Abstract

Objective

The β-carotene oxygenase 1 (BCO1) is the enzyme responsible for the cleavage of β-carotene to retinal, the first intermediate in vitamin A formation. Preclinical studies suggest that BCO1 expression is required for dietary β-carotene to affect lipid metabolism. The goal of this study was to generate a gene therapy strategy that over-expresses BCO1 in the adipose tissue and utilizes the β-carotene stored in adipocytes to produce vitamin A and reduce obesity.

Methods

We generated a novel adipose-tissue-specific, adeno-associated vector to over-express BCO1 (AT-AAV-BCO1) in murine adipocytes. We tested this vector using a unique model to achieve β-carotene accumulation in the adipose tissue, in which Bco1−/− mice were fed β-carotene. An AT-AAV over-expressing green fluorescent protein was utilized as control. We evaluated the adequate delivery route and optimized cellular and organ specificity, dosage, and exposure of our vectors. We also employed morphometric analyses to evaluate the effect of BCO1 expression in adiposity, as well as HPLC and mass spectrometry to quantify β-carotene and retinoids in tissues, including retinoic acid.

Results

AT-AAV-BCO1 infusions in the adipose tissue of the mice resulted in the production of retinoic acid, a vitamin A metabolite with strong effects on gene regulation. AT-AAV-BCO1 treatment also reduced adipose tissue size and adipocyte area by 35% and 30%, respectively. These effects were sex-specific, highlighting the complexity of vitamin A metabolism in mammals.

Conclusions

The over-expression of BCO1 through delivery of an AT-AAV-BCO1 leads to the conversion of β-carotene to vitamin A in adipocytes, which subsequently results in reduction of adiposity. These studies highlight for the first time the potential of adipose tissue β-carotene as a target for BCO1 over-expression in the reduction of obesity.

Keywords: Retinoic acid receptors, Retinol, Fat, Adipogenesis

Highlights

-

•

β-carotene oxygenase 1 (BCO1) cleaves β-carotene to form vitamin A.

-

•

We generated an adipose tissue vector to study the effect of BCO1 over-expression in the adipocyte.

-

•

Female mice over-expressing BCO1 in the adipocyte generated retinoic acid, and as a result, the adipose tissue size was reduced.

1. Introduction

Adipose tissue accounts for the largest fat storage in the body [1]. Human adipose tissue is characterized by its yellow coloration, caused by dietary carotenoids. Among the different carotenoids present in adipocytes, β, β′-carotene (β-carotene) is widely considered the most relevant to human health because of its pro-vitamin A activity and abundance in our diet [2,3]. β-Carotene is converted to vitamin A by the action of the enzyme β-carotene oxygenase 1 (BCO1), an enzyme expressed in all mammals [4]. The enzymatic activity of BCO1 varies between species, contributing to the interspecies differences in carotenoid accumulation in tissues between organisms [2,5]. For example, wild-type mice do not store significant amounts of carotenoids in tissues, which makes it difficult to study the accumulation of dietary compounds in an experimental model using such mice [2].

BCO1 is the rate-limiting enzyme in the formation of vitamin A in mammals, and it is particularly important for those who rely entirely on a vegetarian diet, since plants do not store vitamin A [4]. BCO1 cleaves β-carotene to form two retinal molecules, which can be either reduced to retinol or oxidized to retinoic acid. Retinol is typically esterified to retinyl esters in tissues, to mitigate vitamin A deficiency [6]. Retinoic acid is the transcriptionally active form of vitamin A that binds and trans-activates the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs), promoting lipid oxidation in various cell types, including adipocytes [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]].

Clinical and preclinical studies suggest that β-carotene intake reduces obesity and ameliorates the plasma lipid profile. Our part research shows that BCO1 activity mediates these positive effects on lipid metabolism. In 2011, we reported that dietary supplementation with β-carotene in wild-type mice reduces adipocyte and adipose tissue size [13]. These effects were associated with increased Cyp26a1, a surrogate marker of retinoic acid levels, and a downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparg) signaling, a master regulator of lipogenesis [14,15]. Bco1−/− mice fed β-carotene accumulated over 10-fold greater β-carotene levels than wild-type mice but failed to show differences in adiposity compared to littermates fed a diet without β-carotene [13].

We recently found that increased BCO1 activity is associated with reducing plasma cholesterol in young individuals, suggesting that the conversion of retinoids could reduce cardiovascular disease [16]. In a separate study, we observed that a diet supplemented with β-carotene delayed atherosclerosis development in low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)–deficient mice. However, β-carotene supplementation to Bco1−/−Ldlr−/− mice altered neither cholesterol nor atherosclerosis, confirming the key role of BCO1 in regulating lipid metabolism in mammals.17

This study aimed to examine whether β-carotene accumulated in the adipose tissue of mammals could serve as a vitamin A precursor. By over-expressing BCO1 in the adipose tissue of Bco1−/− mice fed β-carotene, we show that BCO1 over-expression in the adipocyte mediates the conversion of β-carotene to retinoids, including retinoic acid. Our results reveal for the first time that the tissue-specific conversion of β-carotene to vitamin A is possible, opening new avenues to treat obesity and other metabolic diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal husbandry and diets

The University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign Animal Care Committee approved animal procedures and experiments. For all studies, we utilized congenic male and female Bco1−/− mice that were cross-bred with C57/BL6 wild-type mice for 11 generations [18]. Mice were maintained at 24 °C in a 12:12 h light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water. Dams and pups were fed a non-purified breeder diet containing 15 international units (IU) of vitamin A/g until the pups reached three weeks of age (Teklad Global 18% protein diet; Envigo, Indianapolis, IN). Mice were weaned onto a breeder diet for another week before switching to an experimental diet for the dietary interventions. These interventions were carried out using purified, pelletized diets containing either 50 mg β-carotene/kg diet or 4 IU retinyl acetate/g. The exact composition of the diets can be found in Supplementary Table 1. For all diets, β-carotene was incorporated using a water-soluble formulation of beadlets (DMS Ltd., Sisseln, Switzerland) and prepared by Research Diets (New Brunswick, NJ) by cold extrusion to protect the β-carotene from heat and light. Diets supplemented with retinyl acetate contained placebo beadlets (without β-carotene) [17]. Food intake and body weights were monitored once a week.

On the day of the sacrifice, we injected the mice with an intraperitoneal dose of anesthesia (80 mg ketamine and 8 mg of xylazine/kg of body weight). Blood was drawn directly from the heart using EDTA-coated syringes and kept on ice. Mice were then perfused with saline solution (0.9% NaCl in water) for approximately 2 min. After perfusion, the inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT), gonadal WAT (gWAT), liver, and other organs were harvested and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen to store at −80 °C. A portion of the iWAT at the lymph node level was stored in a 10% formalin solution for histological analyses, as previously described [13].

2.2. Adipose tissue-specific adeno-associated viral (AT-AAVs) constructs and injections

All AT-AAVs were synthesized by the University of Pennsylvania Vector Core facility (UPenn Vector Core). AT-AAV constructs were produced and developed by combining the AAV8-ADIPO-miR-122(8×) construct backbone developed by Dr. Muredach P. Reilly's group [19]. A cDNA construct encoding murine BCO1 (GENEWIZ, Azenta Life Sciences, NJ) was cloned into the AT-AAV empty backbone to generate AT-AAV-BCO1. AT-AAV containing the cDNA encoding the enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP), named AT-AAV-GFP, was used as a control in all the experiments.

2.3. Isolation of adipocytes and stromal vascular fractions

Fresh iWAT was digested with collagenase D (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). After filtration and washing steps, the mature adipocytes and stromal vascular fraction were obtained following the protocol described above [20]. Fractions were immediately lysed in Trizol LS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for mRNA isolation and gene expression analyses (see above).

2.4. Adipose tissue transplants

To prevent allograft rejection, all donor and recipient mice were sex-matched siblings. At four weeks of age, we put Bco1−/− donor mice on a standard diet containing 4 IU of retinyl acetate, while Bco1−/− recipient mice were fed a diet supplemented with 50 mg/kg of β-carotene (Supplementary Table 1). Six weeks later, we injected adipose tissue donor mice with 1 × 10 [11] G.C./mouse of either AT-AAV-GFP or AT-AAV-BCO1 subcutaneously in the iWAT. Four weeks after injections, donor mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and iWAT was dissected and placed in cold, sterile phosphate saline buffer (PBS). Approximately 100 mg were cut into two pieces and transplanted subcutaneously onto the back of each recipient mouse, following established protocols [21]. After the surgeries, Bco1−/− recipient mice continued on the same diet for six more weeks before tissue harvesting.

2.5. Analysis of non-polar retinoids and carotenoids

Non-polar compounds were extracted from 50 mg of the liver, adipose tissue, or 70–100 μL of plasma under dim yellow safety light. Before extracting retinoids and carotenoids from the adipose tissue, samples were saponified to obtain the sum of non-polar retinoids (retinyl esters + free retinol), as described previously [13].

Carotenoids and retinoids were extracted in a methanol, acetone, and hexane mixture. The organic phase was removed, and the extraction was repeated with hexane alone. The collected organic phases were pooled and dried in a SpeedVac (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The residue was dissolved in 200 μL of HPLC solvent (hexanes/ethyl acetate, 80:20, v/v). HPLC was performed with a normal phase Zobax Sil (5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm) column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Isocratic chromatographic separation was achieved with 20% ethyl acetate/hexane at a 1.4 ml/min flow rate. The HPLC was scaled with the β-carotene, retinol, and retinyl ester standards (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for molar quantification, as we did in early studies [22,23].

2.6. Retinoic acid quantification

Retinoic acid was extracted following a two-step liquid–liquid extraction under yellow UV-blocking lights. We homogenized 50–100 mg of iWAT tissue was homogenized in 2 ml of saline, after which two 1 ml technical replicates were extracted. The first step of the extraction was effected by adding 3 ml 0.025 M KOH in ethanol, vortexing to mix well, followed by the addition of 10 ml hexane and vortexing to mix well, and centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 1 min to facilitate phase separation. The organic phase containing retinol and retinyl esters was transferred to a new tube and put on ice. To the remaining aqueous phase, 200 μL of 4 M HCl was added, followed by vortex to mix well and a subsequent addition of 10 ml of hexane, followed by vortexing to mix well and centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 1 min to facilitate phase separation. The upper organic layer was transferred to a new tube that contained retinoic acid and more polar retinoids. These organic layers were evaporated under nitrogen with gentle heating at 30 °C in a water bath until dry. The retinoic acid-containing residue was resuspended in 60 μL acetonitrile and placed in deactivated glass low-volume inserts for LC-MS/MS vials. Liquid chromatography-multistage-tandem mass spectrometry has performed with a Shimadzu Prominence UFCL XR liquid chromatography system (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD) coupled to an AB Sciex 6500 QTRAP hybrid triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA) using atmospheric pressure chemical ionization operated in positive ion mode as described in our past research [24]. The retinoic acid content in each sample was normalized to the tissue weight.

2.7. Western blot analyses

Samples were homogenized in a RIPA-lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 140 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate), in the presence of protease inhibitors (SigmaFast, Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 1 mM PMSF. Protein quantification was performed using the bicinchoninic acid assay, following the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Between 80 and 100 μg of total protein homogenate were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in fat-free milk powder (5%, w/v) and dissolved in Tris-buffered saline (15 mM NaCl and mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5) containing 0.01% Tween 20 (TBS-T). After washing, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the appropriate antibody. For GFP detection, a goat anti-GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) was used at a 1:1000 dilution; for BCO1 detection, a rabbit anti-mouse BCO1 [25] was used at 1:500 dilution; for PPARγ detection, a mouse monoclonal anti-PPARγ (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was used at 1:1000 dilution. Anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) was used at a 1:1000 dilution as a loading control. Infrared fluorescent-labeled (Li-Cor Bioscience, Lincoln, NE) or HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were prepared in TBS-T with 5% fat-free milk powder and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoblots incubated with HRP-conjugated antibodies were developed with the ECL system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and scanned. Protein band quantification was performed using Quantity One (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

2.8. mRNA isolation and RT-PCR analyses

Total mRNA isolation was carried out with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentration and purity were measured with a Nano-drop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The Applied BioSystems retro-transcription kit was used to generate cDNA. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of tissues were performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) or TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The following primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) were used: actin beta (Actb; 5′-ACGGGCATTGTGATGGACTC-3′ and 5′-GTGGTGGTGAAGCTGTAGCC-3′), cytochrome P450 12a1, (Cyp26a1; 5′-CGTCAATGGGAAGAGAGAAGA-3′ and 5′-ACAAGC AGCGAAAGAAGGTG-3′), glyceraldehyde-3-phospate dehydrogenase (Gapdh; 5′-TTGGCATTGTGGAAGGGCTCAT-3′ and 5′- GATGACCTTGCCCACAGCCTT -3′), leptin (Lep; 5′-ATGCATTGGGAACCCTGTGCGG-3′ and 5′- TGAGGTCCAGCTGCCACAGCATG-3′), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, (Pparg; 5′-AGGGCGATCTTGACAGGAAA-3′ and 5′- CGAAACTGGCACCCTTGAAA-3′), retinoic acid receptor beta, (Rarb; 5′-GACAGGAACAAGAAAAAGAAGG-3′ and 5′-GGCAGAGTG AGGGAAAGGT-3′), protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type c, (Ptprc; 5′-GTTTTCGCTACATGACTGCACA-3′ and 5′- AGGTTGTCCAACTGACATCTTTC-3′), dehydrogenase/reductase 9, (Dhrs9; 5′- CAGTGGGTGAAGAGCCATGT -3′ and 5′- CAGTCAGTGGGAGCCAACA-3′), aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member a1, (Aldh1a1; 5′-GGCCTTCACTGGATCAACAC-3′ and 5′- CGACACAACATTGGCCTTGA-3′), Aldh1a3; 5′-CAGCGCATGATCAACGAGAA-3′ and 5′-CCTGGGTCT GACGAGTCTTT-3′). We used probes for Gfp (#557631, Biosearch, Petaluma, CA); Bco1, Mm01251350_m1; Bco2 Mm Mm00460051_m1 and Aldh1a2, Mm00501306_m1 (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA).

Gene expression analyses were performed with the StepOnePlusTM Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA) and the cycle threshold (Ct) calculation method using β-actin or GAPDH as housekeeping genes.

2.9. Adipose tissue histology

Lymph nodes from iWAT lobules were fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) overnight at 4 °C. They were then dehydrated, cleared, and paraffin-embedded. Five μm-thick sections at the same level were obtained and stained with modified Harris hematoxylin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and eosin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for morphometric analysis performed by digitally acquiring adipocytes surrounding the inguinal lymph node (ZEISS Axioscope 40 microscope).

To obtain immunofluorescent stainings, we rehydrated tissue sections before blocking them with 5% bovine serum albumin. Slides were stained with rabbit anti-mouse GFP primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) followed by an Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Sections were incubated with DAPI and mounted with Permount medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Images were acquired using Zeiss LSM 700 Confocal.

2.10. Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Results were analyzed using a two-tailed student's t-test, one-way or two-way ANOVA, and repeated measures ANOVA. Tukey's multiple comparison tests using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) followed. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Delivery route and cell specificity of AT-AAV construct

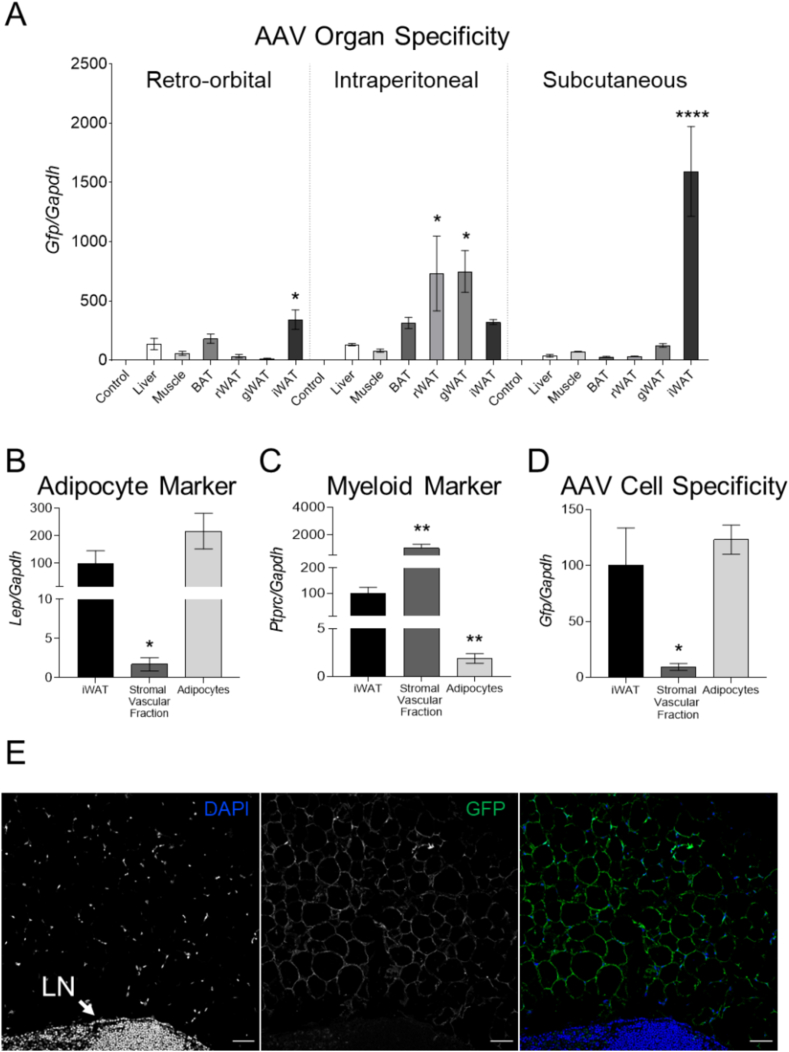

In 2014, Dr. Reilly's group developed an AT-AAV encoding GFP (AT-AAV-GFP) to target the adipose tissue for gene therapy applications [19]. Using this construct, we first compared the organ specificity of this vector by administering 1 × 10 [11] genomic copies (GC) by retro-orbital, intraperitoneal, and subcutaneous injections directly on the iWAT of wild-type mice. Mice injected with PBS were utilized as controls. Ten weeks later, we examined Gfp levels by using RT-PCR. Expression data showed that direct subcutaneous injection to the iWAT achieved the greatest Gfp mRNA expression in this organ, in that it was 4-fold greater than in the iWAT of mice injected retro-orbitally or intraperitoneally. The subcutaneous injection directly in the iWAT also limited Gfp expression to this tissue (Figure 1A), prompting us to utilize this delivery route for the remaining studies.

Figure 1.

The AT-AAV targets mature adipocytes. (A) Wild-type mice were injected using retro-orbital, intraperitoneal, or subcutaneous route at the level of iWAT with 1 × 10 [11] GC/mouse with AT-AAV encoding GFP. Ten weeks later, we harvested tissues to compare Gfp expression by RT-PCR. Liver samples isolated from mice injected with PBS were used as a reference (control). (B–D) Wild-type mice injected subcutaneously in the iWAT with AT-AAV-GFP were harvested after 10 weeks. Samples were digested to separate the stromal vascular fraction from mature adipocytes (Adipocytes). Expression levels of Lep, Ptprc, and Gfp were measured by RT-PCR. Gapdh was used as housekeeping control. (E) Immunostaining of adipose tissue sections highlight the presence of GFP in adipocytes, but not immune cells present in the lymph node (LN). Size bar 50 μm. Values are represented as means ± SEMs. Statistical differences were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.001 referred to either (A) control, or (B–D) iWAT.

We next examined the cellular specificity of the AT-AAV-GFP vector. Ten weeks after the injections, we digested the iWAT with collagenase to separate mature adipocytes from the stromal vascular fraction. The purity of these fractions was estimated by measuring the mRNA expression of Lep and Ptprc, which correspond to adipocyte and leucocyte markers, respectively (Figure 1B, C). Gfp mRNA levels were nearly absent in stromal vascular cells, indicating that the AT-AAV construct targets mature adipocytes (Figure 1D). These results were confirmed by immunostaining of adipose tissue sections. GFP was present in most adipocytes, but it was absent in neighboring immune cells localized in the lymph node (Figure 1E).

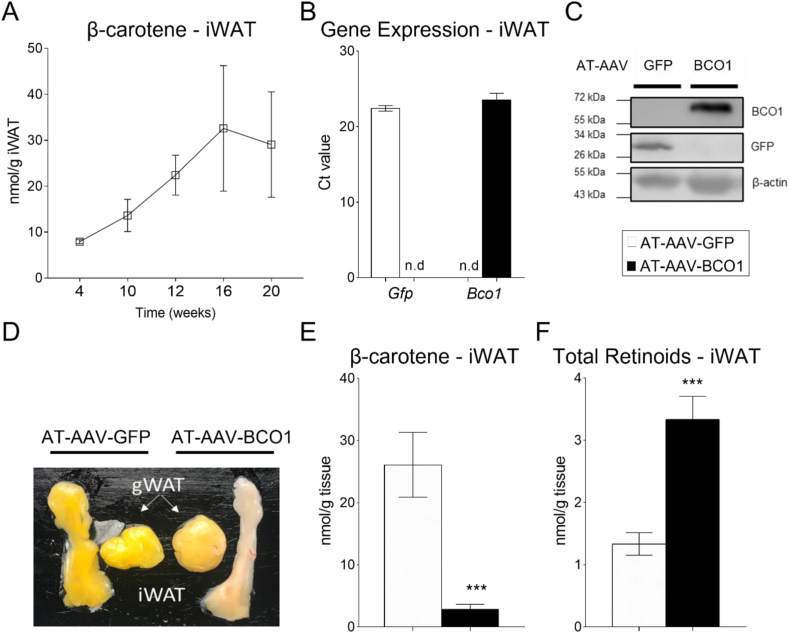

3.2. Characterization of AT-AAV-BCO1

The most visually striking phenotype of Bco1−/− mice is the accumulation of β-carotene in tissues, including the adipose tissue [18]. First, we performed a time-course experiment to quantify β-carotene accumulation in the iWAT of naïve, non-injected Bco1−/− mice fed a standard chow diet without vitamin A containing 50 mg/kg of β-carotene (Standard-β-carotene diet). We utilized a vitamin A deficient diet to promote vitamin A accumulation, as we previously demonstrated that the intestinal carotenoid absorption depends on retinoic acid levels in the intestine [26,27]. We observed a progressive accumulation of β-carotene over time that plateaued after 16 weeks of diet (Figure 2A), while plasma β-carotene levels reached a maximum after 10 weeks on the β-carotene diet (Supplementary Figure 1A). The mechanism(s) that regulate β-carotene accumulation are currently under investigation, but our HPLC quantifications show that it occurred independently of vitamin A deficiency. Indeed, vitamin A in plasma and tissues showed that our experimental approach did not cause vitamin A deficiency in mice (Supplementary Figure 1B–D).

Figure 2.

AT-AAV-BCO1 promotes β-carotene cleavage and retinoid production. (A) β-Carotene accumulation over time in the iWAT of Bco1−/− mice fed a standard β-carotene diet. Bco1−/− mice were injected subcutaneously on the iWAT with 1 × 10 [11] GC/mouse with AT-AAV encoding either GFP or BCO1. (B) Two weeks later, mice were harvested for mRNA expression levels of Gfp and Bco1 (C) or protein levels. (D) Adipose tissue visualization of Bco1−/− mice fed β-carotene for 10 weeks and then injected with the corresponding AT-AAVs for 10 more weeks before tissue collection. (E) β-Carotene in the iWAT, and (F) Non-polar retinoid quantification by HPLC. Values are represented as means ± SEMs. n = 5 mice/genotype and AT-AAV. Statistical differences were evaluated using a two-tailed student's t-test. ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Next, we designed an AT-AAV encoding BCO1 (AT-AAV-BCO1) with the goal of expressing BCO1 in the adipocyte of Bco1−/− mice. We inserted a pre-cloned cDNA encoding murine BCO1 (GENEWIZ) using the backbone created by Reilly's group [19] (Amengual et al., 2011). Once AT-AAV-GFP or AT-AAV-BCO1 were generated, we injected it into Bco1−/− mice to measure gene expression in the iWAT. Both AT-AAVs increased GFP and BCO1 mRNA and protein levels in the iWAT (Figure 2B, C).

To examine whether our AT-AAV-BCO1 encodes a functional BCO1 protein, we fed the Bco1−/− mice a Standard-β-carotene diet for 10 weeks and injected them with AT-AAV-BCO1 or AT-AAV-GFP as a control. Ten weeks later, we harvested the mice and inspected the iWAT and the gWAT as target and off-target tissues for our AT-AAVs, respectively (Figure 2D). Visual observation and HPLC quantification showed that the AT-AAV-BCO1 depleted the β-carotene stores in the iWAT (Figure 2D, E). An increase in non-polar retinoids accompanied the depletion of β-carotene in the iWAT (Figure 2F).

In our efforts to optimize our experimental approach, we also carried out dose–response experiments using AT-AAV-BCO1 injected subcutaneously in the iWAT. These data revealed that 1 × 10 [11] GC of AT-AAV-BCO1/mouse was adequate to stimulate β-carotene cleavage in the iWAT without major off-target BCO1 expression occurring (Supplementary Figure 2).

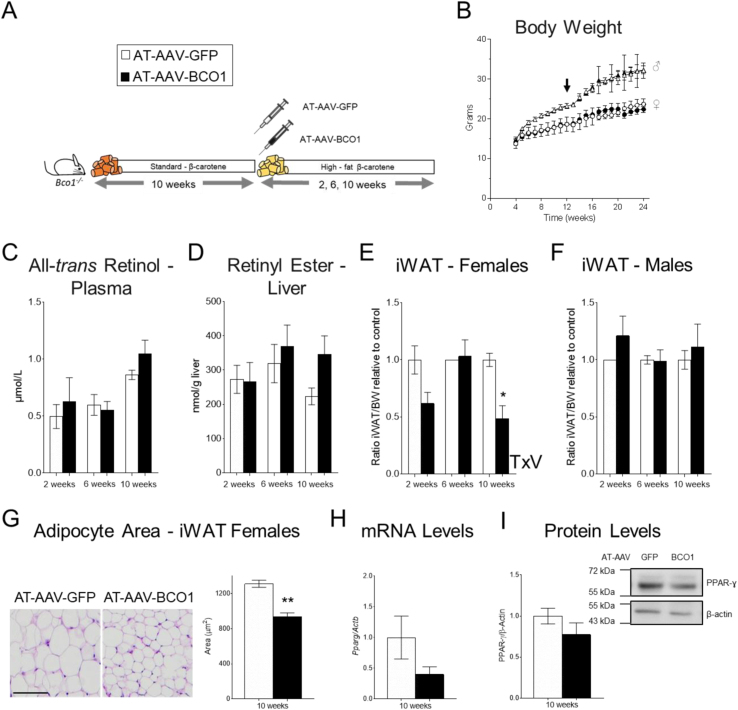

3.3. AT-AAV-BCO1 reduces adipose tissue size in female but not male Bco1−/− mice

We previously reported that β-carotene dietary supplementation in mice reduces adiposity in wild-type female mice [13]. To examine whether the local production of vitamin A in the adipocyte is responsible for this effect, we fed Bco1−/− mice a Standard-β-carotene diet for 10 weeks to promote the accumulation of β-carotene in the adipocyte. After this, we switched the mice to a vitamin A–deficient, high-fat diet supplemented with 50 mg/kg β-carotene (high-fat β-carotene diet). At this time, we also injected the mice with either AT-AAV-BCO1 or AT-AAV-GFP as a control. We harvested the mice two-, six-, and 10 weeks post-AT-AAV injections to examine the iWAT size (Figure 3A). We did not observe differences between experimental groups in food intake (data not shown) or body weight gain (Figure 3B). Systemic and hepatic vitamin A stores remained unaltered between experimental groups (Figure 3C, D).

Figure 3.

BCO1 overexpression in the iWAT reduces adipose tissue size in Bco1−/− mice fed β-carotene. (A) Experimental design. Four-week-old Bco1−/− mice were fed a standard β-carotene diet for 10 weeks. We then switched the mice to a high-fat β-carotene diet and injected them subcutaneously at the level of the iWAT with 1 × 10 [11] GC/mouse of an adipose-tissue-specific adeno-associated vector encoding either BCO1 or GFP as a control. We harvested mice two, six, and 10 weeks after injections. (B) Body weight progression. The arrow indicates the time of the AT-AAV injections. (C) Circulating retinol and (D) retinyl ester stores in the liver. (E) iWAT size compared to total body weight (BW) in females, (F) and male mice. (G) Representative micrographs and adipocyte mean sectional area of iWAT sections in female mice. (H) iWAT Pparg mRNA expression, (I) and protein quantification were done by RT-PCR and Western blot, respectively. Values are means ± SEMs. n = 5 mice/gender/genotype and AT-AAV. Statistical differences were evaluated by two-tailed student's t-test or two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post-hoc test (P < 0.05) ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. T × V; interaction effect of time (T) and AAV (V) by two-way ANOVA.

We next examined the effect of AT-AAV-BCO1 on adipose tissue size by comparing iWAT weight to the animal's total body weight at the moment of the sacrifice. Female mice harvested 10 weeks after AT-AAV-BCO1 injection showed a significant reduction in iWAT size compared to littermates injected with AT-AAV-GFP (Figure 3E). This effect was sex-dependent, as male mice injected with AT-AAV-BCO1 did not show differences in iWAT size compared to littermate controls injected with AT-AAV-GFP (Figure 3F). Bco1 mRNA levels increased over time, in agreement with previous reports showing the sustained effect of AAV vectors [28,29] (Supplementary Figure 3A).

Morphometric analyses showed a reduced adipocyte area in iWAT of Bco1−/− female mice injected with AT-AAV-BCO1 for 10 weeks compared to AT-AAV-GFP controls (Figure 3G). No changes were observed in Ki67 and Pcna expression levels, ruling out alterations in cell proliferation (data not shown) [30]. We observed a trend toward reducing Pparg mRNA and protein levels in iWAT homogenates, although these results failed to reach statistical significance (Figure 3H, I).

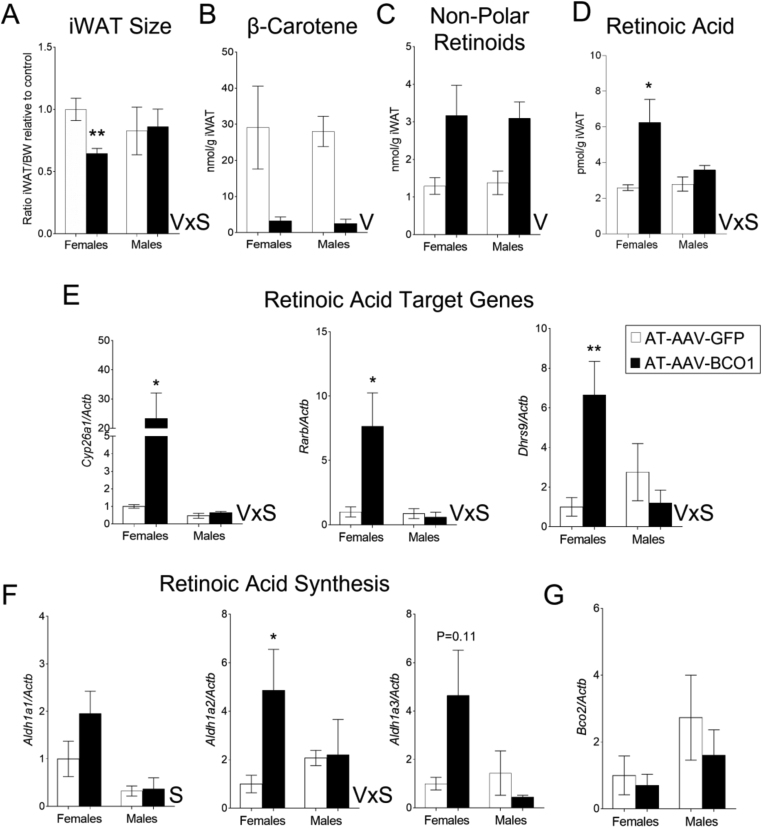

3.4. AT-AAV-BCO1 injection in Bco1−/− female mice fed β-carotene results in the production of retinoic acid

AT-AAV-BCO1 injection in the iWAT reduces adipose tissue size in Bco1−/− female mice fed β-carotene 10 weeks post AAV injection. These effects did not occur in male mice (Figure 3). To tease out the molecular mechanism behind these sex differences, we repeated our experimental approach outlined in Figure 3A and harvested our mice only 10 weeks after AT-AAV injections. As expected, the injection of AT-AAV-BCO1 in the iWAT decreased the adipose tissue size in female but not male mice (Figure 4A). We did not observe differences between sexes in β-carotene or non-polar retinoid levels (retinyl esters + retinol) in the iWAT (Figure 4B, C). We next examined the retinoic acid levels by mass spectrometry. BCO1 over-expression in Bco1−/− female mice resulted in an increase in adipose tissue retinoic acid levels; however, these changes were absent in male mice (Figure 4D). Retinoic acid levels aligned with mRNA expression levels of two classical retinoic acid-responsive genes, Cyp26a1 and Rarb [31]. Dhrs9 expression, which is also a regulated by retinoids in various experimental conditions [[32], [33], [34]], followed the same pattern as Cyp26a1 and Rarb, where only female mice injected with AT-AAV-BCO1 showed an upregulation of these transcripts in the iWAT (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

BCO1 over-expression in female Bco1−/− mice fed β-carotene results in a reduction of the iWAT accompanied by an increase in retinoic acid production. Four-week-old Bco1−/− mice were fed a standard β-carotene diet for 10 weeks. We then switched the mice to a high-fat β-carotene and injected the mice subcutaneously at the level of the iWAT with 1 × 10 [11] GC/mouse of an adipose-tissue-specific adeno-associated vector encoding either BCO1 (AT-AAV-BCO1) or GFP as a control (AT-AAV-GFP). We harvested mice 10 weeks after injections. (A) iWAT size compared to total body weight in female and male mice. (B) β-Carotene and (C) Non-polar retinoid quantifications by HPLC in iWAT. (D) Retinoic acid measurements by mass spectrometry (E) and mRNA expression of retinoic acid target genes, Cyp26a1, Rarb, and Dhrs9 in iWAT. (F) mRNA expression of Aldh1a1, Aldh1a2, and Aldh1a3, and (G) Bco2 in the iWAT. Values are means ± SEMs. n = 4–5 mice/gender/genotype, and AT-AAV. Statistical differences were evaluated by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post-hoc test (P < 0.05) ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. V; effect of AAV by two-way ANOVA, and VxS; interaction effect by two-way ANOVA between AAV (V) and sex (S).

The action of BCO1 on β-carotene results in the formation of two retinal molecules that can be either reduced to retinol or oxidized to retinoic acid [35]. Hence, we evaluated the expression.of the three enzymes implicated in the conversion of retinal to retinoic acid [36]. Aldh1a1, the main enzyme implicated in the formation of retinoic acid in the adipocyte [37], was upregulated in the iWAT of female mice independently of the AT-AAV (Figure 4F). Aldh1a2 mRNA expression was increased in female mice injected with AT-AAV-BCO1 compared to the other experimental groups (Figure 4F). Aldh1a3 expression levels followed the same trend as Aldh1a2, although they failed to reach statistical significance, according to two-way ANOVA (Figure 4F). Expression levels of BCO2, a mitochondrial enzyme implicated in carotenoid cleavage [22], remained unaltered between groups (Figure 4G).

Previous research suggested that BCO1 influences lipid metabolism independently of its role in vitamin A formation [38]. To rule out any effect of BCO1 over-expression per se on adipose tissue size, we repeated our experimental approach utilizing diets lacking β-carotene, the primary substrate of BCO1. We fed Bco1−/− mice a standard vitamin A–deficient diet without β-carotene for 10 weeks. After this period, we injected the mice with AT-AAV-BCO1 or AT-AAV-GFP in the iWAT and switched the mice to a high-fat diet containing 4 IU/kg of vitamin A (High-fat vitamin A diet). Ten weeks after injections, mice were harvested for tissue analysis. In the absence of β-carotene, AT-AAV-BCO1 did not alter iWAT size in either female or male mice (Supplementary Figure 4).

3.5. The conversion of β-carotene to vitamin A in adipose tissue allografts fails to alter hepatic or systemic vitamin A homeostasis

Off-target expression can impede the implementation of gene therapy using AAV strategies [39]. Despite our efforts to limit BCO1 expression to the iWAT, we observed marginal expression of BCO1 in the liver and the gWAT (Supplementary Figure 3B, C). Additionally, these results were accompanied by decreased circulating and tissue β-carotene levels in AT-AAV-BCO1 injected mice (Supplementary Figure 3D–F).

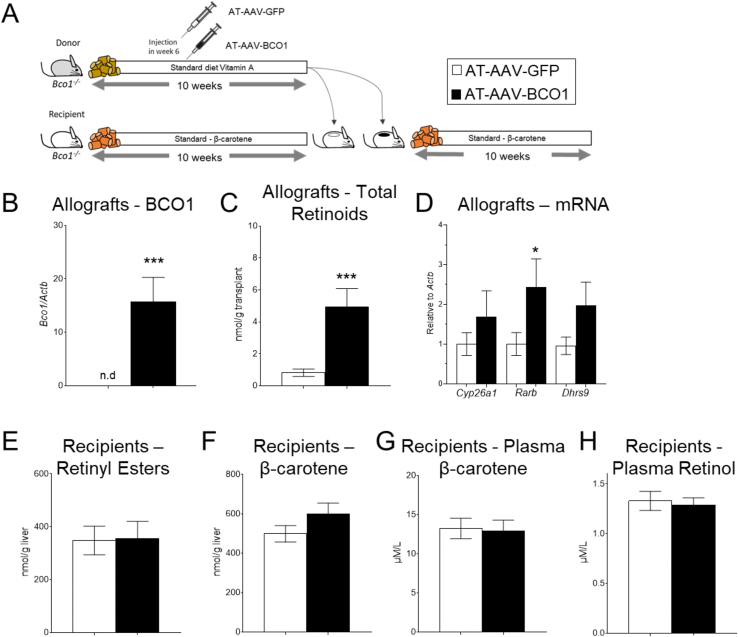

To examine whether adipose tissue over-expressing BCO1 is sufficient to alter systemic β-carotene and vitamin A levels, we performed an adipose tissue transplant experiment. Adipose tissue recipient Bco1−/− mice were fed a standard β-carotene diet, while sex-matched donor siblings were fed a standard-diet with 4,000 IU of vitamin A/kg for 10 weeks. After six weeks on the diet, the donor mice received either AT-AAV-BCO1 or AT-AAV-GFP. To avoid AT-AAV leaking into other tissues, donor mice were sacrificed four weeks after AAV injections to harvest the iWAT to transplant it into recipient mice. After the surgeries, we continued feeding our recipient mice a standard β-carotene diet for six weeks before tissue harvesting (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Effect of BCO1 over-expression in adipose tissue allografts in vitamin A homeostasis. (A) Experimental design. Four-week-old Bco1−/− littermate mice were split into donor and recipient mice. Donor mice were fed a standard diet with vitamin A for 10weeks. Six weeks into the intervention, mice were injected subcutaneously at the level of the iWAT with 1 × 10 [11] GC/mouse of an adipose-tissue-specific adeno-associated vector encoding either BCO1 (AT-AAV-BCO1) or GFP as a control (AT-AAV-GFP). Recipient mice were fed a standard β-carotene diet for 10 weeks. At the end of the intervention, we transplanted 100 mg of iWAT from donor mice into recipient mice. Recipient mice were maintained on a standard-β-carotene diet for six more weeks before sacrifice. (B) mRNA Bco1 expression and (C) non-polar retinoids in allografts. (D) mRNA expression of Cyp26a1, Rarb, and Dhrs9 in allografts. (E) Retinyl ester stores and (F) β-carotene levels in the liver of recipient mice. (G) Plasma β-carotene and (H) plasma retinol in recipient mice. Values are means ± SEMs. n = 4–5 mice/genotype, and AT-AAV. Statistical differences were evaluated by two-tailed student's t-test (P < 0.05) ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Bco1 mRNA expression and non-polar retinoid analyses in the allograft showed that the implants of those mice injected with AT-AAV-BCO1 produced retinoids utilizing circulating β-carotene in the recipient animal (Figure 5B, C). These results were supported by the expression of retinoic acid-sensitive genes in the allograft (Figure 5D). Off-target Bco1 mRNA expression in the liver of recipient mice was not detected (data not shown). Hepatic and systemic β-carotene and vitamin A stores in recipient mice remained unaltered between groups (Figure 5E–H).

4. Discussion

Work carried out over 40 years ago highlighted the role of retinoic acid as a potent inhibitor of adipocyte differentiation [40]. Later studies showed that retinoic acid increases fatty acid oxidation and thermogenesis in mature adipocytes [41,42], findings that were in agreement with studies in rodents, where retinyl ester and retinoic acid supplementation reduce adiposity, stimulates adipose tissue browning, and increases thermogenesis [8,43,44]. These results align with clinical data suggesting that a greater vitamin A and retinoic acid status are associated with a reduction in fatty liver and decreased obesity [45,46]. However, clinical interventions utilizing vitamin A or retinoic acid to treat obesity have been hampered due to concerns about the teratogenic effect of retinoids [47]. These concerns have also been raised in the case of supplementation strategies utilizing β-carotene, which is the main precursor of vitamin A in mammals [48,49].

β-Carotene accumulates in human adipose tissue [50], but whether it serves as a pro-vitamin A precursor in adipocytes remains unexplored. To this end, we generated and optimized a novel expression vector to induce murine BCO1 expression in mature adipocytes. Because wild-type mice do not accumulate carotenoids in tissues, we relied on Bco1−/− mice fed a diet containing 50 mg/kg of β-carotene. Based on our previous studies, we used vitamin A–free diets to favor intestinal β-carotene uptake since Bco1−/− mice accumulate neglectable levels of this carotenoid when vitamin A is present in their feed [13,26]. Despite the absence of dietary vitamin A, mice did not show any sign of vitamin A deficiency in circulation, adipose tissue, or liver (Supplementary Figure 1), in agreement with our previous results using diets depleted of vitamin A [17].

Data from our two independent experiments show that AT-AAV-BCO1 administered for 10 weeks directly to the iWAT reduces adipose tissue size in female but not male mice (Figure 3, Figure 4A). These sex differences agree with previous data in which β-carotene supplementation only reduced adiposity in wild-type female mice [13], highlighting the importance of including sex as a biological factor in biomedical studies [51]. These sex differences do not apply to all the effects of β-carotene on lipid metabolism. We recently reported that β-carotene reduces plasma cholesterol in female and male Ldlr−/− mice, suggesting that these sex differences could be adipose tissue specific [17]. Indeed, our retinoic acid measurements helped us to provide a mechanistic explanation of our observations, where AT-AAV-BCO1 alone increased retinoic acid levels in female but not male Bco1−/− mice fed β-carotene (Figure 4D). These findings align with those from Dr. Joseph L. Napoli's group, which showed sexual dimorphism in several experimental models of obesity. His studies on the role of retinol dehydrogenase 1 and 10, which catalyze the oxidation of retinol to retinal, highlight the importance of studying both genders in metabolic studies in general, and vitamin A metabolism in particular [52].

Following the liver, the adipose tissue is the second most important storage of vitamin A and carotenoids in mammals, including humans [[53], [54], [55]]. Adipocytes store both β-carotene and retinoids in lipid droplets, which raises an important question: What is the preferred substrate in the formation of retinoic acid in the adipocyte? Dr. Johannes von Lintig's group partially answered this question when they observed that the supplementation of β-carotene in cultured 3T3 adipocytes stimulates retinoic acid production more efficiently than in those cells exposed to retinol [12]. As it occurs with retinoic acid, retinal is highly unstable and is quickly reduced to retinol or oxidized to retinoic acid. Kinetic and expression level studies suggest ALDH1A1 and ALDH1A2 are the most important enzymes for retinoic acid synthesis [56]. ALDH1A3 seems to only affect retinoic acid production in certain tumor cells and the eye [57,58]. ALDH1A1 expression is the predominant ALDH1A subfamily member in both human and rodent subcutaneous WAT (= iWAT)s [59]. Our study shows that Aldh1a1 mRNA levels was greater in female mice than male mice, in line with our retinoic acid measurements (Figure 4D). Future studies should aim to combine the expression of AT-AAV-BCO1 with the pharmacological modulation of ALDH1A1 activity with the goal of studying the exact contribution of this enzyme in β-carotene-derived retinal and retinoic acid in the adipocyte.

Our dose–response experiments revealed that the subcutaneous injection of AT-AAV-BCO1 at high doses leads to the off-target upregulation of BCO1 in tissues such as the gWAT and the liver. These changes were accompanied with a reduction of tissue β-carotene levels (Supplementary Figure 2). These data could represent a setback in the utilization of AT-AAV vectors to promote vitamin A formation in adipocytes. Dosage and delivery routes should be carefully tested, as aberrant BCO1 over-expression could result in alterations in vitamin A levels that could lead to toxicity or teratogenic effects in pregnant women [60]. Our adipose tissue transplant study shed some light on the contribution of BCO1 over-expression in the adipose tissue when tissues were completely spared from off-target AT-AAV expression. We observed that the transplantation of approximately 100 mg of iWAT extracted from donor mice failed to alter systemic levels of vitamin A (Figure 5). These results align with those of Dr. William S. Blaner's group. They utilized a transgenic model over-expressing the retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) in the WAT, which showed that adipocyte-specific RBP4 over-expression does not alter systemic or hepatic vitamin A homeostasis [61].

Despite observing an increase in non-polar retinoids in those transplants in which BCO1 was over-expressed, these results were not accompanied by a depletion of systemic β-carotene levels (Figure 5C, G). Previous studies suggest using approximately 1000 mg of WAT for each transplant, rather than 100 mg as we did in our study, would be necessary to achieve the desired experimental outcomes [62]. It is also possible that a longer time was necessary to observe alterations in the recipient mice, suggesting that further studies will be necessary to establish the net contribution of WAT BCO1 over-expression to systemic β-carotene and vitamin A.

In summary, our results reveal that β-carotene accumulated in the adipose tissue can be mobilized to form vitamin A by the action of BCO1. In female mice, β-carotene cleavage results in the production of retinoic acid, a reduction in adipose tissue and adipocyte size. Our results open a novel avenue to mitigate obesity and obesity-related diseases by targeting accumulated carotenoids in human adipose tissues, and possibly other organs such as the liver.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially funded by NIH grant 1R01HL147252, the USDA NIFA program (W4002), and the Division of Nutritional Science Program 20/20 ILLU-698-916. We thank Kate Epstein for her help editing the manuscript. We thank Dr. Earl Harrison for sharing with us the BCO1 antibody.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101640.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest exists.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Cohena P., Spiegelmanb B.M. Cell biology of fat storage. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:2523–2527. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-10-0749. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronel J., Pinos I., Amengual J. β-carotene in obesity research: technical considerations and current status of the field. Nutrients. 2019;11:842. doi: 10.3390/nu11040842. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller A.P., Coronel J., Amengual J. The role of β-carotene and vitamin A in atherogenesis: evidences from preclinical and clinical studies. Biochim Biophys Acta, Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2020;1865 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158635. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Lintig J., Vogt K. Filling the gap in vitamin A research. Molecular identification of an enzyme cleaving β-carotene to retinal. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11915–11920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki M., Tomita M. Genetic variations of vitamin A-absorption and storage-related genes, and their potential contribution to vitamin A deficiency risks among different ethnic groups. Front Nutr. 2022;9:743. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.861619. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Byrne S.M., Blaner W.S. Retinol and retinyl esters: biochemistry and physiology. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:1731–1743. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R037648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercader J., Palou A., Luisa Bonet M. Induction of uncoupling protein-1 in mouse embryonic fibroblast-derived adipocytes by retinoic acid. Obesity. 2010;18:655–662. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercader J., Ribot J., Murano I., Felipe F., Cinti S., Palou A. Remodeling of white adipose tissue after retinoic acid administration in mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5325–5332. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonet M.L., Puigserver P., Serra F., Ribot J., Vazquez F., Pico C., et al. Retinoic acid modulates retinoid X receptor α and retinoic acid receptor α levels of cultured brown adipocytes. FEBS Lett. 1997;406:196–200. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serra F., Bonet M.L., Puigserver P., Oliver J., Palou A. Stimulation of uncoupling protein 1 expression in brown adipocytes by naturally occurring carotenoids. Int J Obes. 1999;23:650–655. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry D.C., Noy N. All- trans -retinoic acid represses obesity and insulin resistance by activating both peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor β/δ and retinoic acid receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3286–3296. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01742-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lobo G.P., Amengual J., Li H.N., Golczak M., Bonet M.L., Palczewski K., et al. β,β-Carotene decreases peroxisome proliferator receptor γ activity and reduces lipid storage capacity of adipocytes in a β,β-carotene oxygenase 1-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27891–27899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.132571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amengual J., Gouranton E., van Helden Y.G., Hessel S., Ribot J., Kramer E., et al. Beta-carotene reduces body adiposity of mice via BCMO1. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross A.C., Zolfaghari R. Cytochrome P450s in the regulation of cellular retinoic acid metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2011;31:65–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmadian M., Suh J.M., Hah N., Liddle C., Atkins A.R., Downes M., et al. Pparγ signaling and metabolism: the good, the bad and the future. Nat Med. 2013;19:557–566. doi: 10.1038/nm.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amengual J., et al. β-Carotene oxygenase 1 activity modulates circulating cholesterol concentrations in mice and humans. J Nutr. 2020;150:2023–2030. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X., Pinos I., Abraham B.M., Barrett T.J., von Lintig J., et al. β-Carotene conversion to vitamin A delays atherosclerosis progression by decreasing hepatic lipid secretion in mice. J Lipid Res. 2020;61:1491–1503. doi: 10.1194/jlr.RA120001066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hessel S., Eichinger A., Isken A., Amengual J., Hunzelmann S., Hoeller U., et al. CMO1 deficiency abolishes vitamin a production from β-carotene and alters lipid metabolism in mice. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33553–33561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706763200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’neill S.M., Hinkle C., Chen S.J., Sandhu A., Hovhannisyan R., Stephan S., et al. Targeting adipose tissue via systemic gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2014;21:653–661. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parra P., Serra F., Palou A. Moderate doses of conjugated linoleic acid isomers mix contribute to lowering body fat content maintaining insulin sensitivity and a noninflammatory pattern in adipose tissue in mice. JNB (J Nutr Biochem) 2010;21:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanford K.I., Middelbeek K.I., Townsend K.L., An D., Nygaard E.B., Hitchcox K.M., et al. Brown adipose tissue regulates glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:215–223. doi: 10.1172/JCI62308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amengual J., Lobo G.P., Golczak M., Li H.N., Klimova T., Hoppel C.L., et al. A mitochondrial enzyme degrades carotenoids and protects against oxidative stress. Faseb J. 2011;25:948–959. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-173906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amengual J., Golczak M., Palczewski K., Von Lintig, Lecithin J. Retinol acyltransferase is critical for cellular uptake of vitamin A from serum retinol-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24216–24227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.353979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kane M.A., Napoli J.L. Quantification of endogenous retinoids. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;652:1–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-325-1_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghuvanshi S., Reed V., Blaner W.S., Harrison E.H. Cellular localization of β-carotene 15,15′ oxygenase-1 (BCO1) and β-carotene 9′,10′ oxygenase-2 (BCO2) in rat liver and intestine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;572:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller A.P., Black M., Amengual J. Fenretinide inhibits vitamin A formation from β-carotene and regulates carotenoid levels in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2022;1867 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2021.159070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobo G.P., Amengual J., Baus D., Shivdasani R.A., Taylor D., von Lintig J. Genetics and diet regulate vitamin A production via the homeobox transcription factor ISX. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:9017–9027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi X., Shan Z., Ji Y., Guerra V., Alexander J.C., Ormerod B.K., et al. Sustained AAV-mediated overexpression of CRF in the central amygdala diminishes the depressive-like state associated with nicotine withdrawal. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4 doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.25. e385–e385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler P.D., Podsakoff G.M., Chen X., McQuinston S.A., Colosi P.C., Matelis L.A., et al. Gene delivery to skeletal muscle results in sustained expression and systemic delivery of a therapeutic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14082–14087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juríková M., Danihel Ľ., Polák Š., Varga I. Ki67, PCNA, and MCM proteins: markers of proliferation in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Acta Histochem. 2016;118:544–552. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2016.05.002. Preprint at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balmer J.E., Blomhoff R. Gene expression regulation by retinoic acid. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1773–1808. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r100015-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klyuyeva A.V., Belyaeva O.V., Goggans K.R., Krezel W., Popov K.M., kedishvili N.Y., et al. Changes in retinoid metabolism and signaling associated with metabolic remodeling during fasting and in type I diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2021;296 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu L., Chaudhary S.C., Atigadda V.R., Harville S.R., Elmets C.A., Muccio D.D., et al. Retinoid X receptor agonists upregulate genes responsible for the biosynthesis of all-trans-retinoic acid in human epidermis. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soref C.M., Di Y.P., Hayden L., Zhao Y.H., Satre M.A., Wu R. Characterization of a novel airway epithelial cell-specific short chain alcohol dehydrogenase/reductase gene whose expression is up-regulated by retinoids and is involved in the metabolism of retinol. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24194–24202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagao A. Oxidative conversion of carotenoids to retinoids and other products. J Nutr. 2004;134:237S–240S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.1.237S. Oxford Academic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kedishvili N.Y. Retinoic acid synthesis and degradation. Subcell Biochem. 2016;81:127–161. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-0945-1_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrosino J.M., Disilvestro D., Ziouzenkova O. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1: friend or foe to female metabolism? Nutrients. 2014;6:950–973. doi: 10.3390/nu6030950. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim Y.K., Zuccaro M.V., Costabile B.K., Rodas R., Quadro L. Tissue- and sex-specific effects of β-carotene 15,15′ oxygenase (BCO1) on retinoid and lipid metabolism in adult and developing mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;572:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer K.B., Collins H.K., Callaway E.M. Sources of off-target expression from recombinasedependent AAV vectors and mitigation with cross-over insensitive ATG-out vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:27001–27010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915974116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarz E.J., Reginato M.J., Shao D., Krakow S.L., Lazar M.A. Retinoic acid blocks adipogenesis by inhibiting C/EBPbeta-mediated transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1552–1561. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercader J., Granados N., Madsen L., Felipe F., Palou A., Kristiansen K., et al. All-trans retinoic acid increases oxidative metabolism in mature adipocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;20:1061–1072. doi: 10.1159/000110717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tourniaire F., Musinovic H., Gouranton E, Astier J., Marcotorchino J., Arreguin A., et al. All-trans retinoic acid induces oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondria biogenesis in adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:1100–1109. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M053652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berry D.C., DeSantis D., Soltanian H., Croniger C.M., Noy N. Retinoic acid upregulates preadipocyte genes to block adipogenesis and suppress diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2012;61:1112–1121. doi: 10.2337/db11-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonet M.L., Ribot J., Felipe F., Palou A. Vitamin A and the regulation of fat reserves. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1311–1321. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2290-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trasino S.E., Tang X.H., Jessurun J., Gudas L.J. Obesity leads to tissue, but not serum Vitamin A deficiency. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep15893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y., Chen H., Mu D., Fan J., Song J., Zhong Y., et al. Circulating retinoic acid levels and the development of metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:1686–1692. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piersma A.H., Hessel E.V., Staal Y.C. Retinoic acid in developmental toxicology: teratogen, morphogen and biomarker. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;72:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.05.014. Preprint at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Group, T. A.-T. B. C. C. P. S. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omenn G.S., Goodman G.E., Thornquist M.D., Balmes J., Cullen M.R., Glass A., et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1150–1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tourniaire F., Gouranton E., von Lintig J., Keijer J., Bonet M.L., Amengual J., et al. β-Carotene conversion products and their effects on adipose tissue. Genes Nutr. 2009;4:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s12263-009-0128-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clayton J.A., Collins F.S. NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature. 2014;509:282–283. doi: 10.1038/509282a. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Napoli J.L. Retinoic acid: sexually dimorphic, anti-insulin and concentration-dependent effects on energy. Nutrients. 2022;14:1553. doi: 10.3390/nu14081553. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frey S.K., Vogel S. Vitamin A metabolism and adipose tissue biology. Nutrients. 2011;3:27–39. doi: 10.3390/nu3010027. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blaner W.S., Li Y., Brun P.J., Yuen J.J., Lee S.A., Clugston R.D. Vitamin A absorption, storage and mobilization. Subcell Biochem. 2016;81:95–125. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-0945-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parker R.S. Carotenoids in human blood and tissues. J Nutr. 1989;119:101–104. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.1.101. Preprint at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kedishvili N.Y. Enzymology of retinoic acid biosynthesis and degradation. JLR (J Lipid Res) 2013;54:1744–1760. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R037028. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mory A., Ruiz F.X., Dagan E., Yakovtseva E.A., Kurolap A., Pares X., et al. A missense mutation in ALDH1A3 causes isolated microphthalmia/anophthalmia in nine individuals from an inbred Muslim kindred. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:419–422. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Durinikova E., Kozovska Z., Poturnajova M., Plava J., Cierna Z., Babelova A., et al. ALDH1A3 upregulation and spontaneous metastasis formation is associated with acquired chemoresistance in colorectal cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2018;18 doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4758-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reichert B., Yasmeen R., Jeyakumar S.M., Yang F., Thomou T., Alder H., et al. Concerted action of aldehyde dehydrogenases influences depot-specific fat formation. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:799–809. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lammer E.J., Chen D.T., Hoar R.M., Agnich N.D., Benke P.J., Braun J.T., et al. Retinoic acid embryopathy. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:837–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510033131401. Preprint at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee S.A., Yuen J.J., Jiang H., Kahn B.B., Blaner W.S. Adipocyte-specific overexpression of retinol-binding protein 4 causes hepatic steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2016;64:1534–1546. doi: 10.1002/hep.28659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tran T.T., Yamamoto Y., Gesta S., Kahn C.R. Beneficial effects of subcutaneous fat transplantation on metabolism. Cell Metabol. 2008;7:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.