Abstract

Background

Rifampicin resistance (RR) is a surrogate marker of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. The aim of this study is to determine the frequency of the commonly mutated probes for rpoB gene and locate the residential areas of the Rifampicin Resistant-TB (RR-TB) patients in a high endemic zone of Northeast India.

Methods

Archived data of 13,454 Xpert MTB/RIF reports were evaluated retrospectively between 2014 and 2021. Socio-demographic and available clinical information were reviewed and analyzed for RR-TB cases only. Logistic Regression was used to analyze the parameters with respect to probe types. P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

2,894 patients had Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection out of which 460 were RR-TB, which was most prevalent among 25–34 years. The most common mutation occurred in probe A (25.9 %) followed by E (23.5 %), D (9.8 %), B (2.6 %) and the least in C (0.2 %). High prevalence (34.3 %) of probe mutation combinations were also found: probes AB (0.4 %), AD (32.8 %), AE (0.4 %), DE (0.2 %) and ADE (0.4 %). Seventeen patients (3.7 %) were found without any missing probes. RR-TB patients were mostly located in Aizawl North –III, South –II and East –II constituencies.

Conclusion

This study provides genetic pattern of drug resistance accountable for RR over the past years in Mizoram which will help local clinicians in the initiation of correct treatment. Also, our findings provide a baseline data on the magnitude of RR-TB within the state and identification of the residential areas can help local health authorities in planning surveillance programs to control the spread of RR-TB.

Keywords: Xpert MTB/RIF, Probe mutations, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mizoram, Northeast India

1. Introduction

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is a form of tuberculosis (TB) infection which is caused by a bacterium known as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is resistant to two of the most potent anti-TB drugs, rifampicin (RIF) and isoniazid (INH) [1]. Rifampicin Resistance (RR) is a key indicator of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, since >90 % resistance observed are also isoniazid resistant [2], [3]. According to WHO guidelines, the identification of MDR/RR-TB requires further employment of different tests including bacteriological confirmation of both TB along with drug resistance testing using rapid molecular tests such as Xpert/MTB RIF, other sequencing technologies or solid or liquid culture method [4].

Introduction of WHO approved Xpert/MTB RIF assay (Cepheid, USA) has revolutionized the diagnosis of TB since it is capable of simultaneously detecting M. tuberculosis and the mutations that confer RR [5], [6]. RIF being the key first line anti-TB drug inhibits DNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity in susceptible cells. This appears to occur as a result of the drug binding in the polymerase subunit facilitating direct blocking of RNA elongation.

Mizoram is situated in the north eastern part of India and shares borders with Myanmar and Bangladesh. It is the least populous state in India after Sikkim, having a population estimate of 1.26 million in 2021 (https://www.populationu.com/in/mizoram-population). Currently, among the laboratory tests available for TB, smear microscopy along with Xpert MTB/RIF assay are the only diagnostic tools implemented in the state. Xpert MTB/RIF is being utilized by Mizoram since the end of 2014 and from September 2017, it is being used as a Universal Drug Susceptibility Test. Despite the tremendous efforts and progress achieved by National Tuberculosis Eradication Program (NTEP) (erstwhile Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program), TB is still a burden in certain peripheral areas of India such as Mizoram. A PubMed and Google Scholar search strategy using relevant keywords (such as Northeast India, Xpert MTB/RIF, Genexpert, Mizoram RR-TB) did not provide any information on rpoB gene mutations from North East India. Due to the unavailability of information on the underlying genetic pattern of drug resistance from the state, which can provide insights into the pattern of mutation accountable for RR over the past years, this retrospective study was taken up to understand the magnitude of RIF resistance TB (RR-TB) using molecular diagnostic tools.

The objectives of this study were: 1) To determine the frequency of the commonly mutated probes for rpoB gene in the 81 bp Rifampicin Resistance Determining Region (RRDR) of M. tuberculosis via. Xpert MTB/RIF and compare the frequencies of gene mutations in different geographical areas, 2) determine the association of the gene mutation with demographic factors, and 3) To understand the highly prevalent RR-TB residential areas for prediction of future epidemics.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical clearance

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Mizoram (B.12018/1/13-CH (A)/IEC/63). All the patients who participated had provided a written consent at the time of testing their samples.

2.2. Study population and data collection

As per the Health and Family Welfare Department, Government of Mizoram, during April 2021 to March 2022, 6,745 people were examined for TB out of which 1,698 were diagnosed and notified from both public and private sectors. In addition, 2,634 patients were tested for drug resistance of which 109 were diagnosed as RR-TB. For the current study, data were evaluated retrospectively from archived results for all the types of specimens received and tested using Xpert MTB/RIF assay at District TB Center, Falkawn and Synod Hospital, Durtlang, Mizoram, Northeast India from December 2014 to May 2021. A total number of 13,927 patients suspected for TB were subjected to Xpert/MTB RIF assay and out of which 473 had invalid, error, duplicates or no results and hence were removed. 13,454 patients were included in the study. RR result delivered through Xpert/MTB RIF was solely relied upon and no additional screening was performed. Socio-demographic and available clinical information were reviewed and analyzed for RR-TB cases only. Previous studies employing Xpert/MTB RIF system describing probe mutations conferring RR were retrieved from online sources and compared with the results of the present study to analyze the differences or similarities in the mutation pattern of the rpoB gene region.

2.3. Laboratory diagnosis

Previous studies have frequently stated the presence of up to 95 % of Rifampicin Resistance (RR) to be associated with mutations in the 81-bp hotspot region (codons 507–533 of the E. coli numbering system/ codons 426–452 of the M. tuberculosis numbering system) of the rpoB gene and is known RRDR. Xpert/MTB RIF is a cartridge-based, automated, hemi-nested real-time PCR system that utilizes five overlapping probes named as Probe A (codons 507–511), Probe B (codons 511–518), Probe C (codons 518–523), Probe D (codons 523–529) and Probe E (codons 529–533) [7], [8]. To delineate the resistance associated mutations for M. tuberculosis, a numbering system based on E. coli sequence annotation circa 1993 was used. Whole genome sequencing is an alternative numbering system based on M. tuberculosis rpoB sequence [9]. However, the nomenclature used in this study follows the E. coli numbering system.

The assay for 13,454 patients included in the study was performed in accordance to the manufacturer’s instructions using Xpert MTB/RIF assay G4 (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with a sensitivity of 94.4 % and specificity of 98.3 % for diagnosis of RR [10]. The Xpert MTB/RIF provides semi-quantitative results based on the probes’ Cycle Threshold (Ct) i.e., number of PCR cycles required to amplify the DNA of M. tuberculosis to a detectable level. Hence, the results are reported as “High” (Ct < 16), “Medium (Ct 16–22), “Low” (Ct 22–28) or “Very low” (Ct > 28). Presence of rpoB mutations can change the dynamics of hybridization between the amplicon and the probes(s) which corresponds to the mutated site thereby causing a difference between the Ct values of the probes and when hybridization is inhibited, it results in missing probes. However, in cases without mutated rpoB, all the 5 probes match exactly to the amplified MTB DNA. The G4 version of Xpert MTB/RIF software interprets sample results as resistant to RIF, if the difference between two probes (the first and last Ct) is > 4 cycles (ΔCt > 4) [11].

The tested patients were categorized into two (pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB). Results of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay were categorized into the following: 1) M. tuberculosis not detected. 2) M. tuberculosis detected; RR not detected. 3) M. tuberculosis detected; RR Detected. 4) Invalid. 5) Error. 6) No result. For the tests having M. tuberculosis detected along with RR detected, the missed probe types, bacteria load, sample type and available demographic data were assessed.

2.4. Household identification

The localities of patients belonging to Aizawl District were entered in excel sheet, coded, segregated, and mapped with the constituency they belong using the following link as a reference (https://ceo.mizoram.gov.in/state_profile). The frequencies were calculated (N/460x100) and was further arranged in descending order of RR-TB prevalence.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were entered, coded and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM Corp, USA). Bivariate logistic regression analysis was used to characterize clinical and demographic variables like frequencies of specimen type, DNA quantity, probe types and gender. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to characterize the demographic variables (age group) with respect to probe types. P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic and clinical information

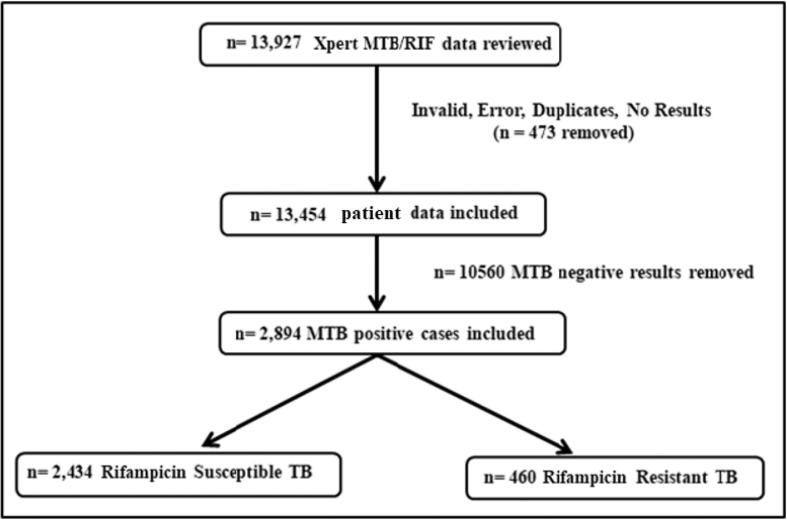

Of the 13,454 patients that were included in the study, M. tuberculosis was detected in 2,894 (21.5 %) cases, out of which 460 (15.9 %) were RR-TB detected (i.e., presence of mutation in the rpoB gene either in the form of probe drop out or in the presence of hybridization with the difference between the highest and lowest ct value as > 4) and 2,434 (84.1 %) were RR-TB not detected (i.e., absence of mutation in the rpoB gene). About 10,560 patients were Xpert/MTB RIF negative even though they presented with either of the following symptoms: prolonged cough, probable infection of the lungs, pyrexia of unknown origin and contact with TB patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for analysis of RR-TB patients by Xpert MTB/RIF.

Among the 460 RR-TB cases, 57.8 % (n = 266) were males and 42.2 % (n = 194) were females. The maximum number of cases were observed in the age group of 25–34 years (34.6 %) followed by 35–44 years (20.4 %), 15–24 years (19.3 %), 45–54 years (11 %), 55–64 years (6.1 %), >65 years (4.8 %), 5–14 years (2.4 %) and the least in 0–4 years (1.3 %). These age groups are further correlated with gender (Table 1). The mean age of RR-TB in this study was 34 years. The most prevalent age group among extrapulmonary TB was also between 25 and 34 years (n = 29, 44.6 %).

Table 1.

Frequency of RR-TB among different age groups in relation to gender.

| Age Group | Males (%) N = 266 |

Females (%) N = 194 |

Total (%) N = 460 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 years | 0 (0) | 6 (3.1) | 6 (1.3) |

| 5–14 years | 3 (1.1) | 8 (4.1) | 11 (2.4) |

| 15–24 years | 45 (16.9) | 44 (22.7) | 89 (19.3) |

| 25–34 years | 85 (32.0) | 74 (38.1) | 159 (34.6) |

| 35–44 years | 61 (22.9) | 33 (17.0) | 94 (20.4) |

| 45–54 years | 37 (13.9) | 14 (7.2) | 51 (11.0) |

| 55–64 years | 20 (7.5) | 8 (4.1) | 28 (6.1) |

| >65 years | 15 (5.6) | 7 (3.6) | 22 (4.8) |

3.2. Sample type vs semi-quantitative analysis (Bacillary load)

Majority of the specimens were of pulmonary origin (n = 395, 85.9 % - sputum, broncho alveolar lavage (BAL), gastric lavage, tracheal aspirate) and the remaining were extrapulmonary origin (n = 65, 14.1 % - lymph node aspirate, pleural fluid, ascitic fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, pus/abscess) from various sites.

As Xpert MTB/RIF assay can semi-quantitatively quantify DNA present in the samples, the amount of DNA (bacillary load) among the 460 RR-TB cases were segregated as follows: High bacillary load (n = 107, 23.26 %) i.e., 104 from sputum, 1 each from gastric aspirate, liver abscess and pleural fluid, respectively. Medium bacillary load (n = 129, 28 %) i.e., 125 from sputum, 3 from BAL and 1 from Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) of lymph node. Low bacillary load (n = 126, 27.39 %) i.e., 92 sputum, 11 lymph node FNAC, 9 abscess, 7 pleural fluid, 2 tracheal aspirate, 2 gastric aspirate, 1 BAL, 1 ascitic fluid and 1 Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF). Very low bacillary load (n = 98, 21.3 %) i.e., 3 abscess, 61 sputum, 1 ascitic fluid, 2 BAL, 6 CSF, 12 lymph node FNAC, 2 gastric aspirate, 11 pleural fluid.

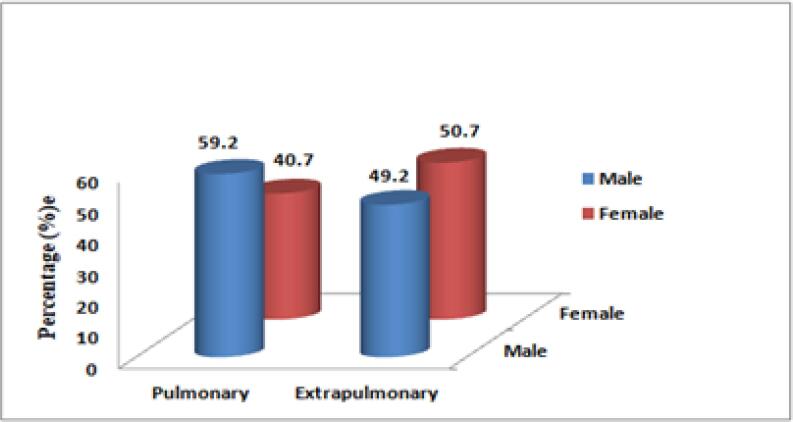

RR-TB was more prevalent among pulmonary TB as compared to extra-pulmonary TB among the males. On the contrary, RR-TB was more in females suffering from extrapulmonary TB (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of RR-TB in comparison to gender and sample type.

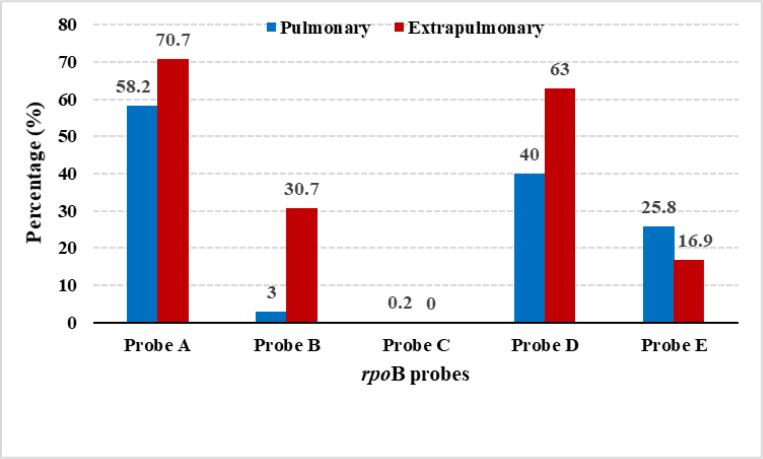

3.3. Mutation in rpoB probes between pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB

In this study, probes A, B and D had higher mutation among extrapulmonary samples as compared to pulmonary samples. Whereas, probes C and E had higher mutation among pulmonary samples (Fig. 3). The mutations in different probes with the different types of samples used for TB diagnosis is shown in Suppl. Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of rpoB probe mutation between pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB.

3.4. Mutation in rpoB probes between male and female TB patients

The mutation frequencies in males showed (i) Single probe mutation: probe A – 24.4 % (65/266), probe B- 3.8 % (10/266), probe C- 0.4 % (1/266), probe D- 7.9 % (21/266) and probe E- 28.2 % (75/266). (ii) Multiple probes mutation: probes AD- 29.3 % (78/266), probes AE- 0.8 % (2/266), probes DE- 0.4 % (1/266) and probes ADE – 0.4 % (1/266). All probes positive RR-TB were found in 5 samples. On the other hand, the mutation frequencies in females showed (i) Single probe mutation: probe A- 27.8 % (54/194), probe B- 1 % (2/194), probe C- 0 %, probe D- 12.4 % (24/194) and probe E −17 % (33/194). (ii) Multiple probes mutation: probes AB – 1 % (2/194), probes AD – 37.6 % (73/194) and probes ADE – 0.5 % (1/194). All probes positive were found in 12 samples. The results showed that mutations in probes A, B, C, E, AD, AE and DE were more frequent among males whereas probes D and AB mutations were more among females. In addition, different age groups among males and females displayed varied probe mutations (Suppl. Fig.’s 1A and 1B).

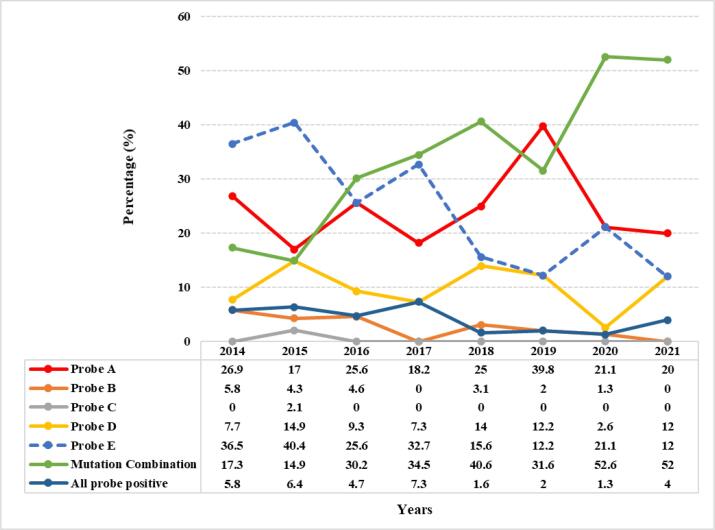

3.5. Pattern of Xpert MTB/RIF probes mutation over a period of seven years

In this retrospective study, it was observed that throughout the seven years (2014 to May 2021), single probe mutations were observed as follows: probe A (codons 507–511), n = 119 (25.9 %) had the most common mutation as compared to the other four probes. This was followed by probe E (codons 529–533), n = 108 (23.5 %), probe D (codons 523–529), n = 45 (9.8 %), probe B (codons 512–518), n = 12 (2.6 %) and probe C (codons 518–523), n = 1 (0.2 %). There was no probe B mutation in the year 2017 as well as in 2021 (till the study time period). Also, mutation in probe C (codons 518–523) was observed only once (in 2015) within these 7 years. Within these seven years, mutation combinations were also observed as follows: Probes AB (n = 2, 0.4 %), probes AD (n = 151, 32.8 %), probes AE (n = 2, 0.4 %), probes DE (n = 1, 0.2 %) and probes ADE (n = 2, 0.4 %) (Suppl. Fig. 2). However, 17 (3.7 %) RR-TB cases had no missed probe types (all probes positive) and the ΔCt for these samples were all > 4 cycles. Including all the mutations (single and multiple), the Xpert/MTB RIF probe mutations throughout seven years are shown (Fig. 4). Among the 460 RR-TB cases, 98 (21.3 %) samples had “very low” DNA quantity which is correlated with the missing probes as (i) single probe mutation: Probe A (n = 23, 23.5 %), B (n = 0), C (n = 1, 1 %), D (n = 9, 9.2 %), E (n = 15, 15.3 %), (ii) multiple probes mutation: Probes AD (n = 44, 44.9 %), AE (n = 1, 1 %) and ADE (n = 2, 2 %) and all probes positive (n = 3, 3 %).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of rpoB probes mutation over a span of seven years.

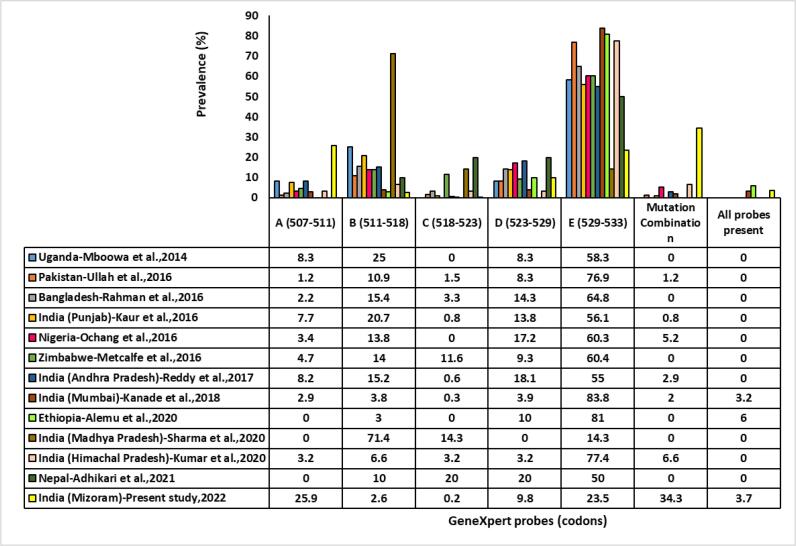

Twelve studies employing Xpert MTB/RIF were retrieved from 2014 to 2021. These studies reported probe mutations conferring RR and were compared with the current study as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the prevalence of probes mutation conferring rifampicin resistance in different countries.

3.6. Association of socio-demographic data and mutations present at each probe among all RR-TB cases

The study of the association of demographic characteristics of patients to RR showed the following: Using bivariate analysis, the frequency of mutation at probes A (p = 0.009; OR = 1.670; CI = 1.137–2.453) and D (p = 0.007; OR = 1.668; CI = 1.146–2.426) were statistically significant for female gender. For sample type, the frequency of mutation at probes A (p = 0.047; OR = 1.782; CI = 1.009–3.149) and D (p = 0.001; OR = 2.450; CI = 1.432–4.189) were statistically significant for extrapulmonary TB. The frequency of mutation at probe D site alone was also statistically significant for samples with low (p = 0.000; OR = 2.915; CI = 1.685–5.042) and very low (p = 0.000; OR = 3.283; CI = 1.837–5.867) DNA quantity (Table 2). Multivariate analysis showed that among the various age groups, the frequency of mutation at probe A site was statistically significant for younger age groups: 15–24 years (p = 0.015; OR = 2.394; CI = 1.183–4.847) and 25–34 years (p = 0.032; OR = 2.009; CI = 1.061–3.802) (Table 3). Single and mutation combination of the rpoB probes observed were statistically significant (p = 0.000) for ≤ 40 years of age.

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of the demographic and other factors influencing rpoB probe mutation.

| Categories (Age group) | Probe A |

Probe B |

Probe D |

Probe E |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | |

| 0-4 years | 0.820 | 1.217 (0.224–6.615) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5-14 years | 0.108 | 3.246 (0.771–13.661) | - | - | 0.183 | 2.500 (0.649–9.635) | 0.610 | 0.650 (0.124–3.405) |

| 15-24 years | 0.015 | 2.394 (1.183–4.847) | 0.948 | 0.952 (0.218–4.161) | 0.415 | 1.335 (0.666–2.677) | 0.686 | 0.847 (0.380 -1.891) |

| 25-34 years | 0.032 | 2.009 (1.061–3.802) | 0.157 | 0.308 (0.060–1.575) | 0.780 | 1.095 (0.578–2.077) | 0.962 | 0.983 (0.476–2.028) |

| 35-44 years | 0.156 | 1.643 (0.827–3.265) | 0.256 | 0.348 (0.056–2.153) | 0.831 | 0.927 (0.463–1.857) | 0.885 | 1.059 (0.486–2.307) |

| 55-64 years | 0.472 | 1.405 (0.557–3.543) | 0.657 | 0.593 (0.059–5.981) | 0.154 | 0.476 (0.172–1.322) | 0.962 | 0.974 (0.337–2.819) |

| >65 years | 0.074 | 2.609 (0.910–7.478) | - | - | 0.983 | 0.989 (0.358–2.733) | 0.873 | 1.096 (0.354–3.393) |

Probe C was not significant for all the categories analyzed.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the demographic factor (age) influencing rpoB gene probes mutation.

| Categories (Age group) | Probe A |

Probe B |

Probe D |

Probe E |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | OR (95 % CI) | p-value | OR (95 % CI) | p-value | OR (95 % CI) | p-value | OR (95 % CI) | |

| 0–4 years | 0.820 | 1.217 (0.224–6.615) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5–14 years | 0.108 | 3.246 (0.771–13.661) | – | – | 0.183 | 2.500 (0.649–9.635) | 0.610 | 0.650 (0.124–3.405) |

| 15–24 years | 0.015 | 2.394 (1.183–4.847) | 0.948 | 0.952 (0.218–4.161) | 0.415 | 1.335 (0.666–2.677) | 0.686 | 0.847 (0.380–1.891) |

| 25–34 years | 0.032 | 2.009 (1.061–3.802) | 0.157 | 0.308 (0.060–1.575) | 0.780 | 1.095 (0.578–2.077) | 0.962 | 0.983 (0.476–2.028) |

| 35–44 years | 0.156 | 1.643 (0.827–3.265) | 0.256 | 0.348 (0.056–2.153) | 0.831 | 0.927 (0.463–1.857) | 0.885 | 1.059 (0.486–2.307) |

| 55–64 years | 0.472 | 1.405 (0.557–3.543) | 0.657 | 0.593 (0.059–5.981) | 0.154 | 0.476 (0.172–1.322) | 0.962 | 0.974 (0.337–2.819) |

| >65 years | 0.074 | 2.609 (0.910–7.478) | – | – | 0.983 | 0.989 (0.358–2.733) | 0.873 | 1.096 (0.354–3.393) |

Reference Category: 45–54 years; Positive (No mutation).

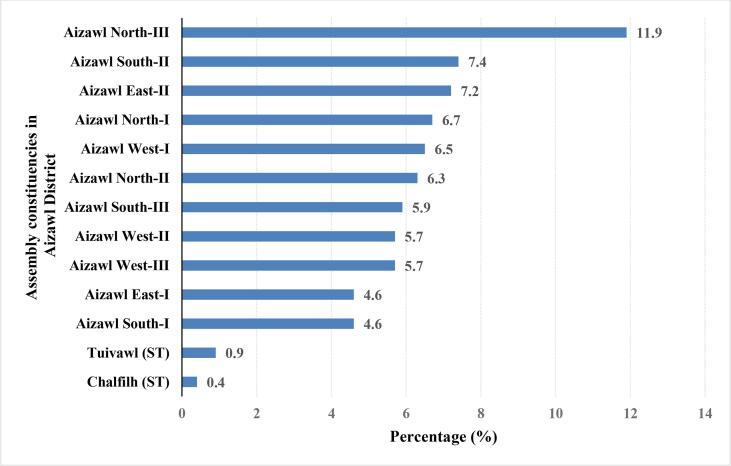

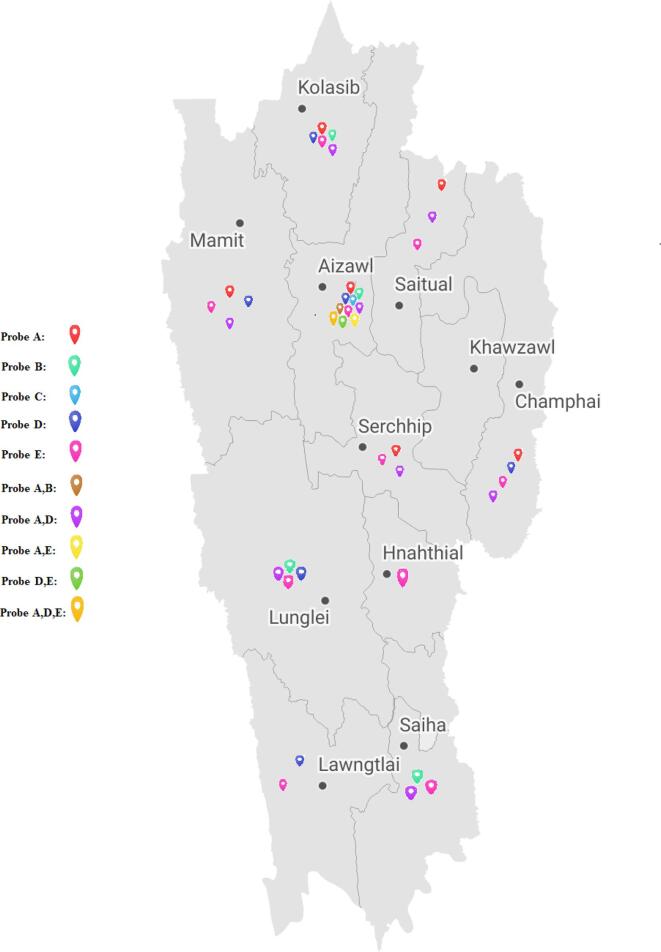

3.7. Geographical distribution of RR-TB cases in various residential areas

There are 40 constituencies in Mizoram out of which 14 are in Aizawl District (the capital). The localities of RR-TB patients belonging to Aizawl District (n = 344, 74.8 %) after segregation and mapping are given in Fig. 6. Four constituencies had multiple probe mutation combinations: Aizawl West-I (AD and DE), Aizawl North -II (AD, AB and ADE), Aizawl West-III (AD and AB), Aizawl East-I (AD, AE and ADE). Detailed information about the distribution of single and multiple probe mutations present in different constituencies is shown in Suppl. Table 2. Patients belonging to districts other than Aizawl were also enrolled and diagnosed as RR-TB in the District TB Center-Falkawn, Aizawl and Synod hospital, Durtlang, Aizawl. Among these patients, the prevalence of RR-TB as per the archived record of Xpert/MTB RIF instrument are also shown in Suppl. Fig. 3. As a whole, the geographical distribution of RR-TB in Mizoram is shown in a map (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Geographical distribution of RR-TB cases in Aizawl district, Mizoram, India. Mutation frequency (in percentage) is represented in the X-axis.

Fig. 7.

Geographical distribution of Xpert MTB/RIF probe mutations in Mizoram.

4. Discussion

TB was declared as a ‘global public health emergency’ in 1993 [12]. As per India TB Report 2020, diagnosis via. Xpert/MTB RIF is offered to all patients with smear positivity upon follow up, which includes treatment failures of first line anti-tuberculosis therapy (ATT) [13]. MDR-TB arises in clinical field either when therapy is inadequate or because of poor compliance of patients to adhere fully to an appropriate regimen or due to administration of counterfeit drug. In spite these, TB remains a huge burden especially in remote hilly areas such as Mizoram and till date reliable published information on the extent of MDR/RR-TB within the state is unavailable.

In the present study, there were 2,894 TB cases detected via. Xpert MTB/RIF from December 2014 to May 2021. Among these, the proportion of RR-TB diagnosed was 15.9 % (n = 460). Our findings are similar with the 17 % report from Central India [14]. However, higher prevalence has been reported in other parts of India such as New Delhi (17.9 %) [15] and Lucknow (27.8 %) [16]. Among the RR-TB cases, males (57.8 %) are predominant compared to females (42.2 %). A systemic review from Ethiopia reported that male gender is an identified risk factor for MDR-TB [17]. The most affected age groups observed were productive individuals between 25 and 34 years, which is in concordance with a study from China and Ethiopia [18], [19]. This can be attributed to the specific age group being more exposed to open cases of TB especially males being more susceptible to TB associated risk factors. Among the 460 RR-TB cases, 85.9 % were from pulmonary TB while 14.4 % from extrapulmonary TB. Higher DNA amount was observed in pulmonary cases (sputum) while low/very low amount of DNA was common among extrapulmonary cases which is in concordance with a study from Ethiopia [19]. Xpert MTB/RIF also has the added advantage of detecting TB in extrapulmonary cases where smear microscopy using Ziehl-Neelsen stain is often negative.

Overall, in this study, the most common RRDR rpoB gene mutation in the 81 bp were observed in codons 507–511 (25.9 %), followed by codons 529–533 (23.5 %), codons 523–529 (9.8 %), codons 511–518 (2.6 %) and the least in codons 518–523 (0.2 %) which corresponds to probes A, E, D, B and C, respectively which strongly contradicts with findings of the studies from Ethiopia, Nepal and Madhya Pradesh [19], [20], [21] where they reported no mutation in probe A region. Our results are also dis-concordant with the findings of the studies from Madhya Pradesh, India where the commonest mutation was found in probe B followed by probe C and E, while no mutations were found in probes A and D [21]. Though Sharma et al reported probe B to be the most mutated site, other previous studies conducted within and outside India had reported probe E (codon 531–533) as the commonest mutated site in the region of the RRDR rpoB gene. This might be due to higher mean relative fitness (Darwinian fitness) [22] and resistant mutants have a better ability to survive. The countries/cities reporting probe E as the most mutated site are Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Ethiopia, Nepal, Mumbai, Nigeria, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Zimbabwe, Himachal Pradesh and Uganda [7], [8], [19], [20], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. However, next to probe E mutation, the order of the prevalence of probe mutation varies from region to region wherein E is followed by B, D, A and C [8], [9], [30] and by D and B [19], [23], [24], [31]. A small proportion of probe C mutation was reported from Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Nepal, Madhya Pradesh, Mumbai, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Zimbabwe and Himachal Pradesh [7], [8], [20], [21], [23], [25], [26], [27], [28] while no probe C mutation was reported from Ethiopia, Nigeria and Uganda [19], [24], [29]. This study also reports probe C mutation occurring only once within a span of seven years. The least mutations detected by Xpert MTB/RIF in probe C might be due to this specific site of RRDR being probably less susceptible to mutations conferring the resistance or because of less selection pressure in this region.

The present study reports the most frequent mutation occurring at probe A followed by probe E. Probably due to geographical differences in M. tuberculosis lineage, the mutations may also vary. Previous studies had mostly reported the mutations observed for probe E as S531L [30], [32], probe B as D516V and D516Y and probe C as S522L [33]. Our previous sanger sequencing study from Mizoram reported the mutation at probe A region as L511P and probe D region as H526Q and H526L [34]. This study also reports high number of RR-TB detected using cycle threshold > 4 cycles (all probe positive RR-TB).

Like other studies [9], [23], [24], rpoB probe mutation combinations that were also found in this study presumably occurred due to the intrinsic or acquired ability of the bacteria to adapt to drug exposure. A study from Bangladesh had reported the occurrence of probes mutation combinations in retreatment TB cases [30]. The mutation combinations observed in this study might also be retreatment cases as information on the initiation of ATT drugs prior to testing the patient’s sample is unknown. Unlike other studies, this study reports high prevalence of probe mutation combinations (n = 158, 34.3 %) which demands deeper insights to gain rational understanding whether a specific codon mutation in the probe is being favored evolutionarily. However, these mutation combinations could be due to the fact that M. tuberculosis is G + C rich and is at a high risk for cytosine deamination, the process of which is counteracted by uracil-N-glycosylase. Organisms that are defective in the removal of uracil from DNA were reported to have a higher spontaneous mutation rate [35]. M. tuberculosis is also at an increased risk of accumulating damaged guanine nucleotides since it resides in the oxidative environment of the host macrophages. Some strains of this species might undergo hypermutability resulting in multiple rpoB gene mutations through down-regulation or inactivation of mutT genes, which plays a crucial role for the removal of oxidized guanines and in turn preventing errors during replication or transcription [36]. Non-adherence to the drug due to its long-term usage or underdosage or counterfeit drugs etc., can also predispose the bacteria to develop mutation(s) [37]. These mutation combinations could also be held accountable for the increase in MDR cases in the study area.

Mutations found in the rpoB gene can result in different levels of RIF resistance (low, moderate, high) depending on the position and the amino acid change. This is attributed to a consequence of receptor-ligand interaction changes such as steric hinderance, electrostatic repulsion, loss of hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interaction [38]. Mutations like H526D, H526Y and S531L (corresponding to probes D and E) are associated with high level of drug resistance, while L511P, D516Y, D516V (corresponding to probes A and B) and H526L, H526N, L533P (corresponding to probes D and E) favours moderate and low-level resistance respectively. In addition, L511P, D516Y, H526L, H526S, H526N, H526C and L533P amino acid changes were reported to be responsible for disputed rpoB mutations (genotypic resistant, phenotypic sensitive) which could be associated with low-level rifampicin resistance leading to poorer treatment outcomes and disease severity using standard-dosing rifampicin-based regimens [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]. This highlights the importance of sequencing to locate the exact amino-acid change within a specific probe region as probe mutations alone detected in Xpert MTB/RIF is not sufficient to determine the nature of drug resistance.

Among the 460 patients tested, this study also reports a “very low” bacillary load in 98/460 (21 %) cases. Ngabonziza et al. reported that having a “very low” bacillary load on Xpert/MTB RIF test was significantly correlated with false RIF resistance where they found that on repeated Xpert MTB/RIF testing, 54/63 (86 %) of patients with a “very low” bacillary load were falsely diagnosed as RIF resistance and further proved by sequencing [44]. The RIF resistant cases with “very low” bacillary load in this study were not re-tested with Xpert MTB/RIF. This calls for the need to re-test Xpert MTB/RIF in instances where RIF resistance arises with a “very low” bacillary load. In this study, due to the unavailability of other method of comparison such as culture (gold standard) or rpoB sanger sequencing method, the RIF false positivity rate could not be determined and hence it is difficult to elucidate the implications of this finding.

In this study, the proportion of extrapulmonary TB was more among females aged 25–34 years which is in concordance with a study from China where younger female patients are more likely to have extrapulmonary TB [45]. The predilection of extrapulmonary TB for women may be linked to the limited facilities for access to healthcare apart from the less prevalence of other risk factors such as habit of smoking. Previous studies have reported the increased risk of mortality with smoking in men but not in women [46]. In general, smoking is less common in women and hence they may be relatively protected from the hazardous pulmonary effect of smoking. This may be one of the factors for the differences in distribution [47]. This suggests that female gender and younger age could be an independent risk factor for TB especially in a high burden area. Bangladesh had reported the geographical distribution of RR-TB within their country [30]. Similarly, within Aizawl District, Aizawl North –III (11.9 %) had the highest proportion of RR-TB followed by Aizawl South –II (7.4 %) and Aizawl East –II (7.2 %) which warrants further investigation of the affected areas. The location of the residential areas might also prove useful for future epidemiological survey as well as for understanding the transmission pattern and severity of the disease.

5. Conclusion

In Mizoram where TB diagnostic infrastructures are limited, this retrospective study being the first molecular data on M. tuberculosis from the state provides genetic pattern of drug resistance accountable for RR over the past years, which will help local clinicians in the initiation of correct treatment. Unlike previous reports, the pattern of mutations observed in the 81 bp RRDR region of M. tuberculosis isolates were in codon 507–511 (probe A). Majority of the RR-TB were found in 25–34 years age group. Also, our findings provide a baseline data on the magnitude of RR-TB within the state and identification of the residential areas can help local health authorities in planning surveillance programs to control the spread of RR-TB.

6. Limitations

Our study has several limitations, being a retrospective study, it lacks relevant information such as previous history of TB treatment which could result in multiple probes mutation, HIV, diabetes and BCG vaccination status. In addition, rpoB gene sequencing could have established the specific rpoB mutation. As there is no scientific evidence yet, for the association of probe mutations with pulmonary or extrapulmonary sites, it is a very important objective to be considered for future studies by researchers.

7. Ethical clearance

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Mizoram (B.12018/1/13-CH (A)/IEC/63). All the participants had provided a written consent at the time of testing the samples.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants of this study and to the laboratory technologists Mr. K. Lalrinsanga, Ms. Jennifer Lalrammawii, Mr. Lalramnunsiama and Mr. Lalhmangaihsanga who performed the Xpert MTB/RIF assay. We would also like to extend our gratitude to the District TB Center (DTC) staff of Mizoram as well as Microbiology Department of Synod Hospital, Durtlang for their kind cooperation.

Funding

This study was funded by Department of Biotechnology (DBT), New Delhi under MDR -TB NER Project (BT/PR23092/NER/ 95/ 589/2017).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Christine Vanlalbiakdiki Sailo: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. Ralte Lalremruata: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Zothan Sanga: Writing – review & editing. Vanlal Fela: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Febiola Kharkongor: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Zothankhuma Chhakchhuak: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Lily Chhakchhuak: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Lalnun Nemi: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. John Zothanzama: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Nachimuthu Senthil Kumar: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jctube.2022.100342.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis report 2013. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/91355.

- 2.Drobniewski F., Wilson S. The rapid diagnosis of isoniazid and rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis—a molecular story. J Med Microbiol. 2018;47:189–196. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-3-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mani C., Selvakumar N., Narayanan S., Narayanan P.R. Mutations in the rpoB gene of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from India. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(8):2987–2990. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.8.2987-2990.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 5.Global tuberculosis report 2018. World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY- NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274453.

- 6.Helb Danica, Jones Martin, Story Elizabeth, Boehme Catharina, Wallace Ellen, Ho Ken, et al. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampin resistance by use of on-demand, near-patient technology. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(1):229–237. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01463-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaur R., Jindal N., Arora S., Kataria S. Epidemiology of rifampicin resistant tuberculosis and common mutations in rpoB Gene of mycobacterium tuberculosis: a retrospective study from six districts of Punjab (India) Using Xpert MTB/RIF Assay. J Lab Phys. 2016;8(2):96–100. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.180789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy R., Alvarez-Uria G. Molecular epidemiology of rifampicin resistance in mycobacterium tuberculosis using the GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay from a rural setting in India. J Pathog. 2017;2017:6738095. doi: 10.1155/2017/6738095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andre E., Goeminne L., Cabibbe A., Beckert P., Kabamba Mukadi B., Mathys V., et al. Consensus numbering system for the rifampicin resistance-associated rpoB gene mutations in pathogenic mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(3):167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehme Catharina C, Nicol Mark P, Nabeta Pamela, Michael Joy S, Gotuzzo Eduardo, Tahirli Rasim, et al. Feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, and effectiveness of decentralised use of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for diagnosis of tuberculosis and multidrug resistance: a multicentre implementation study. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1495–1505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60438-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ocheretina Oksana, Byrt Erin, Mabou Marie-Marcelle, Royal-Mardi Gertrude, Merveille Yves-Mary, Rouzier Vanessa, et al. False-positive rifampin resistant results with Xpert MTB/RIF version 4 assay in clinical samples with a low bacterial load. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;85(1):53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global tuberculosis report 2014. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/137094.

- 13.India TB Report › WriteReadData › India TB 2020.

- 14.Desikan P., Chauhan D.S., Sharma P., Panwalkar N., Yadav P., Ohri B.S. Clonal diversity and drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from extra-pulmonary samples in central India–a pilot study. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2014;32(4):434–437. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.142255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singhal R., Myneedu V.P., Arora J., Singh N., Bhalla M., Verma A., et al. Early detection of multi-drug resistance and common mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Delhi using GenoType MTBDRplus assay. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33(Suppl):46–52. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.150879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain A., Diwakar P., Singh U. Declining trend of resistance to first-line anti-tubercular drugs in clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a tertiary care North Indian hospital after implementation of revised national tuberculosis control programme. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2014;32:430–433. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.142257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asgedom S.W., Teweldemedhin M., Gebreyesus H. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and associated factors in ethiopia: a systematic review. J Pathog. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2018/7104921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu M., Han G., Takiff H.E., Wang J., Ma J., Zhang M., et al. Times series analysis of age-specific tuberculosis at a rapid developing region in China, 2011–2016. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8727. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27024-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alemu Ayinalem, Tadesse Mengistu, Seid Getachew, Mollalign Helina, Eshetu Kirubel, Sinshaw Waganeh, et al. Does Xpert® MTB/RIF assay give rifampicin resistance results without identified mutation? Review of cases from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adhikari S., Saud B., Sunar S., Ghimire S., Yadav B.P. Status of rpoB gene mutation associated with rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated in a rural setting in Nepal. Access Microbiol. 2021;3(3) doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma P., Singh R. GeneXpert MTB/RIF based detection of rifampicin resistance and common mutations in rpoB Gene of mycobacterium tuberculosis in tribal population of district Anuppur, Madhya Pradesh, India. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2020;14:LM01-LM03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2020/45362.14035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Billington O.J., McHugh T.D., Gillespie S.H. Physiological cost of rifampin resistance induced in vitro in mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(8):1866–1869. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanade S., Nataraj G., Mehta P., Shah D. Pattern of missing probes in rifampicin resistant TB by Xpert MTB/RIF assay at a tertiary care centre in Mumbai. Indian J Tuberc. 2019;66(1):139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ochang Ernest A., Udoh Ubong A., Emanghe Ubleni E., Tiku Gerald O., Offor Jonah B., Odo Micheal, et al. Evaluation of rifampicin resistance and 81-bp rifampicin resistant determinant region of rpoB gene mutations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis detected with XpertMTB/Rif in Cross River State. Nigeria Int J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5:S145–S146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ullah I., Shah A.A., Basit A., Ali M., Khan A., Ullah U., et al. Rifampicin resistance mutations in the 81 bp RRDR of rpoB gene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates using Xpert MTB/RIF in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:413. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1745-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman Arfatur, Sahrin Mahfuza, Afrin Sadia, Earley Keith, Ahmed Shahriar, Mazidur Rahman S.M., et al. Comparison of Xpert MTB/RIF assay and GenoType MTBDRplus DNA probes for detection of mutations associated with rifampicin resistance in mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2016;11(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metcalfe J.Z., Makumbirofa S., Makamure B., Sandy C., Bara W., Mason P., et al. Xpert(®) MTB/RIF detection of rifampin resistance and time to treatment initiation in Harare. Zimbabwe Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;20(7):882–889. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar V., Bala M., Kanga A., Gautam N. Identification of missing probes in rpoB gene in rifampicin resistant PTB and EPTB Cases using xpert MTB/RIF assay in sirmaur. Himachal Pradesh J Assoc Physicians India. 2020;68(11):33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mboowa G., Namaganda C., Ssengooba W. Rifampicin resistance mutations in the 81 bp RRDR of rpoB gene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates using Xpert® MTB/RIF in Kampala, Uganda: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:481. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uddin M.K.M., Rahman A., Ather M.F., Ahmed T., Rahman S.M.M., Ahmed S., et al. Distribution and frequency of rpoB mutations detected by Xpert MTB/RIF assay among beijing and non-beijing rifampicin resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Bangladesh. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:789–797. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S240408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yue J., Shi W., Xie J., Li Y., Zeng E., Wang H. Mutations in the rpoB gene of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from China. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(5):2209–2212. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.2209-2212.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rufai Syed Beenish, Kumar Parveen, Singh Amit, Prajapati Suneel, Balooni Veena, Singh Sarman, et al. Comparison of Xpert MTB/RIF with line probe assay for detection of rifampin-monoresistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(6):1846–1852. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03005-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.N’guessan Kouassi K., Riccardo Alagna, Dutoziet Christian C., André Guei, Férilaha Coulibaly, Hortense Seck-Angu, et al. Genotyping of mutations detected with GeneXpert. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5(2):142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sailo Christine Vanlalbiakdiki, Zami Zothan, Lalremruata Ralte, Sanga Zothan, Fela Vanlal, Kharkongor Febiola, et al. MGIT sensitivity testing and genotyping of drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Mizoram, Northeast India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2022;40(3):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmmb.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkatesh J., Kumar P., Krishna P.S., Manjunath R., Varshney U. Importance of uracil DNA glycosylase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Mycobacterium smegmatis, G+C-rich bacteria, in mutation prevention, tolerance to acidified nitrite, and endurance in mouse macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(27):24350–24358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mokrousov I. Multiple rpoB mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and second-order selection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1337–1338. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchison D.A. How drug resistance emerges as a result of poor compliance during short course chemotherapy for tuberculosis. Int J Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;2(1):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Ma-chao, Lu Jie, Lu Yao, Xiao Tong-yang, Liu Hai-can, Lin Shi-qiang, et al. rpoB Mutations and effects on rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:4119–4128. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S333433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Deun A., Barrera L., Bastian I., Fattorini L., Hoffmann H., Kam K.M., et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with highly discordant rifampin susceptibility test results. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(11):3501–3506. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01209-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rigouts Leen, Gumusboga Mourad, de Rijk Willem Bram, Nduwamahoro Elie, Uwizeye Cécile, de Jong Bouke, et al. Rifampin resistance missed in automated liquid culture system for Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with specific rpoB mutations. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(8):2641–2645. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02741-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Deun Armand, Aung Kya J.M., Bola Valentin, Lebeke Rossin, Hossain Mohamed Anwar, de Rijk Willem Bram, et al. Rifampin drug resistance tests for tuberculosis: challenging the gold standard. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(8):2633–2640. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00553-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho J., Jelfs P., Sintchencko V. Phenotypically occult multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: dilemmas in diagnosis and treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(12):2915–2920. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jamieson F.B., Guthrie J.L., Neemuchwala A., Lastovetska O., Melano R.G., Mehaffy C., et al. Profiling of rpoB mutations and MICs for rifampin and rifabutin in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(6):2157–2162. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00691-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ngabonziza J.C.S., Decroo T., Migambi P., Habimana Y.M., Deun A.V., Meehan C.J., et al. Prevalence and drivers of false-positive rifampicin- resistant Xpert MTB/RIF results: a prospective observational study in Rwanda. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e74–e83. doi: 10.1016/s2666-5247(20)30007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pang Yu, An Jun, Shu Wei, Huo Fengmin, Chu Naihui, Gao Mengqiu, et al. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis among Inpatients, China, 2008–2017. Emerging Infect Dis. 2019;25(3):457–464. doi: 10.3201/eid2503.180572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lam T.H. Mortality and smoking in Hong Kong: case-control study of all adult deaths in 1998. BMJ. 2001;323(7309):361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7309.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Musellim B., Erturan S., Sonmez D.E., Ongen G. Comparison of extra-pulmonary and pulmonary tuberculosis cases: factors influencing the site of reactivation. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(11):1220–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.