Abstract

Recently, we reported that silver(I) oxide mediated Koenigs-Knorr glycosylation reaction can be dramatically accelerated in the presence of catalytic acid additives. We have also investigated how well this reaction works in application to differentially protected galactosyl bromides. Reported herein is the stereoselective synthesis of α-galactosides with galactosyl chlorides as glycosyl donors. Chlorides are easily accessible, stable, and can be efficiently activated for glycosylation. In this application, the most favorable reactions conditions comprised cooperative Ag2SO4 and Bi(OTf)3 promoter system.

Keywords: Glycosylation, Synthesis, Methodology, Chlorides

1. Introduction

Since the first chemical glycosidations of glycosyl halides,1 scientists have persistently been trying to achieve highly stereocontrolled glycosylation.2 Early work by Helferich, Zemplen, and others have brought up the challenge of 1,2-cis glycosylation,3-6 and the Lemieux group developed the first practical solution.7-9 More recent methods rely on other glycosyl donors in combination with stereodirecting effects including steric factors,10-11 remote participation,12-16 chiral auxiliaries,17-20 H-bond-mediated aglycone delivery (HAD), 21 modification of catalysts,22-24 or glycosylation modulators.25-26 Nevertheless, the challenge of completely stereocontrolled 1,2-cis glycosylation remains.2 Recently, our group reported a powerful method for stereocontrolled α-galactosylation.27 This method was based on cooperative catalytic system that was first introduced for glycosidation of bromides28,29 and subsequently expanded to glycosyl chlorides.30 An acid (or a Lewis acid) and a silver salt applied together lead to a drastically increased reaction rates and product yields. However, those reactions were non-stereoselective, and our subsequent report on α-galactosylation was the first attempt to stereocontrol cooperatively catalyzed reactions. It was observed that combined effects of the cooperative catalysis and remote participation of benzoyl groups offer a powerful method for stereocontrolled α-galactosylation.27 Inspired by recent studies with glycosyl chlorides by Ye31 and Jacobsen32 reported herein is the investigation of cooperatively catalyzed glycosidation of partially benzoylated galactosyl chlorides. Terminology used herein refers to “glycosylation of the acceptor with the donor” or “glycosidation of the donor with the acceptor.” The development of new reactions that will offer enhanced capabilities for obtaining complex biomarkers and pharmaceuticals with enhanced stereoselectivity and purity is at the heart of this study.

2. Results and discussion

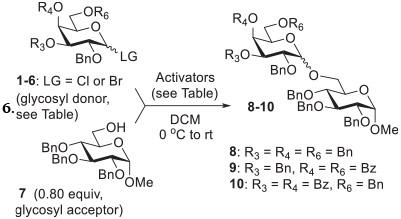

In our previous report we showed that galactosylation of perbenzylated galactosyl bromide 1 with glycosyl acceptor 7 in the presence of Ag2O and TfOH afforded disaccharide 8 in a good yield of 71% albeit with no stereoselectivity (entry 1, Table 1).27 After careful refinement of the reaction conditions, we demonstrated that partially benzoylated galactosyl bromides 2 and 3 are capable of achieving highly stereocontrolled α-galactosylations. Thus, when glycosyl donors 2 or 3 were activated in the presence of Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv) and TfOH (0.2 equiv) the respective disaccharides 9 and 10 were obtained in 93–96% yields with practically complete α-selectivity (entries 2 and 3).27 When essentially the same reaction conditions were applied to the activation of per-benzoylated galactosyl chloride donor 433 only a very sluggish reaction with acceptor 734 was observed, and it failed to produce useful results from the preparative perspective, even after 24 h. This is probably due to a relatively lower reactivity of glycosyl chlorides versus their bromide counterparts.1 When the activation system was fortified by increasing the amount of TfOH to 0.5 equiv, a smooth and practically complete galactosylation was achieved. Disaccharide 835 was smoothly produced in 96% yield in 2 h, albeit with poor stereoselectivity (α/β = 1.1/1, entry 4). This result in terms of stereoselectivity was on a par with other recent glycosidations of donor 4 recently reported by our group. Thus, activation of 4 with Ag2O/TfOH (0.5 equiv each),30 FeCl3 (0.2 equiv),36 or Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv)33 produced disaccharide 8 in 99%, 67%, or 97% yield, respectively, all with poor α/β-selectivity (from 1.2/1 to 1/1.2, entries 5–7).

Table 1.

Known reactions with galactosyl halide donors 1–4 and optimization of the reaction conditions with galactosyl chlorides 5 and 6.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Donor | Activators, time | Product, yield, α/β ratio |

| 127 |

|

Ag2O (3.0 equiv), TMSOTf (0.25 equiv), 15 min | 8, 71%, 1.0:1 |

| 227 |

|

Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), TfOH (0.2 equiv), 0.5 h | 9, 93%, 33:1 |

| 327 |

|

Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), TfOH (0.2 equiv), 2 h | 10, 96%, α-only |

| 4 |

|

Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), TfOH (0.5 equiv),a 2 h | 8, 92%, 1.1:1 |

| 530 | 4 | Ag2O (0.5 equiv), TfOH (0.5 equiv), 0.5 h | 8, 99%, 1.2:1 |

| 636 | 4 | FeCl3 (0.2 equiv), 2 h | 8, 67%, 1.1:1 |

| 733 | 4 | Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv), 15 min | 8, 97%, 1:1.2 |

| 8 |

|

Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), TfOH (0.5 equiv), 0.5 h | 9, 90%, 11:1 |

| 9 | 5 | Ag2O (1.0 equiv), TfOH (0.5 equiv), 1 h | 9, 95%, 7.7:1 |

| 10 | 5 | Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), BF3-Et2O (0.5 equiv), 16 h | 9, 80%, 9.0:1 |

| 11 | 5 | Ag2O (1.0 equiv), BF3-Et2O (0.5 equiv), 16 h | 9, 80%, 2.0:1 |

| 12 | 5 | AgOTf (1.5 equiv), 16 h | 9, 82%, 4.0:1 |

| 13 | 5 | Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv), 16 h | 9, 86%, 9.1:1 |

| 14 | 5 | Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv), 16 h | 9, 86%, 9.1:1 |

| 15 | 5 | Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv), 1 h | 9, 96%, 7.7:1 |

| 16 | 5 | Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv), 1 h | 9, 94%, 10:1 |

| 17 |

|

Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), TfOH (0.5 equiv), 0.5 h | 10, 91%, 10:1 |

| 18 | 6 | Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv), 16 h | 10, 77%, 13:1 |

| 19 | 6 | Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv), 4.5 h | 10, 74%, 7.7:1 |

| 20 | 6 | Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv), Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv), 3 h | 10, 96%, 17:1 |

| 21 | 6 | Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv), 3 h | 10, 70%, 10:1 |

– Reaction with 0.2 equiv of TfOH was sluggish and would not go to completion even after 24 h.

To investigate the effect of the remote benzoyl groups on the stereoselectivity of the cooperatively catalyzed galactosylations, we obtained 4,6-di-O-benzoylated galactosyl chloride donor 537 and 3,4-di-O-benzoylated galactosyl chloride donor 6. When chloride 5 was reacted with acceptor 7 in the presence of Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv) and TfOH (0.5 equiv) disaccharide 927 was obtained in 90% yield in 30 min. Most importantly, a very promising α-selectivity was achieved (α/β = 11.1/1, entry 8). To elaborate upon this encouraging result, we wondered whether further refinement of the reaction conditions would lead to even higher stereoselectivity. However, these attempts did not lead to anticipated gains. Thus, activation of 5 with Ag2O (1.0 equiv) and TfOH (0.5 equiv) resulted in formation of disaccharide 9 in a high yield of 95% in 1 h, albeit with reduced stereoselectivity (α/β = 7.7/1, entry 9). Using BF3-Et2O (0.5 equiv) additive instead of TfOH led to a reduced stereoselectivity. While still commendable stereoselectivity was achieved in Ag2SO4/BF3-Et2O promoted glycosylation (α/β = 9.0/1, entry 10), the stereoselectivity dropped dramatically when the activation was performed in the presence of Ag2O/BF3-Et2O (α/β = 2.0/1, entry 11). In both cases, disaccharide 9 was obtained in 80% yield in 16 h. The latter result was indicative of the counter anion effect on stereoselectivity because the best results have been obtained in the presence of sulfates and/or triflates, whereas only poor stereoselectivity was observed in their absence. However, a test reaction with AgOTf led to a sluggish reaction to produce disaccharide 9 in a respectable yield of 82% in 16 h, albeit unimpressive stereoselectivity (α/β = 4.0/1, entry 12).

Subsequent screening of other Lewis acidic triflate salt additives revealed that Bi(OTf)3 shows a great potential for subsequent investigation. Thus, when glycosylation between 5 and 7 was performed in the presence Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv) and Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv), disaccharide 9 was obtained in 86% yield in 16 h with commendable stereoselectivity (α/β = 9.1/1, entry 13). Somewhat surprisingly, the identical result was obtained when the reaction was performed in the absence of the silver salt, in the presence of Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv) alone (entry 14). In an effort to expedite these reactions we investigated whether the increase of Bi(OTf)3 to 0.5 equiv would be of benefit. When donor 5 was activated with Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv) and Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv), disaccharide 9 was obtained in 96% in 1 h, however the stereoselectivity was slightly reduced (α/β = 7.7/1, entry 15). A similar activation with Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv) in the absence of silver sulfate, disaccharide 9 was obtained in 94% in 1 h with an improved stereoselectivity (α/β = 10/1, entry 16).

With this set of results, we have also investigated 3,4-di-O-benzoylated galactosyl donor 6 in reactions with glycosyl acceptor 7. When donor 6 was glycosidated in the presence of Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv) and TfOH (0.5 equiv) disaccharide 10 was obtained in 91% yield in 30 min and with good stereoselectivity (α/β = 10/1, entry 17). When TfOH was replaced with Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv), even higher stereoselectivity was achieved (α/β = 13/1, entry 18). However, in this case the reaction was slow, and disaccharide 10 was obtained in a reduced yield of 77% in 16 h. When a similar reaction was performed without Ag2SO4, in the presence of Bi(OTf)3 (0.35 equiv) only, both lower yield of 74% and reduced stereoselectivity were observed (α/β = 7.7/1, entry 19). By increasing the amount of bismuth additive in silver(I)-promoted reactions, we have managed to achieve the best balance of the reaction rate, the product yield and stereoselectivity. Thus, when chloride 6 was activated in the presence of Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv) and Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv) disaccharide 10 was obtained in 96% yield in 3 h with excellent α-selectivity (α/β = 17/1, entry 20). In comparison, the reaction in the presence of Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv) alone produced disaccharide 10 in a reduced yield of 70% and with lower stereoselectivity (α/β = 10/1, entry 21).

While reactions in the presence of silver(I) or in the presence of bismuth(III) gave comparable results, we anticipate that the mechanistic pathways of these activations are different. As proposed in our previous studies of the cooperatively catalyzed reactions, 28-30 after initial interaction of the glycosyl chloride donor with silver(I) salt (Ag2O or Ag2SO4), the resulting species A produce a strongly ionized species B due to the action of TfOH (Scheme 1A). This reaction pathway would be followed in the presence of other protic acids or Lewis acids. While we do not yet have the explicit evidence, we believe that Bi(OTf)3 acts similarly if used cooperatively with silver(I) salts. Intermediate B then rapidly dissociates, and this step is driven by the irreversible formation of AgCl. Also produced at this stage is XOH (AgOH or AgHSO4). The resulting oxacarbenium intermediate C undergoes subsequent nucleophilic attack by a glycosyl acceptor (ROH). Since intermediate C exists in a flattened half-chair conformation, the nucleophilic attack may be poorly stereoselective if no strereocontrolling factors are employed. At this step, regeneration of TfOH used in catalytic cycle takes place.

Scheme 1.

Possible mechanistic pathways for the activation of glycosyl chlorides (A) in the presence of a silver salt and (B) in the presence of a bismuth salt.

In the case of Bi(OTf)3 used alone, the reaction follows a traditional Lewis acid-catalyzed mechanistic pathway depicted in Scheme 1B. In this case, bismuth(III)-mediated leaving group departure (D) results in the formation of oxacarbenium ion C or a similar intermediate. At this step, the formation of BiCl(OTf)2 takes place, which becomes available to carry out the next catalytic cycle. Our previous studies showed that also BiCl2OTf formed after the next catalytic cycle is capable of activating the leaving group because 0.35 equiv is sufficient to conduct glycosylation.33 Oxacarbenium intermediate C then undergoes the nucleophilic attack by the glycosyl acceptor (ROH). Again, if no stereocontrolling means are incorporated this nucleophilic attack would be non-stereoselective.

Having achieved excellent results with the primary glycosyl acceptor 7 we extended our experimentation to a series of secondary glycosyl acceptors 11–1334 and electronically deactivated primary acceptor 14 38 (Figure 1). Results of reactions of galactosyl donors 5 and 6 with different glycosyl acceptors 11–14 are listed in Table 2. Glycosylation between donor 5 and 2-OH acceptor 11 in the presence of Ag2SO4 (1.5 equiv) and Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv) gave disaccharide 15 in 86% yield with complete α-selectivity (entry 1). When a similar reaction was conducted in the presence of Bi(OTf)3 (0.5 equiv) alone, disaccharide 15 was obtained in 77% with excellent stereoselectivity (α/β = 25/1, entry 1). Both reactions required 1 h to complete. When donor 6 was reacted with 2-OH acceptor 11, both reaction conditions gave identical results for the formation of disaccharide 16 (89% yield, α-only, entry 2). These reaction conditions were slower and required 16 h to complete.

Figure 1.

Standard glycosyl acceptors 11–14 for broadening the scope of α-galactosylation.

Table 2.

Expanding the scope of glycosidation of chloride donors 5 and 6 with acceptors

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Reactants | Product, yield, α/β ratio, time |

| 1 | 5 + 11 |

|

| 2 | 6 + 11 |

|

| 3 | 5 + 12 |

|

| 4 | 6 + 12 |

|

| 5 | 5 + 13 |

|

| 6 | 6 + 13 |

|

| 7 | 5 + 14 |

|

| 8 | 6 + 14 |

|

Glycosidation of donor 5 with 3-OH acceptor 12 resulted in the formation of disaccharide 17. A higher yield of 84% (versus 70%) was obtained under cooperative catalysis conditions. High α-selectivities were achieved in both glycosylations (α/β = 20–25/1, entry 3). Glycosidation of donor 6 with 3-OH acceptor 12 resulted in the formation of disaccharide 18. Also in this case, a higher yield of 77% (versus 72%) was achieved under cooperative catalysis conditions. High α-selectivities were obtained in both glycosylations (α/β = 16–20/1, entry 4). Glycosidation of donor 5 with unreactive 4-OH acceptor 13 were slower, and these lower reaction rates translated in modest yields of disaccharide 19. In this case, a higher yield of 43% (versus 26%) was obtained in the absence of Ag2SO4. Excellent α-selectivities were achieved in both glycosylations (α/β = 33/1 to α-only, entry 5). Glycosidation of donor 6 with 4-OH acceptor 13 was somewhat faster, and disaccharide 20 was obtained in 50–53% yield (α/β = 12.5–14/1, entry 6).

Glycosidation of donor 5 with electronically deactivated 6-OH acceptor 14 resulted in the formation of disaccharide 21. A higher yield of 95% (versus 88%) was obtained under cooperative catalysis conditions. Good α-selectivities were achieved in both glycosylations (α/β = 9–12.5/1, entry 7). Glycosidation of donor 6 with acceptor 14 produced disaccharide 22. While each reaction conditions gave comparable yields of 88–90%, a drastic difference in stereoselectivity was observed. Complete α-selectivity were obtained in the cooperatively catalyzed glycosylation, whereas only a moderate stereoselectivity was achieved in the absence of Ag2SO4 (α/β = 5.0/1, entry 8). All reactions with glycosyl acceptor 14 completed in under 2 h.

3. Conclusions

Building upon our previous reports that silver(I) oxide mediated Koenigs-Knorr glycosylation reaction can be dramatically accelerated in the presence of catalytic acid additives, reported herein is the stereoselective synthesis of α-galactosides with galactosyl chlorides as glycosyl donors. The donor choice was driven by the accessibility, relative stability of glycosyl chlorides. In this application, the most favorable reactions conditions comprised cooperative Ag2SO4 and Bi(OTf)3 promoter system. Bi(OTf)3 catalyst can activate chlorides and bromides without silver(I), but in a majority of reactions, lower yields and stereoselectivities have been observed. The mechanistic pathways by which these different promoter/catalyst systems operate have been proposed, and our future work dedicated to tackling the key differences in the reaction pathways is currently underway in our laboratory.

We believe that enhanced capabilities for synthesis will offer a more streamlined access to complex therapeutics and diagnostics. Among potential targets are various families of microbial glycans, glycophingolipids, and biomarkers.39-42 Among these, Staphylococcus aureus, type 5 and 8, one of the most frequent causes of infections in newborns, surgical patients, and immunocompromised individuals, have multiple 1,2-cis-d- and l-galacto-configured units.43 All of the following members of globosides have 1,2-cis galactosyl linkage: Gb3 that is overexpressed in a number of cancerous cells,44-45 Gb4 that is enhanced in vascular endothelial cells undergoing an inflammatory response,46 Stage-Specific Embryonic Antigens SSEA-3 and −4 that are found on the surface of human embryonic stem cells47 and various tumors,48 along with Globo-H that is a target antigen for breast and prostate cancer vaccine development.49.

4. Experimental

General.

The reactions were performed using commercially available reagents. CH2Cl2 used for reactions was distilled from CaH2 prior to the application. Other ACS-grade solvents used for reactions were purified and dried according to standard procedures. Prior to the initial application, silver salts were co-evaporated with toluene (×2), dried in vacuo in the dark. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh); reactions were monitored using Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) on Kieselgel 60 F254. TLC was examined under UV light and by charring with 10% sulfuric acid in methanol. Solvents were removed under reduced pressure at < 40 °C. Molecular sieves (3 Å) used for reactions were crushed and activated under vacuum for 8 h at 390 °C in the first instance, and then for 2–3 h at 390 °C directly prior to application. Optical rotations were measured by a Jasco P2000 polarimeter. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 at 300 and 400 MHz, respectively. 1H NMR was calibrated to tetramethylsilane (TMS, δH = 0 ppm) in CDCl3. 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 at 100 MHz. 13C NMR was calibrated to the central signal of CDCl3 (δC = 77.00 ppm) in CDCl3. HRMS analysis was performed using an Agilent 6230 ESI TOF LC/MS mass spectrometer.

4.1. Synthesis of glycosyl donors

2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl chloride (4) was synthesized as previously reported33 and its analytical data were in accordance with those reported previously. 33.

4,6-Di-O-benzoyl-2,3-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl chloride (5) was synthesized as previously reported37 and its analytical data were in accordance with those reported previously.37.

3,4-Di-O-benzoyl-2,6-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl chloride (6). N-Bromosuccinimide (0.22 g, 1.22 mmol, 1.5 equiv) was added to a solution of ethyl 3,4-di-O-benzoyl-2,6-di-O-benzyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (23,27 0.50 g, 0.82 mmol) in acetone (30 mL), and the resulting mixture was stirred for 10 min at rt. After that, H2O (3 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at rt. The volatiles were then removed under reduced pressure, the residue was diluted with CH2Cl2 (30 mL) and washed with sat. aq. NaHCO3 (10 mL) and water (2 × 10 mL). The organic phase was separated, dried with MgSO4, concentrated under reduced pressure, and dried in vacuo for 2 h. The resulting residue was dissolved in 1,2-DCE (15 mL), DMF (0.75 mL) was added, and the resulting solution was cooled to 0 °C. SOCl2 (0.11 mL, 2.0 equiv) was added, and the resulting mixture was stirred for 1 h at 0 °C. After that, the volatiles were removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by passing through a pad of silica gel (ethyl acetate – hexane, 1/1, isocratic elution, 60 mL) to afford the title compound as a clear syrup (0.39 g, 0.66 mmol, 83%). Analytical data for α-6: Rf = 0.60 (EtOAc/hexanes, 3/7, v/v); 1H NMR (CDCl3 at 400 MHz): δ 7.88 (d, 2H, aromatic), 7.81 (d, 2H, aromatic), 7.61 (dd, 1H, aromatic), 7.53–7.41 (m, 3H, aromatic), 7.31 (dd, 2H, aromatic), 7.25–7.16 (m, 10H, aromatic), 6.26 (d, 1H, J1,2 = 4.0 Hz, H-1), 5.92 (dd, 1H, J4,5 = 1.0 Hz, H-4), 5.76 (dd, 1H, J3,4 = 4.0 Hz, H-3), 4.71–4.62 (m, 3H, H-5, 2 × CHPh), 4.45 (dd, 2H, CH2Ph), 4.26 (dd, 1H, J2,3 = 8.0 Hz, H-2), 3.63–3.51 (m, 2H, H-6a, 6b) ppm; 13C NMR (CDCl3 at 100 MHz): δ 165.3, 165.2, 137.3, 137.0, 133.3, 133.0, 129.7 (x3), 129.6, 129.5 (x3), 129.4 (x3), 128.6, 128.5 (x2), 128.3, 128.2 (x2), 128.1, 128.0, 127.8, 127.7, 93.3, 73.4, 73.3, 72.2, 70.8, 69.9, 68.9, 67.5 ppm; HR-FAB MS [C34H31ClO7Na]+ calcd for 609.1558, found 609.1634.

4.2. Synthesis of disaccharides

General Procedure.

A mixture containing a galactosyl chloride (0.051–0.053 mmol), a glycosyl acceptor (0.041–0.042 mmol, 0.8 equiv), and activated molecular sieves (3 Å, 90 mg) in freshly distilled CH2Cl2 (1.0 mL) was stirred under argon for 1 h at rt. The resulting mixture was cooled to 0 °C, a silver salt (0.05–0.076, if applicable) and an acidic additive or promoter (0.017–0.025) were added. The external cooling was then removed, the resulting mixture was allowed to warm to rt and stirred for the time specified in tables. Afterwards, the solids were filtered off through a pad of Celite and rinsed successively with CH2Cl2. The combined filtrate (~25 mL) was washed with saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate (10 mL) and water (2 × 10 mL). The organic phase was separated, dried with sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (ethyl acetate-hexane or ethyl acetate-toluene gradient elution) to yield the corresponding disaccharide derivative in a yield and with a stereoselectivity specified in tables. The anomeric ratio (or anomeric purity) was determined by comparison of integration values for the relevant signals in the 1H NMR spectra.

Methyl 6-O-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-2,3, 4-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (8) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 4 and acceptor 7 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 8 was consistent with that reported previously.35

Methyl 6-O-(4,6-di-O-benzoyl-2,3-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-2,3,4-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (9) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 5 and acceptor 7 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 9 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 6-O-(3,4-di-O-benzoyl-2,6-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-2,3,4-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (10) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 6 and acceptor 7 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 10 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 2-O-(4,6-di-O-benzoyl-2,3-di-O-benzyl-α-d-galactopyranosyl)-3,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (15) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 5 and acceptor 11 by the general glycosylation method The analytical data for 15 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 2-O-(3,4-di-O-benzoyl-2,6-di-O-benzyl-α-d-galactopyranosyl)-3,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (16) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 6 and acceptor 11 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 16 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 3-O-(4,6-di-O-benzoyl-2,3-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-2,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (17) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 5 and acceptor 12 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 17 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 3-O-(3,4-di-O-benzoyl-2,6-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-2,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (18) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 6 and acceptor 12 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 18 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 4-O-(4,6-di-O-benzoyl-2,3-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-2,3,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (19) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 5 and acceptor 13 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 19 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 4-O-(3,4-di-O-benzoyl-2,6-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-2,3,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (20) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 6 and acceptor 13 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 20 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 2,3,4-tri-O-benzoyl-6-O-(4,6-di-O-benzoyl-2,3-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-α-d-glucopyranoside (21) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 5 and acceptor 14 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 21 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Methyl 2,3,4-tri-O-benzoyl-6-O-(3,4-di-O-benzoyl-2,6-di-O-benzyl-α/β-d-galactopyranosyl)-α-d-glucopyranoside (22) was obtained as a colorless amorphous solid from galactosyl chloride donor 6 and acceptor 14 by the general glycosylation method. The analytical data for 22 was consistent with that reported previously.27

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the National Institute of General Medical Sciences for support of this work (GM111835).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

NMR spectra for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2022.117031.

References

- 1.Singh Y, Geringer S, Demchenko AV. Synthesis and glycosidation of anomeric halides: evolution from early studies to modern methods of the 21st century. Chem Rev. 2022;122:11701–11758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nigudkar SS, Demchenko AV. Stereocontrolled 1,2-cis glycosylation as the driving force of progress in synthetic carbohydrate chemistry. Chem Sci. 2015;6:2687–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helferich B, Bredereck H. Zuckersynthesen. VIII. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1928;465: 166–184. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zemplén G, Pacsu E. Über die Verseifung acetylierter Zucker und verwandter Substanzen. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1929;62:1613–1614. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zemplen G, Gerecs A. Action of mercury salts on acetohalogenosugars. IV. Direct preparation of alkyl biosides of the α -series. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1930;63B: 2720–2729. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helferich B, Zirner J. Synthesis of tetra-O-acetyhexoses with a free 2-hydroxyl group. Synthesis of disaccharides. Chem Ber. 1962;95:2604–2611. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemieux RU, Hendriks KB, Stick RV, James K. Halide ion catalyzed glycosylation reactions. Syntheses of α-linked disaccharides. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:4056–4062. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemieux RU, Driguez H. The chemical synthesis of 2-O-(α-L-fucopyranosyl)-3-O-(α-D-galactopyranosyl)-D-galactose. The terminal structure of blood-group B antigenic determinant. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:4069–4075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemieux RU, Driguez H. Chemical synthesis of 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-4-O-(. alpha.-L-fucopyranosyl)-3-O-(. beta.-D-galactopyranosyl)-D-glucose. Lewis a blood-group antigenic determinant. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:4063–4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imamura A, Ando H, Korogi S, et al. Di-tert-butylsilylene (DTBS) group-directed α-selective galactosylation unaffected by C-2 participating functionalities. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:6725–6728. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imamura A, Ando H, Ishida H, Kiso M. Di-tert-butylsilylene-Directed a-Selective Synthesis of 4-Methylumbelliferyl T-Antigen. Org Lett. 2005;7:4415–4418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demchenko AV, Rousson E, Boons GJ. Stereoselective 1,2-cis-galactosylation assisted by remote neighboring group participation and solvent effects. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:6523–6526. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalikanda J, Li Z. Study of the stereoselectivity of 2-azido-2-deoxygalactosyl donors: remote protecting group effects and temperature dependency. J Org Chem. 2011;76: 5207–5218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komarova BS, Tsvetkov YE, Nifantiev NE. Design of α-Selective Glycopyranosyl Donors Relying on Remote Anchimeric Assistance. Chem. Record 2016;16:488–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Zhou S, Wang X, Zhang H, Guo Z, Gao J. A new method for α-specific glucosylation and its application to the one-pot synthesis of a branched α-glucan. Org Chem Front. 2019;6:762–772. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H, Hansen T, Zhou SY, et al. Dual-Participation Protecting Group Solves the Anomeric Stereocontrol Problems in Glycosylation Reactions. Org Lett. 2019;21: 8713–8717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JH, Yang H, Park J, Boons GJ. A general strategy for stereoselective glycosylations. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12090–12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JH, Yang H, Khot V, Whitfield D, Boons GJ. Stereoselective glycosylations using (R)- or (S)-(ethoxycarbonyl)benzyl chiral auxiliaries at C-2 of glycopyranosyl donors. Eur J Org Chem. 2006;5007–5028. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boltje TJ, Kim JH, Park J, Boons GJ. Chiral-auxiliary-mediated 1,2-cis-glycosylations for the solid-supported synthesis of a biologically important branched α-glucan. Nat Chem. 2010;2:552–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mensink RA, Boltje TJ. Advances in Stereoselective 1,2-cis Glycosylation using C-2 Auxiliaries. Chem Eur J. 2017;23:17637–17653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasomanee JP, Demchenko AV. The effect of remote picolinyl and picoloyl substituents on the stereoselectivity of chemical glycosylation. J Am Chem Soc. 2012; 134:20097–20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mensah EA, Yu F, Nguyen HM. Nickel-catalyzed stereoselective glycosylation with C (2)-N-substituted benzylidene D-glucosamine and galactosamine trichloroacetimidates for the formation of 1,2-cis-2-amino glycosides. Applications to the synthesis of heparin disaccharides, GPI anchor pseudodisaccharides, and -GalNAc. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14288–14302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sletten ET, Tu Y-J, Schlegel HB, Nguyen HM. Are Brønsted Acids the True Promoter of Metal-Triflate-Catalyzed Glycosylations? A Mechanistic Probe into 1, 2-Cis-Aminoglycoside Formation by Nickel Triflate. ACS Catal. 2019;9:2110–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradshaw G, Colgan A, Allen N, et al. Stereoselective organocatalyzed glycosylations–thiouracil, thioureas and monothiophthalimide act as Brønsted acid catalysts at low loadings. Chem Sci. 2019;10:508–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park J, Kawatkar S, Kim JH, Boons GJ. Stereoselective glycosylations of 2-azido-2-deoxy-glucosides using intermediate sulfonium ions. Org Lett. 2007;9:1959–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu SR, Lai YH, Chen JH, Liu CY, Mong KK. Dimethylformamide: an unusual glycosylation modulator. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:7315–7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shadrick M, Singh Y, Demchenko AV. Stereocontrolled α-galactosylation under cooperative catalysis. J Org Chem. 2020;85:15936–15944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh Y, Demchenko AV. Koenigs-Knorr glycosylation reaction catalyzed by trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate. Chem Eur J. 2019;25:1461–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh Y, Demchenko AV. Defining the scope of the acid-catalyzed glycosidation of glycosyl bromides. Chem Eur J. 2020;26:1042–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geringer SA, Singh Y, Hoard DJ, Demchenko AV. A highly efficient glycosidation of glycosyl chlorides using cooperative silver(I) oxide - triflic acid catalysis. Chem Eur J. 2020;26:8053–8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun L, Wu X, Xiong DC, Ye XS. Stereoselective Koenigs-Knorr glycosylation catalyzed by urea. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:8041–8044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park Y, Harper KC, Kuhl N, Kwan EE, Liu RY, Jacobsen EN. Macrocyclic bis-thioureas catalyze stereospecific glycosylation reactions. Science. 2017;355:162–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steber HB, Singh Y, Demchenko AV. Bismuth(III) triflate as a novel and efficient activator for glycosyl halides. Org Biomol Chem. 2021;19:3220–3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranade SC, Kaeothip S, Demchenko AV. Glycosyl alkoxythioimidates as complementary building blocks for chemical glycosylation. Org Lett. 2010;12: 5628–5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vibhute AM, Dhaka A, Athiyarath V, Sureshan KM. A versatile glycosylation strategy via Au (III) catalyzed activation of thioglycoside donors. Chem Sci. 2016;7: 4259–4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geringer SA, Demchenko AV. Iron(III) chloride-catalyzed activation of glycosyl chlorides. Org Biomol Chem. 2018;16:9133–9137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traboni S, Vessella G, Bedini E, Iadonisi A. Solvent-free, under air selective synthesis of alpha-glycosides adopting glycosyl chlorides as donors. Org Biomol Chem. 2020;18: 5157–5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang F, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Curran DP, Liu G. Synthesis and Applications of a Light-Fluorous Glycosyl Donor. J Org Chem. 2009;74:2594–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farabi K, Manabe Y, Ichikawa H, et al. Concise and Reliable Syntheses of Glycodendrimers via Self-Activating Click Chemistry: A Robust Strategy for Mimicking Multivalent Glycan-Pathogen Interactions. J Org Chem. 2020;85: 16014–16023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogura A, Kurbangalieva A, Tanaka K. Exploring the glycan interaction in vivo: Future prospects of neo-glycoproteins for diagnostics. Glycobiology. 2016;26: 804–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vartak A, Hefny FM, Sucheck SJ. Synthesis of Oligosaccharide Components of the Outer Core Domain of P. aeruginosa Lipopolysaccharide Using a Multifunctional Hydroquinone-Derived Reducing-End Capping Group. Org Lett. 2018;20:353–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hossain MK, Vartak A, Sucheck SJ, Wall KA. Synthesis and Immunological Evaluation of a Single Molecular Construct MUC1 Vaccine Containing l-Rhamnose Repeating Units. Molecules. 2020;25:3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visansirikul S, Kolodziej SA, Demchenko AV. Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides: a structural and synthetic perspective. Org Biomol Chem. 2020;18: 783–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawano T, Sugawara S, Hosono M, et al. Globotriaosylceramide-expressing Burkitt’s lymphoma cells are committed to early apoptotic status by rhamnose-binding lectin from catfish eggs. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johansson D, Kosovac E, Moharer J, et al. Expression of verotoxin-1 receptor Gb3 in breast cancer tissue and verotoxin-1 signal transduction to apoptosis. BMC Cancer. 2009;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okuda T, Nakakita S-I, Nakayama K-I. Structural characterization and dynamics of globotetraosylceramide in vascular endothelial cells under TNF-α stimulation. Glycoconj J. 2010;27:287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagano K, Yoshida Y, Isobe T. Cell surface biomarkers of embryonic stem cells. Proteomics. 2008;8:4025–4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malecki M, Anderson M, Beauchaine M, Seo S, Tambokane X. TRA-1-60+, SSEA-4+, Oct4A+, Nanog+ clones of pluripotent stem cells in the embryonal carcinomas of the ovaries. J. Stem Cell Res Therapy 2012;2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ragupathi G, Koide F, Livingston PO, et al. Preparation and evaluation of unimolecular pentavalent and hexavalent antigenic constructs targeting prostate and breast cancer: a synthetic route to anticancer vaccine candidates. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2715–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.