Abstract

According to the literature, treatment of HCV and HBV infections faces challenges due to problems such as the emergence of drug-resistant mutants, the high cost of treatment, and the side effects of current antiviral therapy. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), a group of small peptides, are a part of the immune system and are considered as an alternative treatment for microbial infections. These peptides are water-soluble with amphiphilic (hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces) characteristics. AMPs are produced by a wide range of organisms including both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. The antiviral mechanisms of AMPs include inhibiting virus entry, inhibiting intracellular virus replication, inhibiting intracellular viral packaging, and inducing immune responses. In addition, AMPs are a new generation of antiviral biomolecules that have very low toxicity for human host cells, particularly liver cell lines. AMPs can be considered as one of the most important strategies for developing new adjuvant drugs in the treatment of HBV and HCV infections. In the present study, several groups of AMPs (with a net positive charge) such as Human cathelicidin, Claudin-1, Defensins, Hepcidin, Lactoferrin, Casein, Plectasin, Micrococcin P1, Scorpion venom, and Synthetic peptides were reviewed with antiviral properties against HBV and HCV.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptides, HBV infection, HCV infection, Treatment

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are considered as two main causes of human viral hepatitis that their primary infections can lead to acute as well as chronic hepatitis; in general, their clinical outcomes include hepatitis, hepatic steatosis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma [1, 2]. The HBV virion is one of the members of the Hepadnaviridae family (with ten genotypes) and contains double-stranded DNA, capsid, and outer lipid envelope [3, 4]. According to the reports, it is estimated that about 400 million people are infected with HBV worldwide, and approximately one million die each year [5, 6]. Despite the widespread use of antiviral drugs and vaccination programs, the eradication of HBV infection is still challenging; various factors such as coinfection, the emergence of drug-resistant strains, drug side effects, and host conditions all affect treatment outcomes and lead to the reduction of sustained viral response (SVR) rate [7, 8]. In the other hand, the statistics of HCV infection are worrying; according to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, close to 200 million people are chronically infected with this virus, and most of them suffer from life-threatening diseases such as hepatocellular carcinoma, liver cirrhosis, as well as extra-hepatic disorders including cryoglobulinemia and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma [9–12]. HCV is an enveloped positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus with six genotypes, and belongs to the Flaviviridae family [13]. To date, no vaccine has been recommended for HCV, and the treatment protocol for patients infected with this virus is limited to pegylated interferon alpha plus ribavirin or direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy [14]. However, it should be borne in mind that antiviral drugs are toxic for human, and also problems such as the emergence of mutant strains, metabolic syndromes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may lead to unsuccessful treatment [15–18]. Hence, the use of new-generation therapies e.g. antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) is considered as an alternative strategy to reduce the mortality and morbidity of viral hepatitis infections. A wide range of organisms including bacteria, fungi, animals, plants, and mammals are able to produce AMPs [19]. AMPs, or host defense peptides (HDPs), are small positively charged peptides that are naturally secreted by a wide range of eukaryotic organisms, and as part of the innate immune system protect the host against a variety of pathogens [20, 21]. In general, AMPs are small α-helical cationic peptides with amphiphilic (both hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces) characteristics that serve several purposes including wound healing, angiogenesis, anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiparasitic, and antifungal responses [22, 23]. Among these, one of the greatest benefits of AMPs is antibacterial activity, which eliminates drug-resistant pathogens without damaging host cells [24]. Amphipathic helical peptides, cecropins and magainins are two most useful examples of AMPs that have been used in treating microbial infections since the early 1980s; todays, 17 new AMPs have been introduced in human clinical trials [22, 25, 26]. Recently, AMPs are considered as one of the best strategies to treat the cancer tissues; due to high metabolism in cancer cells, the membrane of these cells are more sensitive to AMPs than normal cells [27]. Different physiological roles can be considered for AMPs such as cell membrane perforation (bacterial membrane), binding to envelop of viruses, disruption the normal physiological functions (DNA replication, RNA transcription, and protein synthesis), induction of apoptosis, and interaction with intracellular signaling pathways [28, 29]. To date, various studies have been performed on the efficacy and mechanism of action of these peptides against HBV and HCV infections. In the present study, our aim was to review the common features of their antiviral activities against these viruses.

Well-known AMPs against HCV or HBV

Human cathelicidin LL-37

Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) is one of the natural human AMPs that is cleaved to LL-37 by proteinase 3 [30]. LL-37 (LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES) is a human α-helical peptide with 4.4 kDa molecular weight [31]. According to the literature, in addition to antimicrobial activity, LL-37 also has properties such as immunomodulatory function, wound healing, angiogenesis, chemotaxis, and high-affinity binding to bacterial LPS [32–36]. Although the main function of LL-37 is to attack bacterial membranes, however, today, evidence suggests that this peptide affects the regulation of host immunity. Furthermore, due to the low negative surface charge, the host cells are protected from its toxic effects [37, 38]. There are many studies on the antimicrobial activity of this peptide against bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus group A & B, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Candida albicans, and Acinetobacter baumannii [31]. Iacob et al. first assessed the plasma levels of cathelicidin LL-37 in patients with chronic HCV infection; using ELISA method, they found that the plasma levels of LL-37 was significantly higher in inactive HCV patients than patients with active infection or control group [39]. In addition, in their study, Matsumura et al. showed that LL-37 significantly had reduced both extracellular HCV core Ag levels of HuH-7 cell lines and infectivity titers of virus particles [40]. Studies have shown that vitamin D triggers the production of LL-37 in keratinocytes; therefore, in recent years, standard interferon-based therapy with vitamin D supplementation has attracted much attention [39, 40]. In another study, Puig-Basagoiti, et al. understood that LL-37 considerably reduced the formation of infectious HCV particles in BE-KO cell lines; they found that non-hepatic 293T cell lines expressing LL-37, claudin 1, and miR-122, completely hampered the propagation of HCV [41].

Antiviral mechanism of cathelicidin LL-37

Based on studies, plasma concentration of LL-37 is higher in HCV- and HBV-infected patients than uninfected individuals [42]. It seems that both calcitriol and cathelicidin inhibit HCV replication by inducing vitamin D receptor target genes [43].

Human Claudin-1

Human claudins are a diverse group of proteins that play a key role in forming tight junction between cells and determining epithelial cell permeability [44]. The claudin-1 (CLDN1) is a protein (211 amino acids) with a molecular weight of 22.7 kDa that is highly expressed in hepatocytes [45]. Claudin-1 acts as a co-receptor and is essential in entry of HCV into the human hepatocytes [46]. Si et al. showed that CL58 (CLDN1-derived peptide) could inhibit the intracellular life of HCV. According to their results, CL58 (MANAGLQLLGFILAFLGW) had a high binding affinity for HCV envelope, and even at concentrations close to 100-fold of the antiviral dose was not toxic for host cells [47].

Defensins

Defensins are a family of small cationic cysteine rich AMPs that are produced by both immune and epithelial cells in response to infectious agents [48]. Defensins are divided in three subclasses, α, β, and θ; α and β defensins are encoded by 6 and 31 genes respectively, and potentially act against viruses such as herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), vesicular stomatitis virus (VAV), adenovirus, influenza virus, human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1), and Sendai virus [49–53]. Furthermore, these AMPs are produced in a wide range of animals, insects, and plants to protect them against various pathogens [54–56]. In a research study, Mattar et al. demonstrated that defensins are able to stimulate TH1-dependent immune responses versus HCV infection, so that total serum defensin titers are about 2-10-fold higher in HCV-infected patients than in healthy individuals [57]. Studies show that these AMPs also induce high level of IL-2 following HCV infection; in a study by Owusu et al., it was showed that defensins such as human alpha defensin 1 (HAD-1) and human beta defensin 1 (HBD-1) could significantly induce high-level production of Th1 cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α) in patients with acute HCV infection [58]. In a study conducted by Aceti et al., it was concluded that the serum levels of α-defensin was higher in HCV- and HBV-infected patients than normal subjects, indicating a linear correlation between this peptide and advanced fibrosis [59]. It seems that α-defensin via stimulating nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) proteins intensifies the immune response, leading to the destruction of fibroblasts and matrix extracellular; hence, it is considered as a biomarker for the prediction of advanced fibrosis in HCV-infected patients [59, 60]. According to a study by Ling et al., it was revealed that the treatment of patients with interferon and ribavirin leads to the upregulation of β-defensin 1 gene, which in turn enhances the expression of both E-cadherin and hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HRS) genes; therefore, adjuvant therapy with β-defensin 1 plays a potential therapeutic role in preventing HCV infection and liver cancer development [61]. According to a study fulfilled at the Harbin Institute of Veterinary Research, China, antiviral activity of three novel Anas platyrhynchos avian β-defensins (Apl_AvBDs) against duck hepatitis virus (DHV) was investigated by Ma et al.; they showed that all three AvBDs (Apl_AvBD4, 7 and 12) strongly reduced the DHV viral load in ducks [62]. Scorpion defensins are another group of defensins which inhibit the replication of HBV and HCV.

Antiviral mechanism of defensins

Studies show that α-defensins induce the secretion of interleukin (IL-8) and IL-1 in airway epithelial and primary bronchial cells [63]. Since protein kinase C (PKC) acts as a receptor for HCV entry, α-defensins inhibit PKC by direct binding to this receptor, which in turn leads to inhibition of viral entry [64]. According to in vitro and in vivo studies, BmKDfsin3 inhibits HCV replication through its antiviral activities such as inhibiting IRAK-1/4 kinase function, and suppressing p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, while BmKDfsin4 inhibits HBV replication through mechanisms such as blocking Kv1.3 potassium channels, activating MAPK pathway, and down-regulating HNF4α [65, 66].

Human hepcidin

Hepcidin is a short peptide containing 25 amino acids produced by liver cells and is seems to be the main regulator of iron homeostasis; due to its antibacterial and antifungal activities, hepcidin is also called liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide-1 (LEAP-1) [67, 68]. According to the literature, serum hepcidin levels in patients infected with HCV and HBV are lower than in healthy individuals [69–71]. Overload iron in the liver infected with hepatitis viruses leads to a reduced response to antiviral therapy and ultimately progression to advanced fibrosis as well as hepatocellular carcinoma; a possible mechanism for suppressing hepcidin expression in HCV-infected cells is histone acetylation [72–75]. To confirm this hypothesis, studies show that serum hepcidin levels are significantly increased in HCV-infected patients receiving direct-acting antiviral agents (e.g. pegylated interferon plus ribavirin) [76, 77]. From a molecular perspective, hepcidin appears to play a pivotal role in preventing advanced fibrosis and liver cancer by inducing STAT3 pathway (the inhibitory effect of hepcidin on intracellular proliferation of HCV in Huh7 hepatocytes) during antiviral therapy [75, 78, 79]. Based on the available evidence, intracellular HCV replication induces oxidative stress, which in turn suppresses hepcidin expression. This condition leads to increased liver iron stores, over-proliferation of the virus, and ultimately decreased response to treatment.

Antiviral mechanism of hepcidin

Hepcidin stimulates host immune responses through mechanisms such as inhibiting iron accumulation, inducing signal transducer, and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway to enhance the therapeutic and clearance effects of viral hepatitis [78–81]. During the viral infection, both excess intracellular iron (in HCV infection) and inflammation trigger the up-regulation of hepcidin [82]. Under chronic infection, inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6, play a central role in hepcidin production. Following the binding of this interleukin to its receptor, phosphorylation of STAT-3 is initiated; in the nucleus phosphorylated STAT3 interacts with hepcidin promoter to up-regulate hepcidin expression [83].

Lactoferrin

Lactoferrin (LF) is a multifunctional biomolecule (703-amino acid residues) in the innate immune-system that acts as a broad-spectrum AMP against many of microorganisms [84, 85]. Previous studies have shown the antiviral activity of LF against HBV, HCV, HSV, CMV, HIV and adenovirus [86–90]. This protein consists of two domains (each domain contains 345 amino acids residues) with a hinge region, and its proposed defense mechanisms against HBV and HCV are inhibition of virus-host interaction and direct interaction with viral particle, respectively [86, 87, 91]. The C-terminal domain of camel LF prevents HCV entry into the Huh 7.5 cells, whereas its N-terminal domain twice as much inhibits the intracellular viral replication [87]. Studies conducted on PHCH8 cell lines have shown that preincubation of these cells with bovine LF (bLF) or human LF (hLF) can significantly prevent HBV infection, but none of bovine milk proteins such as transferrin, casein, and α-lactalbumin (α-La) have no anti-HBV activity [86].

Antiviral mechanism of LF

The binding of LF to glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), especially heparan sulfate (HS), competitively inhibits the contact between HBV or HCV and host cells [92, 93]. The envelope proteins E1 and E2 are the two main targets of HCV for LF, so that the interaction between these two proteins and LF leads to the inhibition of HCV binding to cell receptors [94]. An additional antiviral mechanism of LF is binding between LF and intracellular target of HCV, the non-structural 3 (NS3) protein; direct binding between LF and NS3 results in inhibition of HCV intracellular replication [95].

Camel milk casein

Traditional medicine is one of the most popular strategies for controlling infectious diseases in low-income populations. Camel milk consist three proteins with antimicrobial activities including lactoferrin, amylase, and IgG [96]. Studies show that although casein has no direct anti-HCV effect on infected cells, this protein along with α-La can induce apoptosis in HepG2 cell lines infected with HCV genotype 4a, leading to containment of intracellular life of the virus [97]. A possible protective mechanism for camel LF is based on direct interaction with HCV genotype 4 to prevent the virus from entering human leukocytes [98]. Interestingly, a study on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and hepG2 cells showed that following exposure of these cells to HCV, camel LF could efficiently prevent virus replication, but amylase could not [99].

Plectasin

Plectasin is a short peptide belonging to a group of fungal defensins that was first extracted from Pseudoplectania nigrella in 2005; recently, clinical trial studies have confirmed the effectiveness of this peptide in eradicating drug-resistance gram-positive bacteria [100, 101]. Functionally, plectasin is a HCV NS3-4 A serine protease inhibitor (IC50 value: 4.3µM and Km value: 20µM) that at 15 µM concentration can inhibit the replication of HCV in Huh-7 cell culture [102].

Antiviral mechanism of plectasin

HCV has a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome, which upon entrance into the cell is translated to a polyprotein of ~ 3,000 amino acids. An intracellular protease namely NS3-4 A serine protease is responsible for cleavage of this polyprotein as well as replication of virus in cell culture and chimpanzees; hence, as noted above plectasin acts as an inhibitor peptide against HCV NS3-4 A serine protease [102, 103].

Micrococcin P1

Micrococcin P1 is one of well-known peptides in thiopeptide family that first was extracted from Macrococcus caseolyticus [104]. This peptide has a wide range of antimicrobial activities, for example it restrains the formation of plastid-like organelle in Plasmodium falciparum [104–106]. The main mechanism of micrococcin P1 seems to be inhibition of protein synthesis [107]. Lee et al. first demonstrated that this peptide inhibits the intracellular entry of all HCV genotypes (EC50 range: 0.1–0.5µM), especially sofosbuvir-resistant variants, hence, combination of antiviral drugs with micrococcin P1 synergistically is used to treat HCV infection [108].

Scorpion venom

Among AMPs produced by insects, scorpion venom is a potential source of these peptides, which have antimicrobial activity [109]. Most scorpion venom peptides contain 20–75 amphipathic amino acids with a net positive charge, and are structurally divided into three groups including: (1) cysteine-rich repeats AMPs; (2) amphipathic α-helix AMPs without cysteine; (3) proline and glycine rich AMPs [110]. A study by El-Bitar et al. on five scorpion venoms such as Leiurus quinquestriatus, Androctonus amoreuxi, A. australis, A. bicolor, and Scorpio maurus palmatus showed that S. m. palmatus (IC50: 6.3 µg/ml− 1) and A. australis (IC50: 88.3 µg/ml− 1) had anti-HCV activity. According to their findings, these venoms were stable in the presence of metalloprotease inhibitors as well as at 60 °C, but prevented HCV infection only in culture medium and did not penetrate into cells [111]. In their study on Heterometrus petersii toxin, Yan et al. showed that Hp1090 peptide is an α-helical amphipathic peptide that reduces in vitro HCV infection due to direct interaction with the viral membrane (IC50: 7.62 µg/ml− 1) and prevents it from entering the cell [112].

Antiviral mechanism of scorpion venom

Scorpion venom peptides have antiviral activity against several viruses. Two histidine-rich peptides Ctry2459-H2 and Ctry2459-H3 can inhibit HCV infection by binding to viral articles and inactivating them [113, 114]. Another histidine-rich, Eval418 can suppress Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) by disrupting the initial steps of virus replication [115]. Mucroporin-M1 is other type of scorpion venom which is able to inhibit HBV replication by activating the MAPK pathway and downregulating the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4-alpha (HNF4α) in both in vitro and in vivo examinations [116].

Synthetic peptides

In recent years peptide drugs have been considered as one of the most important candidates for the development of new therapeutic drugs [117]. Peptide drugs are small synthetic molecules that have properties such as broad biological activity, high diversity, and rational design caacity [118–120]. However, disadvantages of these peptides include short half-life, fast cleavage by proteases, and clearance by reticuloendothelial system [121]. One of the main reasons for the use of peptide drugs may be rapid emergence of new viral variants [122]. For example, T-20 is a peptide with 36 amino acid residues that significantly inhibits HIV-1 membrane fusion process [123]. The emergence of T-20-resistant variants has reduced the effectiveness of this peptide; T-1249 is a newer peptide that is able to inhibit the T-20-resistant strains [124]. In recent decades, several peptide drugs such as C5A, amphiphilic eight-residue cyclic D,L-a-peptide, Ctry2459-H2, and Ctry2459-H3 have successfully passed in vitro examinations against HVC infection [113, 122, 125]. In addition, in recent years, the design of HBV envelope-derived peptides has revealed that the pre-S1 domain (e.g. pre-S1 mutants) plays a key role in the entry of HBV into cells [126–128]. Recent studies have shown that pre-S1-based peptides can inhibit HBV infection [129–131].

A review of current peptides

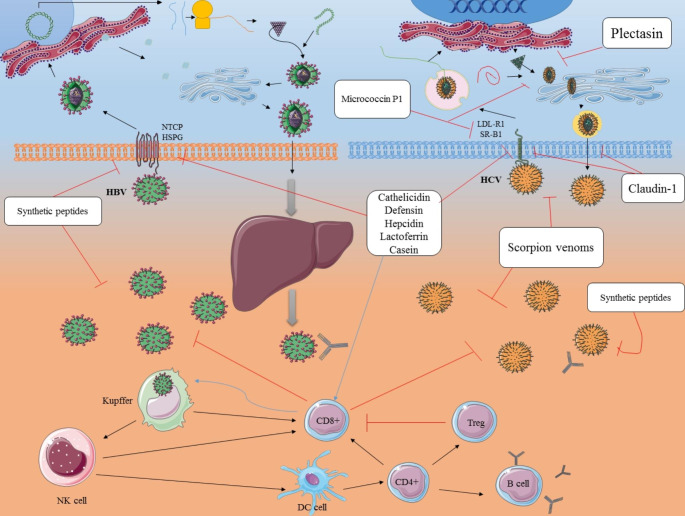

In the present study, we showed that antimicrobial peptides have a great ability to fight viral hepatitis infections (Fig. 1). To identify the common features of AMPs against HBV and HCV, their properties such as molecular weight, isoelectric pH, net charge, mechanism of action, and amino acid sequence are listed in Table 1. These peptides covered the molecular weight range of 1.4–36 kDa and there was no similar domain between them. However, their most important common properties included: (1) α-helical structure; (2) dominant net positive charge; (3) penetration into cell membrane and pore formation.

Fig. 1.

The main anti-HCV and HBV activity of the antimicrobial peptides according to in vitro studies

Table 1.

Characteristics of the antimicrobial peptides with their anti-hepatitis viral effect

| Peptides | Molecular weight | pH isoelectric | Net charge | Mechanism of action | Amino acids sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL-37 | 4493.32 | 10.61 | + 6 |

Inflammatory response, Pore formation |

LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES |

| CL-58 | 1935.36 | 5.28 | 0 | Blocking the entry of virus | MANAGLQLLGFILAFLGW |

| BmKDfsin4 | 1448.81 | 11.0 | + 2 | Inflammatory response, direct viral activity against HBV | FIGAIARLLSKIF |

| Apl AvBD4 | 7162.61 | 9.5 | + 8 | Inflammatory response, direct viral activity against HCV | MKILCFFIVLLFVAVHGAVGFSRSPRYHMQCGYRGTFCTPGKCPHGNAYLGLCRPKYSCCRWL |

| Hepcidin | 2797.41 | 8.22 | + 2 | Inflammatory response and hindering HCV replication | DTHFPICIFCCGCCHRSKCGMCCKT |

| Bovine lactoferrin (C-terminal) | 36901.71 | 6.36 | -2 | Inflammatory response, inhibition of intracellular replication | Accession number: Q6LBN7 |

| Casein | 15771.98 | 8.28 | + 1 | Inflammatory response, inhibition of intracellular life | Accession number: A0A077B3P4 |

| Plectasin | 4407.99 | 7.77 | + 1 | Anti-HCV protease | GFGCNGPWDEDDMQCHNHCKSIKGYKGGYCAKGGFVCKCY |

| Micrococcin P1 | 1144.37 | NA | 0 | Inhibition of HCV entry, blocking the translation | PubChem CID: 5,282,052 |

| Hp1090 | 7740.92 | 4.27 | -5 | Direct anti-HCV activity | MKTQFAIFLITLVLFQMFSQSDAIFKAIWSGIKSLFGKRGLSDLDDLDESFDGEVSQADIDFLKELMQ |

| cyclic D,L-a-peptide | 1063.18 | 6.0 | 0 | Blocking the entry HCV virus, direct anti-HCV activity | WLWSEQSK |

| Ctry2459-H2 | 1130.3 | 7.02 | 0 | Blocking the entry HCV virus, direct anti-HCV activity | FLGFLHHLF |

AMPs discovered against other viruses

AMPs also have clinical applications against other viruses. Based on studies, human α-defensin 5 (HAD5) reduces intracellular replication of human adenovirus (HAdV) by 95%, when cells are exposed to this peptide [132, 133]. On the other hand, human β-defensins (HBDs) such as HBD1, HBD2, and HBD3, and cathelicidin LL-37 have shown inhibitory effect against influenza A virus (IAV) infections [134, 135]. Human neutrophil peptides (HNPs) act as lectins; HNP1, HNP2 and HNP3 directly bind to gp120 of HIV and finally block the binding of this virus to the CD4 receptor of Th lymphocytes [136]. HNPs (HNP1, HNP2, HNP3, and HNP4) as well as HAD6 are able to inhibit the HSV infection through two mechanisms: (i) binding to virus glycoproteins; (ii) binding to heparan sulfate [137]. In a stud by Kota et al., they showed that cells pre-treated with HBD2 (4 µg/mL) can reduce respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) titers 100-fold following infection [138]. In a recent study by Alagarasu et al., they demonstrated that cathelicidin LL-37 could inhibit dengue virus 2 (DENV-2) infection in Vero cell culture [139]. Due to their low toxicity and high efficacy, both HNP1 and HAD5 peptides can be considered as safe candidates against human papilloma virus (HPV) infection [140].

Current hurdles in using AMPs

According to the data of this review, AMPs seem to be potentially effective in the treatment of infections caused by pathogenic microorganisms. However, there are several hurdles in using AMPs including: (1) the high cost of manufacturing of AMPs; (2) although AMPs show significant in vitro activity against microorganisms, their activity appears to be reduced under physiological host conditions (inactivation of β-defensins in high-salt cystic fibrosis bronchopulmonary fluids); (3) there are few studies on peptide-mediated toxicity, therefore, the potential toxicity of AMPs on human or animal cells needs to be understood in the future; (4) in general, synthetic AMPs are susceptible to mammalian protease, leading to short half-life of these peptides [141, 142]. Considering these problems, more studies are needed to evaluate the properties of natural or synthetic AMPs such as half-life, toxicity, effective dose in future examinations.

Concluding remarks

Based on the articles reviewed in this study, AMPs can be considered as a fundamental strategy for developing new treatment options against HBV and HCV infections. These small peptides block HCV and HBV viruses through safe molecular mechanisms and can boost the immune system in favor of infected cells. The inhibitory effect of AMPs on all pathogenic microorganisms is carried out by various mechanisms such as perforating the bacterial cell membrane, direct binding to envelop of viruses, direct biding to host cell receptors, disrupting normal physiological functions, inducing apoptosis, and interfering with intracellular signaling pathways. In addition, host cells are often resistant to the inhibitory effects of AMPs due to the presence of cholesterol in the cell membrane. However, there is no conclusive data on the clinical efficacy of these biological molecules for therapeutic purposes such as prevention of re-infection after liver transplantation, controlling relapse, and post-exposure prophylaxis. Also, there is limited information on the antiviral activity of AMPs against mutant viral strains. Therefore, more clinical trials in humans should be performed to confirm the therapeutic effect of AMPs in the treatment of HBV and HCV infections. Overall, due to the emergence of resistant microorganisms on the one hand, and the need to use better alternatives than conventional drugs on the other hand, AMPs can be considered as an appropriate option for the treatment of resistant pathogens in future. However, the clinical efficacy and safety of these peptides should be fully evaluated during in vitro examinations.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate from both Mashhad University of Medical Sciences and Jiroft University of Medical Sciences.

Authors’ Contributions

1. MK1 has contributed to design of the work and analysis of data. 2. HK has contributed to design of the work. 3. KGH has contributed to design of the work. 4. MK2 has drafted the work and substantively revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

We have not received any funding for this research.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable (this paper was provided based on researching in global databases).

Consent for publish

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

There is no any conflict of interest among the all authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cooke GS, Andrieux-Meyer I, Applegate TL, Atun R, Burry JR, Cheinquer H, et al. Accelerating the elimination of viral hepatitis: a Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology Commission. lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(2):135–84. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30270-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson PK, Mathers BM, Cowie B, Hagan H, Des Jarlais D, Horyniak D, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews. The Lancet. 2011;378(9791):571–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepard CW, Simard EP, Finelli L, Fiore AE, Bell BP. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28(1):112–25. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxj009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alavian SM, Hajarizadeh B, AHMADZADASL M, Kabir A. BAGHERI LK. Hepatitis B Virus infection in Iran: A systematic review. 2008.

- 5.Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(24):1733–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahon BJ, editor Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. Seminars in liver disease; 2005: Published in 2005 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue …. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Shaw T, Bartholomeusz A, Locarnini S. HBV drug resistance: mechanisms, detection and interpretation. J Hepatol. 2006;44(3):593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Block TM, Gish R, Guo H, Mehta A, Cuconati A, London WT, et al. Chronic hepatitis B: what should be the goal for new therapies? Antiviral Res. 2013;98(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao M, Nettles RE, Belema M, Snyder LB, Nguyen VN, Fridell RA, et al. Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature. 2010;465(7294):96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature08960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tasleem S, Sood GK. Hepatitis C associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: clinical features and the role of antiviral therapy. J Clin translational Hepatol. 2015;3(2):134. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2015.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabrizi F, Dixit V, Messa P. Antiviral therapy of symptomatic HCV-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia: meta‐analysis of clinical studies. J Med Virol. 2013;85(6):1019–27. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pol S, Vallet-Pichard A, Corouge M, Mallet VO, Hepatitis C. epidemiology, diagnosis, natural history and therapy. Hepatitis C in renal disease. Hemodial transplantation. 2012;176:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000332374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Ghaffar TY, Sira MM, El Naghi S. Hepatitis C genotype 4: The past, present, and future. World journal of hepatology. 2015;7(28):2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Feld J. Direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus (HCV): the progress continues. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18(7):851–62. doi: 10.2174/1389450116666150825111314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keikha M, Eslami M, Yousefi B, Ali-Hassanzadeh M, Kamali A, Yousefi M, et al. HCV genotypes and their determinative role in hepatitis C treatment. Virusdisease. 2020:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Thomas DL. Global control of hepatitis C: where challenge meets opportunity. Nat Med. 2013;19(7):850–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horner SM, Naggie S. Successes and challenges on the road to cure hepatitis C. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(6):e1004854. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar D, Farrell GC, Fung C, George J. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3 is cytopathic to hepatocytes: reversal of hepatic steatosis after sustained therapeutic response. Hepatology. 2002;36(5):1266–72. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenssen H, Hamill P, Hancock RE. Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(3):491–511. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00056-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Silva BR, de Freitas VAA, Nascimento-Neto LG, Carneiro VA, Arruda FVS, de Aguiar ASW, et al. Antimicrobial peptide control of pathogenic microorganisms of the oral cavity: a review of the literature. Peptides. 2012;36(2):315–21. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neshani A, Zare H, Akbari Eidgahi MR, Hooshyar Chichaklu A, Movaqar A, Ghazvini K. Review of antimicrobial peptides with anti-Helicobacter pylori activity. Helicobacter. 2019;24(1):e12555. doi: 10.1111/hel.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neshani A, Eidgahi MRA, Zare H, Ghazvini K. Extended-Spectrum antimicrobial activity of the Low cost produced Tilapia Piscidin 4 (TP4) marine antimicrobial peptide. J Res Med Dent Sci. 2018;6(5):327–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirski T, Niemcewicz M, Bartoszcze M, Gryko R, Michalski A. Utilisation of peptides against microbial infections–a review. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2018;25(2). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Jahangiri A, Neshani A, Mirhosseini SA, Ghazvini K, Zare H, Sedighian H. Synergistic effect of two antimicrobial peptides, Nisin and P10 with conventional antibiotics against extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and colistin-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Microb Pathog. 2021;150:104700. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosikowska P, Lesner A. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) as drug candidates: a patent review (2003–2015). Expert opinion on therapeutic patents. 2016;26(6):689–702. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Kang H-K, Kim C, Seo CH, Park Y. The therapeutic applications of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): a patent review. J Microbiol. 2017;55(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-6452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan J, Tay J, Hedrick J, Yang YY. Synthetic macromolecules as therapeutics that overcome resistance in cancer and microbial infection. Biomaterials. 2020;252:120078. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei J, Sun L, Huang S, Zhu C, Li P, He J, et al. The antimicrobial peptides and their potential clinical applications. Am J translational Res. 2019;11(7):3919. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed A, Siman-Tov G, Hall G, Bhalla N, Narayanan A. Human antimicrobial peptides as therapeutics for viral infections. Viruses. 2019;11(8):704. doi: 10.3390/v11080704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braff MH, Mi‘i AH, Di Nardo A, Lopez-Garcia B, Howell MD, Wong C, et al. Structure-function relationships among human cathelicidin peptides: dissociation of antimicrobial properties from host immunostimulatory activities. J Immunol. 2005;174(7):4271–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neshani A, Zare H, Eidgahi MRA, Kakhki RK, Safdari H, Khaledi A, et al. LL-37: Review of antimicrobial profile against sensitive and antibiotic-resistant human bacterial pathogens. Gene Rep. 2019;17:100519. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2019.100519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dürr UH, Sudheendra U, Ramamoorthy A. LL-37, the only human member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim et Biophys Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes. 2006;1758(9):1408–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carretero M, Escámez MJ, García M, Duarte B, Holguín A, Retamosa L, et al. In vitro and in vivo wound healing-promoting activities of human cathelicidin LL-37. J Invest Dermatology. 2008;128(1):223–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koczulla R, Von Degenfeld G, Kupatt C, Krötz F, Zahler S, Gloe T, et al. An angiogenic role for the human peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18. J Clin Investig. 2003;111(11):1665–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI17545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chertov O, Michiel DF, Xu L, Wang JM, Tani K, Murphy WJ, et al. Identification of defensin-1, defensin-2, and CAP37/azurocidin as T-cell chemoattractant proteins released from interleukin-8-stimulated neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(6):2935–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larrick JW, Hirata M, Balint RF, Lee J, Zhong J, Wright SC. Human CAP18: a novel antimicrobial lipopolysaccharide-binding protein. Infect Immun. 1995;63(4):1291–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1291-1297.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Miguel Catalina A, Forbrig E, Kozuch J, Nehls C, Paulowski L, Gutsmann T, et al. The C-Terminal VPRTES Tail of LL-37 influences the mode of attachment to a lipid bilayer and antimicrobial activity. Biochemistry. 2019;58(19):2447–62. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zsila F, Kohut G, Beke-Somfai T. Disorder-to-helix conformational conversion of the human immunomodulatory peptide LL-37 induced by antiinflammatory drugs, food dyes and some metabolites. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;129:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.01.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iacob SA, Banica D, Panaitescu E, Cojocaru M, Iacob D, editors. The plasma level of cathelicidin-LL37 in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus. Proceedings of World Medical Conference, Malta, ed WSEAS Press; 2010.

- 40.Matsumura T, Sugiyama N, Murayama A, Yamada N, Shiina M, Asabe S, et al. Antimicrobial peptide LL-37 attenuates infection of hepatitis C virus. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(9):924–32. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puig-Basagoiti F, Fukuhara T, Tamura T, Ono C, Uemura K, Kawachi Y, et al. Human cathelicidin compensates for the role of apolipoproteins in hepatitis C virus infectious particle formation. J Virol. 2016;90(19):8464–77. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00471-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iacob SA, Panaitescu E, Iacob DG, Cojocaru M. The human cathelicidin LL37 peptide has high plasma levels in B and C hepatitis related to viral activity but not to 25-hydroxyvitamin D plasma level. Romanian J Intern Medicine = Revue Roumaine de Med Interne. 2012;50(3):217–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saleh M, Welsch C, Cai C, Döring C, Gouttenoire J, Friedrich J, et al. Differential modulation of hepatitis C virus replication and innate immune pathways by synthetic calcitriol-analogs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;183:142–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsukita S, Furuse M. Occludin and claudins in tight-junction strands: leading or supporting players? Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9(7):268–73. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhawan P, Singh AB, Deane NG, No Y, Shiou S-R, Schmidt C, et al. Claudin-1 regulates cellular transformation and metastatic behavior in colon cancer. J Clin Investig. 2005;115(7):1765–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI24543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Tscherne DM, Syder AJ, Panis M, Wölk B, et al. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature. 2007;446(7137):801–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Si Y, Liu S, Liu X, Jacobs JL, Cheng M, Niu Y, et al. A human claudin-1–derived peptide inhibits hepatitis C virus entry. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):507–15. doi: 10.1002/hep.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Mammalian defensins in the antimicrobial immune response. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(6):551–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lehrer RI, Lichtenstein AK, Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial and cytotoxic peptides of mammalian cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11(1):105–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shafee TM, Lay FT, Phan TK, Anderson MA, Hulett MD. Convergent evolution of defensin sequence, structure and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(4):663–82. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2344-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daher KA, Selsted ME, Lehrer RI. Direct inactivation of viruses by human granulocyte defensins. J Virol. 1986;60(3):1068–74. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.3.1068-1074.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang L, Yu W, He T, Yu J, Caffrey RE, Dalmasso EA, et al. Contribution of human α-defensin 1, 2, and 3 to the anti-HIV-1 activity of CD8 antiviral factor. Science. 2002;298(5595):995–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1076185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ryan LK, Dai J, Yin Z, Megjugorac N, Uhlhorn V, Yim S, et al. Modulation of human β-defensin‐1 (hBD‐1) in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDC), monocytes, and epithelial cells by influenza virus, Herpes simplex virus, and Sendai virus and its possible role in innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90(2):343–56. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ericksen B, Wu Z, Lu W, Lehrer RI. Antibacterial activity and specificity of the six human α-defensins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(1):269–75. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.269-275.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoffmann JA, Hetru C. Insect defensins: inducible antibacterial peptides. Immunol Today. 1992;13(10):411–5. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90092-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lay F, Anderson M. Defensins-components of the innate immune system in plants. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005;6(1):85–101. doi: 10.2174/1389203053027575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mattar EH, Almehdar HA, AlJaddawi AA, Abu Zeid IEM, Redwan EM. Elevated concentration of defensins in hepatitis C virus-infected patients. Journal of immunology research. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Owusu DO, Owusu M, Owusu BA. Human defensins and Th-1 cytokines in hepatitis C viral infection. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Aceti A, Mangoni M, Pasquazzi C, Fiocco D, Marangi M, Miele R, et al. α-Defensin increase in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with hepatitis C virus chronic infection. J Viral Hepatitis. 2006;13(12):821–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaltsa G, Bamias G, Siakavellas SI, Goukos D, Karagiannakis D, Zampeli E, et al. Systemic levels of human β-defensin 1 are elevated in patients with cirrhosis. Annals of Gastroenterology: Quarterly Publication of the Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology. 2016;29(1):63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ling Y-M, Chen J-Y, Guo L, Wang C-Y, Tan W-T, Wen Q, et al. β-defensin 1 expression in HCV infected liver/liver cancer: an important role in protecting HCV progression and liver cancer development. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13332-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma D, Lin L, Zhang K, Han Z, Shao Y, Liu X, et al. Three novel Anas platyrhynchos avian β-defensins, upregulated by duck hepatitis virus, with antibacterial and antiviral activities. Mol Immunol. 2011;49(1–2):84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen F, Yu M, Zhong Y, Wang L, Huang H. Characteristics and Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Asthma. Inflammation. 2021:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Mattar EH, Almehdar HA, Uversky VN, Redwan EM. Virucidal activity of human α-and β-defensins against hepatitis C virus genotype 4. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12(9):2785–97. doi: 10.1039/C6MB00283H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng Y, Sun F, Li S, Gao M, Wang L, Sarhan M, et al. Inhibitory activity of a scorpion defensin BmKDfsin3 against Hepatitis C virus. Antibiotics. 2020;9(1):33. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zeng Z, Zhang Q, Hong W, Xie Y, Liu Y, Li W, et al. A scorpion defensin bmkdfsin4 inhibits hepatitis b virus replication in vitro. Toxins. 2016;8(5):124. doi: 10.3390/toxins8050124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cuesta A, Meseguer J, Esteban MA. The antimicrobial peptide hepcidin exerts an important role in the innate immunity against bacteria in the bony fish gilthead seabream. Mol Immunol. 2008;45(8):2333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krause A, Neitz S, Mägert H-J, Schulz A, Forssmann W-G, Schulz-Knappe P, et al. LEAP-1, a novel highly disulfide-bonded human peptide, exhibits antimicrobial activity. FEBS Lett. 2000;480(2–3):147–50. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01920-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fujita N, Sugimoto R, Takeo M, Urawa N, Mifuji R, Tanaka H, et al. Hepcidin expression in the liver: relatively low level in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Mol Med. 2007;13(1):97–104. doi: 10.2119/2006-00057.Fujita. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Girelli D, Pasino M, Goodnough JB, Nemeth E, Guido M, Castagna A, et al. Reduced serum hepcidin levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2009;51(5):845–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin D, Ding J, Liu J-Y, He Y-F, Dai Z, Chen C-Z, et al. Decreased serum hepcidin concentration correlates with brain iron deposition in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e65551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fontana RJ, Israel J, LeClair P, Banner BF, Tortorelli K, Grace N, et al. Iron reduction before and during interferon therapy of chronic hepatitis C: results of a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2000;31(3):730–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piperno A, Sampietro M, D’Alba R, Roffi L, Fargion S, Parma S, et al. Iron stores, response to α-interferon therapy, and effects of iron depletion in chronic hepatitis C. Liver. 1996;16(4):248–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1996.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fargion S, Fracanzani AL, Rossini A, Borzio M, Riggio O, Belloni G, et al. Iron reduction and sustained response to interferon-α therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: results of an Italian multicenter randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(5):1204–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu H, Le Trinh T, Dong H, Keith R, Nelson D, Liu C. Iron regulator hepcidin exhibits antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kohjima M, Yoshimoto T, Enjoji M, Fukushima N, Fukuizumi K, Nakamura T, et al. Hepcidin/ferroportin expression levels involve efficacy of pegylated-interferon plus ribavirin in hepatitis C virus-infected liver. World J Gastroenterology: WJG. 2015;21(11):3291. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Inomata S, Anan A, Yamauchi E, Yamauchi R, Kunimoto H, Takata K, et al. Changes in the serum hepcidin-to-ferritin ratio with erythroferrone after hepatitis C virus eradication using direct-acting antiviral agents. Intern Med. 2019;58(20):2915–22. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2909-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hörl WH, Schmidt A. Low hepcidin triggers hepatic iron accumulation in patients with hepatitis C. Nephrol Dialysis Transplantation. 2014;29(6):1141–4. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bartolomei G, Cevik RE, Marcello A. Modulation of hepatitis C virus replication by iron and hepcidin in Huh7 hepatocytes. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(9):2072–81. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.032706-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olmez OF, Gurel S, Yilmaz Y. Plasma prohepcidin levels in patients with chronic viral hepatitis: relationship with liver fibrosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22(4):461–5. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283344708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Georgopoulou U, Dimitriadis A, Foka P, Karamichali E, Mamalaki A. Hepcidin and the iron enigma in HCV infection. Virulence. 2014;5(4):465–76. doi: 10.4161/viru.28508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kemna EH, Tjalsma H, Willems J, Swinkels DW. Hepcidin: from discovery to differential diagnosis. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Wang X-h, Cheng P-P, Jiang F, Jiao X-Y. The effect of hepatitis B virus infection on hepcidin expression in hepatitis B patients. Annals of Clinical & Laboratory Science. 2013;43(2):126–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Orsi N. The antimicrobial activity of lactoferrin: current status and perspectives. Biometals. 2004;17(3):189–96. doi: 10.1023/B:BIOM.0000027691.86757.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Valenti P, Antonini G, Lactoferrin Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(22):2576–87. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5372-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hara K, Ikeda M, Saito S, Matsumoto S, Numata K, Kato N, et al. Lactoferrin inhibits hepatitis B virus infection in cultured human hepatocytes. Hepatol Res. 2002;24(3):228–35. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6346(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Redwan EM, El-Fakharany EM, Uversky VN, Linjawi MH. Screening the anti infectivity potentials of native N-and C-lobes derived from the camel lactoferrin against hepatitis C virus. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jenssen H. Anti herpes simplex virus activity of lactoferrin/lactoferricin–an example of antiviral activity of antimicrobial protein/peptide. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2005;62(24):3002–13. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.HASEGAWA K, MOTSUCHI W, TANAKA S. DOSAKO S-i. Inhibition with lactoferrin of in vitro infection with human herpes virus. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1994;47(2):73–85. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.47.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Berkhout B, van Wamel JL, Beljaars L, Meijer DK, Visser S, Floris R. Characterization of the anti-HIV effects of native lactoferrin and other milk proteins and protein-derived peptides. Antiviral Res. 2002;55(2):341–55. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baker E, Baker H, Lactoferrin Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(22):2531–9. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5368-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Berlutti F, Pantanella F, Natalizi T, Frioni A, Paesano R, Polimeni A, et al. Antiviral properties of lactoferrin—a natural immunity molecule. Molecules. 2011;16(8):6992–7018. doi: 10.3390/molecules16086992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Florian PE, Macovei A, Lazar C, Milac AL, Sokolowska I, Darie CC, et al. Characterization of the anti-HBV activity of HLP1–23, a human lactoferrin‐derived peptide. J Med Virol. 2013;85(5):780–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yi M, Kaneko S, Yu D, Murakami S. Hepatitis C virus envelope proteins bind lactoferrin. J Virol. 1997;71(8):5997–6002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5997-6002.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Picard-Jean F, Bouchard S, Larivée G, Bisaillon M. The intracellular inhibition of HCV replication represents a novel mechanism of action by the innate immune Lactoferrin protein. Antiviral Res. 2014;111:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.El-Fakharany EM, Serour EA, Abdelrahman AM, Haroun BM, Redwan E-RM. Purification and characterization of camel (Camelus dromedarius) milk amylase. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;39(2):105–23. doi: 10.1080/10826060902800288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Almahdy O, El-Fakharany EM, Ehab E-D, Ng TB, Redwan EM. Examination of the activity of camel milk casein against hepatitis C virus (genotype-4a) and its apoptotic potential in hepatoma and hela cell lines. Hepat monthly. 2011;11(9):724. doi: 10.5812/kowsar.1735143X.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Redwan ERM, Tabll A. Camel lactoferrin markedly inhibits hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection of human peripheral blood leukocytes. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2007;28(3):267–77. doi: 10.1080/15321810701454839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.EL FAKHARANY EM, Tabll A, Abd El Wahab A, Haroun BM, Redwan E-RM. Potential activity of camel milk-amylase and lactoferrin against hepatitis C virus infectivity in HepG2 and lymphocytes. 2008.

- 100.Mygind PH, Fischer RL, Schnorr KM, Hansen MT, Sönksen CP, Ludvigsen S, et al. Plectasin is a peptide antibiotic with therapeutic potential from a saprophytic fungus. Nature. 2005;437(7061):975–80. doi: 10.1038/nature04051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Greber E, Dawgul K. Antimicrobial peptides under clinical trials. Curr Top Med Chem. 2017;17(5):620–8. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160713143331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Abdulrahman AY, Rothan HA, Rashid NN, Lim SK, Sakhor W, Tee KC, et al. Identification of peptide leads to inhibit hepatitis C virus: inhibitory effect of plectasin peptide against hepatitis C serine protease. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2017;23(2):163–70. doi: 10.1007/s10989-016-9544-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lim SK, Othman R, Yusof R, Heh CH. Rational drug discovery: Ellagic acid as a potent dual-target inhibitor against hepatitis C virus genotype 3 (HCV G3) NS3 enzymes. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2021;97(1):28–40. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ciufolini MA, Lefranc D. Micrococcin P1: structure, biology and synthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27(3):330–42. doi: 10.1039/b919071f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Carnio MC, Stachelhaus T, Francis KP, Scherer S. Pyridinyl polythiazole class peptide antibiotic micrococcin P1, secreted by foodborne Staphylococcus equorum WS2733, is biosynthesized nonribosomally. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268(24):6390–401. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rogers MJ, Cundliffe E, McCutchan TF. The antibiotic micrococcin is a potent inhibitor of growth and protein synthesis in the malaria parasite. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42(3):715–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.3.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ciufolini MA, Shen Y-C. Synthesis of the Bycroft – Gowland Structure of Micrococcin P1. Org Lett. 1999;1(11):1843–6. doi: 10.1021/ol991115e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lee M, Yang J, Park S, Jo E, Kim H-Y, Bae Y-S, et al. Micrococcin P1, a naturally occurring macrocyclic peptide inhibiting hepatitis C virus entry in a pan-genotypic manner. Antiviral Res. 2016;132:287–95. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dai C, Ma Y, Zhao Z, Zhao R, Wang Q, Wu Y, et al. Mucroporin, the first cationic host defense peptide from the venom of Lychas mucronatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(11):3967–72. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00542-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Harrison PL, Abdel-Rahman MA, Miller K, Strong PN. Antimicrobial peptides from scorpion venoms. Toxicon. 2014;88:115–37. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.El-Bitar AM, Sarhan MM, Aoki C, Takahara Y, Komoto M, Deng L, et al. Virocidal activity of Egyptian scorpion venoms against hepatitis C virus. Virol J. 2015;12(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yan R, Zhao Z, He Y, Wu L, Cai D, Hong W, et al. A new natural α-helical peptide from the venom of the scorpion Heterometrus petersii kills HCV. Peptides. 2011;32(1):11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hong W, Zhang R, Di Z, He Y, Zhao Z, Hu J, et al. Design of histidine-rich peptides with enhanced bioavailability and inhibitory activity against hepatitis C virus. Biomaterials. 2013;34(13):3511–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.El Hidan MA, Laaradia MA, El Hiba O, Draoui A, Aimrane A, Kahime K. Scorpion-Derived Antiviral Peptides with a Special Focus on Medically Important Viruses: An Update. BioMed Research International. 2021;2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Zeng Z, Zhang R, Hong W, Cheng Y, Wang H, Lang Y, et al. Histidine-rich modification of a scorpion-derived peptide improves bioavailability and inhibitory activity against HSV-1. Theranostics. 2018;8(1):199. doi: 10.7150/thno.21425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhao Z, Hong W, Zeng Z, Wu Y, Hu K, Tian X, et al. Mucroporin-M1 inhibits hepatitis B virus replication by activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and down-regulating HNF4α in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(36):30181–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.370312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pandey R, Singh A, Pandey A, Tripathi P, Majumdar S, Nath L. Protein and peptide drugs: a brief review. Res J Pharm Technol. 2009;2(2):228–33. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Katsila T, Siskos AP, Tamvakopoulos C. Peptide and protein drugs: the study of their metabolism and catabolism by mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2012;31(1):110–33. doi: 10.1002/mas.20340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bidwell GL. Peptides for cancer therapy: a drug-development opportunity and a drug-delivery challenge. Therapeutic delivery. 2012;3(5):609–21. doi: 10.4155/tde.12.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Albericio F, Kruger HG. Therapeutic peptides. Future Med Chem. 2012;4(12):1527–31. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dombu CY, Betbeder D. Airway delivery of peptides and proteins using nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2013;34(2):516–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cheng G, Montero A, Gastaminza P, Whitten-Bauer C, Wieland SF, Isogawa M, et al. A virocidal amphipathic α-helical peptide that inhibits hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(8):3088-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 123.Eron JJ, Gulick RM, Bartlett JA, Merigan T, Arduino R, Kilby JM, et al. Short-term safety and antiretroviral activity of T-1249, a second-generation fusion inhibitor of HIV. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(6):1075–83. doi: 10.1086/381707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Martins do Canto AMT, Palace Carvalho A, Prates Ramalho J, Loura L. Molecular dynamics simulation of HIV fusion inhibitor T-1249: insights on peptide-lipid interaction. Computational and mathematical methods in medicine. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 125.Montero A, Gastaminza P, Law M, Cheng G, Chisari FV, Ghadiri MR. Self-assembling peptide nanotubes with antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus. Chem Biol. 2011;18(11):1453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bruss V, Ganem D. The role of envelope proteins in hepatitis B virus assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1991;88(3):1059-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 127.Le Seyec J, Chouteau P, Cannie I, Guguen-Guillouzo C, Gripon P. Role of the pre-S2 domain of the large envelope protein in hepatitis B virus assembly and infectivity. J Virol. 1998;72(7):5573–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.7.5573-5578.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Le Seyec J, Chouteau P, Cannie I, Guguen-Guillouzo C, Gripon P. Infection process of the hepatitis B virus depends on the presence of a defined sequence in the pre-S1 domain. J Virol. 1999;73(3):2052–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.3.2052-2057.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gripon P, Cannie I, Urban S. Efficient inhibition of hepatitis B virus infection by acylated peptides derived from the large viral surface protein. J Virol. 2005;79(3):1613–22. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1613-1622.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Deng Q, Zhai J-w, Michel M-L, Zhang J, Qin J, Kong Y-y, et al. Identification and characterization of peptides that interact with hepatitis B virus via the putative receptor binding site. J Virol. 2007;81(8):4244–54. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01270-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Glebe D, Aliakbari M, Krass P, Knoop EV, Valerius KP, Gerlich WH. Pre-s1 antigen-dependent infection of Tupaia hepatocyte cultures with human hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 2003;77(17):9511–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9511-9521.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Smith JG, Nemerow GR. Mechanism of adenovirus neutralization by human α-defensins. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3(1):11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Smith JG, Silvestry M, Lindert S, Lu W, Nemerow GR, Stewart PL. Insight into the mechanisms of adenovirus capsid disassembly from studies of defensin neutralization. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(6):e1000959. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hsieh I-N, Hartshorn KL. The role of antimicrobial peptides in influenza virus infection and their potential as antiviral and immunomodulatory therapy. Pharmaceuticals. 2016;9(3):53. doi: 10.3390/ph9030053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Tripathi S, Wang G, White M, Qi L, Taubenberger J, Hartshorn KL. Antiviral activity of the human cathelicidin, LL-37, and derived peptides on seasonal and pandemic influenza A viruses. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0124706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Pace BT, Lackner AA, Porter E, Pahar B. The role of defensins in HIV pathogenesis. Mediators of inflammation. 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 137.Hazrati E, Galen B, Lu W, Wang W, Ouyang Y, Keller MJ, et al. Human α-and β-defensins block multiple steps in herpes simplex virus infection. J Immunol. 2006;177(12):8658–66. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kota S, Sabbah A, Harnack R, Xiang Y, Meng X, Bose S. Role of human β-defensin-2 during tumor necrosis factor-α/NF-κB-mediated innate antiviral response against human respiratory syncytial virus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(33):22417–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710415200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Alagarasu K, Patil P, Shil P, Seervi M, Kakade M, Tillu H, et al. In-vitro effect of human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide LL-37 on dengue virus type 2. Peptides. 2017;92:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Buck CB, Day PM, Thompson CD, Lubkowski J, Lu W, Lowy DR, et al. Human α-defensins block papillomavirus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103(5):1516-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 141.Marr AK, Gooderham WJ, Hancock RE. Antibacterial peptides for therapeutic use: obstacles and realistic outlook. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(5):468–72. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Costa F, Carvalho IF, Montelaro RC, Gomes P, Martins MCL. Covalent immobilization of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) onto biomaterial surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(4):1431–40. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.