Abstract

Background

Several studies report the incidence of psychiatric symptoms and disorders among patients who recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); however, little is known about the emotional impact of acute COVID-19 illness and recovery on these survivors. Qualitative methods are ideal for understanding the psychological impact of a novel illness.

Objective

To describe the emotional experience of the acute COVID-19 illness and recovery in patients who contracted the virus during the early months of the pandemic.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews conducted by consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatrists were used to elicit participant responses about the emotional impact of the acute and recovery phases of the COVID-19 illness. Participants recruited from the Maryland, District of Columbia, and Virginia area were interviewed which was audio recorded between June 2020 and December 2020. The research team extracted qualitative themes from the recordings using the principles of thematic analysis.

Results

One hundred and one COVID-19 survivors (54 women; mean [SD] age, 50 [14.7] years) were interviewed at a mean of 5.16 months after their acute illness, and their responses were audio-recorded. Most participants were White (77%), non-Hispanic/Latino (86.1%), and not hospitalized for COVID-19 (87.1%). Coders identified 26 themes from participant responses. The most frequently coded themes included anxiety/worry (49), uncertainty (37), supportfrom others (35), alone/isolation (32), and positive reframe/positive emotions (32).

Conclusions

Survivors who contracted severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 during the early months of the pandemic described both negative and positive valence emotions. They experienced emotional distress and psychosocial stressors associated with the acute illness and recovery but also drew upon personal resiliency to cope. This report highlights the utility of qualitative research methods in identifying emotional responses to a novel illness that may otherwise go unnoted. Consultation-liaison psychiatrists may be uniquely positioned to work in collaboration with medical colleagues in developing a multidimensional approach to evaluating an emerging illness.

Key words: COVID-19, mental health, psychiatry, qualitative research

Introduction

As of October 2022, over 600 million people worldwide have been infected with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).1 Since the early months of the pandemic, evidence about the acute and long-term medical and mental health impacts of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has grown significantly. It is now well recognized that persistent symptoms known as long-COVID can emerge after recovery from the acute illness and give rise to psychological distress.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 In addition, large electronic health record and survey-based studies report high rates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in hospitalized and nonhospitalized COVID-19 survivors.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Furthermore, the incidence of neurological and psychiatric disorders among COVID-19 survivors is higher than that among concurrent patients with influenza or other respiratory tract infections.17 In this context, the emotional impact of acute COVID-19 illness and recovery is highly relevant.

Robust qualitative data from direct patient narratives help to better understand the impact of novel illnesses on physical health, mental health, and social functioning.18 Specifically, qualitative studies are advantageous for uncovering cognitive and emotional responses to illness experiences. For example, the grounded theory methodology has been utilized in studies that describe the lived experience of HIV/AIDS patients when it was a newly described and highly feared disease.19 Similarly, qualitative studies using the thematic analysis methodology have described the psychological distress and resilience among survivors of the more recent Ebola epidemic.20 , 21 Semi-structured interviews (SSIs) of survivors of SARS have also revealed the persistence of SARS-associated stigma.22

Qualitative approaches are ideal when the clinical landscape is unknown, as first-hand accounts of illness experience can build knowledge. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, information about the psychological impact of the illness was needed. While there is a growing literature of qualitative studies on this topic, most studies focus on COVID-19 as a public health stressor, rather than as the illness experience of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Fewer qualitative studies exist that examine the psychological experience of becoming ill with and recovering from COVID-19. A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis of articles published prior to August 2021 identified 23 studies focused on the psychological experience of COVID-19 patients. Nineteen of the 23 interviews occurred in hospital isolation wards, and 20 of the studies were conducted outside the United States. Moreover, the sample sizes of the analyzed studies ranged from 3 to 60.23 These studies have summarized a broad range of themes, including uncertainty, worry, psychological growth, persistent symptoms, shame, stigma, and acceptance.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 To date, qualitative studies on COVID-19 patient illness experiences have been limited by small sample sizes that focus primarily on hospitalized patients.23 , 29, 30, 31 This study seeks to enhance the qualitative literature by examining the emotional symptoms that accompany the acute illness and recovery of a larger and more clinically heterogeneous sample of patients who passed the acute phase of COVID-19.

To better understand the lived experiences of previously hospitalized and nonhospitalized COVID-19 survivors during the early months of the pandemic when relatively little was known about this illness, our team of consultation-liaison psychiatrists conducted semi-structured mental health interviews on participants who were enrolled in a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Intramural Research Program study (NCT04411147) investigating the long-term sequalae of SARS-CoV-2 infection.32 Borrowing from the principles of proactive C-L psychiatry, we systematically evaluated 101 research subjects without known psychiatric symptoms for emotional and mental health information related to their acute illness and recovery periods.33

Materials and Methods

This report includes a subset of study participants enrolled in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases longitudinal clinical research study of COVID-19-related medical and mental health sequelae conducted by Sneller and colleagues.32 We conducted mental health research assessments via telehealth with the first 101 consecutive COVID-19 survivors who were enrolled in the parent study. The protocol was approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants who were recruited from the Maryland, Northern Virginia, and District of Columbia area by social media advertising and study posting on ClinicalTrials.gov. Notably, this cohort of study participants were infected with SARS-CoV-2 at least 6 weeks prior to enrollment. All study visits occurred over a period of 6 months, from June to December 2020.32

The SSI was developed using the explanatory model framework described by Arthur Kleinman, a medical anthropologist who studied illness concepts and the help-seeking behavior using ethnographic interviewing techniques.34 The SSI consists of a set of questions asked by the psychiatrist/interviewer that prompts respondents to provide first-person accounts of their COVID-19 illness experiences. The SSI is divided into 3 domains that span the COVID-19 illness experience, mental health impact, and traumatic/distressing events related to COVID-19. For this analysis, we chose to focus only on the mental health impact (acute and recovery phases) of the illness and thus on participant responses to the following 2 questions from the SSI: What were your emotional reactions and responses when you were most ill with COVID-19? How has it been for you emotionally during the recovery period from COVID-19?

The SSIs were conducted by 2 psychiatrists (H.R. and J.Y.C.) at the beginning of a longer research interview that included a psychiatric diagnostic evaluation. To ensure reliability between interviews, the 2 interviewers observed one another while conducting interviews for the first 10 participants. The first 2 interviews were conducted in-person, and the remaining interviews were conducted via telehealth using an encrypted Microsoft Teams (Microsoft 365, Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA) platform to minimize in-person contact and facilitate rapport (masks removed). Consent for audio recording was obtained prior to interviews.

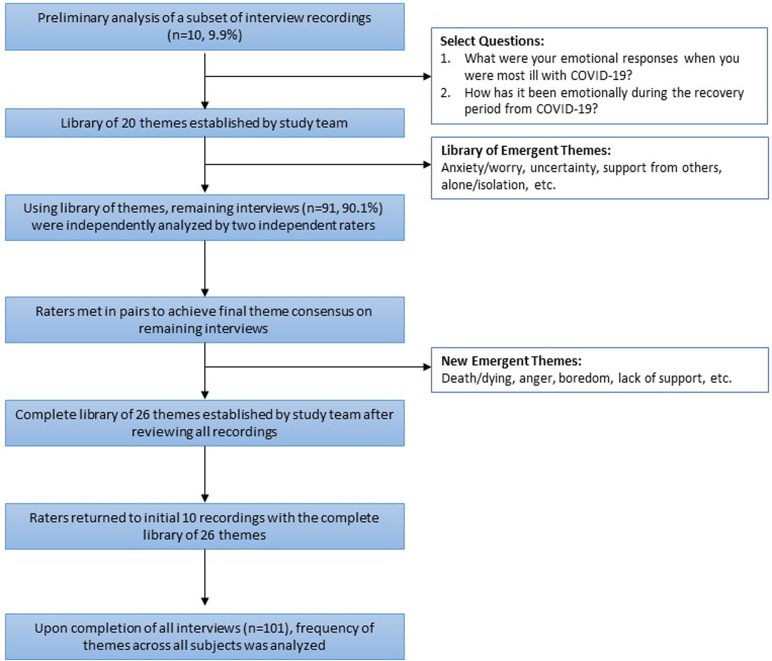

We used thematic analysis—a hypothesis-generating method—for the qualitative data collected during the SSIs.35 We applied thematic analysis by first listening and reviewing a subset of 10 consecutive interview recordings to begin the process of identifying themes that emerged from subject responses to the 2 selected questions on emotional impact. Specifically, each of 2 raters (who did not interview the subject) independently listened to the interview recordings and listed potential themes in the subjects' responses, paired with direct quotes. These 2 raters next came together and established a consensus set of common themes. Subsequently, the full study team (3 psychiatrists, 1 resident psychiatrist, and 2 research assistants) joined to review the identified themes from these initial 10 interview recordings to resolve discrepancies in thematic content between the 2 coders and to achieve further consensus. The result was a library of unique themes and their definitions (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Frequency, Definitions, and Example Quotes for Each Theme

| Themes | Theme frequency | Definitions | Example quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety/worry | 49 | Feelings of uneasiness and apprehension | “I had nervousness about the after affects. I had read about a lot of people experiencing long effects … that would become limiting in what I can do … that was the most worrisome” |

| Uncertainty | 37 | Inability to predict future circumstances | “General, always there anxiety about the uncertainty of the side effects on myself. If I get reinfected, but how will this negatively impact my health in the long term” |

| Support from others | 35 | Experiencing care and contact from family and/or friends | “Family members that I've never talked to were texting me and checking in on me.” |

| Alone/isolation | 32 | Sense of feeling cut off/removed/alienated from usual social contact | “People couldn't come see me. It was this complete isolation, like I felt I was the last person on earth.” |

| Positive reframe/positive emotions | 32 | Attempting to focus on positives and active coping | “In a twisted way, I was almost glad that I had it because there was talk of there being some protection once you have antibodies.” |

| Stress | 29 | Feeling overwhelmed or challenged by a situation | “I feel like I'm going to lose my job. I'm usually a pretty good worker” |

| Minimal distress | 27 | Lack of prominent negative experiences or emotions | “I just got sick … it didn't impact anything” |

| Persistent symptoms | 27 | Symptoms that linger or emerge after recovery from the acute COVID illness (e.g., after 1 mo) | “I couldn't go out to exercise with my kids because I would be physically drained.” |

| Fear | 24 | Distress due to perception of danger or threat | “Waking up not being able to breath … sense of impending doom … That was the scariest experience of the illness.” |

| Death/dying | 23 | Specific use of these terms or implied if not explicit | “I thought there was a chance I was not going to make it” |

| Frustration | 20 | To be annoyed because of an inability to change or do something | “How does this happen … we did everything we were supposed to do and we end up in the hospital. I saw others who were doing more and not getting it.” |

| Concern for infecting others | 19 | Specific concerns that others could become infected by them | “Was 2 wk enough? Is it safe? … I don't want anyone else to get this.” |

| Depressed | 17 | Psychological state of feeling sad, low, or unhappy | “Every time I think about that moment it make me sad.” |

| Gratitude | 17 | Thankful, acknowledgment of appreciation | “I just thank god that [I recovered] … others are sick so I just thank god” |

| Fatigue | 14 | Having no energy, feeling tired | “Is being tired an emotion or a feeling? … I was not myself for a month, energy-wise. I had to take a 2 h nap every day.” |

| Stigma | 13 | Feeling of being treated differently or judged by others | “I was scared to disclose my antibody status to my work … I feel like there's a lot of stigma around it.” |

| Burden/guilt | 13 | Feeling bad about putting additional work or responsibilities on others | “I felt guilt … I knew what an imposition it was to have my colleagues cover my shift and felt really bad about that” |

| Lack of support | 12 | Disappointment in being believed or cared for by others | “I wasn't getting any constant or correct feedback, nobody was, the world didn't know enough to care for patients.” |

| Access to COVID testing or medical care | 11 | Mention of barriers to testing or medical care | “You're not going to get a test. We don't have enough tests for people who are in the hospital, so unless you think you need to be on a machine … ” |

| Denial | 10 | Refusal or not believing in the reality of something unpleasant | “I was in denial for first couple days … Didn't want to believe that that's what it was.” |

| Hypervigilance about physical symptoms | 9 | Preoccupation with monitoring physical symptoms | “I was taking my temperature very frequently, things like that, just to see if anything was starting” |

| Prepared | 8 | Readiness to deal with situation, advanced planning | “I pushed the chairs out of the way in case we needed to call the paramedic.” |

| Anger | 5 | A strong feeling of rage, displeasure, or hostility | “Undercurrent of anger that leadership was not taking this seriously and didn't have a plan. I was angry about that all summer and into the fall.” |

| Boredom | 5 | The feeling that one's environment is dull or lacking in stimulation | “You can only text so many people on the phone, Facetime so many people …” |

| Regret | 4 | Discontentment with past decisions | “Disappointed in myself.” |

| Caring for dependent | 4 | Responsibilities to care for a dependent child or other | “It was very hard to do being sick and then … I had to be creative being home with a 5-y-old. It was a challenge.” |

Using this established library of themes, all participant recordings were analyzed separately by 2 independent raters (from a team of 6 raters) and coded. The raters met in pairs to achieve final consensus on assigned codes. Each theme was coded only once per subject if it was mentioned in the recording. If a new theme emerged, the full team met to achieve consensus and update the master library of unique themes. The iterative process of identifying themes continued as additional data were collected and analyzed until data saturation was achieved. After this, the raters returned to the initial 10 subjects and recoded these recordings to ensure that the complete list of themes was applied to these narratives.

Once all coding was completed using the final master library, the frequency of themes across all subjects was determined and reviewed by the team. Themes were further analyzed and organized into categories with team discussion (H.R., J.Y.C., G.C.M., and O.O.) and consensus. Figure 1 represents the thematic analysis methodology utilized by the team.

Figure 1.

Thematic Analysis Methodology Used by the Study Team (3 Psychiatrists, 1 Resident, 2 Research Assistants)

Results

One hundred and one COVID-19 survivors (54 female; mean [SD] age, 50 [14.7] years) were interviewed (Table 2 ). Most participants were White (77%) and non-Hispanic/Latino (86.1%). Twenty-four subjects were health care workers, and 14 were other essential workers. On average, survivors were interviewed 5.16 months (SD, 2.13) after their acute COVID-19 illness, with the acute illness occurring between February and October 2020. Thirteen COVID-19 survivors were hospitalized due to the illness, with most participants experiencing a mild to moderate acute illness that did not require hospitalization.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total, no. (N = 101) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50 (14.7) |

| Female | 54 |

| Race | |

| White | 78 |

| Black/African American | 13 |

| Asian | 5 |

| Multiple race | 2 |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 |

| Type of work | |

| Health care worker∗ | 24 |

| Other essential workers† | 14 |

| Other employment‡ | 58 |

| Student | 4 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Hospitalized | 13 |

| Months between COVID-19 dx and SSI, mean (SD) | 5.16 (2.13) |

SSI = semi-structured interview.

Health care worker includes physicians, nurses, physician assistants, and so on.

Other essential workers include non–health care workers who were required to continue to work during the early phases of the pandemic, such as individuals working in education, trade workers, and so on.

Other employment includes professions in law, business, engineering, arts, government, and so on.

Themes

The coded portions of the interviews regarding emotional experiences of COVID-19 ranged from less than 1 minute to 14 minutes, with an average coded portion of 4 minutes and 35 seconds. Using the thematic analysis methodology, coders identified 20 themes on the initial 10 subjects' interviews. Six additional themes emerged as subsequent interview recordings were analyzed, yielding a total of 26 unique themes, provided in Table 1 with definitions and illustrative quotations. On average, participant interview responses yielded 5 themes each, with the number of themes endorsed ranging between 1 and 12 per participant.

It is important to note that 1 response could give rise to multiple themes. For example, the remark “In a twisted way, I was almost glad that I had it because there was talk of there being some protection once you have antibodies” was marked as both positive reframe about COVID and gratitude. Alternatively, the quote “I started to get really afraid that I was never going to get rid of this fever, I was never going to get rid of this disease, and that maybe I wasn't going survive” was coded as anxiety/worry, fear, uncertainty, and death/dying. Notably, while we discovered a number of “emotional themes,” additional personal themes emerged that were not related to feelings per se, but rather to interpersonal, environment, and somatic topics.

Emotional Distress

Several major categories of themes emerged from the data. At the forefront, emotional distress was experienced by many survivors. While anxiety (n = 49) was the most common theme, survivors also described uncertainty (n = 37), feeling stressed (n = 29), and experiencing fear about the illness or symptoms they experienced while ill (n = 24). More than a fifth of patients (n = 23) mentioned distressing thoughts of death or dying in relation to their COVID-19 illness experience. Many survivors (n = 17) experienced depressed mood during their illness. Feelings of isolation and being alone were prominent themes (n = 32). Feelings of being a burden on others with associated guilt were also distressing (n = 13). At lesser rates, survivors expressed feelings of denial of their diagnosis (n = 10), frustration (n = 20), and anger (n = 5).

“The fear was intense, everything was at a level 10, they kept telling me don’t worry—that the ventilator was behind me; I called my family and I told them I loved them because I didn’t know if I was going to die in there by myself; I could see the commotion when other man on the ward started struggling, all these doctors and nurses came rushing in … they put that tube down his throat and put him on the ventilator … he was in a coma, but I don’t know if he made it out and that made me feel guilty.”

Interpersonal and Environmental Stressors

Survivors also endorsed concerns related to the psychosocial stressors of their illness experience and subsequent period of recovery. These included experiences with lack of support from others (n = 12) and boredom (n = 5), often related to the period of being in isolation. Some described significant stress related to having to care for dependents (n = 4) while they were ill. Parents of young children and adults caring for elderly parents, in particular, faced this additional hardship during their acute illness and recovery period. Access to medical care (n = 11) including being able to obtain timely diagnostic testing, getting an appointment to see a health care provider, or receiving medical guidance was problematic for some survivors. Some survivors spoke of negative interactions with physicians in various health care settings, including having their symptoms minimized and being told they did not meet the criteria for testing despite subsequent positive results when a test was administered. Some spoke of feelings of being abandoned by their health care providers due to their symptoms or COVID-19 diagnosis due to concerns of care provider or office/clinic staff about contagion and infection control. This experience led to some feeling stigmatized. Over 10% of participants (n = 13) experienced stigma from others due to their COVID status, even weeks after recovery in some cases.

“At one point I went to the ER when I had COVID … the staff at the ER would not let me go to the restroom here … they said you can’t use this bathroom, you just have to hold it … I can give you a pan. I felt like I was being treated like we were in 80s and it was the AIDS pandemic. Like I was a second-class citizen, so that on top of my PCP not believing me with my blood pressure and [she] said ‘well I haven’t heard of any survivor who has high blood pressure as a result’. When I talk about the pain or what I am going through … at one point [she] suggested I see someone, because maybe I was making it up. And that was just very hurtful.”

Persistent Symptoms of COVID-19 Infections

Almost 30% of survivors (n = 27) reported ongoing problems and distress related to persistent symptoms within days and weeks of their acute illness or even months later. Fatigue (n = 14) was commonly endorsed. Survivors also reported hypervigilance about their symptoms and health during the acute illness and recovery period (n = 9), some recalling particularly distressing experiences.

“I ended up going to the ER twice and I hadn’t wanted to go because I didn’t think it was serious enough … both times I went it was because my heart rate was very high and we had watched it carefully … if it hit a certain number again, I would go to the ER. I was checking my vitals multiple times especially when I had fevers and I would watch it carefully throughout the day. I also remember I went through a few weeks where I thought I was misusing the thermometer because it didn’t seem possible that I could be running fever for a whole month.”

Positive Coping

Notably, survivors endorsed many themes with a positive valence. Thirty percent of survivors (n = 32) were able to reframe their thoughts in a positive and adaptive way, both while experiencing the acute illness and during the recovery. For example, some reported feeling relief about having had the illness and recovering, noting hopes that they would develop immunity and potentially be able to help others. Many experienced minimal distress (n = 27) during their experience with the illness both in terms of symptoms of illness and/or emotional problems. Others expressed gratitude (n = 17) about their recovery and support they received from others (n = 35). Some felt empowered by being prepared to manage things during their illness (n = 8), noting access to supplies, medications, and groceries.

“When we first started feeling better I felt like a superhero … we're feeling better, we've made it through, we can donate plasma, we can help other people.”

Discussion

This qualitative data analysis describes the first-hand experiences of a cohort of 101 COVID-19 survivors who became ill during the early phase of the pandemic. As a part of a larger longitudinal study of the sequelae of COVID-19, each study subject participated in a SSI performed by psychiatrists. While the interview asked about their emotional reactions during their acute illness and recovery periods, many subjects shared topics that extended beyond affective experiences but were associated with them. To our knowledge, this is the first study to highlight the psychological aspects of the COVID-19 illness experience in a sample of this size utilizing a SSI. The qualitative study approach was ideal in facilitating an in-depth investigation into the lived experiences of individuals who had recovered from the acute phase of the COVID-19 infection. Through careful analysis of the personal accounts of 101 survivors, reliable knowledge about the illness experience was built.

Several themes central to the COVID illness experience emerged from the data. First, despite variability in acute illness severity (mild to severe), survivors reported intense emotional distress during their illness experience. Specifically, anxiety/worry was the most frequently coded theme, with nearly half of the sample mentioning this type of emotional distress. Feelings of anxiety were also highly endorsed by COVID-19 patients in similar qualitative studies in Iran and South Korea.27 , 36 Uncertainty, the second-most commonly coded theme in our study, was also a prominent concept in a qualitative study on a COVID-19 recovery cohort of 24 subjects by Santiago-Rodriguez and colleagues.24 Relatedly, in our study, individuals reported hypervigilance about their symptoms and not knowing exactly how to interpret their seriousness or significance. The experiences of persistent symptoms and ongoing fatigue were burdensome even months after the acute illness in our patient sample, with their accounts predating the recognition of “long-COVID” syndrome. Many reports of uncertainty revolved around these persistent symptoms, similar to the findings in the study by Santiago-Rodriguez and colleagues.24 In their findings, many of the themes of psychological distress were highly endorsed by survivors experiencing persistent symptoms, providing more context to the subjective experience of long-COVID.24

For many, the impact of isolation, feeling stigmatized, and having problems accessing medical care were difficult and may have contributed to emotional hardship.37 Notably, while the experience was difficult, many survivors in our sample showed resiliency and were able to use a positive framework when coping with their illness. Some indeed noted minimal distress throughout the experience, whereas others experienced significant emotional struggles yet were able to use adaptive strategies including optimism and gratitude. Overall, these findings are consistent with those of the other qualitative studies on the illness and recovery experiences of COVID-19 survivors cited in this article, highlighting the heterogenous and complex psychological course of COVID-19 patients during the acute phase of the illness and recovery.

As the pandemic continues and reports of the ongoing and uncertain effects of postacute sequelae of COVID-19 are published, our findings have implications for management and treatment of affected patients and survivors. Health care providers should be aware of the emotional functioning of individuals and anticipate they may experience worry and fear related to the uncertainty of having a novel illness and implications for future well-being. Health care providers, in addition to providing medical advice, should have strategies in place to offer additional support, education, and information and plans to ensure access to care and communication when necessary. Public health efforts should ensure provision of clear, timely, and widespread communication about the disease, treatment, and additional resources for support and education. Measures of emotional well-being will reduce uncertainty and support ongoing recovery in individuals affected by COVID-19 illness.

Furthermore, our study highlights the importance of proactively assessing mental health and emotional experiences that may otherwise go unnoted or not warrant a psychiatry consultation during the course of a novel illness. At the outset of the pandemic, as C-L psychiatrists working in a medical research hospital, we were able to rapidly pivot and begin studying the evolution of a pandemic using an interdisciplinary approach with our medical colleagues. Rather than proceeding with a “reactive” approach of evaluating only those patients who were flagged “for cause” consults by the medical team, we used the opportunity of research study involvement to take a “proactive” approach.33 We were thereby able to capture the range of emotional and mental health experiences of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection soon after its emergence in the United States.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, a majority of our sample identifies as White and not Hispanic or Latinx. Future studies should investigate the experiences of a broader sample that better reflects the larger US population, including underrepresented groups that are affected with COVID-19 at greater rates and experience more disease burden. Our sample represents COVID survivors who became ill in the earlier waves of the pandemic (February 2020-October 2020), prior to vaccine and therapeutics availability and during a period when far less was known about the COVID-19 illness and long-term impacts. Subsequent studies of survivors may share a different experience of the virus given the variability in illness presentation as new variants emerge, access to vaccination, availability of advanced therapeutics, evolving knowledge about the illness, and declines in case prevalence and severity. In addition, our subjects were well connected to a medical research study team and may share a different experience from those with limited access to comprehensive medical evaluation and care. Future investigations could further explore risk and resiliency factors shaping the emotional experience of the COVID-19 illness to better inform treatment, management, and public health intervention. Furthermore, while we have highlighted thematic analysis data from responses to 2 specific questions from the SSI on the mental health impact of COVID-19, we also hope to examine other facets of the illness experience shared by survivors during the SSI. It is possible that more themes would arise from analysis of the entire SSI rather than the 2 questions that specifically focused on the emotional experiences of the acute and recovery phase.

A particular strength of our study includes the relatively larger sample size of COVID-19 survivors, compared to prior studies. A systematic review of qualitative studies published prior to August 2021 included studies that analyzed samples of 3–60 survivors, with a majority of studies having sample sizes between 10 and 20.23 Through the process of conducting 101 patient interviews, we were able to identify similar patterns of both negative (emotional distress and uncertainty) and positive aspects (resiliency and adaptive coping) of the illness experience despite the relative variability in illness experiences. The utilization of reliably trained psychiatrists who are skilled in eliciting sensitive information surrounding illness is another strength. Moreover, our findings are notable in that we assessed the experiences of a cohort of survivors with disease severity that more closely mirrors that of the general population, with most individuals experiencing mild illness, not requiring hospitalization. Qualitative studies are an important research methodology to draw knowledge about novel illnesses through first-hand accounts from affected individuals.

Conclusions

Early survivors of COVID-19 infection describe a breadth of illness-related emotional and personal experiences. Survivors drew upon positive coping mechanisms and personal resilience. However, many endured significant emotional distress, most notably anxiety, associated with the acute illness and recovery period, highlighting the need to identify and support the potential mental health repercussions of COVID-19. Given their work in medical settings, C-L psychiatrists have the unique opportunity to rapidly collaborate with medical colleagues in other specialties to build knowledge about psychiatric manifestations of new and lesser understood illnesses.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bryan Higgins, Cassie Seamon, and Katie Tolstenko from the NIAID study team for administrative support. We would like to thank Maryland Pao from NIMH for supporting this research study.

Footnotes

Ethical Publication Statement: The work described in this article has not been published previously and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. The publication of the work is approved by all authors and by all responsible authorities at the National Institutes of Health. All authors contributed substantially to this research study. If it accepted, this manuscript will not be published elsewhere in the same form.

Funding: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health (annual report number ZIAMH002922) and the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and in part by federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (contract no. 75N91019D00024).

Disclosure: The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Disclaimer: The content of this article does not reflect the view and/or policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services nor the U.S. government.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard 2022. 2022. https://covid19.who.int Available from: https://covid19.who.int.

- 2.Menges D., Ballouz T., Anagnostopoulos A., et al. Burden of post-COVID-19 syndrome and implications for healthcare service planning: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor R.R., Trivedi B., Patel N., et al. Post-COVID symptoms reported at asynchronous virtual review and stratified follow-up after COVID-19 pneumonia. Clin Med. 2021;21:e384–e391. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2021-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C., Haupert S.R., Zimmermann L., Shi X., Fritsche L.G., Mukherjee B. Global prevalence of post COVID-19 condition or long COVID: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1593–1607. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugiyama A., Miwata K., Kitahara Y., et al. Long COVID occurrence in COVID-19 survivors. Sci Rep. 2022;12:6039. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-10051-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group Four-month clinical status of a cohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325:1525–1534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RECOVER: Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery. https://recovercovid.org Available from:

- 8.Xie Y., Xu E., Al-Aly Z. Risks of mental health outcomes in people with covid-19: cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang L., Xu X., Zhang L., et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and quality of life of COVID-19 survivors at 6-month follow-up: a cross-sectional observational study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;12:782478. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.782478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyzar E.J., Purpura L.J., Shah J., Cantos A., Nordvig A.S., Yin M.T. Anxiety, depression, insomnia, and trauma-related symptoms following COVID-19 infection at long-term follow-up. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;16:100315. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clift A.K., Ranger T.A., Patone M., et al. Neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 and other severe acute respiratory infections. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:690–698. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourmistrova N.W., Solomon T., Braude P., Strawbridge R., Carter B. Long-term effects of COVID-19 on mental health: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., et al. 6-Month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen H.C., Nguyen M.H., Do B.N., et al. People with suspected COVID-19 symptoms were more likely depressed and had lower health-related quality of life: the potential benefit of health literacy. J Clin Med. 2020;9:965. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J., Lu H., Zeng H., et al. The differential psychological distress of populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:49–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ismael F., Bizario J.C.S., Battagin T., et al. Post-infection depressive, anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms: a prospective cohort study in patients with mild COVID-19. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;111:110341. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taquet M., Geddes J.R., Husain M., Luciano S., Harrison P.J. 6-Month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vindrola-Padros C., Chisnall G., Cooper S., et al. Carrying out rapid qualitative research during a pandemic: emerging lessons from COVID-19. Qual Health Res. 2020;30:2192–2204. doi: 10.1177/1049732320951526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaskins S., Brown K. Psychosocial responses among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Appl Nurs Res. 1992;5:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(05)80025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwerdtle P.M., Clerck V.D., Plummer V. Experiences of Ebola survivors: causes of distress and sources of resilience. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2017;32:234–239. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X17000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabelo I., Lee V., Fallah M.P., et al. Psychological distress among Ebola survivors discharged from an Ebola treatment unit in Monrovia, Liberia – a qualitative study. Front Public Health. 2016;4:142. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siu J.Y.-M. The SARS-associated stigma of SARS victims in the post-SARS era of Hong Kong. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:729–738. doi: 10.1177/1049732308318372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H., Xie F., Yang B., Zhao F., Wang C., Chen X. Psychological experience of COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:809–819. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2022.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santiago-Rodriguez E.I., Maiorana A., Peluso M.J., et al. Characterizing the COVID-19 illness experience to inform the study of post-acute sequelae and recovery. IntJ Behav Med. 2022;29:610–623. doi: 10.1007/s12529-021-10045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moradi Y., Mollazadeh F., Karimi P., Hosseingholipour K., Baghaei R. Psychological disturbances of survivors throughout COVID-19 crisis: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:594. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-03009-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prioleau T. Learning from the experiences of COVID-19 survivors: web-based survey study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5 doi: 10.2196/23009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Son H.M., Choi W.H., Hwang Y.H., Yang H.R. The lived experiences of COVID-19 patients in South Korea: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7419. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts M.E., Knestrick J., Resick L. The lived experience of COVID-19. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17:828–832. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muslu L., Kolutek R., Fidan G. Experiences of COVID-19 survivors: a qualitative study based on Watson’s Theory of Human Caring. Nurs Health Sci. 2022;24:774–784. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo M., Kong M., Shi W., Wang M., Yang H. Listening to COVID-19 survivors: what they need after early discharge from hospital - a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2022;17:2030001. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2022.2030001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu D., Ding H., Lin J., et al. Fighting COVID-19: a qualitative study into the lives of intensive care unit survivors in Wuhan, China. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sneller M.C., Liang C.J., Marques A.R., et al. A longitudinal study of COVID-19 sequelae and immunity: baseline findings. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:969–979. doi: 10.7326/M21-4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oldham M.A., Desan P.H., Lee H.B., et al. Proactive consultation-liaison psychiatry: American Psychiatric Association resource document. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2021;62:169–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleinman A. University of California Press; Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: 1980. Patients and healers in the context of culture: an exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toulabi T., Pour F.J., Veiskramian A., Heydari H. Exploring COVID-19 patients’ experiences of psychological distress during the disease course: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:625. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03626-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernández R.S., Crivelli L., Guimet N.M., Allegri R.F., Pedreira M.E. Psychological distress associated with COVID-19 quarantine: latent profile analysis, outcome prediction and mediation analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]