Abstract

Previous studies have shown that amyloid-β oligomers (AβO) bind with high affinity to cellular prion protein (PrPC). The AβO-PrPC complex binds to cell-surface co-receptors, including the laminin receptor (67LR). Our current studies revealed that in Neuroscreen-1 cells, 67LR is the major co-receptor involved in the cellular uptake of AβO and AβO-induced cell death. Both pharmacological (dibutyryl-cAMP, forskolin, rolipram) and physiological (pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide) cAMP-elevating agents decreased cell-surface PrPC and 67LR, thereby attenuating the uptake of AβO and the resultant neuronal cell death. These cAMP protective effects are dependent on protein kinase A, but not dependent on the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP. Conceivably, cAMP protects neuronal cells from AβO-induced cytotoxicity by decreasing cell-surface associated PrPC and 67LR.

Keywords: amyloid-β, 67 kDa laminin receptor, cAMP, protein kinase A, PACAP, cellular prion protein, neuronal cell death

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease with progressive dementia that is characterized by synaptic loss and neuronal death [1]. Despite its limitations, the amyloid (Aβ) hypothesis is considered to be one of the prevailing hypotheses put forward to explain the pathogenesis of AD [2–5]. Soluble Aβ oligomers (AβO) are attributed to play a crucial role in the onset of this disease [6]. Various studies have shown that extracellular AβO initiates cell signaling by binding to high-affinity cell surface receptors [7,8]. AβO are subsequently internalized into neurons and sequestered to various cellular organelles, causing hyperphosphorylation of tau, dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, dysfunction of mitochondria, and increased production of reactive oxygen species, all of which are considered to be central to the pathogenesis of AD [9–12]. However, the mechanisms by which AβO enter into neurons, as well as the cellular signals that influence the sensitivity/resistance of neuronal cells to AβO-induced cell death, are largely unknown.

Binding studies carried out with Aβ(1–42) suggested that the lipid raft-associated cellular prion protein (PrPC) is a major high-affinity receptor for AβO [13]. The AβO-PrPC complex may in turn bind to various cell-surface co-receptors to mediate AβO-induced toxicity in neuronal cells [7,8]. Another lipid raft-associated protein, 67 kDa laminin receptor (67LR), is one of the co-receptors for the AβO-PrPC complex and is involved in the internalization of AβO and subsequent cell death [14,15]. 67LR is a nonintegrin-type cell-surface receptor originally discovered as a laminin-binding protein associated with cancer cell invasion and metastasis [16]. Subsequently, it has been shown to internalize various viruses and bacteria [16]. Others have shown that micromolar concentrations of green tea polyphenols induce cancer cell death via binding to 67LR [17]. We have previously shown that 67LR can function as a neuroprotective receptor for agents such as green tea polyphenols (nanomolar concentrations) and soluble laminin by elevating intracellular cAMP [18,19]. Others have shown that cAMP can protect cortical neurons from death induced by Aβ(25–35) [20]. However, the intracellular signals that influence the cell-surface levels of 67LR, PrPC, and other AβO receptors are largely unknown.

The physiological neuropeptide, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), is neuroprotective and neurotrophic [21,22]. PACAP27 was shown to protect neuronal cells from AβO-induced cell death by correlating with higher intracellular levels of cAMP [23]. PACAP is lower in AD patients compared to age-matched healthy people [24]. Administration of PACAP enhanced cognitive ability in AD transgenic mice [25]. Although PACAP is known to both elevate various intracellular messengers and activate several protein kinases [26,27], how it protects neurons from AβO-induced cell death is not known.

Here we report for the first time that both pharmacological (cell-permeable dibutyryl-cAMP, forskolin, and rolipram) and physiological (PACAP) cAMP-elevating agents decrease cell-surface associated PrPC and 67LR and thereby attenuate cellular uptake of AβO and neuronal cell death. This proposed new mechanism explains how these cAMP-elevating agents protect against AβO-induced neuronal cell death.

Materials and methods

Materials

Aβ(1–42).HFIP (human), Aβ(42–1), and HiLyte Fluor 555-labeled Aβ(1–42) were from AnaSpec. Dibutyryl-cAMP, forskolin, rolipram, isobutylmethyl-xanthine (IBMX), and thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. PACAP(1–38) peptide was from Abbiotec. SQ 22536, KT5720, and ESI-09 were from EMD Millipore. Anti-67LR mouse monoclonal antibody (clone MluC5), Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-67LR mouse monoclonal antibody (H-2), and mouse IgM were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Alexa Fluor 647-labeled anti-CD230 (prion) mouse monoclonal antibody (808008) and Alexa Fluor 594-labeled anti-Aβ mouse monoclonal antibody (800716) were from BioLegend.

Cell culture

Protein kinase A (PKA)-deficient PC12 cells (A132.7), originally cloned by Dr. John Wagner, and wild-type PC12 cells were kind gifts from Dr. Louis Hersh (University of Kentucky, Lexington). Stocks of Neuroscreen-1 (NS-1) cells (clone derived from PC12 cells), PKA-deficient PC12 cells, and wild-type PC12 cells were grown on flasks coated with poly-L-lysine in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum, 5% fetal calf serum, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 0.05 mg/ml streptomycin.

Oligomerization of Aβ peptides

Aβ(1–42).HFIP was dissolved in a small volume of dimethyl sulfoxide, aliquoted, and stored by freezing at −20°C. An aliquot was diluted to the desired concentration with F12 medium [28]. To oligomerize, samples were kept at room temperature for 1 day. With this method, it was previously shown that a total of 1 μM of Aβ(1–42) peptide corresponded to approximately 10 nM of the oligomeric species [28]. Concentrations of AβO are expressed in monomer equivalents. We used Aβ(42–1) as a negative control for Aβ(1–42).

AβO-induced cell death assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to reach 25% confluency. The medium was then removed and the cells were washed once with phenol red-free medium containing very low amounts of serum (0.2% heat-inactivated horse serum and 0.1% fetal calf serum) and then incubated for 24 h in the medium to serum-starve the cells. Next, the cells were preincubated with one of the various protective agents for 1 h and then incubated with increasing concentrations of Aβ peptides at 37° C for 24 h. Cell death was determined by the MTT method as previously described [19]. Unless otherwise specified, cells were grown in a phenol red-free RPMI medium with serum and then serum-starved for 24 h prior to treatment with protective agents and AβO.

Cellular uptake of AβO

Cells were grown on poly-D-lysine-coated 12-mm glass coverslips (Deckglaser) in a 24-well culture plate to 50% confluency and serum-starved in a phenol red-free medium as stated above. Cells were then treated for 1 h with protective agents and then incubated with 100 nM oligomerized Aβ labeled with a fluorescent dye (HiLyte Fluor 555) for 2 h. This was followed by washing cells twice with Hank’s balanced salt solution and then fixing them with 4% paraformaldehyde. Nuclei were stained with 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were taken in a blinded fashion using the LSM 800 Zeiss confocal microscope.

In another approach, uptake of AβO was determined by using unlabeled Aβ. Cells grown on coverslips were pretreated with protective agents and then incubated with unlabeled AβO as described above. Then, cells were fixed and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X-100. The permeabilized cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-labeled anti-human Aβ mouse monoclonal antibody at 4°C for 24 h. Cells were then washed and confocal images were taken in a blinded fashion.

Cell-surface distribution of PrPC and 67LR

NS-1 cells grown on glass coverslips were treated with the indicated agents for 1 h. The cells were then fixed and used without permeabilization to detect only the cell-surface associated PrPC and 67LR. Cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-67LR mouse monoclonal antibody (1:300 dilution) along with Alexa Fluor 647-labeled anti-CD230 (prion) mouse monoclonal antibody (1:300 dilution) at 4°C for 24 h. After washing the cells, confocal images were taken.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as means ± SE of 4 to 6 replicate samples. Statistical analyses were performed with the GraphPad Prism software (version 9). Statistical significance was determined by multiple t-tests. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Neuronal cell death induced by nanomolar concentrations of Aβ(1–42)

Since only low nanomolar concentrations of soluble Aβ peptides were found in the brains of AD patients [29], it is important to study the mechanisms that cause neuronal cell death induced by these low concentrations of Aβ. The conditions reported in many previous studies required 25 to 100 μM high concentrations of Aβ(1–42) to induce neuronal cell death [30–32]. At such high concentrations, nonspecific low-affinity receptors are also affected. By limiting concentrations of Aβ to nanomolar, only high-affinity receptors are affected, thus making it possible to study mechanisms pharmacologically relevant to AD prevention or treatment. We predicted the possibility that some components present in the cell culture medium do not favor AβO-induced cell death, thus requiring higher concentrations of AβO to induce cell death.

By growing cells in a phenol red-free medium that contains serum (10% heat-inactivated horse serum and 5% fetal calf serum) for two passages or more, we found that it substantially enhanced AβO-induced NS-1 cell death as measured by a decrease in MTT reduction (Fig. 1A). Simply maintaining cells for 24 h in a phenol red-free medium enhanced the sensitivity of NS-1 cells to AβO-induced cell death. Cells that were subjected to serum starvation, but had phenol red present in the medium, also showed a small but significant increase in cell death. A combination of phenol red-free medium and serum starvation increased cell death to a greater extent than originally anticipated. The dose-response showed that substantial (30 to 50%) cell death occurs with 10 to 100 nM Aβ(1–42). The control Aβ(42–1) peptide did not induce significant cell death at these concentrations (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of AβO-induced cell death by phenol red (PR), serum, 67LR antibody, and cAMP-elevating agents. (A) Increased cell death in phenol red-free medium and by serum starvation. NS-1 cells were kept at 37° C for 24 h in standard phenol red- and serum-containing medium (control), phenol red- and very low serum-containing medium (for serum starvation), phenol red-free but serum-containing medium, or phenol red-free and very low serum-containing medium. Cells were then treated with AβO (expressed as monomer equivalents) for 24 h. Next, cell death was determined with an MTT assay and the values are expressed as absorbance at 550 nm (as a percentage of control). Each value is the mean ± SE from 4 to 6 replicates estimations. Asterisks indicate statistical differences from the control standard phenol red- and serum-containing medium (p<0.05). (B) Prevention of AβO-induced cell death by the 67LR-blocking antibody. Cells were kept for 24 h in a phenol red-free and very low serum-containing medium for 24 h and then pretreated with 67LR antibodies (0.4 μg/ml) or control IgM (0.4 μg/ml) for one hour. AβO-induced cell death was then determined as described in A. (C) Prevention of AβO-induced cell death by dibutyryl-cAMP. NS-1 cells were pretreated with 200 μM dibutyryl-cAMP (dibu-cAMP) along with 100 μM IBMX for 1 h and then AβO-induced cell death was determined. (D) Prevention of AβO-induced cell death by c-AMP elevating agents. NS-1 cells were pretreated with 5 μM forskolin or 2 μM rolipram for 1 h and then AβO-induced cell death was determined.

Pharmacological cAMP-elevating agents protect NS-1 cells from 67LR-mediated AβO-induced cell death

Previous studies have shown that 67LR blocking-antibody prevented AβO-induced death in N2a cells [14]. Because our mechanistic studies with cAMP used NS-1 cells, we first tested to determine whether this previously reported role of 67LR with N2a cells also applied to NS-1 cells. Our studies confirmed that the 67LR blocking-antibody completely protected cells from death induced by Aβ up to 250 nM concentrations (Fig. 1B). This protection was not seen with the IgM control. This suggests that 67LR is the major co-receptor that mediates AβO-induced cell death in NS-1 cells. It is interesting to note that when cells were protected effectively with 67LR-blocking antibodies, low concentrations (10 to 25 nM) of Aβ(1–42) indeed stimulated cell growth to a small degree (Fig. 1 A–D).

We used a variety of pharmacological cAMP-elevating agents including dibutyl-cAMP, a cell-permeable analog of cAMP; forskolin, an activator of adenylyl cyclase (AC); and rolipram, a cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor. These compounds all substantially protected neuronal cells from AβO-induced cell death (Fig. 1C and Fig. 1D). This suggests that cAMP may contribute to the resistance of NS-1 cells against AβO-induced cell death. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (100 nM), an activator of protein kinase C (PKC), did not protect NS-1 cells from AβO-induced cell death (data not shown).

cAMP-elevating agents decrease cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR.

Although we did not add PrPC along with AβO, PC12 cells express PrPC on their cell surface [33]. As shown in Fig. 2, treatment with cAMP-elevating agents (dibutyryl-cAMP, forskolin, and rolipram) decreased cell-surface levels of both PrPC and 67LR. This correlates well with the ability of these agents to decrease AβO-induced cell death, which requires both cell-surface associated PrPC and 67LR.

Fig. 2.

Decrease in cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR by cAMP-related agents. NS-1 cells that were grown on coverslips were treated with 200 μM dibutyryl-cAMP (dibu-cAMP) along with 100 μM IBMX, 5 μM forskolin, or 2 μM rolipram for 1 h. Then, the treated cells were fixed and stained for PrPC and 67LR by incubation at 4°C for 24 h with Alexa Fluor 647-labeled anti-CD230 (prion) mouse monoclonal antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-67LR mouse monoclonal antibody, respectively. Nuclei were stained with 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Confocal images were taken in a blinded fashion.

67LR-blocking antibody and cAMP-related agents decrease cellular uptake of AβO

Since 67LR antibodies decrease AβO-induced cell death and cAMP-elevating agents decrease both AβO-induced cell death and surface levels of PrPC and 67LR, we determined whether 67LR antibodies and cAMP-related agents attenuate the cellular uptake of AβO. NS-1 cells were able to take up fluorescently labeled Aβ(1–42) oligomers without the addition of any cAMP-elevating agents, suggesting that AβO uptake does not require elevated cAMP. The uptake of AβO was substantially decreased by preincubation of NS-1 cells with a 67LR-blocking antibody (Fig. 3A). This suggests that 67LR plays a crucial role in mediating the uptake of AβO. In addition, prior treatment with cAMP-elevating agents (dibutyryl-cAMP, forskolin, and rolipram) blocked subsequent AβO uptake (Fig. 3A). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that cAMP-elevating agents may increase the efflux of AβO, thus causing a decrease in intracellular AβO.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of cellular uptake of Aβ(1–42) by 67LR antibody and cAMP-elevating agents. (A) Decrease in the uptake of fluorescently labeled Aβ(1–42) by various agents. NS-1 cells that were grown on coverslips were pretreated with 67LR antibody (0.4 μg/ml), 200 μM dibutyryl-cAMP (dibu-cAMP) along with 100 μM IBMX, 5 μM forskolin, or 2 μM rolipram for 1 h. Then cells were incubated for 2 h with 100 nM fluorescently labeled Aβ(1–42) that was previously oligomerized. The Aβ peptide that was taken up by the cells was visualized by taking confocal images. (B) Decrease in the cellular uptake of unlabeled Aβ (1–42) by various agents. Cells were treated with various agents as described in Fig. 3A, except native unlabeled Aβ was used instead of labeled Aβ. Cells were then permeabilized with a detergent and Aβ that had entered into cells were visualized by staining with Alexa Fluor 594-labeled anti-human Aβ mouse monoclonal antibody.

Despite a wide application of fluorescently labeled Aβ for determining the cellular uptake of Aβ, some studies have shown that the fluorescent label may influence Aβ oligomerization, cellular uptake, and trafficking [34]. Therefore, we also determined the cellular uptake of unlabeled Aβ. We first incubated cells with native unlabeled Aβ, permeabilized the cells, and then applied fluorescent dye-conjugated anti-Aβ antibody to determine the Aβ taken up by the cells. Overall, the results obtained with native Aβ are similar to those of fluorescently labeled Aβ: both 67LR-blocking antibody and cAMP-elevating agents decreased cellular uptake of native AβO (Fig. 3B). However, the pattern of intracellular distribution appears to be different for native Aβ as we used detergent-permeabilized cells for staining native Aβ (Fig. 3B) versus unpermeabilized cells for fluorescently labeled Aβ (Fig. 3A).

Role of PKA in protecting neuronal cells from AβO-induced cell death

Since cAMP uses PKA as one of its effectors, we determined the role of PKA in conferring resistance to AβO-induced cell death. We compared wild-type PC12 cells expressing PKA with PKA-deficient PC12 cells to determine whether PKA contributes to resistance to AβO-induced cell death. As shown in Fig. 4A, PKA-deficient PC12 cells were found to be more sensitive to AβO-induced cell death than wild-type PC12 cells, supporting the role of PKA in protecting against AβO cytotoxicity. The PKA-deficient PC12 cells were also totally protected with a 67LR-blocking antibody (Fig. 4B), suggesting that 67LR is the major pathway that mediates AβO-induced cell death in this cell type as well.

Fig. 4.

Relative susceptibility of PC12 wild-type and PKA-deficient PC12 cells to AβO. (A) PKA-deficient PC12 cells are more susceptible to AβO-induced cell death than the wild-type PC12 cells. Both cell types were conditioned with phenol red-free medium and serum starvation. Then, they were treated with AβO (expressed as monomer equivalent) for 24 h and cell death was determined. Asterisks indicate significantly different results from PC12 wild-type cells (p<0.05). (B) Prevention of AβO-induced death of PKA-deficient PC12 cells by the 67LR-blocking antibody. Cells were pretreated with 67LR antibody (0.4 μg/ml) or its control IgM (0.4 μg/ml) for 1 h and then AβO-induced cell death was determined.

We found that cAMP-elevating agents could not protect PKA-deficient cells from AβO-induced cell death (data not shown). However, these agents protected NS-1 and PC12 wild-type cells that have PKA (Fig. 1). We did not find any appreciable difference in the levels of PrPC and 67LR on the cell surfaces of NS-1, wild-type PC12 cells, and PKA-deficient cells. We found that cAMP-elevating agents were found to decrease levels of cell-surface proteins in both NS-1 cells and PC12 wild-type cells (Fig. 2), but not in PKA-deficient cells (Fig. 5). This supports the finding that cAMP-elevating agents protect NS-1 and PC12 wild type cells but not PKA-deficient cells from AβO-induced cell death.

Fig. 5.

A lack of decrease in cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR by cAMP-related agents in PKA-deficient PC12 cells. Cells grown on coverslips were treated with dibutyryl-cAMP (200 μM) along with IBMX (100 μM), forskolin (5 μM), or rolipram (2 μM) for 1 h. Cells were then stained for PrPC (red), 67LR (green), and nuclei (blue), and confocal images were taken in a blinded fashion.

PACAP decreases cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR, AβO uptake, and cell death

The pharmacological cAMP-elevating agents that we used in general increase concentrations of cAMP to a high extent for a longer period in various cellular compartments. On the contrary, physiological hormones transiently elevate concentrations of cAMP to a limited extent in selected compartments. Previous studies showed that PACAP27 protected PC12 cells from AβO-induced death, which correlated with the elevation of cAMP [23]. The causal role of cAMP and the downstream mechanism by which PACAP27 protects against AβO-induced cell death are not known. Therefore, we determined these mechanisms utilizing PACAP38, the major form of PACAP in the brain. The PACAP27 protective effect was previously shown to be biphasic [23]. Therefore, we used PACAP38 at a broad range of concentrations. As shown in Fig. 6A, PACAP38 equally protected NS-1 cells over a 0.1 to 10 nM range of concentrations from AβO-induced cell death. Therefore, in all our experiments we used PACAP38. PACAP mediates its actions via the PAC1 receptor in PC12 cells [35]. Since PAC1 activation by PACAP leads to the elevation of various second messengers (inositol triphosphate, Ca2+, diacylglycerol, and cAMP) and activation of several protein kinases (PKC, ERK, and PKA) [26], we determined whether blocking the generation of cAMP by inhibiting AC can decrease the PACAP protective effect. As shown in Fig. 6B, SQ 22536, an AC inhibitor, completely abolished the action of PACAP in protecting against AβO-induced cell death. In addition to AC, SQ 22536 inhibits an additional site in cAMP signaling [36]. Nevertheless, SQ 22536 confirms the causal role of cAMP in mediating the ability of PACAP to decrease AβO-induced cell death. PKA-specific inhibitor, KT5720, blocked the protective effect of PACAP (Fig. 6C). This is in agreement with our current results obtained with PKA-deficient cells showing higher susceptibility to AβO-induced cell death (Fig. 4A). Contrarily, ESI-09, a specific inhibitor for the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac), did not inhibit PACAP’s protective ability (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

PACAP protects NS-1 cells from AβO-induced cell death in both an AC- and PKA-dependent manner. (A) PACAP decreased AβO-induced cell death. NS-1 cells in 96-well plates were initially treated with a broad range of concentrations (0.1, 1, 10 nM) of PACAP for 1 h followed by treatment with increasing concentrations of AβO for 24 h. Cell death was determined by MTT assay and the values are expressed as absorbance at 550 nm (as a percentage of control). Each value is the mean ± SE from 4 to 6 replicates estimations. Asterisks indicate the statistical difference from controls treated with AβO without PACAP (p<0.05). (B) Inhibition of AC attenuated the ability of PACAP to protect NS-1 cells from AβO-induced cell death. Cells were initially treated with AC inhibitor SQ 22536 (100 μM) for 1 h. This was followed by treatment with PACAP and AβO as in Fig. 6A. (C) Inhibition of PKA abolishes the ability of PACAP to protect cells from AβO-induced death. Conditions were the same as in Fig. 6B except for PKA inhibitor KT5720 (0.2 μM) was used instead of SQ 22536. (D) Lack of a role for Epac in the PACAP action to protect from AβO-induced cell death. Cells are initially treated with Epac inhibitor, ESI-09 (10 μM) for 1h followed by an AβO treatment for 24 h, and then cell death was determined.

Since PACAP decreases AβO-induced cell death in a cAMP-dependent manner in NS-1 cells, we determined whether it decreases cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR. PACAP indeed decreased cell-surface levels of both PrPC and 67LR (Fig. 7). This PACAP’s effect was blocked by pretreating NS-1 cells with AC inhibitor SQ 22536, suggesting the role of cAMP in this action of PACAP. However, PACAP failed to decrease cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR in the PKA-deficient PC12 cells, suggesting the role of PKA in PACAP-mediated decrease in the cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR (Fig. 8). PACAP also decreased cellular uptake of fluorescently labeled AβO in NS-1 cells, which was blocked by pretreatment with SQ 22536 (Fig. 9). Collectively, these results suggest that through the activation of the AC-cAMP-PKA pathway, PACAP decreases cell-surface levels of both PrPC and 67LR and thereby decreases cellular uptake of AβO and AβO-induced cell death.

Fig. 7.

Decrease in cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR by PACAP. NS-1 cells that were grown on coverslips were initially treated with 100 μM SQ 22536 for 1 h followed by a 1 h treatment with 10 nM PACAP. Then the treated cells were fixed and stained for PrPC and 67LR as described in Fig. 2. Confocal images were taken in a blinded fashion.

Fig. 8.

A lack of decrease in the cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR by PACAP in the PKA-deficient PC12 cells. Cells grown on coverslips were treated with PACAP (10 nM) for 1 h. Then the treated cells were stained for PrPC (red) 67LR (green), and nuclei (blue), and confocal images were taken.

Fig. 9.

AC inhibition blocks the ability of PACAP to decrease uptake of fluorescently labeled Aβ(1–42). NS-1 cells that were grown on coverslips were pretreated with AC inhibitor SQ 22536 (100 μM) for 1 h. Then, cells were incubated for 2 h with 100 nM fluorescently labeled Aβ(1–42) that was previously oligomerized. The Aβ peptide that was taken up by the cells was visualized by taking confocal images.

Discussion

Multiple mechanisms may explain why the removal of both phenol red and serum from the cell culture medium enhances AβO-induced cell death. Phenol red increases the base level of cAMP in cells [37], which may protect these cells from AβO. Phenol red or its contaminant acts like estrogen and protects cells [38]. Previously, we have shown that serum starvation decreases basal levels of neuroprotective cAMP [19]. Serum albumin binds Aβ(1–42) and impedes its aggregation [39]. Phenol red has antioxidant activity and the serum also has antioxidants [40]. These antioxidants may protect neuronal cells from the oxidative stress induced by AβO [41].

Our current study confirms the previously reported role of 67LR as a co-receptor for AβO-PrPC [14]. In addition, our study shows that 67LR is the major co-receptor for AβO-induced cell death in the NS-1 cell system. Since other receptors bind AβO and AβO-PrPC [7,8], one could expect the 67LR-blocking antibody to only moderately inhibit AβO uptake and AβO-induced cell death. Contrary to this expectation, in the current study, the 67LR antibody substantially inhibited AβO uptake and AβO-induced NS-1 cell death. Previous studies have shown that the binding of AβO to PrPC causes some co-receptors to cluster together in the lipid rafts and form dynamic signaling platforms [7]. It is possible that binding of the antibody to 67LR may affect clustering of other co-receptors present within the vicinity, leading to a substantial decrease in uptake of AβO and thereby AβO-induced cell death. In addition, other AβO receptors such as functional N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) are absent in PC12 cells, a parent cell line from which the NS-1 clone was derived [42,43]. Therefore, in the NS-1 cell type, 67LR may be a major co-receptor for AβO-PrPC.

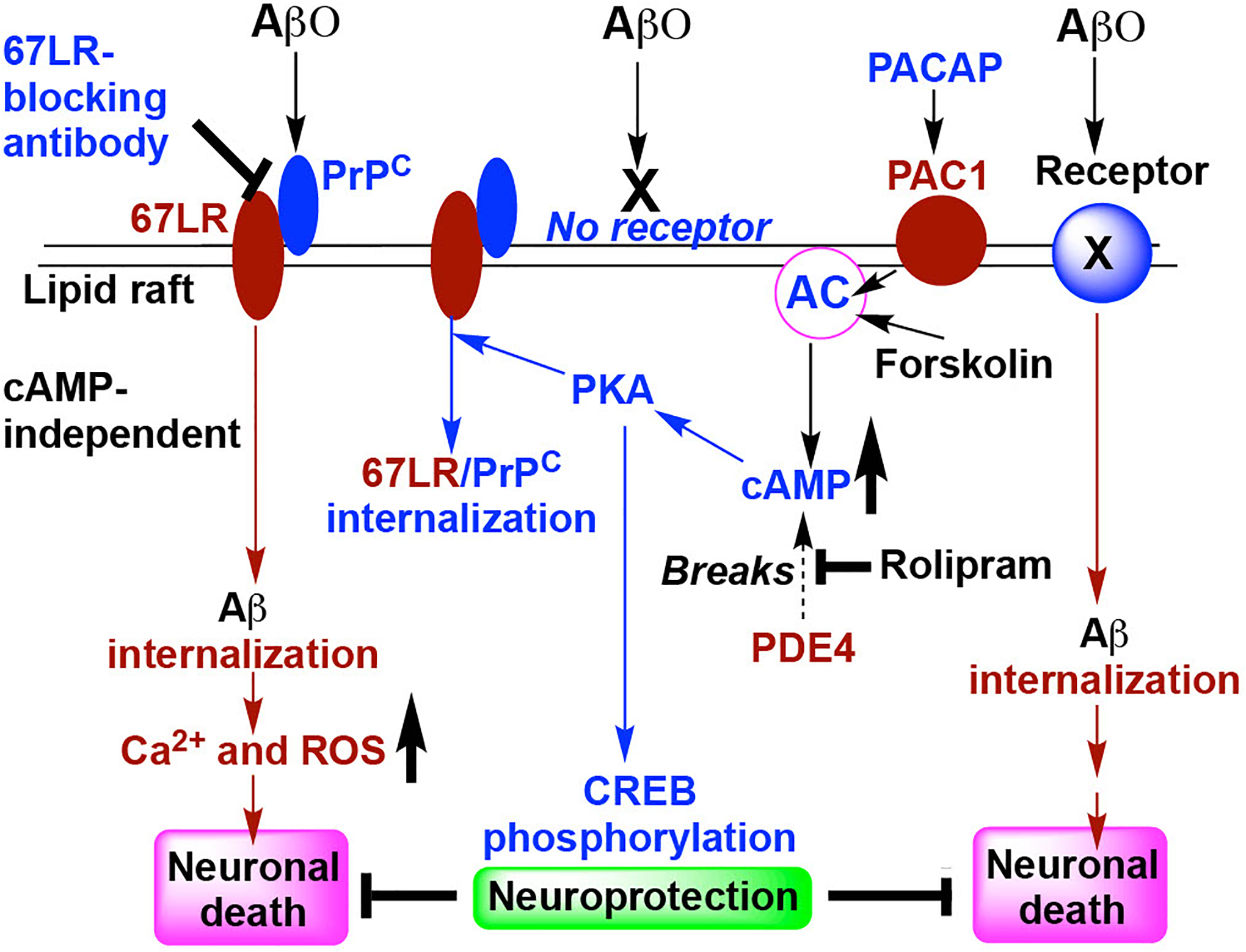

In our previous studies, we have found that cAMP-elevating agents induce endocytosis of 67LR in a PKA-dependent manner [19]. In this study, we found that cAMP-related agents also induce a decrease in cell surface-associated PrPC. 67LR has a PrPC-binding site [16]. Therefore, PrPC may pre-associate with 67LR in the lipid rafts and internalize alongside 67LR in a cAMP-dependent mechanism (Fig. 10). This could deprive the cell surface of PrPC to bind AβO. Consistent with these observations, we found that cAMP-elevating agents substantially decreased 67LR-dependent AβO uptake and AβO-induced cell death. At this juncture, we do not know whether cAMP also internalizes other co-receptors that bind to the AβO-PrPC complex. Recently, we have found that NgR1, which directly binds AβO [13], is also internalized by cAMP [44]. We predict that unlike the internalization of 67LR and PrPC, which requires elevated levels of cAMP, the internalization of AβO-PrPC-67LR complex does not require elevated levels of cAMP (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Schematic presentation describing the possible mechanism by which cAMP and PACAP prevent PrPC-67LR-dependent AβO uptake and AβO-induced cell death. PrPC may pre-associate with 67LR in the membrane lipid rafts. AβO binds to PrPC and the resultant AβO-PrPC-67LR complex may be internalized without the need for elevated cAMP. This leads to hyperphosphorylation of tau and elevations of both intracellular Ca2+ and ROS which induce neuronal cell death. 67LR-blocking antibody inhibits the 67LR interaction with PrPC-AβO. Forskolin (an activator of AC) and rolipram (an inhibitor for PDE4) both increase cAMP which activates its effector PKA. The activation of PKA leads to a decrease in the levels of ligand(AβO)-unoccupied cell-surface PrPC-67LR complex, probably due to its internalization. PACAP acting via its receptor PAC1 activates the AC-cAMP-PKA pathway. Overall, activation of this pathway leads to a subsequent decrease in PrPC-67LR-mediated uptake of AβO, preventing AβO-induced cell death. In addition, we postulate that PKA phosphorylates CREB which may induce the expression of antioxidant enzymes that protect neuronal cells from death induced by AβO being internalized by other (67LR-independent) receptors.

Other cAMP-induced mechanisms may complement protection from AβO-induced neuronal cell death described in the current study. Cyclic-AMP also increases the phosphorylation of the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and subsequent transcriptional activation of neuroprotective antioxidant enzymes [45], which may protect neuronal cells from the cytotoxicity induced by AβO internalized via 67LR-independent mechanisms (Fig. 10). A decrease in cell-surface levels of PrPC/67LR and an increase in CREB phosphorylation by cAMP may cooperate. Previous studies have shown an inactivation of PKA and a concomitant elevation of its regulatory subunit PKAIIα in Aβ-treated hippocampal neurons [46]. Furthermore, a previous study found a decrease in glutamate-induced CREB phosphorylation in Aβ-treated neurons. Preventing AβO uptake at the first step, by decreasing the cell-surface levels of PrPC/67LR, may limit the inactivation of PKA and enhance CREB phosphorylation.

Previous studies have shown that relative to healthy age-matched controls, AD patients and mouse models have much lower cAMP, AC, and PKA levels in various regions of the brain including the hippocampus [47]. AC and PDE have several isoenzymes with different localizations within the neurons, which lead to localized production of different pools of cAMP [48]. Certain pool(s) may be closely associated with the internalization of PrPC and 67LR. PDE inhibitors are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of AD [49]. Unlike the physiological regulations, continuous pharmacological global activation of cAMP pathways can cause cognitive decline, hyperexcitability, and hyperalgesia [50]. Nevertheless, it is possible to locally elevate the cAMP levels necessary to induce 67LR internalization by selecting the appropriate isoenzyme-specific PDE inhibitor.

In summary, cAMP inhibits the uptake of AβO by decreasing the cell-surface levels of PrPC and 67LR, thereby protecting neuronal cells from AβO-induced death. Certainly, additional studies with isolated primary neurons and in vivo models are required to determine the relevance of these mechanisms for protection against AβO-induced neuronal death. This neuroprotective mechanism may be exploited to utilize cAMP-related pharmacological or physiological agents for the prevention and treatment of AD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Louis Hersh at the University of Kentucky for generously providing the PKA-deficient PC12 cell line. We thank Dr. Seth Ruffins and USC Stem Cell Microscopy Core for confocal microscopy. We also thank Julia Vo for her excellent technical assistance.

Funding source

This work was supported by the Keck School of Medicine and National Institutes of Health grants R21 NS116720 (to RG and WJM) and R21 AG059422 (to NRB).

Abbreviations:

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AβO

amyloid-β oligomer

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- 67LR

67 kDa laminin receptor

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

- PrPC

cellular prion protein

- PKA

protein kinase A

- Epac

exchange protein directly activated by cAMP

- NS-1

Neuroscreen-1

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- PDE

cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase

- IBMX

isobutylmethylxanthine

- dibu-cAMP

dibutyryl-cAMP

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this study.

Data accessibility

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (rgopalak@usc.edu) upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].Knopman DS, Amieva H, Petersen RC, Chételat G, Holtzman DM, Hyman BT, Nixon RA and Jones DT (2021). Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hardy J and Selkoe DJ (2002). The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kametani F and Hasegawa M (2018). Reconsideration of Amyloid Hypothesis and Tau Hypothesis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurosci 12, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rao CV, Asch AS, Carr DJJ and Yamada HY (2020). “Amyloid-beta accumulation cycle” as a prevention and/or therapy target for Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 19, e13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Edwards FA (2019). A Unifying Hypothesis for Alzheimer’s Disease: From Plaques to Neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci 42, 310–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sengupta U, Nilson AN and Kayed R (2016). The Role of Amyloid-β Oligomers in Toxicity, Propagation, and Immunotherapy. EBioMedicine 6, 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jarosz-Griffiths HH, Noble E, Rushworth JV and Hooper NM (2016). Amyloid-beta Receptors: The Good, the Bad, and the Prion Protein. J Biol Chem 291, 3174–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mroczko B, Groblewska M, Litman-Zawadzka A, Kornhuber J and Lewczuk P (2018). Cellular Receptors of Amyloid β Oligomers (AβOs) in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Popugaeva E, Pchitskaya E and Bezprozvanny I (2018). Dysregulation of Intracellular Calcium Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 29, 1176–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cheignon C, Tomas M, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Faller P, Hureau C and Collin F (2018). Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol 14, 450–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Reddy PH, Manczak M and Kandimalla R (2017). Mitochondria-targeted small molecule SS31: a potential candidate for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics 26, 1483–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cummings DM, Liu W, Portelius E, Bayram S, Yasvoina M, Ho SH, Smits H, Ali SS, Steinberg R, Pegasiou CM, James OT, Matarin M, Richardson JC, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Hardy JA, Salih DA and Edwards FA (2015). First effects of rising amyloid-β in transgenic mouse brain: synaptic transmission and gene expression. Brain 138, 1992–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Smith LM, Kostylev MA, Lee S and Strittmatter SM (2019). Systematic and standardized comparison of reported amyloid-β receptors for sufficiency, affinity, and Alzheimer’s disease relevance. J Biol Chem 294, 6042–6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pinnock EC, Jovanovic K, Pinto MG, Ferreira E, Dias Bda C, Penny C, Knackmuss S, Reusch U, Little M, Schatzl HM and Weiss SF (2016). LRP/LR Antibody Mediated Rescuing of Amyloid-beta-Induced Cytotoxicity is Dependent on PrPc in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 49, 645–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Da Costa Dias B, Jovanovic K, Gonsalves D, Moodley K, Reusch U, Knackmuss S, Weinberg MS, Little M and Weiss SF (2014). The 37kDa/67kDa laminin receptor acts as a receptor for Abeta42 internalization. Sci Rep 4, 5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].DiGiacomo V and Meruelo D (2016). Looking into laminin receptor: critical discussion regarding the non-integrin 37/67-kDa laminin receptor/RPSA protein. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 91, 288–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kumazoe M, Sugihara K, Tsukamoto S, Huang Y, Tsurudome Y, Suzuki T, Suemasu Y, Ueda N, Yamashita S, Kim Y, Yamada K and Tachibana H (2013). 67-kDa laminin receptor increases cGMP to induce cancer-selective apoptosis. J Clin Invest 25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gundimeda U, McNeill TH, Elhiani AA, Schiffman JE, Hinton DR and Gopalakrishna R (2012). Green tea polyphenols precondition against cell death induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation via stimulation of laminin receptor, generation of reactive oxygen species, and activation of protein kinase Cepsilon. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287, 34694–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gopalakrishna R, Gundimeda U, Zhou S, Bui H, Davis A, McNeill T and Mack W (2018). Laminin-1 induces endocytosis of 67KDa laminin receptor and protects Neuroscreen-1 cells against death induced by serum withdrawal. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 495, 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Parvathenani LK, Calandra V, Roberts SB and Posmantur R (2000). cAMP delays beta-amyloid (25–35) induced cell death in rat cortical neurons. Neuroreport 11, 2293–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Takei N, Skoglösa Y and Lindholm D (1998). Neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) on mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci Res 54, 698–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Solés-Tarrés I, Cabezas-Llobet N, Vaudry D and Xifró X (2020). Protective Effects of Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase-Activating Polypeptide and Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Against Cognitive Decline in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Onoue S, Endo K, Ohshima K, Yajima T and Kashimoto K (2002). The neuropeptide PACAP attenuates beta-amyloid (1–42)-induced toxicity in PC12 cells. Peptides 23, 1471–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Han P, Caselli RJ, Baxter L, Serrano G, Yin J, Beach TG, Reiman EM and Shi J (2015). Association of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide with cognitive decline in mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 72, 333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rat D, Schmitt U, Tippmann F, Dewachter I, Theunis C, Wieczerzak E, Postina R, van Leuven F, Fahrenholz F and Kojro E (2011). Neuropeptide pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) slows down Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in amyloid precursor protein-transgenic mice. Faseb j 25, 3208–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Eiden LE, Samal B, Gerdin MJ, Mustafa T, Vaudry D and Stroth N (2008). Discovery of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-regulated genes through microarray analyses in cell culture and in vivo. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1144, 6–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].May V, Lutz E, MacKenzie C, Schutz KC, Dozark K and Braas KM (2010). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)/PAC1HOP1 receptor activation coordinates multiple neurotrophic signaling pathways: Akt activation through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma and vesicle endocytosis for neuronal survival. J Biol Chem 285, 9749–9761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gunther EC, Smith LM, Kostylev MA, Cox TO, Kaufman AC, Lee S, Folta-Stogniew E, Maynard GD, Um JW, Stagi M, Heiss JK, Stoner A, Noble GP, Takahashi H, Haas LT, Schneekloth JS, Merkel J, Teran C, Naderi ZK, Supattapone S and Strittmatter SM (2019). Rescue of Transgenic Alzheimer’s Pathophysiology by Polymeric Cellular Prion Protein Antagonists. Cell Rep 26, 145–158.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Roberts BR, Lind M, Wagen AZ, Rembach A, Frugier T, Li QX, Ryan TM, McLean CA, Doecke JD, Rowe CC, Villemagne VL and Masters CL (2017). Biochemically-defined pools of amyloid-β in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with amyloid PET. Brain 140, 1486–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zheng Y, Wang J, Li D, Guo M, Zhen M and Chang Q (2016). Wnt / ß-Catenin Signaling Pathway Against Aβ Toxicity in PC12 Cells. Neurosignals 24, 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jang JH, Aruoma OI, Jen LS, Chung HY and Surh YJ (2004). Ergothioneine rescues PC12 cells from beta-amyloid-induced apoptotic death. Free Radic Biol Med 36, 288–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tong Y, Bai L, Gong R, Chuan J, Duan X and Zhu Y (2018). Shikonin Protects PC12 Cells Against β-amyloid Peptide-Induced Cell Injury Through Antioxidant and Antiapoptotic Activities. Sci Rep 8, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Brown DR, Schmidt B and Kretzschmar HA (1997). Effects of oxidative stress on prion protein expression in PC12 cells. Int J Dev Neurosci 15, 961–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wägele J, De Sio S, Voigt B, Balbach J and Ott M (2019). How Fluorescent Tags Modify Oligomer Size Distributions of the Alzheimer Peptide. Biophysical Journal 116, 227–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vaudry D, Rousselle C, Basille M, Falluel-Morel A, Pamantung TF, Fontaine M, Fournier A, Vaudry H and Gonzalez BJ (2002). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide protects rat cerebellar granule neurons against ethanol-induced apoptotic cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 6398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Emery AC, Eiden MV and Eiden LE (2013). A new site and mechanism of action for the widely used adenylate cyclase inhibitor SQ22,536. Mol Pharmacol 83, 95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bethea CL (1990). Effect of vasoactive intestinal peptide on monkey prolactin secretion and cyclic AMP in culture: interaction with estradiol and phenol red. Neuroendocrinology 51, 576–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Berthois Y, Katzenellenbogen JA and Katzenellenbogen BS (1986). Phenol red in tissue culture media is a weak estrogen: implications concerning the study of estrogen-responsive cells in culture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 83, 2496–2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Picón-Pagès P, Bonet J, García-García J, Garcia-Buendia J, Gutierrez D, Valle J, Gómez-Casuso CES, Sidelkivska V, Alvarez A, Perálvarez-Marín A, Suades A, Fernàndez-Busquets X, Andreu D, Vicente R, Oliva B and Muñoz FJ (2019). Human Albumin Impairs Amyloid β-peptide Fibrillation Through its C-terminus: From docking Modeling to Protection Against Neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 17, 963–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cao G, Russell RM, Lischner N and Prior RL (1998). Serum antioxidant capacity is increased by consumption of strawberries, spinach, red wine or vitamin C in elderly women. J Nutr 128, 2383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lewinska A, Wnuk M, Slota E and Bartosz G (2007). Total anti-oxidant capacity of cell culture media. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34, 781–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Edwards MA, Loxley RA, Williams AJ, Connor M and Phillips JK (2007). Lack of functional expression of NMDA receptors in PC12 cells. Neurotoxicology 28, 876–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sudo M, Tsuzuki K, Okado H, Miwa A and Ozawa S (1997). Adenovirus-mediated expression of AMPA-type glutamate receptor channels in PC12 cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 50, 91–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gopalakrishna R, Mades A, Oh A, Zhu A, Nguyen J, Lin C, Kindy MS and Mack WJ (2020). Cyclic-AMP induces Nogo-A receptor NgR1 internalization and inhibits Nogo-A-mediated collapse of growth cone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 523, 678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lee B, Cao R, Choi YS, Cho HY, Rhee AD, Hah CK, Hoyt KR and Obrietan K (2009). The CREB/CRE transcriptional pathway: protection against oxidative stress-mediated neuronal cell death. J Neurochem 108, 1251–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Vitolo OV, Sant’Angelo A, Costanzo V, Battaglia F, Arancio O and Shelanski M (2002). Amyloid beta -peptide inhibition of the PKA/CREB pathway and long-term potentiation: reversibility by drugs that enhance cAMP signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 13217–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kelly MP (2018). Cyclic nucleotide signaling changes associated with normal aging and age-related diseases of the brain. Cell Signal 42, 281–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bornfeldt KE (2006). A single second messenger: several possible cellular responses depending on distinct subcellular pools. Circ Res 99, 790–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sanders O and Rajagopal L (2020). Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials and Epidemiology with a Mechanistic Rationale. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 4, 185–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Song XJ, Wang ZB, Gan Q and Walters ET (2006). cAMP and cGMP contribute to sensory neuron hyperexcitability and hyperalgesia in rats with dorsal root ganglia compression. J Neurophysiol 95, 479–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (rgopalak@usc.edu) upon reasonable request.