Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed and widened racialized health disparities, underscoring the impact of structural inequities and racial discrimination on COVID-19 vaccination uptake. A sizable proportion of Black American men report that they either do not plan to or are unsure about becoming vaccinated against COVID-19. The present study investigated hypotheses regarding the mechanisms by which experiences of racial discrimination are associated with Black American men’s COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling with 4 waves of data from 242 Black American men (aged ~ 27) living in resource-poor communities in the rural South. Study findings revealed that racial discrimination was indirectly associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy via increased endorsement of COVID-19 conspiratorial beliefs. Findings also demonstrated that increased levels of ethnic identity strengthen the association between experiences of racial discrimination and COVID-19 conspiratorial beliefs. In contrast, increased levels of social support weakened the association between cumulative experiences of racial discrimination and COVID conspiratorial beliefs. Taken together, these results suggest that racial discrimination may promote conspiratorial beliefs which undermine Black American men’s willingness to be vaccinated. Future interventions aimed towards promoting vaccine uptake among Black American men may benefit from the inclusion of targeted efforts to rebuild cultural trust and increase social support.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40615-022-01471-8.

Keywords: Black American, Vaccine hesitancy, COVID, Racial discrimination, Ethnic identity, COVID conspiratorial beliefs

Nationally, Black Americans were consistently more likely to be diagnosed, hospitalized, and die from COVID than all other racial/ethnic groups [21, 56, 76]. Prior research indicates that Black American men are particularly vulnerable to contracting COVID [22, 88]. Studies have linked this increased vulnerability to Black American men’s propensity to live in multigenerational homes and with extended kin [25], be underinsured or uninsured [20, 89], and be employed in positions that offer limited flexibility to initiate and maintain COVID-related protective behavior [45, 54]. Despite these risks, recent data suggest that Black American men are among the least likely to be vaccinated against COVID [2, 46].

Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated high levels of efficacy regarding the COVID vaccine and have showed promise in controlling the spread of the virus and reducing the severity of symptoms following infection [6, 43, 64]. However, distribution is one factor that affects vaccine effectiveness [62, 63]. Black Americans report higher rates of vaccine hesitancy, in general, and COVID vaccine hesitancy, in particular, compared to all other racial/ethnic groups in the USA [42, 60]. Vaccine hesitancy can be defined as a delay in acceptance, or downright refusal, of vaccines despite the availability of vaccine services [60]. The term covers outright refusals to vaccinate, delaying vaccines, and accepting vaccines but remaining uncertain about their use, or using certain vaccines but not others [60]. Extant studies link vaccine hesitancy to low levels of perceived proximity to COVID exposure [59], perceived severity of COVID acquisition [86], perceived impact of contracting COVID [66, 82], socioeconomic status [40], and educational attainment [81, 90].

Emerging theory and research suggest that experiences of racial discrimination may influence Black Americans’ vaccination uptake [10, 32]. Racial discrimination is a multidimensional construct with mundane experiences (i.e., everyday experiences of unfair treatment because of one’s race) being distinguishable from major acute experiences (i.e., major experiences of prejudice in domains such as employment, education, housing, and interactions with the police; [83]. Several studies have documented the impact of historical events, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [16], on Black American men’s trust in health systems as well as trust in government or other institutional influences [14, 27, 44]. These studies indicate that experiences of discrimination may undermine Black American men’s trust in systems of authority that are meant to serve and protect them by demonstrating that (a) their well-being is not considered by policymakers and healthcare professions when making decisions and (b) their communities are the target of unjust medical practices and regulations [16, 27, 44]. Much of the empirical literature in this area use single time-point assessments of discrimination (e.g., [68, 84]. This represents a notable limitation as prior research indicates that the effects of racial discrimination are cumulative [1, 50]. This gap is significant as it may limit the efficacy of evidence-based culturally responsive vaccine promotion interventions. We thus investigate the link between racial discrimination young men reported experiencing over the past 3 years and their intentions to be vaccinated for COVID-19.

COVID Conspiracy Beliefs

Research links COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs to racial discrimination [5, 73] and to COVID vaccine hesitancy [26, 48]. Conspiracy beliefs are attempts to explain the ultimate causes of events with claims of secret plots by powerful actors [48]. Concerning COVID, conspiracy beliefs may include ideas such as the origin and spread of COVID-19 being the results of purposeful acts, or vaccines existing to serve some nefarious purpose [26]. A recent review of the antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs suggests that the perceived lack of control borne out of experiences of contextual disenfranchisement (e.g., racial discrimination) undermine individuals’ trust in the government and other agencies of influence and increase men’s vulnerability to believing conspiracy theories in order to make sense of and better cope with stressful events [53, 75, 80]. We posit that chronic exposure to discrimination may promote conspiracy beliefs by undermining Black American men’s belief in the reliability and positive motives of societal institutions that promote public health and well-being. Our hypothesis is supported by prior research which indicates that experiences of racial discrimination may be associated with increased endorsement of COVID conspiratorial beliefs through establishment of an interrelated set of attitudes and cognitions of mistrust towards government and other agencies of influence [9, 24, 52]. Research also documents a positive association between COVID conspiratorial beliefs and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [5, 78]. We know of no study to date, however, that has investigated COVID conspiracy beliefs as a mediator linking experiences of racial discrimination to rural Black American men’s COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Moderators of the Effects of Racial Discrimination

Prior research indicates that ethnic identity and social support are associated with individual differences in the consequences of racial discrimination on Black American men’s health-decision-making [28, 72, 79]. Regarding ethnic identity, evidence suggests ethnic identity moderates the effects of racial discrimination in that individuals who feel more positively about being a member of the Black American community are more aware of and sensitive to discriminatory events [69, 70]. For example, individuals with higher levels of ethnic identity were more likely to report experiencing racial discrimination and report higher levels of race-related stress [72]. Greene et al. [28] found that Black Americans who reported higher levels of ethnic identity reported increased perceived discrimination which were then associated with higher levels of psychological distress than those who reported lower levels of ethnic identity. Taken together, these data suggest that high levels of ethnic identity may amplify the influence of racial discrimination on Black American men’s COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Consequently, we hypothesize that high levels of ethnic identity will strengthen the relations between Black American men’s experiences of racial discrimination and (a) conspiracy beliefs, and (b) COVID vaccine hesitancy.

In contrast to the potential excerabatory effects of ethnic identity, social support is expected to attenuate the detrimental effects of racial discrimination. Prior research indicates that Black American men frequently utilize social support to cope with racial discrimination [19, 67]. For example, Swim and colleagues (2003) found that Black American men reported often talking to friends and family members about a racist discriminatory event shortly after it occurred. Furthermore, Utsey and colleagues (2006) demonstrated that social support buffered the negative effects of racial discrimination, enabling individuals with high levels of support to experience less strain and cope more successfully [79]. In accordance with prior research, we hypothesize that high levels of social support would weaken the relationship between Black American men’s experiences of racial discrimination and COVID vaccine hesitancy, and COVID vaccine hesitancy, respectively.

The Current Study

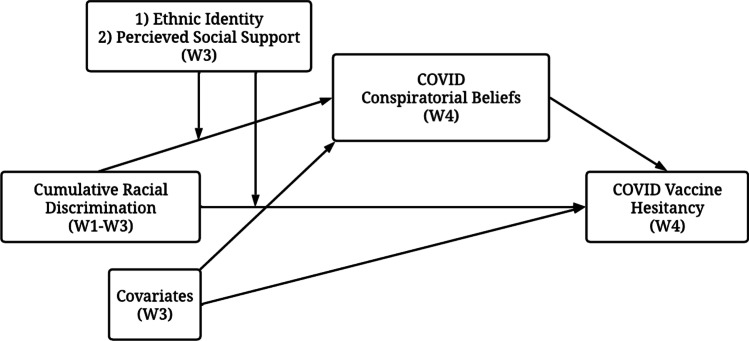

Informed by prior investigations of Black American’s health care decision-making [29, 36, 41, 49, 85], we conducted a longitudinal study examining hypotheses regarding the mechanisms by which experiences of racial discrimination are associated with Black American men’s COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (see Fig. 1). We hypothesized that exposure to racial discrimination would predict increases COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy indirectly via COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs. Second, we hypothesized that increase in levels of ethnic identity would exacerbate the influence of racial discrimination on COVID conspiratorial beliefs and on COVID vaccine hesitancy. Last, we hypothesized that increased levels of perceived social support to attenuate the influence of racial discrimination on COVID conspiratorial beliefs and on COVID vaccine hesitancy.

Fig. 1.

Summarized hypotheses

Methods

Participants

The current analyses used data from men participating in a longitudinal study of rural Black American men’s health and well-being during young adulthood. Participants were recruited from 11 contiguous counties in rural Georgia, which were representative of areas of rural poverty in the southeastern USA [57]. Baseline eligibility criteria included (a) self-identification as African American or Black, (b) residence in a targeted county, and (c) age 19 to 22 years. The baseline assessment included 504 men (age ~ 20 years old). Assessment of racial discrimination occurred beginning with the next wave and comprises wave 1 of this analysis. At wave 1, 422 men participated (age ~ 22 years old). Approximately 1 year later, 408 men participated in wave 2 (age ~ 23 years old). Wave 3 occurred 2.5 years after the completion of wave 2; men were ~ 27 years old. The COVID-19 pandemic occurred after 242 completed wave 3 data collection, which encompassed the analytic sample used in this study. We followed up with men who had participated in wave 3 Pre-COVID approximately soliciting data on their conspiracy beliefs and vaccine hesitancy. All 242 participants who participated in wave 3 of data collection were invited to participate in wave 4; 164 participants responded. Among the participants at wave 4, 84.3% were unmarried, 38.8% lived with a romantic partner while 24.8% lived with immediate family members. Most had earned at least a high school diploma (90.9%) and were employed (73.1%).

Recruitment

Participants were recruited using respondent-driven sampling (RDS; [31]. Community liaisons recruited 45 “seed” participants from targeted counties to complete a baseline survey. Seed participants were members of the liaisons’ personal networks or responded to advertisements and outreach efforts in the local community. Participants were then asked to identify three other Black men in their community who qualified for participation in the study. The RDS protocols and weighing system are designed to attenuate the influence of biases common in chain-referral samples and to improve the approximation of a random sample of the target population [31]. Analyses of network data related to demographics, substance use, and other risky behavior at baseline [35] indicated that the sample evinced negligible levels of common biases observed in chain-referral samples arising from the characteristics of the initial seed participants, individual participants’ recruitment efficacy, and differences in the sizes of participants’ networks. We thus used raw data in the present analysis.

Procedures

Participants completed pre-COVID surveys (waves 1, 2, and 3) in their homes or at a convenient, private location in the community. Surveys were administered on a laptop computer using an audio computer-assisted self-interview protocol, which allowed participants to navigate the survey with the help of voice and video enhancements, eliminating literacy concerns. The post-COVID survey (wave 4) was completed by participants online using their own devices via the Qualtrics platform. Participants received $100 for completing the survey at each wave. Participants provided written informed consent; all study protocols were approved by the University’s Human Subjects Review Board. The study operated under a federal certificate of confidentiality issued by the US National Institute of Health.

Measures

Vaccine Hesitancy

At W4, participants reported their delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services using a 15-item measure developed by Quinn et al. [61]. This measure had two subscales: general vaccine hesitancy (6 items) and COVID vaccine hesitancy (7 items). Men responded to items using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (completely) to 3 (not at all), whereby higher scores indicated increased vaccine hesitancy. Examples of items included “how much do you trust the COVID-19 vaccine? (Reverse coded)” and “is the COVID-19 vaccine necessary?” Cronbach’s α for the measure of general vaccine hesitancy was 0.92; for the measure of COVID vaccine hesitancy, it was 0.93.

Racial Discrimination

In accordance with prior research, we included two indicators of racial discrimination—one for mundane experiences and one for acute experiences from W1 to W2. Mundane racial discrimination was assessed using a 9-item scale [17]. Men’s responses to the items on a scale ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (frequently) regarding their experiences of chronic discrimination in the last 6 months. Examples of items included “have you been ignored, overlooked, or not given service because of your race?” and “have you been called a name or harassed because of your race?” Items were summed to create total mundane discrimination score where higher scores were indicative of more mundane experiences of racial discrimination. Cronbach’s α were W1 = 0.86, W2 = 0.87, and W3 = 0.90. Acute experiences of racial discrimination were assessed using a 10-item measure of major experiences of racial discrimination developed by Williams et al. [83]. Men responded to items with either 0 (no) or 1 (yes) regarding their experiences of major discrimination in the last 6 months. Items included “fired from a job because you are Black” and “denied a bank loan because you are Black.” Cronbach’s α were W1 = 0.80, W2 = 0.85, and W3 = 0.81. Scores at each time point were summed to create a cumulative racial discrimination index score.

COVID Conspiracy Beliefs

At W4, participants reported their level of agreement to 7 statements about the COVID pandemic that reflected a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, to explain an event or situation. The measure was developed sequentially. First, we compiled a list of potential items by conducting a review of the most popular COVID-related conspiracy theories circulating within mainstream and social media in January 2021. Next, we shared this list this with a review panel comprised of (a) experienced researchers with expertise in the study of Black Americans and conspiracy theories, (b) community partners, and (c) Black American men unrelated to the study. This review panel suggested several revisions and refinements that resulted in the final measure that was included in this study (see Appendix A). Men responded to the items on a scale from 0 (definitely not true) to 4 (definitely true). Examples of items included “COVID was created by powerful people to be a bioweapon,” and “Bill Gates developed COVID for population control.” Before testing our hypotheses, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis, testing the unidimensionality of the 7-item scale. The single factor model fit the data as follows: χ2(10) = 9.69, p = 0.468; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.000 [0.000; 0.083], comparative fit index (CFI) = 1.00, and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) = 0.02. All factor loadings were significant, exceeded 0.67, and were in the predicted direction indicating unidimensionality in the measure. Consequently, items were summed to create a total COVID conspiratorial beliefs score. Cronbach’s α was 0.91.

Ethnic Identity

At W3, ethnic identity was assessed using an 11-item measure adapted from the Centrality subscale of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity [71] and the Stereotype subscale of the Multi-Construct African American Identity Questionnaire [74]. This adapted measure has been used previously [18]. Participants were given a list of states and asked how strong they disagree or agree with that statement. Example items include “I feel good about Black people” and “I feel that the Black community has made valuable contributions to this society.” The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Items were summed to create total ethnic identity score where higher scores were indicative of higher levels of ethnic identity. Cronbach’s α for this measure was 0.80.

Social Support

At W3, social support was assessed using the 10-item version of the Social Provisions Scale developed by Cutrona and Russell [23]. Participants responded to the items on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Example items include “I feel that I do not have close personal relationships with other people,” and “Other people do not view me as competent.” Items were recoded and summed to create a total perceived social support score. Cronbach's α for this measure was 0.91.

Covariates

COVID Susceptibility Worry

At W4, participants reported their level of COVID-related susceptibility worry using a 3-item measure. These items included (1) How worried are you about getting COVID-19? (2) How worried are you that if you got COVID-19 you would get very sick? (3) How worried are you that if you got COVID-19 you would sicken a loved one? Men responded to the items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not worried) to 4 (very worried). Items were summed to create a total COVID worry score. Cronbach’s α for this measure was 0.72.

COVID-Related Stress

At W4, participants reported their level of COVID-related stress using a 3-item measure. These items included (1) how much has the COVID-19 outbreak impacted your daily life in the past month, (2) how has your overall level of stress due to the COVID-19 outbreak, and (3) to what degree has changes related to the COVID-19 outbreak created financial problems for you. Men responded to the items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (no impact/stress/problems) to 4 (extreme impact/stress/problems). Items were summed to create a total COVID-related stress score. Cronbach’s α for this measure was 0.87.

COVID Exposure Proximity

At W4, participants reported their exposure proximity COVID-19 via three items (0 = no; 1 = yes). These items included (1) whether men personally contracted COVID, (2) whether a member of participant’s friends or family contracted COVID, and (3) whether a friend or family member of participant’s died due to COVID. Items were summed to create a total COVID exposure proximity score.

Demographic Information

At W4, participants were asked to provide their highest level of education and employment status. Men reported their highest level of education using a single-item indicator with response options ranging from 1 (Grade 10 or below) to 6 (4-year college degree or more). Employment status was measured by a single dichotomous item (yes/no) asking whether participants were currently employed at a job where they receive a paycheck or were paid in cash.

Data Analysis

To investigate hypotheses regarding the mechanisms by which experiences of racial discrimination are associated with Black American men’s COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, we first tested an indirect effects model examining the extent to which COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs mediated the association between racial discrimination and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Next, we investigated the degree to which ethnic identity influenced the association between racial discrimination on COVID conspiratorial beliefs and on COVID vaccine hesitancy with the inclusion of an interaction term (racial discrimination x ethnic identity). The third and final model examined the degree to which perceived social support influenced the association between racial discrimination on COVID conspiratorial beliefs and on COVID vaccine hesitancy by replacing the interaction term included in the second model with a new interaction term (racial discrimination × perceived social support).

All analyses were conducted using data from 242 men who participated in wave 3 data collection with Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Retention status across wave was not associated with racial discrimination or demographic characteristics. Little’s Missing Completely at Random test, χ2(4) = 3.79, p = 0.46, suggested that missing values were missing completely at random and were unrelated to the study variables [38]. Accordingly, missing data were managed with full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML; [39]. FIML tests hypotheses with all available data; no cases were dropped due to missing data [7, 39]. p values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant for the purposes of this study. The significance of indirect effects was evaluated with bootstrapping analyses with 5000 bootstrapping resamples to produce 95% confidence intervals (CIs; [13]. These intervals consider possible nonsymmetry in the distribution of estimates, which can bias p values [30]; we thus used the 95% CIs when determining the significance of indirect effects. This study used CFI values greater than or equal to 0.90, RMSEA values less than or equal to 0.08, and SRMR values less than or equal to 0.08 as being indicative of well-fitting models [8, 34]. Measures with Cronbach’s alpha levels of 0.70 or higher were deemed to have acceptable internal consistency for the purposes of this study. The chi-square test of model fit (χ2) was also reported for completeness.

All covariates were included in all models. In addition to the direct paths linking the variables, covariation between all predictor variables was permitted. Additionally, residuals of the mediators and dependent variables were correlated to indicate shared unexplained variance. Moderating effects were evaluated with the creation of two interaction terms: (1) racial discrimination × ethnic identity, and (2) racial discrimination × perceived social support. The predictor and moderator variables were first standardized, and then the product terms were calculated by multiplying these standardized variables to facilitate the interpretation of slopes [4]. Simple slope analysis and the Johnson-Neyman method were conducted to verify significant interactions. The Johnson-Neyman method is a procedure for establishing regions of insignificance associated with a test of the difference between two variables at any specific point on the X continuum [33]. In the simple slope analysis, participants were divided into high and low level of groups based on the mean ± 1 standard deviation of each significant moderator. Unstandardized regression parameters for each model provided in Appendix B.

Results

Bivariate Analysis

The means, standard deviations, and correlations for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Racial discrimination was positively correlated with increased levels of COVID conspiracy beliefs (r = 0.22, p = 0.01), COVID exposure fear (r = 0.18, p = 0.05), COVID stress (r = 0.32, p = 0.01), and COVID trauma (r = 0.20, p = 0.05). Racial discrimination was negatively correlated with increased levels of ethnic identity (r = − 0.15, p = 0.05), and perceived social support (r = − 0.31, p = 0.01). COVID vaccine hesitancy was positively correlated with increased levels of general vaccine hesitancy (r = 0.84, p = 0.01), and COVID conspiracy beliefs (r = 0.28, p = 0.01). Conversely, COVID vaccine hesitancy was negatively correlated with COVID exposure fear (r = − 0.33, p = 0.01), educational attainment (r = − 0.28, p = 0.01), and perceived social support (r = − 0.26, p = 0.01).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and two-tailed bivariate correlations among study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | COVID vaccine hesitancy | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2 | General vaccine hesitancy | .84** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3 | Racial discrimination | − .03 | − .01 | 1 | ||||||||

| 4 | COVID conspiracy beliefs | .28** | .22** | .22** | 1 | |||||||

| 5 | COVID exposure fear | − .33** | − .34** | .18* | .11 | 1 | ||||||

| 6 | COVID stress | − .10 | − .08 | .32** | .21** | .46** | 1 | |||||

| 7 | COVID trauma | − .18* | − .10 | .20* | .07 | .22** | .32** | 1 | ||||

| 8 | Educational attainment | − .28** | − .32** | − .01 | − .14 | .07 | .17* | .25** | 1 | |||

| 9 | Employment status | .01 | − .05 | − .01 | − .07 | − .03 | − .07 | .16* | .23** | 1 | ||

| 10 | Ethnic identity | − .14 | − .08 | − .15* | .00 | − .02 | .00 | .14 | .09 | .05 | 1 | |

| 11 | Perceived social support | − .26** | − .20* | − .31** | − .26** | .07 | − .04 | .08 | .21** | .08 | .29** | 1 |

| M | 14.35 | 11.52 | 24.93 | 19.08 | 5.46 | 8.66 | .77 | 5.53 | .79 | 40.68 | 30.13 | |

| SD | 5.79 | 5.17 | 16.89 | 7.13 | 2.32 | 5.24 | .89 | 1.98 | .41 | 3.96 | 6.48 | |

| Range | 0–21 | 0–18 | 0–74 | 7–35 | 3–12 | 1–21 | 0–3 | 1–9 | 0–1 | 25–44 | 10–40 |

*p < .05; **p < .01

Indirect Effects Model

Figure 2 presents the standardized results of our indirect effects model. The model fit the data as follows: χ2(3) = 7.104, p = 0.069; RMSEA = 0.075 [0.000, 0.148]; CFI = 0.981; and SRMR = 0.031. Results indicated that cumulative racial discrimination was directly associated with increased COVID conspiratorial beliefs (B = 0.101, p < 0.01), but not directly associated with Black American men’s COVID vaccine hesitancy (B = − 0.004, p = 0.762). COVID conspiratorial beliefs was directly associated with increased COVID vaccine hesitancy (B = 0.103, p < 0.01). Significant indirect effects were detected whereby racial discrimination was associated with COVID vaccine hesitancy indirectly via COVID conspiratorial beliefs (Bind = 0.010; 95% CI = 0.003, 0.027).

Fig. 2.

Standardized results of mediation model linking cumulative racial discrimination to COVID vaccine hesitancy among Black American men

Exacerbating Effects of Ethnic Identity

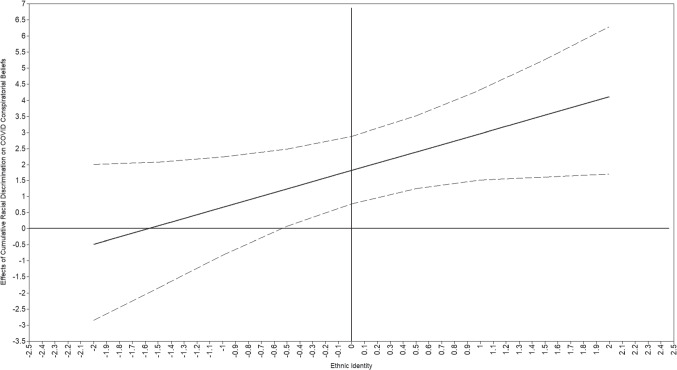

A second model examined whether ethnic identity moderated the associations of cumulative racial discrimination on COVID conspiratorial beliefs and on COVID vaccine hesitancy. The model fit the data as follows: χ2(11) = 28.987, p = 0.002; RMSEA = 0.08 [0.046, 0.119], CFI = 0.919, and SRMR = 0.046. Ethnic identity was not directed associated with COVID conspiracy beliefs (B = 0.149, p = 0.822) or COVID vaccine hesitancy (B = − 0.356, p = 0.135). The interaction of racial discrimination and ethnic identity on COVID vaccine hesitancy was not significant (B = − 0.191, p = 0.308). However, the interaction of racial discrimination and ethnic identity on COVID conspiracy beliefs was significant (B = 1.149, p < 0.05). Simple slope analysis indicated an increased association between racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs at high levels of ethnic identity (B = 2.389, p < 0.001). However, data failed to support a corresponding association at low levels of ethnic identity (B = 1.240, p < 0.05; see Fig. 3). Review of the Johnson-Neyman plot (Fig. 4) documented significant moderation wherein the association between racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs was significant at − 0.3 standard deviations below the average level of ethnic identity (− 0.3 SD = 39.494; see Fig. 4). This interaction evidenced significant conditional indirect effects (conditional Bind = 0.130; 95% CI = 0.019, 0.360).

Fig. 3.

Interaction of ethnic identity and racial discrimination on COVID conspiracy beliefs

Fig. 4.

Johnson-Neyman plot for the interaction of ethnic identity and racial discrimination on COVID conspiracy beliefs. Note: Bold line represents the conditional effect of racial discrimination on COVID conspiracy beliefs with dashed lines identifying 95% confidence intervals of the effect

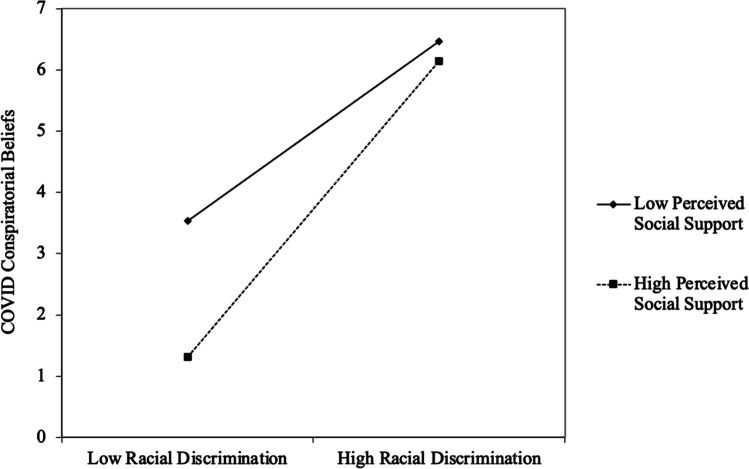

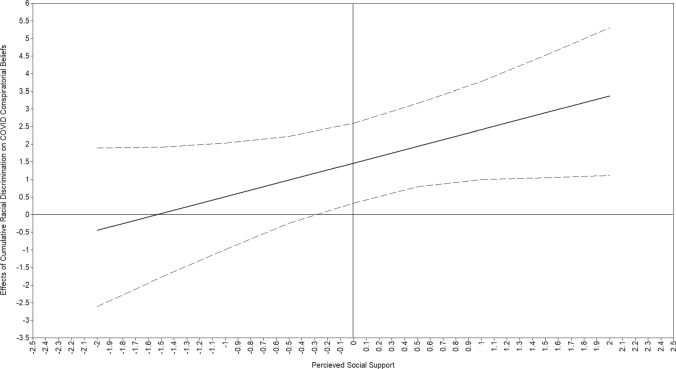

Buffering Effects of Perceived Social Support

A third model examined whether perceived social support moderated the direct and indirect associations between cumulative racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs, and COVID vaccine hesitancy, respectively. The model fit the data as follows: χ2(11) = 19.540, p = 0.0521; RMSEA = 0.057 [0.000, 0.097]; CFI = 0.963; and SRMR = 0.040. Perceived social support was directly associated with decreasing COVID conspiracy beliefs (B = − 1.274, p < 0.05) but was not directed associated with COVID vaccine hesitancy (B = − 0.457, p = 0.096). The interaction of racial discrimination and perceived social support on COVID vaccine hesitancy was not significant (B = − 0.343, p = 0.123). Perceived social support did, however, moderate the association between racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs (B = 0.955, p < 0.05). Simple slope analysis indicated a diminished association between racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs at high levels of perceived social support (B = 1.939, p < 0.001). However, data failed to support a corresponding association at low levels of ethnic identity (B = 0.984, p = 0.121; see Fig. 5). Review of a Johnson-Neyman plot indicated the association between racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs was significantly affected by perceived social support at values equal to or greater than − 0.1 standard deviation below the average level of perceived social support (− 0.1 SD = 29.384; see Fig. 6). This interaction evidenced significant conditional indirect effects (conditional Bind = 0.094; 95% CI = 0.013, 0.277).

Fig. 5.

Interaction of perceived social support and racial discrimination on COVID conspiracy beliefs

Fig. 6.

Johnson-Neyman plot for the interaction of perceived social support and racial discrimination on COVID conspiracy beliefs. Note: Bold line represents the conditional effect of racial discrimination on COVID conspiracy beliefs with dashed lines identifying 95% confidence intervals of the effect

Discussion

The present study is among the first to investigate the pathways linking cumulative experiences of racial discrimination to COVID vaccine hesitancy among Black American men. We advanced research in this area in two ways. First, we examined if COVID conspiracy beliefs mediated the association between cumulative racial discrimination and COVID vaccine hesitancy. We found that racial discrimination was indirectly associated with COVID vaccine hesitancy via the increased endorsement of COVID conspiracy beliefs. Second, we examined the degree to which ethnic identity and perceived social support moderated the effects of cumulative racial discrimination on COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Our findings also indicated that when men reported increased ethnic identity, the association between racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs was strengthened. In contrast, increased levels of perceived social support weakened the association between racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs.

The results of this study suggest that the endorsement of COVID conspiracy beliefs mediated the association between cumulative experiences of racial discrimination unrelated to healthcare and COVID vaccine hesitancy. These results are consistent with prior research which suggest that experiences of marginalization and disenfranchisement erode Black American men’s trust in the systems of authority associated with health care decision making [53, 80]. Our findings further indicate Black American men may adopt conspiracy beliefs to make sense of and better cope with discriminatory events. Experiences of racial discrimination may encourage Black American men to seek out narratives contrary to those being presented by the government or public health agencies to better understand their contemporary social contexts. This search for alternative narratives, coupled with historical atrocities such as the Tuskegee syphilis study, provide a compelling reason for Black Americans to believe that the US government or other agencies of influence are capable of conspiring to harm them. Regarding the COVID-19 vaccine, hesitancy and endorsement of conspiracy beliefs may be related to (a) healthcare professionals’ and stakeholders’ uncertainty concerning how to respond to the pandemic, and (b) the perceived disorganized COVID pandemic response of the government and other agencies by laypersons. This tension was compounded by a wider decline in trust of medical establishment, the politization of the healthcare system, and many state governors being at odds with the President, who in turn was at odds with his own pandemic advisory team, and the nation’s public health institutions regarding the dissemination of the vaccine [65, 87]. This confusion was further complicated by inconsistencies in governmental reporting related to the needed dosage of the vaccine to be effective, and vaccination side effects, thus undermining governmental believability and credibility [65, 87]. The results of this study, coupled with prior theoretical and empirical research, suggest that cumulative experiences of racial discrimination contributed to Black American men’s susceptibility to the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs, which were then related to increased COVID vaccine hesitancy.

Consistent with study hypotheses, ethnic identity strengthened the positive association between racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs. These findings are consistent with prior research that indicated that ethnic identity magnifies the association between racial discrimination and men’s endorsement of COVID conspiracy beliefs [3, 73]. In interpreting these findings, it is important not to construe ethnic identity as a problematic feature of an individual. In fact, ethnic identity is important to an individual’s self-image and is typically associated with positive outcomes such as better mental health and higher self-esteem [51]. As such, ethnic identity may have a diverging effect on health-related outcomes among Black American men whereby individuals who are exhibiting high levels of ethnic identity may experience good mental health, such as low levels of depression and anxiety, but are at elevated risk for adverse health outcomes, such as lower medication adherence. Further research is needed to better understand the paradoxical effects of ethnic identity on the associations between Black American men’s experiences of racial discrimination, conspiracy beliefs, and various health-related outcomes.

In the present study, social support weakened the association between cumulative experiences of racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs. In accordance with prior research, our findings suggest that perceived social support attenuates the effects of racial discrimination on Black American men’s trust in systems of influence [15, 55]. The attenuating effects of social support can be interpreted several ways. First, social support may reduce the downstream effects of discriminatory events by modulating individuals’ experiences of the resulting stress. Prior research indicates that individuals embedded within a socially supportive environment appraise racial stressors as less salient than those with weaker or more negative social support networks [55]. Another possible explanation for this finding may be that when Black Americans experience a discriminatory event, they cope with the stress of that event by turning to their social networks for support [58]. From this perspective, the psychosocial stress of experiencing racial discrimination does not carry forward to have long-lasting effects on men’s health decision-making. Our results, coupled with prior research, indicate that public health scholars’ efforts at prevention and intervention may be strengthened by leveraging men’s social networks to ameliorate down-stream health effects of racial discrimination.

Limitations

The present study used a prospective design to examine the cumulative effects of experiences of racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs on Black American men’s COVID vaccine hesitancy. Several limitations should be noted. The observational nature of the study prevents causal conclusions. Our inability to draw causal conclusions was further limited by our mediator being measured at the same time point as our outcome. A longitudinal examination of these associations for the COVID vaccine, and other adult vaccines, is warranted for future research. Furthermore, participant’s ethnic identity may be influenced by their level of perceived social support in that receiving social support from individuals of the same ethnic group may increase one’s connection to their own ethnic identity. Our finding of small correlation (r = 0.29) would support such a hypothesis; however, our limited sample size prohibited us from examining a potential three-way interaction. Future studies, with larger sample sizes, would benefit from examining this potential association. Additionally, this study focused on men living in rural communities; findings may not generalize to men living in urban settings or other regions of the USA. This limitation is less of a concern because nascent research indicates that there are not substantial differences based on rurally among the variables of interest [11, 12]. The use of self-report measures also may lead to biases related to subject recall and social desirability [37]. These limitations notwithstanding the present study provides empirical evidence of cumulative experiences of racial discrimination and COVID conspiracy beliefs influence Black American men’s vaccine beliefs.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the cumulative impact of exposure to racial discrimination on Black American men’s COVID vaccine hesitancy. Findings underscore the roles of disenfranchisement and marginalization in undermining Black American men’s trust in the government and other agencies of influence, which then carries forward to influence their health-related beliefs and decision-making. These insights may be used by public health scientists and interventionists to enhance programming aimed at promoting vaccine uptake by demonstrating the importance of rebuilding cultural trust with the Black American community, in general, and Black American men, in particular.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

The first author conceptualized the study, conducted statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. The second and last author provided the data, contributed to the writing, and commented on drafts of the manuscript. The third author contributed to the writing and commented on drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under Grant R01DA029488, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism under Grant R01AA026623, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UL1TR002378 and TL1TR002382. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, or the National Institutes of Health. The analysis presented was not disseminated before the creation of this article; however, this study’s dataset has been used in prior unrelated publications.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

All study protocols were approved by the University’s Human Subjects Review Board.

Consent to Participate

Participants provided written informed consent before participating in this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahmed AT, Mohammed SA, Williams DR (2007) Racial discrimination & health: pathways & evidence. Indian J Med Res 126(4), 318–327. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18032807 [PubMed]

- 2.Alcendor DJ. Targeting COVID vaccine hesitancy in rural communities in Tennessee: implications for extending the COVID-19 pandemic in the South. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9(11):1279. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allington D, McAndrew S, Moxham-Hall V, Duffy B (2021) Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Anders SL, Frazier PA, Frankfurt SB. Variations in criterion A and PTSD rates in a community sample of women. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(2):176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrade G. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy, conspiracist beliefs, paranoid ideation and perceived ethnic discrimination in a sample of University students in Venezuela. Vaccine. 2021;39(47):6837–6842. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews N, Stowe J, Kirsebom F, Toffa S, Rickeard T, Gallagher E, Gower C, Kall M, Groves N, O'Connell AM, Simons D, Blomquist PB, Zaidi A, Nash S, Iwani Binti Abdul Aziz N, Thelwall S, Dabrera G, Myers R, Amirthalingam G, LopezBernal J. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against the omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(16):1532–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arbuckle JL (1996) Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques 243:243–277. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- 8.Awang Z (2012) Structural equation modeling using AMOS graphic. Penerbit Universiti Teknologi MARA.

- 9.Ball K, Lawson W, Alim T. Medical mistrust, conspiracy beliefs & HIV-related behavior among African Americans. J Psychol Behav Sci. 2013;1(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baptiste DL, Josiah NA, Alexander KA, Commodore‐Mensah Y, Wilson PR, Jacques K, Jackson D (2020) Racial discrimination in health care: an “us” problem. In: Wiley Online Library. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bleich SN, Findling MG, Casey LS, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, SteelFisher GK, Sayde JM, Miller C. Discrimination in the United States: experiences of Black Americans. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(Suppl 2):1399–1408. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogart LM, Dong L, Gandhi P, Klein DJ, Smith TL, Ryan S, Ojikutu BO. COVID-19 vaccine intentions and mistrust in a national sample of Black Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113(6):599–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bollen KA, Stine R. Direct and indirect effects: classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociol Methodol. 1990;20:115–140. doi: 10.2307/271084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR (2016) Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bowleg L, Burkholder GJ, Massie JS, Wahome R, Teti M, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. Racial discrimination, social support, and sexual HIV risk among Black heterosexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):407–418. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandon DT, Isaac LA, LaVeist TA. The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(7):951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brody GH, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Murry VM, Logan P, Luo Z. Linking perceived discrimination to longitudinal changes in African American mothers’ parenting practices. J Marriage Fam. 2008;70(2):319–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00484.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brody GH, Yu T, Miller GE, Chen E. Discrimination, racial identity, and cytokine levels among African-American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(5):496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brondolo E, Brady Ver Halen N, Pencille M, Beatty D, Contrada RJ. Coping with racism: a selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caldwell JT, Ford CL, Wallace SP, Wang MC, Takahashi LM. Intersection of living in a rural versus urban area and race/ethnicity in explaining access to health care in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1463–1469. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022) Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- 22.Cheng KJG, Sun Y, Monnat SM. COVID-19 death rates are higher in rural counties with larger shares of Blacks and Hispanics. J Rural Health. 2020;36(4):602–608. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutrona CE, Russell DW. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Adv Pers Relatsh. 1987;1(1):37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis J, Wetherell G, Henry P. Social devaluation of African Americans and race-related conspiracy theories. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2018;48(7):999–1010. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daw J, Verdery AM, Margolis R. Kin Count(s): educational and racial differences in extended kinship in the United States. Popul Dev Rev. 2016;42(3):491–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drinkwater KG, Dagnall N, Denovan A, Walsh RS. To what extent have conspiracy theories undermined COVID-19: strategic narratives? Front Commun. 2021;6:576198. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.576198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(11):1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Dev Psychol. 2006;42(2):218. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groom HC, Zhang F, Fisher AK, Wortley PM. Differences in adult influenza vaccine-seeking behavior: the roles of race and attitudes. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(2):246–250. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318298bd88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes AF, Scharkow M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? Psychol Sci. 2013;24(10):1918–1927. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 2002;49(1):11–34. doi: 10.1525/sp.2002.49.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaiswal J, Halkitis PN. Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):79–85. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1619511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson PO, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Stat Res Mem. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications.

- 35.Kogan SM, Cho J, Oshri A. The influence of childhood adversity on rural Black men's sexual risk behavior. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(6):813–822. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9807-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolar SK, Wheldon C, Hernandez ND, Young L, Romero-Daza N, Daley EM. Human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge and attitudes, preventative health behaviors, and medical mistrust among a racially and ethnically diverse sample of college women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(1):77–85. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larson RB. Controlling social desirability bias. Int J Mark Res. 2019;61(5):534–547. doi: 10.1177/1470785318805305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C. Little's Test of Missing Completely at Random. Stata J: Promot Commun Stat Stata. 2013;13(4):795–809. doi: 10.1177/1536867x1301300407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little RJ, Rubin DB (2019) Statistical analysis with missing data (Vol. 793). John Wiley & Sons.

- 40.Lu P-J, O'Halloran A, Bryan L, Kennedy ED, Ding H, Graitcer SB, Santibanez TA, Meghani A, Singleton JA. Trends in racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination coverage among adults during the 2007–08 through 2011–12 seasons. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(7):763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu P-J, O’Halloran A, Williams WW, Lindley MC, Farrall S, Bridges CB. Racial and ethnic disparities in vaccination coverage among adult populations in the US. Vaccine. 2015;33:D83–D91. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100495. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Roser M, Hasell J, Appel C, Giattino C, Rodés-Guirao L. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(7):947–953. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCallum JM, Arekere DM, Green BL, Katz RV, Rivers BM. Awareness and knowledge of the US Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee: implications for biomedical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(4):716. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McConnell K, Merdjanoff AA, Burow P, Mueller T, Farrell J (2021) Rural safety net use during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- 46.Moore JX, Gilbert KL, Lively KL, Laurent C, Chawla R, Li C, Johnson R, Petcu R, Mehra M, Spooner A, Kolhe R, Ledford CJW. Correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among a community sample of African Americans living in the Southern United States. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9(8):879. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2017) Mplus user's guide statistical analysis with latent variables (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- 48.Nuzhath T, Tasnim S, Sanjwal RK, Trisha NF, Rahman M, Mahmud SF, Arman A, Chakraborty S, Hossain MM (2020) COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy, misinformation and conspiracy theories on social media: a content analysis of Twitter data.

- 49.Ojha RP, Stallings-Smith S, Flynn PM, Adderson EE, Offutt-Powell TN, Gaur AH. The impact of vaccine concerns on racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccine uptake among health care workers. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e35–e41. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, Burrow AL. Racial discrimination and the stress process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96(6):1259–1271. doi: 10.1037/a0015335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gupta A, Kelaher M, Gee G. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parsons S, Simmons W, Shinhoster F, Kilburn J. A test of the grapevine: an empirical examination of conspiracy theories among African Americans. Sociol Spectr. 1999;19(2):201–222. doi: 10.1080/027321799280235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pizarro JJ, Cakal H, Méndez L, Da Costa S, Zumeta LN, Gracia Leiva M, Basabe N, Navarro Carrillo G, Cazan AM, Keshavarzi S (2020) Tell me what you are like and I will tell you what you believe in: Social representations of COVID-19 in the Americas, Europe and Asia.

- 54.Poteat T, Millett GA, Nelson LE, Beyrer C. Understanding COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities among black communities in America: the lethal force of syndemics. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prelow HM, Mosher CE, Bowman MA. Perceived racial discrimination, social support, and psychological adjustment among African American college students. J Black Psychol. 2006;32(4):442–454. doi: 10.1177/0095798406292677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and mortality among Black patients and White patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2534–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa2011686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Probst JC, Fozia A (2019) Social determinants of health among the rural African American population. Rural & Minority Health Research Center. https://www.sc.edu/study/colleges_schools/public_health/research/research_centers/sc_rural_health_research_center/documents/socialdeterminantsofhealthamongtheruralafricanamericanpopulation.pdf

- 58.Pullen E, Perry B, Oser C. African American women's preventative care usage: the role of social support and racial experiences and attitudes. Sociol Health Illn. 2014;36(7):1037–1053. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiao S, Tam CC, Li X (2020) Risk exposures, risk perceptions, negative attitudes toward general vaccination, and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among college students in South Carolina. Am J Health Promot 08901171211028407. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Quinn SC, Jamison A, Freimuth VS, An J, Hancock GR, Musa D. Exploring racial influences on flu vaccine attitudes and behavior: results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine. 2017;35(8):1167–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quinn SC, Jamison AM, An J, Hancock GR, Freimuth VS. Measuring vaccine hesitancy, confidence, trust and flu vaccine uptake: results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine. 2019;37(9):1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rémy V, Largeron N, Quilici S, Carroll S. The economic value of vaccination: why prevention is wealth. J Market Access Health Policy. 2015;3(1):29284. doi: 10.3402/jmahp.v3.29284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Remy V, Zollner Y, Heckmann U. Vaccination: the cornerstone of an efficient healthcare system. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2015;3(1):27041. doi: 10.3402/jmahp.v3.27041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosenberg ES, Dorabawila V, Easton D, Bauer UE, Kumar J, Hoen R, Hoefer D, Wu M, Lutterloh E, Conroy MB, Greene D, Zucker HA. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness in New York State. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(2):116–127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rutledge PE. Trump, COVID-19, and the war on expertise. Am Rev Public Admin. 2020;50(6–7):505–511. doi: 10.1177/0275074020941683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saied SM, Saied EM, Kabbash IA, Abdo SAEF. Vaccine hesitancy: beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. 2021;93(7):4280–4291. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanders Thompson VL. Coping responses and the experience of discrimination 1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;36(5):1198–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00038.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Savoia E, Piltch-Loeb R, Goldberg B, Miller-Idriss C, Hughes B, Montrond A, Kayyem J, Testa MA. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: socio-demographics, co-morbidity, and past experience of racial discrimination. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9(7):767. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA (2003). Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. J Health Soc Behav 302–317. [PubMed]

- 70.Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RLH. Racial identity matters: the relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. J Res Adolesc. 2006;16(2):187–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sellers RM, Rowley SA, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, Smith MA. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: a preliminary investigation of reliability and constuct validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(4):805. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(5):1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith AC, Woerner J, Perera R, Haeny AM, Cox JM (2021) An investigation of associations between race, ethnicity, and past experiences of discrimination with medical mistrust and COVID-19 protective strategies. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Smith EP, Brookins CC. Toward the development of an ethnic identity measure for African American youth. J Black Psychol. 1997;23(4):358–377. doi: 10.1177/00957984970234004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stojanov A, Bering JM, Halberstadt J. Does perceived lack of control lead to conspiracy theory beliefs? Findings from an online MTurk sample. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, Marder EP, Raz KM, El Burai Felix S, Tie Y, Fullerton KE (2020) Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance - United States, January 22-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69(24):759–765. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Swim JK, Hyers LL, Cohen LL, Fitzgerald DC, Bylsma WH. African American college students’ experiences with everyday racism: characteristics of and responses to these incidents. J Black Psychol. 2003;29(1):38–67. doi: 10.1177/0095798402239228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tomljenovic H, Bubic A, Erceg N. It just doesn’t feel right–the relevance of emotions and intuition for parental vaccine conspiracy beliefs and vaccination uptake. Psychol Health. 2020;35(5):538–554. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2019.1673894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Utsey SO, Lanier Y, Williams O, III, Bolden M, Lee A. Moderator effects of cognitive ability and social support on the relation between race-related stress and quality of life in a community sample of black Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006;12(2):334. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Mulukom V, Pummerer L, Alper S, Bai H, Cavojova V, Farias J, Kay CS, Lazarevic LB, Lobato EJ, Marinthe G (2020) Antecedents and consequences of Covid-19 conspiracy beliefs: a systematic review. PsyarXiv 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Vikram K, Vanneman R, Desai S. Linkages between maternal education and childhood immunization in India. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(2):331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8(3):482. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Williams S, Mohammed SA, Moomal H, Stein DJ. Perceived discrimination, race and health in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Willis DE, Andersen JA, Bryant-Moore K, Selig JP, Long CR, Felix HC, Curran GM, McElfish PA. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: race/ethnicity, trust, and fear. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14(6):2200–2207. doi: 10.1111/cts.13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xiao X, Wong RM. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38(33):5131–5138. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang X, Wei L, Liu Z. Promoting COVID-19 vaccination using the health belief model: does information acquisition from divergent sources make a difference? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):3887. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19073887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang Y, Bennett L. Interactive propaganda: how Fox news and Donald Trump co-produced false narratives about the COVID-19 crisis. In: Aelst PV, Blumler JG, editors. Political Communication in the Time of Coronavirus. Routledge; 2021. pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yehia BR, Winegar A, Fogel R, Fakih M, Ottenbacher A, Jesser C, Bufalino A, Huang RH, Cacchione J. Association of race with mortality among patients hospitalized with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2018039. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yu Q, Scribner RA, Leonardi C, Zhang L, Park C, Chen L, Simonsen NR. Exploring racial disparity in obesity: a mediation analysis considering geo-coded environmental factors. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. 2017;21:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang S, Yin Z, Suraratdecha C, Liu X, Li Y, Hills S, Zhang K, Chen Y, Liang X. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of caregivers regarding Japanese encephalitis in Shaanxi Province. China Public Health. 2011;125(2):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.