Abstract

Cognitive impairment, particularly deficits in executive function (EF) is common in Parkinson's disease (PD) and may lead to dementia. There are currently no effective treatments for cognitive impairment. Work from our lab and others has shown that physical exercise may improve motor performance in PD but its role in cognitive function remains poorly eludicated. In this study in a rodent model of PD, we sought to examine whether exercise improves cognitive processing and flexibility, important features of EF. Rats received 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the bilateral striatum (caudate-putamen, CPu), specifically the dorsomedial CPu, a brain region central to EF. Rats were exercised on motorized running wheels or horizontal treadmills for 6–12 weeks. EF-related behaviors including attention and processing, as well as flexibility (inhibition) were evaluated using either an operant 3-choice serial reaction time task (3-CSRT) with rule reversal (3-CSRT-R), or a T-maze task with reversal. Changes in striatal transcript expression of dopamine receptors (Drd1-4) and synaptic proteins (Synaptophysin, PSD-95) were separately examined following 4 weeks of exercise in a subset of rats. Exercise/Lesion rats showed a modest, yet significant improvement in processing-related response accuracy in the 3-CSRT-R and T-maze, as well as a significant improvement in cognitive flexibility as assessed by inhibitory aptitude in the 3-CSRT-R. By four weeks, exercise also elicited increased expression of Drd1, Drd3, Drd4, synaptophysin, and PSD-95 in the dorsomedial and dorsolateral CPu. Our results underscore the observation that exercise, in addition to improving motor function may benefit cognitive performance, specifically EF, and that early changes (by 4 weeks) in CPu dopamine modulation and synaptic connectivity may underlie these benefits.

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Cognitive impairment is common in Parkinson's disease (PD) but inadequately treated.

-

•

In a PD rat model, exercise improved cognitive flexibility and inhibitory aptitude.

-

•

Exercise also elicited increase in gene expression of striatal dopamine receptors.

Abbreviations:

- Actb

Actin-beta

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- AP

anterior-posterior

- BG

Basal ganglia

- CPu

Caudate putamen (striatum)

- DA

Dopamine

- DAR-D1-4

Dopamine receptors 1-4

- dlCPu

Dorsolateral striatum

- Dlg4

Gene coding for discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 4, also known as PSD-95

- dmCPu

Dorsomedial striatum

- Drd1-4

Genes for dopamine receptors 1-4

- DT

Dual task

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EF

Executive function

- Fisher's LSD

fisher's Least Significant Difference test

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- ITI

Intertrial interval

- L1-L3

3-CSRT learning levels 1-3

- L1R-L3R

3-CSRT-R reversal learning levels 1-3

- ML

Medial-lateral

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- NaOH

Sodium hydroxide

- ns

nonsignificant

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- PFA/PBS

Paraformaldehyde/phosphate buffered saline

- PSD-95

Postsynaptic density protein

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SNC

Substantia nigra compacta

- SNR

Substantia nigra reticulata

- Syp

Synaptophysin

- TH

Tyrosine hydroxylase

- TO

Time out

- vlCPu

Ventrolateral striatum

- vmCPu

Ventromedial striatum

- 3-CSRT

3-choice serial reaction time task

- 3-CSRT-R

3-choice serial reaction time task with reversal

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disorder that diminishes the quality of life in over 630,000 people in the USA, which is projected to double by year 2040 as our population ages (Dorsey et al., 2013; Kowal et al., 2013). An early non-motor feature of PD is cognitive impairment, particularly deficits in executive function (EF), which includes processing information and cognitive flexibility (e.g., set-shifting, reversal learning) (Dirnberger and Jahanshahi, 2013; Parker et al., 2013). In PD, deficits in the fronto-striatal circuit represent a common pathophysiology (Robbins and Cools, 2014). The importance of the striatum in EF, also termed the basal ganglia (BG) or caudate nucleus-putamen (CPu), is based on a large rodent and human literature (see review (Macdonald and Monchi, 2011)). For example, in individuals with PD, resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging, as well as positron emission tomographic neuroimaging, have demonstrated hypo-activation in a number of cortical and sub-cortical (basal ganglia) regions impacting the EF network (Kim et al., 2019; Apostolova et al., 2020; Stögbauer et al., 2020; Hirano, 2021).

Rodent studies have specifically implicated the role of the dorsomedial CPu (dmCPu) in EF, and its importance in set shifting and reversal learning (O'Neill and Brown, 2007; Baker and Ragozzino, 2014; Grospe et al., 2018), particularly when selection requires competing responses and discounting more salient stimuli (Cools, 2006; Thoma et al., 2008; Yehene et al., 2008; van Schouwenburg et al., 2010). It has been proposed that deficits in reversal learning may be due to prominent projection fibers to the dmCPu from the medial prefrontal cortex, including anterior cingulate and prelimbic cortices (Voorn et al., 2004), as well as a broader cortico-striatal-thalamic circuit (Chudasama et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2019). Although the pathophysiological changes in the dmCPu that underlie EF changes in PD are complex, loss of synaptic integrity, including synaptophysin and PSD95, and dopamine (DA) neurotransmission, including DA loss and altered DA receptor expression, are reported to have a certain contribution (Salame et al., 2016). Dopamine receptors, comprised of D1-like receptors (DAR-D1 and D5R), D2-like receptors (DAR-D2, DAR-D3, and DAR-D4) play a central role in learning and EF-related cognitive processing and flexibility (Wang et al., 2019; Sala-Bayo et al., 2020).

A public health priority is to identify cost-effective therapies to combat progressive cognitive impairment in PD, which is not addressed by current therapies (Burn et al., 2014). There is significant evidence utilizing short-term clinical studies showing that different types of exercise may improve motor performance in PD, including aerobic exercise (treadmill walking, cycling), resistance exercise (strength or weight training), balance training (yoga, stepping), and multifaceted exercise (Tai Chi, dancing) (Alberts et al., 2011; Intzandt et al., 2018). Fewer studies have examined the impact of exercise on long-term cognitive function in PD patients. Even less is known regarding the molecular underpinnings of exercise-related benefits in PD-related EF impairment. Indeed, the long-term effects of chronic exercise on cognition remains controversial (Sanders et al., 2020; Schootemeijer et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2021). There is a need for research into the causality of the relationship between physical activity, cognitive performance and insights regarding exercise-induced repair mechanisms. Using the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesioned model of PD, targeting specifically the dmCPu, this study sought to test the hypothesis that daily exercise improves EF-related cognitive processing and flexibility and that these benefits may be due to improved basal ganglia synaptic integrity and DA neurotransmission.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Wistar rats (male, 8–9 weeks of age) were purchased from Envigo Corporation (Placentia, CA, USA). Housing was under standard vivarium conditions in pairs on a 12-hr light/12-hr dark cycle (dark cycle 6 p.m. to 6 a.m.). All cages included a plastic pipe (10 cm diameter, 15 cm length) as an enrichment object. Rats had ad libitum access to food and water, except during food restriction as described in the behavioral studies. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Southern California, a facility approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, as well as by the Animal Use and Care Review Office of the US Department of the Army, and in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition, 2011.

2.2. Experimental design overview

Groups included 6-OHDA lesioned (Lesion) or naïve (Non-Lesion) rats. We originally chose the naïve rat control over the sham-lesioned control, as we felt that examining the exercise effects in ‘normals’ had greater relevance to clinical translation of the effects of exercise in normal human subjects. Rats underwent food restriction as described below, beginning 2 weeks after lesion surgery. Starting 2 weeks after lesion surgery, rats were subjected to exercise in motorized running wheels with either (i) a smooth surface (termed aerobic exercise), (ii) a complex motorized running wheel with alternating rungs removed, (iii) on a horizontal treadmill, or (iv) sedentary (non-exercise). The sections below detail the experimental approaches, including the cognitive testing (Fig. 1) using the operant 3-CSRT with rule reversal (Section 2.6, Experiment 1) and T-maze with rewarded matching-to-sample (Win-Stay) and reversal (Win-Shift) (Section 2.7., Experiment 2) to evaluate executive function, as well as a striatal transcript analysis for dopamine receptors (DAR-) D1 through D4 and the synaptic genes PSD-95 and synaptophysin (Section 2.8., Experiment 3).

Fig. 1.

Experimental protocol for operant training, T-maze, and exercise. (a) Timeline of experiments 1 and 2. (b) Protocol for the 3-choice serial reaction time task (3-CSRT) and reversal learning (3-CSRT-R). Gray shaded cells depict choices made by the rat. Black shaded cells depict consequences of those choices. Adapted from Asinof and Paine (2014) (Asinof and Paine, 2014). (c) Acquisition of the 3-CSRT and 3-CSRT-R. (d) Progressive training schedule.

2.3. Rat model of bilateral, dorsomedial striatal dopamine-depletion (Wang et al., 2020)

We targeted the dorsomedial quadrant of the striatum (dmCPu) as past work has shown that this region in rodents is critical for reversal learning (O'Neill and Brown, 2007; Baker and Ragozzino, 2014; Grospe et al., 2018), with alterations in the rostromedial striatum presumably resulting in deficits in frontostriatal processing (Voorn et al., 2004). In brief, rats received stereotaxic injection of 6-OHDA at 4 striatal injection sites (2 in each hemisphere) (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA, 10 μg/site dissolved in 2 μL of 0.1% L-ascorbic acid/saline, 0.4 μL/min) targeting the bilateral dmCPu (AP: + 1.5 mm, ML: ± 2.2 mm, DV: 5.2 mm, and AP: + 0.3 mm, ML: ± 2.8 mm, DV: 5.0 mm, relative to bregma), which is the primary striatal sector targeted by the medial prefrontal cortex (Voorn et al., 2004) and critical for flexible shifting responses (O'Neill and Brown, 2007; Baker and Ragozzino, 2014; Tait et al., 2017; Grospe et al., 2018). After injection, the needle was left in place for 5 min before being slowly retracted (1 mm/min). Non-Lesion rats were used for controls. To prevent noradrenergic effects of the toxin, rats received desipramine (Sigma Aldrich, 25 mg/kg i.p.) before surgery (Roberts et al., 1975). Carprofen (2 mg in 5 g tablet, p. o., Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ, USA) was administered for one day preoperatively and for two days postoperatively for analgesia. Exercise was initiated 2 weeks thereafter when lesion maturation was complete (Sauer and Oertel, 1994; Yuan et al., 2005). To verify the striatal target of 6-OHDA lesion, brains from a subset of rats were collected for immunohistochemical staining for tyrosine hydroxylase protein and HPLC analysis of DA.

2.3.1. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunostaining

TH immunostaining data were collected as previously reported and described quantitatively from lesioned and non-lesioned rats (Wang et al., 2020). Rats were anesthetized, subjected to transcardial perfusion with ice-cold saline followed by ice-cold 4% PFA/PBS. Brains were removed, transferred to the same fixative for 24 h, immersed in 20% sucrose for 48 h, frozen and cryo-sectioned at 25 μm thickness throughout the entire anterior-posterior extent of the brain. Selective sections spanning the 6-OHDA lesion in both the striatum and midbrain were subjected to TH-immunostaining using a primary antibody solution (1:2500 anti-tyrosine hydroxylase, Cat #AB152, Millipore-Sigma, Billerica, MA, USA), then visualized using a secondary antibody solution (1:5000 IRDye 800CW Goat anti-mouse Cat #926–3221, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). Images of tissues at the levels of the striatum representing the site of the 6-OHDA lesioning targeting the dmCPu and mid-ventral mesencephalon showing the midbrain dopaminergic neurons were obtained using a LI-COR Odyssey CLx (for internal landmarks, please see (Wang et al., 2020)).

2.3.2. HPLC analysis of striatal dopamine

Neurotransmitter concentrations in experiments 1 and 2 were determined according to an adaptation of Mayer and Shoup (1983) (Mayer and Shoup, 1983). Striatal tissue sections were dissected and immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Tissues were sampled from coronal sections spanning bregma AP +2.00 to 0.00 mm, including tissue bordered ventrally by the anterior commissure, dorsally by the corpus callosum, medially by the lateral ventricle, and ±5.0 mm laterally from the midline) (Kintz et al., 2013; Lundquist et al., 2019). Striatal blocks were further sub-dissected to four quadrants, using the dorsal-ventral and medial-lateral divisions detailed previously (Voorn et al., 2004) to collect tissue from the dorsomedial striatum (dmCPu), dorsolateral striatum (dlCPu), ventromedial (vmCPu), and ventrolateral quadrants (vlCPu). For analysis, tissues were homogenized in 0.4 N perchloric acid, proteins were separated by centrifugation, and the supernatant used for HPLC analysis by electrochemical detection on an ESA HPLC system (ESA, Chelmsford, MA, USA) consisting of an ESA Model 582 pump, ESA Model 542 autosampler, ESA Model 5600 Detector and separation column (MD-150 × 3.2 mm). Data analysis employed the CoulArray for Window Application program (ESA Biosciences, Chelmsford, MA, USA). The protein pellet was resuspended in 0.5 N NaOH and total protein concentration determined using the BCA detection method (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Striatal DA was expressed as nanograms DA per milligram protein.

2.4. Food restriction

Food restriction was started 2 weeks after surgery and maintained throughout the 3-CSRT (Experiment 1) and T-maze (Experiment 2) behavioral studies. Rats were brought to 85% of their baseline body weight in one week and allowed to gain 5 g in body weight per week thereafter, with ad libitum access to water. Rats were fed between behavioral testing that took place in the morning and exercise that took place in the afternoon. Body weights were recorded Monday-Friday, with meal size individually adjusted on a daily basis, including weekends.

2.5. Exercise on running wheels and treadmill

2.5.1. Exercise on complex or smooth running wheels

Rats assigned to the skilled exercise group were trained in enclosed, motorized, running wheels (35.6 cm diameter, Lafayette Instrument, Lafayette, IN, USA) with irregularly spaced rungs, termed ‘complex’ running wheel, which demand the constant adaptation of stride length. A pseudo random pattern of rung spacing was achieved by repeating a pattern OOOOXOX, where O indicates a rung, and X a missing rung, resulting in inter-rung distance of either 1.3 or 2.6 cm). Exercise was initiated 2 weeks after lesion surgery using our prior methods (Wang et al., 2015a, Wang et al., 2015b) and lasted a total of 30 min/day (4 bouts, 5 min/bout, 2-min inter-bout interval), 5 consecutive days/week (Mon - Fri). Starting time point was based on published literature reporting that bilateral striatal 6-OHDA lesions elicits TH losses at the level of the SN that reaches a plateau after 2 weeks (Yuan et al., 2005; Blandini et al., 2007), with DA losses plateauing at 2 weeks (Ben et al., 1999), and with nigral cell losses variably reported as plateauing (Yuan et al., 2005) or decreasing thereafter to 4 weeks post-injury (Blandini et al., 2007). Rats were subjected to 1 week of individually adjusted, performance-based speed adaptation to reach a plateau speed of 5 m/min, a speed achievable by most 6-OHDA lesioned rats in the complex wheel following 1 week of exercise (Wang et al., 2013, 2015). Titration of speed has been described in detail in our prior publication (Wang et al., 2013). Non-Exercise rats were left in a stationary running wheel for 30 min/day. Running speeds for the Non-Lesion, control rats were matched to speeds achievable by lesion rats in the complex wheel (5 m/min maximum). An additional group of lesion rats was trained in motorized running wheels identical to those described above, except that these wheels had regularly placed rungs and an inner plastic ‘smooth’ floor covering the metal rungs and were termed ‘smooth’ running wheel as previously reported (Wang et al., 2013, 2015). The modification made foot placement easier for lesioned rats, and therefore minimized the ‘motor skill’ factor. Speeds for the smooth running wheels were matched to those of the complex running wheels.

2.5.2. Exercise training on horizontal treadmill

A separate group of rats were trained on a motorized, 10-lane horizontal treadmill (lane width 10 cm, length 94 cm, wall height 20 cm, custom made) for 65 min a day, 5 days per week (Mon - Fri) starting two weeks after stereotaxic surgery. Each exercise session consisted of a 15-min warm-up, 15-min running, 5-min break, 15-min running, and 15-min cool-down. The warm-up and cool-down speed started at 4 m/min and went up to 10 m/min by 2 weeks, while the running speed started at 6 m/min and went up to 30 m/min in 4 weeks. The rats were exercised at 10 and 30 m/min for the remaining 10 weeks. A researcher prompted the rats to stay on the treadmill and run by lightly brushing the rear end of any rat that fell back with a brush. After several days of exercise, rats typically will stay on the treadmill running.

2.6. Operant training

2.6.1. Groups

In Experiment 1, rats with bilateral, dmCPu 6-OHDA lesions were exposed to exercise in either: (i) motorized, complex running wheel (Lesion/Complex Wheel, n = 12), (ii) motorized smooth running wheel (Lesion/Smooth Wheel, n = 4), or (iii) motorized horizontal treadmill (Lesion/Treadmill, n = 6). The control group of rats included 6-OHDA lesion, non-exercise rats (Lesion/Non-Exercise, n = 12) or Non-Lesion, non-exercise rats (Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise, n = 12). The Non-Lesion group consisted of both non-exercise (n = 6) and complex running wheel (n = 6) and since they showed no significant differences in operant training outcomes they were pooled (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Whereas in our original design sample size was balanced across all groups to access modality-specific effects of exercise, we were not able to complete all experiments due to local restrictions and university-mandated euthanasia of rats during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. These rats were excluded from analysis. Because preliminary analysis showed the exercise effects to be modest (Supplementary Fig. S2), we pooled the three exercise groups to form a single Lesion/Exercise group (n = 22) in this report.

2.6.2. Three-choice serial reaction time nose-poke task with reversal (Fig. 1)

We chose a 3-CSRT paradigm with an added rule reversal feature, called 3-CSRT-reversal (3-CSRT-R), to examine cognitive flexibility. Detailed methods are provided in our prior publication (Wang et al., 2020). In brief, rats were food restricted and randomized to receive complex wheel exercise, simple wheel exercise, treadmill exercise, or no exercise. Exercise was initiated 1 week prior to operant training, during which time they were handled on a daily basis and given 5 sucrose pellets per day in their home cage (45 mg/pellet, chocolate flavor, #F0025, Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ, USA). Exercise was continued for 12 weeks. Each modular test chamber (MedAssociates, St. Albans, VT, USA) was housed in a sound attenuating cubicle, and consisted of grid floor, house light, 3-bay nose-poke wall, pellet trough receptacle, receptacle light, head entry detector, and a PC-controlled smart controller. Rats were trained to associate nose poking into an illuminated aperture with receiving a single sucrose pellet reward. Rats were familiarized with the test chamber and nose-poke and reward retrieval behavior were shaped in pretraining lasting 1 week as previously described (Wang et al., 2020). Thereafter, during the regular phase of 3-CSRT training, the rats were trained following a progressive schedule with a fixed ratio 1 schedule response-reward task (up to 90 trials or 30 min each session per day, 5 days/week, 16 sessions). The walls, nose-poke apertures, food receptacle, and grid floor were wiped with 70% isopropyl alcohol between rats.

For each trial, the light stimulus was turned on in a pseudo-randomly chosen nose-poke aperture (Fig. 1b). The stimulus stayed on for a set duration or until a nose-poke (correct or incorrect) was detected. The rat received a food reward following a correct nose-poke within the set limited hold duration, which was set to be the same as the stimulus duration or slightly longer for short stimulus durations. Following reward retrieval and a 2-s intertrial interval (ITI), the next trial was started. If an incorrect nose-poke was detected, the rat received a 2-s time out (TO), during which the chamber light was turned off. If no nose-poke was detected within the limited hold duration, an omission was recorded, with a 2-s TO. After each TO, the chamber light was turned on, and after a 2-s ITI, the next trial was started. If a nose-poke was detected during the ITI, a premature response was recorded without incrementing the trial number, and the rat received a 2-s TO. Any nose-pokes following a correct response and before reward retrieval were recorded as repetitive responses. Rats were trained through 3 difficulty levels with progressively shortened stimulus durations. We chose to control the number of training days for each level across rats to facilitate between-group comparison. This was selected based on our prior work showing that lesion rats can reach a performance level comparable to that of Non-Lesion rats at this difficulty level (Wang et al., 2020). Differences in reversal learning can thus be interpreted as differences in cognitive flexibility, rather than differences based on incomplete learning. The final stimulus duration was set at 5 s, reflecting a moderate level of difficulty.

During the rule-reversal phase of 3-CSRT-R training (Fig. 1c), the stimulus was switched from a lit aperture among dark apertures to a dark aperture among lit apertures. The animal was trained progressively to learn to nose-poke the dark aperture to receive reward (25 sessions, 1 session/day, 5 days/week).

For 3-CSRT and 3-CSRT-R the following behaviors were captured (Asinof and Paine, 2014): (i) nose-poke accuracy = (number of correct responses)/(number of correct + number of incorrect responses) * 100%, a primary measure of operant learning; to account for modest differences in 3-CSRT acquisition, we normalized nose-poke accuracy during the reversal phase by accuracy at the end of acquisition (L3, Day 10, Fig. 3); (ii) number of omissions, a measure of attention; (iii) premature responses, a measure of impulsivity and response inhibition, (iv) correct nose-poke latency = average time from onset of stimulus to a correct response, a measure of attention and cognitive processing speed; and (v) reward retrieval latency = average time from correct response to retrieval of sugar pellet, a measure of motivation.

Fig. 3.

Effects of exercise and lesion on the 3-choice serial reaction time task (3-CSRT) acquisition and reversal learning (3-CSRT-R). Shown are group mean ± SEM of (a) normalized nose-poke accuracy, (b) premature responses, (c) omissions, (d) correct nose-poke latency, and (e) reward retrieval latency for Non-Lesion (n = 12), Lesion/Non-Exercise (n = 12) and Lesion/Exercise group (n = 22). Results show that exercise elicits a significant, modest improvement in response accuracy in the 3-CSRT-R, as well as a robust improvement in inhibitory aptitude in the 3-CSRT-R in lesioned rats. #: p < 0.05 Lesion/Exercise vs. Lesion/Non-Exercise; +: p < 0.05 Lesion/Non-Exercise vs. Non-Lesion, Fisher's LSD multiple comparisons test. Data were also analyzed with two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (results listed in Supplementary Table S1). The Non-Lesion group consisted of both non-exercise (n = 6) and complex running wheel (n = 6), and since they showed no significant differences in operant training outcomes they were pooled (Supplementary Fig. S1).

2.7. T-maze

2.7.1. Groups

In Experiment 2, rats (n = 7) with 6-OHDA lesions were exercised for 6 ½ weeks in the complex wheel. Controls included lesion, non-exercise rats (Lesion/Non-Exercise, n = 6), and Non-Lesion, non-exercise controls (Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise, n = 9).

2.7.2. T-maze with rewarded matching-to-Sample and reversal

Cognition testing of EF in rats was adapted from methods from our work (Stefanko et al., 2017) and that of others (Deacon and Rawlins, 2006). Rats were food restricted and randomized to exercise in the complex wheel or non-exercise. One week prior to T-maze training, rats were handled on a daily basis and given 5 dustless, chocolate-flavored sucrose pellets per day in their home cage (45 mg/pellet, #F0025, Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ, USA). The T-maze was constructed as a cross maze of black, opaque Plexiglas. Arms (15.2 cm width, 50.8 cm length, 35.2 cm height) could be sealed off by guillotine doors (15.2 cm width x 35.2 cm height) to prevent entry to an enclosed central platform (15.2 cm width, 15.2 cm length, 35.2 cm height). Two opposing arms were designated as the branch arms, with one of the remaining two arms randomized to be designated the stem arm with its opposite arm sealed during the ‘T-maze’ testing. A partition extended across the central platform and 6.4 cm into the chosen stem arm, allowing entry into either of the open branch arms. Arm entry was defined as having all four paws in the arm. If a rat failed to mobilize within 90 s, it was removed from the maze, to be exposed again 10 min later. Uneaten sucrose pellets and fecal pellets were removed from the maze between trials, and the maze wiped with 70% isopropyl alcohol solution.

T-Maze acclimatization occurred over 3 days during which time rats were allowed to explore the maze. Initially the floor of the maze was baited with individual sucrose pellets, followed by baiting of both maze arms, followed by baiting of both food cups. Rats were trained for 3 days in a forced trial paradigm, in which food reward was available only in one arm (randomized), with the other branch arm blocked (10 trials with a 5-s intertrial interval in the morning and again in the afternoon). Thereafter, they were trained in a ‘Win-Stay’ paradigm (sample run→choice trial, 10 trials twice per day, 5-s intertrial interval, x 20 days), in which rats had to choose the same arm during a choice trial (both arms open) that had previously been rewarded on the preceding sample trial (one arm closed). Sample trials were randomized across both arms. Thereafter, during implementation of a rule reversal, rats were exposed to a ‘Win-Shift’ strategy, in which the rat was only rewarded in the choice run if it entered the branch arm opposite the one chosen in the sample run (sample run→choice trial, 10 sequences twice per day, 5-s intertrial interval, x 13 days). The number of correct entries into the bated choice arm were recorded for each trial.

2.8. Quantitative RT-PCR for striatal dopamine receptor and synaptic gene expression

In Experiment 3, two additional groups of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats were exercised in the complex running wheel (Lesion/Complex Wheel, n = 6) or smooth running wheel (Lesion/Smooth Wheel, n = 6) for 4 weeks before being euthanized for transcript analysis. Since there were no statistically significant differences in gene expression between the Smooth wheel and the Complex wheel groups, the gene expression data from the two exercise modalities were pooled to form a single composite Exercise group (n = 12), similar to the approach in Experiment 1. Final group analyses included Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise (n = 6), Lesion/Non-Exercise (n = 6), and Lesion/Exercise (n = 12). The pattern of expression of several genes including Syp (synaptophysin, Gene ID 24804), Dlg4 (discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 4, also known as PSD95, Gene ID 29495), Drd1 (DAR-D1, Gene ID 24316), Drd2 (DAR-D2, Gene ID 24318), Drd3 (DAR-D3, Gene ID 29238), and Drd4 (DAR-D4, Gene ID 25432) were examined. Immediately after the final exercise session, rats were sacrificed via decapitation and whole brains were extracted. Fresh tissue was rapidly micro-dissected in blocks from the CPu (dmCPu, dlCPu, vmCPu, vlCPu as described in section 2.3.2). Tissues were submerged in an RNA stabilization solution (pH 5.2) at 4 °C, containing in mM: 3.53 ammonium sulfate, 16.66 sodium citrate, and 13.33 EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), transferred to a sterile tube containing 300 μl TRI-reagent (Cat. No. 11–330T, Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA), and homogenized with a mechanical pestle before centrifuging at 13,000×g for 3 min. Supernatant was removed to a new tube and 250 μl of chloroform was added and tubes vigorously shaken twice for 10 s, followed by 3 min of rest on ice and centrifugation at 13,000×g for 18 min at 4 °C. The upper aqueous layer was carefully removed to a new tube, an equal volume of 100% ethanol was added, and the sample was thoroughly mixed before RNA purification using the Zymo Direct-zol RNA Miniprep (Cat. No. 11–330, Genesee Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was eluted in 35 μl of DNAse/RNAse free water before spectrophotometric analysis of RNA purity and concentration. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg isolated RNA using the qPCRBIO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Cat. No. PB30.11–10, PCR Biosystems, Wayne, PA, USA) following manufacturer's guidelines before being diluted 1:5 in DNAse/RNAse free water and stored at −20 °C. Gene expression changes were measured with quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) as previously described (Lundquist et al., 2019, 2021). Briefly, qRT-PCR was run with 2 μl of cDNA and qPCRBIO SyGreen master mix (Cat. No. PB20.11–01, PCR Biosystems) on an Eppendorf Mastercycler Ep Realplex (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY, USA) using a program of 15 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C. Data was collected and normalized on Eppendorf Realplex ep software. Standard delta-CT analysis (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) was used to quantify fold changes in gene expression in experimental groups normalized to controls, with beta-actin serving as a housekeeping gene. Primer oligonucleotide pairs are listed in Supplementary Table S7.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. and analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.3.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.9.1. 3-CSRT/3-CSRT-R

3-CSRT data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures for each training level, with lesion and time, or exercise and time as the factors, and with Fisher's LSD multiple comparisons test comparing groups for individual training session. In addition, to control for any possible subtle lesion-related deficits in motor and cognitive functions at the end of the 3-CSRT acquisition phase, we also examined a normalized nose-poke accuracy in which the group average of accuracies during the 3-CSRT-R were normalized by the group mean accuracy on the final day of regular training (L3 of 3-CSRT). All statistical test results for main effect of lesion and exercise are included in Supplementary Table S1.

2.9.2. T-maze with reversal

The lesion effect was analyzed by a mixed model with repeated measures in 'time' and main effect being ‘lesion’ (p < 0.05). Accuracy in the Win-Stay and Win-Shift paradigms was separately analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures in ‘time’ and main effect being ‘exercise’ (p < 0.05). Performance was evaluated as: (i) percent of correct responses per session during initial learning (Win-Stay) and reversal learning (Win-Shift); (ii) the number of trials an individual rat required to reach the learning criterion during the reversal phase, defined as 9 out of 10 correct choices in consecutive trials; and (iii) perseverative or regressive errors made during the reversal learning phase. Perseverative and regressive errors were defined, respectively, as the number of incorrect choices made until or after the rat chose the correct arm for 5 consecutive trials. Perseverative and regressive errors during the Win-Shift phase were separately analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures in ‘time’, and main effect either being ‘lesion’ or ‘exercise’ (p < 0.05). Fisher's LSD multiple comparisons tests were used to compare groups for individual days.

2.9.3. Transcript and HPLC analysis

All statistical tests were carried out and graphs made in Prism 9.1 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. No sample size calculations were performed prior to the start of the study but are based on previous publications. Unpaired, two-tailed T-tests were used for all qRT-PCR analysis between control and pooled exercise groups (smooth wheel, complex wheel). One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons was used for analysis of gene expression across exercise groups (non-exercise, exercise). Statistical analysis for HPLC data was carried out by using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's posttest comparing saline (control) treatment with 6-OHDA-lesioned groups. All statistical test results are included in Supplementary Tables S3–7.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of 6-OHDA-lesioning on tyrosine hydroxylase expression and dopamine levels

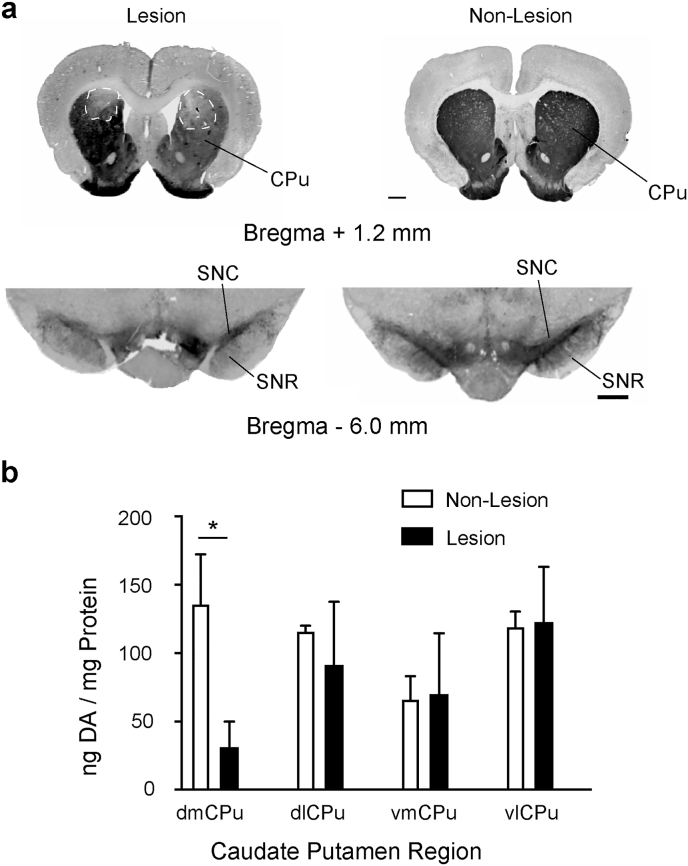

Analysis of TH immunoreactivity demonstrated a significant reduction in TH immunostaining in the dmCPU (the stereotactic target of 6-OHDA) in lesioned rats compared to Non-Lesion rats (Fig. 2a). There were no significant differences in the dlCPu, vmCPu, and vlCPu of lesioned compared to Non-Lesion rats. Examination of TH immunostaining in the midbrain showed reduced staining of the substantia nigra from 6-OHDA-lesioned rats compared to Non-Lesion rats. Analysis of DA levels by HPLC showed a significant difference in only the dmCPu quadrant, the region targeted for stereotaxic delivery of 6-OHDA, compared to Non-Lesion rats (31.2 ± 18.7 ng vs. 136.1 ± 36.1 DA/mg Protein, p < 0.05). All other quadrants of CPu tissues did not show a statistically significant difference comparing Non-Lesion with lesioned tissue quadrants (Fig. 2b). These results show that lesions were limited to the dmCPu quadrant, with retrograde bilateral dopaminergic cell losses also apparent at the level of the substantia nigra.

Fig. 2.

Immunostaining for tyrosine hydroxylase to determine the degree and anatomical site of lesion. (a) Representative images of coronal sections reveal bilateral loss in tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the dorsomedial striatum (bregma AP +1.20 mm anterior to bregma) and midbrain showing immunostaining of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNC) and substantia nigra reticulata (SNR, bregma AP -6.0 mm). Scale bar = 0.5 mm. (b) HPLC analysis of striatal DA from tissues collected from coronal slice (bregma AP +2.00 to 0.00 mm) from Non-Lesion and Lesion rats in striatal tissue quadrants (dorsomedial dmCPu, dorsolateral dlCPu, ventromedial vmCPu, and ventrolateral vlCPu).

3.2. Experiment 1: Effect of lesion and of exercise on operant training (3-CSRT/3-CSRT-R)

3.2.1. Lesion effects

During the acquisition phase of 3-CSRT (Levels L1, L2, L3), Lesion/Non-Exercise rats compared to Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise showed: (i) statistically significant lower nose-poke accuracy (Supplementary Fig. S2a p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA repeated measures that diminished towards the end of L3 (L3 Day 10: Lesion/Non-Exercise 83.77 ± 2.05% vs. Non-Lesion 91.41 ± 1.10%); (ii) no differences in the number of premature responses (p > 0.05. Fig. 3b); (iii) significantly higher number of omissions in L2 and L3 (p < 0.05. Fig. 3c); (iv) significantly greater correct nose-poke latency (∼0.6 s, p < 0.005. Fig. 3d); and (v) significantly greater reward retrieval latency (∼0.6 s, p < 0.001. Fig. 3e). See Supplementary Table S1 for F and p values.

A reversal was introduced to evaluate cognitive flexibility. At the start of 3-CSRT-R, when the rule for correct (rewarded) response was switched from nose-poking a lit aperture to nose-poking a dark aperture, both Lesion/Non-Exercise and Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise rats showed a sudden drop in performance with decreased nose-poke accuracy to the same extent, increased correct nose-poke latency, and increased premature responses. Both groups showed improvement in these parameters with continued training. Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise improved nose-poke accuracy rapidly to a plateau of about 75% (L3R Day 10, 76.55 ± 3.21%), while Lesion/Non-Exercise rats only improved accuracy modestly to a plateau of about 40% (L3R Day 10, 43.69 ± 2.95%). Lesion/Non-Exercise rats compared to Non-Lesion controls showed: (i) statistically significant lower nose-poke accuracy (p < 0.001. Supplementary Fig. S2a); (ii) significantly higher number of premature responses in L3R (p = 0.0088. Fig. 3b); (iii) significantly higher number of omissions in phases L2R and L3R (p < 0.05. Fig. 3c); (iv) no differences in correct nose-poke latency (p > 0.05. Fig. 3d); and (v) significantly greater reward retrieval latency (∼0.5 s, p < 0.05. Fig. 3e).

3.2.2. Exercise effects

Lesion/Complex Wheel, Lesion/Smooth Wheel, and Lesion/Treadmill rats showed similar outcomes in the 3-CSRT task (Supplementary Fig. S2) and were pooled to form a Lesion/Exercise group (n = 22). Lesion/Exercise compared to Lesion/Non-Exercise rats showed a statistically significant lower number of premature responses during the reversal phase L3R (p = 0.018. Fig. 3b). To account for modest differences in 3-CSRT acquisition, we normalized nose-poke accuracy during the reversal phase by accuracy at the end of acquisition (L3, Day 10). Lesion/Exercise rats showed significantly higher normalized nose-poke accuracy in all reversal levels (p < 0.05. Fig. 3a). There were no differences in omission, correct nose-poke latency, and reward retrieval latency between the two groups (Fig. 3c–e).

3.3. Experiment 2: Effect of exercise on T-maze task with reversal

To examine the effect of dmCPu 6-OHDA lesion and exercise on cognitive flexibility, behavior in the T-Maze with reversal was tested. The groups examined were Lesion/Non-Exercise, Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise, and Lesion/Complex Wheel. During the Win-Stay phase, there was a significant effect of lesion (F1,13 = 13.47, p = 0.0028) and a lesion × time interaction (F19,217 = 3.34, p < 0.0001) in response accuracy (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table S2). Exercise improved accuracy in lesioned rats (F1,11 = 8.063, p = 0.016), without exercise × time interaction. During the rule reversal Win-Shift phase, there were significant effects of lesion (F1,13 = 41.83, p < 0.0001) and lesion × time interaction (F12,142 = 4.76, p < 0.0001. Fig. 4b). Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise compared to Lesion/Non-Exercise rats reached the learning criterion significantly earlier (p < 0.00001. Fig. 4c) and showed fewer perseverative errors (F1,13 = 4.69, p < 0.05. Fig. 4d) and fewer regressive errors (F1,13 = 6.76, p < 0.05. Fig. 4e). During the Win-Shift phase, there was a significant effect of exercise (F1, 11 = 15.57, p = 0.0023. Fig. 4b), but no significant exercise × time interaction. Lesion/Complex wheel compared to Lesion/Non-Exercise rats reached the learning criterion significantly earlier (p < 0.002. Fig. 4c) and showed fewer perseverative errors (F1,11 = 7.29, p < 0.02. Fig. 4d), with no significant differences in regressive errors (Fig. 4e). In summary, the T-maze detected a clear significant lesion effect during in the Win-Stay paradigm, a significant difference that was accentuated during the Win-Shift phase. Lesion rats that underwent complex wheel exercise showed a greater number of correct responses compared with Non-Exercise rats. This effect showed a significant difference during the Win-Stay phase and was accentuated during the Win-Shift phase of training.

Fig. 4.

Effects of lesion and exercise on T-maze learning of rewarded matching-to-sample (Win-Stay) followed by reversal (Win-Shift). (a) Rats were trained in a Win-Stay strategy (solid line arrow = sample trial; dashed line arrow = choice trial) for 20 days, followed by training in (b) Win-Shift strategy for an additional 13 days. Response accuracy (percentage of correct responses) is shown for Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise (n = 9), Lesion/Complex wheel (n = 7) and Lesion/Non-Exercise (n = 6). (c) Total number of incorrect trials performed until criterion (9 correct responses in 10 consecutive trials) was reached during the Win-Shift phase. (d) Perseverative errors during the Win-Shift phase. (e) Regressive errors during the Win-Shift phase. Mean ± SEM. Exercise improves response accuracy in the T-maze, shortens time until learning, while diminishing perseverative errors following rule reversal (Win-Shift phase). #: p < 0.05 Lesion/Complex wheel vs. Lesion/Non-Exercise; +: p < 0.05 Lesion/Non-Exercise vs. Non-Lesion/Non-Exercise, Fisher's LSD multiple comparisons test. *: p < 0.0002, **: p < 0.001 (Student's t-test).

3.4. Transcript analysis

Following 6-OHDA lesioning of the dmCPu, the effects of 4 weeks of different exercise modalities – aerobic running in a smooth wheel, or skilled running in a complex wheel with irregularly spaced rungs – on synaptic plasticity (Syp, Dlg4) and DAR receptor gene (Drd1, Drd2, Drd3, Drd4) expression were examined in four quadrants of the striatum using qRT-PCR. There were no statistically significant differences in gene expression between exercise in the Smooth or Complex Running Wheel groups (Supplementary Fig. S3, Tables S3–S6). Therefore, gene expression data from the two exercise modalities were pooled to form a composite Exercise group, in parallel with the approach in Experiment 1 of the behavioral studies. Final group analyses included Non-lesion/Non-Exercise (n = 6), Lesion/Non-Exercise (n = 6), and Lesion/Exercise (n = 12) (Fig. 5). In the dmCPu, there were significant group differences in Dlg4 (F(2,21) = 4.61, P = 0.02) and Drd1 (F(2,21) = 10.07, p < 0.001), Drd3 (F(2,21) = 10.07, P = 0.004), and Drd4 (F(2,21) = 3.69, P = 0.04) but no significant group differences in Syp (F(2,21) = 2.35, P = 0.12) or Drd2 (F(2,21) = 0.73, P = 0.49). Post hoc analysis showed a significant lesion effect on Dlg4 (PSD-95, P = 0.04) and an exercise effect on transcript expression of Dlg4 (P = 0.03), Drd1 (p < 0.001), Drd3 (p < 0.005), and Drd4 (P = 0.046) (Fig. 5a). In the dlCPu, there was a significant group difference only in Dlg4 (F(2,21) = 16.57, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis showed a significant lesion effect on transcript expression of Dlg4 (P = 0.001) and an exercise effect (P = 0.001). (Fig. 5b). In the ventral quadrants of the striatum (vmCPu, vlCPu), there was no statistically significant group difference in transcript expression of Syp, Dlg4, and Drd1, Drd2, Drd3, and Drd4. A complete list of statistical test results can be found in Supplementary Tables S1–S4.

Fig. 5.

Dopaminergic signaling and synaptogenic gene expression changes across caudate putamen quadrants following exercise in Lesion rats. Rat caudate putamen was divided into four quadrants for transcript analysis: (a) dorsomedial (dmCPu), (b) dorsolateral (dlCPu), (c) ventromedial (vmCPu), and (d) ventrolateral (vlCPu). Corresponding gene expression changes for four DA receptor (Drd1, Drd2, Drd3, Drd4) and two synaptic (Syp, Dlg4) genes in the exercise group (pooled complex and smooth wheel running, n = 12) compared to Non-Exercise controls (n = 6). Mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 relative to Non-Exercise control (Student's t-test), ns nonsignificant.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of lesions and exercise on cognitive outcomes

Although the rate of acquisition in the 3-CSRT was slower in lesion compared to non-lesion rats, lesion rats were able to acquire a level of accuracy (84%) comparable to that of non-lesion (90%) following 16 days of exercise. This suggests a delay in memory consolidation. There were no significant group differences in premature responses, a measure of impulsive behavior, after 16 days of learning the 3-CSRT. Lesion rats compared to non-lesion rats showed a trend of higher omission rate and a statistically significant greater standard deviation of omissions, suggesting a mild deficit in attention. Consistent with prior work (Hauber and Schmidt, 1994), lesion compared to non-lesion rats had a small but significantly longer reaction time (<1 s) for reward retrieval. This difference was unlikely due to motor deficits as dmCPu lesions do not alter spontaneous locomotor activity, rotarod performance (Wang et al., 2020) or forelimb motor function (Chang et al., 1999). Furthermore, dmCPu lesions do not significantly alter appetitive preference (Wang et al., 2020). Thus, differences in reward retrieval latency (or omissions rate) likely reflect a slowing of cognitive processing and mildly impaired attention, rather than a general motor dysfunction or a lack of motivation.

In contrast to the 3-CSRT, substantial and persistent deficits were unmasked during the 3-CSRT-R phase. During the first day of the 3-CSRT-R, both lesion and non-lesion rats showed an equivalent decrease in nose-poke accuracy. Following 15 days of cognitive training, non-lesion rats rapidly improved (∼80% accuracy), while lesion rats showed persistent deficits (∼50% accuracy). Performance plateaued thereafter, with an additional 10 days of cognitive training showing little change to the percent accuracy measure (Fig. 3). While a delay in memory consolidation may have contributed, the plateauing of performance beginning at ∼15 days for the Lesion/Non-Exercise group suggests that these deficits represent more than simply a slower rate of learning. Lesions also resulted in significant and persistent greater number of premature responses that plateaued at 15 days of cognitive training. We propose that the 3-CSRT-R task unmasked lesion-induced deficits in cognitive flexibility and response inhibition.

Qualitatively, the lesion effect on T-maze learning mirrored those in the operant task. Lesioned rats were slow to learn the Win-Stay task, and never achieved correct response rates above 70%, even after 20 days of cognitive training, while controls achieved a 90% correct response rate by 18 days (Fig. 4). Rule reversal (Win-Shift) enhanced these differences, with the lesioned rats significantly delayed in achieving the learning criterion, and never achieving more than 78% correct after 13 days of cognitive training, at a time when Non-Lesion rats showed 95% correct responses. Perseverative and regressive errors during the reversal phase were significantly greater in Lesion than in Non-Lesion rats as has previously been reported (Grospe et al., 2018).

Our studies showed that exercise in both the operant task and T-maze improved performance in lesioned rats. These results are consistent with earlier work in a rat stroke model showing that running exercise facilitates learning of a subsequent skilled forelimb task (Ploughman et al., 2007). Furthermore, exercise improved nose-poke accuracy during initial learning of the 3-CSRT task. However, as noted above, Lesion/Non-Exercise rats were able to achieve levels of accuracy equivalent to those of the controls and lesioned/exercised rats by days 14–16. The effect of exercise on cognitive improvement was most apparent during the rule shift phase (3-CSRT-R). Here, improvements in accuracy in lesion rats undergoing exercise were progressive, with improvement relative to Lesion/Non-Exercise rats maintained after 25 exercise sessions. Cognitive gains, however, were modest and significant only when exercise of all types was pooled. A greater effect of exercise in lesioned rats was seen on decreases in premature responses, a measure of behavioral impulsivity.

In the T-maze, the effect of exercise on cognitive improvement was also most apparent during rule reversal (Win-Shift). However, unlike results in the 3-CSRT-R operant task, Lesion/Non-Exercise rats were able to match the performance of lesioned/exercised rats in the T-maze by day 12. The reason likely was that the Win-Shift T-maze task was easier to learn than the 3-CSRT-R operant task as judged by the fewer number of sessions to reach plateau levels in the T-maze. This suggests that exercise can accelerate learning, but for simpler cognitive challenges Lesion/Non-Exercise rats can ‘catch up’ to the performance of Lesion/Exercise rats. This is in contrast to more challenging tasks such as the 3-CSRT-R, where exercise provided a prolonged performance advantage that extended across 25 test days. Future studies can evaluate this interpretation at longer follow-up periods. Our 6-OHDA PD model assumed that dopaminergic lesions were complete at the 2-week timepoint when exercise was initiated (see section 2.5.1), with exercise-related benefits being understood in the context of neurorestoration. If lesion maturation, however, continued beyond this 2-week timepoint as some have proposed, it is possible that a component of the benefits may have been due to solely neuroprotective rather than neurorestorative mechanisms.

4.2. Changes in dopaminergic receptors and the synaptic marker PSD-95 with lesion and exercise

In these studies, we examined mRNA transcript in striatal tissues and our results showed that by 4 weeks, exercise led to increased transcript expression of both DAR-D1 and the DAR-D2-like receptors 3 and 4 in the dorsal CPu, particularly in the dmCPu, the site with the greatest degree of 6-OHDA-mediated DA-depletion. Dopamine receptors are expressed pre-synaptically within dopaminergic terminals and post-synaptically within medium spiny neurons in the CPu. Since we examined transcripts and most expression is within cell bodies and therefore post-synaptic. Changes in these receptors were concurrent with exercise-induced improvement in cognitive flexibility. In our study, cognitive flexibility was assessed through a reversal learning paradigm in which the learned association of a ‘lights-on’ cue and its sucrose reward was reversed when a newly presented ‘lights-off’ cue was associated with the same reward. Cognitive flexibility relies on the interactions of the D1-and D2-like receptors [DAR-D2, DAR-D3, and DAR-D4] (Floresco et al., 2006; Bestmann et al., 2015) at the level of the prefrontal cortex and the striatum. Although the D3-receptor is expressed at a lower level than the D2-receptor within the dorsal striatum, its role and association with the D2-receptor in reversal learning has been well established (Boulougouris et al., 2009; Groman et al., 2016; Clarkson et al., 2017). In addition to the DAR-D3, the DAR-D1 and DAR-D4 also play a role in reversal learning. For example, application of DAR-D1 agonists lead to impairment in the early phase of reversal learning (Izquierdo et al., 2006). The D4-receptor shares a similar modulatory effect on reversal learning to DAR-D1 as demonstrated by the application of a DAR-D4 antagonist and its improvement on reversal learning (Connolly and Gomez-Serrano, 2014). While the importance of the D1-receptor and the D4-receptor signaling in reverse learning has been demonstrated in the prefrontal cortex (Floresco et al., 2006), our study suggests a role of these dopamine receptors in cognitive flexibility also at the level of the dorsomedial striatum. Our results are consistent with recent reports showing that D1-receptors on medium spiny neurons in the dmCPu play an important role in reversal tasks (Wang et al., 2019).

Previous work in our lab using the MPTP model of dopamine depletion, has shown an exercise-induced increase of DAR-D2 in the dorsal CPu (Fisher et al., 2004) after six-weeks of intensive treadmill exercise. In contrast to our previous exercise studies, we found no significant increase in DAR-D2 in the dorsomedial CPu after 4-weeks of wheel running. Possible explanations for this discrepancy include differences in exercise duration, intensity, and choice of toxin and location of DA-depletion. Unlike the dorsal CPU, we found no exercise-induced effects on DA receptor transcript expression in the ventral CPu. In addition, we saw no lesion effect on dopamine receptor transcript expression within the dorsal or ventral striatum. These findings are consistent with the literature which have shown both significant and non-significant changes in the DAR-D1 and DAR-D2 after dopamine depletion, which may due to differences in lesioning paradigms [degree of lesioning, post-lesioning time point, species, toxin and mode of delivery] (Berger et al., 1991; Cadet et al., 1991).

In these studies, using qRT-PCR, we examined mRNA transcript expression in striatal tissues for PSD-95 and synaptophysin. PSD-95 is a major scaffolding protein in the postsynaptic densities of dendritic spines enriched in glutamatergic medium spiny neurons. We found that dopamine depletion in the dorsal CPu was associated with loss of PSD-95 mRNA transcripts and that exercise significantly increased PSD-95 expression in 6-OHDA lesioned rats. This finding likely reflects the increased expression of this transcript in striatal medium spiny neurons, the cells within the striatum that express this synaptic gene and proteins at post-synaptic contacts. This increase in PSD-95 is consistent with synaptogenesis and could be occurring in either or both glutamatergic and dopaminergic terminals at medium spiny neurons. Previous work in non-human primates and mice has demonstrated a significant reduction in dendritic spine density in the striatum of monkeys and mice following dopaminergic deafferentation (Villalba et al., 2009; Toy et al., 2014), with exercise eliciting a significant restoration of spine density, along with increases in synaptophysin and PSD-95 protein expression (Toy et al., 2014). We did not observe changes in synaptophysin mRNA transcripts in striatal tissues which differs in the patterns of change in protein we and others have reported. This may reflect the fact that this protein, expressed in pre-synaptic terminals is transcribes in cell bodies that reside outside of the striatum such as the cerebral cortex or thalamus. The transcriptional and translational mechanisms by which exercise may restore synaptophysin and PSD-95 expression in our model remains unknown. Prior work in the 6-OHDA model has suggested a role for Arc (activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein) (Garcia et al., 2017), acting as a generalized transcription factor that can modulate dendritic spine formation and experience-dependent neuroplasticity (Peebles et al., 2010).

4.3. Translational aspects

Behavioral studies have shown that despite their slower learning-rates, PD subjects retain more or less intact motor learning (Nieuwboer et al., 2009). However, ‘task-switching deficits’ makes it difficult to translate learning acquired in a rehabilitation session to a real-world situation where responses must be adapted to context (Onla-or and Winstein, 2008). This inflexibility of thought and associated increased cognitive retention rates leads to errors of repetition when transferring between new categories of learning (Steinke and Kopp, 2020). We made a similar observation in our animal model. While the rate of acquisition of the 3-CSRT was delayed, lesioned rats were able to acquire a level of accuracy comparable to that of sham rats within 16 days of exercise (though not in the T-maze task). However, dramatic and persistent deficits were apparent in both the operant and T-maze tasks following the rule shift, such that lesioned rats never improved their performance much above chance levels, even after an extended period of exercise.

4.3.1. Effects of exercise on cognitive flexibility

Prior studies in naïve rodents have shown that exercise can facilitate reversal learning (Van der Borght et al., 2007; Snigdha et al., 2014; O'Leary et al., 2019). Our findings show that exercise-related improvements in cognitive flexibility can also be seen in the 6-OHDA striatal lesion model. Exercise is well known to elicit broad changes in neuroplasticity, including increases in neurogenesis (Ma et al., 2017). Increases in exercise-related neurogenesis have been reported to be associated with lower memory retention, while at the same time facilitating new learning, including reversal learning (Li et al., 2020). It has been proposed that such improved new learning may be the result of a decrease in proactive interference which usually occurs when consolidated memories inhibit new learning (Epp et al., 2016). While in the current study, exercise effects on nose-poke accuracy of lesioned rats were modest during the reversal phase, greater effects were noted for premature responses, a measure of impulsivity and response inhibition. The decrease in premature responses is consistent with an improved ability of the exercised animal to acquire new learning, either because of a lower exercise-related recall of the prior rule set as previously proposed (Epp et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020), or possibly through facilitated suppression of the prior rule-based learning. The findings of diminished premature responses mirror a report in PD patients where 6 weeks of intermittent aerobic walking elicits significant improvement in cognitive inhibition (Flanker test) but not in set shifting (Wisconsin card sort, Trail Making tests) (Uc et al., 2014). Others have observed improvements in inhibitory aptitude (Stroop test) but not in cognitive flexibility (Trail making test) in PD patients following 3 months of intermittent aerobic cycling (Duchesne et al., 2015).

Improved cognitive flexibility may reflect underlying functional adaptation in cerebral regions of the cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical and cortical-thalamo-hippocampal circuits (Wang et al., 2013), important in executive function and working memory. It has been suggested that motor rehabilitation programs for PD patients should include a relatively high cognitive demand, such that by engaging patients to practice task-switching, they might be able to overcome their context-dependency (Onla-or and Winstein, 2008; Petzinger et al., 2013). Surprisingly, we did not see a significant difference in cognitive outcomes in comparing different exercise modalities in lesioned rats (see Supplementary Fig. S2). This observation was valid even when exercise was undertaken for two different skill levels at comparable speeds and durations using the same exercise modality (complex versus smooth wheel running, Fig. S2). This was contrary to our expectation which, based on greater functional connectivity of the medial prefrontal-striatal circuit during acute walking in the skilled compared to the smooth wheel, had anticipated a differential cognitive effect of these different exercise modalities (Guo et al., 2017). Our findings differed from those reported in a recent meta-analysis in healthy human subjects, where there appears to be higher benefits after coordinative exercise compared to endurance, resistance and mixed exercise (Ludyga et al., 2020). In contrast, a recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials of physical exercise programs on cognitive function in PD reported that exercise-related improvements in global cognitive function, processing speed, sustained attention and mental flexibility (da Silva et al., 2018) showed the largest effect for intense treadmill exercise, not for skilled exercise (tango or cognitive exercise associated with motor exercise). However, a head-to-head comparison of different exercise modalities on cognitive function has to date not been done in PD patients. In our study, though behavioral outcomes of nose poke accuracy closely tracked across different exercise modalities, our study was insufficiently powered to detect small differences. Furthermore, we did not explore a full range of exercise durations and intensities, variables that in prior studies have shown differential efficacy across different exercise modalities (Coetsee and Terblanche, 2017; Ludyga et al., 2020), though this itself remains controversial (Sanders et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2021). Exercise was maintained for up to 12 weeks during the acquisition and testing phases of our cognitive testing. Future studies may wish to explore the effects of a broader range of exercise intensities and durations across different exercise modalities (da Costa Daniele et al., 2020).

5. Conclusion

In summary, our data adds to the expanding research reports showing the beneficial cognitive effects of physical exercise. Our prospective study demonstrates that following dopaminergic deafferentation, moderate exercise is able to provide improvements in cognitive flexibility and inhibitory aptitude, while eliciting increased expression of Drd1, Drd3, Drd4, synaptophysin, and PSD-95 in the associative and sensorimotor dorsal regions of the striatum.

Funding sources

Don Roberto Gonzalez Family Foundation (GP); Parkinson's Foundation (GP); US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Parkinson Research Program (USAMRMC) Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (CDMRP), Grant/Award Numbers: W81XWH18-0665 (GMP), W81XWH18-00443 (MWJ), W81XWH18-1-0666 (DPH).

Credit authorship contribution statement

Wang Zhuo: contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to data acquisition, was responsible for data analysis, were responsible for statistical analyses. Adam J. Lundquist: contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to data acquisition; were responsible for data analysis, was responsible for statistical analyses. Erin K. Donahue: contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to data acquisition; was responsible for data analysis. Yumei Guo: contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to data acquisition, was responsible for data analysis, were responsible for writing and editing the manuscript. Derek Phillips: contributed to data acquisition. Giselle M. Petzinger: contributed to the conception and design of the study, was responsible for data analysis, were responsible for writing and editing the manuscript, were responsible for acquisition of funding support. Michael W. Jakowec: contributed to the conception and design of the study. Daniel P. Holschneider: contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to data acquisition, was responsible for data analysis, was responsible for writing and editing the manuscript, was responsible for acquisition of funding support.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Daniel Holschneider, Giselle Petzinger, Michael Jakowec reports financial support was provided by Department of Defense and by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Parkinson Research Program. Giselle Petzinger reports financial support was provided by Don Roberto Gonzalez Family Foundation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the contributions of friends of the PD Research Program at USC. Special thanks to lab members for their helpful discussions. Thank you to Dan Haase, Ryan Wang, Susan Kishi, Tyler Gallagher, and Ilse Flores who participated in the exercising of animals.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crneur.2022.100039.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Alberts J.L., Linder S.M., Penko A.L., Lowe M.J., Phillips M. It is not about the bike, it is about the pedaling: forced exercise and Parkinson's disease. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2011;39(4):177–186. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e31822cc71a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova I., Lange C., Frings L., Klutmann S., Meyer P.T., Buchert R. Nigrostriatal degeneration in the cognitive part of the striatum in Parkinson disease is associated with frontomedial hypometabolism. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2020;45(2):95–99. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asinof S.K., Paine T.A. The 5-choice serial reaction time task: a task of attention and impulse control for rodents. JoVE. 2014;90 doi: 10.3791/51574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P.M., Ragozzino M.E. Contralateral disconnection of the rat prelimbic cortex and dorsomedial striatum impairs cue-guided behavioral switching. Learn. Mem. 2014;21(8):368–379. doi: 10.1101/lm.034819.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben V., Blin O., Bruguerolle B. Time-dependent striatal dopamine depletion after injection of 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat. Comparison of single bilateral and double bilateral lesions. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1999;51(12):1405–1408. doi: 10.1211/0022357991777038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger K., Przedborski S., Cadet J.L. Retrograde degeneration of nigrostriatal neurons induced by intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine injection in rats. Brain Res. Bull. 1991;26(2):301–307. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90242-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestmann S., Ruge D., Rothwell J., Galea J.M. The role of dopamine in motor flexibility. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 2015;27(2):365–376. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandini F., Levandis G., Bazzini E., Nappi G., Armentero M.T. Time-course of nigrostriatal damage, basal ganglia metabolic changes and behavioural alterations following intrastriatal injection of 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat: new clues from an old model. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;25(2):397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulougouris V., Castañé A., Robbins T.W. Dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonist quinpirole impairs spatial reversal learning in rats: investigation of D3 receptor involvement in persistent behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202(4):611–620. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B.M., Frost N., Rainey-Smith S.R., Doecke J., Markovic S., Gordon N., Weinborn M., Sohrabi H.R., Laws S.M., Martins R.N., Erickson K.I., Peiffer J.J. High-intensity exercise and cognitive function in cognitively normal older adults: a pilot randomised clinical trial. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2021;13(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00774-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H.D., Baker P.M., Ragozzino M.E. The parafascicular thalamic nucleus concomitantly influences behavioral flexibility and dorsomedial striatal acetylcholine output in rats. J. Neurosci. 2010;30(43):14390–14398. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2167-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn D., Weintraub D., Ravina B., Litvan I. Cognition in movement disorders: where can we hope to be in ten years? Mov. Disord. 2014;29(5):704–711. doi: 10.1002/mds.25850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J.L., Last R., Kostic V., Przedborski S., Jackson-Lewis V. Long-term behavioral and biochemical effects of 6-hydroxydopamine injections in rat caudate-putamen. Brain Res. Bull. 1991;26(5):707–713. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90164-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.W., Wachtel S.R., Young D., Kang U.J. Biochemical and anatomical characterization of forepaw adjusting steps in rat models of Parkinson's disease: studies on medial forebrain bundle and striatal lesions. Neuroscience. 1999;88(2):617–628. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama Y., Bussey T.J., Muir J.L. Effects of selective thalamic and prelimbic cortex lesions on two types of visual discrimination and reversal learning. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;14(6):1009–1020. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson R.L., Liptak A.T., Gee S.M., Sohal V.S., Bender K.J. D3 receptors regulate excitability in a unique class of prefrontal pyramidal cells. J. Neurosci. 2017;37(24):5846–5860. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0310-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetsee C., Terblanche E. The effect of three different exercise training modalities on cognitive and physical function in a healthy older population. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2017;14:13. doi: 10.1186/s11556-017-0183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly N.P., Gomez-Serrano M. D4 dopamine receptor-specific antagonist improves reversal learning impairment in amphetamine-treated male rats. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014;22(6):557–564. doi: 10.1037/a0038216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R. Dopaminergic modulation of cognitive function-implications for L-DOPA treatment in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006;30(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Daniele T.M., de Bruin P.F.C., de Matos R.S., de Bruin G.S., Maia Chaves C.J., de Bruin V.M.S. Exercise effects on brain and behavior in healthy mice, Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease model-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Brain Res. 2020;383:112488. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva F.C., Iop R.D.R., de Oliveira L.C., Boll A.M., de Alvarenga J.G.S., Gutierres Filho P.J.B., de Melo L., Xavier A.J., da Silva R. Effects of physical exercise programs on cognitive function in Parkinson's disease patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the last 10 years. PLoS One. 2018;13(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon R.M., Rawlins J.N. T-maze alternation in the rodent. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1(1):7–12. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnberger G., Jahanshahi M. Executive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: a review. J. Neuropsychol. 2013;7(2):193–224. doi: 10.1111/jnp.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey E.R., George B.P., Leff B., Willis A.W. The coming crisis: obtaining care for the growing burden of neurodegenerative conditions. Neurology. 2013;80(21):1989–1996. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318293e2ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne C., Lungu O., Nadeau A., Robillard M.E., Bore A., Bobeuf F., Lafontaine A.L., Gheysen F., Bherer L., Doyon J. Enhancing both motor and cognitive functioning in Parkinson's disease: aerobic exercise as a rehabilitative intervention. Brain Cognit. 2015;99:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp J.R., Silva Mera R., Köhler S., Josselyn S.A., Frankland P.W. Neurogenesis-mediated forgetting minimizes proactive interference. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10838. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B.E., Petzinger G.M., Nixon K., Hogg E., Bremmer S., Meshul C.K., Jakowec M.W. Exercise-induced behavioral recovery and neuroplasticity in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned mouse basal ganglia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;77(3):378–390. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco S.B., Magyar O., Ghods-Sharifi S., Vexelman C., Tse M.T. Multiple dopamine receptor subtypes in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat regulate set-shifting. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(2):297–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia P.C., Real C.C., Britto L.R. The impact of short and long-term exercise on the expression of arc and AMPARs during evolution of the 6-hydroxy-dopamine animal model of Parkinson's disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;61(4):542–552. doi: 10.1007/s12031-017-0896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groman S.M., Smith N.J., Petrullli J.R., Massi B., Chen L., Ropchan J., Huang Y., Lee D., Morris E.D., Taylor J.R. Dopamine D3 receptor availability is associated with inflexible decision making. J. Neurosci. 2016;36(25):6732–6741. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3253-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grospe G.M., Baker P.M., Ragozzino M.E. Cognitive flexibility deficits following 6-OHDA lesions of the rat dorsomedial striatum. Neuroscience. 2018;374:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Wang Z., Prathap S., Holschneider D.P. Recruitment of prefrontal-striatal circuit in response to skilled motor challenge. Neuroreport. 2017;28(18):1187–1194. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauber W., Schmidt W.J. Differential effects of lesions of the dorsomedial and dorsolateral caudate-putamen on reaction time performance in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 1994;60(2):211–215. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano S. Clinical implications for dopaminergic and functional neuroimage research in cognitive symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mol. Med. 2021;27(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s10020-021-00301-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intzandt B., Beck E.N., Silveira C.R.A. The effects of exercise on cognition and gait in Parkinson's disease: a scoping review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018;95:136–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo A., Wiedholz L.M., Millstein R.A., Yang R.J., Bussey T.J., Saksida L.M., Holmes A. Genetic and dopaminergic modulation of reversal learning in a touchscreen-based operant procedure for mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2006;171(2):181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Oh M., Oh J.S., Moon H., Chung S.J., Lee C.S., Kim J.S. Association of striatal dopaminergic neuronal integrity with cognitive dysfunction and cerebral cortical metabolism in Parkinson's disease with mild cognitive impairment. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2019;40(12):1216–1223. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000001098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintz N., Petzinger G.M., Akopian G., Ptasnik S., Williams C., Jakowec M.W., Walsh J.P. Exercise modifies alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor expression in striatopallidal neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned mouse. J. Neurosci. Res. 2013;91(11):1492–1507. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal S.L., Dall T.M., Chakrabarti R., Storm M.V., Jain A. The current and projected economic burden of Parkinson's disease in the United States. Mov. Disord. 2013;28(3):311–318. doi: 10.1002/mds.25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Li R., Zhou C. Memory traces diminished by exercise affect new learning as proactive facilitation. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14:189. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludyga S., Gerber M., Puhse U., Looser V.N., Kamijo K. Systematic review and meta-analysis investigating moderators of long-term effects of exercise on cognition in healthy individuals. Nat. Human Behav. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist A.J., Gallagher T.J., Petzinger G.M., Jakowec M.W. Exogenous l-lactate promotes astrocyte plasticity but is not sufficient for enhancing striatal synaptogenesis or motor behavior in mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021;99(5):1433–1447. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist A.J., Parizher J., Petzinger G.M., Jakowec M.W. Exercise induces region-specific remodeling of astrocyte morphology and reactive astrocyte gene expression patterns in male mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019;97(9):1081–1094. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C.L., Ma X.T., Wang J.J., Liu H., Chen Y.F., Yang Y. Physical exercise induces hippocampal neurogenesis and prevents cognitive decline. Behav. Brain Res. 2017;317:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald P.A., Monchi O. Differential effects of dopaminergic therapies on dorsal and ventral striatum in Parkinson's disease: implications for cognitive function. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;2011:572743. doi: 10.4061/2011/572743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G.S., Shoup R.E. Simultaneous multiple electrode liquid chromatographic-electrochemical assay for catecholamines, indole-amines and metabolites in brain tissue. J. Chromatogr. 1983;255:533–544. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)88308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwboer A., Rochester L., Muncks L., Swinnen S.P. Motor learning in Parkinson's disease: limitations and potential for rehabilitation. Park. Relat. Disord. 2009;15(Suppl. 3):S53–S58. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary J.D., Hoban A.E., Murphy A., O'Leary O.F., Cryan J.F., Nolan Y.M. Differential effects of adolescent and adult-initiated exercise on cognition and hippocampal neurogenesis. Hippocampus. 2019;29(4):352–365. doi: 10.1002/hipo.23032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill M., Brown V.J. The effect of striatal dopamine depletion and the adenosine A2A antagonist KW-6002 on reversal learning in rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2007;88(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onla-or S., Winstein C.J. Determining the optimal challenge point for motor skill learning in adults with moderately severe Parkinson's disease. Neurorehabilitation Neural Repair. 2008;22(4):385–395. doi: 10.1177/1545968307313508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]