakeem, M. J. , & Lu, X. (2021). Survival and control of Campylobacter in poultry production environment. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 10, 615049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, W. M. , Mekky, A. A. A. , & Enany, M. E. (2019). Review on some virulence factors associated with Campylobacter colonization and infection in poultry and human. American Journal of Biomedical Science & Research, 3, 460–463. [Google Scholar]

- Heras, J. , Domínguez, C. , Mata, E. , Pascual, V. , Lozano, C. , Torres, C. , & Zarazaga, M. (2015). GelJ – A tool for analyzing DNA fingerprint gel images. BMC Bioinformatics, 16(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlashwayo, D. F. , Sigaúque, B. , & Bila, C. G. (2020). Epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spp. in animals in sub‐Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Heliyon, 6(3), e03537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull, D. M. , Harrell, E. , van Vliet, A. H. , Correa, M. , & Thakur, S. (2021). Antimicrobial resistance and interspecies gene transfer in Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni isolated from food animals, poultry processing, and retail meat in North Carolina, 2018–2019. PLoS One, 16(2), e0246571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igwaran, A. , & Okoh, A. I. (2019). Human campylobacteriosis: A public health concern of global importance. Heliyon, 5(11), e02814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igwaran, A. , & Okoh, A. I. (2020a). Molecular determination of genetic diversity among Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from milk, water, and meat samples using enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR (ERIC‐PCR). Infection Ecology & Epidemiology, 10(1), 1830701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igwaran, A. , & Okoh, A. I. (2020b). Occurrence, virulence and antimicrobial resistance‐associated markers in Campylobacter species isolated from retail fresh milk and water samples in two district municipalities in the Eastern Cape Province, south Africa. Antibiotics, 9(7), 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10272‐1:2006 . (2006). Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs – Horizontal method for detection and enumeration of Campylobacter spp. – Part 1: Detection method. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. [Google Scholar]

- Karikari, A. B. , Obiri‐Danso, K. , Frimpong, E. H. , & Krogfelt, K. A. (2017). Antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter recovered from faeces and carcasses of healthy livestock. BioMed Research International, 2017, 4091856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Wang, Y. , Fu, Q. , Wang, Y. , Li, X. , Wu, C. , Shen, Z. , Zhang, Q. , Qin, P. , Shen, J. , & Xia, X. (2017). Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of high‐level chloramphenicol resistance in Campylobacter Jejuni . Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luangtongkum, T. , Jeon, B. , Han, J. , Plummer, P. , Logue, C. M. , & Zhang, Q. (2009). Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiology, 4(2), 189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marotta, F. , Garofolo, G. , Di Marcantonio, L. , Di Serafino, G. , Neri, D. , Romantini, R. , Sacchini, L. , Alessiani, A. , Di Donato, G. , Nuvoloni, R. , Janowicz, A. , & Di Giannatale, E. (2019). Correction: Antimicrobial resistance genotypes and phenotypes of Campylobacter jejuni isolated in Italy from humans, birds from wild and urban habitats, and poultry. PLoS One, 14(11), e0225231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, R. T. , Nalevaiko, P. C. , Mendonça, E. P. , Borges, L. W. , Fonseca, B. B. , Beletti, M. E. , & Rossi, D. A. (2013). Campylobacter jejuni strains isolated from chicken meat harbour several virulence factors and represent a potential risk to humans. Food Control, 33(1), 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Milton, A. A. P. , Rathore, R. S. , & Kumar, A. (2015). Genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli from different poultry sources and human by ERIC‐PCR. Journal oF Veterinary Public Health, 13(2), 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Myintzaw, P. , Jaiswal, A. K. , & Jaiswal, S. (2022). A review on campylobacteriosis associated with poultry meat consumption. Food Reviews International, 1–15. Doi: 10.1080/87559129.2021.1942487. [Google Scholar]

- Nachamkin, I. (2003). Campylobacter and arcobacter. In Murray P. R. (Ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology (pp. 902–914, 8th edn.) Washington, DC: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. N. M. , Hotzel, H. , Njeru, J. , Mwituria, J. , El‐Adawy, H. , Tomaso, H. , Neubauer, H. , & Hafez, H. M. (2016). Antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter isolates from small scale and backyard chicken in Kenya. Gut Pathogens, 8(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noormohamed, A. , & Fakhr, M. K. (2014). Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Campylobacter spp. in Oklahoma conventional and organic retail poultry. The Open Microbiology Journal, 8, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeng, A. S. , Rickard, H. , Sexton, M. , Pang, Y. , Peng, H. , & Barton, M. (2012). Antimicrobial susceptibilities and resistance genes in Campylobacter strains isolated from poultry and pigs in Australia. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 113(2), 294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Boto, D. , Herrera‐León, S. , Garcia‐Pena, F. J. , Abad‐Moreno, J. C. , & Echeita, M. A. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of quinolone, macrolide, and tetracycline resistance among Campylobacter isolates from initial stages of broiler production. Avian Pathology, 43(2), 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, S. , Li, T. , Chen, S. , Zhang, X. , Cheng, W. H. , Sukumaran, A. T. , Adhikari, P. , Kiess, A. S. , & Zhang, L. (2022). Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and molecular characterization of Campylobacter isolated from broilers and broiler meat raised without antibiotics. Microbiology Spectrum, 10(3), e0025122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, E. , Momtaz, H. , Ameri, M. , Ghasemian‐Safaei, H. , & Ali‐Kasemi, M. (2010). Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter species isolated from chicken carcasses during processing in Iran. Poultry Science, 89(5), 1015–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabzmeydani, A. , & Rahimi, E. , & Shakerian, A. (2020). Incidence and antibiotic resistance properties of Campylobacter species isolated from poultry meat. International Journal of Enteric Pathogen, 8(2), 60–65. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=892718 [Google Scholar]

- Samad, A. , Abbas, F. , Ahmed, Z. , Akbar, A. , Naeem, M. , Sadiq, M. B. , Ali, I. , Roomeela, S. , Bugti, F. S. , & Achakzai, S. K. (2019). Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and virulence of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from chicken meat. Journal of Food Safety, 39(2), e12600. [Google Scholar]

- Scallan Walter, E. J. , Crim, S. M. , Bruce, B. B. , & Griffin, P. M. (2020). Incidence of Campylobacter‐associated Guillain‐Barre syndrome estimated from health insurance data. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 17(1), 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakir, Z. M. (2021). Antibiotic resistance profile and multiple antibiotic resistance index of Campylobacter species isolated from poultry. Archives of Razi Institute, 76(6), 1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staji, H. , Birgani, S. F. , & Raeisian, B. (2018). Comparative clustering and genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni strains isolated from broiler and turkey feces by using RAPD‐PCR and ERIC‐PCR analysis. Annals of Microbiology, 68(11), 755–762. [Google Scholar]

- Szosland‐Fałtyn, A. N. N. A. , Bartodziejska, B. , Krolasik, J. , Paziak‐Domańska, B. E. A. T. A. , Korsak, D. , & Chmiela, M. (2018). The prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in polish poultry meat. Polish Journal of Microbiology, 67(1), 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, M. G. , de Melo, R. T. , Dumont, C. F. , Peixoto, J. L. M. , Ferreira, G. R. A. , Chueiri, M. C. , Iasbeck, J. R. , Timóteo, M. F. , de Araújo Brum, B. , & Rossi, D. A. (2022). Agents of campylobacteriosis in different meat matrices in Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M. , Zhou, Q. , Zhang, X. , Zhou, S. , Zhang, J. , Tang, X. , Lu, J. , & Gao, Y. (2020). Antibiotic resistance profiles and molecular mechanisms of Campylobacter from chicken and pig in China. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, 592496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L. J. , Wallace, R. L. , Smith, J. J. , Graham, T. , Saputra, T. , Symes, S. , Stylianopoulos, A. , Polkinghorne, B. G. , Kirk, M. D. , & Glass, K. (2019). Prevalence of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in retail chicken, beef, lamb, and pork products in three Australian states. Journal of Food Protection, 82(12), 2126–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, K. , Wołkowicz, T. , & Osek, J. (2018). Antimicrobial resistance and virulence‐associated traits of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from poultry food chain and humans with diarrhea. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. , Feye, K. M. , Shi, Z. , Pavlidis, H. O. , Kogut, M. , Ashworth, A. J. , & Ricke, S. C. (2019). A historical review on antibiotic resistance of foodborne Campylobacter . Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. , Luo, Q. , Chen, Y. , Li, T. , Wen, G. , Zhang, R. , Luo, L. , Lu, Q. , Ai, D. , Wang, H. , & Shao, H. (2016). Molecular epidemiology, virulence determinants and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spreading in retail chicken meat in Central China. Gut Pathogens, 8(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorman, T. , Heyndrickx, M. , Uzunović‐Kamberović, S. , & Možina, S. S. (2006). Genotyping of Campylobacter coli and C. jejuni from retail chicken meat and humans with campylobacteriosis in Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 110(1), 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article.