Abstract

Objective

This scoping review aimed to comprehensively review strategies for implementation of low back pain (LBP) guidelines, policies, and models of care in the Australian health care system.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, and Web of Science to identify studies that aimed to implement or integrate evidence-based interventions or practices to improve LBP care within Australian settings.

Results

Twenty-five studies met the inclusion criteria. Most studies targeted primary care settings (n = 13). Other settings included tertiary care (n = 4), community (n = 4), and pharmacies (n = 3). One study targeted both primary and tertiary care settings (n = 1). Only 40% of the included studies reported an underpinning framework, model, or theory. The implementation strategies most frequently used were evaluative and iterative strategies (n = 14, 56%) and train and educate stakeholders (n = 13, 52%), followed by engage consumers (n = 6, 24%), develop stakeholder relationships (n = 4, 16%), change in infrastructure (n = 4, 16%), and support clinicians (n = 3, 12%). The most common implementation outcomes considered were acceptability (n = 11, 44%) and adoption (n = 10, 40%), followed by appropriateness (n = 7, 28%), cost (n = 3, 12%), feasibility (n = 1, 4%), and fidelity (n = 1, 4%). Barriers included time constraints, funding, and teamwork availability. Facilitators included funding and collaboration between stakeholders.

Conclusions

Implementation research targeting LBP appears to be a young field, mostly focusing on training and educating stakeholders in primary care. Outcomes on sustainability and penetration of evidence-based interventions are lacking. There is a need for implementation research guided by established frameworks that consider interrelationships between organizational and system contexts beyond the clinician–patient dyad.

Keywords: Low Back Pain, Implementation, Guidelines, Policy, Models of Care, Health Care System

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the main cause of years lived with disability worldwide [1]. Although LBP has been traditionally categorized as acute, subacute, or chronic, it has become more apparent that, for most, LBP is a long-term condition that rarely resolves without recurrences or flares [2–5]. Whenever symptoms worsen, individuals with LBP can face difficulties, such as limitations to normal activities [6, 7], emotional disturbances [8, 9], and productivity losses [7, 10], leading to repeated care-seeking and time taken off work [11, 12]. This individual burden often incurs high costs and collectively leads to a major economic burden. In Australia, costs exceed $4.8 billion every year [13], with most of the costs being attributed to individuals with long-term symptoms [14].

At a systems level, the ongoing nature of LBP also imposes challenges. Health care systems have traditionally focused on curative approaches and are currently underprepared to deliver preventive care, integrated care, and management of long-term health issues [15]. For instance, integrated care for people with persistent LBP delivered through the Australian Chronic Disease Management Program (publicly funded subsidy for specialist and allied health services for people with two or more chronic health conditions) is limited to only five visits per annum per patient, shared across all allied health services [16]. Another important challenge is the need for longer and person-centered consultations to address the complexities associated with LBP, particularly for those who are strongly impacted by social determinants of health, have disabling symptoms, or have a range of comorbidities [16]. These system challenges (i.e., siloed practices, funding streams) compromise clinicians’ ability to manage LBP through an evidence-based biopsychosocial approach [17–20]. Additionally, current funding arrangements underpin a challenging evidence–policy–practice paradox in Australia, where guideline-discordant care, such as radiofrequency denervation and spinal fusion, continues to be funded, while guideline-supported care, such as supervised exercise programs, receives limited funding [16].

Although guidelines recommend the use of evidence-based strategies to improve LBP management, such as risk stratification [21, 22], pain education [23–25], and exercise [26, 27], how and for whom these interventions can be effectively implemented in challenging and dynamic real-world contexts remains largely unknown. Accordingly, implementation research is an essential tool that can provide insights about methods to support the uptake or adoption of evidence-based interventions by providers and systems of care to improve health care [28]. Implementation studies can examine how certain strategies influence the use of the targeted practice or treatment, in particular how these practices can be used and embedded into routine care to improve services and patient outcomes [29]. Within this context, a greater understanding of implementation studies targeting LBP is essential to ensure best practice and policy that supports the improvement of patient outcomes in real-world contexts [29]. Notably, implementation research can also be useful to enable a greater understanding of why change has been so difficult to embed at the systems level, particularly when barriers and facilitators are considered.

Although implementation research has progressed in recent years, most effective interventions are never adopted routinely in clinical practice [30, 31]. Health service leaders have recently started to focus their attention on facilitating the uptake of research findings into routine care to improve both service and patient outcomes [32]. Although there are several systematic reviews on the clinical efficacy of interventions for LBP, implementation findings are only beginning to emerge in the LBP field. For instance, to our knowledge, only two reviews have examined implementation studies for LBP care [29, 33], and both considered only randomized controlled trials. However, many studies that evaluate strategies use case studies and qualitative and mixed-methods methodologies, which are necessary to understand context. Another important limitation of previous reviews of implementation studies targeting LBP is that most of the included studies were not conducted in Australia. As implementation is influenced by the systems in which it occurs [34], it is crucial to review implementation studies conducted locally to promote advances in practice and policy within the Australian context. To the best of our knowledge, the present review is the first review to scope implementation initiatives addressing LBP undertaken within the Australian health care system that includes both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. The overall aim of this scoping review is to comprehensively review implementation studies that targeted LBP care and aimed to put into use or integrate evidence-based interventions within an Australian setting [35]. Our specific aims are threefold:

To map implementation strategies that have been studied in Australia to address LBP prevention, care, and management to identify the contexts in which these are investigated and their outcomes.

To identify implementation frameworks, models, or theories that the implementation strategies are based upon or that are used to assess implementation outcomes.

To ascertain the barriers and facilitators to successfully implementing these strategies within the Australian health care system.

Methods

Design

We conducted a scoping review following the guidance of methodology developed by members of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and Joanna Briggs Collaborating Centres [36]. The review is reported in alignment with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [37] (Supplementary Data Additional File 2). Although not published, a study protocol was developed before the searches were undertaken.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with an academic liaison librarian and included keywords such as “low back pain OR synonyms (e.g., back pain)” AND “implementation OR synonyms (e.g., evidence utilization)” AND “Australia OR synonyms (e.g., Queensland)” (see example in Supplementary Data Additional File 1). Searches were conducted in May 2021 in the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, CINAHL, and Web of Science. Search terms were adapted for use according to database-specific filters. No year restrictions were applied. A systematic online search of the gray literature was also conducted and is described elsewhere [38].

Inclusion Criteria

Types of Participants

This scoping review included a range of participants: 1) individuals who experience LBP (≥75% of the sample), 2) clinicians who worked with individuals with LBP, and 3) the wider community.

Concept

The concept of interest in this review is implementation studies targeting LBP care in Australia. Here, we used Rabin et al.’s definition of implementation [35], i.e., putting to use or integrating evidence-based interventions and practices that aim to improve LBP in Australian health system settings. Studies were considered eligible if they sought to understand or measure at least one of the nine implementation strategies identified in the cluster labels from Waltz et al. [39] and Powell et al. [40] (see Table 1), as well as at least one of the eight implementation outcomes from to Proctor et al.’s taxonomy of implementation outcomes [41] (see Table 2). We used this definition and these taxonomies because they are well established in the implementation field.

Table 1.

Implementation strategies and their descriptions (adapted from Waltz et al. [2015] [39] and Powell et al. [2015] [40])

| Implementation Strategies | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Adapt and tailor to the context | Adapting and tailoring the innovation to meet local needs or to address barriers and leverage facilitators that were previously identified. |

| Change infrastructure | Changing legislation models, record systems, location of clinical service sites, or physical structure of facilities or equipment. |

| Develop stakeholder interrelationships | Identifying and building on existing relationships and networks within and outside the organization; promoting information sharing, collaborative problem-solving, and a shared vision/goal; identifying and preparing champions; organizing implementation team meetings. |

| Engage consumers | Engaging or involving patients/consumers and families in the implementation effort; preparing patients/consumers to be active in their care (e.g., by asking questions, by inquiring about guidelines and evidence behind clinical decisions or available evidence-supported treatments); using mass media. |

| Provide interactive assistance | Supporting implementation issues through interactive problem-solving and/or supportive interpersonal relationships; developing and using a system to deliver technical assistance; providing clinicians ongoing supervision; providing training for clinical supervisors; developing and using a system to deliver technical assistance. |

| Support clinicians | Supporting clinical staff through discussions (e.g., giving them time to reflect on and share lessons learned); developing reminder systems to help clinicians to recall information or prompt them to use the clinical innovation; providing real-time data about key measures of process/outcomes through the use of integrated models/channels of communication in a way that promotes use of the targeted innovation; revising professional roles; creating new clinical teams; facilitating relay of clinical data to providers. |

| Train and educate stakeholders | Providing written or oral training by conducting ongoing training, providing ongoing consultation, conducting educational meetings, or shadowing other experts; developing and distributing educational materials. |

| Use financial strategies | Changing billing systems, fees, reimbursement policies, incentives, or disincentives or using capitated payments. |

| Use evaluative and iterative strategies | Planning and conducting the implementation process through activities such as assessing for readiness, identifying barriers and facilitators, auditing and providing feedback (summarizing clinical performance data and sharing it with clinicians), and obtaining and using patients’/consumers’ feedback. |

Table 2.

Implementation outcomes and their definitions (adapted from Proctor et al. [2011] [41])

| Implementation Outcomes | Level of Analysis | Implementation Stage | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | Provider, consumer | Early, ongoing, late | The perception among implementation stakeholders that a given treatment, service, practice, or innovation is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory. |

| Adoption | Provider, organization, or setting | Early to mid | The intention, initial decision, or action to try or to use an innovation or an evidence-based practice. |

| Appropriateness | Provider, consumer, organization, or setting | Early (i.e., before adoption) | The perceived fit, relevance, or compatibility of the innovation or evidence-based practice for a given practice setting, provider, or consumer; or the perceived fit of the innovation to address a particular issue or problem. |

| Cost | Provider or providing institution | Ealy, mid, late | The cost impact of an implementation effort. |

| Feasibility | Provider | Early (i.e., during adoption) | The extent to which a new treatment or an innovation can be successfully used or carried out within a given agency or setting (e.g., participation rates for the program, retention). |

| Fidelity | Provider | Early to mid | The degree to which an intervention was implemented as it was prescribed in the original protocol or as it was intended by the program developers. |

| Penetration | Organization or setting | Mid to late | The integration of a practice within a service setting and its subsystems. |

| Sustainability | Administrators, organization, or setting | Late | The extent to which a newly implemented treatment is maintained or institutionalized within a service setting’s ongoing, stable operations. |

Context

In alignment with our aim to map implementation initiatives that have targeted LBP care in Australia, there were no restrictions on the context in which these occurred. Studies conducted in any Australian health system setting were considered in this scoping review (e.g., primary care, tertiary care, or community).

Types of Evidence Sources

We considered studies published in peer-reviewed journals, and we did not restrict our eligibility criteria by methodological design. All studies that used a systematic approach to measuring and understanding implementation strategies were included.

Study Selection

The results were exported into an EndNoteX9.0 (© 2022 Clarivate, United States) database, and duplicates were removed. Results were then uploaded to a screening platform, Covidence (© 2022 Covidence, Australia). Three independent reviewers (NC, SP, and SS) worked in pairs and screened all titles and abstracts for potential inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with author FMB. Full texts of all potentially eligible studies were evaluated for inclusion by three reviewers (NC, SP, and SS), who also worked in pairs in the full-text screening phase. We excluded articles that were not conducted in Australia, clinical commentaries, editorials, letters, and abstracts. Studies that sought to investigate an implementation strategy targeting musculoskeletal symptoms were included only if at least 75% of service users had LBP.

Data Synthesis and Presentation

After study selection, one reviewer (NC) extracted the following data from included studies: authors, year of publication, study aim, study design, setting where the study was conducted, Australian state of origin, stakeholders involved, implementation framework, model or theory, implementation strategy, implementation outcome, barriers and/or facilitators (if available), and patient and/or service outcomes (if available). During the extraction of the data on implementation strategies, the strategies described by the authors were matched to the categories described by Waltz et al. [39] and Powell et al. [40] (see Table 1) and classified accordingly (e.g., “develop educational materials” was classified as “train and educate stakeholders”). Likewise, outcomes described by authors were translated into the implementation outcomes described by Proctor et al. [41] (see Table 2) (e.g., “perceived usefulness of the program” was classified as “acceptability”). A second reviewer (ABA) reviewed the data extraction, and in case of disagreement, consensus was reached by discussion with a third reviewer (CHS). As the purpose of the present scoping review was to provide an overview of existing evidence regardless of methodological quality or risk of bias, we did not conduct a critical appraisal of included studies [42].

Results

Included Studies

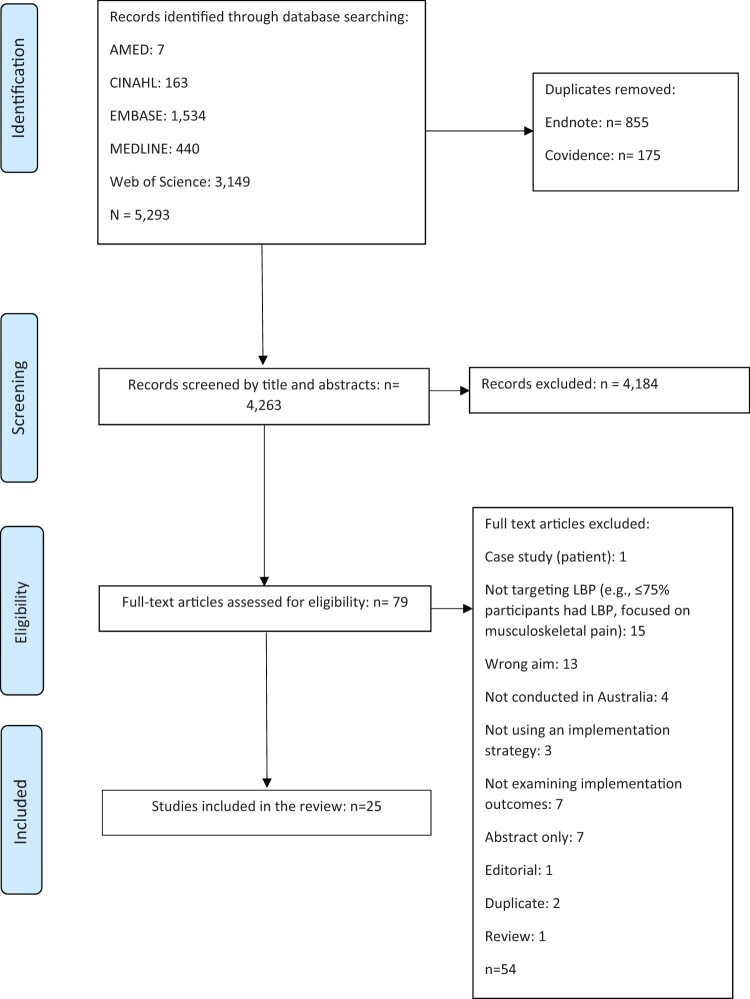

A total of 5,293 studies were initially identified. After removal of duplicates (n = 1,030) and screening of titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria, 25 studies met the inclusion criteria, as shown in Figure 1. Included studies are described in Table 3.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 3.

Summary of included articles

| Author (Year) Study Design Location | Setting (n) Stakeholders Involved (n) | Study Aim | Implementation Framework, Model, or Theory | Implementation Strategy (See Table 1 for Descriptions) | Implementation Outcome (Outcome Measurement) (See Table 2 for Definitions)* |

Barriers/ Facilitators |

Recommendations and Patient or Service Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

To explore the views of pharmacists on the implementation of LBP disease state management service in the pharmacy | NR |

|

Appropriateness (open-ended questionnaire): Pharmacists felt that implementing an LBP management service would be very beneficial for patients and that ultimately it would save long-term damage and costs associated with LBP |

|

|

|

To evaluate the impact of a PLTC on waiting times for the first appointment, patient attendance, surgery conversion rates, and GP satisfaction | NR |

|

Acceptability (surveys): 62% of GPs agreed or strongly agreed that feedback received from the PLTC was clear, precise, and received promptly; 87% of GPs believed their patients received appropriate management in the PLTC; 69% of GPs felt the waiting time for the PLTC was appropriate | Barriers: Existing allied health funding scheme and the lack of availability of publicly funded nonsurgical care in the community | Service outcomes: 71% of patients were removed from the orthopedic waiting list without ever having seen an orthopedic consultant. Waiting times in both spinal and general orthopedic clinics decreased after the PLTC was introduced. In the general orthopedic clinic, the mean waiting time decreased by 11%, and in the spinal orthopedic clinic by 25% | |

|

To evaluate the effectiveness of a population-based intervention designed to alter beliefs about back pain, influence medical management, and reduce disability and workers’ compensation–related costs. | NR | Engage consumers (mass media) | Adoption (GPs) ‡ (simulated clinical practice): Over time, the GPs in VIC were 2.51 times as likely not to order tests for acute LBP and 0.40 times as likely to order lumbosacral radiographs than GPs in NSW. They also were 0.48 times as likely to prescribe bed rest and 1.65 times as likely to advise work modification than their interstate colleagues. Similar changes were seen for subacute LBP. | NR | ||

|

To evaluate the effectiveness of a population-based, state-wide public health intervention designed to alter beliefs about back pain, influence medical management, and reduce disability and costs of compensation. | NR | Engage consumers (mass media campaign) | Adoption ‡ (Workcover claims database): The number of claims for back pain reduced by 15%. Over the duration of the campaign, there was an absolute reduction in medical costs of 20% per claim. | NR | ||

|

|

To measure the magnitude of any sustained change in GPs’ beliefs and stated behavior about back pain 4.5 years after cessation of a media campaign designed to alter population back pain beliefs. | NR | Engage consumers (mass media campaign) | Sustainability: Compared with baseline, VIC GPs were 2.0 times as likely to know that patients with LBP do not need to wait to be almost pain free to return to work (95% CI: 1.3 to 3.0); 1.7 times as likely to know that patients with acute LBP should not be prescribed complete bed rest until pain goes away (95% CI: 0.9 to 2.9). VIC GPs also reported being less likely to order tests for LBP because patients expected them to (OR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.2 to 2.6). | ||

|

To investigate the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to implement guideline recommendations for LBP in the ED (e.g., reduce lumbar imaging and opioid use in the ED, opioid use). | Knowledge to Action Framework |

|

Adoption ‡ (hospital’s electronic medical record): The data did not provide clear evidence that the intervention reduced lumbar imaging (OR = 0.77; 95% CI: 0.47 to 1.26; P = 0.29), referrals for advanced lumbar imaging (i.e., CT or MRI) (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.57 to 2.35), or prescription of strong opioid medicines (OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.46 to 1.04). However, the intervention reduced opioid use in EDs by 12.3% (OR = 0.57; 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.85; P = 0.006). | NR | Patient outcomes: At 1 week after ED discharge, there was no difference in pain intensity (MD = 0.04, 95% CI: –1.00 to 1.08), physical function (MD = 0.96, 95% CI: –0.92 to 2.83), quality of life (MD = 0.17, 95% CI: –0.25 to 0.58), or patient satisfaction with emergency care (MD = 0.16, 95% CI: –0.72 to 1.03) between the intervention and usual care groups. The authors observed similar results at 2 and 4 weeks after ED discharge. | |

|

|

To develop a CDSS to guide first-line care of LBP in the community pharmacy and evaluate the pharmacist-reported usability and acceptance of the prototype system. | NR |

|

|

Barriers: Using the app in front of patients, narrowing the amount of medicine that could be recommended and sold | Recommendation: Tool needs refinement. |

|

|

|

NR |

|

Acceptability (interviews, questionnaires): The PRISM approach was well received by participants and viewed as a valuable professional development opportunity. Participants reported that PRISM increased their confidence with managing patients with LBP. Reported changes to practice reported included improvements in communicating with and educating patients about contemporary pain science and its application within a private physiotherapy practice context. |

|

Recommendation: Suggested improvements included simplifying and streamlining data collection tools; further training focused on how to use the tools in practice, including simulated examples; providing electronic versions of forms and tools; and setting up automated reminders to collect patient data. |

|

|

To test the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a theory-informed intervention for implementing two behaviors recommended in a clinical practice guideline for acute LBP in general medical practice: decrease imaging referrals and increase providing advice to stay active. | Theoretical Domains Framework | Train and educate stakeholders (conduct educational meetings [workshops including didactic lectures, small group discussions, and activities], distribute educational materials) | Adoption ‡ (referral for imaging measured through Medicare imaging data): Incidence rate ratios of referral in the intervention group compared with the control were 0.83 (95% CI: 0.61 to 1.12) for x-ray, 0.92 (95% CI: 0.66 to 1.27) for CT scan, and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.68 to 1.10) for x-ray or CT scans. | NR | |

|

|

This study aimed to evaluate the fidelity of the IMPLEMENT intervention by assessing: 1) observed facilitator adherence to planned BCTs; 2) comparison of observed and self-reported adherence to planned BCTs; and 3) variation across different facilitators and different BCTs. | Bellg (2004) [41] Intervention Fidelity Framework | Train and educate stakeholders (conduct educational meetings [workshops including didactic lectures, small group discussions, and activities], distribute educational materials) | Fidelity (workshop transcripts, self-reported adherence): The observed adherence to planned BCTs across all workshops was 79% overall, ranging from 33% to 100% per session. The BCT provide information on consequences had the lowest fidelity (70%), and information provision had the highest (97%). Sensitivity of self-reported adherence was 95% (95% CI: 88 to 98), and specificity was 30% (95% CI: 11 to 60). There was no significant difference in adherence to BCTs between the facilitators. | NR | |

|

|

To develop an implementation intervention aiming to reduce non-indicated imaging for LBP by targeting both GP and patient barriers concurrently. | The Behaviour Change Wheel, Theoretical Domains Framework |

|

|

|

|

|

To improve LBP care in an Australian Aboriginal Primary Health Service provided by GPs; reduce inappropriate LBP radiological imaging referrals, increase psychosocial-oriented patient assessment, and increase the provision of LBP self-management information to patients. | Theoretical Domains Framework |

|

|

|

||

|

|

To report on the design, implementation, and evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of the Back pain Assessment Clinic (BAC) model of care. | Victorian Innovation Reform Impact Assessment Framework |

|

|

Facilitators: Funding from the Department of Health and Human Services, cooperation and good will from stakeholders | |

| Primary care GPs (19,997) | To evaluate the effectiveness of the 2013 NPS MedicineWise LBP program at reducing x-ray and CT scans of the lower back, as well as the financial costs and benefits of the program to the Australian Government Department of Health | NR |

|

|

NR | ||

|

|

To determine the cost- effectiveness of a multifaceted and theory-informed intervention: the IMPLEMENT intervention, for implementing a clinical practice guideline for acute LBP in general medical practice in VIC, Australia. | Not applicable (IMPLEMENT was underpinned by Theoretical Domains Framework, though) | Train and educate stakeholders (conduct educational meetings [workshops including didactic lectures, small group discussions, and activities], distribute educational materials) |

|

NR | Findings do not support a wider rollout of the IMPLEMENT intervention. |

|

|

To determine whether a CDSS for LBP management had the potential to support GPs to diagnose and manage LBP according to guidelines, and to identify barriers to and enablers of uptake | NR |

|

|

|

Recommendation: Tool needs refinement. |

|

To investigate the feasibility and clinical utility of implementing a novel, evidence-informed, interdisciplinary group intervention—Mindfulness-Based Functional Therapy—for the management of persistent LBP in primary care. | NR | Engage consumers (mindfulness intervention) | Acceptability (questionnaire): 85% of participants were highly satisfied with Mindfulness-Based Functional Therapy. | NR | ||

|

|

To evaluate community responses to a public health campaign designed for health service waiting rooms that focuses on the harms of unnecessary diagnostic imaging for LBP. | Behavioral economics |

|

|

Barriers: Strong community beliefs in favor of diagnostic imaging, skepticism about overdiagnosis, and anger at the concept of reducing testing could all be barriers to an effective campaign to reduce overuse of imaging. | Recommendation: Messages should be revised. |

|

|

To evaluate the effectiveness of an interdisciplinary evidence-based practical education program designed to upskill primary care physicians managing patients with LBP. | Policy into Practice Framework | Train and educate stakeholders (conduct educational meetings [6.5-hour single-day program and access to a web-based repository]) | Adoption ‡ (clinical practice behavior [patient vignette]): The majority of respondents who were guideline inconsistent for work and bed rest recommendations before the intervention gave guideline-consistent responses after the intervention (82% and 62%, respectively). For exercise recommendations, the results were less conclusive, with a smaller proportion (39%) of respondents changing from consistent to consistent. | Barriers: Consultation time constraints for complex pain problems and lack of funding for integrated interprofessional care | |

|

To deliver and evaluate the effectiveness of a modified Self Training Educative Pain Sessions program (mSTEPS) to consumers with persistent LBP living in geographically isolated areas of WA. | NR | Engage consumers | Acceptability (questionnaire): Immediate post-intervention evaluation has shown that 86.4% consumers rated mSTEPs as useful (NRS: 7 to 10), with a small proportion (9.1%) indicating that the intervention was moderately useful (NRS: 4 to 6) and only 2 consumers (4.5%) rating the intervention as not that useful (NRS: 0 to 3). | NR |

|

|

|

|

To determine the effectiveness and the perceived usefulness of a pamphlet intervention targeting LBP-related beliefs. | Community Practice Framework | Train and educate stakeholders (LBP pamphlet and education) |

|

NR | Patient outcomes: There were no significant changes in work-related fear or back beliefs in any of the three groups (usual care, pamphlet only, pamphlet and education) at 2 and at 8 weeks. There was a statistically significant decrease in physical activity–related fear at 2 weeks in the control (usual care) group (21.3, 95% CI: 22.4 to 20.2) but not in the pamphlet-only group (21.3, 95% CI: 22.8 to 0.3) or the pamphlet-with-education group (0.0, 95% CI: 21.4 to 1.4). |

|

|

To trial the implementation of a health care provider pain education program (hPEP) and evaluate the short-term effectiveness in improving the self-reported evidence-based management of LBP by primary care providers in rural areas of WA. | Policy into Practice Framework | Train and educate stakeholders (conduct educational meetings [educational program]) |

|

NR | |

|

|

To develop a care pathway to link acute and community health services for patients with LBP presenting in an acute setting. | NR |

|

Appropriateness (consultation with staff): Agreement on 1) the need for developing a new care-coordinator role, which would support a greater focus on integration between acute and community sectors for patients with LBP; 2) the need to screen at-risk patients; and 3) implementation of the Service Coordination Tool Templates as a system of referral across the acute and community settings. | Barriers: Funding for the care coordinator role, redefining roles, supporting staff to develop effective strategies to enhance communication, collaboration and coordination of services | Recommendations: Engage relevant stakeholders through a variety of communication strategies, obtain feedback on model from key external agencies, pilot the model, and obtain consumer and staff feedback before full implementation. |

|

|

To explore views of GPs and patients on three communication tools to support delayed prescribing of imaging for LBP before distribution of the tools to GPs. This investigation was commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Health. | NR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

To evaluate physiotherapists’ feedback on a list of Choosing Wisely recommendations that were sent to members of the Australian Physiotherapy Association before the final recommendations were endorsed and distributed. | NR |

|

Appropriateness (survey): 52.3% agreed that physiotherapists should not use electrotherapy modalities in the management of patients with LBP, and 25.4% disagreed. For responses that suggested disagreement, codes included: electrotherapy is appropriate to use as an adjunct to evidence-based practice (30%), clinical experience is more valuable than evidence (28.3%), and blanket rules are inappropriate (28.3%). | Barriers: Recommendations do not consider clinical reasoning or experience. Some expressed that there will always be exceptions to practice recommendations, such as patient preferences and fear of missing an important diagnosis. | Recommendation: Wording of recommendations needs to be refined. |

BBQ= Brunnsviken Brief Quality of life scale; BCT= behavior change technique; CI= confidence interval; CT= computed tomography; ED= emergency department; MD= mean difference; MRI= magnetic resonance imaging; NR= not reported; NRS= numeric rating scale; NSW= New South Wales; OR= odds ratio; PLTC= physiotherapy-led triage clinic; SA= South Australia; SD= standard deviation; VIC= Victoria; WA= Western Australia.

Study outcomes were identified on the basis of Proctor’s taxonomy for implementation outcomes. The outcome classifications reported here do not necessarily correspond to the wording authors used to refer to the outcomes they assessed.

Studies reported on outcomes other than implementation outcomes, but only the implementation outcomes are reported in the table (along with patient and service outcomes, if available).

Where multiple adoption outcomes were reported in the article, only one outcome was reported in the table on the basis of the following hierarchy: 1) objective measures of behavior, 2) self-reported behavior, and 3) self-reported attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs.

The tool assessed here was the same used in Peiris (2014).

Characteristics of Included Studies

Year of Publication

The included studies were published between 2001 and 2021, with most of them published in the past 5 years (n = 11, 44%), nine (36%) published 5–10 years ago, and five (20%) published more than 10 years ago.

Study Designs

The designs of included studies are described in Table 3. Most study designs were observational (n = 9, 36%). In terms of methods, most studies (n = 16, 64%) used quantitative methods exclusively, seven (28%) used qualitative methods exclusively, and two (8%) used mixed methods.

Study Locations and Settings

Of the 25 included studies, three were conducted in multiple health care settings across Australia, nine in Victoria (36%), six (24%) in New South Wales, six (24%) in Western Australia, and one in South Australia (4%). Most studies were conducted in primary care settings (n = 13, 52%), followed by tertiary care (n = 4, 16%) and the wider community (n = 4, 16%). Three (12%) studies were conducted in community pharmacies, and only one (4%) study targeted both primary and tertiary care settings.

Stakeholders Involved

The range of stakeholders varied across studies, with general practitioners (GPs), physiotherapists, and pharmacists being most commonly involved as clinician stakeholders—in 12 (48%), five (20%), and four (16%) studies, respectively. Consumers or patients were involved in nine studies (36%).

Use of Implementation Framework, Model, or Theory

Only 40% of the included studies (n = 10) reported the use of a framework, model, or theory to guide the study or structure the analysis. The most commonly used framework was the Theoretical Domains Framework [43–45]. The Theoretical Domains Framework provides a theoretical lens through which to view the cognitive, affective, social, and environmental influences on behavior and was used in three studies [46, 47]. Other frameworks from the implementation field and other fields were used and included the Behaviour Change Wheel model [45], the Knowledge to Action Framework [48], Bellg et al.’s Intervention Fidelity Framework [49], the Victorian Innovation Reform Impact Assessment Framework [50], behavioral economics [51], the Policy into Practice Framework [52, 53], and the Community Practice Framework [54].

Categories of Implementation Strategies

The categories of implementation strategies most frequently used were evaluative and iterative strategies (n = 14, 56%) and train and educate stakeholders (n = 13, 52%), followed by engage consumers (n = 6, 24%), develop stakeholder relationships (n = 4, 16%), change in infrastructure (n = 4, 16%), and support clinicians (n = 3, 12%). The strategies adapt and tailor to the context, provide interactive assistance, and use financial strategies were not considered in any of the included studies. None of the studies used strategies that did not fit into the categories developed by Waltz et al. [39] and Powell et al. [40].

Use Evaluative and Iterative Strategies

Of the 25 studies included, 14 reported using a range of evaluative and iterative strategies. Most studies that used evaluative and iterative strategies were qualitative studies (n = 8, 57%). Four studies used observational designs (29%), one study used mixed methods (7%), and one used an experimental design (7%). Five studies focused on the assessment of the following: readiness, barriers and facilitators to using a clinical decision support system (CDSS) [55, 56], agreement with evidence-based guideline recommendations [57], implementing a care program for people with acute LBP in the community pharmacy [58], and implementing an intervention to reduce imaging for LBP [45]. Five studies sought to obtain feedback from key stakeholders on the following: tools to delay diagnostic imaging [59], a public health campaign aimed at reducing unnecessary imaging [60], an iterative educational implementation program for clinicians [61], a back pain assessment clinic [62], and a physiotherapy-led triage clinic [63]. Two studies provided audit and feedback data to clinicians with regard to their LBP practice [44, 64], with one of them providing data on department-level imaging, opioid, and inpatient admission rates [64]. One study reported on consultations with staff members to identify central areas of concern and needs that could be addressed by developing a care pathway [65].

Train and Educate Stakeholders

Of the 25 studies included, 13 reported training and educating clinicians about evidence-based LBP management. Of the 13 studies that used a strategy within this category, eight provided training and distributed educational materials [43, 44, 52, 61, 64, 66–68], three developed educational materials [45, 57, 59], one provided training [53], and one distributed educational materials [69]. The designs of the studies in which the strategy train and educate stakeholders was used were mostly observational (n = 5, 38%), followed by experimental (n = 3, 23%) and qualitative (n = 4, 31%). One study was an economic evaluation conducted alongside a trial.

Training and Distribution of Educational Materials. French et al. [43, 66] and Mortimer et al. [68] reported on implementation findings of the IMPLEMENT trial, where GPs in the intervention arm received educational materials (DVDs, electronic resources) and attended two educational workshops, each of 3 hours’ duration. Workshops’ content included patient assessment and how to make behaviorally specific guideline recommendations about imaging referrals and advice to stay active [70].

Slater et al. [52] reported on the delivery of a 6.5-hour health care provider pain education program targeting primary care physicians. Workshop content included guidelines for acute and chronic nonspecific LBP, medical options, movement, response to pain, and pharmacological approaches to LBP. Primary care physicians were offered access to course materials and evidence-based LBP updates [52].

Coombs et al. [64] targeted clinicians (medical officers, nursing staff, and physiotherapists) who worked in emergency departments through educational seminars that focused on skills for assessing, managing, educating, and referring patients according to a model of care for acute LBP. They also distributed educational materials, such as a hard copy of the model-of-care document, a website and decision support tools for appropriate use of lumbar imaging and analgesic medicines, posters displayed across the emergency departments, and patient handouts.

The Practice-Based Innovation and Implementation System (PRISM) targeted the education of physiotherapists through three workshops and seven discussion forums [61]. PRISM’s content was tailored to acute and subacute LBP and included three core components: education and training (contemporary education strategies to optimize biological and clinical knowledge and skills in pain care), clinical pathways and collaborative innovation (e.g., risk stratification, avoiding unnecessary imaging and medication, pain education), and high-reliability management and learning systems (e.g., electronic clinical decision-making systems, mentoring). Educational materials, such as Explain Pain [71], Explain Pain Supercharged [72], and Painful Yarns [73], were shared with clinicians as part of the training.

Lin et al. [44] delivered two 3-hour educational workshops to GPs working in rural Australian Aboriginal Medical Services. Workshops’ content included the epidemiology of LBP, the biopsychosocial model of LBP, imaging findings, guideline recommendations, clinical tools, and how to advise patients. Two clinical tools were also distributed among clinicians: the STart Back tool [21] and an LBP decision-making tool designed for primary care [74].

Slater et al. [67] sought to improve consumers’ LBP-related beliefs through the use of pamphlets that provided evidence-based information about the management of LBP, such as the need to stay active, stay positive, and stay engaged at work and socially. To achieve such goals, the authors trained pharmacists to provide advice in accordance with the pamphlets’ content. Pamphlets were delivered to consumers in community pharmacies, with or without educational information provided by a pharmacist.

Development of Educational Materials. Jenkins et al. [45] reported the development of a training session for GPs and educational resources (educational booklet for GPs to use with patients during an LBP consultation), in which feedback from GPs and health consumers was incorporated. Zadro et al. [57] sought physiotherapists’ feedback on a list of guideline-based recommendations before final recommendations were endorsed and distributed. Likewise, Traeger et al. [59] sought input from GPs and patients on three newly developed communication tools that were aimed at supporting delayed prescribing of diagnostic imaging.

Training. Slater et al. [53] reported on the delivery of a 6.5-hour health care provider pain education program targeting clinicians across disciplines (e.g., GPs, nurses, physiotherapists, psychologists). Of the eight studies (reporting on six interventions) that reported providing training to clinicians [43, 44, 52, 53, 61, 64, 66, 68] (either combined with the distribution of educational materials or not), only six reported on the length of training for four interventions [43, 44, 52, 53, 66, 68], which ranged from two 3-hour workshops to a 6.5-hour single-day workshop.

Distribution of Educational Materials. The NPS MedicineWise LBP educational program targeted GPs and consisted of the distribution of a range of educational materials, including an online decision support tool to reduce inappropriate ordering of computed tomography scans and x-rays, a symptom self-management prescription pad, patient information sheets, and feedback data on imaging referral, accompanied by educational messages [69].

Engage Consumers

Six of the 25 studies engaged with patients/consumers. Four studies reported on the engagement of consumers through mass media campaigns [60, 75–77], with three experimental studies reporting on the campaign “Back pain: don’t take it lying down” [75–77] and one qualitative study evaluating community responses to a public health campaign focused on the harms of unnecessary diagnostic imaging for LBP. Two observational studies engaged with consumers as part of an implementation effort to implement a Self-Training Educative Pain Sessions Program [78] and a Mindfulness-Based Functional Therapy program [79].

Develop Stakeholder Interrelationships

Four of the 25 studies attempted to develop stakeholder relationships as a strategy in various ways: by improving referral pathway options from hospital settings to outpatient services (e.g., physiotherapy) [64]; implementing meetings during which a rheumatologist, a neurosurgeon, and an orthopedic spinal surgeon met fortnightly to triage new referrals for spinal pain to either the back pain assessment clinic or the appropriate outpatient specialist clinic [62]; promoting a CDSS via a network of facilitators, aligning its promotion with the National Pain Week, and using media [55]; and improving coordination of care by establishing effective working relationships among professionals and across health services through a new coordinator role [65]. The designs of the studies that used the strategy develop stakeholder interrelationships varied: one used action participatory research (25%), one used mixed methods (25%), one used an observational design (25%), and one used an experimental design (25%).

Change in Infrastructure

Four of the 25 studies used change in infrastructure as a strategy, which included the development of a model of care [65], the establishment of a physiotherapy-led triage clinic for LBP [63], and the development and establishment of a back pain assessment clinic [62]. One study sought to explore the pharmacists’ views on the implementation of a new LBP disease state management service in the pharmacy [58]. Among the studies that used change in infrastructure as a strategy, two were qualitative studies, and two used observational designs.

Support Clinicians

Two of the 25 studies sought to support clinicians through a CDSS in an attempt to prompt and remind clinicians to provide guideline-based care to patients/consumers [55, 56]. To assess the potential of the CDSS, Peiris and colleagues (2014) [55] used a mixed-methods study, whereas Downie and colleagues [56] used a qualitative design.

Implementation Outcomes

Implementation outcomes, how these were assessed, and related findings for each included study are summarized in Table 3. The number of implementation outcomes considered in each study ranged from one to four. The most common implementation outcomes assessed were acceptability (n = 11, 44%) [45, 53, 55, 56, 60–63, 67, 78, 79] and adoption (n = 10, 40%) [43, 44, 52, 53, 55, 64, 68, 69, 77, 80], followed by appropriateness (n = 7, 28%) [45, 56–60, 81]. Cost (n = 3, 12%) [62, 68, 69], feasibility (n = 1, 4%) [67], fidelity (n = 1, 4%) [66], and sustainability (n = 1, 4%) [76] were rarely assessed. Penetration was not assessed in any of the included studies. Various approaches were used to assess implementation outcomes, and a range of stakeholders was considered (see Table 3). For instance, 11 studies assessed acceptability through interviews [45, 55, 56, 60, 61], surveys [62, 63, 67], and questionnaires [53, 78, 79]. Of the 10 studies in which adoption was considered, five reported adoption outcomes derived from objective measures of clinicians’ behavior [55, 64, 69]. Four studies gathered adoption data from administrative data, such as Medicare Benefits Schedule data [69], hospital medical records [64], Medicare imaging data [43], and the electronic clinical records management system [44], and one study objectively measured visits to the website of the CDSS designed for GPs [55]. Four studies relied on outcome measures of clinicians’ behavior based on clinical simulations [52, 53, 80]. One study used data from a Workcover database claims setting [77].

Association Between Implementation Strategies and Implementation Outcomes

Although it was beyond the scope of the present review to assess the effect of implementation strategies on implementation outcomes, some insights can be drawn from the included studies. For instance, the strategy of training and educating stakeholders seems to lead to better implementation outcomes when used alongside other strategies [44, 64, 69] rather than alone [43]. Acceptability outcomes were generally positive regardless of the strategies considered (e.g., [45, 56, 61–63]), with two exceptions [55, 60]. Conversely, adoption seemed to be difficult to achieve, even when multiple strategies were used (e.g., [55, 64]). Notably, many of the studies that considered adoption aimed to increase the adoption of more than one behavior related to LBP management, with most of them improving adoption of at least one behavior, but not all [44, 52, 53, 64, 69], or showing nonsignificant adoption results [43, 68]. Interestingly, a mass media campaign seemed to improve adoption of guideline-aligned behavior [77, 80], reducing imaging and Workcover claims [77].

Reported Barriers

Eleven studies identified barriers to implementation of the proposed innovations to enhance evidence-based practice behavior in LBP care by using evaluative and iterative strategies. Barriers are presented according to the implementation strategies below.

Training and Educating Stakeholders

When discussing barriers to using an LBP management and education booklet, GPs highlighted time constraints, ability to conveniently store a hard-copy booklet and remember to use it, resource costs, length of electronic links, and the format (hard copy) [45]. From consumers’ perspectives, barriers to using this same resource included format (electronic, printed handouts), high levels of pain, and consumers’ perceptions that imaging might be needed [45].

Primary care physicians articulated consultation time constraints for complex pain problems and lack of funding for integrated interprofessional care as barriers to implementing what they learned in an interdisciplinary evidence-based practical education program for persistent LBP care [52]. Likewise, GPs highlighted locum staff, other GPs, teamwork availability, the format of clinical tools, recording practices (e.g., psychosocial care), and workers’ compensation as barriers to changing practices within the Australian Aboriginal Medical Service context [44].

GPs perceived tools designed to support delayed imaging for LBP as impractical and incompatible with patient-centered care [59]. They also perceived the dialogue sheet (a tool designed to support doctor–patient communication and joint decision-making) as redundant for experienced GPs and thought that using it would add time pressure within the consultation. GPs also perceived the concept of written prompts and co-signing an agreement with their patients when using the dialogue sheet as an insult to their clinical skill and autonomy.

Physiotherapists who participated in the PRISM educational program discussed time pressures and the quantity and length of the forms as the main barriers to using the tools with patients. Of note, physiotherapists also suggested improvements, such as simplifying and streamlining data collection tools, providing further training focused on how to use the tools in practice (including examples), providing electronic versions of the forms and tools, and setting up automated reminders to collect patient data. Some also suggested modifications to operational processes, such as patients completing forms in waiting rooms.

Engage Consumers

Consumers’ responses to a public health campaign aimed at reducing unnecessary diagnostic imaging for LBP also emphasized barriers to an effective campaign to reduce overuse of imaging, such as strong community beliefs in favor of diagnostic imaging, skepticism about overdiagnosis, and anger at the concept of reducing testing [60].

Change in Infrastructure

Stakeholders from both the acute and community sectors discussed redefining roles, providing funding for a care coordinator role, and supporting staff to develop effective strategies to enhance communication, collaboration, and coordination of services as challenges to implementing a new care pathway [65]. Similarly, Blackburn et al. [63] highlighted existing allied health funding schemes and the lack of availability of publicly funded nonsurgical care in the community as barriers to a physiotherapy-led triage clinic. Pharmacists’ perceived barriers to implementing a care program for people with acute LBP in community pharmacies included adequate staff training, remuneration, time, and patient proximity to the pharmacy [58].

Support Clinicians

According to GPs, barriers to using the CDSS tool included the complex nature of LBP, competing tools, the fact that the CDSS tool was not sufficiently dynamic, and the perception that the tool was condescending [55]. Likewise, pharmacists reported a negative sentiment about using the tool in front of patients, as well as the impact the tool could have on business interests (narrowing the range of medicine that could be recommended and sold) [56].

Reported Facilitators

Eight studies identified facilitators to the implementation of the proposed innovations to enhance evidence-based practice behavior in LBP care. Facilitators are presented according to the implementation strategies below.

Training and Educating Stakeholders

GPs considered that the use of an LBP management and education booklet could be prompted by using reminders [45]. They also considered it best to fill in the resource during consultation. Consumers perceived this same resource as time efficient to read and easy to refer to. Interestingly, consumers thought the resource would work best if it were individualized to them and that it would be most useful if the information were reinforced by the GP guiding them through it. Likewise, Traeger et al. [59] found that patients valued the written information provided in tools designed to support delayed prescribing imaging for LBP, including the signed agreement to delay testing, which was negatively received by GPs.

When discussing facilitators to change in an Australian Aboriginal Medical Service, GPs cited knowledge about radiology and mental health, educational workshops for new staff, teamwork on site, patient communication, funding models, processes for locum staff, audit, and feedback as important factors.

Physiotherapists who participated in the PRISM educational program mentioned the content expert involvement in discussion forums, clear screening/triaging processes, and user-friendly practice-based tools as factors that facilitated the integration of the PRISM model into practice [61].

Change in Infrastructure

Moi et al. [62] discussed funding from the Department of Health and Human Services, cooperation, and goodwill from stakeholders as facilitators to implementing the back pain assessment clinic model of care. Likewise, pharmacists highlighted that collaboration with allied health professionals and patients, as well as support from professional and government bodies, would be crucial to implement a care program for people with acute LBP in community pharmacies.

Discussion

This scoping review identified and synthesized 25 studies that reported implementation strategies and outcomes of initiatives targeting LBP care in Australia. Although the number of studies identified is substantial, implementation research targeting LBP care in Australia appears to be a young field, with most implementation research conducted in the past 5 years and focusing on evaluation and iterative strategies (often in the early phases of program development) and training and educating stakeholders. Most studies targeted primary and tertiary care, with only one study targeting different levels of care or services simultaneously. Research on changing infrastructure and supporting clinicians is limited, and the strategies interactive assistance, use of financial strategies, and adapting and tailoring to context have not been investigated to date. Of note, the latter has been shown to be an effective implementation strategy in previous reviews [82, 83]. The most common outcomes considered were acceptability and adoption, followed by appropriateness, costs, feasibility, and fidelity. Outcomes on penetration and sustainability of evidence-based interventions are lacking, despite being relevant to health care systems, where practices and services need to be ongoing and integrated into existing settings in order to offer continuous benefits to the public. Notably, only 10 of the 25 included studies reported implementation that was underpinned, guided by, or assessed with a framework, model, or theory. This is particularly important within the context of implementation research, as the use of these tools has been promoted to guide translation of research into practice and facilitate understanding of what influences outcomes [84]. Barriers commonly reported included time and funding constraints, inconvenience of using certain tools, the format of tools, funding, shortage of human resources, and human aspects, such as patients’ high pain levels and clinicians’ beliefs. Collaboration between stakeholders, teamwork, funding, support from professional and government bodies, training, and personalization of care were identified as facilitators. Taken together, these barriers and facilitators reinforce the importance of considering interrelationships between organizational and system contexts, beyond the clinician–patient dyad.

Implications for Research and Policy

Our findings indicate several priorities that should be addressed to improve implementation within the context of LBP care in Australian settings. First, we encourage researchers to use established theories, models, or frameworks for implementation to design and evaluate implementations in the future, as these are designed to address the research–practice gap [47, 85, 86]. Second, as stakeholders’ recommendations had a meaningful impact on some of the research identified in this review [55, 57, 60, 61, 65], we argue that it is valuable to consider stakeholder engagement in the early stages of implementation research. Third, as no studies specifically referenced established taxonomies for implementation strategies and outcomes, we recommend that future studies do so. Using established taxonomies within studies will promote methodological consistency [39–41], replicability, and evidence synthesis (e.g., systematic reviews, meta-analysis) [87] and improve understanding of how, why, when, and where implementation interventions work. Fourth, future research should consider reporting implementation costs. We identified only three studies that reported cost outcomes [62, 68, 69]. Such outcomes are essential in establishing sustainable services and models of care [88]. Cost concerns affect stakeholders’ willingness to implement interventions and are the most significant barrier to sustainability [89–91], with relevance to implementations that seek to offer ongoing benefits to LBP care. Fifth, there is a need for studies of large-scale implementation of interventions that have been shown to be successful in improving LBP outcomes, such as exercise programs [26, 92, 93] and multidisciplinary care [94–96]. Although multidisciplinary care is available in Australia, it is currently not well supported by existing funding models for primary care; therefore, the reliance on tertiary care remains high [97]. Consequently, wait times can extend to 3 years and beyond in some areas [97]. A potential way of overcoming such accessibility issues would be to extend the availability of multidisciplinary care or decentralize it from tertiary care settings—it has been suggested that doubling current levels of access to multidisciplinary care in Australia could deliver $3.7 million in savings while reducing absenteeism and improving well-being [98]. Within this context, interprofessional musculoskeletal models of care and extension of the scope of practice for allied health professionals (e.g., community-based multidisciplinary care, physiotherapy-led care) emerge as potential strategies that could be explored in future implementation research [99]. Lastly, future studies should consider using multiple implementation strategies to increase impact and ensure long-lasting changes.

Overcoming Financial Barriers to Implementation

Perhaps not surprisingly, funding was identified as both a barrier to implementation of guideline-aligned care when scarce, and a facilitator when available. A potential way to overcome financial barriers to implementation of guideline-concordant care is to use disinvestment—i.e., to withdraw health resources from health practices, procedures, technologies, or pharmaceuticals that are deemed to deliver little or no health gain for their cost and redistribute the funding to implement higher-value services [100, 101]. Within this context, implementation studies that use financial strategies such as capitated payments or changes in reimbursement policies are warranted. Likewise, implementation studies that consider cost outcomes could also provide insights on how to overcome financial barriers to implementation of guideline-aligned care for LBP. Addressing such gaps in Australia and other countries might be particularly important over the next few years, as the global economy is entering a period of pronounced slowdown [102]. The need to do more with fewer resources has increased across many health care systems worldwide, with relevance to exploring avenues to improve both efficiency and quality of LBP care.

Contextualizing Findings

The Australian health care system runs as a mixed model of public and private sectors [103]. Service providers and health professionals are largely funded by Australian Federal, State, and Territory governments, with support from private for-profit and not-for-profit sectors [104]. Medicare provides universal access to free public hospital care for all Australian citizens and subsidized access to other medical services (e.g., GPs) and medicines [103]. States are responsible for managing hospitals, health institutions, and health services through Primary Health Networks [105].

Although the Australian health care system performs well in comparison to health care systems in similar countries [106], it faces similar challenges to addressing LBP at a health care system level, including rising health expenditures over time [107], long waiting times [97, 108], excessively medical solutions (e.g., steroid injections, spinal surgery), and low access to multidisciplinary pain management and physical and psychological therapies [16]. Therefore, although it is not possible to extrapolate from the studies identified in the present review to implementation studies targeting LBP in other countries, our findings might be valuable beyond the Australian context. Likewise, the Australian context could benefit from learning how guideline-aligned care, models of care, and policies have been implemented in other countries, with relevance for the LBP research agenda more broadly.

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to map implementation initiatives targeting LBP care within the Australian health care system. We considered both quantitative and qualitative studies, with relevance to the comprehensiveness of our findings. We conducted this review using explicit and rigorous methods [36] and used established taxonomies for both implementation strategies [39, 40] and outcomes [41]. Nevertheless, this review has limitations that need to be considered. First, there are inconsistencies surrounding what constitutes an implementation study (i.e., definition, inclusion/exclusion criteria) [35, 109, 110]. We used Rabin et al.’s definition of implementation, and our findings could have been potentially different if another definition of implementation studies had been used. Second, not all included studies had implementation as their primary focus. Therefore, the implementation strategies and outcomes discussed here are based on our interpretation. Third, although patient and services outcomes have been identified in some of the included studies, it was beyond the scope of this review to elaborate on these aspects in detail. However, we briefly described them in Table 3, to give readers further relevant details. Finally, we attempted to screen widely and inclusively, but the indexing of studies in implementation is inconsistent, and therefore, it is possible that some eligible studies were missed.

Conclusion

Our review mapped various implementation strategies that have been used to promote the uptake of LBP guideline recommendations, policies, and models of care in the Australian health care system. We identified strategies that have not been explored (i.e., interactive assistance, adapting and tailoring to context, use of financial strategies) and the dearth of implementation studies assessing outcomes of sustainability and penetration, which are imperative to ensure ongoing benefits to LBP care. Lastly, we identified a need for theory-driven implementation studies. Likewise, implementation research integrating different levels of care or services was rare. Taken together, our findings suggest that implementation initiatives targeting LBP care in Australia are a key component of the research agenda to bridge this knowledge–practice gap. Future implementation research targeting LBP care could benefit from consideration of the interrelationships among interpersonal (e.g., clinician–patient), organizational, and system barriers and facilitators, as a greater understanding of these could help overcome the challenges to improving LBP care in Australia.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data may be found online at http://painmedicine.oxfordjournals.org.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Nathalia Costa, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney School of Public Health, Menzies Centre for Health Policy and Economics, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

Fiona M Blyth, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney School of Public Health, Menzies Centre for Health Policy and Economics, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Anita B Amorim, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, School of Health Sciences, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Sarika Parambath, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney School of Public Health, Menzies Centre for Health Policy and Economics, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Selvanaayagam Shanmuganathan, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney School of Public Health, Menzies Centre for Health Policy and Economics, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Carmen Huckel Schneider, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney School of Public Health, Menzies Centre for Health Policy and Economics, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Funding sources: This research is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia grant APP1171459 (NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence).

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low back pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73(6):968–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dunn KM, Campbell P, Jordan KP.. Long-term trajectories of back pain: Cohort study with 7-year follow-up. BMJ Open 2013;3(12):e003838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dunn KM, Hestbaek L, Cassidy JD.. Low back pain across the life course. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013;27(5):591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kongsted A, Kent P, Hestbaek L, Vach W.. Patients with low back pain had distinct clinical course patterns that were typically neither complete recovery nor constant pain. A latent class analysis of longitudinal data. Spine J 2015;15(5):885–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Itz CJ, Geurts JW, van Kleef M, Nelemans P.. Clinical course of non-specific low back pain: A systematic review of prospective cohort studies set in primary care. Eur J Pain 2013;17(1):5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Young AE, Wasiak R, Phillips L, Gross DP.. Workers’ perspectives on low back pain recurrence: “It comes and goes and comes and goes, but it’s always there”. Pain 2011;152(1):204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S.. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J 2008;8(1):8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tan D, Hodges PW, Costa N, Ferreira M, Setchell J.. Impact of flare-ups on the lives of individuals with low back pain: A qualitative investigation. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2019;43:52–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coole C, Drummond A, Watson PJ, Radford K.. What concerns workers with low back pain? Findings of a qualitative study of patients referred for rehabilitation. J Occup Rehabil 2010;20(4):472–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gedin F, Alexanderson K, Zethraeus N, Karampampa K.. Productivity losses among people with back pain and among population-based references: A register-based study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2020;10(8):e036638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wasiak R, Kim J, Pransky G.. Work disability and costs caused by recurrence of low back pain: Longer and more costly than in first episodes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(2):219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, et al. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: Inception cohort study. BMJ 2008;337(7662):a171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria. A Problem Worth Solving. Elsternwick, Victoria: Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Impacts of Chronic Back Problems. Canberra: AIHW; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Briggs AM, Dreinhöfer KE.. Rehabilitation 2030: A call to action relevant to improving musculoskeletal health care globally. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47(5):297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Traeger AC, Buchbinder R, Elshaug AG, Croft PR, Maher CG.. Care for low back pain: Can health systems deliver? Bull World Health Organ 2019;97(6):423–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zangoni G, Thomson OP.. ‘I need to do another course’—Italian physiotherapists’ knowledge and beliefs when assessing psychosocial factors in patients presenting with chronic low back pain. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2017;27:71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Driver C, Lovell GP, Oprescu F.. Physiotherapists’ views, perceived knowledge, and reported use of psychosocial strategies in practice. Physiother Theor Pract 2021;37(1):135–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cowell I, O'Sullivan P, O’Sullivan K, et al. Perceptions of physiotherapists towards the management of non-specific chronic low back pain from a biopsychosocial perspective: A qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2018;38:113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bishop A, Foster NE.. Do physical therapists in the United Kingdom recognize psychosocial factors in patients with acute low back pain? Spine (Philadelphia Pa 1976) 2005;30(11):1316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378(9802):1560–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pauli J, Starkweather A, Robins JL.. Screening tools to predict the development of chronic low back pain: An integrative review of the literature. Pain Med 2019;20(9):1651–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tegner H, Frederiksen P, Esbensen BA, Juhl C.. Neurophysiological pain education for patients with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain 2018;34(8):778–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wood L, Hendrick PA.. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pain neuroscience education for chronic low back pain: Short-and long-term outcomes of pain and disability. Eur J Pain 2019;23(2):234–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Traeger AC, Hübscher M, Henschke N, et al. Effect of primary care-based education on reassurance in patients with acute low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(5):733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW.. Exercise therapy for treatment of non‐specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(3):CD000335. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Choi BK, Verbeek JH, Tam WW, Jiang JY.. Exercises for prevention of recurrences of low‐back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;2010(1):CD006555. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006555.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C.. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50(3):217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hodder RK, Wolfenden L, Kamper SJ, et al. Developing implementation science to improve the translation of research to address low back pain: A critical review. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2016;30(6):1050–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM.. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol 2015;3(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Green LW, Glasgow RE.. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: Issues in external validation and translation methodology. Eval Health Prof 2006;29(1):126–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eccles MP, Mittman BS.. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci 2006;1(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mesner SA, Foster NE, French SD.. Implementation interventions to improve the management of non-specific low back pain: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. May CR, Johnson M, Finch T.. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci 2016;11(1):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Kreuter MW, Weaver NL.. A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. J Public Health Manag Pract 2008;14(2):117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid-Based Healthcare 2015;13(3):141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(7):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Costa N, Blyth FM, Parambath S, Huckel Schneider C.. What’s the problem of low back pain represented to be? An analysis of discourse of the Australian context. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science 2015;10(1):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci 2015;10(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38(2):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(7):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. French SD, McKenzie JE, O'Connor DA, et al. Evaluation of a theory-informed implementation intervention for the management of acute low back pain in general medical practice: The IMPLEMENT cluster randomised trial. PLoS ONE 2013;8(6):e65471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin IB, Coffin J, O'Sullivan PB.. Using theory to improve low back pain care in Australian Aboriginal primary care: A mixed method single cohort pilot study. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jenkins HJ, Moloney NA, French SD, et al. Using behaviour change theory and preliminary testing to develop an implementation intervention to reduce imaging for low back pain. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Science 2017;12(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S.. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Science 2012;7(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]