Abstract

To enhance formulation and interventions for emotional distress symptoms, research should aim to identify factors that contribute to distress and disorder. One way to formulate emotional distress symptoms is to view them as state manifestations of underlying personality traits. However, the metacognitive model suggests that emotional distress is maintained by metacognitive strategies directed by underlying metacognitive beliefs. The aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate the role of these factors as predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms in a cross-sectional sample of 4936 participants collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality traits (especially neuroticism) were linked to anxiety and depression, but metacognitive beliefs and strategies accounted for additional variance. Among the predictors, metacognitive strategies accounted for the most variance in symptoms. Furthermore, we evaluated two statistical models based on personality traits versus metacognitions and found that the latter provided the best fit. Thus, these findings indicate that emotional distress symptoms are maintained by metacognitive strategies that are better accounted for by metacognitions compared with personality traits. Theoretical and clinical implications of these findings are discussed.

Key Words: Anxiety, depression, personality, Big-5, metacognitive beliefs

Common mental disorders are highly prevalent in the general population (Kessler et al., 2005), and as many as one third of adults in Western countries report elevated emotional distress symptoms such as anxiety and depression (Haller et al., 2014; Shim et al., 2011; Steel et al., 2014). These symptoms frequently co-occur (Jacobson and Newman, 2017) and are associated with substantially reduced quality of life for the individual (Saarni et al., 2007) as well as with enormous societal costs (Greenberg and Birnbaum, 2005; Mathers and Loncar, 2006). Even mild symptoms can be debilitating (Chachamovich et al., 2008; Haller et al., 2014), and there is an elevated risk that mild depression and anxiety symptoms can later develop into clinical disorders (Bosman et al., 2019; Pietrzak et al., 2013). Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to dramatic increases in emotional distress symptoms in the general population (Daly et al., 2020; Ebrahimi et al., 2021; Ettman et al., 2020), causing concern that it will lead to a mental health crisis in the years to come (Holmes et al., 2020). Therefore, the need to identify which factors contribute to emotional distress symptoms with an aim to inform effective interventions is as relevant as ever.

One way to formulate emotional distress symptoms is to view them as state manifestations of underlying personality traits. The Five-Factor Model (Costa and McCrae, 1985) is a frequently used framework to describe universal personality dimensions founded on five broad trait dimensions (“Big-5”): neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. These traits have been linked to psychopathology (Kotov et al., 2010), and in particular, neuroticism is viewed as a trait that accounts for psychological vulnerability (Naragon-Gainey and Watson, 2018) and can account for individual differences in affect in response to extreme environmental contexts. In line with this notion, recent studies show that people high on neuroticism react to the pandemic with stronger negative affect (Aschwanden et al., 2020; Kroencke et al., 2020; Lee and Crunk, 2022). Furthermore, lower extraversion, lower openness, lower agreeableness, and lower conscientiousness have been found to be related to higher distress levels (Nikčević and Spada, 2020).

The metacognitive model of psychological disorders (Wells and Matthews, 1994) offers an alternative formulation of emotional distress symptoms. In this perspective, emotional distress is maintained by a negative thinking style called the cognitive attentional syndrome (CAS) consisting of worry/rumination, threat monitoring, and unhelpful coping strategies (Wells, 2009). The CAS is further linked to underlying metacognition, for example, in the form of metacognitive beliefs (e.g., “I cannot stop worrying”). In this perspective, the CAS is considered the more proximal cause of distress, whereas metacognitions direct the CAS and can also be identified as markers of psychological vulnerability in the absence of CAS activation (Wells, 2019). Beliefs about the uncontrollability and dangerousness of cognition are central to the model as these beliefs compromise choice of effective self-regulation strategies and can lead to negative interpretations of cognition itself (Wells, 2009).

A challenge with formulating emotional distress symptoms within a personality framework is that personality dispositions do not yield useful information on the underlying mechanisms of how traits are connected to maladaptive self-regulation and negative outcomes that limit the application in clinical settings (Claridge and Davis, 2001). However, the metacognitive framework holds the advantage of specifying mechanisms underlying distress and interventions that can effectively reduce negative outcomes (Wells, 2009).

The aim of the present study was therefore to explore personality traits and metacognitive beliefs and strategies as predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms while controlling for demographic variables because female sex, younger age, and lower education levels are associated with elevated distress levels (Ettman et al., 2020; Ebrahimi et al., 2021). The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which can be considered an extreme stressor likely to impact on trait (e.g., personality traits and metacognitions) and state factors (e.g., metacognitive strategies) linked to emotional distress symptoms. Our hypotheses were as follows: 1) personality traits, and in particular neuroticism, will be significantly associated with anxiety and depression symptoms; and 2) positive metacognitive beliefs, negative metacognitive beliefs, and metacognitive strategies will be significantly and positively associated with anxiety and depression symptoms and explain additional variance in symptoms when controlling for demographics and personality traits. In addition, we expected that metacognitive strategies will be stronger associated with anxiety and depression than personality traits and metacognitive beliefs as they are considered the more proximal influence on distress according to metacognitive theory (Wells and Matthews, 1994).

We also set out to evaluate the absolute and relative fit of a basic metacognitive model specified with metacognitive beliefs leading to metacognitive strategies (i.e., CAS), which further lead to emotional distress symptoms. The aim here was to further evaluate the appropriateness of formulating emotional distress symptoms and its hypothesized maintenance factors in the metacognitive model (Wells, 2009). To strengthen this evaluation, we also evaluated the fit of a comparison model where the metacognitive factor in the first model was replaced with personality traits. Our research question was if these models fit the data and if the metacognitive model fitted better than the comparison.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

The present study is part of the Norwegian COVID-19, Mental Health, and Adherence Project, a survey-based project aiming to evaluate mental health consequences and associated factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. The project was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (reference number: 125510) and registered with the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (reference number: 802810). Invitation to take part in the survey was distributed on national, regional, and local information platforms in addition to dissemination of the online survey to a random selection of Norwegian adults through a Facebook Business algorithm. Eligible participants were adults (18 years and older) currently residing in Norway. The procedure is carefully explained elsewhere (Ebrahimi et al., 2021), with a total of 10,061 participants in the first data collection.

The present study use data from the second data collection (survey-based project in the section described above), where data on personality were gathered at the same time with emotional distress and metacognitions. Following the guidelines of Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (Von Elm et al., 2007), and the health estimate reporting standards laid out in the GATHER statement (Stevens et al., 2016), this study was preregistered before any data collection, which can be derived from ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT04444505). The data were collected between June 22 and July 13, 2020, a period approximately 1 week after the major viral mitigation protocols were lifted in Norway and where the national viral mitigation protocols and guidelines were held constant.

A total of 4936 participants took part in the study, and the sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. In the total sample, the mean age was 38.93 (SD = 13.75), 3911 (79.2%) were female, and 901 (18.3%) self-reported that they were currently diagnosed with a mental disorder.

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics (n = 4936)

| Age, mean (SD) | 38.93 (13.75) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female, n (%) | 3911 (79.2) | |

| Male, n (%) | 1010 (20.5) | |

| Other, n (%) | 15 (0.3) | |

| Current self-reported mental disorder | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 901 (18.3) | |

| No, n (%) | 4035 (81.7) | |

| Civil status | ||

| Married or in a civil partnership, n (%) | 2337 (47.35) | |

| Single/divorced, n (%) | 2599 (52.65) | |

| Education | ||

| Did not complete junior high school, n (%) | 6 (0.12) | |

| Completed junior high school, n (%) | 186 (3.77) | |

| Completed high school, n (%) | 741 (15.01) | |

| Currently studying at a university, n (%) | 779 (15.78) | |

| Completed university degree, n (%) | 3224 (65.32) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Native, n (%) | 4542 (92.0) | |

| Nonnative, n (%) | 394 (18.0) | |

n, number; SD, standard deviation.

Measures

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) is a 7-item self-report scale assessing severity of anxiety symptoms during the past 2 weeks. The instrument has shown excellent internal consistency with an alpha of 0.92 (Löwe et al., 2008). It was developed as a screener for GAD in primary care setting but is increasingly used as a measure for anxiety in general (Johnson et al., 2019; Magnúsdóttir et al., 2022) and in anxiety disorder research (Dear et al., 2011), thus the term “anxiety symptoms” is used in this manuscript when referring to the GAD-7. In the present study, the internal consistency was good, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.90.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item self-report scale assessing the severity of depression symptoms during the past 2 weeks. The instrument has shown good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha from 0.80 and above (Kroenke et al., 2010). In the present study, the internal consistency was good, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.91.

The Big Five Inventory 10 (Rammstedt and John, 2007) is a 10-item self-report scale assessing the Big-5 personality dimensions using two items for each dimension. The psychometric properties of the BFI-10 have been reported as good (Rammstedt and John, 2007). No Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the factors as they are indicated by two items each.

The CAS-1 (Wells, 2009) is a 16-item self-report tool developed to assess metacognitive beliefs (positive and negative) and strategies (worry/rumination, threat monitoring, coping strategies). It has a three-factor solution with good psychometric properties (Nordahl and Wells, 2019). In the present study, the internal consistency was 0.63 for positive beliefs, 0.71 for negative beliefs, and 0.91 for strategies.

Overview of Statistical Analyses

Using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27, bivariate correlations were used to explore the basic associations among the variables, and two hierarchical linear regressions were used to assess the additional contribution of personality traits and metacognitive factors in explaining variance in anxiety and depression when controlling for demographics. The metacognitive factors were entered on separate steps with the aim to evaluate any additional contribution from them as metacognitive theory distinguishes among these components and suggest a causal sequence for them (Wells, 2009).

In a secondary set of analyses, we evaluate the model fit of a metacognitive model consisting of and distinguishing among metacognitive beliefs, metacognitive strategies, and emotional distress symptoms in line with metacognitive theory (Wells, 2009). This model was specified by a latent distress factor consisting of the observed variables GAD-7 total score and PHQ-9 total score; a latent CAS factor consisting of the observed variables worry/rumination (CAS-1 item 1), threat monitoring (CAS-1 item 2), and maladaptive coping strategies (CAS-1 total score of scale 3); and a latent metacognitive factor. To create the metacognitive belief factor, we used the four items assessing negative metacognitive beliefs from the CAS-1 measure as negative metacognitive beliefs is the most important factor underlying CAS strategies according to metacognitive theory (Wells, 2009) and because earlier studies have indicated that negative but not positive metacognitive beliefs account for unique variance in symptoms when also controlling metacognitive strategies (Nordahl and Wells, 2019). In addition, we evaluated a second model where personality traits (the four with the strongest association to symptoms) constituted a latent personality factor that replaced the latent metacognitive factor in the first model, keeping the number of indicators and all other variables and paths unchanged. The aims here were to evaluate if both models with the same number of variables and identical paths fit the data and to evaluate if one model fitted the data better than the other.

The SEM analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS AMOS Graphics version 26. Four commonly recommended fit statistics were used to evaluate the models: the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The CFI and TLI should be above 0.95, the RMSEA should be below or close to 0.06, the upper limit of the 90% RMSEA confidence interval (CI) should not exceed 0.10 to represent a good fit, and the SRMR should be less than 0.08 (Browne and Cudeck, 1993; Hu and Bentler, 1999). We used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1974) to compare the fit of the two nonnested models. When both models have the same number of indicators, latent variables, and paths, the model with the lowest AIC value is considered to fit best to the data.

RESULTS

Correlational Analyses

The mean scores of the variables and the bivariate correlations among them are presented in Table 2. Anxiety and depression showed the strongest association with neuroticism among the personality traits, and with metacognitive strategies among the metacognitive factors.

TABLE 2.

Bivariate Correlations Between the Variables With Mean Values and Standard Deviations (n = 4936)

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GAD | 0.805** | 0.534** | −0.167** | 0.038** | −0.233** | −0.095** | 0.277** | 0.514** | 0.804** | 4.66 (4.37) |

| 2 | PHQ | 0.464** | −0.231** | 0.002 | −0.232** | −0.180** | 0.257** | 0.494** | 0.757** | 6.63 (5.66) | |

| 3 | N | −0.277** | 0.033 | −0.280** | −0.152** | 0.205** | 0.402** | 0.534** | 5.54 (2.22) | ||

| 4 | E | 0.079** | 0.258** | 0.155** | −0.113** | −0.163** | −0.193** | 6.92 (2.20) | |||

| 5 | O | 0.017 | 0.038** | 0.027 | −0.009 | 0.043** | 7.16 (2.02) | ||||

| 6 | A | 0.174** | −0.173** | −0.231** | −0.233** | 7.49 (1.57) | |||||

| 7 | C | −0.065** | −0.133** | −0.136** | 7.76 (1.60) | ||||||

| 8 | PMB | 0.497** | 0.362** | 143.16 (74.73) | |||||||

| 9 | NMB | 0.567** | 112.43 (84.65) | ||||||||

| 10 | CAS | 13.35 (11.94) |

GAD, anxiety symptoms; PHQ, depression symptoms; N, neuroticism; E, extraversion; O, openness; A, agreeableness; C, conscientiousness; PMB, positive metacognitive beliefs; NMB, negative metacognitive beliefs; CAS, metacognitive strategies.

**p < 0.01.

Linear Regression Analyses

When anxiety symptoms were used as the dependent variable, sex, age, and education level were entered together in step 1 and accounted for 7.3% of the variance. On the second step, personality traits entered as a block accounted for an additional 24.0% of the variance in anxiety symptoms. Among the personality traits, neuroticism, openness, and agreeableness accounted for individual variance. On the third step, positive metacognitive beliefs accounted for an additional 2.2% of the variance, and on the fourth step, negative metacognitive beliefs accounted for an additional 6.8% of the variance. In the fifth and final step, metacognitive strategies accounted for an additional 26.6% of the variance. In the final model when the overlap among all the predictors were controlled, lower education level, higher neuroticism, higher extraversion, lower agreeableness, higher conscientiousness, lower levels of positive metacognitive beliefs, higher levels of negative metacognitive beliefs, and higher levels of metacognitive strategies all accounted for unique variance in (higher) anxiety symptoms. Among the predictors in the final model, metacognitive strategies were by far the strongest predictor of anxiety. In sum, the predictors accounted for 66.9% of the variance in anxiety symptoms. The regression summary statistics are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical Linear Regression With Anxiety Symptoms as the Dependent, and Sex/Age/Education Level, Personality Traits, and Metacognitive Beliefs and Strategies as Predictors (n = 4963)

| Anxiety–GAD-7 | F Change | R2 Change | r | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 129.801 | 0.073** | |||

| Sex | −0.070 | −5.142** | |||

| Age | −0.200 | −14.583** | |||

| Education | −0.112 | −8.137** | |||

| 2 | 343.951 | 0.240** | |||

| Sex | −0.016 | −1.351 | |||

| Age | −0.099 | −8.398** | |||

| Education | −0.073 | −6.223** | |||

| N | 0.412 | 34.925** | |||

| E | −0.013 | −1.066 | |||

| O | 0.053 | 4.522** | |||

| A | −0.089 | −7.511** | |||

| C | 0.008 | 0.673 | |||

| 3 | 163.130 | 0.022** | |||

| Sex | −0.026 | −2.232* | |||

| Age | −0.075 | −6.423** | |||

| Education | −0.077 | −6.642** | |||

| N | 0.392 | 33.723** | |||

| E | −0.006 | −0.481 | |||

| O | 0.046 | 3.967** | |||

| A | −0.071 | −6.138** | |||

| C | 0.008 | 0.658 | |||

| Positive MB | 0.148 | 12.772** | |||

| 4 | 558.911 | 0.068** | |||

| Sex | −0.018 | −1.618 | |||

| Age | −0.050 | −4.512** | |||

| Education | −0.051 | −4.655** | |||

| N | 0.308 | 27.946** | |||

| E | −0.001 | −0.065 | |||

| O | 0.047 | 4.298** | |||

| A | −0.049 | −4.460** | |||

| C | 0.020 | 1.844 | |||

| Positive MB | 0.018 | 1.619 | |||

| Negative MB | 0.260 | 23.641** | |||

| 5 | 3945.435 | 0.266** | |||

| Sex | 0.007 | 0.881 | |||

| Age | −0.007 | −0.865 | |||

| Education | −0.027 | −3.265** | |||

| N | 0.109 | 13.227** | |||

| E | 0.018 | 2.141* | |||

| O | 0.010 | 1.183 | |||

| A | −0.028 | −3.430** | |||

| C | 0.033 | 4.014** | |||

| Positive MB | −0.041 | −4.952** | |||

| Negative MB | 0.062 | 7.509** | |||

| CAS | 0.515 | 62.813** |

r, semipartial (part) correlation; N, neuroticism; E, extraversion; O, openness; A, agreeableness; C, conscientiousness; MB, metacognitive beliefs; CAS, metacognitive strategies.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

When depression symptoms were used as the dependent variable, sex, age, and education level were entered together in step 1 and accounted for 7.8% of the variance, and all variables accounted for unique variance. In the second step, personality traits entered as a block accounted for an additional 19.1% of the variance in depression symptoms. In the third step, positive metacognitive beliefs accounted for an additional 1.9% of the variance, and on the fourth step, negative metacognitive beliefs accounted for an additional 6.8% of the variance. In the fifth and final step, metacognitive strategies accounted for an additional 24.3% of the variance. In the final model when the overlap among all the predictors was controlled, lower age, lower education level, higher neuroticism, lower extraversion, lower agreeableness, lower conscientiousness, lower levels of positive metacognitive beliefs, higher levels of negative metacognitive beliefs, and higher levels of metacognitive strategies all accounted for unique variance in (higher) depression symptoms. Metacognitive strategies were by far the strongest correlate of depression in the final model. In sum, the predictors accounted for 59.9% of the variance in depression symptoms. The regression summary statistics are presented in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical Linear Regression With Depression Symptoms as the Dependent, and Sex/Age/Education Level, Personality Traits, and Metacognitive Beliefs and Strategies as Predictors (n = 4963)

| Depression–PHQ-9 | F Change | R2 Change | r | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 139.727 | 0.078** | |||

| Sex | −0.059 | −4.334** | |||

| Age | −0.193 | −14.134** | |||

| Education | −0.145 | −10.576** | |||

| 2 | 257.909 | 0.191** | |||

| Sex | −0.033 | −2.712** | |||

| Age | −0.104 | −8.534** | |||

| Education | −0.104 | −8.570** | |||

| N | 0.314 | 25.795** | |||

| E | −0.086 | −7.101** | |||

| O | 0.029 | 2.416* | |||

| A | −0.082 | −6.708** | |||

| C | −0.078 | −6.436** | |||

| 3 | 128.670 | 0.019** | |||

| Sex | −0.042 | −3.506** | |||

| Age | −0.081 | −6.755** | |||

| Education | −0.108 | −8.962** | |||

| N | 0.296 | 24.591** | |||

| E | −0.080 | −6.650** | |||

| O | 0.023 | 1.890 | |||

| A | −0.066 | −5.467** | |||

| C | −0.079 | −6.543** | |||

| Positive MB | 0.136 | 11.343** | |||

| 4 | 516.708 | 0.068** | |||

| Sex | −0.034 | −2.976** | |||

| Age | −0.056 | −4.919** | |||

| Education | −0.082 | −7.144** | |||

| N | 0.215 | 18.811** | |||

| E | −0.075 | −6.563** | |||

| O | 0.024 | 2.095* | |||

| A | −0.044 | −3.808** | |||

| C | −0.066 | −5.763** | |||

| Positive MB | 0.007 | 0.620 | |||

| Negative MB | 0.260 | 22.731** | |||

| 5 | 2973.641 | 0.243** | |||

| Sex | −0.010 | −1.116 | |||

| Age | −0.016 | −1.720* | |||

| Education | −0.058 | −6.454** | |||

| N | 0.030 | 3.294** | |||

| E | −0.058 | −6.371** | |||

| O | −0.012 | −1.322 | |||

| A | −0.024 | −2.605** | |||

| C | −0.054 | −5.958** | |||

| Positive MB | −0.049 | −5.382** | |||

| Negative MB | 0.069 | 7.681** | |||

| CAS | 0.493 | 54.531** |

r, semipartial (part) correlation; N, neuroticism; E, extraversion; O, openness; A, agreeableness; C, conscientiousness; MB, metacognitive beliefs; CAS, metacognitive strategies.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Secondary Analyses

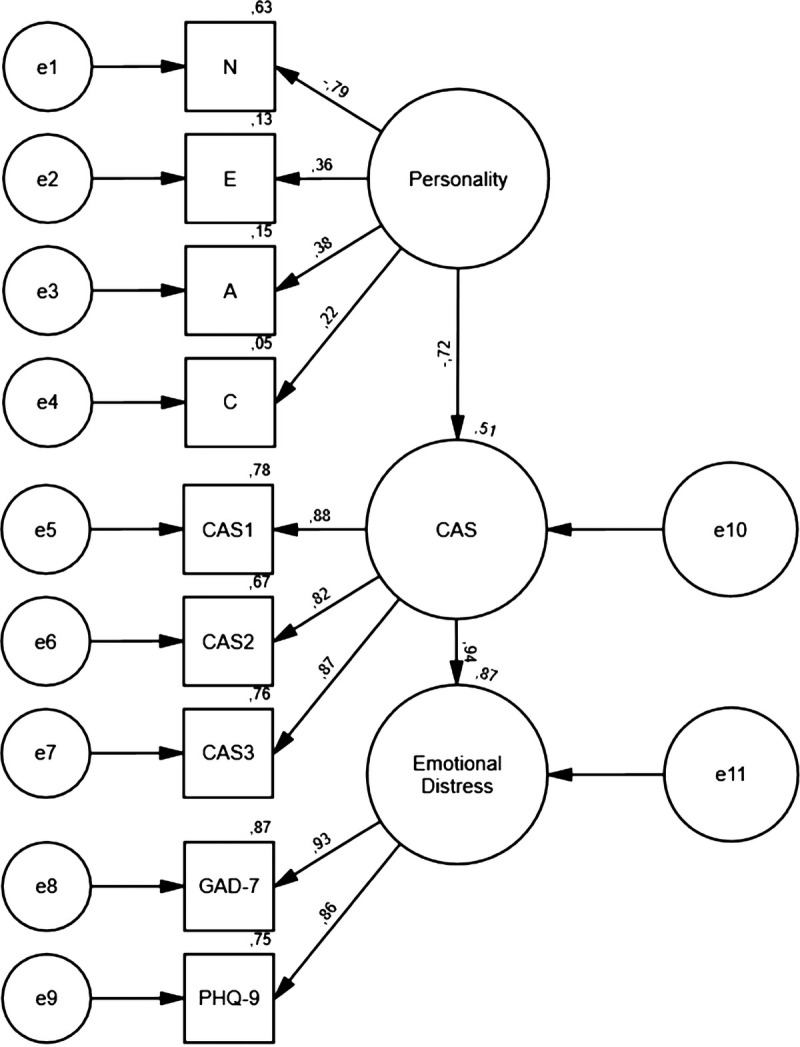

Structural equation modeling was conducted to test the fit of a metacognitive model. The model is presented in Figure 1 and showed the following fit indices: χ2(25) = 547.207, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.980, TLI = 0.971, RMSEA = 0.065 (90% CI, 0.060–0.070), SRMR = 0.031, indicating a good model fit to the data. The AIC value for the model was 605.207.

FIGURE 1.

Structural equation model of the metacognitive model (n = 4936). Circles represent latent variables, and rectangles represent observed variables (indicators). CAS1, worry/rumination; CAS2, threat monitoring; CAS3, maladaptive coping strategies; CAS4A-D, negative metacognitive beliefs.

The comparison model presented in Figure 2 where personality traits (all but openness) were used to specify a latent “personality” factor with the means to compare the metacognitive model showed the following fit indices: χ2(25) = 716.080, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.971, TLI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.075 (90% CI, 0.070–0.080), SRMR = 0.034, also indicating a good model fit to the data. The AIC value for the model was 774.198. The personality model showed a higher AIC value compared with the metacognitive model, indicating that the latter provided a better fit to the data.

FIGURE 2.

Structural equation model of the comparison model that included personality traits (n = 4936). Circles represent latent variables, and rectangles represent observed variables (indicators). CAS1, worry/rumination; CAS2, threat monitoring; CAS3, maladaptive coping strategies; N, neuroticism; E, extraversion; A, agreeableness; C, conscientiousness.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we set out to test the relative contribution of personality traits and metacognitive beliefs and strategies to anxiety and depression symptoms in a large sample during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway.

In terms of mean scores on anxiety and depression (mean = 6.63 for depression and 4.66 for anxiety), the current sample scored on average higher relative to a representative Scandinavian sample assessed before the pandemic (PHQ-9 = 3.59 [CI, 3.36–3.81] and GAD-7 = 3.70 [CI, 3.44–3.96]; Johansson et al., 2013), probably due to the threats associated with the ongoing pandemic and the nonpharmacological strategies aimed at impeding viral transmission chains (e.g., Campion et al., 2020). In terms of mean scores on metacognitive beliefs and strategies assessed with the CAS-1 (mean = 143.16 for positive beliefs, 112.43 for negative beliefs, and 13.35 for strategies), there is to the authors' knowledge only one Scandinavian prepandemic study that can be used as a reference point. Nordahl and Wells (2019) used convenience sampling with restricted knowledge about the participants and reported mean scores as follows (n = 773): 130.89 for positive beliefs, 146.98 for negative beliefs, and 21.10 for strategies. Face value comparison between the current sample and this one indicates that the current sample report lower mean scores for negative metacognitive beliefs and strategies, but higher scores for positive metacognitive beliefs. However, normative data for the CAS-1 have not been established so caution is warranted in comparing the samples on these scales.

All the personality traits and the metacognitive factors were significantly correlated with anxiety symptoms, but anxiety showed weak associations with extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and positive metacognitive beliefs. Furthermore, all personality traits and metacognitive factors were significantly correlated with depression symptoms except for openness, and depression showed weak correlations with extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and positive metacognitive beliefs.

In the regression models, we observed that female sex, lower age, and lower education level were unique and significant correlates of higher anxiety and depression symptoms. Personality traits entered as a block significantly accounted for variance in anxiety and depression symptoms, and neuroticism, openness, and agreeableness were unique and independent predictors of anxiety symptoms, whereas all the personality traits were unique and independent predictors of depression symptoms. On top of the demographics and personality traits, positive metacognitive beliefs accounted for additional variance in both types of distress, and negative metacognitive beliefs accounted for additional variance on top of positive metacognitive beliefs. Here we observed that entering negative metacognitive beliefs to the models lead positive metacognitive beliefs to be nonsignificant as an individual predictor of both anxiety and depression symptoms. Metacognitive strategies were entered last in both models and accounted for a substantial part of additional variance in both anxiety and depression symptoms on top of all the other predictors.

In the final equation when anxiety symptoms were used as the dependent variable, education level, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, positive metacognitive beliefs, negative metacognitive beliefs, and metacognitive strategies accounted for independent and unique variance. Education level, agreeableness, and positive metacognitive beliefs were negatively associated, whereas the others were positively associated with anxiety symptoms when the overlap among all the predictors was controlled. When depression symptoms were used as the dependent variable, age, education level, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, positive metacognitive beliefs, negative metacognitive beliefs, and metacognitive strategies accounted for independent and unique variance in the final equation. Age, education level, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and positive metacognitive beliefs were negatively associated, whereas the others were positively associated with depression symptoms when the overlap among all the predictors was controlled.

In line with previous studies, female sex, lower age, and lower education level were associated with higher distress levels (Daly et al., 2020; Ettman et al., 2020). Among these predictors, education levels showed a robust association with distress, whereas the association between symptoms and sex/age in large was accounted for by personality traits and metacognitive factors. Furthermore, neuroticism was the strongest predictor of anxiety and depression symptoms among the personality traits, and as expected, we observed that higher neuroticism was associated with higher distress levels. This observation is also in line with previous studies indicating that neuroticism is an important vulnerability factor underlying emotional distress (Kroencke et al., 2020; Lee and Crunk, 2022) and with studies indicating a role for other personality traits as well but to a lesser degree (Nikčević and Spada, 2020). Moreover, all the metacognitive factors accounted for additional variance on top of demographics and personality traits when entered on consecutive steps, and as expected, metacognitive strategies showed the strongest link with emotional distress symptoms. Adding negative metacognitive beliefs to the model lead positive metacognitive beliefs to be nonsignificant as a predictor, whereas negative metacognitive beliefs remained significant as a unique predictor when metacognitive strategies entered the model. In line with metacognitive theory (Wells, 2009), these observations suggest that the CAS and negative metacognitive beliefs are the most important influences on anxiety and depression symptoms among the metacognitive factors and are consistent with an earlier study reporting the same finding when social anxiety was used as the dependent variable (Nordahl and Wells, 2019). However, we observed that adding metacognitive strategies to the regression models in the final steps led positive metacognitive beliefs to become a significant and negative predictor of anxiety and depression. According to metacognitive theory (Wells, 2009), positive metacognitive beliefs are less relevant to distress and disorder compared with metacognitive strategies and negative metacognitive beliefs but should also be positively related to symptoms. In line with theory (Wells, 2009), positive metacognitive beliefs showed significant and positive bivariate correlations to anxiety and depression and was also a significant and positive predictor of distress before controlling negative metacognitive beliefs, indicating that our observations here are a result of interactions among the variables in the final equation and the outcomes in the two models as positive metacognitive beliefs and metacognitive strategies only show a moderate positive association, indicating that collinearity cannot account for this observation.

Our results from the regressions further suggest that metacognitive beliefs account for variance in emotional distress above personality traits. This finding is in line with a study showing that metacognitive beliefs accounted for variance in health anxiety above neuroticism (Bailey and Wells, 2013). In addition to previous research, we demonstrate that metacognitive strategies account for anxiety and depression symptoms even when controlling for personality traits and metacognitive beliefs, and that this state variable is by far the strongest associate of distress. This finding is in line with the metacognitive model of psychological disorder where metacognitive strategies is a transdiagnostic factor underlying different types and is considered the more proximal cause of distress (Wells and Matthews, 1994).

In the secondary analyses where we tested the structural relationships and the model fit of a basic metacognitive model, we found that the data fitted the model reasonably well, even when comparing it to an alternative model where personality was used as the underlying factor. The personality model also provided good model fit, but accounted for a slightly lower part of the variance in metacognitive strategies, and the overall model fit was not as good as for the metacognitive model. Thus, the metacognitive model provided the best fit to the data among these two.

It could be that dysfunctional metacognition can be considered lower-order dispositions and a function of higher-order personality traits. However, we did not test such a model as it is not consistent with the metacognitive theory where dysfunctional metacognition is considered the underlying mechanism in distress and vulnerability. Research indicates that there is a bidirectional relationship between metacognitions and “trait-anxiety” (closely linked to neuroticism) (Nordahl et al., 2019), that metacognition moderate the effect of emotional reactivity on anxiety (Clauss et al., 2020), and that metacognitive change is associated with changes in Big-5 personality traits (Kennair et al., 2021). Thus, it is an option that metacognition can be an underlying mechanism in vulnerability attributed to personality traits in personality theory. In addition, the concerns about personality dispositions not providing a framework of how they relate in a useful way to maladaptive self-regulation still stands (Claridge and Davis, 2001), whereas the metacognitive approach holds the advantage providing a model for these associations and a manual on how they can be effectively modified (Wells, 2009).

The implication from the present results is that emotional distress is most strongly related to metacognitive strategies, but also to personality traits (specifically neuroticism) and negative metacognitive beliefs. Formulations and interventions should therefore focus on metacognitive strategies as maintenance factors of distress, which from a statistical point of view based on the results from the current study can be seen as a result of personality traits and/or metacognitive beliefs. From a theoretical point of view, the metacognitive model holds the advantage of specifying metacognitive beliefs as a mechanism underlying the CAS and provides a means to which these factors can be effectively formulated within metacognitive theory and treated with metacognitive therapy (Wells, 2009), which have shown to effectively reduce emotional distress and maladaptive metacognitions (Normann and Morina, 2018).

There are several limitations that must be considered. Causal inferences cannot be made based on cross-sectional data. All variables were assessed with self-report, and we used cost-beneficial assessment tools. Some of the significant associations between the predictors and the outcome variables were of weak strength, and it is possible that a large sample size accounts for the significant relationships observed in these cases. These limitations show that there is a need to be cautious in generalizing from these findings. Further studies should assess the theorized relations between factors in longitudinal data, which may enable interference about the temporal and reciprocal relations among them, and there is a need to explore if personality traits and/or metacognitive factors play a role in the transition from distress to disorder. There is also a need to clarify the temporal and reciprocal relationships between personality traits (e.g., neuroticism) and metacognition with an aim to improve formulation of psychological vulnerability and preventive interventions.

In conclusion, the present study indicates a role for personality traits and metacognitive beliefs and strategies in emotional distress symptoms, with the strongest contribution from maladaptive metacognitive strategies. These can effectively be formulated and targeted within the metacognitive approach.

DISCLOSURE

The project was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (reference number: 125510) and registered with the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (reference number: 802810). Signed informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Omid V. Ebrahimi, Email: o.v.ebrahimi@psykologi.uio.no.

Asle Hoffart, Email: asle.hoffart@psykologi.uio.no.

Sverre Urnes Johnson, Email: s.u.johnson@psykologi.uio.no.

REFERENCES

- Akaike H. (1974) A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automatic Control. 19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Aschwanden D, Strickhouser JE, Sesker AA, Lee JH, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Terracciano A. (2020) Psychological and behavioural responses to coronavirus disease 2019: The role of personality. Eur J Pers. 35:51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey R, Wells A. (2013) Does metacognition make a unique contribution to health anxiety when controlling for neuroticism, illness cognition, and somatosensory amplification? J Cogn Psychother. 27:327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman RC, Ten Have M, de Graaf R, Muntingh AD, van Balkom AJ, Batelaan NM. (2019) Prevalence and course of subthreshold anxiety disorder in the general population: A three-year follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 247:105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. (1993) Alternative ways if assessing model fit. In Bollen KA, Long JS. (Eds), Testing structural equation models (pp 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Campion J, Javed A, Sartorius N, Marmot M. (2020) Addressing the public mental health challenge of COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 7:657–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chachamovich E, Fleck M, Laidlaw K, Power M. (2008) Impact of major depression and subsyndromal symptoms on quality of life and attitudes toward aging in an international sample of older adults. Gerontologist. 48:593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claridge G, Davis C. (2001) What's the use of neuroticism? Personal Individ Differ. 31:383–400. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss K, Bardeen JR, Thomas K, Benfer N. (2020) The interactive effect of emotional reactivity and maladaptive metacognitive beliefs on anxiety. Cognit Emot. 34:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. (1985) The NEO personality inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Sutin AR, Robinson E. (2020) Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear BF, Titov N, Sunderland M, McMillan D, Anderson T, Lorian C, Robinson E. (2011) Psychometric comparison of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for measuring response during treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 40:216–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi OV, Hoffart A, Johnson SU. (2021) Physical distancing and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Factors associated with psychological symptoms and adherence to pandemic mitigation strategies. Clin Psychol Sci. 9:489–506. [Google Scholar]

- Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. (2020) Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 3:e2019686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Birnbaum HG. (2005) The economic burden of depression in the US: Societal and patient perspectives. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 6:369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller H, Cramer H, Lauche R, Gass F, Dobos GJ. (2014) The prevalence and burden of subthreshold generalized anxiety disorder: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 14:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Bullmore E. (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 7:547–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NC, Newman MG. (2017) Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 143:1155–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson R, Carlbring P, Heedman Å, Paxling B, Andersson G. (2013) Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the Swedish general population: Point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ. 1:e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SU, Ulvenes PG, Øktedalen T, Hoffart A. (2019) Psychometric properties of the general anxiety disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample. Front Psychol. 10:1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennair LEO, Solem S, Hagen R, Havnen A, Nysæter TE, Hjemdal O. (2021) Change in personality traits and facets (revised NEO personality inventory) following metacognitive therapy or cognitive behaviour therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin Psychol Psychother. 28:872–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 62:593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, Watson D. (2010) Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 136:768–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroencke L, Geukes K, Utesch T, Kuper N, Back MD. (2020) Neuroticism and emotional risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Res Pers. 89:104038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. (2001) The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. (2010) The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 32:345–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SA, Crunk EA. (2022) Fear and psychopathology during the COVID-19 crisis: Neuroticism, hypochondriasis, reassurance-seeking, and coronaphobia as fear factors. Omega (Westport). 85:843–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. (2008) Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 46:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnúsdóttir I, Lovik A, Unnarsdóttir AB, McCartney D, Ask H, Kõiv K, Christoffersen LAN, Johnson SU, Hauksdóttir A, Fawns-Ritchie C, Helenius D, González-Hijón J, Lu L, Ebrahimi OV, Hoffart A, Porteous DJ, Fang F, Jakobsdóttir J, Lehto K, Andreassen OA, Pedersen OBV, Aspelund T, Valdimarsdóttir UA. (2022) Acute COVID-19 severity and mental health morbidity trajectories in patient populations of six nations: An observational study. Lancet Public Health. 7:e406–e416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. (2006) Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 3:e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K, Watson D. (2018) What lies beyond neuroticism? An examination of the unique contributions of social-cognitive vulnerabilities to internalizing disorders. Assessment. 25:143–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikčević AV, Spada MM. (2020) The COVID-19 anxiety syndrome scale: Development and psychometric properties. Psychiatry Res. 292:113322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordahl H, Hjemdal O, Hagen R, Nordahl HM, Wells A. (2019) What lies beneath trait-anxiety? Testing the self-regulatory executive function model of vulnerability. Front Psychol. 10:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordahl H, Wells A. (2019) Measuring the cognitive attentional syndrome associated with emotional distress: Psychometric properties of the CAS-1. Int J Cogn Ther. 12:292–306. [Google Scholar]

- Normann N, Morina N. (2018) The efficacy of metacognitive therapy: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 9:2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Kinley J, Afifi TO, Enns MW, Fawcett J, Sareen J. (2013) Subsyndromal depression in the United States: Prevalence, course, and risk for incident psychiatric outcomes. Psychol Med. 43:1401–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt B, John OP. (2007) Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. J Res Pers. 41:203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Saarni SI, Suvisaari J, Sintonen H, Pirkola S, Koskinen S, Aromaa A, Lönnqvist J. (2007) Impact of psychiatric disorders on health-related quality of life: General population survey. Br J Psychiatry. 190:326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim RS, Baltrus P, Ye J, Rust G. (2011) Prevalence, treatment, and control of depressive symptoms in the United States: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2005–2008. J Am Board Fam Med. 24:33–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 166:1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, Silove D. (2014) The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol. 43:476–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens GA Alkema L Black RE Boerma JT Collins GS Ezzati M, GATHER Working Group (2016) Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: The GATHER statement. PLoS Med. 13:e1002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. (2007) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 147:573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A. (2009) Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wells A. (2019) Breaking the cybernetic code: Understanding and treating the human metacognitive control system to enhance mental health. Front Psychol. 10:2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, Matthews G. (1994) Attention and emotion: A clinical perspective. Hove: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]