Abstract

Objective

Antenatal care (ANC) is crucial to protecting the health of pregnant women and their unborn children; however, the uptake of ANC among pregnant women in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) is suboptimal. One popular strategy to increase the uptake of health services, including ANC visits, are conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes. CCT programmes require beneficiaries to comply with certain conditionalities in order to receive a financial sum. A systematic review was carried out to determine whether CCT programmes have a positive impact on ANC uptake in LMIC populations.

Methods

Electronic databases CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, Maternity and Infant Care and Global Health were searched from database inception to 21 January 2022. Reference checking and grey literature searches were also applied. Eligible study designs were randomised controlled trials, controlled before-after studies and interrupted time series analysis. Risk of bias assessments were undertaken for each study by applying the Risk of Bias 2 tool and the Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions tool.

Results

Out of 1534 screened articles, 18 publications were included for analysis. Eight studies reported statistically non-significant results on all reported outcomes. Seven studies demonstrated statistically significant positive effects ranging from 5.5% to 45% increase in ANC service uptake. A further three studies reported small but statistically significant impact of CCT on the use of ANC services in both positive (2.5% increase) and negative (3.7% decrease) directions. Subanalysis of results disaggregated by socioeconomic status (SES) indicated that ANC attendance may be more markedly improved by CCT programmes in low SES populations; however, results were inconclusive.

Conclusion

Our evidence synthesis presented here demonstrated a highly heterogeneous evidence base pertaining to the impact of CCTs on ANC attendance. More high-powered studies are required to elucidate the true impact of CCT programmes on ANC uptake, with particular focus on the barriers and enablers of such programmes in achieving intended outcomes.

Keywords: Public health, Health economics, Health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive systematic review and synthesis of published evidence on the impact of conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes on antenatal care (ANC) uptake in low and middle-income country (LMIC) populations to date.

Evidence from 18 studies conducted in Africa, Asia and Central and South America was included in this study, representing a diverse sample of LMIC populations.

Heterogeneity in study design and implementation prevented a meta-analysis from being conducted to generate macro-impact statistics.

The descriptive nature of this study precludes conclusions regarding the causality between CCT programme implementation and ANC attendance.

Introduction

Reduction in maternal mortality is a global commitment outlined by the United Nations in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (3.1).1 Despite widespread recognition of the importance of antenatal care (ANC) in reducing maternal mortality2 and enhancing maternal and neonatal health outcomes,3 ANC service uptake remains low in many low and middle-income countries (LMICs).4 WHO recommends that women attend at least eight ANC visits5 during their pregnancy. A substantial proportion of women living in LMICs do not meet this recommendation, and ANC attendance appears to be highly correlated with socioeconomic status (SES) and poverty, reinforcing the notion that the social determinants of health are a strong driving force in influencing health status well before one is even born.6

Numerous reviews have been published that report the effects of demand-side interventions on health service uptake, including ANC attendance.7–10 Cash transfer programmes are one such intervention, and can be an attractive policy lever for increasing positive health-seeking behaviours in certain populations. Cash transfer programmes can be conditional or unconditional. Conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes require beneficiaries to comply with certain conditionalities (eg, regular health check-ups) while unconditional cash transfer programmes do not set such requirements.11 Substantial resources have been allocated to cash transfer programmes in recent years, with an estimated 718 million people receiving assistance through cash transfer programmes in 2014 alone.12

CCTs may be a viable policy strategy to increase ANC uptake among pregnant women in LMICs. Evidence from several studies on the effectiveness of CCT programmes to increase health-seeking behaviours has shown promising positive results.11 13 However, a recent systematic review drew attention to the heterogenous impacts of cash transfer programmes across a range of health behaviours and outcomes, highlighting the need for further research into the key contexts in which such programmes may lead to success, and the barriers, enablers and opportunities for such programmes to thrive.14

Given the well-established correlation between ANC uptake and improved maternal and neonatal health,2 and the low reported rates of ANC attendance across numerous LMIC settings,4 there is an urgent need for bilateral and multilateral agencies and governments to invest in cost-effective interventions to increase ANC uptake. There is insufficient high-quality consistent evidence to elucidate whether CCTs are one such potentially viable intervention. This review aims to address this important knowledge gap and has two primary objectives: to assess the effectiveness of CCT programmes in improving ANC uptake; and to investigate the impact of poverty in relation to ANC attendance.

Methods

Study design

A systematic review was undertaken, adhering to the guidelines from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.15

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility of each article was assessed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Pregnant women and girls | Non-pregnant women and girls |

| CCT programmes | Other programmes including unconditional cash transfer programmes and voucher schemes |

| ANC services | Other services not belonging to ANC |

| Study designs including randomised controlled trials, controlled before-after studies and interrupted time series analysis | Other study designs |

| Relevant information available | Lacking essential information |

ANC, antenatal care; CCT, conditional cash transfer.

Participants

Pregnant women and girls residing in LMICs, defined as per World Bank definition, are eligible. Studies focusing on facilities or geographical areas that include service utilisation data were included. All types of healthcare providers were eligible for inclusion.

Intervention

Studies on CCT programmes were considered for inclusion if these constituted direct monetary transfers for the purpose of increasing health service uptake. Studies on unconditional cash transfers and non-cash transfers (eg, vouchers) were excluded. Interventions encompassing multiple components (with CCTs among them) were included, where it was possible to disaggregate cash transfer impacts from other intervention impacts.

Comparator

This review compares pregnant women and girls who took part in CCT programmes against those who did not.

Outcome

The sole outcome of this review is ANC service uptake. ANC utilisation was measured by health facility utilisation data, health service provision data and quantitative survey data.

Time period

We searched for evidence from database inception to 21 January 2022.

Study type

Study designs aligning with the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) group criteria were included in this review.16 These encompass:

Randomised controlled trials (individual or cluster).

Controlled before-after studies, with data for the period before and after the intervention.

Interrupted time series analysis, with a clear time indication for the intervention and at least three data points before the intervention, and three data points after the intervention.

Systematic reviews were excluded during the screening process, but their reference lists were checked to possibly identify relevant literature.15

Data availability

In line with the EPOC criteria, studies with incomplete or opaque data were not incorporated in the final selection.16 A good example are studies with missing control variables. Authors were contacted for further inquiry as well. Studies with self-reported data are considered, contrary to the EPOC criteria, as filtering out articles reporting on survey-related data obtained by interviewing people would result in little evidence.

Identification of studies

A search was performed on 21 January 2022 using a sensitive search strategy (see online supplemental appendix A) in the following electronic databases: CENTRAL,17 MEDLINE,18 Embase,19 Maternity and Infant Care20 and Global Health.21 The search results were uploaded to Covidence,22 an online tool to support the selection process. Duplicates were automatically removed by the software and manually checked. Title and abstract screening was undertaken by a single reviewer (WJ) for all records, and a random sample of 20% of identified studies was reviewed by a second reviewer (LD) for quality assurance. Full-text review was undertaken by a single reviewer (WJ) and all records for which there was uncertainty were reviewed by a second author (LD) for final decision regarding inclusion/exclusion.15

bmjopen-2022-064673supp001.pdf (275.7KB, pdf)

Reference searching of included studies and follow-up with authors was carried out by a single reviewer (WJ) to ensure that all relevant articles and data were identified.15 Grey literature was also searched by the primary reviewer.15 The organisations identified for the grey literature search were identified by both reviewers and are listed in online supplemental appendix B.

Data extraction

A standardised Microsoft Excel form was used to assist with qualitative data extraction.15 The obtained information from the various studies contains:

Study type (individual or cluster randomised controlled trial, controlled before-after studies and interrupted time series analysis).

Study duration.

Study setting.

Characteristics of participants.

Characteristics of the intervention (transfer amounts and conditionalities).

Main outcome measures and results.

After extraction, the data were cross-checked against the original studies to avoid human error.23 Authors were contacted in case of data ambiguity.15

Inflation adjustment

Cash transfers were adjusted for inflation by presenting their value for the year 2022. This is to allow comparability across CCT programmes.24

Data analysis

The information extracted from the included studies was analysed by using descriptive thematic analysis.15 The analysis included overall effects demonstrated by the studies with further subanalysis on poverty dynamics.

Risk of bias

The Risk of Bias 2 tool recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration was used to assess the risk of bias for the included randomised controlled trials. The tool describes five domains clarifying the risk of bias by trial. These domains include the randomisation process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome and the selection of the reported result. The Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions tool was used to assess the risk of bias for the included controlled before-after studies and research applying interrupted time series analysis. This tool uses domains and signalling questions that are tailored to non-randomised study designs, which encompass bias related to confounding, bias due to selection of study participants, bias in classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in measurement of outcomes and bias in selection of the reported result.15

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement is not applicable as this article is a systematic review of existing evidence. The research question development was informed by the global debate on the effectiveness of CCT programmes.

Results

Search results

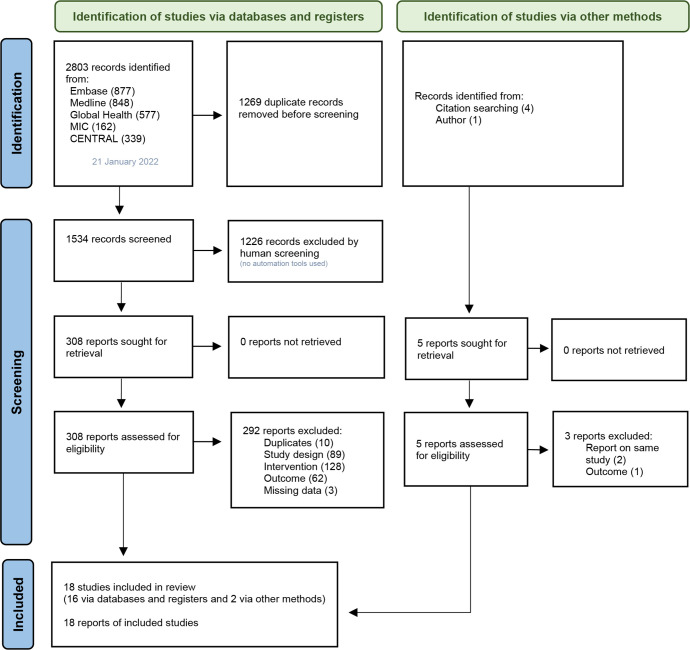

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews were followed.25 The PRISMA flow diagram is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study selection process25

The database search yielded 2803 records. A total of 1534 records remained for title and abstract screening after duplicate studies were removed. These included three duplicates which were removed by Covidence software but added again to the title and abstract screening pool as abstracts were different. Out of the 1534 records, 308 were short-listed for full-text review against the eligibility criteria.

Eighteen studies were included, of which two were identified through other methods. Triyana was identified by contacting the author after requesting for more information on an excluded study.26 Barber and Gertler was included after a reference check of one of the included studies.27

Included studies

Of the 18 included studies, two were interrupted time series analysis, 10 were controlled before-after studies and the remaining six were randomised controlled trials. Barber and Gertler was the final study out of three reporting against the same randomised controlled trial of the Oportunidades programme.27 The article was selected as it was the most recent publication and covered all the necessary information as per EPOC requirements.16 Another author published two articles28 29 on the same randomised controlled trial. The first publication was selected for inclusion.29

The studies in table 2 are included in this review.

Table 2.

Included studies

| No | Author(s) | Year | Programme and study participants | Location and study duration |

| Individual randomised controlled trials | ||||

| 1 | Grépin et al31 | 2019 | M-Kadi Poor pregnant women without formal education (469 participated in the CCT arm at end line out of 1401 total. 481 participated in the CCT arm at baseline out of 1514 total.) |

Kenya (Vihiga county) February 2013 to March 2014 |

| Cluster randomised controlled trials | ||||

| 2 | Barber and Gertler27 | 2010 | Oportunidades Pregnant women (666 treatment and 174 control) |

Mexico 1997–2003 |

| 3 | Kandpal et al36 | 2016 | Pantawid Pamilya Households below poverty line and with children below age 15 or a pregnant woman (462 treatment and 704 control) |

Philippines (4 provinces) October to November 2011 |

| 4 | Okeke and Abubakar29 | 2020 | Conditional cash transfer programme Expectant women (5852 treatment and 5000 control) |

Nigeria (5 states) March 2017 to August 2018 |

| 5 | Triyana26 | 2016 | Program Keluarga Harapan Pregnant and lactating women (8303) |

Indonesia (6 provinces) 2007–2009 |

| 6 | Vanhuyse et al30 | 2022 | Afya Credits Incentive Pregnant women (2522 treatment and 2949 control) |

Kenya (Siaya county) 2017–2019 |

| Controlled before-after studies (all apply difference-in-differences, among other methods) | ||||

| 7 | Kusuma et al37 | 2016 | Program Keluarga Harapan Pregnant and lactating women (8476) |

Indonesia (6 provinces) 2007–2009 |

| 8 | de Brauw and Peterman35 | 2020 | Comunidades Solidarias Rurales Pregnant women (270) |

El Salvador January to November 2008 |

| 9 | Díaz and Saldarriaga41 | 2019 | JUNTOS Pregnant women (9865) |

Peru 2000–2011 |

| 10 | Edmond et al34 | 2019 | CCT programme Women aged 16 years and above delivering in a health facility (treatment: 1199 baseline, 1254 end line; control: 1242 baseline, 1237 end line) |

Afghanistan (3 provinces) November 2016 to December 2017 |

| 11 | Chakrabarti et al39 | 2021 | Mamata Scheme Pregnant and lactating women aged 19 and above (11 036 treatment; 163 539 control 1 and 34 320 control 2) |

India (Odisha state) 1998–2016 |

| 12 | Powell-Jackson et al38 | 2015 | Safe Motherhood Programme Currently married women (340 323) |

India 2001–2008 |

| 13 | Aizawa40 | 2020 | Safe Motherhood Programme Women aged 15–49 years (45 436 treatment and 28 688 control) |

India 2005–2016 |

| 14 | Joshi and Sivaram32 | 2014 | Safe Motherhood Programme Currently married women (425 708 total, over two survey rounds) |

India 2002–2008 |

| 15 | Lim et al42 | 2010 | Safe Motherhood Programme Women (not clear, but mentioning 182 869 households for latest survey round used in study) |

India 2002–2008 |

| 16 | Debnath44 | 2021 | Safe Motherhood Programme Women reporting at least one pregnancy since January 2004 (208 816) |

India 2002–2008 |

| Interrupted time series analysis | ||||

| 17 | Powell-Jackson et al43 | 2009 | Nepal’s Safe Delivery Incentive Programme Women delivering in health facility with less than 3 children or obstetric complication (7613 before programme, 7186 after) |

Nepal (Makwanpur district) 2001–2007 |

| 18 | Okoli et al33 | 2014 | SURE-P/MCH Pregnant women (20 133) |

Nigeria (9 states) January 2012 to March 2014 |

CCT, conditional cash transfer; SURE-P/MCH, Subsidy Reinvestment and Empowerment Programme/Maternal and Child Health.

Included CCT programmes

The selected studies cover 13 CCT programmes presented in table 3. See online supplemental appendix C for more information on the monetary benefits.

Table 3.

Conditional cash transfer programmes covered by the included studies

| No | Programme, location and income | Monetary benefits as reported in studies | 2022 Adjusted monetary benefits per pregnancy | Conditionality | Cointerventions | Time span | CCT beneficiaries |

| A | Program Keluarga Harapan26 37 Indonesia (6 provinces) 47* |

Between US$60 and US$220 per year depending on household characteristics. | US$52.5–US$191.5 | Maternal health and education services including 4 ANC visits, delivery assistance and 2 PNC visits. | Supply-side improvements. | 2007 to present | Pregnant and lactating women from poor households (no information on scope, but covering 6 provinces). |

| B | M-Kadi31 Kenya (Vihiga county) 47* |

US$3 per ANC or PNC visit (maximum 4 ANC and 3 PNC visits) and US$6 per delivery. Maximum total per pregnancy: US$27. |

US$29.5 | Maternal health services including ANC, PNC and facility-based delivery. | No significant cointerventions (but presence of a nationwide free care policy and other research arms including voucher and UCT). |

2013 to end unknown (but ended according to author) |

Pregnant women (481 beneficiaries in 2013). |

| C | Oportunidades27 (previously called PROGRESA) Mexico 47† |

US$15 per household per month (health transfer). | US$172.5 | Health and education services. Regular clinic consultations, health education sessions, at least 5 ANC visits for pregnant women and 2 PNC visits. | Education programme. Maximum US$90 per household per month (primary education transfer) or maximum US$160 per household per month (secondary education transfer). Education transfer is paid by child, and varies by school grade and gender. |

1997 to present | Low-income households including pregnant women in poor communities (5 million households as of 2004). |

| D | Comunidades Solidarias Rurales35 El Salvador 47* |

US$15 per month for households eligible for the health or education benefit. US$20 per month for households eligible for health and education benefits. |

US$145.5–US$194 | ANC visits (+ vaccination and health check-up of woman’s children). |

Community awareness sessions. | 2005 to present | Households in poor municipalities with a pregnant member and children below age 16 (75 000 households in 2013). |

| E | JUNTOS41 Peru 47† |

US$70 each 2 months, transferred to the female head of household. | US$343.5 | 6 ANC visits and PNC (+ health check-up and school attendance of woman’s children). |

No significant cointerventions. | 2005 to present | Poor households with children or pregnant women (1300 municipalities by 2016). |

| F | Safe Motherhood Programme (Janani Suraksha Yojana)32 38 40 42 44 India 47* |

Low-performing states:

High-performing states:

|

US$8.5–US$20.5 | Facility-based delivery. | Incentives to CHWs. CHWs receive US$3 (2022) for each facility-based delivery (across all states). |

2005 to present | Women delivering in a health facility in low-performing states, and those 19 years and above and living below poverty line or part of deprivileged social group in high-performing states (10.4 million beneficiaries in 2015). |

| G | SURE-P/MCH33 Nigeria (9 states) 47* |

US$6 for the first ANC visit, US$2 per additional ANC visit (up to 4), US$12 per delivery and US$6 for PNC visit. | US$35.5 | ANC, facility-based delivery, PNC including vaccinations. | Supply-side intervention. | 2012–2014 | Pregnant women (20 133 beneficiaries as of 2014). |

| H | Safe Delivery Incentive Programme43 Nepal (Makwanpur district) 47* |

US$16 per facility-based delivery if no more than two children or an obstetric complication. | US$21 | Facility-based delivery. | Incentives to healthcare providers. Healthcare provider receives US$6.5 (2022) per assisted delivery. |

2005 to present | Women delivering in a health facility with less than 3 children or obstetric complication (no information on scope but national programme). |

| I | Mamata Scheme39 India (Odisha state) 47* |

US$70 per pregnancy. | US$70 | Maternal and child services including ANC. | Incentives to CHWs. CHWs receive US$2.5 (2022) per beneficiary supported. |

2011 to present | Pregnant and lactating women aged 19 and above (no information on scope but state-wide programme). |

| J | Conditional cash transfer programme34 (no specific name) Afghanistan (3 provinces) 47‡ |

US$15 for each facility-based delivery. | US$16.5 | Facility-based delivery. | Incentive to CHWs, CHW training and IEC programme. Also supply-side improvements. CHWs receive US$5.5 (2022) for each facility-based delivery. |

December 2016 to December 2017 | Women aged 16 years and above delivering in a health facility (2453 beneficiaries in 2016). |

| K | Pantawid Pamilya36 Philippines (4 provinces) 47* |

US$11–US$32 every 2 months (mix of health and education grants which depend on household characteristics). |

US$57.5–US$167.5 | ANC, facility-based delivery, PNC, attending family development session (+ child education and health). |

Family development sessions. | 2008 to present | Households below poverty line and with children below age 15 or a pregnant woman (4.45 million households as of December 2014). |

| L | Conditional cash transfer programme29 (no specific name) Nigeria (5 states) 47* |

US$14 per pregnancy. | US$15 | At least 3 ANC visits, facility-based delivery and 1 PNC visit. | No significant cointerventions. | 2017 to present | Households with expectant women (180 primary health service areas across five states). |

| M | Afya Credits Incentive30 Kenya (Siaya county) 47* |

US$4.5 per scheduled health visit, 7 visits per pregnancy | US$31.5 | ANC, facility-based delivery, PNC and childhood immunisation. | No significant cointerventions. | 2014–2020 | Pregnant women (5471 beneficiaries as of 2019). |

Monetary benefits are extracted as reported in the studies. For studies reporting against the same conditional cash transfer programme, the monetary benefits were taken from the most recent study. Income categories are obtained from the World Bank. The US Inflation Calculator24 has been used to determine the 2022 dollar values. Symbols have been used to indicate country income level.

*Lower middle-income economy.

†Upper middle-income economy.

‡Low-income economy.

ANC, antenatal care; CCT, conditional cash transfer; CHW, community health worker; IEC, information, education and communication; PNC, postnatal care; SURE-P/MCH, Subsidy Reinvestment and Empowerment Programme/Maternal and Child Health; UCT, unconditional cash transfer.

Risk of bias in the included studies

Randomised controlled trials

Among the six included randomised controlled trials, only Vanhuyse et al30 stated if the reported result was in line with a predetermined set of outcome indicators. Okeke and Abubakar,29 Grépin et al31 and Vanhuyse et al30 were rated as having a high risk of bias on randomisation, as each study failed to conceal the allocation sequence until study participants were enrolled and assigned to the CCT or control group (see online supplemental appendix D for comprehensive risk of bias assessment of each study).

Controlled before-after studies and interrupted time series analysis

Of the 12 included non-randomised studies, Joshi and Sivaram32 and Okoli et al33 indicated that reported results were in line with a research protocol. Almost all studies reported difficulties regarding accurate measurement of outcomes as participants were aware of the cash transfers provided to them. Factors lowering this risk were poorly documented in the studies. Edmond et al34 and Okoli et al33 were rated as having a serious risk of bias related to confounding (see online supplemental appendix D).

Effect estimates

The reported effect estimates of CCT programmes on ANC service uptake are presented in table 4.

Table 4.

Treatment effects of included studies

| No | Author(s) | Year | Programme and benefits (adjusted for inflation, showing 2022 value) |

Outcome description | Treatment effect | Statistical information | Data source |

| Individual randomised controlled trials | |||||||

| 1 | Grépin et al31 | 2019 | M-Kadi (Kenya) US$29.5 per pregnancy |

Four or more ANC visits | 0.045 RC (6.9% increase) |

Control: 0.65 95% CI: NA SE: 0.068 P>0.1 |

Registers and survey (conducted by programme) |

| Cluster randomised controlled trials | |||||||

| 2 | Barber and Gertler27 | 2010 | Oportunidades (Mexico) US$172.5 per pregnancy |

Any prenatal care | 0.034 RC (3.6% increase) |

Control: 0.943 95% CI: NA SE: 0.236 |

Survey (ENCEL survey, socioeconomic survey and fertility survey) |

| Obtained five prenatal care visits | 0.015 RC (2% increase) |

Control: 0.742 95% CI: NA SE: 0.130 |

|||||

| Number of prenatal visits | −0.0348 RC (0.5% decrease) |

Control: 6.40 95% CI: NA SE: 0.037 |

|||||

| 3 | Kandpal et al36 | 2016 | Pantawid Pamilya (Philippines) US$57.5–US$167.5 per pregnancy |

Four or more ANC visits | 7.648 RC (13.9% increase) |

Control: 54.911 95% CI −3.148 to 18.443 P>0.1 |

Survey (specific impact evaluation, Family Income and Expenditure Survey and NDHS) |

| Number of times ANC was received | 0.596 RC (14.4% increase) |

Control: 4.147 95% CI −0.088 to 1.280 P=0.09 |

|||||

| 4 | Okeke and Abubakar29 | 2020 | CCT programme (Nigeria) US$15 per pregnancy |

Number of prenatal visits attended | 0.471 RC (19.8% increase) |

Control: 2.378 95% CI: NA SE: 0.0655 P<0.01 |

Survey (conducted by programme) |

| 5 | Triyana26 | 2016 | Program Keluarga Harapan (Indonesia) US$52.5–US$191.5 per pregnancy |

Prenatal visits | 0.084 RC (1.2% increase) |

Control: 7.00 95% CI: NA SE: 0.317 P>0.1 |

Survey (conducted by National Planning Agency and World Bank) |

| 6 | Vanhuyse et al30 | 2022 | Afya Credits Incentive (Kenya) US$31.5 per pregnancy Nurses receive US$5 for each woman enrolled in the CCT programme. |

Antenatal care appointments attended | 1.90 OR (odds of ANC being 1.9 times higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI 1.36 to 2.66 P<0.001 |

Survey (conducted by programme) Electronic card reading system |

| Controlled before-after studies (all applied difference-in-differences methodology) | |||||||

| 7 | Kusuma et al37 | 2016 | Program Keluarga Harapan (Indonesia) US$52.5–US$191.5 per pregnancy |

Four or more prenatal visits | 0.039 RC (5.7% increase) |

Control: 0.68 95% CI: NA SE: 0.023 P<0.1 |

Survey (conducted by National Planning Agency and World Bank) |

| 8 | de Brauw and Peterman35 | 2020 | Comunidades Solidarias Rurales (El Salvador) US$145.5–US$194 per pregnancy |

Five or more prenatal visits | −0.102 RC (13.7% decrease) |

Control: 0.744 95% CI: NA SE: 0.073 P=0.206 |

Survey (conducted by IFPRI and FUSADES) |

| 9 | Díaz and Saldarriaga41 | 2019 | JUNTOS (Peru) US$343.5 per pregnancy |

Number of prenatal appointments | 0.328 RC (4.7% increase) |

Control: 7.009 95% CI: NA SE: 0.148 P<0.05 |

Survey (Peruvian DHS) |

| One or more ANC visits | 0.028 RC (2.9% increase) |

Control: 0.955 95% CI: NA SE: 0.011 P<0.05 |

|||||

| Four or more ANC visits | 0.048 RC (5.5% increase) |

Control: 0.876 95% CI: NA SE: 0.017 P<0.01 |

|||||

| 10 | Edmond et al34 | 2019 | CCT programme (Afghanistan) US$16.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$5.5 for each facility-based delivery. |

One or more ANC visits | 45.0% AMD (45.0% higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI 0.18 to 0.72 P=0.004 |

Survey HMIS |

| 11 | Chakrabarti et al39 | 2021 | Mamata Scheme (India) US$70 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$2.5 per programme beneficiary. |

Four or more ANC visits | 1.51 OR (odds of ANC being 1.51 times higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI 1.15 to 1.99 |

Survey (NFHS second, third and fourth waves) |

| 12 | Powell-Jackson et al38 | 2015 | Safe Motherhood Programme (India) US$8.5–US$20.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$3 for each facility-based delivery. |

Three or more ANC visits | 0.010 RC (2.2% increase) |

Control: 0.45 95% CI: NA SE: 0.0073 P>0.1 |

Survey (DLHS-II and DLHS-III) |

| 13 | Aizawa40 | 2020 | Safe Motherhood Programme (India) US$8.5–US$20.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$3 for each facility-based delivery. |

Three or more ANC visits | 0.0962 RC (22.9% increase) |

Control: 0.42 95% CI: NA SE: 0.0113 P<0.01 |

Survey (NFHS third and fourth waves) |

| 14 | Joshi and Sivaram32 | 2014 | Safe Motherhood Programme (India) US$8.5–US$20.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$3 for each facility-based delivery. |

Three or more ANC visits | −0.004 RC (1.3% decrease) |

Control: 0.298 95% CI: NA SE: 0.010 P>0.1 |

Survey (DLHS-II and DLHS-III) |

| 15 | Lim et al42 | 2010 | Safe Motherhood Programme (India) US$8.5–US$20.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$3 for each facility-based delivery. |

Three or more ANC visits | 10.7% (increase among treatment group, using ‘exact matching’) | Control: NA 95% CI 0.091 to 0.123 |

Survey (DLHS-II and DLHS-III) |

| 11.1% (increase among treatment group, using ‘with vs without’) | Control: NA 95% CI 0.101 to 0.121 |

||||||

| 10.9% (increase among treatment group, using ‘difference-in-differences’) | Control: NA 95% CI 0.046 to 0.172 |

||||||

| 16 | Debnath44 | 2021 | Safe Motherhood Programme (India) US$8.5–US$20.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$3 for each facility-based delivery. |

Any prenatal care | 0.022 RC (2.4% increase) |

Control: 0.908 95% CI 0.013 to 0.032 SE: 0.005 P<0.01 |

Survey (DLHS-II and DLHS-III) |

| Interrupted time series analysis | |||||||

| 17 | Powell-Jackson et al43 | 2009 | Safe Delivery Incentive Programme (Nepal) US$21 per pregnancy Healthcare provider receives US$6.5 per assisted delivery. |

Number of ANC visits | 0.031 RC (2.5% increase) Using quartic time function |

Control: 1.235 T-statistic: 0.38 95% CI: NA |

Community surveillance system data set |

| −0.046 RC (3.7% decrease) Using quadratic time function |

Control: 1.235 T-statistic: −0.75 95% CI: NA |

||||||

| 18 | Okoli et al33 | 2014 | SURE-P/MCH (Nigeria) US$35.5 per pregnancy |

Four or more ANC visits | 15.1152 RC (increase of 15.1 visits per 100 000 population) |

Control: NA T-statistic: 4.13 P=0.001 95% CI 7.38 to 22.85 |

Programme monitoring data (from facility logbooks) |

| Number of first ANC visits | −8.3150 RC (decrease of 8.3 visits per 100 000 population) |

Control: NA T-statistic: −1.29 P=0.213 95% CI −21.87 to 5.24 |

|||||

Treatment effects include regression coefficients (RC), odds ratios (OR), adjusted means difference (AMD) or other types described in full. Financial benefits are maximum amounts and can vary among beneficiaries depending on compliance with conditions. Amounts per pregnancy presented in 2022 values using US Inflation Calculator.24

ANC, antenatal care; CCT, conditional cash transfer; CI, confidence interval; DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; DLHS, District Level Health Survey; ENCEL, Encuesta Evaluation de los Hogares; FUSADES, Fundación Salvadoreña para El Desarrollo Económico y Social; HMIS, Health Management Information System; IFPRI, International Food Policy Research Institute; NA, not available; NDHS, National Demographic and Health Survey; NFHS, National Family Health Survey; SE, standard error; SURE-P/MCH, Subsidy Reinvestment and Empowerment Programme/Maternal and Child Health.

Eight studies26 27 31 32 35–38 presented statistically non-significant results on all reported outcomes. Seven studies29 30 34 39–42 reported a statistically significant increase of over 5% in ANC service uptake. Three studies33 43 44 reported limited or negative effects.

A meta-analysis was not performed due to the heterogeneity of the selected studies. There are notable differences regarding the interventions, including the cash amounts and conditionalities. There is also variation in study settings, study population, study methodologies and data reported.15

Poverty dynamics

Out of the 18 included studies in this review, four controlled before-after studies contained in-depth poverty-related information.32 34 39 40 Studies were included if treatment effects could be retrieved for groups with different SES. Studies used different definitions for poverty, thereby impeding potential comparisons across settings. The treatment effects by population group are displayed in table 5.

Table 5.

Poverty-related treatment effects from included studies containing information on poverty

| No | Author(s) | Year | Programme and benefits (adjusted for inflation, showing 2022 value) |

Outcome description | Population group | Treatment effect | Statistical information | Data source |

| 10 | Edmond et al34 | 2019 | CCT programme (Afghanistan) US$16.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$5.5 for each facility-based delivery. |

One or more ANC visits | Poorest quintile | 43.2% AMD (43.2% higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI −0.17 to 1.03 P=0.145 |

Survey HMIS |

| Second poorest quintile | 55.4% AMD (55.4% higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI 0.10 to 1.00 P=0.021 |

||||||

| Third poorest quintile | 58.0% AMD (58.0% higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI 0.23 to 0.94 P=0.004 |

||||||

| Second wealthiest quintile | 29.0% AMD (29.0% higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI −0.08 to 0.66 P=0.112 |

||||||

| Wealthiest quintile | 28.8% AMD (28.8% higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI −0.04 to 0.61 P=0.077 |

||||||

| 11 | Chakrabarti et al39 | 2021 | Mamata Scheme (India) US$70 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$2.5 per programme beneficiary. |

Four or more ANC visits | Poorest two quintiles | 1.82 OR (odds of ANC being 1.82 times higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI 1.30 to 2.56 |

Survey (NFHS second, third and fourth waves) |

| Wealthiest three quintiles | 1.19 OR (odds of ANC being 1.19 times higher than control group) |

Control: NA 95% CI 0.95 to 1.49 |

||||||

| 13 | Aizawa40 | 2020 | Safe Motherhood Programme (India) US$8.5–US$20.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$3 for each facility-based delivery. |

Three or more ANC visits | Poor (or women with a below-the-poverty card and experienced up to a second live birth or women belonging to a scheduled caste/tribe and experienced up to a second live birth) |

0.0997 RC (23.7% increase) Note this coefficient is a combination of two coefficients: 0.07671 and 0.02302 which come with different SE and p values. |

Control: 0.42 SE1: 0.0252 SE2: 0.0273 P1<0.01 P2>0.1 |

Survey (NFHS third and fourth waves) |

| Non-poor | 0.0767 RC (18.3% increase) |

Control: 0.42 SE: 0.0252 P<0.01 |

||||||

| 14 | Joshi and Sivaram32 | 2014 | Safe Motherhood Programme (India) US$8.5–US$20.5 per pregnancy Community health workers receive US$3 for each facility-based delivery. |

Three or more ANC visits | Poorest quintile | 0.005 RC (0.74% increase) |

Control: 0.680 SE: 0.010 P>0.1 |

Survey (DLHS-II and DLHS-III) |

| All quintiles | −0.004 RC (1.3% decrease) |

Control: 0.298 SE: 0.010 P>0.1 |

Treatment effects include regression coefficients (RC), odds ratios (OR), adjusted means difference (AMD) or other types described in full. Financial benefits are maximum amounts and can vary among beneficiaries depending on compliance with conditions. Amounts per pregnancy presented in 2022 values using US Inflation Calculator.24

ANC, antenatal care; CCT, conditional cash transfer; CI, confidence interval; DLHS, District Level Health Survey; HMIS, Health Management Information System; NA, not available; NFHS, National Family Health Survey; SE, standard error.

Of the four studies that reported on treatment effect disaggregated by SES, two34 39 reported significantly higher ANC attendance in lower SES groups compared with control populations than did higher SES groups. The remaining two studies32 40 did not report statistically significant results in relation to this outcome.

Discussion

There is a pressing need across LMICs to increase the proportion of women who attend ANC, as recommended by WHO, in order to reduce maternal mortality and poor neonatal health outcomes.2 5 CCT programmes are a potentially promising policy lever to increase uptake of ANC across LMIC contexts; however, current evidence for the impact of CCTs on ANC is unclear. In this review, we have built on the evidence generated by previous published reviews7–10 of demand-side interventions on ANC uptake, to elucidate the specific impact of CCTs on this outcome of interest. Our findings are generally consistent with the existing evidence base that indicates that some CCT programmes have a modest positive impact on ANC attendance, but that other programmes fail to generate such impact, indicating high context specificity of such programmes in relation to ANC service uptake.

Of the 18 studies reviewed covering 13 CCT programmes, eight26 27 31 32 35–38 presented statistically non-significant results on all reported treatment effects, three33 43 44 demonstrated statistically significant limited or negative effects on the utilisation of ANC services and seven29 30 34 39–42 demonstrated a statistically significant increase in ANC service uptake ranging from 5.5% to 45%. The studies that did report statistically significant improvement in ANC uptake as a result of CCT programmes were delivered in Peru,41 Nigeria,29 Afghanistan,34 India39 40 42 and Kenya,30 where programme settings and modalities vary greatly. The studies that reported small or negative impacts of CCTs on ANC uptake were delivered in India,44 Nepal43 and Nigeria.33 The fact that divergent associations between CCTs and ANC uptake were reported in programmes implemented in India and Nigeria, coupled with the general heterogeneity of programme impact across the studies reviewed, indicates that programme design and implementation context might be vital factors in determining programme success.

The amount of money transferred has been postulated to play a key role in incentivising behaviour, and may be an important factor in whether or not the CCT programmes included in this review observed a positive impact.45 The study of the ‘Mamata’ scheme in India39 reported a notable positive impact, which could relate to the relatively high transfer amounts (US$70 per pregnancy) provided to women. This positive relationship between transfer amount and positive trends in ANC uptake is also supported by findings from the ‘JUNTOS’ programme in Peru,41 which similarly transferred a relatively high monetary amount (US$343.5 per pregnancy) compared with other studies and reported a statistically significant positive programme impact. However, in this review, we also identified programmes in which CCT using relatively low transfer amounts also reported positive impacts of CCT on ANC uptake. The CCT programmes best illustrating the complex relationship between financial allocation and programme success are those implemented in Nigeria, in which the CCT programme29 reported better results than the Subsidy Reinvestment and Empowerment Programme/Maternal and Child Health (SURE-P/MCH) programme,33 despite it being implemented in the same country with a transfer amount that is more than double of the CCT programme.29

Previous studies have established that conditionalities are crucial for impact across a range of health-seeing behaviours46 and could play a key role in increasing ANC service uptake. The ‘Mamata’ scheme in India39 required incremental ANC attendance, while the Safe Motherhood Programme in India40 42 44 focused on an endpoint of facility-based deliveries, with the former generating more impact overall. The Afya Credits Incentive in Kenya,30 the CCT programme in Nigeria29 and the ‘JUNTOS’ programme in Peru,41 which reported positive impacts, similarly allocated financial payments to ANC attendance conditionality. However, this conditionality of ANC attendance was not uniformly associated with increased ANC uptake across all studies reviewed, for example, the SURE-P/MCH programme in Nigeria33 reported limited programme impact despite ANC conditionality.

The differences in treatment effects among studies examining the same CCT programme warrant further scrutiny. Three included studies40 42 44 reported statistically significant results on the Safe Motherhood Programme in India using different data to analyse programme impact. Reported increase in ANC uptake as a result of the same CCT programme ranged from 2.4%44 to 22.9%.40 Aizawa40 demonstrated the strongest association between CCT and ANC uptake and used data from the National Family Health Survey conducted in 2006 and 2016 comparing various Indian states. Lim et al42 presented a lower positive association (11.1%) and used data from the District-Level Household Survey from 2004 and 2009. Debnath44 reported the smallest impact and used the same survey data as Lim et al,42 but opted for a restricted sample excluding numerous districts in India. Such heterogeneity indicates the complexity of policy evaluation as different results are reported on the same CCT programme.

We found inconclusive results regarding the relationship between poverty and CCT programme impact. The four studies32 34 39 40 that reported comparisons between socioeconomic groups and the impact of CCT on ANC uptake lacked statistical power to formulate robust conclusions due to low-powered sample sizes. Hence, we failed to determine if the level of poverty among people receiving CCTs was an important factor for determining impact on ANC service uptake.

One limitation of the evidence incorporated in this review is the use of survey data by the majority of included studies, opening the potential for data bias. We also note the developments in data capture infrastructure, such as smartphones and tablets, that coincide with the decade covered by the included studies, and the potential impact that this had on later studies in terms of enhanced ability to accurately capture data. The included studies varied in quality, ranging from suboptimal study designs to high levels of bias. Three included randomised controlled trials reported high risk of bias on the randomisation process29–31 and two non-randomised studies presented a serious risk of bias on confounding.33 34 The heterogeneity of study design, population and implementation process among the 18 studies hindered us to perform a meta-analysis to generate overall treatment effects of CCTs on ANC. A number of studies did not clearly present the information required for the summary tables. For example, less than half of all studies reported the actual number of ANC visits attended by programme participant populations, rendering it impossible to compare ANC attendance against the WHO-recommended5 number of visits for the majority of included studies. Together, these factors may contribute to the inconclusiveness of results reported in this review.

Given the high heterogeneity identified in this review in relation to CCT impact on ANC uptake across LMICs, there is substantial scope for future research to explore the most important determinants for CCT programme success, failure and inconclusiveness. Complex process evaluations should be employed alongside the implementation of CCT programmes to elucidate the contextual factors that contribute to programme success, including population characteristics, geographical and environmental factors, conditionalities, cointerventions, baseline ANC service uptake and financial allocations attached to demand-side interventions. Study design is an additional important consideration for future CCT programmes, whereby more high-powered randomised controlled trials are required to strengthen the evidence base for whether such programmes are truly impactful from a health perspective.

Conclusion

This systematic review investigated the relationship between CCT programmes and ANC service uptake. These programmes are an alluring instrument for policy makers in LMICs to expand ANC coverage. Our review demonstrated divergent effects of CCTs among the included studies, indicating high context specificity for these programmes to achieve the desired impact of increased ANC service uptake. The global health community, most notably multilateral organisations and donor community, has invested substantially in CCTs during the past few decades. This review highlights that further high-quality, high-powered evidence is required in order to elucidate the true impact of CCT programmes on ANC uptake, with special focus on process evaluation of the barriers, enablers and opportunities for programmatic success.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Downey1L

Contributors: WJ: project administration, research protocol, conceptualisation, title and abstract screening, data extraction, data analysis and synthesis, methodology, grey literature search, background reading, risk of bias assessment, drafting the first manuscript, editing and overall review. LD: research protocol, title and abstract screening, editing of the draft manuscript, overall review, provision of guidance and direction. LED acts as guarantor and is responsible for the overall content in this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patient and public involvement is not applicable as this article is a systematic review of existing evidence. The research question development was informed by the global debate on the effectiveness of CCT programmes.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

This study is a systematic review. All included studies can be retrieved through the reference list. More information regarding the review process including title and abstract screening can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study is a systematic review of already published literature.

References

- 1.United Nations . Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. Available: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3 [Accessed 22 Oct 2021].

- 2.Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J. How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? an overview of the evidence. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2001;15 Suppl 1:1–42. 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.0150s1001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander GR, Korenbrot CC. The role of prenatal care in preventing low birth weight. Future Child 1995;5:103–20. 10.2307/1602510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Antenatal care coverage, data by country. Available: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.ANTENATALCARECOVERAGE4 [Accessed 20 Oct 2021].

- 5.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience, 2016. World Health organization. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 22 Sep 2021]. [PubMed]

- 6.Owusu-Addo E, Renzaho AMN, Smith BJ. Cash transfers and the social determinants of health: a conceptual framework. Health Promot Int 2019;34:e106–18. 10.1093/heapro/day079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N, et al. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;67:1–45. 10.1002/14651858.CD008137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Till SR, Everetts D, Haas DM. Incentives for increasing prenatal care use by women in order toimprove maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015;12:1–29 https://doi.org/10.1002%2F14651858.CD009916.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopalan SS, Mutasa R, Friedman J, et al. Health sector demand-side financial incentives in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review on demand- and Supply-side effects. Soc Sci Med 2014;100:72–83. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter BM, Harrison S, Portela A, et al. The effects of cash transfers and vouchers on the use and quality of maternity care services: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173068–37. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afzal A, Mirza N, Arshad F. Conditional vs unconditional cash transfers: a study of poverty demographics in Pakistan. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 2019;32:3366–83 10.1080/1331677X.2019.1661006 10.1080/1331677X.2019.1661006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Independent Commission for Aid Impact . The effects of DFID’s cash transfer programmes on poverty and vulnerability: An impact review. Independent Commission for Aid Impact, 2017. Available: https://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/ICAI-Review-The-effects-of-DFID%E2%80%99s-cash-transfer-programmes-on-poverty-and-vulnerability-1.pdf [Accessed 20 Nov 2021].

- 13.Elhady GW, Rizk HII, Khairy WA. Impact of cash transfer programs on health status of beneficiary families: a community based study, old Cairo, Egypt. Health Science Journal 2015;10:1–7 https://www.itmedicalteam.pl/articles/impact-of-cash-transfer-programs-on-health-status-of-beneficiary-families-a-community-based-study-old-cairo-egypt-105837.html [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper JE, Benmarhnia T, Koski A, et al. Cash transfer programs have differential effects on health: a review of the literature from low and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med 2020;247:112806–14. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd edition. Cochrane, 2020. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group . Data Collection Checklist. University of Ottawa., 2002. https://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.CENTRAL . Cochrane library advanced search. Available: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/advanced-search [Accessed 21 Jan 2022].

- 18.MEDLINE . National Library of Medicine. Available: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medline/index.html [Accessed 21 Jan 2022].

- 19.Embase . Embase. Available: https://www.embase.com [Accessed 21 Jan 2022].

- 20.Maternity and Infant Care Database. . Maternity and infant care database. Available: https://www.midirs.org/resources/maternity-and-infant-care-mic-database [Accessed 21 Jan 2022].

- 21. EBSCO. Global health. Available: https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/global-health [Accessed 21 Jan 2022].

- 22. Covidence. Better systematic review management. Available: https://www.covidence.org/ [Accessed 21 Jan 2022].

- 23.Tawfik GM, Dila KAS, Mohamed MYF, et al. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop Med Health 2019;47:1–9. 10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Inflation Calculator . Inflation calculator. Available: https://www.usinflationcalculator.com [Accessed 12 Feb 2022].

- 25.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:1–9 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Triyana M. Do health care providers respond to Demand-Side incentives? Evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2016;8:255–88 10.1257/pol.20140048 10.1257/pol.20140048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber SL, Gertler PJ. Empowering women: how Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme raised prenatal care quality and birth weight. J Dev Effect 2010;2:51–73. 10.1080/19439341003592630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okeke EN. Money and my mind: maternal cash transfers and mental health. Health Econ 2021;30:2879–904. 10.1002/hec.4398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okeke EN, Abubakar IS. Healthcare at the beginning of life and child survival: evidence from a cash transfer experiment in Nigeria. J Dev Econ 2020;143:102426–7. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanhuyse F, Stirrup O, Odhiambo A, et al. Effectiveness of conditional cash transfers (Afya credits incentive) to retain women in the continuum of care during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period in Kenya: a cluster-randomised trial. BMJ Open 2022;12:e055921–12. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grépin KA, Habyarimana J, Jack W. Cash on delivery: results of a randomised experiment to promote maternal health care in Kenya. J Health Econ 2019;65:15–30 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.12.001 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joshi S, Sivaram A. Does it Pay to Deliver? An Evaluation of India’s Safe Motherhood Program. World Dev. In Press 2014;64:434–47. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okoli U, Morris L, Oshin A, et al. Conditional cash transfer schemes in Nigeria: potential gains for maternal and child health service uptake in a national pilot programme. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:1–13. 10.1186/s12884-014-0408-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edmond KM, Foshanji AI, Naziri M, et al. Conditional cash transfers to improve use of health facilities by mothers and newborns in conflict affected countries, a prospective population based intervention study from Afghanistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:1–18 10.1186/s12884-019-2327-2 10.1186/s12884-019-2327-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Brauw A, Peterman A. Can conditional cash transfers improve maternal health care? Evidence from El Salvador's Comunidades Solidarias Rurales program. Health Econ 2020;29:700–15. 10.1002/hec.4012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kandpal E, Alderman H, Friedman J, et al. A conditional cash transfer program in the Philippines reduces severe stunting. J Nutr 2016;146:1793–800. 10.3945/jn.116.233684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kusuma D, Cohen J, McConnell M, et al. Can cash transfers improve determinants of maternal mortality? Evidence from the household and community programs in Indonesia. Soc Sci Med 2016;163:10–20. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powell-Jackson T, Mazumdar S, Mills A. Financial incentives in health: new evidence from India's Janani Suraksha Yojana. J Health Econ 2015;43:154–69. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chakrabarti S, Pan A, Singh P. Maternal and child health benefits of the Mamata conditional cash transfer program in Odisha, India. J Nutr 2021;151:2271–81 10.1093/jn/nxab129 10.1093/jn/nxab129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aizawa T. Does the expanded eligibility of conditional cash transfers enhance healthcare use among socio-economically disadvantaged mothers in India? J Dev Effect 2020;12:164–86. 10.1080/19439342.2020.1773899 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Díaz J-J, Saldarriaga V. Encouraging use of prenatal care through conditional cash transfers: evidence from JUNTOS in Peru. Health Econ 2019;28:1099–113 10.1002/hec.3919 10.1002/hec.3919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, et al. India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet 2010;375:2009–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell-Jackson T, Neupane BD, Tiwari S. The impact of Nepal’s national incentive programme to promote safe delivery in the district of Makwanpur. Innovations in Health System Finance in Developing and Transitional Economies 2009;21:221–49 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19791705/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Debnath S. Improving maternal health using incentives for mothers and health care workers: evidence from India. Econ Dev Cult Change 2021;69:685–725. 10.1086/703083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thornton RL. The demand for, and impact of, learning HIV status. Am Econ Rev 2008;98:1829–63 https://dx.doi.org/10.1257%2Faer.98.5.1829 10.1257/aer.98.5.1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Attanasio OP, Oppedisano V, Vera-Hernández M. Should cash transfers be conditional? Conditionality, preventive care, and health outcomes. Am Econ J Appl Econ 2015;7:35–52 https://www.jstor.org/stable/24739033 10.1257/app.20130126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Bank . GDP per capita (current US$). Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD [Accessed 16 Oct 2021].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-064673supp001.pdf (275.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

In line with the EPOC criteria, studies with incomplete or opaque data were not incorporated in the final selection.16 A good example are studies with missing control variables. Authors were contacted for further inquiry as well. Studies with self-reported data are considered, contrary to the EPOC criteria, as filtering out articles reporting on survey-related data obtained by interviewing people would result in little evidence.

This study is a systematic review. All included studies can be retrieved through the reference list. More information regarding the review process including title and abstract screening can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.