Abstract

Background

The measurement of appendicular muscle mass is essential for the diagnosis of sarcopenia. Ultrasonography is an accurate and convenient method used to evaluate muscle mass.

Objective

The aim of the study was to evaluate the diagnostic value of ultrasonography for appendicular muscle mass in sarcopenia in older adults and find out proper ultrasound parameters.

Methods

Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases were searched for relevant articles. Published studies on the validity and/or reliability of ultrasonography for quantifying muscle mass of the limbs in sarcopenia in the older population were included. A systematic review was conducted based on specific muscles and reference methods. A meta-analysis was conducted to assess the validity and reliability of the ultrasonography.

Results

Forty articles were included in this review. There were nine, nine, nine, and four studies included in the qualitative synthesis for a diagnostic test, correlation coefficient, intra-class reliability, and inter-class reliability, respectively. The diagnostic value of rectus femoris (RF) or gastrocnemius (GM) thickness on ultrasonography for sarcopenia or low muscle mass was moderate (the area under summary receiver operating characteristic curve [SROC] = 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.72–0.79, SROC = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.76–0.83, respectively). The pooled correlation between muscle mass on dual-energy X-ray (DXA) or bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and muscle thickness (MT) on ultrasound was moderate (r = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.49–0.62). There was a low-to-moderate correlation between muscle mass on DXA or BIA and cross-sectional area (CSA) on ultrasound (r = 0.267–0.584). The correlation was high to very high between muscle mass from DXA and the ultrasound-predicted formula (r = 0.85–0.963). The CSA from ultrasound had a high or very high correlation with that from computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (r = 0.826, intra (inter)-correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.998–0.999). The respective meta-analyses showed good inter-rater and intra-rater reliabilities (ICC > 0.9).

Conclusion

Ultrasonography is a reliable and valid diagnostic method for the quantitative assessment of appendicular muscle mass in sarcopenia in older people. The thickness and CSA of the RF or GM seem to be proper ultrasound parameters to predict muscle mass in sarcopenia. Multicenter studies with large samples and the application of new ultrasonic techniques will be the future research directions.

Keywords: Sarcopenia, Ultrasonography, Muscle mass, Appendicular muscles, Older adults

Introduction

The term sarcopenia was first proposed by Rosenberg in 1988 and was recognized as an independent muscle disease with an International Classification of Diseases-10 Code in 2016 [1, 2]. The definition is controversial and still evolving due to scientific development. The disputed issues include age-related, the variables (e.g., muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance) to be included, and cutoff points. It was defined as “age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass plus loss of muscle strength and/or reduced physical performance” according to the 2019 Consensus by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS2019) [3]. The pathophysiologic mechanisms of sarcopenia remained unclear. It was reported that potential molecular pathophysiology may include protein synthesis and degradation, autophagy, impaired satellite cell activation, mitochondria dysfunction, and other factors associated with muscle weakness and muscle degeneration [4]. Age was the most important risk factor independently associated with sarcopenia, and studies showed that incidence of sarcopenia increased with age [3, 5, 6]. A study on Chinese participants showed that the incidence of sarcopenia was increased during follow-up [7]. Aging seemed to disturb the balance between muscle anabolic and catabolic pathways, resulting in the loss of skeletal muscle. The size and number of myofibers decreased at the cytology level, especially type II fibers. Because type II fibers transformed into type I fibers, intramuscular and intermuscular fat infiltration occurred and the number of type II fiber satellite cells decreased with age [8, 9, 10, 11].

With the life expectancy generally extended, the world population older than 60 years has continuously increased, and the prevalence of sarcopenia is destined to increase [12]. The prevalence of sarcopenia differs according to different definitions, settings, populations, and other factors [5, 13]. A systematic review of 58,404 older adults aged 60 years and older in community found that the overall prevalence of sarcopenia was 10% in the world [14]. The prevalence of sarcopenia ranges from 5.5% to 25.7% in Asian countries, with 5.1–21.0% in males and 4.1–16.3% in females [3]. It is estimated that 50 million individuals worldwide currently suffer from sarcopenia, and the number is expected to quadruple over the next 40 years [15].

Sarcopenia, associated with functional decline, can result in multiple adverse consequences, such as an increased incidence of falls and fractures, impaired daily life capabilities, low quality of life, and death [6, 16, 17]. Furthermore, sarcopenia may be associated with postoperative complications and mortality, resulting in a worse prognosis in patients undergoing major surgery, prolonging the length of hospitalization, etc. [16, 17]. Thus, sarcopenia causes high personal, social, and economic burdens, and its early diagnosis and intervention are recommended [3].

Sarcopenia is diagnosed when low muscle mass coexists with low muscle strength or low physical performance [3, 5, 6]. Currently, methods to evaluate muscle mass include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), dual-energy X-ray (DXA), bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), anthropometry, and ultrasonography (US) [15, 18]. MRI and CT were considered as gold standards for evaluating muscle quantity and quality simultaneously; however, they cannot be applied to large-scale community screening and long-term follow-up work, due to high costs, ionizing radiation, time-consuming procedures, and not being portable [6, 16, 17, 19, 20]. Therefore, MRI and CT have been used in scientific research rather than clinical practice. DXA and BIA, with high accuracy and reliability, were recommended in clinical practice by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People in 2018 (EWGSOP2) and AWGS2019 [3, 15, 20]. However, DXA lacks portability, has device specificity, and may be influenced by the hydration status of patients [6, 16, 17, 19]. BIA is portable but device-specific and population-specific, and its results are greatly affected by the body hydration state, which results in underestimation of muscle mass, and applicability of this device in people with chronic diseases needs to be further verified [5, 6, 19, 21, 22]. Anthropometry is a noninvasive, inexpensive, and convenient method that can be applied in large surveys; however, it requires training, does not generate precise results in the obese population, and is difficult to use for measurements in the elderly [23]. Thus, it was not an ideal method to measure muscle mass and was used when no other methods were available.

US, characterized as real-time, portable, affordable, free of radiation exposure, is an excellent imaging technique for evaluating and long-term monitoring of musculoskeletal disorders; more importantly, it can be performed at the bedside, making it more suitable for older adults [15, 17, 19, 20, 24]. US can assess muscle mass via muscle thickness (MT), cross-sectional area (CSA), and muscle volume [15]. Moreover, the measurement of EI on US can evaluate muscle quality because the echo intensity (EI) of muscles in sarcopenia increase due to fat infiltration. Other US parameters associated with sarcopenia include pennation angle and muscle fascicle length [16]. Indeed, the applicability of ultrasound in evaluating muscle quantity and quality has been proven [16, 25, 26, 27]. Most of the studies supported that ultrasound may be a potential, accurate, and promising method for estimating muscle mass in the future [6, 16, 22, 24, 28].

A few systematic reviews have reported the assessment of muscle mass with ultrasound [26, 29]. One study published in 2018 evaluated the evaluation of US in sarcopenia but was restricted to standardized ultrasound measurements for muscle assessment, not involving the reliability and validity of US to evaluate muscles [29]. Another study published in 2017 reviewed the reliability and validity of US to evaluate muscles in older adults, but meta-analysis was not performed [26]. Nowadays, the clinical use of US to assess muscle mass in sarcopenia remains controversial for the lack of standardized protocols and validated cutoff points [3, 6, 16, 22, 24, 28]. We were concerned with the evaluation of appendicular muscles in sarcopenia because appendicular muscles are easily accessible, time-saving, and suitable for community screening and follow-up, and lower limbs are load-bearing muscles, which are affected earlier and more commonly by sarcopenia. New studies on the diagnosis of sarcopenia using US have emerged in recent years. To evaluate the diagnostic value of US for appendicular muscle mass in sarcopenia in older adults and find out the proper muscle and ultrasound parameters, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (number CRD42021181693).

Search Strategy

We searched Embase, Medline, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases from inception to December 11, 2020. The terms relevant to sarcopenia, US, and older adults were combined in the search strategy. Using the Medline database as an example, “Ultrasonography,” “sarcopenia,” and “aged” were searched using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). Their synonyms were searched in the title/abstract. The restriction was “human”; the operator “OR” was used to combine every term with their synonym, respectively, then the operator “AND” was used to combine the three queries above. Manual retrieval and cross-referencing from original articles and reviews were also performed. An example of the search query in the Embase database is presented (shown in online suppl. Table S1; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000525758 for all online suppl. material). Similar search strategies were performed using the other databases.

Study Search

Published studies concerning the validity and reliability of US to evaluate appendicular muscle mass in the older adults (average age or median age ≥50 years) were qualified for inclusion in this study. Only the sections on the limb muscles were selected in the studies involving the limb and trunk muscles. Additionally, only the sections on the elderly were selected in studies involving older and young adults.

Exclusion criteria: (1) studies of animals or cadavers, studies of non-appendicular muscles (e.g., abdominal muscles, masseter muscles, lingual muscles, digastric muscle, and temporal muscle), studies with a mean age or median age of less than 50 years, and studies on critically ill patients; (2) case reports, reviews or systematic reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, consensus, and conference paper; (3) studies not providing sufficient data to calculate; and (4) abstract/title only publications.

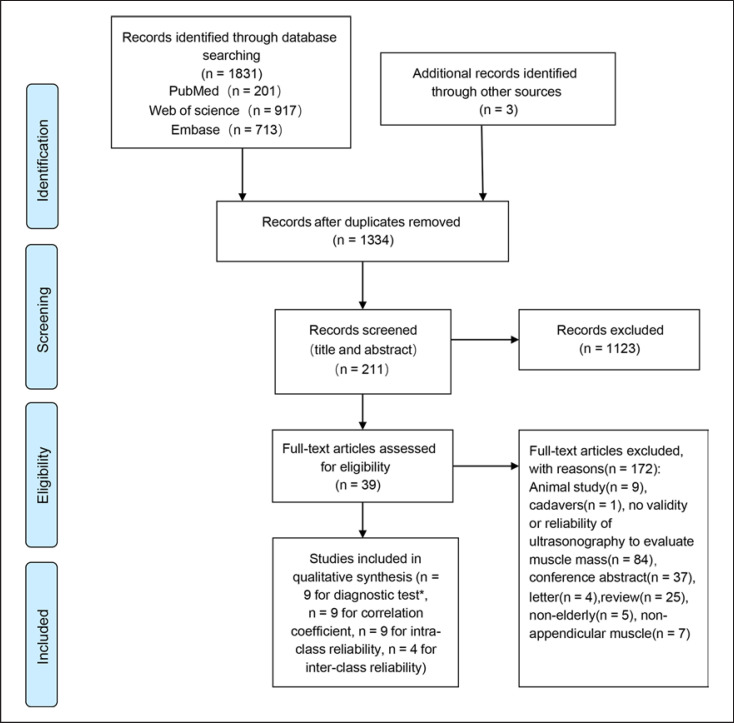

EndNote software was used for document management. After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (R Zhao, X Li) who were blinded to each other's decisions. According to the inclusive and exclusive criteria, the studies were independently classified as relevant or irrelevant. The full text of the relevant study was assessed for eligibility independently by the two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by negotiation. The study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process. * The searches were re-run just before the final analyses and a new study was included for the diagnostic tests.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted data from the included studies using an Excel spreadsheet independently. Any discrepancies were determined by consensus. The extracted data included the authors, year, country, sample size, age, sex, ethnicity, setting, health status, transducer type, scanning plane, muscles, imaging modality, ultrasound parameters (MT, CSA), the definition of sarcopenia, reference methods, validity and/or reliability estimates, and study results including statistical findings and overall conclusions.

Quality Assessment

Selected studies were assessed independently by two reviewers (R Zhao, X Li) using a methodological quality assessment scale by Pretorius and Keating [25]. Ten items were contained to assess the value of US to evaluate muscles (shown in online suppl. Table S2). Each item was scored as “Yes” (1 point), “No” (0 points), or “Not available” (0 points). A high total score suggested good methodological quality.

Statistical Analysis

A systematic review was conducted according to various muscles and reference methods. The validity included diagnostic tests and correlations. The diagnostic test was measured with sensitivity and specificity. The predictive power was measured with the area under the curve (AUC) or adjusted coefficient of determination and standard error of the estimate. Association was measured with odds ratio or correlation coefficient (r), according to the data reported. Reliability was measured with intra (inter)-correlation coefficient (ICC) or kappa values (κ). For AUC, the values of 0–0.5, 0.5–0.7, 0.7–0.9, 0.9–1, and 1 were regarded as none, low, moderate, high, and perfect predictive power, respectively [30]. For correlation coefficient, the values of 0–0.25, 0.26–0.49, 0.50–0.69, 0.70–0.89, and 0.90–1.00 were graded as little, low, moderate, high, and very high correlation, respectively [31]. For ICC, the values of 0–0.50, 0.51–0.75, 0.76–0.90, and 0.91–1.0 were graded as poor, moderate, good, and excellent, respectively [31].

MedCalc Statistical Software version 15.2.2 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org; 2015) was applied to compare the correlation coefficient of muscle mass between bilateral sides or ultrasonographic parameters among different contrast parameters. Data on validity and reliability were pooled with a meta-analysis using random-effects methods, when possible. We performed I2 testing to assess heterogeneity between studies. Statistical heterogeneity exists when I2 values are greater than 50%. Subgroup analysis was then performed according to muscle type when possible. A funnel plot of each study was conducted to assess publication bias. We conducted Begg and Egger tests simultaneously to assess funnel plot asymmetry. Sensitivity analyses with a one-by-one elimination method were used to evaluate the reliability of the meta-analysis. The effect of publication bias was estimated with trim-and-fill computation. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. The Stata Software version 15.1 was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Summary of Findings

A total of 40 articles were included [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71]. The general characteristics of all included studies are presented in Table 1. There were 20 (50%) studies conducted in Asia [32, 33, 38, 40, 41, 42, 44, 46, 48, 51, 52, 59, 60, 62, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 71], 12 (30%) in Europe [35, 36, 37, 43, 45, 47, 49, 50, 54, 56, 61, 69], 4 (10%) in North America, 2 (5%) in South America, and 2 (5%) in Oceania. The settings were community or laboratory in 22 (55%) studies, outpatient or inpatient in 16 (40%) studies, and not available in 2 (5%) studies. The subjects were relatively healthy adults free of overt chronic disease (e.g., neuromuscular, diabetes, severe liver disease, kidney disease, chronic infections, cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke, Parkinson's disease, paresis, amputations, autoimmune disorders affecting the musculoskeletal system, etc.) in 28 (70%) studies, chronic kidney disease patients, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, and heart failure patients in 2 studies, respectively, and coronary artery disease, diabetes, liver cirrhosis, stroke, frailty, and acute kidney injury in one study, respectively. The mean or median ages ranged from 57.5 to 88 years. The reliability and validity of US were evaluated in 12 and 32 studies, respectively. Of the 32 studies on validity, the comparison with US was BIA, DXA, and CT in 13 (40.6%), 12 (37.5%), and 4 (12.5%) studies, respectively, and MRI, CT or MRI, mid-arm muscle circumference in each study; the most commonly evaluated muscle was the rectus femoris (RF) (n = 13), followed by the quadriceps femoris (QF) (n = 10) and gastrocnemius (GM) (n = 9); the MT was the most commonly used ultrasonic parameter (n = 29) followed by CSA (n = 6).

Table 1.

The general characteristics of all the included studies

| Study | Country | Sample size, n (M: F) | Age Mean (SD) | Setting | Healthy status | Comparison | Muscles-US parameters | Reliability/Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silva 2018 [58] | Brazil | 17 (6:11) | M: 61.2 (4.5) F: 58.9 (4.6) | Volunteer | Type 2 diabetes | − | RF-MT, VI-MT, QF-MT, RF-CSA | Reliability |

|

| ||||||||

| Yuguchi 2020 [64] | Japan | 195 (72:123) | 72.4 (4.3) | Community | Healthy | BIA | GM-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Wilkinson 2020 [36] | Britain | 113 (54:59) | 62.0 (14.1) | Outpatient | CKD | BIA | RF-CSA | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Li 2020 [44] | China | 179 (49:130) | M: 70 (66, 80) F: 69 (64, 77)a | Outpatient | Healthy | DXA | BB-MT, BB-CSA | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Wang 2018 [41] | China | 135 (39:96) | 71.25 (7.64) | Community | Healthy | DXA | GM-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Isaka 2019 [38] | Japan | 60 (60:0) | 75.8 (6.2) | Outpatient | Healthy | BIA | TA-MT, GM-MT, SOL-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Hida 2018 [42] | Japan | 201 (99:102) | 66.2 (9.8) | Community | Healthy | BIA | QF-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Sato 2020 [68] | Japan | 185 (114:71) | 74 (12) | Inpatient and outpatient | Heart failure | BIA | RF-MT | Reliability/validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Jung 2020 [51] | Korea | 40 (17:23) | 66.9 (15.4) | Inpatient | Stroke | BIA | RF-MT, VI-MT, TA-MT, GM-MT, BB-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Yamada 2017 [66] | Japan | 347 (100:247) | M: 81.6 (7.4) F: 79.7 (6.9) | Community | Healthy | BIA | RF-MT, VI-MT, QF-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Kawai 2018 [62] | Japan | 1,239 (511:728) | 72.8 (5.3) | Community | Healthy | BIA | QF-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Sengul Aycicek 2019 [46] | Turkey | 136 (46:90) | 74 (64–93)b | Outpatient | Healthy | BIA | GM-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Rustani 2019 [43] | Italy | 119 (59:60) | 82.8 (7) | Inpatient | Healthy | MAMC | RF-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Barotsis 2020 [47] | Greece | 94 (27:67) | 75.6 (6.6) | Outpatient | Healthy | DXA | RF-MT, VI-MT, TA-MT, GM-MT, GM-MT, AA-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Wilson 2019 [69] | Britain | HO:39 (13:26), FO:31 (14:17) | M: 76.0 (69.5–80.5) in HO, 77.5 (73.3− 86.3) in FO. F: 71.0 (70.0–78.0) in HO, 85.5 (78.3–93.0) in FOa | Inpatient and outpatient | Healthy/frail | − | QF-MT | Reliability |

|

| ||||||||

| Kuyumcu 2016 [48] | Turkey | 100 (41:59) | 73.08 (6.18) | Outpatient | Healthy | BIA | GM-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Gulyaev 2020 [61] | Russia | 63 (31:32) | 77.2 (7.7) | NA | CHF | DXA | BB-CSA, BB-MT, PF-CSA, RF-CSA | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Berger 2015 [56] | Spain | 51 (25:26) | M: 74.5 (6.5) F: 72.5 (5.8) | Community | Healthy | DXA | RF-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Zhu 2019 [67] | China | 265 (97:168) | M: 69.33 (6.77) F: 67.79 (6.17) | Community | Healthy | DXA | RA-MT, UA-MT, TP-MT, FP-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Bemben 2002 [39] | America | Postmenopausal: 38 (0:38) Older: 85 (34:51) | Postmenopausal: 58.9 (0.7) Older: 65.0 (0.4) | Volunteer | Healthy | − | RF-CSA, BB-CSA | Reliability |

|

| ||||||||

| Welch 2018 [50] | Britain | 20 (0:20) | Extended care 88 (6.8) | Volunteer | Healthy | − | QF-MT | Reliability |

|

| ||||||||

| Independently: 84 (3.6) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Watanabe 2018 [71] | Japan | 21 (13:8) | 70.6 (4.8) | Community | Healthy | CT | QF-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Vahlgren 2019 [37] | Denmark | 79 (22:57) | 85 (8) | Inpatient | Healthy | − | VL-MT, QF-MT | Reliability |

| Abe 2014 [52] | Japan | 81 (41:40) | 61 (6) | Volunteer | Healthy | DXA | QF-MT, PTM-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Abe 2015a [59] | Japan | 102 (59:43) | 59.3 (6.5) 60.6 (6.9)c | Volunteer | Healthy | DXA | LFA-MT, UAA-MT, UAP-MT, QF-MT, PTM-MT, LLA-MT, LLP-MT, Abd-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Abe 2015b [33] | Japan | 79 (40:39) | 60.9 (6.1) | Volunteer | Healthy | DXA | LFA-MT, UAA-MT, UAP-MT, QF-MT, PTM-MT, LLA-MT, LLP-MT, Abd-MT, subscapular-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Abe 2016 [40] | Japan | 158 (72:86) | 64 (8) | volunteer | Healthy | DXA | Ulna-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Abe 2018a [60] | Japan | 311 (133:178) | 71 (5) 69 (5)c |

volunteer | Healthy | DXA | Ulna-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Abe 2018b [65] | Japan | 389 (167:222) | 71 (5) | volunteer | Healthy | DXA | LFA-MT, UAA-MT, UAP-MT, QF-MT, PTM-MT, LLA-MT, LLP-MT, Abd-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Hammond 2014 [34] | America | 17 (17:0) | 66 (NA) | Volunteer | COPD | − | RF-CSA | Reliability |

|

| ||||||||

| Ramírez-Fuentes 2019 [45] | Spain | 35 (35:0) | 67.7 (7.45) | Laboratory | COPD/Healthy adults | BIA | RF-CSA, RF-MT, RF-Width | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Madden 2020 [57] | Canada | 150 (84:66) | 80.0 (0.5) | Outpatient | Healthy | BIA | VM-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Sabatino 2020 [35] | Italy | 30 (13:17) | 70 (13.6) | Inpatient | AKI | CT | RF-MT, VI-MT | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Raj 2012 [53] | Australia | 21 (11:10) | 68.1 (5.2) | Community | Healthy | − | VL-MT GM-MT | Reliability |

|

| ||||||||

| Reeves 2004 [49] | Britain | 6 (3:3) | 76.8 (3.2) | NA | Healthy | MRI | VL-CSA | Reliability/validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Tandon 2016 [63] | Canada | 159 (89:70) | 57.5 (10.4) | Outpatient | Liver cirrhosis | CT/MRI | QF-MT | Reliability/validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Souza 2018 [55] | Brazil | 100 (41:59) | 73.5 (9.22) | Outpatient | Pre-dialysis CKD | CT | RF-CSA | Validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Thomaes 2012 [54] | Belgium | 45 (44:1) | 68.4 (6.2) | Volunteer | CAD | CT | RF-MT | Reliability/validity |

|

| ||||||||

| Strasser 2013 [70] | Austria | 26 (NA) | 67.8 (4.8) | Outpatient | Healthy | − | RF-MT, VI-MT, VL-MT, VM-MT | Reliability |

|

| ||||||||

| Fukumoto 2021 [32] | Japan | 204 (64:140) | M: 76.9 (6.4) F: 74.7 (5.0) | Community | Healthy | ΒΙΑ | QF-MT, RF-MT, VI-MT, GM-MT, SOL-MT Validity | |

n, number; M, male; F, female; NA, not available; SD, standard deviation; HO, healthy older adults; FO, frail older adults; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; AKI, acute kidney injury; CAD, chronic artery disease; US, ultrasound; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; CT, computed tomography; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; MAMC, mid-arm muscle circumference; RF, rectus femoris; VI, vastus intermedius; QF (RF + VI), quadriceps femoris; GM, gastrocnemius; BB, biceps brachii; TA, tibialis anterior; SOL, soleus; AA, anterior arm; PF, posterior forearm; RA, anterior radial; UA, anterior ulnar; TP, posterior tibial; FP, posterior fibula; PTM, posterior thigh muscle; LFA, lateral forearm; UAA, upper arm anterior; UAP, upper arm posterior; LLA, lower leg anterior; LLP, lower leg posterior; Abd, abdomen; MT, muscle thickness; CSA, cross-sectional area.

The age was shown as median and quartile (M [P25, P75]).

The age was shown as median followed by age range (median [min, max]).

The age of model development and cross-validation, respectively.

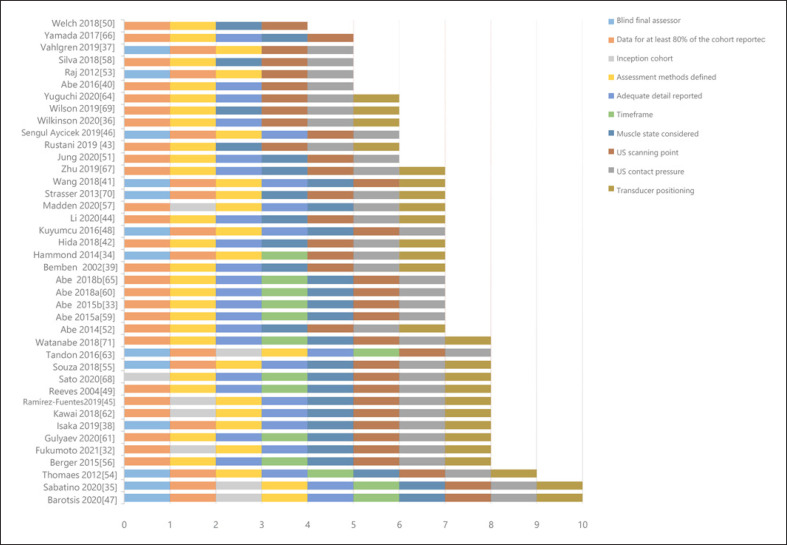

Methodological Quality Assessment

A methodological quality assessment is shown in Figure 2. There were 34 (87.5%) studies that scored 6 points or higher, indicating the good quality of the methodology. Only one (2.5%) study [50] scored 4 points, and five (12.5%) studies [37, 53, 58, 59, 66] scored 5 points. The study that was scored as 4 and three of the five studies that scored as 5 only assessed reliability of the US [37, 50, 53, 58]. Furthermore, some of the items, such as “time frame” and “adequate detail reported,” did not apply to them, so the low scores did not demonstrate a low methodological quality of the studies.

Fig. 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

Meta-Analysis of the Diagnostic Value of US for Sarcopenia

Twelve studies assessed the diagnostic value of US to diagnose low muscle mass or sarcopenia, with DXA, BIA, CT, MRI, or anthropometric measures as the gold standard (shown in Table 2). Five studies assessed the diagnosis of low muscle mass [32, 36, 41, 64, 66], and seven examined the diagnosis of sarcopenia [42, 43, 47, 48, 61, 63, 68]. The diagnostic criteria were AWGS 2014 [72] in four studies [41, 42, 66, 68], AWGS 2019 [3] in two studies [32, 64], EWGSOP 2010 [15] in one studies [43], EWGSOP 2019 [6] in two study [36, 47], and FNIH [73] in two studies [36, 61]. The reference method was BIA in seven studies [32, 36, 42, 48, 64, 66, 68], DXA in three studies [41, 43, 61], CT or MRI in one study [63], and anthropometric measures in one study [47].

Table 2.

The diagnostic value of ultrasonography to predict low muscle mass or sarcopenia by muscle mass measurement in older individuals

| Study | Sample size, n (M:F) | Muscles-US parameters | Reference method | Diagnosis | Diagnostic criteria | Cutoff value | Resultsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuguchi 2020 [64] | 195 (72:123) | GM-MT | BIA | Low muscle mass | AWGS2019 [3] | 1.16cm | AUC 0.83 (NA), SE 0.83, Sp 0.73 |

|

| |||||||

| Yamada 2017 [66] | 347 (100:247) | RF-MT, VI-MT, QF-MT | BIA | Low muscle mass | AWGS2014 [72] | M: 1.34 cm (RF) | M: AUC 0.70 (0.58–0.81), SE 0.68, Sp 0.65 |

| M: 1.44 cm (VI) | M: AUC 0.66 (0.53–0.78), SE 0.64, Sp 0.65 | ||||||

| M: 2.88 cm (QF) | M: AUC 0.68 (0.56–0.80), SE 0.64, Sp 0.65 | ||||||

| F: 1.18 cm (RF) F: 1.17 cm | F: AUC 0.63 (0.56–0.71), SE 0.60, Sp 0.60 | ||||||

| (VI) | F: AUC 0.61 (0.52–0.69), SE 0.61, Sp 0.56 | ||||||

| F: 2.33 cm (QF) | F: AUC 0.62 (0.54–0.70), SE 0.60, Sp 0.53 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Wang 2018 [41] | 135 (39:96) | GM-MT | DXA | Low muscle mass | AWGS2014 [72] | 1.5 cm | AUC 0.82 (NA), SE 0.70, Sp 0.76 |

|

| |||||||

| Sato 2019 [68] | 69 (NA:NA) | RF-MT | BIA (SMI) | Sarcopenia | AWGS2014 [72] | 1.5 cm | AUC 0.798 (NA), SE 0.767, Sp 0.808 |

|

| |||||||

| Hida 2018 [42] | 201 (99:102) | QF-MT | BIA (ASMI) | Sarcopenia | AWGS2014 [72] | M: 3.6 cm | M: AUC 0.71 (NA), SE 0.72, Sp 0.739 |

| F: 3.4 cm | F: AUC 0.74 (NA), SE 0.722, Sp 0.724 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Wilkinson 2020 [36] | 113 (54:59) | RF-CSA | BIA | Low muscle mass | EWGSOP 2019 (ASM/H2) [9] | M: 8.9 cm2 | M: AUC 0.7 (NA), SE 1, Sp 0.467 |

| FNIH (ASM) | M: 6.7 cm2 | M: AUC 0.7 (NA), SE 0.5, Sp 0.85 | |||||

| FNIH (ASM/BMI) [73] | M: 9.4 cm2 | M: AUC 0.7 (NA), SE 0.929, Sp 0.447 | |||||

| F: 6.5 cm2 | F: AUC 0.8 (NA), SE 1, Sp 0.605 | ||||||

| F: 5.7 cm2 | F: AUC 0.9 (NA), SE 1, Sp 0.70 | ||||||

| F: 6.5 cm2 | F: AUC 0.7 (NA), SE 0.875, Sp 568 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Gulyaev 2010 [61] | 63 (31:32) | The formula of BB-CSA, PF-CSA and RF-CSA | DXA | Sarcopenia | FNIH 2014 [73] | − | Formula 1: adjusted R2 0.921, SE 0.903, Sp 0.968 |

| Formula 2: adjusted R2 0.921, SE 0.87, Sp 0.968 | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Kuyumcu 2016 [48] | 100 (41:59) | GM-MT | BIA | Sarcopenia | Low FFMI and poor handgrip strength [48] | 1.69 (R-MT) | AUC 0.833 (NA), SE 1, Sp 0.6456 |

| 1.71 (L-MT) | AUC 0.784 (NA), SE 0.9231, Sp 0.5256 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Tandon 2016 [63] | 159 (89:70) | The formula of QF-MT | CT/MRI | Sarcopenia | The L3 muscle area: ≤52.4 cm2/m2 in males and ≤38.5 cm2/m2 in females [63] | − | M: AUC 0.78 (NA), SE 0.72, Sp 0.78 |

| F: AUC 0.89 (NA), SE 0.94, Sp 0.76 | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Barotsis 2020 [47] | 94 (27:67) | VI-MT, RF-MT, QF-MT, MGM-MT | DXA | Sarcopenia | EWGSOP 2019 [9] | D-Trans | D-Trans |

| 1.01 cm (VI) | VI: AUC 0.67 (0.53–0.81), SE 0.50, Sp 0.846 | ||||||

| 1.00 cm (DF) | QF: AUC 0.68 (0.54–0.81), SE 0.70, Sp 0.76 | ||||||

| 1.54 cm (MHG) | MHG: AUC 0.69 (0.55–0.84), SE 0.75, Sp 0.564 | ||||||

| D-Long | D-Long | ||||||

| 1.59 cm (VI) | VI: AUC 0.67 (0.52–0.81), SE 0.50, Sp 0.821 | ||||||

| 1.13 cm (QF) | QF: AUC 0.67 (0.53–0.81), SE 0.75, Sp 0.60 | ||||||

| 2.62 cm (MHG) | MHG: AUC 0.70 (0.56–0.84), SE 0.75, Sp 0.615 | ||||||

| Nd-Trans | Nd-Trans | ||||||

| 2.84 cm (RF) | RF: AUC 0.67 (0.53–0.82), SE 0.69, Sp 0.65 | ||||||

| 2.80 cm (QF) | QF: AUC 0.66 (0.51–0.81), SE 0.63, Sp 0.58 | ||||||

| 2.61 cm (MHG) | MHG: AUC 0.74 (0.61–0.86), SE 0.75, Sp 0.679 | ||||||

| Nd-Long | Nd-Long | ||||||

| 1.65 cm (RF) | RF: AUC 0.68 (0.56–0.80), SE 0.81, Sp 0.51 | ||||||

| 1.61 cm (VI) | VI: AUC 0.66 (0.51–0.79), SE 0.63, Sp 0.64 | ||||||

| 1.63 cm (QF) | QF: AUC 0.69 (0.57–0.81), SE 0.63, Sp 0.66 | ||||||

| 1.72 cm (MG) | MG: AUC 0.73 (0.62–0.85), SE 0.875, Sp 0.526 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Rustani 2019 [43] | 119 (59:60) | RF-MT | MAMC | Sarcopenia | EWGSOP 2010 [14] | M: 0.9 cm F: 0.7 cm and M: 0.6 cm F: 0.5 cm |

AUC 0.90 (NA), SE 1, Sp0.64 AUC 0.90 (NA), SE 0.63, Sp 0.93 |

|

| |||||||

| Fukumoto 2021 [32] | 204 (64:140) | QF-MT, RF-MT, VI-MT, GM-MT, SOL-MT | BIA | Low muscle mass | AWGS2019 [3] | M: 2.88 cm (QF), 1.51 cm (RF), 1.15 cm (VI), 1.53 cm (GM), 4.16 cm (SOL) F: 2.34 cm (QF), 1.43 cm (RF), 0.91 cm (VI), 1.42 cm (GM), 3.75 cm (SOL) | M: QF: AUC 0.777 (NA), SE 0.923, Sp 0.571, RF: AUC 0.775 (NA), SE 0.692, Sp 0.837 VI: AUC 0.673 (NA), SE 0.692, Sp 0.673 GM: AUC 0.799 (NA), SE 0.846, Sp 0.633, SOL: AUC 0.779 (NA), SE 0.769, Sp 0.653 F: QF: AUC 0.745 (NA), SE 0.667, Sp 0.752, RF: AUC 0.654 (NA), SE 0.600, Sp 0.670 VI: AUC 0.710 (NA), SE 0.667, Sp 0.642 GM: AUC 0.748 (NA), SE 0.700, Sp 0.764, SOL: AUC 0.645 (NA), SE 0.600, Sp 0.664 |

n, number; M, male; F, female; NA, not available; R, right; L, left; H, height; US, ultrasound; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MAMC, mid-arm muscle circumference; RF, rectus femoris; VI, vastus intermedius; QF (RF + VI), quadriceps femoris; GM, gastrocnemius; BB, biceps brachii; MGM, medial head of the gastrocnemius; SOL, soleus; PF, posterior forearm; MT, muscle thickness; CSA, cross-sectional area; SMI, skeletal muscle index; ASM, appendicular skeletal muscle mass; ASMI, Appendicular skeletal muscle mass index; BMI, body mass index; FFMI, fat-free muscle mass index; L3, the L3 vertebral level; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve; SE, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; D, dominant side; Nd, nondominant side; long, longitudinal ultrasound scan; trans, transverse ultrasound scan; AWGS, Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia; FNIH, The Foundation for the National Institutes of Health; EWGSOP, The European Working Group on Sarcopenia.

In the parentheses behind the value of AUC is 95% confidential interval of AUC.

MT was measured in 10 studies [32, 41, 42, 43, 47, 48, 63, 64, 66, 68]. One evaluated the accuracy of the ultrasound-derived prediction equation with QF thickness and showed a moderate diagnostic performance for sarcopenia in men (AUC = 0.78) and women (AUC = 0.89). Nine studies provided data on the accuracy of MT obtained by the US compared to BIA, DXA, or anthropometric measures as the gold standard. We performed a meta-analysis according to muscle type. There were RF in four studies, GM in five, QF in four, and vastus intermedius (VI) in three.

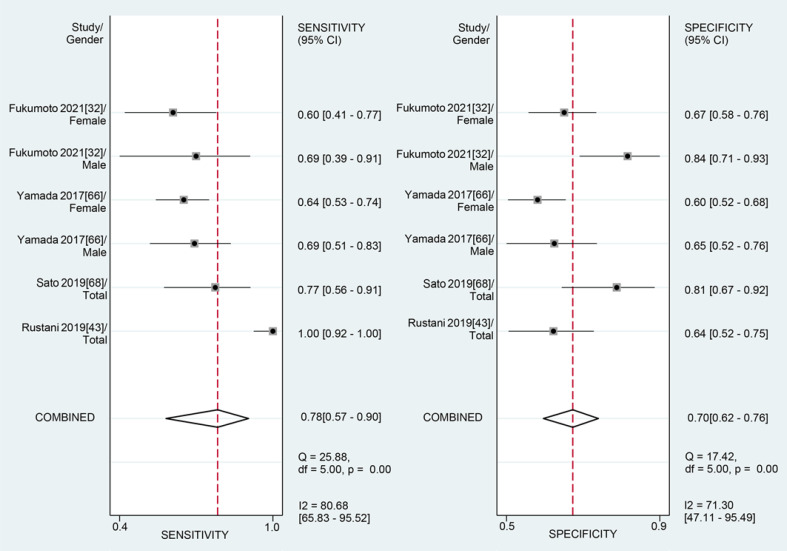

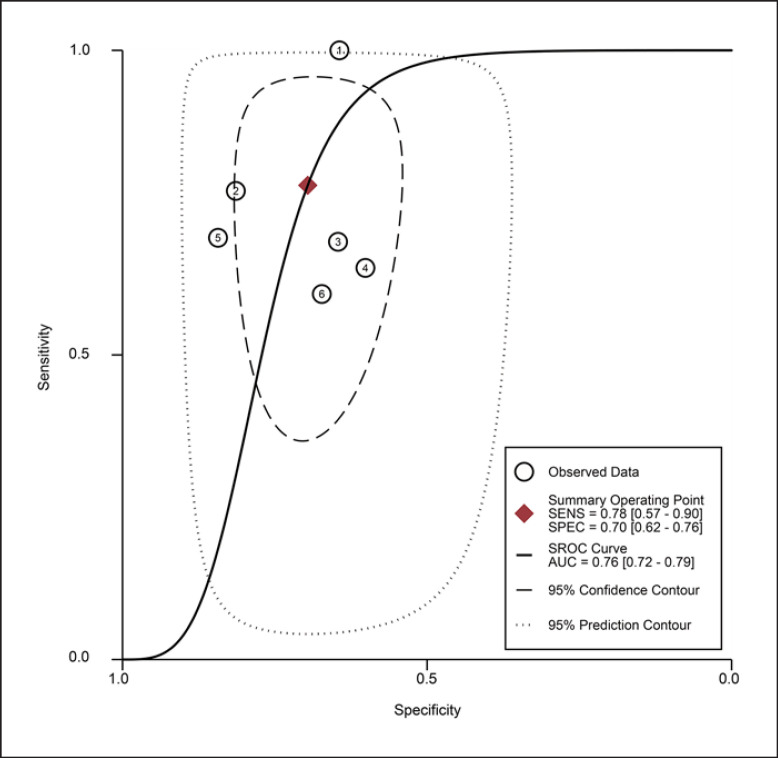

For the MT of RF obtained by the US, the diagnostic value was moderate (the area under summary receiver operating characteristic curve [SROC]: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.72–0.79), with the pooled sensitivity of 0.78 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.57–0.90) and specificity 0.70 (95% CI: 0.62–0.76). The heterogeneity for SROC was substantial (I2: 81.95%, 95% CI: 59–100) (shown in Fig. 3, 4). Deeks' funnel plot asymmetry test indicated no significant publication bias (p = 0.58) (shown in online suppl. Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of rectus femoris thickness on ultrasound for the diagnosis of sarcopenia.

Fig. 4.

Summary receiver-operating characteristic curve: rectus femoris thickness by ultrasound ①: Fukumoto 2021 [32]/female, ②: Fukumoto 2021 [32]/male, ③: Yamada 2017 [66]/female, ④: Yamada 2017 [66]/male, ⑤: Sato 2019 [68]/total, and ⑥: Rustani 2019 [43]/total.

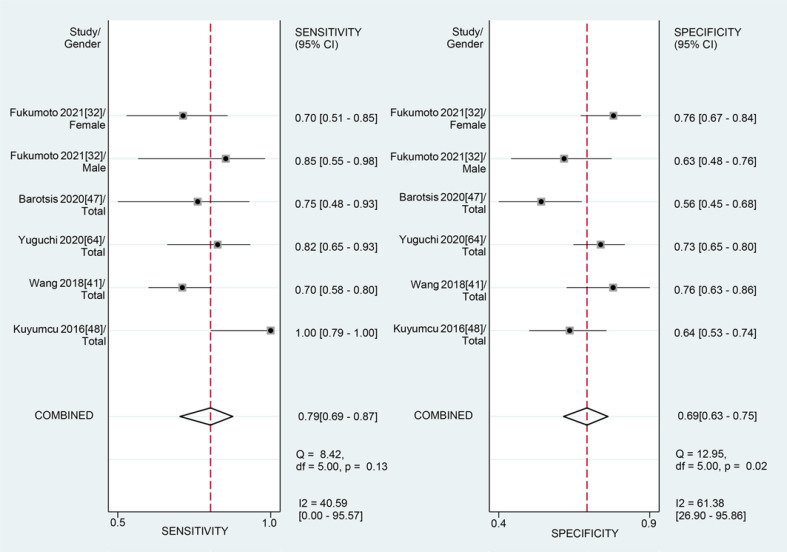

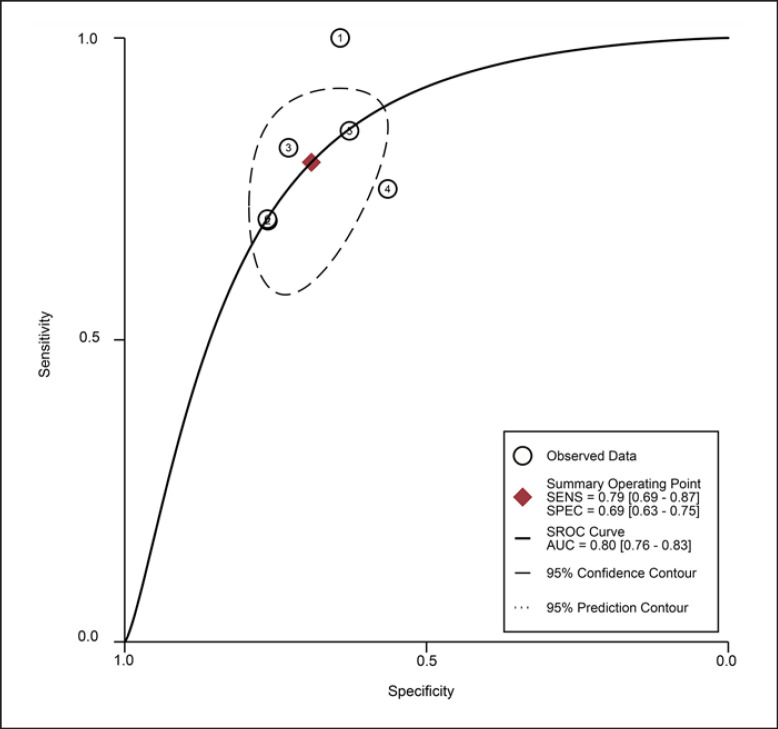

For the MT of GM obtained by the US, the diagnostic value was moderate (SROC: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.76–0.83), with the pooled sensitivity of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.69–0.87) and specificity 0.69 (95% CI: 0.63–0.75). The heterogeneity for SROC was moderate (I2: 51.95%, 95% CI: 0–100) (shown in Fig. 5, 6). Deeks' funnel plot asymmetry test indicated no significant publication bias (p = 0.70) (shown in online suppl. Fig. S2).

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity and specificity of gastrocnemius thickness on ultrasound for the diagnosis of sarcopenia.

Fig. 6.

Summary receiver-operating characteristic curve: gastrocnemius thickness by ultrasound ①: Fukumoto 2021 [32]/female; ②: Fukumoto 2021 [32]/male; ③: Barotsis 2020 [47]/total; ④: Yuguchi 2020 [64]/total; ⑤: Wang 2018 [41]/total; ⑥: Kuyumcu 2016 [48]/total.

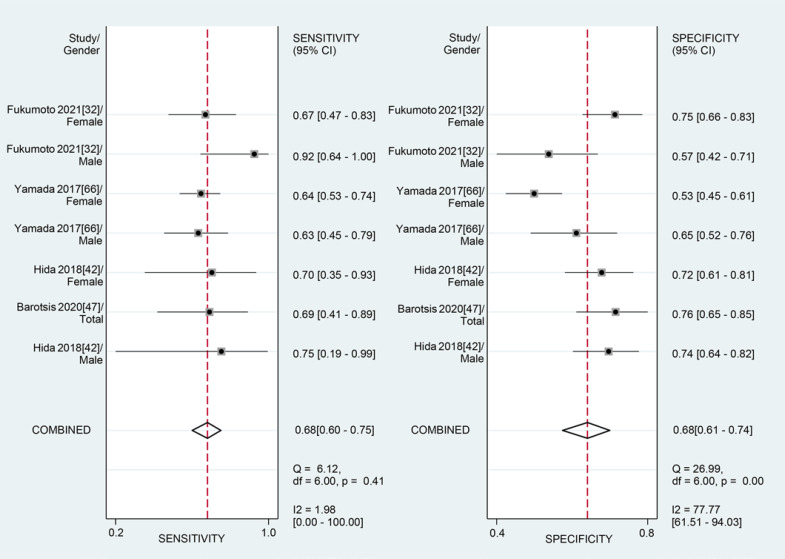

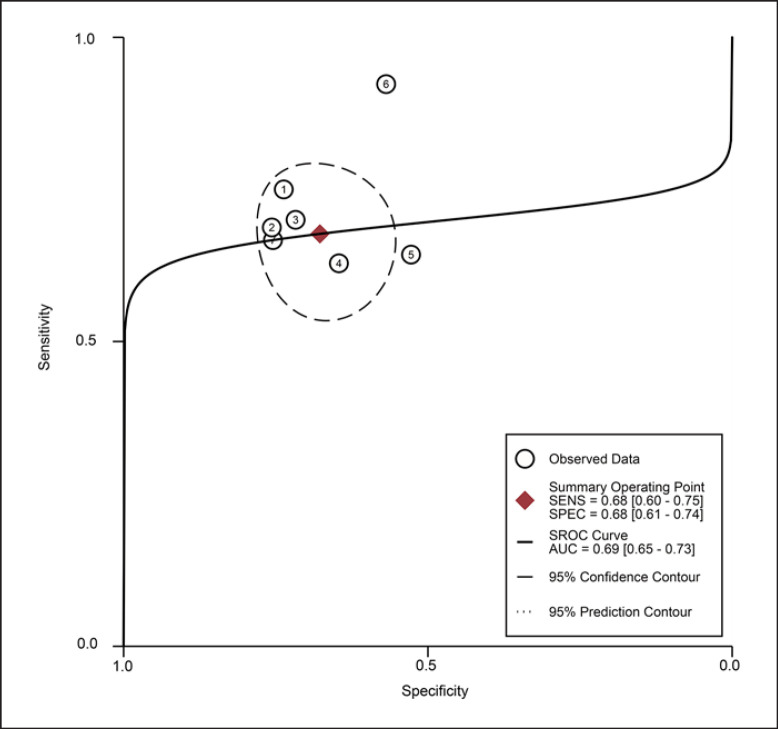

For the MT of QF obtained by the US, the diagnostic value was low (SROC: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.65–0.73), with the pooled sensitivity of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.60–0.75) and specificity 0.68 (95% CI: 0.61–0.74). The heterogeneity for SROC was mild (I2: 29.95%, 95% CI: 0–100) (shown in Fig. 7, 8). Deeks' funnel plot asymmetry test indicated a significant publication bias (p = 0.03) (shown in online suppl. Fig. S3).

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity and specificity of quadriceps femoris thickness on ultrasound for the diagnosis of sarcopenia.

Fig. 8.

Summary receiver-operating characteristic curve: quadriceps femoris thickness by ultrasound ①: Fukumoto 2021 [32]/female; ②: Fukumoto 2021 [32]/male; ③: Yamada 2017 [66]/female; ④: Yamada 2017 [66]/male; ⑤: Hida 2018 [42]/female; ⑥: Barotsis 2020 [47]/total; ⑦: Hida 2018 [42]/male.

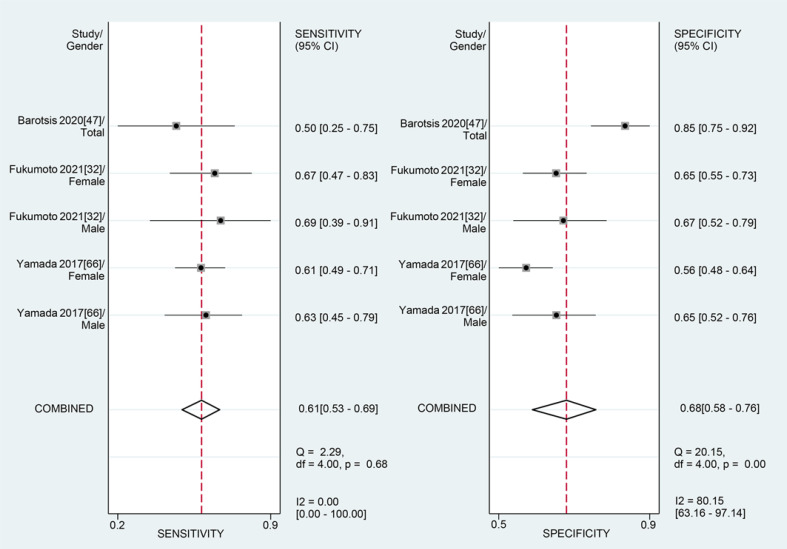

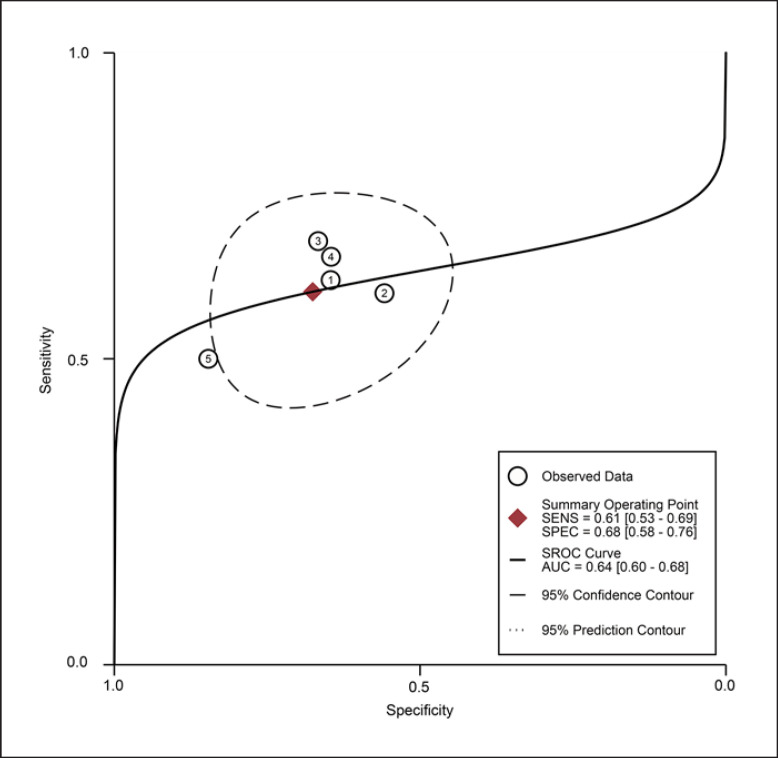

For the MT of VI obtained by the US, the diagnostic value was low (SROC: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.60–0.68), with the pooled sensitivity of 0.61 (95% CI: 0.53–0.69) and specificity 0.68 (95% CI: 0.58–0.76). The heterogeneity for SROC was moderate (I2: 61.95%, 95% CI: 11–100) (shown in Fig. 9, 10). Deeks' funnel plot asymmetry test indicated a significant publication bias (p = 0.01) (shown in online suppl. Fig. S4).

Fig. 9.

Sensitivity and specificity of vastus intermedius thickness on ultrasound for the diagnosis of sarcopenia.

Fig. 10.

Summary receiver-operating characteristic curve: vastus intermedius thickness by ultrasound ①: Barotsis 2020 [47]/total; ②: Fukumoto 2021 [32]/female; ③: Fukumoto 2021 [32]/male; ④: Yamada 2017 [66]/female; ⑤: Yamada 2017 [66]/male.

CSA was measured in two studies [36, 61]. One study evaluated the accuracy of an ultrasound-derived prediction equation and showed that the appendicular lean mass (ALM) derived from muscle ultrasound measurements had a very high correlation with that measured by DXA (adjusted R2 = 0.92). The other study evaluated the diagnostic value of RF-CSA for low muscle mass with BIA and showed moderate discriminative ability (AUC: 0.7 in males, and 0.7–0.9 in females).

The Association of Muscle Mass with Ultrasonographic Parameters

The Comparison of Correlation Coefficient of Muscle Mass with Ultrasonographic Parameters between Bilateral Sides

The results of Kuyumcu et al. [48] showed no significant difference in the correlation coefficient for fat-free mass index (FFMI) and GM thickness, fascicle length, and pinnation angle on US between the left and right sides (p = 0.19, p = 0.45, p = 0.23). Jung et al. [51] discovered no significant difference in the correlation coefficient of the appendicular skeletal muscle index and the thicknesses of the VI, RF, GM, tibialis anterior (TA), and biceps brachii (BB) between the paretic and unaffected sides in stroke patients (p = 0.38, p = 0.69, p = 0.27, p = 0.71, p = 0.61) [51]. Therefore, we chose the correlation coefficient of the right side, the dominant side, or the average of the bilateral sides in articles involving bilateral sides for quantitative analysis.

However, Barotsis et al. [47] found significant differences in the thickness values between the dominant side and nondominant side concerning TA (longitudinal and transverse sections), VI (longitudinal section), GM (longitudinal and transverse sections), and the anterior arm muscles (transverse section), and no significant differences concerning VI (transverse section), anterior arm muscles (long section), and RF (transverse and longitudinal sections).

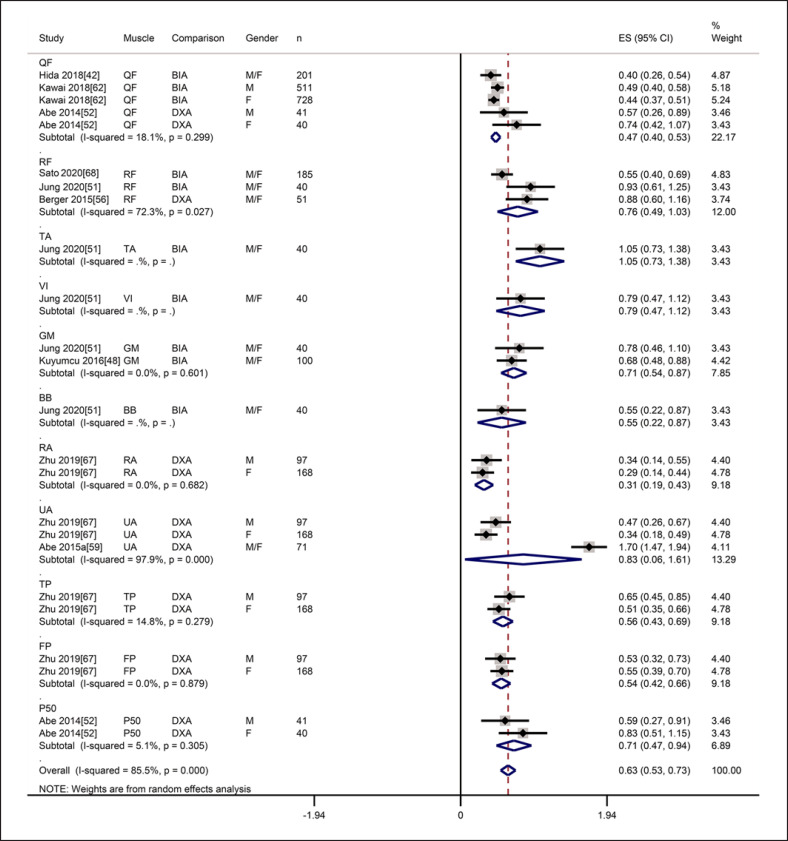

Meta-Analysis of the Correlation Coefficient of Muscle Mass and Ultrasonographic Thickness

There was a significantly positive correlation between MT and muscle mass (r = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.49–0.62), with statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 85.5%, p = 0.000) (shown in Fig. 11). Subgroup analysis by muscle showed that there was a significantly positive correlation between MT of QF and muscle mass (r = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.38–0.48), with no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 18.1%, p = 0.299) (shown in Fig. 11). The Egger test showed a publication bias (p = 0.008) (shown in online suppl. Fig. S5). The trim-and-fill test showed that the estimates were not influenced by publication bias (shown in online suppl. Fig. S6). Sensitivity analyses with a one-by-one elimination method showed that the primary meta-analysis was reliable (shown in online suppl. Fig. S7).

Fig. 11.

Forest plot of the correlation between muscle thickness on ultrasound and muscle mass on reference techniques.

The Correlation Coefficient of Muscle Mass with CSA of Muscles

The studies found a low-to-moderate correlation between muscle mass from DXA or BIA and CSA of RF or BB on ultrasound (r = 0.267–0.584, R2 = 0.426–0.438, ICC = 0.546–0.685) [36, 44, 45, 55]. The CSA of the RF or vastus lateralis (VL) from ultrasound had a high or very high correlation with that from CT or MRI (r = 0.826, ICC = 0.998–0.999) [49, 55].

Odds Ratio of Muscle Mass and Ultrasonographic Parameters

Five studies measured the association between ultrasound parameters and low muscle mass or sarcopenia via odds ratio [38, 41, 44, 47, 64]. Wang et al. [41] and Yuguchi et al. [64] found that GM thickness on US was associated with low skeletal muscle mass. Isaka et al. [38] found that the MT of TA was associated with sarcopenia. Barotsis et al. [47] found that the MT of VI, RF, QF, and GM was associated with sarcopenia. Li et al. [44] showed that the CSA of BB was a significant risk factor of sarcopenia (shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

The association of muscle ultrasound parameters with reference techniques of muscle mass measurement in older individuals

| Study | n (M:F) | Reference method (parameter) | Muscle-ultrasound parameter | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hida 2018 [42] | 201 (99:102) | BIA (SMI) | QF-MT | M: r = 0.25 |

|

| ||||

| F: r = 0.44 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Total: r = 0.38 (controlling for gender: r = 0.0.35) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Sato 2020 [68] | 185 | BIA (SMI) | RF-MT | r = 0.5 |

|

| ||||

| Jung 2020 [51] | 40 | BIA (SMI) | TA-MT | TA-MT: r = 0.783 |

| VI-MT | VI-MT: r = 0.661 | |||

| RF-MT | RF-MT: r = 0.73 | |||

| GM-MT | GM-MT: r = 0.652 | |||

| BB-MT | BB-MT: r = 0.497 | |||

|

| ||||

| Kawai 2018 [62] | 1239 (511:728) | BIA (SMI) | QF-MT | M: r = 0.454 (r = 0.445 controlling for age) |

|

| ||||

| F: r = 0.414 (r = 0.395 controlling for age) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Kuyumcu 2016 [48] | 100 | BIA (FFMI) | Right: GM-MT | Right GM-MT: r = 0.59 |

|

| ||||

| Left: GM-MT | Left GM-MT: r = 0.454 | |||

|

| ||||

| Berger 2015 [56] | 51 | DXA (FFM) | Right: RF-MT | DXA-FFM |

| DXA (lower limb fat-free mass) | Left: RF-MT | Right: r = 0.6766, left: r = 0.6911, average: r = 0.7066 | ||

| DXA (appendicularfat-free mass) | Average: RF-MT | DXA-Lower limb fat-free mass | ||

|

| ||||

| Right: r = 0.71, left: r = 0.7318, average: r = 0.7448 | ||||

| DXA-Appendicular fat-free mass | ||||

| Right: r = 0.7067, left: r = 0.728, average: r = 0.7411 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Zhu 2019 [67] | 265 (97:168) | DXA (upper limb LM, lower limb LM, ALM, RASM) | anterior radial-MT, anterior ulnar-MT, posterior tibial-MT, posterior fibula-MT | M: r = 0.211–0.570 |

|

| ||||

| F: r = 0.267–0.534 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Abe 2014 [52] | 81 (41:40) | DXA (ALM) | Anterior 50% thigh-MT, posterior 50% thigh-MT | DXA-ALM, anterior 50% thigh-MT: M: r = 0.591, F: r = 0.55 |

|

| ||||

| DXA (ALMI) | DXA-ALM, posterior 50% thigh-MT: M: r = 0.543, F: r = 0.693 | |||

|

| ||||

| DXA-ALMI, anterior 50% thigh-MT: M: r = 0.518, F: r = 0.631 | ||||

|

| ||||

| DXA-ALMI, posterior 50% thigh-MT: M: r = 0.53, F: r = 0.679 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Abe 2015a [59] | 102 (71:31)a | DXA (ALM) | forearm-ulna-MT | Forearm-ulna-MT: r = 0.936 (n = 71) |

|

| ||||

| 10-sites MT | 10-sites MT: r = 0.379–0.936 (n = 71) | |||

|

|

||||

| seven equations from ultrasound MT with age and sex | R2: 0.877–0.955 (n = 71) | |||

|

|

||||

| eight equations from MT × standing height with age and sex | R2: 0.908–0.972 (n = 71) | |||

|

|

||||

| fifteen formulas of MT | ICC = 0.808 (0.787–0.945) − 0.963 (0.924–0.982) | |||

|

| ||||

| Watanabe 2018 [71] | 21 | CT (CSA of the mid-thigh) | QF-MT | r = 0.574 |

|

| ||||

| Thomaes 2012 [54] | 20 | CT (RF-MT) | RF-MT | ICC = 0.92 (0.81–0.97) |

|

| ||||

| Abe 2015b [33] | 79 | DXA (ALM) | estimated FFM, leg LM or TMM of 9-sites MT | r = 0.85–0.94 |

|

| ||||

| Abe 2018a [60] | 311 (215:96)b | DXA (ALM) | The ultrasound-predicted ALM of MT-ulna | ALM: r = 0.91 (n = 215) |

|

| ||||

| DXA (ALM-minus-aFFAT) | The ultrasound-predicted ALM-minus-FFAT appendicular of MT-ulna | ALM-minus-FFAT appendicular: r = 0.935 (n = 96) | ||

|

| ||||

| Abe 2016 [40] | 158 | DXA (ALM) | Ulna MTformula-1 | r = 0.882 |

|

| ||||

| Ulna MTformula-2 | r = 0.944 | |||

|

| ||||

| Abe 2018b [65] | 389 | DXA (ALM minus aFFAT) | 4-site MT model | 4-site MT model: R2 = 0.902 (adjusted R2 = 0.899) |

|

| ||||

| 1-site MT model | 1-site MT model: R2 = 0.868 (adjusted R2 = 0.866) | |||

|

| ||||

| Barotsis 2020 [47] | 94 | DXA (SMI) | VI-Trans(D)-MT | VI-Trans(D)-MT: OR = 9.47 (2.24–40.08) |

|

| ||||

| VI-Long(D)-MT | VI-Long(D)-MT: OR = 6.33 (1.67–23.99) | |||

| RF-Trans(ND)-MT | RF-Trans(ND)-MT: OR = 11.9 (2.29–61.85) | |||

| RF-Long(ND)-MT | RF-Long(ND)-MT: OR = 6.9 (1.40–33.89) | |||

| VI-Long(ND)-MT | VI-Long(ND)-MT: OR = 6.92 (1.59–30.11) | |||

| QF-Trans(D)-MT | QF-Trans(D)-MT: OR = 9.41 (2.22–39.88) | |||

| QF-Long(D)-MT | QF-Long(D)-MT: OR = 8.44 (1.89–37.68) | |||

| QF-Trans(ND)-MT | QF-Trans(ND)-MT: OR = 4.94 (1.19–20.38) | |||

| QF-Long(ND)-MT | QF-Long(ND)-MT: OR = 4.59 (1.25–16.81) | |||

| GM-Trans(D)-MT | GM-Trans(D)-MT: OR = 4.52 (1.09–18.79) | |||

| GM-Long(D)-MT | GM-Long(D)-MT: OR = 3.92 (1.01–15.34) | |||

| GM-Trans(ND)-MT | GM-Trans(ND)-MT: OR = 11.34 (2.38–53.94) | |||

| GM-Long(ND)-MT | GM-Long(ND)-MT: OR = 8.49 (1.63–44.2) | |||

|

| ||||

| Wilkinson 2020 [36] | 76 | BIA (ASM), | RF-CSA | ΒΙΑ-ASM: R2 = 0.426, ICC = 0.546 (0.363–0.688) |

| BIA (TMM) | BIA-TMM: R2 = 0.438, ICC = 0.685 (0.541–0.789) | |||

| Li 2020 [44] | 179 (49:130) | DXA (SMI) | BB-CSA | M: r = 0.46 |

| F: r = 0.267 | ||||

| OR = 0.465 (0.225–0.963) | ||||

| Souza 2018 [55] | 100 | DXA (LBM in the upper limbs) | RF-CSA | LBM the upper limbs: r = 0.286 |

| DXA (LBM in the lower limbs) | LBM the lower limbs: r = 0.271 | |||

| CT (RF-CSA) | CT (RF-CSA): r = 0.826 | |||

| Ramírez-Fuentes 2019 [45] | 35 | COPD | RF-CSA | COPD |

| BIA (FFM) | BIA-FFM: r = 0.584 | |||

| BIA (FFMI) | BIA-FFMI: r = 0.549 | |||

| BIA (DLM) | BIA-DLM: r = 0.572 | |||

| Control | Control | |||

|

| ||||

| BIA (DLM) | BIA-DLM: r = 0.549 | |||

|

| ||||

| BIA (FFM) | BIA-FFM: r = 0.534 | |||

|

| ||||

| Reeves 2004 [49] | 6 | MRI (VL-CSA) | VL-CSA | ICC = 0.998–0.999 |

|

| ||||

| Gulyaev 2020 [61] | 63 | DXA (ALM) | Formula-1 from CSA of BB, FA and RF | Formula-1: r = 0.961 |

| Formula-2 from CSA of BB and RF | Formula-2: r = 0.963 | |||

|

| ||||

| Madden 2020 [57] | 150 | BIA (LBM) | VM-MT | R2 = 0.577 |

|

| ||||

| Yuguchi 2020 [64] | 195 | ΒΙΑ (SMI) | GM-MT | OR = 0.584 (0.416–0.818) |

|

| ||||

| Wang 2018 [41] | 135 | DXA (SMI) | GM-MT | OR = 0.001 (0–0.01) |

|

| ||||

| Isaka 2019 [38] | 60 | BIA (SMI) | TA-MT | OR = 5.08 (1.87–20.81) |

n, number; M, male; F, female; NA, not available; R, right; L, left; US, ultrasound; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RF, rectus femoris; VI, vastus intermedius; QF (RF + VI), quadriceps femoris; TA, tibialis anterior; GM, gastrocnemius; BB, biceps brachii; VM, vastus medialis; VL, vastus lateral; FA, forearm; MT, muscle thickness; CSA, cross-sectional area; D, dominant side; Nd, nondominant side; long, longitudinal ultrasound scan; trans, transverse ultrasound scan; R, Pearson's correlation coefficient; R2, coefficient of determination; ICC, inter-class correlation coefficient; OR, odds ratios; SMI, skeletal muscle index; FFM, fat-free mass; FFMI, fat-free mass index; LM, lean mass; ALM, appendicular lean mass; ALMI, appendicular lean mass index; RASM, relative appendicular skeletal muscle mass; FFAT, fat-free adipose tissue; aFFAT, appendicular fat-free adipose tissue; ASM, appendicular skeletal muscle mass; TMM, total muscle mass; LBM, lean body mass; DLM, dominant lean muscle; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

71 in the model-development group and 31 in the cross-validation group.

215 in the model-development group and 96 in the cross-validation group.

The Correlation Coefficient of Muscle Mass from DXA with Ultrasound-Predicted Muscle Mass

Gulyaev et al. [61] showed a very high correlation between ALM from DXA and prediction equations derived from the CSA of BB, FA, and RF on US (r = 0.961–0.963). Abe et al. [65] found a high or very high correlation between ALM from DXA and prediction equations derived from MT of different muscles on US (r = 0.85–0.944, R2: 0.877–0.972, ICC = 0.808–0.963), between ALM-minus-appendicular-fat-free adipose tissue from DXA and prediction equations derived from MT of different muscles on US (r = 0.935, R2: 0.868–0.902) [33, 40, 59, 60, 65] (shown in Table 3).

The Reliability of US to Assess Muscle Mass in Older Adults

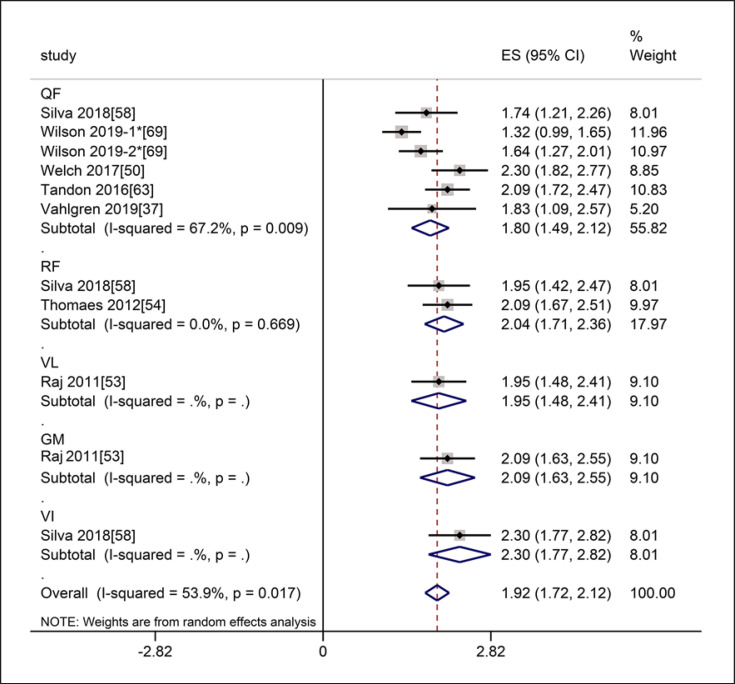

The Intra-Class Reliability of US to Assess Muscle Mass

In terms of intra-class reliability, seven studies referred to the thickness of muscles involving the RF, VI, QF, VL, and GM. The meta-analysis of MT showed that the intra-class reliability was excellent (ICC = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.94–0.97), with statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 53.9%, p = 0.017). Subgroup analysis by muscle showed that the intra-class reliability of the thickness of the QF was excellent (ICC = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.90–0.97), with statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 67.2%, p = 0.009), and the intra-class reliability of the thickness of the RF was excellent (ICC = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.94–0.98), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.669) (shown in Fig. 12). The intra-class reliability of MT for VL, GM, VI was excellent (ICC = 0.96 for VL, 95% CI: 0.90–0.98, ICC = 0.97 for GM, 95% CI: 0.92–0.99, ICC = 0.98 for VI, 95% CI: 0.95–0.99, respectively).

Fig. 12.

Forest plot of intra-class reliability of muscle thickness on ultrasound by muscles. * The Wilson 2019-1 means that the subject were 39 healthy older patients, and the Wilson 2019-2 means that the subjects were 31 frail older patients in this article.

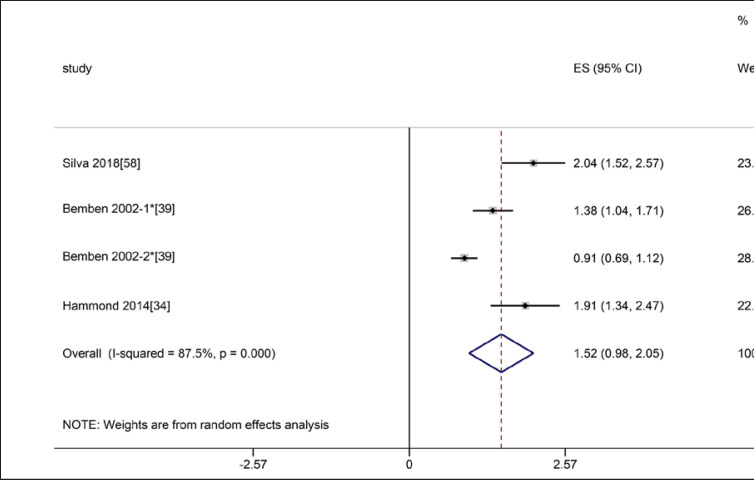

Four studies referred to CSA of muscles involving RF, BB, and VL. In the three studies involved RF, the intra-class reliability was excellent (ICC = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.76–0.97), with statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 87.5%, p = 0.000) (shown in Fig. 13). The intra-class reliability of CSA for VL and BB was excellent (ICC = 0.998 for VL, ICC = 0.99 for BB).

Fig. 13.

Forest plot of intra-class reliability of rectus femoris cross-section area on ultrasound. * The Bemben 2002-1 means that the subjects were 38 postmenopausal women, and the Bemben 2002-2 means that the subjects were 85 older men and women in this article.

The Inter-Class Reliability of US to Evaluate Muscle Mass in Older Adults

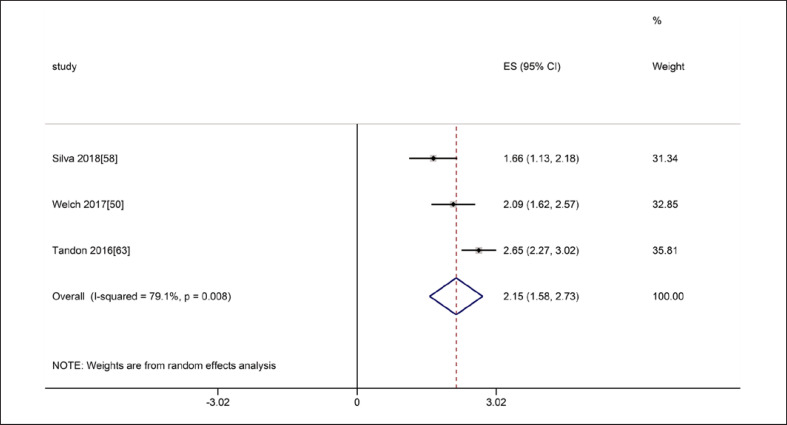

Regarding inter-rater reliability, four studies referred to the thickness of the QF. In the three studies involving ICC of QF, the meta-analyses of MT showed that the inter-class reliability was excellent (ICC = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.92–0.99), with statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 79.1%, p = 0.008) (shown in Fig. 14). Another study evaluated the reliability with the κ value, and the result also indicated high reliability (κ = 0.936) [68].

Fig. 14.

Forest plot of inter-class reliability of quadriceps femoris thickness on ultrasound.

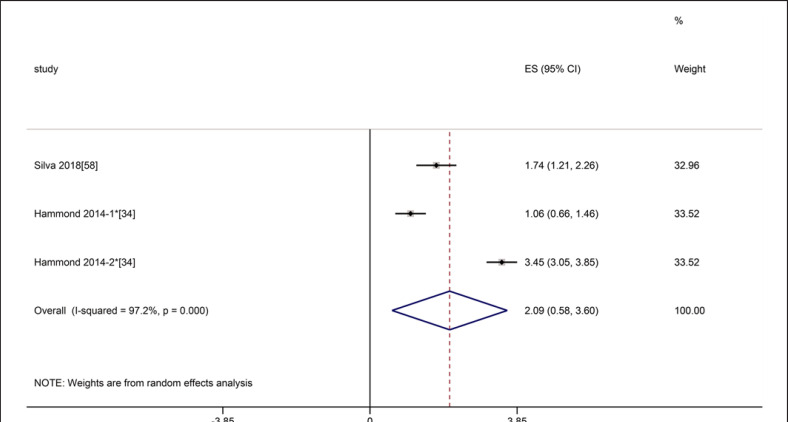

Two studies referred to CSA of RF, the meta-analyses showed that the inter-class reliability was excellent (ICC = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.52–1.0), with statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 97.2%, p = 0.000) (shown in Fig. 15). One study referred to MT of RF and VI, the results showed excellent inter-class reliability for MT (ICC = 0.93 for RF 95% CI: 0.85–0.97, ICC = 0.92 for VI, 95% CI: 0.84–0.97, respectively) [58]. A study involving inter-transducer reliability showed excellent reliability (ICC = 0.982) [34].

Fig. 15.

Forest plot of inter-class reliability of rectus femoris cross-section area on ultrasound. * The Hammond 2014-1 means the inter-class reliability between novice operator and experienced operator 1, and the Hammond 2014-2 means the inter-class reliability between experienced operator 1 and experienced operator 2.

Discussion/Conclusion

As an affordable and feasible technique, US can be used in the community and different clinical settings, such as outpatient, inpatient, and bedside [74]. In our review, 55% of the studies were conducted in the community or laboratory and 40% in clinical practice. More research on the evaluation of muscle mass using ultrasound in sarcopenia has emerged. This review aimed to update the evidence regarding the validity and reliability of ultrasound to assess muscle mass in sarcopenia in older adults, to better understand the current state, and find out the future research directions.

Our results found that the diagnostic value of US for low muscle mass or sarcopenia was moderate with RF or GM thickness on US and low with QF or VI thickness. The ultrasound-derived prediction equation with QF thickness had a moderate diagnostic performance for sarcopenia. The CSA of the RF had a moderate diagnostic performance for low muscle mass. The ultrasound-derived prediction equation based on the combination of multiple limb muscle CSA adjusted for sex, body weight, and height had a very high predictive power for sarcopenia. When the comparison was DXA or BIA, there was a low-to-moderate correlation between muscle mass and MT or CSA on ultrasound. When the comparison was CT or MRI, or when the muscle mass from DXA or BIA was compared with ultrasound-predicted muscle mass, the correlation was high to very high. The meta-analyses showed that the inter-and intra-class reliability was good. Ultrasound is a reliable and valid imaging method that quantitatively assesses muscle mass in sarcopenia in older people. In the included studies, three studies compared the association of muscle mass and ultrasound parameters between bilateral sides, and the results were controversial. Therefore, further studies are required.

US is a potentially promising method to diagnose sarcopenia. The clinical use is limited by the lack of a standardized protocol and validated cutoff points. Therefore, multicenter studies with large samples are needed. Moreover, new ultrasonic technology, such as elastosonography and artificial intelligence, has been widely used in the diagnosis of diseases. Elastosonography can estimate muscle stiffness, predicting increased fibrosis or intramuscular adipose tissue in sarcopenia. Artificial intelligence can detect changes in muscle architecture and composition and might be helpful for the standardized measurement of muscle mass. Therefore, we believed new ultrasonic technology might be the future direction in the diagnosis of sarcopenia.

Sarcopenia is a relatively new term, and its interpretation is in progress. The diagnostic methods varied in different studies, and the most common gold standards were BIA and DXA. CT, MRI, or mid-arm muscle circumference was used in a few studies. In this review, the most commonly used parameter was MT. The most commonly used muscles were the lower appendicular skeletal muscles, especially the quadriceps femoris. The reasons may be that they are convenient to expose, accessible, and save time, which is conducive to some occasions such as community screenings. More importantly, as the main weight-bearing muscles, lower appendicular skeletal muscles are more accurate and reliable indicators of low muscle mass or sarcopenia. There were many diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, and the most commonly used diagnostic criteria were AWGS and EWGSOP in the review.

As far as we know, one systematic review has focused on the reliability and validity of US to evaluate muscles in older adults [26]. However, that review did not focus on sarcopenia, and the validity of equations derived from ultrasound to predict muscle mass in older populations could not be conformed restricted to the number of studies. Our study included six relevant studies and supported the validity of the prediction equations derived from ultrasound. Most of the studies in the review had high methodological quality scores. We found that the issues in included studies were mainly related to the blind final assessor, inception cohort, and timeframe. The application of ultrasound should be standardized further.

A limitation of our review was the high heterogeneity in different studies, such as the definition of sarcopenia, reference methods, muscle evaluation, ultrasound modality, statistical analysis, etc. Although we performed the meta-analysis, subgroup analysis could not be conducted restricted to the number of studies on some occasions, even if statistical heterogeneity existed. Second, we focused on the muscle mass without muscle quality. The quantity and quality of the muscles are involved in sarcopenia; therefore, studies on muscle quality need to be conducted in the future. Third, the muscle mass showed a significant gender difference; experts from Asian and European countries had different opinions on the definition and evaluation of sarcopenia, and studies from different regions may be inconsistent; considering different conditions in the community and clinical practice, it remains a question whether there was a difference between the results from community and clinical practice. We did not perform subgroup analysis on these issues owing to insufficient number of studies in some subgroups. Further analyses based on different genders, regions, and settings are also needed.

In conclusion, ultrasonography is a reliable and valid diagnostic method for the quantitative assessment of appendicular muscle mass in sarcopenia in older people. The thickness and CSA of RF or GM seem to be proper ultrasound parameters to predict muscle mass in the sarcopenia. Multicenter studies with large samples and the application of new ultrasonic techniques will be the future research directions.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61971447), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (JQ18023), and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2020-I2M-C&T-B-035).

Author Contributions

Research design: Meng Yang; data collection: Ruina Zhao, Xuelan Li, and Na Su; data analysis: Ruina Zhao and Xuelan Li; manuscript drafting: Ruina Zhao and Xuelan Li; consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): Yuxin Jiang, Jianchu Li, Lin Kang, and Yewei Zhang.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Tao Xu for his support in the statistical analysis. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61971447), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (JQ18023), and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2020-I2M-C&T-B-035).

References

- 1.Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr. 1997 May;127((5)):990s–91s. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.990S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anker SD, Morley JE, Haehling S. Welcome to the ICD-10 code for sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016 Dec;7((5)):512–514. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2020 Mar;21((3)):300–7.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rong S, Wang L, Peng Z, Liao Y, Li D, Yang X, et al. The mechanisms and treatments for sarcopenia: could exosomes be a perspective research strategy in the future? J cachexia, sarcopenia Muscle. 2020 Apr;11((2)):348–365. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393((10191)):2636–2646. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019 Jan 1;48((4)):601. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu R, Wong M, Leung J, Lee J, Auyeung TW, Woo J, et al. Incidence, reversibility, risk factors and the protective effect of high body mass index against sarcopenia in community-dwelling older Chinese adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014 Feb;14((Suppl 1)):15–28. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frontera WR, Rodriguez Zayas A, Rodriguez N. Aging of human muscle: understanding sarcopenia at the single muscle cell level. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2012 Feb;23((1)):201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciciliot S, Rossi AC, Dyar KA, Blaauw B, Schiaffino S. Muscle type and fiber type specificity in muscle wasting. Int J Biochem Cel Biol. 2013 Oct;45((10)):2191–2199. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verdijk LB, Snijders T, Drost M, Delhaas T, Kadi F, van Loon LJC, et al. Satellite cells in human skeletal muscle; from birth to old age. Age. 2014 Apr;36((2)):545–557. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9583-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papadopoulou SK. Sarcopenia: A Contemporary Health Problem among Older Adult Populations. Nutrients. 2020;12((5)):1293. doi: 10.3390/nu12051293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tieland M, Trouwborst I, Clark BC. Skeletal muscle performance and ageing. J cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018 Feb;9((1)):3–19. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayhew AJ, Raina P. Sarcopenia: new definitions, same limitations. Age Ageing. 2019 Sep 1;48((5)):613–614. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shafiee G, Keshtkar A, Soltani A, Ahadi Z, Larijani B, Heshmat R, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in the world: a systematic review and meta- analysis of general population studies. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;16((1)):21. doi: 10.1186/s40200-017-0302-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European working group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing. 2010 Jul;39((4)):412–423. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albano D, Messina C, Vitale J, Sconfienza LM. Imaging of sarcopenia: old evidence and new insights. Eur Radiol. 2020 Apr;30((4)):2199–2208. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06573-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sconfienza LM. Sarcopenia: ultrasound today, smartphones tomorrow? Eur Radiol. 2019 Jan;29((1)):1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennison EM, Sayer AA, Cooper C. Epidemiology of sarcopenia and insight into possible therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13((6)):340–347. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw SC, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology of sarcopenia: determinants throughout the lifecourse. Calcified Tissue Int. 2017 Sep;101((3)):229–247. doi: 10.1007/s00223-017-0277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ismail C, Zabal J, Hernandez HJ, Woletz P, Manning H, Teixeira C, et al. Diagnostic ultrasound estimates of muscle mass and muscle quality discriminate between women with and without sarcopenia. Front Physiol. 2015;6:302. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tournadre A, Vial G, Capel F, Soubrier M, Boirie Y. Sarcopenia. Joint bone Spine. 2019 May;86((3)):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer J, Morley JE, Schols AM, Ferrucci L, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Dent E, et al. Sarcopenia: a time for action. An SCWD position paper. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019 Oct;10((5)):956–961. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heymsfield SB, Gonzalez MC, Lu J, Jia G, Zheng J. Skeletal muscle mass and quality: evolution of modern measurement concepts in the context of sarcopenia. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015 Nov;74((4)):355–366. doi: 10.1017/S0029665115000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ticinesi A, Meschi T, Narici MV, Lauretani F, Maggio M. Muscle ultrasound and sarcopenia in older individuals: a clinical perspective. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017 Apr 1;18((4)):290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pretorius AKJ, Keating JL. Validity of real time ultrasound for measuring skeletal muscle size. Phys Ther Rev. 2008;13((6)):415–426. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nijholt W, Scafoglieri A, Jager-Wittenaar H, Hobbelen JSM, van der Schans CP. The reliability and validity of ultrasound to quantify muscles in older adults: a systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017 Oct;8((5)):702–712. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Can B, Kara M, Kara O, Ulger Z, Frontera WR, Ozcakar L, et al. The value of musculoskeletal ultrasound in geriatric care and rehabilitation. Int J Rehabil Res. 2017 Dec;40((4)):285–296. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stringer HJ, Wilson D. The role of ultrasound as a diagnostic tool for sarcopenia. J Frailty Aging. 2018;7((4)):258–261. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2018.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perkisas S, Baudry S, Bauer J, Beckwée D, De Cock AM, Hobbelen H, et al. Application of ultrasound for muscle assessment in sarcopenia: towards standardized measurements. Eur Geriatr Med. 2018;9((6)):739–757. doi: 10.1007/s41999-018-0104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park SH, Goo JM, Jo CH. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve: practical review for radiologists. Korean J Radiol. 2004 Jan-Mar;5((1)):11. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2004.5.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selistre LFA, Melo Cd S, Noronha MAd. Reliability and validity of clinical tests for measuring strength or endurance of cervical muscles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021 Jun;102((6)):1210–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukumoto Y, Ikezoe T, Taniguchi M, Yamada Y, Sawano S, Minani S, et al. Cut-off values for lower limb muscle thickness to detect low muscle mass for sarcopenia in older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:1215–1222. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S304972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abe T, Loenneke JP, Young KC, Thiebaud RS, Nahar VK, Hollaway KM, et al. Validity of ultrasound prediction equations for total and regional muscularity in middle-aged and older men and women. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015 Feb;41((2)):557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammond K, Mampilly J, Laghi FA, Goyal A, Collins EG, McBurney C, et al. Validity and reliability of rectus femoris ultrasound measurements: comparison of curved-array and linear-array transducers. J Rehabil Res Development. 2014 2014;51((7)):1155–1164. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2013.08.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabatino A, Regolisti G, di Mario F, Ciuni A, Palumbo A, Peyronel F, et al. Validation by CT scan of quadriceps muscle thickness measurement by ultrasound in acute kidney injury. J Nephrol. 2020;33((1)):109–117. doi: 10.1007/s40620-019-00659-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson TJ, Gore EF, Vadaszy N, Nixon DGD, Watson EL, Smith AC. Utility of ultrasound as a valid and accurate diagnostic tool for sarcopenia sex-specific cutoff values in chronic kidney disease. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;40((3)):457–467. doi: 10.1002/jum.15421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vahlgren J, Karlsen A, Scheel FU, Loeb MR, Perez A, Beyer N, et al. Using ultrasonography to detect loss of muscle mass in the hospitalized geriatric population. Translational Sports Med. 2019;2((5)):287–293. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isaka M, Sugimoto K, Yasunobe Y, Akasaka H, Fujimoto T, Kurinami H, et al. The usefulness of an alternative diagnostic method for sarcopenia using thickness and echo intensity of lower leg muscles in older males. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2019;20((9)):1185.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bemben MG. Use of diagnostic ultrasound for assessing muscle size. J Strength Conditioning Res. 2002 Feb;16((1)):103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abe T, Fujita E, Thiebaud RS, Loenneke JP, Akamine T. Ultrasound-derived forearm muscle thickness is a powerful predictor for estimating DXA-derived appendicular lean mass in Japanese older adults. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016 Sep;42((9)):2341–2344. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Hu Y, Tian G. Ultrasound measurements of gastrocnemius muscle thickness in older people with sarcopenia. Clin Interventions Aging. 2018 2018;13:2193–2199. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S179445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hida T, Ando K, Kobayashi K, Ito K, Tsushima M, Kobayakawa T, et al. <Editors' Choice> ultrasound measurement of thigh muscle thickness for assessment of sarcopenia. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2018 Nov;80((4)):519–527. doi: 10.18999/nagjms.80.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rustani K, Kundisova L, Capecchi PL, Nante N, Bicchi M. Ultrasound measurement of rectus femoris muscle thickness as a quick screening test for sarcopenia assessment. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019 Jul–Aug;83:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li S, Li H, Hu Y, Zhu S, Xu Z, Zhang Q, et al. Ultrasound for measuring the cross-sectional area of biceps brachii muscle in sarcopenia. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17((18)):2947–2953. doi: 10.7150/ijms.49637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramírez-Fuentes C, Mínguez-Blasco P, Ostiz F, Sánchez-Rodríguez D, Messaggi-Sartor M, Macías R, et al. Ultrasound assessment of rectus femoris muscle in rehabilitation patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease screened for sarcopenia: correlation of muscle size with quadriceps strength and fat-free mass. Eur Geriatr Med. 2019;10((1)):89–97. doi: 10.1007/s41999-018-0130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sengul Aycicek G, Ozsurekci C, Caliskan H, Kizilarslanoglu MC, Tuna Dogrul R, Balci C, et al. Ultrasonography versus bioelectrical impedance analysis: which predicts muscle strength better? Acta Clin Belg. 2019 Jun;76((3)):204–208. doi: 10.1080/17843286.2019.1704989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barotsis N, Galata A, Hadjiconstanti A, Panayiotakis G. The ultrasonographic measurement of muscle thickness in sarcopenia. A prediction study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56((4)):427–437. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06222-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuyumcu ME, Halil M, Kara O, Cuni B, Caglayan G, Guven S, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the calf muscle mass and architecture in elderly patients with and without sarcopenia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016 Jul–Aug;65:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reeves ND, Maganaris CN, Narici MV. Ultrasonographic assessment of human skeletal muscle size. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91((1)):116–118. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0961-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welch D, Ndanyo LS, Brown S, Agyapong-Badu S, Warner M, Stokes M, et al. Thigh muscle and subcutaneous tissue thickness measured using ultrasound imaging in older females living in extended care: a preliminary study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30((5)):463–469. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0800-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung HJ, Lee YM, Kim M, Uhm KE, Lee J. Suggested assessments for sarcopenia in patients with stroke who can walk independently. Ann Rehabil Med. 2020 Feb;44((1)):20–37. doi: 10.5535/arm.2020.44.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abe T, Patterson KM, Stover CD, Geddam DAR, Tribby AC, Lajza DG, et al. Site-specific thigh muscle loss as an independent phenomenon for age-related muscle loss in middle-aged and older men and women. Age. 2014 Jun;36((3)):9634. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9634-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raj IS, Bird SR, Shield AJ. Reliability of ultrasonographic measurement of the architecture of the vastus lateralis and gastrocnemius medialis muscles in older adults. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012 Jan;32((1)):65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2011.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomaes T, Thomis M, Onkelinx S, Coudyzer W, Cornelissen V, Vanhees L, et al. Reliability and validity of the ultrasound technique to measure the rectus femoris muscle diameter in older CAD-patients. BMC Med Imaging. 2012;12((1)):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Souza VA, Oliveira D, Cupolilo EN, Miranda CS, Colugnati FAB, Mansur HN, et al. Rectus femoris muscle mass evaluation by ultrasound: facilitating sarcopenia diagnosis in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease stages. Clinics. 2018;73:e392. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2018/e392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berger J, Bunout D, Barrera G, de la Maza MP, Henriquez S, Leiva L, et al. Rectus femoris (RF) ultrasound for the assessment of muscle mass in older people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015 Jul–Aug;61((1)):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madden KM, Feldman B, Arishenkoff S, Meneilly GS. A rapid point-of-care ultrasound marker for muscle mass and muscle strength in older adults. Age Ageing. 2021;50((2)):505–510. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silva CRS, Costa ADS, Rocha T, de Lima DAM, do Nascimento T, de Moraes SRA, et al. Quadriceps muscle architecture ultrasonography of individuals with type 2 diabetes: reliability and applicability. PLoS One. 2018;13((10)):e0205724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abe T, Thiebaud RS, Loenneke JP, Young KC. Prediction and validation of DXA-derived appendicular lean soft tissue mass by ultrasound in older adults. Age. 2015 Dec;37((6)):114. doi: 10.1007/s11357-015-9853-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abe T, Loenneke JP, Thiebaud RS, Fujita E, Akamine T, Loftin M, et al. Prediction and validation of DXA-derived appendicular fat-free adipose tissue by a single ultrasound image of the forearm in Japanese older adults. J Ultrasound Med. 2018 Feb;37((2)):347–353. doi: 10.1002/jum.14343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gulyaev NI, Akhmetshin IM, Gordienco AV, Kulikov AN. The possibilities of ultrasound testing in diagnostics of sarcopenia in older patients with chronic heart failure. Adv Gerontol. 2019;32((6)):1039–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawai H, Kera T, Hirayama R, Hirano H, Fujiwara Y, Ihara K, et al. Morphological and qualitative characteristics of the quadriceps muscle of community-dwelling older adults based on ultrasound imaging: classification using latent class analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018 Apr;30((4)):283–291. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0781-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tandon P, Low G, Mourtzakis M, Zenith L, Myers RP, Abraldes JG, et al. A model to identify sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Oct;14((10)):1473–80.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuguchi S, Asahi R, Kamo T, Azami M, Ogihara H. Gastrocnemius thickness by ultrasonography indicates the low skeletal muscle mass in Japanese elderly people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020 Sep–Oct:104093. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abe T, Thiebaud RS, Loenneke JP, Fujita E, Akamine T. DXA-rectified appendicular lean mass: development of ultrasound prediction models in older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22((9)):1080–1085. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamada M, Kimura Y, Ishiyama D, Nishio N, Abe Y, Kakehi T, et al. Differential characteristics of skeletal muscle in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2017 Sep 1;18((9)):807.e9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu S, Lin W, Chen S, Qi H, Wang S, Zhang A, et al. The correlation of muscle thickness and pennation angle assessed by ultrasound with sarcopenia in elderly Chinese community dwellers. Clin Interventions Aging. 2019;14:987–996. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S201777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sato Y, Shiraishi H, Nakanishi N, Zen K, Nakamura T, Yamano T, et al. Clinical significance of rectus femoris diameter in heart failure patients. Heart Vessels. 2020 May;35((5)):672–680. doi: 10.1007/s00380-019-01534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson DV, Moorey H, Stringer H, Sahbudin I, Filer A, Lord JM, et al. Bilateral anterior thigh thickness: a new diagnostic tool for the identification of low muscle mass? J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2019 Oct;20((10)):1247–53.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strasser EM, Draskovits T, Praschak M, Quittan M, Graf A. Association between ultrasound measurements of muscle thickness, pennation angle, echogenicity and skeletal muscle strength in the elderly. Age. 2013 Dec;35((6)):2377–2388. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9517-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]