Abstract

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer. Here, using whole genome, exome and transcriptome sequencing of 2,754 childhood ALL patients, we find that despite a generally low mutation burden, ALL cases harbor a median of 4 putative somatic driver alterations per sample, with 376 putative driver genes identified varying in prevalence across ALL subtypes. Most samples harbor at least one rare gene alteration, including 70 putative cancer driver genes associated with ubiquitination, SUMOylation, non-coding transcripts and other functions. In hyperdiploid B-ALL, chromosomal gains are acquired early and synchronously, prior to ultraviolet-induced mutation. By contrast, ultraviolet-induced mutations precede copy gains in B-ALL cases with intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21). We also demonstrate prognostic significance of genetic alterations within subtypes. Intriguingly, DUX4- and KMT2A-rearranged subtypes separate into CEBPA/FLT3- or NFATC4-expressing subgroups with potential clinical implications. Together, these results deepen understanding of the ALL genomic landscape and associated outcomes.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) arises from B- or T-lineage lymphoid progenitors and is the most common childhood cancer, and is comprised of over 30 genetically distinct subtypes of prognostic importance1,2. Previous studies have identified subtypes and secondary mutations that influence risk stratification and prognosis (e.g. IKZF1 alterations3,4, Ph-like ALL5,6, DUX47,8, MEF2D9, ZNF384-rearranged ALL10,11, PAX5 P80R12,13 and PAX5alt14,15 ALL)16,17. Many of these studies have examined small cohorts, lacked genome-wide analysis, or have had limited integration of RNA and DNA sequencing. Here we performed an integrated multiplatform genomic analysis of 2,754 cases of pediatric ALL to identify new putative cancer driver genes, and to define the spectrum, co-occurrence, clonality, sequence of acquisition and prognostic importance of germline and somatic genetic alterations across the landscape of B- and T-ALL.

Results

Patient cohort and genomic sequencing

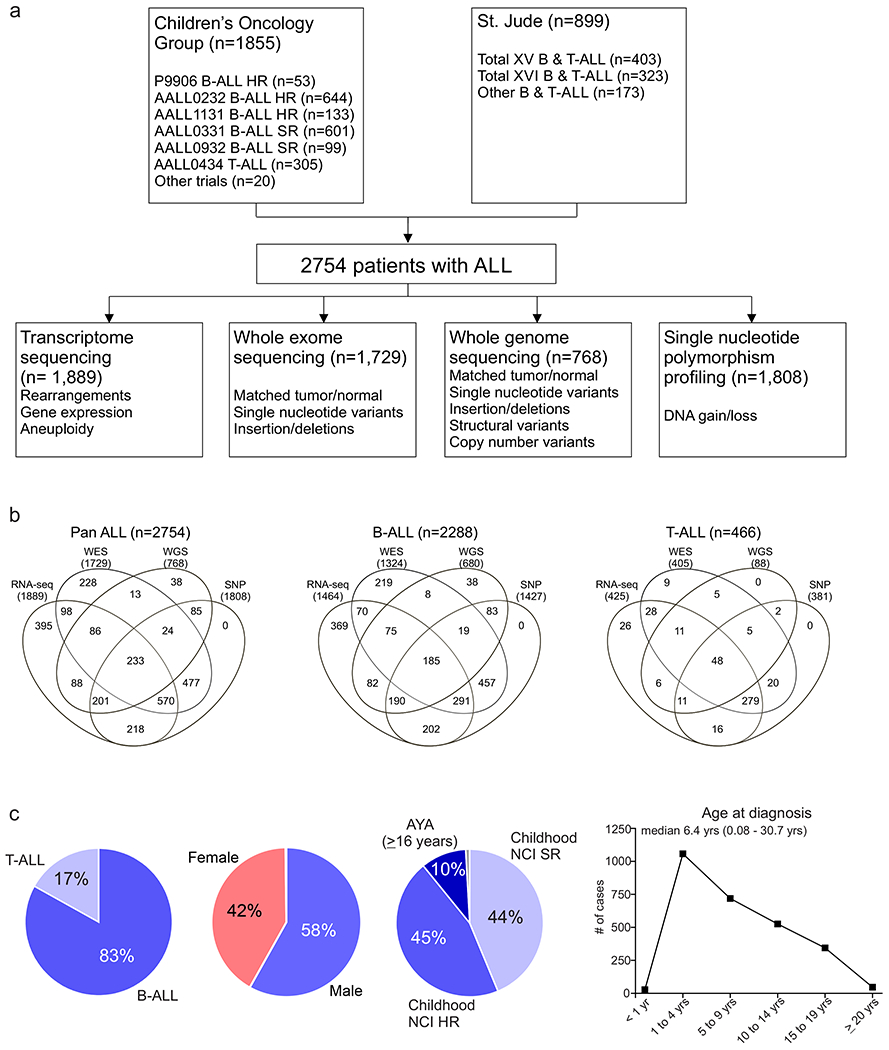

We studied 2,754 children, adolescents and young adults (AYA) with newly diagnosed B-ALL (n=2,288 cases) or T-ALL (n=466) (Supplementary table 1 and Extended data fig. 1). Median age at diagnosis was 6.4 years (range 0.08 – 30.7), with 58.2% male and 41.8% female (Supplementary table 2). The cohort comprised 1,209 childhood National Cancer Institute (NCI) standard-risk (SR, 43.9%; age range 1-9.99 years, white blood cell count (WBC) ≤ 50,000/μl), 1,252 childhood NCI high-risk (HR, 45.5%; age range ≥10 to 15.99 years and/or WBC > 50,000/μl) and 275 AYA patients (10.0%; age range 16-30.7 years). Genomic analyses were performed using paired tumor and normal samples derived from bone marrow or peripheral blood obtained at leukemia remission for whole exome sequencing (WES; n=1,729), whole genome sequencing (WGS; n=768), and single nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP; n=1,808). Tumor-only whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on 1,889 patients (Extended data fig. 1).

Mutation burden differs across ALL molecular subtypes

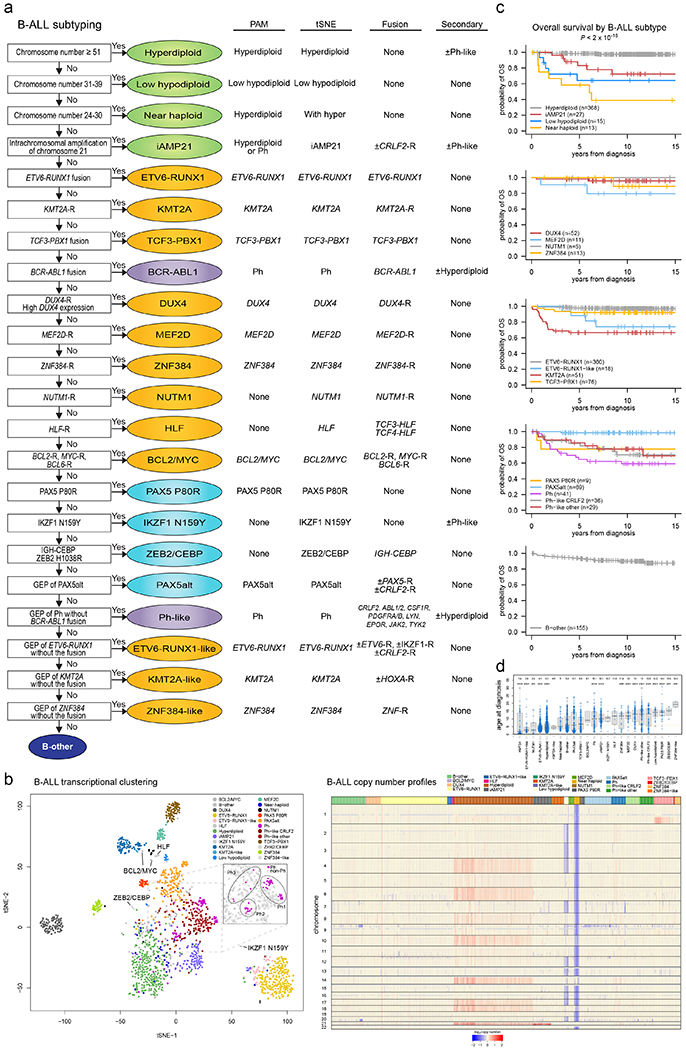

B-ALL cases were classified into 24 different molecular groups18 and T-ALL into 10 groups17,19, with significant differences in genomic subtype between T-ALL and early T cell precursor (ETP) ALL (Fig. 1a, Extended data Fig. 2–3 and Supplementary table 2). In cases with WES and/or WGS (n=2141; Extended data Fig. 4a), we identified 24,199 somatic nonsynonymous single-nucleotide variants (SNVs; median 9 nonsynonymous SNVs per sample, range 0-269) and 3,314 somatic coding-region insertion/deletion mutations (indels; median 1 indel per sample, range 0-34) in 10,404 genes (median 10 genes per sample, range 0-252; Supplementary table 3). In cases with WGS, we identified 15,715 somatic structural variants (SVs) genome wide (median 15 SVs per sample, range 0-115; Supplementary table 4) and in cases with RNA-seq and/or WGS (n=2,049) we identified 1,301 somatic putative driver gene rearrangements (Supplementary table 5).

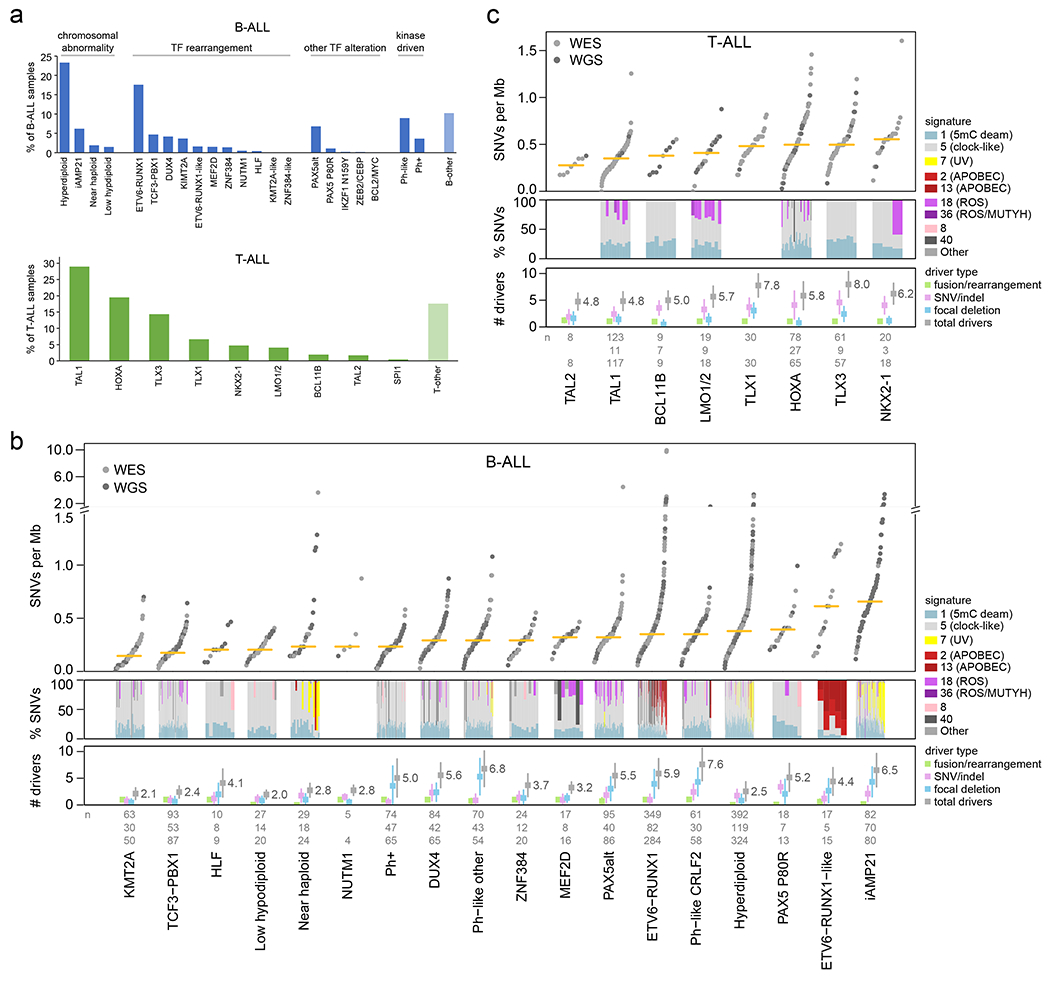

Figure 1. ALL cohort, mutational burden, and mutational signatures.

(a) Bar graphs showing the percentage of analyzed samples belonging to each B-ALL (top) or T-ALL (bottom) subtype. (b) Top, mutational burden in each B-ALL subtype with at least 5 samples. This shows the number of somatic SNVs per megabase (Mb) in each sample (points) sequenced by WES (gray) or WGS (dark gray), with the median indicated by a yellow bar. Beneath this, mutational signatures are shown for each WGS sample in subtypes with at least 3 WGS samples. Signatures are shown as the percentage of SNVs caused by each signature (y-axis), as indicated by colors in the legend at right. Samples in each subtype are sorted by increasing mutation burden from left (low burden) to right (high burden). Bottom shows the number of somatic driver or putative driver alterations per sample, with center indicating mean and whiskers indicating standard deviation. Known/putative driver alterations, detected by WGS, WES, or RNA-seq, are separated into fusions/rearrangements (such as driver fusions and enhancer hijacking events), coding SNVs or indels in putative driver genes, and focal deletions in putative driver genes (tumor suppressors). The sum of all putative driver alterations is also shown (total drivers). If the same gene was affected twice by SNVs, indels, or focal deletions in one sample, it was counted as one alteration. The n values at bottom indicate the number of samples analyzed per subtype for mutation burden (top, samples with WGS or WES), mutational signatures (middle, WGS), or putative driver burden (bottom, WGS or WES plus SNP copy array). (c) As in (b), except for T-ALL.

Overall, the median somatic mutation rate in ALL was 0.35 SNVs per megabase (Mb), which in B-ALL ranged from 0.15 in the KMT2A-rearranged subtype to 0.66 in iAMP21 (Fig. 1b), and in T-ALL from 0.28 in TAL2 to 0.55 in NKX2-1 (Fig. 1c). Overall, 376 putative driver genes were identified using the mutation-significance detection tools MutSigCV (SNVs and indels)20, GRIN (SNVs, indels and copy number alterations (CNAs); Supplementary table 6)21, GISTIC (CNAs)22 and Medal Ceremony23; 70 of which were not previously reported in ALL (Extended data fig. 4b, Supplementary table 6). Of these 70 putative drivers, 43 have been reported in other solid or hematological tumors but not ALL, and 27 had not been previously reported as targets of somatic alteration in human malignancies24,25. The median number of somatic putative driver gene alterations identified per case (including SNVs, indels, focal deletions, and fusions/rearrangements) was 4 (range 0-19) (Fig. 1b, c), similar to the number identified in adult cancers26. Putative driver CNAs (focal deletions) were more prevalent in B-ALL (median 2 (range 0-18) for B-ALL vs. 1 (0-6) for T-ALL, P=8.98x10−18 by two-sided t-test), whilst putative driver SNVs/indels were more frequent in T-ALL (1 (0-8) for B-ALL vs. 3 (0-11) for T-ALL, P=4.82x10−54). In B-ALL, the number of putative driver alterations per case was the highest in Ph-like-CRLF2, Ph-like-other, and iAMP21 subtypes (mean 7.6, 6.8, and 6.5 alterations) and lowest in low hypodiploid and KMT2A-rearranged ALL (2.0 and 2.1; Fig. 1b). In T-ALL, the TLX3 and TLX1 deregulated subtypes had the highest putative driver burdens (8.0 and 7.8) while TAL1 and TAL2 had the lowest (4.8; Fig. 1c). In B-ALL, only 2.2% of samples had no detected putative driver gene alterations (most in hyperdiploid B-ALL). A putative driver gene alteration was detected in every T-ALL sample.

Contrasting patterns of mutational signatures in ALL

Mutational signatures were compared across ALL subtypes using WGS (Fig. 1b, c and Supplementary tables 7–8)27. COSMIC signatures 1 and 5 (clock-like cell-intrinsic processes)28 were present in almost all samples (100% and 98%, respectively) and these signatures’ mutation burden positively correlated with age in more than half of the subtypes (Extended data fig. 5a, b). Signatures 2 and 13 (APOBEC) were enriched in ETV6-RUNX1 and ETV6-RUNX1-like B-ALL (detected in 43% and 100% of samples, respectively; Fig. 1b)24. Signature 7 (UV) was enriched in cases with gross chromosomal alterations, including hyperdiploid (detected in 17% of samples), near haploid (35%) and iAMP21 B-ALL (46%; Fig. 1b). Unexpectedly, we observed enrichment of signature 18 (ROS) in several subtypes including Ph-like-CRLF2 (detected in 21% of samples), Ph-like-other (11%), and PAX5alt (41%) B-ALL, and TAL1 (36%) and LMO1/2 (67%) in T-ALL (Fig. 1b, c). The APOBEC and UV signatures did not increase with age, consistent with episodic29 or environmental mutagenesis (Extended data fig. 5c, d). By contrast, the ROS signature increased with age in several subtypes, suggesting a constant cell-intrinsic process (or alternatively, a sustained environmental exposure), and was associated with 20q and 9p deletions in Ph-like-CRLF2 (P = 1.5 x 10−5 and P = 5.1 x 10−5, respectively, by Fisher’s exact test) Ph-like-other (P = 8.5 x 10−4 and P = 8.5 x 10−4), and PAX5alt (P = 0.013 and P = 0.048; Extended data fig. 5e, right).

Evolution of mutations and aneuploidy in B-ALL

Hyperdiploid ALL is the most common subtype of childhood leukemia, but the timing of acquisition of the aneuploidies and sequence mutations is unknown. We used regions with triploid chromosomes as a molecular clock to assess whether UV-induced SNVs preceded the copy number gain (present on 2 of 3 or 1 of 3 chromosomal copies), or occurred after the gain (present exclusively on 1 of 3 chromosomal copies; Fig. 2a). UV-induced SNVs were found on only 1 of 3 triploid chromosomes (variant allele frequency (VAF) ≈ 0.33; Fig. 2b) in hyperdiploid B-ALL24, consistent with copy gains occurring early, potentially in utero30, as they preceded UV exposure.

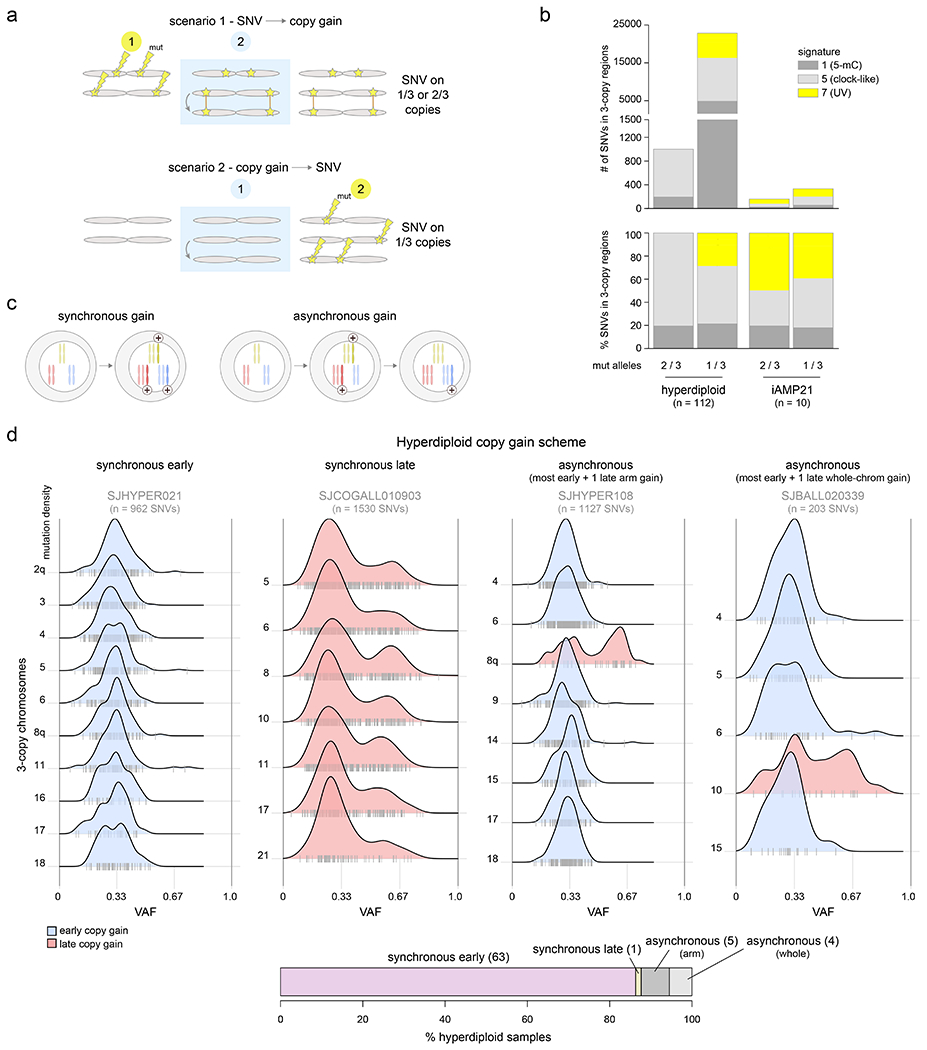

Figure 2. Temporal evolution of ultraviolet-associated mutations and copy gains in aneuploid B-ALL subtypes.

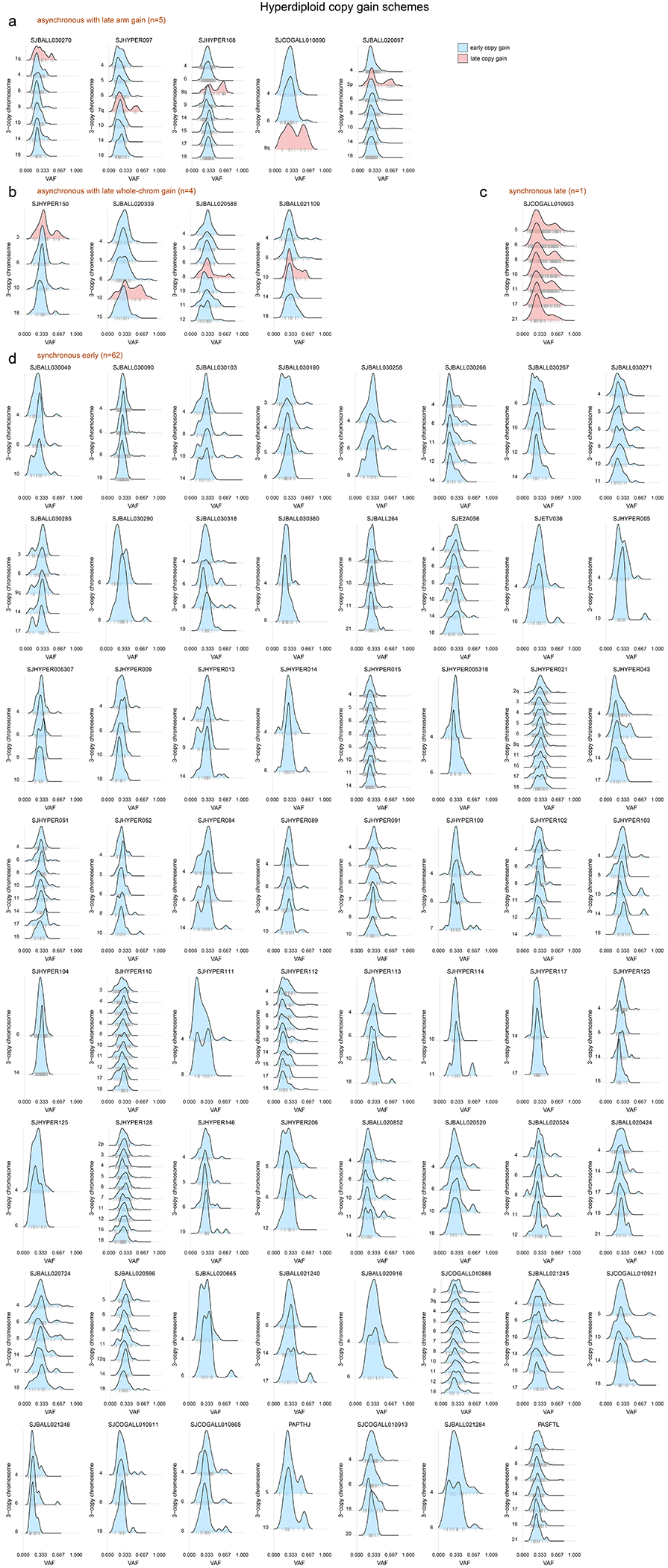

(a) Schematic showing how to infer whether copy gains occurred early or late (relative to the occurrence of SNVs). Two homologous chromosomes are shown before (left), during (blue shaded box), and after (right) a somatic gain of one of the two homologs. Top shows a scenario where SNVs (stars) occurred before copy gains, which would lead to half of SNVs being found on 1 of 3 copies and half on 2 of 3 copies, after the gain. Bottom shows a scenario where copy gains happened early, prior to SNVs, and thus all SNVs occur on 1 of 3 copies. (b) Mutational signature analysis pooling all somatic SNVs in 3-copy regions from B-ALL hyperdiploid (n=110 samples) or iAMP21 (n=7) samples (sequenced by WGS), separated into SNVs found on 1 of 3 copies (VAF ≈ 0.33) or 2 of 3 copies (VAF ≈ 0.67; see Methods). Top shows absolute number of SNVs and bottom shows relative number (percentage). (c) Scheme showing two possible modes of acquiring copy gains in hyperdiploid ALL. Left shows a scenario where all copy gains occur simultaneously (synchronous), such as during a single aberrant mitosis. Right shows sequential acquisition of copy gains (asynchronous) through multiple copy gain events occurring over time. (d) Copy gain schemes in hyperdiploid samples, to test whether copy gains likely occurred simultaneously or sequentially. Top shows examples of the four schemes that were detected across 72 hyperdiploid WGS samples, where only 3-copy chromosomes with at least 20 somatic SNVs in the sample were analyzed, and only samples with two or more chromosomes meeting this criterion were analyzed. On density plots, x-axes show VAF adjusted for tumor purity, and y-axes show mutation density for each 3-copy whole-chromosome or arm gain in the sample. Vertical ticks on the x-axis show individual SNV VAFs; an abundance of VAFs around 0.67 indicates late copy gains since the SNVs occurred prior to the copy gains (2 of 3 copies), while a preponderance of VAFs around 0.33 indicates early copy gains since most SNVs occurred after the copy gains (1 of 3 copies). Blue indicates an inferred early copy gain and red a late copy gain. Bottom shows the percentage of the 72 samples falling into each category. The density profiles for all 72 samples are shown in Extended data fig. 6.

Four scenarios of ploidy evolution were observed in hyperdiploid ALL (Fig. 2c–d). The most common pattern was synchronous early chromosomal gains with somatic SNVs predominantly on 1 of 3 trisomic chromosomes, indicating that copy gains temporally preceded point mutations (83.6% of hyperdiploid samples). Second, we observed a synchronous late pattern in which all copy gains occurred late, as evidenced by mutations present on 2 of 3 trisomic chromosomes (VAF ≈ 0.67, 1.4% of samples). Finally, we observed asynchronous gain with most whole-chromosome copy gains early and (a) one late chromosomal arm gain (6.9%) or (b) one late whole chromosome gain (5.5%) (Fig. 2d, Extended data fig. 6 and Supplementary table 9). The predominance of somatic mutations on 1 of 3 copies (indicating early copy gains) was not simply due to the later UV mutational signature, since even hyperdiploid B-ALLs bearing only clock-like signatures 1 and 5 primarily had the synchronous early pattern of copy gains (88.4% of samples).

By contrast, in iAMP21, UV-associated mutations occurred prior to most chromosomal gains, as demonstrated by the presence of UV-induced SNVs on both 1 of 3 and 2 of 3 trisomic regions (Fig. 2b, Supplementary table 10)24. These findings are consistent with the notion of a chromosomal “big bang” early event in the evolution of hyperdiploid ALL, with simultaneous acquisition of trisomies prior to mutational evolution; by contrast, iAMP21 is characterized by repetitive breakage-fusion-bridge cycles generating complex subchromosomal amplification31.

ALL subtypes are driven by different biological pathways

Of the 266 known or putative driver genes affected by SNVs/indels/focal deletions (Supplementary Datasets 1–2), 214 (80%) were altered in both B- and T-ALL (Supplementary tables 11–12). CDKN2A alterations (30.7% of B-ALL, 70.3% of T-ALL, Fig. 3a) were associated with high-risk disease (Supplementary Dataset 3 and Supplementary table 13). 93 patients had focal CDKN2A deletions not involving CDKN2B, whereas CDKN2B deletions not involving CDKN2A were rare, and deleterious sequence variants were only observed in CDKN2A (Supplementary Dataset 1), supporting a pathogenic role for inactivation of INK4A/ARF, but not INK4B in ALL. We also observed key lineage differences, with 49 putative driver genes specific to B-ALL, including multiple distinct histone cluster deletions on 6p22, ADD3, IDH1 and SLX4IP (Fig. 3a, Extended data fig. 7a–c and Supplementary table 6). Three genes were specific to T-ALL (MYCN, 1.8%; RPL10, 5.2% and FBXO28, 0.8%; Fig. 3b).

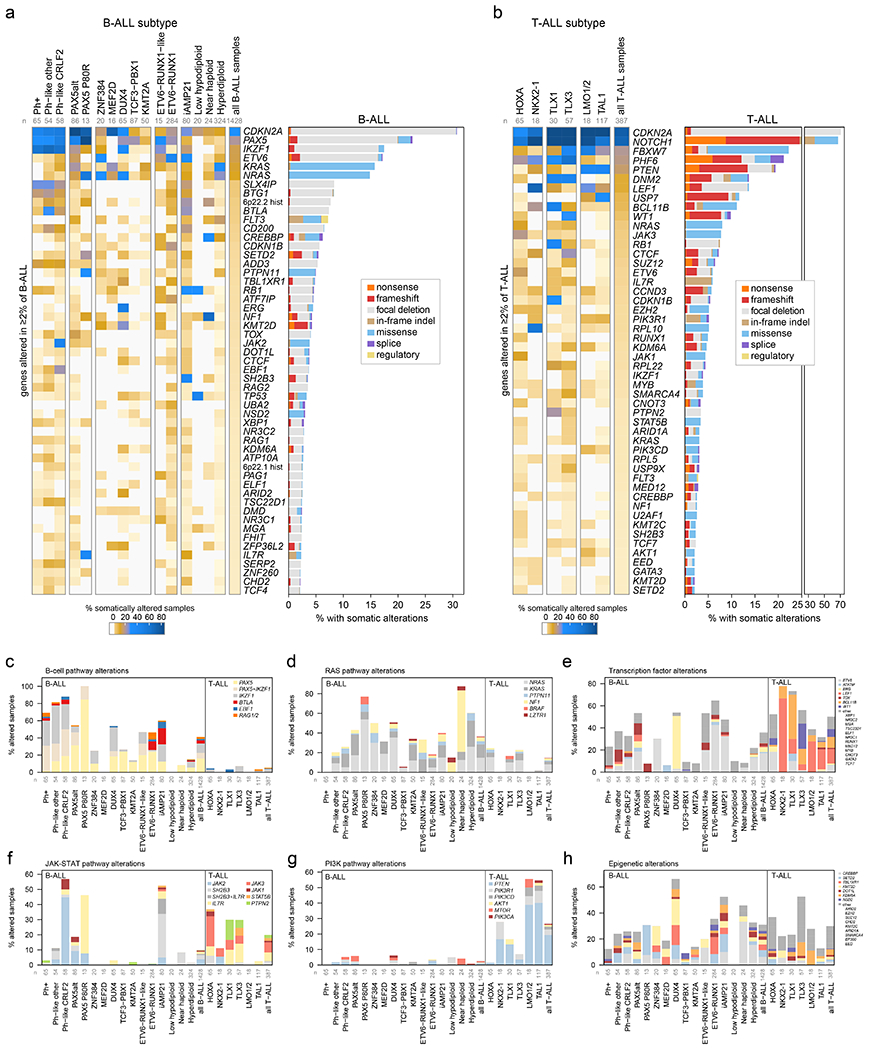

Figure 3. Mutational landscapes across ALL subtypes.

ALL samples with characterization of both somatic SNVs/indels and copy alterations are shown (WGS samples as well as WES samples which also had SNP array analysis), totaling 1,428 B-ALL and 387 T-ALL samples. Subtypes with at least 15 samples are shown. (a) Left, heatmap showing the percentage of samples in each subtype (column) with somatic alterations (excluding fusions) in all genes (rows) altered in at least 2% of B-ALL samples. Right shows the percentage of samples with alterations in each gene, with the alteration type indicated by color. In samples with more than one type of alteration, only the alteration higher up in the key list (starting with “nonsense”) is shown. “Regulatory” refers to FLT3-region focal deletions thought to increase FLT3 expression. n below subtype name indicates number of samples analyzed in each subtype. (b) As in (a) but for T-ALL. (c-h) Percent of samples with somatic alterations (excluding fusions) in each pathway, broken down by subtype. The specific gene altered is indicated in color. In samples where more than one gene is altered in the pathway, the gene towards the top of the legend is only shown. Frequently co-occurring gene alterations are shown as a separate color (e.g. samples with both PAX5 and IKZF1 alteration in (c)). Sample numbers for each subtype are as in (a-b).

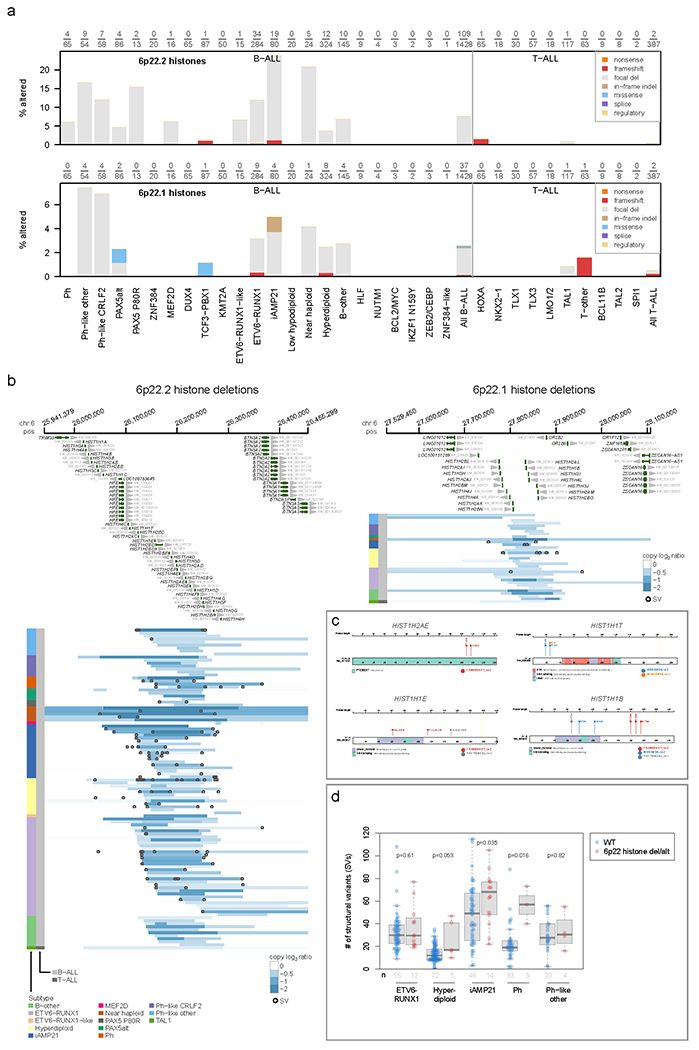

The histone deletions (and occasionally frameshifts) involved a cluster of 32 histone genes (H1, H2A, H2B, H3, H4)32–35 at 6p22.2 (7.6% of B-ALL samples, most commonly in iAMP21, near haploid, Ph-like, PAX5 P80R, and ETV6-RUNX1 subtypes) and 21 histone genes at 6p21.1 (2.6% of B-ALL samples) that were frequently heterozygous deletions of a subset of genes in each cluster (Extended data fig. 7a–c), suggesting that loss of all histone genes in each of the regions is deleterious. The burden of SVs was higher in 6p22 histone-altered ALL samples in multiple subtypes (Extended data fig. 7d), consistent with the requirement of histones in DNA damage responses36,37, and supporting a role in the genesis of iAMP21 ALL (Extended data fig. 7a) where repeated cycles of SV generation occur on chromosome 2138.

SNVs/indels and CNAs were integrated to identify disrupted biological pathways (Fig. 3c–h and Supplementary table 14). Alterations of transcription factors (other than those regulating B-cell development) and epigenetic regulators were common in both B- and T-ALL (36% vs 50%, P=5.58x10−7 by two-sided Fisher’s exact test and 31% vs 30%, P=0.71, respectively; Fig. 3e, h). Pathways enriched in B-ALL included Ras signaling (36% vs 15%, P=1.49 x 10−17)39 and B-cell transcription factors (41% vs 5%, P=1.26 x 10−49)40, and T-ALL was enriched for alterations in the NOTCH pathway (1% vs 71%, P=8.18x10−207)41, cell cycle regulation (predominantly CDKN2A, 38% vs 74%, P=2.06x10−37)42, JAK-STAT signaling (10% vs 20%, P=3.40x10−7)17 and PI3K signaling (3% vs 27%, P=1.71x10−44; Fig. 3c–h)43. Alterations of the transcription factor genes IKZF1, PAX5 and ETV6 were common in B-ALL (17%, 23% and 17%, respectively), whereas alterations of LEF1, WT1 and BCL11B were almost exclusively present in T-ALL (14%, 10% and 11%, respectively). Alterations were commonly subtype-associated (Supplementary Datasets 4–5 and Supplementary table 12). CREBBP alterations were enriched in near haploid (33%) and hyperdiploid B-ALL (15%), whilst alterations of SETD2 were the highest in PAX5 P80R (23%, Fig. 3a). SMARCA4 alterations were common in TLX3 T-ALL subtype (14%). DUX4-rearranged ALL had the highest prevalence of epigenetic pathway alterations (66%), dominated by KMT2D, TBL1XR1 and SETD2 (Fig. 3h).

Hyperdiploid and near haploid ALL showed striking similarity of gene expression (Extended data fig. 2b) and mutations, with frequent epigenetic pathway alterations driven by CREBBP (Fig. 3h) and high frequency of Ras pathway alterations (60% and 88%), driven by NRAS, KRAS and PTPN11 mutations in hyperdiploid39 and NF1 deletion in near haploid ALL44 (Fig. 3d). The similar expression profiles may have been due to (a) increased relative dosage of chromosomes 10, 14, 18, and 21, as hyperdiploid samples frequently gained these chromosomes, while near haploid often lost all chromosomes except these (Extended data fig. 2b, right); and/or (b) similar cells of origin or developmental stages, consistent with the subtypes being diagnosed at similar ages (median 4.3 years for hyperdiploid and 5.0 years for near haploid; Extended data fig. 2d). Low hypodiploid ALL exhibited common biallelic alteration of TP53 due to mutation and aneuploidy (85%; somatic 41%, germline 44%), and alteration of RB1 (30%) and IKZF2 (25%)44. ETV6-RUNX1-like ALL7 harbored non-ETV6-RUNX1 rearrangements involving ETV6 (49%), IKZF1 (14%), TCF3 (8%), CRLF2 (5%) and ERG (3%; Supplementary table 5). Forty percent (6 of 15) of ETV6-RUNX1-like cases lacked rearrangement of a putative driver but most harbored somatic deletions of transcription factors (e.g. ETV6 (n=2), IKZF1 (n=1), PAX5 (n=3)). We identified a similar prevalence of B-cell transcription factor alterations in ETV6-RUNX1 (46%) vs. ETV6-RUNX1-like (47%) subtypes, with a higher frequency of BTLA-CD200 deletions in ETV6-RUNX1 (13% vs 0%), while IKZF1 alterations were more common in ETV6-RUNX1-like (2% vs 27%; Fig. 3a). TBL1XR1 alteration was exclusively identified in ETV6-RUNX1 (14% vs 0%), whilst deletion of ARPP21 was enriched in ETV6-RUNX1-like (0% vs 27%). Thus, it is interesting that two subtypes with a similar gene signature harbor different driving and secondary alterations also with different clinical outcomes (Extended data fig. 2c). Distinct clusters of Ph+ B-ALL cases were observed by tSNE (Ph1, Ph2 and Ph3; Extended data fig. 2b) with variable secondary genomic alterations: IKZF1 common in Ph1/Ph2 (76% vs. 88% vs. 13%, respectively), but PAX5 more common in Ph1 (48% vs. 13% vs. 13%), and aneuploidy most common in Ph3 (0% vs. 8% vs. 45%).

Co-mutation and mutual exclusivity analysis within each ALL subtype (Supplementary Dataset 6 and Supplementary table 15) revealed significant co-occurrence (P < 0.05, Q < 0.05) of JAK1 and JAK3 alterations in HOXA T-ALL; of PHF6 with DNM2, EZH2, and JAK1 in HOXA T-ALL; of PAX5 and IKZF1 alterations in Ph+ B-ALL; and of chromosome 9p and 20q deletions in Ph-like B-ALL (also associated with ROS-related mutational signature 18, Extended data fig. 5e). Significant mutual exclusivity was observed between FLT3 and Ras alterations (NRAS or KRAS) in hyperdiploid B-ALL; between CDKN2A and SUZ12 in TLX3 T-ALL and between IKZF1 alterations observed in Ph1 and Ph2 and whole-chromosome gains observed in Ph3 B-ALL.

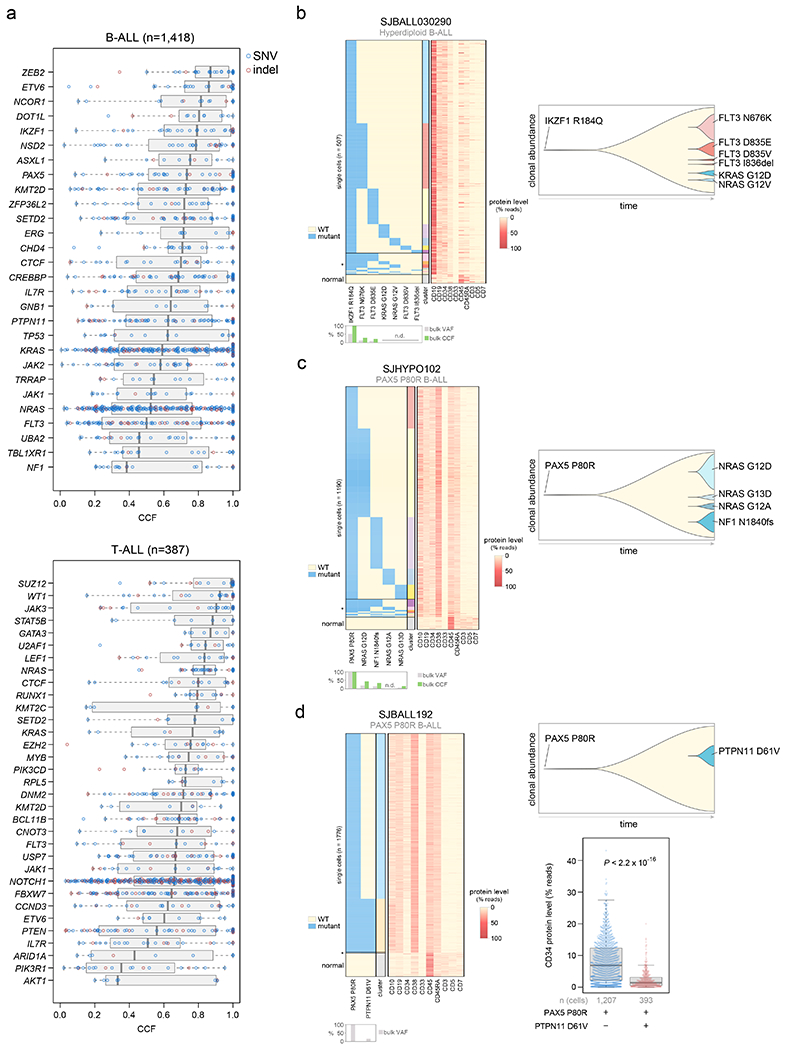

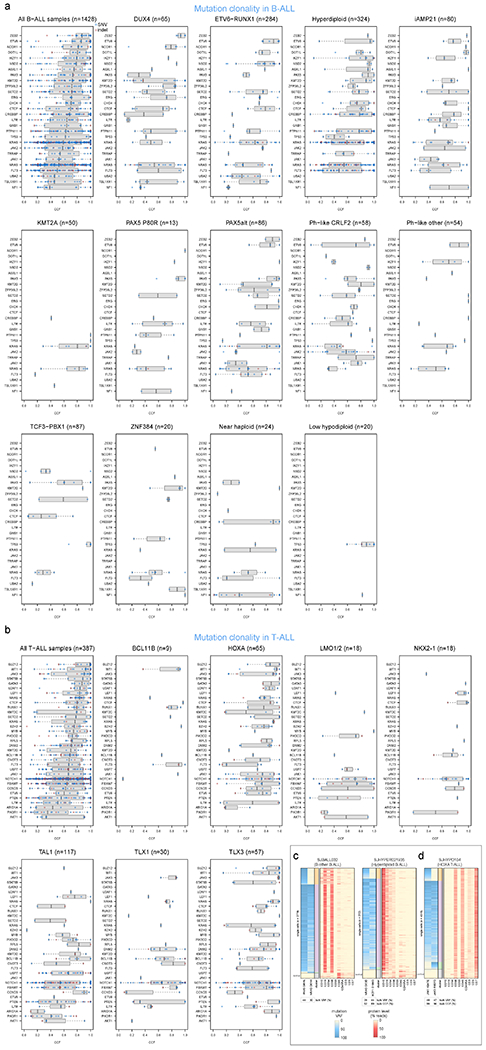

Driver mutation clonality

In B-ALL, the cancer cell fractions (percent of tumor cells bearing mutations, or CCFs)45 of lineage-related driver alterations (ETV6, IKZF1, and PAX5) were high, indicating early occurrence, whereas kinase signaling point mutations (KRAS, NRAS, JAK1, JAK2, FLT3, etc.) were usually subclonal, suggesting later evolutionary occurrence (Fig. 4a, Extended data fig. 8a, and Supplementary table 16). To validate this, we performed simultaneous single-cell DNA sequencing and cell-surface protein expression analysis of three B-ALL patients each having one high-CCF lineage-related mutation (in IKZF1 or PAX5) plus multiple lower-CCF kinase signaling mutations. This confirmed that lineage-related mutations occurred early as they were present in all leukemia cells, while kinase-related mutations appeared later and independently in multiple clones by convergent evolution (Fig. 4b–d). Kinase mutations were often mutually exclusive indicating their presence in different clones (e.g. FLT3 N676K and FLT3 D835E in a hyperdiploid B-ALL sample, Fig. 4b). In one patient, a late-appearing clone bearing PTPN11 D61V had a lower cell-surface protein level of the hematopoietic stem cell marker CD34 (Fig. 4d), suggesting differing hematopoietic differentiation between clones. In two patients, lineage and kinase-related mutations co-occurred in most cells and their order of occurrence could not be resolved (Extended data fig. 8c).

Figure 4. Clonality of driver SNVs and indels.

(a) The cancer cell fraction (CCF, x-axis), i.e. the percentage of cancer cells harboring each mutation, of alterations in each driver or putative driver gene is shown in all B-ALL samples (top) or all T-ALL samples (bottom). The CCF was calculated based on the VAF, copy number, and tumor purity of each sample; calculated CCFs above 1.0 were considered 1.0. Samples with both SNV/indel and copy number characterization (WGS or WES plus SNP array) are shown. Each plot shows the number of samples analyzed (n) at top. For most samples, only SNVs/indels in 2-copy regions were analyzed, except for near haploid and low hypodiploid where only SNVs/indels in 1-copy regions were analyzed. SNVs are shown in blue and indels in red; each point represents one somatic mutation. Boxplots show median (thick center line) and interquartile range (box). Whiskers are described in R boxplot documentation (a 1.5*interquartile range rule is used). Known or putative driver genes with at least 10 SNVs/indels in 2-copy regions across all B-ALL samples, or 8 SNVs/indels in 2-copy regions across all T-ALL samples, are shown. (b-d) Simultaneous targeted single-cell DNA sequencing and cell-surface protein expression analysis of three B-ALL samples using the Tapestri platform. Left shows a heatmap with each row representing one cell, and each column representing either one mutation (left side) or one protein (right side). Mutation presence is indicated by blue color, while protein level (as a percent of all protein-associated reads detected in the cell) is indicated by red color. Asterisk (*) indicates likely cell doublets or dropout artifacts, and below these likely normal cells are indicated (neither of which were included in the clonal composition determination at right). The bulk VAF of each mutation is indicated below, along with bulk CCF (if copy number was available). n.d., not detected in bulk sequencing. On the right side of each panel is shown a fish plot showing clonal composition as determined by single-cell sequencing, with x-direction indicating time and y-direction indicating relative CCF of each clone (represented by different colors) as determined by single-cell DNA sequencing. The rightmost edge shows the clonal composition at diagnosis. At bottom-right in (d), the cell-surface protein level of CD34 (percent of reads in each cell assigned to CD34), is shown in a clone with vs. without PTPN11 D61V in patient SJBALL192. P value is by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Boxplot shows median (thick center line) and interquartile range (box). Whiskers are described in R boxplot documentation (a 1.5*interquartile range rule is used).

By contrast to B-ALL, in T-ALL certain kinase-related alterations had high CCFs, including JAK3 and NRAS (median CCF >80%, Fig. 4a, Extended data fig. 8b). Further, JAK1 and JAK3 mutations co-occurred in the same clone in one HOXA T-ALL patient (Extended data fig. 8d), indicating these genes’ mutational co-occurrence in this subtype (Supplementary Dataset 6) is not due to convergent evolution in different clones.

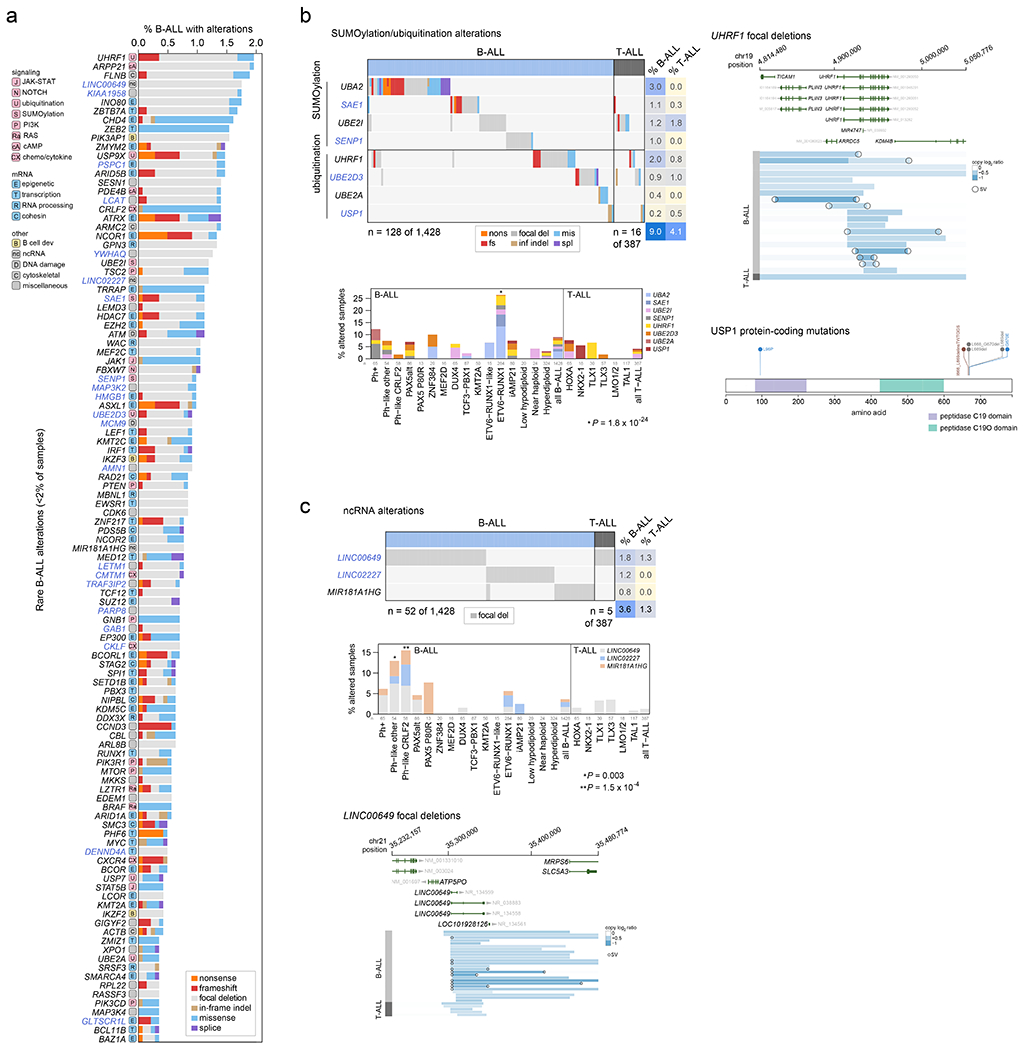

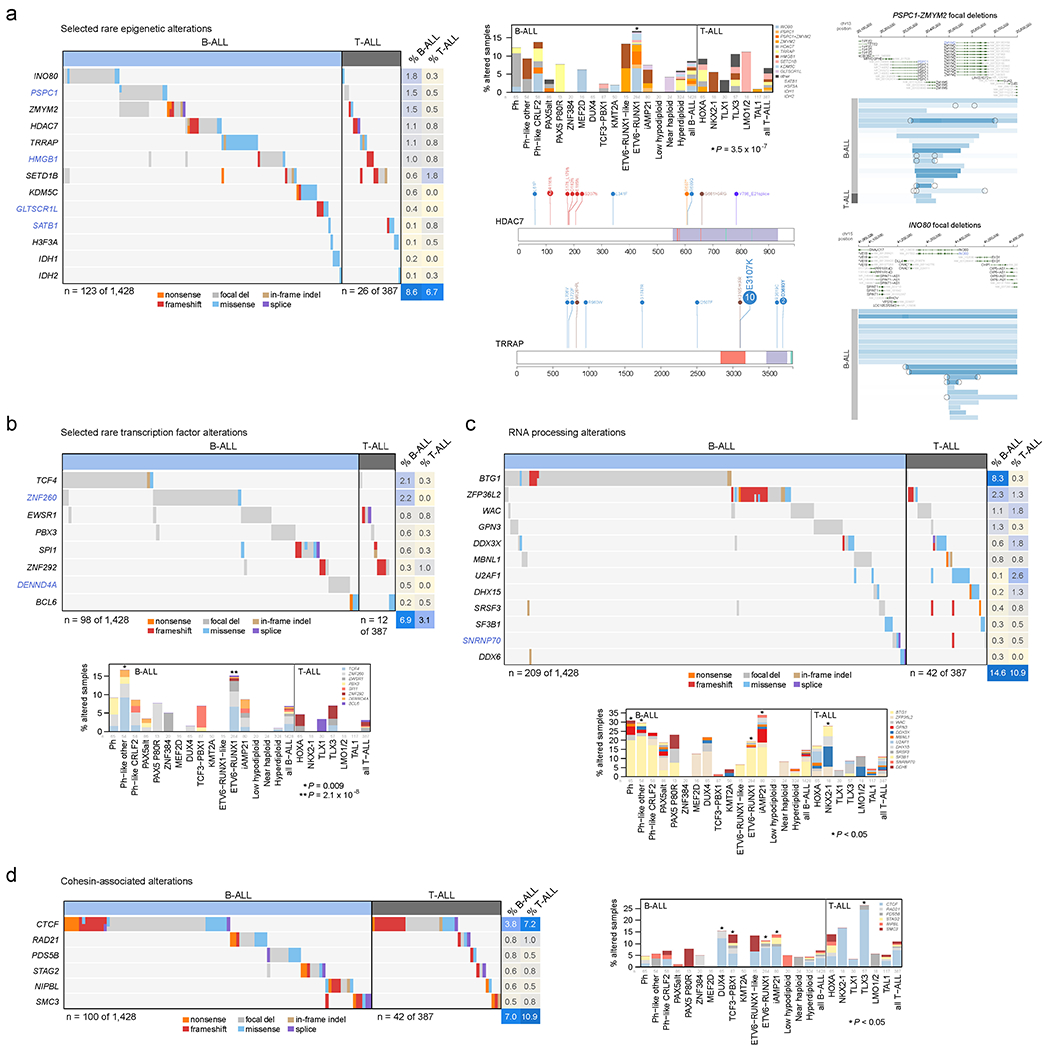

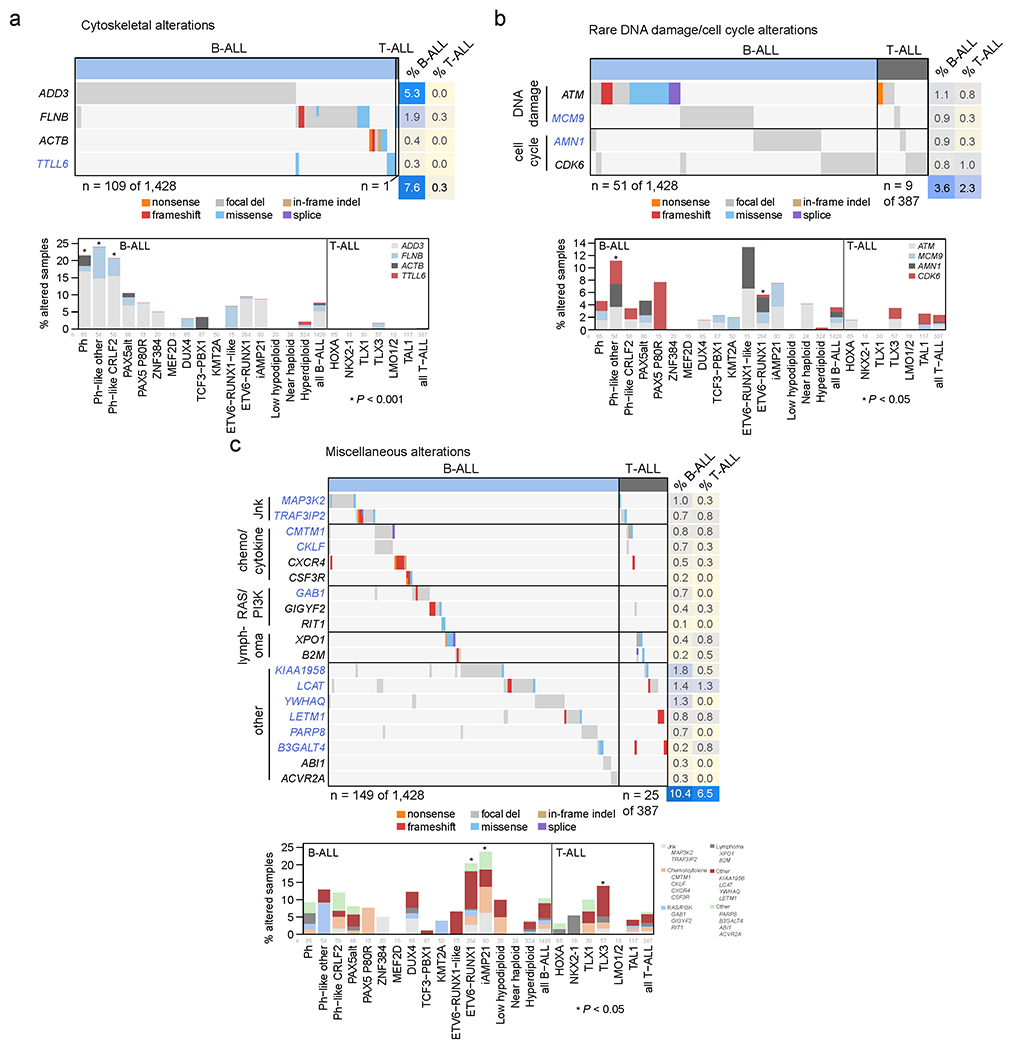

Protein modification, RNA machinery and cohesin alterations

Among the 376 putative driver genes, 157 were altered (by coding SNV/indel or focal deletions) in <2% of B-ALL, while 119 were altered in <2% of T-ALL, but collectively, were altered in 54.7% of B-ALL (157 genes) and 51.2% of T-ALL (119 genes). Seventy genes altered in <2% of all samples had not been previously reported in ALL, including 43 genes previously reported in non-ALL tumors and 27 genes not reported as drivers in any malignancy (blue text in Fig. 5 and Extended data fig. 9–10; Supplementary table 6; Supplementary Dataset 1). Of these, predicted loss-of-function or activating alterations in several genes regulating SUMOylation and ubiquitination, and their binding partners (termed protein modification), were present in 9% of B-ALL and 4% of T-ALL (Fig. 5b). Most notable were alterations disrupting UBA2 and SAE1, both of which form a heterodimeric complex essential for SUMOylation46, in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL. Alterations affecting ubiquitination included focal deletions of UHRF1 and sequence mutations in USP1 (Fig. 5b). Collectively, disruption of genes involved in RNA machinery accounted for 15% of B-ALL and 11% of T-ALL, with enrichment in Ph+, Ph-like and iAMP21 B-ALL subtypes (driven by deletions of BTG1) and in NKX2-1-rearranged T-ALL driven by DDX3X, encoding a member of the DEAD-box helicases (Extended data fig. 9c). Alterations in the cohesin complex were present in 7% of B-ALL and 11% of T-ALL, with the highest frequency observed in the TLX3 subtype driven by alterations of CTCF (Extended data fig. 9d). Genes involved in cytoskeletal assembly were almost exclusively altered in B-ALL (8%) and were largely driven by focal deletions in ADD3 and the filamin family member, FLNB, in Ph+ and Ph-like ALL (Extended data fig. 10a). We also observed somatic alterations in various non-coding RNA genes, including focal deletions of LINC00649, LINC02227, and MIR181A1HG, particularly in Ph+ and Ph-like subtypes (Fig. 5c). MIR181A1HG is expressed in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells with decreasing expression during myeloid differentiation47, suggesting that deletions may affect lineage fate. Thus, as observed in solid tumors48, a “long tail” of somatically altered genes converging on common pathways is a hallmark of ALL.

Figure 5. Alterations in rare ALL genes.

(a) Percent of B-ALL samples (out of 1,428 with either WGS or WES plus SNP array) with alterations in each infrequently altered gene (altered in <2% of B-ALL samples and ≥0.3% of samples). Alteration type is indicated in color; in samples with more than one type of alteration, only the alteration higher up in the key list (starting with “nonsense”) is shown. Putative driver genes not previously reported in cancer are shown in blue text. The pathway or function of each gene is indicated in boxed letters above each gene (see legend at bottom). (b) Alterations in selected genes involved in SUMOylation or ubiquitination, or the removal of these modifications. Left shows an oncoprint showing only samples with alterations in at least one of these genes, with alteration indicated by color and the percentage of samples in B-ALL or T-ALL altered at right. Bottom-left shows the percentage of each subtype with alterations in these genes, color-coded by the specific gene altered. In samples with alterations in more than one gene, only the top-most gene in the legend is shown. The value of n indicates the number of samples analyzed in each subtype. Right shows example gene alterations, including focal deletions (5 Mb or less; blue indicates degree of copy loss in each sample (row) and circles indicate SVs which were available for WGS samples only) in UHRF1 and sequence alterations in USP1. P value (asterisk) is by two-sided Fisher’s exact test comparing prevalence in the ETV6-RUNX1 subtype vs. all non-ETV6-RUNX1 B-ALL samples. (c) As in (b) but for putative driver alterations in non-coding RNA genes. P values (asterisks) are by two-sided Fisher’s exact test comparing prevalence in the indicated subtype vs. all B-ALL samples not belonging to that subtype.

Genomic determinants of outcome

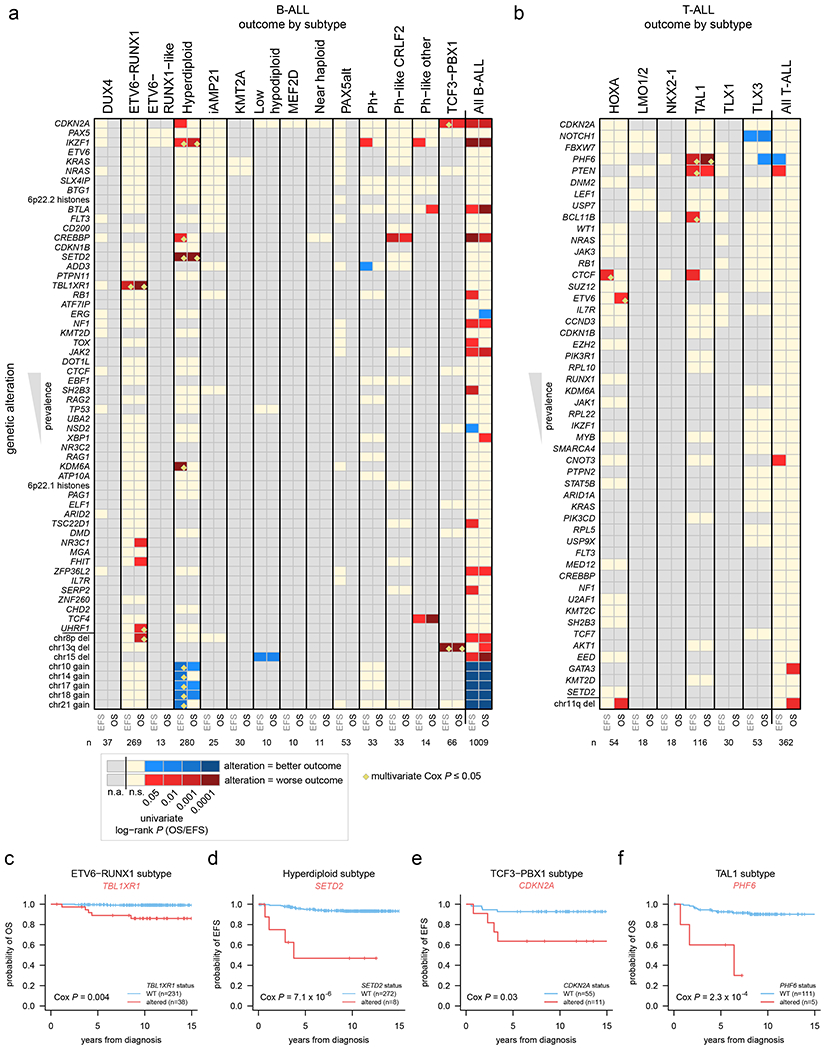

The overall survival (OS) for each ALL subtype is shown in Extended data fig. 2c and 3c. The prognostic contribution of secondary genomic alterations was assessed by univariate analysis for OS, event-free survival (EFS), and the presence/absence of minimal residual disease (MRD) at the end of induction therapy in B-ALL and T-ALL, and within each ALL subtype (Fig. 6a–b, Supplementary Datasets 7–8 and Supplementary tables 17–19). Alterations significantly associated with OS or EFS within specific subtypes by univariate analysis (P ≤ 0.05 by log-rank test, shown by red and blue cells in Fig. 6a, b) were further analyzed by multivariate Cox proportional-hazards analysis incorporating age, WBC count, MRD presence/absence, and treatment protocol (P ≤ 0.05 shown by yellow diamonds in Fig. 6a, b; Supplementary tables 20–21; see Methods). In B-ALL, we confirmed the inferior outcome of IKZF1plus compared to patients with IKZF1 deletion who did not fulfill the IKZF1plus definition (10-year OS 73.8% vs 80.9%, P=6 x 10−11 by log-rank test)49. Alterations associated with inferior outcomes in specific B-ALL subtypes included TBL1XR1 in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL (5-year OS 89.0% vs. 99.6% in altered vs. non-altered, P=0.004 by multivariate Cox analysis), SETD2 in hyperdiploid ALL (5-year EFS 46.9% vs. 94.9%, P=7x10−6), and CDKN2A in TCF3-PBX1 ALL (5-year EFS 63.6% vs. 92.7%, P=0.03) (Fig. 6c–e). In T-ALL, alterations of PHF6 were associated with poor OS in the TAL1 subtype (60.0% vs. 92.6%, P=2.3 x 10−4) (Fig. 6f). Increased age was not the explanation for the poor outcomes associated with these alterations. Indeed, nearly all alterations significantly associated with outcomes by multivariate analysis (yellow diamonds in Fig. 6a, b) were not significantly associated with age, with the exception of TBL1XR1 alterations (median 4.9 years old at diagnosis vs. 3.8 years for non-altered; P=0.0002 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test) and UHRF1 alterations (5.4 vs. 4.1 years; P=0.04) in ETV6-RUNX1 B-ALL, though these alterations were still significantly associated with outcomes independent of age by multivariate analysis (Fig. 6a, b; Supplementary tables 20–21).

Figure 6. Association of secondary genetic alterations with outcome.

(a) Heatmap showing overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) in each B-ALL subtype based on the presence of specific somatic alterations. Each row represents a specific gene somatically altered, sorted by most frequently altered in B-ALL (top) to least frequently altered (bottom). The bottom-most portion shows selected large copy gains and losses (not sorted by frequency) based on their significant association with outcome. Columns represent B-ALL subtypes, and EFS (left) and OS (right) were analyzed for each subtype. P values were first calculated by univariate two-sided log-rank test, and significant (0.05 or less) values are shown in red (if alteration was associated with worse outcome) or blue (alteration associated with improved outcome; see scale at bottom). Tan color indicates a P value that was not significant (n.s.), and gray indicates an insufficient number of somatically altered samples in the subtype for analysis (n.a.; at least 3 altered and 3 wild-type samples were required for the gene to be analyzed within the subtype; at least two samples had to have events (death, relapse, etc.) in the wild-type or altered group as well). Significant associations (P ≤ 0.05 by univariate analysis) were then subject to multivariate Cox proportional-hazards analysis (Methods) and associations with P ≤ 0.05 by this multivariate method are marked by yellow diamonds (not performed for the “all B-ALL” and “all T-ALL” analyses). The number of samples analyzed in each subtype is indicated at bottom and includes samples with SNV/indel and copy data (WGS, or WES plus SNP copy array) and available outcome information. All B-ALL samples, regardless of subtype, were also analyzed in the rightmost heatmap column. (b) Heatmap showing OS and EFS in each T-ALL subtype based on somatic alterations, similar to panel (a) but for T-ALL. (c-f) Kaplan-Meier OS or EFS curves showing selected genetic alterations with significant outcome associations within indicated subtypes. P values are by multivariate Cox proportional-hazards analysis.

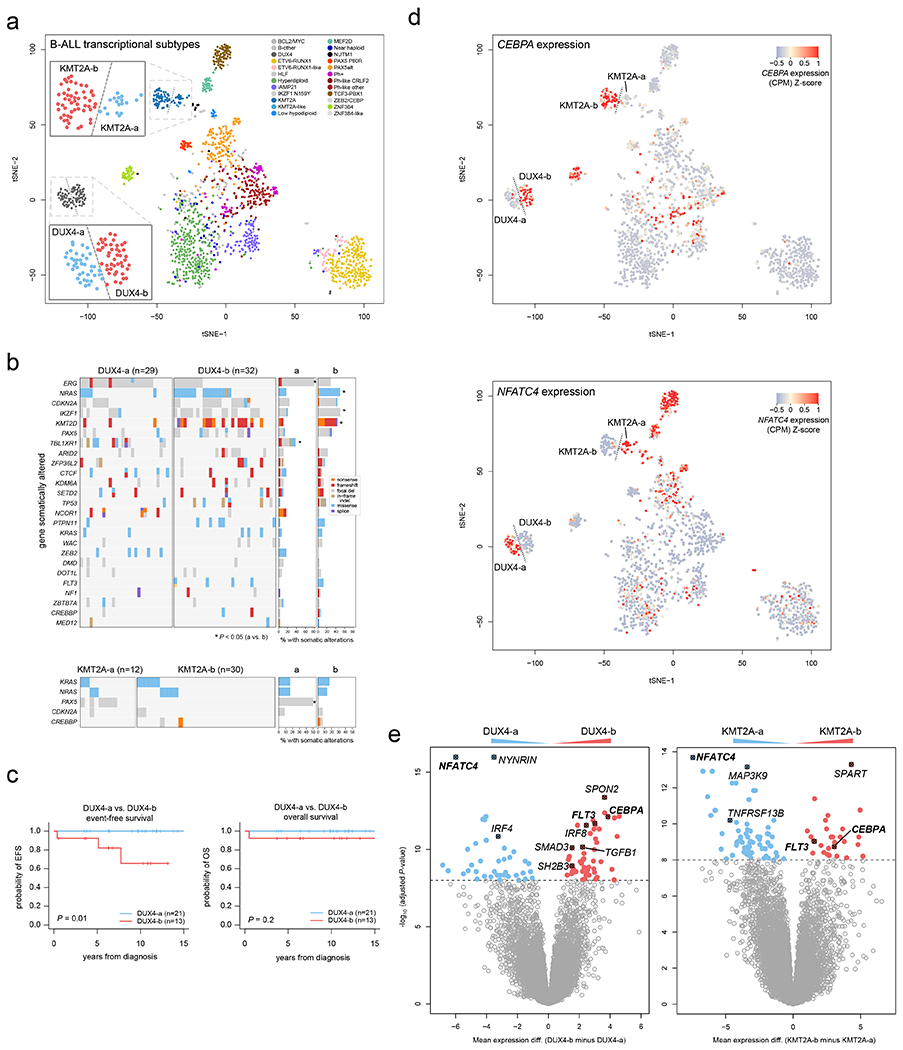

Subtypes within DUX4- and KMT2A-rearranged ALL

We identified distinct gene expression clusters for DUX4- and KMT2A-rearranged subtypes by tSNE analysis, termed DUX4-a and DUX4-b, and KMT2A-a and KMT2A-b (Fig. 7a). The DUX4-a and -b subgroups had differing mutational landscapes, with ERG and TBL1XR1 alterations enriched in DUX4-a and NRAS, IKZF1, and KMT2D enriched in DUX4-b (Fig. 7b); the latter subgroup also had worse EFS but not OS by univariate analysis (Fig. 7c; multivariate analysis was not possible). PAX5 alterations were enriched in KMT2A-a compared to KMT2A-b (Fig. 7b), though no difference in EFS or OS survival was observed. The DUX4-a and KMT2A-a subgroups had high expression of NFATC4, whilst the reciprocal subtypes DUX4-b and KMT2A-b showed high expression of CEBPA and FLT3 (Fig. 7d–e and Supplementary tables 22–23). NFATC4 is expressed in pre-B and immature B cells50 in mice, whereas CEBPA and FLT3 are co-expressed in common lymphoid progenitors and pre-pro-B cells51, suggesting a developmental difference between a and b subgroups.

Figure 7. Dichotomous CEBPA and NFATC4 expression identifies subgroups of KMT2A-and DUX4-rearranged subtypes.

(a) tSNE analysis of B-ALL transcriptional profiles including 1,464 B-ALL samples sequenced by RNA-seq. Each point represents one sample. Legend shows the samples colored by subtype, and dotted lines delineate visually apparent subgroups further subdividing the KMT2A and DUX4 subtypes. Zoomed-in regions showing DUX4-a vs. DUX4-b and KMT2A-a vs. KMT2A-b subgroups are shown. (b) Heatmaps showing mutations present in DUX4-a vs. DUX4-b (top), or KMT2A-a vs. KMT2A-b (bottom) subgroups. Each row indicates a gene somatically altered in the subtype, sorted by most frequently (top) to least frequently (bottom) altered within the DUX4 or KMT2A subtype. Each column is one sample. Right indicates the percentage of samples with somatic alterations in each gene in the a vs. b subgroups, with significant P values by two-sided Fisher’s exact test (a vs. b subgroups) shown with asterisks. Exact P values are 9.3 x 10−5 (ERG), 0.014 (NRAS), 0.032 (IKZF1), 0.0045 (KMT2D), 8.3 x 10−5 (TBL1XR1), and 1.8 x 10−4 (PAX5). Variant types are indicated by color as shown in the key at right in the DUX4 plot. This analysis includes samples that had RNA-seq, SNV/indel, and copy number characterisation (RNA-seq plus WGS, or RNA-seq plus WES plus SNP array), with sample numbers indicated above each plot. (c) Kaplan-Meier curves showing event-free (left) or overall survival comparing DUX4-a and DUX4-b subgroups. P values are by two-sided log-rank test. (d) tSNE plots as in (a), including 1,464 B-ALL samples, except that the expression of CEBPA (top) or NFATC4 (bottom) are indicated by color, with red indicating high expression and blue/gray indicating lower expression (see scale). (e) Left, differential gene expression with Limma, comparing the DUX4-a (n=36 samples) and DUX4-b (n=43) subgroups, defined as shown in (a). X-axis represents the log2 fold change in gene expression comparing DUX4-b minus DUX4-a, where values above zero indicate an increase in DUX4-b and below zero indicate an increase in DUX4-a. Y-axis represents the −1*log10 (adjusted P value) for each gene (represented as points). The top differentially expressed genes are shown in red (increased in DUX4-b) or blue (increased in DUX4-a), and selected genes are highlighted. Right, differential gene expression comparing KMT2A-a (n=17) vs. KMT2A-b (n=45).

Germline variants in ALL

Forty-seven of 1,703 patients with germline WES (2.8%) had pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variants known to promote cancer development, including in TP53 (n=9, including 8 low hypodiploid B-ALL cases), ETV6 (n=9, including 5 in hyperdiploid and 2 in ETV6-RUNX1-like B-ALL), BRCA2 (n=8) and BRCA1 (n=6) spread across multiple B- and T-ALL subtypes, and PTPN11 (n=3). An additional 5 patients had germline variants without known germline cancer association, but which are somatically altered in ALL, including two HDAC7 variants (Supplementary table 24).

Discussion

This study highlights the complex genomic relationship between molecular subtypes and their secondary alterations that drive leukemogenesis and outcome in childhood ALL. Unexpectedly, most pediatric ALL subtypes had a similar number of putative driver gene alterations as adult cancers (4-5 per sample)52, perhaps due to accelerated rates of focal deletions which are promoted by RAG1/2-mediated recombination in lymphocyte progenitor cells53,54. However, several B-ALL subtypes had only 2-3 putative driver alterations per sample (including KMT2A-rearranged, TCF3-PBX1, and aneuploid subtypes), perhaps due to earlier age of onset or a lower requirement for secondary alterations of putative driver genes.

Conflicting studies have proposed that acquisition of hyperdiploidy is a single early event55,56, while others suggest sequential and ongoing acquisition of chromosome gains57. Our results indicate that the majority of hyperdiploid ALL originates from a “big bang” of simultaneous or closely temporally juxtaposed chromosomal gains in a single aberrant mitosis or in multiple cell divisions within a short time frame. Chromosomal gains are likely commonly acquired in utero followed by mutational evolution, often involving epigenetic regulators and Ras signaling. By contrast, in B-ALL with iAMP21, the characteristic copy gains commonly postdate sequence mutations, consistent with the later age of onset of this subtype. Collectively, these observations support a model for the development of the majority of subtypes of childhood B-ALL in which aneuploidy or oncogenic translocations early in life are the initiating leukemogenic events. These are followed by focal deletions, including RAG-mediated deletions that are a by-product of lymphoid expansion that accompanies maturation of the immune response in early childhood. Such deletions and sequence mutations are selected for if they further promote (pre-)leukemic fitness.

It is unclear whether UV-associated signature 7, which we detected in a subset of aneuploid ALL samples, is caused by UV itself or a biochemical mimic. However, we suspect signature 7 is UV-induced in ALL. First, we previously observed signature 7 primarily ALL patients of European ancestry but not those of African descent24, and in this study we likewise found a trend towards signature 7 enrichment in non-African ancestry patients (34.3% signature 7-positive among hyperdiploid, iAMP21, and near haploid B-ALL) compared to African ancestry patients (9.1%; P = 0.10 by Fisher’s exact test). Second, the highest incidence of ALL occurs in patients of European ancestry, with a lower incidence in patients of African descent24. Third, extensive chemical profiling has not revealed biochemical causes of signature 7 outside of UV58. Fourth, the abundance of signature 7 does not increase with age, consistent with an intermittent environmental exposure such as UV. Finally, in hyperdiploid B-ALL signature 7 is only present on 1/3 alleles in 3-copy regions, consistent with UV-induced mutations appearing after copy gains, which likely occur in utero30 where UV exposure is unlikely (whereas signature 7 mutations on 2/3 alleles would indicate prenatal exposure). UV light is capable of penetrating skin sufficiently to affect dermal blood59, and since hyperdiploidy is often detectable at birth in preleukemic blasts from peripheral blood30,60, UV light may affect these pre-malignant blasts in circulation in dermal skin and thus promote mutagenesis leading to frank ALL. Lymphocytes in general are susceptible to UV-induced mutagenesis as signature 7 has been detected in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas61.

The late appearance of kinase signaling point mutations involved in the Ras and JAK-STAT pathway in our B-ALL cohort and prior studies showing the unpredictable nature of their convergence and extinction at relapse62 cautions against therapeutic targeting of these alterations. However, in T-ALL certain kinase alterations, including JAK3 and NRAS, appear to be early events and may merit pharmacological targeting. The KMT2A-b subgroup may be preferentially susceptible to FLT3 inhibitors, recently used in clinical trials of KMT2A-rearranged B-ALL63, based on higher FLT3 expression.

ETV6-RUNX1 and hyperdiploid ALL are the most common subtypes with extremely good outcomes, yet a subset of these patients relapse, the reasons for which are still unclear, in part as many prior comprehensive sequencing studies have focused on high risk subtypes. However, defining the drivers of treatment failure in standard-risk patients is crucial as approximately half of all relapses occur in children initially diagnosed with standard-risk disease. A notable finding of this study is that specific secondary mutations, particularly in epigenetic regulators (TBL1XR1 in ETV6-RUNX1 and SETD2 in hyperdiploid ALL), may improve risk stratification. Patients lacking these mutations had OS rates over 99%, while those with mutations had significantly inferior survival. We did not confirm the prognostic impact of the NOTCH1/FBXW7/RAS/PTEN classifier in all T-ALL cases64 but show subtype specificity, with NOTCH1 mutations having a favorable outcome in TLX3 and PTEN deletions predicting poor outcome in the TAL1 subtype, indicating that future risk stratification classifiers should consider both genetic alterations and molecular subtypes.

Overall, we identified 376 putative driver genes in ALL. Although the list of individually altered putative drivers is long, and the genes involved vary between patients and subtypes, these drivers converge on key pathways whose alteration is often essential to initiate and facilitate transformation: perturbation of lymphoid maturation, transcriptional deregulation, cell cycle regulation, multiple types of chromatin modification, and kinase signaling. Seventy of these have not been identified in ALL, and each gene was altered in less than 2% of patients. Collectively, infrequently altered genes are present in approximately half of ALL patients and converge on several key biological pathways not previously associated with ALL, including protein modification, RNA machinery and the cohesin complex, which were collectively altered in 8, 14, and 8% of cases respectively. Thus, multiple genomic scenarios contribute to the development of ALL. Indeed, the enrichment of genes and the identification of unique gene combinations that exists across ALL subtypes highlights the wide diversity in disease mechanisms across subtypes and will guide the development of experimental models that faithfully recapitulate human disease.

Methods

Patients and clinical specimens

The study complies with all ethical regulations and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the Children’s Oncology Group. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient, parents or guardians. Subjects were not compensated for participation. We studied 2754 children, adolescents and young adults (AYA) with newly diagnosed B-ALL (n=2288) or T-ALL (n=466) enrolled-on St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St. Jude, n=899) and Children’s Oncology Group (COG, n=1855) protocols, including St. Jude Total XV65 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT00137111), St. Jude Total XVI66 (NCT00549848), COG P9906 high-risk B-ALL study67 (NCT00005603), COG AALL0232 NCI high-risk B-ALL study68 (NCT00075725), COG AALL1131 high-risk B-ALL study69 (NCT02883049), COG AALL0331 standard-risk B-ALL study70 (NCT00103285), COG AALL0932 standard-risk B-ALL study71 (NCT01190930), and COG AALL0434 T-ALL study72 (NCT00408005) (Extended data fig. 1, Supplementary table 1). Matched normal control DNA was derived from remission blood or bone marrow with negative or low (<5%) measurable residual disease by flow cytometry, or by purifying non-tumor cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Supplementary fig. 1).

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment. Genomic analysis was performed on distinct samples and the same sample was not measured repeatedly.

Transcriptome sequencing and statistical analyses

Details of transcriptome sequencing, gene expression evaluation from RNA-seq, B- and T-ALL subtyping and statistical analyses are provided in the Supplementary Note.

Somatic copy number alteration identification

For Illumina-based WGS data, we performed alignment with BWA version 0.5.9 (hg19), and identified somatic CNAs using CONSERTING version 1.0. For CGI (Complete Genomics Inc.)-based WGS data, we used CNA data from our previously published analysis which used an adaptation of CONSERTING to call CNAs24. Focal deletions in known or putative driver genes were identified as those that were shorter than 5 megabases (Mb) in length, and (in protein-coding genes) affected any exon in the gene of interest which contained a coding region or (in non-coding genes) affected any exon in the gene. However, for CDKN2A, PAX5, and IKZF1, focal deletions of 20 Mb or less were also considered alterations due to their well-established driver status. A log2 fold change of −0.15 or less was required to consider a gene focally deleted, except for in near haploid and low hypodiploid subtype samples, where a threshold of −1.0 or less (essentially homozygous deletions) was required. Focal deletions were only noted in genes considered likely to be tumor suppressors based on known function, preponderance of focal deletions, or preponderance of frameshift and nonsense mutations (Supplementary table 6).

Somatic structural variant identification

Somatic SVs were identified from Illumina-based WGS data aligned to hg19 using BWA version 0.5.9. SVs were called using four callers: CREST version 1.073, SvABA version 1.1.374, Manta version 1.6.075, and Delly version 0.8.2.76 SVs detected by two or more of these four callers were included in the final call set similar to analysis done in the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) structural variant study77. SVs were considered matching between two callers if both breakpoints were within 30 bases and had the same structural orientation. CREST calls were manually reviewed in the Bambino-based BamViewer to exclude spurious variants78, and selected likely driver alterations detected only by CREST were rescued and included in the final call set even if not detected by another caller, including rearrangements expected based on RNA-Seq-based transcriptional clustering or fusion detection, and deletions with breakpoints matching CNAs. SVs for CGI-based WGS data were obtained from our previous study in which SVs were identified using the CGI Cancer Sequencing service pipeline (version 2) and filtered to remove germline SVs24.

Somatic SNV and indel identification

Somatic SNVs and indels were identified from Illumina-based WGS and WES data with Bambino version 1.6 after alignment with BWA (hg19). Exonic variants were manually viewed in BamViewer78 and those with weak evidence upon visual inspection were removed from consideration. For previously published Illumina samples, the Bambino SNV and indel calls were used from the original study (see Supplementary tables 3–4). For CGI-based WGS data, SNVs and indels were used from our previous study, where we downloaded TARGET variant calls and used filters to remove likely artefactual variants24. SNVs and indels were annotated using VEP version 95.279. For 318 samples sequenced with both Illumina-based WGS and WES, SNVs detected in only one of these two platforms were subjected to a detailed check for mutant reads in the undetected platform using a custom script. After performing this analysis there was 95% concordance (overlapping variants / total variants) between the two platforms when analyzing somatic SNVs with at least 10 reads of coverage in both platforms. In samples with both WGS and WES, variants called with either platform (either WGS or WES) were included analysis.

Given 50x coverage (the median for WGS), there was 98.6% probability of detecting a variant with at least 3 mutant reads (the minimum required for de novo variant calling) given a true VAF of 15%. The probability decreased to 88.8% given a VAF of 10%, or 45.9% given a VAF of 5%. Given 72x coverage (the median for WES), these probabilities were 99.9% (for 15% VAF), 97.9% (10% VAF), and 70.5% (5% VAF).

Germline SNV and indel identification

Germline SNVs and indels were detected from WES data using Bambino version 1.6 after alignment with BWA (hg19). The impact of the variants on protein coding genes was annotated with ANNOVAR (version 2014-11-12)80 with multiple databases. The following criteria were applied to keep the potential pathogenic (P) and likely pathogenic (LP) variants: (1) germline SNVs had mutant variant allele fraction (VAF) of at least 0.2 to be considered; (2) variants had MAFs (minor allele frequencies) less than 0.001 in 1000 Genomes, EVS, and ExAC population allele frequency databases; (3) frameshift and splice indels were considered; (4) nonsense and splice SNVs were also considered; and (5) missense variants with a REVEL81 score >0.5 were considered. Variants meeting these criteria were then analyzed following American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines. Variants meeting ACMG guidelines for pathogenicity (P or LP) were considered germline predisposition variants (Supplementary table 24), and corroborated with ClinVar when possible.

SNV burden quantification

The SNV burden, as shown in Fig. 1, was quantified for all samples sequenced by WGS or WES. For samples sequenced by both WGS and WES, only the WGS SNVs were analyzed. All SNVs found in protein-coding genomic positions, whether synonymous (silent) or non-synonymous (including missense, nonsense, etc.) were analyzed. SNVs found in regions of genes not coding for proteins (such as introns, UTRs, etc.) were excluded. The total calculated length of protein-coding regions of the genome was 34,246,114 base pairs, based on the UCSC refGene.txt (hg19) transcript annotation file. The number of SNVs (which were found in these protein-coding regions) in each sample was divided by this number and multiplied by 106 to obtain the number of SNVs per Mb in the sample.

Identification of significantly mutated or altered genes

To identify significant somatic mutated or altered genes, we used MutSigCV version 1.4 (SNVs and indels as input)20, GRIN (SNVs, indels, and CNA data; GRIN is not versioned currently)21, GISTIC version 2.0 (CNA data)22, SV outliers (SV input; genes where 5 or more samples had an SV breakpoint within the gene were checked for recurrent focal deletions), and MedalCeremony (version 1.0)23. MutSigCV was also run on B-ALL alone and T-ALL alone, in addition to the entire cohort. Genes with P < 0.05 and Q < 0.25 by MutSigCV or GRIN were considered putative driver genes. Manual inspection of SNV/indel mutations across each protein thus identified, using ProteinPaint82, was used to confirm significance, and genes were manually removed from consideration as putative drivers if their profile was inconsistent with likely oncogenic or tumor suppressor function (e.g. a profile including only diffuse, non-hotspot missense mutations). A few genes with recurrent hotspot SNVs/indels were considered putative driver alterations despite lack of statistical significance. Putative driver genes were considered to be not previously reported in cancer if not part of the Sanger Cancer Gene Census25, not reported as significantly mutated in our previous pan-cancer study24, and not reported as mutated in cancer based on our search of the literature. Genes reported in a non-ALL cancer type, but not in ALL, in the Sanger Cancer Gene Census, our previous pan-cancer study, or the literature were considered newly reported in ALL in this study.

Driver alteration identification and driver burden quantification

The driver alteration burden in Fig. 1 was calculated as follows, and only samples with SNV/indel and copy number characterisation (WGS or WES plus SNP copy array) were analyzed. Known driver genes, or putative driver genes identified from significantly mutated gene analysis (see Supplementary table 6 for full list), were considered altered in a sample if mutated in a way consistent with their oncogene or tumor suppressor status. Oncogenes required variants to be coding alterations including missense, splice site, and in-frame indels. Tumor suppressor genes allowed all of these variant types plus nonsense and frameshift variants, and focal deletions of 5 Mb or less. (These are also the criteria used to determine whether driver or putative driver genes were considered altered in other analyses in the study.) If the gene was altered more than once in the sample (such as biallelic alteration) it was only counted once in the driver gene burden. Canonical and likely driver fusions, detected by WGS, RNA-seq, or clinical methods, were counted as a single driver event. In ALL samples where a single driver rearrangement was expected (based on the subtype) but not detected due to lack of a platform able to detect it (for example, a DUX4 subtype sample with high DUX4 expression but no IGH-DUX4 detected due to lack of WGS), one driver rearrangement event was assumed in addition to the driver SNVs/indels or focal deletions actually detected.

In addition to driver SNVs/indels, focal deletions, and known fusions/rearrangements, selected genes were characterized for special variant types, including in FLT3 (enhancer-activating focal deletions similar to those reported previously83, termed “regulatory” in figures), and in PAG1 and TBL1XR1 (focal promoter deletions, grouped with “focal deletions” in figures). The above-mentioned FLT3 alterations were associated with increased FLT3 expression, while the above-mentioned PAG1 and TBL1XR1 alterations were associated with decreased expression, leading to these alterations being considered driver alterations.

Pathway analysis

Genes were manually assigned to various signaling and functional pathways as described in Supplementary table 14. If at least one gene in the pathway was somatically altered (with an alteration matching the gene’s putative oncogene or tumor suppressor status, where missense and splice-site SNVs and in-frame indels were considered drivers for oncogenes, while for tumor suppressors missense, splice-site, in-frame indels, nonsense, frameshift, and focal deletions (of 5 Mb or less) were considered driver alterations as per Supplementary table 6; fusions and rearrangements were not considered), the pathway was considered altered in that sample. Overall survival, event-free survival, and subtype enrichment for each pathway were then compared as done for individual genes, comparing pathway-positive vs. pathway-negative samples. The transcription and epigenetic pathways excluded genes mutated in less than 2% of B-ALL and in less than 2% of T-ALL due to the large number of genes included in these pathways.

Mutational signature analysis

Genome-wide SNVs from WGS samples were identified as described above; variants in repetitive genomic regions were excluded. Each variant’s trinucleotide context was determined using an in-house script (hg19 reference genome) to obtain the 96-channel profile for each sample84. The presence and strength of the COSMIC version 3.0 mutational signatures in each sample was determined using MATLAB-based SigProfilerSingleSample (version 1.3)27 using the COSMIC signature set included in that software version and default parameters, plus previously unreported signatures we recently discovered85. COSMIC signature 7 levels noted in the text and figures refer to the sum of signatures 7a, 7b, 7c, and 7d. African vs. non-African descent was determined for hyperdiploid, iAMP21, and near haploid B-ALL samples with Illumina WGS based on (when available) self-reported race, or (when unavailable) principal component analysis clustering of germline SNPs (detected by WGS) informed by the cases with known self-reported race.

Timing of copy number alterations in aneuploid subtypes

WGS samples belong to hyperdiploid and iAMP21 B-ALL subtypes were analyzed. Integer copy number states of each CONSERTING-identified copy number segment was first performed in order to identify SNVs in 3-copy regions. Copy number data were manually centered at the diploid center peak if needed, based on allelic imbalance and copy number information. 1- and 3-copy states were then identified using allelic imbalance and copy number information, and to correct for tumor purity, the linear (non-log) copy number data were multiplied around the 2-axis (diploid state) to align apparent 1- and 3-copy states in impure samples with actual 1- and 3-copy numerical values. SNVs in 3-copy regions were those with a linear (not log) copy number of 2.5 to 3.49.

For comparing the UV signature between variants on 1/3 or 2/3 copies, mutations were considered to be on 1/3 copies if below VAF 0.5 (adjusted for tumor purity) or 2/3 copies if above 0.5. Variants were pooled within all hyperdiploid or all iAMP21 samples, followed by mutational signature analysis to determine the presence or absence of the UV signature on 1/3 or 2/3 copies.

For determining whether hyperdiploid copy gains occurred synchronously or asynchronously, each 3-copy chromosome with at least 20 SNVs was analyzed using WGS. Only samples with two or more such chromosomes were analyzed. The somatic SNV VAFs, adjusted for tumor purity, were analyzed for each 3-copy chromosome, and samples where all chromosomes had a similar ratio of 1/3 (VAF 0.33) vs. 2/3 (VAF 0.67) SNVs in 3-copy regions were considered to have synchronous copy gains. Samples where the ratio was different for different chromosomes were considered to have asynchronous copy gains.

Cancer cell fraction calculation

Cancer cell fractions (CCFs) were determined for driver or putative driver gene SNVs and indels in 2-copy regions for most subtypes. The CCF for these was as follows, where p indicates tumor purity:

| (1) |

In near haploid and low hypodiploid samples, variants in 1-copy regions were used. The proportion of tumor reads (t) in the sample was defined as (only for 1-copy region variants):

| (2) |

The 2(1-p) indicates the normal cell (diploid) read contribution. The CCF was then defined as (only for 1-copy region variants):

| (3) |

Single-cell DNA sequencing and protein analysis

Single-cell amplicon-based DNA and protein sequencing was performed on six ALL samples using the Tapestri (version 2) platform (MissionBio), and the ALL amplicon panel, which analyzes common mutations in 305 genomic regions within 112 ALL driver genes86. Ten TotalSeq oligo-conjugated antibodies from Biolegend were used for cell-surface protein analysis: D0048 anti-human CD45, D0054 anti-human CD34, D0066 anti-human CD7, D0063 anti-human CD45RA, D0062 anti-human CD10, D0050 anti-human CD19, D0389 anti-human CD38, D0052 anti-human CD33, D0034 anti-human CD3 and D0138 anti-human CD5. Cryopreserved mononuclear cells were thawed, deprived of dead cells by using the Dead Cell Removal Kit (Miltenyi Biotech, #130-090-101), resuspended in Cell Staining Buffer (BioLegend, 420201) (CSB), counted by a Countess II Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher) and diluted to have 25,000 cells/μL using CSB in a minimum volume of 40 μL. Cell suspension was processed according to the Tapestri Single-Cell DNA + Protein Sequencing User Guide. Briefly, cells were incubated with TruStain FcX and Blocking Buffer (Mission Bio) for 15 minutes (min) on ice. The pool of 10 oligo-conjugated antibodies described above was then added and incubated for 30 min on ice. Cells were then washed multiple times with pre-chilled CSB, counted to have a cell suspension of 3,000 – 4,000 cells/μL and loaded on a Tapestri microfluidics cartridge. Single cells were encapsulated with Lysis Buffer and Protease (Mission Bio) to create a cell emulsion and barcoded. DNA PCR products were then isolated from individual droplets, purified with Ampure XP beads (Beckam Coulter) and used for library generation. The supernatant from the Ampure XP bead incubation above contained the protein PCR products and it was incubated with biotin oligo (5 μM, Mission Bio) at 96 °C for 5 min followed by incubation on ice for 5 min. Protein PCR products were then purified using Steptavidin beads (Mission Bio) and used for library preparation. All libraries, both DNA and protein, were purified by Ampure XP beads, quantified and pooled for sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq.

The resulting fastq files for single-cell DNA and protein libraries were analyzed through the Tapestri pipeline in the Tapestri Portal. This pipeline trims adapter sequences, detects barcodes, aligns reads to the human genome (hg19), assigns sequence reads to cell barcodes, and performs mutation identification using GATK. For each single cell, mutation VAFs were calculated from GATK mutation calls for each expected driver variant which was originally detected by bulk sequencing, plus additional driver variants detected de novo from single-cell sequencing. Only cells with at least 10 reads of coverage at all of the expected driver mutation sites were analyzed, and a positive mutation call required at least 2 mutant reads and a VAF of 10% or more. In two patients, important driver variants were missed by GATK but were found in the single-cell DNA sequencing bam files. Therefore, in these patients, the GATK mutation counts were not used, but instead a custom script was used to obtain mutant and total read coverage at each driver mutation site from each single cell’s bam file. For single-cell protein analysis, in each cell the percent of protein-associated sequencing reads assigned to each of the 10 proteins was calculated as a measure of that protein’s level.

Data availability

Genomic data is publicly available and data accessions for RNA-seq, WES, WGS and SNP are listed for each case in Supplementary table 1. TARGET ALL data may be accessed through the TARGET website at https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/target/data-matrix. The TARGET BAM and FASTQ sequence files are accessible through the database of genotypes and phenotypes (dbGaP; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000218.v24.p8) under accession number phs000218 (TARGET) and at NCI’s Genomic Data Commons http://gdc.cancer.gov_under project TARGET. The remaining (non-TARGET) data has been deposited in the European Genome Phenome Archive, accessions EGAS00001000447, EGAS00001000654, EGAS00001001923, EGAS00001001952, EGAS00001002217, EGAS00001003266, EGAS00001004810, EGAS00001004998, EGAS00001005084 and EGAS00001005250 and is also accessible through St. Jude Cloud at https://platform.stjude.cloud/data/cohorts?dataset_accession=SJC-DS-1009. All raw sequencing data is available under controlled access for protection of germline information and to ensure appropriate data usage, and approval can be obtained by applying through the dbGaP portal (for TARGET datasets) or by contacting the PCGP steering committee (PCGP_data_request@stjude.org) for non-TARGET (EGA-deposited) datasets. Somatic mutation data can also be explored interactively using ProteinPaint82 and GenomePaint87 on St. Jude Cloud at https://viz.stjude.cloud/mullighan-lab/collection/the-genomic-landscape-of-pediatric-acute-lymphoblastic-leukemia~15.

Code availability

This study did not involve the development of custom code.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Overview of ALL cohort.

(a) Number of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients studied (n=2754), the different modalities of sequencing performed, and the genomic alterations identified by each. (b) Venn diagram of samples analysed by transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq), whole exome sequencing (WES), whole genome sequencing (WGS) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiling across the whole cohort (Pan ALL; left), in B-ALL only (middle) and in T-ALL only. (c) Distribution of patients according to lineage (left), sex (middle left), NCI standard-risk (SR), age 1 to 9.99 yrs and WBC < 50,000/μl; high-risk (HR), age 10 to 15.9 yrs and/or WBC ≥ 50,000/μl; adolescent and young adult (AYA; middle right) and age at diagnosis (right).

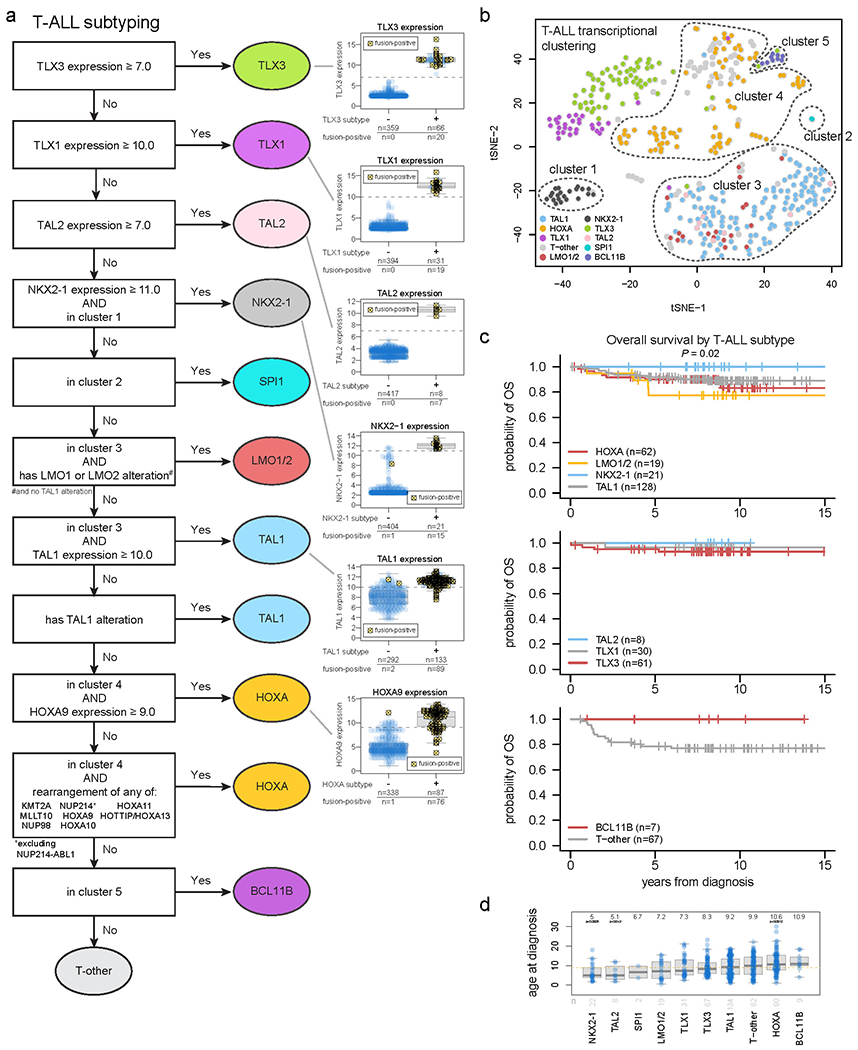

Extended Data Fig. 2. Subtype classification of B-ALL.

(a) Flow chart for B-ALL subtype classification; for detailed description of criteria, see Supplementary Methods. (b) Left, tSNE of B-ALL cases with RNA-seq. Right, copy number heatmap of B-ALL samples as determined by WGS or SNP copy array (n=1,630 samples), with subtype indicated by color at top. (c) Kaplan-Meier survival curves with overall survival distributions for each B-ALL subtype. Subtypes are separated into five graphs for ease of visualizing the various subtypes. Subtypes with at least 5 samples are shown. P value shown is by two-sided log-rank test comparing all subtypes shown in all five graphs. (d) Age at diagnosis by B-ALL subtype. Boxplot shows median (thick center line) and interquartile range (box). Whiskers are described in R boxplot documentation (a 1.5*interquartile range rule is used). Text at top shows median age in the subtype. P values compare ages from the subtype vs. all other B-ALL samples by Wilcoxon rank-sum test; P values ≤ 0.05 are shown. Numbers of patients are shown at bottom, and yellow line indicates median age across B-ALL.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Subtype classification of T-ALL.

(a) Flow chart for T-ALL subtype classification and inclusion in clusters 1-4 as drawn on the tSNE plot. Classification begins at the top and samples meeting the indicated criteria are assigned to subtypes shown at right. Boxplots to the right show the expression of these genes in samples assigned to the indicated subtype (+) or not assigned (−). Samples bearing a detected fusion or rearrangement defining the subtype are marked with yellow circles with X marks. The gene expression thresholds indicated at left were determined based on the expression levels in fusion-positive samples. Samples where gene expression was above these thresholds but no fusion was detected were assumed to likely have a fusion and were thus assigned to that subtype, since the fusion may have been undetected due to technical issues (e.g. TLX3 enhancer hijacking rearrangements may be hard to detect with RNA-seq since they do not always create fusion transcripts). Boxplots show median (thick center line) and interquartile range (box). Whiskers are described in R boxplot documentation (a 1.5*interquartile range rule is used). (b) tSNE of T-ALL cases with RNA-seq. (c) Kaplan-Meier survival curves with overall survival distributions for each T-ALL subtype, shown in three graphs for ease of visualization. Subtypes with at least 5 samples are shown. P value shown is by two-sided log-rank test comparing all subtypes shown in all graphs. (d) Age at diagnosis by T-ALL subtype. Boxplot shows median (thick center line) and interquartile range (box). Whiskers are described in R boxplot documentation (a 1.5*interquartile range rule is used). Text at top shows median age in the subtype. P values compare ages from the subtype vs. all other T-ALL samples by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test; P values ≤ 0.05 are shown. Numbers of patients are shown at bottom, and yellow line indicates median age across T-ALL.

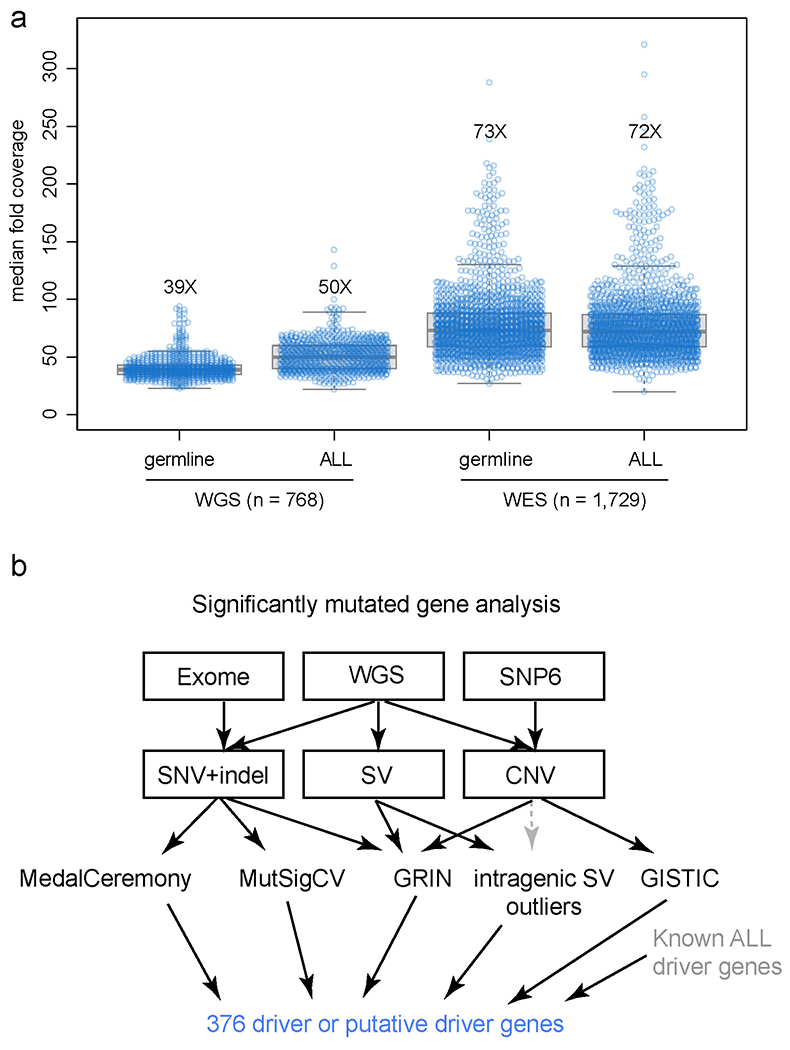

Extended Data Fig. 4. Sequencing coverage and identification of significantly mutated genes.

(a) Each sample’s median sequencing coverage based on WGS (n=768) or WES (n=1,729) is shown, including both germline and cancer (ALL) samples for each patient. Boxplot shows median (thick center line) and interquartile range (box). Whiskers are described in R boxplot documentation (a 1.5*interquartile range rule is used). The median coverage across all samples is indicated by text (e.g. “39X”). For WGS, the genome-wide coverage for each sample is indicated by each point. For WES, the median coverage in all protein-coding regions of exons (excluding 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions), as defined by the UCSC refGene.txt file, is shown. (b) Approach for identification of significantly mutated genes. The sequencing platform is shown on top, followed by the variant types detected by each platform below, and the third layer shows the tools used to identify significantly altered genes, with arrows indicating the variant types used as input to these tools. Intragenic SV outliers were identified initially by frequent SVs within the gene, and were corroborated manually with copy number analysis (dotted gray line) as the SVs were usually at the boundaries of focal deletions. All significantly mutated genes’ focal deletion and SNV/indel mutation site localization were manually inspected and those considered unlikely drivers were excluded. When combining the significantly mutated genes thus identified with the list of known drivers in ALL, a list of 376 driver or putative driver genes was identified.

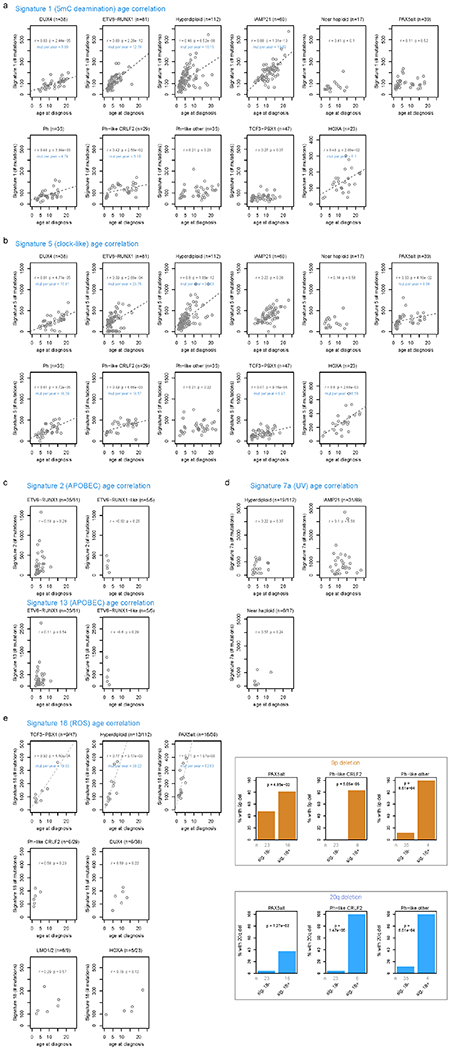

Extended Data Fig. 5. Correlation of COSMIC signatures with age and genetic alterations.

For each B-ALL and T-ALL subtype, the correlation between signature abundance (in number of SNVs, y-axis) and the age at diagnosis (x-axis) is shown. This includes samples sequenced by WGS which had mutational signature cosine similarities (comparing the sample profile vs. the profile as reconstructed by signatures) of 0.85 or above, and which also had available age information. Only subtypes with at least 5 samples meeting these criteria are shown, and the number of samples in each subtype are shown above each plot. Two-sided Pearson r correlation was performed to obtain the P and r values shown for each subtype. For subtypes with P < 0.05, linear regression was performed resulting in the linear fits shown, along with text indicating the slope of the line in mutations per year. (a) Signature 1 (5mC deamination). (b) Signature 5 (clock-like). (c) Signatures 2 and 13 (APOBEC). (d) Signature 7 (UV). (e) Signature 18 (ROS; left). Somatic alterations significantly correlating with signature 18 (right). Each somatic alteration (chromosome-level copy alterations and driver/putative driver genes) was tested for correlation with the presence vs. absence of signature 18, and 20q deletion and 9p deletion were significantly associated with signature 18 in the subtypes shown. P values are by two-sided Fisher’s exact test, and the number of samples in each group are shown below (n). Only WGS samples were analyzed.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Copy gain schemes in each hyperdiploid sample.

Each hyperdiploid sample sequenced by WGS is shown. This analysis tests whether copy gains likely occurred simultaneously or sequentially and is an expanded version of the examples shown in Fig. 2d, showing all 72 samples. Only 3-copy chromosomes with at least 20 somatic SNVs in the sample were analyzed, and only samples with two or chromosomes meeting this criterion were analyzed. On density plots, x-axes show VAF adjusted for tumor purity, and y-axes show each 3-copy whole-chromosome or arm gain in the sample. Vertical ticks on x-axis show individual SNV VAFs; an abundance of VAFs around 0.67 indicates late copy gains since the SNVs occurred prior to the copy gains (2 of 3 copies), while a preponderance of VAFs around 0.33 indicates early copy gains since most SNVs occurred after the copy gains (1 of 3 copies). Blue indicates an inferred early copy gain and red a late copy gain. (a) Samples falling into the asynchronous with late arm gain scheme, where most copy gains occur early with one chromosome arm gain occurring later. (b) Samples falling into the asynchronous with whole-chromosome gain scheme, where most copy gains occur early with one whole-chromosome gain occurring later. (c) Lone sample belonging to the synchronous late gain scheme, where all copy gains appear to occur simultaneously and occur late, after substantial point mutations have had time to accumulate (thus present on 2 of 3 copies). (d) Samples belonging to the synchronous early gain scheme, where all copy gains appear to occur simultaneously and occur early, before substantial point mutations have had time to accumulate (SNVs are present on 1 of 3 copies).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Genetic alterations affecting histone genes on chromosome 6p22.2 and 6p22.1.

(a) Prevalence of genetic alterations affecting any of the histones on 6p22.2 (top) or 6p22.1 (bottom) in each ALL subtype. Y-axis indicates the percentage of samples affected in each subtype, and the exact number of samples altered along with the number of samples analyzed in each subtype is shown above each plot. Samples with characterisation of both SNVs/indels and copy number alterations (through WGS or WES combined with SNP array) were analyzed. Alteration types are indicated by color (see legend at top right) and exclude fusions. If a sample had an alteration in more than one histone or more than one alteration type, only one alteration at the highest rank in the legend of alterations (e.g. “nonsense” has top priority) was shown. (b) Focal deletions (5 Mb or less; blue indicates degree of copy loss in each sample (row) and circles indicate SVs which were available for WGS samples only) at 6p22.2 (left) or 6p22.1 (right) affecting at least one histone in either region. Color at left indicates the subtype and lineage (B-ALL or T-ALL) as indicated by legend at bottom. (c) Sites of non-silent SNVs and indels in histones on 6p22 which were recurrently altered. Protein domains are indicated in color. (d) Somatic structural variant (SV) burden in patients with or without (WT) deletion of one or more histones on 6p22.2 or 6p22.1 or other SNV/indel alterations in histone genes such as those in (c). Only patients with Illumina WGS data were analyzed, and only ALL subtypes with at least 3 histone-altered samples are shown. P values are by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Boxplots show median (thick center line) and interquartile range (box). Whiskers are described in R boxplot documentation (a 1.5*interquartile range rule is used).

Extended Data Fig. 8. Clonality of driver SNVs and indels in B-ALL and T-ALL.

(a-b) The cancer cell fraction (CCF, x-axis), i.e. the percentage of cancer cells harboring each mutation, of alterations in each driver or putative driver gene is shown in (a) all B-ALL samples or the indicated B-ALL subtype, or (b) all T-ALL samples or the indicated T-ALL subtype. The CCF was calculated based on the VAF, copy number, and tumor purity of each sample; calculated CCFs above 1.0 were considered 1.0. Samples with both SNV/indel and copy number characterisation are shown. For subtype-specific plots, only subtypes with at least 20 samples meeting this criterion are shown. Each plot shows the number of samples analyzed (n) at top. For most samples, only SNVs/indels in 2-copy regions were analyzed, except for near haploid and low hypodiploid where only SNVs/indels in 1-copy regions were analyzed. SNVs are shown in blue and indels in red; each point represents one somatic mutation. Boxplots show median (thick center line) and interquartile range (box). Whiskers are described in R boxplot documentation (a 1.5*interquartile range rule is used). Known or putative driver genes with at least 10 SNVs/indels in 2-copy regions across all B-ALL samples, or 8 SNVs/indels in 2-copy regions across all T-ALL samples, are shown. (c-d) Targeted single-cell DNA sequencing plus protein analysis of two B-ALL samples (c) and one T-ALL sample (d). For each patient, a heatmap is shown with each row representing one cell, and each column representing either one mutation (left side) or one protein (right side). Mutation VAF is indicated by blue color, while protein level (as a percent of all protein-associated reads detected in the cell) is indicated by red color. At bottom of heatmap likely normal cells are indicated. The bulk VAF of each mutation is indicated below, along with bulk CCF (if copy number was available).

Extended Data Fig. 9. Alterations in rarely mutated genes affecting gene expression.