Abstract

Active immunization with Escherichia coli-expressed recombinant outer surface protein C (OspC) of Borrelia burgdorferi has been demonstrated to confer protection against a tick-transmitted infection on laboratory animals. A previous study in this laboratory showed that OspC antibody raised against a denatured immunogen isolated from B. burgdorferi cells failed to provide protective immunity. Therefore, to determine whether the protective epitope of the recombinant antigen was sensitive to denaturation, recombinant OspC preparations were subjected to heat and chemical treatments prior to animal immunization. Following seroconversion to OspC, the animals were challenged with an infectious dose of B. burgdorferi B31 by tick bite. Whereas mice immunized with a soluble, nondenatured form continued to show protection rates close to 100%, mice that had been immunized with denatured antigen were not protected. Furthermore, mice that were immunized with an insoluble (rather than a soluble), nondenatured form of the recombinant OspC showed a protection rate of only 40%. Protective epitope localization experiments showed that either the amino or the carboxy end of the recombinant protein was required to react with a protective OspC-specific monoclonal antibody. The data from these experiments demonstrate that a conformational organization of the protein is essential for the protective capability of the strain B31 OspC immunogen.

Lyme disease, or Lyme borreliosis, is an illness causing manifestations in humans including rash, fever, and malaise; if left untreated, the infection can cause arthritis and cardiac and neurological damage (22). The disease is caused by an infection with the bacterial pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted to humans by way of the bite of infected ticks from the Ixodes ricinus complex (2). If the infection is treated early, antibiotics are effective in controlling it (23). Clinical trials of a prophylactic vaccine have recently been completed and have shown that the vaccine has promise in preventing cases of Lyme disease (20, 24). The vaccine is based upon immunization with the outer surface protein A (OspA) antigen. Its effectiveness requires the presence of neutralizing OspA antibodies in the host, which eradicate potential infecting borreliae within a feeding tick, thus preventing transmission of the organisms (3, 5).

Other B. burgdorferi proteins have been shown to elicit some protective immunity against borrelia infection in laboratory animals. Among these are OspB (4, 19), decorin binding protein A (9, 10), and OspC (17, 19). A previous study in this laboratory demonstrated that active immunization with a recombinant form of OspC protected mice against a challenge infection administered by tick bite (7). It was also observed in that study that other mice remained unprotected from the challenge infection even though they harbored OspC antibodies. The difference in this group, however, was that they had been immunized with OspC from B. burgdorferi B31 cells purified under denaturing conditions. This observation suggested that the OspC protective epitope was shaped by protein folding and secondary structure and was sensitive to denaturing conditions. This report describes results of tick bite challenges to groups of mice actively immunized with strain B31-derived recombinant OspC that had been treated by various denaturation procedures. In addition, a protective anti-OspC monoclonal antibody (MAb) was used to localize the regions of the molecule essential for the protective activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Borrelia strains and growth conditions.

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B31 (low passage number [<10 passages]) was originally provided by A. Barbour (University of California, Irvine) and maintained by the Molecular Bacteriology Section (Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases [DVBID], Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, Colo.). Borreliae were grown in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelley modified medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) supplemented with 6% rabbit serum (Pel-Freez, Rogers, Ark.) at 34°C until cell growth reached approximately 107 to 108 organisms/ml, after which the cell pellet was collected, washed, and frozen at −20°C until needed. Tick colonies of B31-infected Ixodes scapularis used for challenges were developed (16), maintained, and provided by J. Piesman (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, Colo.).

ospC gene cloning and expression.

Construction of a B. burgdorferi genomic DNA library and isolation of the ospC gene have been described elsewhere (7). Following isolation of the ospC gene, it was subcloned from the LambdaZapII vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) to the plasmid vector pBluescript II SK (Stratagene) by the in vivo excision method, according to the manufacturer’s directions.

The ospC gene was subcloned into the expression plasmid pSCREEN-1b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) by amplifying the gene by PCR from purified genomic B. burgdorferi DNA as follows. The primer pairs were OspC-F1, 5′-TCTGCTGATGAGTCTGTTAAAGG-3′, and OspC-B1, 5′-TTAAGGTTTTTTTGGACTTTCTGC-3′. These correspond to the OspC coding sequence minus the leader peptide. Primer OspC-F1 began at nucleotide 94, thus eliminating the first 31 amino acids of the mature coding sequence. Amplification was carried out by using approximately 0.5 μg of genomic DNA template at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, for 30 cycles, in a GeneAmp PCR System 9600 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.). PCR conditions were as follows: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3); 50 mM KCl; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.001% gelatin; 200 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 1 μM each primer; and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (AmpliTaq; Perkin-Elmer Cetus). The amplified product was ligated into the pSCREEN vector, according to standard procedures and the manufacturer’s directions, and transformed into Escherichia coli Novablue (DE3) (Novagen). Both pBluescript and pSCREEN constructs contained the same OspC gene sequence, but they differed in the amino terminus fusion partners derived from the respective plasmid vectors. pBluescript encodes a 37-amino-acid β-galactosidase fusion partner, and pSCREEN encodes a 38-kDa T7 gene 10 fusion partner.

Western blot and spot blot analysis.

E. coli clones containing the OspC antigen gene were grown in Luria-Bertani broth culture to late-log or stationary phase with the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside during mid-log phase. Cells were pelleted, and an aliquot was resuspended in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample loading buffer (containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and 4% SDS), boiled for 5 min, and loaded onto an 11.75% polyacrylamide gel for SDS-PAGE protein analysis. Fractionated proteins were blotted electrophoretically onto Immobilon-P (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and Western blot analyses were performed according to standard procedures (26).

For the spot blot procedure, 2 μl of lysed suspensions of B. burgdorferi cells, containing approximately 6 μg of protein, and E. coli OspC-expressing cells, containing approximately 2 μg of protein, were spotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and allowed to dry. An identical set of samples from the same suspensions was boiled for 10 min prior to being spotted on the nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked in 10% skim milk for 30 min, followed by an incubation for 1 h with a 1:20,000 dilution of a murine anti-OspC MAb (B5) at room temperature. Following three wash buffer rinses over 15 min, the blot was incubated with a goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) at 1:5,000 for 30 min. The blots were developed in 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate toluidinium (BCIP)-nitroblue tetrazolium substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry).

Antigen preparations.

Recombinant OspC antigen generated by pSCREEN (OspC-pSCREEN antigen) was prepared for mouse immunizations as follows. Following growth of the culture, the E. coli cells were harvested by centrifugation and frozen at −20°C. The cells were resuspended in 0.1 culture volume of 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 8.0)–300 mM NaCl–20 mM imidazole–10 μg of lysozyme/ml. The mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min; then the cell suspension was sonicated with a Branson (Danbury, Conn.) Sonifier 450 on ice to prevent heat denaturation. The suspension was centrifuged to pellet and separate the insoluble cellular debris from the soluble fraction. The insoluble fraction containing recombinant OspC inclusion bodies was washed 3 times in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–2 M urea–2% Triton X-100. The washed pellet was solubilized in 6 M guanidine-HCl–100 mM NaH2PO4–10 mM Tris (pH 8.0). After an incubation at room temperature for 30 min, any insoluble material left was removed by centrifugation, and the guanidine-solubilized material was collected. An aliquot of the guanidine-solubilized antigen, which carried the six-histidine (His) tag, was passed through a Qiagen (Santa Clarita, Calif.) Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid Spin Kit according to the manufacturer’s directions. The eluate contained purified recombinant OspC antigen with the guanidine-HCl buffer removed and replaced with 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 8.0)–300 mM NaCl–250 mM imidazole. Heat-denatured antigen was prepared by boiling an aliquot of the original insoluble pellet fraction for 10 min.

E. coli lysate with OspC expressed from pBluescript was sonicated as above in phosphate-buffered saline, with the soluble portion used as an immunogen. A heat-denatured antigen of this preparation was made by boiling an aliquot of the soluble lysate for 10 min.

Mouse immunizations and tick challenge.

Specific-pathogen-free outbred mice from a breeding colony of the Institute for Cancer Research (Philadelphia, Pa.) that were maintained at the DVBID were used for vaccinations. Antigen preparations were generated as described above. Approximately 50 to 100 μg of antigen was mixed with an equal volume of adjuvant (TiterMax, Norcross, Ga.), and about 50 to 100 μl was administered subcutaneously to each mouse. All mice were boosted at 2 and 4 weeks after the initial inoculation and were bled 1 week following each boost. A final boost, if needed, was administered 1 to 2 weeks prior to tick infestation. Mice were bled serially to track seroconversion of individual mice to the immunogen. Seroconversion was assessed by Western immunoblotting against B. burgdorferi B31 low-passage-number antigen with Marblot strips (MarDx Diagnostics, Inc, Carlsbad, Calif.). Once seroconversion was observed, the mice were challenged with B. burgdorferi B31 by infestation of nymphal ticks harboring the spirochete. Ten ticks were placed on each mouse and allowed to feed to repletion. Three to four days later, engorged ticks were collected and stored at 21°C under a 97% relative humidity atmosphere. An ear biopsy culture was performed on each mouse approximately 30 days after tick feeding to test for the presence of borreliae in the tissue as previously described (21). Cultures were observed microscopically for borrelia growth 1 to 2 weeks later. Cultures were deemed positive if borrelia cells were observed in any field and negative if no borrelia cells were observed in 20 fields.

Construction of truncated recombinant OspC for epitope localization studies.

Subclones containing portions of the ospC gene were constructed as follows. A BglII restriction site occurs at nucleotide position 430 and cuts the gene into two fragments of 330 and 200 bp. The two fragments were fractionated on an agarose gel and purified from the agarose with a Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit. The fragments were ligated into pBluescript at the BamHI site, in frame with the vector’s lacZ fusion product to ensure proper expression.

Additional subclones were made by unidirectional deletions, from either the 5′ or the 3′ end of the gene in pBluescript with an Erase-a-Base Kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer’s directions. DNA was religated and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene). Subsequent transformant colonies were screened and selected according to insert size, and the inserts were sequenced to determine the extent of the deletion.

Subclones were also generated by PCR. Primers used were OspC-F1 (described above), OspC-R2 (5′-AGGTTTTTTTGGACTTTCTGC-3′), OspC-117F (5′-GGGCCTAATCTTACAGAA-3′), OspC-510R (5′-AGCACCTTTAGTTTTAGTACC-3′), and OspC-590R (5′-CTCTTTAACTGAATT AGC-3′), where R indicates the reverse orientation, F indicates the forward orientation, and the number indicates the nucleotide position for the start of the primer. DNA fragments were amplified by PCR as described above, ligated into the plasmid expression vector pBAD-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), and transformed into E. coli TOP-10 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Plasmids were isolated from transformants, and inserts were DNA sequenced to confirm the correct orientation of the ligated amplicon. Growth and protein expression of individual clones were carried out as described in “ospC gene cloning and expression” above, except that gene expression was induced by the addition of 0.01% arabinose, as instructed by the manufacturer. The pBAD clones contained a short 14-amino-acid fusion partner encoded by the plasmid, and the recombinant OspC protein was produced in soluble form, like that from the pBluescript vector.

Recombinant plasmid isolation from E. coli was performed by using a QIAprep-Spin Plasmid Kit (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed with the Taq DyeDeoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.). Sequencing reactions were run and analyzed by the automated sequencing apparatus, model 373A (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). DNA sequences were computer analyzed with Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.).

RESULTS

Synthesis of recombinant OspC.

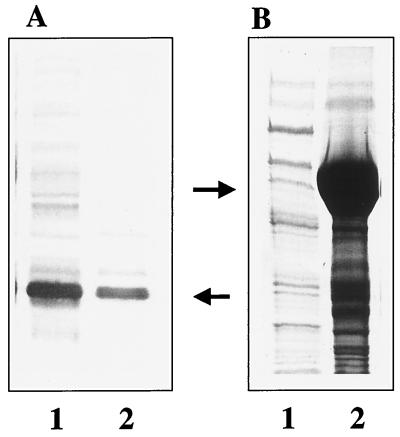

B. burgdorferi B31 recombinant OspC protein expression in this laboratory was originally generated from the pBluescript vector, as an extension from the in vivo subcloning feature of the lambda phage clone LambdaZapII. An earlier study in this laboratory used crude sonicated E. coli lysate expressing this form of recombinant OspC as the immunogen, which proved to be 100% protective against a homologous challenge (7). To improve the yield of expressed recombinant OspC, the same coding sequence was subcloned into the vector pSCREEN-1b, a pET vector derivative. Following induction of the gene in this vector, expression levels rose to account for approximately one-half of the total protein expressed by the E. coli host, thereby providing substantial material for further immunizations and subsequent studies. Unlike expression in pBluescript, where a substantial amount of the expressed OspC remained soluble (Fig. 1A), the recombinant OspC generated by the pSCREEN system accumulated almost exclusively as insoluble inclusion bodies, as seen following cell disruption and sonication (Fig. 1B). This material was used in the immunization of mouse groups following the denaturation treatments described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 1.

(A) Western blot of E. coli lysates expressing recombinant OspC in the pBluescript vector. Lanes: 1, soluble sonicated fraction; 2, insoluble sonicated fraction. Approximately 10 times less protein was loaded in lane 1 than in lane 2, indicating the predominance of the recombinant OspC in the soluble fraction. Due to the small amount of OspC protein expressed by pBluescript, the antigen is observed better by immunoblotting than by Coomassie brilliant blue staining as in panel B. (B) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel of E. coli lysates expressing recombinant OspC in the (pET) pSCREEN-1b vector. Lanes: 1, soluble sonicated fraction; 2, insoluble sonicated fraction containing recombinant OspC inclusion bodies. Arrows indicate the recombinant OspC bands.

B. burgdorferi mouse challenges by tick bite.

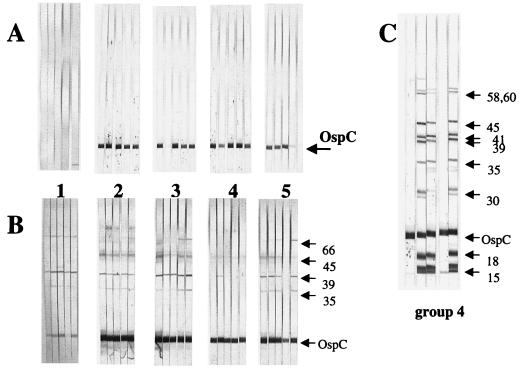

Following booster immunizations with the various immunogens, the mice were individually assayed for seroconversion to OspC by immunoblotting prior to tick challenge (Fig. 2A). Two and four weeks after tick feeding, protection from infectivity was assessed by serological profiles and culture of ear tissue, respectively. Mice immunized with OspC denatured either by heat or by guanidine treatment were not protected from infection (Fig. 2B; Table 1). Removal of guanidine by passage of OspC through a nickel cation column to purify the antigen by His tag affinity chromatography did not restore the OspC to its protective conformation, as evidenced by the lack of protection (Fig. 2B; Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Serological profiles of individual mice immunized with recombinant OspC expressed by the pSCREEN (pET) vector system as assayed by immunoblotting. (A) Mouse groups 1 to 5 prior to challenge; (B) mouse groups 1 to 5 at 2 weeks following challenge, with seroconversion, indicative of infection, beginning in most mice. Mice were immunized with E. coli lysate containing (pET) pSCREEN vector only with no insert (group 1), heat-denatured recombinant OspC (group 2), guanidine-HCl-denatured recombinant OspC (group 3), nondenatured, insoluble recombinant OspC (group 4), or recombinant OspC, denatured with guanidine, with removal of guanidine following antigen purification on a Ni2+ cation column. Sizes of antigen bands (in kilodaltons) are given on the right. (C) Serological profile of mouse group 4, at 4 weeks following challenge, with three of five mice seroconverting, indicative of infection. Sizes of antigen bands (in kilodaltons) are given on the right.

TABLE 1.

Results of infectivity assays 4 weeks postchallenge

| Immunogen | No. of mouse samples positive for infection/ no. testeda | % Protection |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli with pBluescript vector only | 5/5 | 0 |

| Recombinant OspC-pBluescript | ||

| Nondenatured | 1/16b | 93.75 |

| Heat denatured | 4/5 | 20 |

| Recombinant OspC-pSCREEN | ||

| Nondenatured (insoluble inclusions) | 3/5 | 40 |

| Heat denatured | 5/5 | 0 |

| Guanidine denatured | 5/5 | 0 |

| His tag column purified (guanidine-HCl removed) | 5/5 | 0 |

Two assays, ear biopsy culture and Western blot, were performed, with identical results.

Combined results from two studies.

However, in the mouse group immunized with OspC-pSCREEN that was not denatured, only two of five mice were protected (Fig. 2B and C). This was in contrast to previous results, whereby undenatured recombinant OspC-pBluescript protected 100% of the mice challenged (7). A second experiment was performed to assess the heat sensitivity of the protective recombinant OspC antigen generated by the pBluescript expression system. The soluble portion of a sonicated whole-cell E. coli lysate expressing OspC-pBluescript (Fig. 1B, lane 1) was inoculated into a group of five mice, and a heat-denatured aliquot of this preparation was inoculated into a second group. Four weeks after tick challenge, three of four mice (one died during the interim) receiving the undenatured OspC-pBluescript were protected, while four of five mice immunized with heat-denatured antigen became infected (Table 1).

Although anti-OspC antibody was observed by immunoblot analysis in each mouse prior to challenge at a dilution titer of at least 1:500 (Fig. 2A), the possibility existed that anti-OspC levels in unprotected mice were not at sufficient titers to elicit protection. Therefore, prechallenge antisera from protected and nonprotected mice were assayed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) against purified recombinant OspC. The OspC-ELISA titers were approximately the same whether the mice were protected or not (10−4 ± 1 10-fold dilution), and in some cases the unprotected mice had higher levels of anti-OspC. Thus, a lack of protective capability was not due to a decreased titer of OspC antibody.

Localization of the OspC protective epitope.

To identify the fragment of the recombinant OspC molecule containing the protective epitope, truncated forms were produced, expressed, and reacted by immunoblotting with an OspC MAb. This MAb was chosen to localize the protective epitope because of its demonstrated ability to passively immunize mice against a challenge infection (15). This murine anti-OspC antibody (termed B5) was one of a panel of MAbs that was generated by using B. burgdorferi-infected ticks to transmit antigen as the primary and booster inoculations (8, 14).

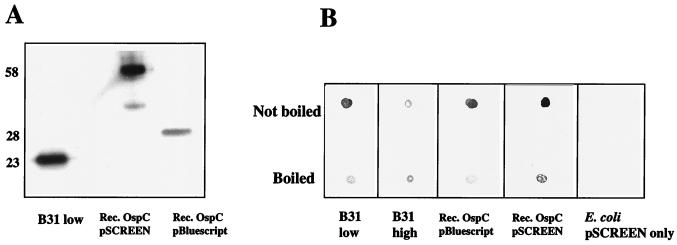

MAb B5 recognized recombinant OspC (both pBluescript and pSCREEN expressed) in Western blots (Fig. 3A), from clones consisting of the entire coding sequence minus the signal peptide. Because these antigens were denatured prior to fractionation by SDS-PAGE, a question arose as to how they were able to react with MAb B5 on Western blots. A possible explanation was that the antigens may have renatured upon transfer to the blotting membrane. To test whether heat denaturation affected immunoreactivity to the anti-OspC MAb, the OspC antigen lysates were either boiled or not boiled, spotted onto a membrane, and incubated with MAb B5. Figure 3B shows that B31 low-passage-number culture cells lose reactivity after boiling, as do both OspC recombinant lysates. This result implies that during Western transfer, the OspC antigens may refold to regain their native conformation.

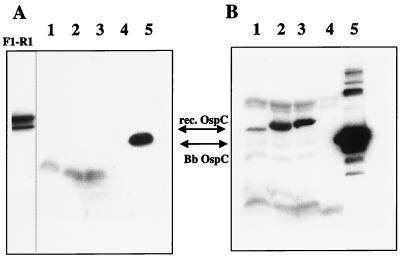

FIG. 3.

(A) Western blot demonstrating MAb B5 reactivity against B. burgdorferi B31 low-passage-number cells (B31 low) and recombinant (Rec.) OspC proteins generated in the expression vectors pBluescript and pSCREEN. The recombinant proteins are larger than the B31 OspC due to the presence of fusion partners. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) are given on the left. (B) Spot blot demonstrating MAb B5 reactivity against non-heat-denatured (“not boiled”) and heat-denatured (“boiled”) antigens. B31 high, B. burgdorferi B31 high-passage-number (>50 passages) cells, which produce small amounts of OspC; E. coli pSCREEN only, lysate of cells harboring the vector with no cloned insert. Recombinant (Rec.) OspC E. coli lysates are the same as in the Western blot in panel A.

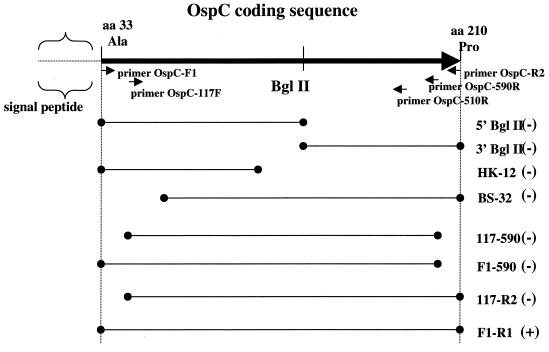

Truncated constructs with various lengths of the 5′ and/or 3′ ends of the gene deleted were generated from the OspC-pBluescript clone (Fig. 4). None of the constructs with large deletions, i.e., 5′ Bgl II, 3′ Bgl II, HK12, and BS32, were reactive with the B5 MAb. Therefore, amplicons were generated by PCR to create smaller deletions and were ligated into the vector pBAD-TOPO, which accepts PCR-derived inserts by T-A overhang cloning. Soluble OspC expression products were produced by the pBAD vector, and the full-length clone was recognized by MAb B5 (Fig. 5A). Recombinant products from clones representing the shortest deletions from either end of the gene, F1-590, 117-R2, and 117-590, demonstrated no reactivity to MAb B5 by immunoblotting (Fig. 5A). To ensure that these deletion clones were expressing a truncated OspC product, the immunoblot was stripped and reprobed with a polyclonal anti-OspC antibody, and the expressed products were detected (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 4.

Diagram showing truncated constructs of the ospC gene coding sequence. The long solid arrow at the top represents the coding sequence minus the signal peptide, beginning at amino acid (aa) 33. The dotted line at the left represents the missing signal peptide. The BglII restriction site is indicated. Arrows indicate the relative positions of the primers used to amplify and clone the constructs shown below. Lines bounded by dots represent the regions encoded by the truncated constructs, whose designations appear at the right. 5′ Bgl II and 3′ Bgl II were clones made by digestion of the gene with BglII. HK-12 and BS-32 were made by unidirectional deletions. 117-590, F1-590, 117-R2, and F1-R1 were made by PCR with the primers shown. (+) and (−), reactivity and no reactivity, respectively, with MAb B5.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of OspC expression in E. coli from truncated constructs. (A) Blot probed with the anti-OspC MAb B5. (B) The same blot stripped of antibody from panel A and reprobed with polyclonal anti-recombinant OspC derived from mice immunized with guanidine-denatured recombinant OspC. Lanes: F1-R1, pBAD construct of entire OspC coding sequence minus the leader peptide; 1, construct 117-590; 2, construct F1-590; 3, construct 117-R2; 4, pBAD vector only; 5, B. burgdorferi lysate. Arrows indicate the positions of the recombinant (rec.) OspCs (lanes 1 to 3) and the B. burgdorferi (Bb) OspC (lane 5). The recombinants are slightly larger than the native OspC due to the presence of a fusion partner from the expression vector. Construct F1-R1 expresses a doublet recombinant protein.

DISCUSSION

Recombinant forms of OspC have been demonstrated by various groups to confer protective immunity against a B. burgdorferi infection (7, 17, 19). The recombinant OspC preparations used in protection studies were purified without steps involving denaturation of the antigen. A study in this laboratory observed, however, that OspC purified from B. burgdorferi B31 cells that involved denaturation procedures did not elicit protective immunity despite high anti-OspC titers in the host (7).

To further explore this observation, this study was designed to denature recombinant OspC proven to be protective and assess its property as a protective immunogen. In our previous experiments, OspC was expressed in a soluble form by using the vector pBluescript. Because the yield of recombinant protein was low in this system, a pET vector system was alternately used to increase quantity. The fact that only two of five mice were protected by the undenatured pET vector-generated OspC conflicted with the previous observation of 100% protection by the pBluescript-generated OspC (Table 1).

The pET vector (pSCREEN)-OspC construct differed from its pBluescript counterpart in that it possessed a 38-kDa amino-terminal fusion product. The large fusion partner helped in stabilizing the expressed product, thus aiding in the synthesis of higher recombinant-protein yields. Further analysis showed that the pET vector-generated OspC was produced almost entirely as insoluble inclusion bodies aggregated within the E. coli cytoplasm. Therefore, it is probable that such an insoluble form results in folding of the protein so that the protective epitope is either physically changed or masked compared to the soluble form of the molecule. The fact that two of the mice were protected probably indicates that a minute portion of the OspC preparation was present as a soluble form, and these mice elicited a protective response against that form of the antigen. Denatured preparations of the pET-derived OspC resulted in no mice (of 15) being protected. Although this result is probably due to the antigen’s being denatured, comparisons to the control group receiving undenatured pET-derived OspC could not be unequivocal, because only 40% of the latter were protected, versus the 100% in our previous study using soluble antigen.

Therefore, another challenge was performed to assess the effects of the denaturation on the protective pBluescript-OspC antigen preparation. This expression vector produces recombinant protein in a soluble form, albeit not in the quantities seen with the pSCREEN system. However, even with the crude E. coli lysate form, 100% protection had been observed (in 12 mice tested). Five mice were immunized with the undenatured preparation, and five mice were immunized with the same preparation that was heat denatured. Four of the five mice immunized with the heat-denatured antigen were not protected, whereas three of four mice immunized with the undenatured antigen were protected (one mouse died during the trial period). Thus, the total number of mice immunized with the pBluescript-OspC in two studies from this laboratory was 16, with 15 demonstrating protection (94%) (Table 1). When the antigen was boiled, the protection rate dropped to one mouse of five (20%). The results of these experiments demonstrate that the protective epitope on the OspC molecule of B. burgdorferi B31 is conformational in nature and is affected by physical properties such as solubility, heat, and chemical denaturation.

Localization of the protective epitope on the recombinant OspC was attempted by using an OspC-specific murine MAb generated in this laboratory. The antibody was made by a method in which the mouse was immunized with tick-transmitted B. burgdorferi B31 instead of culture-grown organisms (8, 14). It was determined that this MAb, B5, when passively administered to mice, provided protection against tick-transmitted B. burgdorferi B31 infection (15). Thus, this antibody was a powerful tool in which to map or localize the OspC protective epitope.

MAb B5 was reactive in Western blots against recombinant OspC generated from all of the vector expression systems used in this study (Fig. 3A and 5A), as well as against B. burgdorferi OspC (Fig. 3A). If MAb B5 recognized a conformational epitope, then one would not expect these OspC proteins to be immunoreactive on blots with this antibody, since the preparations had been denatured by treatment with SDS, 2-mercaptoethanol, and boiling in the Laemmli SDS-PAGE system. This discrepancy may be explained by antigen renaturation following protein transfer to the blotting membrane. SDS is not present in the transfer buffer and may be washed from the gel and protein during blotting by methanol present in the transfer buffer. Partial or substantial removal of SDS may then allow refolding of the OspC to occur upon transfer to the membrane. A similar situation has been observed with disulfide bridge-associated conformational epitopes in the tick-borne encephalitis virus E glycoprotein (28). A simple experiment to support this notion was performed whereby undenatured and boiled lysates, instead of being subjected to Western blotting, were “spot” blotted onto nitrocellulose and reacted with MAb B5. Figure 3B demonstrates clearly that OspC immunoreactivity to MAb B5 was lost when the antigen was heat denatured.

MAb B5 reactivity against the recombinant OspC was abolished when only 7 amino acids were deleted from the NH2 terminus, or 13 amino acids were deleted from the COOH terminus, of the molecule. Therefore, either the ends of the molecule harbor the epitope, or more likely, the entire molecule is required for proper folding to form the epitope. There is only one cysteine in the recombinant OspC (there is a second cysteine in the OspC coding sequence, but it is located in the signal peptide, which is not present in the recombinant protein), so cysteine-cysteine disulfide linkages are not possible. A recent study by Mathiesen et al. has shown that a dominant epitope of the Borrelia garinii OspC consists of the 10 C-terminal amino acids (13). The epitope was mapped by using sera from patients with neuroborreliosis from a B. garinii infection, but it was not within the scope of that study to determine whether the antisera were protective in passive immunization experiments. Nevertheless, the C-terminal location of that epitope is somewhat consistent with that seen in this study, whereby the deletion of the B. burgdorferi OspC C terminus abolished MAb B5 reactivity. However, when the C terminus was left intact and the N terminus was deleted (construct 117-R2) (Fig. 3), antibody reactivity was also lost. Therefore, the conformationally dependent protective epitope is probably different from that seen with B. garinii-infected individuals.

It remains to be determined if OspC molecules from other strains of B. burgdorferi have conformational protective epitope properties similar to those observed for strain B31. Sequence analysis of OspCs from various strains shows regions of heterogeneity that may reflect differences in structural properties and antigenicity (11, 12, 25, 27). OspC cross-protective immunization studies are not extensive, but one study has shown that OspC antigen from strain SON188 does not cross-protect against a needle challenge with in vitro-cultured strain CA4 or 297 (18). Additionally, in a study by Bockenstedt et al., immunization with recombinant OspC derived from strain N40 (and also noted with strain 297) failed to protect mice against a tick-borne challenge infection, but recombinant OspC immunogen from strain PKo was protective (1). Those results of strain-specific immunity were attributed to differences in OspC surface expression on the borreliae, although OspC antigens for both strains were demonstrated to be localized beneath the outer membrane. Therefore, the protective capabilities of OspC antigens from different strains appear to be unique, perhaps dependent on their physical properties.

Active or passive OspC vaccines may present an alternative to the OspA-based vaccine which has recently received federal Food and Drug Administration approval. Passive immunization with polyclonal antiserum generated from recombinant OspC from B. burgdorferi ZS7 has demonstrated therapeutic capabilities against chronic infections in mice (29). These data, plus the fact that infected hosts and Lyme disease patients produce an immunodominant humoral response to OspC (6), are evidence that borreliae constitutively express OspC during the course of infection. Therefore, in studies where OspC is used either in an active immunization or to generate protective antibody for passive immunization, it becomes critical that recombinant OspC be expressed or produced in such a manner as to preserve the conformation of the protective epitope that may be particular for that strain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joe Piesman for providing ticks and the following people for their expert technical assistance: Marc Dolan for the mouse tick challenge procedure, Steve Sviat for culturing mouse tissues, and Rendi Murphree for SDS-PAGE and Western blots. We also acknowledge Tom Burkot, Nord Zeidner, Barbara Johnson, and John Roehrig for their critiques and comments regarding the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bockenstedt L K, Hodzic E, Feng S, Bourrel K W, de Silva A, Montgomery R R, Fikrig E, Radolf J D, Barthold S W. Borrelia burgdorferi strain-specific Osp C-mediated immunity in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4661–4667. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4661-4667.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgdorfer W, Barbour A G, Hayes S F, Benach J L, Grunwaldt E, Davis J P. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science. 1982;216:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.7043737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Silva A M, Telford III S R, Brunet L R, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi OspA is an arthropod-specific transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine. J Exp Med. 1996;183:271–275. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Marcantonio N, Deponte K, Kantor F S, Flavell R A. Roles of OspA, OspB, and flagellin in protective immunity to Lyme borreliosis in laboratory mice. Infect Immun. 1992;60:657–661. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.657-661.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fikrig E, Telford III S R, Barthold S W, Kantor F S, Spielman A, Flavell R A. Elimination of Borrelia burgdorferi from vector ticks feeding on OspA-immunized mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5418–5421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fung B P, McHugh G L, Leong J M, Steere A C. Humoral immune response to outer surface protein C of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease: role of the immunoglobulin M response in the serodiagnosis of early infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3213–3221. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3213-3221.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilmore R D, Jr, Kappel K J, Dolan M C, Burkot T R, Johnson B J. Outer surface protein C (OspC), but not P39, is a protective immunogen against a tick-transmitted Borrelia burgdorferi challenge: evidence for a conformational protective epitope in OspC. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2234–2239. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2234-2239.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilmore R D, Jr, Mbow M L. A monoclonal antibody generated by antigen inoculation via tick bite is reactive to the Borrelia burgdorferi Rev protein, a member of the 2.9 gene family locus. Infect Immun. 1998;66:980–986. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.980-986.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagman K E, Lahdenne P, Popova T G, Porcella S F, Akins D R, Radolf J D, Norgard M V. Decorin-binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi is encoded within a two-gene operon and is protective in the murine model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2674–2683. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2674-2683.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson M S, Cassatt D R, Guo B P, Patel N K, McCarthy M P, Dorward D W, Hook M. Active and passive immunity against Borrelia burgdorferi decorin binding protein A (DbpA) protects against infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2143–2153. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2143-2153.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jauris-Heipke S, Fuchs R, Motz M, Preac-Mursic V, Schwab E, Soutschek E, Will G, Wilske B. Genetic heterogeneity of the genes coding for the outer surface protein C (OspC) and the flagellin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1993;182:37–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00195949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livey I, Gibbs C P, Schuster R, Dorner F. Evidence for lateral transfer and recombination in OspC variation in Lyme disease Borrelia. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:257–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathiesen M J, Holm A, Christiansen M, Blom J, Hansen K, Østergaard S, Thiesen M. The dominant epitope of Borrelia garinii outer surface protein C recognized by sera from patients with neuroborreliosis has a surface-exposed conserved structural motif. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4073–4079. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4073-4079.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mbow, M. L., R. D. Gilmore, Jr., B. Stevenson, W. T. Golde, B. J. B. Johnson, and J. Piesman. Unpublished data.

- 15.Mbow, M. L., R. D. Gilmore, Jr., and R. G. Titus. An OspC-specific monoclonal antibody passively protects mice from tick-transmitted infection by Borrelia burgdorferi B31. Infect. Immun. 67:5470–5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Piesman J. Standard system for infecting ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) with the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Med Entomol. 1993;30:199–203. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/30.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Patsouris E, Jauris S, Will G, Soutschek E, Rainhardt S, Lehnert G, Klockmann U, Mehraein P. Active immunization with pC protein of Borrelia burgdorferi protects gerbils against B. burgdorferi infection. Infection. 1992;20:342–349. doi: 10.1007/BF01710681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Probert W S, Crawford M, Cadiz R B, LeFebvre R B. Immunization with outer surface protein (Osp) A, but not OspC, provides cross-protection of mice challenged with North American isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:400–405. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Probert W S, LeFebvre R B. Protection of C3H/HeN mice from challenge with Borrelia burgdorferi through active immunization with OspA, OspB, or OspC, but not with OspD or the 83-kilodalton antigen. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1920–1926. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1920-1926.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigal L H, Zahradnik J M, Lavin P, Patella S J, Bryant G, Haselby R, Hilton E, Kunkel M, Adler-Klein D, Doherty T, Evans J, Malawista S E. A vaccine consisting of recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface protein A to prevent Lyme disease. Recombinant Outer-Surface Protein A Lyme Disease Vaccine Study Consortium [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1998;339:216–222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinsky R J, Piesman J. Ear punch biopsy method for detection and isolation of Borrelia burgdorferi from rodents. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1723–1727. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.8.1723-1727.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steere A C. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:586–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908313210906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steere A C, Malawista S E, Newman J H, Spieler P N, Bartenhagen N H. Antibiotic therapy in Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:1–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steere A C, Sikand V K, Meurice F, Parenti D L, Fikrig E, Schoen R T, Nowakowski J, Schmid C H, Laukamp S, Buscarino C, Krause D S. Vaccination against Lyme disease with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface lipoprotein A with adjuvant. Lyme Disease Vaccine Study Group [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1998;339:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theisen M, Frederiksen B, Lebech A-M, Vuust J, Hansen K. Polymorphism in ospC gene of Borrelia burgdorferi and immunoreactivity of OspC protein: implications for taxonomy and for use of OspC protein as a diagnostic antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2570–2576. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2570-2576.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Jauris S, Hofmann A, Pradel I, Soutschek E, Schwab E, Will G, Wanner G. Immunological and molecular polymorphisms of OspC, an immunodominant major outer surface protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2182–2191. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2182-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winkler G, Heinz F X, Kunz C. Characterization of a disulphide bridge-stabilized antigenic domain of tick-borne encephalitis virus structural glycoprotein. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:2239–2244. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-8-2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong W, Stehle T, Museteanu C, Siebers A, Gern L, Kramer M, Wallich R, Simon M M. Therapeutic passive vaccination against chronic Lyme disease in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12533–12538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]