SUMMARY

A possible explanation for chronic inflammation in HIV-infected individuals treated with anti-retroviral therapy is hyperreactivity of myeloid cells due to a phenomenon called “trained immunity.” Here, we demonstrate that human monocyte-derived macrophages originating from monocytes initially treated with extracellular vesicles containing HIV-1 protein Nef (exNef), but differentiating in the absence of exNef, release increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines after lipopolysaccharide stimulation. This effect is associated with chromatin changes at the genes involved in inflammation and cholesterol metabolism pathways and upregulation of the lipid rafts and is blocked by methyl-β-cyclodextrin, statin, and an inhibitor of the lipid raft-associated receptor IGF1R. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from exNef-injected mice, as well as from mice transplanted with bone marrow from exNef-injected animals, produce elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) upon stimulation. These phenomena are consistent with exNef-induced trained immunity that may contribute to persistent inflammation and associated co-morbidities in HIV-infected individuals with undetectable HIV load.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

HIV-infected individuals live with low-level inflammation even when the virus is suppressed by anti-retroviral therapy. Dubrovsky et al. demonstrate that exosomes carrying HIV-1 protein Nef (exNef) induce long-lived pro-inflammatory memory in myeloid cells. This effect is reproduced in mice injected with exNef. These findings are consistent with exNef-induced trained immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Combination anti-retroviral therapy (cART) has dramatically altered the course and prognosis of HIV infection, changing it from a fatal condition to a manageable chronic disease.1 However, despite a significantly increased life expectancy, people living with HIV (PLWH), even those who consistently maintain undetectable viral load, remain at increased risk of developing a range of co-morbidities that affect both longevity and the quality of life of this population.2 These co-morbidities, which include cardiovascular disease (CVD) and neurocognitive dysfunction (HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder [HAND]), have one common feature underlying their pathogenesis—persistent low-grade inflammation.3 Indeed, PLWH show a persistent increase in inflammatory markers and chronic immune activation.4,5 This has been attributed to bacterial leakage due to disruption of the tight junctions in the intestinal epithelium.6 Another potential cause for persistent inflammation may be the continuous release of HIV-related pro-inflammatory factors, in particular Nef protein, from the viral reservoirs.3,7,8 Nef is released from HIV-infected cells predominantly as a component of exosomes (exNef),9-13 and exNef was shown to exert a potent pro-inflammatory effect via suppression of cholesterol efflux and elevation of the lipid raft abundance on myeloid cells.14

Yet another possible contributor to the observed long-term immune activation might be a “legacy effect,” when exposure to a pathogen produces effects that last long after the pathogen is eliminated. One mechanism of this phenomenon is “trained immunity.”15-17 This paradigm, introduced by Netea and colleagues a decade ago,17 provides an elegant explanation for the long-known phenomenon of immunologic memory associated with the innate immune responses.18-20 The mechanism of this effect was shown to be metabolic-epigenetic, defined here as changes in cell metabolism leading to a modification of the chromatin composition in myeloid cells occurring in response to an infectious agent and resulting in increased expression of pro-inflammatory genes after a subsequent stimulation with an unrelated pathogen.21 Factors that have subsequently been shown to induce trained immunity include microbial and non-microbial stimuli, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), β-glucan, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), lipoprotein (a), and aldosterone.22-27 The present study was undertaken to investigate whether exposure to Nef, the key pathogenic factor of HIV,28-31 leaves a memory in monocyte-derived macrophages that may contribute to increased inflammatory responses to subsequent stimulation.

RESULTS

Long-lived hyperreactivity induced by exNef

To investigate the ability of Nef to induce long-lived hyperreactivity of myeloid cells, a key feature of trained immunity, we used an approach introduced by the Netea’s group.32 Isolated human primary monocytes were exposed for 48 h to Nef, washed, and left in the culture medium for 6 days to differentiate into monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), which then were restimulated with LPS (Figure 1A). The change in cytokine production after stimulation, relative to cells not exposed to Nef, was taken as a marker of trained immunity. Given that physiologically active Nef is believed to be associated with the extracellular vesicles (EVs),9-13 we used EVs produced by Nef-transfected HEK293T cells (exNef) as a source of Nef; EVs from RFP-transfected cells (exCont) served as controls. These EVs were characterized in our previous studies and shown to exhibit the size and markers characteristic for exosomes.33 Results in Figure S1A confirm this conclusion and also show that exCont and exNef samples had similar numbers of vesicles per mL of EV preparation (Figure S1B). Analysis of cytokine production after LPS stimulation is presented in Figure 1B and demonstrates increased production of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) by MDMs that differentiated from monocytes exposed to exNef relative to those exposed to exCont.

Figure 1. Analysis of exNef effects in vitro.

(A) Diagram of in vitro experiments in this study. Monocytes treated with exNef or exCont in the presence or absence of methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), fluvastatin (Flu), or picropodophyllin (PPP) were analyzed by western blotting (WB) for flotillin 1 (Flot1) or by flow cytometry for lipid rafts (staining with CTB) and IGF1R. After differentiation in the presence of M-CSF, MDMs were characterized by t-SNE for activation markers or by ddPCR for gene expression. Following LPS stimulation, gene expression was characterized by RNA-seq and cytokine production measured by ELISA. See also Tables S1 and S2.

(B) Analysis of TNF-α and IL-6 production by LPS-treated MDMs. The graph shows fold increase of cytokine production by exNef-treated over exCont-treated cells from 8 donors (8 biological replicates, 3 technical replicates for each donor), analyzed by Friedman multiple comparison test with Dunn’s correction. Adjusted p values are shown above bars.

(C) Dose response analysis. The graph shows mean ± SEM (3 technical replicates of cells from a single donor) fold increase of TNF-α produced by MDMs exposed to exNef with indicated concentrations of Nef versus MDM exposed to exCont at the same concentration of EVs.

(D) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)34 showing normalized enrichment scores for genes differentially expressed between exNef and exCont and participating in the inflammatory response (left panel) and cytokine pathway (right panel); the gene sets were obtained from BioCarta.35

(E) Leading edge analysis shows that a number of cytokine genes drive the changes of pathways dysregulated by exNef.

See also Figures S1-S3.

The concentration of Nef in exNef EVs was 44.4 pg/mL, lower than the Nef concentration of 5 ng/mL and over detected in the blood of about half of ART-treated patients with undetectable HIV load,36 suggesting that observed training can take place in HIV-infected individuals. Titration analysis demonstrated that enhanced responses to LPS stimulation went down when exNef vesicles were diluted to Nef concentration of 25 pg/mL and completely disappeared at 10 pg/mL (Figure 1C). However, even at the lowest Nef concentration, the number of added EVs was over 1 × 108 per mL, arguing against the possibility that some other factor than Nef associated with EVs was responsible for the observed phenomenon. The key role of Nef was further supported by the finding that training could be induced by treatment of the cells with recombinant Nef, although at substantially higher concentrations (over 5 ng/mL) than EV-associated Nef (Figure S2).

Given that non-myristoylated Nef mutant G2A is often used as a negative control in Nef experiments,37-39 we also tested this mutant. Results in Figure S3A show that Nef G2A was expressed at a high level, but no Nef G2A could be detected in the EVs (Figure S3B), and no trained immunity was induced by these vesicles (Figure S3C). Together with failure of this mutant to reproduce other Nef activities,40,41 this argued against any advantage of this control over EVs collected from RFP-transfected cells.

The increased response to inflammatory stimuli observed with exNef training resembled the previously described response of MDMs to treatment with Nef or exNef.14,42 However, in contrast to the previous studies, in this report we investigated delayed responses that were maintained in the presumed absence of Nef. To determine how long the trained phenotype persists in culture, we analyzed responses after 1 and 2 weeks of MDM culture. Results in Figure S3C show that increased responses to LPS stimulation, monitored by production of TNF-α, were observed up to week 2 in culture. Analysis of longer incubation times was impossible due to reduced cell viability.

To assess the genome-wide gene expression changes associated with exNef treatment, we performed whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of LPS-stimulated exNef-trained MDMs from eight donors (data deposited in GEO: GSE214959). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA34) on the top deregulated genes (based on p value and fold change) showed that the most upregulated gene sets were enriched for genes involved in cytokine and inflammatory pathways (Figure 1D). Furthermore, leading-edge analysis showed several other affected pathways and identified a number of genes, including IL-2, IL-3, IL-6, IL-11, IL-10, IL-18, CXCL8, and TNFα, that drive the activation of these pathways (Figure 1E).

To determine whether long-lived hyperreactivity observed with monocytes treated with exNef in vitro also occurs in vivo, we intravenously injected either exNef or exCont into C57BL/6J mice, isolated BMDMs, and tested their responses to LPS stimulation after 7 and 15 days of culture in the absence of EVs (Figure 2A, top diagram). Analysis of cells isolated from bone marrow demonstrated a lower abundance of ABCA1 in cells from exNef-treated animals (Figure 2B), an expected effect of exNef.14 Plasma membranes isolated on day 7 from bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) of animals treated with exNef had increased lipid rafts (determined as incorporation of exogenous [3H]cholesterol and abundance of flotillin-1 in gradient fractions corresponding to the lipid rafts, fractions 2–4, Figure 2C) relative to cells from animals treated with exCont. Correspondingly, in response to LPS stimulation, BMDMs from mice treated with exNef produced significantly more TNF-α on day 7 than cells from exCont-injected mice (Figure 2D). Cells stimulated with LPS on day 15 produced very little TNF-α, likely due to cell deterioration, and differences between cells from exCont- and exNef-treated animals were not significant.

Figure 2. Analysis of exNef effects in vivo.

(A) Diagram of in vivo experiments in this study. Top diagram: mice were injected with exCont or exNef, and BMDMs were isolated, analyzed for ABCA1 abundance, and cultured for 7 or 15 days without EVs. Following LPS stimulation, TNF-α secretion over 1 h was measured by ELISA. Bottom diagram: bone marrow from mice injected with exCont or exNef was transplanted to irradiated mice, which were maintained for 11 weeks; LPS was injected 24 h prior to termination to stimulate myelopoiesis. Following 9 days of differentiation, BMDMs were analyzed for ABCA1 abundance and LPS-stimulated TNF-α secretion.

(B) Left panel: western blot of ABCA1 and Na/K ATPase (loading control) of cell lysate of bone marrow cells from individual mice injected with exCont or exNef; right panel: densitometric analysis of the gel (abundance of ABCA1 relative to Na/K ATPase). Plot shows 6 biological replicates (each has one technical replicate). p value was calculated by two-tailed parametric t test.

(C) BMDMs derived from bone marrow of animals injected with either exNef or exGFP (7 days after isolation) were labeled in vitro with [3H]cholesterol. Membrane fraction was separated in a density gradient. [3H]cholesterol content was determined in the gradient fractions by β-counting (left panel), and Flot1 content was determined by densitometry of Flot1 bands after western blotting (right panel). AUC, area under the curve. ***p < 0.001 (difference between the curves, paired t test).

(D) TNF-α secreted over 1 h by BMDMs isolated as in (B) and stimulated with LPS on day 7 or 15. Plot shows 6 biological replicates averaged from 4 technical replicates. p value (only significant difference is shown) was calculated by two-tailed parametric t test.

(E) Left panel: western blot of ABCA1 and Na/K ATPase (loading control) of cell lysate of BMDM (9 days after plating) from individual mice transplanted with bone marrow from mice injected with exCont or exNef; right panel: densitometric analysis of the gel (abundance of ABCA1 relative to Na/K ATPase, arbitrary units). Plot shows 6 biological replicates (each has one technical replicate). p value was calculated by two-tailed parametric t test.

(F) TNF-α secreted over 4 h by BMDMs isolated as in (E) and stimulated with LPS on day 9 after plating. Plot shows 6 biological replicates averaged from 4 technical replicates. p value was calculated by two-tailed parametric t test.

This finding suggested that exNef modified bone marrow myeloid progenitor cells, which differentiated into hyperresponsive BMDMs. To further investigate this phenomenon, we transplanted bone marrow from exCont- or exNef-injected mice into irradiated recipient mice, maintained them for 11 weeks, then collected bone marrow, isolated adherent cells, differentiated them into BMDMs for 9 days, and analyzed ABCA1 and TNF-α response to LPS stimulation (Figure 2A, bottom diagram). Similar to cells collected from EV-injected mice (Figures 2B and 2D), BMDMs from mice transplanted with bone marrow from mice exposed to exNef exhibited lower ABCA1 abundance (Figure 2E) and produced higher levels of TNF-α in response to LPS stimulation (Figure 2F) than BMDMs from mice transplanted with bone marrow exposed to exCont. This result supports the notion that exNef induces a long-lasting memory in bone marrow progenitor cells, which affects cholesterol homeostasis and response to inflammatory stimuli in the resulting BMDMs, and is consistent with trained immunity described by Netea and colleagues.43

Characterization of trained MDMs

Following differentiation of “trained” monocytes into MDMs in the absence of Nef, cells were analyzed by multi-color flow cytometry (see Figure 1A). The cell markers in this analysis were CD14, CD16, CD-11b, CD40, CD163, CD38, CD80, CD64, HLA-DR, and CD68, which are associated with the role of macrophages in pro- and anti-inflammatory responses, although the precise assignment of a certain marker to a particular phenotype remains controversial.44,45 Pretreatment of monocytes with exNef resulted in significant changes in the distribution of differentiated MDMs between the populations, characterized by levels of marker expression presented as t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot (Figure 3A). All cell populations enriched by exNef treatment (over 50% increase in cell numbers) were characterized by low expression of CD16 (peaks shifted to the left of the diagram), and most had high expression of CD80, CD64, CD68, and HLA-DR (Figure 3B). The CD16low phenotype is a characteristic associated with M1 macrophages.46 Analysis of cells from 2 additional donors confirmed the effect of exNef on expression of inflammation-associated markers in MDMs (Figure S4). Again, CD16 expression was low in cells from most populations enriched after exNef treatment. Although specific patterns of the changes somewhat differed between the donors, high expression of CD40, CD64, and CD11b was noted in several populations of exNef-pretreated cells from donors B and C (Figure S4). These results indicate that treatment of monocytes with exNef altered their differentiation, promoting a pro-inflammatory phenotype.

Figure 3. Characterization of trained MDMs.

(A) Equal amounts of one donor’s MDMs exposed to exCont or exNef were subjected to t-SNE analysis. Results are shown for ungated population and after gating on exCont- or exNef-exposed cells.

(B) Phenotypic outcome was evaluated in the populations where exNef-treated cells prevailed over exCont-treated cells by 50% or more. Top left panel shows distribution of these cell populations, and the table underneath presents the frequency of parent population for each cluster. The diagrams on the right show expression of indicated markers on the cells of each color-coded population.

(C) The heatmap shows the genes from the inflammation and cholesterol metabolism pathways that changed localization between open and closed chromatin regions as a result of exNef treatment. Results are shown for cells from 4 donors treated with exCont or exNef.

See also Figure S4.

Previous studies demonstrated the key role of epigenetic changes in the trained immunity phenotype.47 To determine whether exNef induced epigenetic modifications in monocytes, we employed assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) to reveal changes in localization of gene promoters to the open (active) chromatin regions (data deposited in GEO: GSE214959). This analysis was performed in MDMs from 4 donors prior to LPS stimulation (Figure 1A). Substantial inter-donor variability was observed in the identity of the genes affected by exNef treatment, suggesting a significant effect on trained immunity of individual-specific characteristics (genotype, age, gender, inflammatory status, etc.). We focused the ATAC-seq analysis on 1,092 genes involved in the cholesterol metabolism, inflammation, and aerobic glycolysis pathways (Table S1), which were found to be involved in regulation of trained immunity.48 The most affected genes from this gene set that changed localization between open and closed chromatin as a result of exNef treatment are shown in Figure 3C. Genes found in open chromatin regions following exNef treatment were SMAD2, which mediates the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) pathway,49 RTN3, involved in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) autophagy,50 ABCB11, which participates in lipid homeostasis through regulation of biliary lipid secretion,51 CASP6, which is involved in regulation of inflammatory cytokine production,52,53 and IL17RA, a receptor for the inflammatory cytokine IL-17A,54 and those in closed chromatin were DNAH11, associated with ciliary dyskinesia,55 and SC5D, directly involved in the biosynthesis of cholesterol56 (Table S2).

Training is sensitive to inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis and IGF1R signaling

Previous study of the β-glucan-induced trained immunity demonstrated the role of aerobic glycolysis, increased production of mevalonate, its secretion, and autocrine stimulation of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R), signaling from which greatly potentiated training.48 To determine if similar mechanisms operate in the long-lived hyperreactivity induced by exNef, we analyzed lactate production by exNef-trained MDMs. On day 7 of MDM differentiation in the absence of exNef, the concentration of lactate in culture supernatant of cells exposed to exNef was over 2-fold higher than in culture of cells exposed to control EVs (Figure 4A), indicating that glycolysis was stimulated by exNef. This effect was confirmed when cells from 4 different donors were analyzed, although the absolute concentrations of lactate varied (Figure S5). We then analyzed expression of several cholesterol biosynthesis rate-limiting genes in MDMs exposed to exNef or exCont. This analysis revealed upregulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) in cells treated with exNef (Figure 4B). No significant changes were detected in expression of two other tested genes, squalene epoxidase (SQLE) and mevalonate kinase (MVK) (Figure 4B). Cholesterol biosynthesis (measured by assessing [3H]acetate incorporation into cholesterol) in monocytes is very low,57 preventing reliable detection of significant differences between exCont- and exNef-treated cells. However, when differentiated MDMs were treated with exNef, they showed an increased rate of cholesterol biosynthesis relative to cells treated with exCont (Figure 4C). This finding is consistent with previously demonstrated activation of cholesterol biosynthesis genes’ expression by endogenously expressed Nef.58 The role of cholesterol biosynthesis induction in training was supported by the suppressive effect of an inhibitor of HMGCR, fluvastatin, on exNef-induced training (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Mechanisms of exNef-induced training.

(A) Analysis of lactate in the supernatant of MDM cultures on day 6 after washing out the EVs. Results are presented as means ± SD of six replicate determinations (technical replicates) using cells from a single donor (1 biological replicate). p value was calculated using unpaired two-tailed parametric t test. See also Figure S5.

(B) Results of ddPCR analysis of monocytes treated with exCont or exNef (24 h after removal of EVs). Bars show fold increase of gene expression in exNef-treated, relative to exCont-treated, cells. Analysis was performed in cells from 4 donors (4 biological replicates, each one is average of 3 technical replicates), and results were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett correction for multiple comparisons. Adjusted *p = 0.0464.

(C) Incorporation of [14C]acetate into cholesterol after 2 h incubation with MDMs treated with exCont or exNef. Bars show means ± SD of disintegrations per minute (dpm) per mg of total cell protein from quadruplicate determinations (4 technical replicates, 1 biological replicate). p value was calculated by unpaired two-tailed parametric t test.

(D) ExNef-induced upregulation of TNF-α production by LPS-treated MDMs was inhibited by Flu and PPP (added with EVs) and by MβCD (added after washout of EVs). Analysis was performed on cells from one donor (1 biological replicate) assayed in 6 replicate wells (6 technical replicates). Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, with Holm-Sidak’s correction for multiple comparisons. Adjusted **p = 0.0045.

(E) MTT assay was performed on MDMs from a single donor (1 biological replicate) exposed to indicated agents prior to LPS stimulation. Bars show means ± SD of 6 determinations (6 technical replicates). Results were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. *p = 0.0205.

(F) IGF1R presentation on MDMs exposed to exNef and exCont. Monocytes were analyzed 48 h after washout of EVs.

Similar to observations with β-glucan-induced trained immunity,48 exNef-induced training was also blocked by picropodophyllin (PPP), an inhibitor of IGF1R signaling (Figure 4D). Interestingly, PPP not only eliminated training-specific increase of TNF-α production by exNef-exposed cells but also suppressed the response in cells treated with exCont (Figure 4D). To exclude the possibility of cell toxicity, we measured cell metabolism using an MTT assay. This analysis did not find significant toxicity of any of the agents used in this experiment (Figure 4E). Therefore, IGF1R signaling contributes to physiological responses to LPS. In contrast to β-glucan, exNef increased the presentation of IGF1R on the membrane of treated cells (Figure 4F). Interestingly, exNef did not increase the mRNA expression of IGF1R (Figure 4B), suggesting that a post-transcriptional mechanism was responsible for increased IGF1R presentation on the membrane. Thus, training induced in monocytes by exNef has properties similar to immune training described by Netea and colleagues.43

The role of lipid rafts in exNef-induced trained immunity

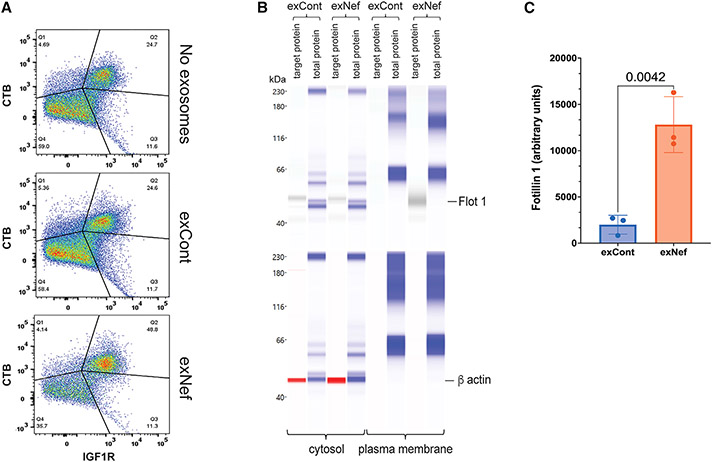

ExNef has been shown to increase the abundance of lipid rafts on target cells, promoting activity of lipid raft-associated receptors.14 Given that IGF1R is associated with lipid rafts,59-63 exNef-mediated increase in IGF1R presentation (Figure 4F) and immune training may be controlled at the level of the lipid rafts. Indeed, exNef increased the percentage of monocytes double positive for staining of IGF1R and lipid rafts (Figure 5A). This result was confirmed by analysis of the lipid raft component flotillin-1 in the plasma membrane of the cells treated with exNef and exCont: a significantly higher abundance of flotillin-1 was detected in exNef-treated cells (Figure 5B and 5C). The role of the lipid rafts in exNef-induced training was further supported by the reversal of the training-specific increase of TNF-α production by treatment of the monocytes with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) (Figure 4D), which disrupts lipid rafts by extracting cholesterol.

Figure 5. ExNef upregulates lipid rafts.

(A) CTB staining of lipid rafts in monocytes treated with exNef or exCont. Monocytes were analyzed 48 h after washout of EVs.

(B) Flot1 was analyzed in plasma membranes isolated from monocytes after washout of EVs following treatment with exCont or exNef. Total protein staining provided loading control.

(C) Bars show mean ± SD of gel area corresponding to Flot1 band adjusted to total protein, calculated for cells from 3 donors (3 biological replicates, 1 technical replicate). p value was calculated by unpaired two-tailed t test.

Taken together, these findings suggest that exNef induces trained immunity by stimulating cholesterol biosynthesis and increasing the abundance of the lipid rafts, thus increasing presentation of IGF1R and its signaling.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed how treatment of monocytes with EVs carrying HIV-1 protein Nef (exNef) induces a pro-inflammatory memory in MDMs that differentiate from treated monocytes. Our findings demonstrate exNef-induced changes in chromatin composition of MDMs associated with enhanced secretion of two key inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-6, and increased expression of other pro-inflammatory genes. In contrast to previously demonstrated pro-inflammatory effects of Nef on MDMs,14,42,64-68 the effects reported here are delayed and are maintained for extended periods of time in vitro and in vivo. These effects of exNef on monocytes are similar to those of β-glucan, as described by Quintin et al.69 and termed “trained immunity.”70 The trained immunity paradigm implies preservation of the trained phenotype in the absence of the initiating factor. Whereas we cannot prove that no Nef remained in the cells, results of bone marrow transplantation experiments, where over 12 weeks and multiple cell divisions separated exNef exposure and BMDM stimulation, make the possibility that residual Nef is the cause of enhanced response to LPS highly unlikely.

Phenotypic analysis of MDMs produced from monocytes exposed to exNef revealed formation of new cell populations characterized by expression of several markers associated with the M1 polarization. None of these populations expressed a classical M1 phenotype, consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that training of monocytes does not induce classical M1 or M2 macrophage phenotypes.22,69 This is particularly true for in vitro differentiation, where polarization may be skewed by growth factors.71 M-CSF used in our study is known to skew monocyte polarization toward the M2 status, whereas exNef stimulated expression of M1-specific markers, counteracting activity of M-CSF. We used ATAC-seq to identify genes whose promoters were associated with open chromatin regions. Previous studies detected activation of multiple genes belonging to metabolic and inflammatory pathways in β-glucan-trained MDMs.21,27,32,70,72 Consistent with these reports, in exNef-trained MDMs, we found changes in the open chromatin regions of genes associated with inflammation and cholesterol metabolism; activation of these pathways may contribute to the co-morbidities in PLWH. Consistent with functional manifestations of trained immunity, MDMs trained with exNef responded to LPS stimulation with increased expression levels of a number of genes, including IL-3, IL-6, IL-9, IL-11, CXCL8, CSF3, CSF2, and TNF-α. The mechanism behind exNef-induced trained immunity is consistent with that described for β-glucan:48 it depends on activation of aerobic glycolysis, cholesterol biosynthesis, and IGF1R signaling.

Another important component of exNef-induced trained immunity is an increased abundance of the lipid rafts. This effect is likely caused by exNef-mediated suppression of ABCA1 activity14 and may lead to an increase in IGF1R signaling, which is a key mechanism of training.48,70 Decreased abundance of ABCA1 was maintained in BMDMs for an extended time, suggesting that effects of exNef on cholesterol homeostasis are long lived. Long-lived effects on the cholesterol metabolism pathway would lead to sustained changes in the abundance and properties of the lipid rafts, which need to be taken into consideration in future studies of trained immunity induced by other factors.

The contribution of the observed hyperresponsiveness of myeloid cells to pathogenesis of HIV disease and HIV-associated co-morbidities remains to be investigated. While evolutionary trained immunity has evolved as a protection mechanism, enhanced responses of monocytes/macrophages of HIV-infected individuals to inflammatory stimuli due to trained immunity may explain sustained low-level inflammation when viral load is reduced to undetectable levels by ART.5,73 Further, in HIV infection, this protective mechanism may be unable to deal with a long-lasting influx of pathogenic factors, such as exNef continuously released from HIV reservoirs7 and bacterial products leaking through incompletely recovered mucosal tissue.74 Thus, contribution of exNef to HIV co-morbidities may be two-fold: induction of long-lasting hyperresponsiveness of myeloid cells and persistent stimulation of these cells.

The half-life of circulating monocytes is relatively short (several days), but a possibility of training by exNef of myeloid progenitor cells, as suggested by our in vivo studies, may provide a long-lasting memory. Thus, even complete cure of HIV infection may still leave infected individuals hyperresponsive to inflammatory stimuli. This may provide a protective effect for acute infections but may put them at risk for inflammation-associated diseases if chronic stimuli are encountered. How long such memory can persist is an important question, but recent findings by Netea’s group suggested that even a transgenerational transmission of trained immunity is possible.75,76

In conclusion, we demonstrated that EVs carrying HIV protein Nef trigger long-lasting changes in inflammatory responses of the host by mechanisms consistent with trained immunity. This phenomenon may contribute to the persistent chronic inflammation in PLWH. More broadly, trained immunity may also explain the origin of persistent metabolic comorbidities following other viral infections, including COVID-19.77

Limitations of the study

One limitation is a variability of results between different donors in our genetic and epigenetic analyses. Such variability is expected in human samples, and a much larger number of donors needs to be analyzed to obtain quantitative results. Although we established a contribution of trained immunity to inflammatory responses, the relative contribution of this effect compared with other mechanisms in vivo was not evaluated and neither were different mechanisms compared with each other directly. Finally, our study suggests, but does not provide direct evidence for, the role of trained immunity in HIV-associated co-morbidities. Studies in animal models and humans will be required to establish this connection.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Michael Bukrinsky (mbukrins@gwu.edu).

Materials availability

There are restrictions to the availability of EVs due to substantial staff effort required for their production.

Data and code availability

All sequencing datasets generated or analyzed during this study are deposited in GEO: GSE214959. The other data will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Primary human monocytes

Buffy coats from healthy donors were purchased from Gulf Coast Blood Center. Information about the sex or age of donors was not provided to us. PBMCs were isolated by density centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) and, after washing 3 times with PBS, cells (9 × 106/mL) were plated in Primaria T-75 flasks or Primaria plates in Dutch modified RPMI (Gibco) supplemented with 1% Pen/Strep (Corning), 10 mM L-Glutamine (Corning) and 10 mM sodium pyruvate (Corning) and incubated in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 for 2 h to adhere to plastic. Non-adhered cells were removed by washing 3-times with warm DPBS (Gibco, with Mg2+ and Ca2+, and adhered cells were exposed to exNef or exCont (1.7 × 109 particles/mL) for 48 h in the absence or presence of either 20 μM fluvastatin (Sigma) or 10 nM Picropodophyllin (PPP) in Dutch modified RPMI supplemented with 10% Human Serum (CeLLect), 1% Pen/Strep, 10 mM L-Glutamine and 10 mM pyruvate. To remove lipid rafts, cells were treated with or 1 mM methyl β-cyclodextrin for 30 min 24 h after EV treatment, then washed and incubated for the remaining 24 h with EVs. Cells were washed with warm PBS (with Mg2+ and Ca2+ and exposed to a fresh complete medium supplemented with M-CSF (20 ng/mL) for the next 6 days. At the end of differentiation, some cells were stimulated with 2 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS, InvivoGen) for 24 h.

Mice

All animal experiments were approved by the Alfred Medical Research Education Precinct (AMREP) animal ethics committee (P1761) and conducted in accordance with the Australian code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes, as stipulated by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Wild-type (C57BL/6J) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and colonies maintained by the AMREP animal facility. All mice were housed in a normal 12-h light/dark cycle and had ad libitum access to water and food. Mice were fed a normal chow diet and animals were being used in scientific experiments for the first time. Mice were randomly assigned to treatment groups and endpoint analysis was blinded.

Two groups (6 male mice per group, 8 weeks old) of C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories) were administered either exNef (2 μg total protein, I.V.) or control (exGFP) exosomes (2 mg total protein, I.V.), 3 times a week, for a period of 2 weeks as described previously.14 Animals weighed approximately 19–22 g. At the end of the experiment mice were euthanized, bone marrow cells were washed out from fibia and tibia, plated on Petri dishes, non-adherent cells were washed away while adherent cells (BMDM) were grown for 7 or 15 days in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 10% of L929 conditioned medium. Cells were stimulated with LPS (1 h, 100 ng/mL) and medium was collected for analysis of the amount of secreted TNFα by ELISA (Invitrogen).

In a separate experiment bone marrow from mice treated as above were transplanted into irradiated C57BL/6J mice (8 male mice per group, 10 weeks old) using a competitive transplantation design as described by us previously.79 The competitive transplantation design was chosen to investigate the possible effects of Nef on hematopoiesis (findings to be reported elsewhere) and did not affect outcomes of this study. Recipient mice were maintained for 11 week and weighed approximately 20–27 g. Twenty-four hours prior to termination, mice were injected with LPS (E. coli O111:B 1 4; Invivogen; 35 μg per mouse) to stimulate myelopoiesis. Mice were euthanized, bone marrow cells were washed out from fibia and tibia, plated on Petri dishes, non-adherent cells were washed away while adherent cells (BMDM) were grown for 9 days as described above. Cells were stimulated with LPS (4 h, 100 ng/mL) and medium was collected for analysis of the amount of secreted TNFα by ELISA (Invitrogen).

METHOD DETAILS

EV preparation

EVs were prepared from the supernatant of HEK293T cells transfected with Nef-expressing (exNef) or RFP-expressing (exCont) vectors as previously described.33 RFP- and Nef-expressing plasmids were a kind gift from Dr. Fackler.78 Briefly, 48 h post transfection with pcDNA3.1 vector expressing codon-optimized Nef80 (to make exNef) or RFP (to make exCont), medium was collected from cell cultures. Culture supernatants were preclarified by centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cells and cellular debris and were then clarified by spinning at 2,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove the remaining debris and large apoptotic bodies, and exosomes were pelleted by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 75 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in exosome-free medium at a concentration of 1.7 × 109 EV particles/mL (measured by NTA), corresponding to 44.4 pg/mL of Nef in exNef, and frozen at −70°C. Characterization and quantification of exosomes are illustrated in Figure S1.

Flow cytometry

Phenotypic analysis of monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) was performed using flow cytometric direct immunostaining. Cells were detached from the plastic with 10 mM EDTA in PBS by scraping. MDM were incubated with Live/Dead Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen) for 20 min on ice, washed with Blocking Buffer (BB, PBS/5% HS/0.0055% NaN3) and incubated in BB for 15 min on ice to exclude non-specific binding of Abs. After washing in BB, cells were stained in 100 μL of Brilliant Stain Buffer (BD Bioscience) with a mixture of mouse anti-human FITC-CD16, Pe-Cy5–CD11b/Mac-1, APC-H7–HLA-DR, BV421–CD38, BV480–CD14, BV786–CD80, APC–TLR4, BV650–CD40, Pe–CD64, Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit for 30 min on ice. Then cells were washed and incubated in 250 μL of Fixation/Permeabilization Solution for 20 min on ice, washed 2 times in 1 × BD Perm/Wash Buffer, resuspended in 50 μL of BD Perm/Wash Buffer with PerCP/Cy5.5–CD68 (BD Pharmingen), and incubated for 30 min on ice. MDM were washed and resuspended in 50 μL of Staining Buffer (PBS/1% HS/0.0055% NaN3) prior to analysis. Flow cytometry was performed on Cytek Aurora (spectral flow cytometry) using SpectroFlo software. SpectroFlo QC beads were used to optimize the cytometer. Unstained, single fluorochrome stained cells and BD CompBeads Compensation Particles (BD Bioscience) were used as Reference Controls to ensure accurate spectral unmixing of the data. Compensation was done in SpectroFlo software (Cytek Biosciences). The results were analyzed with FlowJo software version 10.7.1. The FMO (fluorescence minus one) controls were used for gating on positive cells. To analyze, visualize, and interpret data, equal amounts of MDM treated with exCont or exNef were subjected to t-SNE (t-stochastic neighbor embedding) analysis using iteration 1000, perplexity 45, gradient algorithm-Barnes-Hut. Unbiased number of clusters (populations) were determined by Phenograph technique and applied to FlowSom analysis to visualize cytometry data. Phenotypic outcome was considered in the populations where exNef-treated cells prevailed over exCont-treated for 10% or more.

RNA-seq

Differentiated MDM were washed in PBS and exposed to 2 ng/mL of LPS for 3 h, washed again and used for RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated and cleaned using RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen). The amount of isolated RNA was measured using Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen) and Qubit 4 Fluorometer. Library preparation from polyA RNA and sequencing was performed by GENEWIZ on Illumina HiSeq platform (2 × 150 bp configuration, single index, 50 million reads per sample).

The raw RNA-sequencing reads were QCed using FastQC, and aligned to the latest version of the human genome reference (GRCh38, Dec 2013) using STAR v.2.7.3.c in 2-pass mode with transcript annotations from the assembly GRCh38.79.81 The alignments were deduplicated, and then sorted using Samtools.82 Gene counts were estimated using the featureCounts utility of Sub-Read.83 The normalized gene counts were used for differential expression analysis by DeSeq2.84 Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) toolkit was used to identify pathways enriched in deregulated genes, and to perform leading edge analysis.

ddPCR

Total RNA isolated for RNA-seq was also subjected to reverse transcription-droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (RT-ddPCR) analysis. Total cDNA from each RNA sample was generated using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR (Bio-Rad). The amount of cDNA used in ddPCR was determined by a pilot experiment using β-actin primers and defined as the amount that will generate Ct value for β-actin approximately equal to 16. Real Time PCR was performed in duplicate using IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and CFX96 Real-Time System, Bio-Rad. Gene-specific PCR primer pairs were obtained from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD) and used according to company’s protocol. Droplet digital PCR was performed in quadruplicates with QX200 ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix and QXDx AutoDG Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad). Copy numbers of GAPDH transcripts were used for normalization.

ATAC-seq

ATAC-seq was performed using ATAC-seq Kit (Cell Biologics) according to the instruction manual. In brief: 50,000 cells were spun, washed in cold PBS and resuspended in cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630), centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at +4°C. Nuclei were suspended in transposition reaction mix (25 μL 2x TD buffer, 2.5 μL Transposome and 22.5 μL nuclease free H20), incubated at 37°C for 60 min and purified using Qiagen MinElute kit. Library was generated according to the instructions using the following PCR conditions: 98°C for 30 s; thermocycling 10 times: 98°C for 10 s, 63°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min; hold at 4°C. Library was purified using double-sided bead purification method and AMpure XP beads at RT. Library quality and quantity were assessed by qPCR method using NEB Next Library Quant Kit for Illumina and Qubit. Paired-end sequencing was performed by GENEWIZ on Illumina HiSeq platform (2 × 150 bp configuration, single index, with 50 million reads per sample).

All ATAC-seq sequencing datasets were quality assessed using FastQC, and aligned against the last version of the human reference genome (GRCh38) with bowtie285 using ‘—very-sensitive’ as parameters. The alignments were subsequently sorted using samtools.82 The sorted alignments were run though callpeak function of MACS286 to produce peak files. Differential analyses between exNef-treated cells and controls for the 1092 genes from the cholesterol metabolism, inflammation response and aerobic glycolysis pathway were performed using Hurdle model,87 and a threshold of 10% False Discovery Rate (FDR<0.1) were considered significant.

Cholesterol biosynthesis

Cells were plated in 24-well plates and incubated with exNef or exCont for 48 h, washed and incubated with [3H] acetate (final radioactivity of 3.7 MBq/mL) in serum-free medium supplemented with 0.1% BSA for 2 h. Cells were washed twice with PBS, collected in water, lipids were extracted and cholesterol isolated by TLC as described previously88 and counted in β-counter (Hidex).

Plasma membrane protein isolation

Plasma membrane proteins were isolated using the Minute™ kit from Invent Biotechnologies (Plymouth, MN) following manufacturer’s protocol. For lipid raft isolation, membrane fraction was isolated and subjected to centrifugation in Iodixanol density gradient as described previously.14,89 Fractions were collected from the top of the gradient (first fraction is the least dense fraction).

Western blotting

Samples were analyzed by automated Western immunoblotting using the JessTM Simple Western system (BioTechne, San Jose, CA). For analysis of Flotillin 1 and β actin, a 20–230 kDa Jess separation module SM-W004 was used. Plasma membrane (60 mg per sample) was homogenized in the Triton X-100 RIPA lysis buffer (250 μL, ThermoFisher) and cleared by centrifugation at 5,000 × g. Three μL of lysate (1 μg/μL protein) was mixed with 1 μL of Fluorescent 5X Master mix (Bio-Techne) in the presence of fluorescent molecular weight markers and 400 mM dithiothreitol (Bio-Techne). This preparation was denatured at 95°C for 5 min. Molecular weight ladder and proteins were separated in capillaries through a separation matrix at 375 volts. A Bio-Techne proprietary photoactivated capture chemistry was used to immobilize separated viral proteins on the capillaries. Capillaries with immobilized proteins were blocked with KPL Detection Block (5X) (SeraCare Life Sciences, Gaithersburg, MD) for 60 min, and then incubated with primary anti-human Flotillin 1 goat polyclonal antibody (Bio-Techne) or anti-hβ-actin mouse monoclonal antibody (R&D) for 60 min. After a wash step, HRP-conjugated anti-goat or near infrared (NIR) fluorescent dye-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody from Bio-Techne was added for 30 min to capillaries. The chemiluminescent revelation was established with peroxide/luminol-S (Bio-Techne). NIR imaging was obtained using Jess fluorescent detection channel. Digital image of chemiluminescence or fluorescence of the capillary was captured with Compass Simple Western software (version 5.1.0, Protein Simple) that calculated automatically heights (chemiluminescence or fluorescence intensity), area, and signal/noise ratio. Results were visualized as electropherograms representing peak of chemiluminescence or fluorescence intensity and as lane view from signal of chemiluminescence or fluorescence detected in the capillary. A total protein assay using Total Protein detection module DM-TP01 and Replex Module RP-001 was included in each run to quantitate loading. Samples were analyzed at least 2 times to ensure consistency of the results.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism version 9.4.1 from GraphPad. Details of specific experiments are provided in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| mouse monoclonal anti-human FITC-CD16 | BD Pharmingen | cat#560996 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-human Pe-Cy5–CD11b/Mac-1 | BD Pharmingen | cat#561686 |

| mouse anti-human APC-H7-HLA-DR | BD Pharmingen | cat#561358 |

| mouse anti-human BV421–CD38 | BD Horizon | cat#562445 |

| mouse anti-human BV480–CD14 | BD Horizon | cat#566190 |

| mouse anti-human BV786–CD80 | BD Horizon | cat#564159 |

| mouse anti-human APC–TLR4 | Abcam | cat#ab155343 |

| mouse anti-human BV650–CD40 | BioLegend | cat#334338; RRID: AB_2566209 |

| mouse anti-human Pe–CD64 | BioLegend | cat#305008; RRID: AB_314492 |

| goat polyclonal anti-human Flotillin 1 | Bio-Techne | cat#NB100-1043 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-human β-actin | R&D | cat#MAB8929 |

| donkey HRP-conjugated secondary anti-goat | Bio-Techne | cat#043-522 |

| NIR-conjugated secondary anti-mouse | Bio-Techne | cat#043-821 |

| Rabbit polyclonal to Flotillin 1 | Abcam | cat#41927; RRID: AB_941621 |

| Mouse monoclonal [AB.H10] to ABCA1 | Abcam | cat#18180; RRID: AB_444302 |

| Mouse monoclonal [464.6] to alpha 1 Sodium Potassium ATPase | Abcam | cat#7671; RRID: AB_306023 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E. coli strain for plasmid propagation | Zymo Research | cat#T3007 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Ficoll-Paque | Cytiva | cat#17544203 |

| RPMI 1640 Dutch Modified | Gibco | cat#22409-015 |

| DPBS | Gibco | cat#14040133 |

| PBS | Gibco | cat#10010023 |

| Human Serum | CeLLect, | cat#2830349 |

| Pen/Strep | Corning | cat#30-001-CI |

| L-Glutamine | Corning | cat#25-005-CI |

| Sodium pyruvate | Corning | cat#25-000-CI |

| M-CSF | Sigma | cat#SRP3110-10UG |

| LPS | Sigma | cat#L3024 |

| Fluvastatin | Sigma | cat#SML0038 |

| Picropodophyllin | SeleckChem | cat#S7668 |

| Methyl-beta-cyclodextrin | ThermoFisher | cat#J66847.14 |

| Live/Dead Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit | Invitrogen | cat#L34957 |

| Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit | BD Biosciences | cat#554714 |

| RNeasy Plus Mini Kit | Qiagen | cat#74134 |

| Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit | Invitrogen | cat#Q32852 |

| iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR | Bio-Rad | cat#1708841 |

| IQ SYBR Green Supermix | Bio-Rad | cat#1708880 |

| ATAC-seq Kit | Cell Biologics | cat#CB6936 |

| MinElute kit | Quigen | cat#28004 |

| Next Library Quant Kit for Illumina | NEB | cat#E7630 |

| Minute™ Plasma Membrane Protein Isolation and Cell Fractionation kit | Invent Biotechnologies | cat#SM-005 |

| Triton X-100 RIPA lysis buffer | ThermoFisher | cat#J62885 |

| KPL Detection Block | SeraCare Life Sciences | cat#5920-0004 |

| Total Protein Detection Module for Jess Assay | Bio-Techne | cat#DM-TP01 |

| Re-Plex Module | Bio-Techne | cat#RP-001 |

| [3H]Cholesterol | American Radiolabeled Chemicals | cat#ART 0255 |

| [3H]acetate | American Radiolabeled Chemicals | cat#ART 0202 |

| TLC Plates | Velocity Scientific Solutions | cat#VEL00215 |

| Chloroform | RCI Labscan | cat#BP1027E |

| Methanol | Chem-Supply | cat#UN1230 |

| Iodixanol | SigmaAldrich | cat#D1556 |

| LPS | SigmaAldrich | cat#L2654 |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer | BD Horizon | cat#659611 |

| Automated Droplet Generation Oil for EvaGreen | Bio-Rad | cat#1864112 |

| ddPCR Droplet Reader Oil | Bio-Rad | cat#1863004 |

| QX200 ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix | Bio-Rad | cat#1864034 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Mouse TNFα ELISA kit | Invitrogen | cat#88-7324-22 |

| Human TNFα ELISA kit | R&D | cat#DTA00D |

| Human IL6 ELISA kit | R&D | cat#D6050 |

| Separation Module (capillary cartridges, plates, buffers) | Bio-Techne | cat#SMW004 |

| Anti-mouse NIR detection module for Jess | Bio-Techne | cat#DM-009 |

| EZ standard pack (Biotinylated ladder; FL standard; DTT) | Bio-Techne | cat#PS-ST0 1EZ |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNA-seq and ATAC-seq | GEO | GSE214959 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HEK293T | ATCC | cat#CRL-3216 |

| BMDM | Isolated in the lab | N/A |

| MDM | Differentiated in the lab | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J mice | Jackson Laboratories | Strain 000664 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| HMGCR PCR primers | OriGene | cat#HP200799 |

| SQLE PCR primers | OriGene | cat#HP206708 |

| IGF1R PCR primers | OriGene | cat#HP200815 |

| MVK PCR primers | OriGene | cat#HP200411 |

| GAPDH PCR primers | OriGene | cat#HP205798 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pcDNA3.1-RFP | Dr. Fackler | Ref. Haller et al.,78 |

| pEGFP-C1 | Clontech | Discontinued |

| pcDNA3.1-Nef | Dr. Fackler | Ref. Haller et al.,78 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism version 9.4.1 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/updates |

| Sigma Plot 10.0 | Systat Software | No longer available |

| Compass for Simple Western | Compass | installed on Jess instrument |

Highlights.

ExNef-treated monocytes differentiate into MDM hyperresponsive to inflammation

Mice injected with exNef acquire long-lived pro-inflammatory memory in BMDMs

ExNef-induced training depends on glycolysis and cholesterol biosynthesis

Lipid rafts are essential for exNef-induced trained immunity

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Christophe Vanpoille for help with characterization of Nef EVs. We are grateful to Dr. D.G. Vassylyev (University of Alabama School of Medicine and Dentistry, Birmingham, AL, USA) for the kind gift of recombinant Nef and Thyroxine. This study was supported by NIH grants R01 HL140977 (M.F. and M.I.B.), R01 HL158305 (D.S. and M.I.B.), R21 AI172028 (M.I.B.), and P30 AI117970 (M.I.B.).

INCLUSION AND DIVERSITY

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111674.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tseng A, Seet J, and Phillips EJ (2015). The evolution of three decades of antiretroviral therapy: challenges, triumphs and the promise of the future. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 79, 182–194. 10.1111/bcp.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lerner AM, Eisinger RW, and Fauci AS (2020). Comorbidities in persons with HIV: the lingering challenge. JAMA 323, 19–20. 10.1001/jama.2019.19775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hileman CO, and Funderburg NT (2017). Inflammation, immune activation, and antiretroviral therapy in HIV. Curr. HIV AIDS Rep 14, 93–100. 10.1007/s11904-017-0356-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lederman MM, Funderburg NT, Sekaly RP, Klatt NR, and Hunt PW (2013). Residual immune dysregulation syndrome in treated HIV infection. Adv. Immunol 119, 51–83. 10.1016/B978-0-12-407707-2.00002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zicari S, Sessa L, Cotugno N, Ruggiero A, Morrocchi E, Concato C, Rocca S, Zangari P, Manno EC, and Palma P (2019). Immune activation, inflammation, and non-AIDS Co-morbidities in HIV-infected patients under long-term ART. Viruses 11, 200. 10.3390/v11030200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nazli A, Chan O, Dobson-Belaire WN, Ouellet M, Tremblay MJ, Gray-Owen SD, Arsenault AL, and Kaushic C (2010). Exposure to HIV-1 directly impairs mucosal epithelial barrier integrity allowing microbial translocation. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000852. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raymond AD, Lang MJ, Chu J, Campbell-Sims T, Khan M, Bond VC, Pollard RB, Asmuth DM, and Powell MD (2019). Plasma-derived HIV Nef+ exosomes persist in ACTG384 study participants despite successful virological suppression. Preprint at bioRxiv. 10.1101/708719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson EM, Ward AR, Truong R, Thomas AS, Huang SH, Dilling TR, Terry S, Bui JK, Mota TM, Danesh A, et al. (2021). HIV-specific T cell responses reflect substantive in vivo interactions with antigen despite long-term therapy. JCI Insight 6, 142640. 10.1172/jci.insight.142640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNamara RP, Costantini LM, Myers TA, Schouest B, Maness NJ, Griffith JD, Damania BA, MacLean AG, and Dittmer DP (2018). Nef secretion into extracellular vesicles or exosomes is conserved across Human and Simian Immunodeficiency Viruses. mBio 9, 023444–17. 10.1128/mBio.02344-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pužar DominkuŠ P, Ferdin J, Plemenitaš A, Peterlin BM, and Lenassi M (2017). Nef is secreted in exosomes from Nef.GFP-expressing and HIV-1-infected human astrocytes. J. Neurovirol 23, 713–724. 10.1007/s13365-017-0552-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellwanger JH, Veit TD, and Chies JAB (2017). Exosomes in HIV infection: a review and critical look. Infect. Genet. Evol 53, 146–154. 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenassi M, Cagney G, Liao M, Vaupotic T, Bartholomeeusen K, Cheng Y, Krogan NJ, Plemenitas A, and Peterlin BM (2010). HIV Nef is secreted in exosomes and triggers apoptosis in bystander CD4+ T cells. Traffic 11, 110–122. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell TD, Khan M, Huang MB, Bond VC, and Powell MD (2008). HIV-1 Nef protein is secreted into vesicles that can fuse with target cells and virions. Ethn. Dis 18, S2–S19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukhamedova N, Hoang A, Dragoljevic D, Dubrovsky L, Pushkarsky T, Low H, Ditiatkovski M, Fu Y, Ohkawa R, Meikle PJ, et al. (2019). Exosomes containing HIV protein Nef reorganize lipid rafts potentiating inflammatory response in bystander cells. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1007907. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crişan TO, Netea MG, and Joosten LAB (2016). Innate immune memory: implications for host responses to damage-associated molecular patterns. Eur. J. Immunol 46, 817–828. 10.1002/eji.201545497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quintin J, Cheng SC, van der Meer JWM, and Netea MG (2014). Innate immune memory: towards a better understanding of host defense mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Immunol 29, 1–7. 10.1016/j.coi.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Netea MG, Quintin J, and van der Meer JWM (2011). Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe 9, 355–361. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garly ML, Martins CL, Balé C, Baldé MA, Hedegaard KL, Gustafson P, Lisse IM, Whittle HC, and Aaby P (2003). BCG scar and positive tuberculin reaction associated with reduced child mortality in West Africa. A non-specific beneficial effect of BCG? Vaccine 21, 2782–2790. 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinstein RS, Weinstein MM, Alibek K, Bukrinsky MI, and Brichacek B (2010). Significantly reduced CCR5-tropic HIV-1 replication in vitro in cells from subjects previously immunized with Vaccinia Virus. BMC Immunol. 11, 23. 10.1186/1471-2172-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bree LCJ, Koeken VACM, Joosten LAB, Aaby P, Benn CS, van Crevel R, and Netea MG (2018). Non-specific effects of vaccines: current evidence and potential implications. Semin. Immunol 39, 35–43. 10.1016/j.smim.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Heijden CDCC, Noz MP, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, Riksen NP, and Keating ST (2018). Epigenetics and trained immunity. Antioxid. Redox Signal 29, 1023–1040. 10.1089/ars.2017.7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bekkering S, Quintin J, Joosten LAB, van der Meer JWM, Netea MG, and Riksen NP (2014). Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 34, 1731–1738. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geng S, Chen K, Yuan R, Peng L, Maitra U, Diao N, Chen C, Zhang Y, Hu Y, Qi CF, et al. (2016). The persistence of low-grade inflammatory monocytes contributes to aggravated atherosclerosis. Nat. Commun 7, 13436. 10.1038/ncomms13436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Valk FM, Bekkering S, Kroon J, Yeang C, Van den Bossche J, van Buul JD, Ravandi A, Nederveen AJ, Verberne HJ, Scipione C, et al. (2016). Oxidized phospholipids on lipoprotein(a) elicit arterial wall inflammation and an inflammatory monocyte response in humans. Circulation 134, 611–624. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.020838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Heijden CDCC, Keating ST, Groh L, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, and Riksen NP (2020). Aldosterone induces trained immunity: the role of fatty acid synthesis. Cardiovasc. Res 116, 317–328. 10.1093/cvr/cvz137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neidhart M, Pajak A, Laskari K, Riksen NP, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, Lutgens E, Stroes ESG, Ciurea A, Distler O, et al. (2019). Oligomeric S100A4 is associated with monocyte innate immune memory and bypass of tolerance to subsequent stimulation with lipopolysaccharides. Front. Immunol 10, 791. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riksen NP, and Netea MG (2021). Immunometabolic control of trained immunity. Mol. Aspects Med 77, 100897. 10.1016/j.mam.2020.100897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deacon NJ, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker DJ, McPhee DA, Greenway AL, Ellett A, Chatfield C, et al. (1995). Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science 270, 988–991. 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanna Z, Kay DG, Rebai N, Guimond A, Jothy S, and Jolicoeur P (1998). Nef harbors a major determinant of pathogenicity for an AIDS-like disease induced by HIV-1 in transgenic mice. Cell 95, 163–175. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81748-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kestler HW III, Ringler DJ, Mori K, Panicali DL, Sehgal PK, Daniel MD, and Desrosiers RC (1991). Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell 65, 651–662. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchhoff F, Greenough TC, Brettler DB, Sullivan JL, and Desrosiers RC (1995). Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med 332, 228–232. 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bekkering S, Blok BA, Joosten LAB, Riksen NP, van Crevel R, and Netea MG (2016). In vitro experimental model of trained innate immunity in human primary monocytes. Clin. Vaccine Immunol 23, 926–933. 10.1128/CVI.00349-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubrovsky L, Ward A, Choi SH, Pushkarsky T, Brichacek B, Vanpouille C, Adzhubei AA, Mukhamedova N, Sviridov D, Margolis L, et al. (2020). Inhibition of HIV replication by apolipoprotein A-I binding protein targeting the lipid rafts. mBio 11, 029566–19. 10.1128/mBio.02956-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, and Mesirov JP (2005). Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishimura D (2001). BioCarta. Biotech Software & Internet Report, 2 (Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.), pp. 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferdin J, Goričcar K, Dolžan V, Plemenitaš A, Martin JN, Peterlin BM, Deeks SG, and Lenassi M (2018). Viral protein Nef is detected in plasma of half of HIV-infected adults with undetectable plasma HIV RNA. PLoS One 13, e0191613. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexander M, Bor YC, Ravichandran KS, Hammarskjöld ML, and Rekosh D (2004). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef associates with lipid rafts to downmodulate cell surface CD4 and class I major histocompatibility complex expression and to increase viral infectivity. J. Virol 78, 1685–1696. 10.1128/jvi.78.4.1685-1696.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrager JA, and Marsh JW (1999). HIV-1 Nef increases T cell activation in a stimulus-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8167–8172. 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mujawar Z, Tamehiro N, Grant A, Sviridov D, Bukrinsky M, and Fitzgerald ML (2010). Mutation of the ATP cassette binding transporter A1 (ABCA1) C-terminus disrupts HIV-1 Nef binding but does not block the Nef enhancement of ABCA1 protein degradation. Biochemistry 49, 8338–8349. 10.1021/bi100466q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fenard D, Yonemoto W, de Noronha C, Cavrois M, Williams SA, and Greene WC (2005). Nef is physically recruited into the immunological synapse and potentiates T cell activation early after TCR engagement. J. Immunol 175, 6050–6057. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poe JA, and Smithgall TE (2009). HIV-1 Nef dimerization is required for Nef-mediated receptor downregulation and viral replication. J. Mol. Biol 394, 329–342. 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mangino G, Percario ZA, Fiorucci G, Vaccari G, Acconcia F, Chiarabelli C, Leone S, Noto A, Horenkamp FA, Manrique S, et al. (2011). HIV-1 Nef induces proinflammatory state in macrophages through its acidic cluster domain: involvement of TNF alpha receptor associated factor 2. PLoS One 6, e22982. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bekkering S, Domínguez-Andrés J, Joosten LAB, Riksen NP, and Netea MG (2021). Trained immunity: reprogramming innate immunity in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol 39, 667–693. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-102119-073855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atri C, Guerfali FZ, and Laouini D (2018). Role of human macrophage polarization in inflammation during infectious diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci 19, E1801. 10.3390/ijms19061801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapellos TS, Bonaguro L, Gemünd I, Reusch N, Saglam A, Hinkley ER, and Schultze JL (2019). Human monocyte subsets and phenotypes in major chronic inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol 10, 2035. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gui T, Shimokado A, Sun Y, Akasaka T, and Muragaki Y (2012). Diverse roles of macrophages in atherosclerosis: from inflammatory biology to biomarker discovery. Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 693083. 10.1155/2012/693083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fanucchi S, Domínguez-Andrés J, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, and Mhlanga MM (2021). The intersection of epigenetics and metabolism in trained immunity. Immunity 54, 32–43. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bekkering S, Arts RJW, Novakovic B, Kourtzelis I, van der Heijden CDCC, Li Y, Popa CD, Ter Horst R, van Tuijl J, Netea-Maier RT, et al. (2018). Metabolic induction of trained immunity through the mevalonate pathway. Cell 172, 135–146.e9. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humeres C, Venugopal H, and Frangogiannis NG (2022). Smad-dependent pathways in the infarcted and failing heart. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 64, 102207. 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grumati P, Morozzi G, Hölper S, Mari M, Harwardt MLI, Yan R, Müller S, Reggiori F, Heilemann M, and Dikic I (2017). Full length RTN3 regulates turnover of tubular endoplasmic reticulum via selective autophagy. Elife 6, e25555. 10.7554/eLife.25555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nayagam JS, Williamson C, Joshi D, and Thompson RJ (2020). Review article: liver disease in adults with variants in the cholestasis-related genes ABCB11, ABCB4 and ATP8B1. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther 52, 1628–1639. 10.1111/apt.16118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bartel A, Göhler A, Hopf V, and Breitbach K (2017). Caspase-6 mediates resistance against Burkholderia pseudomallei infection and influences the expression of detrimental cytokines. PLoS One 12, e0180203. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berta T, Lee JE, and Park CK (2017). Unconventional role of caspase-6 in spinal microglia activation and chronic pain. Mediators Inflamm. 2017, 9383184. 10.1155/2017/9383184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lorè NI, Bragonzi A, and Cigana C (2016). The IL-17A/IL-17RA axis in pulmonary defence and immunopathology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 30, 19–27. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng B, Gao YH, Xie JQ, He XW, Wang CC, Xu JF, and Zhang GJ (2022). Clinical and genetic spectrum of primary ciliary dyskinesia in Chinese patients: a systematic review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 17, 283. 10.1186/s13023-022-02427-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ershov P, Kaluzhskiy L, Mezentsev Y, Yablokov E, Gnedenko O, and Ivanov A (2021). Enzymes in the cholesterol synthesis pathway: interactomics in the cancer context. Biomedicines 9, 895. 10.3390/biomedicines9080895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandez-Ruiz I, Puchalska P, Narasimhulu CA, Sengupta B, and Parthasarathy S (2016). Differential lipid metabolism in monocytes and macrophages: influence of cholesterol loading. J. Lipid Res 57, 574–586. 10.1194/jlr.M062752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van ’t Wout AB, Swain JV, Schindler M, Rao U, Pathmajeyan MS, Mullins JI, and Kirchhoff F (2005). Nef induces multiple genes involved in cholesterol synthesis and uptake in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected T cells. J. Virol 79, 10053–10058. 10.1128/JVI.79.15.10053-10058.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huo H, Guo X, Hong S, Jiang M, Liu X, and Liao K (2003). Lipid rafts/caveolae are essential for insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling during 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation induction. J. Biol. Chem 278, 11561–11569. 10.1074/jbc.M211785200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hong S, Huo H, Xu J, and Liao K (2004). Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation requires lipid rafts but not caveolae. Cell Death Differ. 11, 714–723. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Romanelli RJ, Mahajan KR, Fulmer CG, and Wood TL (2009). Insulin-like growth factor-I-stimulated Akt phosphorylation and oligodendrocyte progenitor cell survival require cholesterol-enriched membranes. J. Neurosci. Res 87, 3369–3377. 10.1002/jnr.22099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sural-Fehr T, Singh H, Cantuti-Catelvetri L, Zhu H, Marshall MS, Rebiai R, Jastrzebski MJ, Givogri MI, Rasenick MM, and Bongarzone ER (2019). Inhibition of the IGF-1-PI3K-Akt-mTORC2 pathway in lipid rafts increases neuronal vulnerability in a genetic lysosomal glycosphingolipidosis. Dis. Model. Mech 12, dmm036590. 10.1242/dmm.036590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Delle Bovi RJ, Kim J, Suresh P, London E, and Miller WT (2019). Sterol structure dependence of insulin receptor and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Biomembr 1861, 819–826. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Federico M, Percario Z, Olivetta E, Fiorucci G, Muratori C, Micheli A, Romeo G, and Affabris E(2001). HIV-1 Nef activates STAT1 in human monocytes/macrophages through the release of soluble factors. Blood 98, 2752–2761. 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mangino G, Serra V, Borghi P, Percario ZA, Horenkamp FA, Geyer M, and Affabris E (2012). Exogenous nef induces proinflammatory signaling events in murine macrophages. Viral Immunol. 25, 117–130. 10.1089/vim.2011.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Percario Z, Olivetta E, Fiorucci G, Mangino G, Peretti S, Romeo G, Affabris E, and Federico M (2003). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Nef activates STAT3 in primary human monocyte/macrophages through the release of soluble factors: involvement of Nef domains interacting with the cell endocytotic machinery. J. Leukoc. Biol 74, 821–832. 10.1189/jlb.0403161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tangsinmankong N, Day NK, Good RA, and Haraguchi S (2000). Monocytes are target cells for IL-10 induction by HIV-1 Nef protein. Cytokine 12, 1506–1511. 10.1006/cyto.2000.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Varin A, Manna SK, Quivy V, Decrion AZ, Van Lint C, Herbein G, and Aggarwal BB (2003). Exogenous Nef protein activates NF-kappa B, AP-1, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase and stimulates HIV transcription in promonocytic cells. Role in AIDS pathogenesis. J. Biol. Chem 278, 2219–2227. 10.1074/jbc.M209622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quintin J, Saeed S, Martens JHA, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Ifrim DC, Logie C, Jacobs L, Jansen T, Kullberg BJ, Wijmenga C, et al. (2012). Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe 12, 223–232. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Netea MG, Domínguez-Andrés J, Barreiro LB, Chavakis T, Divangahi M, Fuchs E, Joosten LAB, van der Meer JWM, Mhlanga MM, Mulder WJM, et al. (2020). Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol 20, 375–388. 10.1038/s41577-020-0285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hamilton TA, Zhao C, Pavicic PG Jr., and Datta S (2014). Myeloid colony-stimulating factors as regulators of macrophage polarization. Front. Immunol 5, 554. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Novakovic B, Habibi E, Wang SY, Arts RJW, Davar R, Megchelenbrink W, Kim B, Kuznetsova T, Kox M, Zwaag J, et al. (2016). Beta-glucan reverses the epigenetic state of LPS-induced immunological tolerance. Cell 167, 1354–1368.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tincati C, Douek DC, and Marchetti G (2016). Gut barrier structure, mucosal immunity and intestinal microbiota in the pathogenesis and treatment of HIV infection. AIDS Res. Ther 13, 19. 10.1186/s12981-016-0103-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heron SE, and Elahi S (2017). HIV infection and compromised mucosal immunity: oral manifestations and systemic inflammation. Front. Immunol 8, 241. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Katzmarski N, Domínguez-Andrés J, Cirovic B, Renieris G, Ciarlo E, Le Roy D, Lepikhov K, Kattler K, Gasparoni G, Händler K, et al. (2022). Reply to: ’Lack of evidence for intergenerational inheritance of immune resistance to infections’. Nat. Immunol 23, 208–209. 10.1038/s41590-021-01103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Katzmarski N, Domínguez-Andrés J, Cirovic B, Renieris G, Ciarlo E, Le Roy D, Lepikhov K, Kattler K, Gasparoni G, Händler K, et al. (2021). Transmission of trained immunity and heterologous resistance to infections across generations. Nat. Immunol 22, 1382–1390. 10.1038/s41590-021-01052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sviridov D, Miller YI, and Bukrinsky MI (2022). Trained immunity and HIV infection. Front. Immunol 13, 903884. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.903884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haller C, Rauch S, Michel N, Hannemann S, Lehmann MJ, Keppler OT, and Fackler OT (2006). The HIV-1 pathogenicity factor nef interferes with maturation of stimulatory T-lymphocyte contacts by modulation of N-wasp activity. J. Biol. Chem 281, 19618–19630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dragoljevic D, Kraakman MJ, Nagareddy PR, Ngo D, Shihata W, Kammoun HL, Whillas A, Lee MKS, Al-Sharea A, Pernes G, et al. (2018). Defective cholesterol metabolism in haematopoietic stem cells promotes monocyte-driven atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur. Heart J 39, 2158–2167. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gao F, Li Y, Decker JM, Peyerl FW, Bibollet-Ruche F, Rodenburg CM, Chen Y, Shaw DR, Allen S, Musonda R, et al. (2003). Codon usage optimization of HIV type 1 subtype C gag, pol, env, and nef genes: in vitro expression and immune responses in DNA-vaccinated mice. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 19, 817–823. 10.1089/088922203769232610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, and Durbin R; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liao Y, Smyth GK, and Shi W (2013). The Subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e108. 10.1093/nar/gkt214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Love MI, Huber W, and Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Langmead B, and Salzberg SL (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Feng J, Liu T, and Zhang Y (2011). Using MACS to identify peaks from ChIP-seq data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 2, Unit.2.14. 10.1002/0471250953.bi0214s34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cragg JG (1971). Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica 39, 829–844. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fu Y, Hoang A, Escher G, Parton RG, Krozowski Z, and Sviridov D (2004). Expression of caveolin-1 enhances cholesterol efflux in hepatic cells. J. Biol. Chem 279, 14140–14146. 10.1074/jbc.M311061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mukhamedova N, Huynh K, Low H, Meikle PJ, and Sviridov D (2020). Isolation of lipid rafts from cultured mammalian cells and their lipidomics analysis. Bio. Protoc 10, e3670. 10.21769/Bio-Protoc.3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequencing datasets generated or analyzed during this study are deposited in GEO: GSE214959. The other data will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.