Abstract

Protein based therapeutics have successfully improved the quality of life for patients of monogenic disorders like hemophilia, Pompe and Fabry disease. However, a significant proportion of patients develop immune responses towards intravenously infused therapeutic protein, which can complicate or neutralize treatment and compromise patient safety. Strategies aimed at circumventing immune responses following therapeutic protein infusion can greatly improve therapeutic efficacy. In recent years, antigen-based oral tolerance induction has shown promising results in the prevention and treatment of autoimmune diseases, food allergies and can prevent anti-drug antibody formation to protein replacement therapies. Oral tolerance exploits regulatory mechanisms that are initiated in the gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) to promote active suppression of orally ingested antigen. In this review, we outline general perceptions and current knowledge about the mechanisms of oral tolerance, including tissue specific sites of tolerance induction and the cells involved, with emphasis on antigen presenting cells and regulatory T cells. We define several factors, such as cytokines and metabolites that impact the stability and expansion potential of these immune modulatory cells. We highlight preclinical studies that have been performed to induce oral tolerance to therapeutic proteins or enzymes for single gene disorders, such as hemophilia or Pompe disease. These studies mainly utilize a transgenic plant-based system for oral delivery of antigen in conjugation with fusion protein technology that favors the prevention of antigen degradation in the stomach while enhancing uptake in the small intestine by antigen presenting cells and regulatory T cell induction, thereby promoting antigen specific systemic tolerance.

Keywords: FVIII, FIX, enzyme replacement therapy, anti-drug antibody, oral tolerance, hemophilia, Pompe disease, Tregs, LAP, IL-10

1. Introduction

Therapeutic proteins have transformed the standard of care for many diseases. Intravenous infusion of essential replacement proteins or enzymes is a routine treatment for genetic deficiencies like hemophilia and lysosomal storage diseases. However, like any other biopharmaceutical drug, initiation of unwanted immune responses can result in the development of anti-drug antibodies (ADA) that compromise therapeutic efficacy [1–3]. ADAs against therapeutic proteins can be stratified into two groups, neutralizing ADA (nADAs) and binding ADAs (bADAs). nADAs directly affect the efficacy of the drug by binding to or preventing access to the drug’s active site, whereas bADAs indirectly reduce efficacy by accelerating clearance and/or compromising bioavailability. Overall, the formation of ADAs neutralizes the activity of therapeutic proteins, altering pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and can cause hypersensitivity reactions [4–7], or cross react with endogenous proteins [5]. Therefore, ADAs not only counteract the therapeutic effect of replacement proteins but can also affect safety of the treatment [8, 9]. Several factors, like treatment duration, mode, rate, route of administration and more specifically, type of therapeutic protein (e.g. monoclonal antibody vs recombinant protein) can influence the risk of immunogenicity [10]. For protein or enzyme replacement therapy in monogenic disorders, the major risk factor for immunogenicity is the absence of residual (functional or non-functional) cross-reactive immunological material (CRIM), which could result in the complete lack of production of native protein, translating to a lack of tolerance to replacement therapy. CRIM negative patients have a significantly higher preponderance for developing ADAs [11, 12].

The cost of treatment to eradicate established ADAs is very high, such as in the case of hemophilia (over $7,00,000/year/patient) [13]. Further, immune tolerance induction (ITI) protocols to mitigate ADAs are protracted (can last months to years), highly immunosuppressive (as in the case of Pompe disease) [14], and are not always effective, with little recourse available for patients who fail ITI [15]. Therefore, efforts to prophylactically prevent ADA formation are preferred to eliminating established ADAs. Non-specific immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, belimumab, rituximab, methotrexate, and rapamycin have been tested in animal models and in patients with lysosomal storage disease or hemophilia, which have shown mixed success and can pose an additional risk of secondary infections [16–26]. Developing a clinically feasible protocol that is acceptable for use in pediatric patients and avoids nonspecific immune suppression remains a challenge [27, 28]. There is therefore a need for novel and innovative antigen specific tolerance approaches that can work either as standalone or adjunctive therapy in combination with current treatment options.

A potentially ideal method to prevent ADA formation is oral tolerance, facilitated by the lack of toxicity, easy administration, and antigen specificity of this treatment approach. Oral tolerance is a physiological phenomenon defined by the active suppression of humoral and/ or cellular immune responses, production of inflammatory cytokines, or hypersensitivity reactions against food proteins and commensal microbiota [29]. In the case of therapeutic proteins, oral tolerance can technically be induced by prior administration of the antigen through the oral route, leading to tolerance which is not only restricted to the local intestinal tissue, but also encompasses systemic suppression [29]. Oral tolerance has shown promising results in animal models of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [30, 31], arthritis [32], diabetes [33], experimental colitis [34] and allergy [35], by suppressing humoral and cellular mediated immunity [36]. There are fewer studies addressing the role of oral tolerance in preventing ADA responses to therapeutic proteins, although promising initial findings warrant further research and/ or translational studies. In this review, we describe the currently known mechanisms for induction of oral tolerance to therapeutic proteins and the disease models tested.

2. Oral tolerance

2.1. History

In the first decade of the 20th century, Alexander Besredka first reported the induction of oral tolerance. He showed that guinea pigs that ingested milk became refractory to anaphylaxis stimulated by intracerebral injection of milk [37]. In 1911, Wells and Osbourne demonstrated that guinea pigs fed with corn-containing diet failed to develop anaphylaxis to the corn protein, zein [38]. But it was not until the early 1980s that use of the oral route was demonstrated to inhibit inflammatory diseases using animal models of arthritis [32, 39] and multiple sclerosis [30, 31]. Currently, oral tolerance has been applied to autoimmunity and inflammatory diseases such as peanut allergy [40, 41], allergic asthma [42, 43], pollen allergy [44], nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [45], Pompe disease [46], rheumatoid arthritis [47, 48], type I diabetes [49, 50], hemophilia A and B [51–54] in preclinical as well as clinical studies. Encouragingly, FDA approval of Palforzia (peanut Arachis Hypogaea, PTAH allergen powder) has shown that incremental oral antigen dosing desensitizes patients with peanut allergy and mitigates allergic reactions that may occur after accidental exposure to peanuts [55]. These findings should accelerate clinical oral immunotherapy treatments for other indications [41, 55, 56].

2.2. Mechanisms of Oral Tolerance

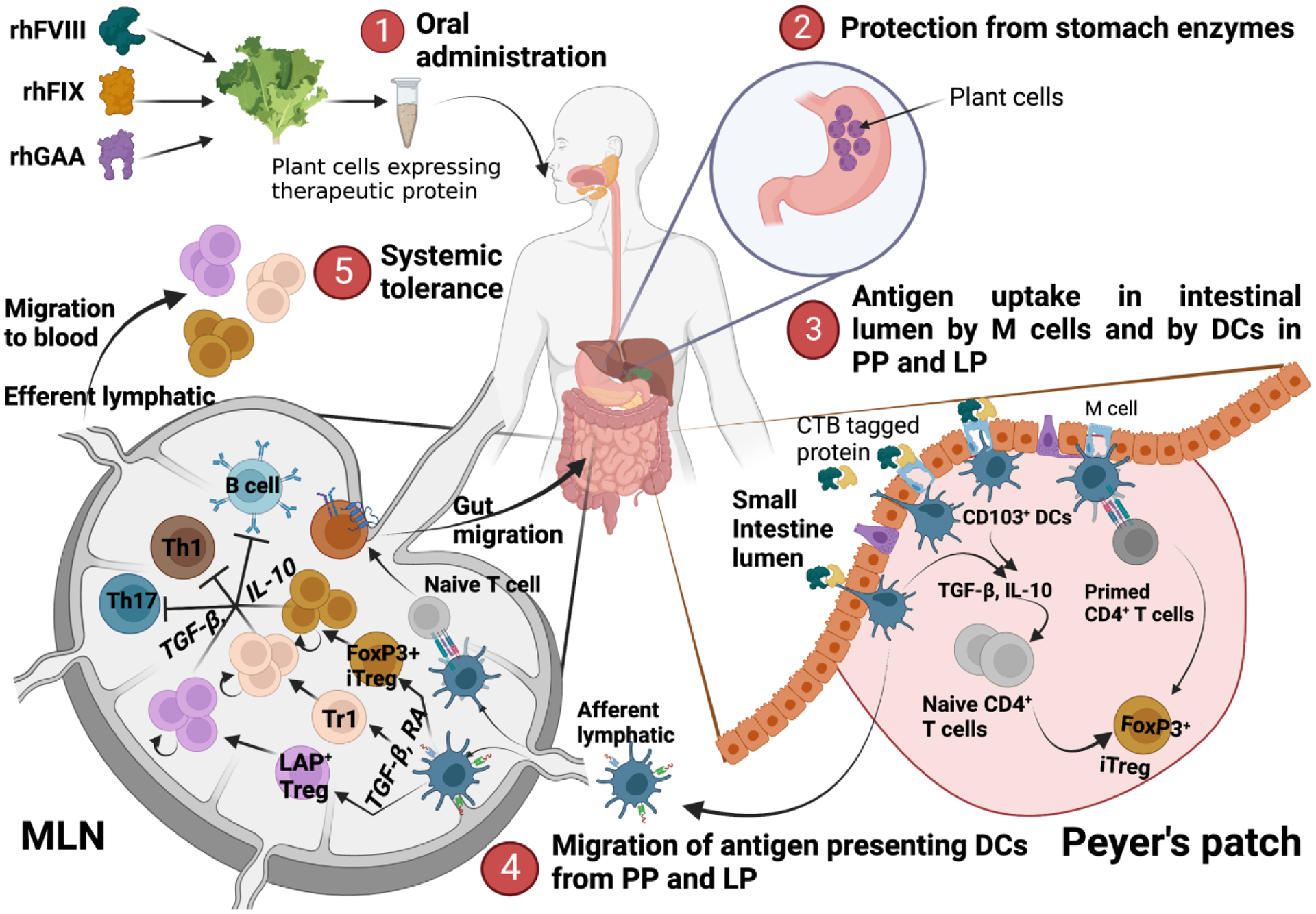

Oral tolerance is an active immunological process which is mediated by diverse mechanisms in a dose dependent manner. Orally administered antigens, like food antigens, can be taken up by the small intestine’s immune system, resulting in an immune regulatory response (Fig. 1). Earlier studies demonstrate that administration of target antigen at low doses favors induction of active regulation by regulatory T cells (Tregs) [57, 58], whereas high antigen doses directs the response towards deletion mediated by clonal anergy [59] or apoptosis [60]. However, these two forms of tolerance are not mutually exclusive, as Tregs can phenotypically and functionally present with an anergic profile [61, 62], whereas anergic T cells can convert into non-conventional Tregs [63]. Other factors affecting immunological outcomes following oral antigen administration are the nature of the antigen, the innate immune system, the genetic background and immunologic status of the host.

Fig. 1: Mechanism of oral tolerance induction to protein replacement therapy.

Mechanism of oral tolerance induction: 1) Oral administration of therapeutic proteins (FVIII, FIX or GAA) expressed in the chloroplast of lettuce plant leaves. 2) Prevention of therapeutic protein degradation in the stomach from the harsh acidic environment and digestive enzymes. 3) Uptake of therapeutic protein in the intestinal lumen directly by CD103+ DC or indirectly through absorption by M cells and transport to Peyer’s patches or lamina propria. Antigen presenting DCs prime naïve antigen specific cells leading to iTreg generation. 4) Migration of antigen presenting DCs to MLNs and induction of different subtypes of immunosuppressive CD4+ T cells including iTregs, LAP Tregs and Tr1 cells, along with CCR9 expressing gut migratory Tregs. 5) Migration of immunosuppressive T cell subtypes to the periphery to develop systemic tolerance.

2.2.1. Immune suppression by T cells

T cells play an important role in the induction and maintenance of oral tolerance through regulatory and or anergic/apoptotic processes. Thymically derived Tregs (tTregs) are primarily involved in preventing responses to self-antigen [64] while peripheral Tregs (pTregs) are induced in response to non-self-antigens, and are crucial in preventing immune responses to dietary antigens [65, 66]. A diverse group of pTregs, including both FoxP3+ and FoxP3− Treg, are involved in oral tolerance. These cells exhibit functional plasticity to adapt to a specific microenvironment and have overlapping functions. Gut-tropic FoxP3+ pTregs are mainly generated in mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) by differentiation of CD4+ T effector cells (Teff) in response to tolerogenic antigen presentation by dendritic cells (DCs). Following homing to the small intestine, pTregs expand and differentiate in response to IL-10 secreted by CX3CR1+ macrophages [67–69]. Additionally, a fraction of CD4+ T cells differentiate into FoxP3− Tregs expressing latency associated protein (LAP+), which have been demonstrated to play an important suppressive role following oral antigen administration [70] or oral anti-CD3 therapy [71, 72]. pTregs exert suppression through several mechanisms: i) inhibitory cytokine secretion prevents the proliferation of and proinflammatory cytokine production by Teffs; ii) expression of surface molecules CD39, CD73 and CD25 utilizes metabolites like ATP and deprives Teffs of IL-2 [73–75]; iii) downregulation of MHCII and costimulatory receptors on antigen presenting cells (APCs) inhibits antigen presentation [76–78].

Direct interaction of Tregs with APCs through co-inhibitory molecules like PD1, CTLA-4, and LAG3 attenuate the ability of APCs to interact with and activate Teffs [79–81]. Attenuated antigen presentation without costimulation results in a lasting state of unresponsiveness in Teffs called anergy. Anergic Teffs are antigen specific, as these cells can respond to presentation of a different antigen [82]. Anergic T cells produce low levels of cytokines like IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ and GM-CSF, and diminished responses to cytokines such as IL-4 [83, 84]. In patients with food allergy, oral administration of allergen leads to reduction in the production of Th2 skewing cytokines due to T cell anergy [85–87]. This is substantiated by the finding that patients with sustained oral tolerance to peanut allergen have an anergic memory CD4+ T cell phenotype with low expression of CD28, Ki67, CD69, CD45A, and reduced secretion of IL-4 and IL-13 [88].

Tregs also secrete cytotoxic molecules in close proximity to target cells to induce their apoptosis via a granzyme B dependent and perforin independent pathway [89, 90]. Watanabe and colleagues demonstrated that high dose oral administration leads to differentiation of Fas ligand (FasL) expressing CD4+ T cells which secrete IL-10, IL-4 and TGF-β; and depletion of antigen specific T cells via Fas-FasL mediated mechanisms [91]. Additionally, apoptotic T cells secrete TGF-β which acts as a growth factor for FoxP3−LAP+ Tregs [29, 92, 93] and CD4+CD25+ Tregs [94–97].

2.2.2. Role of Antigen presenting cells

Orally administered antigens can be acquired directly by M cells, macrophages, DCs and enterocytes [98], or can be delivered through goblet cell associated passages prior to capture by DCs in the lamina propria (LP), Peyer’s patches (PP) or MLN [99]. In the gut, DCs play a major role in antigen presentation and the state of DC differentiation or maturation can determine the outcome of the immune response. Several studies reported that antigen presentation to naïve T cells through immature, steady state CD103+ DCs without any co-stimulation leads to tolerance induction [67, 100–102]. Conversely, antigen presentation by activated DCs during inflammatory conditions results in the induction of strong Teff function and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines [103, 104].

CD103+ DCs in the LP and MLN express aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), which mediates retinoic acid (RA) production from dietary vitamin A [67, 105]. These cells can prime Tregs in the GALT through production of large amount of RA and TGF-β, promoting a tolerogenic environment in the intestine [67, 69]. RA produced by CD103+ DCs mediates the migration of pTregs generated in lymph nodes to the small intestine through upregulation of gut-homing receptors, CCR9 and α4β7 integrin [69, 106]. Additionally, CD103+ DCs express high levels of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), an enzyme required for tryptophan catabolism [107]. IDO mediated tryptophan catabolism reduces tryptophan availability, which inhibits Teff proliferation and can indirectly activate or de novo induce pTregs [108, 109].

MLN resident plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) in the MLN play important multifaceted roles leading to anergy or depletion of reactive Teffs. MLN pDCs also secrete IL-10, TGF-β, and inhibit type I IFN production to induce Treg differentiation [110, 111]. Other DC subsets, including XCR1+ and CD103− DC, also express enzymes required for RA formation [112], although further studies are required to better understand the role of these cells in oral tolerance.

2.3. Site of oral tolerance induction

The development of oral tolerance is thought to mainly take place in the small and large intestines of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GALT including the LP, intraepithelial lymphocytes, MLN, PP, and isolated lymphoid follicles play a key role in regulating responses to ingested antigens [113, 114]. The GALT is an incredibly complex and diverse immune network constituting around 70% of the immune system and involving a variety of cell types and tissue structures [36, 115]. It operates by a complex interplay of several factors, which primarily offers a tolerogenic environment to the gut while supporting an inflammatory response to eliminate ingested pathogens.

The immune system of the gut is separated from the intestinal lumen by a single layered epithelium. Orally administered antigens gain access to the intestinal immune system through a variety of mechanisms, including uptake by microfold (M) cells in the epithelial layer [116, 117] or directly by DCs extending through tight junctions [118] in the PP and LP. Antigen taken up by M cells is transported to professional APCs (mainly DCs) in the follicles, which migrate to gut draining MLN and stimulate antigen specific T cells [114]. The gut draining MLNs play an important role in orchestrating immune responses and are indispensable for oral tolerance induction [114], whereas less is known about the requirement of other GALT components such as the PP and LP [119, 120]. MLNs are anatomically and immunologically distinct, supporting different immune responses depending on the intestinal segment they drain [121, 122]. Houston et al. suggested that proximal MLNs are involved in tolerance induction against food antigens, whereas distal MLNs provide tolerance to gut microbiota [122]. Another study reported the involvement of proximal MLNs in tolerance induction to dietary antigens thus preventing food allergy, whereas distal MLNs generated inflammatory responses towards invading pathogens [121]. Importantly, both studies demonstrate that MLNs are the main site of oral tolerance induction.

Additionally, a fraction of orally administered antigen, either intact or digested in the form of polypeptides, is transferred via blood vessels in the LP and disseminated systemically to peripheral lymphoid organs or the liver [123–125]. pDCs in the liver, similar to the MLN, induce tolerance by promoting anergy and/or deletion of reactive T cells [126].

Taken together, oral tolerance induction involves a complex interplay between different immune cell types including DCs, Tregs, and Teffs, which work at multiple sites through interconnected mechanisms to prevent responses against orally administered antigens.

3. Application of oral tolerance in ADA development

Several preclinical studies have been performed to induce oral tolerance to therapeutic proteins or enzymes administered to patients with single gene disorders, such as hemophilia or Pompe disease. These studies mainly involve the use of 2 oral delivery strategies that provide an advantage over simple intake of naked antigen. The first strategy involves the generation of transplastomic tobacco or lettuce plants that express the therapeutic protein at high expression levels due to the large number of chloroplasts in a plant [127, 128]. Bioencapsulation within the cell wall of plant cells prevents degradation from harsh stomach enzymes after oral administration, until the proteins are acted upon by enzymes produced by specific commensals in the mammalian gut [129]. Second, conjugation of therapeutic protein with a carrier protein such as the cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) helps in achieving efficient transmucosal uptake and delivery to the immune or circulatory system once released from the plant cells in the intestinal lumen [130–132]. CTB conjugation sharply minimizes the amount of antigen required for orally induced tolerization, and also reduces the number of doses needed [133]. Other carrier proteins such as dendritic cell peptide (DCpep) or protein transduction domains (PTD) have been shown to facilitate transportation of the conjugated macromolecule into specific cell types such as mucosal DC, kidney or pancreatic cells [132]. On the other hand, CTB’s strong binding affinity for the ganglioside GM1, which is ubiquitously expressed on most mammalian cell types, improves uptake by immune modulatory cells such as macrophages, DC, T, B, or mast cells [132, 134, 135]. Oral delivery of naked CTB-fusion proteins (10–20μg/dose) have also been shown to induce tolerance in experimental animal models of experimental allergic encephalitis (EAE), diabetes, arthritis, uveitis, and in allergy [133, 136–138]. However, plant bioencapsulated protein have been shown to be effective at very low doses (0.15μg/dose) in mice [52], highlighting the advantage of bioencapsulation in protecting the antigen from degradation in the digestive system prior to crossing the gut epithelium for delivery to target cells.

3.1. Hemophilia A

Hemophilia A (HA) is an X-linked genetic disorder caused by mutations in the F8 gene resulting in insufficient production of coagulation factor VIII (FVIII). The standard treatment is intravenous (IV) administration of recombinant FVIII protein, which is complicated by formation of neutralizing anti-FVIII antibodies in more than 30% of patients with severe disease [139, 140]. Reversal of inhibitors by immune tolerance induction (ITI), which involves repeated and prolonged administration of high FVIII doses, is currently the only approved strategy to eradicate inhibitors [141–143]. However, the success rate of ITI is 45–80% depending on the protocol used and the overall cost of treatment is very high [15, 144, 145]. Currently, there are no successful prophylactic immune tolerance protocols, emphasizing the need for new and improved strategies to prevent inhibitor formation.

The laboratories of Dr. Roland Herzog and Dr. Henry Daniell generated transplastomic tobacco plant lines expressing the heavy chain (HC: A1, A2 domains) and C2 domains of B-domain deleted (BDD) FVIII fused to CTB, which forms a pentameric complex that effectively targets GM1 on epithelial cells of the small intestine for effective antigen uptake and transmucosal delivery to the gut immune system [51]. Oral administration of the HC/C2 mixture resulted in suppression of T helper cell responses and prevention of inhibitor formation in an HA mouse model [51]. Oral tolerance was mediated through enhanced secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β and induction of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ and CD4+CD25−FoxP3−LAP+ subsets of Tregs [51, 52]. The latter are most robustly induced in the gut immune system (PP and MLN) but are also detectable in the blood and spleen. Although expression of FVIII domains in tobacco chloroplast showed induction of oral tolerance, there are significant challenges in clinical development using the tobacco system, not least being expression of full length CTB-FVIII, which is required to encompass all known T cell epitopes to cover diverse patient populations. Kwon and co-authors used homoplasmic lettuce cell lines to express codon optimized FVIII protein, which resulted in high level expression of CTB fused FVIII HC, light chain (LC: A3, C1 and C2 domains), C2 domain and the entire BDD human FVIII protein (SC) in chloroplasts to levels required for clinical translation [52]. Repeated oral gavage using low doses of CTB-FVIII-HC/LC into HA mice resulted in ~10-fold decrease in both neutralizing and binding ADA titers, which was comparable to the tolerance observed with tobacco cells co-expressing CTB-FVIII-HC and C2 domains (8-fold) [51, 52].

Alternative approaches for oral tolerance induction to FVIII include standalone or combination therapy with oral anti-CD3 administration. In a recent study, Bertolini et al. demonstrated that oral anti-CD3 administration prevents ADA formation in HA mice [146]. They observed a significant decrease in FVIII ADA formation with oral uptake of low dose (0.5ug) anti-CD3 (Fab’ fragment), although there was no improvement if oral anti-CD3 was combined with FVIII lettuce. Their findings are further detailed in this special issue.

3.2. Hemophilia B

Hemophilia B (HB), caused by mutations in the gene coding for F9 occurs less frequently than hemophilia A (1 in 20000 male births) [147]. ADA following treatment with recombinant therapeutic FIX protein is also less frequent, but is often complicated by the development of life-threatening anaphylactic reactions and IgE-mediated allergy [148]. Initial studies performed with oral administration of CTB fused FIX bioencapsulated in plant cells demonstrated the prevention of ADA formation and elimination of anaphylaxis long-term (~7 months) in an HB mouse model [149]. Further studies to evaluate the underlying tolerance mechanisms revealed a complex, IL-10 dependent mechanism of antigen-specific systemic immune suppression that prevented pathogenic IgG1 and IgE antibodies [150]. Breakdown of plant cell wall components and tolerogenic antigen presentation in the small intestine depended on the bacterial microbiome, which was distinct from the bacterial species found in the large intestine and contributed to Treg induction [129]. The combination of oral and systemic FIX delivery caused a significant increase in pDCs in the spleen, MLNs, and PPs, as well as in CD103+ DCs in MLNs and PPs [129, 150]. Activated CD103+ DC migrated to draining lymph nodes where they induced Treg expansion and migration [129, 150]. CD4+CD25−LAP+ cells were significantly increased in the spleen and even more robustly in PP and MLNs, which was particularly evident in the small intestine [129, 150]. CD4+CD25−LAP+ Tregs were the main source of increased IL-10 and TGF-β expression in FIX-fed/systemically treated mice [129, 150]. In addition, there was an increase in LAP+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in PP, indicating activation of FoxP3+ Tregs. Secondary transfer studies from splenocytes of tolerized mice demonstrated that suppression of antibody formation was achieved by both FoxP3+ and LAP+ Treg [129, 150].

Taking into consideration the success of oral tolerance induction in mouse models using the plant-based approach, efforts have been made to scale up production and enable commercialization of this production process. Efficient expression of CTB-FIX in a commercial lettuce cultivar using a cGMP hydroponic system showed stability of lyophilized lettuce at ambient temperatures for years, excision of the antibiotic selection marker, and induction of oral tolerance using a broad dose range, addressing remaining issues regarding cost of production, purification and cold chain/transportation requirements [54, 151]. Toxicology studies for the commercially produced CTB-FIX expressing lettuce cells in hemostatically normal male rats and dogs did not produce any adverse effects [151]. Further assessment in HB dogs fed with lyophilized lettuce cells expressing CTB-FIX demonstrated robust suppression of IgG/IgE formation to IV FIX administration with markedly shortened coagulation times in 3 out of 4 dogs. No side effects were detected after feeding CTB-FIX-lyophilized plant cells for >300 days, reinforcing the feasibility of this approach [53].

3.3. Pompe disease

Pompe disease is a fatal autosomal recessive disorder caused by a deficiency of the enzyme acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA), leading to intra-lysosomal glycogen accumulation in multiple tissue types, particularly cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle [152–154]. Disease severity is determined by residual GAA activity. Intravenous enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with recombinant human (rh)GAA has improved clinical outcomes and prolonged survival in patients [155]. However, formation of high-sustained rhGAA IgG antibody titers (HSAT) to the therapeutic protein in a substantial subset of CRIM negative patients results in neutralization of ERT efficacy, leading to decline in muscle strength, pulmonary function, and contributing significantly to early mortality [11, 156]. Additionally, IgE responses to ERT are implicated in infusion-associated reactions and anaphylaxis [157]. It can generally be agreed that prophylactic therapeutic approaches delivered as a combinatorial regimen co-initiated alongside ERT rather than single agent therapies are probably the most effective strategy for prevention of HSATs [158–160]. However, there are reservations about administering highly intensive immunosuppressive drugs to very young patients with Pompe disease. Alternative antigen specific tolerance approaches such as oral therapy present novel adjunctive therapies that can be administered in very young patients.

Initial prophylactic studies performed by Ohashi and group in mice demonstrated that that oral administration of high dose rhGAA at increased frequencies (5X/day, every other day) prior to intraperitoneal injection resulted in significantly reduced IgG and IgE antibody titers, indicating suppression of both cellular and humoral immune responses [161]. The disadvantage with this approach is the large antigen dose required, and the intensive oral therapy schedule. To overcome these limitations, Su and co-authors demonstrated the use of CTB fused hGAA protein that could enhance mucosal antigen uptake and presentation in the GALT [46]. The authors bioencapsulated a truncated N-terminal 410 amino acid portion of hGAA fused to CTB in homoplasmic transplastomic tobacco cells. The truncated GAA product included relevant CD4+ T cell epitopes, which play a role in B-cell activation and the formation of antibodies to ERT in Pompe disease [162]. Oral administration of the CTB-hGAA lyophilized plant cells suppressed GAA-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibody formation at greater than 10,666-fold lower dose (tobacco leaves containing approximately 0.06mg/kg or 1.5 ug CTB-GAA per mouse) compared to feeding with nonencapsulated rhGAA without CTB fusion (0.64g/kg or 16 mg per mouse) due to improved CTB mediated uptake by the mucosal lining [46, 161]. Furthermore, intravenous administration of rhGAA to orally tolerized mice showed significantly lower anti-rhGAA antibody formation, demonstrating the long-term maintenance of tolerance [46].

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that plant based oral tolerance approach is a cost effective and safe option to manage immune responses against therapeutic proteins.

4. Limitations:

The above-mentioned studies show promise for oral therapy in preventing the generation of immune responses against therapeutic proteins. Optimizing the dosing amount and frequency to achieve tolerance are still required. There is also the issue of cost, although plant-based oral tolerance approaches require significantly lower doses of antigen. There are also questions such as whether prolonged feeding is required to achieve long-term tolerance and what happens when oral therapy is stopped. While the PALISADE [NCT02635776] and ARTEMIS [NCT03201003] oral immunotherapy trials for peanut allergy demonstrated desensitization of patients to the peanut allergen [56, 163], longer term safety and efficacy data, as well as the need for continuous immunotherapy is not well understood [164], with follow-up studies demonstrating a potential benefit with continued daily PTAH treatment beyond 1 year [164]. Therefore, it appears that with food allergy, stopping oral therapy would result in a loss of desensitization, although it is not known if the same is true for oral tolerance to ADAs.

Furthermore, oral tolerance induction works efficiently in a naïve environment, but is more difficult to achieve under established immune response conditions. Reversal studies performed in hemophilia A and B mouse models demonstrated that plant-based oral administration of antigen accelerated the decline in ADAs, even though complete eradication was not achieved [51, 52, 150]. Therefore, these findings demonstrate a utility for oral tolerance in ADA reversal by incorporation into future ITI protocols by lowering the duration of ADA decline and allowing patients to resume factor replacement therapy sooner.

In conclusion, oral tolerance is a non-invasive and antigen-specific approach which utilizes natural immune regulatory pathways to prevent or reverse ADAs against therapeutic proteins. Recent advances in the field of plant biotechnology have improved expression levels of the therapeutic proteins in edible plant sources such as lettuce [151]. Majority of these studies have been performed in mice, except for a single canine study for hemophilia B [53]. More detailed studies in larger animal models will shed light on the efficacy of the treatment in humans. In the past decade, there has been an increase in knowledge of oral tolerance mechanisms and the cell types involved, even though the underlying mechanisms have not been fully elucidated. Critical questions remain on optimal antigen dose selection, administration schedule, and responsiveness to the treatment. These will aid in identifying new targets for treatment and development of new treatment protocols that are safer, more effective, and durable.

Highlights:

Anti-drug antibodies (ADA) complicate protein replacement therapy for monogenic disorders

Antigen based oral tolerance induction can prevent the formation of ADAs.

Oral tolerance to antigen depends on the induction of regulatory T cells.

Plant-based antigen expression for oral tolerance has been tested in hemophilia and Pompe models.

Acknowledgements

J.R. is funded in part by a Bayer Hemophilia Basic Research award. M.B. has received support from R01HL 133191. Figure is created using Biorender.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Krishna M and Nadler SG, Immunogenicity to Biotherapeutics - The Role of Anti-drug Immune Complexes. Front Immunol, 2016. 7: p. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dingman R and Balu-Iyer SV, Immunogenicity of Protein Pharmaceuticals. J Pharm Sci, 2019. 108(5): p. 1637–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermeling S, et al. , Structure-immunogenicity relationships of therapeutic proteins. Pharm Res, 2004. 21(6): p. 897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chirmule N, Jawa V, and Meibohm B, Immunogenicity to therapeutic proteins: impact on PK/PD and efficacy. AAPS J, 2012. 14(2): p. 296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg AS, Immunogenicity of biological therapeutics: a hierarchy of concerns. Dev Biol (Basel), 2003. 112: p. 15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sathish JG, et al. , Challenges and approaches for the development of safer immunomodulatory biologics. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2013. 12(4): p. 306–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schellekens H, The immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins. Discov Med, 2010. 9(49): p. 560–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Groot AS and Scott DW, Immunogenicity of protein therapeutics. Trends Immunol, 2007. 28(11): p. 482–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansel TT, et al. , The safety and side effects of monoclonal antibodies. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2010. 9(4): p. 325–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehncke WH and Brembilla NC, Immunogenicity of biologic therapies: causes and consequences. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2018. 14(6): p. 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kishnani PS, et al. , Cross-reactive immunologic material status affects treatment outcomes in Pompe disease infants. Mol Genet Metab, 2010. 99(1): p. 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenders M and Brand E, Effects of Enzyme Replacement Therapy and Antidrug Antibodies in Patients with Fabry Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2018. 29(9): p. 2265–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou ZY, et al. , Burden of illness: direct and indirect costs among persons with hemophilia A in the United States. J Med Econ, 2015. 18(6): p. 457–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendelsohn NJ, et al. , Elimination of antibodies to recombinant enzyme in Pompe’s disease. N Engl J Med, 2009. 360(2): p. 194–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hay CR, DiMichele DM, and S. International Immune Tolerance, The principal results of the International Immune Tolerance Study: a randomized dose comparison. Blood, 2012. 119(6): p. 1335–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banugaria SG, et al. , Bortezomib in the rapid reduction of high sustained antibody titers in disorders treated with therapeutic protein: lessons learned from Pompe disease. Genet Med, 2013. 15(2): p. 123–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biss TT, Velangi MR, and Hanley JP, Failure of rituximab to induce immune tolerance in a boy with severe haemophilia A and an alloimmune factor VIII antibody: a case report and review of the literature. Haemophilia, 2006. 12(3): p. 280–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carcao M, et al. , Rituximab for congenital haemophiliacs with inhibitors: a Canadian experience. Haemophilia, 2006. 12(1): p. 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garman RD, Munroe K, and Richards SM, Methotrexate reduces antibody responses to recombinant human alpha-galactosidase A therapy in a mouse model of Fabry disease. Clin Exp Immunol, 2004. 137(3): p. 496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joly MS, et al. , Transient low-dose methotrexate generates B regulatory cells that mediate antigen-specific tolerance to alglucosidase alfa. J Immunol, 2014. 193(8): p. 3947–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markic J, et al. , Immune Modulation Therapy in a CRIM-Positive and IgG Antibody-Positive Infant with Pompe Disease Treated with Alglucosidase Alfa: A Case Report. JIMD Rep, 2012. 2: p. 11–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ratnasingam S, et al. , Bortezomib-based antibody depletion for refractory autoimmune hematological diseases. Blood Adv, 2016. 1(1): p. 31–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reipert BM, et al. , Blockade of CD40/CD40 ligand interactions prevents induction of factor VIII inhibitors in hemophilic mice but does not induce lasting immune tolerance. Thromb Haemost, 2001. 86(6): p. 1345–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato Y, Ida H, and Ohashi T, Anti-BlyS antibody reduces the immune reaction against enzyme and enhances the efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease model mice. Clin Immunol, 2017. 178: p. 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biswas M, et al. , Combination therapy for inhibitor reversal in haemophilia A using monoclonal anti-CD20 and rapamycin. Thromb Haemost, 2017. 117(1): p. 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doshi BS, Raffini LJ, and George LA, Combined anti-CD20 and mTOR inhibition with factor VIII for immune tolerance induction in hemophilia A patients with refractory inhibitors. J Thromb Haemost, 2020. 18(4): p. 848–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batsuli G, et al. , High-affinity, noninhibitory pathogenic C1 domain antibodies are present in patients with hemophilia A and inhibitors. Blood, 2016. 128(16): p. 2055–2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Terhorst C, and Herzog RW, In vivo induction of regulatory T cells for immune tolerance in hemophilia. Cell Immunol, 2016. 301: p. 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faria AM and Weiner HL, Oral tolerance. Immunol Rev, 2005. 206: p. 232–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins PJ and Weiner HL, Suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by oral administration of myelin basic protein and its fragments. J Immunol, 1988. 140(2): p. 440–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bitar DM and Whitacre CC, Suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by the oral administration of myelin basic protein. Cell Immunol, 1988. 112(2): p. 364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagler-Anderson C, et al. , Suppression of type II collagen-induced arthritis by intragastric administration of soluble type II collagen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1986. 83(19): p. 7443–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maron R, et al. , Oral administration of insulin to neonates suppresses spontaneous and cyclophosphamide induced diabetes in the NOD mouse. J Autoimmun, 2001. 16(1): p. 21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilan Y, et al. , Treatment of experimental colitis by oral tolerance induction: a central role for suppressor lymphocytes. Am J Gastroenterol, 2000. 95(4): p. 966–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lonnqvist A, et al. , Neonatal exposure to staphylococcal superantigen improves induction of oral tolerance in a mouse model of airway allergy. Eur J Immunol, 2009. 39(2): p. 447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiner HL, et al. , Oral tolerance. Immunol Rev, 2011. 241(1): p. 241–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Besredka A, De l’anaphylaxie. Sixi me memoire de l’anaphykaxie lactique. Ann Inst Pasteur, 1909. 33: p. 166–74. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells HG and Osborne TB, The Biological Reactions of the Vegetable Proteins I. Anaphylaxis. 1911, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 8, Issue 1, 3 January 1911, Pages 66–124. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson HS and Staines NA, Gastric administration of type II collagen delays the onset and severity of collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Clin Exp Immunol, 1986. 64(3): p. 581–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vickery BP, et al. , Early oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic preschool children is safe and highly effective. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2017. 139(1): p. 173–181 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bird JA, et al. , Efficacy and Safety of AR101 in Oral Immunotherapy for Peanut Allergy: Results of ARC001, a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Clinical Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2018. 6(2): p. 476–485 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki K, et al. , Prevention of allergic asthma by vaccination with transgenic rice seed expressing mite allergen: induction of allergen-specific oral tolerance without bystander suppression. Plant Biotechnol J, 2011. 9(9): p. 982–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee CC, et al. , Construction of a Der p2-transgenic plant for the alleviation of airway inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol, 2011. 8(5): p. 404–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakasa Y, et al. , Oral immunotherapy with transgenic rice seed containing destructed Japanese cedar pollen allergens, Cry j 1 and Cry j 2, against Japanese cedar pollinosis. Plant Biotechnol J, 2013. 11(1): p. 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lalazar G, et al. , Oral Administration of OKT3 MAb to Patients with NASH, Promotes Regulatory T-cell Induction, and Alleviates Insulin Resistance: Results of a Phase IIa Blinded Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Clin Immunol, 2015. 35(4): p. 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su J, et al. , Oral delivery of Acid Alpha Glucosidase epitopes expressed in plant chloroplasts suppresses antibody formation in treatment of Pompe mice. Plant Biotechnol J, 2015. 13(8): p. 1023–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iizuka M, et al. , Suppression of collagen-induced arthritis by oral administration of transgenic rice seeds expressing altered peptide ligands of type II collagen. Plant Biotechnol J, 2014. 12(8): p. 1143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansson C, et al. , Feeding transgenic plants that express a tolerogenic fusion protein effectively protects against arthritis. Plant Biotechnol J, 2016. 14(4): p. 1106–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y, et al. , Targeted delivery of antigen to intestinal dendritic cells induces oral tolerance and prevents autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetologia, 2018. 61(6): p. 1384–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Posgai AL, et al. , Plant-based vaccines for oral delivery of type 1 diabetes-related autoantigens: Evaluating oral tolerance mechanisms and disease prevention in NOD mice. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: p. 42372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sherman A, et al. , Suppression of inhibitor formation against FVIII in a murine model of hemophilia A by oral delivery of antigens bioencapsulated in plant cells. Blood, 2014. 124(10): p. 1659–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwon KC, et al. , Expression and assembly of largest foreign protein in chloroplasts: oral delivery of human FVIII made in lettuce chloroplasts robustly suppresses inhibitor formation in haemophilia A mice. Plant Biotechnol J, 2018. 16(6): p. 1148–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herzog RW, et al. , Oral Tolerance Induction in Hemophilia B Dogs Fed with Transplastomic Lettuce. Mol Ther, 2017. 25(2): p. 512–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su J, et al. , Low cost industrial production of coagulation factor IX bioencapsulated in lettuce cells for oral tolerance induction in hemophilia B. Biomaterials, 2015. 70: p. 84–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tilles SA and Petroni D, FDA-approved peanut allergy treatment: The first wave is about to crest. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 2018. 121(2): p. 145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Investigators P.G.o.C., et al. , AR101 Oral Immunotherapy for Peanut Allergy. N Engl J Med, 2018. 379(21): p. 1991–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Y, et al. , Regulatory T cell clones induced by oral tolerance: suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science, 1994. 265(5176): p. 1237–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friedman A and Weiner HL, Induction of anergy or active suppression following oral tolerance is determined by antigen dosage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1994. 91(14): p. 6688–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitacre CC, et al. , Oral tolerance in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. III. Evidence for clonal anergy. J Immunol, 1991. 147(7): p. 2155–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen Y, et al. , Peripheral deletion of antigen-reactive T cells in oral tolerance. Nature, 1995. 376(6536): p. 177–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Itoh M, et al. , Thymus and autoimmunity: production of CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells as a key function of the thymus in maintaining immunologic self-tolerance. J Immunol, 1999. 162(9): p. 5317–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Furtado GC, et al. , Interleukin 2 signaling is required for CD4(+) regulatory T cell function. J Exp Med, 2002. 196(6): p. 851–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomann AS, et al. , Conversion of Anergic T Cells Into Foxp3(−) IL-10(+) Regulatory T Cells by a Second Antigen Stimulus In Vivo. Front Immunol, 2021. 12: p. 704578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pabst O and Bernhardt G, On the road to tolerance--generation and migration of gut regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol, 2013. 43(6): p. 1422–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mucida D, et al. , Oral tolerance in the absence of naturally occurring Tregs. J Clin Invest, 2005. 115(7): p. 1923–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Josefowicz SZ, et al. , Extrathymically generated regulatory T cells control mucosal TH2 inflammation. Nature, 2012. 482(7385): p. 395–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coombes JL, et al. , A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med, 2007. 204(8): p. 1757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hadis U, et al. , Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria. Immunity, 2011. 34(2): p. 237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun CM, et al. , Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med, 2007. 204(8): p. 1775–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duan W, et al. , Inducible CD4+LAP+Foxp3- regulatory T cells suppress allergic inflammation. J Immunol, 2011. 187(12): p. 6499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ochi H, et al. , Oral CD3-specific antibody suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing CD4+ CD25− LAP+ T cells. Nat Med, 2006. 12(6): p. 627–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Forster K, et al. , An oral CD3-specific antibody suppresses T-cell-induced colitis and alters cytokine responses to T-cell activation in mice. Gastroenterology, 2012. 143(5): p. 1298–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de la Rosa M, et al. , Interleukin-2 is essential for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell function. Eur J Immunol, 2004. 34(9): p. 2480–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deaglio S, et al. , Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med, 2007. 204(6): p. 1257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pandiyan P, et al. , CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol, 2007. 8(12): p. 1353–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Belghith M, et al. , TGF-beta-dependent mechanisms mediate restoration of self-tolerance induced by antibodies to CD3 in overt autoimmune diabetes. Nat Med, 2003. 9(9): p. 1202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chaudhry A, et al. , CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science, 2009. 326(5955): p. 986–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huber S, et al. , Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3(−) and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity, 2011. 34(4): p. 554–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fallarino F, et al. , Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol, 2003. 4(12): p. 1206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wing K, et al. , CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science, 2008. 322(5899): p. 271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liang B, et al. , Regulatory T cells inhibit dendritic cells by lymphocyte activation gene-3 engagement of MHC class II. J Immunol, 2008. 180(9): p. 5916–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rellahan BL, et al. , In vivo induction of anergy in peripheral V beta 8+ T cells by staphylococcal enterotoxin B. J Exp Med, 1990. 172(4): p. 1091–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mueller DL, et al. , Clonal anergy blocks the response to IL-4, as well as the production of IL-2, in dual-producing T helper cell clones. J Immunol, 1991. 147(12): p. 4118–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chiodetti L and Schwartz RH, Induction of competence to respond to IL-4 by CD4+ T helper type 1 cells requires costimulation. J Immunol, 1992. 149(3): p. 901–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gorelik M, et al. , Suppression of the immunologic response to peanut during immunotherapy is often transient. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2015. 135(5): p. 1283–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Varshney P, et al. , A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2011. 127(3): p. 654–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perezabad L, et al. , Oral Food Desensitization in Children With IgE-Mediated Cow’s Milk Allergy: Immunological Changes Underlying Desensitization. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res, 2017. 9(1): p. 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ryan JF, et al. , Successful Immunotherapy Induces Previously Unidentified Allergen-Specific CD4+ T-cell Subsets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2016. 113(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grossman WJ, et al. , Human T regulatory cells can use the perforin pathway to cause autologous target cell death. Immunity, 2004. 21(4): p. 589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gondek DC, et al. , Cutting edge: contact-mediated suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells involves a granzyme B-dependent, perforin-independent mechanism. J Immunol, 2005. 174(4): p. 1783–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Watanabe T, et al. , Administration of an antigen at a high dose generates regulatory CD4+ T cells expressing CD95 ligand and secreting IL-4 in the liver. J Immunol, 2002. 168(5): p. 2188–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Paul WE and Seder RA, Lymphocyte responses and cytokines. Cell, 1994. 76(2): p. 241–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Weiner HL, The mucosal milieu creates tolerogenic dendritic cells and T(R)1 and T(H)3 regulatory cells. Nat Immunol, 2001. 2(8): p. 671–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen W, et al. , TGF-beta released by apoptotic T cells contributes to an immunosuppressive milieu. Immunity, 2001. 14(6): p. 715–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen W, et al. , Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med, 2003. 198(12): p. 1875–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Horwitz DA, Zheng SG, and Gray JD, The role of the combination of IL-2 and TGF-beta or IL-10 in the generation and function of CD4+ CD25+ and CD8+ regulatory T cell subsets. J Leukoc Biol, 2003. 74(4): p. 471–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kleinclauss F, et al. , Intravenous apoptotic spleen cell infusion induces a TGF-beta-dependent regulatory T-cell expansion. Cell Death Differ, 2006. 13(1): p. 41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Peron JP, de Oliveira AP, and Rizzo LV, It takes guts for tolerance: the phenomenon of oral tolerance and the regulation of autoimmune response. Autoimmun Rev, 2009. 9(1): p. 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kulkarni DH, et al. , Goblet cell associated antigen passages support the induction and maintenance of oral tolerance. Mucosal immunology, 2020. 13(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hawiger D, et al. , Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J Exp Med, 2001. 194(6): p. 769–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Matteoli G, et al. , Gut CD103+ dendritic cells express indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase which influences T regulatory/T effector cell balance and oral tolerance induction. Gut, 2010. 59(5): p. 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bonifaz L, et al. , Efficient targeting of protein antigen to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205 in the steady state leads to antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class I products and peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance. J Exp Med, 2002. 196(12): p. 1627–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Banchereau J, Pascual V, and Palucka AK, Autoimmunity through cytokine-induced dendritic cell activation. Immunity, 2004. 20(5): p. 539–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bonifaz LC, et al. , In vivo targeting of antigens to maturing dendritic cells via the DEC-205 receptor improves T cell vaccination. J Exp Med, 2004. 199(6): p. 815–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mucida D, et al. , Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science, 2007. 317(5835): p. 256–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kang SG, et al. , Vitamin A Metabolites Induce Gut-Homing FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells. The Journal of Immunology, 2007. 179(6): p. 3724–3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Munn DH and Mellor AL, Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. J Clin Invest, 2007. 117(5): p. 1147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sharma MD, et al. , Plasmacytoid dendritic cells from mouse tumor-draining lymph nodes directly activate mature Tregs via indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Clin Invest, 2007. 117(9): p. 2570–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fallarino F, et al. , The combined effects of tryptophan starvation and tryptophan catabolites down-regulate T cell receptor zeta-chain and induce a regulatory phenotype in naive T cells. J Immunol, 2006. 176(11): p. 6752–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li HS, et al. , Cell-intrinsic role for IFN-alpha-STAT1 signals in regulating murine Peyer patch plasmacytoid dendritic cells and conditioning an inflammatory response. Blood, 2011. 118(14): p. 3879–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Contractor N, et al. , Cutting edge: Peyer’s patch plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce low levels of type I interferons: possible role for IL-10, TGFbeta, and prostaglandin E2 in conditioning a unique mucosal pDC phenotype. J Immunol, 2007. 179(5): p. 2690–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stagg AJ, Intestinal Dendritic Cells in Health and Gut Inflammation. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Satitsuksanoa P, et al. , Regulatory Immune Mechanisms in Tolerance to Food Allergy. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Worbs T, et al. , Oral tolerance originates in the intestinal immune system and relies on antigen carriage by dendritic cells. J Exp Med, 2006. 203(3): p. 519–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mestecky J and McGhee JR, Immunoglobulin A (IgA): molecular and cellular interactions involved in IgA biosynthesis and immune response. Adv Immunol, 1987. 40: p. 153–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wheeler EE, et al. , A morphological study of beta-lactoglobulin absorption by cultured explants of the human duodenal mucosa using immunocytochemical and cytochemical techniques. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 1993. 16(2): p. 157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Heyman M, et al. , Antigen absorption by the jejunal epithelium of children with cow’s milk allergy. Pediatr Res, 1988. 24(2): p. 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chirdo FG, et al. , Immunomodulatory dendritic cells in intestinal lamina propria. Eur J Immunol, 2005. 35(6): p. 1831–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Atarashi K, et al. , Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science, 2011. 331(6015): p. 337–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Spahn TW, et al. , Mesenteric lymph nodes are critical for the induction of high-dose oral tolerance in the absence of Peyer’s patches. Eur J Immunol, 2002. 32(4): p. 1109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Esterhazy D, et al. , Compartmentalized gut lymph node drainage dictates adaptive immune responses. Nature, 2019. 569(7754): p. 126–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Houston SA, et al. , The lymph nodes draining the small intestine and colon are anatomically separate and immunologically distinct. Mucosal Immunol, 2016. 9(2): p. 468–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gutgemann I, et al. , Induction of rapid T cell activation and tolerance by systemic presentation of an orally administered antigen. Immunity, 1998. 8(6): p. 667–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Li W, et al. , Role of the liver in peripheral tolerance: induction through oral antigen feeding. Am J Transplant, 2004. 4(10): p. 1574–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Swarbrick ET, Stokes CR, and Soothill JF, Absorption of antigens after oral immunisation and the simultaneous induction of specific systemic tolerance. Gut, 1979. 20(2): p. 121–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Goubier A, et al. , Plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate oral tolerance. Immunity, 2008. 29(3): p. 464–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Verma D, et al. , A protocol for expression of foreign genes in chloroplasts. Nat Protoc, 2008. 3(4): p. 739–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Daniell H, et al. , Green giant-a tiny chloroplast genome with mighty power to produce high-value proteins: history and phylogeny. Plant Biotechnol J, 2021. 19(3): p. 430–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kumar SRP, et al. , Role of Small Intestine and Gut Microbiome in Plant-Based Oral Tolerance for Hemophilia. Front Immunol, 2020. 11: p. 844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Daniell H, Kulis M, and Herzog RW, Plant cell-made protein antigens for induction of Oral tolerance. Biotechnol Adv, 2019. 37(7): p. 107413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kwon KC and Daniell H, Oral Delivery of Protein Drugs Bioencapsulated in Plant Cells. Mol Ther, 2016. 24(8): p. 1342–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Xiao Y, et al. , Low cost delivery of proteins bioencapsulated in plant cells to human non-immune or immune modulatory cells. Biomaterials, 2016. 80: p. 68–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sun JB, Czerkinsky C, and Holmgren J, Mucosally induced immunological tolerance, regulatory T cells and the adjuvant effect by cholera toxin B subunit. Scand J Immunol, 2010. 71(1): p. 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Daniell H, et al. , Expression of the native cholera toxin B subunit gene and assembly as functional oligomers in transgenic tobacco chloroplasts. J Mol Biol, 2001. 311(5): p. 1001–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sanchez J and Holmgren J, Cholera toxin - a foe & a friend. Indian J Med Res, 2011. 133: p. 153–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Rask C, et al. , Prolonged oral treatment with low doses of allergen conjugated to cholera toxin B subunit suppresses immunoglobulin E antibody responses in sensitized mice. Clin Exp Allergy, 2000. 30(7): p. 1024–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bergerot I, et al. , A cholera toxoid-insulin conjugate as an oral vaccine against spontaneous autoimmune diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1997. 94(9): p. 4610–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tarkowski A, et al. , Treatment of experimental autoimmune arthritis by nasal administration of a type II collagen-cholera toxoid conjugate vaccine. Arthritis Rheum, 1999. 42(8): p. 1628–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Berntorp E and Shapiro AD, Modern haemophilia care. Lancet, 2012. 379(9824): p. 1447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Scott DW, Pratt KP, and Miao CH, Progress toward inducing immunologic tolerance to factor VIII. Blood, 2013. 121(22): p. 4449–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Morfini M, et al. , European study on orthopaedic status of haemophilia patients with inhibitors. Haemophilia, 2007. 13(5): p. 606–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Matzinger P, Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol, 1994. 12: p. 991–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Hay CR, et al. , The diagnosis and management of factor VIII and IX inhibitors: a guideline from the UK Haemophilia Centre Doctors’ Organization (UKHCDO). Br J Haematol, 2000. 111(1): p. 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mariani G, Kroner B, and G. Immune Tolerance Study, Immune tolerance in hemophilia with factor VIII inhibitors: predictors of success. Haematologica, 2001. 86(11): p. 1186–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Meeks SL, et al. , Late immune tolerance induction in haemophilia A patients. Haemophilia, 2013. 19(3): p. 445–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Bertolini TBB, Kaczmarek M, Daniell R, Herzog H, R. W., Alternative Approaches to Oral Tolerance Induction to Factor FVIII. Blood, 2020. 136. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Iorio A, et al. , Establishing the Prevalence and Prevalence at Birth of Hemophilia in Males: A Meta-analytic Approach Using National Registries. Ann Intern Med, 2019. 171(8): p. 540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.DiMichele DM, Immune tolerance in haemophilia: the long journey to the fork in the road. Br J Haematol, 2012. 159(2): p. 123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Verma D, et al. , Oral delivery of bioencapsulated coagulation factor IX prevents inhibitor formation and fatal anaphylaxis in hemophilia B mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(15): p. 7101–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Wang X, et al. , Plant-based oral tolerance to hemophilia therapy employs a complex immune regulatory response including LAP+CD4+ T cells. Blood, 2015. 125(15): p. 2418–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Srinivasan A, et al. , Preclinical development of plant-based oral immune modulatory therapy for haemophilia B. Plant Biotechnol J, 2021. 19(10): p. 1952–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.DeRuisseau LR, et al. , Neural deficits contribute to respiratory insufficiency in Pompe disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(23): p. 9419–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Falk DJ, et al. , Peripheral nerve and neuromuscular junction pathology in Pompe disease. Hum Mol Genet, 2015. 24(3): p. 625–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Tripathi SP, Phadke MS, and Kerkar PG, Giant Heart of Classical Infantile-Onset Pompe Disease With Mirror Image Dextrocardia. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging, 2015. 8(9): p. e003637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kishnani PS, et al. , Recombinant human acid [alpha]-glucosidase: major clinical benefits in infantile-onset Pompe disease. Neurology, 2007. 68(2): p. 99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Banugaria SG, et al. , The impact of antibodies on clinical outcomes in diseases treated with therapeutic protein: lessons learned from infantile Pompe disease. Genet Med, 2011. 13(8): p. 729–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Capanoglu M, et al. , IgE-Mediated Hypersensitivity and Desensitisation with Recombinant Enzymes in Pompe Disease and Type I and Type VI Mucopolysaccharidosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol, 2016. 169(3): p. 198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Kazi ZB, et al. , Sustained immune tolerance induction in enzyme replacement therapy-treated CRIM-negative patients with infantile Pompe disease. JCI Insight, 2017. 2(16). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Desai AK, et al. , Benefits of Prophylactic Short-Course Immune Tolerance Induction in Patients With Infantile Pompe Disease: Demonstration of Long-Term Safety and Efficacy in an Expanded Cohort. Front Immunol, 2020. 11: p. 1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Curelaru S, et al. , A favorable outcome in an infantile-onset Pompe patient with cross reactive immunological material (CRIM) negative disease with high dose enzyme replacement therapy and adjusted immunomodulation. Mol Genet Metab Rep, 2022. 32: p. 100893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Ohashi T, et al. , Oral administration of recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase reduces specific antibody formation against enzyme in mouse. Mol Genet Metab, 2011. 103(1): p. 98–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Nayak S, et al. , Mapping the T helper cell response to acid alpha-glucosidase in Pompe mice. Mol Genet Metab, 2012. 106(2): p. 189–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.J OBH, et al. , Efficacy and safety of oral immunotherapy with AR101 in European children with a peanut allergy (ARTEMIS): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2020. 4(10): p. 728–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Vickery BP, et al. , Continuous and Daily Oral Immunotherapy for Peanut Allergy: Results from a 2-Year Open-Label Follow-On Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2021. 9(5): p. 1879–1889 e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]