Abstract

Cancer is a highly lethal disease, and its incidence has rapidly increased worldwide over the past few decades. Although chemotherapeutics and surgery are widely used in clinical settings, they are often insufficient to provide the cure for cancer patients. Hence, more effective treatment options are highly needed. Although licorice has been used as a medicinal herb since ancient times, the knowledge about molecular mechanisms behind its diverse bioactivities is still rather new. In this review article, different anticancer properties (antiproliferative, antiangiogenic, antimetastatic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects) of various bioactive constituents of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) are thoroughly described. Multiple licorice constituents have been shown to bind to and inhibit the activities of various cellular targets, including B-cell lymphoma 2, cyclin-dependent kinase 2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinases, mammalian target of rapamycin, nuclear factor-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, vascular endothelial growth factor, and matrix metalloproteinase-3, resulting in reduced carcinogenesis in several in vitro and in vivo models with no evident toxicity. Emerging evidence is bringing forth licorice as an anticancer agent as well as bottlenecks in its potential clinical application. It is expected that overcoming toxicity-related obstacles by using novel nanotechnological methods might importantly facilitate the use of anticancer properties of licorice-derived phytochemicals in the future. Therefore, anticancer studies with licorice components must be continued. Overall, licorice could be a natural alternative to the present medication for eradicating new emergent illnesses while having just minor side effects.

Keywords: licorice, cancer, apoptosis, cell cycle, angiogenesis, treatment, nano-delivery

Introduction

Since ancient times, humankind has strongly relied on medicinal plants and herbs in the treatment of diverse health conditions, including both benign neoplasms as well as malignant tumors.1–3 Moreover, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) reports, about 80% of the worldwide population still depend on plant-derived drugs today, whereas several modern medicines have been originally isolated from medicinal plants.4 It is especially the case for anticancer drugs, of which more than 60% of clinically-approved drugs are directly or indirectly derived from plant kingdom.5,6 One of the oldest and most frequently described herbs in India, China, Southern Europe is licorice (Glycyrrhiza. glabra L.), as its roots have been utilized for alleviating pain and treating gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms already for centuries.7–9 This plant is believed to have originated in Iraq, being widespread in China, India, Iran, Afghanistan, Spain, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia.8,9 The extract prepared from licorice roots is very sweet and used worldwide as a flavoring agent in tobacco products, food, cosmetics and herbal remedies, with an estimated annual consumption of about 1.5 kg/person.10 The earliest written evidence about the use of licorice date back to 2100 BC, when this plant was recommended for its health-promoting and life-enhancing properties.11 Today, we know that the roots of licorice contain more than 20 triterpenes and about 300 flavonoids, many of which have been described to exert various pharmacological effects, including different chemopreventive and anticancer bioactivities. Considering a continuous increase in the global incidence of new cancer cases,12–17 identification of novel efficient remedies to manage this dreadful disease is imperative.

Although several comprehensive review articles have been published about chemopreventive and anticancer activities of licorice and its bioactive phytocompounds in the recent years,7,9,18–22 none of them analyze anticancer properties of its structurally different constituents (eg, triterpenes glycyrrhetinic acid and glycyrrhetic acid; chalcones isoliquiritigenin, licochalcone A and licochalcone E; and isoflavone isoangustone), describing both molecular mechanisms as well as bioavailability of these bioactive components.23,24 Moreover, the present review article is focused on anticancer action of the major ingredients of licorice not only as separate agents but also in combination with approved chemotherapeutic drugs, administered as free compounds or encapsulated into nanoformulations to target the low bioavailability generally characteristic to natural substances. Therefore, this review represents an integrated contemporary overview, bringing together all the aspects we currently know about anticancer action of licorice, also providing modern solutions to the present bottlenecks associated with cancer prevention.

Literature Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched for studies published up to 1st June, 2022, assessing the association between licorice and cancer prevention. The major key words used were licorice bioactive components and cancer cell apoptosis or cell cycle arrest or anti-inflammation or antioxidation or antiangiogenesis or antimetastasis. A manual search for additional references was also executed by referring to the reference lists of retrieved articles. The researchers completed blind double-checks, to exclude irrelevant literature by discussing with co-authors. In present review, we searched 656 articles and included 282 publications on anticancer actions of licorice constituents.

Licorice in Food and Medicine

Licorice is a sweetener that can be found in a variety of soft drinks, foods, snacks, and herbal medicines. Its sweet flavor makes it appealing to many manufacturers to mask the bitterness of many products. Licorice based snacks, Egyptian drink “erk soos”, Belgian beers, pastis brands, and anisettes are all widely consumed. Tobacco product manufacturers utilize licorice as a flavoring and sweetening agent. Herbal and licorice-flavored cough mixtures, licorice tea, throat pearls, licorice-flavored diet gum, and laxatives are all examples of health items that contain licorice.25

Licorice is also utilized in a wide range of medical conditions. Licorice extracts have been utilized as herbal treatments in China and Japan for a long time. The biggest challenge with licorice dosing is that it comes in a variety of forms, including snacks, soft drink and health supplements with varying concentration. It has been observed that production of such health supplements is not strictly controlled. European Union established a temporary upper limit of 100 mg/day for glycyrrhizin consumption (about the amount found in 60–70 g licorice).26 Based on data from studies involving human volunteers, recognized food committees confirmed a daily maximum of 100 mg in April 2003.27 Due to limited human toxicity reports food committees are unable to conclude a specific intake dose of GA and ammonium glycyrrhizinate.

Glycyrrhizin is found in roughly 10–20% of licorice fluid extracts; typical doses of 2–4 mL yield 200–800 mg. According to a study, approximately 2% of frequent users ingest more than 100 mg of glycyrrhizinic acid on a daily basis.28 Walker and Edwards29 showed in 1994 that daily oral consumption of 1–10 mg glycyrrhizin, equivalent to 1–5 g licorice, is considered a safe amount for most healthy adults.

Licorice has long been used as an antidote to counteract the toxicity of chemotherapeutic treatment. Licorice is classified as “Rasayana” in Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine), which indicates it has nourishing, renewing, and strengthening properties. Recent research has shown its significance in a variety of biological functions in the human body, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as a protective effect on several organs.30,31 Licorice’s Generally Recognized as Safe accreditation allows it to be used in a wide range of foods at usual concentrations. Licorice’s sweet flavor makes it appropriate for a variety of uses in foods, such as confectionery and sauces, with the rhizomes and roots being the most commonly utilized plant parts. For example, licorice is used in the flavoring of London drops (candy brand) and Red Vines®. Licorice powder is commonly used to add a unique flavor to sweet chilli sauce and soy sauce in condiments. Glycyrrhiza has been used to cure a variety of diseases in traditional medicine and clinical practice across cultures.32 However, according to the extraction process,33 geographical origin,34,35 drying method,36 and harvesting period,37 the observed biological activity of Glycyrrhiza can vary.

Major Bioactive Constituents of Licorice

Glycyrrhizinic Acid

The main sweet-tasting ingredient of G. glabra (licorice) root is glycyrrhizin (or glycyrrhizinic acid or GA). It is a pentacyclic triterpene saponin with a structure that is employed as an emulsifier and gel-forming agent in foods and cosmetics (Figure 1). Enoxolone is its aglycone. It is a glycyrrhetinic acid-containing triterpene glycoside with a wide spectrum of pharmacological and biological properties.38,39 It comes in the forms of ammonium glycyrrhizin and mono-ammonium glycyrrhizin when isolated from the plant. GA is an amphiphilic molecule, with the glucuronic acid residues representing the hydrophilic region and the glycyrrhetic acid residue representing the hydrophobic region. The chemical form of GA is C42H62O16, with a molecular weight of 822.92 g/mol.40

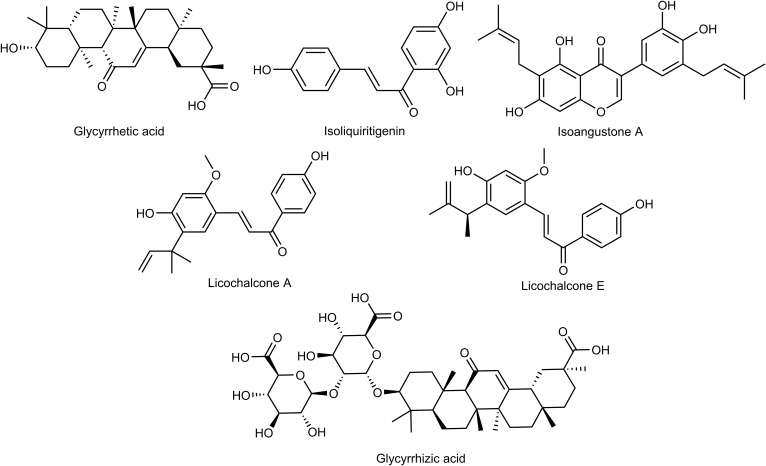

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of major bioactive phytocompounds from licorice.

Glycyrrhetic Acid (GLA)

GLA, also known as glycyrrhetinic acid (Figure 1), is a β-amyrin ursane-type pentacyclic triterpenoid derivative obtained by hydrolysis of GA, which comes from the herb licorice.41 GLA is a glycyrrhizin aglycone.42 The chemical form of GLA is C30H46O4, with a molecular weight of 470.7 g/mol. Many bioactive pharmaceuticals are synthesized using GLA as a precursor compound.

Isoliquiritigenin (ILG)

Licorice root contains isoliquiritigenin (ILG) (Figure 1), a phenolic chemical component.43 ILG belongs to the trans-chalcone hydroxylated at the C-2’, C-4, and C-4’ class of chalcones. Chalcones are characterized chemically as α, β-unsaturated biphenyl ketones. In several plants, ILG is a precursor to numerous flavanones. ILG is a biosynthetic precursor and isomer of flavanone liquiritigenin (LG), as well as a number of other flavonoids synthesized through the phenylpropanoid pathway.44,45 Furthermore, investigations show that ILG and LG are interchangeable by temperature and pH. The chemical form of ILG is C15H12O4, with a molecular weight of 256.25 g/mol.

Isoangustone A (IAA)

IAA (Figure 1) is a flavonoid compound found in the root of licorice. IAA belongs to the isoflavanones family. The chemical form of IAA is C25H26O6, with a molecular weight of 422.5 g/mol.46

Licochalcone A (LicoA)

LicoA (Figure 1) is a phenol chalconoid derivative found in and isolated from the roots of the Glycyrrhiza species G. glabra (licorice) and G. inflata. LicoA is a flavonoid that belongs to the oxygenated retro-chalcones group. Two phenolic hydroxyl groups, a methoxyl group, and an isoprene side chain replace the chalcone nucleus in LicoA.47 It is one of the main important active components of licorice root.48,49 The chemical form of Lico A is C21H22O4, with a molecular weight of 338.4 g/mol.

Licochalcone E (LicoE)

LicoE (Figure 1) is a retrochalcone isolated from the root of G. inflate and possesses numerous biological and pharmacological properties.50 The chemical form of LicoE is C21H22O4, with a molecular weight of 338.4 g/mol.

Absorption and Metabolism Studies of Major Licorice Bioactive Compounds

With the high associated toxicity encountered by cancer patients, there is an urgent need to investigate novel ways to protect patients from the side effects of traditional drug delivery systems.51,52 Licorice is commonly utilized as an ingredient in many traditional medicinal systems, such as traditional Chinese medicine in China, Ayurveda and Siddha in India, and Unani in Southern Europe, and it has been studied for its numerous pharmacological properties, including its anticancer capabilities.53 Pharmacokinetic studies are required to comprehend the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) features of bioactive substances. The ADME properties of licorice bioactive compounds vary because of the natural product class they belong to such as tri-terpenoids and flavonoids as evidenced in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

ADME Profile of Triterpenoids (GA and Glycyrrhetic Acid) of Licorice

| Compound | Pharmacokinetic Parameters | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA | Absorption | Oral intake: Cmax = 1.3μg/mL after a dose of 50 mg/kg. AUC = 7.3 ± 1.8 μg.h/mL Intraperitoneal: Cmax = 238.9 μg/mL after a dose of 50 mg/kg with a mean bioavailability rate of 80% Intravenous: Decreased exponentially after administration |

[210] |

| Fructose containing molecules hinder the uptake of glycyrrhizin | [211] | ||

| Distribution | Volume of distribution ranges from 37–64 mL/kg to 59–98 mL/kg | [212] | |

| Does not bind with any plasma proteins | [213] | ||

| Metabolism | Conversion to 18-glycyrrhetic acid 3-O-monoglucuronide and glycyrrhetic acid by intestinal bacteria | [39,214] | |

| Upregulated CYP3A4 mRNA and protein expression via Pregnane X receptor activation Inhibition of CYP7A1 enzyme due to increased expression of small heterodimer protein |

[215] | ||

| Excretion | Excretion profile of 3β-monoglucuronyl-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid was measured as glycyrrhizin is completely metabolized to this by-product Average tmax was found to be 23.9 h Value of Cmax was found to between 0.49 and 2.69 μg/mL |

[216] | |

| Glycyrrhetic acid | Absorption | Inhibitor of P-glycoprotein which affects multidrug resistance | [217] |

| Inhibits uptake of sodium and copper ions when co-administered | [218] | ||

| Metabolism | Kaempferol and berberine significantly affect bioavailability at certain time intervals | [219] | |

| Inhibits metabolism of cortisone and cortisol causing increased half-life and Cmax | [220] | ||

| Inhibits CYP3A4 enzyme | [221] | ||

| Major route of elimination via glucuronide conjugation in a rapid way | [222] |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; Cmax, maximum serum concentration; CYP3A4, cytochrome P450 3A4; GA, glycyrrhizinic acid; tmax, time to peak drug concentration.

Table 2.

ADME Profile of Flavonoids (Isoliquiritigenin, Isoangustone a, Licochalcone A) of Licorice

| Compound | Pharmacokinetic Parameters | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoliquiritigenin | Absorption | After intraperitoneal injection: tmax = 60 min Rapid absorption from GI tract |

[223] |

| Distribution | After intraperitoneal injection biodistribution was found to be: Liver > kidney > spleen > blood > lung > brain > heart Organ biodistribution achieved at 120 min |

[223] | |

| Metabolism | Hydroxy metabolite is a potent antioxidant but a weaker anti-apoptotic agent | [224] | |

| Metabolite butein formed by liver microsomes is a potent antioxidant | [225] | ||

| Increases CYP1A1 levels Major route of elimination by glucuronidation |

[226] | ||

| Isoangustone A | Metabolism | Major metabolic routes include hydroxylation, glucuronidation and sulfation | [227] |

| Licochalcone A | Distribution | Well distributed in liver and mammary tissues | [226] |

| Metabolism | Downregulates the activity of CYP2C19, CYP2C8, CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 proteins | [228] | |

| Time dependent inhibition of CYP3A enzymes | [229] | ||

| Liver microsomal pathway of biotransformation Slow metabolism by phase I pathway as compared to rapid elimination by Phase II pathways Metabolites formed were mainly from oxidation, glucuronidation and glutathione pathways |

[230] | ||

| Inhibition of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein transporter caused nifedipine overdose | [231] |

Abbreviations: ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion; GI, gastrointestinal.

Cellular Targets of Licorice Constituents in Cancer

Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Potential

Inflammation that occurs in response to physical, chemical or biological stimuli plays a substantial role in preventing or promoting carcinogenesis through immune surveillance.54,55 Inflammatory mediators, such as growth factors, cytokines and chemokines, are released by immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes.56 ROS, on the other hand, can play a role in activating the inflammation related transcriptional factors (eg, NF-κB and STAT-3) and contribute to the carcinogenesis processes, including genomic instability, resistance to apoptosis, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis.57–62 Licorice is known to have significant anti-inflammatory activity and its use in the treatment of inflammatory diseases dates back to ancient times.63 Many studies have shown that licorice triterpenes, such as glycyrrhizin and glycyrrhetinic acid, and flavonoids, such as dehydroglyasperin C, echinatin, glabridin, glyurallin B, isoangustone A, isoliquiritigenin, licochalcone A-E, licoricidin and licorisoflavan A, have significant anti-inflammatory effects.63,64 Glycyrrhizin, which has an anti-inflammatory effect similar to the glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, can inhibit inflammatory factors and promote the healing of mouth and stomach ulcers.65 Sun and coworkers66 have reported that glycyrrhizin suppresses lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory responses via blocking the high mobility group protein box 1 (HMGB1)-Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-NF-κB pathway. Moreover, glycyrrhizin and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid have been defined by different investigators as significant inhibitors of inflammatory factors, such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), HMGP 1, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), TGF-β, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), myeloperoxidase (MPO) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB).67–72 Dehydroglyasperin C has been reported to suppress the production of ROS and singlet oxygen radicals, and it exerts anti-inflammatory activities by reducing the DNA binding activity of NF-κB, increasing the expression of MKP-1 and heme oxygenase-1, and inhibiting COX-2 expression via blocking the MKK4 and PI3K pathways.73–75 Although echinatine, licochalcone A and licochalcone B inhibit IL-6 and PGE2 in LPS-induced macrophage cells, licochalcones B and D reduce the production of TNF-α and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1).76–78 Moreover, licochalcone C inhibits the NF-κB pathway by reducing the expression of iNOS, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. Licochalcone E also shows anti-inflammatory activity by suppressing NF-κB and AP-1 and reducing the expression of iNOS and COX-2.79,80 In addition, glabridin, one of the most studied anti-inflammatory flavonoids isolated from licorice, suppresses inflammatory responses in different cell lines via the NF-κB pathway and inhibition of the expression of various cytokines and chemokines.81 It has been reported by different researchers that glabridin suppresses the expression of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CXCL5), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-23, interferon (IFN)-α/β, iNOS, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), nitric oxide (NO), TNF-α, PGE2, COX-2, MPO and lipoxygenase (LOX) and inhibits the activation of the p38 MAPK, ERK, NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways (Figure 2).81 A natural chalcone called isoliquiritigenin, isolated from licorice, also has significant anti-inflammatory activity via inhibition of caspase-1, COX-2, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, iNOS, TNF-α, NF-κB ligand RANKL and eotaxin-1, and suppression of the NF-κB, MAPK, AP-1 signaling pathways and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.45,82–87 Furthermore, isoliquiritigenin and isoliquiritin inhibit inhibitory κBα (IκBα) phosphorylation and degradation, and increase the expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and heme oxygenase-1 in LPS-induced macrophage cells.88

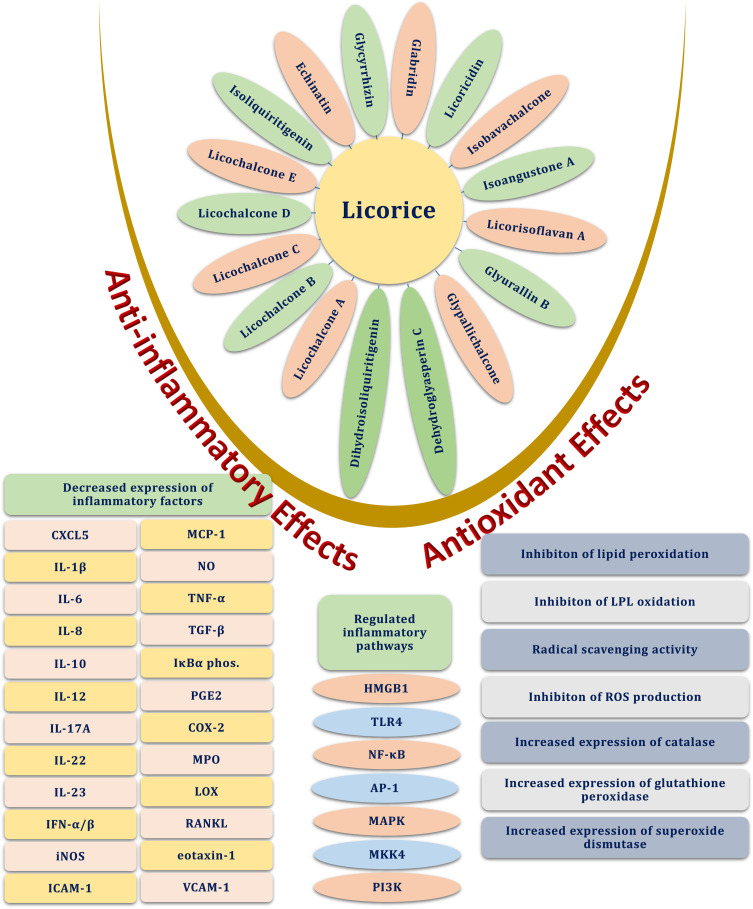

Figure 2.

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of licorice and its constituents.

Abbreviations: AP-1, activator protein 1; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; CXCL5, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 5; HMGB1, high mobility group protein box 1; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IκBα phos, nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha phosphate; LOX, lysyl oxidase; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MKK4, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B; NO, nitric oxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1.

The phenolic ingredients, such as chalcones, coumarins, flavonoids, isoflavones and methylated isoflavones, seem to be responsible for the antioxidant activity of licorice (Figure 2). ROS has a high affinity for DNA and other biomolecules. This can result in DNA damage and oncogenic mutations being incorporated into normal cells leading to genomic instability, and finally cancer.89 Due to the phenolic hydroxyl structure of chalcones, they act as proton donors and combine with a radical to prevent oxidative damage.90,91 The chalcones isolated from licorice, such as echinatin, isobavachalcone, isoliquiritigenin, and licochalcones A-D, have been reported as powerful antioxidant agents.76,92,93 Although isobavachalcone and licochalcones A-D suppress NADPH induced lipid peroxidation, echinatin and licochalcone A and B possess strong radical scavenging activity. Licochalcone A and C elevate the expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase, glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase.94,95 Moreover, dihydroisoliquiritigenin inhibits glutamate-induced oxidative stress in neuronal cells, and glypallichalcone acts as an inhibitor of LPL oxidation.96,97 Similar to the chalcone derivatives, coumarin compounds in licorice have significant radical scavenging activity.98,99 Moreover, saponins and polysaccharides isolated from licorice have been reported to exert antioxidant activities.100–102 Consequently, it seems that the triterpenes, chalcones, coumarins, flavonoids, isoflavones and methylated isoflavones have significant antioxidant activity inhibiting the processes of carcinogenesis, and these contents of licorice have great potential as novel anticancer agents.

Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest

Cancer is one of the leading diseases affecting human life and is caused by various reasons, such as environmental pollution and unhealthy lifestyle.103–106 Apoptotic cell death is known to regulate cancer cell proliferation, invasion and survival. Intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis are the two major pathways induced by chemotherapeutics to inhibit tumor proliferation (Figure 3). Inhibition of apoptosis is considered to be an important mechanism toward drug resistance. In recent years, the interest has shifted to exploring apoptotic phytochemicals for cancer treatment and overcoming drug-resistance with lower side-effects.56,107–111 The anticancer properties of licorice were studied in MCF-7 (breast cancer) and HepG2 (liver cell carcinoma) cell lines where licorice root extract was used to synthesize gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). It was observed that 50 µg/mL and 23 µg/mL of the synthesized AuNPs could successfully inhibit the growth of MCF-7 and HepG2 cell lines, respectively.112 Similar results were obtained in a study conducted by Vlaisavljević et al113 where different cancer cell lines, such as SiHa, HeLa (cervical), T47D, MDA-MB-361, MDA-MB-231, and MCF7 (breast), and A2780 (ovarian), were treated with licorice extract and it was found that 30 µg/mL extract induced apoptosis or necrosis in the cells, inhibiting tumor growth.

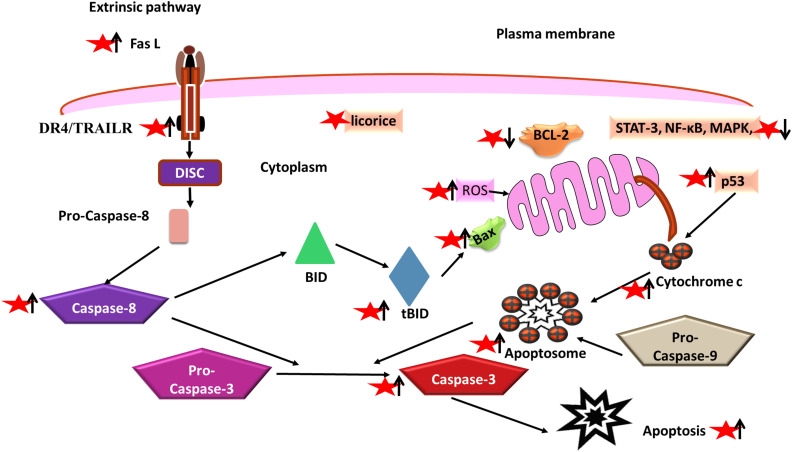

Figure 3.

Suggested apoptotic mechanisms of bioactive metabolites of licorice. They are known to initiate apoptotic cell death in cancer via intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms.

Abbreviations: Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; DISC, death-inducing signaling complex; DR4, Death receptor; Fas (L), Fas ligand; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B; ROS, reactive oxygen species; STAT-3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; tBID, truncated BID; TRAILR, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

Licorice contains various flavonoids, such as glabridin, glycyrrhetinic acid, Lico, GA, ILG, and liquiritin.114 The glabridin exhibits anticancer activities as it activates the caspase cascade and mitochondrial apoptotic pathway leading to apoptosis in cancer cells.115 It regulates various signaling pathways, such as signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT-3), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) to inhibit proliferation of various cancer cells, and induces apoptosis of these cells. Glabridin induced apoptosis in Huh7 liver cancer cells by cleaving caspase-9 levels and increasing the release of cytochrome c (cyt. c),116 and in SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells by cleaving caspase-9, caspase-8, and caspase-3, and increasing the concentration of PARP.117 Further, in addition to the caspase cascade, glabridin induced apoptosis in HL-60 acute myeloid leukemia cells by activating the JNK1/2 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways.118 The glycyrrhetinic acid and its derivatives induce mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells, as it was found in a study conducted by Lin et al119 where apoptosis was induced by the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) when NTUB1 (human bladder cancer cells) were exposed to glycyrrhetinic acid 25. Another derivative of glycyrrhetinic acid, 18β- glycyrrhetinic acid (GRA) caused apoptosis in MCF-7 by activating the mitochondrial death cascade, caspase-9 and release of cyt. c. GRA had no inhibitory effect on the MCF-10 A (normal mammary epithelial cells).120 In another study, it was found that GRA was capable of inducing cell cycle death in HepG2 cells by arresting cell growth in the G1-phase and inducing apoptosis at a higher concentration.121 Another triterpene compound exhibiting antitumor properties is glycyrrhizin which is isolated from the roots of licorice. The antitumor activity of glycyrrhizin has been demonstrated in DU-145 and LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Glycyrrhizin induces apoptosis in both cell lines in a concentration-dependent and time-dependent manner.122 Further, the GA, another flavonoid extracted from the roots of licorice also induces apoptosis and suppresses the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells by increased generation of ROS.123 GA induces cell cycle arrest at G1/S phase in gastric cancer cells by downregulating the cyclin E1, cyclin E2, and cyclin D1-3 levels causing cell death in these cancer cells.124

Another important group of metabolites of licorice is chalcones.82,125 The chalcones inhibit cancer cell growth by interacting with the protein nucleophiles and inducing autophagy, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest in cancer cells.126 Licochalcones A, B, C, and D, ILG, echinate, paratocarpin A, kanzonol C, and isoliquiritin apioside (ISLA) are different kinds of chalcones studied for their anticancer properties. Lico A inhibits cancer cell growth through the mitochondrial pathway by activating the caspase cascade and mediating apoptotic and antiproliferative effects via a Sp1-mediated signaling pathway.127 There are several studies depicting the anticancer properties of lico A in gastric cancer cells,128 PC-3 prostate cancer cells,129 and glioma cells.130 Lico B exhibits its anticancer activity via caspase-3 activation, Bax expression enhancement,131 suppressing the expression of CDK1, CDK2 mRNA, cyclin A, antiapoptotic proteins (Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bid), and leading to S-phase arrest.132 Licochalcones C and D, and kanzonol C have anticancer mechanism similar to licochalcone B.133–135 Different studies demonstrate the anticancer mechanism of ILG in breast cancer cells arresting the cancer cell growth at G0/G1 phase,136 A549 non-small-cell lung cancer cells by activation of the protein kinase B survival pathway and caspase cascades,137 renal cancer cells by ROS generation and STAT-3 pathway inhibition,138 and oral squamous cells by G2/M cell cycle arrest.139 Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-stress) and ROS signaling pathways induce extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis, leading to the cancer cell death in esophageal squamous cells when treated with echinatin.140 Tables 3 and 4 represent an overview of various in vitro and in vivo anticancer studies mediated by bioactive compounds of licorice.

Table 3.

In vitro Anticancer Effects and Mechanistic Insight of Licorice Bioactive Phytocompounds

| Type of Cancer | Cell Lines | Anticancer Effects | Mechanisms | Concentration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | SK-MEL-28 and SK-MEL-5 | Induced apoptosis | ↓G1 phase, ↓cyclin D1, ↓cyclin E, ↓p-Akt, ↓p-GSK3β, ↓p-JNK1/2, ↓PI3K, ↓MKK4, ↓MKK7 | 10–20 μM | [46] |

| Glioma | C6 | Suppressed cell proliferation | ↓Cell viability, ↑cytotoxicity towards cancer cells, ↑antitumor activity, ↓cell number, ↑differentiated morphology, ↑reversion of tumor cells to the normal differentiated cells, ↓topoisomerase IIγ | 1, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM | [232] |

| Nasopharyngeal | C666-1 cells | lncRNA-regulated mechanism | ↓lncRNA, ↓AK027294, ↑production of EZH1, ↑caspase-3, ↑caspase-8, ↑caspase-9 | 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL | [233] |

| Nasopharyngeal | C666-1 | Induced apoptosis | ↑Antiproliferative properties, ↑apoptosis rate, ↑percentage of down-regulated amino acids and lipids leading to decreased metabolic disorders, ↓cell proliferation, ↓cell viability, ↑caspase-9 protease activities, ↑caspase-3 | 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL | [234] |

| Pharyngeal squamous | FaDu | Induced apoptosis | ↑Cytotoxicity towards cancer cells, ↑number of dead cancer cells, ↑chromatin condensation, ↑Fas, ↑cleaved caspase-8, ↑Bax, ↑apoptotic protease-activating factor 1, ↑caspase-9, ↑p53, ↓Bcl-2, ↑cleaved caspases-3, ↑cleaved PARP | 0,12.5,25 and 50 µg/mL | [202] |

| Adenoid cystic | ACC-2 and ACC-M | Induced autophagic and apoptotic cell death | ↓mTOR, ↑appearance of membranous vacuoles, ↑formation of acidic vesicular organelles, ↑punctate pattern of LC3 immunostaining, ↓autophagic flux, ↓apoptosis, ↓LC3- II/LC3-I ratio, ↓ cleavage of LC3, ↓autophagic flux, ↑caspase-3, ↑Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, ↑PARP-cleavage, ↓phosphorylated-S6 (downstream target of mTOR) | 5–20 µM | [235] |

| Colon | HT-29 | Induced apoptosis | ↓Proliferation, ↓viability of cells, ↑cell death of cancer cells, ↓HSP90 | 50,100,150, and 200 µg/mL | [236] |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | H1975 A549 | Inhibited metastasis | G0/G1 growth phase cycle arrest, ↓number of cells at both S growth phase and G2/M growth phase, ↓cyclin B1 and cyclin A2, ↓p21 (CDK inhibitor), ↑CDK2, ↑ESR1, ↑PPARG, ↑ESRRA, ↑PRKACA, ↑CXCL8, ↑PLAA, ↑RXRB, ↑MAPK14 levels of CDK4, ↓cyclin D1, ↓CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex | 200,400,600 and 800 μg/mL | [237] |

| Gastric | MKN28 | Inhibited metastasis | ↓Proliferation and metastasis, ↓migration and invasion, ↑LC3II/LC3I ratio, ↑Beclin 1, ↓p62, ↓p-Akt, ↓p- mTOR | 0,5,10,15 and 20 µM | [238] |

| Hepatocellular | MHCC97-H, LO2, and SMMC7721 | Induced apoptosis and autophagy | ↓Cell viability and proliferation, ↑apoptosis frequency, ↑Bax, ↑cleaved-caspase-3, ↑cleaved PARP, ↑endogenous LC3-II, ↓ Bcl- 2, ↓P62, punctate LC3, ↓p-Akt, ↓p-PI3K, ↓p- mTOR | 12.5, 25, and 50 μM | [239] |

| Hepatocellular | HuH7 and HepG2 | Induced autophagy | ↑Autophagosome number, ↑ROS generation, ↑TSC1/2 complex, ↑PRAS40, ↑ CTMP, ↑PP2A, ↑ PDK1 and ↑Rubicon ↑LC3 II, ↑cleaved-PARP, ↑cleaved-caspase-3 | 10,20,50,100 μM | [240] |

| Renal | Caki | Induced apoptosis | ↑Cleavage of caspase-9, caspase-7 and caspase-3, and PARP, ↑Bax, ↓Bcl-2, ↓ Bcl-xL, ↑cyt. c release, ↑p53, ↓MDM2, ↑ROS levels, ↓STAT3, ↓cyclin D1 and D2, ↓p-JAK2, | 0,5,10,20 and 50 µM | [138] |

| Breast | MDA-MB-231 triple negative | Induced apoptotic and autophagic-mediated apoptosis | ↓Cell cycle progression, ↓cyclin D1, ↑sub-G1 phase population, ↓Bcl-2, ↑ Bax, ↑caspase-3, ↑PARP, ↓mTOR, ↓p-mTOR ↓ULK1, ↓cathepsin B, ↑p62, ↑Beclin1, ↑ LC3, ↑caspase-8 | 10, 25 and 50 µM | [241] |

| Breast | MDA-MB-231 | Induced apoptosis | ↓Cell migration, ↓cell proliferation, ↑ mitochondrial membrane potential, ↑DNA damage, ↓ oxidative stress, ↑cleaved-caspase 3 and 9, ↓Bcl-2 expression, ↑E-cadherin ↓Vimentin, ↓N-cadherin, ↑release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm, ↑ROS | 30–40 µM | [242] |

| Breast | MDA-MB-231 | Exerted anti-inflammatory and antitumorigenic effects | ↓NO production, ↓iNOS, ↓LPS/IFN-γ, ↑NF κB, ↑ERK, ↑miR-155, ↓bound p50 and p65 | 10,50,100 and 200 μM | [243] |

| Breast | MCF-7 | Induced apoptosis | Cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase, ↓Bcl-2, ↑Bax, ↓cyclin D1, ↑PARP cleavage, ↑CIDEA | 15, 10, and 5 µg/mL | [244] |

| Breast | MCF-7 | Induced apoptosis | ↓Cell viability and proliferation, ↑apoptosis frequency, ↑TFF1 (pS2), ↑CTSD, ↑CDKN1A (an effector of p53), ↑RPS6KA (RSK; MAPK-related) ↑NRIP1 (RIP140, AP-1-related), ↓TP53I11 (p53- related), ↓PRKCD ↓ARHGDIA (a Ras super-family gene) | 0.1–100 μM | [245] |

| Murine mammary | 4T1 and MCF-10A | Inhibited metastasis | ↓Tumor growth, cell proliferation, ↓VEGF-A, ↓CD31 ↓HIF-1α, ↓iNOS, ↓COX-2 | 0,1,2.5 and 5.0 µg/mL | [246] |

| Bladder | T24 | Induced apoptosis | ↑Nuclear condensation, ↑ nuclear fragmentation, ↑ apoptotic ratio, ↑decrease in the ΔΨ m, ↑Bax, ↑ Bim, ↑Apaf-1, ↑caspase-9, ↑caspase-3, ↓Bcl-2, ↑CDK2 | 10,20,30,40,5, 60.70 and 80 µg/mL | [247] |

| Bladder | T24 | Induced apoptosis | ↓Proliferation, ↑ROS,↑apoptosis frequency, ↑mitochondrial dysfunction, ↑caspase-3, ↑PARP cleavage, ↑ER stress; GRP 78, ↑growth arrest, ↑DNA damage-inducible gene 153/C/EBP homology protein (GADD153/CHOP) expression, ↑caspase-12 | 20, 40, 60, 80, or 100 µM | [248] |

| Endometrial | HEC-1A, Ishikawa, and RL95-2 | Inhibited metastasis | ↓Survival rate of cancer cells, ↓N-cadherin, ↑E-cadherin | 1, 5, 10, and 20 µM | [182] |

| Endometrial | Ishikawa, HEC-1A, and RL95-2 cells | Induced apoptosis and autophagy | ↓Viability of cancer cells, ↑sub-G1 or G2/M phase arrest, ↑DNA damage, ↑cell cycle arrest, ↑apoptotic cell death, ↑cleaved caspase-3, ↑cleaved PARP, ↑caspase-7/LC3BII, ↑p-ERK, ↑LC3-II, ↑SQSTM1/p62 levels | 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM | [249] |

| Prostate | PC-3 | Induced apoptosis and autophagy | ↓Proliferation, G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, ↑apoptotic effect, ↑necrosis percentage, LC3B-II protein, ↑LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio, ↑LC3A, ↑mRNA level ULK1 and AMBRA1, ↑NBR1 and p62 | 3–200 μg/mL glycyrrhiza extract + 3–100 nM Adriamycin | [250] |

| Ovarian | OVCAR5 and ES-2 | Induced apoptosis | ↓Viability of cancer cells, ↑G2/M phase arrest, ↑cleaved PARP, ↑cleaved caspase-3, ↑Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, ↑LC3B-II, ↑Beclin-1 | 1, 5, 10, 20, 25, 50, 75, and 100 µM | [251] |

| Cervical | SiHa, HeLa, HK 2 | Induced autophagy and apoptosis | ↓Viability of cancer cells, ↑cleaved-caspase-3, ↑cleaved caspase-9, ↑cleaved-PARP, ↓Bcl-2, ↑LC3-II, ↑Beclin1, ↑Atg5, ↑Atg7 ↑ Atg12, ↓PI3K (p85), ↓p-Akt (ser473), ↓p-mTOR (ser2448), ↓p-mTOR (ser2481) | 10, 30, and 50 µM | [252] |

| Osteosarcoma | Saos-2 | Induced apoptosis | ↓Proliferation, ↓cell migration, ↓cyclin D1, ↑p53, ↑p21, ↑p27, ↓Bcl-2, ↑Bax, ↓level of ATP-synthesis, ↓ PI3K/Akt signaling, ↓MMP2, ↓MMP9 | 0,3,10,30, and 100 µM | [253] |

| Osteosarcoma | U2OS | Induced apoptosis | ↓Proliferation, ↓invasion and migration, ↑apoptosis, ↑Bax, ↑active caspase-3, ↓Bcl- 2, ↓p-Akt, ↓p-mTOR, ↓PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | 5, 10 and 20 µM | [254] |

Abbreviations: AMBRA1, activating molecule in Beclin-1-regulated autophagy protein 1; AP-1, activator protein 1; Apaf-1, apoptotic protease activating factor-1; ARHGDIA, Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha; Atg, autophagy related; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Bax, BCL2 associated X; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; CD31, cluster of differentiation 31; CDK, cyclin dependent kinase; CDKN1A, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A; CHOP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) homologous protein; CIDEA, cell death activator; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; CTMP, carboxyl-terminal modulator protein; CTSD, cathepsin D; CXCL, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ESR1, estrogen receptor 1; ESRRA, estrogen related receptor alpha; EZH-1, enhancer of zeste 1 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit; GADD, growth Arrest and DNA damage inducible protein 153; GRP78, glucose-regulating protein; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1α; HSP, heat shock protein; IFN-γ, interferon- γ; IL, interleukin; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; miR, microRNA; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NBR1, neighbour of BRCA1 gene; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NO, nitric oxide; NRIP1, nuclear receptor-interacting protein 1; p-Akt, phospho-Akt; PARP, poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase; PDK1, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1; p-ERK, phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase; p-GSK3β, phospho-glycogen synthase kinase-3β; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; p-JNK, phospho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase; PLAA, phospholipase A2-activating protein; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; PPARG, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; PRAS, proline-rich Akt substrate; PRKACA, protein kinase CAMP-activated catalytic subunit alpha; PRKCD, protein kinase C delta; RIP140, receptor-interacting protein 140; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RPS6KA, p90 ribosomal S6 kinase-3; RSK, ribosomal S6 kinase; RXRB, retinoid X receptor beta; SQSTM1, sequestosome 1; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TFF1, trefoil factor 1; TP53, tumor protein p53; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; ULK1, Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1; VEGF-A, vascular endothelial growth factor A; ΔΨ, mitochondrial membrane potential.

Table 4.

In vivo Anticancer Effects and Mechanistic Insight of Licorice Bioactive Phytocompounds

| Type of Cancer | Animal Models | Antitumor Effects | Observed Changes | Dosage | Duration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | BALB/c nu/nu mice xenografted with SK-MEL-28 cells | Induced apoptosis | ↓Tumor growth, ↓tumor volume, ↓tumor weight | 2 or 10 mg/kg | 35 days | [46] |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | BALB/c nude mice xenografted with ACC-M cells | Induced autophagic and apoptotic cell death | ↓Tumor frequency, ↑LC3, ↑autophagic responses, ↑apoptosis, ↓mTOR, ↑Atg5 expression | 0.5 g/kg or 1 g/kg/ | 30 days | [235] |

| Colon | Male BALB/c mice injected with CT-26 cells | Inhibit tumor metastasis | ↓Tumor weight, ↑spleen index, improve the physical condition of the tumor bearing mice, ↑formation of tumor necrotic foci through recruiting inflammatory cells, no infiltrated cancer cells were found in the lungs, ↑gut friendly bacteria | 500 mg/kg | 15 days | [238] |

| Colon | BALB/c mice bearing CT-26 cells | Induces apoptosis | ↓Tumor growth, ↑immune organ index, ↑CD4+, ↑CD8+ immune cells population, ↑IL 2, ↑IL 6, ↑IL 7, ↓TNFα | 500 mg/kg | 14 days | [255] |

| Colon | CT 26 | Induces apoptosis | ↓Proliferation of cancer cells, ↑IL-7 gene,↓tumor growth, ↑CD4+ and CD8+ immune cells population, ↑IL 2, IL 6, IL 7, ↓TNFα | 1–100 μg/mL 500 mg/ kg once daily |

14 days | [255] |

| Non-small cell lung | C57BL/6 mice injected with LLC cells | Anti-metastatic | ↑PD-L1, ↑CD8+,↑antigen presentation | 200 mg/kg | 19 days | [237] |

| Hepatocellular | BALB/c-nu/nu mice xenografted with Hep3B cells | Inhibit metastasis and induces apoptosis | ↓Cyclin D1, ↓PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, ↓Vimentin, ↓N-cadherin,↓Bcl-2 | 50 mg/kg, | 18 days weeks | [256] |

| Hepatocellular | Hep3B | Inhibit metastasis and induces apoptosis | G1/S cell cycle arrest, ↓migration and metastasis of cancer cells, ↓cyclin D1, ↑p21, ↑p27, ↓cell cycle transition, ↓PI3K/Akt pathway, ↑E-cadherin, ↓Vimentin, ↓N-cadherin,↓Bcl-2, | 30,40,50,60 µM 50 mg/kg | 3 weeks | [256] |

| Hepatocellular | BALB/c nude mice xenografted with SMMC7721 cells | Induces apoptosis and autophagy | ↓Tumor growth, ↓tumor volume, ↓body weight, ↓tumor weight, ↑cleaved-PARP, ↑cleaved-Caspase-3, ↑Bax, ↑ LC3II, ↓ mTOR, ↓p-Akt, ↓ p-mTOR, ↓Bcl-2 | 50 mg/ Kg | 24 days | [235] |

| Breast | Nude-Foxn1nu mice xenografted with MDA-MB-231cells | Induce apoptotic and autophagic-mediated apoptosis | ↓Tumor weight, ↓volume, ↑caspase-3, ↑ Ki-67, ↑ p62, ↓ VEGF | 2.5 and 5.0 mg/kg | 14 days | [237] |

| Breast | Athymic nu/nu mice xenogarfted with MDA-MB-231 cells | Anti-inflammatory and anti-tumorigenic | ↓Tumor weight, ↓tumor outgrowth, ↓ iNOS, ↓3-NT, ↓inflammation, ↓JAK2/STAT3 | 10 mg/kg | 28 days weeks | [239] |

| Endometrial | Nude mice (CAnN.Cg-Foxn1nu/CrlNarl xenografted with HEC-1A-LUCcells | Inhibit metastasis | ↓Cancer cell migration, ↓tumor metastasis, ↓peritoneal dissemination and serum level of TGF-β1, ↓N-cadherin, ↓p-Smad2/3, ↓TWIST1/2, ↑E-cadherin | 10 mg/k | 28 days | [182] |

| Murine mammary | BALB/c mice xenografted with 4T1 cells | Inhibits metastasis | ↓p-p65NFκB, ↓MMP-9, ↓ICAM-1, ↓VCAM-1, ↓VEGF-A, ↓metastatic lung nodules, ↓infiltration of macrophages, ↓CD31, ↓VEGF-receptor(r)2, ↓LYVE-1, ↓VEGF-C, ↓VEGF-R3 | 2 or 4 mg/kg | 21 days | [246] |

| Endometrial | Athymic nude mice by subcutaneous injection of HEC-1A-LU) | Induces apoptosis and autophagy | ↓Tumor growth, ↓PCNA, ↓caspase-7, SQSTM1/p62, ↓LC3B | 1 mg/kg | 46 days | [249] |

| Cervical | Athymic BALB/c mice xenografted with SiHa cells | Induces autophagy and apoptosis | ↑↓Body weight, ↑cleaved-PARP, ↑cleaved-caspase-3, ↑LC3-II, ↓Ki-67 | 10 and 20 mg/kg | 28 days | [252] |

| Osteosarcoma | NOD-SCID mice xenografted with Saos-2 cells | Induces apoptosis | ↓PCNA, ↓MMP2, ↓ MMP9, ↑caspase-3, ↓p-PI3K, ↓p-Akt | 50 mg/kg | 56 days | [253] |

Abbreviations: Atg, autophagy related; Bax, BCL2 associated X; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; CD, cluster of differentiation; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; IL, interleukin; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; JAKL, Janus Kinase 1; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3; LYVE-1, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PARP, poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase; PCNA, proliferating-cell nuclear antigen; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; p-Smad 2/3, phosphorylated small mothers against decapentaplegic 2/3; SQSTM1, sequestosome 1; STAT-3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; TWIST ½, Twist family basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor 2; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Antiangiogenesis Effect

Angiogenesis or neovascularization is considered to play a vital role in tumor proliferation and metastasis.141–144 In tumors, angiogenesis is intervened by targeting numerous markers that regulate angiogenesis and are considered proangiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF).145–148 These angiogenesis markers have a broader spectrum of target cells which play an essential role in angiogenesis.149,150 In a hypoxic condition, tumor cells cause the release of proangiogenic factors, such as VEGFs, epidermal growth factor (EGF), FGF, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ1)), within the tumor.151 In tumor cells, VEGF is the main angiogenic activator that stimulates angiogenesis via binding to VEGFR2152 (Figure 4). Therefore, according to literature, targeting these pathways’ inhibitors in angiogenesis by herbal plant extract and isolated phytoconstituents was considered an anticancer treatment approach with clinical importance.

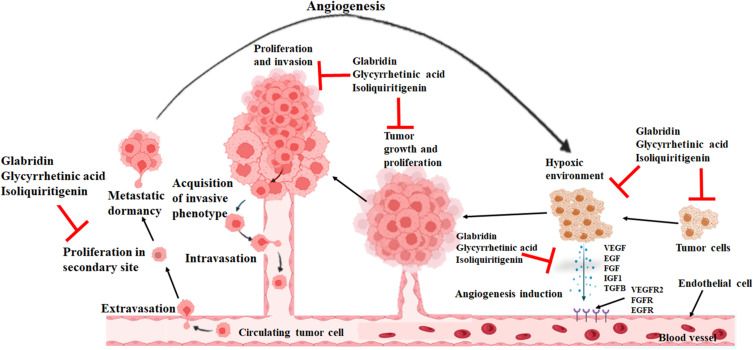

Figure 4.

Tumor angiogenic processes and growth of cancer progression are inhibited by phytoconstituents isolated from licorice.

Abbreviations: EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; IGF1, insulin-like growth factor-1; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factors; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 2.

The extract of G. glabra used to treat mice with Ehrlich ascites tumor cells showed a reduction in the level of cytokines and decreased VEGF revealing its angioinhibitory potential.153 Licochalcone A (LicA) is a potent constituent of licorice having various biological properties, such as anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic and antitumor effects. LicA was reported for its apoptosis inducing potential in prostate cancer via modulating the protein expression of Bcl-2. LicA inhibits the process of angiogenesis and tumorigenesis both in vitro and in vivo by regulating the signaling of VEGFR-2.154 In addition, LicA also reduced the vessel formation by endothelial cells as well invasion and migration via modulating the expression of MMP-9, VEGF-A and plasminogen activators.155 In a study, Jiang et al156 reported that glabridin, a potent constituent of G.glabra, has anticancer potential as it inhibits the migration, invasion and angiogenesis of human breast cancer cells by modulating the FAK/Rho signaling pathway. The aqueous extract of G. glabra blocks the in vitro and in vivo proliferation of Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. According to Kim et al.157 Glycyrrhizin isolated from the roots of G. glabra inhibited the metastasis and survival of tumor by modulating the levels of onco-suppressor p53 gene, MAPK, ERK and EGFR which led to apoptosis and showed antiangiogenetic effect.

Antimetastic Activities

Metastasis is a multistep process that contributes to the spread of cancer cells to distant organs of the body through blood or the lymphatic system, resulting in death in cancer patients.158–163 Targeting metastasis is an attractive strategy in the management of progression and development of cancer (Figure 5).164–166 According to literature, various in vitro and in vivo models showed that natural bioactive compounds, including those from G. glabra, have antimetastasis potential167 including Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), such as MMP-2, and MMP-9, and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) play a significant role in the metastasis process by degrading extracellular matrix (ECM) of cancerous cells as well as modulating the mechanism of angiogenesis in the maintenance of tumor cell survivability.168,169 MMPs are degradation enzymes that modulate numerous physiological processes, such as cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis. However, overexpression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 is linked with prooncogenic events, such as neoangiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation, and metastasis.170–172 In addition to MMPs, ERK1/2, p38, MAPK and JNK/SAPK play a central role in the regulation of cancer metastasis expression.173–176 Furthermore, once cancer cells develop a more invasive nature, they can enter blood and spread to distant regions, resulting in metastasis. Tumor cells that have moved to a secondary site can either go into metastatic dormancy or stimulate angiogenesis and start growing new blood vessels.177 Hence, to control the mechanism of metastasis, targeting oncogenic molecular pathways by natural phytoconstituents is an important therapeutic approach.178,179

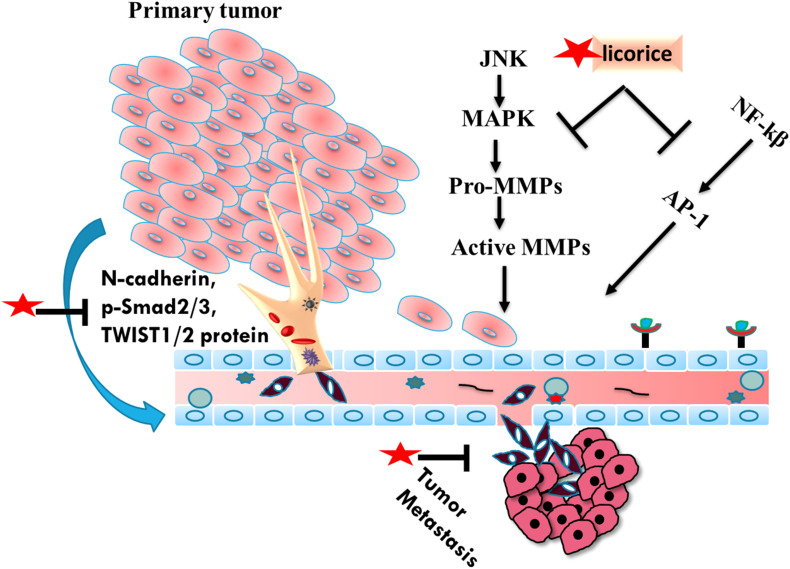

Figure 5.

Antimetastatic actions governed by bioactive metabolites of licorice. It has been observed that metabolites of licorice suppress the expression of MMPs via JNK/MAPK and AP-1 signaling.

Abbreviations: AP-1, activator protein 1; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinases; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B; p-Smad 2/3, phosphorylated small mothers against decapentaplegic 2/3, TWIST ½, Twist Family basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor 2.

Glabridin, a major chemical constituent of licorice, significantly blocks the migration/invasion of various HCC cells, namely Huh7 and Sk-Hep-1, by modulating the expression levels of MMP-9 and the phosphorylation processes of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 markers. This inhibitory effect was linked with an upregulation of tissue inhibitor of MMP-1 and a downregulation of the transcription factors NF-κB and activator protein 1 signaling pathways.180 Wang et al181 reported that GA has the potential to suppress breast tumor outgrowth and pulmonary metastasis by modulating the p38 MAPK-AP1 signaling pathway. In vitro experimentation revealed that LicE decreased the expression of specificity protein 1 (Sp1) in MCF-7 and MDA- MB-231 cell lines, resulting in regulation of the cell cycle as well as inhibiting the process of carcinogenesis and tumor metastasis. Isoliquiritigenin, an isolated component of licorice, inhibited the process of tumor metastasis via upregulating E-cadherin and downregulating the N-cadherin, p-Smad2/3, and TWIST1/2 protein expression in HEC-1A, Ishikawa, and RL95-2 xenograft animal model.182

Synergistic Actions of Licorice Phytochemicals with Anticancer Agents

Licorice is extensively used as an herbal medicine in traditional Chinese as well as Indian medicine to treat gastric, liver, and respiratory problems and different types of cancers, and to reduce the toxicity caused by other herbs. Licorice and its flavonoids show more potential effect against various cancers when used in conjunction with other anticancer drugs. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the role of licorice and other anticancer drugs individually in various cancers. These chemotherapeutic drugs showed great potential in the treatment of a diverse range of cancers, on the other hand, they also exert side effects to the normal cells and induce toxicity.183–185 But when the researchers used anticancer drugs, such as paclitaxel, cisplatin, and gemcitabine in combination with licorice, it inhibited the side effects by protecting the normal cells from toxicity along with enhancing anticancer potential. Tables 5 and 6 show the synergistic effects of licorice with other anticancer drugs both in vitro and in vivo.

Table 5.

In vitro Synergistic Action of Licorice Phytocompounds with Various Anticancer Drugs

| Licorice Metabolites | Anticancer Drugs | Type of Cancer | Cell Lines | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquiritigenin | Cisplatin | Melanoma | B16F10 | ↓PI3K/Akt, ↓MMP-2, ↓MMP-9 | [257] |

| Glycyrrhizin | Cisplatin | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Huh7 | ↑MRP2, MRP-3, MRP-4, MRP5 m-RNAs | [258] |

| Licochalcone-A | Paclitaxel and vinblastine | Leukemia, breast cancer | MCF-7 and HL-60 | ↓Bcl-2 and Bcl-2/Bax | [258] |

| Licochalcone-A | Geldanamycin | Ovarian cancer | OVCAR-3 and SK-OV-3 | ↑Caspase-8- and Bid-dependent pathways and the mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway | [259] |

| Isoliquiritigenin | Cyclophosphamide | Cervical cancer | U14 | ↓Proliferation | [260] |

Abbreviations: Bax, BCL2-associated X; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MRP, multidrug resistance associated proteins; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Table 6.

In vivo Synergistic Effect of Licorice with Various Anticancer Drugs

| Metabolites of Licorice | Anticancer Drugs | Type of Cancer | Model | Antitumor Effects | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquiritigenin | Cisplatin | Melanoma | Female C57 BL/6 black mice | Suppressed cell migration and cell invasion | ↓PI3K/Akt | [257] |

| Licoricidin | Gemcitabine | Osteosarcoma | Female BALB/c nude mice | Enhanced cytotoxicity | ↓Akt and NF-κB | [261] |

| Licochalcone A | Cisplatin | Colon carcinoma | BALB/c mice | Suppressed cell proliferation | ↓DNA synthesis | [262] |

| Isoliquiritigenin | Cyclophosphamide | Cervical Cancer | KM mice | Suppressed cell proliferation | DNA strand break | [260] |

Abbreviations: NF κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Nanotechnology Studies of Bioactive Constituents of Licorice in Cancer

Nanotherapeutics (1–100 nm) have been shown to overcome the shortcomings of conventional treatments,185 such as unwanted side effects on rapidly growing healthy cells, non-specific targeting and distribution, dose-dependent toxicity, and multi-drug resistance.185–187 They possess enhanced target-specificity, increased permeability and retention time of the drug in the cancer cells, improved biocompatibility, and decreased dose of the drug which together contribute to reduced toxicity.185,188,189 Romberg et al190 and Cheng et al191 pointed out that recently developed nanoparticles possess various limitations, thereby shifting the focus of formulation sciences to natural compounds-based nanoparticles which would increase targeting efficiency to cancer cells and lower the rate of clearance. This is further supported by various advantages, such as increased patient compliance (with peroral administration), less extensive metabolic by-products and subsequent higher bioavailability.192 As summarized in Tables 7 and 8, various nanoformulations containing licorice and its bioactive compounds were developed and tested against specific cancer types and results from these studies have been listed. Various cell line studies, as evidenced by Table 7, have focused on hepatic carcinoma due to the abundance of glycyrrhetinic acid receptors which are over-expressed on hepatocytes making it a viable targeting options.193 These have been explored due to the limitations of conventional therapies as mentioned above. The results from cell line studies need to be tested in animal models to confirm the efficacy and safety of the drug or formulation under study. The studies listed in Table 8 represent the intratumor studies conducted thereby helping to uncover the tremendous potential possessed by these nanoformulations in the chemotherapeutic field. Our thorough search revealed that although there were in vitro and in vivo studies carried out for isoangustone A,194–197 licochalcone A198–201 and licochalcone E155,202,203 as anticancer molecules, there were no studies conducted for these molecules in the nanotherapeutics domain. The difficulties encountered during the manufacturing of these medications as nanotherapeutics could be one of the factors limiting their usage as anticancer moieties. The findings suggest that these compounds could be developed into viable anticancer nanomedicines in the future. As a result, the findings can be extended, implying that they have a lot of potential for future clinical research. More research is needed to overcome the problems of nanoformulations and generate reliable medicines with few adverse effects.

Table 7.

In vitro Studies of Nanoformulations of Bioactive Compounds of Licorice

| Formulation Type | Drug Used | Cell Line | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-alginate nanogel | Doxorubicin + Glycyrrhizin (20 mg/mL) | Murine macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7) | Activation and invasion by macrophages averted due to the presence of glycyrrhizin Cells retained the normal morphology, less nitric oxide production Reduced IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α expression Reduced phagocytosis of drug |

[263] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Confirmed pathway of endocytosis and active liver targeting which increased nanogel particle phagocytic intake Decreased cell viability and increased cell toxicity, apoptosis due to reduced efflux activity of p-glycoprotein, upregulation of caspase-3 mRNA and a high Bax/Bcl-2 ratio |

|||

| PEGylated nano-liposomes | Silibinin (25% w/v) + GA (75% w/v) (IC50 = 48.67 μg/mL) | Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells and fibroblast cells | Decreased IC50 value and increased cytotoxicity (10x) than respective free drugs Synergistic action of silibinin in presence of GA |

[264] |

| Nano-micelles formulated as solid dispersion using tannic acid and disodium glycyrrhizin | Camptothecin (0.0145 μg/mL) | Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Increased cell inhibition and cell apoptosis activity compared to free drug Tannic acid inhibited P-gp glycoprotein efflux activity thereby increasing cellular drug uptake |

[265] |

| Glycyrrhizin Conjugated Dendrimer and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes | Doxorubicin (Dendrimer IC50 = 2 μM) (Nanotubes IC50 = 2.7 μM | Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Reduction in IC50 value of the drug compared to formulations without glycyrrhizin and free drug Increased cytotoxicity due to increased drug intake via receptor mediated endocytosis Dendrimers (more apoptotic cells) are more effective carriers than nanotubes (more necrotic cells) when attached with glycyrrhizin |

[266] |

| GA-conjugated human serum albumin nanoparticles | Resveratrol (IC50 = 62.5 μg/mL) | Hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Concentration dependent uptake | [267] |

| Valerate- conjugated chitosan nanoparticles surface modified with glycyrrhizin | Ferulic acid (IC50 = 60 μg/mL) | Hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Increased cytotoxicity due to glycyrrhizin receptor mediated intake of drug | [268] |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid-modified hyaluronic acid nanoparticles | Adenine (0.25 mg/mL) | Human HepG2 cells, L02, Bel-7402 and MCF-7 cells | Absorption into HepG2 in a time dependent manner Targeting efficiency: HepG2>L02>MCF-7 Inhibition of colony formation in time and dose dependent manner Induced apoptosis in cancer cells thus inhibiting proliferation of cancer cells |

[269] |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid-modified hyaluronic acid nanoparticles | Docetaxel (IC50 = 1.6 μg/mL) | HepG2 cells and Human breast cancer MCF7 cells | More uptake by HepG2 than MCF7 cells Decrease in IC50 values and cell viability compared to free drug Inhibition of colony formation of HepG2 cells in time and dose dependent manner Increased apoptosis and deformed morphology |

[270] |

| Hyaluronic acid-glycyrrhetinic acid conjugated nanoparticles | Doxorubicin (IC50 = 5.75 μg/mL) | Hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Increased cleavage in presence of glutathione Rapid intracellular release and nuclear delivery of drug compared to standard of care conventional formulations |

[271] |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid-modified curcumin supramolecular hydrogel | Curcumin (IC50 = 10.7 μM) | Hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 and Mouse fibroblast 3T3 cells | Reduced IC50 values Greater targeting efficiency Higher cellular uptake due to pro-gel formulation approach |

[272] |

| Glycyrrhetinic Acid Functionalized Graphene Oxide | Doxorubicin (0.5 μg/mL) | Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells, normal human hepatic L02 cells, and rat cardiac muscle H9c2 cells | Targeting efficiency: HepG2>L02>H9c2 Taken via endocytosis and delivered to mitochondria Decreased the potential difference of mitochondrial membrane which in turn opened up mitochondrial permeability transition pore to initiate a series of responses and leads to caspase-3 activation necessary for apoptosis |

[273] |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles | Curcumin (2 mg/mL) | Hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Higher cytotoxicity compared to curcumin loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles Receptor mediated endocytosis intake of drug Increased rate of apoptosis |

[274] |

| Dual-functional (modified with glycyrrhetinic acid and L-histidine) hyaluronic acid nanoparticles | Doxorubicin (5 μg/mL) | Hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Decrease in IC50 values Increased drug distribution in cytoplasm and nuclear regions Receptor mediated endocytosis intake of drug |

[275] |

| Nano-suspension | Isoliquiritigenin (0.18 μM) | A549 lung cancer cells | Increased apoptosis at 7.5 to 10-fold Less cytotoxic to healthy cells |

[276] |

| Isoliquiritigenin-iRGD nanoparticles | Isoliquiritigenin (50 μM) | Human breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB231 and MCF7) and mouse breast cancer cell line (4T1) | MCF7 cells showed better inhibition than free drug but not better than isoliquiritigenin nanoparticles MDA-MB231 and 4T1 showed better inhibition than isoliquiritigenin nanoparticles formulation and free drug Increased apoptosis compared to free drug and nanoparticles due to high rates of cellular drug uptake |

[277] |

| Isoliquiritigenin loaded nanoliposomes | Isoliquiritigenin (<12.5 μM) | HCT116, SW620 and HT29 colorectal cancer cell lines | Better inhibition compared to free drug Increased rate of apoptosis Decreased uptake of glucose and lactic acid Reduced oxygen consumption led to reduced adenosine triphosphate synthesis Decreased Akt/mTOR expression which is important for tumor progression |

[278] |

Abbreviations: Bax, BCL2-associated X; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; GA, glycyrrhizinic acid; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; w/v, weight/volume.

Table 8.

In vivo Studies of Nanoformulations of Bioactive Compounds of Licorice

| Formulation Type | Drug Used | Model Used | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycyrrhzic acid-alginate nanogel | Doxorubicin + glycyrrhizin (2.5 mg/kg) | Male Sprague- Dawley rats | Higher blood concentrations of therapeutic agent Increased distribution half-life by 7.5 folds Decreased elimination rate |

[263] |

| H22 tumor bearing Kunming mice | Glycyrrhzic acid inhibited multidrug resistance protein-1 in hepatoma cells enhancing the availability of drug and subsequently anti-tumor activity Less systemic toxicity with no body weight loss | |||

| Nano-micelles formulated as solid dispersion using tannic acid and disodium glycyrrhizin | Camptothecin (5 mg/kg) | Male Sprague- Dawley rats | Improved bioavailability compared to free drug | [265] |

| HepG-2 tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice | Highest distribution at 8h with maximum amount concentrated at tumor site Increased tumor inhibition activity Maintained body weight Tumor cells displayed increased interstitial spaces, large necrotic area and decreased nuclear chromatin |

|||

| GA-conjugated human serum albumin nanoparticles | Resveratrol (5 mg/kg) | H22 tumor bearing male Kunming mice | Better and concentrated biodistribution to liver | [267] |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid-modified hyaluronic acid nanoparticles | Adenine (10 mg/kg) | Kunming mice | Faster biodistribution within 1 hour in mice compared to free drug Reduced tumor volume effectively compared to control and placebo groups Decreased proliferating cell nuclear antigen levels Increased apoptotic cell count |

[267] |

| Hyaluronic acid-glycyrrhetinic acid conjugated nanoparticles | Doxorubicin (4 mg/kg) | H22 tumor bearing Kunming mice | Improved biodistribution with liver tumor targeting efficiency Decreased tumor volume No significant weight loss |

[271] |

| Glycyrrhetinic Acid Functionalized Graphene Oxide | Doxorubicin (2 mg/kg) | HepG2 cells bearing BALB/c nude mice | Increased Bax:Bcl2 ratio confirmed mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening and activation of caspase 3.7 and 9 Decreased tumor size significantly |

[273] |

| Dual-functional (modified with glycyrrhetinic acid and L-histidine) hyaluronic acid nanoparticles | Doxorubicin (5 mg/kg) | H22 tumor bearing mice | Increased liver targeting capacity Higher tumor inhibition efficiency |

[275] |

| Isoliquiritigenin-iRGD nanoparticles | Isoliquiritigenin (25 mg/kg) | 4T1 bearing female nude mice | Mean tumor volume reduced Higher mitotic bodies indicate reduced cell viability |

[277] |

Abbreviations: Bax, BCL2-associated X; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2.

Safety Studies of Licorice

In general, licorice products are considered to have no hazard to the public and are utilized widely in food (ice cream, candies, chewing gums, and beverages), cosmetics (toothpaste) and tobacco as flavoring and sweetening agents.7,9 However, before licorice extract or any of its individual components can enter into clinical oncological practice, due to their strong pharmacological activities, their safety must be verified thoroughly and systematically, paying special attention to the dosage and duration of the treatment.18 Several studies have indeed warranted for the toxicity of licorice depending on its dosage and duration.18 Actually, chronic licorice intake was shown to induce a condition comparable to that found in primary hyperaldosteronism, while licorice overconsumption resulted in hypermineralocorticoidism characterized by salt and water retention, hypertension, hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, and suppression of the renin-aldosterone system.28,204 Biochemical evidence suggests that licorice and its phytochemicals, particularly glycyrrhizinates, can reversibly block the cortisol-inactivating enzyme, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, thereby producing hypermineralocorticoid-like effects.205 In addition, based on a case report, excessive consumption of licorice may also lead to toxic consequences in the form of thrombocytopenia.206 Therefore, health care providers should be aware of the hazardous consequences related to chronic and excessive intake of licorice extracts to be able to prevent worsening of these symptoms when detected early [16]. Furthermore, caution must be exercised when using licorice during pregnancy, as heavy licorice consumption has been associated with lower gestational age and preterm delivery in humans.207,208 Accordingly, the main challenge in exploiting the promising anticancer activities of licorice constituents in clinical settings primarily lies on its appropriate dosing, besides targeted delivery to malignant sites, inducing minimal adverse reactions in normal healthy tissues. It is highly expected that future experimental studies with nano-sized carriers will provide a strong base for overcoming these challenges by virtue of modern nano-technological methods.

Clinical Trials

Several clinical trials conducted with licorice products have also reported glycyrrhizin-related complications, such as elevated blood pressure due to increasing extracellular fluid volume and large artery stiffness, and reduced serum potassium levels.209 However, other clinical trials (mostly on the gastrointestinal disorders) have suggested diverse healing properties of licorice preparations without exerting any observable adverse effects.205,209 A clinical stage II preliminary trial revealed that licorice root extract in combination with docetaxel works in treating patients with hormonal therapy resistant metastatic prostate tumors (NCT00176631). Similarly, licochalcone A and paclitaxel have been shown to increase natural cell death and apoptosis in OSCC tumors (NCT03292822).

Conclusions and Perspectives

Our present review describes anticancer potential of the phytoconstituents of G. glabra along with synergistic chemotherapeutic insight. Traditionally, licorice has been utilized as a sweetening and flavoring agent for food items. Roots of licorice are reported to possess strong therapeutic potential to reduce inflammation and cancer progression. Among the reported phytoconstituents, the flavonoids and terpenoids are the major therapeutically active molecules. The in vitro and in vivo data presented in the current review article clearly show the strong potential of licorice-derived phytochemicals from the classes of triterpenes, chalcones and isoflavones in the fight against different types of cancer. Despite potential therapeutic importance of these effects, several obstacles, such as toxic reactions observed with excessive consumption, have impeded moving on with clinical trials. It is highly expected that surpassing these bottlenecks by using modern nanotechnological methods might lead us to expansion of the current anticancer arsenal. In addition, as licorice constituents possess a wide range of molecular targets in cancer, they might be helpful in preventing drug resistance. Therefore, synergistic mechanistic insight of licorice-derived phytoconstituents and conventional chemotherapeutic drugs should be further explored. There are few human studies available and more randomized controlled trials are needed to measure the effectiveness of licorice-based cancer treatment. The story of licorice reflects a fascinating example of how an ancient herbal medicine can be introduced as a drug into clinical settings, after intensive efforts in elucidating its constituents and molecular mechanisms behind their various bioactivities.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Petrovska BB. Historical review of medicinal plants’ usage. Pharmacogn Rev. 2012;6(11):1–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.95849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Z, Xu Y, Bi Y, et al. Immune escape mechanisms and immunotherapy of urothelial bladder cancer. J Clin Transl Res. 2021;7(4):485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashyap D, Garg VK, Goel N. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pathways of Apoptosis: Role in Cancer Development and Prognosis. 1st ed. Elsevier Inc; 2021:73–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen T, Samanta SK. Medicinal plants, human health and biodiversity: a broad review. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2014;147:59–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fridlender M, Kapulnik Y, Koltai H. Plant derived substances with anti-cancer activity: from folklore to practice. Front Plant Sci. 2015;67:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sak K. Anticancer action of plant products: changing stereotyped attitudes. Explor Target Anti Tumor Ther. 2022;3(4):423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y, Wang Z, Du Q, et al. Pharmacological effects and underlying mechanisms of licorice-derived flavonoids. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med. 2022;2022:9523071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang R, Wang L, Liu Y. Antitumor activities of widely-used Chinese herb—licorice. Chinese Herb Med. 2014;6(4):274–281. doi: 10.1016/S1674-6384(14)60042-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasan MK, Ara I, Mondal MSA, Kabir Y. Phytochemistry, pharmacological activity, and potential health benefits of Gly cyrrhiza glabra. Heliyon. 2021;7(6):e07240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bode AM, Dong Z. Chemopreventive effects of licorice and its components. Curr Pharmacol Report. 2015;1(1):60–71. doi: 10.1007/s40495-014-0015-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang ZY, Nixon DW. Licorice and cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2001;39(1):1–11. doi: 10.1207/S15327914nc391_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuli HS, Sharma AK, Sandhu SS, Kashyap D. Cordycepin: a bioactive metabolite with therapeutic potential. Life Sci. 2013;93(23):863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashyap D, Sharma A, Tuli S, Punia S, Sharma A. Ursolic acid and oleanolic acid: pentacyclic terpenoids with promising anti-inflammatory activities. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2016;10(1):21–33. doi: 10.2174/1872213X10666160711143904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar G, Mittal S, Sak K, Tuli HS. Molecular mechanisms underlying chemopreventive potential of curcumin: current challenges and future perspectives. Life Sci. 2016;148:313–328. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuli HS, Aggarwal V, Kaur J, et al. Baicalein: a metabolite with promising antineoplastic activity. Life Sci. 2020;259:118183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashyap D, Kumar G, Sharma A, Sak K, Tuli HS, Mukherjee TK. Mechanistic insight into carnosol-mediated pharmacological effects: recent trends and advancements. Life Sci. 2017;169:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahab S, Annadurai S, Abullais SS, et al. Glycyrrhiza glabra (Licorice): a comprehensive review on its phytochemistry, biological activities, clinical evidence and toxicology. Plants. 2021;10(12):2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z, Yang L, Hou J, Tian S, Liu Y. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Anticancer Activities of Licorice Flavonoids. Elsevier B.V; 2021:113635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain R, Hussein MA, Pierce S, Martens C, Shahagadkar P, Munirathinam G. Oncopreventive and oncotherapeutic potential of licorice triterpenoid compound glycyrrhizin and its derivatives: molecular insights. Pharmacol Res. 2022;178:106138. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussain H, Ali I, Wang D, et al. Glycyrrhetinic acid: a promising scaffold for the discovery of anticancer agents. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2021;16(12):1497–1516. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2021.1956901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su X, Wu L, Hu M, Dong W, Xu M, Zhang P. Glycyrrhizic acid: a promising carrier material for anticancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alagawany M, Elnesr SS, Farag MR, et al. Use of Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) herb as a feed additive in poultry: current knowledge and prospects. Animals. 2019;9(8):536. doi: 10.3390/ani9080536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alagawany M, Elnesr SS, Farag MR. Use of liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) in poultry nutrition: global impacts on performance, carcass and meat quality. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2019;75(2):293–303. doi: 10.1017/S0043933919000059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitagawa I. Licorice root. A natural sweetener and an important ingredient in Chinese medicine. Pure Appl Chem. 2002;74(7):1189–1198. doi: 10.1351/pac200274071189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy SC, Agger S, Rainey PM. Too much of a good thing: a woman with hypertension and hypokalemia. Clin Chem. 2009;55(12):2093–2096. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.127506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fallows S. Scientific committee on food. Nutr Food Sci. 2000;30(6):72–75. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omar HR, Komarova I, Abdelmalak HD, et al. Licorice abuse: time to send a warning message. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2012;3(4):125–138. doi: 10.1177/2042018812454322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker BR, Edwards CRW. Licorice-induced hypertension and syndromes of apparent mineralocorticoid excess. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23(2):359–377. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(18)30102-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kao TC, Wu CH, Yen GC. Bioactivity and potential health benefits of licorice. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(3):542–553. doi: 10.1021/jf404939f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chauhan P, Sharma H, Kumar U, Mayachari A, Sangli G, Singh S. Protective effects of Glycyrrhiza glabra supplementation against methotrexate-induced hepato-renal damage in rats: an experimental approach. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;263:113209. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiore C, Eisenhut M, Ragazzi E, Zanchin G, Armanini D. A history of the therapeutic use of liquorice in Europe. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99(3):317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asan-Ozusaglam M, Karakoca K. Evaluation of biological activity and antioxidant capacity of Turkish licorice root extracts. Rom Biotechnol Lett. 2014;19(1):8994–9005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karahan F, Avsar C, Ozyigit II, Berber I. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of medicinal plant Glycyrrhiza glabra var. glandulifera from different habitats. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2016;30(4):797–804. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2016.1179590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Statti GA, Tundis R, Sacchetti G, Muzzoli M, Bianchi A, Menichini F. Variability in the content of active constituents and biological activity of Glycyrrhiza glabra. Fitoterapia. 2004;75(3–4):371–374. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2003.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li YH, Li YN, Li HT, Qi YR, Wu ZF, Yang M. Comparative study of microwave-vacuum and vacuum drying on the physicochemical properties and antioxidant capacity of licorice extract powder. Powder Technol. 2017;320:540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2017.07.076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheel J, Tůmová L, Areche C, et al. Variations in the chemical profile and biological activities of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.), as influenced by harvest times. Acta Physiol Plant. 2013;35(4):1337–1349. doi: 10.1007/s11738-012-1174-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cirillo G, Curcio M, Parisi OI, et al. Molecularly imprinted polymers for the selective extraction of glycyrrhizic acid from liquorice roots. Food Chem. 2011;125(3):1058–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]