Abstract

Microfluidics has recently emerged as a powerful tool in generation of submillimeter-sized cell aggregates capable of performing tissue-specific functions, so-called microtissues, for applications in drug testing, regenerative medicine, and cell therapies. In this work, we review the most recent advances in the field, with particular focus on the formulation of cell-encapsulating microgels of small “dimensionalities”: “0D” (particles), “1D” (fibers), “2D” (sheets), etc., and with nontrivial internal topologies, typically consisting of multiple compartments loaded with different types of cells and/or biopolymers. Such structures, which we refer to as topological hydrogels or topological microgels (examples including core–shell or Janus microbeads and microfibers, hollow or porous microstructures, or granular hydrogels) can be precisely tailored with high reproducibility and throughput by using microfluidics and used to provide controlled “initial conditions” for cell proliferation and maturation into functional tissue-like microstructures. Microfluidic methods of formulation of topological biomaterials have enabled significant progress in engineering of miniature tissues and organs, such as pancreas, liver, muscle, bone, heart, neural tissue, or vasculature, as well as in fabrication of tailored microenvironments for stem-cell expansion and differentiation, or in cancer modeling, including generation of vascularized tumors for personalized drug testing. We review the available microfluidic fabrication methods by exploiting various cross-linking mechanisms and various routes toward compartmentalization and critically discuss the available tissue-specific applications. Finally, we list the remaining challenges such as simplification of the microfluidic workflow for its widespread use in biomedical research, bench-to-bedside transition including production upscaling, further in vivo validation, generation of more precise organ-like models, as well as incorporation of induced pluripotent stem cells as a step toward clinical applications.

1. Introduction

Conventional “2D” cell cultures, relying on the use of a monolayer of cells cultured at a bottom of a culture flask, have been a standard in biology research, vaccine production, and drug testing for over a century. However, interaction of cells with flat, stiff, typically plastic substrates in general leads to nonphysiological cell responses and results in cell phenotypes which do not reproduce those encountered in vivo.1 To provide a more physiological microenvironment, in particular facilitating three-dimensional arrangement of cells and/or providing a three-dimensional (“3D”) support mimicking the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the native tissue,2 the so-called “3D” cell culture techniques have been developed.1 Those techniques can be in general categorized into those relying (i) on the use of nonadhesive substrates promoting cell–cell interactions and resulting in aggregation of cells into spheroids without an external hydrogel support, or (ii) on embedding the cells within the ECM-like hydrogel matrix, which provides the external support and leads to more physiological cell and tissue morphologies. The most recent developments in the 3D cell culture succeeded in integration of the two approaches via the use of microscopic hydrogel (microgel) scaffolds capable of providing both a controlled degree of confinement as well as highly biomimetic local 3D microenvironment,3−6 allowing for generation of reproducible, yet biologically relevant microtissues.

The areas of particularly rapid technological development in 3D cell culture include new strategies of formulation of biomaterials at the scale typical of cell aggregates or tissues at the early stages of development, i.e., at the scale of the order of 100–1000 um. Such mesoscale biomaterials could serve as scaffolds for production of microtissues in vitro, i.e., cell aggregates capable of performing basic physiological functions typical of a given tissue. Besides basic tissue-biological research, microtissues could also serve high-throughput drug testing, as microscopic living tissue “probes”, to complement or eventually replace animal models. Further, custom-tailored microtissues, generated with high reproducibility and throughput, could also be used as building blocks of more complex living constructs. The general strategy of the latter “modular” approach to tissue engineering consists of arranging the distinct hydrogel compartments, loaded with different types of cells, into a biomimetic 3D scaffold.3,4 Such structures provide well-defined “initial conditions” for tissue maturation, that is, for cell proliferation and differentiation into a functional tissue. Importantly, compartmentalization allows not only for 3D cell patterning7 but also 3D biopolymer patterning,4 where the latter can be used to impose varying physicochemical cues including local gradients in matrix stiffness and/or molecular protein or peptide content. In particular, the composition of the matrix can be engineered to locally promote or suppress cell–matrix interaction and thus control morphology of the ensuing microtissues. In terms of applications, the recent advancements in hydrogel microfabrication methods8−17 have opened new perspectives in regenerative medicine,18,19 personalized drug testing,20−22 as well as in basic cell- and tissue physiology research,2,21 including cancer research.23−28

In this review, we focus on the most recent developments in microfluidics-assisted formulation of biomaterials, in particular on those with nontrivial internal architecture, typically consisting of multiple distinct compartments.8,16−18,29,30 We use the term “microfluidics” to describe a set of techniques aimed at developing of high-level of control over tiny liquid volumes, typically nano- or even picoliter volumes, at submillimeter length scale. In particular, microfluidics can be used to disperse hydrogel precursor solutions into monodisperse droplets or extrude them into stable jets, which subsequently solidify, either spontaneously or via externally triggered cross-linking reaction, into hydrogel microparticles,8,9,13,14,18,31−35 microfibers,36−40 or more general “microgels”. The laminar (nonturbulent) flow conditions associated with small dimensions of the microchannels lead to reproducibility of droplet and jet morphologies as well as facilitate precise manipulation of the microscopic hydrogel liquid compartments, e.g., their on-chip merging or splitting.41 In particular, controlled coalescence of microfluidic droplets or jets containing different hydrogel precursors allows reproducible generation of compartmentalized hydrogel microstructures. Microfluidics can be used to formulate compartmentalized hydrogels of various “dimensionalities”15 ranging from “0D” particles and “1D” fibers to “1.5D” ribbons. Furthermore, the particles or fibers can be assembled into larger architectures11,42 such as granular, porous, or woven “2D” sheets or even densely packed, stacked, or bundled granular “3D” architectures.43 It is noteworthy that granular hydrogels can also be used as injectable biomaterials for tissue regeneration, wound healing, or drug delivery.34,43

Some of the most common examples of the internally compartmentalized microgels include “0D” core–shell structures (microcapsules)32,44 with a soft core and a rigid shell, where the shell provides a physical barrier, protecting the cells against the external disturbing factors such as shear forces or interactions with cells outside of the microstructure. The confined microenvironment additionally expedites cell aggregation and, in many cases, promotes cell differentiation, which in turn facilitates the development of tissue-specific functions. In bioreactor cultures involving multiple microtissues, the presence of protective shells prevents excessive cell aggregation in the cores and as such limits the risk of hypoxia. Core–shell “1D” structures (microfibers) can also serve as scaffolds for cell expansion.40 In addition, the elongated morphology can be exploited in culturing of tissues of fiber-like morphology such as muscles or nerves.

Overall, the large-scale production of tailorable “0D” or “1D” microgels opens new perspectives in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, in particular in restoration of tissues such as muscle,45−47 heart,47,48 bone,49 or neural tissue50 or in cell-based therapies for treatment of diseases such as diabetes51 or infertility.52

Recently, microfluidic technologies have also been applied to culture macroscopic amounts of cells for the use as food products, e.g., cultured meat.53

As a complement to the already available large body of literature considering microfluidic formulation of microgels, in this review, we focus on classifying various possible routes toward their compartmentalization and self-assembly, including generation of structures of different topologies and dimensionalities. In particular, we establish that the available microfluidic techniques of formulation of compartmentalized architectures exploit either (i) the self-assembled equilibrium liquid architectures, typically consisting of multiple immiscible liquid segment, or (ii) transient nonequilibrium architectures consisting of multiple miscible segments quenched via rapid cross-linking reactions. In addition, we systematically review the most recent tissue-specific applications of the topological microstructures encompassing multiple types of microtissues, including miniature pancreas, liver, muscle, bone, heart, neural tissue, vasculature, as well as stem cell spheroids and microtumors. In each case, we highlight biological relevance of microcompartmentalization and its role in providing the optimal conditions for tissue maturation as signified by cell differentiation and/or secretion of tissue-specific markers.

Our paper is structured as follows. We start with a general classification of the available microgel topologies and dimensionalities in section 2, followed by a short review of the different types of hydrogels used in microfluidic formulations in section 3. Next, we turn to a detailed description of the available microfluidic methods of fabrication of the topological hydrogel microstructures in section 4 and the different types of biomedical applications in section 5, including a detailed review of most recent tissue-specific applications in section 5.2. Finally, we discuss the remaining challenges and the emerging commercial microtissue-based applications in section 6. For convenience of the reader, the flow of information is also schematically displayed in Figure 1.

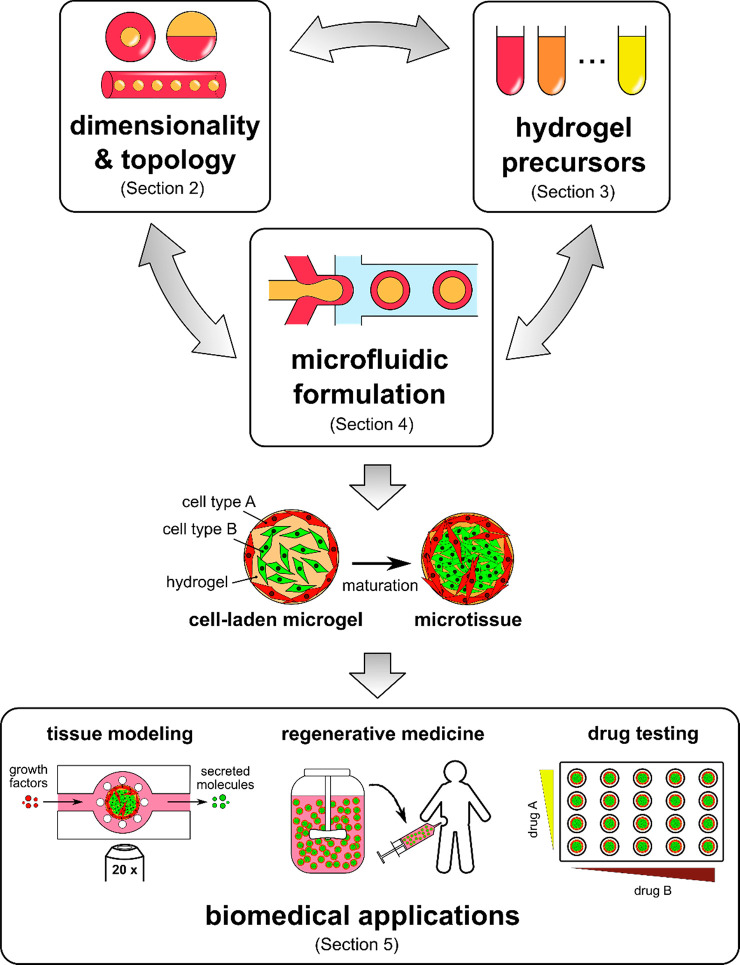

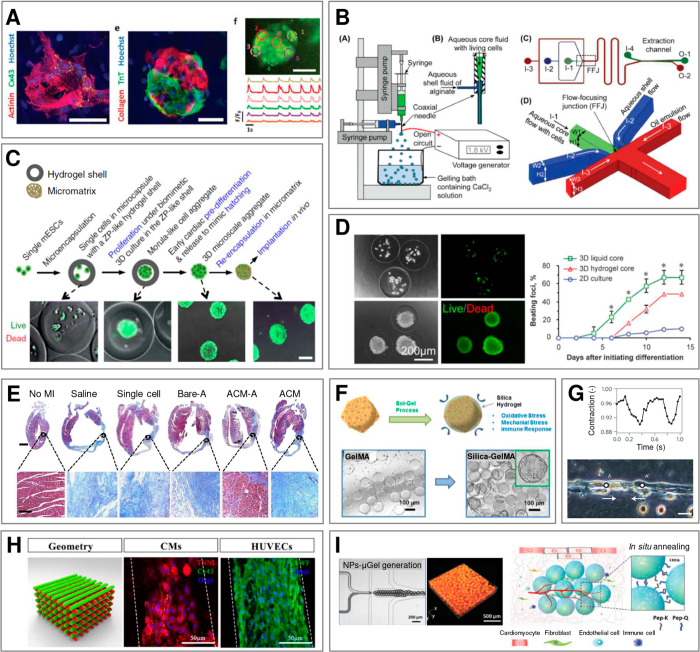

Figure 1.

Main subjects of interest in microfluidics-assisted microtissue engineering (with indicated corresponding section numbers in this review): (i) experimentally achievable microgel topologies and dimensionalities, (ii) properties of different hydrogel biomaterials, (iii) microfluidic formulation strategies, and their (iv) biomedical applications. Note that the desired final topology of a microgel and the choice of the type of the hydrogel often dictate the choice of a particular formulation strategy. The generated topological structures with embedded cells, so-called microtissues, may serve as (i) reproducible in vitro tissue models, (ii) cell sources for tissue regeneration and cell therapies, or (iii) as tissue “probes” for high-throughput drug testing.

2. General Classification of Microgel Dimensionalities and Topologies

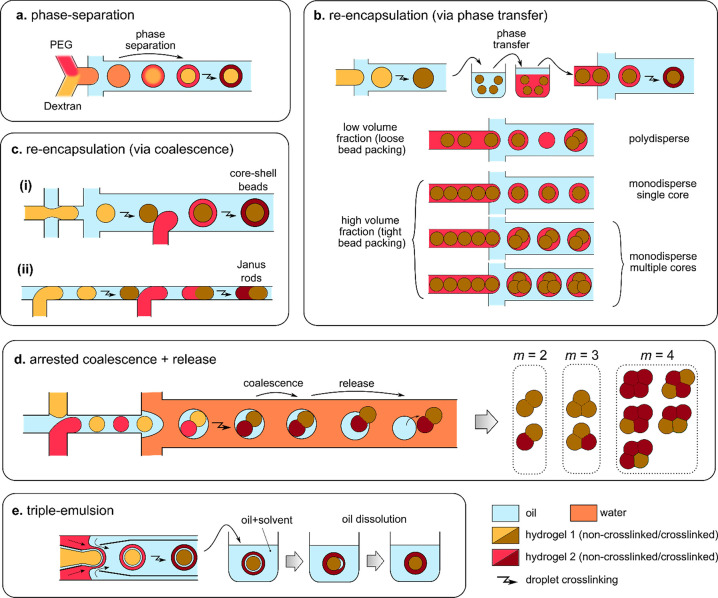

Rapid progress in microfluidics-assisted fabrication of microgels in the last couple of years has brought a rich variety of the available hydrogel microstructures. In this section, we provide an overview of the different hydrogel microarchitectures achievable using microfluidics. Fabrication of such structures (Figure 2) exploits a variety of flow patterns and cross-linking strategies in accordance with the type of biopolymers employed. We start with discussing the basic topological constraints which yield the physically possible architectures without going into details of their microfabrication processes, which we later discuss in section 3.

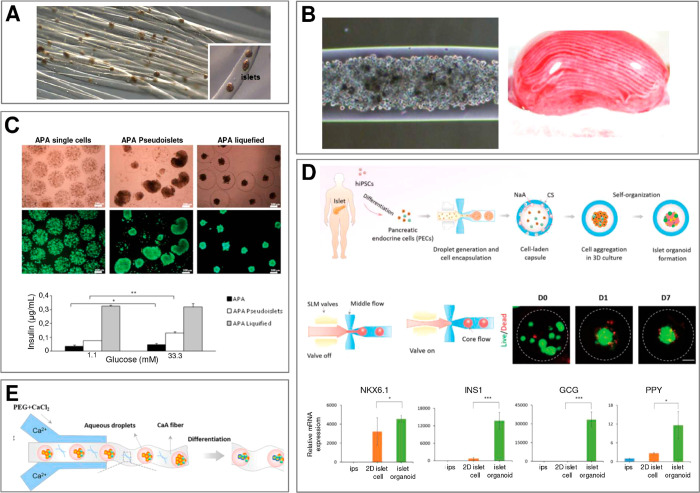

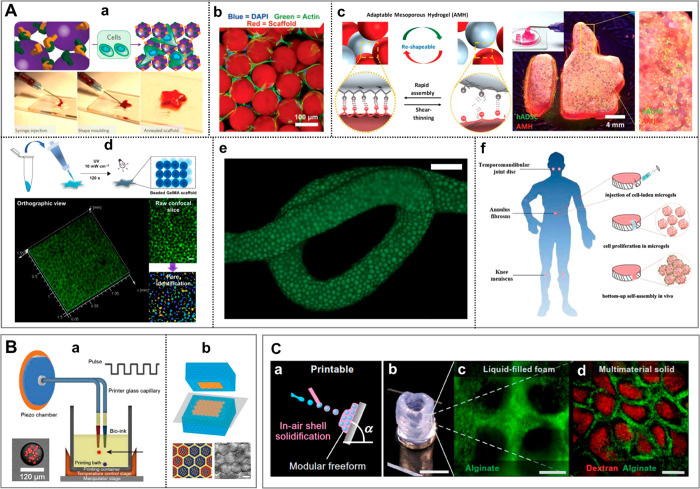

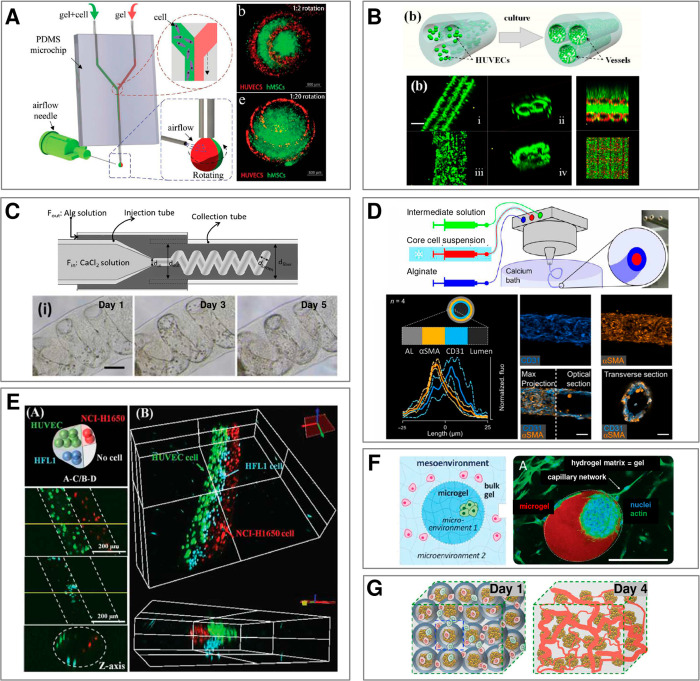

Figure 2.

The variety of microgel structures for N = 2. We classify the structures in terms of overall topology (“engulfing” vs “Janus”) and dimensionality (0D, 1D, 2D, 3D) for the case of two (N = 2) different hydrogel phases A and B (or a hydrogel and another immiscible phase such as oil or gas) suspended in the external phase C (typically cell culture medium). (A) (a–c) pNIPAAM core–shell beads. Scale bars 100 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (63). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society. (d–f) ETPTA, gelatin, and alginate–chitosan porous beads, respectively. Scale bars 200 μm. Adapted with permission from refs (64−66), respectively. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society, 2013 Wiley, and 2018 Wiley, respectively. (g–h) Cross-sectional view of alginate core–shell fibers and hollow fibers, respectively. Scale bars 200 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (67). Copyright 2018 Nature Publishing Group. (i) Alginate fibers engulfing aqueous droplets. Scale bar 300 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (68). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. (j) Cross-section of an alginate ribbon with multiple hollow cores. Scale bar 100 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (69). Copyright 2016 Wiley. (k) Alginate sheet. Scale bar 2 mm. Adapted with permission from ref (70). Copyright 2018 Royal Society of Chemistry. (l) Fluorescent alginate sheet. Scale bar 500 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (59). Copyright 2012 Wiley. (m) Porous alginate membrane. Scale bar 100 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (71). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. (n) Close-packed norbornene-modified hyaluronic acid (NorHA) microbeads suspended in PBS. Scale bar 200 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (72). Copyright 2019 Wiley. (o) Porous gelatin scaffold with gradient in pore size. Scale bar 500 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (54). Copyright 2019 Wiley. (p) Extrusion 3D-printed alginate fibers. Scale bar 500 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (73). Copyright 2017 Elsevier. (q) Cross-section of wet-spun cell-laden alginate fibers. Scale bar 50 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (74). Copyright 2018 Elsevier. (B) (a–d) Alginate beads. Scale bars 500, 100, 200, and 200 μm, respectively. Adapted with permission from refs (75−78), respectively. Copyright 2015 Royal Society of Chemistry, 2018 Wiley, 2013 American Institute of Physics, and 2020 Wiley, respectively. (e–g) Alginate Janus fibers. Scale bars 200 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (79 and 80). Copyright 2020 Wiley and 2014 Wiley. (h) GelMa fiber. Scale bar 1 mm. Adapted with permission from ref (81). Copyright 2019 The Royal Society of Chemistry. (i) Alginate fiber. Scale bar 800 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (82). Copyright 2011 Nature Publishing Group. (j,k) Alginate sheets. Scale bars 500 μm. Adapted with permission from refs (59 and 83), respectively. Copyright 2012 Wiley and 2013 Elsevier, respectively. (l) Granular sheet made of GelMa microrods arranged into a macroscale stripe pattern. Scale bar 2 mm. Adapted with permission from ref (84). Copyright 2017 Wiley. (m) pNIPAAM granular sheet. Scale bar 500 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (85). Copyright 2020 Nature. (n,o) Aginate and PEGDA sheets, respectively. Scale bars 500 μm. Adapted with permission from refs (59, 86, and 87), respectively. Copyright 2012 Wiley and 2016 American Association for the Advancement of Science. (p) 3D scaffold made of annealed PEG beads. Scale bar 200 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (50). Copyright 2019 Wiley. (q) 3D-printed hydrogel droplets stabilized by lipids. Scale bar 100 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (88). Copyright 2021 The Authors. (r) Rolled alginate sheet. Scale bar 500 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (59). Copyright 2012 Wiley. (s) Stacked alginate sheets. Scale bar 500 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (59). Copyright 2012 Wiley.

We classify the compartmentalized hydrogel microstructures according to their (i) “dimensionality” and (ii) topology. By “dimensionality”, we understand the overall shape of a microstructure determined by its dimensions in all directions Dx, Dy, and Dz relative to the size a of a single compartment.15,17 Accordingly, we may distinguish (i) “0D” architectures,8,13,14,18,32 i.e., compact structures, strongly confined in all directions, i.e., with Dx ∼ Dy ∼ Dz ∼ a (Figure 2A(a–f),B(a–d)). (ii) “1D” architectures,36,37,39,54,55 structures elongated in one direction, i.e., with Dz ≫ a, and Dx ∼ Dy ∼ a (Figure 2A(g–i),B(e–i)). (iii) “2D” architectures, i.e., planar structures with Dy ≫ a, Dz ≫ a and Dx ∼ a (Figure 2A(j–m),B(j–o)), as well as (iv) “3D” architectures, i.e., bulk structures4,43 with Dx ≫ a, Dy ≫ a, and Dz ≫ a (Figure 2A(n–q),B(p–s)). By topology of the structures we understand the type of arrangement of the compartments, in particular, their connectivity. For the purpose of our classification, we employ an analogy to multiple emulsions, i.e., to the case of droplets built of multiple immiscible liquid segments.56 In the case with N = 2 liquid or hydrogel compartments, say A and B, suspended in the third external fluid phase, C (typically cell culture medium or oil), there are in general two different possible topologies that can form.56−58 One can distinguish (i) the engulfing topology, A/B/C, in which phase B completely engulfs phase A, such that only phase B has a direct contact with the external phase C (Figure 2A(a,g) and (ii) the Janus topology, (A–B)/C, in which both phases have a direct contact with the external phase as well as with each other (Figure 2B(a,e)). We note that the type of topology does not necessarily determine the dimensionality of the structure (nor vice versa): both the engulfing and the Janus topologies can be realized either in the case of “0D” (Figure 2A(a–f),B(a–d)) as well as “1D” structures (Figure 2A(g–i),B(e–i)) or higher-dimensional “2D” and “3D” structures (Figure 2A(j–q),B(j–s)). The complexity of the structures rapidly increases upon increasing the numbers mA or mB of compartments of the types A or B, respectively. In such a way, one can achieve, for example, the engulfing core–shell topologies with multiple cores in a single shell, (A1, . . .,AmA)/B/C (Figure 2A(b–f),(h–q)) or multi-Janus topologies (A1 – B1 – ... – AmA – BmB)/C (Figure 2B(b–d),(f–s)).

It is noteworthy that, in the case “1D”, besides the overall topology of the structure, one can also distinguish two different types of the internal patterning: either transversal, with compartments arranged across the fiber, or longitudinal, with compartments arranged along the fiber. In the former case, the pattern is translationally invariant along the fiber. On the contrary, in the latter case, the cross-section varies according to the longitudinal distribution of the compartments. Interestingly, this latter type of structures can be conveniently used to encode information.59,60 Actually, the most efficient information coders seem to be the “1.5D” ribbon-like structures which can be patterned in both longitudinal and transverse directions;59 see also section 4.5.4. Such coded fibers or ribbons could be used to “label” multiple microtissues sequentially embedded in the structure for the purpose of their identification, e.g., in a high-throughput screening assay.

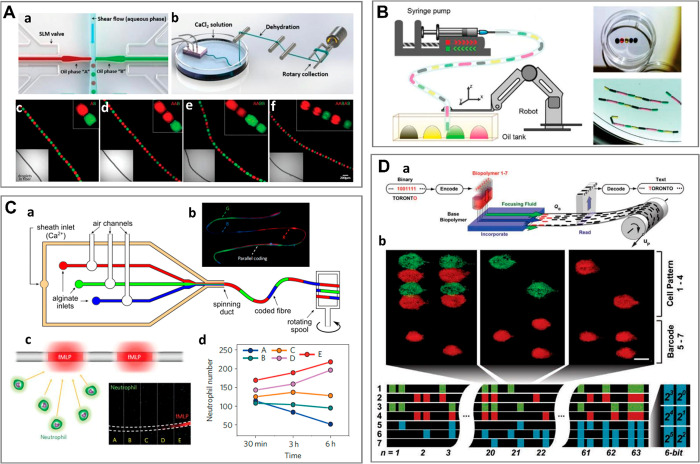

To conclude the topological considerations, we note that, in general, the number n of available topologies rapidly grows with the number of compartments m as well as with the number of different hydrogel species N (in particular, one must have m ≥ N). In the simplest case m = N, for N = 2, we have n = 2 basic topologies (“engulfing” and “Janus”), while in the case N = 3, the number of such basic topologies increases to n = 7, all of them explicitly listed in Figure 3 (as demonstrated recently,61 in multiphase liquid architectures n can be calculated based on graph-theoretical considerations). In fact, all of those topologies have been already experimentally demonstrated using microfluidics. At higher N, the available topologies have not been much explored, with some exceptions.62 In general, it is clear that with increasing N, the complexity of the available microstructures rapidly becomes insurmountable. Apparently, the case N = 2 represents a reasonable trade-off between complexity and experimental feasibility and, indeed, the most of the available demonstrations involve two different types of hydrogel compartments. In fact, the most recent research efforts tend to focus mostly on developing control over the relative spatial arrangement of the compartments and on tuning of their physicochemical properties rather than on further increasing N.

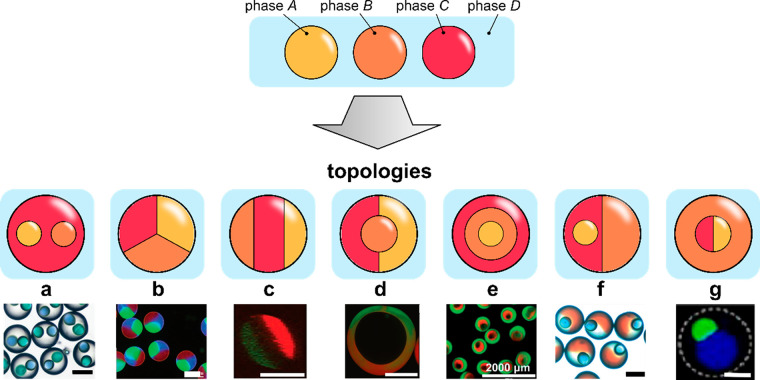

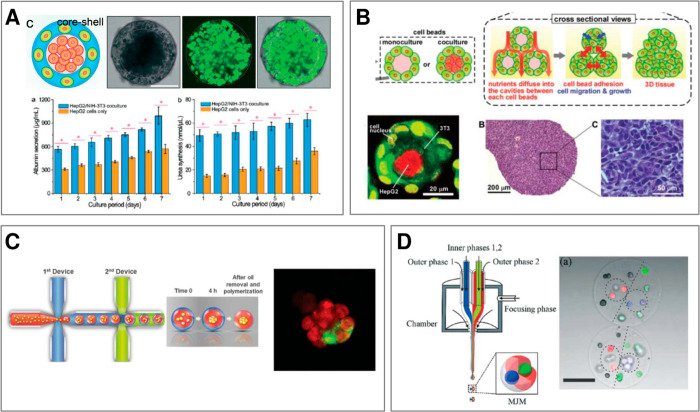

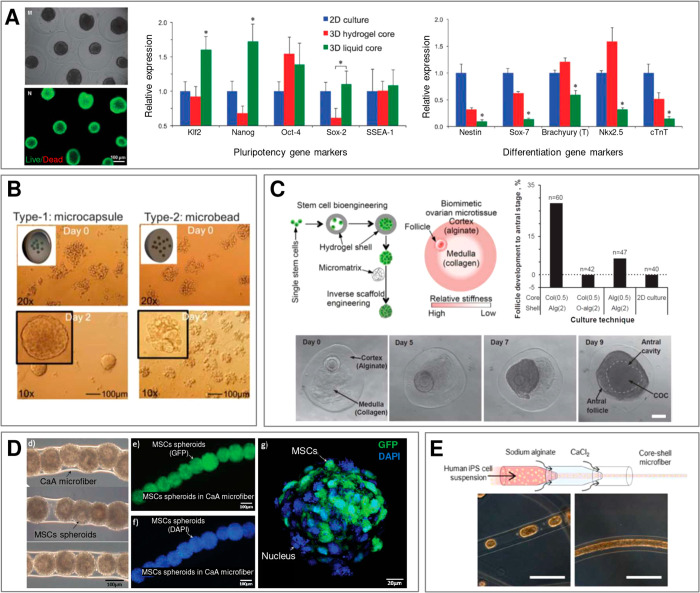

Figure 3.

A complete list of distinct topologies for N = 3. (a) PVA cores in trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) shell. Scale bar 200 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (89). Copyright 2017 Royal Chemical Society. (b) Alginate beads. Scale bar 100 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (62). Copyright 2012 Wiley. (c) Cross-section of an alginate fiber with three compartments. Scale bar 200 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (80). Copyright 2020 The Authors. (d) Oil core in a two-compartment alginate shell. Scale bar 100 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (90). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society. (e) Alginate core–shell–shell beads. Scale bar 2 mm. Adapted with permission from ref (75). Copyright 2015 Royal Society of Chemistry. (f) Janus trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) bead with embedded single oil core. Scale bar 200 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (89). Copyright 2017 Royal Chemical Society. (g) Janus-in-shell morphology obtained using aqueous three-phase droplet (dextran, PEG, PVA) suspended in an external oil phase. Scale bar 100 μm. Adapted with permission from ref (91). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

3. Hydrogels as ECM-Mimics in Microtissue Engineering

Hydrogels consist of a network of cross-linked hydrophilic polymer chains. Due to their 3D mesh-like nanostructure, hydrogels are capable of absorbing large amounts of water, a feature which, together with other properties, such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, nanoporosity, and adjustable mechanical properties, make them perfect candidates for tissue-engineering applications. To properly mimic the extracellular matrix of a given tissue, the mechanical and biochemical properties of a hydrogel, such as the Young’s modulus or the presence of molecular motifs promoting cell adhesion, e.g., arginylglycylaspartic acid, the so-called RGD peptide motif, need to be carefully adjusted considering the specific type of cultured cells. In the choice of the hydrogel (and its cross-linking method), it should be taken into account that some of the hydrogels (e.g., polyacrylamides) or chemical cross-linkers (e.g., glutaraldehyde) are cytotoxic,92 which strongly limits their applicability in biomaterial formulation. Also, it should be considered that, e.g., free radicals generated during UV-triggered cross-linking, as well as UV light itself, may cause cell damage.93 Biopolymers most commonly used in preparation of microgels for tissue engineering include (i) those of natural origin such as polysaccharides, e.g., agarose, hyaluronic acid, chitosan or calcium alginate, or protein-based such as gelatin, collagen, fibrin, or Matrigel or other types of decellularized matrices (dECM), (ii) partially synthetic ones such as gelatin methacryloyl (GelMa), or (iii) fully synthetic ones, e.g., poly(ethylene glycols) (PEGs) and their derivatives.

In this section, we address the mechanical properties of the hydrogels most commonly used in microfluidics-assisted 3D cell culture. We discuss cell–hydrogel interactions and biodegradability of hydrogels as a general prerequisite for their applications in tissue engineering, and in particular their capability of mimicking the ECM of a given tissue.

3.1. Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels in Microtissue Engineering Applications

Mechanical properties of hydrogels forming 3D cell culture scaffolds not only determine the long-term stability of the scaffold but also directly impact the behavior of the embedded cells via mechano-transduction, i.e., biochemical signaling induced by external mechanical cues.94 For example, stem cells tend to retain higher levels of pluripotency when embedded in softer hydrogels, a feature recently exploited in generation of stem-cell laden core–shell capsules with soft-hydrogel cores.95

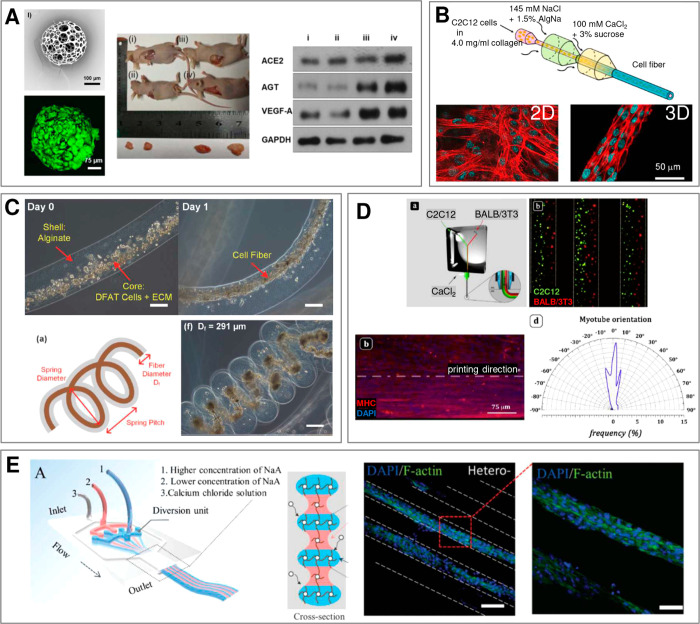

Hydrogel mechanical properties are typically characterized by shear modulus (G) or elastic modulus (E) also called the Young’s modulus, which are both related to each other vis the material’s Poisson’s ratio (the latter typically in the range 0.45–0.5). Moduli of hydrogels can be tuned by changing various parameters, such as cross-linker type and concentration, as well as cross-linking time,96 which all impact the cross-link density defined as the number of cross-links per polymer chain.97 In particular, increasing the concentration of polymer leads to higher Young’s moduli of a cross-linked hydrogel.98 In biomimetic matrices, the mechanical properties of the matrix should match the properties of the native tissue or the native ECM, depending on the applied biomimetic strategy. A detailed comparison between the Young’s moduli of various tissues and various hydrogels is summarized in Figure 4. Tissues such as cortex,99 liver,100,101 pancreas,102,103 vasculature,104 muscle,105 and spinal cord99 with elastic moduli in the range 101–104 Pa can be classified as soft and therefore are usually cultured in soft hydrogels such as Matrigel, GelMa, gelatin, collagen, fibrin, dECM, or softer versions of alginate. Those hydrogels are also frequently applied in stem cell culture because the soft-solid microenvironment promotes spheroid formation and facilitates direct cell–cell interactions, which in turn leads to enhanced pluripotency.95,106 Interestingly, stem cells aggregating inside the soft core of a core–shell microcapsule47,95,106−114 tend to retain even higher levels of pluripotency as compared to spheroids cultured using conventional methods (nonadhesive substrates).107 Finally, soft hydrogels also provide optimal conditions for 3D culture of microtumors. Microencapsulation offers a unique tool for investigation of the impact of the mechanical properties of ECM on tumor progression. For example, Agarwal et al. used core–shell capsules with cancer cells contained in the soft collagen core115 to demonstrate that matrix stiffness alone (changed via doping collagen with alginate) impacts gene expression in breast cancer cells.

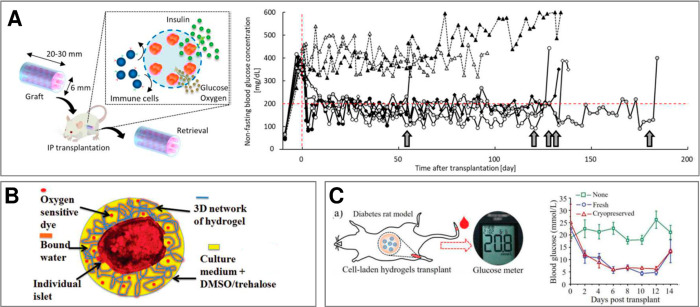

Figure 4.

Tissues vs biomaterials: comparison of mechanical properties. Young’s moduli of various tissues (upper panel) and of the corresponding biomaterials most commonly applied in tissue engineering (lower panel). (*) Data for hydrogels cross-linked in nonphysiological conditions; (a) data for microgels.

Tissues such as nerves,116 large vessels and arteries,117 as well as cartilage118,119 with moduli in the range 105–107 Pa can be classified as medium in terms of stiffness. Accordingly, biomimetic approaches involving these types of tissues require stiffer scaffolds which can be realized using hydrogels such as alginate, agarose, hyaluronic acid, PEG, or chitosan. Those biopolymers are frequently applied in bioprinting and general biofabrication of mesoscopic (milimeter- to centimeter-sized) tissue-like constructs19 but also used in generation of core–shell microstructures where they optimally serve as the shell phase. Mechanically stable alginate shells have been used in high-throughput microfluidic fabrication of stem cell spheroids47,95,106−112 and have also been shown to improve their cryopreservation.120,121

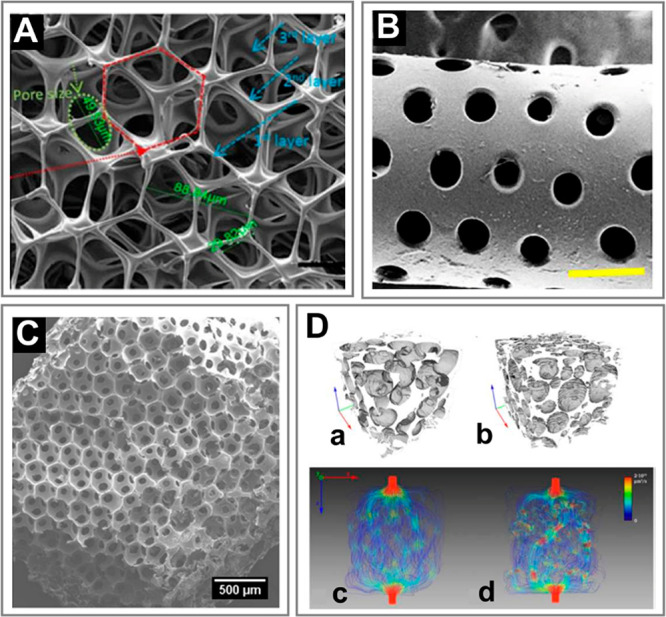

Tissues with the highest Young’s moduli, such as tendon and bone, can be classified as hard tissues. The moduli can reach even 1010 Pa in the case of cortical bone,122 up to 108 Pa in case of cancellous bone,123 and up to 109 Pa in case of tendon (upon stretching).124 It is worth mentioning that tendon is a strongly anisotropic tissue built of densely packed coaligned collagen fibers. It can be considered a hard tissue under stretching along the fiber direction,125 whereas upon compression or deformation in other directions, it behaves more as a medium-soft tissue.126 Even though the stiffness of manufactured materials such as those based on collagen fibers can be matched, e.g., with the stiffness of the tendon, such types of materials are not suitable as ECM mimics. Nevertheless, stiff biomaterials such as chitosan66 or ceramic scaffolds127,128 can be used to provide rigidity and stability to the engineered microtissues, e.g., necessary for their implantation in vivo.128 The most common strategy in regeneration of bone or cartilage tissue is the use of porous scaffolds. Rigid, porous structures warrant stability to the engineered constructs while also facilitating cell and nutrient infiltration into the scaffold.

Finally, we note that, in principle, the stiffness of a hydrogel sample may depend on the size of the sample. For example, the finite size may impact the cross-linking reaction, in particular, lead to a cross-link density gradient at the interface.129 Accordingly, in the case of microgels, it is desirable to measure the Young’s modulus directly. Several methods have been exploited for this purpose.130 For example, AFM-based nanoindentation was used to measure local mechanical properties of hydrogels at even nanometric scales, e.g., to detect local stiffness gradients at a hydrogel–hydrogel interface131 as well as to directly measure Young’s moduli of microgels.132 Another method, so-called real-time deformability cytometry, developed originally for cells,133,134 was used to extract the stiffness of microgels from the measurements of their deformation under viscous forces.135,136 Finally, elasticity of microgels have been also extracted from their static deformation under capillary forces emerging upon encapsulation of two (or more) microbeads inside an aqueous droplet.137 Importantly, the directly measured microgel stiffnesses typically remained of the same order of magnitude as those measured for bulk samples using conventional methods.137 From these latter results, one may conclude that, at least to the order of magnitude, the available “bulk” mechanical data can be used to approximate mechanical properties of the microgels.

3.2. Cell–Hydrogel Interactions in 3D Cell Culture

Cellular adhesion and proliferation are necessary to grow a healthy tissue. Some of the most important molecular factors that promote cell adhesion are the tripeptide sequence Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) and fibronectin, whereas cell growth and proliferation are in general regulated by various types of growth factors. Growth factors can only be found in a small group of hydrogels of natural origin such as Matrigel or dECM, whereas cell adhesion motifs are naturally present also in chitosan, collagen, fibrin, gelatin, and GelMa but not in agarose, alginate, hyaluronic acid, or PEG. In the latter cases, cell adhesion can be promoted via proper chemical functionalization of the hydrogel.109,138,139

The required degree of cellular adhesion depends on the type of tissue. Tissues that tend to spread and form interconnected networks such as vasculature, in particular blood capillaries, typically rely on interaction with the surrounding ECM,140 which leads to formation of branched finger-like structures.141−143 Accordingly, hydrogels of choice in vascular tissue engineering include those which not only promote cell adhesion but are also soft enough to support cell migration. Indeed, the matrices frequently used in vascular tissue engineering include soft hydrogels such as fibrin141,143 as well as UV-cross-linkable PEG-fibrinogen,144 or RGD-functionalized PEGs.142 In 3D cultures aimed at generation of compact cell aggregates such as spheroids or organoids, cellular adhesion to the matrix should be minimized. In such types of applications, soft or even liquid-like microenvironments are advantageous.

3.3. Biodegradability of Microhydrogels in Vitro and in Vivo

Biodegradability of hydrogel scaffolds is one of the central issues in tissue engineering. In applications in which the hydrogel acts as a temporary support, the scaffold should gradually degrade as the tissue becomes mature. In such a cases, the degradation rate of the hydrogel needs to be matched with the rate of tissue development, which in turn depends on the type of tissue. Degradation of hydrogels is usually caused by one of two mechanisms: enzymolysis or hydrolysis. Enzymatic degradation is a local phenomenon, while hydrolysis occurs in the entire volume of the hydrogel due to the presence of unstable chemical bonds.145 Some hydrogels can undergo degradation in vivo without the need of further modification. Those include chitosan,146 collagen,147 dECM,148 fibrin,149 gelatin,147 GelMa,84 hyaluronic acid,150 and Matrigel.151 If their degradation rate is too fast, it can be slowed down by, e.g., introducing different cross-linking methods152 or adjusting cross-linking density.153 Several hydrogels such as agarose, alginate, and PEG do not undergo biodegradation in vivo. Various methods can be applied in order to enhance degradation such as modifications within polymer chains, e.g., oxidation of the alginate chain,52 incorporation of enzyme-sensitive molecules,154 or copolymerization with a biodegradable polymer.155

In in vivo applications, injectable bead-based scaffolds for wound healing,156 muscle,46 or neural regeneration50 should degrade possibly fast, with the degradation time of the order of weeks. In applications where implanted cells are supposed to act as a cure for prolonged periods of time, such as, e.g., in the case of insulin-producing beta cells45,51 or mesenchymal stem cells,157 the degradation time should be extended.51 This is typically achieved by the use of alginate whose mechanical and degradation properties can be additionally tuned, e.g., via adjusting the molecular weight.132

Finally, considering the degradation time of a hydrogel sample, one may expect the degradation time to actually depend on the size of the sample. In the case of the degradation due to enzymatic digestion, this time could be expected to be significantly shorter for granular hydrogels (or general microgels) as compared to the bulk nongranular samples due to the more efficient diffusion of the enzyme molecules into the hydrogel matrix in the former case, associated with the macroporosity. The data about biodegradability of microgels generated with microfluidics (>100 μm in diameter) are rather scarce, yet several reports are available in the literature.158−160 Considering the degradation of topological microgels, it is noteworthy that the compartmentalized structure can be used to degrade the different compartments selectively, a feature which could be further exploited in triggered release158 or to expedite cell aggregation within liquefied compartments.161

3.4. Most Common Hydrogels in Microtissue Engineering

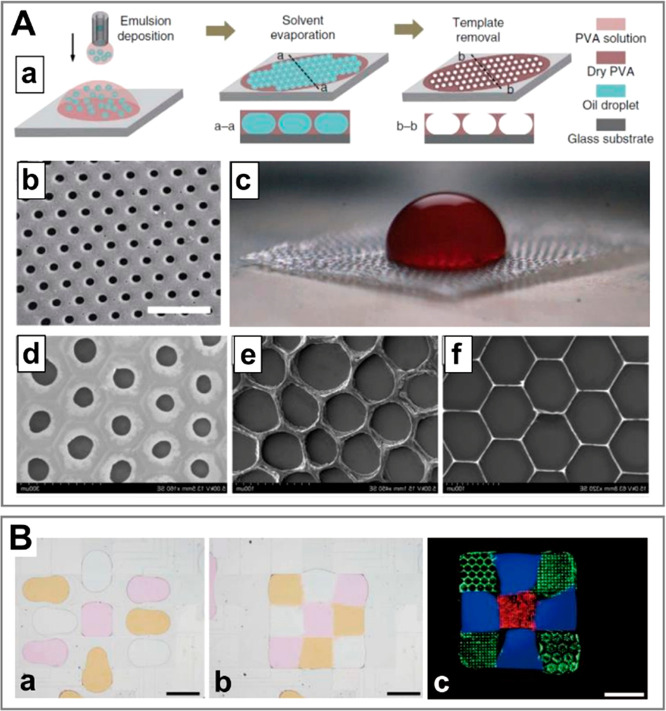

In the following, we list the most common hydrogel-forming biopolymers applied in microfluidics-assisted microgel formulations. We explain their general cross-linking mechanisms and discuss properties from the point of view of microtissue engineering. The structural formulas of the biopolymers, if available, are listed in Figure 5. We address the different biopolymers in alphabetical order.

Figure 5.

Chemical structure of biopolymers most commonly used in microtissue engineering. (A) Agarose consists of alternating d-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-α-l-galactopyranose units. Adapted with permission from ref (168). Copyright 2009 Wiley VCH. (B) Alginate consists of β-d-mannuronate (M) and α-l-guluronate (G) blocks. Adapted with permission from ref (168). Copyright 2009 Wiley VCH. (C) Chitosan consists of randomly distributed d-glucosamine and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine units. Adapted with permission from ref (168). Copyright 2009 Wiley VCH. (D) Collagen fibers self-assemble into a triple helix. Adapted with permission from ref (169). Copyright 2020 Wiley Periodicals LLC. (E) Fibrin is a protein that consists of binding sites for other proteins, enzymes, receptors, etc. Adapted with permission from ref (170). Copyright 2005 International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. (F) Structure of gelatin. Adapted with permission from ref (171). Copyright 2005 Wiley VCH. (G) Schematic representation of GelMa structure. Adapted with permission from ref (172). Copyright 2019 The Royal Society of Chemistry. (H) Hyaluronic acid consists of alternating d-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine units. Adapted with permission from ref (168). Copyright 2009 Wiley VCH. (I) Chemical structure of unmodified poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). Adapted with permission from ref (173). Copyright 2012 The Authors.

3.4.1. Agarose

Agarose is a natural biopolymer derived from algae. It is a linear polysaccharide built of two main repeating units, d-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-l-galactopyranose (Figure 5A), and has the molecular weight of almost 12 kDa. Agarose chains form helical fibers that aggregate into coiled superstructures and self-cross-link via hydrogen bonding upon cooling.162 Young’s moduli of agarose gels may vary from several kPa up to several hundred kPa.163,164 Agarose lacks any cell adhesion sites or growth factors, however, it can be easily modified to provide such functional biomolecules.165 In microfluidics, agarose-based hydrogels have been successfully used to produce cross-linkable microdroplets,72,166 including core–shell structures.167

3.4.2. Alginate

Alginate is a linear polyanionic block copolymer that is built from two main units: (1,4)-linked β-d-mannuroic (M block) and α-l-guluronic (G block) acids (Figure 5B). It can be derived from brown seaweed and is also produced by some microorganisms. The most extensively used gelation method for alginate is ionic interaction between polymer chains and divalent cations such as calcium Ca2+ or barium Ba2+. The cations form ionic bridges between polymer chains by attaching to anionic groups of alginate. It is assumed that cations preferably attach to G blocks of the alginate chains, which provide a high degree of coordination of the divalent ions.174 Alginate cross-linking has been widely exploited in microfluidics for generation of hydrogel microfibers, microbeads, as well as more complex compartmentalized microstructures.

Alginate itself does not contain RGD peptide motifs or other cell-adhesion cites so that the cells grown in pure alginate typically develop nonphysiological ball-like morphologies.89,175 The situation can be improved via using RGD-modified alginate.76 However, the relatively high rigidity of alginate suppresses cell spreading,76 which is in general disadvantageous in microtissue culture. Therefore, alginate is often mixed with other types of ECM-like hydrogels.46,176 To prevent microgel degradation, its surface can be additionally stabilized via coating with poly-l-lysine. Such modification allows long-term culture of alginate-ECM microgels.176

Considering mechanical properties, alginate is a hydrogel of intermediate stiffness, with Young’s moduli ranging from several to several hundred kPa177,178 depending on polymer concentration179 and alginate structure.177 Natively, alginates do not provide cell adhesion, but they can be modified with the adhesion motifs.180

Alginate polymers with molecular weight in the range 32–400 kDa181 find extensive applications in cell encapsulation. In particular, due to the almost immediate cross-linking of alginate upon contact with calcium ions, alginate precursors have been predominantly used as the shell phase in the core–shell capsules75,95,107,108,111,115,175,182−191 and core–shell fibers,45,46,51,67,73,106,110,189,192−197 various types of Janus and multicompartment Janus structures,67,89,198 including both capsules75,76,176,199−201 and fibers67,79,82,199,202,203 as well as all-cross-linked core–shell capsules,184,185,204 microdroplets,205 and microfibers67,69,206 with complex topology, droplet-loaded fibers,60,68,207 or helical fibers208−210 (see sections 4.4.4 and 4.5). 2D structures such as grooved microfibers,211,212 striped83 segmented213 hydrogel microsheets are also typically based on alginate (section 4.6). Finally, alginates also serve as the external cross-linkable phase in porous beads,66 porous hydrogel films,71 and porous 3D scaffolds127,214,215 (sections 4.4.3 and 4.7.4).

3.4.3. Chitosan

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide consisting of β-1,4-linked d-glucosamine and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine units (Figure 5C). It is derived from chitin, which is a natural polymer occurring in many crustacean species such as crabs and shrimp shells. Chitosan is extracted from chitin by acidic treatment followed by alkalization in order to remove proteins and some of the acetyl groups (partial deacetylation). Chitosan is normally not soluble in water, but in solutions with pH < 6.2, chitosan’s amine groups are protonated and chitosan becomes a soluble, positively charged polymer.216 It cross-links at pH above 6.2 or upon ionic interactions with negatively charged molecules.217 It is also possible to chemically cross-link chitosan, e.g., with genipin.66,218 Chitosan hydrogels have high stiffness, with Young’s modulus in the range of several up to several tens of MPa.219 They do not facilitate cell adhesion, but it is possible to provide chitosan hydrogels with, e.g., the RGD motifs.220

Due to the particularly high stiffness, chitosan has been used as a hydrogel additive or coating to improve mechanical properties of various topological microstructures such as porous materials,66,218 thin-shelled capsules,217 droplet-loaded fibers,146 or granular bioinks.221

3.4.4. Collagen

The term “collagen” generally refers to a group of proteins, which are the most abundant structural proteins in the human body synthesized mainly by fibroblasts and osteoblasts. There are 28 types of collagen, which altogether constitute a third of the total protein content in the body and are the most prevailing components of ECM of many tissues, such as skin, bone, cartilage, teeth, or tendon. Collagens are built of three polypeptide chains that form a triple helix222 (Figure 5D). Despite the diversity of the collagen family,223 about 90% of the collagen present in human body belongs to the so-called fibrillar group, the most prominent example being collagen type I,222 which, due to its abundance, is extensively used in tissue engineering. Collagens can be cross-linked via self-aggregation caused by neutralization of collagen solution with, e.g., NaOH followed by heating up to the physiological temperature (37 °C).224 It is also possible to chemically cross-link collagen with noncytotoxic cross-linking molecules, e.g., genipin.225 Collagen hydrogels can be considered as soft biomaterials, with Young’s moduli of several hundred Pa226 up to several kPa,227 unless cross-linked in nonphysiological conditions such as higher pH and/or lower temperature227 (e.g., pH = 10, T = 4 °C), in which case the compressive moduli are in the range of 10–50 kPa. Collagens natively provide sustainable cellular adhesion due to the presence of the native cell adhesion motifs.228

Collagens find extensive use in microtissue engineering. For example, collagen type I has been used in preparation of microstructures such as cell-laden microbeads,229,230 core–shell115 and Janus microspheres,176 core–shell microfibers,45 as well as in bulk hydrogel matrices as an external hydrogel phase suspending other type of microgels.231

3.4.5. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (dECM)

dECM is a biomaterial produced by elimination of cells from the native ECM. It is a mixture of various macromolecular components found in native tissues, including cell adhesion proteins and growth factors, however, the actual composition is strongly dependent on the type of tissue from which ECM was derived. The process of decellularization is also highly specific to a given type of organ232 and involves removing of potential antigens, which could lead to inflammatory or immune response.233 Preparation of dECM-based scaffolds for tissue culture usually includes self-assembly of previously prepared solution in physiological conditions (37 °C).234,235 Mechanical properties of such scaffolds depend on biochemical composition and thereby on the type of tissue from which dECM is derived, but typically the Young’s moduli of dECMs are lower than those of native tissues.236

Because dECM is produced from tissues, it provides good cellular adhesion237 and has found applications in formation of tissue-specific cell-laden microbeads for organoid/microtissue engineering including heart,238 as well as liver, lung, kidney, muscle, intestine, or stomach microtissues.239

3.4.6. Fibrin

Fibrin is a protein-based polymer that is a major component of blood clots and plays a key role in wound healing processes. Fibrin is formed by enzymatic polymerization of fibrinogen, a water-soluble glycoprotein with molecular weight of 340 kDa, built from two sets of intertwined polypeptide chains internally bridged by disulfide groups (Figure 5E). Cross-linking is mediated by thrombin,240 a serine protease present in blood. Fibrin is a biomaterial with low mechanical strength, exhibiting Young’s modulus in a range from several hundred Pa to several tens of kPa.241,242 Fibrin hydrogels natively provide cell adhesion sites.243

Fibrinogen has been extensively used as a precursor in preparation of microbeads for granular bioinks,244 as the inner phase in core–shell capsules75 and core–shell fibers45,110 or as the external matrix in 3D culture of vascular networks in the so-called angiogenic bead sprouting assays.141

3.4.7. Gelatin

Gelatin is a derivative of collagen, produced by breaking of the collagen triple helices into single-stranded chains. Chemical composition of gelatin depends on collagen it was derived from, but generally it is built from amino acid sequence in which 1 of 3 subunits is glycine (Figure 5F). One can distinguish two types of gelatin, A and B, depending on the method of synthesis. Gelatin A is obtained by acidic treatment of collagen, while gelatin B is produced by its alkaline treatment. Both types have different isoelectric points (8.0 for type A and 4.9 for type B),245 which affects the overall net charge of the polymer chains in the solution. In tissue engineering applications, the most common gelatin type is type A.65,246 It can be cross-linked using various methods, whereas the simplest one is self-aggregation upon cooling.246 However, because native gelatin liquefies in physiological conditions, various derivatives of gelatin have been proposed to overcome this problem. For example, synthesis of gelatin containing phenolic hydroxyl groups246 or thiolated gelatin247 have been reported, cross-linkable via enzymatic reactions65,246 and via Michael-type addition,247 respectively. Such hydrogels are relatively soft with the Young’s moduli ranging from several hundred Pa to several tens of kPa.248,249

In general, gelatin natively promotes cellular adhesion,250 which makes it excellent biomaterial for fabrication of porous scaffolds65,127 as well as in preparation of all-hydrogel microstructures for cell encapsulation.246

3.4.8. GelMa

GelMa is an acronym standing for gelatin methacryloyl, also called gelatin methacrylate, another derivative of gelatin. We dedicate a separate section to GelMa due to its widespread use in tissue engineering. GelMa is produced via chemical reaction between methacrylate groups of methacrylic anhydrite and the amine groups of gelatin251 (Figure 5G). It has mechanical properties resembling the ECM of soft tissues such as muscle, liver, or pancreas and can remain solid in physiological temperature (unlike native gelatin).252 Most popular method of GelMa cross-linking relies on the UV-induced photopolymerization in the presence of a photoinitiator.67,197,253 GelMa hydrogels are stiffer than unmodified gelatin, with Young’s moduli in the range from several kPa up to several hundred kPa.254 Similar to gelatin, GelMa supports cell adhesion.251

GelMa has been extensively used in preparation of microstructures, e.g., core–shell microdroplets,253 core–shell and Janus microfibers,67,197,202,255 microrods,84 as well as porous structures based on microfluidic foams256 and granular bioinks.221

3.4.9. Hyaluronic Acid (HA)

Hyaluronic acid is a linear polysaccharide that is natively present in the ECM. It takes part in many biological processes, such as wound healing, cell signaling, and proliferation. It is built from a repeating disaccharide unit (glucuronate and N-acetyl glucosamine) (Figure 5H). HA can be derived from mammalian tissues (such as rooster combs), but it can also be produced via a microbial fermentation in Escherichia coli.145 Natively, it is usually present in macromolecular form (1–10 MDa), however, for hydrogel preparation usually low molecular versions are used and are achievable via acidic or basic treatment of macromolecular HA. HA and its derivatives (such as thiolated HA247 or methacrylated HA) can be cross-linked using UV light257 or Michael-type addition.247

Hyaluronic acid and its derivatives (e.g., its methacrylated version, HAMA) have been used in production of hydrogel core–shell microstructures, hybrid hydrogel scaffolds for cell culture,247 or hollow microfibers.255

3.4.10. Matrigel

Matrigel is a trademark for a Corning company product, a complex mixture of various ECM components extracted from Englebreth–Holm–Swarm (EHS) tumors in mice. Its primary constituents are structural proteins, such as laminin, nidogen, and collagen, with total protein concentration of 8–12 mg/mL.258 Matrigel also contains heparan sulfate proteoglycans (which promote cell adhesion), growth factors like TGF-β and EGF, and small amounts of other proteins. However, exact composition of Matrigel can vary depending on the batch. After dilution of frozen Matrigel in PBS, the solution remains liquid at low temperatures and self-assembles into a hydrogel at the physiological temperature.145 Structural organization of Matrigel is caused by nidogen, which interacts with laminin and collagen as a bridging molecule.259 Even after cross-linking, Matrigel remains very soft, with Young’s modulus not exceeding 1 kPa.260

Matrigel has been used as the encapsulant in droplet-based organoid engineering,20 in particular as the material forming the core of the core–shell capsules75,120,184,190,191 or fibers,193,261 the inner coating of the core–shell microcapsules for neuron culture,108 or the core–shell fibers for blood vessel engineering,262 as well as in generation of hydrogel Janus microrods.84

3.4.11. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)

PEG is a hydrophilic synthetic polymer that is extensively used in biomedical applications. The basic PEG structure consists of (CH2–CH2–O) building blocks and has two hydroxyl end groups (Figure 5I). However, those end groups can be converted into other functional groups (i.e., methoxyl, carboxyl, amine).263 Considering spatial structure, PEG can form linear or branched polymers. Because PEG derivatives are frequently used in tissue engineering, the cross-linking mechanism depends on type of modification. However, most PEG derivatives can be cross-linked via Michael-type addition264,265 or UV light.93,266 PEGs are considered as biomaterials with intermediate mechanical strength, with Young’s modulus ranging from several kPa up to several hundred kPa.267 They do not promote cellular adhesion, but they can be easily provided with, e.g., RGD.268

PEGs have found extensive use in formulation of topological microgels, e.g., bulk macroporous hydrogels,269 jammed granular bioinks,72 porous hydrogel films,71 or core–shell structures.265

A summary of various properties of chosen hydrogels including their applications in generation of topological microtissues can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Hydrogel Properties and Their Application in Generation of Topological Microtissues (TM).

| hydrogel | gelation methods | Young’s modulus | cell–matrix interactions | biodegradability | cell types | application in TM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| agarose | temperature (cooling)72,166 | 10–800 kPa163,164 | possible after modification | possible after modification | mouse embryonic stem cells167 | microdroplets for cell coculture,72 shell in core–shell droplets270 or Janus structures166 |

| alginate | ionic95,132,271 | 5–50 kPa,177 0.2–20 kPa132,177 (microgels), 150–540 kPa178 (nonphysiological conditions) | possible after modification | possible after modification | stem cells,66,205,215,272,273 HUVECs,203,205 PC12,274 rat neural Schwann cells (RSC 96),114 rat embryonic neurons,82 osteosarcoma cells,255 cardiomyocytes,203 human liver cancer cell line (HepG2)194 | inner185 and outer phase108 in core–shell droplets, bead-loaded,198 core–shell67 and Janus199 microfibers, porous hydrogel films,71 porous scaffolds214 |

| chitosan | pH, ionic,196,275 chemical146,218 | 6–20 MPa219 | possible after modification | yes | PC1250,221 | bead-loaded fibers,221 porous foams218 |

| collagen | thermal229 | 0.1–10 kPa226,227 (physiological conditions), 10–50 kPa227 (nonphysiological conditions) | yes | yes | HUVECs,45,115,208 stem cells,95,106,110,112,231 PC12,276 preantral follicles,52,95 C2C12,195 cortical neurons45 | coculture systems,231 core–shell microspheres,230 scaffold for cell culture229 |

| decellularized ECM | thermal238,239 | depends on tissue | yes | yes | stem cells,110,192 cardiomiocytes,45 HUVECs,45,262 smooth muscle cells,262 MCF-7 cancer cells,115 cortical neurons45 | scaffold for tissue culture238,239 |

| fibrin | enzymatic144,244,275 | 0.1–30 kPa241,242 | yes | yes | cardiomiocytes,45,277 C2C12,73 HUVECs,277 fibroblasts73 | microbead generation,244 inner phase in core–shell fibers,110 hybrid hydrogels for cell culture with PEG144 |

| gelatin | thermal,246 enzymatic,246,278 Michael addition247 | 0.5–81 kPa248,249 | yes | yes | rat H9c2 myoblasts279 | core–shell structures,280 porous foam127 |

| GelMa | photoinitiated,253 thermal84 | 3–185 kPa254 | yes | yes | Schwann cells (RSC 96),221 PC12,50,221 stem cells,192,272 HUVECs,203,281 cardiac precursor cells,282 osteosarcoma cells,255 cardiomiocytes,203 fibroblasts281 | core–shell microdroplets,253 core–shell and Janus microfibers,67 microrods,84 porous foams256 |

| hyaluronic acid + derivatives | photoinitiated,283 Michael-type addition247 | 10–500 kPa257 10–25 kPa136 (microgels) | possible after modification | yes | HUVECs255 | scaffolds for cell culture,247 microfibers255 |

| matrigel | thermal20,84 | 400–480 Pa260 | yes | yes | stem cells106,108 | core–shell microstructures,108 microrods,84 microscaffold material20 |

| PEG and derivatives | photoinitiated,93,266 Michael-type addition264,265 | 5–500 kPa267 1–3 kPa131 (microgels) | possible after modification | possible after modification | stem cells,131,284 C2C12,285 HUVECs131 | beads in bulk hydrogel,269 jammed beads,72 porous hydrogel films,71 core–shell structures265 |

4. Microfluidic Strategies of Formulation of Compartmentalized Microgels

Microfluidic methods of formulation of microgel compartments can be roughly divided into those relying either on generation of hydrogel droplets or on generation of hydrogel jets, where the former serve as templates for “0D” compartments and the latter for “1D” compartments. Rapid generation of “0D” microgels typically requires the use of an external phase immiscible with the dispersed liquid-hydrogel phase, such as a hydrocarbon oil or a fluorinated oil phase, which leads to a nonvanishing interfacial tension between the aqueous and oil phases and facilitates formation of the droplets. On the other hand, transient liquid-hydrogel jets can be readily generated by also using miscible hydrogel and external phases and used to template “1D” hydrogel microfibers provided a sufficiently fast cross-linking strategy.

At this point, we make a note considering terminology. We use the term “droplet microfluidics” to refer to the systems which exploit at least two immiscible flows, while simply “microfluidics” to refer to the systems based on miscible flows (in the latter case the droplets typically do not form, only the jets). It is noteworthy that, even in the case of “droplet microfluidics”, the to-be-dispersed phase can actually also form jets (see Figure 6). We refer to such situations as the “jetting mode” of operation of a droplet–microfluidic device. In this section, we describe the conditions required for generation of droplets and jets in droplet microfluidics and provide examples of typical droplet–microfluidic junctions. The miscible flows are in general not suitable for generation of droplets but facilitate generation of jets. Jetting with miscible phases can be considered as a special case of droplet–microfluidic jetting with zero interfacial tension. Therefore, in the following, without losing generality, we consider only the case of immiscible flows.

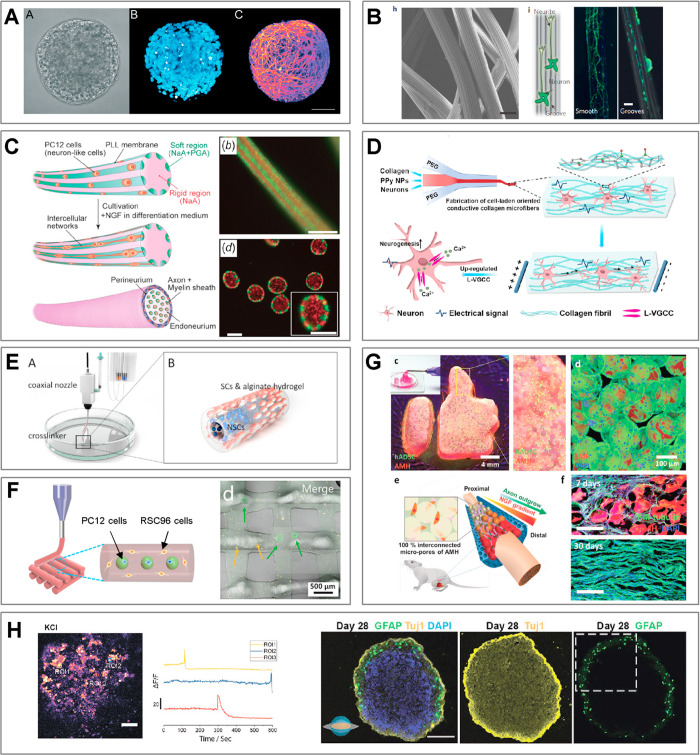

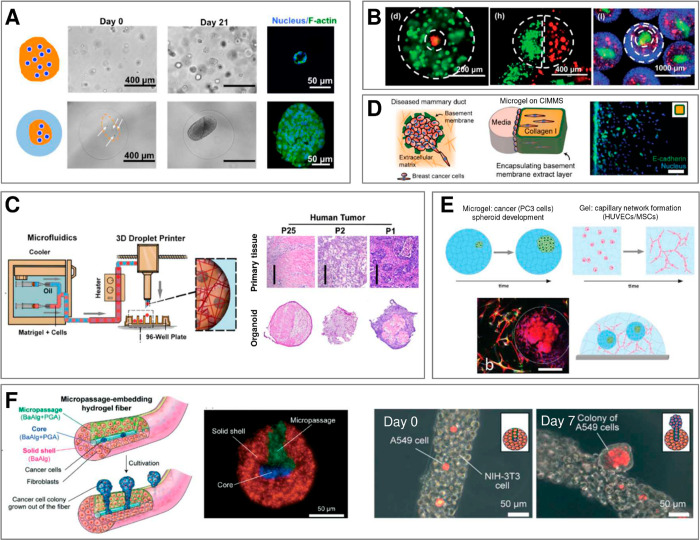

Figure 6.

Dripping-jetting transition in a microfluidic coflow junction. (a) The transition can be achieved via increase of the rate of flow of inner phase Qi or external phase Qe, resulting in either thick or thin jets. (b) Phase diagram spanned by (Qi, Qe) with indicated flow patterns observed in a coflow microfluidic device (concentric capillaries). Adapted with permission from ref (286). Copyright 2007 American Physical Society.

In general, in droplet microfluidics, the to-be-dispersed liquid, phase A, and the immiscible external liquid, phase C (we reserve the notion of phase B for the second hydrogel phase which will be introduced later), are supplied via separate microchannels which then merge at a so-called microfluidic junction. Depending on the applied rates of flow, the two phases may flow in parallel, resulting in the formation of a jet of phase A in phase C, so-called jetting mode, or such that phase A breaks into droplets carried by phase C, so-called dripping mode(286−288) (see Figure 6a). The dripping mode is typically observed at low rates of flow of the external phase and low rates of flow of the dispersed phase, whereas sufficiently high rates of flow of either the dispersed phase or the external phase lead to jetting288 (Figure 6b). Due to the small lateral dimensions of the channels, typically of the order of 100 μm, the flows are laminar, which supports reproducibility of the flow patterns. In the jetting regime, this leads to stable jets of well-defined width while in the dripping regime to highly monodisperse droplets with coefficient of variation (CV) of droplet diameter, typically in the range 1–3%.289 The frequencies of droplet generation actually depend on the size of the generated droplets and range from the order 101–102 Hz for droplets of diameter roughly in the range 100–300 μm to 103–104 Hz for droplets of diameter in the range 10–50 μm.290−292 In applications involving encapsulation of cells for the purpose of formulation of microtissues, the number of encapsulated cells should be at least ∼102 in order to allow rapid formation of microtissues via cell aggregation.230 Because typical cell concentrations in the hydrogel precursor are of the order of 107 cells/mL, the droplet volume should be at least 10 nL, which then corresponds to typical droplet diameter of around 270 μm.

4.1. Generation of Droplet or Jets

In general, one can distinguish several different geometries of the microfluidic junctions which lead to different mechanisms of droplet breakup and determine the dripping/jetting regimes. The most common geometries, together with their advantages and disadvantages, are shortly listed below. The list includes droplet generators based on channels microfabricated in transparent chips, that is, plastic plates such as polycarbonate, poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), or Teflon plates, as well as in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). In all those cases the channels have typically rectangular or square cross-sections. In contrast, in the devices based on capillaries or needles, the channels naturally have a circular cross-section.

Cross-flowjunction. One of the simplest junctions consisting of two crossed channels,287,288 with the continuous phase supplied symmetrically from both sides of the dispersed phase (Figure 7a). The dispersed phase is periodically squeezed and pinched off by the continuous phase, resulting in formation of droplets.

Co-flow junction. The geometry consists of two concentric tubes, needles (Figure 7b), or capillaries of circular cross-section, where the dispersed phase is delivered to the inner capillary (Figure 7c). This type of junction is easy to fabricate, as it does not require micromachining but only aligning of the capillaries. The droplets, generated by the Rayleigh–Plateau instability, are not squeezed by the walls in any direction, which eliminates the problem of wetting of the walls by the dispersed phase and facilitates droplet or jet cross-linking on-chip. The capillaries (or needles) can be nested one inside the other or assembled tip-to-tip, i.e., facing each other. In the latter case, the size of the droplets is set by the dimeter of the tip of the outlet capillary, which allows generation of very small droplets of diameters routinely below 100 μm.

T-junction: In a T-junction, the channels meet at an angle 90° (Figure 7d). The main advantage of this type of junction is the simplicity of design and small footprint. The droplets are generated via shear-induced pinch-off.291

Flow-focusing junction. The flow-focusing geometry is a modification of the cross-flow geometry (Figure 7e). The dispersed phase is focused into a narrowing by the continuous phase before breaking into droplets.293 The main advantages of the geometry are high achievable frequencies of droplet generation and small droplet sizes.292

Step junction. The geometry consists of a shallow supply channel and a deep outlet channel separated by a step (Figure 7f). The droplets are generated via the imbalance of the LaPlace pressure upstream and downstream the step,294 and the droplet size is set predominantly by the depth of the supply channel. In particular, the droplet size is nearly independent of the applied rates of flow.295 Step junctions can be easily parallelized: devices with over 500,296 1000,297 or even 10000298 parallel nozzles have been demonstrated. However, this type of junction is typically not suitable to formation of jets.

Pulse-based droplet generator: In this type of droplet generator, the droplets are generated via periodic mechanical pulses exerted, e.g., via piezo-transducers299 or pressurized microchannels197 positioned next to the supply channel (g); geometry has little impact on droplet formation in this case, whereas the role of the external phase is just to carry away the generated droplets. Pulse-based generators have been applied in systems with extremely low interfacial tensions such as aqueous two-phase systems (e.g., consisting of PEG-rich and dextran-rich phases).

Body-force-base generators. The geometry of droplet generators based on body forces, such as gravity, buoyancy, or centrifugal forces, consists of an outlet (a tip of a needle or capillary) of the dispersed phase coaligned with the direction the external body force (Figure 7h). The droplets are generated either in the jetting regime in which the ejected fluid breaks into droplets via Rayleigh–Plateau instability300 or in the dripping regime in which the fluid forms a growing droplet at the outlet which subsequently pinches off under the body force.62,66 The method is relatively simple as it does requires neither microfabrication nor aligning of capillaries, and as such it has been widely applied in the formulation of hydrogel microcapsules and microfibers.62,66,300

Electric-field assisted generator. This type of generator resembles the above-mentioned body-force generators in that it involves an external field, in this case the electric field66,75,301 (Figure 7i). The droplets are pulled off an electrified needle and their sizes can be adjusted via tuning the applied voltage. The dynamic range of droplet sizes is significantly larger than in the case of a simple gravity-based generator.66,301 In particular, smaller droplets of sizes close to the needle-tip diameter can be readily generated, whereas gravity-based generators lead to droplets of diameter close to the capillary length, i.e., typically around 1 mm, only weakly depending on the diameter of the needle.58

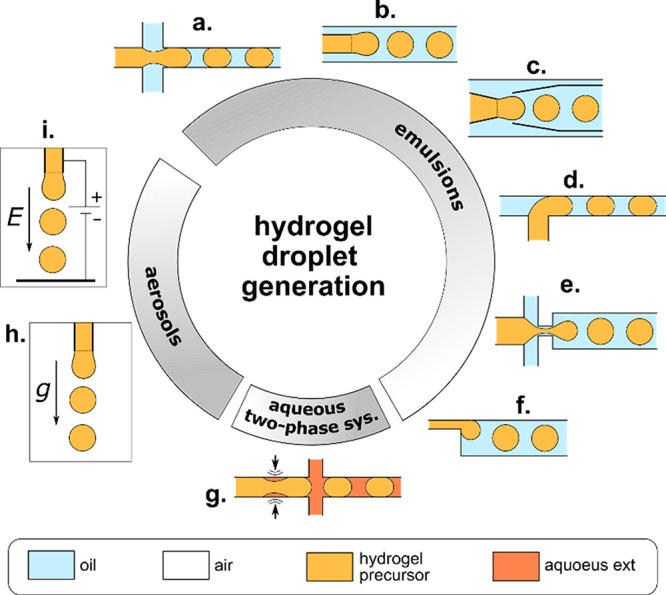

Figure 7.

Microfluidic junctions used for generation of hydrogel droplets. We classify the geometries according to the type of generated dispersions: emulsions, aqueous two-phase systems, or aerosols. The list includes (a) cross-flow junction, (b) coflow junction, (c) concentric capillaries, (d) T-junction, (e) flow-focusing junction, (f) step junction, (g) pulse-based droplet generator, (h) gravity (or centrifugal) generator, (i) electric-field assisted generator.

Finally, one can also distinguish reconfigurable junctions whose geometry, e.g., the size of the orifice in a flow-focusing geometry, can be altered on-demand. For example, in a PDMS flow-focusing junction, the orifice can be squeezed by the pressurized air pockets placed on both sides of the narrowing and used to control the droplet/bubble size on-demand without changing the rates of flow;289 this type of junction has been recently employed, e.g., in 3D printing of functionally graded porous materials.54

In the following, we review the microfluidic strategies of formulation of microgels, which in general must take into account the type of applied hydrogel and its cross-linking mechanism. In many cases, the physicochemical factors involved in the cross-linking process are the ones that determine the layout and/or dimensions of microchannels and microfluidic junctions.

4.2. Physical Cross-Linking of Hydrogel Droplets and Jets

Considering general cross-linking mechanisms applied in microfluidics-assisted generation of microgels, one can distinguish chemical and physical cross-linking. Physical cross-linking relies on self-assembly of hydrogel molecules into a network induced by a change in solution temperature or mediated by physical (noncovalent) interactions between polymer chains and a cross-linker, such as ionic interaction, hydrogen bonding, or host–guest complexation.302 Physically, cross-linked hydrogels, due to the relatively weak nature of the molecular “physical” interactions, i.e., as compared to the covalent bonds in chemically cross-linked hydrogels (see section 4.3), are usually soft and easily degradable. The advantage of the physical cross-linking process are mild conditions which allow the embedded cells to retain high levels of viability.

4.2.1. Ionic Cross-Linking

One of the cross-linking methods particularly widespread in microfluidics is the so-called ionic cross-linking. Typically, the method involves the use of sodium alginate which cross-links in the presence of calcium cations Ca2+ into gelous calcium alginate. Upon coalescence of an alginate droplet with an external calcium bath, the cross-linking proceeds via rapid quench of the droplet interface, which takes of the order of milliseconds or shorter as can be judged from the fastest available microgel formulation frequencies (∼105 Hz62,199,303). The cross-linking time scale is accordingly typically much shorter than the time scale associated with mixing of the nanoliter liquid compartments and allows generation of the compartmentalized architectures. One can distinguish two methods of alginate cross-linking applicable to droplets and jets: (i) off-chip cross-linking (Figure 8a) achievable via coalescence with an external aqueous bath containing calcium ions and (ii) on-chip cross-linking (Figure 8b). In the latter case, calcium ions can be contained in the external oil phase (“Ca2+” method) or released from the droplet phase upon reaction with an organic acid dissolved in the external phase (‘H+’ method).

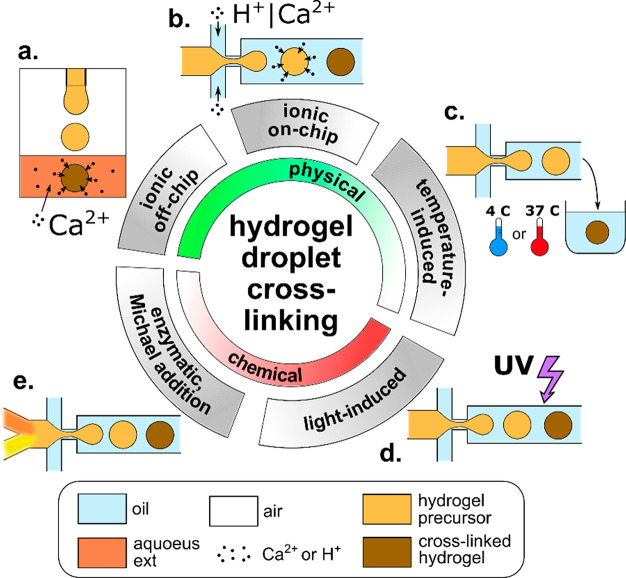

Figure 8.

Microfluidic strategies of cross-linking of hydrogel droplets. (a) Ionic off-chip cross-linking, (b) ionic on-chip cross-linking, (c) temperature-induced, (d) light-induced, (e) chemical reaction-based (such as Michael addition or enzymatic cross-linking). In ionic on-chip cross-linking (b), the calcium ions are either delivered directly in the external phase (“Ca2+”) or trigger-released from the hydrogel precursor upon contact with the acidic external phase (“H+”).

In the “Ca2+” method, the calcium ions can be dispersed in oil in the form of nanoemulsion95,107,304 or directly dissociated. In the latter case, an oil-soluble calcium source must be used, such as calcium acetate.305 Otherwise, dissolution of calcium chloride in oil can be mediated with the use of an alcohol such as 2-methyl-1-propanol.306 To provide complete gelation without channel clogging, the total time required for reaction must be shorter than the time within which droplets are present on the chip but longer than the droplet formation time, which in general puts a constraint on the available rates of flow. An alternative clogging-free modification of the approach is the formulation of a W/O/W emulsion containing alginate as the inner aqueous phase, calcium nanoemulsion as the middle oil phase, and water as the outer phase.307

In the “H+” method, calcium ions are released from a calcium compound such as Ca-EDTA or CaCO3 pre-encapsulated in the droplet phase, e.g., upon a pH change at contact with the external oil phase containing dissolved organic acid, e.g., acetic acid.184,271,308−310 The acid dissociates at the droplet surface releasing H+ cations which react with the calcium compound, triggering the release of Ca2+, which in turn gradually cross-links alginate. This relatively slow gelation method requires incubation of droplets to complete the cross-linking reaction. The method is easy to perform and results in a homogeneous gelation in the whole droplet volume, but pH drop caused by H+ release may have a negative effect on cell viability.311

It is noteworthy that sodium alginate is not the only prepolymer that can be cross-linked with ionic interactions. Chitosan, which contains amine groups, becomes positively charged in solutions with pH < 7. Therefore, it can be cross-linked using multianionic cross-linkers, such as P3O105–.312 Another approach, involving the use of chitosan and aimed specifically at generation of core–shell structures, has been recently proposed by the Qin group.217,275,313 The method relies on the use of a two-phase aqueous system with alginate-rich droplet phase and chitosan-rich external phase, in which alginate–chitosan complexation results in formation of capsules217,275 or fibers304 with ultrathin shells.

Lastly, we note that microfluidic cross-linking of alginate microfibers has been also demonstrated using barium cations Ba2+.74,206

4.2.2. Temperature-Triggered Cross-Linking

Temperature-triggered cross-linking is often used due to the ease of application and a variety of hydrogels that cross-link upon cooling or heating. One can distinguish hydrogels with an upper critical solution temperature, Tcrit,up, which cross-links below Tcrit,up and those with a lower critical solution temperature, Tcrit,low, which cross-links above Tcrit,low. In the hydrogels commonly applied in tissue engineering, the cross-linking relies either on the formation of hydrogen bonds between polymer chains upon cooling, typically down to 4 °C, such as in the case of gelatin,246 GelMa,84 or agarose72,166 or on interactions between proteins, such as, e.g., in collagen,229 Matrigel,20,84 or decellularized ECM,238,239 achievable via elevation of temperature up to physiological 37 °C. Temperature-triggered gelation in most cases happens off-chip (Figure 8c), but it can also be obtained on-chip by cooling the whole microsystem with hydrogel microdroplets inside.314 Cross-linking of the core phase in the core–shell structures can be conveniently achieved via change in temperature following, e.g., ionic shell cross-linking.20,229,246 Also, ionically cross-linked Janus microgels consisting of a mixture of alginate and collagen (or Matrigel) have been additionally temperature-cross-linked, which allowed subsequent alginate dissolution for generation of soft Janus capsules.84,176

4.2.3. Host–Guest Interactions

Another method of physical microgel cross-linking involves host–guest interactions widely investigated in the field of supramolecular chemistry in recent years. Host–guest interactions rely on recognition of molecular motifs and formation of noncovalent bonds. As such, and because of their dynamic nature, host–guest interactions resemble the molecular interactions in biological systems, including those responsible for cross-linking of biopolymers. In synthetic hydrogels, cyclic compounds such as cyclodextrins can be used as “hosts” in formulation of cross-links by providing reversible bonds with various “guest” units.315 Such strategy offers a great potential in biomaterial design, and recent works indicate also a possibility of its adaptation in microfluidic formulation, e.g., of core–shell capsules.316,317 However, to date, there are no available reports of the application of such structures in encapsulation of mammalian cells.

In summary, various physical cross-linking methods can be used to formulate microgels. In particular, ionic cross-linking proves advantageous in processes requiring rapid quenching of miscible hydrogel compartments, such as in solidification of the shell-forming phase in the precursor core–shell structures. On the other hand, mild conditions involved in the temperature-triggered cross-linking or host–guest interactions are advantageous in terms of cell viability and often yield hydrogels better mimicking the actual ECM. Noteworthy, various cross-linking approaches can also be combined.108

4.3. Chemical Cross-Linking of Hydrogel Droplets and Jets

Chemical cross-linking is mediated by chemical reactions in which a polymer chain forms a covalent bond with a cross-linker molecule. Examples include light-induced cross-linking, enzymatic cross-linking, and Michael-type addition. Because residual cross-linking molecules such as free radicals can interact with the biological content of the sample (proteins, cells),302 the choice of the cross-linker is crucial for biocompatibility of the hydrogel. Despite potential cytotoxicity, chemically cross-linked hydrogels typically develop better mechanical properties (e.g., higher Young’s and storage moduli) and lower degradation rates as compared to physically cross-linked ones.

4.3.1. Light-Induced Cross-Linking

In light-induced cross-linking, a polymer solution is mixed with a photoinitiator and exposed either to UV or visible light, which leads to homogeneous breakage of bonds in the photoinitiator molecules, resulting in the release of free radicals. As free radicals are very reactive, they form bonds between the polymer chains, which in turn lead to fast hydrogel cross-linking. Short gelation time provides high control over the cross-linking process; in particular, it can be used to “quench” (Figure 8d) nonspherical droplet shapes318 or prevent mixing of different hydrogel compartments. It allows continuous cross-linking of droplets on-the-fly either in the outlet tubing282,319 or on-chip.93,266,320 The droplets may also be cross-linked after their collection in an external chamber, however, in such a case their shape may be affected by contact with other droplets.321 In some cases, on- and off-chip cross-linking may be combined. This strategy has been used, e.g., in order to anneal the prepolymerized droplets into a porous hydrogel scaffold322 (see also section 4.7.1). The most common UV-cross-linkable hydrogel used in generation of cell-laden microgels is gelatin methacryloyl (GelMa), which well mimics the extracellular matrix.253 The time scale of cross-linking of GelMa depends on light intensity and the concentration of the photoinitiator in the hydrogel precursor and can reach down to several seconds at high applied UV intensities.253 Such a time scale is typically short enough to allow on-chip cross-linking of droplets, which is advantageous in terms of microgel uniformity and reproducibility. It has been applied mostly to generate simple microbeads and bead-based porous scaffolds,160 as well as core–shell capsules with GelMa shell.253 In general, however, in one-step fabrication of complex microgel architectures, the time scale of UV-induced cross-linking, as compared to, e.g., ionic cross-linking, may be considered a limiting factor.

Besides GelMa, also other hydrogels such as hyaluronic acid derivatives,72,247,323 PEG-fibrinogen,46 PEG derivatives,93,266 or gelatin-PEG derivatives324 have been applied in UV-mediated cell encapsulation. Topological core–shell or Janus microstructures with single or multiple solid or liquid cores have been demonstrated using poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA),325,326 ETPTA89 or polyacrylamides.63,90,327 However, the utility of acrylates and acrylamides in cell encapsulation and culture can be questioned. In particular, non-fully cross-linked acrylamides as well as certain acrylic resins such as ETPTA are known to be cytotoxic.

4.3.2. Enzymatic and Michael Addition-Based Cross-Linking

Some hydrogels can be cross-linked enzymatically or via Michael type addition reactions. In such cases, the reactions are initiated after mixing of the biopolymer with an enzyme or cross-linker, respectively. Enzymatic cross-linking is in general favorable for cells because cross-linkers are typically not cytotoxic. Examples include cross-linking of gelatin with microbial transglutaminase,278 phenol-modified gelatin with horseradish peroxidase,246 and hydrogen peroxide328 or fibrin with thrombin.244 Typically, separate streams containing the polymer and the cross-linker (or enzyme) molecules merge on-chip prior to droplet generation, followed by intradroplet mixing (Figure 8e) and gradual gelation on-chip or off-chip. The process of cross-linking typically takes from several minutes to hours, depending on the applied reactant concentrations. In topological microstructures enzymatically cross-linkable hydrogels such as fibrin are typically used as “dopants”, e.g., to provide ECM-like microenvironment, whereas mechanical stability is provided by another hydrogel such as alginate.75,110