Abstract

Evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines (EBNPGs) inform registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) care for patients with chronic kidney disease grade 5 treated by dialysis; however, there has been little evaluation of best practices for implementing EBNPGs. In this effectiveness-implementation hybrid study with a quasi-experimental design, United States RDNs in hemodialysis clinics will document initial and follow-up nutrition care for patients with chronic kidney disease grade 5 treated by dialysis using the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Health Informatics Infrastructure before and after being randomly assigned to a training model: (1) EBNPG knowledge training or (2) EBNPG knowledge training plus an implementation toolkit. The aims of the study include examining congruence of RDN documentation of nutrition care with the EBNPG; describing common RDN-reported EBNPG acceptability, adoption, and adaptation issues; and determining the feasibility of estimating the impact of RDN care on nutrition-related patient outcomes. The AUGmeNt study can inform effective development and implementation of future EBNPGs.

Keywords: Chronic kidney diseases, medical nutrition therapy, implementation science, clinical practice guideline, nutrition care process terminology, dietitian

Introduction and Purpose

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is one of the leading causes of death in the United States, impacting the lives of 37 million adults.1,2 CKD grade 5 with kidney replacement therapy via dialysis3 (CKD G5D) affects approximately 720,000 people in the United States4 and causes high mortality rates, especially for patients aged 65 years and older.5

Registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) play an integral role in the multidisciplinary team treating individuals on dialysis, helping to minimize complications and improve patient outcomes by preventing and treating protein-energy wasting, mineral and electrolyte disorders, and other metabolic comorbidities associated with CKD.6,7 RDNs provide medical nutrition therapy based on the four-step nutrition care process (NCP)—assessment, diagnosis, intervention, and monitoring/evaluation.8,9 To guide RDN practice within the NCP framework, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ (Academy) Evidence Analysis Center publishes evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines (EBNPGs). EBNPGs are structured as per the NCP and developed based on systematic reviews.10,11 Through a collaboration between the Academy and the National Kidney Foundation (NKF), the EBNPG for CKD was recently updated to provide comprehensive, evidence-based guidance for the nutrition care of patients with CKD.6,7

The development of EBNPGs based on systematic reviews represents a substantial investment of time and resources by the Academy11 and NKF, and the impact of that investment is not realized unless the EBNPGs are effectively implemented by RDNs. There are many reasons why RDNs may not implement EBNPGs, including lack of knowledge of the content and lack of implementation resources and strategies.12 Factors at patient, provider, clinic, or company levels can affect guideline implementation.13 Although some studies have evaluated strategies to support the implementation of clinical practice guidelines,14,15 they focused on guidelines for other health care providers, such as physicians and nurses. There is an evidence gap related to implementation of guidelines specific for nutrition care (i.e., EBNPGs), and a greater understanding of EBNPG implementation could enhance care, improve patient outcomes, and reduce health care costs.16 Thus, the Academy conducts research to (a) identify optimal training models for EBNPGs, (b) understand barriers and facilitators of EBNPG implementation, and (c) assess the impact of EBNPGs on provider practice and nutrition-related outcomes.

The Assessing Uptake and Impact of Guidelines for Clinical Practice in Renal Nutrition (AUGmeNt) study is a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study17 with a quasi-experimental design18 conducted with U.S. RDNs providing nutrition care to individuals receiving outpatient maintenance hemodialysis (in-facility). The primary implementation aim of the study is to measure congruence of RDNs’ NCP documentation into the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Health Informatics Infrastructure (ANDHII) with nutrition care outlined in five selected recommendations from the EBNPG. A secondary implementation aim is to describe common RDN-reported acceptability, adoption, and adaptation issues with the EBNPG. Finally, an exploratory effectiveness aim is to determine the feasibility of estimating the impact of RDN care that is congruent with the EBNPG on nutrition-related outcomes for patients on hemodialysis. This protocol article is being published to increase accountability and transparency (i.e., reduce selective reporting of results) and provide more details on methodology and rationale as implementation science is an emerging area in nutrition research.19,20

Methods

Study Design

The AUGmeNt study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05032417) is a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study, in that there are a priori plans to test an EBNPG implementation strategy and examine the clinical effectiveness of care congruent with EBNPGs.17 Implementation and effectiveness aims will be assessed using a quasi-experimental design.18 RDNs will document initial and follow-up nutrition care for a randomly selected subset of their patients for 3 months, and then, they will be randomly assigned to one of two EBNPG training models (a knowledge-focused training or a comprehensive training). RDNs will then document initial and follow-up nutrition care for a different randomly selected subset of their patients for 3 months. Additional information about RDN and clinic characteristics, changes in RDN knowledge, and RDN experience with EBNPG implementation will be collected via an RDN survey. The study began in February 2021 and is expected to be completed by Fall 2022.

Funding Support and Ethical Approval

This project is supported by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation through grants from the Academy’s Renal Dietitians Practice Group and Relypsa, a Vifor Pharma Group Company. The study protocol was approved by the University of New Mexico Health Science Center’s (UNM HSC) Human Research Protections Office (HRPO #19–156). All hemodialysis clinic sites will defer to the UNM HSC HRPO via an institutional review board authorization agreement or a letter of support deferring oversight to the UNM HSC HRPO. Deidentified patient nutrition care information is collected into the ANDHII registry based on guidance from the Office for Human Research Protections Guidance on Research Involving Coded Private Information or Specimens.21 To meet the standards for registry research, the protocol ensures the identities of the individuals whose data are collected are protected from disclosure to the investigators, and clinical data are not obtained through research interventions or interactions with patients. RDNs will review a consent document before voluntarily agreeing to complete study surveys.

Development of EBNPG Training Models

The knowledge-focused training includes didactic information about the content of the EBNPG related to nutrition care for individuals on dialysis. This training contains information that is typically shared with RDNs when an EBNPG is released and, in this instance, includes a free webinar developed by the Academy and NKF that provides an overview of EBNPGs, as well as a presentation of the specific EBNPG developed by the Academy.

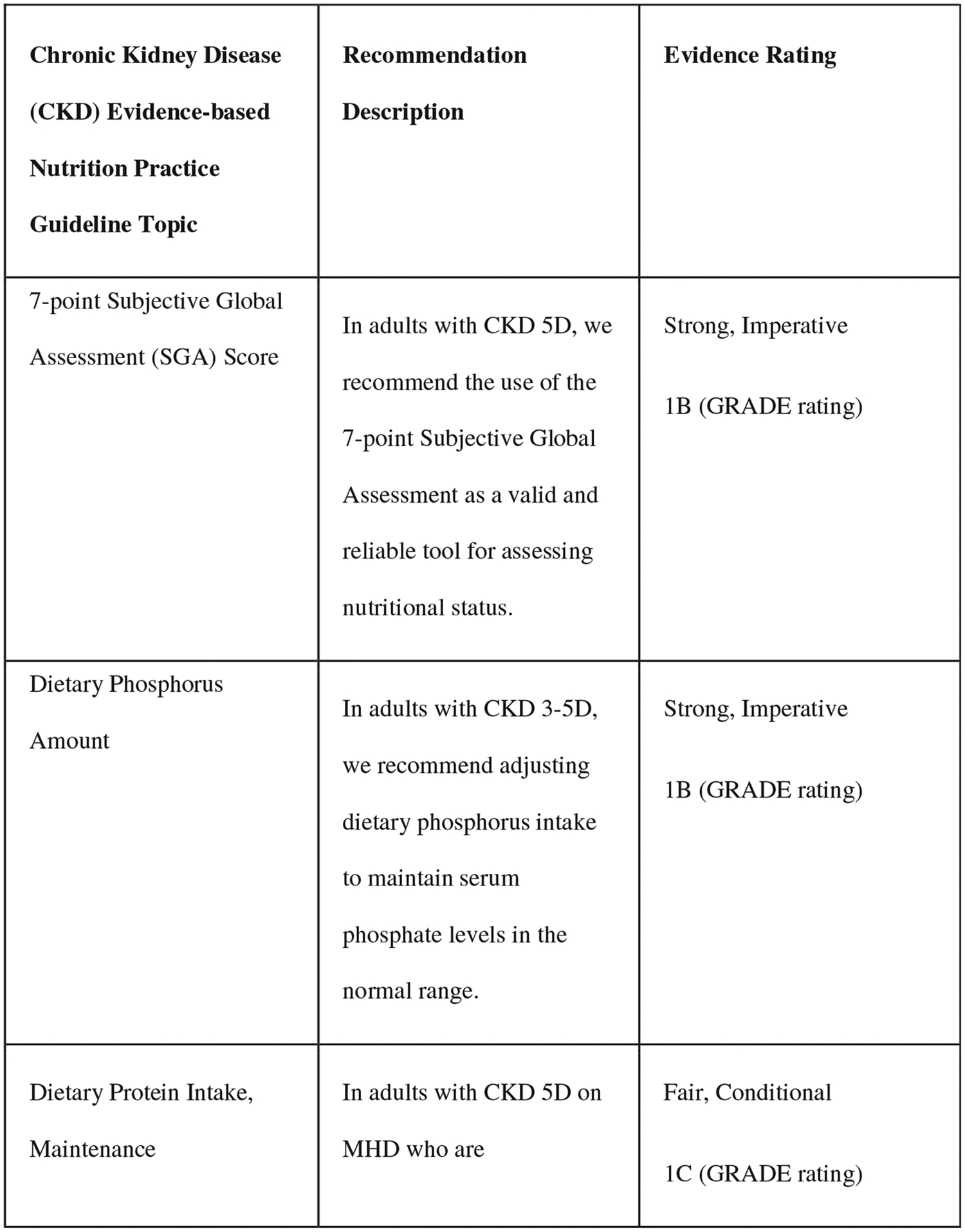

The comprehensive training includes the knowledge-focused training, plus access to the EBNPG virtual implementation toolkit. Because of the depth and breadth of the CKD EBNPG, which includes over 70 recommendations, consensus building discussions were conducted with key stakeholders, such as leadership from national dialysis companies and the Evidence Analysis Center guideline developers, to select five recommendations for patients on dialysis as the primary implementation focus for this project (Fig. 1). Several criteria were used to select the recommendations that were included, with preference being given to recommendations that (1) changed substantially from those in previous kidney nutrition guidelines (2010 CKD EBNPGs or the 2000 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative [KDOQI] guidelines),22,23 meaning that implementation efforts would likely be required, (2) included clear action statements for the RDN, and (3) were supported by strong evidence. An expert advisory group, consisting of renal nutrition researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates, reviewed the selected five CKD G5D recommendations and completed a formative survey to identify potential barriers and facilitators to implementation at several levels (patient, RDN, medical provider, clinic, and company). Identified barriers varied by recommendation and included the following: RDN knowledge gap, time, and buy-in; patient knowledge gap, time, buy-in, finances, and insurance coverage; electronic health record setup; medical provider buy-in; existing clinical protocols; and administrative support. The survey results and additional input from the advisory group were used to compile a list of potential barriers, and of facilitators to overcome those barriers, for each of the five selected recommendations.24

Figure 1.

Selected recommendations from the chronic kidney disease (2020) evidence-based nutrition practice guideline.6,7

This formative work was used to develop an implementation toolkit, including a virtual, asynchronous training on implementation science and quality improvement principles, a recommendation-specific resource list, and peer support. The primary objectives of the implementation science and quality improvement training are to provide the comprehensive training group with increased understanding of the complexity of their work environment, strategies to build buy-in from leadership and stakeholders, strategies to encourage operationalization of recommendations in daily practice, and methods to monitor and revise their implementation approaches. The implementation strategies were adapted from the normalization process theory,25 which is an action theory that focuses on what people do, rather than beliefs and attitudes, and from quality improvement resources developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.26 The implementation training concludes with a case study demonstrating the implementation of one CKD recommendation by an RDN. A final component of the implementation toolkit is an online community portal to facilitate ongoing peer-to-peer and RDN-to-research team discussion of implementation strategies.

Study Site and RDN Eligibility and Recruitment

This study will include RDNs from outpatient hemodialysis clinics across the United States. Eligible RDNs must be (1) licensed to provide care to patients at the hemodialysis facilities, (2) working at a hemodialysis clinic at least 20 hours per week, and (3) able and willing to complete all study training sessions and data collection. Eligible RDNs may work at multiple clinic sites. Only one RDN will be included per clinic site. RDNs are being recruited through national dialysis health care providers.

Study Procedures

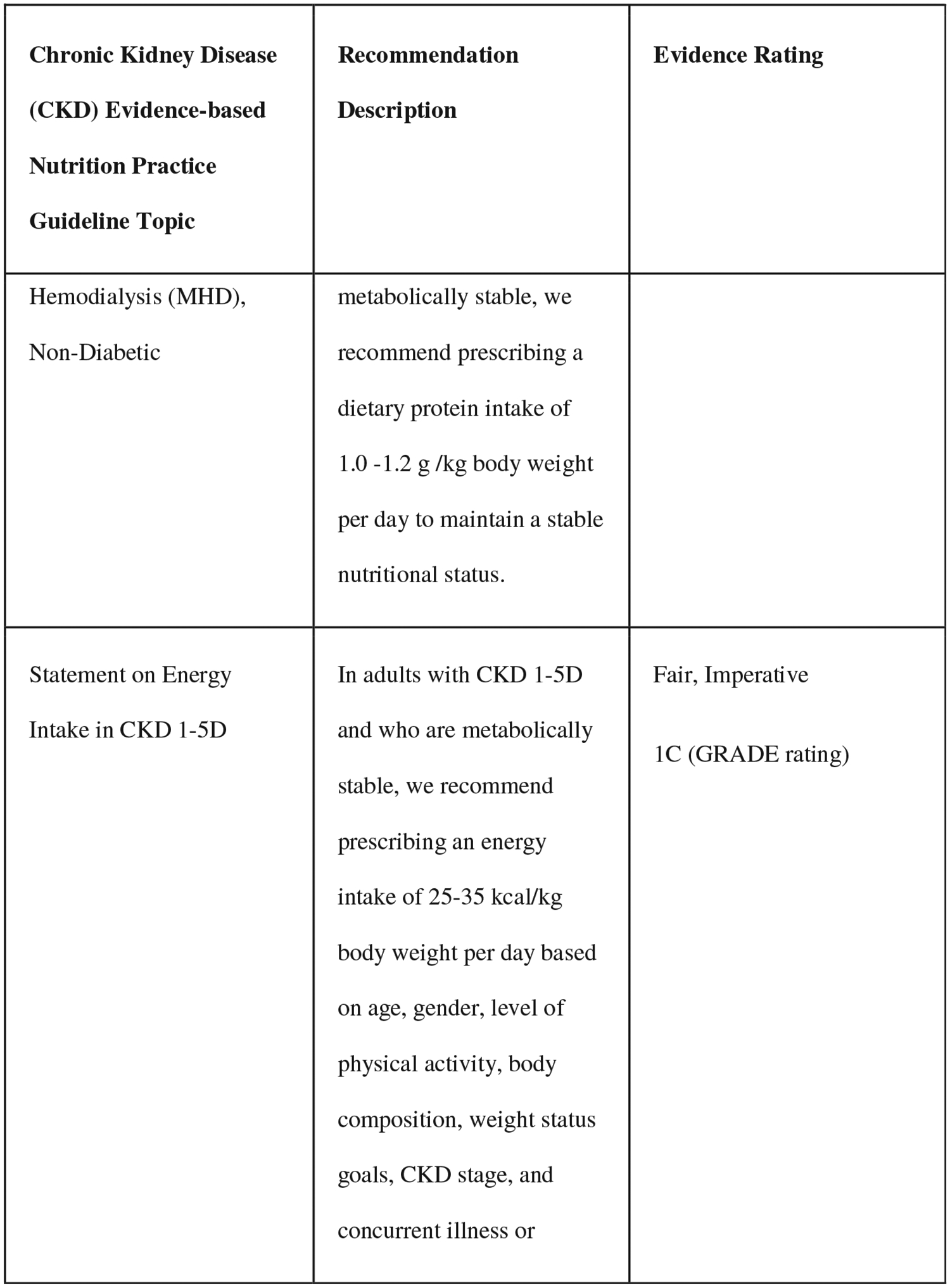

Study procedures will occur in four phases (Fig. 2). In phase 1, before the start of data collection, RDNs will receive virtual training on the use and application of key Academy research tools for the study, including the Nutrition Care Process and Terminology (NCP/T),27 Evidence Analysis Library,11 and the ANDHII.28 ANDHII infrastructure facilitates collection of nutrition care documentation using the NCP/T. RDNs select the appropriate NCPT from a dropdown list to document their activities for each section of the NCP (assessment, intervention, diagnosis, and monitoring/evaluation).

Figure 2.

The Assessing Uptake and Impact of Guidelines for Clinical Practice in Renal Nutrition (AUGmeNt) study design. NCP/T27, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Nutrition Care Process/Terminology; EAL11, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Evidence Analysis Library; ANDHII28, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Health Informatics Infrastructure; RDN, registered dietitian nutritionist; CKDG5D3, chronic kidney disease grade 5 treated by dialysis; EBNPG, evidence-based nutrition practice guideline.11

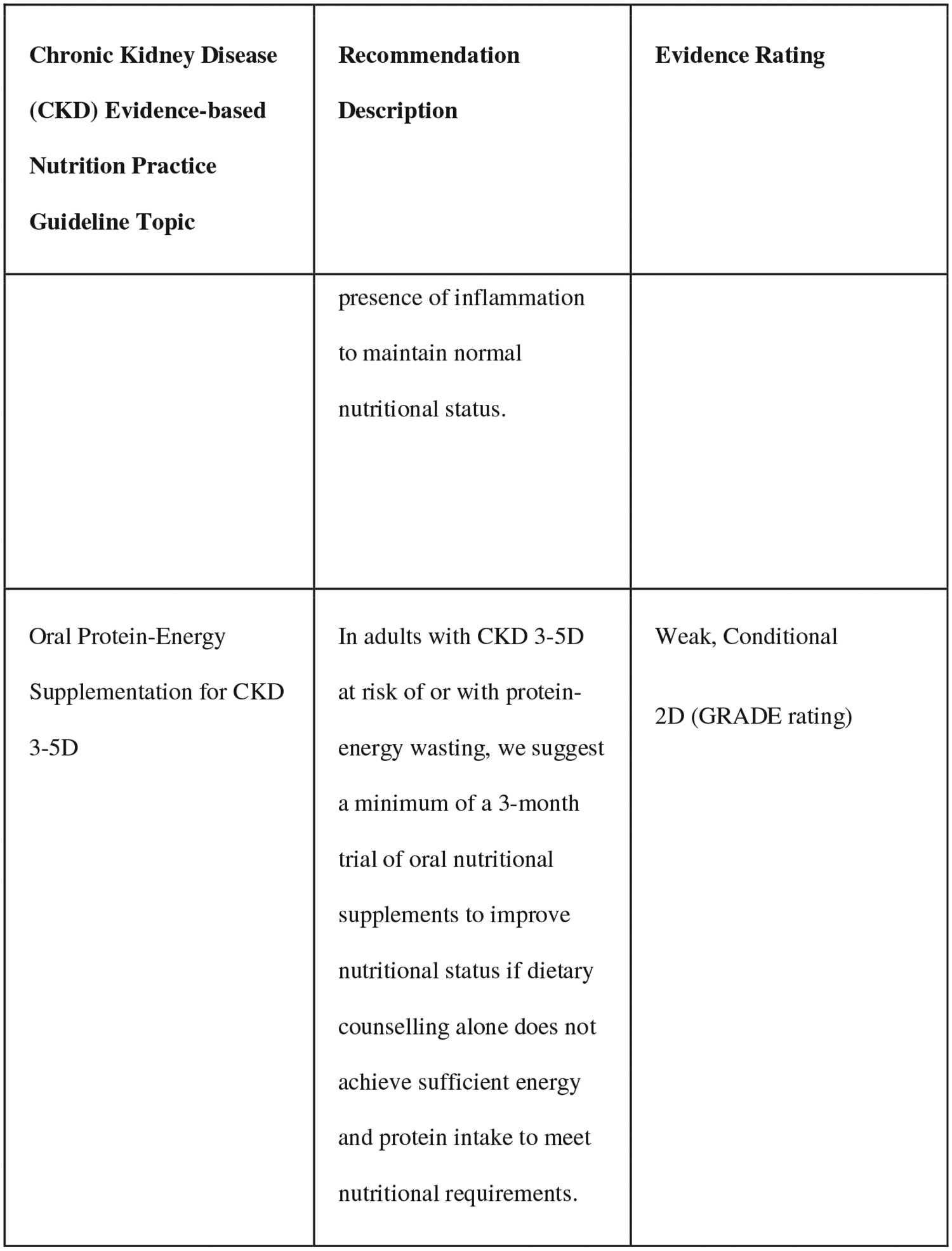

During phase 2, each participating RDN will use the NCP/T to document initial and follow-up nutrition care provided to 12 patients on dialysis (one new patient per week), along with patient outcomes, in ANDHII for a 3-month period. To decide which patients to enter into ANDHII, RDNs will initially screen patients for eligibility. The patient eligibility criteria include the following: age ≥18 years, residing in the United States, a referral diagnosis of CKD G5D, will receive care at the facility for at least 6 months, and stable as defined by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services—Conditions for Coverage for ESRD Facilities Regulation V52029 applied as per the RDNs’ clinical judgment or facility policy. The exclusion criteria include patients without a CKD G5D diagnosis and prisoners and pregnant women because of special research protections for these populations. If a patient is eligible for the study, RDNs will use an online random number generating tool (www.random.org) to determine if the patient record should be entered into ANDHII. This random entry process is used to minimize the chances that RDNs will allow conscious or unconscious bias to dictate the patients that they select for entry into ANDHII. RDNs will use the “true random number generator” to select a number between 0 and 1, with a “1” indicating that the patient should be entered into ANDHII and a “0” indicating that the patient should not be entered. RDNs will complete this process for every eligible patient until one patient per week is selected for entry into ANDHII. The RDN will then document follow-up visits for each patient previously added to ANDHII until the end of the 3-month phase 2 period. For each patient encounter, RDNs will record deidentified patient sociodemographic characteristics and parameters from the NCP (nutrition assessment/reassessment, nutrition diagnosis, nutrition intervention, and nutrition monitoring and evaluation) to document the nutrition care that was provided (Fig. 3).

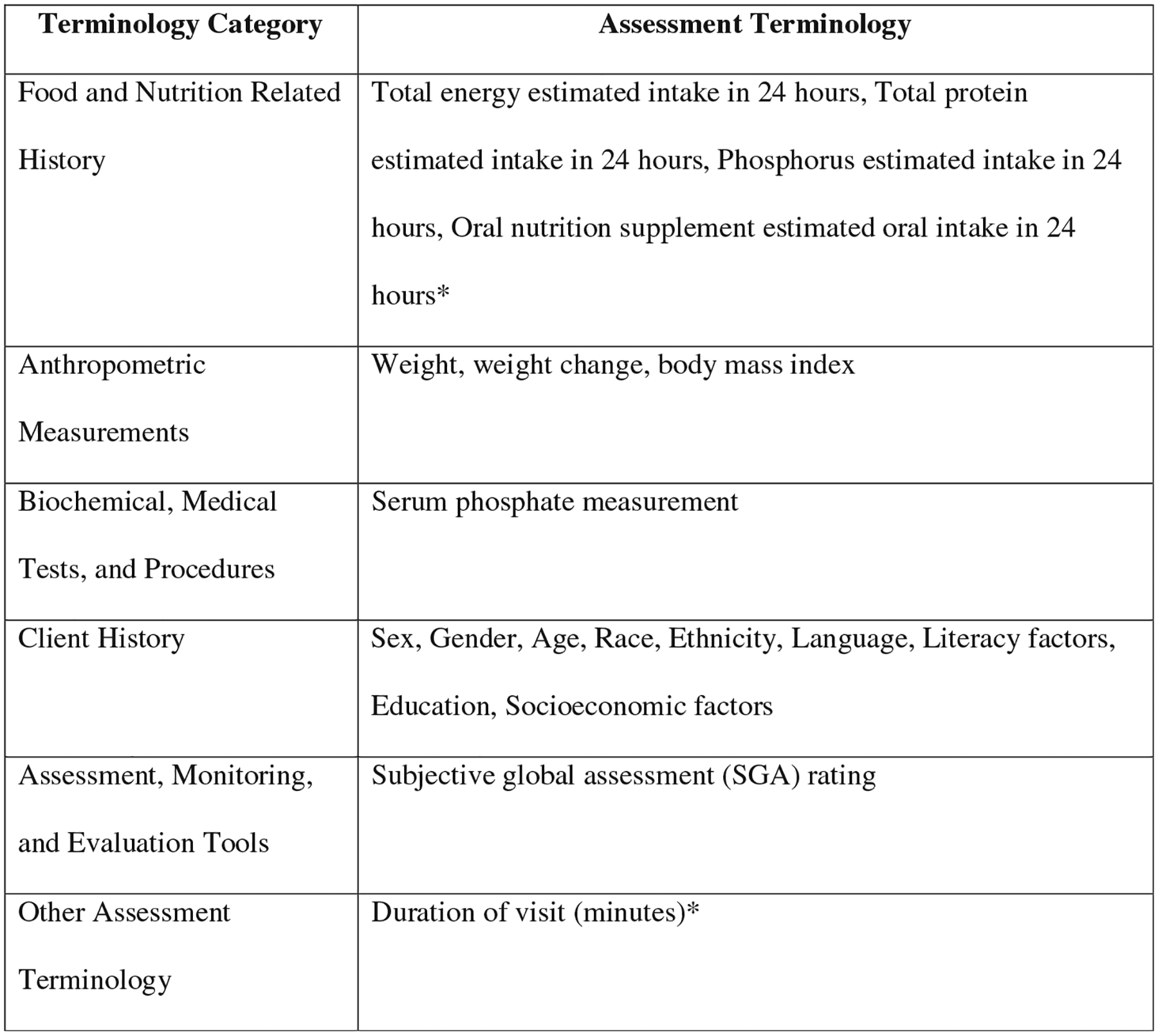

Figure 3.

Suggested terminology to document in the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Health Informatics Infrastructure (ANDHII)28 in the assessment step of the nutrition care process.27 *Denotes custom terms that were created for this project based on feedback from the Assessing Uptake and Impact of Guidelines for Clinical Practice in Renal Nutrition (AUGmeNt) study expert advisory group. Remaining terms are from the 2019 version of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Nutrition Care Process Terminology.27

In phase 3, RDNs will complete one of two midpoint training models, to which they will be randomly assigned in blocks of six: (1) EBNPG knowledge-focused training (knowledge-only group) or (2) EBNPG knowledge-focused training plus an implementation toolkit providing detailed support for five specific recommendations from the EBNPG (comprehensive group).

After completing the trainings, during phase 4, each RDN will use the NCP/T to document initial and follow-up nutrition care and patient outcomes for a different group of 12 patients on dialysis (one patient per week) into ANDHII for a 3-month period, following the same patient selection and documentation procedures outlined for phase 2.

In addition to documenting patient nutrition care into ANDHII, RDNs will be surveyed several times during the study (Fig. 2). In phase 1, surveys created by the study team will assess NCP/T-, Evidence Analysis Library-, and ANDHII-related28 knowledge, before and after the virtual trainings; feasibility and acceptability of the baseline trainings; and RDN professional qualifications and experience and characteristics of the hemodialysis clinic(s) where they work. Surveys conducted before and after the midpoint training (phase 3) will assess knowledge of the EBNPG and the feasibility and accessibility of the midpoint trainings. About 1 week after training, all RDNs will also be asked to complete an implementation survey to evaluate RDN perceived acceptability and anticipated adoption of the EBNPG recommendations. Finally, RDN surveys conducted at the end of the study (after phase 4) will assess the feasibility and acceptability of documenting nutrition care using ANDHII28 and perceived acceptability, adoption, and ad hoc adaptation of the EBNPG. The comprehensive group will also be asked to provide feedback on the implementation tools. The implementation surveys were created based on implementation literature30–32 and reviewed for content and face validity by renal nutrition clinicians, researchers, and patient advocates who serve on an advisory group for the study. All survey data will be collected and managed using the REDCap tool hosted by the University of New Mexico. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data collection for research studies.33,34

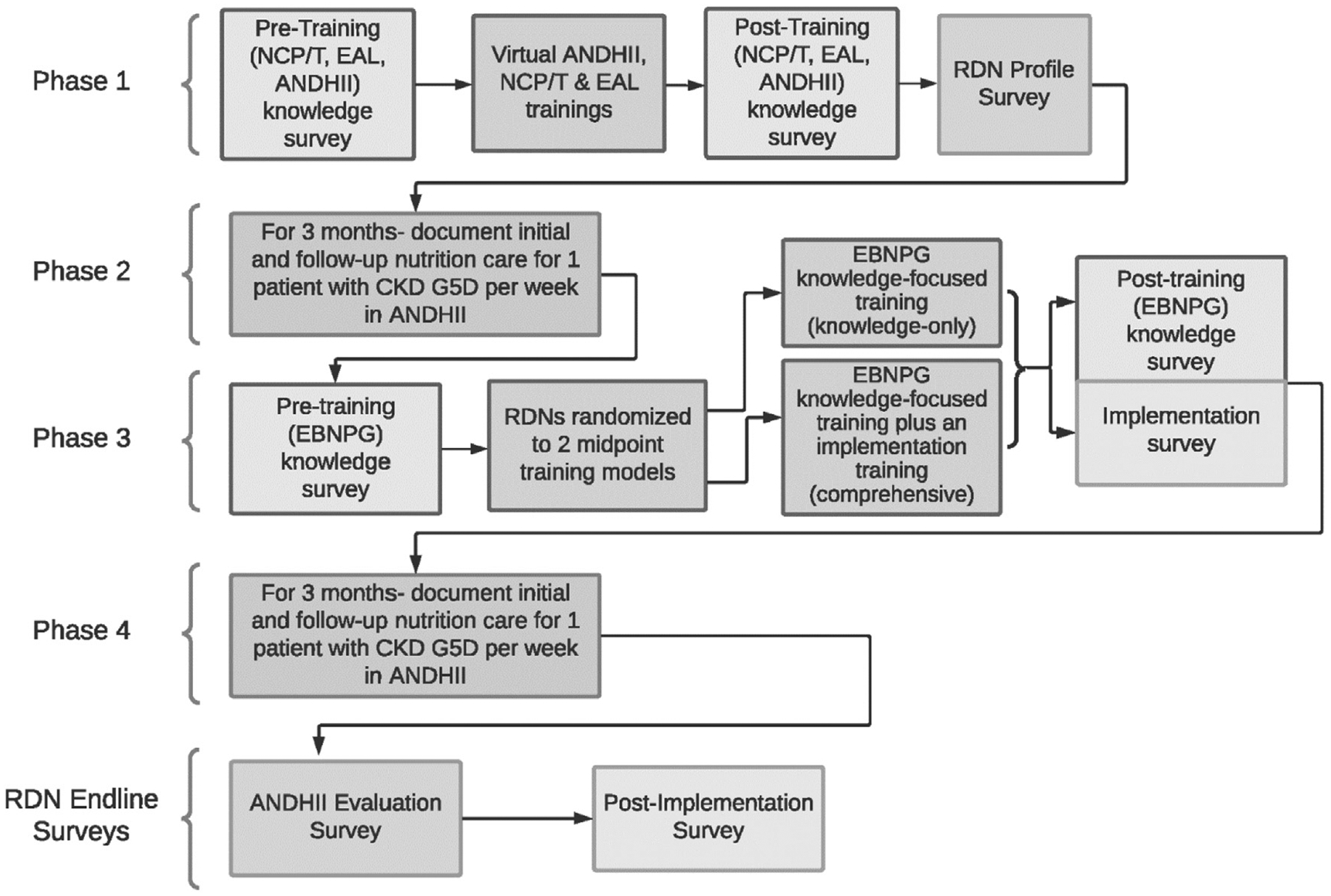

Evaluation of Implementation in the AUGmeNt Study

The AUGmeNt study will examine multiple implementation outcomes using a fidelity framework (Figs. 4 and 5), with emphasis on congruence with the EBNPG (primary implementation aim) and EBNPG acceptability, adoption, and adaptation (secondary implementation aim). The AUGmeNt fidelity framework, adapted from a previous fidelity framework developed by Carroll et al., considers adherence as an essential component of fidelity.30 Adherence is defined as delivering a service or intervention as it was written.30 In the context of this study, adherence will be defined as delivering the guideline recommendations as they were outlined by the guideline developers or content congruence between RDN care documented in ANDHII and care that would be expected based on the EBNPG. This will be conceptualized as expected care plans (ECPs).

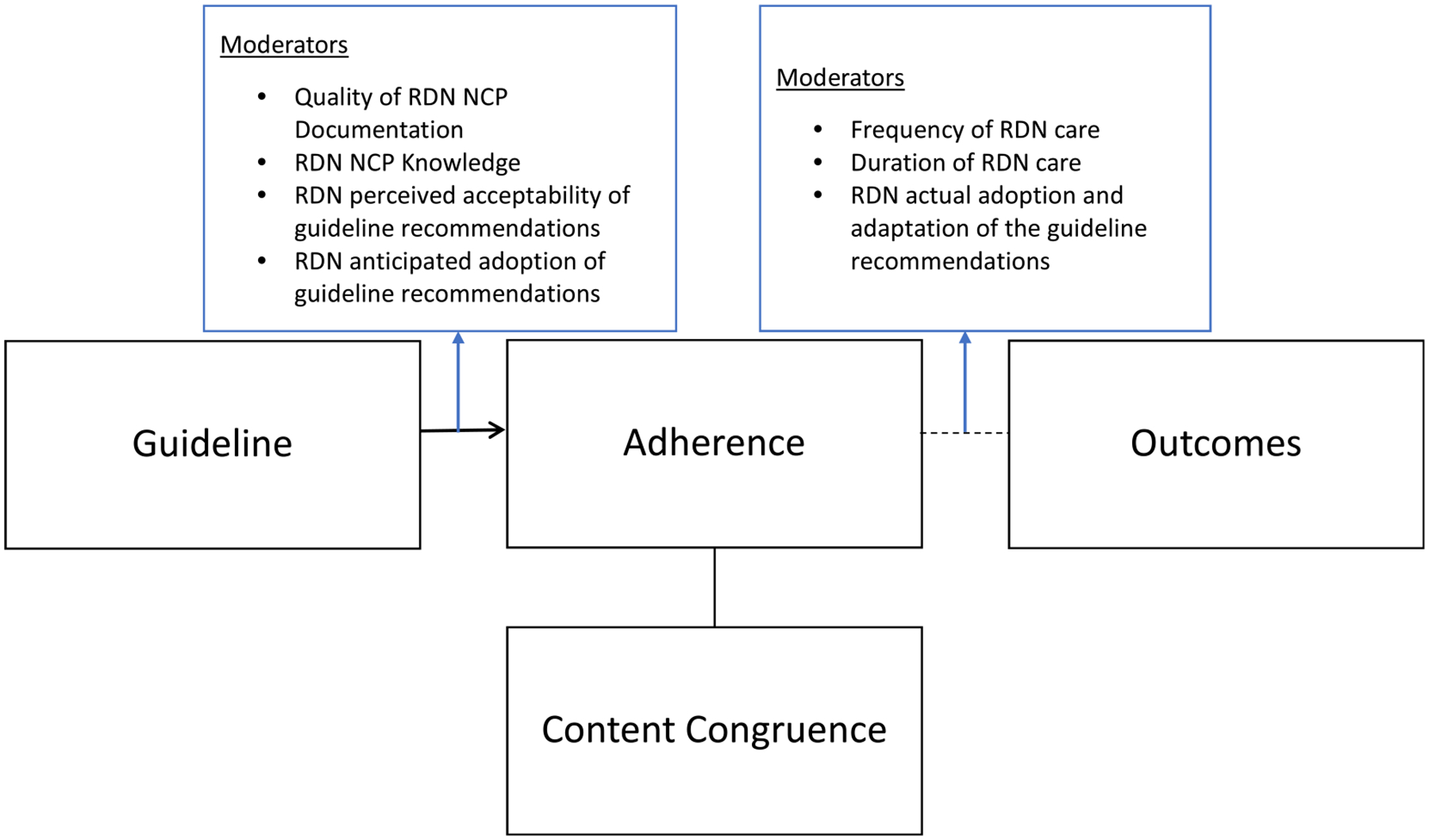

Figure 4.

Guideline implementation fidelity framework (Adapted from the study by Carroll et al. 2007).30 The framework includes a main aspect of adherence, content congruence, as well as moderators that may impact adherence and patient outcomes. RDN, registered dietitian nutritionist; NCP27, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Nutrition Care Process.

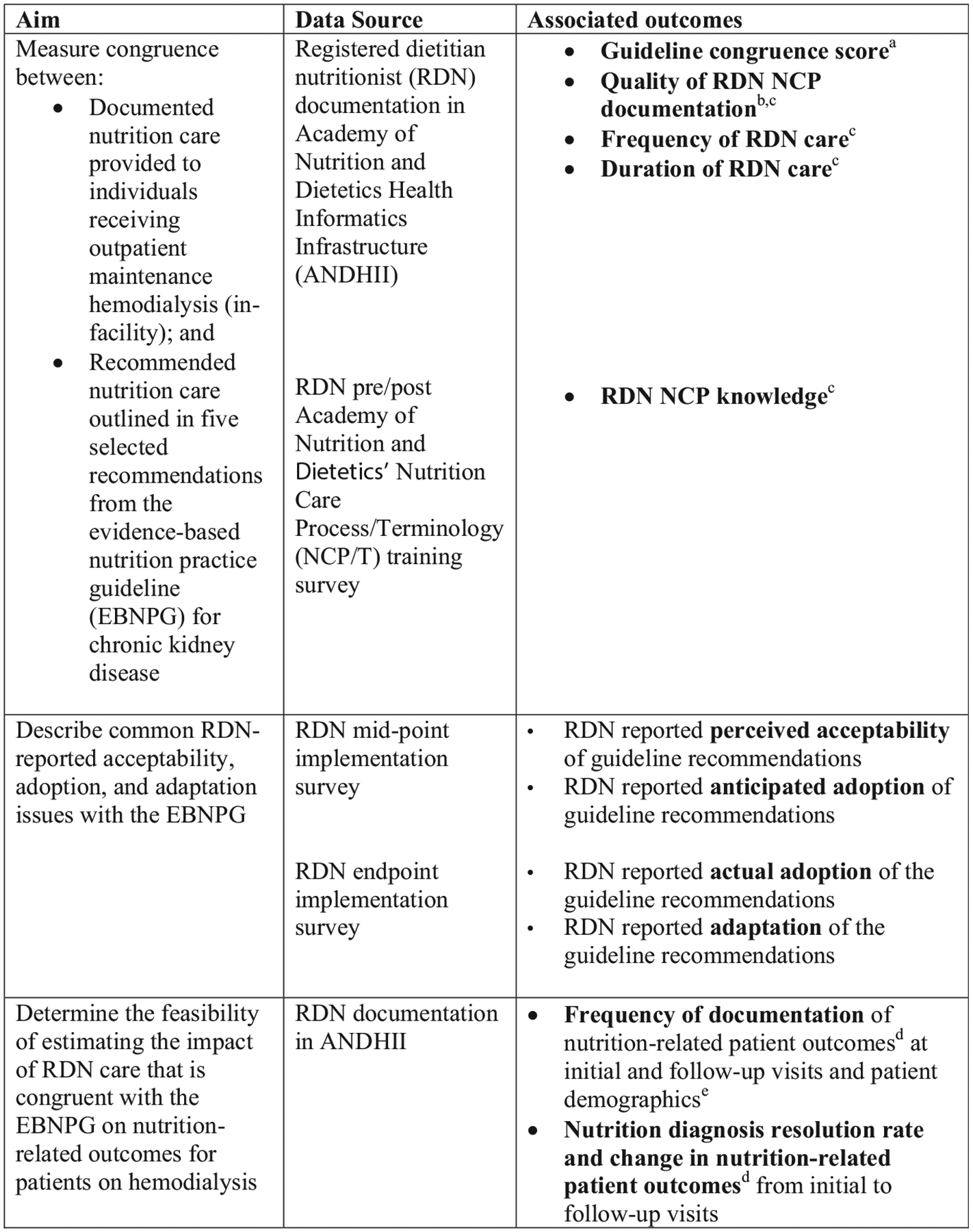

Figure 5.

Assessing Uptake and Impact of Guidelines for Clinical Practice in Renal Nutrition (AUGmeNt) study aim and outcome alignment. a Each documented RDN encounter assigned a congruence score using a natural language processing system37 that will compare RDN care documented into ANDHII28 and expected care plans developed from five recommendations included in the evidence-based nutrition practice guideline for chronic kidney disease.6,7 b A subset of documented care for each RDN will be scored for alignment with the NCP27 using a quality documentation audit tool called NCP Quality Evaluation and Standardization Tool or NCP-QUEST.42 c Denotes moderators that may impact adherence or outcomes as described in Figure 4 Guideline Implementation Fidelity Framework.30 d Nutrition-related patient outcomes from the NCPT27 may include subjective global assessment score, body weight, weight change, body mass index, protein intake, energy intake, oral nutrition supplement intake, phosphorus intake, and serum phosphorus. e Patient demographics from the NCPT may include sex, gender, age, race, ethnicity, preferred language, literacy, and education level. RDN, registered dietitian nutritionist; NCPT, Nutrition Care Process/Terminology.

ECPs are the specific standardized terms from the NCPT that should be present in documentation when an RDN is implementing care that is congruent with EBNPG recommendations. ECPs are based on a chain framework that links together six NCP chain components: evidence, diagnosis, etiology, intervention, goal, and outcome.35,36 As part of the planning process for the study, ECPs were developed by the AUGmeNt study team and advisory group by identifying the standardized NCPT that aligned with the six chain components for the five selected EBNPG recommendations. If there was an identified gap in existing NCPT terms to best document recommendation implementation, custom terms were created and added to the AUGmeNt ANDHII project. This process allows for the identification of additional terms to appropriately and comprehensively document nutrition care in different practice areas—in this case, renal nutrition. Collectively, the ECPs developed for this study will comprise the AUGmeNt NCP lexicon database.

A natural language processing system will be used to compare documented care with the AUGmeNt NCP lexicon database.37 Using the functionality of the OILS Twitter Scraper,38 a tool originally developed to evaluate unstructured text using sentiment analysis, text mining routines will automatically count the number of matching NCPT terms between documented care and the AUGmeNt NCP lexicon database. Based on RDN documentation, two elements will be used to inform evidence-component matches. Matching on both the indicator as well as an indication of an abnormal finding will be used (i.e., assessment of the measured value as “low/below goal” or “high/above goal” to match the ECP). Counts of the matching NCPT terms will be stratified by patient visit, the six NCP chain components, and the five recommendations.

For each patient visit, we will classify degree of congruence with the ECP for a specific recommendation into one of the four categories: not congruent, partially congruent, congruent, and fully congruent, depending on the number of matches for each of the six NCP components. Based on match criteria, ECPs will be given a score of 0–6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Match Criteria for the Expected Care Plans37 in the Automated Analyzer

| Nutrition Care Process Components | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence: Indicator | Evidence: Indication of Abnormal Finding | Diagnosis | Etiology Category | Intervention: Nutrition Prescription | Intervention | Goal | Outcome | ||

| 0.5 pt. | 0.5 pt. | 1 pt. | 1 pt. | 0.5 pt. | 0.5 pt. | 1 pt. | 1 pt. | Score | Classification |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | Not congruent |

| Match | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | Not congruent |

| Match | X | Match | X | X | X | X | X | 1.5 | Not congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | X | X | X | X | X | 2 | Not congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | X | X | Match | X | X | 2.5 | Partially congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | Match | X | X | X | X | 3 | Partially congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | X | X | X | 3.5 | Partially congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | X | X | 4 | Congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | X | Match | X | 4.5 | Congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | X | 5 | Congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | Match | X | Match | Match | Match | 5.5 | Congruent |

| Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | Match | 6 | Fully congruent |

The table outlines some possible combinations of matching terms to demonstrate the possible scores and classifications—a score of 0–6 and classification of not congruent to fully congruent. A term match can occur in any of the 6 NCP components. The evidence component has two parts: assessment term and the indication of abnormal finding, which can be below goal/low or above goal/high (i.e., protein intake of 20 g/day is below goal/low). Each component is worth 0.5 points. A term match can only occur for indication of abnormal findings if the corresponding evidence indicator term matches. The intervention component also has two parts: (1) the nutrition prescription where the diet order is provided (i.e., 2,000 kcal/day and 60 g/day) and (2) the intervention details, the plan to address the nutrition diagnosis.

In addition to content congruence, we will capture numerous fidelity moderators or aspects that potentially impact adherence. These include quality of RDN documentation,39 RDN NCP knowledge, RDN perceived acceptability of guideline recommendations, and RDN anticipated and actual adoption of guideline recommendations. Quality of documentation, as measured by effective use of the NCP, will be assessed on a subset of ANDHII documentation stratified by RDN using a documentation audit tool. The documentation audit tool that will be used for this study, which was based on previously existing NCP audit tools,40,41 is called NCP Quality Evaluation and Standardization Tool or NCP-QUEST.42 NCP-QUEST allows for a more comprehensive audit by including nutrition follow-ups or reassessment. RDN NCP knowledge will be estimated using the RDN’s score on the NCP questions included on the baseline training after survey. RDN perceived acceptability and anticipated and actual adoption of guideline recommendations will be evaluated via the implementation surveys administered after the midpoint training and after phase 4.

RDN guideline adherence can potentially impact patient outcomes (exploratory effectiveness aim). The moderators that may impact patient outcomes include frequency of RDN care, duration of RDN care, and RDN guideline adoption and adaptation. Frequency and duration of RDN care will be collected in ANDHII for use in patient outcome models; however, the CKD EBNPG does not currently make specific recommendations on duration or frequency of RDN care, so there will not be established guideline benchmarks. RDN adoption and adaptation of the guideline recommendations will be evaluated via the implementation survey administered after phase 4.

Sample Size

Power calculations for the number of RDNs to be recruited for the study are based on anticipated differences in congruence scores between the knowledge-only group and the comprehensive group. Based on findings from a previous study conducted with RDNs providing nutrition care for patients with diabetes,37 the standard deviation for congruence scores with a range of 0 to 6 is conservatively estimated to be 1.5 for this study. Given some potential uncertainty about the capacity to recruit and retain a large number of RDNs, calculations were performed assuming three potential recruitment and retention scenarios with 10, 20, and 30 RDNs per group participating and completing the study. For 80% power, sample sizes of 10, 20, and 30 RDNs per group will yield a detectable limit of 2.00, 1.37, and 1.11 units of the congruence score with corresponding design effects of 1.33, 0.91, and 0.74, respectively. RDN congruence scores will be modeled as a function of RDN characteristics using linear models. With 40 total RDNs, we will have approximately 80% power to detect the effect of a predictor that will give a full model R-square of 0.35 versus a reduced model R-square of 0.20 using a significance level of 0.05. Patient outcomes will be modeled as a function of patient and RDN characteristics using linear or logistic models. If 240 follow-up patient encounters are documented for those 40 RDNs (about 50% of anticipated follow-up encounters, to account for patient transplantation or hospitalization and RDN documentation burden), we will have approximately 80% power to detect the effect of a predictor that will give a full model R-square of 0.13 versus a reduced model R-square of 0.10 using a significance level of 0.05.

Data Analysis

Means with 95% confidence intervals will be used to describe pre-to-post training changes in RDN knowledge. For the first aim, means with 95% confidence intervals will be used to describe the congruence of RDN documentation in ANDHII with the EBNPG ECPs. This will be performed overall and stratified by study phase (2 or 4) and study group. Bivariate relationships between congruence of RDN documentation with the EBNPG and RDN study group, study phase (2 or 4), RDN years of experience, quality of RDN documentation, RDN NCP knowledge, RDN perceived acceptability of guideline recommendations, and RDN anticipated and reported actual adoption of guideline recommendations will be examined using a two-sided t-test with alpha = 0.05 or Pearson’s correlation coefficient, as appropriate. Mixed effects linear models will then be constructed to include covariates that are related to congruence of RDN documentation with the EBNPG (P <.10) and random effects of the RDN. Separate models will be constructed for each recommendation.

For the secondary implementation aim, RDN survey data will be descriptively analyzed to describe reported acceptability, adoption and adaptation issues by the RDN, and patient sociodemographic and site characteristics. Free text questions related to adaptation of the recommendations or implementation materials will be thematically analyzed.

For the exploratory effectiveness aim, patient encounter–level data will be used to describe changes in nutrition diagnosis status and nutrition-related patient outcomes, including malnutrition status (Subjective Global Assessment rating of well nourished, mild-moderate, or severe), body weight, weight change, body mass index, protein intake, energy intake, oral nutrition supplement intake, phosphorus intake, and serum phosphorus. Bivariate relationships between changes in the patient outcome of interest and RDN study group, study phase (2 or 4), RDN years of experience, quality of RDN documentation, RDN NCP knowledge, RDN perceived acceptability of guideline recommendations, RDN anticipated and reported actual adoption of guideline recommendations, and patient sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., sex, gender, age, race, ethnicity, preferred language, literacy, and education level) will be examined using a two-sided t-test with alpha = 0.05, a chi-squared test, or Pearson’s correlation coefficient, as appropriate. Mixed effects linear or logistic models will then be constructed to include covariates that are related to patient outcomes (P < .10), baseline value for the outcome of interest, and random effects of the RDN. Separate models will be constructed for each nutrition-related patient outcome of interest.

Anticipated Challenges

Some of the anticipated challenges with this study include potentially limited generalizability, as it may not be possible to recruit a fully representative set of RDNs and hemodialysis clinics (e.g., profit/nonprofit, urban/rural, distributed across the United States) given the study timeline, resources, and the logistical burdens associated with onboarding each site. The study team is attempting to address some of these generalizability concerns by recruiting via dialysis chains with multiple locations at a national level. However, the COVID-19 global pandemic has affected recruitment efforts and the study timeline, as clinics and RDNs nationwide shifted to crisis operations.

Additional issues may arise from RDN documentation errors in ANDHII. In the past, for example, patient sociodemographic factors and outcomes were not consistently documented, and there was often confusion around entering follow-up care. The virtual trainings for the AUGmeNt study have been designed to provide additional guidance and support for RDNs around these aspects of documenting into ANDHII.

Related to implementation outcomes, although multiple fidelity aspects are incorporated into the AUGmeNt study, others are not addressed, such as coverage of the guideline intervention or moderators such as quality of delivery and participant responsiveness.30

Trial Status and Dissemination Plans

As of August 2021, the first and second cohorts of RDNs are participating in the AUGmeNt study, and RDNs for additional cohorts are being recruited, with the intention of completing the study by Fall 2022 and disseminating the results in 2023. Aspects of the study design and rationale have been disseminated to researchers, nutrition and dietetics professionals, and medical providers via posters, session presentations, and peer-reviewed publications. As the results of the study are available, dissemination to these audiences will continue at professional conferences and via peer-reviewed publications, newsletter articles, and webinars.

Practical Application

The results of this study have the potential to influence clinical practice and development and implementation of future EBNPGs. Study results will describe usual RDN practice patterns for care of patients on dialysis and their congruence with EBNPGs, potentially highlighting areas of excellence as well as areas for improvement in current clinical practice. In addition, if providing an implementation toolkit in addition to a knowledge-based training improves RDN uptake of EBNPGs, this could be a model adopted for future EBNPGs. The study will also provide valuable feedback from practicing RDNs related to EBNPG acceptability, adoption, and adaptation, which can be used to refine future implementation resources and transmitted to the EBNPG developers for consideration during development of future renal nutrition guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Margaret Dittloff, MS, RDN; Margaret Isham, RDN; Lindsay Woodcock, MS, RDN, LDN; Damien Sanchez, PhD, CRP; and the AUGmeNt advisory group: Lindsey Zirker, MS, RDN; Annabel Biruete, PhD, RDN; Brandon Kistler, PhD, MS, RDN; Jessie Pavlinac, MS, RD, CSR, LD; Joyce Vergili, RDN; Lesley McPhatter, RDN; and Daniel Garver, PhD for their contributions to developing the protocol for this project. The authors would also like to dedicate this article to the advisory group member and patient advocate Maile Robb, who made important contributions to the study trainings before passing away in March 2020.

Support:

G.V.P., C.P., E.L-J., Li.M, J.K.A., K.K., and A.S. are employees of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, which has a financial interest in the ANDHII platform and the Nutrition Care Process Terminology described here. E.Y.J., M.M.B., and G.P.M. have contracts with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Financial Disclosure:

This project was supported by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation through a grant from the Academy’s Renal Dietitians Practice Group and Relypsa, a Vifor Pharma Group Company. La.M.’s work on this project is supported in part by grant #R01MD013752 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and by Dialysis Clinic Inc., a national nonprofit dialysis provider. The funders had no role in the design of this study; nor will the funders have influence over the execution of the study, data analysis, or reporting of results. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics provided staff support for the development of the study protocol via the Nutrition Research Network, the Data Science Center, and the Evidence Analysis Library. Financial and material support for the development of Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Health Informatics Infrastructure (ANDHII) has been provided by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the Commission on Dietetic Registration.

Footnotes

Credit Authorship Contribution Statement

Gabriela V. Proaño: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Supervision. Constantina Papoutsakis: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Erin Lamers-Johnson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Lisa Moloney: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Mary M. Bailey: Writing – original draft. Jenica K. Abram: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Kathryn Kelley: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Alison Steiber: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. George P. McCabe: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Larissa Myaskovsky: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Elizabeth Yakes Jimenez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

References

- 1.National Kidney Foundation. Facts About Chronic Kidney Disease. https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/about-chronic-kidney-disease. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease Basics | Chronic Kidney Disease Initiative | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/basics.html. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 3.Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Dorman NM, et al. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: report of a kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) consensus conference. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1117–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Renal Data System. US Renal Data System 2019 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.usrds.org/2019/view/USRDS_2019_ES_final.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Renal Data System. Chapter 1: Incidence, Prevalence, Patient Characteristics, and Treatment Modalities. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.usrds.org/2018/view/v2_01.aspx. Accessed July 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikizler TA, Burrowes JD, Byham-Gray LD, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in CKD: 2020 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:S1–S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evidence Analysis Library. EAL-KDOQI (CKD) guideline. https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?menu=5303&cat=5557. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 8.Kent PS, McCarthy MP, Burrowes JD, et al. Academy of nutrition and dietetics and National kidney Foundation: Revised 2014 standards of practice and standards of professional performance for registered dietitian nutritionists (competent, proficient, and expert) in nephrology nutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:1448–1457.e1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swan WI, Vivanti A, Hakel-Smith NA, et al. Nutrition care process and model update: toward realizing people-centered care and outcomes Management. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:2003–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handu D, Moloney L, Rozga MR, Cheng F, Wickstrom D, Acosta A. Evolving the Academy Position paper process: Commitment to evidence-based practice. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1743–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papoutsakis C, Moloney L, Sinley RC, Acosta A, Handu D, Steiber AL. Academy of nutrition and dietetics methodology for developing evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117: 794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.University of Washington. What is implementation science? | implementation science at UW. https://impsciuw.org/implementation-science/learn/implementation-science-overview/. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 13.Francke AL, Smit MC, De Veer AJ, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2008;8:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan WV, Pearson TA, Bennett GC, et al. ACC/AHA special report: clinical practice guideline implementation strategies: a summary of systematic reviews by the NHLBI implementation science work group. Circulation. 2017;135:e122–e137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation—a Scoping review. Healthcare. 2016;4:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy WJ, Hand RK, Abram JK, Papoutsakis C. Impact of diabetes prevention guideline adoption on health outcomes: a Pragmatic implementation Trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121(10):P2090–P2100.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Med Care. 2012;50:217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Houghton Mifflin Company. http://www.sfu.ca/%7Epalys/Campbell%26Stanley-1959-Exptl%26QuasiExptlDesignsForResearch.pdf?. Accessed November 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohtake PJ, Childs JD. Why publish study protocols? Phys Ther. 2014;94:1208–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li T, Boutron I, Salman RA-S, et al. Review and publication of protocol submissions to trials – what have we learned in 10 years? Trials. 2017;18:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Office for Human Research Protections. Coded Private Information or Specimens Use in Research, Guidance (2008). HHS.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/research-involving-coded-private-information/index.html. Accessed October 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines for nutrition in chronic renal Failure. In: National Kidney Foundation, ed.2000: https://www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/docs/kdoqi2000nutritiongl.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evidence Analysis Library. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) guideline. https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?menu=5303&pcat=3927&cat=3929. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 24.Proaño G, Moloney L, Kelley K, et al. Promoting uptake of guidelines for clinical practice in renal nutrition. In: Paper presented at: Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2020/09/01, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.May C, Rapley T, Mair F, et al. Normalization Process Theory On-line Users’ Manual, Toolkit and NoMAD instrument. http://www.normalizationprocess.org. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 26.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Resources. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 27.Swan WI, Pertel DG, Hotson B, et al. Nutrition care process (NCP) update part 2: developing and using the NCP terminology to demonstrate Efficacy of nutrition care and related outcomes. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119: 840–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy WJ, Yadrick MM, Steiber AL, Mohan V, Papoutsakis C. Academy of nutrition and dietetics health informatics infrastructure (AND-HII): a Pilot study on the documentation of the nutrition care process and the Usability of ANDHII by registered dietitian nutritionists. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1966–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services-CMS. Advance Copy – end stage renal disease (ESRD) Program Interpretive guidance Version 1.1 In: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, ed.2008: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCletter09-01.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Sci. 2007;2:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters D, Tran N, Adam T, Research AfHPaS, World Health Organization. WHO | Implementation Research in Health: a Practical Guide. World health Organization. https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/implementationresearchguide/en/. Accessed November 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research Agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38: 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson KL, Davidson P, Swan WI, et al. Nutrition care process chains: the “Missing link” between research and evidence-based practice. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:1491–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakel-Smith N, Lewis NM. A standardized nutrition care process and language are essential components of a conceptual model to guide and document nutrition care and patient outcomes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1878–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamers-Johnson E, Kelley K, S anchez DM, et al. Academy of nutrition and dietetics nutrition research Network: Validation of a novel nutrition informatics tool to assess agreement between documented nutrition care and evidence-based recommendations. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021; 10.1016/j.jand.2021.03.013. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flor NV. OILS Twitter Scraper [computer program]. Albuquerque, NM: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chui T-K, Proaño GV, Raynor HA, Papoutsakis C. A nutrition care process audit of the national quality improvement dataset: Supporting the improvement of data quality using the ANDHII platform. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120:1238–1248.e1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hakel-Smith N, Lewis NM, Eskridge KM. Orientation to nutrition care process standards improves nutrition care documentation by nutrition practitioners. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:1582–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lövestam E, Orrevall Y, Koochek A, Karlström B, Andersson A. Evaluation of a nutrition care process-based audit instrument, the diet-NCP-audit, for documentation of dietetic care in medical records. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28:390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis S, Miranda L, Kurtz J, Larison L, Brewer WJ, Papoutsakis C. Nutrition care process quality evaluation and Standardization tool (NCP-QUEST): the next frontier in quality evaluation of documentation. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021; 10.1016/j.jand.2021.07.004. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]