Abstract

Background:

The objective of this study was to determine the differential mapping of plasma biomarkers to postmortem neuropathology measures.

Methods:

We identified 64 participants in a population-based study with antemortem plasma markers (amyloid-β [Aβ] x-42, Aβx-40, neurofilament light [NfL], and total tau [T-tau]) who also had neuropathologic assessments of Alzheimer’s and cerebrovascular pathology. We conducted weighted linear-regression models to evaluate relationships between plasma measures and neuropathology.

Results:

Higher plasma NfL and Aβ42/40 ratio were associated with cerebrovascular neuropathologic scales (p<0.05) but not with Braak stage, neuritic plaque score, or Thal phase. Plasma Aβ42/40 and NfL explained up to 18% of the variability in cerebrovascular neuropathologic scales.

Discussion:

In participants predominantly with modest levels of Alzheimer’s pathologic change, biomarkers of amyloid and neurodegeneration were associated with cerebrovascular neuropathology. NfL is a non-specific marker of brain injury, therefore its association with cerebrovascular neuropathology was expected. The association between elevated Aβ42/40 and cerebrovascular disease pathology needs further investigation but could be due to the use of less specific amyloid-β assays (x-40, x-42).

Keywords: plasma biomarkers, neurofilament light (NfL), total tau (T-tau), cerebrovascular neuropathology, neurodegenerative biomarkers, postmortem neuropathology

INTRODUCTION

Plasma biomarkers offer advantages over cerebrospinal fluid and neuroimaging biomarkers with regards to cost, invasiveness, and feasibility. While some plasma biomarkers, such as the amyloid-β (Aβ) 42/40 ratio, are generally regarded to be specific for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathologic change and were shown to map onto AD pathology in vivo, neurodegenerative biomarkers are elevated in multiple neurodegenerative disorders; however, some neurodegenerative biomarkers may differentially map onto more than one neuropathologic feature. Plasma neurofilament light (NfL) is a biomarker of neuronal injury (Norgren et. al., 2003) shown to be elevated in AD (Mattsson et. al., 2017), frontotemporal dementia,(Illán-Gala et. al., 2021), and cerebrovascular disease (CVD) (Gendron et. al., 2020). Similarly, total-tau (T-tau) is elevated in AD (Mattsson et. al., 2016), Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and in brain injuries including stroke (De Vos et. al., 2017).

Although studies have examined these plasma measures in relation to neuroimaging or CSF, few studies have evaluated their neuropathologic correlates in a community sample. The objective of this study was to evaluate plasma amyloid and neurodegenerative biomarkers with postmortem neuropathologic measurements to determine the correlates of these biomarkers. We analyzed antemortem concentrations of plasma Aβ42/40, NfL and total-tau and measured the associations with Thal phase, neuritic plaque score, Braak stage, and cerebrovascular burden.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) is a population-based, prospective study of residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota. MCSA participants, aged 70 to 89, were ascertained from the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system in 2004, and recruitment was extended in 2012 to residents aged 50 and older (Roberts et. al., 2008). MCSA visits include an interview by a study coordinator, physician examination, cognitive testing, and a blood draw completed on the same day. The inclusion criteria for this study were MCSA participants who had undergone autopsy with available antemortem plasma markers within 5 years of death.

Clinical diagnoses were determined by a consensus committee comprised of a physician, study coordinator, and neuropsychologist using existing criteria for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Petersen, 2004) or dementia (American Psychiatric Association and Association, 2013).

Plasma assays

Details of the plasma collection, as well as Aβ40, Aβ42, T-tau, and NfL measurements have been previously published (Marks et. al., 2021, Michelle M. Mielke et. al., 2017, M. M. Mielke et. al., 2019). Blood was collected at a clinic visit after an overnight fast, centrifuged, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C (Kern et. al., 2019). Samples were run-in singlet. Eight-point calibration curves and sample measurements were determined on the Simoa HD-1 Analyzer software using a weighting factor 1/Y2 and a four-parameter logistic curve-fitting algorithm. Two levels of quality control material were included, flanking the samples at the front and end of each batch. Plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, T-tau, and NfL were measured on the Quanterix HD-1 analyzer using the Simoa Neurology 3-Plex A (N3PA) (tau, Aβ42, Aβ40) or Simoa NF-light. Plasma Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 were quantified using a common detection antibody (6E10), which binds to the amyloid-β peptide at an RHD sequence at residues 5 to 7. Unique C-terminal antibodies were used for Aβ40 (2G3) and Aβ42 (H31L21) (De Meyer et. al., 2020). Plasma T-tau was quantified using a capture antibody that binds to the proline-rich P2 region in the mid-domain of the tau protein. Plasma NfL was measured using an in-house digital ELISA on the Simoa-HD1 Platform.

Neuropathologic Assessments

Neuropathologic sampling followed recommendations of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) (Mirra et. al., 1991). Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5 μm thick formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. To evaluate AD neuropathologic change (ADNC), brain sections were immunostained on a ThermoFisher Lab Vision 480S autostainer using 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the chromogen, with primary antibodies against were amyloid-β (mouse monoclonal (6F/3D), DAKO M0872) and phosphotau (mouse monoclonal, AT8; Thermo Fisher MN1020).

AD neuropathologic change was assessed according to recent National Institute on Aging Alzheimer (NIA-AA) criteria (Hyman et. al., 2012, Montine et. al., 2012), including (A) Thal amyloid phase for distribution amyloid-β plaques (Thal et. al., 2002), (B) Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage (Braak et. al., 2006), and (C) CERAD neuritic plaque score (Mirra et al., 1991). Following the NIA-AA criteria, Thal amyloid phase and Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage were recategorized into 4-point scales (absent, low, intermediate, high). The A-B-C scores were subsequently combined into a 4-point scale. A score of 2 or more was considered consistent with a neuropathologic diagnosis of AD.

CVD pathology was evaluated on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections at time of neuropathologic evaluation. Information was retrospectively collected to measure CVD using two published scales. Modified Kalaria scale: Information from neocortical regions (0-6 points) and basal ganglia (0-4 points) on arteriolosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, perivascular tissue rarefaction, perivascular hemosiderin deposition, microscopic infarcts, and large infarcts on both neocortical and basal ganglia sections was used to evaluate CVD severity for a total of 10 points on the modified Kalaria scale (Deramecourt et. al., 2012). The Strozyk scale included information from three macroscopic vascular lesions that included large infarcts (0-2), lacunar infarcts (0-2), and leukoencephalopathy (0-2). The respective scores were assigned, and a total Strozyk score (0-6) was generated (Strozyk et. al., 2010).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The Institutional Review Boards of both Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data availability

Data from the MCSA, including data from this study, are available upon request.

Statistical analysis:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Distributions of the continuous variables were examined for approximate symmetry and normality using plots. Multiple linear regression models with permutation tests and inverse weighting were used to evaluate the associations between the antemortem plasma measures and pathology scales adjusting for age, sex, and time from plasma draw to death. Permutation tests were used because of the small sample size. The weighting was 1/time from plasma draw to death, so that those with plasma draws closer to death received more weight than those farther away. We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding those with a creatinine level greater than 2.0 mg/dl or BMI greater than 35 based on previously published data (Syrjanen et. al., 2021) that these factors may influence plasma amyloid and neurodegeneration markers. We also performed a sensitivity analysis excluding influential observations (Cook’s distance > 1 and qualitative evaluation of changes in significance of predictors) to assess robustness.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

The characteristics of the 64 participants are shown in Table 1. Among the 64 MCSA patients with autopsies, the mean standard deviation (SD) age of death was 84 (6.4) years. and 42 were men (66%). The mean (SD) time from plasma draw to death was 3.0 (1.3) years. Table 2 compares our autopsy sample to deceased MCSA participants who did not undergo autopsy. The characteristics including vascular risk factors of both groups were similar, except the autopsy sample had slightly more years of education.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| N = 64 | |

|---|---|

| Age of death (years) | 83.68 (6.42) |

| Male | 42 (66%) |

| Time to death (years) | 2.97 (1.26) |

| ε4 Carrier | 21 (33%) |

| Education (years) | 14.77 (3.25) |

| Cognitive Status | |

| Cognitive Unimpaired | 45 (70%) |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment | 15 (23%) |

| Dementia | 4 (6.2%) |

| MMSE at last visit | 27.38 (2.04) |

| Aβ 42/40 pg/mL | 0.03 (0.01) |

| NfL pg/mL | 44.33 (38.73) |

| T-tau pg/mL | 3.12 (2.10) |

| Thal Phase | |

| 0 | 7 (11%) |

| 1 | 11 (17%) |

| 2 | 9 (14%) |

| 3 | 15 (23%) |

| 4 | 6 (9.4%) |

| 5 | 16 (25%) |

| Neuritic Plaques | |

| 0 | 17 (30%) |

| 1 | 7 (12%) |

| 2 | 22 (39%) |

| 3 | 11 (19%) |

| Braak Tangle Stages | |

| 1 | 7 (11%) |

| 2 | 13 (20%) |

| 3 | 21 (33%) |

| 4 | 9 (14%) |

| 5 | 11 (17%) |

| 6 | 3 (4.7%) |

| Hypertension | 52 (81%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 45 (70%) |

| Current Smoker | 28 (5.5%) |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 24 (38%) |

Mean (SD) listed for the continuous variables and count (%) for the categorical variables

Table 2.

MCSA Participant Characteristics by Autopsy Status

| Characteristic | Deceased No Autopsy, N = 86 |

Autopsied, N = 64 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death | 86.59 (5.91) | 86.65 (6.61) | 0.7 |

| Male | 65 (76%) | 42 (66%) | 0.2 |

| Education | 13.60 (3.35) | 14.77 (3.25) | 0.046 |

| Hypertension | 64 (74%) | 52 (81%) | 0.3 |

| Diabetes | 41 (48%) | 29 (45%) | 0.8 |

| Stroke | 19 (22%) | 12 (19%) | 0.6 |

| Cognitive status | 0.5 | ||

| Cognitively unimpaired | 54 (63%) | 45 (70%) | |

| MCI | 28 (33%) | 15 (23%) | |

| Dementia | 4 (4.7%) | 4 (6.2%) |

Mean (SD) and n (%) reported

Plasma biomarkers and Alzheimer Disease Neuropathology Scales

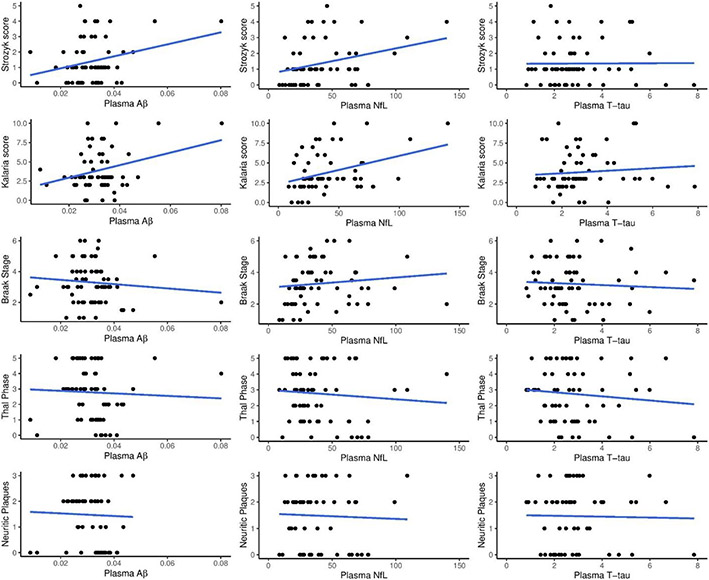

Univariate associations between plasma biomarkers and AD pathology are shown in Figure 1. Multivariable regression analyses between plasma biomarkers (Aβ42/40, NfL, and T-tau) and different AD neuropathologic scales are shown in Table 3. None of the plasma biomarkers were associated with Thal phase, neuritic plaque burden, or Braak tangle stage. There was also no association between plasma biomarkers with AD neuropathologic change: regression estimates were −4.71 (p = 0.882) for Aβ42/40, 0.001 (p = 0.725) for NfL, and 0.116 (p = 0.615) for T-tau.

Figure 1: Units for plasma markers (pg/mL).

Plasma Aβ = Aβ42/40

Table 3.

Multivariable Regressions between Plasma Biomarkers and Neuropathology: regression coefficient (standard error) and p-value for each term.

| Amyloid-β | Tau | Cerebrovascular disease | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thal Phase | Neuritic Plaques |

Braak Score | Strozyk score |

Kalaria score |

|

| Aβ42/40 | −1.4 (21) p = 0.9 | −30 (22) p = 0.62 | −14 (16) p = 0.54 | 43 (17) p = 0.04 | 101 (29) p = 0.001 |

| Partial R 2 | 0 | 0.034 | 0.014 | 0.102 | 0.175 |

| T-tau | 0.05 (0.07) p = 0.82 | 0.07 (0.05) p = 0.84 | 0.04 (0.053) p = 1.0 | 0.10 (0.06) p = 0.90 | 0.05 (0.11) p = 0.96 |

| Partial R 2 | 0.009 | 0.039 | 0.011 | 0.048 | 0.004 |

| NfL | 0.002 (0.006) p = 0.88 | 0.001 (0.006) p = 0.96 | 0.005 (0.004) p = 0.74 | 0.014 (0.005) p = 0.011 | 0.025 (0.008) p = 0.002 |

| Partial R 2 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.019 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

Plasma biomarkers and Cerebrovascular Scales

Univariate associations between plasma biomarkers and CVD scores are shown in Figure 1. Multivariable-regression analysis between plasma biomarkers (Aβ42/40, NfL, and T-tau) and the CVD scores are also shown in Table 2. Higher plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 was associated with higher CVD burden on both the Strozyk (partial r2 = 0.10, p =0.04) and Kalaria scales (partial r2 = 0.18, p =0.001). Plasma NfL correlated with the Strozyk (partial r2= 0.14, p =0.01). and Kalaria vascular scales (partial r2= 0.14, p =0.002), while plasma T-tau was not associated with either vascular scale.

Sensitivity analyses

Because of potential confounders with plasma-biomarker concentrations, we restricted the cohort to serum creatinine values under 2.0 mg/dL and BMIs under 35. . The initial models were then re-run using this restricted cohort. The coefficients for the Kalaria score and Strozyk score outcomes remained significant for both the restricted BMI cohort and the restricted creatinine cohort.

We performed additional sensitivity analyses, excluding potentially influential observations, finding the following results: Aβ42/Aβ40 with Strozyk (p=0.22), Aβ42/Aβ40 with Kalaria (p=0.660), NfL with Strozyk (p=0.068), NfL with Kalaria (p<.001). This means that the associations of Aβ42/Aβ40 with Strozyk and Kalaria, and of NfL with Strozyk, depended upon the presence of the most influential observations (i.e., the associations were no longer present after excluding influential observations). The association of NfL with Kalaria remained significant even when excluding multiple influential observations. Influential observations are not uncommon in small samples, and therefore we decided not to exclude the influential individuals from the main analyses

DISCUSSION

This study investigated neuropathologic underpinnings of plasma biomarkers for amyloid-β and neurodegeneration in a community sample. The key finding was the association of plasma NfL with two scales of CVD pathology, whereas T-tau was not associated with either cerebrovascular disease-pathology scale. Aβ42/Aβ40 was also associated with cerebrovascular disease, but this association should be interpreted with caution because removal of potentially influential participants attenuated these results. None of the plasma biomarkers were associated with neuropathologic measures of AD pathology including Braak tangle stage, Thal amyloid phase, or CERAD neuritic plaque scores or summary of AD neuropathologic change. These findings suggest that plasma markers, especially NfL and possibly Aβ42/Aβ40, are influenced by cerebrovascular disease, which is highly prevalent in the general population.

Prior studies have shown a relationship between plasma NfL and acute cerebrovascular disease (Gendron et al., 2020) and cerebral small-vessel disease (Duering et. al., 2018). The relationship of Nfl to acute cerebrovascular injury appears to be dynamic with an initial elevation followed by a gradual decline but Nfl is prognostically important in the acute and chronic stages of CVD(Gendron et al., 2020, Tiedt et. al., 2018). The current study extends these observations to two scales of chronic CVD. The findings suggest that the association between these plasma Nfl and CVD is related to chronic CVD as well as acute injury.

In some autopsy studies, plasma NfL was associated with Braak neurofibrillary-tangle stage (Ashton et. al., 2019). Plasma NfL predicts clinical decline in presymptomatic familial AD (Preische et. al., 2019). Yet, like the results of an ADNI sample (Grothe et. al., 2021) and other cohorts (Brickman et. al., 2021, Smirnov et. al., 2022, Winder et. al., 2022), the current study detected no relationship between NfL and Thal phase, Braak neurofibrillary-tangle stage, or density of neuritic plaques. A potential explanation for the lack of associations in the present study compared to previous studies is that other studies included convenience cohorts of AD dementia (i.e., higher Braak-tangle stages). Instead, the current study utilized a population-based cohort predominantly composed of cognitively unimpaired participants or those with mild cognitive impairment, perhaps reflecting a limited dynamic range. This suggests that plasma NfL may be a better marker of neurodegeneration related to CVD rather than AD pathology in the general population and a better marker of AD in cohorts with a high burden of AD pathology. While plasma Nfl may have a limited role in diagnosing the presence of AD pathology, several studies have demonstrated that higher Nfl levels predict rate of cognitive decline (Cullen et. al., 2021, Smirnov et al., 2022).

Prior studies demonstrated a relationship between plasma Aβ and cerebrovascular imaging changes including white-matter hyperintensity and cerebral microbleeds (Janelidze et. al., 2016). Similarly, we found a tenuous relationship between higher plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and two CVD pathological scales. Because a low Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio correlates with elevated brain amyloid, the elevated ratio due to CVD pathology could result in a normalization of the ratio in people with amyloidosis and co-existing CVD, thus mischaracterizing underlying brain pathology. Although we detected no relationship between plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and tau or amyloid-β neuropathologic measures, this may be due to the combination of a predominantly cognitively normal cohort and the use of a less disease-specific Aβ assay (i.e., the available Aβ assay was x-42 and x-40 rather than 1-40 and 1-42 or Aβ measured by mass spectroscopy). Because correlations between Aβ blood-based assays are weak (Pannee et. al., 2021) and recent head-to-head studies demonstrate better correlation with brain amyloid for some Aβ assays than others, our results do not generalize to other Aβ measurements. Our study also differs compared to prior pathology-plasma correlative studies because of the study population. Our participants were predominantly cognitively unimpaired with lower AD neuropathologic change compared to prior pathology-plasma studies with more cognitively impaired participants with higher AD neuropathologic change (Grothe et al., 2021). Nonetheless, plasma biomarkers were proposed as screening biomarkers to enrich clinical trials or for early diagnosis, which makes the results in this current study important.

We found no associations of T-tau with AD neuropathologic changes or with CVD scales. T-tau was shown to be less specific for AD biomarkers in vivo than phosphorylated tau (Grothe et al., 2021, Marks et al., 2021).

This study has several limitations. We used a sub-sample of autopsied MCSA participants who had undergone plasma draw within 5 years of death. This sample of the MCSA is comparable to deceased MCSA participants who were not autopsied apart from slightly higher levels of education. The MCSA sample includes predominantly cognitively unimpaired or MCI participants (representative of the general population) and does not have participants with high AD neuropathologic burden; these characteristics of the cohort may have reduced the chances of finding an association of plasma biomarkers with postmortem AD pathology. Studies with larger sample sizes will be needed to confirm the relationship between Aβ42/Aβ40 with less influence from individual observations. Nonetheless, this study highlights the effect of cerebrovascular burden on the concentrations of some plasma markers, particularly NfL. Newer plasma markers with stronger associations to AD pathology, such as phosphorylated tau217 or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio measured by mass spectroscopy, may be more specific to AD pathology. Whether CVD influences the levels of these newer plasma biomarkers will need be evaluated in the future with in vivo and autopsy studies.

Highlights.

A population-based study, mostly without dementia or modest Alzheimer’s pathology

Antemortem plasma NfL and Aβ42/40 correlate with cerebrovascular neuropathy scales

Plasma T-tau did not correlate with any neuropathologic assessment

Unspecific amyloid-β assays may link elevated Aβ42/40 with cerebrovascular pathology

Cerebrovascular disease impact on plasma biomarker concentration needs more study

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lea Dacy, Department of Neurology, for proofreading and formatting assistance.

Study funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number RF1 AG069052-01A and the NIH (AG006786, AG011378, NS097495, AG16574, AG041851, AG054449, AG034676), and the GHR Foundation. The funders had no role in the conception or preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

JGR, CRJ, DSK, RCP, MEM and PV are investigators on grants that supported this research. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests. Additionally, they report the following disclosures:

J. Graff-Radford serves on the editorial board for Neurology and receives research support from the NIH.

M.M. Mielke has consulted for Biogen, Brain Protection Company, and LabCorp. She receives research support from NIH and DOD.

EI Hofrenning reports no relevant financial disclosures

N Kouri reports no relevant financial disclosures

T.G. Lesnick reports no relevant financial disclosures

C.M. Moloney reports no financial disclosures.

A.A. Rabinstein reports no relevant financial disclosures

J.N. Cabrera-Rodriguez reports no relevant financial disclosures

D M. Rothberg no relevant financial disclosures.

S.A. Przybelski reports no relevant financial disclosures

R.C. Petersen serves as a consultant for Roche, Inc.; Merck, Inc.; Biogen, Inc., and on a DSMB for Genentech, Inc. He receives royalties from Oxford University Press and UpToDate. He receives NIH funding.

D.S. Knopman served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for the DIAN study. He serves on a Data Safety monitoring Board for a tau therapeutic for Biogen but receives no personal compensation. He is a site investigator in the Biogen aducanumab trials discussed here. He is an investigator in a clinical trial sponsored by Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the University of Southern California. He serves as a consultant for Samus Therapeutics, Third Rock, Roche, and Alzeca Biosciences but receives no personal compensation. He receives research support from the NIH.

D.W. Dickson receives research support from the NIH, the DOD, the Tau Consortium, the Target ALS Foundation, Inc., the Rainwater Charitable Foundation, and the American Parkinson Disease Foundation.

C.R. Jack serves on an independent data monitoring board for Roche, has served as a speaker for Eisai, and consulted for Biogen, but he receives no personal compensation from any commercial entity. He receives research support from NIH and the Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Clinic.

A. Algeciras-Schimnich serves on advisory boards for Roche Diagnostics and Fujirebio Diagnostics.

A. T. Nguyen reports no disclosures

ME. Murray served as a consultant for AVID Radiopharmaceuticals.

P. Vemuri received speaker fees from Miller Medical Communications, Inc., and receives research support from the NIH.

Correlation of Plasma Biomarkers of Amyloid and Neurodegeneration with Cerebrovascular Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease

The corresponding author, Jonathan Graff-Radford, affirms that the co-authors, all of whom meet the requirements for authorship in Annals of Neurology, have reviewed and approved the contents of this manuscript. This submission has not been submitted nor is it under review at any other journal. All financial or other relationships that might lead to a perceived conflict of interest have been disclosed. The funding sources were not involved in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. As corresponding author, Dr. Graff-Radford has full access to all the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and the Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols. All participants provided written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Availability of data and materials

Data from the MCSA, including from this study, are available upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Competing Interest

JGR, CRJ, DSK, RCP, MEM, and PV are investigators on grants that supported this research. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- American Psychiatric Association D, Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American psychiatric association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton NJ, Leuzy A, Lim YM, et al. Increased plasma neurofilament light chain concentration correlates with severity of post-mortem neurofibrillary tangle pathology and neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019;7:5; 10.1186/s40478-018-0649-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 2006;112:389–404; 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Manly JJ, Honig LS, et al. Plasma p-tau181, p-tau217, and other blood-based Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in a multi-ethnic, community study. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2021;17:1353–64; 10.1002/alz.12301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen NC, Leuzy A, Janelidze S, et al. Plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease improve prediction of cognitive decline in cognitively unimpaired elderly populations. Nat Commun 2021;12:3555; 10.1038/s41467-021-23746-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer S, Schaeverbeke JM, Verberk IMW, et al. Comparison of ELISA- and SIMOA-based quantification of plasma Aβ ratios for early detection of cerebral amyloidosis. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020; 12:162; 10.1186/s13195-020-00728-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos A, Bjerke M, Brouns R, et al. Neurogranin and tau in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of patients with acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol 2017;17:170; 10.1186/s12883-017-0945-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deramecourt V, Slade JY, Oakley AE, et al. Staging and natural history of cerebrovascular pathology in dementia. Neurology 2012;78:1043–50; 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8e7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duering M, Konieczny MJ, Tiedt S, et al. Serum Neurofilament Light Chain Levels Are Related to Small Vessel Disease Burden. J Stroke 2018;20:228–38; 10.5853/jos.2017.02565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron TF, Badi MK, Heckman MG, et al. Plasma neurofilament light predicts mortality in patients with stroke. Sci Transl Med 2020;12 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe MJ, Moscoso A, Ashton NJ, et al. Associations of Fully Automated CSF and Novel Plasma Biomarkers With Alzheimer Disease Neuropathology at Autopsy. Neurology 2021;97:e1229–42; 10.1212/wnl.0000000000012513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2012;8:1–13; 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illán-Gala I, Lleo A, Karydas A, et al. Plasma Tau and Neurofilament Light in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2021;96:e671–e83; 10.1212/wnl.0000000000011226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janelidze S, Stomrud E, Palmqvist S, et al. Plasma β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular disease. Scientific Reports 2016;6:26801; 10.1038/srep26801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern S, Syrjanen JA, Blennow K, et al. Association of Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Protein With Risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment Among Individuals Without Cognitive Impairment. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:187–93; 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks JD, Syrjanen JA, Graff-Radford J, et al. Comparison of plasma neurofilament light and total tau as neurodegeneration markers: associations with cognitive and neuroimaging outcomes. Alzheimers Res Ther 2021;13:199; 10.1186/s13195-021-00944-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Association of Plasma Neurofilament Light With Neurodegeneration in Patients With Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol 2017;74:557–66; 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.6117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Janelidze S, et al. Plasma tau in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2016;87:1827–35; 10.1212/wnl.0000000000003246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke MM, Hagen CE, Wennberg AMV, et al. Association of Plasma Total Tau Level With Cognitive Decline and Risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia in the Mayo Clinic Study on Aging. JAMA Neurology 2017;74:1073–80; 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke MM, Syrjanen JA, Blennow K, et al. Plasma and CSF neurofilament light: Relation to longitudinal neuroimaging and cognitive measures. Neurology 2019;93:e252–e60; 10.1212/wnl.0000000000007767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1991;41:479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 2012;123:1–11; 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren N, Rosengren L, Stigbrand T. Elevated neurofilament levels in neurological diseases. Brain Res 2003;987:25–31; 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannee J, Shaw LM, Korecka M, et al. The global Alzheimer's Association round robin study on plasma amyloid β methods. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2021;13:e12242; 10.1002/dad2.12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, JJoim. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. 2004;256:183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preische O, Schultz SA, Apel A, et al. Serum neurofilament dynamics predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine 2019;25:277–83; 10.1038/s41591-018-0304-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology 2008;30:58–69; 10.1159/000115751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov DS, Ashton NJ, Blennow K, et al. Plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease in relation to neuropathology and cognitive change. Acta Neuropathologica 2022;143:487–503; 10.1007/s00401-022-02408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strozyk D, Dickson DW, Lipton RB, et al. Contribution of vascular pathology to the clinical expression of dementia. Neurobiol Aging 2010;31:1710–20; 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrjanen JA, Campbell MR, Algeciras-Schimnich A, et al. Associations of amyloid and neurodegeneration plasma biomarkers with comorbidities. Alzheimers Dement 2021. 10.1002/alz.12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002;58:1791–800; 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedt S, Duering M, Barro C, et al. Serum neurofilament light: A biomarker of neuroaxonal injury after ischemic stroke. Neurology 2018;91:e1338–e47; 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder Z, Sudduth TL, Anderson S, et al. Examining the association between blood-based biomarkers and human post mortem neuropathology in the University of Kentucky Alzheimer's Disease Research Center autopsy cohort. Alzheimers Dement 2022. 10.1002/alz.12639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the MCSA, including data from this study, are available upon request.

Statistical analysis:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Distributions of the continuous variables were examined for approximate symmetry and normality using plots. Multiple linear regression models with permutation tests and inverse weighting were used to evaluate the associations between the antemortem plasma measures and pathology scales adjusting for age, sex, and time from plasma draw to death. Permutation tests were used because of the small sample size. The weighting was 1/time from plasma draw to death, so that those with plasma draws closer to death received more weight than those farther away. We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding those with a creatinine level greater than 2.0 mg/dl or BMI greater than 35 based on previously published data (Syrjanen et. al., 2021) that these factors may influence plasma amyloid and neurodegeneration markers. We also performed a sensitivity analysis excluding influential observations (Cook’s distance > 1 and qualitative evaluation of changes in significance of predictors) to assess robustness.