Abstract

The hypertonicity of internal anal sphincter resting pressure is one of the main causes of chronic anal fissure. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the effect of oral administration of l-arginine on the improvement of the anal fissures by relaxing the internal anal sphincter. Seventy-six chronic anal fissure patients (aged 18–65 years) who were referred to Rasoul-e-Akram Hospital, Tehran, Iran from February 2019 to October 2020 participated in this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Participants were allocated into treatment (l-arginine) and placebo groups. They took a 1000 mg capsule three times a day for 1 month, and then we followed them at the end of the first and third months after the intervention. Clinical symptoms, anal sphincter resting pressure, and quality of life (QoL) were completed at baseline and the end of the study. The analysis of data showed a significant decrease in bleeding, fissure size, and pain for each group; however, in the L-arginine group was more than the control group at the end of the study (P values < 0.001). Following that, a significant increase in QoL was seen just in patients treated with l-arginine (P value = 0.006). In addition, the comparison of anal pressures at baseline and, between groups at the end of the study showed a significant reduction in sphincter pressure in patients treated with l-arginine (P value < 0.001, = 0.049; respectively). The oral administration of 3000 mg l-arginine can heal chronic anal fissures by reducing internal anal sphincter pressure with more negligible side effects. However, we recommend long-term study with more extended follow-up.

Clinical trial registry: IRCT20190712044182N1 at Iranian clinical trials, date: 2019-08-27.

Keywords: l-Arginine, Anal fissure, Sphincter pressure, Clinical symptoms, Quality of life

Introduction

An anal fissure is a condition resulting from a superficial open wound or tear in the anus mucosa with a sharp pain that can extend from the anal canal to the periphery (Schlichtemeier and Engel 2016). It is one of the most common anorectal diseases that equally occurs in men and women and is usually more common in middle age and youth, but can also occur in old age and childhood (Chaudhary and Dausage 2019; Newman and Collie 2019). Anal fissures can be acute or chronic. Chronic fissures are present for more than 6–8 weeks (Newman and Collie 2019). Fibers of internal anal sphincters with hypertrophied anal papilla and a skin tag expose in chronic fissure (Ferri 2021).

The etiology of an anal fissure is not precisely clear, but trauma to the anal canal by the passage of hard or large stool is a common fissure cause. Hypertonicity of resting pressure of the internal anal sphincter is seen in patients with fissures as compared with normal controls, which can induce pain and spasm with defecation, and it also has an unfavorable effect on wound healing by reducing blood flow to the traumatized anoderm. Studies have shown abnormal increase of anal contraction in patients with anal fissures, which can explain the sphincter spasm and pain experience with defecation (Nothmann and Schuster 1974; Braun and Raguse 1985). Fissures recurrence, wound infection, or abscesses might occur when ineffective therapeutic measures are taken. Ensuring the soft stools using fiber and laxative, pain controlling by analgesia drugs or short-term use of topical anesthetic, and wound healer ointments, such as glyceryl trinitrate and diltiazem hydrochloride, which can have the side effect profile and recurrence rate for some patients, is the most common management of anal fissures (Medhi et al. 2008; Latif et al. 2013; Stewart et al. 2017). Nonhealing wounds, pain, and bleeding can lead to fecal impaction as patients avoid defecation, which can result in decreased quality of life (Sailer et al. 1998).

l-Arginine is a semi-essential amino acid that performs functions in the body, such as improving the immune system, accelerating healing time and repairing damaged tissues, reducing the risk of heart disease by lowering blood pressure, and increasing muscle mass by increasing blood flow (Scibior and Czeczot 2004; Albaugh and Barbul 2017). The metabolites produced by arginine perform many of these actions. Ornithine and polyamines, such as spermine and spermidine are arginine metabolites involved in cell division and, cell growth processes. Proline, another metabolite of arginine, plays an important role in collagen structure, tissue repair, and wound healing (Li et al. 2001; Majumdar et al. 2016). One of the most important metabolites of this amino acid is nitric oxide (NO), which acts as a neurotransmitter and vasodilator in the body (González and Rivas Ferreira 2020). Low amounts of NO increases cell survival and stimulate cell division, in contrast in higher concentrations, can promote apoptosis and cell aging; this action play a crucial role in the immune response, inflammation, and free radicals reduction (Luiking et al. 2012; Kelly and Pearce 2020). Therefore, this hypothesis is raised that l-arginine can improve anal fissure due to its effect on wound healing and increase blood flow to the anal area resulting in reduce the pressure of the internal sphincter.

Various studies have investigated the effect of topical l-arginine gel at doses of 400 mg/ml. The results of the studies demonstrated that the use of l-arginine gel significantly reduced anal muscle tone in manometric evaluations, and rectal blood flow increased in laser Doppler flowmetry assessments. However, long-term use of topical l-arginine due to the pH of the drug, osmolality, and its effect on sphincter tonicity are still questionable, and its side effects have not been evaluated (Acheson et al. 2003, 1; Griffin et al. 2002; Gosselink et al. 2005; Fariborz 2007). To date, only a pilot study performed in 2005 examined the effect of 15 g/day oral l-arginine supplementation on eight healthy individuals for seven days via reducing anal pressure, and the results showed that the level of plasma arginine significantly increased, but the anal resting pressures and anodermal blood flow did not show a significant effect (Prins et al. 2005).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the effect of oral L-arginine as a safer method with better performance on clinical symptoms, quality of life, and internal anal sphincter pressure in patients with chronic anal fissure.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with parallel design conducted in the 4-week intervention and the 8-week follow-up. We recruited 76 adult men and women (aged 18–65 years) with chronic fissures who were referred to a gastroenterologist in gastrointestinal clinic, Rasoul-e-Akram Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Based on patients’ symptoms like bleeding (bright red) after passing stools without a past medical history of bowel disease, physician diagnosed an anal fissure by physical examination. The study performed from February 2019 to October 2020. Participants who had chronic anal fissure (acute anal fissures classified as last < 6 weeks, whereas chronic fissures last > 6 weeks), without any GI disorder as inflammatory bowel disease, celiac, a history of colon cancer, without history of fissure or hemorrhoid surgery in the last 12 months, other malignancy, absence of diseases that fissures can be complications such as tuberculosis, AIDS, syphilis, herpes, leukemia; no history of heart disease, were not pregnant or lactating women, were enrolled in this study.

The study exclusion criteria were specified as follows: a diagnosis of specific gastrointestinal diseases, such as Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis, gastrointestinal cancers, or other malignancies during the study; pregnancy during supplementation; exacerbation of the disease or failure of patients to recover, resulting in the discontinuation of the drug and referral to a colorectal surgeon for fissure surgery during the study, any abnormal reactions to the supplement like gastrointestinal reactions including nausea, vomiting, heartburn, recurrent diarrhea, allergic reactions including itching and rash, and hypotension; consumption less than 80% of supplements; and who were on special dietary pattern; and unwillingness of the person to continue cooperation. Participants completed demographic data, medical history, physical activity, and anthropometric indicators at baseline and the end of the study.

Ethics statements

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1398.319), Tehran, Iran, and registered in the Iranian clinical trials (IRCT20190712044182N1-Date: 2019-08-27). The aim of the study was clarified to the participants, and they signed a written informed consent form demonstrating acceptance of study details.

Intervention

The study participants were assigned to two groups. They received 3000 mg l-arginine, or a placebo filled with Maltodextrin. Capsules were made by Karen company, Yazd, Iran. The shape, color, and packing of placeboes were like l-arginine. Patients received a capsule contained 1000 mg l-arginine or placebo three times a day after each meal for four weeks. The follow-up of patients was continued up to the next eight weeks without any oral anti-fissure agents. In addition to l-arginine or placebo supplementation, during the intervention and follow-up, all patients received once a day Lidocaine-H 4% ointment before defecation and 30 cc/day syrup magnesium hydroxide (in constipate patients) during the 4-week intervention and 8-week follow-up. According to studies conducted, the amount of l-arginine absorption in the intestine is about 20% of a 10-g supplement and depends on various factors, including L-arginine concentration, time of supplementation, and diet. The daily dose of 3 g of l-arginine is safe and has no side effects (McNeal et al. 2016).

Randomization, allocation, and blinding

For randomization, the permuted block randomization was used with quadruple blocks. According to the sample of size n = 76, 19 blocks were produced using the online site (www.sealedenvelope.com). For the concealment in the randomization process, dedicated codes were generated by the software used on the pharmaceutical box.

We performed the randomization process using the relevant software, and also provided the list to the executor in the form of codes A and B for two interventions. Both of patient and the physician who evaluated the clinical and manometric symptoms were blind to the medication received. Other evaluators who filled out questionnaires were also blind.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the assessment of the severity of symptoms. Internal anal sphincter pressure, quality of life, anxiety, and depression were the secondary outcomes.

Sample size calculation

Considering a similar study (Gosselink et al. 2005) for the two primary outcomes of the study (anal pressure and clinical symptoms), the sample size was determined by a probability of type I error of 5% (α = 0.05) and a probability of type II error of 20% (β = 0.2; power = 80%). The reduction in anal pressure in patients receiving arginine was 14 ± 74, which according to the study, was about 15% improvement compared to placebo, and the reduction of clinical symptoms based on VAS after receiving arginine was 1.3 ± 1.5, which according to the results of this study was approximately 80% improvement. In the current study, we calculated the sample sizes of 25 and 32 per group for each outcome, respectively, and also determined the maximum of which as the final sample size. At the end, due to a 20% chance of falling, this number was increased to a total of 76 patients needed. The variance in both groups of placebo and treatment was assumed to be equal.

Information gathering tools

Physical examination, clinical symptoms

At the first visit, patients filled the questionnaires that included bowel habits, duration of suffering from anal fissure, and fissure size, which was determined in millimeters by a gastroenterologist in clinical examination. In addition, the patients were asked to report the symptoms of headache at the beginning and end of the study.

To evaluate the clinical signs, we used the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), giving score of 0–100 for each symptom. The patient’s bleeding was questioned and classified into mild bleeding criteria: bloody discharge with mucus unrelated to defecation; moderate type: sometimes there is bleeding with defecation; and in the severe type: defecation is accompanied by bleeding each time. Wound healing examination is also graded based on the appearance of chronic anal fissure including grade 1 includes good and complete healing: no wounds or cracks is seen in the fissure site; grade 2 includes moderate and partial healing: wound or simple longitudinal incision with fibrous bands of the internal sphincter muscle in the wound floor; grade 3 includes poor healing without change: the appearance of the wound is not the same as before, and the deep wound protrudes with a scar; grade 4 includes very poor healing: chronic abscess fissure wound or fistula is added. We evaluated Pain during defecation according to 4 scales graded: score three severe and unbearable pain, score two moderate pain, score one mild pain and score 0 for excretion is painless (Eshghi et al. 2006). All criteria were graded and reported 0 to 100.

General health survey short form-36 (SF-36)

The 36-item Quality of Life (SF-36) is the most widely used tool for measuring the quality of life and is also used for people with anal fissures (Arısoy et al. 2017). This questionnaire has already been validated in Iran (Montazeri et al. 2005). The SF-36 questionnaire has 36 questions and consists of 8 scales, each consisting of 2–10 items. The subscales of this questionnaire are physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical health (RP), role limitations due to emotional problems (RE), energy/fatigue (EF), emotional well-being (EW), social functioning (SF), pain (P), general health (GH). The integration of the subscales also yields two other general subscales, which are as follows:

Physical health sub-scale: the sum of the subscales including PF, RP, P, and GH.

Mental health sub-scale: a set of subscales of role disorder due to RE, EF, EW, and SF.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADs)

The HADS questionnaire (Navarro-Sánchez et al. 2021; Zigmond and Snaith 1983) is a 14-item self-rating scale used to assess anxiety and depression symptoms in chronic anal fissure patients. The questionnaire has two parts, consisting of seven questions related to anxiety (HADs-A) and seven to depression (HADs-D). Each item rated between 0 (“not at all”) and 3 (“most of the time”), which the higher scores indicate more significant anxiety or depression symptoms. The total score is calculated by the sum of the concession items, ranging from 0 to 21. The scores from 0 to 7, 8 to 10, and 11 to 21 illustrated a normal scale, borderline, and clinical problems, respectively.

Balloon pain score

We assessed the severity of the patients’ anal pain and spasm in the initial evaluation in the clinic before the manometry. It was performed with a 20cc volume balloon (with maximum of 6 atm pressure) which was inflated by a 20cc syringe. The balloon is placed in the middle of the anus near the inner sphincter and inflates gently until the patient feels pain. The amount of air injected (0–20) was considered a measure of pain, and spasm in the patient and we compared its amount at the beginning and end of the intervention.

Anorectal manometry test

Anorectal manometry is a medical test to measure the pressures and the function of the anus and rectum. We performed this procedure using small flexible water perfused catheter with a balloon on end, inserted through the anal opening, past a ring of muscles called the anal sphincter before passing into the rectum. This causes the nerves and muscles in the rectum and anus to squeeze. The end of the tube remains outside of the anus. It is connected to a machine that records the contractions and relaxations of the rectum and anal sphincter. The night before the test, patients should not eat or drink foods. The exam took 10 min to complete.

Statistical analysis

The quantitative data were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and also the qualitative data were reported as frequency (percentage). The normality of the data was checked by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and other indicators. If the normality of quantitative variables was satisfied, the distribution between groups and within groups would be performed by independent t test at each point in time of study and paired t test, respectively. To examine the mean outcome at three-time points, we used an ANOVA analysis with repeated measures. If the normality of the data was not satisfied, we would compare them with non-parametric tests, including Mann–Whitney and Wilcoxon and Friedman test. Qualitative variables between the two groups were compared by Chi-square test and also variables within groups were compared by McNemar test. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.

Results

Enrollment and study completion

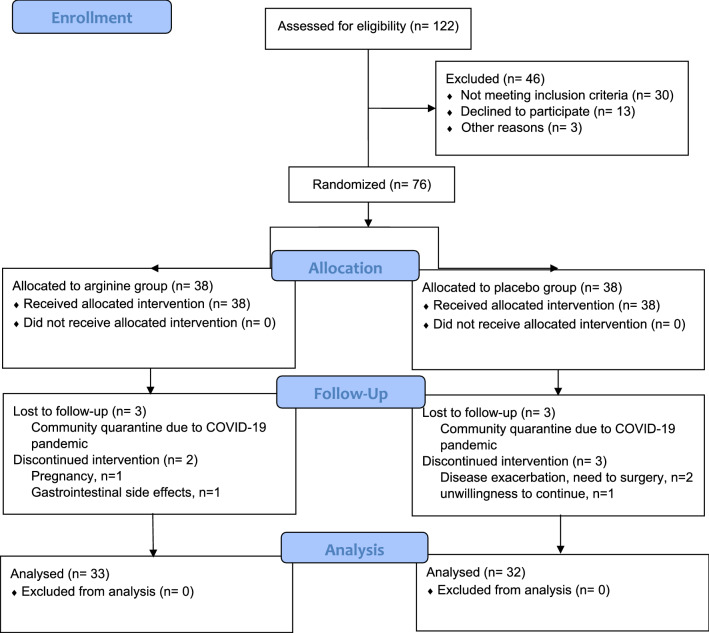

Of the 122 eligible participants, 76 patients with chronic anal fissure were enrolled in the study, and 65 completed the study. 11 participants were excluded from the study because of community quarantine due to the COVID-19 pandemic, disease exacerbation, and need to surgery, unwillingness to continue. The flowchart of the study participants is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of enrolled patients in the study

Characteristics of the study participants

The final analysis was done for participants who completed the study (35 women and 30 men, age: 39.79 ± 11.72 years, BMI: 27.09 ± 4.85 kg/m2). All patients had chronic anal fissure (32.12 ± 51.80 months) and most of them suffered from constipation in both the groups. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of alcohol consumption, smoking, and physical activity at the baseline of the study. Table 1 shows the data.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the study participants at baseline

| Characteristics |

l-Arginine (n = 33) |

Placebo (n = 32) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.64 (10.78) | 38.94 (12.66) | 0.563 |

| Height (cm) | 168.24 (10.50) | 167.06 (12.13) | 0.677 |

| Weight (kg) | 75.85 (15.88) | 76.26 (14.75) | 0.913 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.78 (4.88) | 27.41 (4.83) | 0.601 |

| Duration of fissure (months) | 36.39 (53.62) | 27.86 (49.99) | 0.509 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 15 (45.5%) | 15 (46.9%) | 0.909 |

| Female | 18 (54.5%) | 17 (53.1%) | |

| Alcohol consumption status | |||

| Yes | 5 (15.2%) | 5 (15.6%) | 0.958 |

| No | 28 (84.8%) | 27 (84.4%) | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 7 (21.2%) | 7 (21.9%) | 0.948 |

| No | 26 (78.8%) | 25 (78.1%) | |

| Bowel habit | |||

| Normal | 15 (45.5%) | 9 (28.1%) | 0.156 |

| Constipation | 18 (54.5%) | 21 (65.6%) | |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.3%) | |

| Activity | |||

| Very light | 18 (54.5%) | 21 (65.6%) | 0.260 |

| Light | 13 (39.4%) | 7 (21.9%) | |

| Moderate | 2 (6.1%) | 2 (6.3%) | |

| Heavy | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.3%) | |

Quantitative data are shown as mean ± SD and qualitative data are reported as number (%)

P values are statistically significant (< 0.05)

Clinical symptoms

The significant wound heal was seen in both groups, and the size of the fissure was reduced in the treatment group from 7.52 ± 3.01 to 2.42 ± 2.68 mm and from 7.81 ± 2.76 to 5.16 ± 3.22 mm in the placebo group, where more improvement was demonstrated in the L-arginine group compared to the placebo group (P < 0.001). As shown in Table 2, the VAS questionnaire analysis to assess the alteration of the severity of clinical symptoms demonstrated that all factors in both groups, including bleeding, wound healing, pain, and VAS-total score, were significantly improved from the baseline compared to the control group at the end of the study. We observed more significant improvement in the group receiving l-arginine. Minor fissure recurrence was seen in the control group at the 3-month follow-up. We did not see new ulcer and tag on the anus in both groups. At the beginning of the study, headache was observed in l-arginine and control groups (30.3% and 34.4%, respectively). After taking the supplements, the headache improvement was observed in 7 and 1 patients in the intervention and control groups, respectively, indicating that there was a significant difference between groups at the end of the study (P = 0.026). Data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparisons of severity of symptoms, anal pressure, and balloon pain score before and after intervention in l-arginine and placebo groups in patients with anal fissure

| Symptoms |

l-Arginine (n = 33) |

Placebo (n = 32) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fissure size (mm) | |||

| Before | 7.52 (3.01) | 7.81 (2.76) | 0.680 |

| After | 2.42 (2.68) | 5.16 (3.22) | < 0.001 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| VAS-bleeding | |||

| Before | 39.09 (25.66) | 39.38 (29.40) | 0.013 |

| After | 15.45 (12.52) | 24.38 (22.99) | |

| Follow up | 12.73 (11.26) | 26.72 (23.13) | |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| VAS-wound healing | |||

| Before | 51.52 (13.49) | 54.06 (15.00) | < 0.001 |

| After | 21.82 (17.22) | 39.37 (21.10) | |

| Follow up | 20.76 (17.68) | 44.06 (15.63) | |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| VAS-pain | |||

| Before | 64.09 (30.50) | 72.66 (28.68) | 0.010 |

| After | 32.73 (24.14) | 59.06 (33.25) | |

| Follow up | 29.55 (26.29) | 59.69 (31.67) | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.018 | |

| VAS-total score | |||

| Before | 154.70 (49.02) | 166.09 (54.22) | < 0.001 |

| After | 70 (38.41) | 122.81 (61.02) | |

| Follow up | 63.03 (45.79) | 130.47 (53.92) | |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Wound site | |||

| Before | |||

| Posterior | 27 (81.8%) | 22 (68.8%) | 0.221 |

| Anterior | 6 (18.2%) | 10 (31.3%) | |

| After | |||

| Posterior | 25 (75.8%) | 22 (68.8%) | 0.528 |

| Anterior | 8 (24.2%) | 10 (31.3%) | |

| P value | 0.500 | 1.00 | |

| Tag | |||

| Before | |||

| Yes | 23 (69.7%) | 22 (68.8%) | 0.934 |

| No | 10 (30.3%) | 10 (31.3%) | |

| After | |||

| Yes | 21 (63.6%) | 22 (68.8%) | 0.663 |

| No | 12 (36.4%) | 10 (31.3%) | |

| P value | 0.625 | 1.00 | |

| Anal itch | |||

| Before | |||

| Yes | 26 (78.8%) | 22 (68.8%) | 0.357 |

| No | 7 (21.2%) | 10 (31.3%) | |

| After | |||

| Yes | 9 (27.3%) | 17 (53.1%) | 0.033 |

| No | 24 (72.7%) | 15 (46.9%) | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.063 | |

| Bleeding | |||

| Before | |||

| Yes | 26 (78.8%) | 26 (81.3%) | 0.804 |

| No | 7 (21.2%) | 6 (18.8%) | |

| After | |||

| Yes | 9 (27.3%) | 18 (56.3%) | 0.018 |

| No | 24 (72.7%) | 14 (43.8%) | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.021 | |

| Pain | |||

| Before | |||

| Yes | 28 (84.8%) | 28 (87.5%) | 0.757 |

| No | 5 (15.2%) | 4 (12.5%) | |

| After | |||

| Yes | 14 (42.4%) | 22 (68.8%) | 0.033 |

| No | 19 (57.6%) | 10 (31.3%) | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.031 | |

| Headache | |||

| Before | |||

| Yes | 10 (30.3%) | 11 (34.4%) | 0.466 |

| No | 23 (69.7%) | 21 (65.6%) | |

| After | |||

| Yes | 3 (9.1%) | 10 (31.3%) | 0.026 |

| No | 30 (90.9%) | 22 (68.8%) | |

| P value | 0.039 | 1.00 | |

| Anal pressure (mmH2O) | |||

| Before | 70.15 (15.15) | 64.72 (16.94) | 0.178 |

| After | 50.61 (14.38) | 57.97 (15.21) | 0.049 |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.053 | |

| Balloon pain score | |||

| Before | 10.24 (4.57) | 11.78 (5.60) | 0.230 |

| After | 16.12 (4.19) | 14.00 (5.02) | 0.070 |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.055 | |

Quantitative data are shown as mean ± SD and qualitative data are reported as number (%)

P values are statistically significant (< 0.05)

Balloon pain score

Evaluation of patients’ tolerance to pain as measured by a balloon showed that patients who received l-arginine less sensed pain (P < 0.001), although this effect was not significant between the groups (P = 0.070) (Table 2).

Anorectal manometry test

Internal anal sphincter resting pressure was significantly decreased in l-arginine-treated patients compared to the baseline values (P < 0.001). As shown in Table 2, sphincter resting pressure was significantly reduced in the treatment group as compared with the placebo group at the end of the study (P = 0.049).

Quality of life

Comparing the total physical and mental health scores at the end of the study with the baseline, we observed a significant increase in quality of life in l-arginine receiving group. However, there was no significant difference between groups at the end of the study. In addition, subgroup analysis demonstrated that emotional well-being, social function, pain, and general health significantly improved in the l-arginine-treated group and also the score of pain significantly relieved compared with the control group at the end of the study as expected. The data are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparisons of mean ± SD HADs-Anxiety, HADs-depression, and quality of life subscales before and after intervention in l-arginine and placebo groups in patients with anal fissure

| Variables |

l-Arginine (n = 33) |

Placebo (n = 32) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HADs—depression total score | |||

| Before | 5.45 (3.87) | 3.62 (3.16) | 0.041 |

| After | 3.79 (3.39) | 3.91 (3.57) | 0.891 |

| P value | 0.004 | 0.451 | |

| HADs—anxiety total score | |||

| Before | 9.76 (5.14) | 7.50 (4.41) | 0.062 |

| After | 6.52 (4.35) | 7.72 (4.55) | 0.280 |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.636 | |

| Physical function | |||

| Before | 79.55 (21.37) | 70.16 (31.35) | 0.165 |

| After | 81.06 (25.88) | 68.91 (31.36) | 0.094 |

| P value | 0.644 | 0.648 | |

| Role disorder due to physical health | |||

| Before | 70.45 (40.24) | 52.34 (45.51) | 0.095 |

| After | 80.30 (35.22) | 71.09 (40.22) | 0.330 |

| P value | 0.243 | 0.042 | |

| Role disorder due to emotional health | |||

| Before | 64.65 (42.44) | 55.20 (47.60) | 0.403 |

| After | 77.78 (37.88) | 69.79 (40.04) | 0.412 |

| P value | 0.102 | 0.104 | |

| Energy/fatigue | |||

| Before | 53.64 (38.65) | 52.03 (27.41) | 0.847 |

| After | 61.06 (23.04) | 54.37 (24.94) | 0.266 |

| P value | 0.238 | 0.513 | |

| Emotional well-being | |||

| Before | 45.09 (25.16) | 50.67 (25.31) | 0.376 |

| After | 62.18 (28.74) | 52.00 (23.41) | 0.123 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.699 | |

| Social function | |||

| Before | 65.53 (31.10) | 71.87 (30.62) | 0.410 |

| After | 79.92 (22.08) | 69.14 (25.20) | 0.710 |

| P value | 0.004 | 0.486 | |

| Pain | |||

| Before | 67.88 (22.04) | 59.77 (28.68) | 0.205 |

| After | 77.73 (24.54) | 62.27 (24.75) | 0.014 |

| P value | 0.014 | 0.478 | |

| General health | |||

| Before | 53.33 (28.96) | 60.16 (27.58) | 0.335 |

| After | 64.84 (29.30) | 61.72 (24.38) | 0.641 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.532 | |

| Total score (physical health) | |||

| Before | 271.21 (90.35) | 242.42 (100.75) | 0.230 |

| After | 303.94 (97.07) | 263.98 (87.54) | 0.086 |

| P value | 0.042 | 0.154 | |

| Total score (mental health) | |||

| Before | 228.90 (100.65) | 229.79 (103.72) | 0.972 |

| After | 280.94 (87.95) | 245.31 (88.34) | 0.108 |

| P value | 0.006 | 0.331 | |

Anxiety and depression

The analysis of the HADs questionnaire showed that the significant mean change of anxiety and depression scores of treated patients at baseline were 3.24 ± 3.75 and 1.66 ± 3.13, respectively. However, this improvement was not statistically significant between the groups (Table 3).

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial, we showed that the supplementation with l-arginine could relieve clinical symptoms, especially pain and bleeding. Following that, we observed a significant increase in quality of life of the patients with chronic anal fissure. In addition, analysis of anal internal sphincter pressures evaluated by manometry and balloon showed the significant reduction of sphincter pressure in these patients.

The exact mechanism of the pathophysiology of anal fissures has not established; however, anorectal manometry testing and laser Doppler flowmetry demonstrated hypertonicity of anal sphincter and reduction of anal blood flow in patients with anal fissure (Schlichtemeier and Engel 2016). The most critical mechanisms of l-arginine in the body are to increase blood flow due to the production of nitric oxide and to decrease the time of wound healing (Scibior and Czeczot 2004). Previous studies have shown that topical l-arginine gel significantly reduces anal resting pressure, increases anal blood flow, and significantly heals persistent fissure without any side effects (Acheson et al. 2003, 1; Griffin et al. 2002; Gosselink et al. 2005; Fariborz 2007). However, a small study conducted on eight healthy volunteers showed that oral administration of 15 g l-arginine had no significant positive effect on anal resting pressure (Prins et al. 2005). In contrast to this study, we observed a significant wound healing, improvement in symptoms, and reduction in anal resting pressure. l-arginine orally or topically improved wound repair; however, the oral administration showed a higher NOS and TGF-β expression, and a significant decrease in inflammatory response. In addition, some studies showed that systemic l-arginine was more efficient than topical l-arginine in wound healing (Zandifar et al. 2015; Jerônimo et al. 2016; Witte et al. 2002; Heffernan et al. 2006). For this reason, the oral supplement was our option to treat the patients.

l-Arginine can heal wound by two mechanisms. The first one is the NO pathway. Arginine is only substance for NO production, which has vasodilation and anti-inflammatory effects (Patel et al. 2017). The second is the production of ornithine that plays a crucial role in collagen formation and wound repairing (Albaugh et al. 2017). Most of the studies conducted on the effect of l-arginine on wound healing were pressure ulcers, which the majority of them administered it in combination with other supplements, such as vitamin C and zinc (Kl and N 2019). However, some studies evaluated the effects of different dosages of l-arginine supplements on post-surgery wound healing, especially cancer patients and in diabetic foot ulcers. They have supplemented patients with 2 gr for 30 days to 30 gr l-arginine for 5 days and most of them showed ulcers improvements (Arribas-López et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2021). Our results demonstrated that a supplementation of 3 g of l-arginine for 30 days was a safe and sufficient dose to heal anal ulcers. In addition, compared to other treatments, such as diltiazem and glyceryl trinitrate, leading to side effects like headaches (Latif et al. 2013; Stewart et al. 2017), treatment with l-arginine not only did not cause headaches, but the headache symptoms were improved in some participants, which can be considered as one of the advantages of using l-arginine as compared with other treatment methods. In addition, digestive complications in some patients should be considered.

Anal fissure disease widely affects the quality of life of patients due to impaired social, work, and personal relationships, which are directly associated with the duration of stricken and severity of symptoms (Navarro-Sánchez et al. 2021; Griffin et al. 2004). In addition, patients who succeeded in treating chronic anal fissures reported an improvement in bodily pain, health-perception, vitality, and mental health (Tsunoda et al. 2012). As mentioned earlier, a significant quality of life improvement was seen in l-arginine treated group, incredibly more relieved feeling of pain was observed in the treated group than the control group. However, quality of life is one of the factors that need a longer time to improve than our study.

On the other hand, anxiety and depression are the main factors that may contribute to the quality of life (Hohls et al. 2019). In addition, from another point of view, the quality of life of the patients with chronic anal fissures, was negatively correlated with severe depression and anxiety, and symptoms were worsened (Arısoy et al. 2017). Administration of anti-anxiety medications in these patients could relieve pain along with standard anal fissure treatment (Mirsadeghi et al. 2021). However, in the present study, l-arginine supplementation did not significantly change the scores of anxiety and depression compared to the control group due to the short time of intervention and assessment, and the score of these indicators significantly improved in the intervention group at baseline. It might be due to the lower numerical scores in the placebo group at the beginning of the study.

Given the strengths of our study, it is, therefore, the first study that has shown positive effect of oral administration of l-arginine with low side effect. The other strength point is the use of anal manometry and balloon pain score for evaluating sphincter pressure. On the other hand, in contrast to the control group, none of patients in the intervention group experienced the exacerbation of disease and needed surgery. However, this study has some limitations. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine, we lost to follow-up of six patients, and there was a time lag to restart the project. Due to the chronicity of the disease, it would be of benefit to follow the patients for longer duration to make a better examination of the condition of the patients in long term. In addition, due to limited financial resources and equipment, we cannot determine the serum levels of L-arginine as vagaries of absorption, metabolism, and the tissue availability, if possible, it is, therefore, recommended that they to be measured in future studies to increase the accuracy of the results.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that oral supplementation of l-arginine in patients with chronic anal fissure could heal the wound and improve clinical symptoms due to reducing resting anal sphincter pressure without side effects. Following that, the quality of life, anxiety, and depression were improved in treatment group. Fissure repair was also seen in control group, but improvement in the intervention group was more than that in controls. However, further studies with long-term follow-up are recommended.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients who contributed to this study. We are so grateful for the cooperation of Zeynab Sadat Ahmadi and other Rasoul-e-Akram hospital staff to accomplish this project.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- QoL

Quality of life

- SD

Standard deviation

- NO

Nitric oxide

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- VAS

Visual analog scale

- PF

Physical functioning

- RP

Role limitations due to physical health

- RE

Role limitations due to emotional problems

- EF

Energy/fatigue

- EW

Emotional well-being

- SF

Social functioning

- P

Pain

- GH

General health

- HADs

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

Author contributions

Designed the study: MKS, MM and FS; contribution in sampling: MKS, MM, SVF and MS; analysis and interpretation of the data: MKS and FSH-B; writing the original draft: MKS, FS, ST, and MM; reviewing and revising the paper: MKS, FS, and MM. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Colorectal Research Center with grant number 98-1-49-14857.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there were no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was carried out according to the guidelines and approved by the Ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acheson AG, Griffin N, Scholefield JH, Wilson VG. l-Arginine-induced relaxation of the internal anal sphincter is not mediated by nitric oxide. Br J Surg. 2003;90(9):1155–1162. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albaugh VL, Barbul A. “Arginine”. Reference module in life sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Albaugh VL, Mukherjee K, Barbul A. Proline precursors and collagen synthesis: biochemical challenges of nutrient supplementation and wound healing. J Nutr. 2017;147(11):2011–2017. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.256404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arısoy Ö, Şengül N, Çakir A. Stress and psychopathology and its impact on quality of life in chronic anal fissure (CAF) patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(6):921–924. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-López E, Zand N, Ojo O, Snowden MJ, Kochhar T. The effect of amino acids on wound healing: a systematic review and meta-analysis on arginine and glutamine. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2498. doi: 10.3390/nu13082498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun J, Raguse T. Pathophysiologic role of the internal anal sphincter in chronic anal fissure. Z Gastroenterol. 1985;23(10):565–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary R, Dausage C. Prevalence of anal fissure in patients with anorectal disorders: a single-centre experience. J Clin Diagn Res. 2019 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2019/38478.12563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eshghi F. The efficacy of l-arginine gel for treatment of chronic anal fissure compared to surgical sphincterotomy. J Med Sci. 2007 doi: 10.3923/jms.2007.481.484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eshghi F, Tirgar Fakheri H, Jamshidi M. Evaluation of topical l-arginine gel and comparison with lateral internal sphincterotomy in treatment of chronic anal fissure. Govaresh. 2006;11(2):98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri FF. Ferri’s clinical advisor 2022. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021. p. 2320. [Google Scholar]

- González M, Rivas JC, Ferreira. l-Arginine/nitric oxide pathway and KCa channels in endothelial cells: a mini-review. Vasc Biol Select Mech Clin Appl. 2020 doi: 10.5772/intechopen.93400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselink MP, Darby M, Zimmerman DDE, Gruss HJ, Schouten WR. Treatment of chronic anal fissure by application of l-arginine gel: a phase II study in 15 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(4):832–837. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0858-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin N, Zimmerman DDE, Briel JW, Gruss H-J, Jonas M, Acheson AG, Neal K, Scholefield JH, Schouten WR. Topical l-arginine gel lowers resting anal pressure: possible treatment for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(10):1332–1336. doi: 10.1097/01.DCR.0000029763.63970.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin N, Acheson AG, Tung P, Sheard C, Glazebrook C, Scholefield JH. Quality of life in patients with chronic anal fissure. Colorectal Dis off J Assoc Coloproctol Great Br Irel. 2004;6(1):39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan D, Dudley B, McNeil PL, Howdieshell TR. Local arginine supplementation results in sustained wound nitric oxide production and reductions in vascular endothelial growth factor expression and granulation tissue formation. J Surg Res. 2006;133(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohls JK, König H-H, Quirke E, Hajek A. Association between anxiety, depression and quality of life: study protocol for a systematic review of evidence from longitudinal studies. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e027218. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerônimo MS, do Prado Barros A, Zen Morital VE, Alves EO, de Souza NLB, de Almeida RM, Medeiros Nóbrega YK, et al. Oral or topical administration of l-arginine changes the expression of TGF and INOS and results in early wounds healing. Acta Cir Brasileira. 2016;31(9):586–596. doi: 10.1590/S0102-865020160090000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B, Pearce EL. Amino assets: how amino acids support immunity. Cell Metab. 2020;32(2):154–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kl S, Yahia N. Effectiveness of arginine supplementation on wound healing in older adults in acute and chronic settings: a systematic review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019 doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000579700.20404.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif A, Ansar A, Butt MQ. Morbidity associated with treatment of chronic anal fissure. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(5):1230–1235. doi: 10.12669/pjms.295.3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Meininger CJ, Hawker JR, Haynes TE, Kepka-Lenhart D, Mistry SK, Morris SM, Wu G. Regulatory role of arginase I and II in nitric oxide, polyamine, and proline syntheses in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(1):E75–E82. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.1.E75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiking YC, Ten Have GAM, Wolfe RR, Deutz NEP. Arginine de novo and nitric oxide production in disease states. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(10):E1177–E1189. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00284.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar R, Barchi B, Turlapati SA, Gagne M, Minocha R, Long S, Minocha SC. Glutamate, ornithine, arginine, proline, and polyamine metabolic interactions: the pathway is regulated at the post-transcriptional level. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:78. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal CJ, Meininger CJ, Reddy D, Wilborn CD, Guoyao Wu. Safety and effectiveness of arginine in adults. J Nutr. 2016;146(12):2587S–2593S. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.234740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhi B, Rao RS, Prakash A, Prakash Om, Kaman L, Pandhi P. Recent advances in the pharmacotherapy of chronic anal fissure: an update. Asian J Surg. 2008;31(3):154–163. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(08)60078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsadeghi A, Novin N, Raisolsadat SMA, Javanbakht M, Zandbaf T. The effect of anti-anxiety medications on the clinical symptoms of anal fissure: a randomized clinical trial. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2021 doi: 10.32592/ircmj.2021.23.11.1167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The short form health survey (SF-36): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabilit. 2005;14(3):875–882. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Sánchez A, Luri-Prieto P, Compañ-Rosique A, Navarro-Ortiz R, Berenguer-Soler M, Gil-Guillén VF, Cortés-Castell E, et al. Sexuality, quality of life, anxiety, depression, and anger in patients with anal fissure. A case-control study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(19):4401. doi: 10.3390/jcm10194401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M, Collie M. Anal fissure: diagnosis, management, and referral in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(685):409–410. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothmann BJ, Schuster MM. Internal anal sphincter derangement with anal fissures. Gastroenterology. 1974;67(2):216–220. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(19)32882-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Preedy V, Rajendram R. l-Arginine in clinical nutrition. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prins HA, Gosselink MP, Mitales LE, Buise MP, Teerlink T, Esser C, Schouten WR. The effect of oral administration of l-arginine on anal resting pressure and anodermal blood flow in healthy volunteers. Tech Coloproctol. 2005;9(3):229–232. doi: 10.1007/s10151-005-0233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sailer M, Bussen D, Debus ES, Fuchs KH, Thiede A. Quality of life in patients with benign anorectal disorders. Br J Surg. 1998;85(12):1716–1719. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichtemeier S, Engel A. Anal fissure. Aust Prescr. 2016;39(1):14–17. doi: 10.1773/austprescr.2016.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scibior D, Czeczot H. Arginine–metabolism and functions in the human organism. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (online) 2004;58:321–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DB, Gaertner W, Glasgow S, Migaly J, Feingold D, Steele SR. Clinical practice guideline for the management of anal fissures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(1):7–14. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda A, Kashiwagura Y, Hirose K-I, Sasaki T, Kano N. Quality of life in patients with chronic anal fissure after topical treatment with diltiazem. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;4(11):251–255. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i11.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte MB, Thornton FJ, Tantry U, Barbul A. l-Arginine supplementation enhances diabetic wound healing: involvement of the nitric oxide synthase and arginase pathways. Metab Clin Exp. 2002;51(10):1269–1273. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.35185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandifar A, Seifabadi S, Zandifar E, Beheshti SS, Aslani A, Javanmard SH. Comparison of the effect of topical versus systemic l-arginine on wound healing in acute incisional diabetic rat model. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(3):233–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Liu G, Huang H, Jun Wu. Advances and impact of arginine-based materials in wound healing. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(34):6738–6750. doi: 10.1039/D1TB00958C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.