Abstract

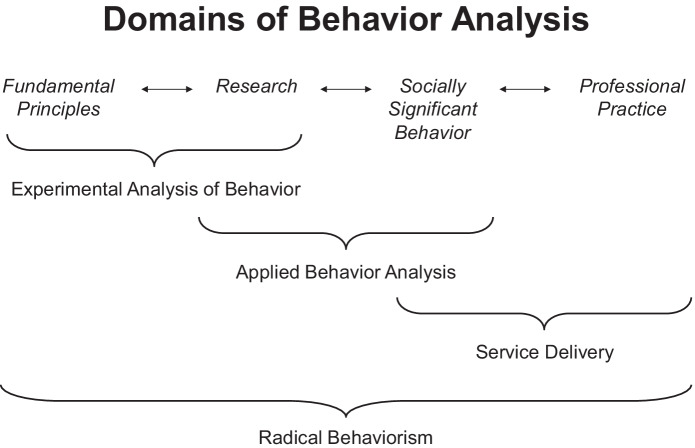

This article outlines a graduate-level course on the philosophical, conceptual, and historical (PCH) foundations of radical behaviorism, which is the philosophy of science that underlies behavior analysis. As described, the course is for a 15-week semester, and is organized into weekly units. The units in the first half of the course are concerned with the influences of other viewpoints in the history of psychology on the development of behavior analysis and radical behaviorism. The units in the second half are concerned with the PCH foundations of eight basic dimensions of radical behaviorism. Throughout, a course examining the foundations of radical behaviorism is seen as compatible with related courses in the other three domains of behavior analysis—the experimental analysis of behavior, applied behavior analysis, and service delivery—and as integral to the education of all behavior analysts.

Keywords: B. F. Skinner, mentalism, methodological behaviorism, operationism, philosophy of science, pragmatism, private behavioral events, radical behaviorism, selectionism

This article outlines a graduate-level course in the philosophical, conceptual, and historical (PCH) foundations of B. F. Skinner’s radical behaviorism. Radical behaviorism is the distinctive philosophy of science that underlies behavior analysis, which is Skinner’s approach to a science of behavior. The aim of this science is to analyze and explain an organism’s interactions with the environment. The analysis and explanations lead in turn to prediction and control of behavioral events, with the attendant benefit of enhancing human welfare.

For at least humans, some of these interactions go well beyond overt muscular movements to include such matters as thinking, language, emotions, and problem solving. Also for at least humans, some of these interactions may be covert and raise both technical and conceptual issues pertaining to how a science of behavior may include covert interactions. Finally, the adjective “radical” implies a thoroughgoing behavioral approach to analyzing and explaining these interactions. Thus, the adjective does not imply a fanatical or extreme commitment to analyses and explanations that are expressed exclusively in terms of observable variables and relations. How then might a course in radical behaviorism be arranged to provide a PCH foundation for the analysis and explanation of the full range of these interactions?

The course suggested in this article is described in terms of a 15-week semester, organized around weekly units of study. Classes for the units might meet once a week for 2.5 hr, or three times a week for 50 min each time, or according to some other plan consistent with the practices of the institution or agency that houses the course. Appropriate adjustments could be made for campuses with 10-week terms. Short breaks would be scheduled every hour when the class meets for 2.5 hr.

Units in the first half of the course examine the influence on behavior analysis and radical behaviorism of such other viewpoints in the history of psychology as functionalism, post-Darwinian animal/comparative psychology, reflex physiology, and pragmatic philosophy. In particular, behavior analysis and radical behaviorism are distinguished from the classical S => R behaviorism of the first quarter of the 20th century, the mediational S => O => R neobehaviorism that began in the second quarter of 20th century and continues in contemporary psychology, and a methodological behaviorism that relies on a traditional interpretation of operationism. By way of contrast, the traditional interpretation is based on a symbolic-referential rather than operant-behavioral view of verbal behavior and a coherence rather than pragmatic criterion of truth, about which more is said later. Units in the second half of the course seek to clarify and improve the understanding of the PCH foundations of radical behaviorism by examining eight basic dimensions of radical behaviorism.

Some Practical Considerations

One practical consideration regarding such a course is when it would be taught during a student’s program of study. The not-so-simple answer is “It depends.” For example, it depends on the staffing of the academic department in which the course is housed, the structure of its program in behavior analysis, as well as the entering repertoires of the students. In the present author’s experience, a course such as the present one contributes more to the development of students’ repertoires when it comes late rather than early in their program of study. Many of the curriculum topics with which such a course is concerned arise in previous courses or discussions, and warrant further examination. Particularly relevant is a course in verbal behavior that includes objectives dealing with scientific verbal behavior. However, time and resources are not always available in these other courses to work through many of the topics that are of interest or value to the students. Having the course later in students’ academic programs allows the repertoires they have developed with other instructors in other courses to be brought to bear on PCH topics to the best intellectual advantage for the students.

A further practical consideration is the format in which such a course might be offered. The present course is suggested for a seminar rather than lecture format. According to this format, articles and chapters from a reading list are assigned for each seminar meeting. Students then analyze and evaluate the programmatic contributions of the readings during seminar meetings. One feature of the suggested course is that the analysis and evaluation is largely student-led. Such a format is by no means unique to the present author, who first learned of it from ABAI colleagues in the 1980s. Its origin may lie in Gainesville, Florida. In regard to course format, the wording below or its equivalent might be usefully included in the syllabus for the course:

Readings (chapters, articles) will be assigned for class discussion. The readings will be available electronically as pdf. Students will be organized into groups (e.g., Red, White, Blue) for group activities and projects.

Discussion questions:

Students from one group will be assigned as discussion leaders for a given hour and reading assignment. Other students should submit one discussion question for the reading assignment for a given hour via email. The discussion questions will serve as the basis for the review and discussion of the reading assignment. The questions should be submitted by 20:00 of the previous day. The purpose of the questions is to facilitate discussion and analysis of the reading material. Hence, the questions should concern clarification, extension, implication, validity, comparison with other sources, etc. The question may be drawn directly from the reading material assigned for that hour, or it may relate to other material on the same topic with which you are familiar (e.g., prior classes, other articles or books). Past experience suggests that such questions as, "What do you think of the author's discussion of X?" are not particularly useful. Remember, the questions are not designed to be tests of trivia about the reading assignment. Rather, they are supposed to facilitate discussion, analysis, clarification, and understanding. Preambles to your questions are encouraged if you wish to give some context to your question. Other substantive comments sent by email are perfectly appropriate. Finally, the instructor is the author of many of the readings. Students should nevertheless not be reluctant to comment critically on these readings if students find the readings lack merit. If students are uncomfortable about commenting critically, one possibility is to refer to the author in the third person. I will forward comments to the author on your behalf.

Discussion leaders:

Discussion leaders do not have to answer the questions themselves. Their responsibility is to bring the collective wisdom of the class to bear on the question and possible answers. Discussion leaders also do not need to address every question that is submitted. Rather, they are at liberty to select questions and indeed the order in which questions are addressed according to their professional judgment.

A further student activity is as follows. The first portion (e.g., 20 min) of a given seminar meeting might be devoted to a review of the analysis and evaluation of the readings from the immediately previous seminar meeting. This review would be composed and led by the student group that led the previous seminar meeting. In this regard, the wording below or its equivalent might be usefully included in the syllabus for the course:

The first portion of the seminar meeting on a given day should consist of a short (3-slide) PowerPoint presentation, based on that group’s evaluation of how well the reading and discussion in the prior meeting addressed one of the objectives from the syllabus. The slides may evaluate in a collegial and scholarly way what was actually discussed, or what the group thinks should have been discussed but wasn’t.

A final student activity is an oral presentation at the end of the course. The presentation would be a collaborative effort of each group. This presentation would address a topic of interest, in the manner of a convention presentation. In this regard, the wording below or its equivalent might be usefully included in the syllabus for the course. The wording also suggests topics and readings on which the presentation might be based. Groups can make presentations based on alternative topics and readings with the approval of the instructor.

Each group should choose one or more chapters or articles that are thematically related to each other and prepare a 20-min PowerPoint presentation (about 20 slides) on that topic. The presentation should resemble a convention presentation. The chapter or article could probably support a much longer presentation. Students will need to select what topics to emphasize from each reading assignment. Some topics may have to be omitted entirely, and others may have to be condensed drastically. Begin by deciding on your objective: What would you like an audience to know about the chapter or article by the time the presentation has concluded? Note: If presenters can’t state this objective at the beginning, if only for themselves, how can an audience be expected to know something at the end? Then work backward to decide how you want to get to that point. Be sure you are able to identify how each slide contributes to moving along the path. In turn, be sure you are able to identify how each element of a slide contributes to the function of that slide.

Suggestions: correct spelling, 24-point type, 8 lines of text per slide, only judicious and nondistracting use of images and animation, avoid reading text on a slide to the audience

Readings are available electronically as pdf.

Reading 1: Palmer, D. (1991). A behavioral interpretation of memory. In L. J. Hayes & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues on verbal behavior (pp. 261–279). Context Press.

Reading 2: Schlinger, H. D. (2003). The myth of intelligence. Psychological Record, 53, 15–32.

Reading 3: Moore, J. (2002). Some thoughts on the relation between behavioral neuroscience and behavior analysis. Psychological Record, 52, 261–280.

Reading 4: Moore, J. (1994). On introspections and verbal reports. In S. Hayes, L. Hayes, M. Sato, & K. Ono (Eds.), Behavior analysis of language and cognition (pp. 281–299). Context.

Reading 5: Skinner, B. F. Why I am not a cognitive psychologist. (reprinted)

Reading 6: Skinner, B. F. The origins of cognitive thought. (reprinted)

Reading 7: Skinner, B. F. Thinking. Chapter 6 from Technology of Teaching and Chapter 19 from Verbal Behavior (reprinted)

Reading 8: Skinner, B. F. Cognitive science and behaviorism. (reprinted)

A final consideration concerns resources for the suggested course. The present author’s experience is that it is useful is for an instructor to make digital copies of the reading assignments and post them on a campus academic web site such as a learning management system. The reason is that sometimes journals or books are not readily available to students, and the possibility that students will be shortchanged because they do not have ready access to course material does not seem appropriate. Likewise, electronic media are involved in email exchanges and class presentations in the suggested course. Instructors may need to adjust their practices if students are not familiar with or do not have either personal or campus-based access to these forms of electronic media, even though such limitations may be rare.

Evaluation of Student Performance

A necessary component of an academic course is evaluation of student performance. For the suggested course, the wording below or its equivalent might be usefully included in the syllabus regarding student evaluation:

The evaluation of student performance in the course will be based on quality of discussion questions, quality of contribution to discussion during seminar meetings, quality of group ppt presentation during seminar meetings, and quality of final project.

Instructors are free to weigh each activity equally at 25%, or weigh one activity more heavily than another.

What Then is Radical Behaviorism?

As Skinner (1964) put it, “Behaviorism, with an accent on the last syllable, is not the scientific study of behavior but a philosophy of science concerned with the subject matter and methods of psychology” (p. 221). Skinner’s interest in the PCH foundations of behaviorism began during his graduate school days. In this regard, Skinner (1979) described how he took courses and subscribed to journals in the history and philosophy of science when he was a graduate student. Among the writings he noted as particularly important in his studies were those of the physicist Ernst Mach (1838–1916), the philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), the mathematician Henri Poincaré (1854–1912), and the physicist Percy Bridgman (1882–1961). In another autobiographical piece, Skinner (1978) described his intellectual interest in the PCH foundations of behaviorism by saying that “I came to behaviorism, as I have said, because of its bearing on epistemology, and I have not been disappointed” (p. 124).

Figure 1 proposes one way of understanding the four principal domains of contemporary behavior analysis:

Fig. 1.

Note. The figure is adapted from Moore (2008), Figure 1.1, p. 3, and is reproduced with permission. CFRB abbreviates Conceptual Foundations of Radical Behaviorism

The top portion of Figure 1 presents four core domains of behavior analysis: fundamental principles, research, socially significant behavior, and professional practice in fee for service or comparable financial arrangements. Each of the three principal domains of behavior analysis then emphasizes a pair of these concerns.

The domain of the experimental analysis of behavior emphasizes conducting research into fundamental principles, such as those concerning reinforcement, aversive control, stimulus control, and so on. A goal of this domain is to advance and disseminate knowledge, often at an abstract level, regarding these principles.

The domain of applied behavior analysis emphasizes research concerning behavior in the world outside the laboratory. In clinical settings, the research might investigate how to replace excessive, maladaptive forms of socially significant behavior with more adaptive forms, or how to strengthen currently weak but nevertheless adaptive forms of behavior. In nonclinical settings, the research might investigate instructional techniques in the classroom or communication practices in the workplace. A goal of this domain is to identify and disseminate improvements in techniques that enhance the quality of life for individuals and populations, as well as the functioning of social and commercial institutions.

The domain of professional practice emphasizes enhancing various forms of behavior in both clinical and nonclinical settings outside the laboratory in fee for service or analogous arrangements. A goal of this domain is to employ “best practices” identified through applied behavior analysis or personal experience to actually bring about desired changes. Worth noting is that on the present view, the designation of applied behavior analysis may be usefully distinguished from that of service delivery, in order to preserve the centrality of research endeavors in applied behavior analysis and fee for service arrangements in professional practice (e.g., Moore & Cooper, 2003).

The domain of radical behaviorism emphasizes the PCH foundations of the three other domains. A goal of this domain is to clarify and improve an understanding of the rationale, methods, and ethics of the techniques of research and application that are integral to the experimental analysis of behavior, applied behavior analysis, and service delivery, thereby improving the effectiveness of behavior analysis as the science of behavior and the application of that science.

Although Figure 1 might be interpreted to mean that the four domains are discrete silos, a more useful view is that the domains are overlapping modes on a continuum of activities (Moore & Cooper, 2003). After all, behavior analysis is what behavior analysts do, and during their careers behavior analysts often work in more than one of these domains, successively or even simultaneously. The result is that behavior analysts may naturally have overlapping concerns and engage in overlapping activities across these domains. For example, behavior analysts who deliver services make some of the same types of data-based judgments as behavior analysts who conduct research, even though behavior analysts who deliver services do not formally compare behavior analytic procedures with traditional procedures, conduct formal component analyses, or disseminate their results in peer-reviewed articles in scholarly journals.

Finally, such activities as translational research are carried out in ways that cut across the sometimes fuzzy distinctions outlined above. Translational research examines how one or more of the abstract findings of basic research may be applied in concrete ways to solve particular problems, thereby enhancing human welfare. The important point is that an academic course dealing with the PCH foundations of radical behaviorism may meaningfully contribute in many respects to student repertoires regarding the relations among radical behaviorism and the other domains of behavior analysis, all to the benefit of a science of behavior and its application in the world outside the laboratory.

Instructional design of any sort specifies not only input, such as readings and assignments that might be employed in a course, but also output, such as the terminal behavior of students with respect to the objectives of the course. Skinner’s (1968) words are relevant here: “The first step in designing instruction is to define the terminal behavior. What is the student to do as a result of being taught?” (pp. 199–200). The present outline suggests readings as the input for a unit. The description of a unit also includes one or more representative objectives as the output stated in large-scale terms. Instructors may surely modify both the readings and objectives of the present outline according to their own goals, backgrounds, level of the course, and entering repertoires of the students.

The First Half of the Suggested Course: Historical Foundations of Radical Behaviorism

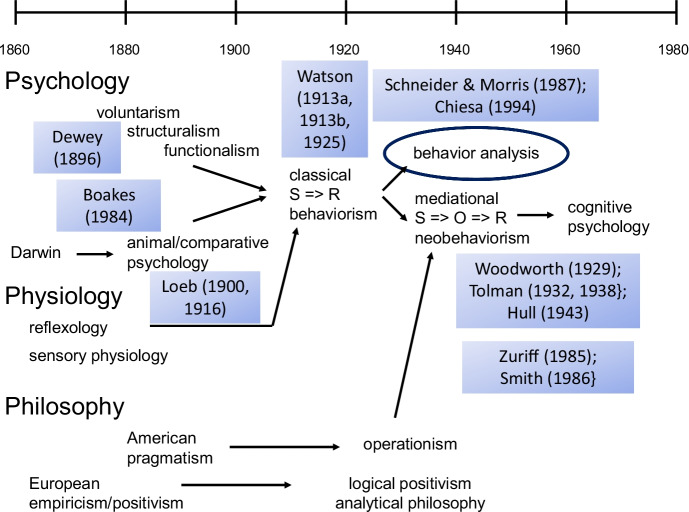

As noted earlier, the first half of the suggested course addresses how various viewpoints in the history of psychology influenced the PCH foundations of behavior analysis and radical behaviorism. Figure 2 presents one way to understand the influence of these viewpoints. The figure presents a timeline of roughly 100 years, from roughly the third quarter of the 19th century to the third quarter of the 20th century. During this period, trends in psychology, physiology, and philosophy are noted. Some of these trends then combine over time in various ways. During this period and for these trends—singly as well as combined—references are proposed that would be useful in the suggested course.

Fig. 2.

Note. The figure is modified from Moore (2008), Figure 3.1, p. 51, and is reproduced with permission. CFRB abbreviates Conceptual Foundations of Radical Behaviorism

Traditional histories of psychology sometimes suggest that psychology began as a formal, independent discipline with Wilhelm Wundt’s voluntarism in Leipzig, Germany, in 1879. Of course, this historical story is skewed. In neolithic times dogs and cats were domesticated, and later horses were recruited to help in farming. The behavioral techniques used in these practices were well-established thousands of years before 1879, but few records of those techniques are available. It may be presumed that those techniques are an important chapter in the history of psychology writ large, with a subject matter and methods pertaining to behavior rather than mental life. Suffice it to say that concerns about how to raise children to engage in ethical behavior and increasing knowledge of both sensory and reflex physiology were also of intense interest in the middle-to-late 1800s. Perhaps more useful is to cite Wundt as providing a unifying theme that imparted some order to psychology, so that others would recognize it as a scientific discipline. Of course, we now say that this theme was derived from the social-cultural assumptions of Wundt’s time about what a science of psychology should be about: mental life, rather than behavior in relation to environmental circumstances.

In any case, E. B. Titchener (1867–1927) studied with Wundt and imported the new psychology to the United States, albeit with his own modifications. Titchener’s approach is known as structuralism. Structuralism advertised itself as an objective, scientific approach to psychology. Its goal was to understand human mental life by making inferences about the structure and contents of consciousness—the quality, intensity, duration, and so on, of sensations, images, and feelings—on the basis of such methods as introspection, reaction times, and rating scales. Wundt had argued that once these mental phenomena were understood, the way was open to extend this understanding to broader issues, such as the organization of society. Structuralism claimed its scientific rigor in virtue of the extensive training it required of subjects. For example, many training trials were thought to be necessary to prevent subjects from committing the “stimulus error” by evaluating a stimulus instead of more properly describing their experience of the stimulus. An objective here for a unit is for students to describe the characteristics of American structuralism under Titchener.

However, as the 19th century drew to a close, U.S. culture sought practical applications of its sciences in order to enhance domestic educational systems and industrial capacity. Contributions to “efficiency” were particularly important. The “ivory tower” knowledge claims of structuralism yielded few if any practical applications, perhaps deliberately so. A distinctly American version of psychology called functionalism then arose in contrast to structuralism. Functionalism emphasized concrete, pragmatic implications of psychology in the world of human affairs. Mental life was relevant in functionalism, but primarily for its adaptive contributions, rather than its structure. Functionalism also adopted a developmental perspective. As a result, functionalism was particularly influential when it came to educational policy and practices. For example, suppose structuralists were concerned with the contents and structure of a child’s consciousness at a particular age, such as whether one mental process was higher or lower in consciousness than another process. Functionalists might be interested in the same question, but for a practical reason: Given the structure and content of consciousness for children of age X, how should instruction in a classroom for children of that age and stage of development be carried out to take advantage of that mental structure, so that the child learns more efficiently? Likewise, Dewey’s (1896) classic article criticized the traditional interpretation of the reflex arc concept in psychology for emphasizing structural, physiological concerns. Physiology emphasized “How?” questions at the expense of “Why?” questions. Although functionalism agreed that it was perfectly all right to be concerned with the underlying physiology of the reflex, a true science of behavior also had to do more. Dewey especially emphasized functional concerns, such as how reflexes, or behavior more generally, contributed to adaptation. As a result, a desired instructional technique according to functionalists was to have assignments and exercises in classroom instruction map closely on what is required outside the classroom, in society at large. An objective here is for students to compare and contrast the characteristics of American functionalism with those of structuralism.

Charles Darwin (1809–1882) published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (Darwin, 1859) shortly after the middle of the 19th century. In this landmark work Darwin proposed that species descend with modification from common ancestors, rather than by being created. He further proposed that life forms possessed a certain continuity as a result of descent with modification. However, that continuity branched significantly over time, rather than developed linearly on a single track. Darwin’s book led to a comparative psychology that implicitly assumed various intellectual processes in humans were mental, then sought to reveal evidence of those mental processes—albeit as lower order approximations—in nonhumans. Thus, a technology based on “objective inference” developed for conducting research and gathering data in order to draw conclusions about the evidence in nonhumans for such mental processes as insight, problem solving, and even consciousness. Such a technology might involve such “objective” measures as trials to criterion or percent correct on test trials. Objective inference may be contrasted with the “subjective inference” based on introspection or other forms of data such as found in structuralism that did not meaningfully apply to nonhumans. Indeed, for functionalism the whole structuralist approach was questionable. Caution was urged throughout to not explain a given observation in terms of a mental process when it could just as well be explained in terms of a nonmental process. Many experimental procedures with nonhumans involved delayed responses, memory tasks, and insight problems, such as those involving detours in mazes. George John Romanes (1848–1894), Leonard Trelawney Hobhouse (1864–1929), and Conwy Lloyd Morgan (1852–1936) are commonly cited as major figures in this tradition. The American Edward L. Thorndike (1874–1949) is sometimes also included as a figure in the tradition, although his career spanned a broad range of interests and in general focused on explanations that didn’t involve appeals to mental processes in the same way as did the others. A possible exception is Thorndike’s appeal to the strengthening of a response through its “satisfying” consequences and the weakening of a response through its “annoying” consequences, although Thorndike provided independent criteria for determining whether a consequence was satisfying or annoying. In any case, Boakes (1984) provides a superb review of this field. An objective here is for students to describe the procedure, results, and implications of an example of this post-Darwinian research in comparative psychology.

All along, researchers in reflex physiology were seeking to advance their understanding of the physiological processes involved in behaving. For example, Descartes’s early modern ideas were that there were two broad categories of behavior. The first category was when a boy withdraws his hand rapidly after contact with fire. The second was human voluntary behavior. In the case of voluntary behavior, the soul caused perturbations in the pineal gland. In turn, these perturbations agitated animal spirits and caused them to move inside tubes in our bodies that were connected to our muscles, resulting in the behavior of interest. Both nonhumans and humans engaged in the first category, but only humans engaged in the second. After all, humans were the only species with a soul. By the first quarter of the 20th century, physiologists had set aside Descartes’s fanciful notions and shown that well-recognized physical-chemical processes were sufficient to explain the mechanics that underlay any form of behavior (“reflexology”). Loeb (1900, 1916) illustrates this influence through his analysis of tropisms in response to “fields of force.” Worth noting as an aside is that the first half of Skinner’s dissertation in 1931 traced the history of some of the work analyzing reflexes, where a reflex was defined simply as a response that was correlated with prevailing environmental circumstances (see Skinner, 1972, pp. 429–457). Comparable influences had developed in sensory physiology in the 19th century, for example, in the work of Herman Helmholz (1821–1894). As with post-Darwinian comparative psychology, the objective here is for students to describe the procedure, results, and implications of an example of this 19th-century research on reflex physiology, particularly regarding its emerging natural science orientation.

Finally, the influence of objective, empirical orientations in philosophy may be noted. Europe had its longstanding traditions of empiricism and positivism (e.g., John Locke, David Hume, August Comte, John Stuart Mill), and the United States had its pragmatic tradition, for example, as found in functionalism (e.g., Dewey, 1896). Again, the orientations in the United States were more concerned with such practical matters as adaptation than with promoting abstract metaphysical systems with elements of an uncertain provenance and ontology. In any case, the empirical and emerging pragmatic orientations in philosophy resonated with many scientists of the time. An objective here is for students to describe the influence of these pragmatic philosophical orientations on the development of scientific thought and especially methods during this era.

The first half of the course suggests that the four trends above—(1) functionalism with its developmental and evolutionary viewpoint emphasizing adaptation; (2) animal/comparative psychology with its methods based on objective inference; (3) physiological research with its emphasis on explanatory modes found in natural science; and (4) a pragmatic philosophy aligned with functionalism that emphasized objectivity and empiricism—paved the way for the early form of behaviorism. This early form may be usefully described as classical S => R behaviorism, and for present purposes John B. Watson may be usefully identified as a representative. For Watson (e.g., 1913a, 1913b), psychology was a natural science whose theoretical goal was the prediction and control of behavior. In today’s words we might say he argued that behavior in relation to the environment was a subject matter in its own right. However, unlike his contemporary Thorndike, Watson found no explanatory role for the consequences of behavior. Rather, Watson argued that explanations should identify the antecedent circumstances that “called out” the behavior. Watson further argued that explanations of some so-called mental phenomena could be provided in purely behavioral terms, and the full range of human activities could be embraced, from overt movements to language to images. References here are selected portions of Watson’s (1925) full-length book Behaviorism and Moore (2017).

An informal review of American psychology in first quarter of 20th century suggests that in keeping with the rise of the S => R reflex model, classical behaviorism became an influential analytic and explanatory model. Again, an important feature of the reflex model was that behavior should be understood through its relation to antecedent stimuli. Those stimuli were usually but not always observable. For example, Watson (1925) routinely appealed to kinesthetic and interoceptive forms of stimulation in his analyses and explanations of behavior. In addition, his account of thinking as subvocal speech is well-known, though mistakenly disparaged because he explicitly acknowledged that thinking was a form of behaving that can also occur without words (e.g., pp. 213ff.).

Despite the virtues that many researchers and theorists claimed for the S => R model, we can also note that there was significant debate in the first quarter of the 20th century as to whether the model was adequate as a general model for all forms of behavior. For instance, Holt (1914) argued that much behavior seemed to have a much greater spontaneity and flexibility than the S => R model seemed to allow. In addition, Holt argued that the sequential organization of behavior was difficult to explain in terms of the S => R model. In short, significant challenges then arose in the second quarter of the 20th century to the explanatory reliance on antecedent, observable stimuli. For example, Tolman (1932, 1938) argued that behavior was docile, purposive, and a means to an end, rather than evoked like beads on a chain by a sequence of stimuli. Thus, Tolman argued that when a rat learned to run a maze, the rat learned the floor plan or “cognitive map” of where the food was in the maze and how to get to there, rather than to take a series of steps punctuated with an occasional left or right turn.

These challenges to the S => R model led many researchers and theorists to insert intervening organismic [O] variables between the S and the R. These O variables were unobservable. As a result, they were inferred theoretical constructs, in contrast to observable independent and dependent variables. The function of these O variables was to mediate the relation between S and R. Here, mediation means that antecedent, observable circumstances trigger changes in the value or status of the unobservable intervening variable, and the value or status of the intervening variable, not the antecedent circumstances, then triggers the eventual observable response. Again, the organism is held to be in direct contact only with the intervening variable, not the antecedent circumstances. As a result, the explanation of behavior was held to focus more properly on the inferred properties, operating characteristics, and hence causal role of the intervening, mediating variable, rather than on a history of interaction with actual antecedent environmental circumstances. Indeed, attention to environmental circumstances was disparaged as a matter of mere performance, rather than a genuinely explanatory consideration. Woodworth (1929) was an early example of this general orientation, and Tolman’s (1932, 1938) purposive analysis vigorously championed the mediational point of view.

In regard to the foregoing, Tolman was on sabbatical leave in Europe in 1933 and 1934. While there, he met with a group of philosophers in Vienna known as logical positivists. The logical positivists argued for a rational reconstruction of scientific knowledge. For logical positivists, the semantics of knowledge claims were to be based on physicalism—the definition of all concepts in the language of physics. The syntax of knowledge claims was to be based on formal, symbolic logic and evaluated in truth-functional terms. The logical positivists argued that all sciences could be unified under the banner of their approach, and a new understanding of the remarkable accomplishments of physics in the first quarter of the 20th century, with its claims about atomic theory, quantum mechanics, and the solar system, was widely hailed as the chief success of their approach. In any case, through Tolman’s discussions with the logical positivists and such other theorists as Egon Brunswik (1903–1955), Tolman became well-acquainted with the new model of scientific epistemology that incorporated intervening theoretical constructs. Just as science involved observable dependent and independent variables, the argument was that so also did science involve unobservable theoretical terms.

After his European experiences, Tolman adapted the new model of scientific epistemology to his own style of theorizing as an alternative to the S => R model that relied on discrete, antecedent, and observable stimuli (e.g., Smith, 1986). The mediating variables to which he appealed were various acts, states, mechanisms, or processes, taken to be inside the organism in some sense but unobservable. Tolman’s argument was that they could nonetheless be inferred from the data. Therefore, claiming them as immanent determiners of behavior was perfectly well justified. Tolman (1938) was explicit when he endorsed a theoretical approach that appealed to intervening variables: “A theory, as I shall conceive it, is a set of ‘intervening variables.’ These to-be-inserted intervening variables are ‘constructs’ which we, the theorists, evolve as a useful way of breaking down into more manageable form the original complete . . . function” (p. 9). A suitable objective here is for students to describe the research background for one of Tolman’s intervening variables, then to compare the nature of Tolman’s explanation of behavior with Watson’s.

Other researchers and theorists quickly adopted the new approach that appealed to intervening, organismic variables that mediated the S => R relation, and the new approach soon became known as mediational S => O => R neobehaviorism. The prefix neo- was used to distinguish this newer form of behaviorism from such older forms as Watson’s classical S => R behaviorism that didn’t involve appeals to such intervening variables. The O in neobehaviorism was used to emphasize that the intervening, mediating variables were intrinsic in some sense to the psychological make-up of the organism, rather than an aspect of the observable environment.

However, debates then arose over how to answer some critical questions. For example, did the O variables actually exist inside a rat and change as it learned to run a maze? As an alternative, were the O variables simply logical devices whose benefit lay in how the properties attributed to them summarized data, contributed to parsimonious explanation, and contributed to system-building, all without regard to questions about their existence? Answers took all sides to such questions.

Still, an important question remained: Given that a mediating organismic variable was unobservable, how could researchers and theorists avoid a return to the ambiguities and excesses of structuralism, with its explanatory reliance on the unobservables of mental life? Indeed, Meyer (1922) had famously argued earlier that psychology should ignore unobservables entirely. However, the advent of operationism (Bridgman, 1928) meant that the validity of an unobservable organismic mediator could be established after all. According to operationism, the meaning of a term or concept was found in the publicly observable operations entailed in its measurement. Under the influence of operationism, an approach that appealed to intervening, mediating organismic variables then became particularly strong in experimental psychology. Two examples are (1) learning theory and (2) sensation and perception. Indeed, Tolman was a learning theorist, and he was joined in that field during the second quarter of the 20th century by Clark Hull (1884–1952) and Kenneth Spence (1907–1967). For example, Hull introduced his version of a systematic approach involving a mediational point of view in 1943 (Hull, 1943). In subsequent years, Spence also promoted the mediational approach through his extensive collaborations with Gustav Bergmann (1906–1987), one of the original logical positivist philosophers who had immigrated to the United States immediately prior to World War II and ultimately found an intellectual home with Spence at the University of Iowa. However, important to note is that many of the organismic variables in Tolman’s system tended to have an informal or unselfconsciously cognitive character to them. For example, his well-known “cognitive map” might reflect the floor plan of turns and alleys in a maze with 14 left–right choice points. In contrast, those in the Hull-Spence system tended to have a more formal, biological, or even mechanical character to them. For example, “drive” was defined in terms of hours of deprivation, and “habit strength” was defined in terms of the number of trials in which reinforcement was delivered. In turn, reinforcement consisted in drive reduction.

In the field of sensation and perception (“psychophysics”), S. S. Stevens (1906–1973) was an especially vocal advocate of operationism. Psychophysics was historically assumed to provide a window to the mind, although the actual operations of the mind were held to be ineffable. The avowed job of psychologists who worked in psychophysics, just as it was for those who worked in learning theory, was to conduct research and then describe relations in the data from that research. In this regard, psychologists could remain silent on any mental processes that might be inferred to underlie the data. By describing relations in the data quantitatively, rather than collecting introspective reports about the clarity or duration or quality of a sensation, researchers and theorists could argue that they were being scientific.

The model that emerged in psychophysics was that the objective stimulus, which was an observable independent variable that was measured with the instruments of physics, produced a subjective sensation. The subjective sensation was an inferred, intervening variable. In turn, the subjective sensation produced an objective verbal report about, say, the magnitude of the sensation. The verbal report was an observable dependent variable that reflected the influence of the mediating subjective sensation, rather than the objective stimulus itself. After all, doubling the magnitude of the objective stimulus didn’t always double the verbal report regarding the magnitude of the stimulus. Depending on the modality of the stimulus, the verbal report might be less than, equal to, or greater than the actual change in the magnitude of the stimulus. The mathematical relation between the objective stimulus and verbal report in a discrimination procedure was then taken to reveal the operating characteristics of the mind as it triggered the mediating, intervening variable of the subjective sensation. As a result, the mathematical relation constituted the necessary operational definition of an underlying mental process, and the whole enterprise could be taken to be scientific.

Still, the concept of “subjective sensation” reflected the longstanding concern with underlying processes in an unobservable, mental domain of existence that was apart from the observable, physical world, even though psychologists tried to avoid talking directly about any variable that wasn’t observable. Nevertheless, after operational definitions of intervening, mediating organismic variables became influential in psychophysics and learning theory, their influence then spread to the explanatory concepts deployed in such other branches of psychology as social psychology, personality theory, and even abnormal psychology.

In regard to all these developments, Skinner (1974) later wrote that “Most methodological behaviorists granted the existence of mental events while ruling them out of consideration” (p. 13). Skinner’s comment suggests that methodological behaviorists ruled mental events out of direct consideration, but permitted their indirect consideration with all their liabilities through the surrogacy of the traditional interpretation of operationism reviewed above. Worth noting is that elsewhere, Skinner (1945) wrote critically of the traditional interpretation of operationism advocated by his Harvard mentor E. G. Boring in collaboration with Skinner’s Harvard graduate student contemporary and soon-to-be Harvard colleague S. S. Stevens by saying

What happened instead was the operationism of Boring and Stevens. . . . It was an attempt to acknowledge some of the more powerful claims of behaviorism (which could no longer be denied) but at the same time to preserve the old explanatory fictions unharmed. (p. 292)

Skinner (1969) later commented disparagingly that “Stevens has applied Bridgman’s principle to psychology . . . to determine the extent to which we can deal with . . . [subjective, i.e., mental, events] scientifically” (p. 227). A passage from Kimble (1985) gives further evidence of a commitment to include mental concepts in a science of behavior through this traditional interpretation of operationism:

In a general way, the operational point of view did nothing more than insist that terms designating unobservables be defined in ways that relate them to observables. . . . In this way these concepts became intervening variables, ones that stand between observable antecedent conditions on the one hand and behavior on the other. . . . Obviously, there is nothing in this formula to exclude mentalistic concepts. In fact, the whole point of it is to admit unobservables. (p. 316)

Following from logical positivist philosophy in 1935 and 1936, the question arose in psychology as to whether the definition of a theoretical, intervening variable provided through operationism should be interpreted as exhaustive or partial. According to MacCorquodale and Meehl’s (1948) later treatment of this question, the meaning provided by an operational definition should be interpreted as exhaustive when the definition admitted no “surplus” meaning beyond the single use or application under consideration. In other words, “exhaustive” means that the one use or application exhausts or constitutes the full meaning of a theoretical term or construct, and there is no surplus or additional meaning that pertains to other circumstances. The construct was simply an aid to system building and theory construction, for example, by making observed relations more manageable in just the one, circumscribed case, and the construct had no other implications.

In contrast, the meaning provided by an operational definition should be interpreted as partial when the definition did admit surplus meaning, beyond the single use or application under consideration. In other words, “partial” means that any use or application gives only a part of the meaning of the term as a theoretical construct, and the construct might well be appropriately deployed in additional circumstances, with correspondingly additional meaning. An interpretation admitting surplus meaning was significant because it also implied that the mediating construct referred to something that did actually exist. How else could a construct be applied in more than one case if it didn’t actually exist? In effect, the meaning of the construct was derived from the referent, but an operational definition was not identical with the referent. Rather, the operational definition simply provided the observable evidence that justified the analytic or explanatory appeal to the construct. It was a surrogate that yielded agreement.

MacCorquodale and Meehl (1948) proposed a linguistic convention according to which a theoretical term would be called an “intervening variable” when its operational definition was interpreted as exhaustive, and it did not allow surplus meaning. In contrast, a theoretical term would be called a “hypothetical construct” when its operational definition was interpreted as partial, and it did allow surplus meaning. Either interpretation of the meaning of a construct was permissible, along with the commitment as to whether the term did or did not refer to something that actually existed. Although intervening variables were in a sense more logically rigorous, they also more tightly constrained theory construction and system building. As a result, hypothetical constructs came to be preferred in psychology, for example, because they offered more degrees of freedom in scientific theorizing (e.g., Tolman, 1949). An objective here is for students to describe how the intervening variable of “thirst” can be used to illustrate the distinction between exhaustive (i.e., an intervening variable interpretation) and partial operational definitions (i.e., a hypothetical construct interpretation) of mediating organismic variables.

Overall, the line of reasoning below summarizes the effect of these developments by the middle of the 20th century.

An S => R behaviorism based on antecedent, observable stimuli fell short of convincingly explaining the spontaneity and flexibility of behavior, as well as the sequential organization of behavior over time. These shortfalls led to the postulation of intervening but unobservable organismic variables [O]. These variables were inferred to have properties that allowed them to mediate the relation between S and R, thereby explaining the observed data. The result was an S => O => R explanatory framework called mediational neobehaviorism, in which the prefix neo- signified a newer, improved form of behaviorism than the older, classical S => R behaviorism such as Watson advocated.

These mediating O variables were then given the status of theoretical constructs under the influence of logical positivist philosophy.

The theoretical constructs were then operationally defined, where the definition could be interpreted as either exhaustive or partial. The result was a methodological rather than a genuine behaviorism, in that an operational definition in terms of observables was assumed to justify the appeal to underlying mental processes as “theoretical” by creating agreement.

Exhaustive definitions admitted no surplus meaning, defined as explanatory application restricted to only a single case. This one case exhausted the meaning of the construct. This interpretation of theoretical constructs was called the intervening variable interpretation.

In contrast, partial definitions admitted surplus meaning, defined as explanatory application in more than one case. Any one case provided only part of the meaning of the construct, and other explanatory applications provided further meanings. This interpretation of theoretical constructs was called the hypothetical construct interpretation.

The hypothetical construct interpretation led in turn to the reifying assumption that the mediating variable so interpreted must actually exist as mental-cognitive phenomenon for it to be applied in more than one case.

Nevertheless, the operational approach, even with an intervening variable rather than hypothetical construct interpretation of the meaning that the operational approach provided, was taken to yield agreement. Operationism was then taken to justify this entire method of doing science by making it a scientifically respectable, “theoretical” way to account for the behavior of both the subject who participates in the experiment and the concepts a scientist uses to explain that behavior.

The hypothetical construct interpretation came to be favored among researchers and theorists because of its parsimony and because it afforded more degrees of freedom in theory development and system building.

Worth noting is that throughout this whole period—roughly the second quarter and early third quarter of the 20th century, traditional researchers and theorists implicitly maintained their commitment to the notion of antecedent, mechanical causation, much as in classical S => R behaviorism (Chiesa, 1994). However, those antecedent causes were not necessarily observable stimuli, but rather the intervening O variables—the inferred mediating acts, states, etc. In any case, the traditional interpretation of operationism was presumed to validate the entire explanatory project, and the underlying symbolic, referential conception of verbal behavior on which the traditional interpretation of operationism was based was widely accepted.

In a series of articles that began in the 1930s, Skinner (e.g., 1935a, 1935b) vehemently opposed both the style and substance of this entire orientation to a science of behavior. True, some forms of behavior were attributable to S => R relations. However, other forms of behavior were a function of other relations. These relations involved the consequences of behavior, and these forms seemed to be the major components of the repertoire of many organisms, humans especially. The relations responsible for these forms could be investigated directly in the laboratory, without postulating intervening processes that mediated other relations. Particularly important was that verbal behavior could be understood as an example of this second form of behavior.

Skinner (1945) further argued that when traditional psychology interpreted operational definitions as justifying an appeal to autonomous, unobservable organismic mediators, traditional psychology adhered to only a methodological behaviorism, rather than a genuine behaviorism. According to methodological behaviorism, researchers and theorists should speak directly only in terms of observables, and not speak directly about unobservables. The rationale continued that science requires agreement, which researchers and theorists can achieve by speaking directly only about the relations that obtain between observable stimuli and observable responses. To be sure, many traditional researchers and theorists believed that mental unobservables do exist and do cause behavior. Again, at issue is how mental unobservables can be included in psychological theories and explanations when those mental unobservables can’t be measured directly and agreed upon, so that they are acceptable in a science. Again, traditional researchers and theorists answered this question by arguing that the observable measures provided by an operational definition generated agreement based on the evidence for the mental unobservables and therefore satisfied the requirements of a science (Schneider & Morris, 1987; Zuriff, 1985). Traditional researchers and theorists further argued that given this interpretation of operationism, talk of mental unobservables was perfectly permissible, and might even be preferred, for example, because those unobservables could be regarded as “theoretical.” Indeed, such arguments often carried the day, given that the arguments relied on the great intellectual prestige associated with theoretical endeavors and system building in general.

The acceptance of the traditional interpretation of operationism and the resulting mediational orientation also implicitly promoted a mischievous conception of verbal behavior. According to this mischievous conception, verbal behavior was an inherently symbolic, referential process. A word was a symbol. In turn, the referent for the symbol needed to be established to provide the meaning for the word. In the case of operationism and methodological behaviorism, the referent was the public observation that could be agreed upon and serve as the surrogate for the unobservable, mediating mental construct.

An extremely contentious question then emerged as to whether the term or concept was identical to the referent or was really something else. In other words, did the operational definition simply provide a referent for the term or concept that was sufficient to stand as a surrogate for the term or concept, and the actual identity of the term or concept was something else, which had to be determined through some other means? It is interesting that MacCorquodale and Meehl’s (1948) acceptance of surplus meaning for hypothetical constructs kept the door open for the latter interpretation, and this whole debate lingers on, with some contemporary authors missing the point (Burgos, 2015, 2021; Burgos & Killeen, 2019). Indeed, at the heart of orthodox mentalism is precisely the notion that the actual referent or identity of a theoretical concept is not equivalent to whatever procedure or pattern of measured data constitutes the operational definition of the concept. This notion follows directly from the preferred hypothetical construct interpretation of theoretical terms and concepts. Here is the cognitive psychologist Suppes (1975) on this matter, suggesting that the mediating hypothetical constructs in the neobehaviorist tradition are actually consistent with the cognitive processes of contemporary cognitive processes, notwithstanding the strident claims of superiority coming from the latter camp:

[I]n neobehaviorism as opposed to classical behaviorism it is quite appropriate to postulate a full range of internal structures, ranging from memory hierarchies to language production and language comprehension devices that cannot be, from the standpoint of the theory, directly observed. . . . It is my view that the approach of cognitive psychologists or of psychologists interested in complex problem solving or information processing (Newell & Simon, 1972, is a good example) could be fit within a neobehaviorist framework if a proper amount of structure is assumed and not mastered from scratch. . . . There is not a formal inconsistency between the two viewpoints. (pp. 270, 279–280)

Worth noting in this passage is that Suppes subscribed to the reified existential status of cognitive processes implied by the preferred hypothetical construct interpretation of theoretical terms, just as did the mediational approach of the neobehaviorists.

A truth criterion based on coherence looks to whether verbal behavior is logically valid. This truth criterion became prominent under neobehaviorism and continues in contemporary cognitive approaches in psychology. In contrast, a truth criterion based on pragmatism looks to whether verbal behavior promotes effective action, and is part of radical behaviorism. Allowing for multiple control, that effective action is a function of the operant contingencies involved in the behavior of a subject that is observed and the verbal behavior of a researcher that is taken to explain the subject’s behavior. Effective action does not follow from conceiving of a word as a symbol, regardless of whether a referent that provides meaning for a word is observable or unobservable, and regardless of whether a theoretical proposition involving those words is logically valid.

Skinner (1945, 1957) was concerned early on that the general orientation of a word as a symbol whose meaning was found in its referent and a coherence criterion for truth was beside the point. A word was not a symbol whose meaning was found in its referent any more than a rat’s pressing a lever was a symbol whose meaning was found in its referent. Contingencies were responsible for a rat’s pressing a lever, and contingencies were also responsible for human’s engaging in the form of verbal behavior called words. The contingencies might even be complex and involve multiple control (Skinner, 1957). The behavioral sense of verbal behavior might be more appropriately reflected by saying “wording,” in that some form of behaving is responsible for the response product called a “word.” After all, we do say “speaking” often enough in connect with the form of behaving verbally called “speech.” To think of a word as a symbol with a referent that was somewhere else, at some other level of observation, with different dimensions and measured in different terms (e.g., Skinner, 1950) had the effect of insulating the analysis and explanation of a natural behavioral process like thinking from appropriate scientific scrutiny. As Skinner (1979) later put it, “Behaviorism was a theory of knowledge, and knowing and thinking were forms of behavior” (p. 116). For radical behaviorism, observable behavior was not evidence that justified talk of underlying, causal mental processes, which could then be symbolically represented as intervening, theoretical constructs that mediated S => R relations. Rather, at issue was whether some observation that was traditionally interpreted as revealing an underlying, causal mental process that followed different laws than observable behavior could be reinterpreted as involving a form of behavior after all. The behavior could even be at a covert level, attributable to operant contingencies that had the same functional relation to environmental circumstances as overt operant behavior. Covert behavior was presumably acquired at the overt level, but then receded to the covert level through such environmental influences as punishment of the overt form, expedience of the covert form, or lack of resources for the overt form. Overall, Skinner argued that a genuine behaviorism in terms of operant behavioral processes and operant contingencies would set things right. True, some of these events might be covert and not currently accessible from the vantage point of others. Nevertheless, the covert events may be interpreted as a function of the same behavioral processes as overt events and talk of these events was not attributable to such extraneous sources of control as cultural tradition or linguistic processes that resulted in reification (Skinner, 1957). Of course, some verbal behavior thought to be a function of observations might actually be only an intraverbal function of cultural tradition and irrelevant linguistic processes that resulted in reification. Skinner criticized mediating “theoretical” terms or concepts that were invoked in such instances as “explanatory fictions.”

The test case was Skinner’s (1945) naturalistic account of private behavioral events. In this account Skinner noted that talk about our private sensations and feelings, on the one hand, and the influence of such covert forms of behavior as thinking, on the other hand, are a function of our interactions with the social, verbal community, just as are many other classes of our behavior. In particular, the verbal community supplies the differential reinforcement that is necessary for any form of verbal behavior to develop. That differential reinforcement is supplied on some occasions but not on others. With respect to talk about our sensations and feelings, a critical question is, “Under what circumstances does the verbal community supply the differential reinforcement necessary for our talk about our sensations and feelings to develop when the sensations and feelings are not accessible to the verbal community?” This question concerns the “problem of privacy.” Skinner’s answer noted that the verbal community overcomes the problem of privacy and provides the necessary differential reinforcement when talk about with our sensations and feelings is correlated with certain overt events. Particularly important overt events are collateral responses and public accompaniments (Skinner, 1945). The importance of collateral responses is that others may give aid to persons who are seen to be rubbing or favoring some afflicted area, and who then talk about what they are experiencing. The importance of public accompaniments is that others may give aid to persons who are observed to be struck forcefully by some object, and who then talk about what they are experiencing. Talk about sensations and feelings in other circumstances may also be a function of stimulus generalization from overt to covert stimulation. For example, a child may experience and talk about a fluttering sensation when a butterfly lands on their arm. This is the overt event. When the child later becomes nervous and experiences a related sensation of fluttering in their stomach, the child may talk of “butterflies in their stomach.” This talk involves a covert event, linked through the stimulus generalization of the fluttering sensation to the overt event. These types of events might begin in early childhood, and talk of sensations and feelings typically becomes more widespread as a child matures. Over time, children are then better able to make themselves understood, which is reinforcing for the children because their caregivers know better what to do to care for them, and reinforcing for their caregivers because the caregivers know better how to help those in their care. Nevertheless, some metaphorical influence remains, as when individuals speak of sharp pains and dull pains. Sharp pains presumably result from unfortunate contact with sharp objects, much as dull pains presumably result from unfortunate contact with dull objects. Such contact illustrates the importance of understanding public accompaniments because caregivers can then remove threatening objects and prevent injury to those for whom they are responsible. A further benefit is that instruction in all of these interactions can be meaningfully included in training programs, such as for caregivers for individuals with disabilities. The process is distorted in cases of malingering or hypochondria, for example, when a speaker talks of pain or exaggerates being in pain in an effort to escape from demands or to gain otherwise undeserved attention. Indeed, listeners might doubt a speaker’s talk of being in pain precisely because of the lack of collateral responses or public accompaniments.

As noted earlier, an operant response might be acquired in overt form, then recede to overt level because of circumstances in the environment. Regardless, the covert form of the response could still have the same discriminative function as the overt form because even though the stimulation from the covert form was not as strong as that from the overt form, the covert stimulation still coincided with the overt stimulation. Again, for Skinner, the answers to questions about covert events were found in an analysis of operant behavioral processes, rather than the processes of either classical S=>R behaviorism or a mediational neobehaviorism based on hypothetical constructs of uncertain origin and ontology. In particular, the answers were not a matter of asserting that publicly observable measures established meaning because researchers and theorists could agree on those measures, and that only those variables and relations postulated under a criterion of agreement were meaningful and hence appropriate in a science of behavior. Answers in terms of operant behavioral processes further offered the opportunity for prediction and control, which Skinner later identified when he wrote of self-control (1953, pp. 227–241) and how to teach thinking (1968, pp. 115–144). In practical terms, who would not benefit from learning how to solve certain mathematical problems, such as computing a 15% tip for a server in a restaurant, in the absence of paper and pencil? Isn’t it possible to take 10% of a bill by covertly moving a decimal point on the bill to the left and then by covertly adding half that amount to get to 15%? These actions are not “mental math” but behavioral. The speaker is simply doing many of the same things as when paper and pencil are available.

Again, the traditional interpretation of operationism in psychology was based on a symbolic-referential conception of verbal behavior. This interpretation was assumed to provide an antidote to nonscientific thinking by arguing that the referent for a term or concept in an analysis or explanation of an event should be agreed upon. In turn, the referent for a term or concept could be agreed upon when it was the result of intersubjectively verifiable procedural or mensurational operation. In contrast to traditional psychology, Skinner (1945) argued that operationism is more usefully interpreted in a science of behavior as a matter of analyzing the extent to which whatever scientific terms or concepts are involved in the analysis and explanation of an event are a function of the operations that actually participate in a behavioral event. Especially important are the consequential operations and signaling operations that constitute an operant contingency (e.g., Catania, 2013). Consequential operations involve delivering a consequence when a particular response occurs. Signaling operations involve signaling, for example, with a previously neutral stimulus, that a biologically significant stimulus will be delivered independently of any particular response or that a consequence will be delivered when a particular response occurs. Combining a signaling operation with a consequential operation constitutes arranging the operant contingency of discriminative stimulus, response, and reinforcer. Again, a critical aspect of scientific epistemology on a radical behaviorist view is assessing the function of whatever operations are in effect in the environment—and often those operations involve operant contingencies, even when some operations may be effective only with respect to the individual who experiences them. Thus, a critical aspect of operationism on a radical behaviorist view is aligning analytical and explanatory verbal behavior with whatever operations—and often those operations involve operant contingencies—actually influence behavior, even when the event involves covert behavior. The benefit is that a verbal repertoire so generated may then have a discriminative effect in other situations. Of course, the operational analysis of a psychological term may also reveal that the contingency involves consequences that are purely social and cherished for irrelevant and extraneous reasons, as in explanatory fictions that have little bearing on prediction and control. Again, the commitment in radical behaviorism is to a pragmatic criterion of truth, in which truth is a matter of such practical consequences as the degree to which the verbal behavior in question is discriminative for prediction and control. In contrast, the commitment in traditional psychology is to a coherence criterion, in which truth is a matter of logical relations that are independent of practical consequences. Overall, Skinner’s interpretation of operationism made no place for asserting that a given procedural or mensurational operation justified the meaning of some term or concept from another domain, when in actuality the source of control for that term or concept was an irrelevant social factor. Indeed, as Skinner (1945) put it, the traditional interpretation of operationism only preserves ancient explanatory fictions unharmed. Thus, the traditional interpretation may yield contentment based on agreement but neither genuine progress nor a promise of practical benefit.

No doubt evident by this point is that the enduring interest in conceptual issues in radical behaviorism (e.g., thinking, problem solving, consciousness) follows from the radical behaviorist view of verbal behavior and epistemology. The radical behaviorist view of verbal behavior is directly opposed to traditional, mentalistic, mediational views of both verbal and nonverbal behavior, particularly when those views embrace the symbolic-referential assumptions underlying a traditional view of verbal behavior. Again, the important issue is the source of the influence over the verbal behavior that is regarded as scientific and explanatory. Does the influence emanate from descriptive processes and their extensions, or from (1) linguistic processes resulting in reification; (2) mental traditions in society and culture; and (3) inappropriate metaphors, where the latter three give rise to explanatory fictions? Does the meaning of analytic and explanatory verbal behavior follow from an operant contingency or a symbolic-referential process? When it came to verbal behavior, Skinner (1945) argued in favor of functional processes and their extensions derived from operant contingencies, unlike traditional positions that were derived from reification, mental traditions, and inappropriate metaphors according to a symbolic-referential conception of verbal behavior.

For example, when reification influences traditional approaches, researchers and theorists take adjectives or adverbs, convert them into nouns, then assume that because of their status as nouns the terms symbolically represent the acts, states, mechanisms, or processes that must actually exist and that cause the properties that the adjectives or adverbs describe. An illustration is when someone who does something intelligently is assumed to possess some mental entity called “intelligence” that causes the form of behavior described as intelligent. When such social-cultural institutions as religion and jurisprudence influence traditional approaches, researchers and theorists then come to implicitly accept mental phenomena in their work as autonomous causes, either initiating or mediational. For instance, in jurisprudence, crime is conceived as the result of premeditated acts. In traditional approaches to the study of memory, such mischievous metaphors as storage-and-retrieval mislead researchers and theorists to look for explanations somewhere else, at some other level and with invented or outright fictitious properties. Once again, traditional approaches are based on a symbolic-referential view of verbal behavior, and numerous problems and controversies regarding conceptual issues arise from that view, especially via reification (e.g., Skinner, 1957).

The alternative approach in radical behaviorism may be further illustrated by considering the traditional topic of consciousness. For radical behaviorism and hence behavior analysis, consciousness may be understood as a state of affairs wherein individuals respond to their own behavior that past circumstances have engendered, that present circumstances are engendering, and that future circumstances are likely to engender. Often but not necessarily the responses to one’s own behavior are verbal. These responses arise when members of the social community ask other members the relevant questions about what they did in the past, what they are doing currently, what they are likely to do in the future, and why. Appropriate answers are then reinforced. The responses to one’s own behavior can then enter into further contingencies as a form of discriminative stimulation for subsequent behavior, such as by making that behavior more effective at gaining reinforcers or sidestepping aversives. Through coincident forms of stimulation, covert forms of these responses may have effects that are similar to the effects of the overt forms. Regardless of whether the responses are overt or covert, they are useful to the individual as a form of self-knowledge leading to self-management. Overall, consciousness may be understood as a product of the self-descriptive contingencies maintained by a verbal community (Skinner, 1945, p. 277). Radical behaviorism therefore stands as a robust alternative to contemporary cognitive approaches that take consciousness to be an intrinsic mediational process with nonbehavioral dimensions, ironically in the same symbolic-referential framework as mediational neobehaviorism that began in the 1930s.

Again, at issue is whether traditional approaches create a problem by legitimizing the initiating or mediating role of autonomous internal states. One problem in such instances is construing Aristotelian formal causes as efficient causes in the hypothetical-deductive explanatory model anchored in logical positivism. The result is an endorsement of mentalism, methodological behaviorism, and a truth criterion of coherence rather than pragmatism. Zuriff’s (1985) treatment of hypothetical constructs and dispositions is an excellent reference here. Overall, contemporary cognitive psychology may be understood as largely the continuation of the mediational approach proposed earlier in mediational neobehaviorism. To be sure, the mediators in contemporary mentalism are much more complex than those of mid-20th-century neobehaviorism, but the provenance of contemporary mentalism lies in the tradition established in neobehaviorist mediation. True, Skinner recognized “third variables” all along. However, he conceived of third variables as the result of such events as found in a history of interaction with the environment, rather than as the autonomous, initiating, or mediating fictions that were postulated in neobehaviorism and mentalism. Throughout, the whole traditional orientation of hypothetical mediating internal states contrasts with the pragmatic causes found in behavior analysis. That the internal mental states in traditional psychology are considered hypothetical efficient causes is problem enough. Given that the conventional goals of science are prediction and control, how can the purported states contribute to control when they are taken to be only hypothetical? One objective here for students follows directly from Skinner’s analysis of private behavioral events: What contingencies might lead speakers to describe a pain in such everyday terms as a “burning” pain? A second objective might be for students to describe an example of how reification has created an explanatory fiction in traditional psychology. The index in most traditional textbooks provides numerous instances where authors have done so.

The Second Half of the Suggested Course: The Basic Dimensions of Radical Behaviorism

In a highly influential article, Baer et al. (1968) proposed seven basic dimensions of applied behavior analysis: general, effective, technological, applied, conceptually systematic, analytic, behavioral. Many students have constructed an intraverbal mnemonic of “get a cab” regarding these dimensions. In this same regard, Day (1969b) offered four basic dimensions of Skinner’s behavior analysis: (1) a focal interest in the control of behavior; (2) the focal awareness that any scientist is him/herself a behaving organism; (3) the focal interest in verbal behavior controlled by directly observed events; and (4) the focal awareness of the importance of environmental variables. Indeed, a theme of the present suggested course follows from combining Day’s dimensions (2) and (3): a focal awareness that any scientist is him/herself a behaving organism, whose ostensibly scientific verbal behavior may be controlled by social processes that are cherished for irrelevant reasons in addition to directly observed events. More is said in this regard later. For now, and in the tradition of the aforementioned distinguished articles by Baer et al. (1968) and Day (1969b), the present article suggests the following eight dimensions for a course in the PCH foundations of radical behaviorism (e.g., Moore, 2008):

Behavior as a subject matter in its own right

Behavior as public (overt) and private (covert)

Analytic and explanatory concepts as generic, functional, and relational

Verbal behavior as operant behavior

Selection by consequences as a causal mode

Pragmatism as a truth criterion

Opposition to mentalism and methodological behaviorism as theoretical-explanatory stances

Social activism according to behavioral principles as a means of contributing to the welfare of humankind