Abstract

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignancy and third leading cancer-related cause of death worldwide. Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative bacterium that inhabits the gastric environment of 60.3% of the world’s population and represents the main risk factor for the onset of gastric neoplasms. CagA is the most important virulence factor in H. pylori, and is a translocated oncoprotein that induces morphofunctional modifications in gastric epithelial cells and a chronic inflammatory response that increases the risk of developing precancerous lesions. Upon translocation and tyrosine phosphorylation, CagA moves to the cell membrane and acts as a pathological scaffold protein that simultaneously interacts with multiple intracellular signaling pathways, thereby disrupting cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. All these alterations in cell biology increase the risk of damaged cells acquiring pro-oncogenic genetic changes. In this sense, once gastric cancer sets in, its perpetuation is independent of the presence of the oncoprotein, characterizing a “hit-and-run” carcinogenic mechanism. Therefore, this review aims to describe H. pylori- and CagA-related oncogenic mechanisms, to update readers and discuss the novelties and perspectives in this field.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Virulence factors, CagA, Gastric cancer, EPIYA motifs, Hit-and-run carcinogenesis

Core tip: CagA is a translocated effector protein that induces morphofunctional modifications in gastric epithelial cells and persistent chronic gastric inflammation. Upon translocation, the bacterial oncoprotein acts as a promiscuous scaffold or hub protein, which is capable of disrupting multiple host signaling pathways, thereby inducing precancerous cellular alterations. This review aims to describe Helicobacter pylori- and CagA-related oncogenic mechanisms, as well as to discuss the novelties and perspectives in this field.

INTRODUCTION

The multiple virulence mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori confer an ability to colonize the hostile gastric environment[1]. This pathogen infects > 50% of the global population and is a major health concern due to the serious repercussions related to its colonization[2]. Among the diseases predisposed by H. pylori infection, gastric adenocarcinoma is the fifth most common malignancy and third leading cancer-related cause of death worldwide[3]. Of note, the close relationship between H. pylori and gastric cancer has led the World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group to consider the bacterium as a class 1 carcinogen based on epidemiological evidence and biological plausibility[4].

Various virulence factors contribute to successful H. pylori colonization and pathogenicity[5]. Among these factors is cagA, a well-known gene that encodes an oncogenic protein that seems to be a determining agent in H. pylori-related gastric carcinogenesis[6]. CagA seropositivity, regardless of H. pylori status, is associated with increased gastric cancer risk. The cagA gene is located in the pathogenicity island cag (cagPAI), a nucleic acid sequence that encodes the type IV secretion system (T4SS), which is a bacterial apparatus that delivers the CagA protein and peptidoglycans into gastric epithelial cells. Inside host cells, that virulence factor suffers phosphorylation at a Glu-Pro-Ile-Tyr-Ala (EPIYA) motif, a variable C-terminal region and, subsequently, promotes the activation of the SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase (SHP2)[7,8]. SHP2, in turn, triggers various mechanisms that lead to important cell changes, including alterations in cellular morphology through the disturbing of cell polarity, which leads to a “hummingbird” phenotype, as well as carcinogenesis-related changes in cytoskeleton[9].

Despite the extensive number of studies on the relationship between CagA and H. pylori infection, much still has to be done in order to better understand the role of this oncoprotein in gastric carcinogenesis. Recent investigations have explored multiple host–pathogen interactions in this setting and found other CagA-triggered pathways that probably influence cancer development[10]. Moreover, the action of small RNAs in CagA post-transcriptional regulation has been investigated, showing a broad field to be explored[11]. This review aims to describe H. pylori- and CagA-related oncogenic mechanisms, and to discuss the novelties and perspectives in this field.

PATHOGENESIS OF H. PYLORI GASTRIC INFECTION

The capacity to resist severe stomach acid conditions is a notable aspect of H. pylori. To provide successful colonization, the pathogen uses various mechanisms, such as enhanced motility, adherence to gastric epithelial cells, enzymatic machinery, and virulence factors[12]. Besides that, the host immune system also plays an essential role during the infection, mainly by a Th1 response against the bacteria[13].

The bacterial flagella are crucial for reaching the protective mucus layer at the exterior of the gastric mucosa. After entering the stomach, H. pylori uses its flagella for swimming in gastric content, allowing the pathogen to arrive at the mucus layer[14]. Some studies have shown that the ferric uptake regulator performs an important role in bacterial colonization, positively regulating the flagellar motility switch in H. pylori strain J99[15]. Another factor described as a motility modulator is HP0231, a Dsb-like protein. It cooperates in redox homeostasis and is fundamental for gastric establishment[16].

H. pylori also depends on chemotaxis for its colonization. The essential pathogen chemoreceptors are T1pA, B, C, D, a CheA kinase, a CheY responsive regulator, and numerous coupling proteins, playing a pivotal role in bacteria pathogenesis[17]. The aggregation of the coupling proteins CheW and CheV1 culminates in the formation of the CheA chemotaxis complex, activating CheA kinase and optimizing the chemotaxis function[18].

An ideal balance between nickel absorption and incorporation is indispensable for H. pylori colonization, since nickel is an essential metal for bacterial survival and infection[12,19]. This metal is a cofactor for two significant enzymes: urease and hydrogenase. Both of them have a role in gastric infection, contributing, respectively, to bacterial colonization and metabolism signaling cascade to produce energy[20,21].

Adherence and outer membrane gastric cell receptors are also relevant in bacterial pathogenesis. The blood group antigen binding adhesin (BabA) is the best-studied molecule of H. pylori[22]. This protein sequence affects acid sensitivity and plays a critical role in bacterial acid adaptation during infection[12]. Pathogens with high BabA expression levels have increased virulence, leading to duodenal cancer and gastric adenocarcinoma[23]. Another adhesin has been described: HopQ. This molecule binds to cell adhesion molecules related to the carcinoembryonic antigen (carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules, CEACAMs) 1, 3, 5 and 6, promoting cell signaling guided by this interaction, allowing the translocation of the oncoprotein CagA, the most important H. pylori virulence factor, and rising proinflammatory mediators in the infected cells[24,25].

Additionally, besides CagA, a wide range of virulence factors like vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), DupA and OipA have been reported as determinant molecules for H. pylori pathogenicity[26]. VacA, whose gene is found in most bacterial strains, promotes the formation of acidic vacuoles in gastric epithelial cells and modulate the immune response, leading to an immune tolerance and enduring H. pylori infection, due to its role in the activity of T cells and antigen-presenting cells [27,28]. These VacA functions can lead to gastritis and duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer development. The bacterial protein DupA provides acid resistance to the pathogen, and seems to cooperate with the production of interleukin (IL)-8, enhancing its levels in the gastric mucosa[29]. The outer membrane protein OipA contributes to the adhesion and activation of IL-8 production, increasing inflammation. OipA is a significant virulence factor on the infection outcome, resulting in increased development of gastric cancer and peptic ulcers[30].

H. pylori infection produces complex host immune responses, through diverse immune mechanisms[31]. During the first contact with the bacteria, a wide range of antigens like lipoteichoic acid and other lipoproteins bind to stomach cell receptors, known as Toll-like receptors (TLRs)[32]. After this interaction, NF-B and c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation takes place, among the proinflammatory cytokine release as signaling pathways[33]. Neutrophils and mononuclear cells infiltrate the gastric surface, producing nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species (ROS), and recruiting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells[34]. Finally, a Th1-polarized response occurs, with enhanced levels of IFN-γ, IL-1β, Il-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10 and IL-18[35,36].

A correlation has been shown between Th17 cells, a proinflammatory subset of CD4+ T cells, and their affiliated cytokines (IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22 and IL-26) in persistent H. pylori-mediated gastric inflammation and the subsequent gastric cancer development[36,37]. We have demonstrated in a previous study that an IL-17 T-cell response predominates in H. pylori-associated gastritis in adults, whereas, in children, there is predominance of a T regulatory (Treg) cell response. IL-17A is known to play an important role in the recruitment and activation of polymorphonuclear cells that are vital for H. pylori clearance. Treg and Th17 cells are mutually controlled. Therefore, these findings could explain the higher susceptibility of children to the infection and bacterial persistence[38].

IL-27 expression differs between H. pylori-related diseases. Accordingly, we have shown that there is a high expression of IL-27 in the gastric mucosa and serum of H. pylori-positive duodenal ulcer patients. In contrast, IL-27 is absent in the gastric mucosa and serum of patients with gastric cancer. Consistent with the immunosuppressive role of IL-27 in Th17 cells and IL-6 expression, we observed that expression of Th17-cell-associated cytokines was lower in the patients with duodenal ulcer, which secreted a large concentration of proinflammatory Th1 representative cytokines. We demonstrated that there is high levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A, IL-23, and transforming growth factor-β, involved in IL-17A expression, on the gastric mucosa and in the serum of gastric cancer patients. Therefore, IL-27 may be involved in the development of different patterns of H. pylori-induced gastritis and its progression. Taking into account that IL-27 has evident antitumor activity, our results point to a possible therapeutic use of IL-27 as an anticancer agent[39].

Recently, the role of the interaction between H. pylori infection and the gastrointestinal microbiome in gastric carcinogenesis has also been investigated. In this regard, researchers explored the diversity and composition of the gastric microbiome at different stages of disease, including normal gastric mucosa, chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric cancer[40]. A recent meta-analysis indicated that H. pylori-positive gastric samples exhibit reduced microbial diversity, altered microbial community, composition, and bacterial interactions. An increased abundance of opportunistic pathogens (e.g., Veillonella and Parvimonas) was observed concomitantly with a decrease in putative probiotics (e.g., Bifidobacterium) throughout the stages of disease progression[41]. Another study has suggested that successful eradication of H. pylori could reverse the tendency towards gastric microbiota dysbiosis and show beneficial effects on the gastric microbiota[42]. The next step in this field could be to conduct a prospective, multicenter, crosscultural study to validate these results and explore the mechanisms underlying the H. pylori–gastric microbiota interaction and its role in gastric cancer development[43].

CAGA — H. PYLORI TRANSLOCATED ONCOPROTEIN

CagA is a translocated effector protein that induces morphofunctional modifications in gastric epithelial cells and inflammatory responses, whose balance allows successful colonization of the acidic stomach environment[44,45]. The CagA gene is located in the cagPAI; a 40-kb DNA fragment that contains about 31 genes and confers virulence to some strains of H. pylori. Some genes of the island encode proteins that form a T4SS, which is responsible for the translocation of CagA into the cytoplasm of gastric epithelial cells through interaction of bacterial and host cell components[46-48]. The oncoprotein has a molecular weight of 128–145 kDa and its tertiary structure is characterized by a structured N-terminal region, split into Domains I–III and an unstructured C-terminal tail[49].

Injection of CagA depends on the recognition of its N-terminal and C-terminal portions by T4SS, which can occur simultaneously or not[50]. However, several other mechanisms are also required for its inoculation. We highlight the binding between T4SS CagL and CagY to human β1-integrins[51,52], along with the CEACAMs and H. pylori outer membrane protein Q (HopQ) interaction, that allow the translocation of CagA into the host cells[53]. A recent study noted that the instability of the relationship between H. pylori HopQ and mouse CEACAMs may explain why the pathogenesis of infection in the stomach of rodents infected with CagA positive H. pylori strains occurs differently from infection by the same strain in humans. The authors also demonstrated that the presence of functional T4SS is associated with a time-dependent reduction in human CEACAM1 levels after CagA-positive H. pylori infection[54]. However, it is still unclear whether the instability of the HopQ–CEACAMs relationship favors the host or the bacterium, so more studies are needed to investigate the possibility of these interactions being beneficial in favor of the patient infected with H. pylori. BabA is apparently also capable of increasing T4SS activity[55].

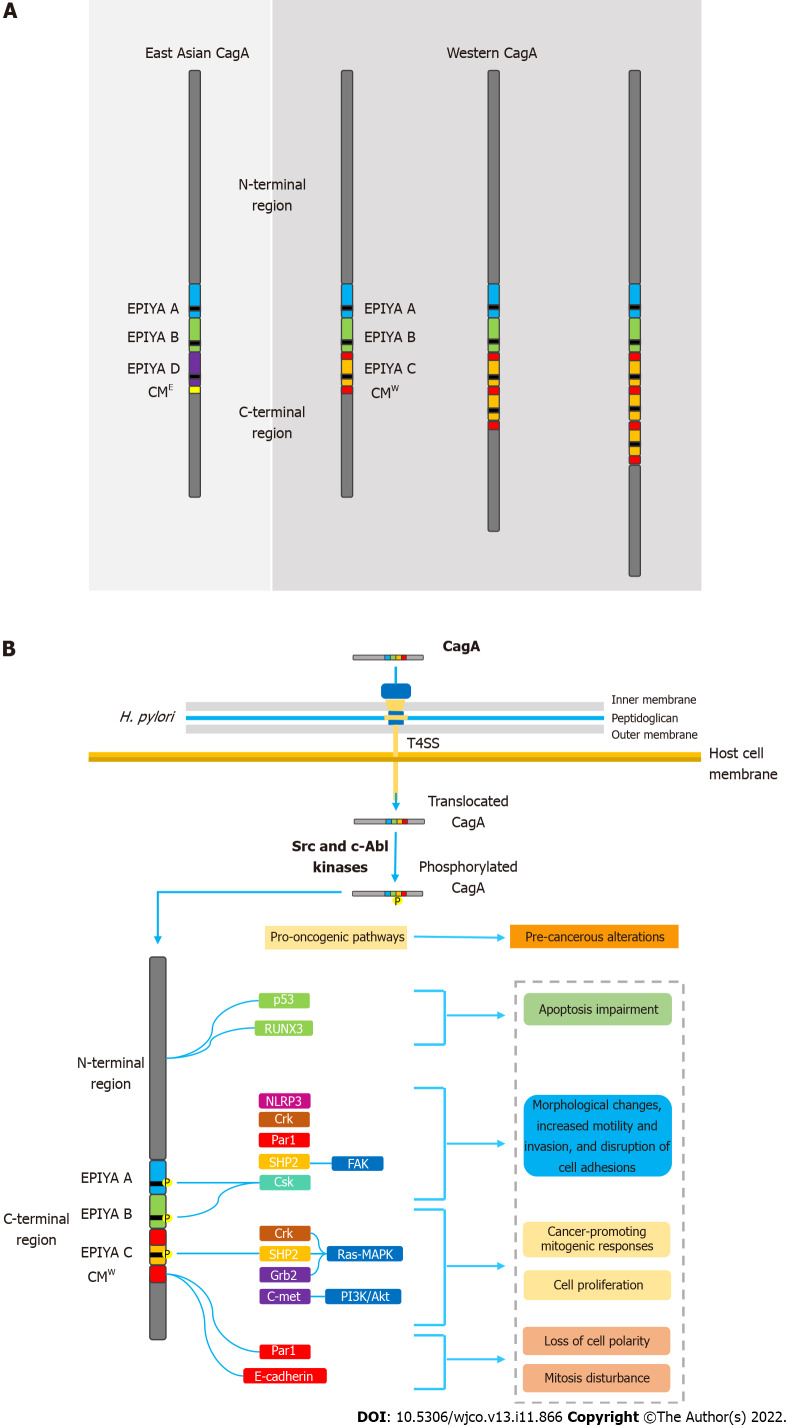

CagA is known to possess multiple phosphorylation segments in its tertiary structure. The phosphorylation sites are denominated EPIYA sequences; regions consisting of five amino acids (Glu-Pro-Ile-Tyr-Ala) located in the C-terminal portion of the oncoprotein. Four different EPIYA segments have been described according to the different amino acid sequences surrounding each motif, designated EPIYA-A (32 amino acids), B (40 amino acids), C (34 amino acids) and D (42 amino acids). EPIYA-A and EPIYA-B motifs have been identified in almost all CagA-positive H. pylori strains, followed by one, two, or three EPIYA-C sequences in western strains, or an EPIYA-D segment in East Asian strains[56,57]. Figure 1A summarizes the main structural domain differences between East Asian and western CagA.

Figure 1.

Helicobacter pylori oncoprotein: molecular structure and CagA-mediated carcinogenesis underlying mechanisms. A: Structural domain differences between East Asian and western CagA. CagA tertiary structure is characterized by a structured N-terminal region and an unstructured C-terminal tail. The oncoprotein contains repetitive sequences in its C-terminal polymorphic region, known as the EPIYA motifs and CM motif. EPIYA-A and EPIYA-B motifs were identified in almost all CagA-positive H. pylori strains, followed by one, two, or three EPIYA-C sequences in western strains, or an EPIYA-D segment in East Asian strains. The CM motif, although highly conserved, possesses a 5-amino-acid difference between East Asian and western strains, hence distinguishing East Asian and Western CagA; B: Molecular mechanisms of CagA-mediated carcinogenesis. Upon translocation, CagA EPIYA motifs are tyrosine-phosphorylated by Src family or c-Abl kinases of the host cell. After phosphorylation, CagA localizes to the inner leaflet of the plasmatic membrane and acts as a promiscuous scaffold or hub protein that simultaneously disturbs multiple host signaling pathways, involved in regulation of a large range of cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. Ultimately, the disharmonic interaction between CagA and host proteins leads to pro-oncogenic cellular alterations. CM: CagA-multimerization; CMW: western CagA.

Once inside the gastric epithelial cells, the EPIYA segments are selectively tyrosine-phosphorylated by different kinases of the Src family (s-Src, Fyn, Lyn and Yes) or by Abl kinase of the host cells[58-61]. After the phosphorylation process, CagA moves to the cell membrane and acts as a promiscuous scaffold protein that simultaneously disturbs multiple signaling pathways, involved in the regulation of a large range of cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis[62].

In this sense, a better understanding of the molecular structure of CagA and the interactions promoted by CagA-positive H. pylori strains to prevail in the host organism may be essential in identifying variations in prognosis, disease severity, and mechanisms that may be beneficial to the host, according to infections by different H. pylori strains.

ROLE OF CagA IN GASTRIC CARCINOGENESIS

The translocated effector protein CagA was found to be associated with gastric cancer development even before the initial elucidation of its pathogenic mechanisms[63,64]. Initially, the correlation between infection with CagA-positive H. pylori strains and carcinogenesis in vivo was established by experiments in Mongolian gerbil models[65-67]. More recently, transgenic expression of CagA in mice and zebrafish has also been shown to be associated with the development of gastric and hematopoietic neoplasms[68,69]. Thereby, the oncogenic potential of the bacterial protein has become increasingly evident and, at the same time, different studies have sought to clarify its underlying mechanisms. Nowadays, CagA is considered a pathological analog of a scaffold or hub protein capable of disrupting multiple host signaling pathways and promoting a pro-oncogenic microenvironment[70].

Upon translocation, CagA localizes to the inner surface of the plasmatic membrane, where it undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation by multiple members of the Src family kinases and c-Abl kinases[8,10,59,61]. As mentioned above, four different EPIYA segments were described according to the different amino acid sequences surrounding each motif, designated EPIYA-A–EPIYA-D[56,57]. Strains containing EPIYA-D or at least two EPIYA-C motifs are known to be associated with an increased risk of developing precancerous lesions and gastric cancer[71-75]. Queiroz et al[75] demonstrated in a Brazilian population that first-degree relatives of patients with gastric cancer were significantly and independently more frequently colonized by H. pylori strains with higher numbers of CagA EPIYA-C segments, which may be associated with an enhanced risk of developing this neoplasm[76].

Following tyrosine phosphorylation, EPIYA-C and D motifs acquire the ability to interact with SHP2 and induce pathological intracellular signaling[9]. Abnormal SHP2 activity leads to aberrant activation of the Ras–MAPK pathway, which has been associated with accelerated cell cycle progression and enhanced cell proliferation. CagA-activated SHP2 is also able to interact with proteins such as focal adhesion kinase, thence leading to cell elongation, increased motility, and cytoskeleton rearrangements[77,78]. All these pathological alterations in cell biology increase the risk of damaged cells acquiring precancerous genetic changes[79]. It is worth mentioning that CagA possessing EPIYA-D or a higher number of EPIYA-C segments binds more robustly to SHP2, which may explain their association with higher risk of gastric cancer development[8]. It has also been described that EPIYA-A and B motifs are able to interact with the SH2 domains of the tyrosine-protein kinase Csk, thereby inducing damage to actin binding proteins such as cortactin and vinculin. Consequently, rearrangements in the cytoskeleton reduce cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix and increase cell motility[80]. A recent study observed that H. pylori, through the T4SS encoded by cagPAI, interferes with the activity of cortectin binding partners, and stimulates overexpression of this molecule and promotes alterations in the actin cytoskeleton that may favor cell adhesion, motility and invasion of tumor cells contributing to the development of gastric cancer[81].

Recent studies have described that SHIP2, an SH2-containing phosphatidylinositol 5′-phosphatase, is a previously undiscovered CagA binding protein. Similar to SHP2, the SHIP2 protein is able to bind to EPIYA-C and D motifs in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner. In contrast, SHIP2 binds more robustly to EPIYA-C than to EPIYA-D sequences, thereby inducing changes in membrane phosphatidylinositol composition. This process enhances the subsequent delivery of CagA to the host cell, which binds to and dysregulates SHP2[82].

Other mechanisms have also been related to the aberrant induction of morphological changes, increased motility and cell proliferation[83]. In a tyrosine-phosphorylation-dependent manner, the interaction of CagA with the adapter molecule Crk is known to drive abnormal cell proliferation via MAPK signaling. Furthermore, the activation of Crk signaling pathways lead to the loss of cell–cell adhesion, hence inducing cell scattering/hummingbird phenotype and cell–cell dissociation[84]. It is important to mention that the EPIYA motif that corresponds to the binding site Csk has not been identified yet. In contrast, activation of the growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) protein and the C-Met oncogene in a tyrosine-phosphorylation-independent manner can also lead to similar pathological effects, highlighting the multiplicity of pro-oncogenic mechanisms of CagA[85,86]. Grb2 is an important regulator of Ras–MAPK pathway activation, capable of deregulating cell proliferation. Activation of C-Met-mediated PI3K/Akt signaling is associated with cancer-promoting mitogenic and inflammatory response[87-91].

The ability of CagA to disrupt the epithelial barrier has also been widely linked to its carcinogenic potential. In addition to the EPIYA sequences, the oncoprotein contains another repetitive sequence in its C-terminal polymorphic region, known as the CagA-multimerization (CM) motif[90]. With its number varying between different strains, the CM motif is composed of a 16-amino-acid sequence located downstream of the last EPIYA sequence[89]. This sequence, although highly conserved, possesses a 5-amino-acid difference between East Asian and western strains, hence distinguishing East Asian and western CagA (CMW)[91]. Thus, higher number of EPIYA-C motifs also increases the number of CM motifs in the CMW. The CM motif is identified as the main mediator of the interaction between CagA and the partitioning-defective 1 (PAR1)/microtubule affinity-regulating kinase, which plays a pivotal role in establishing epithelial polarity. As a result, there is loss of cell polarity, as well as induction of morphological alterations also associated with the hummingbird phenotype[92]. CagA-mediated PAR1 inhibition also disrupts mitosis, causing increased cell division and impaired segregation of sister chromatids, thus leading to chromosomal instability (CI)[93]. Currently, CI is widely recognized for its multifactorial role in carcinogenesis and its microenvironment[94].

From a different perspective, there is also a dangerous association between CM motifs and E-cadherin, a key protein in establishing cell polarity and maintaining epithelial integrity and differentiation[95-97]. It has been described that the CagA–E-cadherin interaction downregulates the β-catenin signal that promotes intestinal transdifferentiation in gastric epithelial cells. Therefore, it was inferred that the oncoprotein plays an important role in the development of intestinal metaplasia, a precancerous transdifferentiation of gastric epithelial cells from which intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma emerges[98].

Also in this sense, a recent study observed that CagA seems to be able to induce gastric carcinogenesis by stimulating the migration of cancer cells through the activation of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome. The authors reported that CagA also participates in the generation of intracellular ROS and that ROS inhibition has the potential to disrupt the NLRP3 pathway and pyroptosis. With these findings, the authors concluded that NLRP3 plays a key role in the action of CagA on gastric cells and that silencing NLRP3 can limit the effects of migration and invasion of cancer cells caused by CagA[99].

It is worth emphasizing the ability of CagA to activate a variety of antiapoptotic pathways, upon interaction of its N-terminal portion with various tumor suppressor factors. For example, it is well described that CagA is able to impair the antiapoptotic activity of the tumor suppressor factor p53. CagA protein induces degradation of p53 protein in both ASPP2- and p14ARF-dependent manners[100,101]. Furthermore, it is known that the interaction of the oncoprotein with Runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3) is able to induce the ubiquitination and degradation of RUNX3 that blocks its antitumoral activity[102]. Figure 1B summarizes the main molecular mechanisms of CagA-mediated carcinogenesis.

Another important potential of CagA associated with gastric cancer pathogenesis is the ability to drive epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT); a phenomenon extensively related to carcinogenesis[103,104]. EMT is the result of a complex molecular program that allows cancer cells to suppress their epithelial characteristics, transforming themselves into mesenchymal epithelial cells. This change allows the cells to acquire motility, invasiveness, greater resistance to apoptosis, and the ability to migrate from the primary site[104,105]. In this regard, it has been shown that EMT gene expression is upregulated in gastric epithelial cells infected with H. pylori CagA-positive strains[106]. Nevertheless, multiple pathogenic mechanisms have been described, including reduction of glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and triggering of the YAP oncogenic pathway, for example. However, the multiplicity of processes involved in EMT and its role in gastric cancer development still requires further explanation[107,108].

Recent studies have not been limited to pathogen–host interactions in H. pylori infection, but have also investigated the mechanisms regulating bacterial virulence factors, such as CagA, and their relation to carcinogenesis. Eisenbart et al[11] identified a conserved, abundant nickel-regulated sRNA and named it NikS (nickel-regulated sRNA), whose expression is transcriptionally modulated based on the size of a variable thymine stretch in its promoter region. NikS, in dependence on nickel availability, directly represses several virulence factors of H. pylori, including the oncoprotein, CagA, and its effects on host cell internalization and epithelial barrier disruption. In this sense, multiple clinical repercussions of post-transcriptional modulation of CagA by NikS can be hypothesized, including decreased activation of procarcinogenic signaling. Kinoshita-Daitoku et al[109] described that NikS expression is lower in clinical isolates from gastric cancer patients than in isolates from noncancer patients, while the expression of virulence factors targeted by NikS, including CagA, is increased in isolates from gastric cancer patients. This field needs to be better explored, especially regarding the correlation of NikS with the multiple virulence factors of H. pylori and its potential clinical repercussions.

CAGA-MEDIATED HIT-AND-RUN CARCINOGENESIS

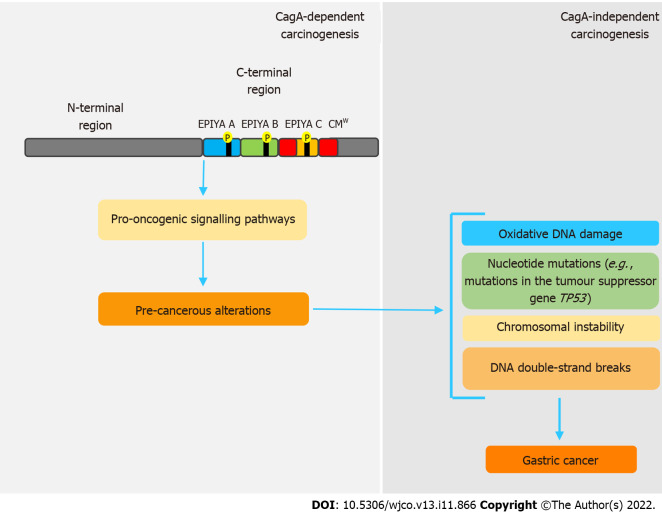

Even though CagA is notably a pro-oncogenic virulence factor, once gastric cancer sets in, its perpetuation is independent of the presence of this oncoprotein. In this sense, genetic and epigenetic changes caused by CagA seem to be responsible for this process, in a mechanism called “hit-and-run” carcinogenesis[58,92], firstly proposed by Skinner[110] for virus-induced cancers. Apparently, these changes are intrinsically related to disorders in the expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a crucial enzyme in the processes of somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination of immunoglobulin genes in B cells[111,112]. Matsumoto et al[111] state that cagA-positive H. pylori induces disordered expression of AID via NF-B, which consequently leads to various nucleotide mutations, such as in the tumor suppressor gene TP53. cagA-positive H. pylori strains are also related to oxidative DNA damage, because they are able to promote increased levels of H2O2 and downregulation of heme oxygenase-1[89,113]. CagA also inhibits PAR1 kinase, leading to microtubule-based spindle dysfunction and consequent CI[93].

Some studies have shown that H. pylori can also promote DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in host cells[114,115], but whether or not this feature is CagA-related remains uncertain. However, a recent study showed that inhibition of PAR1b kinase by CagA hindered BRCA1 gene phosphorylation, which leads to a BRCAness picture that, in turn, induces DSBs[116]. All these genetic and epigenetic changes support the hit-and-run mechanism, in which, regardless of the presence of CagA, the established pro-oncogenic environment maintains the acquired phenotype. Figure 2 summarizes the main features regarding CagA-mediated hit and run carcinogenesis mechanism.

Figure 2.

Simplified model of CagA-mediated hit-and-run carcinogenesis. The pro-oncogenic properties of CagA are already well established. However, genetic and epigenetic alterations caused by this oncoprotein provide a favorable environment for carcinogenesis, independently of its presence, in a hit-and-run carcinogenesis mechanism. In this sense, through interaction with various host proteins, CagA leads to chromosomal instability, double-strand breaks and repeated nucleotide mutations, which are correlated to gastric cancer development. CMW: western CagA.

CONCLUSION

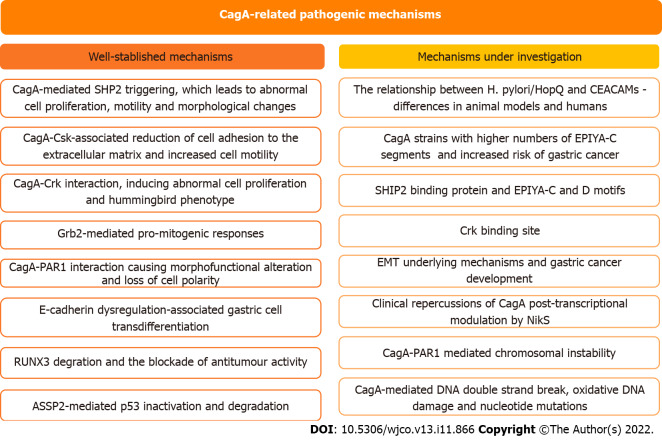

In this study, we address the role of CagA in the development of H. pylori-mediated gastric carcinogenesis and discuss the perspectives in this field of study (Figure 3). CagA undergoes important translocation and tyrosine phosphorylation before disrupting several cell signaling pathways and promoting protein dysfunction. However, there is still much to be clarified regarding the steps involved in the role of CagA in gastric carcinogenesis. Recent discoveries such as the identification of the SHIP2 binding protein capable of binding to the EPIYA-C and D motifs and potentiating the delivery of CagA to infected cells, or discovery of the instability between the H. pylori HopQ and CEACAM relationship, are significant findings that can generate advances in the area, and therefore, need to be investigated in more depth. Exploration of the little-known field of regulatory RNAs seems promising for a broader understanding of the control mechanisms involved in H. pylori infection and CagA levels and has the potential to identify factors with important clinical repercussions for conditions such as gastric cancer. Finally, the ability of H. pylori to evolve as a pathogenic bacterium and as a carcinogen is undeniable, therefore, it is essential to clarify what is still unclear about the subject and periodically monitor the behavior of the bacterium in the infection, the molecular processes and elements such as CagA to advance the diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

Figure 3.

Status of the current understanding regarding CagA-related pathogenic mechanisms. EMT: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition; CEACAMs: Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules; Grb2: Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; ASPP2: Apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 2; SHP2: Domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2; SHIP2: Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol 5'-phosphatase 2; RUNX3: Runt-related transcription factor 3; PAR1: Partitioning-defective 1; NikS: Nickel-regulated sRNA.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: August 6, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Article in press: October 11, 2022

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bataga SM, Romania; Fujimori S, Japan; Kirkik D, Turkey; SathiyaNarayanan R, India S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Gao CC

Contributor Information

Fabrício Freire de Melo, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Brazil. freiremeloufba@gmail.com.

Hanna Santos Marques, Campus Vitória da Conquista, Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Brazil.

Samuel Luca Rocha Pinheiro, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Brazil.

Fabian Fellipe Bueno Lemos, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Brazil.

Marcel Silva Luz, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Brazil.

Kádima Nayara Teixeira, Campus Toledo, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Toledo 85919899, Brazil.

Cláudio Lima Souza, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Brazil.

Márcio Vasconcelos Oliveira, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Brazil.

References

- 1.Sitkin S, Lazebnik L, Avalueva E, Kononova S, Vakhitov T. Gastrointestinal microbiome and Helicobacter pylori: Eradicate, leave it as it is, or take a personalized benefit-risk approach? World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:766–774. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i7.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzahrani S, Lina TT, Gonzalez J, Pinchuk IV, Beswick EJ, Reyes VE. Effect of Helicobacter pylori on gastric epithelial cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12767–12780. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warsinggih , Syarifuddin E, Marhamah , Lusikooy RE, Labeda I, Sampetoding S, Dani MI, Kusuma MI, Uwuratuw JA, Prihantono , Faruk M. Association of clinicopathological features and gastric cancer incidence in a single institution. Asian J Surg. 2022;45:246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sgouras DN, Trang TT, Yamaoka Y. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Helicobacter. 2015;20 Suppl 1:8–16. doi: 10.1111/hel.12251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alipour M. Molecular Mechanism of Helicobacter pylori-Induced Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2021;52:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s12029-020-00518-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backert S, Tegtmeyer N, Fischer W. Composition, structure and function of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island encoded type IV secretion system. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:955–965. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selbach M, Moese S, Hauck CR, Meyer TF, Backert S. Src is the kinase of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6775–6778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higashi H, Tsutsumi R, Muto S, Sugiyama T, Azuma T, Asaka M, Hatakeyama M. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Science. 2002;295:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1067147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tammer I, Brandt S, Hartig R, König W, Backert S. Activation of Abl by Helicobacter pylori: a novel kinase for CagA and crucial mediator of host cell scattering. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1309–1319. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenbart SK, Alzheimer M, Pernitzsch SR, Dietrich S, Stahl S, Sharma CM. A Repeat-Associated Small RNA Controls the Major Virulence Factors of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Cell. 2020;80:210–226.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camilo V, Sugiyama T, Touati E. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2017;22 Suppl 1 doi: 10.1111/hel.12405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bamford KB, Fan X, Crowe SE, Leary JF, Gourley WK, Luthra GK, Brooks EG, Graham DY, Reyes VE, Ernst PB. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:482–492. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton KA, Morgan DR, Krakowka S. Motility as a factor in the colonisation of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:123–127. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-2-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee AY, Kao CY, Wang YK, Lin SY, Lai TY, Sheu BS, Lo CJ, Wu JJ. Inactivation of ferric uptake regulator (Fur) attenuates Helicobacter pylori J99 motility by disturbing the flagellar motor switch and autoinducer-2 production. Helicobacter. 2017;22 doi: 10.1111/hel.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong Y, Anderl F, Kruse T, Schindele F, Jagusztyn-Krynicka EK, Fischer W, Gerhard M, Mejías-Luque R. Helicobacter pylori HP0231 Influences Bacterial Virulence and Is Essential for Gastric Colonization. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aizawa SI, Harwood CS, Kadner RJ. Signaling components in bacterial locomotion and sensory reception. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1459–1471. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1459-1471.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abedrabbo S, Castellon J, Collins KD, Johnson KS, Ottemann KM. Cooperation of two distinct coupling proteins creates chemosensory network connections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:2970–2975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618227114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker KW, Skaar EP. Metal limitation and toxicity at the interface between host and pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:1235–1249. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eaton KA, Brooks CL, Morgan DR, Krakowka S. Essential role of urease in pathogenesis of gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2470–2475. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2470-2475.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson JW, Maier RJ. Molecular hydrogen as an energy source for Helicobacter pylori. Science. 2002;298:1788–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1077123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira AG, Santos A, Guerra JB, Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Oliveira CA, Cabral MM, Nogueira AM, Queiroz DM. babA2- and cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains are associated with duodenal ulcer and gastric carcinoma in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3964–3966. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3964-3966.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahdavi J, Sondén B, Hurtig M, Olfat FO, Forsberg L, Roche N, Angstrom J, Larsson T, Teneberg S, Karlsson KA, Altraja S, Wadström T, Kersulyte D, Berg DE, Dubois A, Petersson C, Magnusson KE, Norberg T, Lindh F, Lundskog BB, Arnqvist A, Hammarström L, Borén T. Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science. 2002;297:573–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1069076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Javaheri A, Kruse T, Moonens K, Mejías-Luque R, Debraekeleer A, Asche CI, Tegtmeyer N, Kalali B, Bach NC, Sieber SA, Hill DJ, Königer V, Hauck CR, Moskalenko R, Haas R, Busch DH, Klaile E, Slevogt H, Schmidt A, Backert S, Remaut H, Singer BB, Gerhard M. Helicobacter pylori adhesin HopQ engages in a virulence-enhancing interaction with human CEACAMs. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16189. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Königer V, Holsten L, Harrison U, Busch B, Loell E, Zhao Q, Bonsor DA, Roth A, Kengmo-Tchoupa A, Smith SI, Mueller S, Sundberg EJ, Zimmermann W, Fischer W, Hauck CR, Haas R. Helicobacter pylori exploits human CEACAMs via HopQ for adherence and translocation of CagA. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16188. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Brito BB, da Silva FAF, Soares AS, Pereira VA, Santos MLC, Sampaio MM, Neves PHM, de Melo FF. Pathogenesis and clinical management of Helicobacter pylori gastric infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:5578–5589. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i37.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atherton JC, Peek RM Jr, Tham KT, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vacA, the vacuolating cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:92–99. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djekic A, Müller A. The Immunomodulator VacA Promotes Immune Tolerance and Persistent Helicobacter pylori Infection through Its Activities on T-Cells and Antigen-Presenting Cells. Toxins (Basel) 2016;8 doi: 10.3390/toxins8060187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farzi N, Yadegar A, Aghdaei HA, Yamaoka Y, Zali MR. Genetic diversity and functional analysis of oipA gene in association with other virulence factors among Helicobacter pylori isolates from Iranian patients with different gastric diseases. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;60:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miftahussurur M, Yamaoka Y, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori as an oncogenic pathogen, revisited. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2017;19:e4. doi: 10.1017/erm.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshikawa T, Naito Y. The role of neutrophils and inflammation in gastric mucosal injury. Free Radic Res. 2000;33:785–794. doi: 10.1080/10715760000301301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith SM. Role of Toll-like receptors in Helicobacter pylori infection and immunity. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5:133–146. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith MF Jr, Mitchell A, Li G, Ding S, Fitzmaurice AM, Ryan K, Crowe S, Goldberg JB. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR5, but not TLR4, are required for Helicobacter pylori-induced NF-kappa B activation and chemokine expression by epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32552–32560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson KT, Ramanujam KS, Mobley HL, Musselman RF, James SP, Meltzer SJ. Helicobacter pylori stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and activity in a murine macrophage cell line. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1524–1533. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindholm C, Quiding-Järbrink M, Lönroth H, Hamlet A, Svennerholm AM. Local cytokine response in Helicobacter pylori-infected subjects. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5964–5971. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5964-5971.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon BREA, Hossain R, Patel RV, Algood HMS. Th17 Cells in Helicobacter pylori Infection: a Dichotomy of Help and Harm. Infect Immun. 2019;87 doi: 10.1128/IAI.00363-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinchuk IV, Morris KT, Nofchissey RA, Earley RB, Wu JY, Ma TY, Beswick EJ. Stromal cells induce Th17 during Helicobacter pylori infection and in the gastric tumor microenvironment. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freire de Melo F, Rocha AM, Rocha GA, Pedroso SH, de Assis Batista S, Fonseca de Castro LP, Carvalho SD, Bittencourt PF, de Oliveira CA, Corrêa-Oliveira R, Magalhães Queiroz DM. A regulatory instead of an IL-17 T response predominates in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis in children. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rocha GA, de Melo FF, Cabral MMDA, de Brito BB, da Silva FAF, Queiroz DMM. Interleukin-27 is abrogated in gastric cancer, but highly expressed in other Helicobacter pylori-associated gastroduodenal diseases. Helicobacter. 2020;25:e12667. doi: 10.1111/hel.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao W, Ma ZS. Influences of Helicobacter pylori infection on diversity, heterogeneity, and composition of human gastric microbiomes across stages of gastric cancer development. Helicobacter. 2022;27:e12899. doi: 10.1111/hel.12899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu C, Ng SK, Ding Y, Lin Y, Liu W, Wong SH, Sung JJ, Yu J. Meta-analysis of mucosal microbiota reveals universal microbial signatures and dysbiosis in gastric carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2022;41:3599–3610. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02377-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo Y, Cao XS, Guo GY, Zhou MG, Yu B. Effect of Helicobacter Pylori Eradication on Human Gastric Microbiota: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:899248. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.899248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen CC, Liou JM, Lee YC, Hong TC, El-Omar EM, Wu MS. The interplay between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1–22. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1909459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montecucco C, Rappuoli R. Living dangerously: how Helicobacter pylori survives in the human stomach. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:457–466. doi: 10.1038/35073084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Backert S, Tegtmeyer N, Selbach M. The versatility of Helicobacter pylori CagA effector protein functions: The master key hypothesis. Helicobacter. 2010;15:163–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree JE, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Odenbreit S, Püls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Backert S, Ziska E, Brinkmann V, Zimny-Arndt U, Fauconnier A, Jungblut PR, Naumann M, Meyer TF. Translocation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in gastric epithelial cells by a type IV secretion apparatus. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:155–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hatakeyama M. Anthropological and clinical implications for the structural diversity of the Helicobacter pylori CagA oncoprotein. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:36–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi-Kanemitsu A, Knight CT, Hatakeyama M. Molecular anatomy and pathogenic actions of Helicobacter pylori CagA that underpin gastric carcinogenesis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:50–63. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwok T, Zabler D, Urman S, Rohde M, Hartig R, Wessler S, Misselwitz R, Berger J, Sewald N, König W, Backert S. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature. 2007;449:862–866. doi: 10.1038/nature06187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiménez-Soto LF, Kutter S, Sewald X, Ertl C, Weiss E, Kapp U, Rohde M, Pirch T, Jung K, Retta SF, Terradot L, Fischer W, Haas R. Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion apparatus exploits beta1 integrin in a novel RGD-independent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000684. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Couturier MR, Tasca E, Montecucco C, Stein M. Interaction with CagF is required for translocation of CagA into the host via the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system. Infect Immun. 2006;74:273–281. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.273-281.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shrestha R, Murata-Kamiya N, Imai S, Yamamoto M, Tsukamoto T, Nomura S, Hatakeyama M. Mouse Gastric Epithelial Cells Resist CagA Delivery by the Helicobacter pylori Type IV Secretion System. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms23052492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharafutdinov I, Backert S, Tegtmeyer N. The Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system upregulates epithelial cortactin expression by a CagA- and JNK-dependent pathway. Cell Microbiol. 2021;23:e13376. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hatakeyama M. Oncogenic mechanisms of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:688–694. doi: 10.1038/nrc1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Argent RH, Hale JL, El-Omar EM, Atherton JC. Differences in Helicobacter pylori CagA tyrosine phosphorylation motif patterns between western and East Asian strains, and influences on interleukin-8 secretion. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1062–1067. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/001818-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mueller D, Tegtmeyer N, Brandt S, Yamaoka Y, De Poire E, Sgouras D, Wessler S, Torres J, Smolka A, Backert S. c-Src and c-Abl kinases control hierarchic phosphorylation and function of the CagA effector protein in Western and East Asian Helicobacter pylori strains. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1553–1566. doi: 10.1172/JCI61143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stein M, Bagnoli F, Halenbeck R, Rappuoli R, Fantl WJ, Covacci A. c-Src/Lyn kinases activate Helicobacter pylori CagA through tyrosine phosphorylation of the EPIYA motifs. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:971–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tegtmeyer N, Backert S. Role of Abl and Src family kinases in actin-cytoskeletal rearrangements induced by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:880–890. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poppe M, Feller SM, Römer G, Wessler S. Phosphorylation of Helicobacter pylori CagA by c-Abl leads to cell motility. Oncogene. 2007;26:3462–3472. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA and gastric cancer: a paradigm for hit-and-run carcinogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, Cover TL, Peek RM, Chyou PH, Stemmermann GN, Nomura A. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2111–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Orentreich N, Vogelman H. Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1997;40:297–301. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, Sasaki S, Nakao M. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:642–648. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peek RM Jr, Wirth HP, Moss SF, Yang M, Abdalla AM, Tham KT, Zhang T, Tang LH, Modlin IM, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori alters gastric epithelial cell cycle events and gastrin secretion in Mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:48–59. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ogura K, Maeda S, Nakao M, Watanabe T, Tada M, Kyutoku T, Yoshida H, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori responsible for gastric diseases in Mongolian gerbil. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1601–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ohnishi N, Yuasa H, Tanaka S, Sawa H, Miura M, Matsui A, Higashi H, Musashi M, Iwabuchi K, Suzuki M, Yamada G, Azuma T, Hatakeyama M. Transgenic expression of Helicobacter pylori CagA induces gastrointestinal and hematopoietic neoplasms in mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1003–1008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711183105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neal JT, Peterson TS, Kent ML, Guillemin K. H. pylori virulence factor CagA increases intestinal cell proliferation by Wnt pathway activation in a transgenic zebrafish model. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:802–810. doi: 10.1242/dmm.011163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Amieva M, Peek RM Jr. Pathobiology of Helicobacter pylori-Induced Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:64–78. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamaoka Y, El-Zimaity HM, Gutierrez O, Figura N, Kim JG, Kodama T, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relationship between the cagA 3' repeat region of Helicobacter pylori, gastric histology, and susceptibility to low pH. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:342–349. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Basso D, Zambon CF, Letley DP, Stranges A, Marchet A, Rhead JL, Schiavon S, Guariso G, Ceroti M, Nitti D, Rugge M, Plebani M, Atherton JC. Clinical relevance of Helicobacter pylori cagA and vacA gene polymorphisms. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:91–99. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sicinschi LA, Correa P, Peek RM, Camargo MC, Piazuelo MB, Romero-Gallo J, Hobbs SS, Krishna U, Delgado A, Mera R, Bravo LE, Schneider BG. CagA C-terminal variations in Helicobacter pylori strains from Colombian patients with gastric precancerous lesions. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Batista SA, Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Saraiva IE, Cabral MM, Oliveira RC, Queiroz DM. Higher number of Helicobacter pylori CagA EPIYA C phosphorylation sites increases the risk of gastric cancer, but not duodenal ulcer. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Queiroz DM, Silva CI, Goncalves MH, Braga-Neto MB, Fialho AB, Fialho AM, Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Batista SA, Guerrant RL, Lima AA, Braga LL. Higher frequency of cagA EPIYA-C phosphorylation sites in H. pylori strains from first-degree relatives of gastric cancer patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Gomes AD, Faria CL Jr, Melo FF, Batista SA, Fernandes VC, Almeida NB, Teixeira KN, Brito KS, Queiroz DM. STAT3 polymorphism and Helicobacter pylori CagA strains with higher number of EPIYA-C segments independently increase the risk of gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:528. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1533-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14559–14564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsutsumi R, Takahashi A, Azuma T, Higashi H, Hatakeyama M. Focal adhesion kinase is a substrate and downstream effector of SHP-2 complexed with Helicobacter pylori CagA. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:261–276. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.261-276.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Naito M, Yamazaki T, Tsutsumi R, Higashi H, Onoe K, Yamazaki S, Azuma T, Hatakeyama M. Influence of EPIYA-repeat polymorphism on the phosphorylation-dependent biological activity of Helicobacter pylori CagA. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1181–1190. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tsutsumi R, Higashi H, Higuchi M, Okada M, Hatakeyama M. Attenuation of Helicobacter pylori CagA x SHP-2 signaling by interaction between CagA and C-terminal Src kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3664–3670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tegtmeyer N, Harrer A, Rottner K, Backert S. Helicobacter pylori CagA Induces Cortactin Y-470 Phosphorylation-Dependent Gastric Epithelial Cell Scattering via Abl, Vav2 and Rac1 Activation. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/cancers13164241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fujii Y, Murata-Kamiya N, Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA oncoprotein interacts with SHIP2 to increase its delivery into gastric epithelial cells. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:1596–1606. doi: 10.1111/cas.14391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stein M, Ruggiero P, Rappuoli R, Bagnoli F. Helicobacter pylori CagA: From Pathogenic Mechanisms to Its Use as an Anti-Cancer Vaccine. Front Immunol. 2013;4:328. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Suzuki M, Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Park M, Yamamoto T, Sasakawa C. Interaction of CagA with Crk plays an important role in Helicobacter pylori-induced loss of gastric epithelial cell adhesion. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1235–1247. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Tanaka J, Asahi M, Haas R, Sasakawa C. Grb2 is a key mediator of helicobacter pylori CagA protein activities. Mol Cell. 2002;10:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Churin Y, Al-Ghoul L, Kepp O, Meyer TF, Birchmeier W, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein targets the c-Met receptor and enhances the motogenic response. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:249–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Suzuki M, Mimuro H, Kiga K, Fukumatsu M, Ishijima N, Morikawa H, Nagai S, Koyasu S, Gilman RH, Kersulyte D, Berg DE, Sasakawa C. Helicobacter pylori CagA phosphorylation-independent function in epithelial proliferation and inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.DiDonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M. NF-κB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:379–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hatakeyama M. Structure and function of Helicobacter pylori CagA, the first-identified bacterial protein involved in human cancer. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2017;93:196–219. doi: 10.2183/pjab.93.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ren S, Higashi H, Lu H, Azuma T, Hatakeyama M. Structural basis and functional consequence of Helicobacter pylori CagA multimerization in cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32344–32352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lu HS, Saito Y, Umeda M, Murata-Kamiya N, Zhang HM, Higashi H, Hatakeyama M. Structural and functional diversity in the PAR1b/MARK2-binding region of Helicobacter pylori CagA. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2004–2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Saadat I, Higashi H, Obuse C, Umeda M, Murata-Kamiya N, Saito Y, Lu H, Ohnishi N, Azuma T, Suzuki A, Ohno S, Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA targets PAR1/MARK kinase to disrupt epithelial cell polarity. Nature. 2007;447:330–333. doi: 10.1038/nature05765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Umeda M, Murata-Kamiya N, Saito Y, Ohba Y, Takahashi M, Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA causes mitotic impairment and induces chromosomal instability. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22166–22172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bakhoum SF, Cantley LC. The Multifaceted Role of Chromosomal Instability in Cancer and Its Microenvironment. Cell. 2018;174:1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kurashima Y, Murata-Kamiya N, Kikuchi K, Higashi H, Azuma T, Kondo S, Hatakeyama M. Deregulation of beta-catenin signal by Helicobacter pylori CagA requires the CagA-multimerization sequence. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:823–831. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tian X, Liu Z, Niu B, Zhang J, Tan TK, Lee SR, Zhao Y, Harris DC, Zheng G. E-cadherin/β-catenin complex and the epithelial barrier. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:567305. doi: 10.1155/2011/567305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Carneiro P, Fernandes MS, Figueiredo J, Caldeira J, Carvalho J, Pinheiro H, Leite M, Melo S, Oliveira P, Simões-Correia J, Oliveira MJ, Carneiro F, Figueiredo C, Paredes J, Oliveira C, Seruca R. E-cadherin dysfunction in gastric cancer--cellular consequences, clinical applications and open questions. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2981–2989. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Murata-Kamiya N, Kurashima Y, Teishikata Y, Yamahashi Y, Saito Y, Higashi H, Aburatani H, Akiyama T, Peek RM Jr, Azuma T, Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA interacts with E-cadherin and deregulates the beta-catenin signal that promotes intestinal transdifferentiation in gastric epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:4617–4626. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang X, Li C, Chen D, He X, Zhao Y, Bao L, Wang Q, Zhou J, Xie Y. H. pylori CagA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to promote gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. Inflamm Res. 2022;71:141–155. doi: 10.1007/s00011-021-01522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Buti L, Spooner E, Van der Veen AG, Rappuoli R, Covacci A, Ploegh HL. Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) subverts the apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 (ASPP2) tumor suppressor pathway of the host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9238–9243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106200108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wei J, Noto JM, Zaika E, Romero-Gallo J, Piazuelo MB, Schneider B, El-Rifai W, Correa P, Peek RM, Zaika AI. Bacterial CagA protein induces degradation of p53 protein in a p14ARF-dependent manner. Gut. 2015;64:1040–1048. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tsang YH, Lamb A, Romero-Gallo J, Huang B, Ito K, Peek RM Jr, Ito Y, Chen LF. Helicobacter pylori CagA targets gastric tumor suppressor RUNX3 for proteasome-mediated degradation. Oncogene. 2010;29:5643–5650. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bagnoli F, Buti L, Tompkins L, Covacci A, Amieva MR. Helicobacter pylori CagA induces a transition from polarized to invasive phenotypes in MDCK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16339–16344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502598102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer: A Historical Overview. Transl Oncol. 2020;13:100773. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yin Y, Grabowska AM, Clarke PA, Whelband E, Robinson K, Argent RH, Tobias A, Kumari R, Atherton JC, Watson SA. Helicobacter pylori potentiates epithelial:mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer: links to soluble HB-EGF, gastrin and matrix metalloproteinase-7. Gut. 2010;59:1037–1045. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.199794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lee DG, Kim HS, Lee YS, Kim S, Cha SY, Ota I, Kim NH, Cha YH, Yang DH, Lee Y, Park GJ, Yook JI, Lee YC. Helicobacter pylori CagA promotes Snail-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition by reducing GSK-3 activity. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4423. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li N, Feng Y, Hu Y, He C, Xie C, Ouyang Y, Artim SC, Huang D, Zhu Y, Luo Z, Ge Z, Lu N. Helicobacter pylori CagA promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition in gastric carcinogenesis via triggering oncogenic YAP pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:280. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0962-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kinoshita-Daitoku R, Kiga K, Miyakoshi M, Otsubo R, Ogura Y, Sanada T, Bo Z, Phuoc TV, Okano T, Iida T, Yokomori R, Kuroda E, Hirukawa S, Tanaka M, Sood A, Subsomwong P, Ashida H, Binh TT, Nguyen LT, Van KV, Ho DQD, Nakai K, Suzuki T, Yamaoka Y, Hayashi T, Mimuro H. A bacterial small RNA regulates the adaptation of Helicobacter pylori to the host environment. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2085. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22317-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Skinner GR. Transformation of primary hamster embryo fibroblasts by type 2 simplex virus: evidence for a "hit and run" mechanism. Br J Exp Pathol. 1976;57:361–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Matsumoto Y, Marusawa H, Kinoshita K, Endo Y, Kou T, Morisawa T, Azuma T, Okazaki IM, Honjo T, Chiba T. Helicobacter pylori infection triggers aberrant expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in gastric epithelium. Nat Med. 2007;13:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nm1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chaturvedi R, Asim M, Romero-Gallo J, Barry DP, Hoge S, de Sablet T, Delgado AG, Wroblewski LE, Piazuelo MB, Yan F, Israel DA, Casero RA Jr, Correa P, Gobert AP, Polk DB, Peek RM Jr, Wilson KT. Spermine oxidase mediates the gastric cancer risk associated with Helicobacter pylori CagA. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1696–708.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hanada K, Uchida T, Tsukamoto Y, Watada M, Yamaguchi N, Yamamoto K, Shiota S, Moriyama M, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori infection introduces DNA double-strand breaks in host cells. Infect Immun. 2014;82:4182–4189. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02368-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hartung ML, Gruber DC, Koch KN, Grüter L, Rehrauer H, Tegtmeyer N, Backert S, Müller A. H. pylori-Induced DNA Strand Breaks Are Introduced by Nucleotide Excision Repair Endonucleases and Promote NF-κB Target Gene Expression. Cell Rep. 2015;13:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Imai S, Ooki T, Murata-Kamiya N, Komura D, Tahmina K, Wu W, Takahashi-Kanemitsu A, Knight CT, Kunita A, Suzuki N, Del Valle AA, Tsuboi M, Hata M, Hayakawa Y, Ohnishi N, Ueda K, Fukayama M, Ushiku T, Ishikawa S, Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA elicits BRCAness to induce genome instability that may underlie bacterial gastric carcinogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:941–958.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]