ABSTRACT

Background:

Attention deficit and hyperactive disorder (ADHD) often co-exist with substance use disorders (SUD) both in adolescents and adults. Untreated ADHD can lead to multiple relapses, sociooccupational dysfunction and may worsen the outcome of SUD. ADHD is often underdiagnosed in the adult population. Therefore, the present study was intended to determine the types, patterns, and factors related to drug dependence among different age groups and to estimate the prevalence of adult ADHD in SUD patients in North East India.

Materials and Methods:

This is a cross-sectional hospital-based study carried out in patients diagnosed with SUD as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Disorders, 5th Edition. Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (v1.1) Symptom Checklist was applied to screen for symptoms of adult ADHD in the patients.

Results:

In the age group of 18–29 years, 82.7% of patients were diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD), while 63.9% of the subjects in the age group of 30–49 years patients suffered from Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). All patients of age 50 years and above were AUD. Our study showed that 24.3% of the total study population had the presence of adult ADHD. Symptoms of Adult ADHD were found in a higher proportion among OUD (28.7%) in comparison to OUD (11.5%).

Conclusion:

The association of adult ADHD with OUD has been around three times than the AUD group. Hence young people (18–29 years) diagnosed with OUD need to be screened for adult ADHD and should be treated for the same for better abstinence and to prevent complications.

Keywords: Adult ADHD, alcohol use disorder, opioid use disorder

Inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity are the fundamental symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which is a diverse behavioral condition. ADHD symptoms are prevalent throughout the population, with a prevalence ranging from 5.9% to 7.1%.[1] According to the studies, 10%–70% of those with ADHD continue to have it throughout adulthood.[2] Since the symptoms of ADHD can overlap with those of other diseases, many young persons with ADHD will struggle in adulthood.[3] In the adult population, the frequency of ADHD ranges from 2.5% to 5%.[4] ADHD may be one of the risk factors for substance use disorders (SUDs) due to the impulsivity associated with the disease.

Researchers began focusing on the incidence of ADHD and SUD comorbidity in the 1990s in an attempt to link specific treatment modalities to client characteristics and gain a better understanding of treatment outcomes.[5] In both adolescents and adults, ADHD was found to be a substantial risk factor for SUD.[6,7] In comparison to alcohol and other illicit drugs, smoking was done more frequently by ADHD patients with 21% of ADHD probands were daily smokers in comparison to 16% of control.[8] In another study conducted by DeAlwis et al., after controlling for conduct disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and other sociodemographic factors, substance use and SUD were found to be strongly linked with ADHD.[9]

In different earlier studies, the co-occurrence of ADHD symptoms was found ranging from 33.1% of patients with methadone maintenance,[10] 35% in patients with cocaine misuse[11] to 45% among moderate polydrug users.[12]

In a study conducted by Schubiner and et al., 24% of substance-abusing participants fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for ADHD, whereas 39% met criteria for conduct disorder.[13] In a survey conducted, the Adult ADHD Self Report Scale (ASRS v1.1)[14] was used to test 1057 heroin dependent patients on opioid substitution treatment for adult ADHD symptoms. A total of 19.4% of the patients were found to have both adult ADHD symptoms and heroin addiction.[15] In another meta-analysis, 23.1% (CI: 19.4-27.2%) of all SUD individuals fulfilled DSM criteria for concomitant ADHD.[16]

According to a UN report, India has one million heroin users registered, with an unofficial estimate of five million. Attention-Deficit/Hyperkinetic Disorder (ADHD) has been linked to an earlier onset and severity of alcohol use disorders.[17] Bhat et al.[18] conducted a study on sociodemographic profile, the pattern of opioid use, and clinical profile in patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) who were attending the de-addiction center of a tertiary care hospital in North India and found that the psychiatric comorbidity was present in 41.88% of the patients with ADHD as the most common psychiatric comorbidity amounting to 24.32%. In a study on Adult ADHD in Patients with SUD in Southern India, Ganesh S et al.[19] discovered that 56.25% of the study group screened positive for “likely ADHD,” while 21.7% screened positive for “highly likely ADHD” and that the prevalence of “likely ADHD” was markedly higher among the early-onset group. In individuals who are opioid abusers, patients with adult ADHD have significantly more severe opioid dependence and less abstinence.[20]

To the best of our knowledge, there are few prevalence studies on ADHD in India and even fewer studies on the comorbidity of substance abuse and ADHD. Successful ADHD management can help to lessen the intensity of substance abuse and its consequences, as well as change the trajectory of the abuse. SUDs are more common in India's north-eastern states. In a country with such a diverse culture as India, research conducted in one section of the country may not be applicable in another.

As a result, the purpose of this study was to find out how common adult ADHD is among people who have been diagnosed with SUD.

Aims and objects

To determine the pattern and factors related to drug dependence among a hospital-based population. To estimate the prevalence of adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in the SUD group population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It was a cross-sectional study carried out in the Department of Psychiatry of a Tertiary Care Hospital with a high attendance of persons with SUD. The study was conducted from September 2018 to August 2020.

All consecutive patients aged between 18 and 65 years attending the Department of Psychiatry who were diagnosed with SUD as per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)[21] were taken up for the study. Research Ethics Board's approval was taken before the commencement of the study. Informed consent was obtained from all those were willing to take part in the study. Any patient who was having any comorbid medical, neurological and/or psychiatric illness was excluded from the study sample. Patients under intoxication and having active withdrawal syndrome were assessed after their respective clinical states were over.

Data on age, sex, place of residence, religion, marital status, education, employment status, type of substance use, family income, family type was obtained using a semi-structured proforma developed by the authors. Modified Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale, revised for 2016[22] was used for determining the socioeconomic class of patients.

Adult ASRS-v1.1 Symptom Checklist[14] was used to screen for adult ADHD. The symptom checklist is an instrument which consists of eighteen questions which will be asked about the person's conduct in the last 6 months from which screening of adult ADHD is done. Six of the eighteen questions were most predictive of symptoms which are consistent with ADHD. These six questions are the basis for the ASRS v1.1 Screener and are also Part A of the Symptom Checklist. Part B of the Symptom Checklist contains the rest twelve questions. If four or more marks appear in the darkly shaded boxes within Part A then the patient has symptoms highly consistent with adult ADHD.

As the Adult ASRS-v1.1 Symptom Checklist is a self-administered scale, it was translated to the local language and validated by a team of Clinical Psychologists of the Institute.

Internal consistency of ASRS v1.1 Symptom Checklist items was found to be high, with Cronbach's α coefficient reliability of 0.93 and concurrent validity of 0.72.[23]

Treatment as usual was given to all patients irrespective of whether they participated in the study or not.

Descriptive and inferential statistical analysis has been carried out in the present study. Results on continuous measurement like age distribution are presented as mean ± standard devition and results on categorical measurements such as gender, religion, educational status, marital status, SUD, and indication of adult ADHD were presented in frequency and percentages.

Chi-square/Fisher's exact test was used to find the association between study parameters such as between indication of Adult ADHD, substance use, education, family type, and gender distribution. P < 0.05 is taken as significant.

RESULTS

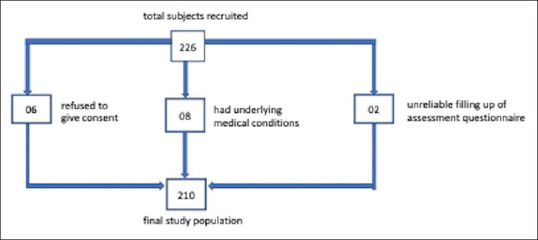

A total of 226 patients of age group 18–65 years who were diagnosed with SUD according to DSM-5[21] were taken up for the study. However, six patients refused to give consent and 8 patients were excluded due to underlying medical conditions and two patients were excluded due to unreliable filling up of the assessment questionnaire. Hence the final study population taken up for study was 210 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients recruitment

Among the study population of 210, the maximum number of patients were in the age group of 30–49 years (51.4%) followed by age group of 18–29 years (38.6%) while the least number of patients were in the age group of 50–65 years (10.0%). The mean age was 34.5 years with a standard deviation of 11.3. Males (98.1%) dominated the sample while females were 1.9%. Socioeconomic class calculated using Modified Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale, revised for 2016[22] shows that 57.1% of the population belonged to upper lower class, 28.6% belong to lower class, 10.5% belong to lower middle class while only 1.9% of the population belonged to upper and upper-middle class each. Equal proportion of the patients belonged to both urban and rural locality. About 62.9% were married, 31.9% were unmarried, 5.2% were divorced or separated, or widow or widower.

Only 24.3% of the sample completed their graduation or has received higher degrees.

More people belonged to the nuclear family (62.4%) than those belonging to joint family (37.6%).

Majority of the study population were self-employed or were doing private job (41.0%), followed by government job holders (26.2%), unemployed (24.3%), and students (8.6%).

Majority of patients were alcohol users (45.7%) and opioid users (44.8%) followed by other substance users (9.5%) which included polysubstance users and cannabis users [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic variables of patients

| Sociodemographic profile | Number of patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| 18-29 | 81 (38.6) |

| 30-49 | 108 (51.4) |

| 50-65 | 21 (10.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 206 (98.1) |

| Female | 4 (1.9) |

| Locality | |

| Urban | 105 (50.0) |

| Rural | 105 (50.0) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 132 (62.9) |

| Unmarried | 67 (31.9) |

| Divorced/separated/widower/widow | 11 (5.2) |

| Education | |

| Primary education and below | 6 (2.9) |

| Middle education | 45 (21.4) |

| Matriculation | 54 (25.7) |

| Higher secondary | 54 (25.7) |

| Graduation and above | 51 (24.3) |

| Occupation | |

| Student | 18 (8.6) |

| Unemployed | 51 (24.3) |

| Self-employed/private job | 86 (41.0) |

| Government job | 55 (26.2) |

| Type of substance use | |

| Alcohol | 96 (45.7) |

| Opioids | 94 (44.8) |

| Others | 20 (9.5) |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear | 131 (62.4) |

| Joint | 79 (37.6) |

| Socioeconomic class | |

| Lower | 60 (28.6) |

| Upper lower | 120 (57.1) |

| Lower middle | 22 (10.5) |

| Upper middle | 4 (1.9) |

| Upper | 4 (1.9) |

Significantly more patients in the age group of 18–29 years misused opioids than alcohol (82.7%) while 63.9% of the middle age group of 30–49 years misused alcohol (Chi-square 94.528 and P = 0.000).

Students (88.9%) and unemployed (60.8%) people were significantly indulged in opioid use, while more of patients who are government job holders (70.9%) were alcohol users (Chi-square 37.115, P = 0.000) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution among the study population based on type of substance use

| Sociodemographic profile | Type of substance use | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Alcohol, n (%) | Opioids, n (%) | Others, n (%) | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 18-29 | 6 (7.4) | 67 (82.7) | 8 (9.9) | 0.000 |

| 30-49 | 69 (63.9) | 27 (25.0) | 12 (11.1) | |

| 50-65 | 21 (100) | 0 | 0 | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Student | 0 | 16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 0.000 |

| Unemployed | 16 (31.4) | 31 (60.8) | 4 (7.8) | |

| Self-employed/private job | 41 (47.7) | 34 (39.5) | 11 (12.8) | |

| Government job | 39 (70.9) | 13 (23.6) | 3 (5.5) | |

The symptoms of adult ADHD were present in 24.3% of the study population while 75.7% of the study population did not show any symptoms of adult ADHD [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution among the study population based on indication of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder distribution of patients studied

| Indication of adult ADHD | Number of patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Present | 51 (24.3) |

| Absent | 159 (75.7) |

ADHD – Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

ADHD symptoms were significantly more prevalent in the younger age group of 18–29 years (30.9%) as opposed to others (23.1% in the age group of 30–49 years and 4.8% group of 50–65 years (Chi-square 6.336 and P = 0.042).

With respect to the presence of adult ADHD, there was no statistical difference between the males (24.3%) and females (25.0%).

Urban population exhibited more presence of adult ADHD than rural population (28.6% vs. 20.0%) (Chi-square 2.098, P = 0.148).

The presence of adult ADHD was more in patients who are divorced/separated/widow/widower (81.8%), unmarried (31.3%) and less in patients who are married (15.9%). (Chi-square 26.653, P = 0.000)

Among patients who belonged to nuclear families, 21.4% have the presence of adult ADHD while among patients who belonged to joint families 29.1% have the presence of adult ADHD (Chi-square 1.606 and P = 0.205).

The presence of adult ADHD was more among patients who have studied till higher secondary (35.2%), while it was low among matriculate (24.1%) and those who are graduates or have studied more (17.6%). (Chi-square 5.351, P = 0.253). However, the comparison does not yield any significance.

The presence of adult ADHD was high among patients who are students (33.3%) and unemployed (31.4%) while it was low among patients who are self-employed/private job holders (20.9%) and Government job holders (20.0%).(Chi-square 3.270 and P = 0.352).

The presence of adult ADHD was significantly high among patients with opioid use (28.7%) and poly-substance and cannabis users (65.0%) and while it was low among patients with alcohol use (11.5%) (Chi-square 27.627 with P = 0.000) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Indication of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in relation to sociodemographic variables

| Sociodemographic profile | Indication of adult ADHD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Present, n (%) | Absent, n (%) | ||

| Age group (years) | |||

| 18-29 | 25 (30.9) | 56 (69.1) | 0.042 |

| 30-49 | 25 (23.1) | 83 (76.9) | |

| 50-65 | 1 (4.8) | 20 (95.2) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 50 (24.3) | 156 (75.7) | 1.000 |

| Female | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 21 (15.9) | 111 (84.1) | 0.000 |

| Unmarried | 21 (31.3) | 46 (68.7) | |

| Divorced/separated/widower/widow | 9 (81.8) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Education | |||

| Primary education and below | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | 0.253 |

| Middle education | 9 (20.0) | 36 (80.0) | |

| Matriculation | 13 (24.1) | 41 (75.9) | |

| Higher secondary | 19 (35.2) | 35 (64.8) | |

| Graduation and above | 9 (17.6) | 42 (82.4) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Student | 6 (33.3) | 12 (66.7) | 0.352 |

| Unemployed | 16 (31.4) | 35 (68.6) | |

| Self-employed/private job | 18 (20.9) | 68 (79.1) | |

| Government job | 11 (20.0) | 44 (80.0) | |

| Type of substance use | |||

| Alcohol | 11 (11.5) | 85 (88.5) | 0.000 |

| Opioids | 27 (28.7) | 67 (71.3) | |

| Others | 13 (65.0) | 7 (35.0) | |

| Family type | |||

| Nuclear | 28 (21.4) | 103 (78.6) | 0.205 |

| Joint | 23 (29.1) | 56 (70.9) | |

ADHD – Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

DISCUSSION

The current study focussed to find out the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of adult ADHD among patients diagnosed with SUD using Adult ASRS-v1.1 Symptom Checklist. The study also explored the sociodemographic characteristics of the study samples and its association with the presence and absence of adult ADHD.

The maximum number of patients was in the age group of 30–49 years (51.4%) followed by 18–29 years (38.6%). In a study conducted by Rather YH,[24] it was found that the mean age of patients was 26.8 years with standard deviation of 7.37 and the most common age of initiation was 11–20 years (76.8%). This is also supported by another study conducted by Bhat et al.[18] which found that the mean age of the patients was 27.55 years with standard deviation of 7.26 with most of the patients (83.78%) were in-between 20 and 40 years of age.

Male preponderance was seen in the study with male patients constituting 98.1% and female patients were 1.9%. This finding is similar to the study done by Bhat et al.[18] which also showed male preponderance with male patients constituting 97.5% of study population.

About 57.1% of the patients were from a upper-lower socioeconomic class and 28.6% of the patients belonged to lower socioeconomic class indicating lower income group consistent with earlier studies conducted by Rather et al.[24]

Our study found locality does not affect substance use as both urban and rural locality has equal number of SUD patients.

Majority of the study population are either self-employed or having private job with small earnings while 24.3% of patients are unemployed. Problematic substance use, according to Henkel,[25] increases the likelihood of unemployment and reduces the chances of finding and keeping a job. People with SUD comorbid with ADHD are significantly more underachievers which is supported by the study conducted by Molina and Pelham.[26] A study conducted by Rhee and Rosenheck[27] found that current opioid disorder was associated with lower odds of being employed compared to never experiencing as was past OUD. Adults with current OUD have much lower HRQOL (Health-Related Quality of Life) and are more likely to be unemployed, while adults with the previous OUD have a significant residual impairment.

Our study shows that 24.3% of study population has the presence of adult ADHD while 75.7% has the absence of adult ADHD, which is similar to that of earlier studies[13,15,16] which described the presence of ADHD as 24%, 19.4%, and 23.1%, respectively, among the participants.

ADHD in subjects of substance use disorders

The present study shows that the presence of adult ADHD is very high among opioid users (28.7%) while it is low among alcohol users (11.5%) which is similar to findings of the study by Lugoboni et al.[15] The presence of adult ADHD was also very high among other substance users (65.0%) which included polysubstance users and cannabis users which might be because substance use may help them in attenuating their mood and help them sleep.[28] They try multiple substances one after another as they might get tolerant to one drug after regular use.

The maximum prevalence of adult ADHD was in the age group of 18–29 years. This is because in the age group of 18–29 years 82.7% of whom were opioid users and the presence of adult ADHD is very high among opioid users (28.7%).

Our study did not find a significant difference in the occurrence of ADHD symptoms, with respect to gender, locality, or family type similar to earlier study conducted by Schubiner et al.[13]

The study shows that among married people adult ADHD is present in 15.9% of patients, among unmarried it is 31.3%. The presence of adult ADHD is very high among divorced or separated or widow/widower (81.8%). People having adult ADHD may have difficulty in maintaining stable social relationships. They either are unable to get married or get separated even if they get married. Eakin et al.[29] observed that married adults with ADHD reported poorer overall marital adjustment and more family dysfunction than control adults. The present study shows that adult ADHD maximally prevalent in students and unemployed who also use more opioids and polysubstance than alcohol.

CONCLUSION

This is the first study to the best of our knowledge conducted in North East India with a fairly good sample size.

This study shows that the association of adult ADHD with OUD has been around three times than the AUD group. Untreated ADHD increases the likelihood of developing SUD. Low self-worth and poor executive functioning are linked to alcohol and other substance abuse, according to the addictions field. The nucleus accumbens is thought to be involved in the catecholaminergic pathways alterations in ADHD, resulting in impaired selective attention and the reward system.[30] These changes in the brain may be associated with a greater risk of substance use and dependence.[31]

ADHD symptoms frequently coexist with substance misuse in this part of the country. This coexistence may be associated with academic and occupational underachievement in the affected individuals. Untreated, it may worsen substance abuse, and related complications, compliance to treatment for deaddiction and relapse rate.[26] Early recognition and effective management of ADHD may alter the prognosis or substance misuse and improve the psychosocial function of the affected individuals.[28]

Early research has shown that ADHD and impairments related to substance use place more demand on services. Individuals who has partially remitted ADHD showed similar substance use to those with current ADHD, whereas those who have fully remitted were comparable with normal controls.[32]

So this study served the purpose of identifying and treating the SUD patients and the associated adult ADHD in the study population. This may lead to higher retention in treatment programs, higher chances of remission of SUD and a lower rate of relapse.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schweren LJ, de Zeeuw P, Durston S. MR imaging of the effects of methylphenidate on brain structure and function in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1151–64. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbett B, Stanczak DE. Neuropsychological performance of adults evidencing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;14:373–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidelines for the Treatment of adult ADHD with Psychostimulants. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/_data/assets/pdf_file/0028/444367/adult-adhd-gl.pdf .

- 4.Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04009. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.04009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tapert SF, Baratta MV, Abrantes AM, Brown SA. Attention dysfunction predicts substance involvement in community youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:680–6. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Milberger S, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV. Psychoactive substance use disorders in adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): effects of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1652–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Spencer T, Faraone SV. Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e20. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madsen AG, Dalsgaard S. Prevalence of smoking, alcohol and substance use among adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Denmark compared with the general population. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68:53–9. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2013.768293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Alwis D, Lynskey MT, Reiersen AM, Agrawal A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder subtypes and substance use and use disorders in NESARC. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1278–85. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peles E, Schreiber S, Sutzman A, Adelson M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder among former heroin addicts currently in methadone maintenance treatment. Psychopathology. 2012;45:327–33. doi: 10.1159/000336219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. History and significance of childhood attention deficit disorder in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Compr Psychiatry. 1993;34:75–82. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90050-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parrott AC, Hatton NP, Rowe KL, Watts LA, Donev R, Kissling C, et al. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric symptoms in recreational polydrug users. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2012;27:209–16. doi: 10.1002/hup.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schubiner H, Tzelepis A, Milberger S, Lockhart N, Kruger M, Kelley BJ, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder among substance abusers. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:244–51. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 18]. Available from: https://add.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/adhd-questionnaire-ASRS111.pdf .

- 15.Lugoboni F, Levin FR, Pieri MC, Manfredini M, Zamboni L, Somaini L, et al. Co-occurring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adults affected by heroin dependence: Patients characteristics and treatment needs. Psychiatry Res. 2017;250:210–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen K, van de Glind G, van den Brink W, Smit F, Crunelle CL, Swets M, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in substance use disorder patients: A meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar M, Bharadwaj B, Kuppili PP, Ramaswamy G, Majella GM, Chinnakali P, et al. Association of attention-deficit hyperkinetic disorder with alcohol use disorders in fishermen. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2017;8:S78–82. doi: 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_48_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhat BA, Dar SA, Hussain A. Sociodemographic profile, pattern of opioid use, and clinical profile in patients with opioid use disorders attending the de-addiction center of a tertiary care hospital in North India. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2019;35:173–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganesh S, Kandasamy A, Sahayaraj US, Benegal V. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with substance use disorders: A study from Southern India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39:59–62. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.198945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpentier PJ, van Gogh MT, Knapen LJ, Buitelaar JK, De Jong CA. Influence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder on opioid dependence severity and psychiatric comorbidity in chronic methadone-maintained patients. Eur Addict Res. 2011;17:10–20. doi: 10.1159/000321259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regier DA, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. The DSM-5: Classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:92–8. doi: 10.1002/wps.20050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaikh Z, Pathak R. Revised Kuppuswamy and B G Prasad socio-economic scales for 2016. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;4:997–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adler LA, Shaw DM, Spencer TJ, Newcorn JH, Hammerness P, Sitt DJ, et al. Preliminary examination of the reliability and concurrent validity of the attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder self-report scale v1.1 symptom checklist to rate symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22:238–44. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rather YH, Bashir W, Sheikh AA, Amin M, Zahgeer YA. Socio-demographic and clinical profile of substance abusers attending a regional drug de-addiction centre in chronic conflict area: Kashmir, India. Malays J Med Sci. 2013;20:31–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: A review of the literature (1990-2010) Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:4–27. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104010004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molina BS, Pelham WE., Jr Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk of substance use disorder: Developmental considerations, potential pathways, and opportunities for research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:607–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhee TG, Rosenheck RA. Association of current and past opioid use disorders with health-related quality of life and employment among US adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;199:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zulauf CA, Sprich SE, Safren SA, Wilens TE. The complicated relationship between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:436. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eakin L, Minde K, Hechtman L, Ochs E, Krane E, Bouffard R, et al. The marital and family functioning of adults with ADHD and their spouses. J Atten Disord. 2004;8:1–10. doi: 10.1177/108705470400800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell VA. Overview of animal models of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2011;(Chapter 9:Unit9.35) doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0935s54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galéra C, Pingault JB, Fombonne E, Michel G, Lagarde E, Bouvard MP, et al. Attention problems in childhood and adult substance use. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1677–83.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huntley Z, Young S. Alcohol and substance use history among ADHD adults: The relationship with persistent and remitting symptoms, personality, employment, and history of service use. J Atten Disord. 2014;18:82–90. doi: 10.1177/1087054712446171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]