Abstract

A previous meta-analysis, entitled “The association between metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer susceptibility and prognosis: an updated comprehensive evidence synthesis of 95 observational studies involving 97,795,299 subjects,” focused on all observational studies, whereas in the present meta-analysis, we focused on cohort studies to obtain more accurate and stronger evidence to evaluate the association between metabolic syndrome and its components with bladder cancer. PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched to identify studies on the association between metabolic syndrome and its components with bladder cancer from January 1, 2000 through May 23, 2021. The pooled relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to measure this relationship using a random-effects meta-analytic model. Quality appraisal was undertaken using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. In total, 56 studies were included. A statistically significant relationship was found between metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer 1.09 (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.17), and there was evidence of moderate heterogeneity among these studies. Our findings also indicated statistically significant relationships between diabetes (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.31) and hypertension (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.13) with bladder cancer, but obesity and overweight did not present a statistically significant relationship with bladder cancer. We found no evidence of publication bias. Our analysis demonstrated statistically significant relationships between metabolic syndrome and the risk of bladder cancer. Furthermore, diabetes and hypertension were associated with the risk of bladder cancer.

Keywords: Urinary bladder neoplasm, Meta analysis, Metabolic syndrome, Metabolic syndrome components, Cohort studies

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic syndrome is defined as a set of risk factors that jointly cause adverse outcomes, including type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease [1]. These risk factors are central obesity, insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentrations [2]. According to epidemiological studies, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome varies from 20% to 45% of the population, and this rate is expected to increase to approximately 53% by 2035 [3-5]. Metabolic syndrome increases with age, and women are more susceptible than men [6]. Studies have consistently shown that metabolic syndrome is associated with an increased risk of several cancers [7-10]. Furthermore, each component of metabolic syndrome (including obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia) independently increases the risk of various cancers [11].

Bladder cancer has recently been linked to metabolic syndrome [12]. Bladder cancer is the 10th most prevalent cancer worldwide, and the incidence of bladder cancer is increasing. The International Agency for Research on Cancer reported 573,278 new cases and 21,253 bladder cancer deaths in 2018 [13]. It is also associated with significant complications and mortality in many parts of the world, and it therefore imposes a high burden of disease on communities [14]. Bladder cancer is a multifactorial disease, and evidence from clinical studies suggests that metabolic syndrome may increase the risk, recurrence, and mortality of this condition. Many studies have also shown that aging and obesity are risk factors for bladder cancer [15]. Therefore, older people with chronic diseases such as metabolic syndrome are more likely to be affected by bladder cancer [16].

Research has shown that low HDL levels are an important risk factor for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Furthermore, through excess secretion of insulin, metabolic syndrome could be associated with the malignant potential of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder [17]. In addition, an association between being overweight, which is a component of metabolic syndrome, and the risk of recurrence of bladder cancer has been reported [18]. Conflicting information has been reported regarding the association between metabolic syndrome and the risk of bladder cancer in various studies. Some cohort studies have reported no statistically significant association between the components of metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer risk [19-21], whereas other studies have found statistically significant associations [19,22,23]. Meta-analyses have found that metabolic syndrome significantly increased the risk of bladder cancer [9,24].

Considering the available data, the association of metabolic syndrome and its components, including obesity, hypertension, high blood triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol levels, and insulin resistance, with bladder cancer has yet to be well enough defined to reach reliable results. Furthermore, the previous meta-analysis published in 2018 [24] focused on all observational studies, including cross-sectional studies and case-control studies, which may have more bias and lower quality than cohort studies. In this study, we focused on cohort studies to obtain more accurate and stronger evidence for the association between metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer. We also added new studies and our search was broader than those of previous studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search strategy

Initially, to identify whether studies satisfied the inclusion criteria, we screened the titles and abstracts of all studies using EndNote 20, an update from version X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). A wide search was performed of several electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science from January 1, 2000, through May 23, 2021. The search terms comprised the following keywords: “bladder cancer,” “bladder neoplasms,” “bladder carcinoma,” “bladder tumor-associated antigen,” “urothelial carcinoma,” “noninvasive bladder cancer,” “non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer,” “muscle-invasive bladder cancer,” “metabolic syndrome,” “metabolic syndrome components,” “metabolic abnormalities,” “metabolic syndrome x,” “insulin resistance,” “obesity,” “overweight,” “hypertension,” “dyslipidemia,” “diabetes mellitus,” “hypertriglyceridemia,” and “low HDL.” We also investigated the references of all articles to identify studies that were not included during the initial search. The following inclusion criteria were selected for meta-analysis: the study had a cohort study design, the primary outcome was the risk of bladder cancer (quantified as the relative risk [RR] and the 95% confidence interval [CI]) associated with metabolic syndrome, and the study was published in English. The exclusion criteria were articles of the following types: letters to the editor, case reports, intervention studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, reviews, and meta-analyses.

Study selection

Initially, to identify whether studies satisfied the inclusion criteria, we screened their titles and abstracts. For studies where this decision was difficult to make based only on their titles and abstracts, a full-text assessment was conducted. Two authors (MA and FK) screened the final full-texts, and after reading the fulltexts of all eligible articles, made a final decision for each study. In cases of disagreement, the third review author’s opinion was solicited, or the issue was resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

A structured data extraction form was used. The extracted data included: the last name of the first author, publication year, country, study purpose, sample characteristics, sample size, exposure, mean age, gender, confounders, and definitions of the components of metabolic syndrome. Data were extracted independently by the same 2 review authors (MA and FK) who conducted the study selection.

Evaluating the quality of articles

The quality of papers was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) designed for observational studies [25]. The NOS consists of 3 domains, including the selection of study groups, comparability of groups, and description of exposure and outcome. This quality assessment tool includes 8 items and star scores for each study in each domain. All items have 1 star except the comparability domain (the maximum score based on stars for comparability domain is 2). The total score of each of the articles was calculated. Then, all selected studies were categorized based on these levels: high (7-10), medium (5-6), or low quality (< 4). Two authors (MA and MS) reviewed the articles separately. The third author’s opinion was used to resolve any disagreements.

Statistical analysis

Pooled RRs and 95% CIs were calculated to measure the association of metabolic syndrome and its components with the risk of bladder cancer using a random-effects meta-analytic model. We used adjusted estimates. We used the Cochran Q-test and the I2 statistic to evaluate heterogeneity. A subgroup analysis was carried out according to gender (men and women) and weight (obesity and overweight). To identify influential studies in the meta-analysis, leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed. Publication bias was determined by a funnel plot and the Begg and Egger tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not sought because this study was based on published articles and no human or animal intervention was performed.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

Figure 1 shows the search strategy and the algorithm of study selection. According to the keywords, MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms, and Emtree terms, 5,337 studies were identified. After considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria, relevant studies were retrieved and duplicates were removed. In this process, 3,145, 185, and 84 studies were excluded after screening their titles, abstracts, and full-texts, respectively. Finally, the quality of 55 related studies that satisfied the inclusion criteria was assessed. Of these, 11 studies were performed in the United States [23,26-35], 8 studies in Sweden [19,21,36-41], 8 studies in Korea [42-49], 6 studies in the United Kingdom [20,50-54], 7 studies in Taiwan [55-61], 2 studies each in China [62,63], Japan [64,65], Italy [66,67], Scotland [68,69], and Austria [70,71], and 1 study each in Iran [72], Norway [73], Netherland [74], European and Canada [75]. The cut-point score of 7 or higher was considered as indicating studies with high quality, and scores of 5-6 indicated moderate quality. Using these criteria, 33 studies had high levels of quality and 22 had moderate levels of quality (Supplementary Material 1). Supplementary Material 2 summarizes the characteristics of selected studies.

Figure 1.

Flow chart depicting the study selection process (screening).

Metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer risk

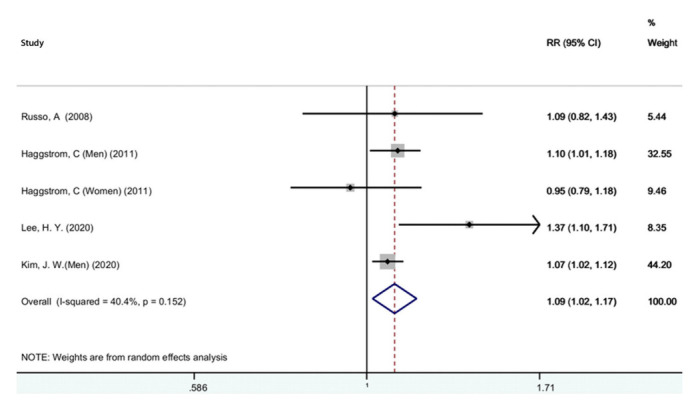

Figure 2 shows the results of the random-effects meta-analysis and the adjusted pooled RR from the 4 studies included for the association of metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer [19,45,59,67]. The results showed a statistically significant relationship between metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer (RR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.17). Furthermore, there was moderate heterogeneity between these studies (I2=40.4%; p=0.152). A sensitivity analysis showed that no single study significantly changed the pooled RR. Based on the Begg (p=0.851) and Egger (p=0.801) tests, we found no evidence of publication bias.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the association between metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer. RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Diabetes and bladder cancer risk

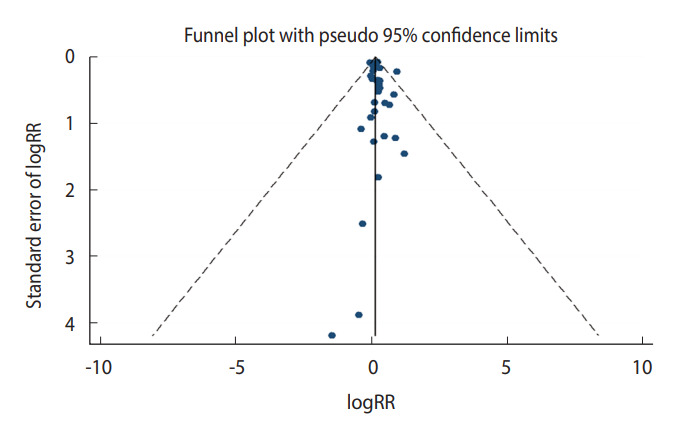

Figure 3 presents the adjusted pooled RR for the association of diabetes and bladder cancer. Thirty studies were included [20-22,28-31,34,41,46,52,53,55-58,61-66,68,69,71,72,74-76]. Based on this figure, diabetes increased the risk of bladder cancer (RR,1.23; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.31). However, there was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2=83.3%; p<0.001). Figure 4 presents the pooled adjusted RR for the association of diabetes and bladder cancer stratified by gender. According to the results, diabetes increased the risk of bladder cancer in women (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.34) and in men (RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.30). There was significant heterogeneity among women (I2=56.5%; p=0.014) and men (I2=84.5%; p<0.001), but heterogeneity was lower among women. A sensitivity analysis showed that no single study was a potential source of heterogeneity. We determined the possibility of publication bias using a funnel plot (Figure 5), as well as the Begg and Egger tests. The studies were almost symmetrically scattered on both sides of the vertical line, showing the absence of publication bias. The Begg (p=0.646) and Egger (p=0.181) tests also showed no evidence of publication bias.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the association between diabetes and bladder cancer. RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the association between diabetes and bladder cancer by gender. RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot for publication bias regarding the association between diabetes and bladder cancer. RR, relative risk.

Excessive body weight and bladder cancer risk

The results of the relationship between excessive body weight and bladder cancer stratified by obesity and overweight are shown in Figure 6. Twenty-five studies were included [19,21,23,28,32,33,35-37,39,40,42-44,47-51,54,63,70,73,74,77]. With respect to excessive body weight status, no associations between obesity (RR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.15) or overweight (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.12) and bladder cancer were found. Significant heterogeneity was observed in the obesity (I2=65.4%; p<0.001) and overweight (I2=80.2%; p<0.001) groups. Sensitivity analysis showed that the studies by Choi et al. [43] and Ko et al. [47] were considerable sources of the observed heterogeneity. The Begg (p=0.484) and Egger (p=0.684) tests showed no evidence of publication bias.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the association between overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) or obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and bladder cancer1. RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index. 1Tumors or cancer of the urinary bladder.

Hypertension and bladder cancer risk

The results for the relationship between hypertension and bladder cancer are shown in Figure 7. Six studies were included [19,37,38,56,60,73]. A statistically significant association was found between hypertension and bladder cancer (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.13). There was no evidence of heterogeneity among these studies (I2=30.3%; p=0.158). A sensitivity analysis found that no single study significantly changed the pooled RR, and the Begg (p=0.312) and Egger (p=0.139) tests showed no evidence of publication bias.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of the association between hypertension and bladder cancer. RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Scopus were searched and 55 studies were identified. Our analysis demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer, and there was moderate heterogeneity among these studies. Our findings also indicated statistically significant relationships between diabetes and hypertension and bladder cancer, but no association was found between obesity or overweight and bladder cancer.

Previous studies have reported metabolic syndrome as an essential factor for the progression of different types of cancers [78,79]. In developed countries worldwide, bladder cancer is one of most prevalent cancers, and it has been reported to show associations with metabolic syndrome risk factors including obesity, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP) [80,81]. The results of our study were similar to those of a previous meta-analysis that found a statistically significant association between metabolic syndrome and the risk of bladder cancer [24]. The result of the meta-analysis conducted by Esposito et al. [78] showed a statistically significant relationship between metabolic syndrome and risk of bladder cancer in men, but not in women. Furthermore, this study focus specifically on the metabolic syndrome subgroup (not each subgroup), since it is this subgroup for which few studies were found and a separate analysis for men and women was not reported (in contrast, for example, to the subgroup of studies on diabetes, which contained many more studies).

In our study, there was a statistically significant association between diabetes and the risk of bladder cancer in both genders. The previous meta-analysis also found that diabetes increased the risk of bladder cancer [82]. It has been proven that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia stimulate tumor growth [83] and increase the risk of urinary tract infections [82], which are associated with the risk of bladder cancer [84]. Furthermore, diabetes changes the composition of urine and bladder function, which can increase the concentration or duration of exposure to carcinogens in the urine. This may also increase the risk of bladder cancer [85-87].

In the present meta-analysis, we observed no association between obesity or overweight and bladder cancer. Some studies have similarly found no association between overweight or obesity and bladder cancer [32,51,74], but others have found positive associations [42,43,48]. Obesity is characterized by an increase in adipose tissue and is often associated with worsening of the components of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of non-communicable diseases, such as cancer [88]. However, the relationship between obesity and the risk of bladder cancer remains speculative.

We found a statistically significant relationship between hypertension and bladder cancer. The results of previous studies similarly showed an association between hypertension and urinary bladder cancer [19,89,90]. A recent nationwide population-based cohort study supported a positive association between hypertension and the subsequent development of urinary bladder cancer [60]. Hypertension, as a global public health problem, is associated with multiple medical conditions [91-93]. Animal studies have provided evidence indicating that oxidative stress might play a causative role in the pathogenesis of hypertension [94], and oxidative stress is a risk factor in the development of cancer.

We used the Q-test and the I2 statistic to detect heterogeneity. Moderate heterogeneity was found for the relationship between metabolic syndrome and the risk of bladder cancer among studies. Regarding the components of metabolic syndrome, there was also significant heterogeneity in the relationship between diabetes and bladder cancer in both genders, and between obesity or overweight and bladder cancer. There can be various reasons for heterogeneity between studies. Most likely, this heterogenicity was due to the variety of definitions of metabolic syndrome, as well as because metabolic factors may not have been directly measured by the same method. For example, studies diagnosed high BP through direct BP measurements, self-reported diagnoses of hypertension, or specific drug use. This might have resulted in high heterogeneity between studies. Other relevant sources of heterogeneity may have been differences among studies in the sample size, publication date (the eligible studies were published from 2000 to 2021), geographical area, and the study population.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that we included the most recent studies in the last 5 years. The second strength of this study is that we only assessed cohort studies in this systematic review, because cohort studies provide reliable and unbiased evidence. The third strength is that we evaluated all articles accurately to ensure that all articles were of sufficient quality for inclusion (fortunately, no articles were excluded due to quality issues). Finally, we performed subgroup analyses of diabetes, BMI, and BP, which are the most important components of metabolic syndrome, and we separately measured the effect of each of these factors on bladder cancer risk.

One of the limitations of the study is that we used studies written in the English language because non-English language studies were unavailable. The second limitation is that the studies we reviewed were from 2000 to 2021, and we did not include articles published before 2000. The reason for this is that the number of these articles was very limited and these articles did not meet our inclusion criteria.

CONCLUSION

Our analysis demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between metabolic syndrome and the risk of bladder cancer. Of the components of metabolic syndrome, diabetes and hypertension showed statistically significant relationships with the risk of bladder cancer, but there was no association between obesity or overweight and the risk of bladder cancer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the authors of the studies included in this meta-analysis; we are also deeply grateful to all the authors who kindly provided additional information for our meta-analysis.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare for this study.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Khodamoradi F, Ahmadinezhad M. Data curation: Ahmadinezhad M, Sharafoddin M, Hesari E, Arshadi M. Formal analysis: Khodamoradi F, Azizi H. Funding acquisition: None. Methodology: Khodamoradi F, Ahmadinezhad M, Azizi H. Project administration: Ahmadinezhad M, Khodamoradi F. Visualization: Ahmadinezhad M, Khodamoradi F. Writing – original draft: Ahmadinezhad M, Sharafoddin M, Hesari E, Arshadi M, Azizi H, Khodamoradi F. Writing – review & editing: Hesari E, Arshadi M, Khodamoradi F.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials are available at https://www.e-epih.org/.

Assessment of Study Quality included in the meta-analysis

Characteristics of included studies in the meta-analysis

REFERENCES

- 1.O’Neill S, O’Driscoll L. Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev. 2015;16:1–12. doi: 10.1111/obr.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang HH, Lee DK, Liu M, Portincasa P, Wang DQ. Novel insights into the pathogenesis and management of the metabolic syndrome. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020;23:189–230. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2020.23.3.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engin A. The definition and prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;960:1–17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gierach M, Gierach J, Ewertowska M, Arndt A, Junik R. Correlation between body mass index and waist circumference in patients with metabolic syndrome. ISRN Endocrinol. 2014;2014:514589. doi: 10.1155/2014/514589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansarimoghaddam A, Adineh HA, Zareban I, Iranpour S, HosseinZadeh A, Kh F. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in MiddleEast countries: meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pucci G, Alcidi R, Tap L, Battista F, Mattace-Raso F, Schillaci G. Sex- and gender-related prevalence, cardiovascular risk and therapeutic approach in metabolic syndrome: a review of the literature. Pharmacol Res. 2017;120:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montella M, Di Maso M, Crispo A, Grimaldi M, Bosetti C, Turati F, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:720. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1769-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantiello F, Cicione A, Salonia A, Autorino R, De Nunzio C, Briganti A, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes mellitus and oncological outcomes of bladder cancer: a systematic review. Int J Urol. 2015;22:22–32. doi: 10.1111/iju.12644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esposito K, Capuano A, Giugliano D. Metabolic syndrome and cancer: holistic or reductionist? Endocrine. 2014;45:362–364. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosato V, Zucchetto A, Bosetti C, Dal Maso L, Montella M, Pelucchi C, et al. Metabolic syndrome and endometrial cancer risk. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:884–889. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe J, Kakehi E, Kotani K, Kayaba K, Nakamura Y, Ishikawa S. Metabolic syndrome is a risk factor for cancer mortality in the general Japanese population: the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2019;11:3. doi: 10.1186/s13098-018-0398-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozbek E, Otunctemur A, Dursun M, Koklu I, Sahin S, Besiroglu H, et al. Association between the metabolic syndrome and high tumor grade and stage of primary urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:1447–1451. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.3.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson SL, Cohen SM. Epidemiology and etiology of bladder cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 1997;13:291–298. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199709/10)13:5<291::aid-ssu2>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saginala K, Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, Padala SA, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of bladder cancer. Med Sci (Basel) 2020;8:15. doi: 10.3390/medsci8010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg T, Young AJ, O’Keeffe-Rosetti M, McMullen CK, Nielsen ME, Murphy TE, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and recurrence of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer in older adults. Urol Oncol. 2020;38:737.e17–737.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagase K, Tobu S, Kusano S, Takahara K, Udo K, Noguchi M. The association between metabolic syndrome and high-stage primary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Curr Urol. 2018;12:39–42. doi: 10.1159/000447229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lotan Y. Metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2021;128:1–2. doi: 10.1111/bju.15322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Häggström C, Stocks T, Rapp K, Bjørge T, Lindkvist B, Concin H, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of bladder cancer: prospective cohort study in the metabolic syndrome and cancer project (MeCan) Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1890–1898. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swerdlow AJ, Laing SP, Qiao Z, Slater SD, Burden AC, Botha JL, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in patients with insulin-treated diabetes: a UK cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2070–2075. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson SC, Andersson SO, Johansson JE, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus, body size and bladder cancer risk in a prospective study of Swedish men. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2655–2660. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolcott CG, Maskarinec G, Haiman CA, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Diabetes and urothelial cancer risk: the Multiethnic Cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:551–554. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koebnick C, Michaud D, Moore SC, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Body mass index, physical activity, and bladder cancer in a large prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1214–1221. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng XF, Meng XY, Wei C, Xing ZH, Huang JB, Fang ZF, et al. The association between metabolic syndrome and bladder cancer susceptibility and prognosis: an updated comprehensive evidence synthesis of 95 observational studies involving 97,795,299 subjects. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:6263–6274. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S181178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yood MU, Oliveria SA, Campbell UB, Koro CE. Incidence of cancer in a population-based cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2009;3:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolcott CG, Maskarinec G, Haiman CA, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Diabetes and urothelial cancer risk: the Multiethnic Cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:551–554. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tripathi A, Folsom AR, Anderson KE, Iowa Women’s Health Study Risk factors for urinary bladder carcinoma in postmenopausal women. The Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer. 2002;95:2316–2323. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prizment AE, Anderson KE, Yuan JM, Folsom AR. Diabetes and risk of bladder cancer among postmenopausal women in the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:603–608. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0143-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newton CC, Gapstur SM, Campbell PT, Jacobs EJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin-use and risk of bladder cancer in a large cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2186–2191. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai GY, Park Y, Hartge P, Hollenbeck AR, Freedman ND. The association between self-reported diabetes and cancer incidence in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E497–E502. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holick CN, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Michaud DS. Prospective study of body mass index, height, physical activity and incidence of bladder cancer in US men and women. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:140–146. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cantwell MM, Lacey JV, Jr, Schairer C, Schatzkin A, Michaud DS. Reproductive factors, exogenous hormone use and bladder cancer risk in a prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2398–2401. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atchison EA, Gridley G, Carreon JD, Leitzmann MF, McGlynn KA. Risk of cancer in a large cohort of U.S. veterans with diabetes. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:635–643. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andreotti G, Hou L, Beane Freeman LE, Mahajan R, Koutros S, Coble J, et al. Body mass index, agricultural pesticide use, and cancer incidence in the Agricultural Health Study cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1759–1775. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9603-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolk A, Gridley G, Svensson M, Nyrén O, McLaughlin JK, Fraumeni JF, et al. A prospective study of obesity and cancer risk (Sweden) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:13–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1008995217664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teleka S, Jochems SH, Häggström C, Wood AM, Järvholm B, Orho-Melander M, et al. Association between blood pressure and BMI with bladder cancer risk and mortality in 340,000 men in three Swedish cohorts. Cancer Med. 2021;10:1431–1438. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stocks T, Van Hemelrijck M, Manjer J, Bjørge T, Ulmer H, Hallmans G, et al. Blood pressure and risk of cancer incidence and mortality in the Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer Project. Hypertension. 2012;59:802–810. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.189258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samanic C, Chow WH, Gridley G, Jarvholm B, Fraumeni JF., Jr Relation of body mass index to cancer risk in 362,552 Swedish men. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:901–909. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukanova A, Björ O, Kaaks R, Lenner P, Lindahl B, Hallmans G, et al. Body mass index and cancer: results from the Northern Sweden Health and Disease Cohort. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:458–466. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of cancer following hospitalization for type 2 diabetes. Oncologist. 2010;15:548–555. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bae WJ, Choi JB, Moon HW, Park YH, Cho HJ, Hong SH, et al. Influence of diabetes on the risk of urothelial cancer according to body mass index: a 10-year nationwide population-based observational study. J Cancer. 2018;9:488–493. doi: 10.7150/jca.22107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi JB, Kim JH, Hong SH, Han KD, Ha US. Association of body mass index with bladder cancer risk in men depends on abdominal obesity. World J Urol. 2019;37:2393–2400. doi: 10.1007/s00345-019-02690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jee SH, Yun JE, Park EJ, Cho ER, Park IS, Sull JW, et al. Body mass index and cancer risk in Korean men and women. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1892–1896. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JW, Ahn ST, Oh MM, Moon DG, Cheon J, Han K, et al. Increased incidence of bladder cancer with metabolically unhealthy status: analysis from the National Health Checkup database in Korea. Sci Rep. 2020;10:6476. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63595-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim SK, Jang JY, Kim DL, Rhyu YA, Lee SE, Ko SH, et al. Site-specific cancer risk in patients with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2020;35:641–651. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2017.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ko SH, Han KD, Yun JS, Chung S, Koh ES. Impact of obesity and diabetes on the incidence of kidney and bladder cancers: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181:489–498. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwon T, Jeong IG, You D, Han KS, Hong S, Hong B, et al. Obesity and prognosis in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: the continuing controversy. Int J Urol. 2014;21:1106–1112. doi: 10.1111/iju.12530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oh SW, Yoon YS, Shin SA. Effects of excess weight on cancer incidences depending on cancer sites and histologic findings among men: Korea National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4742–4754. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhaskaran K, Douglas I, Forbes H, dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Smeeth L. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5 · 24 million UK adults. Lancet. 2014;384:755–765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60892-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao Z, Zheng X, Yang H, Li S, Xu F, Yang X, et al. Association of obesity status and metabolic syndrome with site-specific cancers: a population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:1336–1344. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-1012-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goossens ME, Zeegers MP, Bazelier MT, De Bruin ML, Buntinx F, de Vries F. Risk of bladder cancer in patients with diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007470. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peila R, Rohan TE. Diabetes, glycated hemoglobin, and risk of cancer in the UK Biobank study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:1107–1119. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335:1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen HF, Chen SW, Chang YH, Li CY. Risk of malignant neoplasms of kidney and bladder in a cohort study of the diabetic population in taiwan with age, sex, and geographic area stratifications. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1494. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tseng CH. Diabetes and risk of bladder cancer: a study using the National Health Insurance database in Taiwan. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2009–2015. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2171-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lo SF, Chang SN, Muo CH, Chen SY, Liao FY, Dee SW, et al. Modest increase in risk of specific types of cancer types in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:182–188. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin CC, Chiang JH, Li CI, Liu CS, Lin WY, Hsieh TF, et al. Cancer risks among patients with type 2 diabetes: a 10-year follow-up study of a nationwide population-based cohort in Taiwan. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:381. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee HY, Tang JH, Chen YH, Wu WJ, Juan YS, Li WM, et al. The metabolic syndrome is associated with the risk of urothelial carcinoma from a health examination database. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26:569–577. doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kok VC, Zhang HW, Lin CT, Huang SC, Wu MF. Positive association between hypertension and urinary bladder cancer: epidemiologic evidence involving 79,236 propensity score-matched individuals. Ups J Med Sci. 2018;123:109–115. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2018.1473534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang WL, Huang KH, Huang CY, Pu YS, Chang HC, Chow PM. Effect of diabetes mellitus and glycemic control on the prognosis of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Urol. 2020;20:117. doi: 10.1186/s12894-020-00684-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu HL, Fang H, Xu WH, Qin GY, Yan YJ, Yao BD, et al. Cancer incidence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study in Shanghai. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:852. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1887-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu T, Zhu Z, Wang X, Xia L, Zhang X, Zhong S, et al. Impact of body mass on recurrence and progression in Chinese patients with Ta, T1 urothelial bladder cancer. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47:1135–1141. doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-1013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Otani T, Sasazuki S, Noda M, Tsugane S. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of cancer: results from a large-scale population-based cohort study in Japan. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1871–1877. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khan M, Mori M, Fujino Y, Shibata A, Sakauchi F, Washio M, et al. Site-specific cancer risk due to diabetes mellitus history: evidence from the Japan Collaborative Cohort (JACC) Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ballotari P, Vicentini M, Manicardi V, Gallo M, Chiatamone Ranieri S, Greci M, et al. Diabetes and risk of cancer incidence: results from a population-based cohort study in northern Italy. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:703. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3696-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Russo A, Autelitano M, Bisanti L. Metabolic syndrome and cancer risk. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogunleye AA, Ogston SA, Morris AD, Evans JM. A cohort study of the risk of cancer associated with type 2 diabetes. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1199–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walker JJ, Brewster DH, Colhoun HM, Fischbacher CM, Leese GP, Lindsay RS, et al. Type 2 diabetes, socioeconomic status and risk of cancer in Scotland 2001-2007. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1712–1725. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2937-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rapp K, Schroeder J, Klenk J, Stoehr S, Ulmer H, Concin H, et al. Obesity and incidence of cancer: a large cohort study of over 145,000 adults in Austria. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1062–1067. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rapp K, Schroeder J, Klenk J, Ulmer H, Concin H, Diem G, et al. Fasting blood glucose and cancer risk in a cohort of more than 140,000 adults in Austria. Diabetologia. 2006;49:945–952. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rastad H, Parsaeian M, Shirzad N, Mansournia MA, Yazdani K. Diabetes mellitus and cancer incidence: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2019;18:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s40200-019-00391-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hektoen HH, Robsahm TE, Andreassen BK, Stenehjem JS, Axcrona K, Mondul A, et al. Lifestyle associated factors and risk of urinary bladder cancer: a prospective cohort study from Norway. Cancer Med. 2020;9:4420–4432. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Evers J, Grotenhuis AJ, Aben KK, Kiemeney LA, Vrieling A. No clear associations of adult BMI and diabetes mellitus with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer recurrence and progression. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0229384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Colmers IN, Majumdar SR, Yasui Y, Bowker SL, Marra CA, Johnson JA. Detection bias and overestimation of bladder cancer risk in type 2 diabetes: a matched cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3070–3075. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jee SH, Ohrr H, Sull JW, Yun JE, Ji M, Samet JM. Fasting serum glucose level and cancer risk in Korean men and women. JAMA. 2005;293:194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roswall N, Freisling H, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ros M, Christensen J, Overvad K, et al. Anthropometric measures and bladder cancer risk: a prospective study in the EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2918–2929. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Colao A, Lenzi A, Giugliano D. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2402–2411. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trabert B, Wentzensen N, Felix AS, Yang HP, Sherman ME, Brinton LA. Metabolic syndrome and risk of endometrial cancer in the United States: a study in the SEER-medicare linked database. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:261–267. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cumberbatch MG, Jubber I, Black PC, Esperto F, Figueroa JD, Kamat AM, et al. Epidemiology of bladder cancer: a systematic review and contemporary update of risk factors in 2018. Eur Urol. 2018;74:784–795. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teleka S, Häggström C, Nagel G, Bjørge T, Manjer J, Ulmer H, et al. Risk of bladder cancer by disease severity in relation to metabolic factors and smoking: a prospective pooled cohort study of 800,000 men and women. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:3071–3082. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen SL, Jackson SL, Boyko EJ. Diabetes mellitus and urinary tract infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis and proposed studies in animal models. J Urol. 2009;182(6 Suppl):S51–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao H, Grossman HB, Spitz MR, Lerner SP, Zhang K, Wu X. Plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and binding protein-3, and their association with bladder cancer risk. J Urol. 2003;169:714–717. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000036380.10325.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.La Vecchia C, Negri E, D’Avanzo B, Savoldelli R, Franceschi S. Genital and urinary tract diseases and bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 1991;51:629–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jiang X, Castelao JE, Groshen S, Cortessis VK, Shibata DK, Conti DV, et al. Water intake and bladder cancer risk in Los Angeles County. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1649–1656. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Michaud DS. Chronic inflammation and bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brown JS, Wessells H, Chancellor MB, Howards SS, Stamm WE, Stapleton AE, et al. Urologic complications of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:177–185. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.World Health Organization Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation. 2020. [cited 2022 Feb 5]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42330. [PubMed]

- 89.Jiang X, Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Groshen S, Stern MC, Conti DV, et al. Hypertension, diuretics and antihypertensives in relation to bladder cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1964–1971. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun LM, Kuo HT, Jeng LB, Lin CL, Liang JA, Kao CH. Hypertension and subsequent genitourinary and gynecologic cancers risk: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e753. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hole DJ, Hawthorne VM, Isles CG, McGhee SM, Robertson JW, Gillis CR, et al. Incidence of and mortality from cancer in hypertensive patients. BMJ. 1993;306:609–611. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6878.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Koene RJ, Prizment AE, Blaes A, Konety SH. Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation. 2016;133:1104–1114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Radišauskas R, Kuzmickienė I, Milinavičienė E, Everatt R. Hypertension, serum lipids and cancer risk: a review of epidemiological evidence. Medicina (Kaunas) 2016;52:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Montezano AC, Touyz RM. Molecular mechanisms of hypertension--reactive oxygen species and antioxidants: a basic science update for the clinician. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Assessment of Study Quality included in the meta-analysis

Characteristics of included studies in the meta-analysis